Abstract

How and when to disclose a positive HIV diagnosis to an infected child is a complex challenge for caregivers and healthcare workers. With the introduction of antiretroviral therapy, pediatric HIV infection has transitioned from a fatal disease to a lifelong chronic illness, thus increasing the need to address the disclosure process. As HIV-infected children mature, begin to take part in management of their own health care, and potentially initiate HIV-risk behaviors, understanding the nature of their infection becomes essential. Guidelines recommend developmentally-appropriate incremental disclosure, and emphasize full disclosure to school-age children. However, studies from sub-Saharan Africa report that disclosure to HIV-infected children is often delayed. Between 2013-2014, 553 perinatally HIV-infected children aged 4-9 years were enrolled into a cohort study in Johannesburg, South Africa. We assessed the extent of disclosure among these children and evaluated characteristics associated with disclosure. No children 4 years of age had been told their status, while 4% of those aged 5 years, and 8%, 13%, 16%, and 15% of those aged 6, 7, 8, and 9 years, respectively, had been told their status. Age was the strongest predictor of full disclosure (odds ratio 1.6 per year, p=0.001). An adult living in the household who was unaware of the child's status was associated with a reduced probability of disclosure, and knowing that someone at the child's school was aware of child's status was associated with an increased probability of disclosure. Among caregivers that had not disclosed, 42% reported ever discussing illness in general with the child, and 17% reported on-going conversations about illness or HIV. In conclusion, a small minority of school age children had received full disclosure. Caregivers and healthcare workers require additional support to address disclosure. A broader public health strategy integrating the disclosure process into pediatric HIV treatment programs is recommended.

Keywords: HIV, disclosure, children, South Africa

Introduction

Approximately 1.8 million children under 15 years of age are living with HIV worldwide, including 1.5 million in sub-Saharan Africa. Despite significant progress in prevention of mother-to-child transmission, about 150,000 children acquired HIV in 2015 (UNAIDS, 2016). With the introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART), pediatric HIV infection has transitioned from a fatal disease to a lifelong chronic illness, requiring special management as children develop into adolescence and adulthood.

How and when to disclose a positive HIV diagnosis to an infected child is a complex challenge for caregivers. Guidelines recommend disclosure to school-age children and emphasize the importance of age-appropriate disclosure according to the child's emotional and cognitive development (American Academy of Pediatrics: Committee on Pediatric AIDS, 1999; National Department of Health South Africa, 2015; World Health Organization, 2011). Disclosure is described as an incremental process, beginning with “partial” disclosure in younger children (i.e., telling the child some information about the illness that is consistent with HIV but without naming HIV), and leading up to “full” disclosure when the child is informed of his or her HIV diagnosis. Full disclosure should be followed with on-going education and support, including informing the child about how the infection was acquired, the nature of HIV, and the role of ART (American Academy of Pediatrics: Committee on Pediatric AIDS, 1999; Atwiine, Kiwanuka, Musinguzi, Atwine, & Haberer, 2015; Funck-Brentano et al., 1997; National Department of Health South Africa, 2015; World Health Organization, 2011). Full disclosure is strongly recommended prior to adolescence, when children transition to managing their own health care and may initiate HIV risk behaviors (American Academy of Pediatrics: Committee on Pediatric AIDS, 1999; National Department of Health South Africa, 2015; World Health Organization, 2011).

Despite broad agreement on the importance of disclosure, interventions that support caregivers and healthcare providers in the disclosure process are limited, and many feel unprepared (Kiwanuka, Mulogo, & Haberer, 2014). Studies from sub-Saharan Africa report about 10% prevalence of full disclosure among HIV-infected school-going children up to 10 years of age (Abebe & Teferra, 2012; Atwiine et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2011; John-Stewart et al., 2013; Kallem, Renner, Ghebremichael, & Paintsil, 2011; Tadesse, Foster, & Berhan, 2015; Vreeman et al., 2014). Understanding factors associated with full disclosure may inform the development of strategies that support disclosure to HIV-infected children.

We assessed the prevalence of full disclosure in a cohort of HIV-infected children in South Africa and aimed to identify socio-demographic and clinical factors associated with full disclosure. To better understand the process of reaching full disclosure, we also investigated whether conversations about illness and HIV between caregivers and their children had occurred.

