Abstract

Purpose

MRI is under evaluation for image-guided intervention for prostate cancer. The sensitivity and specificity of MRI parameters is determined via correlation with the gold-standard of histopathology. Whole-mount histopathology of prostatectomy specimens can be digitally registered to in vivo imaging for correlation. When biomechanical-based deformable registration is employed to account for deformation during histopathology processing, the ex vivo biomechanical properties are required. However, these properties are altered by pathology fixation, and vary with disease. Hence, this study employs magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) to measure ex vivo prostate biomechanical properties before and after fixation.

Methods

A quasi-static MRE method was employed to measure high resolution maps of Young’s modulus (E) before and after fixation of canine prostate and prostatectomy specimens (n=4) from prostate cancer patients who had previously received radiation therapy. For comparison, T1, T2 and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) were measured in parallel.

Results

E (kPa) varied across clinical anatomy and for histopathology-identified tumor: peripheral zone: 99(±22), central gland: 48(±37), tumor: 85(±53), and increased consistently with fixation (factor of 11±5; p<0.02). T2 decreased consistently with fixation, while changes in T1 and ADC were more complex and inconsistent.

Conclusion

The biomechanics of the clinical prostate specimens varied greatly with fixation, and to a lesser extent with disease and anatomy. The data obtained will improve the precision of prostate pathology correlation, leading to more accurate disease detection and targeting.

Keywords: Quasi-static Magnetic Resonance Elastography, Prostate Cancer, Pathology Formaldehyde Fixation, Water Relaxation, Diffusion

INTRODUCTION

MRI is increasingly being employed for prostate cancer diagnosis and therapy planning. Parameters such as T2-weighted signal (T2w), and parameters derived from dynamic contrast enhanced MRI, diffusion-weighted MRI and MR spectroscopic imaging are undergoing evaluation for prostate cancer localization for MR-guided biopsy and targeted therapy such as high dose rate brachytherapy (Haider et al., 2007; Haider et al., 2008; Menard et al., 2004).

The sensitivity and specificity of MR imaging parameters for disease diagnosis are evaluated via correlation with the gold-standard of histopathology (Langer et al., 2009). This task is performed more accurately through a 3D deformable registration of the histopathology volume (constructed from whole-mount histology slides) to the in vivo imaging volume (McNiven et al., 2009; Dawson et al., 2007; Brock et al., 2006; Samavati et al., 2011). As tissue deformation between the in vivo state and histology has multiple sources of influence from the various histopathology processing steps, a more realistic deformation is achieved by performing step-wise registrations backwards through the tissue states (Samavati et al., 2011): 1) A digitally reconstructed histopathology volume to an MRI volume of the ex vivo whole specimen, which has been preserved in fixative solution (fixation); 2) The result of step #1 to an MRI volume of the specimen before fixation; 3) The result of step #2 to the in vivo MRI volume.

When a biomechanical-based registration method (Brock et al., 2005) is employed, knowledge of the biomechanical properties of ex vivo tissue is required. However, fixation is known to change tissue biomechanical properties (McGrath et al., 2012; McGrath et al., 2011). Furthermore, prostate biomechanics varies with cancer (McGrath et al., 2012; McGrath et al., 2011) and between prostate anatomical zones (Krouskop et al., 1998; Kemper et al., 2004). Hence, for accurate deformable registration these changes and variations must be measured and incorporated. Precise biomechanical properties are critical, as (Chi et al., 2006) found that an uncertainty of 30% in prostate material properties could lead to registration errors of >4 mm, and in (Samavati et al., 2015) finite element (FE) nodal displacements differed by as much as 4.8 mm when uniform or different material properties were employed for tumor and healthy prostate. Registration errors of this magnitude would greatly impact the accuracy of prostate pathology correlation, especially given that the dimension of early stage foci of prostate cancer is often < 4 mm.

Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) (Muthupuillai et al., 1995; Mariappan et al., 2010) is a non-invasive quantitative method to detect changes in tissue biomechanics brought about by disease, such as cancer and fibrosis. There are two broad classes of MRE methods: dynamic and static (or quasi-static (McGrath et al., 2012)). In dynamic MRE high frequency mechanical waves are delivered to the site of interest, which are measured using MRI. In quasi-static MRE a uniform compression is applied to the whole tissue volume, and MRI is used to measure the resulting displacement field. Inversion algorithms are applied to the measurements to derive biomechanical properties such as elastic modulus. While dynamic MRE is ideally suited to in vivo applications, quasi-static MRE is more suited to in vitro studies of ex vivo tissue.

The main goal of this work was to use quasi-static MRE to measure the distribution of Young’s elastic modulus (E) in ex vivo prostate before and after pathology fixation, and to determine the effects of fixation and variations due to anatomy and disease. It was hypothesized that the elastic modulus would vary between different prostate anatomical zones, and with disease and fixation. This data would be used to inform pathology correlation, and would also provide important baseline information for the development of in vivo dynamic MRE. Although in vivo MRE methods for prostate are still in development (Chopra et al., 2009; Sinkus et al., 2003; Kemper et al., 2004; Sahebjavaher et al., 2013; Sahebjavaher et al., 2014), MRE holds enormous potential for diagnosis and image-guided intervention for prostate cancer. The data obtained could also be used for the biomechanical modeling of prostate interventions such as biopsy or brachytherapy (McAnearney et al., 2010).

As fixation also changes MR relaxation and diffusion properties (Purea and Webb, 2006; Shepherd et al., 2009), the secondary goal was to obtain parallel measurements of the T1 and T2 relaxation times and the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) of water. Measurement of these parameters is less complex in implementation than MRE. Hence, it was sought to determine if these parameters could act as predictors for fixation-mediated changes in tissue biomechanics, and therefore provide an alternative means of assessing the impact of fixation on biomechanical properties. The fixation effects on MRE and MRI parameters were examined in concentric zones from the surface to the center of each specimen, and compared to theoretical fixative concentration curves. The hypothesis was that local concentrations of fixative in the ex vivo specimens could be predicted by changes in MRI parameters, which could in turn be used to predict fixation-related changes in tissue biomechanics. Furthermore, there is a pressing need for improved understanding of how fixation changes tissue properties and MRI parameters, as fixed ex vivo specimens are increasingly being used to provide imaging data that would be difficult to obtain in vivo (Thelwall et al., 2006), i.e., with high spatial resolutions or elevated signal to noise (SNR) and free of motion or flow artifacts.

This work presents an initial feasibility study, employing canine prostate specimens, and radical prostatectomy specimens from prostate cancer patients. The MRE methodology employed in this study was previously presented in earlier work (McGrath et al., 2012), which also reported the MRE data of the canine prostate specimens. This study reports the MRE data for the clinical prostatectomy specimens, and the MRI parameter (T1, T2 and ADC) data for both the canine and clinical specimens, and further analyzes and compares the MRE data with the MRI parameters for the canine and clinical specimens. The processes described for the clinical specimens form part of a pathology correlation pipeline described in (McGrath et al., 2016).

METHODS

All MR imaging was carried out on a 7-tesla (T) pre-clinical MRI scanner (70/30 BioSpec, Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany), and a quadrature volume resonator (15.5 cm inner diameter) was used for transmission and reception. The higher magnetic field strength facilitated elevated SNR at fine spatial resolutions within the restricted imaging times for clinical pathology specimens. All tissue fixation was carried out at room temperature by submersion in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution. When not stated otherwise, all image data manipulations and calculations were carried out in Matlab (The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-tests were employed to determine if there were statistically significant differences between data sets before and after fixation, and to compare fresh state data for the different anatomical zones and disease states in the clinical prostate. Paired t-tests were employed throughout, as comparisons were being made between repeated measures from the same specimens, e.g., before and after fixation. One-tailed paired t-tests were used for assessing the change with fixation, as an expected direction of change could be identified (e.g., an increase in MRE E with fixation). Likewise a larger E value was expected in fresh tumor compared with fresh healthy tissue, and hence a one-tailed paired t-test was employed for that comparison. For comparison of fresh state MRI parameters (T1, T2 and ADC) between anatomical zones two-tailed paired t-tests were employed, as no specific direction of change was assumed. The dependency between data sets was assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation test, i.e., chosen in preference in the Pearson test as it does not assume linear dependency. However, the Pearson correlation test was used for comparison of theoretical fixative concentration curves with the concentric zone MRI data. For all statistical tests, the threshold of the p-value for statistical significance was set to 0.05 (i.e., a probability of 5% of a false positive rejection of the null hypothesis).

Canine prostate specimens

Canine prostate specimens (n=5) were obtained from various breeds of healthy intact dogs, which were euthanized for another research study at the University of Guelph, according to the guidelines set by the institutional Animal Care committee. The samples were imaged before and after overnight fixation. For the fifth specimen imaging was repeated at four fixation times, to examine progressive effects.

Clinical prostatectomy specimens

Whole prostatectomy specimens (n=4) were obtained from patients in an institutional Research Ethics Board approved study. Patients with biochemical failure after radiotherapy (RT) underwent MR-guided biopsy to confirm and map sites of local recurrence, followed by salvage prostatectomy. The specimens were imaged before and after a long fixation interval of 60 h; to ensure complete penetration of fixative before pathology sectioning.

