Abstract

Objective

Financial incentives may encourage private for-profit providers to perform more caesarean section (CS) than non-profit hospitals. We therefore sought to determine the association of for-profit status of hospital and odds of CS.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews from the first year of records through February 2016.

Eligibility criteria

To be eligible, studies had to report data to allow the calculation of ORs of CS comparing private for-profit hospitals with public or private non-profit hospitals in a specific geographic area.

Outcomes

The prespecified primary outcome was the adjusted OR of births delivered by CS in private for-profit hospitals as compared with public or private non-profit hospitals; the prespecified secondary outcome was the crude OR of CS in private for-profit hospitals as compared with public or private non-profit hospitals.

Results

15 articles describing 17 separate studies in 4.1 million women were included. In a meta-analysis of 11 studies, the adjusted odds of delivery by CS was 1.41 higher in for-profit hospitals as compared with non-profit hospitals (95% CI 1.24 to 1.60) with no relevant heterogeneity between studies (τ2≤0.037). Findings were robust across subgroups of studies in stratified analyses. The meta-analysis of crude estimates from 16 studies revealed a somewhat more pronounced association (pooled OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.49 to 2.27) with moderate-to-high heterogeneity between studies (τ2≥0.179).

Conclusions

CS are more likely to be performed by for-profit hospitals as compared with non-profit hospitals. This holds true regardless of women's risk and contextual factors such as country, year or study design. Since financial incentives are likely to play an important role, we recommend examination of incentive structures of for-profit hospitals to identify strategies that encourage appropriate provision of CS.

Keywords: caesarean section, for-profit hospital, non-profit hospital, financial incentives, medical practice variation, health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Major strengths of our meta-analysis include a broad literature search, screening and data extraction performed in duplicate, careful exclusion of studies with overlapping populations and an exploration of study characteristics as a potential source of variation between studies.

A major limitation of our meta-analysis lies in the variation between studies in design, number of hospital units involved, size and characteristics of study population, type of data used, outcome measure and variables used in statistical analysis. Despite these differences, the results of the meta-analysis of adjusted estimates were surprisingly consistent.

Introduction

Caesarean section (CS) has greatly improved perinatal outcomes by reducing newborn and maternal mortality,1 but the increasing frequency of CS has raised concerns, particularly when performed in the absence of clear-cut medical indications.2 3 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data reveal an average annual increase of 0.66% in member countries,4 and similar trends are evident elsewhere.2 A recent analysis of national CS rates found that rates up to 19% were inversely correlated with maternal and neonatal mortality.5 Many countries have CS rates higher than 19%, even though there is no evidence to suggest that higher rates are associated with further decreases in maternal and neonatal mortality.5 6 In Brazil, for example, CS rates are estimated at 46%.7 Higher CS rates increase the cost of care3 8 and may have negative effects on the health of mothers9 and newborns.10

CS rates vary considerably across regions and hospitals within countries, and a closer look at this variation may help to identify factors that contribute to higher than necessary rates.2 CS receive higher reimbursement than normal vaginal births in most healthcare systems.11 12 We therefore hypothesised that financial incentives encourage private providers with an emphasis on profit to perform more CS than non-profit hospitals, and conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the association of for-profit status with the odds of delivery by CS.

Methods

Data sources

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews from inception to 8 February 2016, when the search was last updated. We combined search terms referring to CS, such as ‘operative delivery’, ‘C section’, ‘Cesarean’, ‘Cesarean delivery’, with search terms related to the design of studies such as ‘small area analysis’, ‘medical practice variation’, and search terms related to determinants of variation and increase of CS rates. We did not restrict searches by type of language or publication date. Full details are given in online supplementary appendix 1. In addition, we manually searched the reference lists of all included studies and earlier systematic reviews that we identified.

bmjopen-2016-013670supp_appendix1.pdf (279.5KB, pdf)

Study selection and outcomes

To be eligible studies had to report data to allow the calculation of ORs of CS comparing private for-profit hospitals with public or private non-profit hospitals in a specific geographic area. The prespecified primary outcome was the OR of births delivered by CS in private for-profit hospitals as compared with public or private non-profit hospitals adjusted for confounding factors as specified by individual investigators. The prespecified secondary outcome was the crude OR of CS in private for-profit hospitals as compared with public or private non-profit hospitals. Studies were included if they reported data on either primary or secondary outcome.

