Abstract

Injury to axons of the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS) is accompanied by the upregulation and downregulation of numerous molecules that are involved in mediating nerve repair, or in augmentation of the original damage. Promoting the functions of beneficial factors while reducing the properties of injurious agents determines whether regeneration and functional recovery ensues. A number of chaperone proteins display reduced or increased expression following CNS and PNS damage (crush, transection, contusion) where their roles have generally been found to be protective. For example, chaperones are involved in mediating survival of damaged neurons, promoting axon regeneration and remyelination and, improving behavioral outcomes. We review here the various chaperone proteins that are involved after nervous system axonal damage, the functions that they impact in the CNS and PNS, and the possible mechanisms by which they act.

Keywords: peripheral nerve injury, spinal cord injury, axotomy, chaperones, chaperone proteins, regeneration, neuronal cell death, myelination

PNS and CNS nerve damage

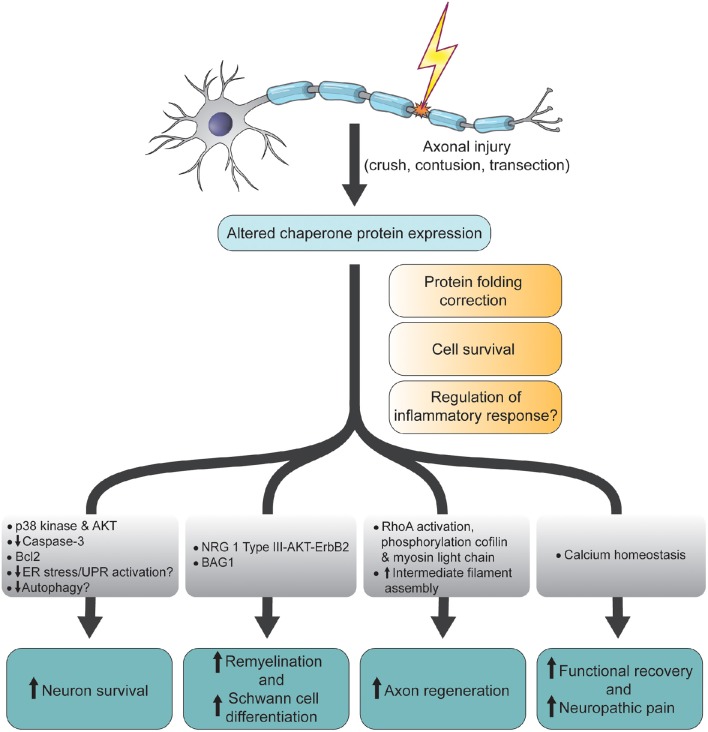

Following damage to the axons of central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) neurons, a number of cellular and molecular processes are initiated to promote regeneration of damaged nerve fibers, remyelination and target reinnervation (Zochodne, 2008). In the injured PNS for example, re-expression of regeneration associated genes (RAGs) such as c-jun and growth associated protein-43, are involved in axon outgrowth (Hall, 2005; Zochodne, 2008) while inhibitory axonal and myelin debris is phagocytosed by Schwann cells and infiltrating hematogenously-derived macrophages (Waller, 1850; Gaudet et al., 2011). Schwann cells also (Liu H. M. et al., 1995) secrete neutrophic factors (Madduri and Gander, 2010) and adhesion molecules (Colognato et al., 2005; Nodari et al., 2008) that allow for survival and directional growth of regenerating axons. Because of these favorable conditions, axotomized PNS neurons generally regenerate robustly, although less so in humans. Compared to the PNS however, injured CNS neurons regrow poorly and this has been attributed to reduced and/or premature truncation of beneficial processes. For example, the damaged CNS displays inadequate RAG expression, poor immune responses and, death of oligodendrocytes (David and Ousman, 2002). As a consequence, many labs are interested in identifying the molecular factors that promote axon regeneration in the damaged CNS and PNS. Over the last three decades, it has become evident that chaperone proteins are involved in the PNS and CNS after nerve damage. This mini-review will focus on which chaperones have been found to be modulated following axon damage (Table 1) and, the functions that they have been assigned (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Expression of chaperone proteins after CNS and PNS axotomy.

| Protein | PNS/CNS, species | Tissue | Cell type | Change | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alphaB-crystallin | CNS, mouse | Spinal cord | Astrocytes and oligodendrocytes | Decreased | Klopstein et al., 2012 |

| PNS, rat | DRG | Neurons | Increased | Willis et al., 2005 | |

| PNS, mouse | Sciatic nerve | Schwann cells and neurons | Decreased | Lim et al., 2017 | |

| BAG1 | PNS, rat | Sciatic nerve | Schwann cells | Increased | Wu et al., 2013 |

| BiP | CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Neurons and glia | Unchanged | Penas et al., 2007 |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Neurons and glia | Decreased | Penas et al., 2011a | |

| Clusterin | CNS, rat | Hippocampus | Astrocytes and neurons | Increased | Lampert-Etchells et al., 1991 |

| CNS, rat | Brain | Non-neuronal | Increased | Zoli et al., 1993 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Astrocytes and oligodendrocytes | Increased | Liu et al., 1998 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Glia | Increased | Liu L. et al., 1995 | |

| CNS, rat | Red nucleus | Neurons and glia | Increased | Liu et al., 1999 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Neurons and glia | Increased | Klimaschewski et al., 2001 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord and brain | Neurons and glia | Increased | Törnqvist et al., 1996 | |

| PNS, rat | Sciatic nerve | Non-specific | Increased | Bonnard et al., 1997 | |

| PNS, rat | Sciatic nerve | Schwann cells | Increased | Wright et al., 2014 | |

| PNS, rat | Hypoglossal nerve | Neurons and glia | Increased | Törnqvist et al., 1996 | |

| PNS, rat | Hypoglossal nerve | Neurons and glia | Increased | Svensson et al., 1995 | |

| GRP75 | PNS, rat | DRG | Neurons | Increased | Willis et al., 2005 |

| GRP94 | CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Neurons and astrocytes | Increased | Xu et al., 2011 |

| HSP25 | CNS and PNS, mouse | Spinal cord and sciatic nerve | Neurons | Increased | Murashov et al., 2001 |

| PNS, rat | Inferior alveolar nerve | Schwann cells, neurons, and endothelial cells | Increased | Iijima et al., 2003 | |

| HSP27 | CNS, hamster | Retina | Retinal ganglion cells | Increased | Liu et al., 2013 |