Quasi-static MRE to measure Young’s modulus

The quasi-static MRE method previously reported by our laboratory (McGrath et al., 2012) was employed to map E over the specimen volumes. The acrylic MRE device delivered compression via a mechanical piston, connected through an eccentric disk to a non-magnetic ultrasonic piezoelectric motor (USR60-E3N, Shinsei, Japan), controlled by an external driver in a closed loop system. The compression rate, set by the motor driver, was 1 Hz, and the compression amplitude, set by the eccentric disk, was 1.5 mm. Before testing, each specimen was set in a gelatin and agarose cube (7 × 7 × 7 cm3), to provide stability during compression. The piston motion was tracked via the scanner pre-clinical respiration monitor (SA Instruments Inc., NY), which was mounted on a holder behind the piston, and which triggered the scanner to acquire during the compressed phase.

A diffusion-weighted stimulated echo acquisition mode (STEAM) method was used (McGrath et al., 2012). This method is similar to the displacement encoded stimulated echo sequence (DENSE), which has been employed in vitro at 7 T in other work, to measure mechanical strain in articular cartilage (Chan et al., 2009). The diffusion gradients provided displacement encoding: gradient amplitude (Gd) = 40 mT/m; duration (τ) = 1 ms; gradient pulse separation interval (Tgrad)= 200 ms.

The displacement sensitivity was 3.4 π/mm. Transition between compression states was timed to occur during the mixing time, Tm (190 ms). The repetition time (TR) was 1 s; matching the compression cycle period. Echo planar imaging (EPI) readout facilitated more rapid acquisition, to limit degradation of the pathology specimens. For the pre-clinical specimens #1–3 the parameters were: echo time (TE) = 18 ms, signal averages = 3, segments = 10, and the imaging time was ~18 min. For specimen #4 the number of signal averages was increased so that the imaging time was extended to ~5 h, to explore the benefits of increased SNR, as the numerical simulations in (McGrath et al., 2012) demonstrated that the expected error on the modulus values is highly dependent on SNR. While for specimens #1–4 MRE was carried out before and after one overnight fixation interval, for specimen #5 a fixation timeline study was carried out while fresh and after four fixation intervals (12, 18, 30 and 120 h) to examine the progressive effects of fixation. For specimen #5 the number of signal averages was set to 12, as this provided high quality images within a more suitable imaging time (~1 h) for the timeline study. For the clinical specimens the parameters were further optimized to achieve higher quality images within an imaging time of 1 h: TE = 16 ms; signal averages = 7; segments = 17.

The in-plane resolution of all acquisitions was 0.5 × 0.5 mm2 (with a field of view (FOV) = 8 × 8 cm2 and imaging matrix =160 × 160), and 23 coronal slices, with 3 mm slice thickness, were acquired to cover the block of tissue in gel. The displacement encoding gradient direction was parallel to the compression motion, and this allowed measurement of the normal component of strain. While the motor was turned off and the sample was in the compressed state, a second static-state reference acquisition was made.

Strain maps were calculated for each of the slices, from which 3D maps of E were reconstructed using the finite element modeling (FEM)-based inversion algorithm previously described (McGrath et al., 2012). A 3D FE model of the tissue-gel cube was generated with cubic rectangular elements (‘hexa’-elements) which had the same dimension as the MRE imaging voxels. This arrangement facilitated mapping of the MRE-measured strain values directly to the elements without interpolation. At each iteration of the inversion algorithm the 3D mechanical stresses were simulated using a finite element solver (Abaqus v6.12, Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp, Johnston, Rhode Island, USA) based on an estimated distribution of E, which was updated using an equation based on Hooke’s law:

| (1) |

where Ei+1 is the latest modulus update, is the normal component of strain measured by MRE in the direction of the applied compression, are the three normal stress components of the previous iteration, and ν is Poisson’s ratio. This algorithm applied the assumption of an isotropic linear elastic near-incompressible medium, with a uniform ν of 0.499 for the tissue and gel, and was validated by means of numerical simulations.

The initial estimate for E for each element was the reciprocal of the strain. The metric of convergence was:

| (2) |

i.e., the mean squared proportional differences between consecutive modulus updates Ei and Ei+1 were compared with a chosen tolerance, tol (set arbitrarily to 10−6).

For the canine specimens the MRE data was validated by comparison with independent mechanical indentation measurements (McGrath et al., 2012). However for the clinical specimens indentation measurements were not feasible, due to the whole-specimen fixation process and concerns with regard to safeguarding tissue integrity for histopathology analysis.

MRI parameter measurement in fixative solution

To inform analysis of fixation effects in tissue, measurements were first made in fixative solution. The formalin concentrations used were 10%, 7.5%, 5%, 2.5% and 1% (or 3.7%, 2.8%, 1.9%, 0.93% and 0.37% formaldehyde). Volumes of 1 ml were placed in Eppendorf tubes, and a 2-mm imaging slice was acquired, which transected all tubes. For T1 a RARE (Rapid Acquisition with Relaxation Enhancement) method adapted for quantification using saturation recovery was employed: TE = 8.7 ms; TR = 12 values in the range 25–7500 ms; echo train length (ETL) = 2; signal averages = 3. For T2 a multi-echo spin echo acquisition was made: TE= 64 values in the range 7.5–480 ms; TR= 5 s. For solution the diffusion coefficient or diffusion rate (DR) is measured, which is identical in calculation to ADC, i.e., ADC is the appropriate term for the diffusion rate in tissue, where diffusion of the water molecules is restricted and typically anisotropic. To measure DR, EPI was employed, and three orthogonal gradient directions with b values = (50, 200, 400 s/mm2); segments = 11; signal averages = 1; TE= 25 ms; TR = 4500 ms. Maps of T1, T2, and DR were generated according to standard exponential functions using Bruker software (Paravision 5.0), and regions for each tube were manually segmented from which average parameters were calculated. The average relaxation rates (R1 = 1/T1, and R2 = 1/T2) and average DR, were plotted against formalin concentration, and least squares line fits were made.

MRI parameter measurement in biological tissue

Immediately after the MRE acquisition, T1, T2 and ADC were quantified at consistent graphical prescription and voxel dimensions with the MRE data. T1 and T2 were measured using the RARE saturation recovery method: TE = 5 values in the range 7.5–67.5 ms; TR= 6 values in the range 500–5554 ms; ETL= 2. For the fifth canine specimen, and for the clinical specimens, the number of signal averages was increased from 1 to 3 to improve SNR. Maps of T1 and T2 were generated using Bruker Paravision software.

The diffusion experiment to measure ADC employed EPI and three orthogonal gradient directions: b values = (0, 750 s/mm2). For the canine specimens the parameters were: TE = 27 ms; TR = 3500 ms; segments = 8. For the fifth canine specimen the number of signal averages was increased from 1 to 10 to improve SNR. For the clinical specimens the parameters were adapted to: TR = 4500 ms; TE = 23 ms; segments = 17; signal averages = 4. Maps of ADC were generated using in-house software developed in Matlab. For each canine and clinical specimen the acquisitions for T1, T2 and ADC took approximately 1 h in total.

For the clinical specimens, to assist the registration of histology slides to the imaging data, a 3D isotropic high resolution RARE T2w acquisition was made in the fresh and fixed states: TE = 40 ms; TR= 2400 ms, ETL = 16; FOV = 70 × 70 × 70 mm3, imaging matrix = 233 × 233 × 233; voxel dimension = 0.3 × 0.3 × 0.3 mm3 . This last acquisition required approximately 2 h. Hence the total imaging time for the clinical specimens was approximately 4 h. The time required for preparing the specimen for setting in gel was approximately 1 h. Hence for the clinical specimens a time lapse of at least 5 h occurred between surgery and submersion in fixative. However, to ensure tissue preservation, the specimens were kept immersed in saline between surgery and gel setting, and all processes were approved by the pathologist (TvdK).

Histopathology processing

The clinical prostatectomy specimens were sectioned at 3 mm slice thickness and processed for whole mount histology with Hematoxylin and Eosin staining (H&E). The slides were digitized at 5 µm resolution on a TISSUEscope™ 4000 (Biomedical Photometrics Inc., ON, Canada) and the tumor regions were identified by the pathologist (TvdK).

Clinical prostate parameter map analysis

Prostate was manually segmented from the gel. The principal anatomical zones were manually selected and verified by the radiation oncologist (CM), i.e., peripheral zone (PZ) and the combined region containing the transition and central zones (excluding the urethra), referred to as the central gland (CG).

The histopathology-identified tumor regions were used to locate disease in the parameter maps by registration of the histology images to ex vivo MRI. For the clinical prostates ex vivo imaging was carried out axial to the posterior surface. However, to assist in correlation with in vivo diagnostic imaging, pathology sectioning was carried out parallel to the in vivo imaging plane (axial to the endorectal coil). The registration steps were carried out in Matlab: 1) The high resolution 3D isotropic T2w data was resampled at the axial oblique angle that best matched in vivo imaging, and the angle was chosen in the manner described in (McGrath et al., 2016), where the distances from the urethra to the anterior, posterior, left and right outer edges of the prostate were measured and compared; 2) The digitized histology slides were visually matched and rigidly registered to the resampled T2w ex vivo images, by finding the best match with regard to the position of the urethra and the shape of the prostate boundary; 3) A digital tumor volume was created from the co-registered histology images through 3D interpolation; 4) The tumor volume was digitally resampled to the ex vivo MRE slice angle. The estimated angle between the in vivo and ex vivo prostate imaging slice planes for all four clinical specimens was on average 18(±9)°. The accuracy of this registration method is difficult to determine, but is limited by the 3-mm slice width of the MR imaging and the pathology sectioning, combined with the unknown uncertainty on the angle estimation, and the potential errors from the co-registration of histology and MRI, and the final digital rotation and resampling.

