Abstract

Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) is known to activate inflammatory responses in a variety of cells, especially macrophages and dendritic cells. Interestingly, much of the oxLDL in circulation is complexed to Abs, and these resulting immune complexes (ICs) are a prominent feature of chronic inflammatory disease, such as atherosclerosis, type-2 diabetes, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis. Levels of oxLDL ICs often correlate with disease severity, and studies demonstrated that oxLDL ICs elicit potent inflammatory responses in macrophages. In this article, we show that bone marrow–derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) incubated with oxLDL ICs for 24 h secrete significantly more IL-1β compared with BMDCs treated with free oxLDL, whereas there was no difference in levels of TNF-α or IL-6. Treatment of BMDCs with oxLDL ICs increased expression of inflammasome-related genes Il1a, Il1b, and Nlrp3, and pretreatment with a caspase 1 inhibitor decreased IL-1β secretion in response to oxLDL ICs. This inflammasome priming was due to oxLDL IC signaling via multiple receptors, because inhibition of CD36, TLR4, and FcγR significantly decreased IL-1β secretion in response to oxLDL ICs. Signaling through these receptors converged on the adaptor protein CARD9, a component of the CARD9–Bcl10–MALT1 signalosome complex involved in NF-κB translocation. Finally, oxLDL IC–mediated IL-1β production resulted in increased Th17 polarization and cytokine secretion. Collectively, these data demonstrate that oxLDL ICs induce inflammasome activation through a separate and more robust mechanism than oxLDL alone and that these ICs may be immunomodulatory in chronic disease and not just biomarkers of severity.

Introduction

Immune complexes (ICs) are formed by specific Ab binding to its soluble Ag. Many sterile inflammatory disorders are characterized by increased serum titers of disease-specific ICs, which can have mechanistic roles in pathogenesis (1, 2). In systemic lupus erythematosus, anti-nuclear and anti-dsDNA ICs bind to glomerular basement membranes and capillary walls, resulting in glomerular nephritis (3). ICs precipitated from the serum of rheumatoid arthritis patients increase the production of TNF-α from PBMCs (4). Atherosclerosis is another disease associated with increased titers of ICs containing Abs directed to oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) (5). In fact, up to 90% of circulating oxLDL can be found in oxLDL ICs (6). Although the majority of studies in atherosclerosis focus on free oxLDL, much less is known about responses to oxLDL ICs. In vitro studies demonstrated that treatment of the human macrophage cell line THP-1 with oxLDL ICs results in increased cell activation, inflammatory cytokine production, and foam cell formation (7). In vivo evidence using FcγR-deficient mice supports the role of IC-mediated modulation of atherosclerosis (8–10). Understanding how these ICs modulate immune responses is important to identify potential therapeutic targets and provide mechanistic insight into IC-associated diseases.

Interestingly, the majority of sterile inflammatory disorders characterized by high serum titers of ICs also have inflammasome hyperactivation (11–13). The inflammasome is a multiprotein oligomer that, when activated, results in secretion of robust levels of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β (14). This innate immune mechanism is important and necessary in the clearance of many bacterial and fungal pathogens (15, 16). However, overactivation of the inflammasome exacerbates or even drives many inflammatory diseases (17). IL-1β blockade is used clinically to treat many IC-related diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus (18, 19). Additionally, it is known that knocking out the inflammasome-related gene Nlrp3 in mice completely abolishes atherosclerosis (20). Yet, although diseases of sterile inflammation are characterized by increased serum IC levels and inflammasome activation, a direct connection has not been made between these two factors.

The current study shows that oxLDL ICs prime the inflammasome in dendritic cells (DCs) via FcγRs, TLR4, and CD36. This inflammasome activation is independent of previously established mechanisms, such as cholesterol crystal formation (20). Taken together, these findings identify a novel and important immunomodulatory role for oxLDL ICs and provide a link between TLR ligand–containing ICs and the inflammasome in sterile inflammatory disorders.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6J (B6), B6N.129-Nlrp3tm1Hhf/J (Nlrp3−/−), B6.129P2 (SJL)-Myd88tm1Defr/J (Myd88−/−), and B6.Cg-Tg (TcraTcrb) 425Cbn/J (OT-II) mice were originally obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and maintained and housed at Vanderbilt University. All mice used in these studies were on the B6 background. Procedures were approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

