Abstract

Objective

To assess changes in incidence, diagnostic procedures, comorbidity profiles, length of hospital stay (LOHS), economic costs and in-hospital mortality (IHM) associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

Methods

We identified patients hospitalised with IPF in Spain from 2004 to 2013. Data were collected from the National Hospital Discharge Database.

Results

The study population comprised 22 214 patients. Overall crude incidence increased from 3.82 to 6.98 admissions per 100 000 inhabitants from 2004 to 2013 (p<0.05). The percentage of lung biopsies decreased significantly from 10.68% in 2004 to 9.04% in 2013 (p<0.05). The percentage of patients with a Charlson comorbidity index ≥2 was 15.14% in 2004, increasing to 26.95% in 2013 (p<0.05). IHM decreased from 14.77% in 2004 to 13.72% in 2013 (adjusted OR 0.98; 95% CI 0.97 to 0.99). Mean LOHS was 11.87±11.18 days in 2004, decreasing to 10.20±11.12 days in 2013 (p<0.05). The mean cost per patient increased from €4838.51 in 2004 to €5410.90 in 2013 (p<0.05).

Conclusions

The frequency of hospital admissions for IPF increased during the study period, as did healthcare costs. However, IHM and LOHS decreased.

Keywords: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, hospitalization, length of hospital stay, cost, in-hospital mortality

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study provides robust evidence that management of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) improved in Spain during 2004–2013.

The Spanish National Hospital Database is managed by the National Public Health System and covers almost all hospital admissions in Spain.

The study is limited by the use of administrative data to identify patients hospitalised for IPF.

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a specific form of chronic, progressive, fibrosing interstitial pneumonia. Its aetiology is unknown and it is seen mainly in older adults. IPF affects the lungs, and histology and radiology findings indicate that its pattern is similar to that of usual interstitial pneumonia.1 It is an uncommon disease with an unfavourable clinical course. Mortality is high, and prognosis is similar to that of many malignant diseases. Median survival after diagnosis is 2.5–5 years. Nevertheless, the relative rarity of IPF means that published data about its epidemiology are scarce. Consequently, it is difficult to conduct studies with an adequate sample size.2 3

Hospital admissions for IPF are one of the best sources of information on trends and prognosis, although the few data that are available are inconclusive. Agabiti et al4 analysed data over 5 years (2005–2009) from hospitals in Lazio, central-southern Italy, and found an estimated incidence of IPF of 9.3 per 100 000 inhabitants (95% CI 9.2 to 9.4) and a prevalence of 31.6 per 100 000 inhabitants (95% CI 30.9 to 32.2). In Greece, Karakatsani et al5 reported an incidence of 0.93 per 100 000/year and a prevalence of 3.38 per 100 000/year, which differs somewhat from the Italian results. In Spain, the latest data from the Spanish Interstitial Lung Diseases Group were collected in 2004 using a standardised questionnaire that was sent to hospitals along with recommendations for classification and diagnosis.6 The questions were designed to assess the investigations carried out to establish the diagnosis. The authors found a global incidence, for all the interstitial lung diseases, of 7.6 per 100 000 inhabitants per year and specified that IPF accounted for 38.6% of cases. In the UK, Gribbin et al7 reported a crude incidence rate for IPF of 4.6 per 100 000 inhabitants (95% CI 4.3 to 4.9) in 2006. Navaratnam et al8 subsequently obtained an incidence rate of 7.44 per 100 000 person-years (95% CI 7.12 to 7.77); therefore, the incidence appears to be rising by 5% per year. One of the most recent studies on the epidemiology of IPF in Europe was conducted in Denmark, where Hyldgaard et al9 collected data over 6 years in a single hospital and analysed various interstitial lung diseases. The authors reported an incidence of IPF of 1.3 per 100 000 person-years.

Mixed results have been reported from other parts of the world. Thus, for example, in the USA, depending on the criteria used, incidence has been estimated at 8.8–17.4 cases per 100 000 person-years.10 11 In Japan, Natsuizaka et al12 recorded an incidence of 2.23 per 100 000 inhabitants and a prevalence of 10 per 100 000 person-years.

The data reported show that results vary between countries. It is difficult to account for these differences, although it seems that they are due to the heterogeneity of the research methodologies applied. Furthermore, the studies used different diagnostic criteria and definitions of disease. International studies comparing admissions to hospital and outcomes for patients with IPF could provide a clearer picture of national patterns and help in healthcare planning. Discharge databases are an excellent instrument that makes it possible to perform a national epidemiology study of hospitalisations for IPF.