Summary statistics were calculated for the whole prostate, PZ, CG and tumor region (excluding fibromuscular stroma and extra-prostatic tissue). The tumor data was excluded from the data of other regions in the statistics calculations.

Concentric zone analysis

The specimen volumes were analyzed as concentric zones. For every tissue voxel the minimum distance from the outer surface was calculated, and voxels were assigned to zones according to 1 mm increments of distance from the surface. Mean zone parameters were calculated and plotted against the distance from the zone mid-point to the tissue edge. Data from extra-prostatic tissue was excluded.

Comparison of predicted fixative concentration curves with ΔR2 concentric zone curves

Changes in tissue T2 with fixation are thought to primarily influenced by the presence of free fixative solution (Purea and Webb, 2006). It was hypothesized that the change in R2 with exposure to fixative (ΔR2) may provide an indicator of local fixative concentration, which in turn may allow prediction of changes in E. Therefore, ΔR2 was compared with predicted concentrations in the concentric zones.

In (Yong-Hing et al., 2005) a model was derived for diffusion of fixative into a spherical mass of tissue, with radius R and diffusion coefficient D. In polar co-ordinates, the fixative concentration (c) at a position (r) from the center, at a given time (t), for a given concentration in solution outside the tissue (c1) is:

| (3) |

Theoretical concentration curves were calculated for a spherical approximation of canine specimen #5, for each fixation time and for different D. For each D, the Pearson correlation coefficient (ρ) was calculated for the comparison of the predicted curves with the ΔR2 concentric zone curves. The D value yielding the highest ρ value for the combined set of curves was identified. The comparison excluded the center zone, where ΔR2 was greater than in the neighboring zone, presumably due to fixative passing into the urethra (see truncation line in figure 6(a). The best match D value was used to generate theoretical concentration curves for the clinical specimens, for comparison with their ΔR2 curves. The modelling of the prostate shape as a sphere is a large approximation, and in particular for the clinical prostate which has an elongated shape. However, the sphere model was considered appropriate for this initial exploratory analysis.

Figure 6.

Predicted formalin concentration compared with ΔR2 in concentric zones. (a) Preclinical specimen #5. (b) Clinical specimen #1. (c) Clinical specimen #2. (d) Clinical specimen #3. (e) Clinical specimen #4.

RESULT

Relaxivities and diffusion rate in fixative solution

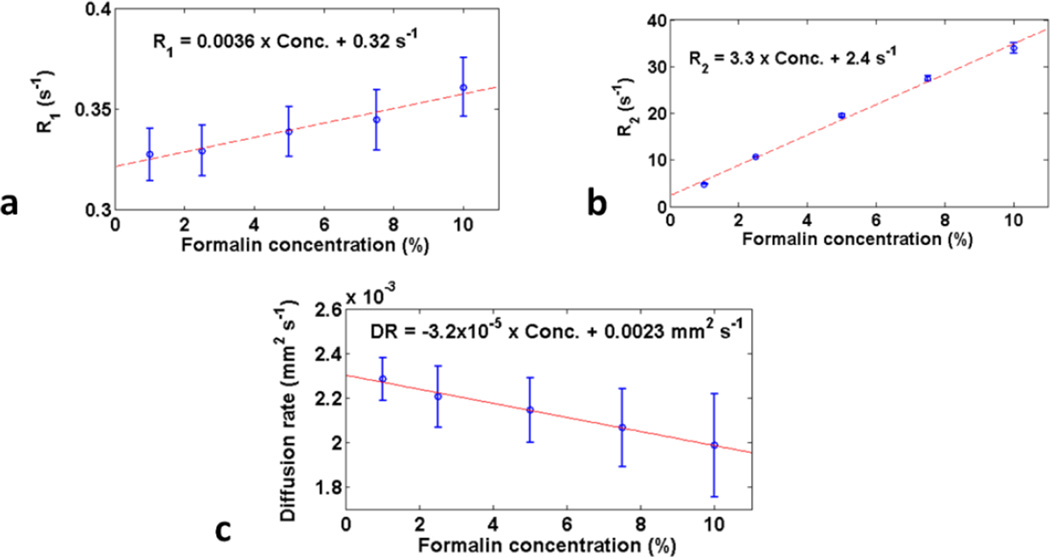

R1 and R2 in fixative solution were approximately linearly dependent with and directly proportional to concentration (figure 1), while R2 was more sensitive to concentration than R1, i.e., going from 0 to 10% formalin the percentage change in R2 (%ΔR2) was 1375%, compared to 11% for %ΔR1. DR also showed a linear dependence, with an overall decrease, i.e., −14%. (Note that while the error bars seem much smaller on the R2 plot compared with the R1 plot, their apparent magnitude is effected by the different y-axis plot ranges for R1 and R2, and in actuality the error bars for R1 and R2 have similar magnitudes.)

Figure 1.

Mean (standard deviation error bars) relaxation and diffusion rates at 7 T in solutions with varying formalin concentrations. (a) R1; (b) R2; (c) Diffusion rate.

Canine prostate MRE and MRI parameters

Canine prostate MRE and MRI parameters are summarized in Table 1 and figure 2 (see (McGrath et al., 2012) for more details of MRE parameters). The pre-fixation E values were comparable to earlier measures (Chopra et al., 2009). Mean E increased significantly and consistently across all specimens, and continuously with fixation time.

Table 1.

Preclinical data summary

| Parameter | T1 (ms) | T2 (ms) | ADC (×10−4 mm2s−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue state | Fresh | Fixeda | Fresh | Fixeda | Fresh | Fixeda | |

| Mean(std) | 2757(334) | 2805(385)a | 73(26) | 46(12)a | 7.6(1.9) | 6.9(2.4)a | |

|

Significance: fresh vs. fixeda |

N.S.b | p<0.008a | p<0.04a | ||||

|

Parameter |

Fixation time (h) |

ΔR1 (s−1) (% Δ) | ΔR2 (s−1) (% Δ) |

ΔADC (×10−4mm2s−1) (% Δ) |

|||

| Specimen | |||||||

| #1 | 15 | +0.016(+4%)a | +8.6(+53%)a | −0.6(−10%)a | |||

| #2 | 16 | −0.064(−18%)a | +6.5(+76%)a | 0a | |||

| #3 | 18 | −0.091(−22%)a | +6.6(+38%)a | −0.3(−4%)a | |||

| #4 | 12 | +0.077(+25%)a | +8.5(+62%)a | −1.7(−25%)a | |||

| #5 | 12 | +0.035(+10%)a | +8.9(+47%)a | −1.1(−15%)a | |||

| #5 | 18 | +0.026(+7%) | +9.7(+51%) | −0.5(−7%) | |||

| #5 | 30 | +0.043(+12%) | +12.4(+66%) | −0.6(−8%) | |||

| #5 | 120 | +0.056(+16%) | +14.5(+77%) | −0.5(−7%) | |||

|

Mean(std)a, Mean(std) of %Δa |

−0.005(±0.07)a, −0.2 (±19.7)a |

+7.8(±1.2)a, +55(±15)%a |

−0.7(±0.7)a, −11(±10)%a | ||||

After one fixation interval

Not significant

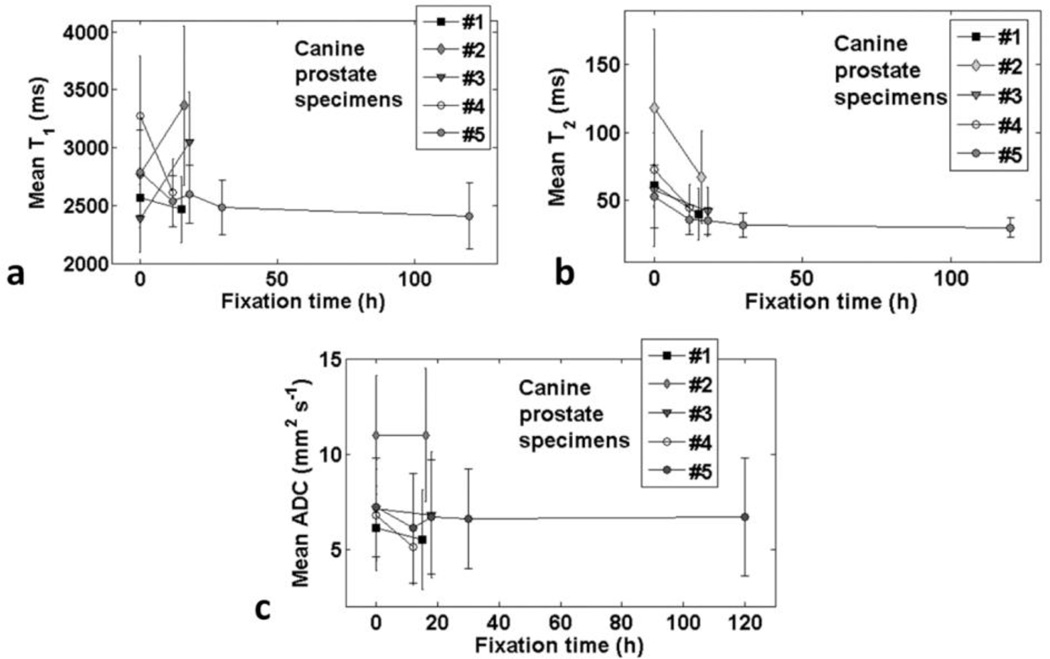

Figure 2.

