Abstract

Problem

Structural competency is a framework for conceptualizing and addressing health-related social justice issues that emphasizes diagnostic recognition of economic and political conditions producing and racializing inequalities in health. Strategies are needed to teach prehealth undergraduate students concepts central to structural competency (e.g., structural inequity, structural racism, structural stigma) and to evaluate their impact.

Approach

The curriculum for Vanderbilt University’s innovative prehealth major in medicine, health, and society (MHS) was reshaped in 2013 to incorporate structural competency concepts and skills into undergraduate courses. The authors developed the Structural Foundations of Health (SFH) evaluation instrument, with closed- and open-ended questions designed to assess undergraduate students’ core structural competency skills. They piloted the SFH instrument in 2015 with MHS seniors.

Outcomes

Of the 85 students included in the analysis, most selected one or more structural factors as among the three most important in explaining U.S. regional childhood obesity rates (85%) and racial disparities in heart disease (92%). More than half described individual- or family-level structural factors (66%) or broad social and political factors (56%) as influencing geographic disparities in childhood obesity. Nearly two-thirds (66%) described racial disparities in heart disease as consequences of socioeconomic differences, discrimination/stereotypes, or policies with racial implications.

Next Steps

Preliminary data suggest that the MHS major trained students to identify and analyze relationships between structural factors and health outcomes. Future research will include a comparison of structural competency skills among MHS students and students in the traditional premedical track and assessment of these skills in incoming first-year students.

Problem

Structural competency has emerged as a framework for conceptualizing and addressing health-related social justice issues.1,2 Structural competency builds on cultural competency, a heuristic approach that imparts to medicine the idea that matters of race, social class, ability, sexual orientation, and other markers of difference shape interactions between doctors and patients. Whereas cultural competency focuses mainly on identifying clinician bias and improving physician–patient communication, structural competency emphasizes diagnostic recognition of the economic and political conditions that produce and racialize inequalities in health in the first place. Structural competency calls on health care providers to recognize how institutions, markets, or health care delivery systems shape presentations of symptoms, and to mobilize medical expertise and authority for the betterment of clinical and extraclinical systems that lead to health and wealth imbalances.

To date, most structural competency interventions have targeted medical students or health care providers.3,4 Yet, strategies are needed to teach undergraduate prehealth (e.g., premedical, prenursing, and presocial work) students the concepts central to structural competency—such as structural inequity, structural racism, and structural stigma—and to evaluate their impact on health and illness. Prehealth undergraduates learn about the organic aspects of illness as a matter of course, but they traditionally receive less didactic training on the social structures that produce inequities in the distribution of illnesses or the structural barriers and stigmatizations that accompany certain diagnoses. Instruction in these latter issues is becoming increasingly important as developments in epigenetics and neuroscience uncover the vital roles that social contexts may play in even the most seemingly biological of illnesses, and as educational and testing bodies—including the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the Medical College Admission Test5,6—emphasize recognition of the underlying “social foundations” of health.

Here, we describe a new curriculum at Vanderbilt University that imparts and then assesses structural competency in a prehealth undergraduate setting.

Approach

In 2005, Vanderbilt University established a new prehealth major in medicine, health, and society (MHS) that combined course work in health sciences, humanities, and social sciences. The MHS major emphasized interdisciplinary study of health and illness in ways that encouraged students to think critically about complex social issues that have an impact on health, health care, and health policy. Enrollment rose from 40 students in the first year, to 160 students in 2009, to more than 300 students in 2012. By 2013, MHS had become the fastest-growing and third-largest major among the university’s roughly 7,000 undergraduates. In 2015, the major passed 500 students.