oxLDL and oxLDL ICs

Human native low-density lipoprotein was purchased from Intracel Resources (Frederick, MD) or Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). oxLDL was made by dialyzing human low-density lipoprotein for 24 h against 0.9 M NaCl at 4°C with two buffer changes, followed by dialysis against 0.9 M NaCl containing 20 μM CuSO4 for 4 h at room temperature. Oxidation was terminated by dialysis against 1 mM EDTA in 1× PBS for 16 h with two buffer changes. Extent of oxidation was determined by TBARS assay (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA). oxLDL ICs were generated by incubating polyclonal rabbit anti-human apoB-100 (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA) with oxLDL at a ratio of 10:1 (500 μg Ab:50 μg oxLDL) overnight at 37°C. Unbound Ab and Ag were removed by size-exclusion filtration. For all experiments, IC concentrations were normalized based on oxLDL concentration to ensure that equal amounts of oxLDL were used in the oxLDL and oxLDL IC conditions. Fab2 fragments were made using the Pierce Fab Fragmentation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. oxLDL-enriched ICs were obtained from the serum of Apoe−/− mice fed a Western diet (21% saturated fat, 0.15% cholesterol) for 12 wk. Whole blood was obtained by retro-orbital bleeding. Serum was incubated with protein G beads for 1 h at room temperature. ICs were eluted from protein G beads, and protein concentration was calculated by BCA assay, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Cell culture

Bone marrow–derived DCs (BMDCs) were generated as previously described (21). Briefly, bone marrow from hind legs was flushed with RPMI 1640 (Corning, Corning, NY), supplemented with 10% FBS (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), 10 mM HEPES (Corning), and 1× Penicillin/Streptomycin/l-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were plated in 100-mm2 petri dishes at 2 × 105 cells per milliliter in tissue culture media containing 20 ng/ml rGM-CSF (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Medium was replaced on days 3 and 6, and cells were harvested on day 9. To make BMDCs from various transgenic strains, femurs were shipped overnight. Femurs from Cd36−/− mice were obtained from Dr. Kathryn Moore (New York University, New York, NY). Cd11ccre/Sykflox/flox and Il1b−/− femurs were obtained from Dr. John R. Lukens. Femurs from Card9−/− mice were received from Dr. Thirumala-Devi Kanneganti (22).

ELISA and Western blotting

IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) ELISAs were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For Western blotting experiments, 1 × 106 BMDCs were treated with the indicated stimuli for 24 h. Cells were lysed with 1× RIPA buffer, and lysates were separated by 4–20% reducing SDS-PAGE. Blots were incubated with anti-mouse caspase-1 mAb (Adipogen, San Diego, CA) or anti-mouse NF-κB p65 Ab (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) overnight at 4°C, followed by IRDye 680RD goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) for 30 min at room temperature. Bands were visualized using the LI-COR Odyssey System.

Immunoprecipitation

CARD9–Bcl10–MALT1 (CBM) complex formation was assessed in whole-cell lysates from BMDCs stimulated for 2 h with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs. Cells were lysed in 1× RIPA buffer, followed by immunoprecipitation with Ab to MALT1, CARD9, or Bcl10 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). Western blot analysis was performed as described above with anti-CARD9, anti-Bcl-10, and anti-MALT1 (Cell Signaling Technology).

Real-time quantitative PCR

BMDCs were treated with the indicated stimuli for 2 h. Total RNA was isolated from cells using Norgen Total RNA Isolation Kits (Norgen Biotek, Thorold, ON, Canada). RNA concentrations were normalized, and RNA was reversed transcribed with a High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY). The reverse transcription product was used for detecting mRNA expression by quantitative real-time PCR using the QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies). The cycling-threshold (CT) value for each gene was normalized to that of the housekeeping gene Ppia, and relative expression was calculated by the change in cycling threshold method (ΔΔCT).

Flow cytometry

To measure FcγR expression, BMDCs were stained on ice for 30 min with CD16.2-allophycocyanin, CD16/32-FITC, CD32–Alexa Fluor 488, or CD64-allophycocyanin in the absence of Fc block. CD16.2, CD16/32, and CD64 Abs were purchased from BD Bioscience and diluted 1:200. Abs were diluted 1:200 in FACS buffer containing HBSS, 1% BSA, 4.17 mM sodium bicarbonate, and 3.08 mM sodium azide. CD32 Ab, a gift from Dr. J. Ravetch (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY), was labeled using an Alexa Fluor 488 Ab Labeling Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were washed and resuspended in 2% PFA for analysis on a MACSQuant seven-color flow cytometer (Miltenyi Biotec), and data were analyzed using FlowJo Single Cell Analysis Version 7.6.5. To measure p-Syk and p-Erk, cells were stimulated with LPS, oxLDL, oxLDL Fab2, or oxLDL IC for 5 or 15 min. Cells were fixed for 10 min in 1× Lyse/Fix Buffer and permeabilized for 30 min using Perm Buffer III (both from BD Biosciences). After permeabilization, cells were Fc blocked for 15 min, followed by staining with CD11b-V450 (BD Biosciences), CD11c-FITC (BD Biosciences) and p-Syk Y525/526- PE (Cell Signaling Technology) or with CD11b-V450, CD11c-PeCy7, and p-ERK1/2-FITC (all from BD Biosciences).