Comparison of canine prostate specimens mean parameters (standard deviation error bars) over tissue volume versus fixation interval: (a) T1; (b) T2; (c) ADC.

Mean T2 decreased significantly, consistently and continuously with fixation time. However, while T1 and ADC also tended to decrease with fixation, the change was neither consistent across specimens nor continuous with fixation time. Similar to fixative solution, the changes in R2 were proportionately greater than those in R1 and ADC.

The mean changes in E (ΔE) and R2 (ΔR2) for the fixation time points of specimen #5 were strongly correlated (ρ=1), while there were no significant correlations between ΔE and ΔR1 or ΔADC. When comparing the data of the five specimens after the first fixation period, there were no significant correlations between ΔE and ΔR1, ΔR2 or ΔADC.

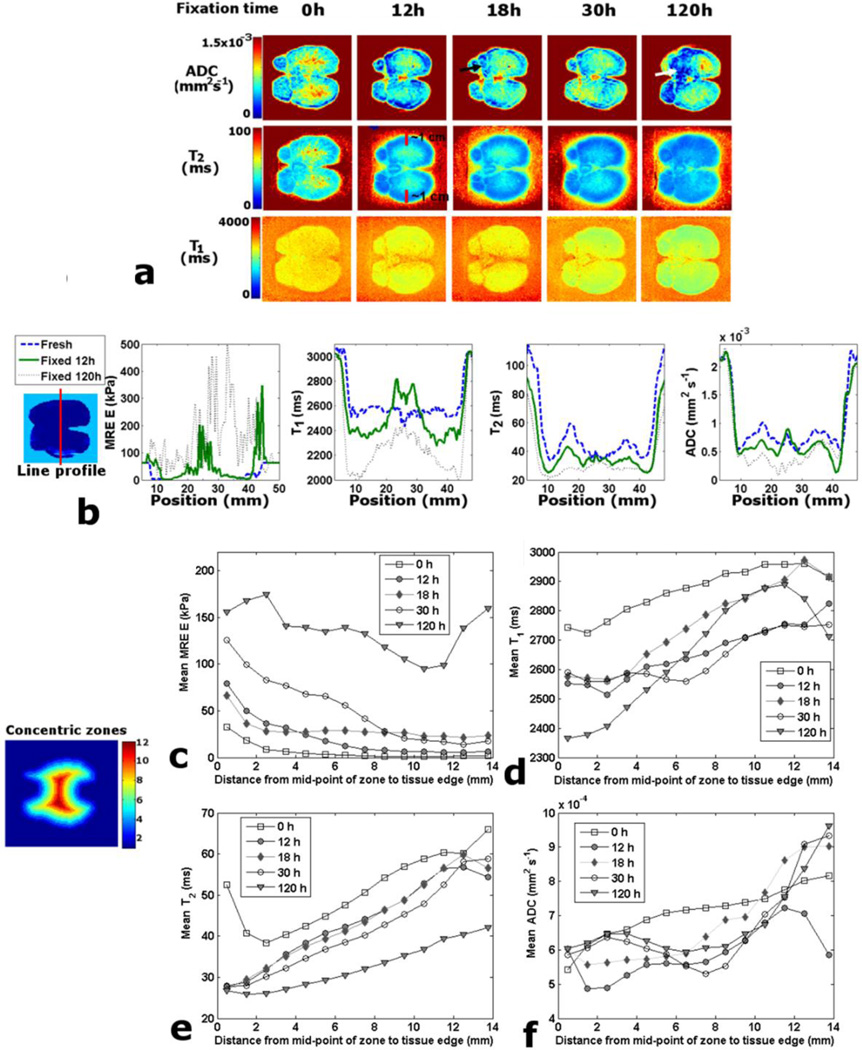

The parameter maps of canine specimen #5 in (McGrath et al., 2012) showed how fixation increased E progressively but non-uniformly, and as an approximate function of distance from the tissue edge. However, T1 for specimen #5 (in this report, figure 3(a) decreased more slowly with fixation and in a more diffuse manner. T2 also decreased progressively, but in a pattern that was more strongly a function of distance from the tissue edge. The visible margin of decrease in T2 at 12 h was approximately 1 cm deep (see red lines in figure 3(a). ADC also decreased progressively, but in a less predictable pattern. Some areas of low ADC appear similar to areas of high E (see arrows in figure 3(a).

Figure 3.

Canine prostate specimen #5 fixation timeline study. (a) Comparison of parameter maps for a matching example slice. (b) Example line profiles through matching slices for time points: 0, 12 and 120 h. (c) Mean MRE E values for concentric zones against distance from mid-point of zone to tissue edge. (d) Zone T1 mean values against distance. (e) Zone T2 mean values against distance. (f) Zone ADC mean values against distance.

The line profiles (figure 3(b) provide further insight into the patterns of change across the canine specimen #5. At 12 h fixation the increases in E were greatest at the tissue edges, with large increases also occurring in the center near the urethra. At 120 h there was a non-uniform increase, with areas where ΔE > 500 kPa. There is a small decrease in T1 at 12 h across most of the profile, but an increase near the urethra. At 120 h T1 has decreased across the whole profile compared with the fresh state, but T1 varies widely. The T2 profile at 12 h demonstrates a decrease at all points except those close to the center, and the decrease is more strongly a function of distance from the tissue edge. At 120 h the values have decreased still further and are approximately uniform. The ADC profile demonstrates a heterogeneous response to fixation across the tissue, and the pattern fluctuates between fixation times.

The E plot for the concentric zones of canine specimen #5 demonstrates a progressive increase with fixation interval, which is a strong function of distance from the tissue edge (figure 3(c). However, at 120 h the increase near the urethra is comparable to that at the edges. The T1 plot (figure 3(d) demonstrates a pattern of decrease that is variable across the specimen and approximately a function of distance from the edge and fixation time. However, there is little variability between the T1 values close to the edge for time points 12–30 h, which all vary from the fresh state by ~200 ms; whereas from 30 to 120 h there is a further decrease of 200 ms. T1 at the center fluctuates widely from 12 h to 120 h, with a large decrease at 120 h. The T2 plots (figure 3(e) demonstrate a progressive decrease in T2, which is a function of fixation time and distance from the tissue edge. Of note is that the T2 values at the very edge of the tissue decrease to ~27 ms at 12 h and remain approximately at this value up to 120 h. The ADC plots (figure 3(f) reveal a complex variability of response to fixative, and at the center there is an initial decrease at 12 h, which is followed by an increase from 18 h onwards.

The concentric zone mean parameters ΔR1, ΔR2 and ΔADC of specimen #5 were compared for significant correlations with ΔE. For ΔR1 the only significant correlation with ΔE was at 120 h (ρ = 0.61). ΔR2 only correlated with ΔE at 12 and 30 h (ρ = 0.73, 0.96) and for ΔADC there were no significant correlations with ΔE.

