Abstract

Objective

Health screenings, physical tests that diagnose disease, are underutilized. Motivational interviewing (MI) may increase health screening rates. This paper systematically reviewed the published articles that examined the efficacy of MI for improving health screening uptake.

Methods

Articles published before April 28, 2015 were reviewed from PubMed, PsycINFO, and CINAHL. Study methodology, participant demographics, outcomes and quality were extracted from each article.

Results

Of the 1573 abstracts, 13 met inclusion criteria. Of the 13 studies, 6 found MI more efficacious than a control, 2 found MI more efficacious than a weak control yet equivalent to an active control, and 3 found MI was not significantly better than a control. Two single arm studies reported improvements in health screening rates following an MI intervention.

Conclusions

MI shows promise for improving health screening uptake. However, given the mixed results, the variability amongst the studies and the limited number of randomized trials, it is difficult to discern the exact impact of MI on health screening uptake.

Practice Implications

Future research is needed to better understand the impact of MI in this context. Such research would determine whether MI should be integrated into standard clinical practice for improving health screening uptake.

Keywords: motivational interviewing, health screenings, prevention

1. Introduction

Health screenings are clinical tests that can be used to diagnose disease, often before symptoms are present. Health screenings are important in the detection of early stage disease, and thus can aid in the prevention of both disease progression and mortality. A wide range of diseases including, diabetes, hypertension, sexually transmitted infections, and some types of cancers can be detected through the use of health screenings. Despite their importance, health screenings remain underutilized. For example, in the United States, more than one-third (35.5%) of adults aged 50–75 have not received a colorectal cancer screening within the recommended time frame (e.g., a screening colonoscopy every ten years) [1]; 64% of adults over the age of 18 have never received an HIV test [2]; and 27.6% of women aged 50–74 have not received a mammogram within a two year timeframe [3]. It is critical to implement interventions to improve the uptake of health screenings across the United States.

Motivational interviewing (MI) may help improve the uptake of health screenings. MI is defined as “a collaborative conversation style for strengthening a person’s own motivation and commitment to change.” (p.12) [4]. The intervention is client-centered and helps individuals acknowledge and resolve any ambivalence they might have to change. In the most recent edition of their book, Miller and Rollnick describe that MI involves four processes: (1) engaging the patient in order to form a strong working relationship, (2) focusing the goal or direction of the conversation, (3) evoking the patient’s own motivations for change, and (4) planning for change by increasing the patient’s commitment to change and then developing an action plan.[4] The four processes are not necessarily linear and MI interventionists often move from one process to another. Unlike unidirectional advice giving, MI practitioners use client-centered communication skills, including asking open ended questions, affirming the client’s strengths and previous successes, reflective listening, summarizing, and informing/advising [4].

MI was originally developed to treat substance use, and extensive research supports its efficacy for treating drug, alcohol, and nicotine use [5–8]. More recently, MI has been implemented in healthcare settings to help patients reduce risky behaviors and increase healthy behaviors. Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have examined MI’s efficacy for improving health behaviors. The results of those reviews and meta-analyses found that, although the literature is mixed, MI demonstrates promise in the healthcare arena and, in particular, may help improve behaviors such as diet and exercise, diabetes management, and oral health [6,9–15]. In fact, two meta-analyses reported that MI had significant impacts on physical outcomes (e.g., BMI reduction [16], dental outcomes, HIV viral load [17]).

To our knowledge, no systematic review has examined the efficacy of MI to improve health screening uptake. Health screenings are a key component of disease prevention and it is imperative to understand whether MI can effectively help individuals complete these important screenings. This article will systematically review the published intervention studies that examined the efficacy of MI for improving physical health screening uptake.

2. Methods

2.1 Search Strategy

Articles were reviewed from three electronic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, and CINAHL) that were published on or before April 28, 2015. The search terms varied based on the available search words in the each electronic database. For PubMed, the search terms were (("Mass Screening"[Mesh]) AND ("Motivation"[Mesh] OR "Motivational Interviewing"[Mesh] OR "Counseling"[Mesh] OR "Intervention Studies"[Mesh])). The search was limited by language (English), methodology (case reports, clinical trial phase I-IV, comparative study, controlled clinical trial, evaluation studies, interview, randomized controlled trial, technical report), and sample (humans). Only articles that had a published abstract available were reviewed. This search yielded 448 abstracts.

For PsycINFO, the search terms were ((exp health screening) AND (exp counseling OR exp motivational interviewing OR exp intervention OR exp motivation)). This search was limited by language (English), methodology (clinical case study, empirical study, experimental replication, follow-up study, longitudinal study, prospective study, retrospective study, field study, interview, focus group, nonclinical case study, qualitative study, quantitative study, treatment outcome/clinical trial) and sample (humans). This search yielded 909 abstracts.