Statistical analyses

Where appropriate, statistical significance was determined using a Student t test. If more than two groups were compared, one-way ANOVA was used. In all cases, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

oxLDL ICs act as a priming signal for the inflammasome

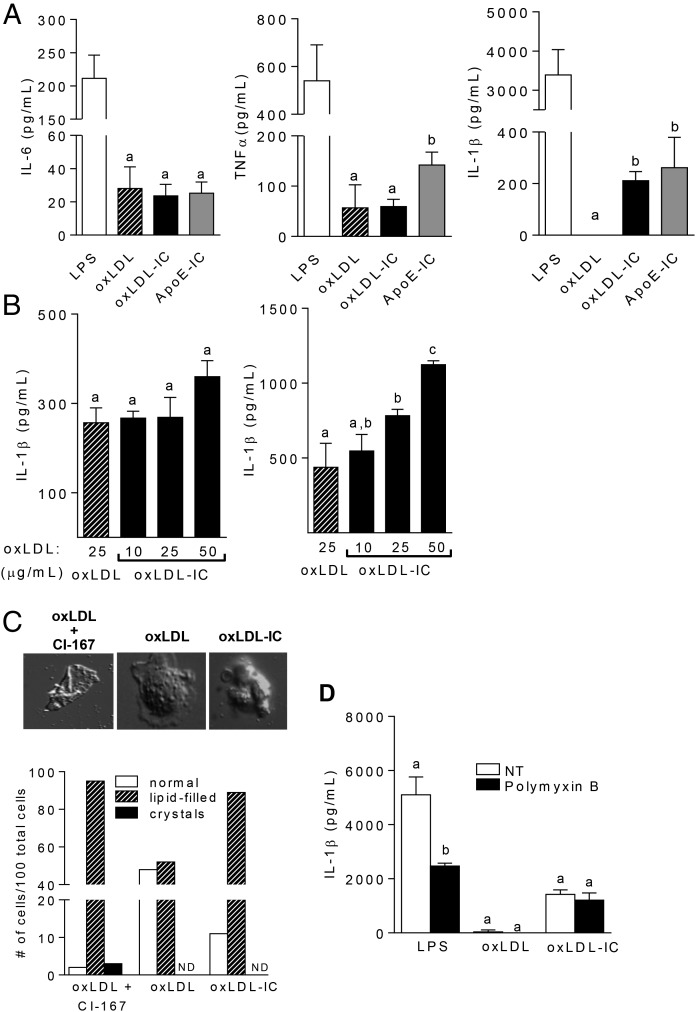

It was demonstrated that ICs containing TLR ligands can enhance inflammatory responses in DCs and macrophages (4, 23). To determine whether the cytokine response to oxLDL ICs was different from that generated with oxLDL alone, we incubated BMDCs with either stimulus for 24 h. Although there were no differences in TNF-α or IL-6 production between the two treatment groups, oxLDL ICs induced robust IL-1β production compared with free oxLDL (Fig. 1A). An additional control of oxLDL-enriched ICs isolated from hyperlipidemic ApoE-deficient mice was added to validate our prepared oxLDL ICs. Similar results were seen with bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs), indicating that this was not a DC-specific response but likely represented a fundamental difference in signaling between oxLDL and oxLDL ICs (Supplemental Fig. 1). Fig. 1A demonstrates that enhanced IL-1β production to laboratory-prepared oxLDL ICs is similar to oxLDL-enriched ICs isolated from hyperlipidemic ApoE-deficient mice and, thus, is likely to be physiologic.

