Abstract

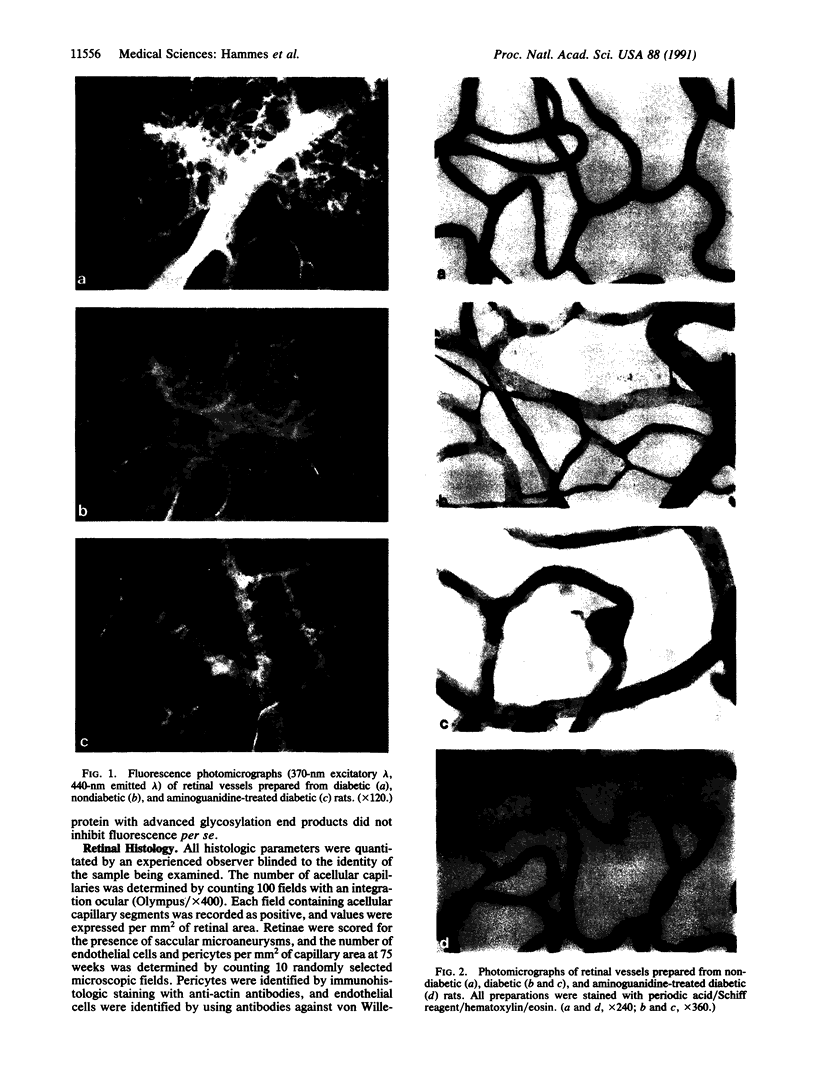

Retinal capillary closure induced by hyperglycemia is the principal pathophysiologic abnormality underlying diabetic retinopathy, but the mechanisms by which this induction occurs are not clear. Treatment of diabetic rats for 26 weeks with aminoguanidine, an inhibitor of advanced glycosylation product formation, prevented a 2.6-fold accumulation of these products at branching sites of precapillary arterioles where abnormal periodic acid/Schiff reagent-positive deposits also occurred. Aminoguanidine treatment completely prevented abnormal endothelial cell proliferation and significantly diminished pericyte dropout. After 75 weeks, untreated diabetic animals developed an 18.6-fold increase in the number of acellular capillaries and formed capillary microaneurysms, characteristic pathologic features of background diabetic retinopathy. In contrast, aminoguanidine-treated diabetic animals had only a 3.6-fold increase in acellular capillaries and no microaneurysms. These findings indicate that advanced glycosylation product accumulation contributes to the development of diabetic retinopathy and suggest that aminoguanidine may have future therapeutic use in this disorder.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Beaven M. A., Gordon J. W., Jacobsen S., Severs W. B. A specific and sensitive assay for aminoguanidine: its application to a study of the disposition of aminoguanidine in animal tissues. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1969 Jan;165(1):14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnick G. H., Davis M. D., Myers F. L., de Venecia G. Clinicopathologic correlations in diabetic retinopathy. II. Clinical and histologic appearances of retinal capillary microaneurysms. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977 Jul;95(7):1215–1220. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450070113010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee M., Cerami A., Vlassara H. Advanced glycosylation end products in tissue and the biochemical basis of diabetic complications. N Engl J Med. 1988 May 19;318(20):1315–1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198805193182007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee M. Glycosylation products as toxic mediators of diabetic complications. Annu Rev Med. 1991;42:159–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.42.020191.001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee M., Vlassara H., Kooney A., Ulrich P., Cerami A. Aminoguanidine prevents diabetes-induced arterial wall protein cross-linking. Science. 1986 Jun 27;232(4758):1629–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.3487117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büscher C., Weis A., Wöhrle M., Bretzel R. G., Cohen A. M., Federlin K. Islet transplantation in experimental diabetes of the rat. XII. Effect on diabetic retinopathy. Morphological findings and morphometrical evaluation. Horm Metab Res. 1989 May;21(5):227–231. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engerman R. L., Kern T. S. Progression of incipient diabetic retinopathy during good glycemic control. Diabetes. 1987 Jul;36(7):808–812. doi: 10.2337/diab.36.7.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engerman R. L. Pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 1989 Oct;38(10):1203–1206. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.10.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engerman R., Bloodworth J. M., Jr, Nelson S. Relationship of microvascular disease in diabetes to metabolic control. Diabetes. 