Abstract

Background

Recent studies have suggested that the interactions among several factors affect the onset, progression, and prognosis of major depressive disorder. This study investigated how childhood abuse, neuroticism, and adult stressful life events interact with one another and affect depressive symptoms in the general adult population.

Subjects and methods

A total of 413 participants from the nonclinical general adult population completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, the Child Abuse and Trauma Scale, the neuroticism subscale of the shortened Eysenck Personality Questionnaire – Revised, and the Life Experiences Survey, which are self-report scales. Structural equation modeling (Mplus version 7.3) and single and multiple regressions were used to analyze the data.

Results

Childhood abuse, neuroticism, and negative evaluation of life events increased the severity of the depressive symptoms directly. Childhood abuse also indirectly increased the negative appraisal of life events and the severity of the depressive symptoms through enhanced neuroticism in the structural equation modeling.

Limitations

There was recall bias in this study. The causal relationship was not clear because this study was conducted using a cross-sectional design.

Conclusion

This study suggested that neuroticism is the mediating factor for the two effects of childhood abuse on adulthood depressive symptoms and negative evaluation of life events. Childhood abuse directly and indirectly predicted the severity of depressive symptoms.

Keywords: childhood abuse, depression, neuroticism, stressful life events, structural equation modeling

Introduction

It is known that the onset of major depressive disorder and the severity of depressive symptoms are affected by various factors such as genes, environment, and personality.1–3 Recent studies pointed out that childhood abuse is an important risk factor for the severity of depressive symptoms.2,4 However, there is a long time interval between childhood abuse and adult depressive symptoms. Therefore, it is assumed that there are various mediating factors5 between these two factors, but the mediating factors are not elucidated sufficiently. In our earlier study, we first reported that affective temperaments are mediating factors for the effect of childhood abuse on adult depressive symptoms,6 and we suggested that personality is the mediating factor for the effect of childhood abuse on adult depressive symptoms.

Recently, a number of studies suggested the close relationship between the personality trait “neuroticism” and major depressive disorder or the severity of depressive symptoms.7,8 As a result, in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) manual revised in 2013, it is specified as clear evidence that neuroticism is an important risk factor for the onset of major depressive disorder.9 Kendler and Gardner8 reported that, in a structural equation modeling (SEM) study targeting adult twins, childhood sexual abuse and neuroticism affect the depressive symptoms, but the mediating effect of neuroticism was not revealed.

On the other hand, adult stressful life events are a well-known risk factor for the onset of major depressive disorder.10,11 An earlier research study suggested that how they recognized the intensity of stress produced by life events is more important than the weight of life events themselves in evaluating the psychological impact of life events.12 In a large-scale prospective study, Kendler et al3 found that neuroticism and adult stressful life events interact and affect the onset of major depressive disorder; in other words, high levels of neuroticism appear to render individuals more likely to develop depressive episodes in response to stressful life events.

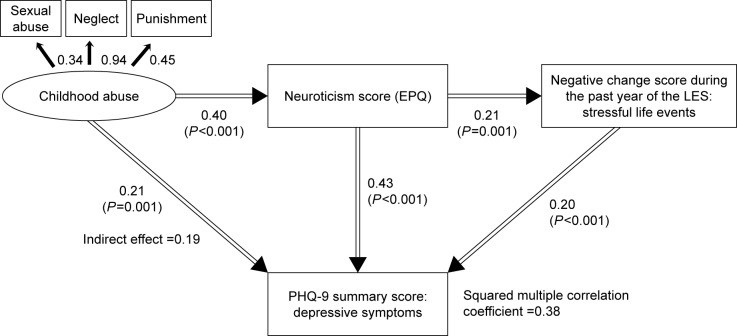

From these previous studies, we hypothesized that neuroticism, childhood abuse, and adult stressful life events interact with one another and affect depressive symptoms and that neuroticism is the mediating factor for the effect of childhood abuse on depressive symptoms (Figure 1). To verify the hypothesis, we examined the association between depressive symptoms, childhood abuse, neuroticism, and adult stressful life events and examined the mediating effect of neuroticism in the general adult population using SEM.

Figure 1.

The hypothesis.