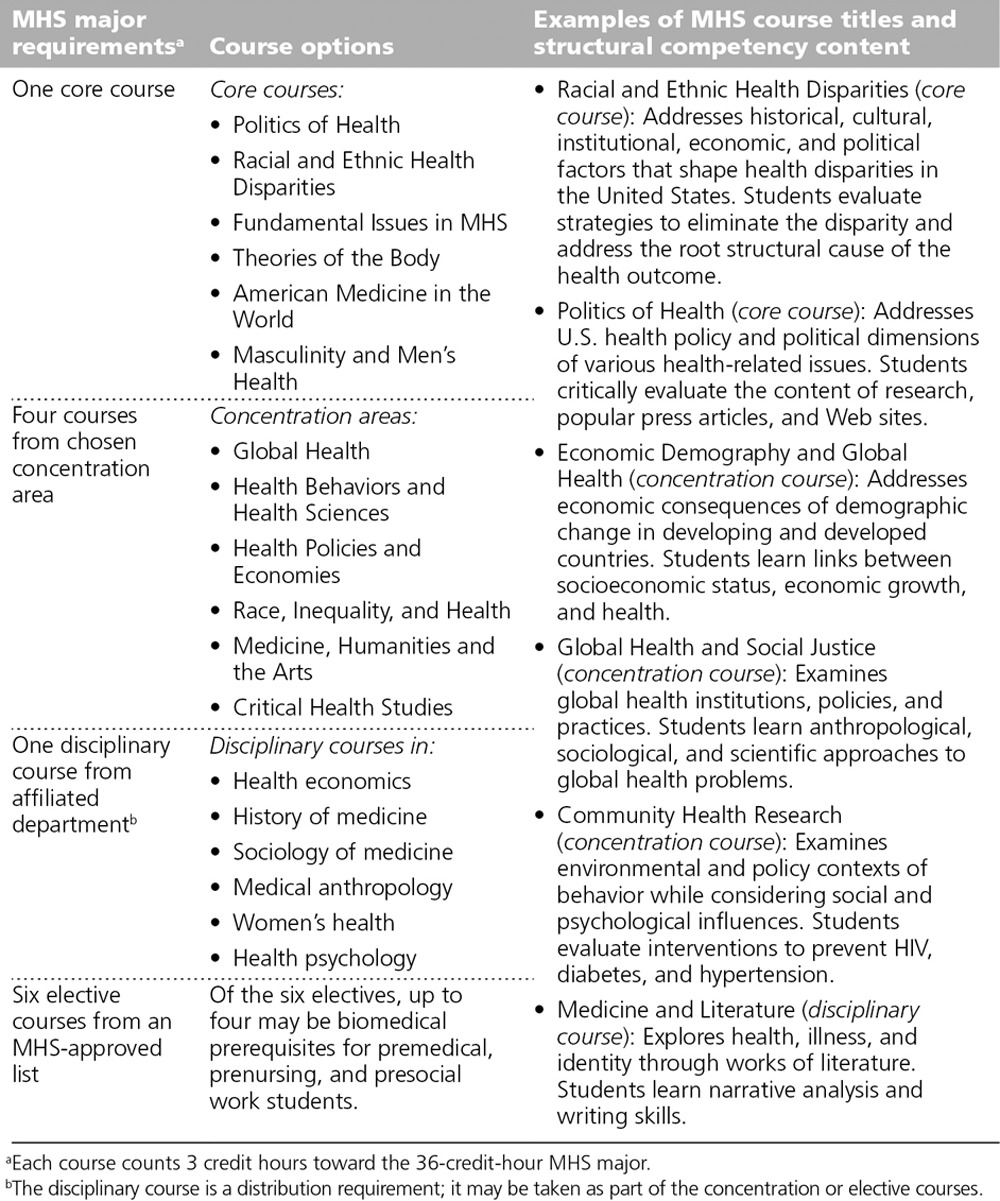

Faced with growing student demand, MHS faculty met over the course of academic year 2012–2013 to shape the MHS curriculum to emphasize respect for clinical advances alongside critical attention to the social, cross-cultural, racialized, and gendered determinants of health deemed increasingly important in medical education. The revised 36-credit-hour MHS major that emerged in fall 2013 introduced a host of new interdisciplinary core courses, including offerings on racial and ethnic health disparities, structural aspects of mental health, economic determinants of health, politics of health, health activism, disability studies, and critical perspectives on global health. The revised major further allowed students to personalize their educations by choosing one of six concentration areas. As Chart 1 details, the major’s curriculum minimally required students to take at least one of six core MHS courses, four courses in their concentration area, and one disciplinary course offered by an affiliated department. Prehealth students generally combined the MHS curriculum with science prerequisites.