Methods

Study sample

Between February 2013 and May 2014, 553 perinatally HIV-infected children aged 4-9 years were enrolled into a prospective cohort study. Children were recruited at two sites in Johannesburg, South Africa: Empilweni Services and Research Unit (ESRU) at Rahima Moosa Mother and Child Hospital, and the Perinatal HIV Research Unit (PHRU) at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto. All children had previously participated in clinical trials at these sites (Coovadia et al., 2010; Coovadia et al., 2015; Cotton et al., 2013; Kuhn et al., 2012; Violari et al., 2008) and the majority initiated ART before 2 years of age. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of children and their caregivers were collected at enrollment. Additionally, in a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire, caregivers were asked about discussions with the child regarding illness and HIV, including whether the child had been told his/her HIV status. Here we report a cross-sectional study of disclosure at the time of enrollment.

Definitions of disclosure

Children were classified as having received full disclosure if their caregiver answered “yes” to the question “Has your child been told his/her HIV status?”. “Partial” disclosure was assessed in four yes/no questions: (1) “Have you ever talked in general about illness with your child (not mention HIV directly)?”; (2) “Have you ever talked with your child about HIV (naming it)?”; (3) “Do you have on-going conversations with your child about illness or HIV?”; and (4) “Does the child ask questions about HIV?”. For children who had not been told their status, mention of HIV in questions 2 and 3 is presumably not about the child's infection. A “yes” response to any of these questions could reflect partial disclosure, or, could reflect misinformation provided to the child. Discussions between caregivers and children were further characterized with an open-ended question: “What have you told your child regarding why he/she is taking medications or going to the doctor frequently?”. Answers to this question were categorized manually by one investigator (PMM) and category assignment was reviewed by two investigators (SLS and RS). The following categories were assigned: 1) not discussed; 2) especially vague with some misinformation; 3) especially vague with some truth; 4) vague and true; 5) moderately specific and true; 6) specific misinformation; 7) specific and true (consistent with full disclosure).

Statistical analyses

We described characteristics of children and caregivers and tested for differences between study sites with the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. To evaluate factors associated with disclosure, we first estimated unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) using simple logistic regression. Characteristics marginally associated with disclosure (p-value <0.10) were included in a multivariable model to estimate adjusted ORs. We further assessed the association of each characteristic with disclosure within age groups, then tested for interaction when potential differences in effect were observed. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC).

Results

Study population

Among 553 HIV-infected children enrolled in the cohort study, 550 enrolled with a caregiver who completed the disclosure questionnaire, including 281 at ESRU and 269 at PHRU. Across sites, 54% of the children were female. Those enrolled at ESRU were younger, with a median age of 5.9 years compared to 7.2 at PHRU (p<0.0001). All children had initiated ART previously; 29 at PHRU were not on ART at the time of enrollment due to prior participation in a treatment interruption trial (Cotton et al., 2013). The median age at ART initiation was 2.3 months at PHRU and 6.9 months at ESRU (p<0.0001). For the majority of children (89% across sites), the primary caregiver was the biological mother. In a quarter of all households an adult did not know the child's HIV status, and 19% of caregivers reported that someone at the child's school or crèche was aware of the child's status (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of study participants, stratified by site.

| By site | All children (N=550) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| ESRU (N=281) | PHRU (N=269) | p-value | ||

| Child characteristics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Sex, n(%) | ||||

| Male | 140 (49.8) | 113 (42.0) | 0.07 | 253 (46.0) |

| Female | 141 (50.2) | 156 (58.0) | 297 (54.0) | |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 5.9 (5.0, 7.7) | 7.2 (6.7, 7.8) | <0.0001 | 6.9 (5.6, 7.8) |

| Age at ART initiation in months, median (IQR) | 6.9 (3.9, 13.1) | 2.3 (1.7, 5.4) | <0.0001 | 4.7 (2.0, 9.4) |

| Currently on ART*, n(%) | 281 (100.0) | 240 (89.2) | <0.0001 | 521 (94.7) |

| HIV RNA <400 copies/mL**, n(%) | 271 (96.8) | 227 (94.6) | 0.21 | 498 (95.8) |

| CD4 count, median (IQR) | 1237 (933, 1525) | 965 (720, 1292) | <0.0001 | 1096 (810, 1438) |

| CD4 percent, median (IQR) | 36.6 (32.2, 40.5) | 33.2 (28.4, 37.0) | <0.0001 | 34.4 (30.1, 39.3) |

| Ever hospitalized, n(%) | ||||

| Yes | 200 (71.4) | 117 (43.5) | <0.0001 | 317 (57.7) |

| No | 80 (28.6) | 152 (56.5) | 232 (42.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Caregiver characteristics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Relationship to child, n(%) | ||||