FIGURE 1.

oxLDL ICs prime the inflammasome. BMDCs were treated for 24 h with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs. (A) Cytokine levels in culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. Shown are representative experiments with n ≥3 biological and technical replicates. Unlike letters denote significance (p < 0.01) by Student t test, and error bars indicate SEM. (B) oxLDL ICs were tested for their ability to act as an activating (left panel) or priming (right panel) signal for the inflammasome. Briefly, BMDCs were treated for 3 h with 20 ng/ml LPS, followed by oxLDL or increasing concentrations of oxLDL ICs (based on oxLDL concentration) for an additional 3 h (left). For priming experiments (right panel), BMDCS were treated for 3 h with oxLDL or increasing concentrations of oxLDL ICs, followed by 5 mM ATP for 1 h. Culture supernatants were tested for IL-1β by ELISA. Shown is one representative of three experiments with three mice per experiment. Unlike letters denote significance (p < 0.05) by Student t test, and error bars represent SEM. (C) BMDCs were treated with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs for 3 h or with oxLDL in the presence of the ACAT inhibitor CLI-067 (positive control) for 24 h, and crystal formation was analyzed by polarizing light microscopy. Lipid-filled cells and crystal formation were quantified; representative images are depicted. Shown is one representative of two experiments. Original magnification ×1000. (D) BMDCs were treated with oxLDL ICs in the presence of polymyxin B. Shown is one representative of two experiments. IL-1β in culture supernatants was measured by ELISA. Unlike letters denote significance (p < 0.01) by one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest, and error bars represent SD.

Previous studies showed that oxLDL activates the inflammasome through the formation of cholesterol crystals (20). Given that oxLDL ICs caused enhanced IL-1β production from BMDCs, we hypothesized that oxLDL ICs activate the inflammasome by a similar mechanism. Canonical inflammasome activation is a two-step process that requires a priming signal, typically a pathogen associated molecular pattern, and an activating signal that can be cell damage, ATP, or cholesterol or uric acid crystals (24). The first signal leads to production of pro–IL-1β, and the second signal cleaves procaspase 1 to active caspase 1, allowing it to convert pro–IL-1β to its mature secreted form (14). To determine whether oxLDL ICs served as signal 2, BMDCs were primed with LPS for 3 h, followed by oxLDL (25 μg/ml) or increasing concentrations of oxLDL ICs (containing 10, 25, or 50 μg/ml total oxLDL) for an additional 3 h. As an activating signal, oxLDL ICs elicited IL-1β levels similar to those of oxLDL (Fig. 1B, left panel). To test oxLDL ICs as inflammasome priming signal 1, BMDCs were incubated with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs in increasing concentration for 3 h, followed by ATP for an additional hour. oxLDL ICs elicited significantly more IL-1β than did free oxLDL (Fig. 1B, right panel). oxLDL ICs did not promote IL-1β through formation of cholesterol crystals, because incubation of BMDCs with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs for 3 h was not sufficient for crystal formation (Fig. 1C). Likewise, treatment of BMDCs with the LPS inhibitor polymyxin B prior to exposure to oxLDL or oxLDL ICs had no effect on elicited IL-1β production in BMDCs treated with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs, ruling out the possibility of endotoxin contamination in our IC preparations (Fig. 1D).