In the present study, we analysed discharge data collected in Spain during 2004–2013. The analysis enabled us to evaluate changes in the diagnosis, comorbidity, length of hospital stay (LOHS), costs and in-hospital mortality (IHM) of patients hospitalised with IPF in Spain over 10 years, as well as changes in the incidence of this disease during the study period.

Methods

We performed a retrospective, descriptive, epidemiological study using data from the Spanish National Hospital Database (CMBD, Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos). The CMBD includes all public and private hospital data and covers >95% of all hospital discharges.13 The CMBD database is managed by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality and includes data on patient variables (sex and date of birth), date of admission, date of discharge, discharge destination (home, deceased or other health/social institution), and as many as 14 discharge diagnoses and 20 procedures administered during hospitalisation. The Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality sets recording standards and performs periodic audits.13

We selected all patients hospitalised for IPF (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code 516.3) in any diagnostic field during 2004–2013. The annual incidence was calculated by dividing the number of cases per year by the corresponding number of people in that population group according to data from the National Institute of Statistics as on 31 December each year.14 Incidence was expressed per 100 000 inhabitants. IHM, LOHS and costs were also calculated for each year studied. Costs were calculated using diagnosis-related groups for the disease. Diagnosis-related groups are medical-cost entities covering a set of diseases that are managed using similar resources.15 All costs were adjusted for inflation during the study period. Clinical characteristics included information on overall comorbidity at hospitalisation, which was classified using the Charlson comorbidity index.16 The index covers 17 disease categories that are totalled to obtain an overall score for each patient. We divided patients into three categories: 0 (no disease), 1 (one disease) and 2 (two or more diseases).

We specifically identified the following procedures: CT pulmonary (ICD-9-CM code 87.41) and lung biopsy (ICD-9-CM codes 33.20, 33.24, 33.26, 33.27 and 33.28).

We analysed the use of ventilatory support during admissions for IPF. Use of non-invasive ventilation and invasive mechanical ventilation was determined based on procedure codes 93.90 and 96.04, respectively. We also identified the percentage of patients undergoing lung transplant (ICD-9-CM codes 33.50, 33.51, 33.52 and 33.56).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean±SD. Qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons were performed using the χ2 test, Fisher's exact test, t-test or analysis of variance, as appropriate. The multivariate analysis of trends in incidence and IHM of IPF was conducted using Poisson regression models for incidence and logistic regression models for IHM after adjusting for age, sex and other covariates. Interactions between the independent variables in the regression models were investigated. Estimates were made using STATA V.10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA), and statistical significance was set at α<0.05 (two-tailed).

Joinpoint log-linear regression was used to identify the years in which changes in trends occurred in the rates for admissions for IPF and to estimate the annual percentage change in each of the periods delimited by the points of change. The first stage in the analysis was to assess the minimum number of joinpoints before testing whether the inclusion of one or more joinpoints was statistically significant.17 In the final model, each joinpoint indicated a significant change in the trend, and the annual percentage change was obtained in each of the segments delimited by the joinpoints using the weighted least squares method. The software was the Joinpoint Regression Program, V.4.0.4.18

Data confidentiality was maintained at all times according to current Spanish legislation. Patient identifiers were deleted before the database was provided to the authors in order to ensure confidentiality. It is not possible to identify patients in the present manuscript or in the database. Consequently, as the data were anonymous and mandatory, informed consent was not necessary. The Spanish Ministry of Health approved the protocol and provided us with the anonymous database.

Results

We identified a total of 22 214 discharges (12 739 men and 9475 women) admitted for IPF as the primary or secondary diagnosis. Table 1 shows the incidence and the characteristics of patients with IPF in our study.

Table 1.

Incidence and characteristics of patients discharged with a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

| Year | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%)* | |||||||||||

| Male | 909 (55.49) | 919 (54.7) | 990 (56.9) | 1039 (55.06) | 1043 (55.48) | 1231 (57.58) | 1378 (56.43) | 1501 (56.43) | 1756 (60.59) | 1973 (60.69) | 12 739 (57.35) |

| Female | 729 (44.51) | 761 (45.3) | 750 (43.1) | 848 (44.94) | 837 (44.52) | 907 (42.42) | 1064 (43.57) | 1159 (43.57) | 1142 (39.41) | 1278 (39.31) | 9475 (42.65) |