| Mother | 254 (90.4) | 235 (87.4) | 0.26 | 489 (88.9) |

| Other | 27 (9.6) | 34 (12.6) | 61 (11.1) | |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 35.0 (31.0, 39.0) | 36.0 (32.0, 40.0) | 0.16 | 35.0 (32.0, 40.0) |

| Marital status, n(%) | ||||

| Single | 191 (68.0) | 199 (74.0) | 0.16 | 390 (70.9) |

| Married | 77 (27.4) | 55 (20.4) | 132 (24.0) | |

| Divorced/widowed/other | 13 (4.6) | 15 (5.6) | 28 (5.1) | |

| Graduated from high school, n(%) | 134 (47.7) | 116 (43.1) | 0.28 | 250 (45.5) |

| Has paid job, n(%) | 148 (52.7) | 128 (47.8) | 0.25 | 276 (50.3) |

| Currently on ART, n(%) | 206 (73.3) | 190 (70.6) | 0.48 | 396 (72.0) |

|

| ||||

| Family and social characteristics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Biological mother died, n(%) | 9 (3.2) | 19 (7.1) | 0.04 | 28 (5.1) |

| Father died, n(%) | 29 (10.6) | 33 (12.5) | 0.49 | 62 (11.5) |

| Sibling died, n(%) | 52 (18.5) | 34 (12.6) | 0.06 | 86 (15.6) |

| Adult lives in home who doesn't know child's HIV status, n(%) | 65 (23.2) | 73 (27.1) | 0.29 | 138 (25.1) |

| Someone at school or crèche knows child's HIV status, n(%) | 46 (16.4) | 56 (20.8) | 0.18 | 102 (18.5) |

| Number of other children living in the home, median (IQR) | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 0.77 | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) |

| Caregiver reads to the child, n(%) | 239 (85.4) | 241 (89.6) | 0.13 | 480 (87.4) |

| Child sometimes goes hungry, n(%) | 17 (6.1) | 46 (17.1) | <0.0001 | 63 (11.5) |

ESRU = Empilweni Services and Research Unit; PHRU = Perinatal HIV Research Unit; IQR = Interquartile range; ART = Antiretroviral therapy

Children at PHRU who were not on ART had previously participated in a treatment interruption trial.

The proportion with HIV RNA <400 copies/mL was estimated among children currently on ART.

Full disclosure

Among all 550 children, 50 (9%) had received full disclosure. The median age at disclosure was 6 years (interquartile range 5-7). Prevalence of full disclosure increased with age, from 0% at 4 years of age to 4% at 5 years, 8% at 6 years, and 13%, 16%, and 15% at 7, 8, and 9 years. In addition to age, site and some social characteristics were significantly associated with full disclosure (Table 2). In multivariable logistic regression, age remained the strongest predictor of full disclosure (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2-2.1, p=0.001). An adult living in the household who did not know the child's status was associated with a decreased probability of disclosure to the child (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1-0.9, p=0.02); disclosure to someone at the child's school or crèche was associated with an increased probability (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.0-4.0, p=0.04) and children living in smaller households, i.e., with 0-1 other children, were less likely to know their status compared to households with more children (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2-0.9, p=0.02).

Table 2.

Association of clinical and demographic characteristics with full disclosure to the child.

| Characteristic | N | n (%) full disclosure | Unadjusted odds ratio | p-value | Adjusted odds ratio** | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child characteristics | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Age in years* | 1.7 (1.3-2.2)* | <0.0001 | 1.6 (1.2-2.1) | 0.001 | |||

| 4 | 70 | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| 5 | 96 | 4 (4.2) | |||||

| 6 | 130 | 11 (8.5) | |||||

| 7 | 152 | 19 (12.5) | |||||

| 8 | 89 | 14 (15.7) | |||||

| 9 | 13 | 2 (15.4) | |||||

| Study Site | |||||||

| ESRU | 281 | 16 (5.7) | 0.4 (0.2-0.8) | 0.006 | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | 0.13 | |

| PHRU | 269 | 34 (12.6) | 1 | ||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 253 | 17 (6.7) | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | 0.08 | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | 0.08 | |

| Female | 297 | 33 (11.1) | 1 | ||||

| HIV viral load | |||||||

| Not on ART | 29 | 7 (24.1) | 3.2 (0.6-17.1) | 0.18 | |||

| On ART, VL <400 copies/mL | 498 | 41 (8.2) | 0.9 (0.2-4.0) | 0.89 | |||

| On ART, VL ≥400 copies/mL | 22 | 2 (9.1) | 1 | ||||

| CD4 count | |||||||

| <500 | 27 | 3 (11.1) | 1.2 (0.4-4.3) | 0.73 | |||

| ≥500 | 515 | 47 (9.1) | 1 | ||||

| CD4 percent | |||||||

| <25 | 43 | 6 (14.0) | 1.7 (0.7-4.2) | 0.27 | |||

| ≥25 | 499 | 44 (8.8) | 1 | ||||

| Ever hospitalized | |||||||

| Yes | 317 | 27 (8.5) | 0.8 (0.5-1.5) | 0.57 | |||

| No | 232 | 23 (9.9) | 1 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Caregiver characteristics | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Mother is primary caregiver | |||||||