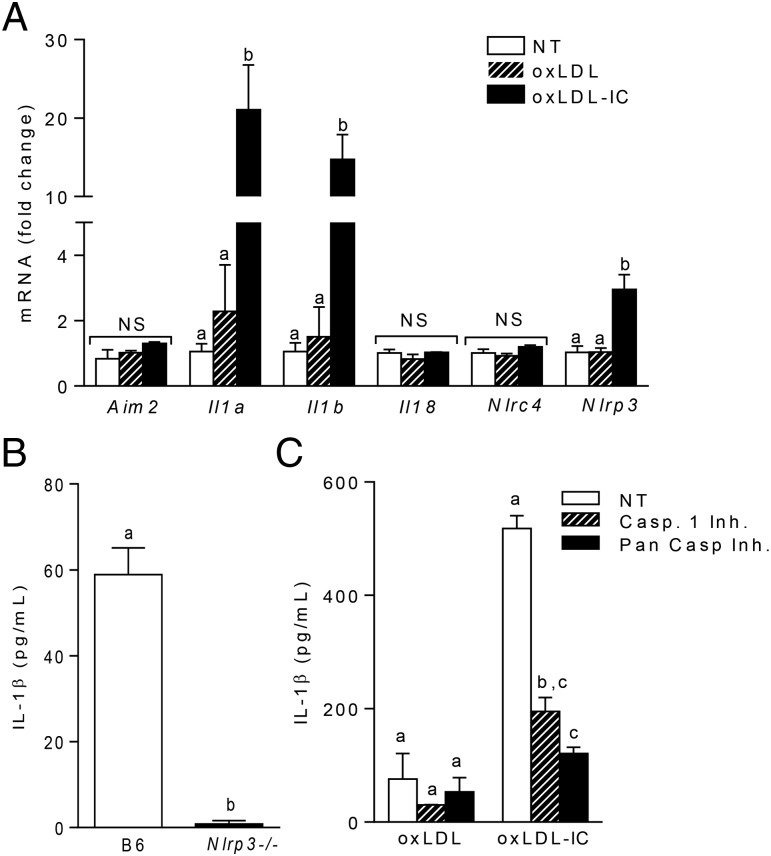

oxLDL IC priming of the inflammasome is Nlrp3 and caspase-1 dependent

Quantitative PCR analysis of RNA from BMDCs treated with oxLDL ICs for 2 h resulted in increased transcription of inflammasome-related genes Il1a, Il1b, and Nlrp3, with no change in inflammasome-related genes Aim2, Nlrc4, and Il18 (Fig. 2A). These data indicate that oxLDL ICs induce Nlrp3 mRNA levels. To support this finding, wild-type and Nlrp3−/− BMDCs were treated with oxLDL ICs for 3 h, followed by ATP for an additional hour, and IL-1β was measured in culture supernatants by ELISA. As expected, the absence of Nlrp3 completely abolished mature IL-1β production (Fig. 2B). Western blot analysis for cleaved caspase-1 and measurement of IL-1β production from BMDCs pretreated with a caspase-1 and pan-caspase inhibitor demonstrate that oxLDL IC–mediated inflammasome activation was caspase-1 dependent (Fig. 2C, Supplemental Fig. 2). Taken together, these data show that oxLDL ICs elicit robust IL-1β production from BMDCs by inducing production of pro–IL-1β and Nlrp3.

FIGURE 2.

Inflammasome priming is Nlrp3 and caspase-1 dependent. (A) BMDCs were stimulated for 2 h with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs. Expression of inflammasome-related genes was measured using real-time RT-PCR and expressed as the 2−ΔΔCT method compared with the no-treatment group (n = 6 mice). Unlike letters denote significance (p < 0.01) by one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest. (B) B6 and Nlrp3−/− BMDCs were treated for 3 h with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs, followed by ATP for 1 h. IL-1β production in culture supernatants was measured by ELISA. Shown is one of three experiments with three mice per experiment. Unlike letters indicate significance (p < 0.01) by the Student t test, and error bars represent SEM. (C) BMDCs were treated as in (B) in the presence or absence of a caspase-1 inhibitor (Z-VAD-FMK) or a pan-caspase inhibitor (Z-YVAD-FMK). IL-1β production in culture supernatants was measured by ELISA. Shown is one of three experiments with three mice per experiment. Unlike letters denote significance (p < 0.01) by one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest, and error bars represent SD.