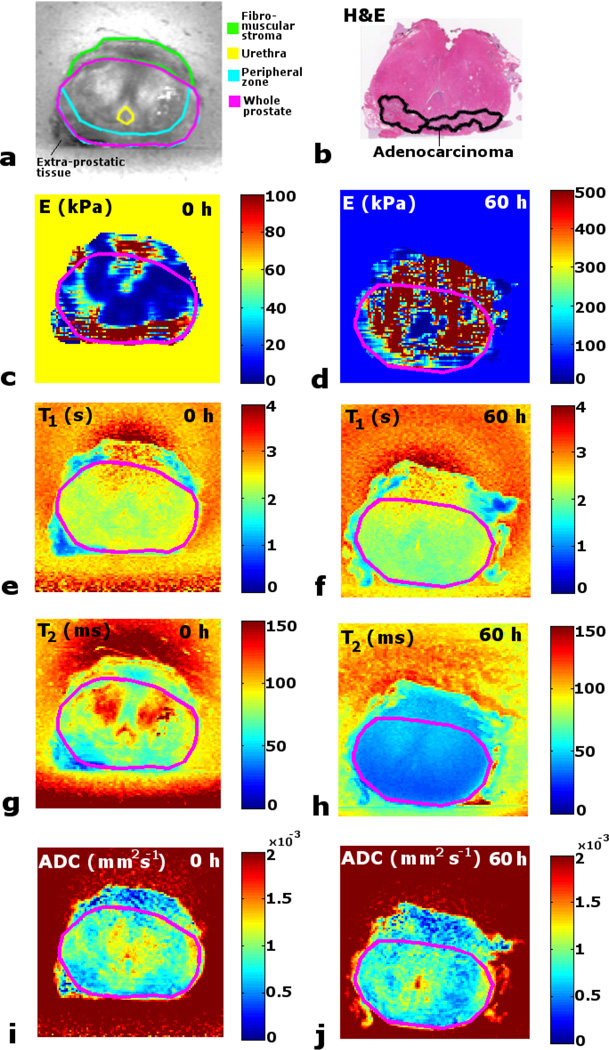

Clinical prostate MRE and MRI parameters

The patient pathology results and details of the earlier RT treatment are listed in Table 2. All patients had confirmed adenocarcinoma. Figure 4 presents the parameter maps before and after fixation for an example matching slice for clinical specimen #1, compared with an approximately matching histology slide. Some extra-prostatic tissue was removed with the specimen (figure 4(a). The cancer was found to be predominantly in the PZ (figure 4(b). In the fresh state E-map there are higher E values in the PZ (where the tumor lies) than in surrounding tissue. However there is also variability across the presumed normal tissue, especially above the urethra, close to and in the fibromuscular stroma, and close to the extra prostatic tissue. After fixation the E values increase heterogeneously across the slice. A structured noise or streaking pattern was noted in the E-maps which was similar to that observed in the canine prostate E-maps in (McGrath et al., 2012). This was considered to be caused by a combination of imaging-related noise and errors resulting from the approximations in the FEM calculation of the stress distribution and the algorithm to update the estimates of E (Eq. 1). However, as the ultimate aim of this methodology is to create population average data from larger numbers of prostate specimens to assist pathology correlation, the effect of these noise patterns will be reduced through averaging. Nevertheless, as these noise artifacts may affect the accuracy of quantitative mapping, this issue should be explored further in future work, perhaps through measuring the strain in different directions, by carrying out repeated acquisitions with prior rotation of the tissue-gel block to different orientations, followed by averaging the different 3D E-maps. This approach would also allow exploration of possible anisotropy of E.

Table 2.

Patient treatment and pathology summary

| Patient | Total dose received (Gy) |

No. of fractions |

Time between RT and prostatectomy (months) |

Tumor predominant location |

Overall Gleason score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 70 | 35 | 97 | PZ | 9 |

| #2 | 75 | 42 | 107 | CG | 7 |

| #3 | 66 | 22 | 68 | PZ | 8 |

| #4 | 79 | 42 | 93 | CG | 8 |

Figure 4.

Maps of matching slice in clinical prostate specimen #1 before and after fixation, and compared with histology. (a) T2 map with anatomical regions. (b) H&E whole mount histology slide with pathologist identified tumor region. (c) Fresh MRE E map. (d) Fixed MRE E map. (e) Fresh T1 map. (f) Fixed T1 map. (g) Fresh T2. (h) Fixed T2 map. (i) Fresh ADC map. (j) Fixed ADC map.

The T1 maps demonstrate a non-uniform decrease with fixation, with the reduction occurring predominantly in the tumor in the PZ. The fresh state T2 map shows higher values in the CG, while the fixed state map reveals how all regions are decreased to an approximately uniform T2. For ADC a variable and relatively weak response to formalin is visible.

The clinical specimen parameter values are summarized in Table 3 and figure 5. As the data for E in each anatomical zone was not normally distributed (skewed to the right (McGrath et al., 2012)), the median value is quoted with the mean rather than the standard deviation in Table 3. For the same reason, in figure 5, while error bars of the standard deviation are included for T1, T2 and ADC, they are not included for the non-normally distributed E data. For E, whereas the prefixation values were generally similar between specimens for the anatomical zones, a widely differing response to formalin was measured between zones and specimens. The fresh state clinical prostate was much stiffer than canine prostate (2.5 times).

Table 3.

Clinical data summary

| Zone | Whole prostate | Peripheral (PZ) | Central gland (CG) | Tumor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRE E (kPa): mean(median) | ||||||||

|

Fixation time (h) |

0 | 60 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 60 |

| Specimen | ||||||||

| #1 | 34(12) | 641(302) | 84(44) | 466(129) | 22(9) | 698(363) | 81(31) | 449(165) |

| #2 | 58(14) | 573(375) | 84(28) | 648(468) | 40(11) | 531(333) | 56(12) | 597(380) |

| #3 | 110(64) | 1117(609) | 130(80) | 1070(556) | 103(59) | 1211(682) | 160(91) | 1641(895) |

| #4 | 62(11) | 407(260) | 96(39) | 475(299) | 27(3) | 356(241) | 42(12) | 290(164) |

| Mean(std) | 66(32) | 685(305) | 99(22) | 665(283) | 48(37) | 699(369) | 85(53) | 744(611) |

|

ΔE: Mean(std) |

+619(281) | +566(264) | +651(336) | +660(561) | ||||

|

Factor of increase: Mean (std) |

11(5) | 7(2) | 17(10) | 8(3) | ||||

|

Fixed vs. fresh |

p<0.02 | p<0.02 | p<0.02 | N.S b. | ||||

|

Fresh PZ vs. CGa |

p<0.02 | |||||||

|

Fresh CG vs. tumor |

p<0.03 | |||||||

| T1 (ms) | ||||||||

|

Fixation time (h) |

0 | 60 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 60 |

| Mean(std) | 2252(62) | 2016(88) | 2218(98) | 2003(105) | 2323(56) | 2057(82) | 2283(47) | 1986(73) |

|

ΔT1: Mean(std) |

−263(60) | −215(65) | −266(90) | −297(42) | ||||

|

ΔR1: Mean(std) (s−1) %ΔR1 |

+0.052(0.015), +12(3)% | +0.049(0.015), +11(3)% | +0.056(0.02), +13(5)% | +0.066(0.012), +15(3)% | ||||

|

Fixed vs. fresh |

p<0.003 | p<0.004 | p<0.005 | p<0.0004 | ||||

| T2 (ms) | ||||||||

|

Fixation time (h) |

0 | 60 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 60 |

| Mean(std) | 88(7) | 43(1) | 79(4) | 40(2) | 96(10) | 45(2) | 83(9) | 40(5) |

|

ΔT2: Mean(std) (ms) |

−46(8) | −40(4) | −52(10) | −43(9) | ||||

|

ΔR2: Mean(std) (s−1), %ΔR2 |

+12.1(1.5), +108(21)% | +12.7(1.4), +101(14)% | +12.1 (1.6), +117(24)% | +13.1(3.2), +109(30)% | ||||

|

Fixed vs. fresh |

p<0.0008 | p<0.0002 | p<0.001 | p<0.002 | ||||

|

Fresh PZ vs. CGa |

p<0.02 | |||||||

|

Fresh CG vs. tumora |

p<0.002 | |||||||

| ADC (×10−4 mm2s−1) | ||||||||

|

Fixation time (h) |

0 | 60 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 60 |

| Mean(std) | 10.1(0.3) | 8.8(0.4) | 9.9(0.4) | 8.9(0.6) | 10.3(0.5) | 8.6(0.1) | 9.1(1.7) | 8.3(0.7) |

|

ΔADC: Mean(std), %ΔADC |

−1.3(0.4), −13(4)% | −1.1(0.4), −11(4)% | −1.7 (0.6), −16(5)% | −0.7(1.7), −5(22)% | ||||

|

Fixed vs. fresh |

p<0.005 | p<0.01 | p<0.005 | N.S.b | ||||

Paired t-test, 2-tailed

Not significant

Figure 5.

Clinical prostate specimens, mean parameter values (standard deviation error bars) before and after fixation for whole specimen, prostate zones and tumor: (a) MRE E. (b) T1. (c) T2. (d) ADC.

Significant increases in E were measured for all zones with fixation, except for tumor. In the fresh state the PZ was on average twice as stiff as the CG (p<0.02). However fixation leveled the difference. Only the CG differed significantly from the tumor in the fresh state (p<0.03). It was also noted that specimen #3 had higher E values in the fresh and fixed state for all regions, which were approximately double the values for the other specimens, and that patient #3 had a hypofractionated RT protocol (Table 2).

For T1, T2 and ADC the baseline values in the CG tended to be higher than those in the PZ and tumor region, whereas fixation reduced the differences between zones. For T2 the values after fixation were similar between the specimens and zones. Significant decreases with fixation were found for all MRI parameters in all zones, bar ADC, which underwent an increase in the tumor region of specimen #2 (figure 5(d). The only significant differences between zones in the fresh state were found for T2: with a difference between the PZ and CG (p<0.02) and between the CG and the tumor (p<0.002). No correlation was found between the overall Gleason scores and the fresh state tumor values for any parameter (including E). No significant correlations were found between the mean ΔE and ΔR1, ΔR2 or ΔADC over the four specimens for the whole prostate zone or any of the subzones.

The concentric zone ΔR1, ΔR2 and ΔADC were compared for significant correlations with ΔE for each clinical specimen. For #1 there were no correlations. For #2 ΔR1 and ΔR2 correlated with ΔE (ρ = 0.67, 0.66). Also for #3 ΔR1 and ΔR2 correlated with ΔE (ρ =0.89, 0.65). For #4 only ΔADC correlated with ΔE (ρ = −0.80).

Comparison of the predicted concentration curves with ΔR2 curves

The D value giving the highest correlation ρ was 0.19 mm/h (ρ=0.95, p<0.001) (figure 6(a). Figures 6(b)–(e) show the theoretical concentration curves for the clinical specimens compared with their ΔR2 curves. There were no significant correlations between concentration curves and their ΔR2 curves.