Data extraction

Two researchers (IH and XL) screened the papers and extracted data independently. Articles that were not published in English were reviewed by authors with knowledge of those languages. Differences were resolved by consensus. Data from full-text articles were extracted onto a data extraction sheet designed to capture data on study population (history of previous CS, parity, risk factors for CS, characteristics of newborn), study design (size, sampling strategy, cross-sectional vs retrospective cohort study), data sources (birth registries, hospital records, surveys, insurance claims or census data), setting (country and period of data collection), type of CS analysed (indication for CS established before labour (ie, planned), indication for CS established during labour, any CS irrespective of indication) and statistical analysis (including variables adjusted for). We extracted adjusted and/or unadjusted ORs of CS in private for-profit hospitals as compared with CS in public or private non-profit hospitals.

Analysis

We used standard inverse-variance random-effects meta-analysis to combine ORs overall and stratified by type of reference group (ie, public or private non-profit hospitals). An OR above 1 indicates that CS are more frequently performed in private for-profit hospitals than in public or private non-profit hospitals. We calculated the variance estimate τ2 as a measure of heterogeneity between studies.13 We prespecified a τ2 of 0.04 to represent low heterogeneity, 0.16 to represent moderate and 0.36 to represent high heterogeneity between studies.14 We conducted analyses stratified by study design (cross-sectional vs retrospective cohort study), national CS rates (moderate, high, very high), period of data collection (up to 1994, between 1995 and 2004, 2005 and later), parity (primiparae and multiparae combined vs primiparae only), history of previous CS and type of CS analysed (indication for CS established before labour (ie, planned CS), indication for CS established during labour, any CS irrespective of indication) to investigate potential reasons for between-study heterogeneity and used χ2 tests to calculate p values for interaction, or tests for linear trend in case of more than two ordered strata. National CS rates were classified into moderate (>15% to 20%), high (>20% to 40%) and very high (>40%) based on data reported by the WHO.5 All p values are two-sided. We used STATA, release V.13, for all analyses (Stata-Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in this study.

Results

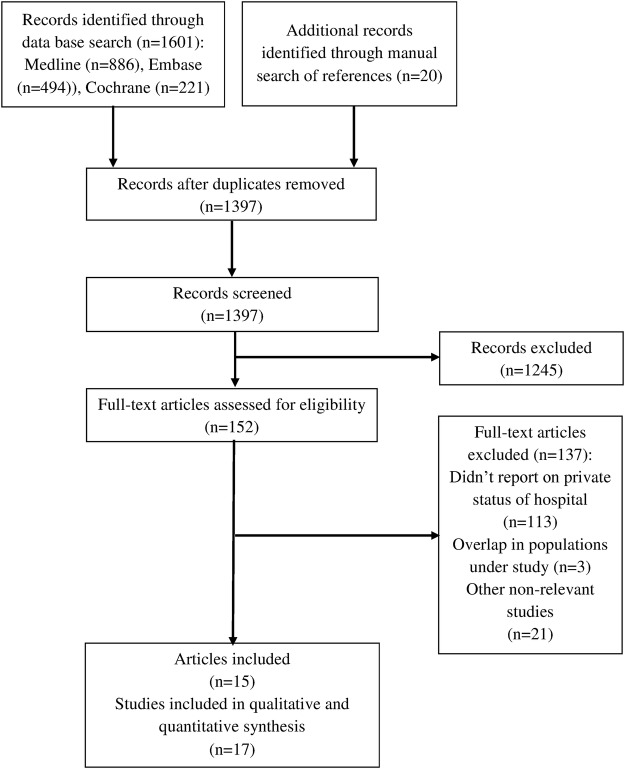

A total of 1621 records were identified by our search (figure 1): 886 from MEDLINE: 494 from EMBASE; 221 from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and 20 from manual search. After removing duplicates, we screened 1397 records for eligibility, retained 373 records for a more careful examination of titles and abstracts, and excluded another 221 records because they failed to match eligibility criteria. We assessed the full texts of the 152 remaining records and excluded another 113 that did not report private status of hospital, 21 that were otherwise irrelevant and 3 studies that had an overlapping population. This left us with a total of 15 articles describing 17 separate studies in 4.1 million women that were included in review and meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

The flow diagram of review.