| Age, years* | |||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 72.16 (11.56) | 71.34 (12.85) | 70.74 (13.25) | 72.67 (12.24) | 72.49 (12.46) | 73.15 (12.44) | 73.52 (12.2) | 73.87 (12.25) | 74.04 (11.71) | 74.62 (11.81) | 73.11 (12.28) |

| Age groups, n (%)* | |||||||||||

| 0–49 years | 80 (4.88) | 102 (6.07) | 117 (6.72) | 99 (5.25) | 98 (5.21) | 102 (4.77) | 103 (4.22) | 105 (3.95) | 108 (3.73) | 119 (3.66) | 1033 (4.65) |

| 50–64 years | 220 (13.43) | 301 (17.92) | 295 (16.95) | 287 (15.21) | 285 (15.16) | 315 (14.73) | 352 (14.41) | 391 (14.7) | 466 (16.08) | 451 (13.87) | 3363 (15.14) |

| 65–79 years | 916 (55.92) | 804 (47.86) | 908 (52.18) | 928 (49.18) | 931 (49.52) | 1007 (47.1) | 1182 (48.4) | 1235 (46.43) | 1254 (43.27) | 1435(44.14) | 10 600 (47.72) |

| ≥80 years | 422 (25.76) | 473 (28.15) | 420 (24.14) | 573 (30.37) | 566 (30.11) | 714 (33.4) | 805 (32.96) | 929 (34.92) | 1070 (36.92) | 1246 (38.33) | 7218 (32.49) |

| Charlson index, n (%)* | |||||||||||

| 0 | 807 (49.27) | 872 (51.9) | 861 (49.48) | 883 (46.79) | 824 (43.83) | 912 (42.66) | 977 (40.01) | 1079 (40.56) | 1103 (38.06) | 1157 (35.59) | 9475 (42.65) |

| 1 | 583 (35.59) | 565 (33.63) | 619 (35.57) | 641 (33.97) | 678 (36.06) | 759 (35.5) | 899 (36.81) | 991 (37.26) | 1060 (36.58) | 1218 (37.47) | 8013 (36.07) |

| ≥2 | 248 (15.14) | 243 (14.46) | 260 (14.94) | 363 (19.24) | 378 (20.11) | 467 (21.84) | 566 (23.18) | 590 (22.18) | 735 (25.36) | 876 (26.95) | 4726 (21.27) |

| Lung transplant* | |||||||||||

| No | 1624 (99.15) | 1659 (98.75) | 1716 (98.62) | 1874 (99.31) | 1861 (98.99) | 2119 (99.11) | 2433 (99.63) | 2639 (99.21) | 2870 (99.03) | 3212 (98.8) | 22 007 (99.07) |

| Yes | 14 (0.85) | 21 (1.25) | 24 (1.38) | 13 (0.69) | 19 (1.01) | 19 (0.89) | 9 (0.37) | 21 (0.79) | 28 (0.97) | 39 (1.2) | 207 (0.93) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation, n (%) | |||||||||||

| No | 1600 (97.68) | 1625 (96.73) | 1689 (97.07) | 1846 (97.83) | 1832 (97.45) | 2086 (97.57) | 2403 (98.4) | 2592 (97.44) | 2830 (97.65) | 3179 (97.79) | 21 682 (97.61) |

| Yes | 38 (2.32) | 55 (3.27) | 51 (2.93) | 41 (2.17) | 48 (2.55) | 52 (2.43) | 39 (1.6) | 68 (2.56) | 68 (2.35) | 72 (2.21) | 532 (2.39) |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation, n (%)* | |||||||||||

| No | 1613 (98.47) | 1647 (98.04) | 1711 (98.33) | 1838 (97.4) | 1838 (97.77) | 2080 (97.29) | 2349 (96.19) | 2566 (96.47) | 2772 (95.65) | 3096 (95.23) | 21 510 (96.83) |

| Yes | 25 (1.53) | 33 (1.96) | 29 (1.67) | 49 (2.6) | 42 (2.23) | 58 (2.71) | 93 (3.81) | 94 (3.53) | 126 (4.35) | 155 (4.77) | 704 (3.17) |

| Thoracic CT, n (%) | |||||||||||

| No | 1229 (75.03) | 1263 (75.18) | 1335 (76.72) | 1441 (76.36) | 1398 (74.36) | 1609 (75.26) | 1851 (75.8) | 1993 (74.92) | 2170 (74.88) | 2424 (74.56) | 16 713 (75.24) |