Notes: Structural equation model of the hypothesis of this study. In this model, childhood abuse, neuroticism, and adult stressful life events predict depressive symptoms.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

This study was part of a larger study conducted between January and August 2014 on 853 Japanese volunteers from the general adult population.13 All volunteers were recruited by flyers and word of mouth. Of the 853 volunteers, 413 subjects (48.4%) provided a complete response to the questionnaires. We did not use any exclusion criteria, because we focused on the general population but not healthy population. Four questionnaires and a demographic questionnaire were distributed and returned anonymously. Written informed consent was obtained from all of the subjects. This study was approved by the ethics committees of Hokkaido University Hospital and Tokyo Medical University.

Questionnaires

Patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

The Japanese version of the PHQ-9, an autoquestionnaire, was completed by subjects.14 This study used a summary score (0–27) of the PHQ-9 for evaluating the severity of depressive symptoms.

Life experiences survey (LES)

The Japanese version of the LES (57 items) is an autoquestionnaire that allows respondents to indicate events during the past year.6,12 Subjects are asked to indicate those events that they experienced during the past year. They evaluate whether they viewed the event as being positive or negative, and the perceived impact of those events on their life at the time of occurrence. Ratings are on a 7-point scale ranging from extremely negative (−3) to extremely positive (+3). The sums of the impact ratings of those events designated as negative and positive by the subject provide a negative change score and a positive change score, respectively.

Neuroticism subscale on the shortened Eysenck Personality Questionnaire – Revised (EPQ-R)

Neuroticism was assessed by the neuroticism subscale (12 items) of the shortened version of the EPQ-R15 following the method of Kendler et al.3 The validity and reliability of the Japanese short-scale version were confirmed.16

Child abuse and trauma scale (CATS)

In the Japanese version of the CATS (38 items),17,18 participants rate how frequently a particular abusive experience occurred to them during their childhood and adolescence with a scale of 0–4 (0= never; 4= always). Three subscales, neglect or negative home atmosphere, punishment, and sexual abuse, were calculated.

Data analysis

Based on the hypothesis presented in Figure 1, we designed an SEM: childhood abuse, neuroticism, and adult stressful life events predicted depressive symptoms. A latent variable, childhood abuse, was composed of three observed variables (sexual abuse, neglect, and punishment). In this path analysis, we analyzed the direct and indirect effects using maximum likelihood covariance estimation to analyze the model. For the statistical evaluation of the SEM, we calculated two indices of goodness of fit: the comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI >0.95 and RMSEA <0.08 indicate an acceptable fit; CFI >0.97 and RMSEA <0.05 indicate a good fit.19 The standardized coefficients (with a maximum of +1 and a minimum of −1) were shown.

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the questionnaire data and the demographic characteristics between the two groups. Correlation between the parameters and the predictive factors was analyzed by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient and multiple regression analysis.

Statistical analyses were conducted using Mplus version 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA) for the covariance structure analysis, and SPSS version 22.0 software for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for the multiple regression analysis, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, and the Mann–Whitney U test. The level of statistically significant differences was set at P<0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics, CATS, EPQ neuroticism, LES, and PHQ-9 of the subjects

The CATS, EPQ neuroticism, PHQ-9, and LES scores and demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Sex (female), marital status (unmarried), presence of offspring (no), and comorbidity of physical disease were associated with severer depressive symptoms (PHQ-9). Total, neglect, punishment, and sexual abuse scores of the CATS, the EPQ neuroticism score, and the negative change scores on the LES were significantly and positively correlated with the severity of depressive symptoms (PHQ-9). Age was significantly and negatively correlated with the severity of depressive symptoms (PHQ-9).

Table 1.

Characteristics, PHQ-9, CATS, EPQ, LES scores, and correlation with PHQ-9 or effects on PHQ-9 in 413 general adult subjects

| Characteristics or measures | Value (number or mean ± SD) | Correlation with PHQ (ρ) or effect on PHQ-9 (mean ± SD of PHQ-9 scores, Mann–Whitney U test) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.31±11.99 | ρ=−0.113* |

| Sex (male:female) | 221:192 | Male 2.88±3.61 vs female 3.76±4.35* (Mann–Whitney U test) |

| Education, years | 15.12±2.00 | ρ=−0.054, ns |

| Employment status (employed:unemployed) | 350:56 | Employed 3.27±3.94 vs unemployed 3.59±4.43, ns (Mann–Whitney U test) |