| CNS, mouse | Spinal cord | n/a | Increased | Yi et al., 2008 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | n/a | Increased | Zhang et al., 2010 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | n/a | Increased | Park et al., 2007 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Neurons | Increased | Keeler et al., 2012 | |

| CNS, rat | Brainstem | Neurons | Increased | Vinit et al., 2011 | |

| CNS, rat | Retina | Retinal ganglion cells | Increased | Hebb et al., 2006 | |

| CNS, rat | Retina, optic tract, and superior colliculus | Retinal ganglion cells and astrocytes | Increased | Krueger-Naug et al., 2002 | |

| CNS, rat | Medulla oblongata | Neurons | Increased | Hopkins et al., 1998 | |

| CNS, rat | Retina, optic nerve, optic tract, lateral geniculate leaflet, visual cortex | Non-specific; astrocytes | Increased | Chidlow et al., 2014 | |

| CNS and PNS, rat | Sciatic nerve, DRG, spinal cord | Neurons | Increased w/anterograde transport | Costigan et al., 1998 | |

| PNS, rat | Sciatic nerve | Schwann cells | Increased | Hirata et al., 2003 | |

| PNS, rat | DRG | Neurons | Increased | Benn et al., 2002 | |

| PNS, rat | Sciatic nerve | Non-specific | Increased | Klass et al., 2008 | |

| PNS, rat | Sciatic nerve | Non-specific | Increased | Kim et al., 2001 | |

| PNS, rat | Sciatic nerve | n/a | Increased | Tsubouchi et al., 2009 | |

| HSP30 | CNS, goldfish | Retina | n/a | Increased | Cauley et al., 1986 |

| HSP32 | CNS, mouse | Spinal cord | n/a | Increased | Yi et al., 2008 |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | n/a | Increased | Park et al., 2007 | |

| HSP60 | PNS, rat | DRG | Neurons | Increased | Willis et al., 2005 |

| HSP70 | CNS, zebrafish | Optic nerve | Retinal ganglion cells | Increased | Nagashima et al., 2011 |

| CNS, rabbit | Spinal cord | Neurons | Increased | Sakurai et al., 1997 | |

| CNS, mouse | Spinal cord | n/a | Increased | Yi et al., 2008 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Neurons and glia | Increased | Gower et al., 1989 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Macrophages and glia | Increased | Mautes and Noble, 2000; Mautes et al., 2000 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | n/a | Increased | Park et al., 2007 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | n/a | Increased | Sengul et al., 2013 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | n/a | Increased | Zhang et al., 2010 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Non-specific | Increased | Song et al., 2001 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Neurons | Increased | Keeler et al., 2012 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Non-specific | Increased | Kalmar et al., 2003 | |

| CNS, rat | Retina, optic nerve, optic tract, lateral geniculate leaflet, visual cortex | Non-specific | No change | Chidlow et al., 2014 | |

| CNS & PNS, dog | Spinal cord and DRG | Neurons and glia | Increased | Cízková et al., 2005 | |

| PNS, hamster | Facial nerve | Non-specific | Increased | New et al., 1989 | |

| PNS, frog | Sciatic nerve | Neurons | Retrograde transport | Edbladh et al., 1994 | |

| PNS, rat | Sciatic nerve | Non-specific | Increased | Klass et al., 2008 | |

| HSP72 | CNS, rat | Spinal cord | n/a | Increased | Sharma et al., 2015 |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Neurons | Increased | Sharma et al., 2006 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Non-specific | Increased | Tachibana et al., 2002 | |

| CNS, rat | Spinal cord | n/a | Increased | Chang et al., 2014 | |

| PNS, rat | External carotid nerve ganglion | Schwann cells and neurons | Increased | Hou et al., 1998 | |

| HSP90 | CNS, rat | Spinal cord | n/a | Increased nitration | Franco et al., 2013 |

| PNS, rat | Sciatic nerve | Non-specific | Increased | Klass et al., 2008 | |

| HSP90ab1 | CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Non-specific | Decreased | Zhou et al., 2014 |

| HSPa4 | CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Non-specific | Decreased | Zhou et al., 2014 |

| HSPe1 | CNS, rat | Spinal cord | Non-specific | Decreased | Zhou et al., 2014 |

| σ1R | PNS, rat | DRG | Neurons and satellite glia | Decreased | Bangaru et al., 2013 |

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram summarizing the functions and molecular changes associated with altered chaperone protein expression following CNS and PNS axonal injury. ER, endoplamic reticulum; UPR, unfolded protein response; NRG, neuregulin; Bcl2, B-cell lymphoma 2; BAG1, Bcl-2-associated athanogene-1; AKT, AKT8 virus oncogene cellular homolog; p38, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase.

Chaperone proteins

There are thousands of original manuscripts and reviews on chaperone proteins and so we will only introduce them in general terms here. Proteins have to be in a specific conformation in order to perform their functions. When cells experience stresses such as high and low temperatures, altered pH, oxygen deprivation, or disease states, proteins have difficulty in forming and maintaining their proper structures. Also, misfolded proteins can cause correctly structured ones to unfold. If not corrected, misfolded proteins can form aggregates that could lead to cell death (Reddy et al., 2008). Chaperones assist in the correct non-covalent assembly of polypeptides. They have the ability to recognize unfolded or partially denatured proteins and prevent incorrect associations and aggregation of unfolded polypeptide chains (Derham and Harding, 1999). In addition to correcting protein misfolding, some chaperones such as heat shock protein (HSP)70 and alphaB-crystallin (αBC)/HSPB5 promote (Campisi and Fleshner, 2003) or suppress (Ousman et al., 2007) inflammatory responses, while others such as HSP27 and αBC are involved in cell survival (Parcellier et al., 2005). Chaperones therefore play an important role in maintaining cell homeostasis and survival.