| Yes | 489 | 43 (8.8) | 0.7 (0.3-1.7) | 0.49 | |||

| No | 61 | 7 (11.5) | |||||

| Age | |||||||

| <40 | 411 | 32 (7.8) | 0.6 (0.3-1.0) | 0.07 | 0.7 (0.3-1.3) | 0.23 | |

| >=40 | 139 | 18 (12.9) | |||||

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 132 | 7 (5.3) | 0.5 (0.2-1.1) | 0.09 | 0.4 (0.2-1.0) | 0.06 | |

| Single/divorced/other | 418 | 43 (10.3) | 1 | ||||

| Education | |||||||

| Less than grade 12 | 300 | 32 (10.7) | 0.6 (0.4-1.2) | 0.16 | |||

| Finished high school | 250 | 18 (7.2) | 1 | ||||

| Caregiver reads to the child | |||||||

| Yes | 480 | 48 (10.0) | 3.7 (0.9-15.7) | 0.07 | 3.3 (0.7-14.3) | 0.12 | |

| No | 69 | 2 (2.9) | 1 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Household characteristics | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Child's biological mother died | |||||||

| Yes | 28 | 4 (14.3) | 1.7 (0.6-5.2) | 0.34 | |||

| No | 520 | 46 (8.8) | 1 | ||||

| Child's father died | |||||||

| Yes | 62 | 6 (9.7) | 1.1 (0.4-2.6) | 0.87 | |||

| No | 476 | 43 (9.0) | 1 | ||||

| Adult lives in home who does not know child's HIV status | |||||||

| Yes | 138 | 6 (4.3) | 0.4 (0.2-0.9) | 0.03 | 0.3 (0.1-0.9) | 0.02 | |

| No | 411 | 44 (10.7) | |||||

| Someone at school or crèche knows child's HIV status | |||||||

| Yes | 102 | 17 (16.7) | 2.5 (1.3-4.7) | 0.004 | 2.0 (1.0-4.0) | 0.04 | |

| No | 448 | 33 (7.4) | |||||

| Number of other children living in the home | |||||||

| 0-1 | 143 | 7 (4.9) | 0.4 (0.2-1.0) | 0.048 | 0.4 (0.2-0.9) | 0.02 | |

| 2 or more | 407 | 43 (10.6) | |||||

| Child sometimes goes hungry due to not enough food in the house | |||||||

| Yes | 63 | 10 (15.9) | 2.1 (1.0-4.4) | 0.05 | 2.0 (0.9-4.5) | 0.10 | |

| No | 483 | 40 (8.3) | 1 | ||||

ESRU = Empilweni Services and Research Unit; PHRU = Perinatal HIV Research Unit; ART = Antiretroviral therapy; VL = viral load

Child age was entered into the logistic model as a continuous variable.

The adjusted model includes all variables with p<0.10 in unadjusted analysis.