DISCUSSION

Elastic modulus of pre-fixation clinical prostate

Literature elasticity values for clinical prostate vary widely (McAnearney et al., 2010). In this work PZ was found to be stiffer than CG; agreeing with earlier observations (Krouskop et al., 1998; Kemper et al., 2004) (mechanical frequencies: 0.1–4.0 Hz, and 65 Hz respectively). However some in vivo work has reported higher elastic modulus values in the CG compared with the PZ for healthy volunteers (Sahebjavaher et al., 2014) (70 Hz mechanical wave frequency). However (Sahebjavaher et al., 2014) also reported data for a prostate cancer patient for whom E was higher in the PZ compared with the CG. (Dresner et al., 1999) used dynamic MRE (mechanical frequency 100–600 Hz) on ex vivo prostate specimens, and found that for non-cancerous prostate the CG was stiffer than PZ, while cancer increased stiffness in the PZ, and also demonstrated that prostate shear modulus increases with the mechanical driving frequency, and therefore prostate tissue exhibits viscoelastic properties. In a review of ultrasound elastography of the prostate (Correas et al., 2013) summarize that for young healthy men prostate tends to have a homogeneous and low elastic modulus, while in benign prostate hyperplasia stiffness increases heterogeneously in the CG and remains low in the PZ, while cancer nodules increase stiffness in the PZ. The E values of this study were a similar magnitude to those measured in (Krouskop et al., 1998) from ex vivo mechanical compression testing (CG: 63(±18) kPa, PZ: 70(±14) kPa). In contrast, using in vivo dynamic harmonic MRE (Kemper et al., 2004) reported shear modulus values of 2.2(±0.3) kPa for CG, and 3.3(±0.5) kPa for PZ, corresponding to E values of approximately 6 and 9 kPa. The disparity in measures may be due to differences between in vivo and ex vivo tissue (e.g., changing temperature, loss of blood pressure, dehydration and tissue degradation) or in the methodologies employed, i.e., the mechanical driving frequency will influence the shear modulus of viscoelastic tissue. However, using ultrasound sonoelasticity combined with slow compression measurements (2 s per increment) (Parker et al., 1993) measured ex vivo E values closer to those of Kemper et al. (2–4 kPa). Furthermore, it should be noted that the E distributions measured in this work were skewed, with median values much lower than mean values (as low as 3 kPa in CG). In the E-maps (figure 4(c) it was found that in healthy tissue a large proportion of values were very low (<20 kPa) while a small portion of values were very large (>100 kPa). This might be influenced by tissue heterogeneity, i.e., glandular and fibrous tissue, but also by possible inaccuracies in the registration with histopathology, or the effect of imaging noise on E (McGrath et al., 2012).

There are also possible influences from RT, including fibrosis and inflammation, as it is has been reported that RT can cause stromal fibrosis in the prostate (Iczkowski, 2009). Furthermore, differing doses and fractionation protocols may have led to varying effects. Patient #3, who had a hypofractionated treatment protocol and shorter time between RT and surgery (Table 2), also had a specimen that was approximately twice as stiff as the others, in all zones, with and without disease, fresh and fixed. This suggests that RT may influence prostate biomechanics, but further work is required to verify this, including specimens from patients not treated with RT.

With regard to prostate cancer, it was found that the data of the co-registered histology-identified tumor region was not significantly different from the whole prostate, and was only significantly stiffer than CG (1.8 times). Other investigators have reported several factors of increase in prostate elastic modulus with cancer (i.e., in PZ a factor of 3.2 (Krouskop et al., 1998), 2.6 (Zhang et al., 2008) (mechanical stress testing at 150 Hz), and in (Dresner et al., 2003) (mechanical frequency of 350 Hz) tumor was approximately twice as stiff as healthy prostate. Recently, acoustic radiation force imaging (ARFI) has been explored in combination with B-mode ultrasound imaging to map prostate anatomical zones (Palmeri et al., 2015), and to identify prostate cancer lesions in vivo with retrospective evaluation from whole specimen prostatectomy histopathology (Palmeri et al., 2016) (4.6–5.4 MHz). ARFI in combination with B-mode ultrasound was found to compare well with T2w MRI for mapping prostate anatomy, and was highly accurate in mapping prostate cancer, i.e., 71.4% of lesions were identified in ARFI. In this present study, however, the registration accuracy of MRE and histology was limited by the imaging and histology sectioning slice width (3 mm). Notwithstanding, a good visual correspondence was generally noted between the tumor regions on the histology images and stiffer areas in the MRE maps (figures 4(b) and 4(c), where E tended to be >100 kPa.

MRI parameters in pre-fixation clinical prostate

In line with expectation, the T1 times were substantially longer at 7 T than those reported at 1.5 T (Foltz et al., 2011), and the T2 values were comparable to those reported at lower field strength (Foltz et al., 2010a; Gibbs et al., 2001; Langer et al., 2009). However, at 7 T the in vivo T2 values reported by Scheenen et al. (Scheenen et al., 2011) for young healthy volunteers were notably lower (PZ: 64 ms, transition zone: 50 ms). In this study it was found that T1, T2 and ADC were higher in CG than PZ (significantly so for T2), which is in contradiction to previous data (Gibbs et al., 2001; Foltz et al., 2011; Foltz et al., 2010a; Scheenen et al., 2011) where PZ exceeded CG in all parameters. However, while at 1.5 T T1 was higher in PZ than CG (Foltz et al., 2011), in 7 T T1-weighted in vivo imaging there was no contrast between PZ and CG in (Scheenen et al., 2011).

The influence of RT must also be considered, as it has been found to reduce both T1 and T2 in the PZ and CG, and reduce contrast between zones (Foltz et al., 2010a; Foltz et al., 2010b). The ADC values were comparable to those previously reported (Langer et al., 2009; Gibbs et al., 2001).

Other investigators report lower T2 and ADC in prostate cancer compared with normal PZ (Gibbs et al., 2001; Langer et al., 2009; Foltz et al., 2010a). In this work ADC was lower in tumor than in PZ and CG (not significantly). But for T2 the tumor values were only lower than those of CG (p<0.002), and were in fact higher than those of PZ. This difference with the literature may be influenced by variations between in vivo and ex vivo tissue, or the effects of RT.

Effects of fixation on elastic modulus and MRI parameters

The principal effect of formaldehyde fixation is the cross-linking of protein amino groups with methylene bridges, which renders the tissue metabolically inactive and structurally stable (Thelwall et al., 2006). The initial reaction of the aldehyde with the primary amines in proteins is thought to be complete within 24 h, while the creation of cross-links takes several weeks. Fixation also destroys intrinsic biomolecules such as proteolytic enzymes, which would damage the tissue, and preserves the tissue from bacteria and molds (Purea and Webb, 2006). Fixation changes cell membrane permeability (Thelwall et al., 2006; Purea and Webb, 2006; Shepherd et al., 2009), and it is thought that substances that fixation modifies more slowly (e.g., lipids (Purea and Webb, 2006)) may become trapped within the cross-linked protein structure. As prostate tissue has a complex and heterogeneous structure, the response of the various parameters to fixation is also likely to be complex. (Ling et al., 2016) carried out optical coherence elastography (~8 kHz) on in vitro samples of different tissue types (fat, liver, muscle, tendon and cartilage) at different intervals of fixation in formalin and Thiel solution. They found that formalin fixation increases Young’s modulus non-uniformly, progressively and continuously over a fixation interval of 6 months, with different rates of increase in the different tissue types, while the elastic properties remained almost constant in Thiel solution.

In this study E increased consistently with formalin fixation for all tissue types, normal and diseased, as a function of exposure time to fixative and distance from the tissue edge. Increases at the center were similar to those at the edges, presumably due to fixative passing into the urethra. The fixation increased overall E substantially, and reduced the differences between healthy tissue and tumor. The underlying mechanism of change in E is likely to be predominantly associated with structural alterations in the tissue resulting from protein cross-linking. However fixation-related dehydration might also play a role (Thickman et al., 1983). Elastic modulus is also sensitive to temperature; however fluctuations between acquisitions were likely to be minimal. Although the chemical reaction of the aldehyde is thought to take 24 h, it appears that structural changes at the tissue edges occur as early as 12 h (figure 3(a). Furthermore, as protein cross-linking may take several weeks to complete, and given the findings of (Ling et al., 2016) for other tissue types, it is likely that E would continue to increase beyond the timeframes observed here. For the timeline study with canine specimen #5, the possibility of secondary influences from repeat insertion and removal from fixative must also be considered.

As per earlier findings (Yong-Hing et al., 2005; Purea and Webb, 2006; Shepherd et al., 2009), T1 and T2 were generally found to decrease with fixation. While T2 decreased consistently for all specimens and fixation times, T1 was unpredictable and could also increase. The proportional change in T1 was lower than that in T2, in agreement with previous data (Shepherd et al., 2009; Purea and Webb, 2006). The principal underlying mechanism for the reduction in relaxation times is thought to be proton exchange between tissue water and the aldehyde group of the fixative, although T1 could be influenced by dehydration (Thickman et al., 1983). T1 is also dependent on viscosity, and chemical exchange is thought to be an important influence (Purea and Webb, 2006), along with cross-linking. In (Purea and Webb, 2006) it was also concluded that T2 was extremely sensitive to chemical exchange, both in solution and within cells. T1 and T2 are also sensitive to temperature variations (Thelwall et al., 2006), and possible minor fluctuations may have had an influence. Another potential influence on the T1 values was the variable effect of water exchange with varying TR, as the TR times using the RARE imaging sequence varied between acquisitions.