Expression of chaperones after PNS and CNS nerve injury

Hsps were one of the earliest chaperones discovered to have altered expression after PNS and CNS axonal damage. Cauley et al. (1986) found that expression of a 30 kDa HSP was augmented after optic nerve crush in goldfish. HSP70 was subsequently discovered to be induced after facial nerve axotomy in hamsters (New et al., 1989) and following crush damage to rat spinal cords (Gower et al., 1989), along with the ability to be retrogradely transported in damaged frog sciatic nerves (Edbladh et al., 1994). Other groups have also observed augmented expression of HSP70 in transected zebrafish optic nerves (Nagashima et al., 2011) and rat spinal cord (Keeler et al., 2012) as well as in macrophages and astrocytes after spinal cord contusion in rats (Mautes and Noble, 2000). After these first observations, increased expression of other hsps including HSP25 (Iijima et al., 2003) and HSP27 (Hirata et al., 2003) has been noted in the retina, optic tract and superior colliculus of transected rat optic nerves (Krueger-Naug et al., 2002; Hebb et al., 2006), in transected rat spinal cord (Keeler et al., 2012), and in inferior alveolar and sciatic nerves and their associated Schwann cells and dorsal root ganglia (DRG) (Costigan et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2001). Of interest, there may be some selectivity in the location of HSP27 and phosphorylated-HSP27 after cervical spinal cord injury since the hsp was found to be expressed only in subpopulations of injured neurons in the rostral ventral respiratory group, the dorsal part of the gigantocellularis (Gi), and vestibular nucleus, but seldom in the ventral Gi and raphe nucleus (Vinit et al., 2011). Work by Willis et al. (2005) expanded the list of HSPs found to be enhanced in the injured PNS to include HSP60, glucose-regulated protein (GRP)75 and αBC which they discovered were capable of being synthesized within damaged PNS axons. In the CNS, increases in the levels of HSP32, HSP72 and HSP90 were evident following transection of the spinal cord and even after constriction and transection of peripheral nerves (Klass et al., 2008; Sharma et al., 2015). The latter observation showed that PNS nerve damage could alter expression of hsps in the CNS.

Other chaperone proteins besides hsps have been associated with axonal damage in the PNS and CNS. In 1997, Bonnard et al. (1997) found that clusterin/ApoJ/sulfated glycoprotein-2 mRNA increased in rat sciatic nerve after crush damage with expression of the chaperone possibly being specific to sensory axons as observed in a mouse sciatic nerve transection paradigm (Wright et al., 2014). Since the Bonnard observation, an augmentation in clusterin mRNA and protein has also been seen in numerous nerve injury scenarios including the spinal cord dorsal horn and gracile nucleus following rat sciatic nerve transection (Liu L. et al., 1995), the rat hippocampus after entorhinal cortex lesioning (Lampert-Etchells et al., 1991), the mesodiencephalic after hemitransection (Zoli et al., 1993), and the hypoglossal nucleus after hypoglossal nerve transection (Svensson et al., 1995). Finally, GRP94 is another chaperone whose expression increases after contusion injury in the rat spinal cord (Xu et al., 2011) while Bcl-2-associated athanogene-1 (BAG1), a co-chaperone for HSP70/HSC70 expression, is enhanced in Schwann cells following sciatic nerve crush in rats (Wu et al., 2013).

Not all chaperones however are augmented after PNS and CNS injury. Klopstein et al. (2012) noted a reduction in the small hsp, αBC, after spinal cord contusion injury in mice, and we have also observed a decrease in this crystallin after sciatic nerve crush damage in mice (Lim et al., 2017). Further, sigma-1 receptor (σ1R), an endoplasmic reticulum chaperone protein which is present in both sensory neurons and satellite cells in rat DRGs, was found to be downregulated in neurons as well as in their accompanying satellite glial cells after sciatic nerve ligation (Bangaru et al., 2013). HSP60 is another chaperone that was decreased in the brains of rats with pain and motor deficits following sciatic nerve ligation (Mor et al., 2011) while HSP90ab1, HSPa4, and HSPe1 were reduced after contusion injury in rats (Zhou et al., 2014).

Altogether then, the expression of various chaperones and co-chaperones is altered after CNS and PNS axon damage in either an enhanced or reduced manner. The question is, do these proteins play an active role in the injury or repair processes.

Function of chaperone proteins after PNS and CNS axonal damage

Neuronal survival

Because of the increased expression of clusterin in axotomized motorneurons, Törnqvist et al. (1996) suggested that the chaperone may be involved in the death of damaged neurons. Other studies instead indicate that some chaperone proteins play a role in maintaining survival of damaged neurons. For instance, Benn et al. (2002) found that upregulation and phosphorylation of HSP27 was required for the survival of sensory and motor neurons after sciatic nerve transection. The lab then extended this work both in vivo and in vitro to show that survival of PNS neurons from injured neonatal or adult animals following nerve growth factor (NGF) removal was related to whether DRG cells expressed HSP27. They also demonstrated that overexpression of human HSP27 in neonatal rat sensory and sympathetic neurons significantly increased survival after NGF withdrawal (Lewis et al., 1999). With respect to other chaperone proteins, HSP70 was observed to promote retinal ganglion cell survival and optic nerve regeneration in zebrafish since these processes were enhanced and reduced respectively if the hsp was inhibited (Nagashima et al., 2011). Moreover, exogenous application of HSP70 to the proximal end of transected rat sciatic nerves prevented the death of almost all sensory neurons (Houenou et al., 1996). Other evidence for a role of chaperones in promoting neuronal survival after CNS and PNS injury was demonstrated by Chang et al. (2014) who showed that HSP72 expression in neurons and astrocytes correlated with less apoptosis of these cell types in a rat spinal cord compression model. Also, survival of retinal ganglion cells following optic nerve transection in hamsters correlated with HSP27 expression after remote ischemic pre-conditioning (Liu et al., 2013) while Penas et al. (2011a) showed that a decrease in binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP)/GRP78 correlated with retrograde degeneration of damage peripheral motor neurons. Interestingly, if chaperones themselves are altered by post-translational modification, this could negatively impact neuronal survival as shown by Franco et al. (2013) who found that the presence of nitrated HSP90 in contused rat spinal cord was linked to motor neuron death.