For CINAHL, the search terms were ((MH motivation OR MH motivational interviewing OR MH intervention OR MH counseling) and (MH health screening)). This search was limited by language (English), publication type (academic journal), and subjects (humans). Only articles that had a published abstract were reviewed. This search yielded 216 abstracts.

2.2 Selection Strategy

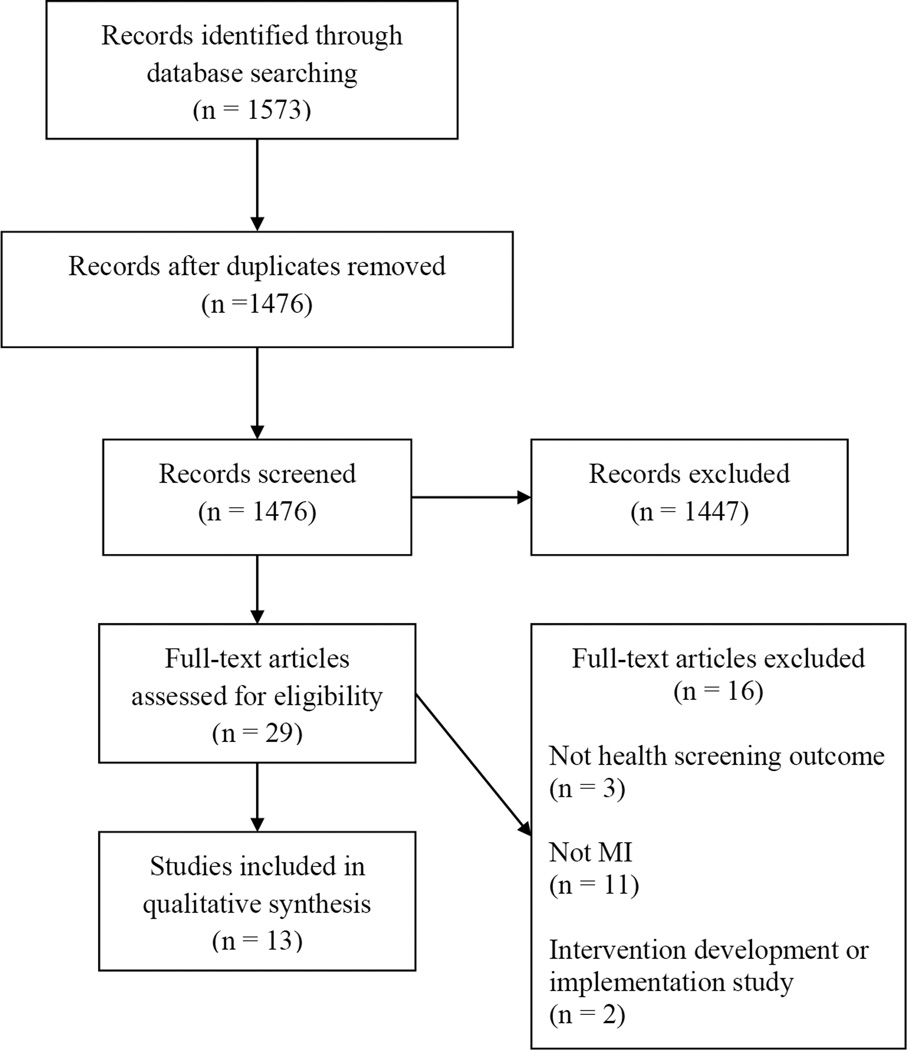

In total, 1573 abstracts were identified through the electronic database search. After removing duplicates, two coders independently reviewed 1476 abstracts to consensus on the following inclusion criteria: (1) implemented an MI intervention (e.g., motivational interviewing, motivational enhancement); and (2) included a health screening as an outcome of the study. Although there are screenings for mental health/behavioral health (e.g., depression screenings, substance abuse screenings), this search was limited to physical health screenings (e.g., cancer screenings, HIV test). In total, 27 abstracts met the aforementioned inclusions criteria. Next, those 27 articles were read in entirety by two independent coders to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. An additional two articles were reviewed in entirety based on the coders’ familiarity with the first author’s research. These two articles, both published by Manne, were included in the 1476 abstracts reviewed; however, they did not discuss the incorporation of MI the abstract. After the 29 articles were read and reviewed, an additional 16 articles were excluded because they did not meet eligibility criteria (e.g., implementation studies). In total, 13 articles were included in the final systematic review. See Figure 1 for a flow diagram of the reviewed articles, in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [18,19].

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

2.3 Data Extraction

A data extraction sheet was used to gather the following information: (1) authors and publication date; (2) participant information (i.e., sample size, race, age, gender); (3) research design (e.g., randomized controlled trial); (4) description of the MI intervention; (5) dose of the MI intervention; (6) description of the comparison group (s); (7) health screening outcome; and (8) major findings and effect sizes.