For the clinical specimens it was not permissible to examine the reversibility of fixation effects by washing out free fixative. To match the clinical specimens, the canine prostates were likewise not washed. Hence, the presence of free fixative, particularly in the urethra, may have influenced the increases in T1, e.g., see 12 h profile in figure 3(b). (This might alternatively be ascribed to gel in the urethra, however the corresponding T2 and ADC profiles would not support that explanation.) It has been found that T2 reduction can be reversed after washing (Purea and Webb, 2006), or even increased above the fresh state values (Shepherd et al., 2009; Thelwall et al., 2006). In (Purea and Webb, 2006) and (Shepherd et al., 2009) T1 remained below baseline after washing, which suggests that T1 changes are influenced more by the chemical reactions of the fixative than the presence of free fixative solution. However, in the concentric zone analysis of canine specimen #5 there was little fluctuation between the T1 values for 12–30 h in the outer zones (figure 3(d), suggesting that the initial changes up to 30 h in the outer tissue were dominated by the effects of the free fixative. Between 30 and 120 h much larger changes occurred, pointing to the influence of a secondary fixation effect. In contrast the plots for T2 (figure 3(e) demonstrate that the effect of free fixative dominates in the outer zones at all fixation time points. The comparison of the magnitudes of ΔR1 and ΔR2 in formalin solution with those in biological tissue is also worthy of note. As the maximum ΔR1 of 0.036 s−1 in solution was exceeded by a maximum of 0.077 s−1 in canine prostate, this suggested that the chemical reactions of the fixative were important in influencing T1 (as opposed to the effects of free fixative alone). To the contrary, none of the tissue experiments achieved the maximum ΔR2 of 33 s−1 of the solution experiment (for the clinical tissue the average was 12.1 s−1).

Literature reports a variable effect of fixation on ADC (Purea and Webb, 2006; Thelwall et al., 2006; Shepherd et al., 2009), and in this study it was likewise found to be unpredictable. Although DR in solution was inversely proportional to fixative concentration and there was an overall trend of reduction of ADC in tissue, ADC not decrease consistently. However, ADC would also be sensitive to possible temperature variations between acquisitions (Thelwall et al., 2006). While ADC decreased near the edges of the tissue, it also increased in some inner pockets (figures 3(a) and 3(f), although the increases around the urethra (figure 3(f) may have been influenced by free fixative. ADC is influenced by chemical exchange, and is also thought to be affected by viscosity (Purea and Webb, 2006). However in (Purea and Webb, 2006) they surmised that substantial changes in ADC are due to structural changes from protein cross-linking, and in figure 3(a) some areas of decreased ADC corresponded visually with areas of increased E (see (McGrath et al., 2012)). The effect on ADC has also been found to be reversible (Purea and Webb, 2006; Thelwall et al., 2006). The magnitude of ΔDR from 0 to 10% formalin of −3.2 × 10−4 mm2s−1 was not reached in tissue (i.e., the average clinical ΔADC was −1.3(±0.4) ×10−4 mm2s−1).

Implications of findings for pathology correlation

The findings of this study are novel and very important for pathology correlation. The measured increases in Young’s modulus were of a high magnitude (e.g., 17-fold for the central gland), and were highly heterogeneous, with a strong dependency on distance from the tissue edge and the fixation time. Given that errors of 30% in the estimates of material properties led to large registration errors in (Chi et al., 2006), the inclusion of these measured effects of fixation on elastic modulus will be vital for the accuracy of biomechanical-based pathology correlation. (Sahebjavaher et al., 2015) also measured ex vivo prostate biomechanics using a dynamic MRE method, but only carried out measurements post-fixation, and hence did not assess the changes from fresh to fixed tissue. Therefore, the variation of elastic modulus from fresh to fixed tissue, and the fresh state differences in elastic modulus between diseased and healthy tissue and between anatomical zones are very important findings from this study. Furthermore, this work has noted a potential impact of RT on prostate biomechanics (i.e., the much higher E values for the specimen from patient #3 who received a hypo-fractionated RT protocol). Moreover, this work has demonstrated that exposure to fixative reduces the differences in elastic modulus between healthy and diseased tissue and prostate anatomical zones, which reinforces the importance of carrying out measurement both before and after fixation. Indeed, (Sahebjavaher et al., 2015) identified fixation as a confound to their measurement of the biomechanical properties of healthy and diseased prostate. However, in this study RT was a potential confound to the estimation of elastic modulus in the healthy and diseased tissue. Further work with specimens from patients who had not received RT is therefore required to fully explore this issue. Also in future work, population averages will be created from a larger number of data sets of prostate MRE measurements pre- and post-fixation. These average data sets could be used as surrogate measures to inform prostate pathology correlation when MRE is not feasible.

In this study it was also sought to determine if the changes in MRI parameters with fixation could be used to predict changes in E, and therefore if MRI parameters could be used as surrogate measures for E for pathology correlation. As ΔE is influenced by structural changes brought about by cross-linking, one might suspect that ΔR1 and ΔADC would be allied to ΔE. However, the findings of this study suggest that ΔR2 might be more predictive of ΔE than either ΔR1 or ΔADC. For canine specimen #5 the mean ΔE over the tissue volume was strongly correlated with the mean ΔR2 for the different fixation time-points in the timeline study, while there were no correlations between ΔE and either ΔR1 or ΔADC. In the concentric zone analysis of the timeline study with canine specimen #5 some correlations were found between ΔR2 and ΔE, i.e., only for fixation time-points 12 and 30 h, while for ΔR1 only the 120 h time-point correlated with ΔE, and for ΔADC no correlations were found with ΔE. For the concentric zone analysis of clinical prostate, the correlations were again inconsistent: ΔR2 correlated with ΔE for specimens #2 and #3, while ΔR1 also correlated with ΔE for #2 and #3, and ΔADC only correlated with ΔE for specimen #4.

In the canine specimen #5 time-line study, ΔR2 was strongly correlated with the predicted concentration curves, and therefore appears to hold potential as a predictor of local concentration. However, in clinical prostate the ΔR2 and the predicted concentrations did not correlate, and the shape of ΔR2 curves varied widely between specimens. Of course, the D value used to generate the clinical prostate fixative concentration curves was derived from canine prostate, and hence was only a best estimate for clinical prostate. The heterogeneity of the clinical tissue, both between PZ and CG, and diseased and healthy tissue may also account for this inconsistency.

Further studies with larger data sets, including specimens from patients who have not been treated with RT, and a pre-clinical study arm where fixative is washed out before imaging, are required to further examine these findings. Such data would allow a fuller investigation of whether the MR relaxation and diffusion parameters may be used as predictors of fixation-mediated changes in elastic modulus, or if changes in tissue biomechanics can shed light on the dynamics of chemical fixation and its influence on the MRI parameters. If future studies demonstrate ΔR2 as a reliable marker of fixative concentration in clinical prostate, T2 measurement might be developed as a more convenient alternative to MRE for estimating changes in elastic modulus for pathology correlation.

CONCLUSIONS

According to the main hypothesis of this study, it has been demonstrated that clinical prostate elasticity varies widely with anatomy, disease and fixation. Additionally, this initial data suggests sensitivity of prostate biomechanics to RT. Fixation produces large factors of increase in stiffness, in a pattern that is approximately a function of distance from the tissue edge and fixation time. T2 reduces continuously and consistently with fixation, while changes in T1 and ADC are less predictable.

With regard to the secondary hypothesis, it was found that changes in R2 correlated strongly with predicted concentration curves in a pre-clinical specimen, demonstrating that T2 holds potential as a surrogate marker of fixative concentration in tissue. However, changes in R2 did not correlate with predicted concentration curves for the clinical specimens, although this may have been influenced by heterogeneity of tissue properties with anatomy and disease. For certain specimens and time-points changes in R2 correlated with changes in E, however this effect was not consistent. Hence R2 may be predictive of fixation-mediated changes in tissue biomechanics, but further studies are required to confirm this.

Future studies involving larger data sets will lead to generation of population average prostate biomechanical data for pathology correlation, allowing assessment of the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic imaging parameters to disease. This will lead to improved accuracy in image-guided diagnosis and intervention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and in part by an NIH grant # 5R21CA121586-2. K.K.B. was supported as a Cancer Care Ontario Research Chair.