With respect to which molecular mechanism(s) may be involved in chaperone-mediated neuronal survival post-nerve damage, the activation of the p38 kinase was found to be required for induction of HSP25 expression after sciatic nerve axotomy. Here, HSP25 formed a complex with AKT to prevent neuronal cell death (Murashov et al., 2001). Also, nitrated HSP90 induced neuronal death via P2X7 receptor-dependent activation of the Fas pathway (Franco et al., 2013) while HSP27's neuroprotective action was found to be downstream of cytochrome c release from mitochondria and upstream of caspase-3 activation (Benn et al., 2002). Another possible mechanism involved in cell survival post-axotomy may involve endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and the unfolded protein response (UPR), both of which are induced and activated after nerve damage (Penas et al., 2007; Ohri et al., 2011; Fan et al., 2015). If ER stress is activated, a number of chaperone proteins are upregulated such as GRP78/BiP (that co-chaperones with HSP70 or σ1R) and GRP94, an ER homolog of HSP90. These chaperones attempt to correct the stress by mediating proper protein folding and thus prevent cell death through induction of pro-survival factors such as Bcl2. If chaperones are unable to prevent accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins, the UPR is activated to minimize overloading by unfolded proteins. If however the stress is still unmanageable and homeostasis cannot be restored in a timely manner, apoptosis is induced (Fu and Gao, 2014). Enhancement of ER stress components such as CHOP, XBP1, and ATF6 has been observed after spinal cord contusion (Penas et al., 2007; Ohri et al., 2011), L5 spinal nerve ligation (Zhang et al., 2015) and sciatic nerve crush (Mantuano et al., 2011), with BiP enhancement observed in the latter two studies. The hypothesis is that the chaperones are attempting to correct the injurious processes and prevent cell death. However, very few studies have definitively linked chaperones with correcting ER stress and UPR activation after PNS and CNS axotomy. Penas et al. (2011b) have ventured into this area by noting that the balance between BiP and CHOP drives cell fate. As a result, they sought to modulate this ratio in favor of BiP using valproate (VPA). Although it did not augment BiP levels, high doses of VPA in a severe spinal cord contusion model reduced CHOP levels which correlated with reduced oligodendrocyte, myelin and axonal loss and better functional recovery. Of interest, the same lab has implicated chaperones in preventing another cell death process, autophagy, after axotomy. It was noted that autophagy markers such as BECLIN 1, LC3II, and LAMP-1 were enhanced in motor neurons after spinal root avulsion along with downregulation of BiP. The authors concluded that BiP decrease is a signature of the degenerating process, since its overexpression led to an increase in motor neuron survival (Penas et al., 2011b). However, this is correlative and more studies are needed to clearly clarify that the upregulation of chaperone proteins seen after PNS and CNS nerve damage is an attempt to correct ER stress or autophagy-induced cell death.

Axon regeneration

In addition to cell survival, chaperones have been associated with regeneration of damaged PNS and CNS axons. For example, clusterin was found to be important for regrowth of sensory neurons after sciatic nerve transection and crush injury since this process was impaired in clusterin null mice (Wright et al., 2014). Further, exogenous application of the small heat shock protein, αBC, promoted neurite outgrowth of rat retinal cells (Wang et al., 2012). In vivo, the crystallin mediated regeneration of crushed rat optic nerve fibers through reduced activation of RhoA and phosphorylation of cofilin and myosin light chain. Other mechanisms by which chaperones mediate regeneration may involve modulation of axonal and Schwann cell cytoskeleton. Specifically, HSP27 was found to promote axonal outgrowth by possibly promoting assembly of intermediate filament proteins in Schwann cells (Hirata et al., 2003). In addition, Ma et al. (2011) noted that enhanced motor function recovery attributed to HSP27 was likely due to increased motor synapse reinnervation. To expand upon effects on functional recovery, exogenous application of αBC was discovered to promote locomoter recovery following spinal cord contusion injury in mice, with the improvement linked to reduced tissue damage and inflammation (Klopstein et al., 2012).

Myelination

We recently showed that αBC contributes to remyelination in the PNS after sciatic nerve crush in mice (Lim et al., 2017). Specifically, the small HSP appears to modulate the conversion of de-differentiated Schwann cells back to a myelinating phenotype and that this occurs through a neuregulin 1 Type III/AKT/ErbB2 mechanism. A hint that the crystallin may be involved in myelination was demonstrated earlier by D'Antonio et al. (2006) who found a correlation between the expression of the HSP and formation of myelinating Schwann cells during development. αBC is not the only chaperone found to be involved in Schwann cell function after PNS injury. BAG1, which is enhanced in Schwann cells after sciatic nerve crush, was shown to be important for differentiation of myelinating Schwann cells since knockdown of BAG1 with siRNA reduced the number of protein zero positive Schwann cells in culture (Wu et al., 2013).

Neuropathic pain

All of the functions discussed above are beneficial, but chaperones may be involved in promoting injury-related neuropathic pain. The chaperone σ1R, was found to be associated with neuropathic pain after sciatic nerve ligation since use of an antagonist called 4-[2-[[5-methyl-1-(2-naphthalenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl]oxy]ethyl]morpholine) inhibited spinal sensitization and pain hypersensitivity (Romero et al., 2012). In corroboration, Pan et al. (2014) showed that σ1R was involved in pain sensitivity by sensory neurons in a rat sciatic nerve ligation model, since its antagonism with 1-[2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl]-4-methylpiperazine dihydrochloride or N-[2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl]-N-methyl-2-(dimethylamino)ethylamine dihydrobromide, reduced pain through restoration of calcium influx. Further, σ1R−/− mice display reduced central sensitization and diminished hyperalgesic responses after sciatic nerve ligation (de la Puente et al., 2009). These results would suggest that the expression of σ1R would have to be increased or at least maintained from its non-injured level. However, Bangaru et al. (2013) showed that σ1R expression was reduced in DRG cells after sciatic nerve ligation. Whether there is differential expression in DRGs vs. axons after injury needs to be clarified especially knowing that local protein synthesis can occur within PNS axons (Court et al., 2011).

Inflammation

There is a large literature on chaperones and inflammation. However, very little research has been conducted on how these proteins affect the immune response after PNS and CNS nerve injury. Klopstein et al. (2012) showed that αBC reduced inflammation in the mouse spinal cord after contusion injury. On the other hand, Fan et al. (2015) linked GRP78/BiP with necroptosis and ER stress in macrophages/microglia after mouse spinal cord contusion. Considering the beneficial role that the robust immune response plays after PNS axon damage, there is an opportunity to understand what function(s) chaperone proteins play in the protective PNS immune response as opposed to the slow, limited and seemingly detrimental inflammation seen after CNS axotomy.

Altogether, a number of chaperones play various beneficial roles after PNS and CNS injury including promoting neuronal survival, axon regeneration, remyelination, Schwann cell differentiation, and functional recovery. However, others such as σ1R appear to mediate less desirable effects such as neuropathic pain.