| Yes | 409 (24.97) | 417 (24.82) | 405 (23.28) | 446 (23.64) | 482 (25.64) | 529 (24.74) | 591 (24.2) | 667 (25.08) | 728 (25.12) | 827 (25.44) | 5501 (24.76) |

| Pulmonary biopsy, n(%)* | |||||||||||

| No | 1463 (89.32) | 1501 (89.35) | 1533 (88.1) | 1708 (90.51) | 1704 (90.64) | 1935 (90.51) | 2237 (91.61) | 2429 (91.32) | 2654 (91.58) | 2957 (90.96) | 20 121 (90.58) |

| Yes | 175 (10.68) | 179 (10.65) | 207 (11.9) | 179 (9.49) | 176 (9.36) | 203 (9.49) | 205 (8.39) | 231 (8.68) | 244 (8.42) | 294 (9.04) | 2093 (9.42) |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | |||||||||||

| No | 1396 (85.23) | 1415 (84.23) | 1515 (87.07) | 1612 (85.43) | 1602 (85.21) | 1849 (86.48) | 2117 (86.69) | 2268 (85.26) | 2485 (85.75) | 2805 (86.28) | 19 064 (85.82) |

| Yes | 242 (14.77) | 265 (15.77) | 225 (12.93) | 275 (14.57) | 278 (14.79) | 289 (13.52) | 325 (13.31) | 392 (14.74) | 413 (14.25) | 446 (13.72) | 3150 (14.18) |

| Length of stay, days* | |||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 11.87 (11.18) | 12.11 (11.77) | 11.64 (11.7) | 11.15 (10.56) | 11.33 (12.54) | 10.81 (11.81) | 10.4 (9.59) | 10.5 (10.64) | 10.38 (12.31) | 10.2 (11.12) | 10.9 (11.34) |

| Cost in €* | |||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 4838.51 (5692.3) | 5199.7 (7525.26) | 5055.8 (6285.74) | 4631.99 (4175.69) | 5330.68 (5949.12) | 5551.34 (6490.03) | 4901.52 (6854.64) | 5684.58 (10074.78) | 5465.39 (9238.99) | 5410.9 (9439.5) | 5249.35 (7737.83) |

| Total* | |||||||||||

| N | 1638 | 1680 | 1740 | 1887 | 1880 | 2138 | 2442 | 2660 | 2898 | 3251 | 22 214 |

| Incidence+ | 3.82 | 3.85 | 3.92 | 4.17 | 4.09 | 4.61 | 5.24 | 5.69 | 6.2 | 6.98 | 4.88 |

*p<0.05 for time trend.

The overall crude incidence increased from 3.82 hospitalisations per 100 000 inhabitants in 2004 to 6.98 hospitalisations in 2013 (p<0.05). Significant differences in sex distribution were observed. Therefore, the percentage of men increased from 55.49% in 2004 to 57.35% in 2013. The mean age was 73.11±12.28 years, and a significant increase in age was observed from 72.16±11.56 years in 2004 to 74.62±11.80 years in 2013. The highest percentage of patients was found in the 65–79 years age group.

The Charlson comorbidity index increased during the study. The percentage of patients with a Charlson comorbidity index ≥2 was 15.14% in 2004, increasing to 26.95% in 2013 (p<0.05). Mean LOHS for admissions for IPF was 11.87±11.18 days in 2004, decreasing to 10.20±11.12 days in 2013 (p<0.05). However, no significant differences were found in IHM, which was 14.77% in 2004 and 13.72% in 2013. Mean cost per patient increased from €4838.51 in 2004 to €5410.90 in 2013 (p<0.05).

When we analysed diagnostic tests in patients hospitalised for IPF, no significant differences were found in the percentage of CT scans. However, we detected a significant decrease in the percentage of lung biopsies (10.68% in 2004 to 9.04% in 2013; p<0.05).

With regard to the treatment modalities, the use of non-invasive ventilation increased significantly from 1.53% in 2004 to 4.77% in 2013. However, no significant differences were found in the use of invasive mechanical ventilation. Similarly, no differences were detected in the percentage of patients who underwent lung transplantation during the study period.