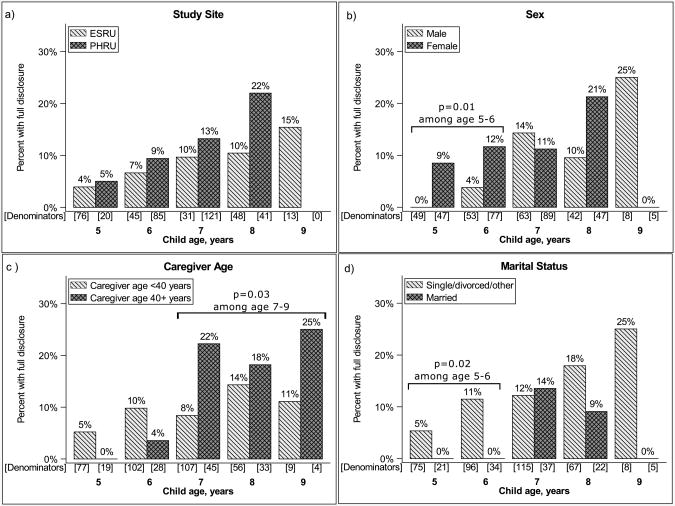

Child age and full disclosure

The increasing probability of disclosure associated with child age is shown within strata of selected characteristics in Figure 1. Across all ages, the prevalence of full disclosure was slightly higher at PHRU than at ESRU, although this difference did not reach statistical significance within age groups (Figure 1a). Girls were significantly more likely to know their status than boys at 5-6 years, while there was no difference by sex at 7-9 years (Figure 1b). Caregivers 40 years of age and older were more likely to report the child had received full disclosure than younger caregivers, though this difference was only significant among children aged 7-9 years (Figure 1c). While the decreased probability of disclosure among married caregivers compared to unmarried caregivers was only marginal in the cohort overall, among children aged 5-6 this difference was significant (Figure 1d). Despite these differences limited to selected age groups, no significant interactions were detected.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of full disclosure among children age 5-9, by child's age and a) study site, b) child's sex, c) caregiver age, and d) caregiver marital status.

ESRU = Empilweni Services and Research Unit; PHRU = Perinatal HIV Research Unit

Age was significantly associated with disclosure within subgroups, including, among children at ESRU (p=0.004) and PHRU (p=0.02); among males (p=0.002) and females (0.001); and among caregivers <40 years (p=0.005) and older (0.008). Age was marginally associated with disclosure among married caregivers (p=0.05) and was significantly associated among unmarried (p=0.0003).

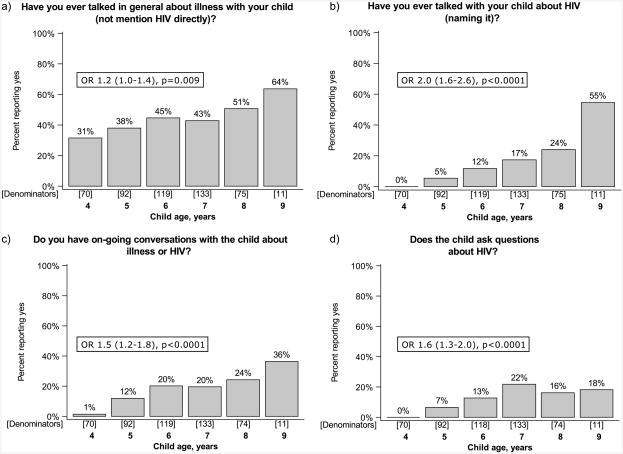

Discussions about illness between caregivers and children

Among caregivers of children who had not received full disclosure, conversations about illness were reported with increasing frequency by age (Figure 2). Among caregivers of children 4 years of age, 31% reported ever having talked in general with the child about illness, increasing to 64% of caregivers of 9 year olds (p=0.009). No caregivers of children aged 4 years reported mentioning HIV directly, increasing to 5% of caregivers of children aged 5 and to 55% of children aged 9 (p<0.0001). Only 1% of caregivers of children 4 years of age reported on-going conversations about illness or HIV, while 36% of caregivers of children aged 9 years reported on-going conversations (p<0.0001). No children aged 4 years asked questions about HIV, while 22%, 16%, and 18% of children aged 7, 8, and 9 years, respectively, had asked about HIV (p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Proportion of caregivers reporting discussions with the child regarding illness and HIV, by age, among children who had not received full disclosure. Odds ratios represent the association of each additional year in age with the odds of reporting each type of discussion.

Among caregivers of children who had received full disclosure, 76% reported general discussions about illness, 86% reported discussions naming HIV, 90% reported on-going conversations about illness or HIV, and 62% reported the child asked questions about HIV. The prevalence of these discussions did not differ by age (data not shown).

Reasons caregivers provide the child about medication and frequent doctor visits

Among children who had not received full disclosure, in response to the open-ended question about why the child goes to the doctor frequently, nearly half (45%) of caregivers reported that it was simply not discussed, that the child never asked, or if the child asked an answer was not provided (Table 3). Among caregivers who did tell the child something about their HIV care without disclosing, most provided vague answers. Answers consistent with the truth ranged from especially vague, e.g., “because you are special” (6%), to vague, e.g., “to prevent illness” (20%) to moderately specific, e.g. “to treat a germ” (5%). Misinformation was not uncommon, with 2% providing vague misinformation such as the medications are vitamins for growth, and 18% providing specific misinformation such as telling the child his or her care was for another illness.

Table 3.