Each study’s quality was evaluated to consensus by two independent coders. A quality assessment, adapted from previous literature [20–22], was used to assess the follow criteria: (1) groups were randomized, (2) groups were similar at baseline (or differences were statistically controlled for in the analyses), (3) eligibility criteria was described, (4) identification of withdrawals and dropouts, (5) intention to treat analysis was implemented; (6) fidelity of the intervention was monitored. Each item was scored (0=no/not reported; 1=yes) and then all items were summed to create a total quality score (range 0–6).

There was significant variability in the quality and methodologies in the articles, and thus a meta-analysis was not performed. Available effect sizes are reported in the results.

3. Results

3.1 Participant Characteristics

The participant demographics from each of the 13 studies are delineated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Source | Sample size | % Non-white | % White | % Male | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MI improves health screening, RCT | |||||

| Outlaw et al. (2010) | 188 | 100% African American | 0% | 100% | Range = 16–24 Mean = 19.79 SD = 2.2 |

| Valanis et al. (2003) | 501 | Not reported | 83% | 0% | Mean = 59 |

| Manne et al. (2010) | 443 | 1.8% Non-Caucasian | 98.2% | 37% | Mean = 47.6 SD = 13.2 |

| Masson et. al (2013)b | 489 | 28.6%–32% Hispanic 27.5%–31.4% African American 4.1%–11% Other |

35.9%–36.1% | 68.2%–68.4% | Mean = 44.7–45.0 SD = 9.8–10.3 |

| Fortuna et. al (2013)b |

1008 |

Mammography Screening 36.2%–43.4% Non-Hispanic Black 10.9%–21.1% Other (including Hispanic) |

Mammography Screening 42.2%–47.7% |

Mammography Screening 0% |

Mammography Screening Aged 40–49 = 46.8%–53.1% Aged 50–59 = 27.2%–32.0% Aged 60+ = 15.0%–23.7% |

|

CRC Screening 33.1%–37.6% Non-Hispanic Black 12.0%–17.3% Other (including Hispanic) |

CRC Screening 48.0%–52.9% |

CRC Screening 43.3%–48.1% |

CRC Screening Aged 50–59 = 59.2%–64.6% Aged 60+ = 35.4%–40.8% |

||

| Alemagno et al. (2009) | 212 | 68.6% African American | Not reported | 63.3% | Range = 18–62 Mean = 36 |

| MI improves health screening, single arm | |||||

| Costanza et al. (2009) | 45 | Not reported | Not reported | 0% | Aged 45–49 = 24.4% Aged 50–59 = 28.9% Aged 60+ = 46.6% |

| Foley et al. (2005) | 105 | 100% American Indian and Alaska Natives |

0% | 67.6% | Aged 20–30 = 30.5% Aged 31–40 = 35.2% Aged 41–50 = 27.6% Aged 50+ = 6.7% |

| MI is not superior to an active control | |||||

| Taplin et al. (2000) | 1765 | 3.8% Black/African American 0.8% Native American 4.0% Asian/Pacific Islander 2.3% Other |

89% | 0% | Aged 50–59 = 46.3% Aged 60–69 = 27.6% Aged 70–79 = 26.1% |

| Manne et al. (2009) | 412 | 8.6% Non-Caucasian | 90.5% | 39.8% | Mean = 47.9 SD = 9.0 |

| MI does not improve health screening, RCT | |||||

| Chacko et al. (2010) | 376 | 67% African American 18% Hispanic 4% Other |

11% | 0% | Range = 16–21 Mean = 18.5 SD = 1.4 |

| Menon et al. (2011) | 515 | 72.4% Black 9.9% Other |

17.7% | 69.7% | Mean = 58.1 SD = 7.9 |

| Costanza et al. (2007) a | Total sample = 2448 Sample offered MI = 97 |

Not reported | 92% | 43% | Mean = 61.4 Median = 60 Range = 52–77 |

Statistics reported from entire sample

Ranges of percentages across intervention groups

3.2 Study Characteristics

The majority of the studies examined the impact of MI on either cancer screening uptake (N=8) or HIV testing (N=3). The remaining two studies examined the effect of MI on attendance of a hepatitis C screening appointment and on receipt of a screening for sexually transmitted infections. Although all of the studies included in the review implemented some form of MI, the type of MI varied. For example, the dose of the interventions ranged from a one-time 6-minute phone call to a multi session intervention. Furthermore, there was notable variability in the MI interventions’ modes of delivery. Approximately half of the studies implemented the intervention over the telephone, while other studies implemented MI face-to-face or via computer. Two studies did not explicitly report the MI interventions’ modes of delivery. Moreover, the majority of the studies (N=9) delivered MI in combination with another intervention (e.g., print materials, educational presentations).