Characteristics of studies and populations are presented in table 1 and online supplementary appendices 2–4. Fifteen studies were cross-sectional, and two were retrospective cohort studies. All studies were published in English, except for one study in French. Most studies were from France (4) and the USA (4). Exclusion criteria varied considerably: 4 studies excluded girls aged 14 or below, 3 excluded multiparas, 7 excluded women with previous CS, 13 excluded stillbirths and multiple births, 5 excluded cases with specific presentations of the fetus, and 5 studies excluded cases with other high risk factors for CS; 15 studies excluded preterm births. Twelve studies included the entire population of eligible cases, while five studies selected cases randomly. Seven studies used surveys, nine hospital records, four birth registries, two insurance claims and one census data. Five studies reported ORs of CS with indications established before labour (including CS on maternal request) only, 2 reported CS with indications estabished during labour and 10 reported ORs of any CS. Online supplementary appendix 4 presents the characteristics that estimates were adjusted for. Among 11 studies reporting adjusted estimates, the median number of characteristics adjusted for was 8 (range 2–124).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author | Year | Country | Study design | Number of cases | Number of hospital units | Year of data collection | Population | Sampling | Type of CS analysed | National CS rates* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braveman et al | 1995 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 213 761 | Unclear | 1991 | Primiparae; no previous CS; any risk | Consecutive | Any | High |

| Naiditch et al | 1997 | France | Cross-sectional | 39 880 | 944 | 1991 | Primiparae and multiparae; no previous CS; any risk | Random | Before labour | Moderate |

| Gomes et al. A | 1999 | Brazil | Cross-sectional | 6750 | 8 | 1978–1979 | Primiparae and multiparae; with or without previous CS; any risk | Consecutive | Any | Very high |

| Gomes et al. B | 1999 | Brazil | Cross-sectional | 2846 | 10 | 1994 | Primiparae and multiparae; with or without previous CS; any risk | Consecutive | Any | Very high |

| Gonzalez-Perez et al | 2001 | Mexico | Cross-sectional | 1 716 446 | Unclear | 1994–1997 | Primiparae and multiparae; with or without previous CS; any risk | Consecutive | Any | High |

| Korst et al | 2005 | USA | Cross-sectional | 443 532 | 288 | 1995 | Primiparae and multiparae; no previous CS; any risk | Consecutive | During labour | High |

| Mossialos et al. | 2005 | Greece | Cross-sectional | 805 | 3 | 2002 | Primiparae and multiparae; with or without previous CS; any risk | Consecutive | Any | High |

| Carayol et al A | 2007 | France | Cross-sectional | 1479 | Unclear | 1972, 1995, 1998, 2003 | Primiparae and multiparae; no previous CS; high risk | Random | Before labour | Moderate |

| Carayol et al B | 2007 | France | Cross-sectional | 6080 | 138 | 2001-2002 | Primiparae and multiparae; no previous CS; high risk | Random | Before labour | Moderate |

| Xirasagar and Lin | 2007 | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 739 531 | 942 | 1997–2000 | Primiparae and multiparae; with or without previous CS; any risk | Consecutive | Before labour† | High |

| Coonrod et al | 2008 | USA | Cross-sectional | 28 863 | 40 | 2005 | Primiparae; low risk | Consecutive | Any | High |

| Coulm et al | 2012 | France | Cross-sectional | 9530 | 535 | 2010 | Primiparae and multiparae; no previous CS; low risk | Consecutive | Any | Moderate |

| Huesch et al | 2014 | USA | Cross-sectional | 408 355 | 254 | 2010 | Primiparae and multiparae; no previous CS; any risk | Consecutive | Before labour | High |

| Raifman et al A | 2014 | Brazil | Cross sectional | 4918 | Not Reported | 1996 | Primi- and multiparae; with or without previous CS; any risk | Random | Any | Very high |

| Raifman et al B | 2014 | Brazil | Cross sectional | 5768 | Not Reported | 2006 | Primi- and multiparae; with or without previous CS; any risk | Random | Any | Very high |

| Schemann et al | 2015 | Australia | Cross sectional | 61 894 | 81 | 2007-2011 | Multiparae; with previous CS | Consecutive | Any | High |

| Sebastião et al | 2016 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 412 192 | 122 | 2004-2011 | Primiparae; low risk | Consecutive | During labour | High |

*National CS rates classified according to WHO data reported for 2008 into moderate (>15% to 20%), high (>20% to 40%) and very high (>40%).