Chart 1.

Curriculum Overview for the Medicine, Health, and Society (MHS) Major, Vanderbilt University, 2015

Structural competency emerged as a central unifying rubric in this curricular reformulation. MHS faculty workshopped and developed a number of structural-competency-based interventions, including the following:

The Designing Healthy Publics course studied how buildings, cities, and urban planning structure the health of populations.

The Community Health Research course analyzed how health disparities are created and maintained by structural policies and practices.

Courses on race, ethnicity, and health explored ways that historical, cultural, institutional, economic, and political factors shaped morbidity patterns, food distribution networks, medication reimbursement rates, and injury patterns.

Structural immersion assignments added to medical humanities courses explored tensions between individual and social welfare in literary texts.

Social Foundations of Health evaluation instrument

Through an analysis of course syllabi and in dialogue with existing frameworks (e.g., the AAMC’s Core Competencies for Entering Medical Students5), MHS faculty identified central curricular concepts and skills related to structural competency (List 1). These undergirded the development of the Structural Foundations of Health (SFH) evaluation instrument, to test students’ core structural competency skills and gather student self-assessment and demographic information. As part of instrument development, a small, randomly selected group of MHS students completed the instrument to assess any unclear questions, and we edited according to their feedback. Average completion time was 30 minutes.

The SFH instrument was piloted with graduating MHS majors in 2015. The Vanderbilt University institutional review board granted exempt status for this study. (A copy of the SFH instrument is available from the corresponding author upon request.)

List 1. Proposed Core Structural Competencies in an Undergraduate Prehealth Curriculuma.

Link health outcomes to structural factors at the individual or family level (income, educational level, health insurance status, and access to health care) and to broad social, political, and economic factors (neighborhood factors, racism, health delivery system, and health policy).

Link cultural differences to structural contexts including social determinants of health (e.g., socioeconomic status, neighbor factors, cost of health care), health systems, and institutional racism.

Demonstrate knowledge of the mechanisms through which structural factors shape health outcomes.

Demonstrate understanding of the relationship between race and health as an outcome of cultural and social factors.

aThese competencies were crafted by Medicine, Health, and Society (MHS) faculty as part of the MHS major’s curriculum revision in 2012–2013. Sources included Metzl and Hansen’s structural competency framework,1 the human behavior competency in the Association of American Medical Colleges’ Core Competencies for Entering Medical Students,5 Metzl and Roberts’s article “Structural Competency Meets Structural Racism,”2 and a review of the MHS syllabus.

Data analysis

The SFH instrument included closed- and open-ended questions. To ensure rigor, the authors independently read all responses and then met to create codes for each open-ended question. Responses were then independently coded by a trained PhD student and confirmed among the authors. Agreement was 0.93.

Outcomes

The SFH instrument was piloted with 127 graduating MHS seniors, who completed it online as part of their required graduation exam in April 2015. Of these 127 MHS students, 107 consented to their responses being used for research, and 85 cases remained after excluding incomplete questionnaires. Key SFH items and results of the pilot are reported below.

Student demographics and professional preparedness

The 2015 MHS cohort demonstrated diversity in race/ethnicity and career interests. Eighteen percent (19/107) of the students identified as African American, double the percentage of the broader Vanderbilt student population. Another 12% (13/107) identified as Asian/Pacific Islander, 7% (7/107) as Hispanic, and 3% (3/107) as multiracial. Roughly 40% (41/107 [38%]) identified as premedical students, and the remainder reported planned careers in such fields as nursing, social work, public health, health care administration, humanities, and consulting.