3.3 Study Quality

The overall quality of the research studies, as defined by our quality scoring assessment, varied amongst the studies. The summed scores ranged from one to six (M=4.38, Median = 5). Of the studies, 11 were randomized clinical trials, 8 had similar groups at baseline (or statistically controlled for differences in the analyses), 12 described eligibility criteria, 6 conducted fidelity monitoring, 8 conducted intent-to-treat analyses, and 12 identified withdrawals and dropouts. The total quality scores are reported in table 2.

Table 2.

Study Outcomes

| Source | Study Design |

Participants | Motivational Interviewing Intervention |

Dose | Comparison Group(s) |

Health Screening Outcome |

Findings | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MI improves health screening, RCT | ||||||||

| Outlaw et al. (2010) | RCT | African American men who have sex with men |

Field outreach + MI Face-to-face MI field outreach session |

One face-to- face 30-minute field outreach session |

Traditional field outreach Field outreach session (e.g., education about HIV) |

HIV counseling and testing |

Participants in the field outreach + MI group were more likely to receive HIV counseling and testing (49%) compared to participants in the traditional field outreach group (20%) (chi squared=17.94; P=.000) |

6 |

| Valanis et al. (2002) Valanis et al. (2003) |

RCT | Women overdue for a mammogram and a pap smear |

Outreach intervention group Mailed tailored letter addressing barriers to screening Participants who did not complete both screening tests after 6 months also received an MI telephone call Inreach intervention group Face-to-face MI session at the time of a primary care appointment Combined intervention group Both inreach and outreach interventions |

Outreach One mailed letter One 15-minute telephone call Inreach One 20-minute, face-to-face session |

Control group Usual Care |

Mammogram and Pap Smear |

< 64 years old Compared to the control group, participants in the outreach intervention group were more likely to receive both a mammogram and a pap smear at 14 months (OR=4.24, 95% CI = 2.22– 8.34) and 24 months (OR 2.53; 95% CI 1.40–4.63) There were no differences between the inreach intervention group and the control group There were no differences between the combined intervention group and the control group > 65 years old No significant differences between interventions groups and the control group |

5 |

| aManne et al. (2010) | RCT | First degree relatives of patients with melanoma who were non- adherent with skin cancer prevention behaviors |

Tailored intervention Three tailored educational mailings and one tailored MI counseling call |

One telephone call Average time = 30.2 minutes |

Generic intervention Three generic educational mailings and a generic educational call |

Total cutaneous skin examination by a health provider (TCE), Skin self- examination (SSE) |

Compared to the generic intervention, participants in the tailored intervention group were 1.94 times more likely to have a total cutaneous skin examination (OR = 1.94; 95% C.I. 1.39,2.72) Participants in the tailored arm were not more likely to perform skin self- examination |

5 |

| Masson et. al (2013) | RCT | Men enrolled in a methadone maintenance treatment program |

Intervention group On site screening for HIV and hepatitis MI enhanced education and counseling Vaccinations and MI enhanced case- management |

2 counseling sessions (pretest and posttest) 6 months of case management |

Control group Non-MI pretest and posttest counseling HIV and Hepatitis testing Off-site referral for vaccine and hepatitis evaluation |

Attendance of an HCV evaluation 286 participants required an HCV evaluation on based on serological testing |

Participants in the intervention group were more likely to receive an HCV evaluation compared to participants in the control group (65.1% vs 37.2%, OR = 4.10; 95% CI = 2.35, 7.17) |

5 |

| Fortuna et. al (2013) |

RCT | Individuals overdue for CRC screening Women overdue for breast cancer screening |

Letter + personal call A mailed letter A telephone call that used MI principles |

One telephone call |

Comparison group Letter A mailed letter Other intervention groups Letter + Audiodial A mailed letter Up to five automated telephone calls Letter + Audiodial + prompt A mailed letter Up to five automated calls Participants and physicians also received paper prompts at a scheduled appointment to discuss cancer screening |

Mammography or CRC screening |

Compared to a letter alone, the letter + personal call group was more effective at improving screening rates for breast cancer (17.8% v 27.5 % AOR 2.2, 95% CI 1.2–4.0) and CRC (12.2% vs. 21.5%; AOR 2.0, 95% CI 1.1–3.9) Participants in the letter + personal call group who received an MI call (reached) were more likely to receive a screening than those who were unable to be reached (30.9% v 20.2%, p=0.05) |

5 |

| Alemagno et al. (2009) | RCT | Criminal justice involved clients |

Brief negotiation interview MI based brief negotiation interviewing session using a “talking laptop” computer |