†On maternal request.

CS, caesarean section.

bmjopen-2016-013670supp_appendix2.pdf (114.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013670supp_appendix3.pdf (93.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013670supp_appendix4.pdf (133KB, pdf)

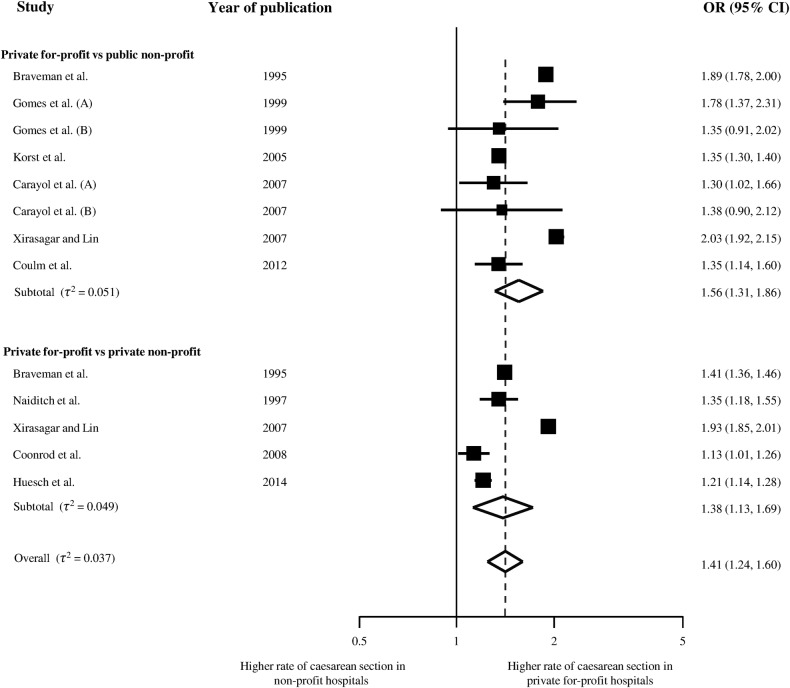

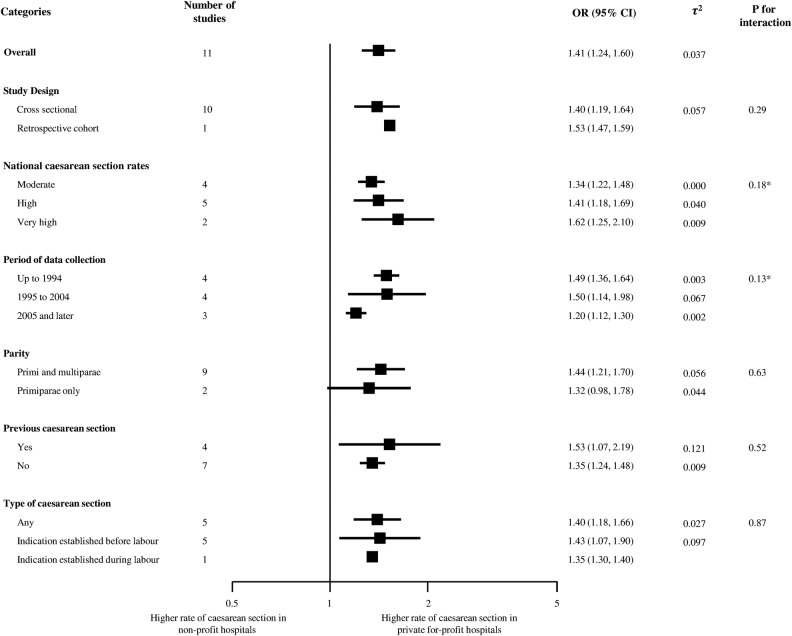

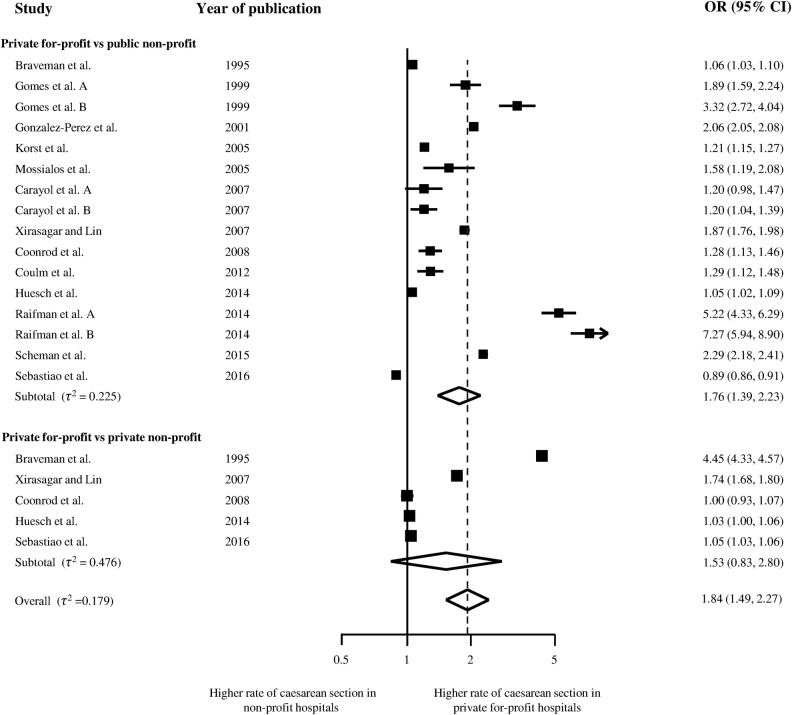

Figure 2 presents the meta-analysis of the 11 studies that reported adjusted ORs,15–25 with 6 studies using public non-profit hospitals as reference group, three private non-profit hospitals and two using both. Overall, the odds of receiving CS was 1.41 times higher in for-profit hospitals as compared with either of the two types of non-profit hospitals (95% CI 1.24 to 1.60), with no relevant heterogeneity between studies (τ2≤0.037) and little evidence for an interaction between estimated ORs and type of reference group (p for interaction=0.20). Figure 3 presents results of stratified analyses of adjusted ORs. Estimates varied to some extent between strata, but all tests for interaction or trend across subgroups were negative. Pooled estimates ranged from 1.20 to 1.62 across subgroups. There was little evidence to suggest secular trends (p for trend=0.13) or an association of ORs with national CS rates (p for trend=0.18). Figure 4 presents the meta-analysis of crude ORs with moderate-to-high heterogeneity between studies (τ2≥0.179), a somewhat more pronounced average association (pooled OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.49 to 2.27) and again little evidence for an interaction between estimated ORs and type of reference group (p for interaction=0.48).

Figure 2.

Adjusted ORs of caesarean section.

Figure 3.

Stratified analyses. *p Value for linear trend.

Figure 4.

Crude ORs of caesarean section.