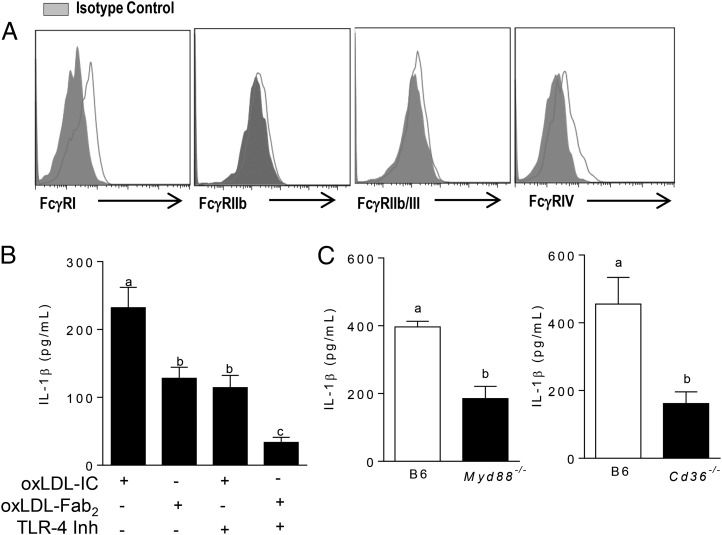

oxLDL ICs prime the inflammasome via FcγR, TLR4, and CD36

FcγRs are the canonical receptors for IgG-containing ICs; however, it is known that oxLDL activates the inflammasome via TLRs and scavenger receptors (25, 26). To test the role of these receptors in oxLDL IC–mediated inflammasome activation, we first measured the baseline expression of FcγRs on BMDCs and found that BMDCs mainly express the activating receptors FcγRI and FcγRIV (Fig. 3A). Next, BMDCs were treated with oxLDL ICs or oxLDL Fab2 complexes (lacking the Fc portion of the Ab and inhibiting interaction with FcγRs) in the presence or absence of the TLR-4 inhibitor CLI-095 for 3 h, followed by ATP for an additional hour. Treatment of BMDCs with the Fab2 complex or the TLR4 inhibitor decreased IL-1β production by ∼50% (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, treatment of BMDCs with both the TLR4 inhibitor and oxLDL Fab2 further decreased IL-1β, suggesting a cooperative role for these receptors (Fig. 3B). The contribution of TLR signaling to oxLDL IC–mediated inflammasome activation was confirmed using Myd88−/− and Cd36−/− BMDCs (Fig. 3C, 3D). These data show that oxLDL IC priming of IL-1β responses in BMDCs is likely a collaboration among FcγRs, TLRs, and CD36.

FIGURE 3.

oxLDL ICs prime the inflammasome using multiple receptors. (A) Surface expression of FcγRs on BMDCs was measured by flow cytometry. Shown is one representative of three experiments. (B) BMDCs were treated with the TLR4 inhibitor CLI-095 prior to treatment with oxLDL IC or oxLDL Fab2 for 3 h and ATP for an additional hour. Culture supernatants were tested for IL-1β by ELISA. Shown is one of three experiments with similar results. Unlike letters denote significance (p < 0.01) by one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest. (C) BMDCs from Myd88−/− (left panel) and Cd36−/− (right panel) mice (n = 3 per group) were treated with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs for 3 h, followed by ATP for an additional hour. IL-1β in culture supernatants was measured by ELISA. Unlike letters denote significance (p < 0.01) by Student t test, and error bars represent SEM.