One 20-minute computerized intervention |

Control group Written educational materials on HIV, STD, TB and hepatitis |

HIV testing | Participants in the brief negotiation interview group (34.6%) were significantly more likely to have an HIV test than participants in the control group (13.6%) (chi-square = 8.4, df = 2, p = .004) |

2 |

| MI improves health screening, single arm | ||||||||

| Costanza et al. (2009) | Single arm trial |

Women overdue for a mammogram ≥27months |

Computer-assisted telephone interviewing with MI Mailed educational booklet Telephone computer- assisted tailored counseling and MI session Assistance scheduling a mammogram |

Not reported | None | Mammogram | Of the 45 participants, 26 (57.8%, 95% CI=43.3, 72.0) of the participants received a mammogram |

2 |

| Foley et al. (2005) | Single arm trial |

Substance users in a residential treatment program |

Intervention Group HIV prevention educational presentation Individual MI session |

One 60-minute educational, group presentation One 30-minute face-to-face intervention |

None | HIV testing | 78% of participants (105/134) received HIV testing |

1 |

| MI does not add additional benefit to active control | ||||||||

| Taplin et al. (2000) | RCT | Women who had not scheduled a recommended mammography |

Motivational call MI telephone call |

One telephone call Average time = 8.5 minutes |

Reminder Postcard Postcard that reminded participants about the recommended mammography Reminder Telephone Call Telephone call that reminded participants about the mammography and assisted in scheduling the appointments |

Mammogram | Participants in the motivational call group were more likely to receive a mammogram than participants in the reminder postcard group (OR=1.8 95% CI 1/5-2.2) Participants in the reminder telephone call group were more likely to receive a mammogram than participants in the reminder postcard group (OR=1.9, 95% CI 1.5,2.3) No statistical differences between the motivational interviewing telephone call group and the reminder call group |

6 |

| aManne et al. (2009) | RCT | Individuals who were overdue for a CRC screening and had a sibling diagnosed with CRC |

Tailored print plus telephone counseling group Mailed personal cover letter and tailored booklet MI telephone counseling session Follow up tailored newsletter |

One telephone call Average time = 19 minutes |

Generic print group Mailed cover letter and generic pamphlet about CRC screening Tailored print group Mailed personal cover letter and tailored booklet about CRC screening One tailored follow up newsletter |

CRC screening | Participants in the tailored print plus telephone counseling group were significantly more likely to be screened than those in the generic print group (Wald Chi-Square=4.40; p =0.036) Participants in the tailored print group were more likely to be screened than those in the generic print group (Wald Chi- Square=6.15; p=0.013) No significant differences between the two tailored intervention groups |

5 |

| MI does not improve health screening, RCT | ||||||||

| Chacko et al. (2010) | RCT | Adolescent women attending a community- based, urban clinic that provided free reproductive health care |

Intervention + standard care MI intervention Clinical care and risk reduction counseling |

One 30–50 minute baseline session One 30–50 minute two week follow up session One 15-minute six month follow up session |

Standard care Clinical care and risk reduction counseling |

STI screening | No significant differences between study groups |

6 |

| Menon et al. (2011) | RCT | Primary care patients who had no family history of CRC and were non- adherent with CRC screening |

Motivational Interviewing Telephone-based MI session |

One telephone call Average time = 21.2 minutes |

Tailored Counseling Tailored scripted telephone intervention Control Group Possible referral for a CRC screening |

CRC screening | No significant differences between the MI group and the control group (OR=1.6, 95% C.I. 0.9,2.9) Participants in the tailored counseling group were 2.2 times more likely to receive a CRC screening than participants in the control group (OR=2.2; 95% C.I. 1.2, 4.00) |

5 |

| Costanza et al. (2007) | RCT | Primary care patients who had not had a colonoscopy within the past 10 years |

Intervention Mailed educational brochure on CRC and screening Computer-assisted counseling telephone call Participants who were not planning on getting tested (N=97) were offered MI counseling |

One telephone call Average time of MI component = 6 minutes |

Control group Usual care |

Colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, or fecal occult blood testing |

There were no statistically significant differences between the intervention and control groups Of those participants who were offered MI, 19.5% changed their screening intentions (N=19/97) |

4 |

Acronym Key:

RCT = Randomized Control/Clinical Trial

MI = Motivational Interview

CRC = Colorectal Cancer

STD = Sexually Transmitted Disease

TB = Tuberculosis

TCE = Total Cutaneous Skin Examination

SSE = Skin Self-Examination

HCV = Hepatitis C Virus

STI = Sexually Transmitted Infection

Note:

Article selected due to the authors’ familiarity with the research.