REFERENCES

- Brock K, Ahmed S, Moseley J, Moulton C, Guindi M, Haider M, Gallinger S, Dawson LA. Deformable Registration for In Vivo Imaging and Pathology Correlation. Med Phys. 2006;33:1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brock KK, Sharpe MB, Dawson LA, Kim SM, Jaffray DA. Accuracy of finite element model-based multi-organ deformable image registration. Med Phys. 2005;32:1647–1659. doi: 10.1118/1.1915012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DD, Neu CP, Hull ML. Articular cartilage deformation determined in an intact tibiofemoral joint by displacement-encoded imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2009;61:989–993. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Y, Liang J, Yan D. A material sensitivity study of the accuracy of deformable organ registration using linear biomechanical models. Med Phys. 2006;33:421–433. doi: 10.1118/1.2163838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra R, Arani A, Huang Y, Musquera M, Wachsmuth J, Bronskill M, Plewes D. In vivo MR elastography of the prostate gland using a transurethral actuator. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2009;62:665–671. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correas JM, Tissier AM, Khairoune A, Khoury G, Eiss D, Helenon O. Ultrasound elastography of the prostate: state of the art. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2013;94:551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson LA, Brock KK, Moulton C, Moseley J, Ahmed S, Guindi M, Gallinger S, Haider M. Comparison of liver metastases volumes on CT, MR and FDG PET imaging to pathological resection using deformable registration. Int J Radiation Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:S68. [Google Scholar]

- Dresner MA, Cheville JC, Myers RP, Ehman RL. MR Elastography of Prostate Cancer. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med. 2003;11:578. [Google Scholar]

- Dresner MA, PJ R, Kruse SA, Ehman RL. MR Elastography of the Prostate. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med. 1999;7:526. [Google Scholar]

- Foltz WD, Chopra S, Chung P, Bayley A, Catton C, Jaffray D, Wright GA, Haider MA, Menard C. Clinical prostate T2 quantification using magnetization-prepared spiral imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2010a;64:1155–1161. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltz WD, Haider MA, Chung P, Bayley A, Catton C, Ramanan V, Jaffray D, Wright GA, Menard C. Prostate T1 quantification using a magnetization-prepared spiral technique. Magn Reson Med. 2011;33:474–481. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltz WD, Wu A, Kirilova A, Chung P, Bayley A, Catton C, Jaffray D, Haider MA, Menard C. Early quantitative T1 and T2 response of the prostate gland during radiotherapy. Proc Intl Soc Mag Res Med. 2010b;18:2815. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs P, Tozer DJ, Liney GP, Turnbull LW. Comparison of quantitative T2 mapping and diffusion-weighted imaging in the normal and pathologic prostate. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:1054–1058. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider MA, Chung P, Sweet J, Toi A, Jhaveri K, Menard C, Warde P, Trachtenberg J, Lockwood G, Milosevic M. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for localization of recurrent prostate cancer after external beam radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiation Oncology Biol. Phys. 2008;70:425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider MA, van der Kwast TH, Tanguay J, Evans AJ, Hashmi A, Lockwood G, Trachtenberg J. Combined T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted MRI for localization of prostate cancer. Am. J. Roent. 2007;189:323–328. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iczkowski KA. Effect of radiotherapy on non-neoplastic and malignant prostate. The Open Pathology Journal. 2009;3:64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kemper J, Sinkus R, Lorenzen J, Nolte-Ernsting C, Stork A, Adam G. MR elastography of the prostate: Initial in-vivo application. Rofo. Fortschritte auf dem Gebiet der Rontgenstrahlen und der bildgebenden Verfahren. 2004;176:1094–1099. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouskop TA, Wheeler TM, Kallel F, Garra BS, Hall T. Elastic moduli of breast and prostate tissues under compression. Ultrason. Imaging. 1998;20:260–274. doi: 10.1177/016173469802000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer DL, van der Kwast TH, Evans AJ, Trachtenberg J, Wilson BC, Haider MA. Prostate cancer detection with multi-parametric MRI: logistic regression analysis of quantitative T2, diffusion-weighted imaging, and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30:327–334. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Y, Li C, Feng K, Duncan R, Eisma R, Huang Z, Nabi G. Effects of fixation and preservation on tissue elastic properties measured by quantitative optical coherence elastography (OCE) Journal of biomechanics. 2016;49:1009–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariappan YK, Glaser KJ, Ehman RL. Magnetic resonance elastography: a review. Clin Anat. 2010;23:497–511. doi: 10.1002/ca.21006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAnearney S, Federov A, Joldes G, Hata N, Tempany C, Miller K, Wittek A. The effects of Young's modulus on predicting prostate deformation in MRI-guided interventions. Int Conf Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2010;13 [Google Scholar]

- McGrath DM, Foltz WD, Al-Mayah A, Niu CJ, Brock KK. Quasi-static magnetic resonance elastography at 7 T to measure the effect of pathology before and after fixation on tissue biomechanical properties. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68:152–165. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath DM, Foltz WD, Samavati N, Lee J, Jewett MA, van der Kwast TH, Menard C, Brock KK. Biomechanical property quantification of prostate cancer by quasi-static MR elastography at 7 tesla of radical prostatectomy, and correlation with whole mount histology. Proc Intl Soc Mag Res Med. 2011;19:1483. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath DM, Lee J, Foltz WD, Samavati N, Jewett MAS, van der Kwast T, Chung P, Ménard C, Brock KK. Technical Note: Method to correlate whole-specimen histopathology of radical prostatectomy with diagnostic MR imaging. Med. Phys. 2016;43:1065–1072. doi: 10.1118/1.4941016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNiven A, Moseley J, Langer DL, Haider MA, Brock KK. Preliminary feasibility study modeling 3D deformations of the prostate from whole-mount histology to in vivo MRI. Med Phys. 2009;36:2712. [Google Scholar]

- Menard C, Susil RC, Choyke P, Gustafson GS, Kammerer W, Ning H, Millner RW, Ullman KL, Crouse NS, Smith S, Lessard E, Pouliot J, Wright V, McVeigh E, Coleman CN, Camphausen KC. MRI-guided HDR prostate brachytherapy in standard 1.5T scanner. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004;59:1414–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthupuillai R, Lomas DJ, Rossman PJ, Greenleaf JF, Manduca A, Ehman RL. Magnetic resonance elastography by direct visualization of propagating acoustic strain waves. Science. 1995;269:1854–1857. doi: 10.1126/science.7569924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmeri ML, Glass TJ, Miller ZA, Rosenzweig SJ, Buck A, Polascik TJ, Gupta RT, Brown AF, Madden J, Nightingale KR. Identifying Clinically Significant Prostate Cancers using 3-D In Vivo Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Imaging with Whole-Mount Histology Validation. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2016;42:1251–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmeri ML, Miller ZA, Glass TJ, Garcia-Reyes K, Gupta RT, Rosenzweig SJ, Kauffman C, Polascik TJ, Buck A, Kulbacki E, Madden J, Lipman SL, Rouze NC, Nightingale KR. B-mode and acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) imaging of prostate zonal anatomy: comparison with 3T T2-weighted MR imaging. Ultrasonic imaging. 2015;37:22–41. doi: 10.1177/0161734614542177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker KJ, Huang SR, Lerner RM, Lee F, Rubens D, Roach D. Elastic and ultrasonic properties of the prostate; Proc. IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium; 1993. pp. 1035–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Purea A, Webb A. Reversible and irreversible effects of chemical fixation on the NMR propertiers of single cells. Magn Res Med. 2006;56:927–931. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahebjavaher RS, Baghani A, Honarvar M, Sinkus R, Salcudean SE. Transperineal prostate MR elastography: initial in vivo results. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:411–420. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahebjavaher RS, Frew S, Bylinskii A, ter Beek L, Garteiser P, Honarvar M, Sinkus R, Salcudean S. Prostate MR elastography with transperineal electromagnetic actuation and a fast fractionally encoded steady-state gradient echo sequence. NMR in biomedicine. 2014;27:784–794. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahebjavaher RS, Nir G, Gagnon LO, Ischia J, Jones EC, Chang SD, Yung A, Honarvar M, Fazli L, Goldenberg SL, Rohling R, Sinkus R, Kozlowski P, Salcudean SE. MR elastography and diffusion-weighted imaging of ex vivo prostate cancer: quantitative comparison to histopathology. NMR in biomedicine. 2015;28:89–100. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samavati N, McGrath DM, Jewett MA, van der Kwast T, Menard C, Brock KK. Effect of material property heterogeneity on biomechanical modeling of prostate under deformation. Phys Med Biol. 2015;60:195–209. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/1/195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samavati N, McGrath DM, Lee J, van Kwast T, Jewett M, Menard C, Brock KK. Biomechanical model-based deformable registration of MRI and histopathology for clinical prostatectomy. Journal of pathology informatics. 2011;2:S10. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.92035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheenen TW, Orzada S, Kobus T, Lagemaat MW, Maas MC, Kraff O, Maderwald S, Brote I, Ladd ME, Bitz AK. MRI of the human prostate in vivo at 7T. Proc Intl Soc Mag Res Med. 2011;19:592. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd T, Thelwall P, Stanisz G, Blackband S. Aldehyde fixative solutions alter the water relaxation and diffusion properties of nervous tissue. Magn Res Med. 2009;62:26–34. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkus R, Nisius T, Lorenzen J, Kemper J, Dargatz M. In vivo prostate MR-Elastography. Proc Intl Soc Mag Res Med. 2003:586. [Google Scholar]

- Thelwall PE, Shepherd TM, Stanisz GJ, Blackband SJ. Effects of temperature and aldehyde fixation on tissue water diffusion properties, studied in an erythrocyte ghost tissue model. Magn Res Med. 2006;56:282–289. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thickman DI, Kundel HL, Wolf G. Nuclear magnetic resonance characteristics of fresh and fixed tissue: the effect of elapsed time. Radiology. 1983;148:183–185. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.1.6856832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong-Hing C, Obenaus A, Stryker R, Tong K, Sarty G. Magnetic resonance imaging and mathematical modeling of progressive formalin fixation of the human brain. Magn Res Med. 2005;54:324–332. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Nigwekar P, Castaneda B, Hoyt K, Joesph JV, Di Sant'Agnese A, Messing EM, Strang JG, Rubens D, Parker KJ. Quantitative characterization of viscoelastica properties of human prostate correlated with histology. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]