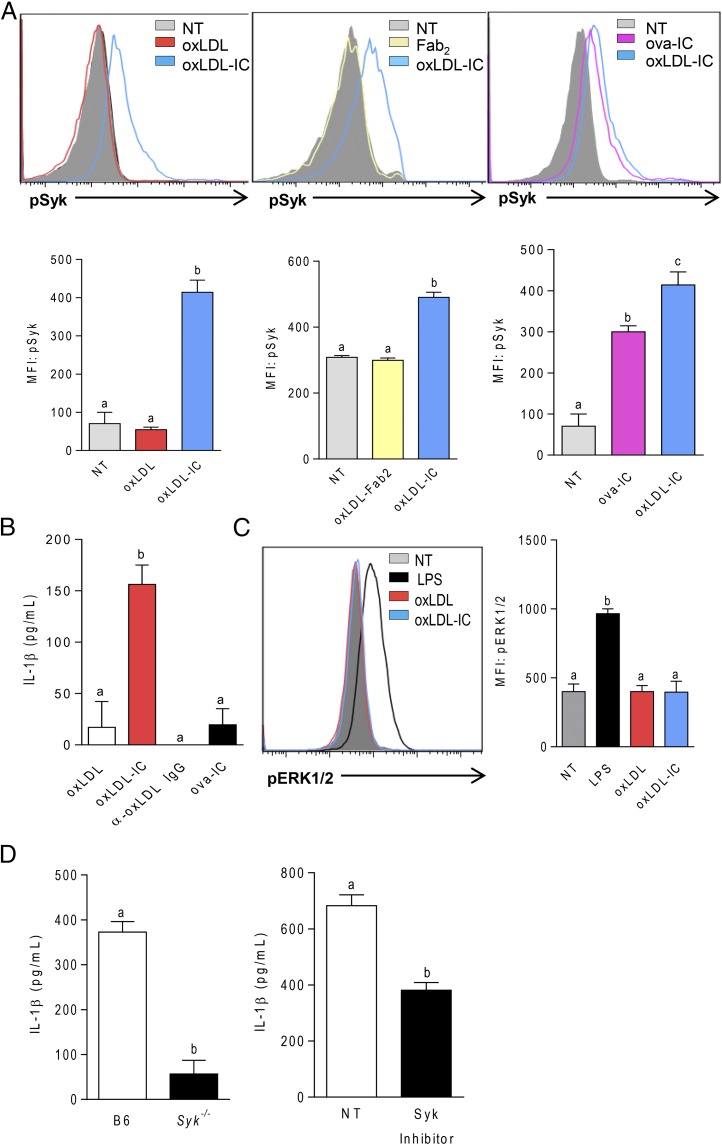

oxLDL IC signaling through FcγRs induces Syk phosphorylation

Given that BMDCs express high levels of activating FcγRs and that treatment of BMDCs with oxLDL Fab2 complex did not result in enhanced levels of IL-1β (Fig. 3B), we hypothesized that oxLDL ICs induce phosphorylation of Syk downstream of activating FcγRs. To test this hypothesis, BMDCs were treated with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs for 15 min, and Syk phosphorylation was measured by phospho-flow cytometry. oxLDL IC treatment of BMDCs increased p-Syk levels, whereas oxLDL did not induce p-Syk (Fig. 4A, left panel). To demonstrate that phosphorylation of Syk was due to ligation of FcγRs and not some off-target effect of oxLDL, BMDCs were treated with oxLDL Fab2 or oxLDL ICs. Again, only oxLDL ICs increased the levels of p-Syk (Fig. 4A, middle panel). As an additional control, BMDCs were treated with OVA-containing ICs (ova-ICs), which caused Syk phosphorylation, although not quite as robustly as did oxLDL ICs (Fig. 4A, right panel). Interestingly, however, although ova-ICs induced p-Syk, they did not elicit the increased IL-1β production seen with oxLDL ICs (Fig. 4B), indicating that p-Syk is not sufficient to increase production of mature IL-1β. Unbound anti-oxLDL also did not elicit IL-1β production from BMDCs, further confirming that the Ag and Ab must be present for this response to occur (Fig. 4B). Because FcγRs can also signal through ERK to promote anti-inflammatory responses, such as IL-10 secretion, we wanted to confirm that oxLDL ICs did not just generally induce FcγR-associated kinases but that the response was more specifically associated with p-Syk. BMDCs treated with oxLDL ICs for 15 min did not result in detectable p-ERK (Fig. 4C). This was supported by the significant decrease in IL-1β production from oxLDL IC–treated BMDCs from Syk−/− mice and in the presence of a Syk inhibitor (Fig. 4D). Collectively, these data support the hypothesis that signaling via p-Syk is necessary, but not sufficient, to induce enhanced inflammasome priming by oxLDL ICs and that concomitant ligation of FcγRs, TLRs, and CD36 is required.

FIGURE 4.

oxLDL ICs enhance IL-1β production via p-Syk. (A) BMDCs were incubated with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs, oxLDL-Fab2, oxLDL ICs, or ova-ICs for 15 min. Syk phosphorylation was measured by phospho-flow cytometry. Representative line graphs are shown (upper panels). n = 3 mice per group. Unlike letters indicate significance (p < 0.001) by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest, and error bars represent SEM. (B) Cells were treated with oxLDL, anti-oxLDL, oxLDL ICs, or ova-ICs for 3 h, followed by ATP for an additional hour. IL-1β in culture supernatants was measured by ELISA. Shown is one representative of three separate experiments. Unlike letters denote significance by one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest, and error bars indicate the SD. (C) BMDCs were incubated with LPS oxLDL or oxLDL ICs for 15 min. Erk phosphorylation was measured by phospho-flow cytometry. A representative line graph is shown (left panel) and results are quantified by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI; right panel). n = 3 separate experiments. Unlike letters indicate significance (p < 0.001) by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest, and error bars represent SEM. (D) B6 or Syk−/− BMDCs (left panel) or B6 BMDCs plus or minus the Syk inhibitor Bay61-3606 (right panel) were incubated with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs for 3 h, followed by ATP for 1 h. n = 3 separate experiments. Unlike letters indicate significance (p < 0.05) by the Student t test, and error bars represent SEM.