Therapeutic strategies that involve chaperones

Because of the many reported beneficial functions of chaperone proteins after CNS and PNS nerve injury, some efforts have been made to harness their protective properties to enhance repair. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) is a ligand-activated transcription factor of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily whose agonist pioglotazone improved functional recovery and reduced motor neuron loss, astrogliosis, and microglial activation after rat spinal contusion injury. This improvement was attributed in part to the augmented expression of HSP27, HSP32, and HSP70 in the cord (McTigue et al., 2007). Using another PPARγ ligand, rosiglitazone, Yi et al. (2008) implicated chaperones in promoting survival of the damaged spinal neurons after brain contusion injury since neuronal survival correlated with enhanced expression of HSP27, HSP70 and HSP32. Along the same lines on neuronal survival, because σ1R agonists possess potent anti-apoptotic abilities, one of its agonists, 2-(4-morpholinethyl)1-phenylcyclohexanecarboxylate, was studied in the context of spinal root avulsion in the rat. Here, a marked increase in motor neuron survival was evident, which correlated with a decrease in astrogliosis and an increase in the σ1R co-chaperone, BiP. However, considering the neuropathic pain-inducing effects of σ1R described in the previous section, one would have to decipher how to achieve the benefits of neuronal survival without developing pathological effects such as pain.

With respect to other therapies involving chaperones, improvement in functional recovery in rats with a contusion spinal cord injury following interferon-beta 1b treatment was found to be related to enhanced HSP70 expression in the cord along with reduced polymorphonuclear leucocyte infiltration, hemorrhage, oedema and necrosis (Sengul et al., 2013). An interesting therapeutic intervention in spinal cord injury experiments has been the use of exercise in injured animals. Keeler et al. (2012) showed that functional recovery improved in animals that had been previously subjected to an exercise regiment. This benefit was associated with increased expression of HSP27 and HSP70 in the spinal cord. In the PNS, a similar effect was seen after chronic constriction of the rat sciatic nerve where exercise training attenuated neuropathic pain and which correlated with reduced inflammation and enhanced HSP27 expression (Chen et al., 2012).

Another chaperone-inducing agent that has been used as a therapy after nerve transection has been BRX-220 (bimoclomal analog). BMX-220 is a hydroxylamine derivative that promotes cell survival through increased expression of HSP70 and HSP90 (Vígh et al., 1997). In the CNS, BRX-220 improved motor neuron survival while enhancing HSP70 and HSP90 in the damaged spinal cord (Kalmar et al., 2002, 2003). Follow up studies in the PNS, showed that BRX-220 reduced pain sensations that correlated with enhanced HSP70 expression in sensory DRG neurons (Kalmar et al., 2003).

Finally, immunophilins are a group of proteins that serve as receptors for the immunosuppressant drugs cyclosporin A and FK506. Systemic administration of FK506 dose-dependently increased the rate of axonal regeneration and functional recovery in rats following a sciatic nerve crush injury. This was attributed to binding of FK506 to the immunophilins FKBP-12. However, it is possible that the beneficial function was through chaperone proteins—FK506 can also bind FKBP-52/FKBP-59, which has been identified as a heat shock protein (HSP56) and shown to enhance expression of HSP70 (Gold, 1997; Gold et al., 1997).

Conclusion

Numerous studies over the past three decades have shown that the expression of chaperone proteins are not only altered following nerve damage to CNS and PNS neurons but that these proteins play an active role in the repair processes and in mediating some of the pathological events. Ongoing and future studies will have to consider how to harness the beneficial properties while reducing the injurious functions to enhance CNS and PNS recovery.

Author contributions

SO wrote the manuscript with content discussion, editing, and figures design by AF and EL.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a seed grant from the University of Calgary University Research Grants Committee, bridge funding from Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions (AIHS) and the University of Calgary Cumming School of Medicine and, a Hotchkiss Brain Institute Axon Biology and Regeneration Theme studentship support grant. EL was supported by a studentship from AIHS.