3.4 Main Effect of MI on Health Screening Uptake

Several studies examined the impact of MI on multiple behaviors, however, only the results relevant to health screening uptake are reported and analyzed in the current paper. Overall, the results regarding the impact of MI on health screening uptake were mixed. Six studies [23–28] reported that MI significantly improved health screening uptake, when compared to a control group. Furthermore, two single arm studies [29,30] reported an increase in health screening rates after receiving the MI intervention.

Two studies reported that MI performed significantly better than a minimal comparison group, yet did not provide additional benefit when compared to an active control group. In particular, Taplin and colleagues [31] found that an MI telephone call was more efficacious than a reminder postcard to improve mammography uptake; however, the MI call was no more efficacious than a reminder telephone call. Additionally, Manne and colleagues [32] found that participants who received tailored print materials and an MI counseling telephone call were more likely to receive colorectal cancer screening than participants who received a generic print intervention. The MI intervention, however, did not provide additional benefit to a tailored print material alone.

Finally, three studies (23%) [33–35] did not find a significant impact of MI on health screening uptake. The results of the studies are reported in Table 2.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

Although the systematic review produced mixed results, overall MI holds promise for improving health screening uptake. Six of the thirteen studies found that an MI intervention was able to significantly improve health screening uptake, compared to a control group. In particular, these studies found MI efficacious for improving mammography, pap smears, HIV testing/counseling, colorectal cancer screenings, and total cutaneous skin examinations. Five of these six studies had quality ratings of five or greater. These studies support the clinical integration of MI to help improve health screening uptake. Of note, one of the six studies [24] found that individuals who received a tailored intervention which incorporated MI were more likely to have a total cutaneous skin examination but not skin self-examination. Although this study yielded positive findings, the overall results remain mixed.

In addition, two single arm studies found that participants who received an MI intervention had increases in health screening rates, particularly HIV testing and mammography. Due to the studies’ methodologies, there is high potential for bias (quality scores ranged from 1–2) and thus the results should be interpreted cautiously. Although these results are promising, in the absence of randomized clinical trials, we are unable to determine the true impact of MI in these studies.

Furthermore, two high quality studies reported that MI was significantly better than a minimal comparison group, yet did not provide additional benefit when compared to an active control group. These studies provide additional support for the efficacy of MI in this context. However, these results also call into question the necessity and cost effectiveness of implementing MI interventions over more parsimonious treatment options.

Finally, three studies reported that MI did not have a statistically significant impact on health screening uptake. The first study, conducted by Menon and colleagues [34], found that a telephone based MI session did not improve colorectal cancer screening uptake among primary care patients. The odds ratio, however, approached statistical significance (OR=1.6, 95% C.I. 0.9, 2.9). A second study, conducted by Constanza and colleagues [35], examined whether a telephone, computer-assisted counseling intervention could improve colorectal cancer screening rates. Within the intervention group, individuals who reported that they were not planning on getting screened for colorectal cancer were offered MI counseling. The results found that the intervention did not significantly impact colorectal cancer screening rates. Of note, of the 582 participants who received the computer-assisted counseling intervention, only 97 reported that they were not planning on getting screened for colorectal cancer and were thus eligible for MI counseling. Of the 97 participants who were offered MI counseling, 25 (25.7%) refused the additional counseling. Therefore, of the 582 participants in the intervention group, only 97 were even offered MI and only 72 accepted the counseling. Within that group of 97, 19 (19.5%) changed their intentions to get screened. Because MI was not offered to all of the participants, it is difficult to discern the exact impact that MI had on colorectal cancer screening in this context.

A third study, which received a quality rating of six, conducted by Chacko and colleagues [33] found that an MI intervention did not significantly improve screening for sexually transmitted infections among women attending a reproductive clinic. Interestingly, this study was the only study included in the review that implemented MI to improve young adults’/adolescents’ health screening behaviors. Moreover, it was the only study which examined the impact of MI on improving screenings for sexually transmitted infections. Future research is needed to determine whether age and/or outcome moderate the impact of MI intervention on health screening uptake.

Amongst the 13 studies included in systematic review, there was substantial variability in the mode of delivery of MI. Approximately half the studies implemented MI over the telephone, while the other studies conducted the MI in person or via a computer. The mode of delivery of MI did not appear to impact the efficacy of the intervention. These results suggest that more parsimonious and cost-effective methods of delivery (e.g., telephone or computer) may be sufficient to produce behavior change with regard to health screening uptake.

There were several factors that limited our ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding the impact of MI on health screening uptake. Most notably, there was substantial variability in the operational definitions of MI. Some studies provided minimal details regarding the MI intervention while other studies published detailed implementation papers that clearly delineated the MI methods employed in the intervention [e.g., 36]. It is important that future research more clearly defines and describes the MI interventions and how they are being implemented within the study. Such details would allow for more accurate comparisons amongst studies and lay the foundation for future replications studies. Additionally, publishing the details of the intervention provides guidelines for practitioners to disseminate the interventions into standard clinical practice.