Responses to the question “What have you told your child regarding why he/she is taking medications or going to the doctor frequently?”, separately among caregivers who did and did not report full disclosure to the child.

| Response category | Sample responses | Not full disclosure N=500n (%) | Full disclosure N=50n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not discussed | child never asked; will tell someday; not discussed | 225 (45.0) | 5 (10.0) |

| Especially vague, misinformation | vitamins for growth, child doesn't ask but believes the reason is another health concern | 9 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Especially vague, truth | going to the doctor for a check-up; because you are special; to grow strong | 32 (6.4) | 4 (8.0) |

| Vague and true | because you are sick; to prevent illness or going to the hospital | 101 (20.2) | 4 (8.0) |

| Moderately specific and true | because you were born with a chronic illness; will always need medication; to treat a germ or bug; to treat a problem with blood | 23 (4.6) | 2 (4.0) |

| Specific misinformation | because of a car accident; for a lung/chest/skin problem; for asthma, flu, cancer | 90 (18.0) | 2 (4.0) |

| Specific and true | HIV; checking CD4 count | 0 (0.0) | 31 (62.0) |

| Missing/don't know | 20 (4.0) | 2 (4.0) |

The majority of caregivers who reported that the child had received full disclosure answered this question consistently with full disclosure (62%). Five (10%) reported that it was not discussed because the child never asks. Two (4%) answered that the child was told misinformation. The remainder provided truthful answers with a range of specificity, from “to grow strong” to “to treat a germ”.

Discussion

In this South African cohort of perinatally HIV-infected children 4-9 years old, fewer than 10% had received full disclosure regarding their HIV diagnosis, including only 13%, 16%, and 15% of children aged 7, 8 and 9 years respectively. Among those who had not received full disclosure, fewer than half of caregivers of children aged 4-7 had ever discussed illness in general with the child, increasing to 51% and 64% of caregivers of children aged 8 and 9 years. On-going conversations about illness or HIV with the child were reported by less than half of all caregivers who had not disclosed, including children up to 9 years of age, suggesting a reluctance to tackle disclosure with the child.

In our study, as in others (Atwiine et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2011; Tadesse et al., 2015; Vreeman et al., 2014), increasing age of the child was associated with an increased probability of full disclosure. A recent review reported a range of 1.2% to 75% full disclosure across cohorts of children from low and middle income countries; much of this variation can be explained by the wide range of ages of the children within these studies, including cohorts as young as 0 to 14 years with a mean age of 7 (with 3.2% disclosure) and others including teenagers up to age 19 (with 75% disclosure) (Pinzon-Iregui, Beck-Sague, & Malow, 2013). The low prevalence of disclosure overall in our cohort is consistent with several other studies in sub-Saharan Africa. In Ethiopia, the prevalence of disclosure was 12% in one cohort among children aged 6-10 years (Abebe & Teferra, 2012) and 8% in another cohort among those aged 5-10 years (Tadesse et al., 2015). A study of Ugandan children reported 9.5% prevalence in children aged 5-8 years (Atwiine et al., 2015), and in a Nigerian cohort, prevalence was 9% among those 6-10 years of age (Brown et al., 2011). In these same studies, prevalence of disclosure was higher among adolescents, from 30% in children aged 11-14 in Nigeria (Brown et al., 2011), 56% in children aged 13-14 in Kenya (Vreeman et al., 2014), to 74% in children aged 12-17 in Uganda (Atwiine et al., 2015). Still, guidelines recommend disclosure prior to adolescence, when children transition to managing more of their own health care and may initiate risky behaviors. Data from developing countries in other regions are limited. Two studies from Thailand report a slightly higher prevalence of disclosure, with 21% of children aged 6-10 (Oberdorfer et al., 2006) and 21% of children aged 6-12 years (Sirikum et al., 2014) having received full disclosure.

Other than the child's age, few factors have been found to be associated with disclosure to children. Comparable to a study in Uganda which found that disclosure to others in the household was associated with disclosure to the child (Atwiine et al., 2015), we found that disclosure to adult household members or to others at the child's school or crèche was associated with disclosure to the child. Whether disclosure to others at home or school provides an environment conducive to disclosure to the child, or whether disclosure to the child leads to other disclosures is not known. We might speculate that disclosure to others may provide support to the caregiver in preparation for disclosure to the child, or that other reported disclosures simply reflect an environment less driven by stigma. We also found that in homes with 2 or more other children, disclosure was more likely than in smaller households. This could reflect differences in privacy, in resource sharing, or perhaps experienced parents with more children are better equipped to engage in complex discussions.