References

- Bangaru M. L., Weihrauch D., Tang Q. B., Zoga V., Hogan Q., Wu H. E. (2013). Sigma-1 receptor expression in sensory neurons and the effect of painful peripheral nerve injury. Mol. Pain 9:47. 10.1186/1744-8069-9-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benn S. C., Perrelet D., Kato A. C., Scholz J., Decosterd I., Mannion R. J., et al. (2002). Hsp27 upregulation and phosphorylation is required for injured sensory and motor neuron survival. Neuron 36, 45–56. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00941-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnard A. S., Chan P., Fontaine M. (1997). Expression of clusterin and C4 mRNA during rat peripheral nerve regeneration. Immunopharmacology 38, 81–86. 10.1016/S0162-3109(97)00073-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J., Fleshner M. (2003). Role of extracellular HSP72 in acute stress-induced potentiation of innate immunity in active rats. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 94, 43–52. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00681.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauley K. A., Sherman T. G., Ford-Holevinski T., Agranoff B. W. (1986). Rapid expression of novel proteins in goldfish retina following optic nerve crush. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 138, 1177–1183. 10.1016/S0006-291X(86)80406-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. K., Chou W., Lin H. J., Huang Y. C., Tang L. Y., Lin M. T., et al. (2014). Exercise preconditioning protects against spinal cord injury in rats by upregulating neuronal and astroglial heat shock protein 72. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 19018–19036. 10.3390/ijms151019018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. W., Li Y. T., Chen Y. C., Li Z. Y., Hung C. H. (2012). Exercise training attenuates neuropathic pain and cytokine expression after chronic constriction injury of rat sciatic nerve. Anesth. Analg. 114, 1330–1337. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824c4ed4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidlow G., Wood J. P., Casson R. J. (2014). Expression of inducible heat shock proteins Hsp27 and Hsp70 in the visual pathway of rats subjected to various models of retinal ganglion cell injury. PLoS ONE 9:e114838. 10.1371/journal.pone.0114838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cízková D., Lukácová N., Marsala M., Kafka J., Lukác I., Jergová S., et al. (2005). Experimental cauda equina compression induces HSP70 synthesis in dog. Physiol. Res. 54, 349–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colognato H., Ffrench-Constant C., Feltri M. L. (2005). Human diseases reveal novel roles for neural laminins. Trends Neurosci. 28, 480–486. 10.1016/j.tins.2005.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan M., Mannion R. J., Kendall G., Lewis S. E., Campagna J. A., Coggeshall R. E., et al. (1998). Heat shock protein 27: developmental regulation and expression after peripheral nerve injury. J. Neurosci. 18, 5891–5900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court F. A., Midha R., Cisterna B. A., Grochmal J., Shakhbazau A., Hendriks W. T., et al. (2011). Morphological evidence for a transport of ribosomes from Schwann cells to regenerating axons. Glia 59, 1529–1539. 10.1002/glia.21196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Antonio M., Michalovich D., Paterson M., Droggiti A., Woodhoo A., Mirsky R., et al. (2006). Gene profiling and bioinformatic analysis of Schwann cell embryonic development and myelination. Glia 53, 501–515. 10.1002/glia.20309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David S., Ousman S. S. (2002). Recruiting the immune response to promote axon regeneration in the injured spinal cord. Neuroscientist 8, 33–41. 10.1177/107385840200800108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Puente B., Nadal X., Portillo-Salido E., Sánchez-Arroyos R., Ovalle S., Palacios G., et al. (2009). Sigma-1 receptors regulate activity-induced spinal sensitization and neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury. Pain 145, 294–303. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derham B. K., Harding J. J. (1999). Alpha-crystallin as a molecular chaperone. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 18, 463–509. 10.1016/S1350-9462(98)00030-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edbladh M., Ekström P. A., Edström A. (1994). Retrograde axonal transport of locally synthesized proteins, e.g., actin and heat shock protein 70, in regenerating adult frog sciatic sensory axons. J. Neurosci. Res. 38, 424–432. 10.1002/jnr.490380408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H., Tang H. B., Kang J., Shan L., Song H., Zhu K., et al. (2015). Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the necroptosis of microglia/macrophages after spinal cord injury. Neuroscience 311, 362–373. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.10.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco M. C., Ye Y., Refakis C. A., Feldman J. L., Stokes A. L., Basso M., et al. (2013). Nitration of Hsp90 induces cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E1102–E1111. 10.1073/pnas.1215177110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X. L., Gao D. S. (2014). Endoplasmic reticulum proteins quality control and the unfolded protein response: the regulative mechanism of organisms against stress injuries. Biofactors 40, 569–585. 10.1002/biof.1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet A. D., Popovich P. G., Ramer M. S. (2011). Wallerian degeneration: gaining perspective on inflammatory events after peripheral nerve injury. J. Neuroinflammation 8:110. 10.1186/1742-2094-8-110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold B. G. (1997). FK506 and the role of immunophilins in nerve regeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 15, 285–306. 10.1007/BF02740664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold B. G., Zeleny-Pooley M., Wang M. S., Chaturvedi P., Armistead D. M. (1997). A nonimmunosuppressant FKBP-12 ligand increases nerve regeneration. Exp. Neurol. 147, 269–278. 10.1006/exnr.1997.6630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gower D. J., Hollman C., Lee K. S., Tytell M. (1989). Spinal cord injury and the stress protein response. J. Neurosurg. 70, 605–611. 10.3171/jns.1989.70.4.0605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall S. (2005). The response to injury in the peripheral nervous system. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 87, 1309–1319. 10.1302/0301-620X.87B10.16700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb M. O., Myers T. L., Clarke D. B. (2006). Enhanced expression of heat shock protein 27 is correlated with axonal regeneration in mature retinal ganglion cells. Brain Res. 1073–1074, 146–150. 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata K., He J., Hirakawa Y., Liu W., Wang S., Kawabuchi M. (2003). HSP27 is markedly induced in Schwann cell columns and associated regenerating axons. Glia 42, 1–11. 10.1002/glia.10105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins D. A., Plumier J. C., Currie R. W. (1998). Induction of the 27-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp27) in the rat medulla oblongata after vagus nerve injury. Exp. Neurol. 153, 173–183. 10.1006/exnr.1998.6870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X. E., Lundmark K., Dahlström A. B. (1998). Cellular reactions to axotomy in rat superior cervical ganglia includes apoptotic cell death. J. Neurocytol. 27, 441–451. 10.1023/A:1006988528655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houenou L. J., Li L., Lei M., Kent C. R., Tytell M. (1996). Exogenous heat shock cognate protein Hsc 70 prevents axotomy-induced death of spinal sensory neurons. Cell Stress Chaperones 1, 161–166. 10.1379/1466-1268(1996)001 <0161:EHSCPH>2.3.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima K., Harada F., Hanada K., Nozawa-Inoue K., Aita M., Atsumi Y., et al. (2003). Temporal expression of immunoreactivity for heat shock protein 25 (Hsp25) in the rat periodontal ligament following transection of the inferior alveolar nerve. Brain Res. 979, 146–152. 10.1016/S0006-8993(03)02889-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmar B., Burnstock G., Vrbová G., Urbanics R., Csermely P., Greensmith L. (2002). Upregulation of heat shock proteins rescues motoneurones from axotomy-induced cell death in neonatal rats. Exp. Neurol. 176, 87–97. 