Discussion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis indicates that the odds of receiving a CS are on average 1.4 times higher in private for-profit hospitals than in non-profit hospitals. Findings were robust across all subgroups of studies in stratified analyses. In particular, there was little evidence to suggest secular trends or an association with national CS rates. Even though, a test for trend across periods of data collection was negative, we found the association between for-profit status of hospitals and odds of CS less pronounced in recent years. In view of the negative test for trend, this could be a chance finding. Alternatively, this may reflect attempts of care providers and policymakers to attenuate raising CS rates over time.

Context

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to address the association of CS rates with for-profit status of hospitals. We are aware of three recent meta-analyses that examined the association of CS rates with obesity,26 ethnic origin27 and labour induction.28 In a meta-analysis of unadjusted estimates from prospective and retrospective cohort studies, Poobalan et al26 found a 53% increase in the odds of CS associated with maternal overweight and a 126% increase with obesity. Merry et al27 found a 41% increase in the adjusted odds of CS associated with sub-Saharan African origin, and a 99% increase associated with Somali origin of women. Estimates for South, North-African/West Asian and Latin American women were similar but statistically not significant. Finally, in a meta-analysis of randomised trials, Mishanina et al28 found expectant management to be associated with a 14% increase in the risk of CS. Our meta-analysis indicates agreement across 17 studies performed in seven countries as to the direction of this association, even though the magnitude of the association shows some variability. Our pooled estimate of a 41% increase in adjusted odds of CS associated with for-profit status of hospital has a similar or larger magnitude than the associations found for the characteristics above and therefore appears relevant for clinical and policy decision-making.