| Marital status (married:unmarried) | 291:119 | Married 3.00±3.70 vs unmarried 4.04±4.57** (Mann–Whitney U test) |

| Living-alone (yes:no) | 103:302 | Yes 3.54±4.15 vs no 3.16±3.93, ns (Mann–Whitney U test) |

| Number of offspring | 1.30±1.17 | ρ=−0.076, ns |

| Presence of offspring (yes:no) | 276:134 | Yes 2.93±3.85 vs no 3.93±4.18** (Mann–Whitney U test) |

| Comorbidity of physical disease (yes:no) | 85:324 | Yes 3.84±4.09 vs no 3.12±3.93* (Mann–Whitney U test) |

| First-degree relative with psychiatric disease (yes:no) | 41:370 | Yes 3.77±4.41 vs no 3.24±3.95, ns (Mann–Whitney U test) |

| PHQ-9 score | 3.30±4.00 | |

| CATS | ||

| Sexual abuse | 0.04±0.22 | ρ=0.156** |

| Neglect | 0.62±0.58 | ρ=0.332** |

| Punishment | 1.42±0.61 | ρ=0.206** |

| Total | 0.66±0.43 | ρ=0.327** |

| Neuroticism score (EPQ) | 3.60±3.19 | ρ=0.530** |

| LES (change score) | ||

| Negative | 1.65±3.10 | ρ=0.320** |

| Positive | 1.64±2.93 | ρ=−0.039, ns |

Notes: Data presented as mean ± SD or number. ρ= Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

P<0.05.

P<0.01.

Abbreviations: CATS, Child Abuse and Trauma Scale; EPQ, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; LES, Life Experiences Survey; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; ns, not significant; SD, standard deviation.

Stepwise multiple regression analysis of the explanatory variables on the PHQ-9

A stepwise multiple regression analysis analyzed the 15 explanatory variables shown in Table 1. A total score on the CATS that had a significant correlation with PHQ-9 (Table 1) was excluded from the stepwise multiple regression analysis because of a high correlation with a neglect score on the CATS (P=0.84). The results of a stepwise multiple regression analysis are shown in Table 2: the dependent factor was a PHQ-9 summary score and independent factors were age, sex (female =1, male =0), education (years), marital status (married =1, unmarried =0), living alone (yes =1, no =0), employment status (unemployed =1, employed =0), presence of offspring (yes =1, no =0), comorbidity of physical disease (yes =1, no =0), first-degree relative with psychiatric disease (yes =1, no =0), neglect, punishment, and sexual abuse scores on the CATS, EPQ neuroticism score, negative change score on the LES, and positive change score on the LES. Neglect score on the CATS, neuroticism score on the EPQ, and negative change score on the LES were significant predictors of PHQ-9 (F=43.7, P<0.001, adjusted R2=0.37), whereas other factors were excluded from the model. In this multiple regression analysis, multicollinearity was denied.

Table 2.

The results of stepwise multiple regression analysis of PHQ-9

| Positive variables selected | B | SE B | Beta | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism score (EPQ) | 0.544 | 0.057 | 0.43 | <0.001 |

| Negative change score of LES | 0.250 | 0.056 | 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Neglect score of CATS | 1.310 | 0.303 | 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Adjusted R2=0.37 | <0.001 |

Notes: B, partial regression coefficient, Beta, standardized partial regression coefficient. Dependent factor, PHQ-9 summary score. Fifteen independent factors: age, sex (female =1, male =0), education years, employment status (unemployed =1, employed =0), marital status (married =1, unmarried =0), living-alone (yes =1, no =0), presence of offspring (yes =1, no =0), comorbidity of physical disease (yes =1, no =0), first-degree relative with psychiatric disease (yes =1, no =0), neglect, punishment, and sexual abuse scores of CATS, EPQ neuroticism score, negative change scores of LES, and positive change scores of LES.

Abbreviations: CATS, Child Abuse and Trauma Scale; EPQ, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; LES, Life Experiences Survey; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; SE, standard error.