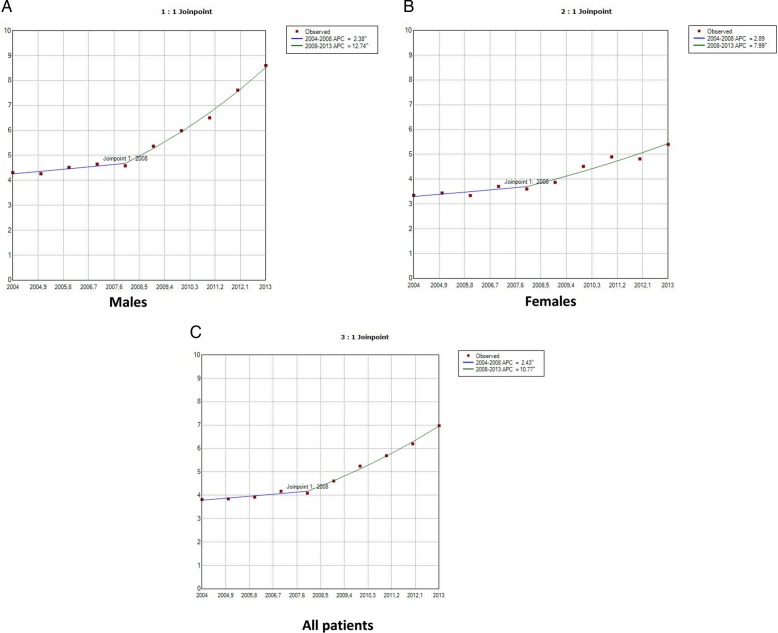

The joinpoint analysis revealed that the incidence of IPF in men increased by 2.38% per year from 2004 to 2008 and by 12.74% per year from 2008 to 2013 (figure 1A). In women the incidence increased by 2.89% per year from 2004 to 2008 (but not significantly) and by 7.99% per year from 2008 to 2013, when the difference proved to be statistically significant (figure 1B). We found that the total incidence of IPF increased by 2.43% per year from 2004 to 2008 and by 10.77% per year from 2008 to 2013 (figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Joinpoint analysis of annual hospitalisations for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Spain, 2004–2013: men (A), women (B) and all patients (C). Accent: APC is significantly different from zero (two-side, p<0.05). APC, annual per cent change (based on rates that were sex-adjusted and aged-adjusted using Spanish National Statistics Institute Census projections) calculated using joinpoint regression analysis.

Table 2 shows the most common primary diagnoses of patients discharged with a secondary diagnosis of IPF. The most frequent diagnosis was ‘acute and chronic respiratory failure’ (12.3%), followed by ‘other diseases of respiratory system, not elsewhere classified’ (9.6%), ‘acute respiratory failure’ (7.6%), ‘pneumonia, organism unspecified’ (6.4%) and ‘heart failure’ (5.1%). Table 3 shows the most common secondary diagnoses for patients discharged with a primary diagnosis of IPF. The most frequent diagnosis was ‘diabetes mellitus’ (7.3%), followed by ‘acute and chronic respiratory failure’ (6.1%), ‘acute respiratory failure’ (5.6%), ‘essential hypertension unspecified’ (5.3%) and ‘tobacco use disorder’ (3.2%).

Table 2.

Most common primary diagnosis in patients discharged with a secondary diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

| Diagnosis | N | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Acute and chronic respiratory failure | 1799 | 12.3 |

| Other diseases of respiratory system, not elsewhere classified | 1394 | 9.6 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 1106 | 7.6 |

| Pneumonia, organism unspecified | 940 | 6.4 |

| Heart failure | 747 | 5.1 |

| Acute bronchitis and bronchiolitis | 540 | 3.7 |

| Obstructive chronic bronchitis with acute exacerbation | 452 | 3.1 |

| Bronchiectasis with acute exacerbation | 214 | 1.5 |

Table 3.

Most common secondary diagnoses for patients discharged with a primary diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

| Diagnosis | n | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | 556 | 7.3 |

| Acute and chronic respiratory failure | 463 | 6.1 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 426 | 5.6 |

| Essential hypertension unspecified | 403 | 5.3 |

| Other diseases of respiratory system, not elsewhere classified | 356 | 4.7 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | 272 | 3.6 |

| Tobacco use disorder | 245 | 3.2 |

| Disorders of lipoid metabolism | 167 | 2.2 |

Table 4 summarises the results of the multivariate analysis of trends and factors associated with incidence and IHM among patients hospitalised for IPF. Possible confounders were controlled for using Poisson regression models. Incidence increased significantly from 2004 to 2013 (OR 1.02; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.03). Adjustment of the logistic regression model revealed a decrease in IHM (OR 0.98; 95% CI 0.97 to 0.99). The risk of IHM was higher in men, in patients aged ≥50 years, especially elderly patients, and in patients with one or more comorbidities.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of trends in incidence and IHM of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Spain from 2004 to 2013