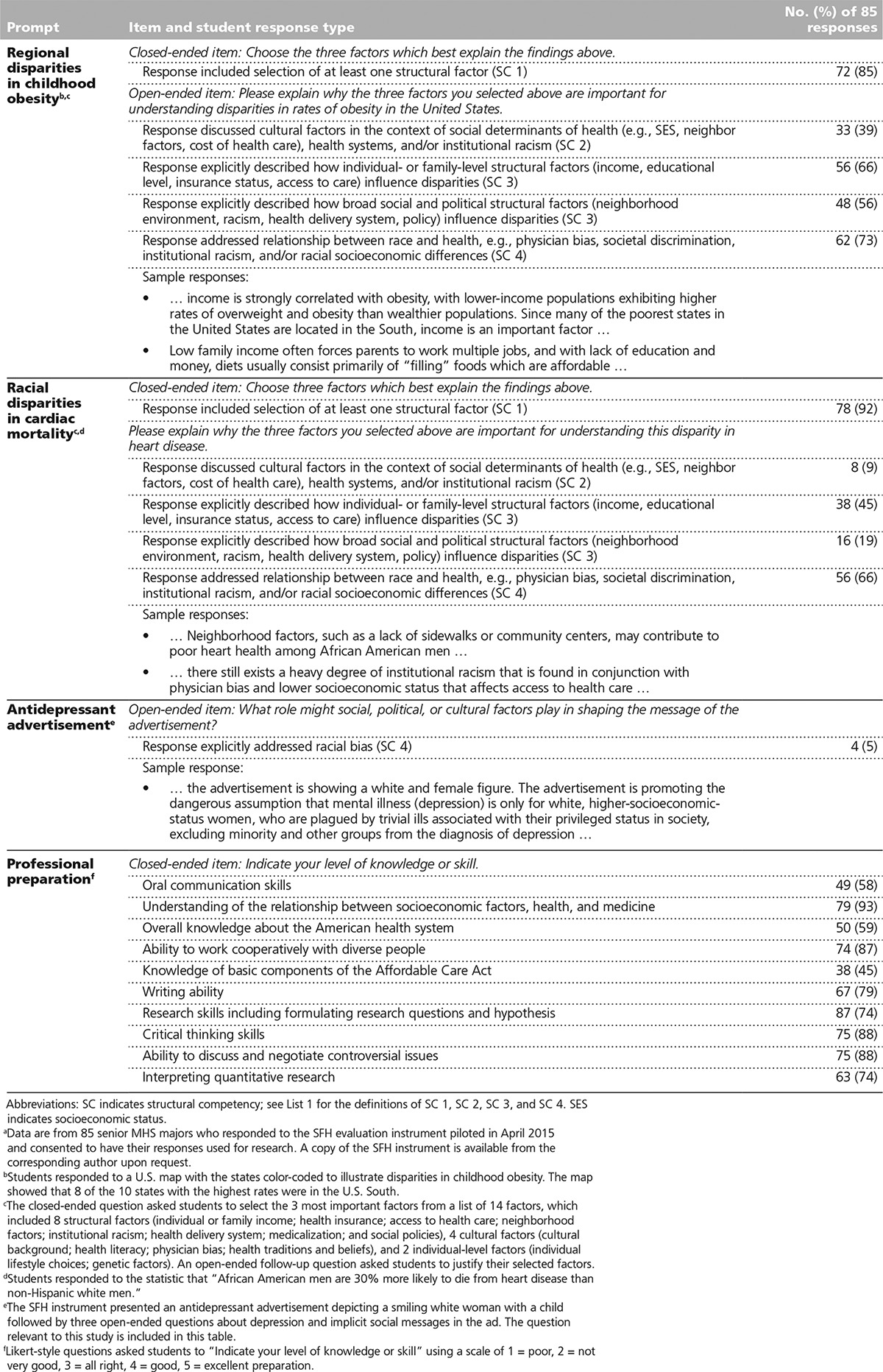

Results of the pilot suggest that the MHS prehealth curriculum emphasizing the social foundations of health prepared the students for their planned postgraduation careers. Most students reported “good” or “excellent” professional preparation when asked about professional competencies identified by the AAMC as important for entering medical students, and they also demonstrated cultural and structural competencies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Response Patterns Related to Structural Competency and Professional Preparedness Among 85 Medicine, Science, and Health (MSH) Majors, Social Foundations of Health (SFH) Evaluation Instrument Pilot, Vanderbilt University, April 2015a