Analysis of the SEM

To examine the relationship between all of the variables, a structural equation model was built from the results of the multiple regression analysis (Figure 2). The results of the path coefficients calculated by Mplus are shown in Figure 2. A good fit of the model was obtained as follows: RMSEA =0.000, CFI =1.000. The all-path coefficients were substantially significant. According to the SEM and consistent with the results of the multiple regression analysis (Table 2), neglect subscale score showed a very high-standardized coefficient with the latent variable “childhood abuse”. Childhood abuse, EPQ neuroticism score, and negative change score of the LES predicted the PHQ-9 summary score significantly. The effect of childhood abuse on the PHQ-9 summary score was indirectly and significantly mediated by the EPQ neuroticism score (standardized indirect path coefficient =0.17, P<0.001). The effect of childhood abuse on the negative change score of the LES was indirectly and significantly mediated by the EPQ neuroticism score (standardized indirect path coefficient =0.08, P=0.003). The effect of the EPQ neuroticism score on the PHQ-9 summary score was indirectly and significantly mediated by the negative change score of the LES (standardized indirect path coefficient =0.04, P=0.022). The squared multiple correlation coefficient for the PHQ-9 summary score was 0.38, indicating that this model explains 38% of the variability in PHQ-9 score.

Figure 2.

Covariance structure analysis in 413 general adult subjects.

Notes: The results of the covariance structure analysis in the structural equation model with childhood abuse (CATS), neuroticism (EPQ), adult stressful life events (LES), and depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) in 413 subjects from the general adult population. Rectangles indicate the observed variables. Oval indicates the latent variable. The arrows with double lines indicate the statistically significant effects. The numbers beside the arrows show the standardized path coefficients (−1 to +1). The indirect effect means the sum of effects of childhood abuse on PHQ-9 scores in paths through neuroticism and negative life events.

Abbreviations: CATS, Child Abuse and Trauma Scale; EPQ, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; LES, Life Experiences Survey; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Discussion

This study may be the first study revealing that childhood abuse indirectly affected depressive symptoms through enhanced neuroticism as the mediating factor, while it also affects them directly. This study found that, in 413 adults from the general population, childhood abuse, neuroticism, and negative evaluation of life events directly affect depressive symptoms, and neuroticism is the important and significant mediating factor for two effects of childhood abuse on depressive symptoms and negative evaluation of life events.

Previous studies have examined the effect of childhood abuse and neuroticism on the severity of depressive symptoms,8,20,21 but no research has revealed the direct correlation between childhood abuse and neuroticism. Hayashi et al20 revealed that personality, which was evaluated by Neuroticism Extroversion Openness Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI), mediates the effect of childhood abuse on the severity of depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder, but the effect of neuroticism itself was not clear. In addition, because their study targeted patients with major depressive disorder, there was a possibility that the personality traits were affected by the symptoms of major depressive disorder.22 In their study, the relationship between the personality traits and the severity of depressive disorder was ambiguous. However, because we targeted the general adult population, the relationship between neuroticism and the severity of depressive symptoms was considered to be more appropriate.

There was a study which investigated the effect of 20 risk factors, including childhood abuse and neuroticism, on the onset of major depressive episodes and sex differences by using SEM.8 This study was a well-considered study and calculated the total effect of several risk factors. Due to the nature of the study design, it was not possible to identify whether neuroticism is the mediating factor of the depressogenic effect of childhood abuse on the onset of major depressive episodes. On the other hand, using SEM that limited a few explanatory variables, we showed the clear mediating effect of neuroticism for the effect of childhood abuse on depressive symptoms.

As described earlier, Kendler et al3 revealed that neuroticism and stressful life events interact with one another and affect the onset of major depressive episodes in a large-scale prospective study. Our study found the two effects of neuroticism on negative evaluation of life events. First, neuroticism mediated the effect of childhood abuse on negative evaluation of life events. Second, neuroticism enhanced negative evaluation of life events and affected the depressive symptoms indirectly. It is likely that these two effects of neuroticism are closely related to the interaction between neuroticism and stressful life events as reported by Kendler et al.3

There are some limitations to this study. First, this study used self-report questionnaires that depend on memories, which might cause recall bias. Second, because this study was a cross-sectional study and not a prospective study, the causal relationship was not clear. Third, as this study targeted the general adult population including many healthy people, it is difficult to extrapolate the result of this study to the pathogenesis model of major depressive disorder. Fourth, we did not evaluate the use of medication and comorbid diseases in detail. Fifth, 48.4% of volunteers provided a complete response, which might cause selection bias.