Moreover, the majority of the studies included in the systematic review implemented MI in conjunction with other active treatments, such as print materials. In the larger literature, MI is frequently used as an adjunct or a prelude to other empirically supported treatments (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, education, self-help manuals) [7]. In fact, it has been argued that combining MI with other treatments may enhance the impact of both interventions on behavioral change [7]. Although combination treatments are often efficacious, with regard to the systematic review, it is difficult to determine the exact impact that MI has on improving health screenings. Future dismantling studies are needed to better understand whether MI serves as a driving component of change in the intervention package. Furthermore, the combination of MI with other treatments poses difficulties in the assessment of treatment fidelity [37].

There are limitations to the systematic review that may have impacted the results. First, there is the potential for publication bias, which could have positively skewed the findings. It is commonly known that null results are often under published [38]. We did not seek the results of unpublished studies, and thus may have missed critical null results. Second, as was pervious discussed, the majority of the studies included in the systematic review implemented MI as an adjunct to a larger treatment. It is possible that studies did not report the MI component of the intervention in the abstract, and thus were missed by our search strategy. In fact, as was previous reported, we were aware of two articles that incorporated MI yet were missed by our search strategy. Third, it is possible that our inclusion criteria were too specific and thus we may have missed relevant articles. In particular, our review search was limited to three databases (PubMed, PsycINFO and CINAHL) and excluded publications that were not in English. Furthermore, only full articles were reviewed and therefore relevant publications (e.g., dissertations, presentations) may have been missed. Future research could conduct a more exhaustive review in order to expand upon the results. Fourth, due to the limited number of articles and the heterogeneity amongst the studies, a formal meta-analysis was not conducted. As this area of research expands, a future study should conduct a meta-analysis to better understand the effect size that MI has on improving health screening uptake.

4.2 Conclusions

Overall, the results of the systematic review were mixed. Of the 13 studies, 6 found MI more efficacious than a control, 2 found MI more efficacious than a weak control yet equivalent to an active control, and 3 found MI was not significantly better than a control. Two single arm studies reported improvements in health screening rates following an MI intervention. While MI shows promise for improving health screening uptake; it may not be the most parsimonious intervention option. Unfortunately, given the mixed results, the wide variability amongst the studies and the limited number of randomized clinical trials, it is difficult to discern the exact impact that MI has on health screening uptake.

4.3 Practical Implications

Future, more detailed, research is needed to better understand the impact that MI can have on health screenings in this context. Furthermore, implementation papers are needed in order to better explain how MI is defined and implemented in each study. This future research would provide further support for the integration of MI into standard clinical practice to improve health screening uptake among adults.

Highlights.

1573 abstracts reviewed to determine the impact of MI on health screenings

MI shows promise for improving health screening uptake

However, there was wide variability in the methods and quality of the studies

Limited ability to draw definitive conclusions about impact of MI in this context

More research is needed to determine whether MI can improve health screening uptake