| IRR | Incidence | IHM |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 0.68(0.66 to 0.70) | 0.80(0.74 to 0.86) |

| Age groups (years) | ||

| 0–49 | 1 | 1 |

| 50–64 | 6.70 (6.24 to 7.18) | 1.86 (1.41 to 2.45) |

| 65–79 | 32.33 (30.32 to 34.37) | 2.44 (1.88 to 3.17) |

| ≥80 | 97.16 (90.98 to 103.76) | 2.80 (2.15 to 3.65) |

| Charlson index | ||

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.99) | 1.17 (1.07 to 1.28) |

| ≥2 | 0.74 (0.71 to 0.76) | 1.29 (1.17 to 1.43) |

| Trend year | 1.02 (1.01 to 103) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) |

IHM, in-hospital mortality; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Discussion

In this observational study of 22 214 hospital admissions for IPF, we found a significant increase in the incidence of hospitalisations from 2004 to 2013. This may be due to an actual increase in the incidence, although it might also be explained by the higher diagnostic accuracy observed. The lack of similar studies in Spain makes it necessary to draw comparisons with other countries. The incidence of hospital admissions in the past 10 years has also increased in other European countries, such as Italy,4 Denmark,6 Greece5 and the UK.7 8 In the USA, most studies have shown similar trends,2 19 as they have in Asia.20 Only two studies—in Denmark21 and the USA10—have shown a decrease. In the American study, the downward trend could be due to the low number of patients, which limits the reliability of the results; in the Danish study, prevalent cases may have been included in the earlier time period, with more cases of other interstitial lung diseases.

Consistent with results published elsewhere, we found that IPF more frequently affects older people and men.4 7 8 10 11 21 The only exception was a study performed in Norway,22 where 55% of patients were women, possibly owing to the high rate of smoking (a risk factor for IPF) among Norwegian women.22

We observed an increase in comorbidities during the study period, as measured using the Charlson comorbidity index, which may have been due to the increase in overall survival. The increase may also be explained by the use of new specific and non-specific treatments in IPF, which could have led to more comorbidities in the final stages of the disease. Similar results have been reported by Raimundo et al.23 Of note, the most common secondary diagnosis associated with IPF in our study was diabetes mellitus (7.3%). A higher prevalence of diabetes in patients with IPF has been reported by other authors.24 25 Hyldgaard et al26 even showed that diabetes was associated with a statistically significant decrease in survival of IPF. The reason why diabetes is the most common secondary diagnosis could be the indiscriminate use of corticosteroids for treatment of this disease during the study period in Spain. The main therapeutic option in the early years was corticosteroids, even though it was known that their effectiveness was limited.1 27 The change in treatment recommendations for IPF (strong recommendations against corticosteroids at present, although this is a recommendation with very low-quality evidence)1 27 could reduce the likelihood of diabetes mellitus in patients with IPF in the coming years.

Consistent with international trends, we observed a decrease in LOHS in patients hospitalised with IPF from 2004 to 2013. This finding suggests that management of this disease improved in Spain during the study period. However, the decrease may be part of a general trend of decreasing LOHS for various respiratory diseases28 and with increased pressure for earlier discharge within healthcare services. This trend has also been observed in the UK and in the USA.29 30

Despite the reduction in LOHS, we observed, as in other international studies, increased costs associated with hospital admission for IPF.29 This increase could be explained by the increase in the cost of procedures over time and by the development of new specific treatments for this disease.31 However, a recent study in Spain shows that the cost associated with acute exacerbations represents almost 50% of total management costs for IPF. Therefore, the availability of new treatments that reduce the risk of acute exacerbations could reduce the costs associated with the disease.32 In any case we believe that these data will be useful in developing new approaches to healthcare and planning for the future cost of IPF inpatient care.

We found no significant differences in IHM due to IPF, in contrast with findings from previous studies on IPF-related mortality from the 1970s to the early 1990s in the USA, Canada, UK, Germany, Australia and New Zealand.33 34 In these studies, IPF-related mortality was higher in elderly patients and in men. In our study, mortality was also higher in elderly patients. In a recent study, Navaratnam et al8 analysed national mortality statistics in the UK to determine the underlying cause of death over a period of more than 40 years and found an annual increase of 5% in mortality after controlling for age and sex. However, the authors examined crude incidence and not the incidence of admitted patients. Again, mortality rates were higher in older age groups and in men. Our findings on mortality are difficult to explain, although they could be associated with differences in country-specific coding practices. It is also important to consider the role of home palliative care, which can determine the likelihood of dying in a non-hospital setting.35