Of note, students’ self-reports of professional preparation seemed to be supported by acceptance rates to professional schools. For instance, MHS applicants to medical school were accepted at rates comparable to those of traditional premedical students in 2014. According to data from the Health Professions Advisory Office, the 2014 medical school acceptance rates for applicants from the three most popular premedical majors at Vanderbilt were 61% for neuroscience, 65% for molecular and cellular biology, and 62% for MHS, compared with a national average of 43%.7

Structural competency

Structural competency was assessed through open-ended questions about social and structural determinants of health. This format allowed us to examine students’ narrative understanding of how and why social and cultural stressors affect health outcomes. For instance, students responded to an open-ended question—“In your opinion, what are the three most important influences on people’s health?”—modeled on research reported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) in “A New Way to Talk About the Social Determinants of Health.”8 According to the RWJF’s research, only a small fraction of respondents addressed social determinants when asked about the influences of health, but many recognized social determinants of health as important when prompted with examples. Therefore, in the SFH instrument, this question preceded case-based questions about health disparities. In their responses to this question, roughly half of the MHS students identified socioeconomic status (36/85 [42%]) and environmental or societal factors (41/85 [59%]).

We then asked students to analyze health disparities in childhood obesity and heart disease. For childhood obesity, we included a color-coded map of the United States from a 2009 Trust for America’s Health report9 showing that 8 of the 10 states with the highest rates of childhood obesity were in the South. For heart disease, we provided a statistic that “African American men are 30% more likely to die from heart disease than non-Hispanic white men.”10 For each of these health disparities, students were asked to select the 3 most important factors from a list of 14 factors, which included 2 individual-level factors (genetic factors; individual lifestyle choices), 4 cultural factors (cultural background; health traditions and beliefs; health literacy; physician bias), and 8 structural factors as defined by Metzl and Hansen1 (access to health care; health delivery system; health insurance; institutional racism; medicalization; individual or family income; neighborhood factors; social policies). Students were then asked to explain why they selected these three factors. They typically wrote four to five sentences explaining their answers.

As Table 1 details, MHS students frequently selected one or more structural factors (72/85 [85%]) as one of the three most important factors explaining childhood obesity rates in the U.S. South. Most MHS students selected one or more structural factors (78/85 [92%]) as among the three most important factors explaining disparities in heart disease.

We coded students’ open-ended responses to these health disparities prompts for discussion of cultural factors in the context of structural influences, how structural context influences health outcomes, and how race impacts health outcomes through bias, discrimination, institutional racism, and/or socioeconomic status (see List 1 and Table 1). For instance, 66% (56/85) of students explicitly described mechanisms through which individual- or family-level structural factors influence geographic disparities in childhood obesity, and 56% (48/85) addressed broad social and political structural factors. Students’ open-ended explanations of disparities in heart disease also suggested a depth of analysis regarding race: 66% of students (56/85) defined racial disparities as consequences of socioeconomic differences, discrimination, or stereotypes, or of policies that had racial consequences or implications.

To assess students’ recognition that structural factors shape the health of mainstream as well as minority populations, the SFH instrument further asked students to interpret an antidepressant advertisement depicting a smiling white woman playing with a child. Responses to this item revealed relatively low levels of critical engagement with race and socioeconomic status, however: Only 5% (4/85) of students addressed the woman’s race/whiteness, and 1% (1/85) addressed her class. The level of engagement with gender was higher, with 23% (20/85) of students addressing the gendered portrayal of depression in their responses.