10.1006/exnr.2002.7945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmar B., Greensmith L., Malcangio M., McMahon S. B., Csermely P., Burnstock G. (2003). The effect of treatment with BRX-220, a co-inducer of heat shock proteins, on sensory fibers of the rat following peripheral nerve injury. Exp. Neurol. 184, 636–647. 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00343-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeler B. E., Liu G., Siegfried R. N., Zhukareva V., Murray M., Houlé J. D. (2012). Acute and prolonged hindlimb exercise elicits different gene expression in motoneurons than sensory neurons after spinal cord injury. Brain Res. 1438, 8–21. 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. S., Lee S. J., Park S. Y., Yoo H. J., Kim S. H., Kim K. J., et al. (2001). Differentially expressed genes in rat dorsal root ganglia following peripheral nerve injury. Neuroreport 12, 3401–3405. 10.1097/00001756-200110290-00050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klass M. G., Gavrikov V., Krishnamoorthy M., Csete M. (2008). Heat shock proteins, endothelin, and peripheral neuronal injury. Neurosci. Lett. 433, 188–193. 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimaschewski L., Obermüller N., Witzgall R. (2001). Regulation of clusterin expression following spinal cord injury. Cell Tissue Res. 306, 209–216. 10.1007/s004410100431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klopstein A., Santos-Nogueira E., Francos-Quijorna I., Redensek A., David S., Navarro X., et al. (2012). Beneficial effects of αB-crystallin in spinal cord contusion injury. J. Neurosci. 32, 14478–14488. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0923-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger-Naug A. M., Emsley J. G., Myers T. L., Currie R. W., Clarke D. B. (2002). Injury to retinal ganglion cells induces expression of the small heat shock protein Hsp27 in the rat visual system. Neuroscience 110, 653–665. 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00453-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampert-Etchells M., McNeill T. H., Laping N. J., Zarow C., Finch C. E., May P. C. (1991). Sulfated glycoprotein-2 is increased in rat hippocampus following entorhinal cortex lesioning. Brain Res. 563, 101–106. 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91520-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S. E., Mannion R. J., White F. A., Coggeshall R. E., Beggs S., Costigan M., et al. (1999). A role for HSP27 in sensory neuron survival. J. Neurosci. 19, 8945–8953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim E.-M. F., Nakanishi S. T., Hoghooghi V., Eaton S. E. A., Palmer A. L., Frederick A., et al. (2017). AlphaB-crystallin regulates remyelination following peripheral nerve injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.1612136114. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. M., Yang L. H., Yang Y. J. (1995). Schwann cell properties: 3. C-fos expression, bFGF production, phagocytosis and proliferation during Wallerian degeneration. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 54, 487–496. 10.1097/00005072-199507000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Persson J. K., Svensson M., Aldskogius H. (1998). Glial cell responses, complement, and clusterin in the central nervous system following dorsal root transection. Glia 23, 221–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Svensson M., Aldskogius H. (1999). Clusterin upregulation following rubrospinal tract lesion in the adult rat. Exp. Neurol. 157, 69–76. 10.1006/exnr.1999.7046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Törnqvist E., Mattsson P., Eriksson N. P., Persson J. K., Morgan B. P., et al. (1995). Complement and clusterin in the spinal cord dorsal horn and gracile nucleus following sciatic nerve injury in the adult rat. Neuroscience 68, 167–179. 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00103-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Sha O., Cho E. Y. (2013). Remote ischemic postconditioning promotes the survival of retinal ganglion cells after optic nerve injury. J. Mol. Neurosci. 51, 639–646. 10.1007/s12031-013-0036-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C. H., Omura T., Cobos E. J., Latrémolière A., Ghasemlou N., Brenner G. J., et al. (2011). Accelerating axonal growth promotes motor recovery after peripheral nerve injury in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4332–4347. 10.1172/JCI58675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madduri S., Gander B. (2010). Schwann cell delivery of neurotrophic factors for peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 15, 93–103. 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2010.00257.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantuano E., Henry K., Yamauchi T., Hiramatsu N., Yamauchi K., Orita S., et al. (2011). The unfolded protein response is a major mechanism by which LRP1 regulates Schwann cell survival after injury. J. Neurosci. 31, 13376–13385. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2850-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mautes A. E., Bergeron M., Sharp F. R., Panter S. S., Weinzierl M., Guenther K., et al. (2000). Sustained induction of heme oxygenase-1 in the traumatized spinal cord. Exp. Neurol. 166, 254–265. 10.1006/exnr.2000.7520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mautes A. E., Noble L. J. (2000). Co-induction of HSP70 and heme oxygenase-1 in macrophages and glia after spinal cord contusion in the rat. Brain Res. 883, 233–237. 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02846-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTigue D. M., Tripathi R., Wei P., Lash A. T. (2007). The PPAR gamma agonist Pioglitazone improves anatomical and locomotor recovery after rodent spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 205, 396–406. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor D., Bembrick A. L., Austin P. J., Keay K. A. (2011). Evidence for cellular injury in the midbrain of rats following chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 41, 158–169. 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashov A. K., Haq I. U., Hill C., Park E., Smith M., Wang X., et al. (2001). Crosstalk between p38, Hsp25 and Akt in spinal motor neurons after sciatic nerve injury. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 93, 199–208. 10.1016/S0169-328X(01)00212-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima M., Fujikawa C., Mawatari K., Mori Y., Kato S. (2011). HSP70, the earliest-induced gene in the zebrafish retina during optic nerve regeneration: its role in cell survival. Neurochem. Int. 58, 888–895. 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New G. A., Hendrickson B. R., Jones K. J. (1989). Induction of heat shock protein 70 mRNA in adult hamster facial nuclear groups following axotomy of the facial nerve. Metab. Brain Dis. 4, 273–279. 10.1007/BF00999773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nodari A., Previtali S. C., Dati G., Occhi S., Court F. A., Colombelli C., et al. (2008). α6beta4 integrin and dystroglycan cooperate to stabilize the myelin sheath. J. Neurosci. 28, 6714–6719. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0326-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohri S. S., Maddie M. A., Zhao Y. M., Qiu M. S., Hetman M., Whittemore S. R. (2011). Attenuating the endoplasmic reticulum stress response improves functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Glia 59, 1489–1502. 10.1002/glia.21191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ousman S. S., Tomooka B. H., van Noort J. M., Wawrousek E. F., O'Connor K. C., Hafler D. A., et al. (2007). Protective and therapeutic role for αB-crystallin in autoimmune demyelination. Nature 448, 474–479. 10.1038/nature05935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan B., Guo Y., Kwok W. M., Hogan Q., Wu H. E. (2014). Sigma-1 receptor antagonism restores injury-induced decrease of voltage-gated Ca2+ current in sensory neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 350, 290–300. 10.1124/jpet.114.214320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parcellier A., Schmitt E., Brunet M., Hammann A., Solary E., Garrido C. (2005). Small heat shock proteins HSP27 and alphaB-crystallin: cytoprotective and oncogenic functions. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7, 404–413. 10.1089/ars.2005.7.