With regard to the treatment modalities used during hospitalisation, we found a significant increase in the use of non-invasive ventilation in patients hospitalised for IPF. Several studies have shown that the use of invasive mechanical ventilation to treat respiratory failure in IPF improves neither prognosis nor survival.36 37 This may be the reason why more patients receive non-invasive ventilation in intensive care units or other hospital departments.38

As for diagnostic tests, we observed a significant decrease in the percentage of lung biopsies during the study period, although this trend may change in the next few years thanks to newly available antifibrotic treatments for IPF. International guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of IPF require a lung biopsy if high-resolution CT does not confirm usual interstitial pneumonia.1 Consequently, the number of lung biopsies is expected to increase in patients with IPF.

The main strengths of our study are its large sample size and standardised methodology, which were maintained throughout the study period. Nevertheless, our study is also subject to a series of limitations. First, the use of ICD-9-CM codes to identify patients hospitalised for IPF entails a certain degree of bias. The main concern of using disease codes in such analyses is the accuracy of the IPF diagnosis, because the diagnostic codes used to identify IPF in the administrative databases (the most common approach used in IPF epidemiology studies) have changed over time, as has the definition of the disease.39 40 Second, it is unknown whether the diagnoses were made by respiratory medicine specialists or whether they were based on multidisciplinary discussions in all cases. Third, studies such as ours, which was based on an administrative database, involve large populations, thus rendering re-evaluation of data more difficult—if not impossible—because of the need for access to a large data set, including histology of lung biopsies and original high-resolution CT scans. Therefore, the need for a complete search of all medical records would make the study too laborious and costly. Finally, IPF outcomes could be affected by treatment, a variable that we did not include in our study. Therefore, we cannot identify whether changes in therapy during the study period affected the results. Nevertheless, the CMBD database has the advantage that it is mandated by the National Public Health System, thus covering almost 100% of admissions in Spain.15 In addition, the fact that Spain is a large country with a public health system that provides a complete range of medical services free of charge to the entire population means that patients come from a variety of socioeconomic categories, thus strengthening the external validity of our results.

In conclusion, we provide robust data indicating that, despite increases in the number of hospital admissions due to IPF over time, IHM and LOHS decreased, albeit with increasing healthcare costs. These results suggest that the management of IPF improved in Spain during the study period. New antifibrotic treatments seem to be a promising option for patients with this devastating disease.

Footnotes

Contributors: JdM-D participated in the study concept, design, coordination, statistical analysis and drafting of the manuscript. FP-S, ALdA, RJ-G, IJ-T, VH-B, GS-M and LP-M participated in the study concept, design, statistical analysis and drafting of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was partly funded by URJC-Banco Santander to the Grupo de Excelencia Investigadora ITPSE (grant number 30VCPIGI03).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Any investigator can apply for the databases filling the questionnaire available at http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/estadisticas/estMinisterio/SolicitudCMBDdocs/Formulario_Peticion_Datos_CMBD.pdf. All other relevant data are in the paper.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:788–824. 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olson AL, Swigris JJ, Lezotte DC et al. Mortality from pulmonary fibrosis increased in the United States from 1992 to 2003. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:277–84. 10.1164/rccm.200701-044OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coultas DB, Hubbard R. Epidemiology of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. In: Lynch JP. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2003:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agabiti N, Porretta MA, Bauleo L et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) incidence and prevalence in Italy. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2014;31:191–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karakatsani A, Papakosta D, Rapti A et al. Epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases in Greece. Respir Med 2009;103:1122–9. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xaubet A, Ancochea J, Morell F et al. Report on the incidence of interstitial lung diseases in Spain. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2004;21:64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gribbin J, Hubbard RB, Le Jeune I et al. Incidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and sarcoidosis in the UK. Thorax 2006;61:980–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navaratnam V, Fleming KM, West J et al. The rising incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the U.K. Thorax 2011;66:462–7. 10.1136/thx.2010.148031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyldgaard C, Hilberg O, Muller A et al. A cohort study of interstitial lung diseases in central Denmark. Respir Med 2014;108:793–9. 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernández Pérez ER, Daniels CE, Schroeder DR et al. Incidence, prevalence, and clinical course of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a population based study. Chest 2010;137:129–37. 10.1378/chest.09-1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J et al. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:810–16. 10.1164/rccm.200602-163OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Natsuizaka M, Chiba H, Kuronuma K et al. Epidemiologic survey of Japanese patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and investigation of ethnic differences. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;190:773–9. 10.1164/rccm.201403-0566OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Instituto Nacional de Gestión sanitaria, Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo: Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos, Hospitales del INSALUD. http://www.ingensa.msc.es/estadEstudios/documPublica/pdf/CMBD-2004.pdf.