Strengths and limitations

A major limitation of our meta-analysis lies in the variation between studies in design, number of hospital units' involved, size and characteristics of study population, type of data used, outcome measure and variables used in statistical analysis. Despite these differences, the results of the meta-analysis of adjusted estimates were surprisingly consistent. Conversely, unadjusted estimates showed considerable heterogeneity between studies, which suggests confounding by medical and non-medical factors as a reason for variation between studies. Among these factors are socioeconomic status, preferences and clinical condition of women, fetus characteristics, medical care during pregnancy and delivery as well as physician, hospital and health system characteristics.2 Professionals often attribute higher rates of procedures to the gravity of clinical conditions of patient receiving an intervention. This argument is not supported by the data of this review as associations of CS rates with for-profit status were consistently found in analyses adjusted for a wide range of risk factors (see online supplementary appendix 4). Major strengths of our meta-analysis include a broad literature search, screening and data extraction performed in duplicate, careful exclusion of studies with overlapping populations and an exploration of study characteristics as a potential source of variation between studies.

Mechanisms

Financial incentives are likely to contribute to the observed association. The literature has described the influence of supply factors in the type and amount of care provided for a given condition.29–32 Private for-profit institutions may create financial incentive structures that encourage more resource-intensive33 and expensive procedures,11 34–36 since that will increase their profits. The payment model of hospitals and physicians is another important factor.11 32 34 35 37 Fee for service reimbursement may be more common for private for-profit hospitals and will encourage hospitals and physicians to provide more procedures than medically indicated38–40 and increase time pressure on physicians to perform CS instead of waiting longer for a normal birth.41 42 Health insurers can also encourage overprovision of CS as they tend to reimburse hospitals and physicians better for CS than for vaginal delivery.11 43 44 Finally, private for-profit institutions typically have a higher number of qualified physicians, more resources and better infrastructure,2 32 45–47 which will encourage overprovision of care in private for-profit institutions.

Implications for research

Although immediate steps to improve clinical decision-making for CS should not be delayed, further research would inform the persistent dilemma of misalignment between good care and financial incentives. Since financial incentives differ across and within countries, there is a need for additional context-specific investigation of the economic drivers of overuse.48 Policy analysis focusing on for-profit hospitals should examine further the interplay of specific factors for each country or, ideally, individual contracts between insurers and providers within countries to identify financial incentives that cause private for-profit hospitals to perform more CS than non-profit hospitals. Such analyses should explore if financial incentives interact at the physician level, such as physician payment schemes, or at the hospital level, including informal or formal pressure on physicians to choose more expensive procedures or save time by performing a CS instead of waiting longer for a normal birth. In some countries, such analyses should also extend to not for-profit hospitals, if fee for service payments are used regardless of for-profit status. The effects of the level and type of government regulation of hospitals, type of health insurance and implementation of clinical guidelines also require further study.

Implications for policymaking

The persisting increase of CS rates in many health systems despite the growing recognition of CS overuse suggests that current clinical guidelines are not sufficient.2 Improving clinical decision-making by providing clear clinical guidelines that are evidence based would be one step forward. Equally important is the alignment of financial incentives with the objective to improve care without increasing costs. The higher odds of CS in the for-profit sector suggest that physicians and hospitals are responsive to financial incentives. Changing reimbursement policies so that vaginal deliveries and CS are paid similarly could keep overall payments to physicians and hospitals approximately constant without encouraging unnecessary CS but will not guarantee an elimination of overuse. Negative incentives, such as penalising hospitals for high CS rates could also be considered, but require monitoring for unintended consequences.49 A decrease of unnecessary CS, a cost-effective use of resources and improved health outcomes for mothers and newborns should be the ultimate goal.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis indicates that CS are more likely to be performed in for-profit hospitals as compared with non-profit hospitals. This holds true regardless of women's risk and contextual factors such as country, year or study design. Since financial incentives are likely to play an important role, we recommend examination of incentive structures, including reimbursement schemes of for-profit hospitals, to identify strategies that encourage best clinical judgement and outcome rather than rewarding expensive procedures that are clinically unnecessary and potentially harmful for mothers and newborns.