Although not significant in multivariable analysis, the difference in the prevalence of full disclosure between ESRU (6% overall) and PHRU (13% overall) was noteworthy. While this was partially driven by the older average age at PHRU, we still observed a trend of increased disclosure at PHRU across all ages. Explicit policies on disclosure support were not in place at either site at the time. Many of the children at PHRU had been in care at that site for a longer duration than children at ESRU, and perhaps a longer relationship with the clinic could contribute to disclosure readiness. Additionally, we observed an association between being off treatment and an increased probability of full disclosure. Because the sole reason for being off treatment in these children was prior participation in a treatment interruption trial, we believe this observation was due to an increased level of counseling in this particular trial.

We did not systematically categorize children as having received “partial” disclosure, but instead described a range of questions asked of caregivers that may indicate stages of partial disclosure. As first described by Funck-Brentano, with partial disclosure to children, developmentally-appropriate information may be shared with the child about their illness without disclosing the diagnosis (Funck-Brentano et al., 1997). We found that about a quarter of caregivers who had not fully disclosed to the child told them vague information about why they were seeing the doctor. Fewer than 5% informed children about the nature of their illness, such as to fight a germ or bug, or having been born with a chronic illness. Nearly a fifth reported telling the child misleading information about his or her illness. When asked generally if caregivers had on-going conversations about illness or HIV, few of those who had not fully disclosed responded yes. These data suggest that partial disclosure was not common in this cohort, which is consistent with other studies (Atwiine et al., 2015; John-Stewart et al., 2013). Nevertheless, roughly one fifth of children aged 7-9 who had not received full disclosure had asked their caregivers questions about HIV, suggesting potential readiness for the disclosure process among these children.

Some studies have reported caregivers' reasons for non-disclosure, including fear that the child is too young for the burden, fear of negative psychological or emotional effects, concern that the child may inadvertently disclose to others, a general sense of not knowing how to disclose, and for mothers, guilt about transmission to the child (Atwiine et al., 2015; Kiwanuka et al., 2014; Lorenz et al., 2016; Pinzon-Iregui et al., 2013). Training that emphasizes incremental disclosure may reduce caregiver anxiety around point-in-time disclosure of the diagnosis, and caregivers may feel that partial disclosure serves as protection against young children inadvertently disclosing to others. Furthermore, a developmentally appropriate incremental process may promote the child's ability to understand the nature of the diagnosis at the time of full disclosure (Lorenz et al., 2016).

Despite consistency in guidelines recommending disclosure, strategies to support caregivers and healthcare providers in this challenging process are not broadly implemented. Two studies have evaluated interventions to train healthcare workers and support caregivers in disclosure to the child (Blasini et al., 2004; O'Malley et al., 2015). Both studies reported that additional training and support not only promoted disclosure but also reduced stress and improved confidence among caregivers and healthcare providers. One of the interventions included intensive counseling and a team approach to disclosure (Blasini et al., 2004), while the other relied primarily on a cartoon book to incrementally inform the child about their illness (O'Malley et al., 2015). We are encouraged that the vast majority of caregivers in our study reported reading to the child; a reading-based intervention may be a simple and feasible option for such communities. These and other intervention strategies require further research on the practicalities of implementation and scale-up. Innovative approaches to integration of disclosure training and support for healthcare workers, caregivers, and their children within standing pediatric ART programs are needed, and must address the long term engagement required across the spectrum of the disclosure process.

Our study has potential limitations. First, we classified “full disclosure” on the basis of one question to the caregiver. It is possible that some children classified as having received full disclosure did not actually understand their diagnosis. Additionally, our clinical trial experienced study population may have a higher prevalence of disclosure than HIV-infected children in South Africa overall. Nonetheless we do not expect that the associations between social factors and disclosure would differ in trial participants compared to non-participants. One strength of our study is the systematic report of discussions about illness and HIV. These data provide insight into the limited readiness for disclosure among these caregivers.

In conclusion, a small minority of school age children had received full disclosure in this South African cohort. Partial disclosure, which may begin with on-going conversations about illness in general, was also not common. A broader public health strategy integrating the disclosure process into pediatric HIV treatment programs is recommended.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under Grants HD 073977 and HD 073952, with additional support from the National Institute of Mental Health under grant T32 MH19105-28.