1977 Aug;26(8):760–769. doi: 10.2337/diab.26.8.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito C., Gerlach H., Brett J., Stern D., Vlassara H. Endothelial receptor-mediated binding of glucose-modified albumin is associated with increased monolayer permeability and modulation of cell surface coagulant properties. J Exp Med. 1989 Oct 1;170(4):1387–1407. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene D. A., Lattimer S. A., Sima A. A. Sorbitol, phosphoinositides, and sodium-potassium-ATPase in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. N Engl J Med. 1987 Mar 5;316(10):599–606. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198703053161007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUWABARA T., COGAN D. G. Studies of retinal vascular patterns. I. Normal architecture. Arch Ophthalmol. 1960 Dec;64:904–911. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1960.01840010906012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kador P. F., Robison W. G., Jr, Kinoshita J. H. The pharmacology of aldose reductase inhibitors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1985;25:691–714. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.25.040185.003355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R., Klein B. E., Moss S. E., Davis M. D., DeMets D. L. Glycosylated hemoglobin predicts the incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy. JAMA. 1988 Nov 18;260(19):2864–2871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R., Klein B. E., Moss S. E., Davis M. D., DeMets D. L. The Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. II. Prevalence and risk of diabetic retinopathy when age at diagnosis is less than 30 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984 Apr;102(4):520–526. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030398010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T. S., Saltsman K. A., Ohashi H., King G. L. Activation of protein kinase C by elevation of glucose concentration: proposal for a mechanism in the development of diabetic vascular complications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jul;86(13):5141–5145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- Monnier V. M., Kohn R. R., Cerami A. Accelerated age-related browning of human collagen in diabetes mellitus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Jan;81(2):583–587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.2.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls K., Mandel T. E. Advanced glycosylation end-products in experimental murine diabetic nephropathy: effect of islet isografting and of aminoguanidine. Lab Invest. 1989 Apr;60(4):486–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarsio J. F., Reger L. A., Furcht L. T. Decreased interaction of fibronectin, type IV collagen, and heparin due to nonenzymatic glycation. Implications for diabetes mellitus. Biochemistry. 1987 Feb 24;26(4):1014–1020. doi: 10.1021/bi00378a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsilibary E. C., Charonis A. S., Reger L. A., Wohlhueter R. M., Furcht L. T. The effect of nonenzymatic glucosylation on the binding of the main noncollagenous NC1 domain to type IV collagen. J Biol Chem. 1988 Mar 25;263(9):4302–4308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlassara H., Brownlee M., Manogue K. R., Dinarello C. A., Pasagian A. Cachectin/TNF and IL-1 induced by glucose-modified proteins: role in normal tissue remodeling. Science. 1988 Jun 10;240(4858):1546–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.3259727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]