- 14.Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Population estimates. http://www.inw.wa (accessed 15 Jan 2015).

- 15.Instituto Nacional de Salud. CMBD Insalud. Análisis de los GRDs. Año 2000. http://www.ingesamsc.es/estadEstudios/documPublica/cmbd2000.htm (accessed: 15 Jan 2015).

- 16.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613–19. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ et al. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000;19:335–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joinpoint Regression Program. Version 4.0.4. Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research program, National Cancer Institute 2013.

- 19.Raghu G, Chen SY, Yeh WS et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older: incidence, prevalence, and survival, 2001–11. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:566–72. 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70101-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai CC, Wang CY, Lu HM et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Taiwan—a population-based study. Respir Med 2012;106: 1566–74. 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kornum JB, Christensen S, Grijota M et al. The incidence of interstitial lung disease 1995–2005: a Danish nationwide population-based study. BCM Pulm Med 2008;8:24 10.1186/1471-2466-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Von Plessen C, Grinde O, Gulsvik A. Incidence and prevalence of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis in a Norwegian community. Respir Med 2003;97:428–35. 10.1053/rmed.2002.1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raimundo K, Chang E, Broder MS et al. Clinical and economic burden of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pulm Med 2016;16:2 10.1186/s12890-015-0165-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enomoto T, Usuki J, Azuna A et al. Diabetes mellitus may increase risk for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2003;123:2007–11. 10.1378/chest.123.6.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Sancho Figueroa MC, Carrillo G, Perez-Padilla R et al. Risk factors for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in a Mexican population. A case-control study. Respir Med 2010;104:305–9. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyldgaard C, Hilberg O, Bendstrup E. How does comorbidity influence survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Respir Med 2014; 108:647–53. 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richeldi L, Davies HR, Ferrera G et al. Corticosteroids for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(3):CD002880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Miguel Díez J, Jimenez-García R, Jimenez D et al. Trends in hospital admissions for pulmonary embolism in Spain from 2002 to 2011. Eur Respir J 2014;44:942–50. 10.1183/09031936.00194213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navaratnam V, Fogarty AW, Glendening R et al. The increasing secondary care burden of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: hospital admission trends in England from 1998 to 2010. Chest 2013;143:1078–84. 10.1378/chest.12-0803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fioret D, Mannino D, Roman J. In-hospital mortality and costs related to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis between 1993 and 2008. Chest 2011;140:1038A 10.1378/chest.1117428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collard HR, Chen SY, Yeh WS et al. Health care utilization and costs of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in U.S. Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12:981–7. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201412-553OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morell F, Esser D, Lim J et al. Treatment patterns, resource use and costs of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Spain-results of a Delphi Panel. BMC Pulm Med 2016;16:7 10.1186/s12890-016-0168-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mannino DM, Etzel RA, Parrish RG. Pulmonary fibrosis deaths in the United States, 1979–1991. An analysis of multiple-cause mortality data. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:1548–52. 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hubbar R, Johnston I, Coultas DB et al. Mortality rates from cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis in seven countries. Thorax 1996;51:711–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindell KO, Liang Z, Hoffman LA et al. Palliative care and location of death in decedents with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2015;147:423–9. 10.1378/chest.14-1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stern JB, Mal H, Groussard O et al. Prognosis of patients with advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis requiring mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Chest 2001;120:213–19. 10.1378/chest.120.1.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blivet S, Philit F, Sab JM et al. Outcome of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis admitted to the ICU for respiratory failure. Chest 2001;120:209–12. 10.1378/chest.120.1.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Güngör G, Tatar D, Saltürk C et al. Why do patients with interstitial lung diseases fail in the ICU? a 2-center cohort study. Respir Care 2013;58:525–31. 10.4187/respcare.01734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caminati A, Madotto F, Cesana G et al. Epidemiological studies in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: pitfalls in methodologies and data interpretation. Eur Respir Rev 2015;24:436–44. 10.1183/16000617.0040-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gjonbrataj J, Choi WI, Bahn YE et al. Incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Korea based on the 2011 ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement. Int J Tuber Lung Dis 2015;19:742–6. 10.5588/ijtld.14.0650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]