References

- Abebe W, Teferra S. Disclosure of diagnosis by parents and caregivers to children infected with HIV: prevalence associated factors and perceived barriers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. AIDS Care. 2012;24(9):1097–1102. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.656565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics: Committee on Pediatric AIDS. Disclosure of illness status to children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1):164–166. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwiine B, Kiwanuka J, Musinguzi N, Atwine D, Haberer JE. Understanding the role of age in HIV disclosure rates and patterns for HIV-infected children in southwestern Uganda. AIDS Care. 2015;27(4):424–430. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.978735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasini I, Chantry C, Cruz C, Ortiz L, Salabarria I, Scalley N, et al. Diaz C. Disclosure model for pediatric patients living with HIV in Puerto Rico: design, implementation, and evaluation. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25(3):181–189. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200406000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BJ, Oladokun RE, Osinusi K, Ochigbo S, Adewole IF, Kanki P. Disclosure of HIV status to infected children in a Nigerian HIV Care Programme. AIDS Care. 2011;23(9):1053–1058. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coovadia A, Abrams EJ, Stehlau R, Meyers T, Martens L, Sherman G, et al. Kuhn L. Reuse of nevirapine in exposed HIV-infected children after protease inhibitor-based viral suppression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(10):1082–1090. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coovadia A, Abrams EJ, Strehlau R, Shiau S, Pinillos F, Martens L, et al. Kuhn L. Efavirenz-Based Antiretroviral Therapy Among Nevirapine-Exposed HIV-Infected Children in South Africa: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1808–1817. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton MF, Violari A, Otwombe K, Panchia R, Dobbels E, Rabie H, et al. Team CS. Early time-limited antiretroviral therapy versus deferred therapy in South African infants infected with HIV: results from the children with HIV early antiretroviral (CHER) randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1555–1563. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61409-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funck-Brentano I, Costagliola D, Seibel N, Straub E, Tardieu M, Blanche S. Patterns of disclosure and perceptions of the human immunodeficiency virus in infected elementary school-age children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(10):978–985. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170470012002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John-Stewart GC, Wariua G, Beima-Sofie KM, Richardson BA, Farquhar C, Maleche-Obimbo E, et al. Wamalwa D. Prevalence, perceptions, and correlates of pediatric HIV disclosure in an HIV treatment program in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2013;25(9):1067–1076. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.749333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallem S, Renner L, Ghebremichael M, Paintsil E. Prevalence and pattern of disclosure of HIV status in HIV-infected children in Ghana. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1121–1127. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9741-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiwanuka J, Mulogo E, Haberer JE. Caregiver perceptions and motivation for disclosing or concealing the diagnosis of HIV infection to children receiving HIV care in Mbarara, Uganda: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e93276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn L, Coovadia A, Strehlau R, Martens L, Hu CC, Meyers T, et al. Abrams EJ. Switching children previously exposed to nevirapine to nevirapine-based treatment after initial suppression with a protease-inhibitor-based regimen: long-term follow-up of a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):521–530. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70051-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz R, Grant E, Muyindike W, Maling S, Card C, Henry C, Nazarali AJ. Caregivers' Attitudes towards HIV Testing and Disclosure of HIV Status to At-Risk Children in Rural Uganda. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Department of Health South Africa. National consolidated guidelines for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the management of HIV in children, adolescents and adults. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley G, Beima-Sofie K, Feris L, Shepard-Perry M, Hamunime N, John-Stewart G, et al. group, M. s. “If I take my medicine, I will be strong:” evaluation of a pediatric HIV disclosure intervention in Namibia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(1):e1–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberdorfer P, Puthanakit T, Louthrenoo O, Charnsil C, Sirisanthana V, Sirisanthana T. Disclosure of HIV/AIDS diagnosis to HIV-infected children in Thailand. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42(5):283–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinzon-Iregui MC, Beck-Sague CM, Malow RM. Disclosure of their HIV status to infected children: a review of the literature. J Trop Pediatr. 2013;59(2):84–89. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fms052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O, Rehle T, LC S, Zuma K, Jooste S, Zungu N, et al. South Africa Human Sciences Research Council. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey. Vol. 2012. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sirikum C, Sophonphan J, Chuanjaroen T, Lakonphon S, Srimuan A, Chusut P, et al. team, H.-N. s. HIV disclosure and its effect on treatment outcomes in perinatal HIV-infected Thai children. AIDS Care. 2014;26(9):1144–1149. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.894614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadesse BT, Foster BA, Berhan Y. Cross Sectional Characterization of Factors Associated with Pediatric HIV Status Disclosure in Southern Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. AIDS by the numbers. 2016 http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2016/AIDS-by-the-numbers.

- Violari A, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, Babiker AG, Steyn J, Madhi SA, et al. Team, C. S. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2233–2244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeman RC, Scanlon ML, Mwangi A, Turissini M, Ayaya SO, Tenge C, Nyandiko WM. A cross-sectional study of disclosure of HIV status to children and adolescents in western Kenya. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86616. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guideline on HIV disclosure counselling for children up to 12 years of age. Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]