Footnotes

Contributors: IH, DCG and PJ have developed the idea for the study. IH, XL and DCG were involved in the study conception, preliminary literature review and design of the search strategy and the study protocol. IH, LS and XL were involved in screening and data extraction of papers. All authors reviewed data extraction output. IH, LS, BRdC and PJ designed and performed the meta-analysis. IH, LS, KT, BRdC and PJ drafted the report, which was critically reviewed and approved by all authors.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Stephenson PA, Bakoula C, Hemminki E et al. . Patterns of use of obstetrical interventions in 12 countries. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1993;7:45–54. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.1993.tb00600.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoxha I, Busato A, Luta X. Medical practice variations in reproductive, obstetric, and gynaecological care. In: Johnson A, Stukel T, eds. Medical practice variations. Health services research series. New York, NY: Springer, 2015:141–60. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Main EK, Morton CH, Melsop K et al. . Creating a public agenda for maternity safety and quality in cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:1194–8. doi:http://10.1097/AOG.0b013e31826fc13d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.OECD. Health at a glance 2011L OECD indicators. OECD Publishing, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molina G, Weiser TG, Lipsitz SR et al. . Relationship between cesarean delivery rate and maternal and neonatal mortality. JAMA 2015;314:2263–70. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Alton ME, Hehir MP. Cesarean delivery rates: revisiting a 3-decades-old dogma. JAMA 2015;314:2238–40. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbons L, Belizán JM, Lauer JA et al. . The global numbers and costs of additionally needed and unnecessary caesarean sections performed per year: overuse as a barrier to universal coverage. World Health Report 2010;30:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckerlund I, Gerdtham UG. Econometric analysis of variation in cesarean section rates. A cross-sectional study of 59 obstetrical departments in Sweden. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1998;14:774–87. doi:10.1017/S0266462300012071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Souza JP, Gulmezoglu A, Lumbiganon P et al. . Caesarean section without medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short-term maternal outcomes: the 2004-2008 WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health. BMC Med 2010;8:71 doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black M, Bhattacharya S, Philip S et al. . Planned cesarean delivery at term and adverse outcomes in childhood health. JAMA 2015;314:2271–9. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.16176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant D. Physician financial incentives and cesarean delivery: new conclusions from the healthcare cost and utilization project. J Health Econ 2009;28:244–50. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huynh L, McCoy M, Law A et al. . Systematic literature review of the costs of pregnancy in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 2013;31:1005–30. doi:10.1007/s40273-013-0096-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. doi:10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.da Costa BR, Juni P. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized trials: principles and pitfalls. Eur Heart J 2014;35:3336–45. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braveman P, Egerter S, Edmonston F et al. . Racial/ethnic differences in the likelihood of cesarean delivery, California. Am J Public Health 1995;85:625–30. doi:10.2105/AJPH.85.5.625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomes UA, Silva AA, Bettiol H et al. . Risk factors for the increasing caesarean section rate in Southeast Brazil: a comparison of two birth cohorts, 1978-1979 and 1994. Int J Epidemiol 1999;28:687–94. doi:10.1093/ije/28.4.687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korst LM, Gornbein JA, Gregory KD. Rethinking the cesarean rate: how pregnancy complications may affect interhospital comparisons. Med Care 2005;43:237–45. doi:10.1097/00005650-200503000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carayol M, Blondel B, Zeitlin J et al. . Changes in the rates of caesarean delivery before labour for breech presentation at term in France: 1972-2003. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2007;132:20–6. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carayol M, Zeitlin J, Roman H et al. . Non-clinical determinants of planned cesarean delivery in cases of term breech presentation in France. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2007;86:1071–8. doi:10.1080/00016340701505242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raifman S, Cunha AJ, Castro MC. Factors associated with high rates of caesarean section in Brazil between 1991 and 2006. Acta Paediatr 2014;103:e295–e9. doi:10.1111/apa.12620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coulm B, Le Ray C, Lelong N et al. . Obstetric interventions for low-risk pregnant women in France: do maternity unit characteristics make a difference? Birth 2012;39:183–91. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2012.00547.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xirasagar S, Lin HC. Maternal request CS--role of hospital teaching status and for-profit ownership. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2007;132:27–34. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coonrod DV, Drachman D, Hobson P et al. . Nulliparous term singleton vertex cesarean delivery rates: institutional and individual level predictors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:694. e1–11; discussion e11 doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2008.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huesch MD, Currid-Halkett E, Doctor JN. Measurement and risk adjustment of prelabor cesarean rates in a large sample of California hospitals. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:443. e1.–. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naiditch M, Levy G, Chale JJ et al. . [Cesarean sections in France: impact of organizational factors on different utilization rates]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 1997;26:484–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poobalan AS, Aucott LS, Gurung T et al. . Obesity as an independent risk factor for elective and emergency caesarean delivery in nulliparous women--systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Obes Rev 2009;10:28–35. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00537.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merry L, Small R, Blondel B et al. . International migration and caesarean birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:27 doi:10.1186/1471-2393-13-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mishanina E, Rogozinska E, Thatthi T et al. . Use of labour induction and risk of cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2014;186:665–73. doi:10.1503/cmaj.130925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wennberg JE, Barnes BA, Zubkoff M. Professional uncertainty and the problem of supplier-induced demand. Soc Sci Med 1982;16:811–24. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(82)90234-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulley AG. Inconvenient truths about supplier induced demand and unwarranted variation in medical practice. BMJ 2009;339:b4073 doi:10.1136/bmj.b4073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersen TF, Mooney G. The challenges of medical practice variations. Macmillan, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wennberg JE. Tracking medicine: a researcher's quest to understand health care. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010:xix, 319. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armour BS, Pitts MM, Maclean R et al. . The effect of explicit financial incentives on physician behavior. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1261–6. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.10.1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gruber J, Kim J, Mayzlin D. Physician fees and procedure intensity: the case of cesarean delivery. J Health Econ 1999;18:473–90. doi:10.1016/S0167-6296(99)00009-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gruber J, Owings M. Physician financial incentives and cesarean section delivery. Rand J Econ 1996;27:99–123. doi:10.2307/2555794 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodrick E, Salancik G. Organizational discretion in responding to institutional practices: hospitals and cesarean births. Adm Sci Q 1996;41:1–28. doi:10.2307/2393984 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gawande AA, Fisher ES, Gruber J et al. . The cost of health care—highlights from a discussion about economics and reform. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1421–3. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0907810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldfield N, Averill R, Vertrees J et al. . Reforming the primary care physician payment system: eliminating E & M codes and creating the financial incentives for an “advanced medical home”. J Ambul Care Manage 2008;31:24–31. doi:10.1097/01.JAC.0000304093.05840.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keeler EB, Brodie M. Economic incentives in the choice between vaginal delivery and cesarean section. Milbank Q 1993;71:365–404. doi:10.2307/3350407 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bland ES, Oppenheimer LW, Holmes P et al. . The effect of income pooling within a call group on rates of obstetric intervention. CMAJ 2001;164:337–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Regt RH, Minkoff HL, Feldman J et al. . Relation of private or clinic care to the cesarean birth rate. N Engl J Med 1986;315:619–24. doi:10.1056/NEJM198609043151005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Regt RH, Marks K, Joseph DL et al. . Time from decision to incision for cesarean deliveries at a community hospital. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:625–9. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819970b8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grant D. Explaining source of payment differences in U.S. cesarean rates: why do privately insured mothers receive more cesareans than mothers who are not privately insured? Health Care Manag Sci 2005;8:5–17. doi:10.1007/s10729-005-5212-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burns LR, Geller SE, Wholey DR. The effect of physician factors on the cesarean section decision. Med Care 1995;33: 365–82. doi:10.1097/00005650-199504000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodman DC, Fisher ES, Little GA et al. . Are neonatal intensive care resources located according to need? Regional variation in neonatologists, beds, and low birth weight newborns. Pediatrics 2001;108:426–31. doi:10.1542/peds.108.2.426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodman DC. Do we need more physicians? Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;(Suppl Web Exclusives):W4.67–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodman DC. The pediatrician workforce: current status and future prospects. Pediatrics 2005;116:e156–73. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corallo AN, Croxford R, Goodman DC et al. . A systematic review of medical practice variation in OECD countries. Health Policy 2014;114:5–14. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown JR, Sox HC, Goodman DC. Financial incentives to improve quality: skating to the puck or avoiding the penalty box? JAMA 2014;311:1009–10. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013670supp_appendix1.pdf (279.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013670supp_appendix2.pdf (114.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013670supp_appendix3.pdf (93.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013670supp_appendix4.pdf (133KB, pdf)