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. W., Yi J. H., Miranpuri G., Satriotomo I., Bowen K., Resnick D. K., et al. (2007). Thiazolidinedione class of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists prevents neuronal damage, motor dysfunction, myelin loss, neuropathic pain, and inflammation after spinal cord injury in adult rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 320, 1002–1012. 10.1124/jpet.106.113472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penas C., Font-Nieves M., Fores J., Petegnief V., Planas A., Navarro X., et al. (2011a). Autophagy, and BiP level decrease are early key events in retrograde degeneration of motoneurons. Cell Death Differ. 18, 1617–1627. 10.1038/cdd.2011.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penas C., Guzman M. S., Verdu E., Fores J., Navarro X., Casas C. (2007). Spinal cord injury induces endoplasmic reticulum stress with different cell-type dependent response. J. Neurochem. 102, 1242–1255. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04671.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penas C., Verdu E., Asensio-Pinilla E., Guzman-Lenis M. S., Herrando-Grabulosa M., Navarro X., et al. (2011b). Valproate reduces CHOP levels and preserves oligodendrocytes and axons after spinal cord injury. Neuroscience 178, 33–44. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy S. J., La Marca F., Park P. (2008). The role of heat shock proteins in spinal cord injury. Neurosurg. Focus 25:E4. 10.3171/FOC.2008.25.11.E4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero L., Zamanillo D., Nadal X., Sanchez-Arroyos R., Rivera-Arconada I., Dordal A., et al. (2012). Pharmacological properties of S1RA, a new sigma-1 receptor antagonist that inhibits neuropathic pain and activity-induced spinal sensitization. Br. J. Pharmacol. 166, 2289–2306. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01942.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai M., Aoki M., Abe K., Sadahiro M., Tabayashi K. (1997). Selective motor neuron death and heat shock protein induction after spinal cord ischemia in rabbits. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 113, 159–164. 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70411-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengul G., Coban M. K., Cakir M., Coskun S., Aksoy H., Hacimuftuoglu A., et al. (2013). Neuroprotective effect of acute interferon-beta 1B treatment after spinal cord injury. Turk. Neurosurg. 23, 45–49. 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.6651-12.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma H. S., Gordh T., Wiklund L., Mohanty S., Sjoquist P. O. (2006). Spinal cord injury induced heat shock protein expression is reduced by an antioxidant compound H-290/51. An experimental study using light and electron microscopy in the rat. J. Neural Transm. 113, 521–536. 10.1007/s00702-005-0405-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma H. S., Muresanu D. F., Lafuente J. V., Sjoquist P. O., Patnaik R., Sharma A. (2015). Nanoparticles exacerbate both ubiquitin and heat shock protein expressions in spinal cord injury: neuroprotective effects of the proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib and the antioxidant compound H-290/51. Mol. Neurobiol. 52, 882–898. 10.1007/s12035-015-9297-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G., Cechvala C., Resnick D. K., Dempsey R. J., Rao V. L. (2001). GeneChip analysis after acute spinal cord injury in rat. J. Neurochem. 79, 804–815. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00626.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson M., Liu L., Mattsson P., Morgan B. P., Aldskogius H. (1995). Evidence for activation of the terminal pathway of complement and upregulation of sulfated glycoprotein (SGP)-2 in the hypoglossal nucleus following peripheral nerve injury. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 24, 53–68. 10.1007/BF03160112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana T., Noguchi K., Ruda M. A. (2002). Analysis of gene expression following spinal cord injury in rat using complementary DNA microarray. Neurosci. Lett. 327, 133–137. 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00375-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Törnqvist E., Liu L., Aldskogius H., Holst H. V., Svensson M. (1996). Complement and clusterin in the injured nervous system. Neurobiol. Aging 17, 695–705. 10.1016/0197-4580(96)00120-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi H., Ikeda K., Sugimoto N., Tomita K. (2009). Local application of olprinone for promotion of peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Orthop. Sci. 14, 801–810. 10.1007/s00776-009-1398-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vígh L., Literáti P. N., Horváth I., Török Z., Balogh G., Glatz A., et al. (1997). Bimoclomol: a nontoxic, hydroxylamine derivative with stress protein-inducing activity and cytoprotective effects. Nat. Med. 3, 1150–1154. 10.1038/nm1097-1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinit S., Darlot F., Aoulaïche H., Boulenguez P., Kastner A. (2011). Distinct expression of c-Jun and HSP27 in axotomized and spared bulbospinal neurons after cervical spinal cord injury. J. Mol. Neurosci. 45, 119–133. 10.1007/s12031-010-9481-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller A. (1850). Experiments on the section of the glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves of the frog, and observations of the alterations produced thereby in the structure of their primitive fibres. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 140, 423–429. 10.1098/rstl.1850.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. H., Wang D. W., Wu N., Wang Y., Yin Z. Q. (2012). alpha-Crystallin promotes rat axonal regeneration through regulation of RhoA/rock/cofilin/MLC signaling pathways. J. Mol. Neurosci. 46, 138–144. 10.1007/s12031-011-9537-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis D., Li K. W., Zheng J. Q., Chang J. H., Smit A. B., Kelly T., et al. (2005). Differential transport and local translation of cytoskeletal, injury-response, and neurodegeneration protein mRNAs in axons. J. Neurosci. 25, 778–791. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4235-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright M. C., Mi R., Connor E., Reed N., Vyas A., Alspalter M., et al. (2014). Novel roles for osteopontin and clusterin in peripheral motor and sensory axon regeneration. J. Neurosci. 34, 1689–1700. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3822-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Liu Y., Zhou Y., Long L., Cheng X., Ji L., et al. (2013). Changes in the BAG1 expression of Schwann cells after sciatic nerve crush. J. Mol. Neurosci. 49, 512–522. 10.1007/s12031-012-9910-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D., Cui S., Sun Y., Bao G., Li W., Liu W., et al. (2011). Overexpression of glucose-regulated protein 94 after spinal cord injury in rats. J. Neurol. Sci. 309, 141–147. 10.1016/j.jns.2011.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi J. H., Park S. W., Brooks N., Lang B. T., Vemuganti R. (2008). PPARgamma agonist rosiglitazone is neuroprotective after traumatic brain injury via anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative mechanisms. Brain Res. 1244, 164–172. 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.09.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang E., Yi M. H., Shin N., Baek H., Kim S., Kim E., et al. (2015). Endoplasmic reticulum stress impairment in the spinal dorsal horn of a neuropathic pain model. Sci. Rep. 5:11555. 10.1038/srep11555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Hu W., Meng B., Tang T. (2010). PPARgamma agonist rosiglitazone is neuroprotective after traumatic spinal cord injury via anti-inflammatory in adult rats. Neurol. Res. 32, 852–859. 10.1179/016164110X12556180206112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Xu L., Song X., Ding L., Chen J., Wang C., et al. (2014). The potential role of heat shock proteins in acute spinal cord injury. Eur. Spine J. 23, 1480–1490. 10.1007/s00586-014-3214-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zochodne D. W. (2008). Neurobiology of Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zoli M., Ferraguti F., Zini I., Bettuzzi S., Agnati L. F. (1993). Increases in sulphated glycoprotein-2 mRNA levels in the rat brain after transient forebrain ischemia or partial mesodiencephalic hemitransection. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 18, 163–177. 10.1016/0169-328X(93)90185-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]