Next Steps

Our preliminary data suggest that the interdisciplinary MHS major trained students to identify and analyze relationships between structural factors and health outcomes. In their responses to the pilot of the SFH instrument, MHS students appeared attuned to the social determinants and cultural foundations of health. They often demonstrated high levels of awareness of the impact of cultural and structural factors on health outcomes. MHS students also demonstrated high levels of structural competency in their approaches to race, intersectionality, and racial health disparities. For instance, MHS students frequently listed structural or institutional racism as an explanatory factor for racial, economic, and demographic disparities, and they commonly defined these disparities as arising from socioeconomic differences, discrimination, or policies that had intended or unintended racial consequences. However, they struggled to address race when the subject appeared to be white—a discrepancy that we plan to address in future work.

It may well be argued that the MHS students simply reproduced the very structural language and methods for which they were rewarded in their course work—but that is, in part, the point. The skills that these students demonstrated represented skills that are getting more emphasis in requirements, standards, and standardized examinations as educators and researchers increasingly recognize the ways in which contextual factors can shape seemingly racial, biological, or otherwise fixed expressions of health and illness.

Of note, a majority of Vanderbilt undergraduate students continue to pursue traditional prehealth degrees as pathways to professional schools through interdisciplinary science majors such as neuroscience, molecular and cell biology, biomedical engineering, or other courses of study that emphasize life sciences along with smaller numbers of required humanities and social science classes.

This divergence of two prehealth tracks at the same school—one emphasizing the traditional sciences (e.g., premedical), another promoting cultural and cross-cultural analysis alongside science prerequisites (MHS)—provides the foundation for the next planned phase of our analysis: a comparison of skills related to the social foundations of health among students in these two distinct tracks. Also, because Vanderbilt students do not declare their major before the end of their second year, in this pilot we were only able to evaluate students nearing completion of their baccalaureate degrees. We plan to conduct a subsequent study to assess structural skills in incoming first-year students.

Overall, we aim to contribute to an evolving literature that suggests that teaching students about the social and structural aspects of race and medicine needs to begin sooner in the educational process, during the undergraduate years, when students can learn about structures and socioeconomic and historical contexts at the same time as they begin to learn about diseases and bodies. Through the structural competency framework, we further aim to demonstrate that imparting “cultural” expertise depends not just on challenging students’ implicit biases but also on imparting real-world methodologies and proficiencies.

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank Derek Griffith, Janelle Cassidy, Rachel Turner, Oluwatunmise V. Olowojoba, Sheena Adams-Avery, and John Carson for their assistance in the preparation of this report.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: This research was partially supported with funding from the REAM Foundation, http://reamfoundation.org.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: The Vanderbilt University IRB granted exempt status for this study (IRB# 150422) on March 23, 2015.

Previous presentation: Preliminary data were presented at the 2015 Gender, Health, and the South Symposium; Anna Julia Cooper Center at Wake Forest University; April 16–17, 2015.

References

- 1.Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126–133.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Structural competency meets structural racism: Race, politics, and the structure of medical knowledge. Am Med Assoc J Ethics. 2014;16(9):674–690.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.School of Public Health at University at Albany, State University of New York. Advancing cultural competence in the public health and health care workforce. http://www.albany.edu/sph/cphce/advancing_cc.shtml. Accessed September 9, 2016.

- 4.A new way to fight health disparities? Colorlines. 2014July5 http://www.colorlines.com/articles/new-way-fight-health-disparities. Accessed September 9, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association of American Medical Colleges. Core Competencies for Entering Medical Students. https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/admissionsinitiative/competencies/. Accessed September 9, 2016.

- 6.Redesigning the MCAT exam: Balancing multiple perspectives. Acad Med. 2013;88:560–567.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vanderbilt University Health Professions Advisory Office: 2014 annual report. http://as.vanderbilt.edu/hpao/documents/2014_Annual_Report.pdf. Accessed September 9, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.A new way to talk about the social determinants of health. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2010/01/a-new-way-to-talk-about-the-social-determinants-of-health.html. Published January 1, 2010. Accessed September 9, 2016.

- 9.Trust of America’s Health, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. F as in fat 2009: How obesity policies are failing in America. http://healthyamericans.org/reports/obesity2009. Published July 2009. Accessed September 9, 2016.

- 10.Health disparities in boys and men. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 2):S167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]