Conclusion

We revealed that, in the general adult population, childhood abuse, neuroticism, and negative life events interact and affect depressive symptoms by using SEM. The results of this study showed that neuroticism is the important mediating factor for the effects of childhood abuse on adult depressive symptoms and adult negative evaluation of life events. No studies have investigated these two mediating effects; this study may contribute to the elucidation of the pathogenesis of depression. A large-scale prospective study hypothesizing that neuroticism mediates the effect of childhood abuse on the development of depressive symptoms will be necessary.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the medical editors from the Department of International Medical Communications of Tokyo Medical University for editing and reviewing the initial English manuscript. This study was partly supported by the program “Integrated research on neuropsychiatric disorders” conducted under the Strategic Research Program for Brain Sciences of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Dr Inoue and Dr Takaesu designed the study and wrote the protocol. Ms Nakai and Dr K Ono collected and analyzed data. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Yoshikazu Takaesu has received personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Eli Lilly, Eisai, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, and Yoshitomiyakuhin, and grants from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, and Eisai. Ichiro Kusumi has received personal fees from Astellas, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Janssen Pharmaceutical, and Nippon Chemiphar; grants from AbbVie GK, Asahi Kasei Pharma, and Boehringer Ingelheim; and grants and personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Meiji Seika Pharma, MSD, Novartis Pharma, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Shionogi, and Yoshitomiyakuhin. Takeshi Inoue has received personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Asahi Kasei Pharma, Shionogi, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, and Takeda Pharmaceutical; grants from Astellas; and grants and personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Eisai, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Pfizer, AbbVie GK, MSD, Yoshitomiyakuhin, and Meiji Seika Pharma; and is a member of the advisory boards of GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Mochida Pharmaceutical and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma. The authors report no other actual or potential conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Smith JM, Gibb BE, Neeren AM. Role of parenting and maltreatment histories in unipolar and bipolar mood disorders: mediation by cognitive vulnerability to depression. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2006;9(1):23–64. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301(5631):386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kendler KS, Kuhn J, Prescott CA. The interrelationship of neuroticism, sex, and stressful life events in the prediction of episodes of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):631–636. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2004;82(2):217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakai Y, Inoue T, Toda H, et al. The influence of childhood abuse, adult stressful life events and temperaments on depressive symptoms in the nonclinical general adult population. J Affect Disord. 2014;158:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kendler KS, Gardner CO. A longitudinal etiologic model for symptoms of anxiety and depression in women. Psychol Med. 2011;41(10):2035–2045. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kendler KS, Gardner CO. Sex differences in the pathways to major depression: a study of opposite-sex twin pairs. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(4):426–435. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13101375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(6):837–841. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annu Rev Psychol. 1997;48:191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarason IG, Johnson JH, Siegel JM. Assessing the impact of life changes: development of the Life Experiences Survey. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1978;46(5):932–946. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanai Y, Takaesu Y, Nakai Y, et al. The influence of childhood abuse, adult life events, and affective temperaments on the well-being of the general, nonclinical adult population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:823–832. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S100474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muramatsu K, Miyaoka H, Kamijima K, et al. The patient health questionnaire, Japanese version: validity according to the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview-plus. Psychol Rep. 2007;101(3 pt 1):952–960. doi: 10.2466/pr0.101.3.952-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eysenck SBG, Eysenck HJ, Barrett P. A revised version of the psychoticism scale. Pers Individ Dif. 1985;6(1):21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakai Y, Inoue T, Toyomaki A, et al. A study of validation of the Japanese version of the shortened Eysenck Personality Questionnaire-Revised; The 35th Congress of Japanese Society for Psychiatric Diagnosis; Sapporo: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanders B, Becker-Lausen E. The measurement of psychological maltreatment: early data on the Child Abuse and Trauma Scale. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19(3):315–323. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(94)00131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanabe H, Ozawa S, Goto K. Psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the Child Abuse and Trauma Scale (CATS); The 9th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; Kobe: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol Res. 2003;8(2):23–74. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi Y, Okamoto Y, Takagaki K, et al. Direct and indirect influences of childhood abuse on depression symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:244. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0636-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kendler KS, Kuhn JW, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse, stressful life events and risk for major depression in women. Psychol Med. 2004;34(8):1475–1482. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400265x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santor DA, Bagby RM, Joffe RT. Evaluating stability and change in personality and depression. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(6):1354–1362. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.6.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]