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by the National Cancer Institute (K07CA19072601A1) and the American Cancer Society (122931-PF-12-117-01-CPPB). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the American Cancer Society, the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Steele CB, Rim SH, Joseph DA, King JB, Seeff LC National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Colorectal cancer incidence and screening - United States, 2008 and 2010. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2013;62(Suppl 3):53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackwell D, Lucas J, Clarke T. Summary health statics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. 2014;10(260) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer Screening - Unites States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2012;61:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Martens MP, McDevitt-Murphy ME. Computerized versus motivational interviewing alcohol interventions: impact on discrepancy, motivation, and drinking. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2010;24:628–639. doi: 10.1037/a0021347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundahl B, Burke BL. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: a practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009;65:1232–1245. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasilaki EI, Hosier SG, Cox WM. The efficacy of motivational interviewing as a brief intervention for excessive drinking: a meta-analytic review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:328–335. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Copeland L, McNamara R, Kelson M, Simpson S. Mechanisms of change within motivational interviewing in relation to health behaviors outcomes: a systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015;98:401–411. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erickson SJ, Gerstle M, Feldstein SW. Brief interventions and motivational interviewing with children, adolescents, and their parents in pediatric health care settings: a review. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2005;159:1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martins RK, McNeil DW. Review of Motivational Interviewing in promoting health behaviors. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009;29:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundahl B, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Resnicow K, DiIorio C, Soet JE, Borrelli B, Hecht J, Ernst D. Motivational Interviewing In Health Promotion: It Sounds Like Something Is Changing. Health Psychology. 2002;21:444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003;71:843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong MJ, Mottershead TA, Ronksley PE, Sigal RJ, Campbell TS, Hemmelgarn BR. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev. 2011;12:709–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundahl B, Moleni T, Burke BL, Butters R, Tollefson D, Butler C, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013;93:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Altman DG, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J. PRISMA statement. Epidemiology. 2011;22:128. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181fe7825. author reply 128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010;8:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control. Clin. Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verhagen AP, de Vet HC, de Bie RA, Kessels AG, Boers M, Bouter LM, Knipschild PG. The Delphi list: a criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998;51:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sucala M, Schnur JB, Constantino MJ, Miller SJ, Brackman EH, Montgomery GH. The therapeutic relationship in e-therapy for mental health: a systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012;14:e110. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masson CL, Delucchi KL, McKnight C, Hettema J, Khalili M, Min A, Jordan AE, Pepper N, Hall J, Hengl NS, Young C, Shopshire MS, Manuel JK, Coffin L, Hammer H, Shapiro B, Seewald RM, Bodenheimer HC, Jr, Sorensen JL, Des Jarlais DC, Perlman DC. A randomized trial of a hepatitis care coordination model in methadone maintenance treatment. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103:e81–e88. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manne S, Jacobsen PB, Ming ME, Winkel G, Dessureault S, Lessin SR. Tailored versus generic interventions for skin cancer risk reduction for family members of melanoma patients. Health Psychol. 2010;29:583–593. doi: 10.1037/a0021387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Outlaw AY, Naar-King S, Parsons JT, Green-Jones M, Janisse H, Secord E. Using motivational interviewing in HIV field outreach with young African American men who have sex with men: a randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S146–S151. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alemagno SA, Stephens RC, Stephens P, Shaffer-King P, White P. Brief motivational intervention to reduce HIV risk and to increase HIV testing among offenders under community supervision. J. Correct. Health. Care. 2009;15:210–221. doi: 10.1177/1078345809333398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valanis B, Whitlock EE, Mullooly J, Vogt T, Smith S, Chen C, Glasgow RE. Screening rarely screened women: time-to-service and 24-month outcomes of tailored interventions. Prev. Med. 2003;37:442–450. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fortuna RJ, Idris A, Winters P, Humiston SG, Scofield S, Hendren S, Ford P, Li SX, Fiscella K. Get screened: a randomized trial of the incremental benefits of reminders, recall, and outreach on cancer screening. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014;29:90–97. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2586-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foley K, Duran B, Morris P, Lucero J, Jiang Y, Baxter B, Harrison M, Shurley M, Shorty E, Joe D, Iralu J, Davidson-Stroh L, Foster L, Begay MG, Sonleiter N. Using motivational interviewing to promote HIV testing at an American Indian substance abuse treatment facility. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 2005;37:321–329. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2005.10400526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costanza ME, Luckmann R, White MJ, Rosal MC, LaPelle N, Cranos C. Moving mammogram-reluctant women to screening: a pilot study. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009;37:343–349. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9107-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taplin SH, Barlow WE, Ludman E, MacLehos R, Meyer DM, Seger D, Herta D, Chin C, Curry S. Testing reminder and motivational telephone calls to increase screening mammography: a randomized study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000;92:233–242. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manne SL, Coups EJ, Markowitz A, Meropol NJ, Haller D, Jacobsen PB, Jandorf L, Peterson SK, Lesko S, Pilipshen S, Winkel G. A randomized trial of generic versus tailored interventions to increase colorectal cancer screening among intermediate risk siblings. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009;37:207–217. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9103-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chacko MR, Wiemann CM, Kozinetz CA, von Sternberg K, Velasquez MM, Smith PB, DiClemente R. Efficacy of a motivational behavioral intervention to promote chlamydia and gonorrhea screening in young women: a randomized controlled trial. J. Adolesc. Health. 2010;46:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menon U, Belue R, Wahab S, Rugen K, Kinney AY, Maramaldi P, Wujcik D, Szalacha LA. A randomized trial comparing the effect of two phone-based interventions on colorectal cancer screening adherence. Ann. Behav. Med. 2011;42:294–303. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9291-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Costanza ME, Luckmann R, Stoddard AM, White MJ, Stark JR, Avrunin JS, Rosal MC, Clemow L. Using tailored telephone counseling to accelerate the adoption of colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2007;31:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wahab S, Menon U, Szalacha L. Motivational interviewing and colorectal cancer screening: a peek from the inside out. Patient Educ. Couns. 2008;72:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haddock G, Beardmore R, Earnshaw P, Fitzsimmons M, Nothard S, Butler R, Eisner E, Barrowclough C. Assessing fidelity to integrated motivational interviewing and CBT therapy for psychosis and substance use: the MI-CBT fidelity scale (MI-CTS) J. Ment. Health. 2012;21:38–48. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.621470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337:867–872. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]