oxLDL IC–mediated inflammasome priming is CARD9 dependent

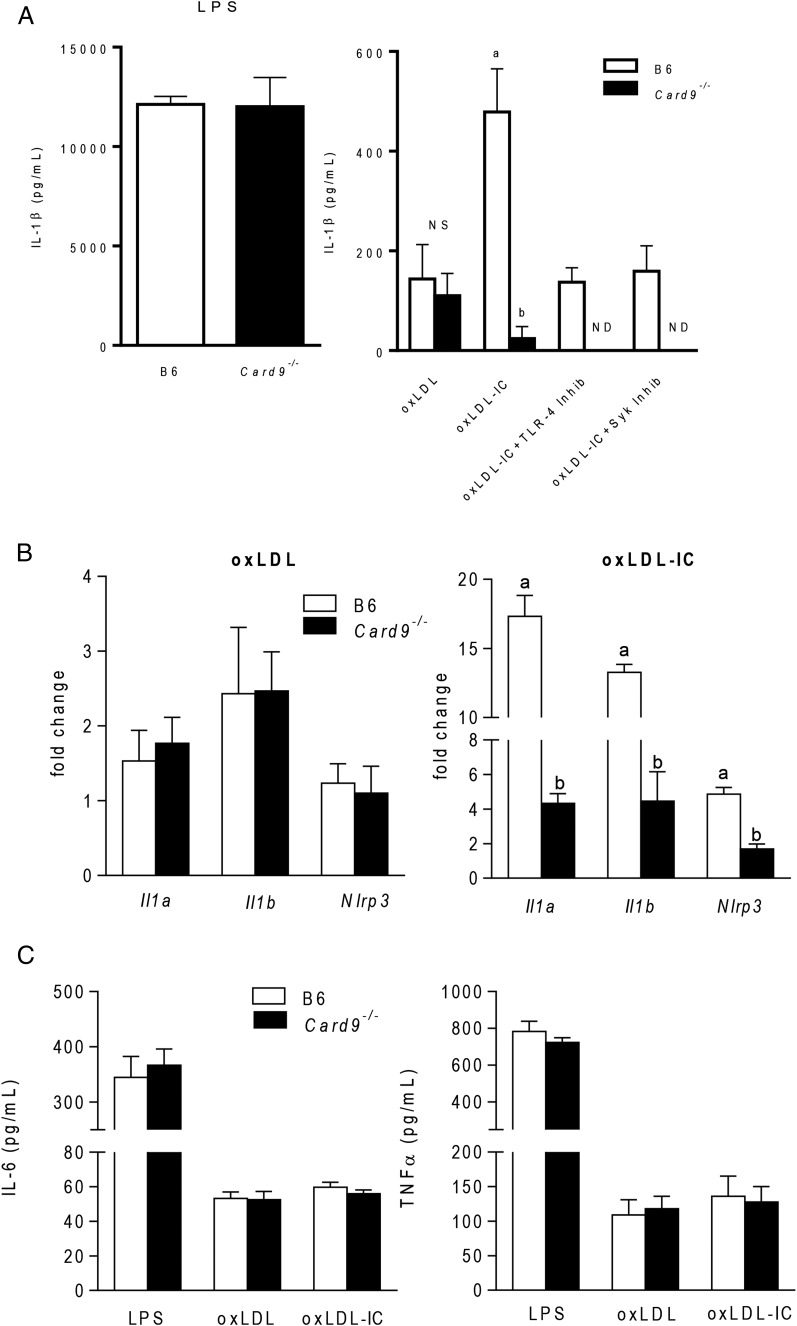

CARD9 is an adaptor protein component of the CBM complex, a signalosome involved in the translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus and subsequent production of proinflammatory cytokines (27). Previous studies showed that ITAM and TLR signaling pathways converge on CARD9, and CARD9-dependent inflammasome activation and IL-1β production are critical in models of fungal pathogenesis (28–30). To determine whether CARD9 is necessary for oxLDL IC–mediated inflammasome responses, wild-type and Card9−/− BMDCs were treated with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs for 3 h, followed by ATP for an additional hour in the presence or absence of a TLR4 or Syk inhibitor. CARD9 deficiency had no effect on IL-1β responses to LPS priming (Fig. 5A, left panel) or oxLDL-mediated IL-1β production (Fig. 5A, right panel). However, absence of CARD9 resulted in significant decreases in IL-1β secretion in response to oxLDL IC priming (Fig. 5A, right panel). As seen previously, treatment of B6 BMDCs with a TLR4 or Syk inhibitor reduced IL-1β levels to those of oxLDL alone, indicating that TLR4 and FcγRs are necessary for IC-enhanced cytokine production. Supporting the convergence of these signals on CARD9, pretreatment of Card9−/− BMDCs with TLR4 or Syk inhibitors completely abolished IL-1β production. In addition, CARD9 deficiency had no effect on oxLDL-induced expression of mRNA for Il1a, Il1b, or Nlrp3 (Fig. 5B, left panel) but decreased levels of mRNA for these genes in response to oxLDL ICs (Fig. 5B, right panel). Absence of CARD9 had no effect on the level of IL-6 or TNF-α (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these data indicate that oxLDL ICs prime the IL-1β response by signaling through multiple receptors and converging on the adaptor protein CARD9.

FIGURE 5.

oxLDL IC inflammasome priming is CARD9 dependent. (A) B6 and Card9−/− BMDCs were incubated with LPS, oxLDL, or oxLDL ICs in the presence or absence of a TLR4 or Syk inhibitor for 3 h, followed by ATP for an additional hour. IL-1β in culture supernatants was measured by ELISA (n = 3 mice per group). Unlike letters denote significance (p < 0.001) by the Student t test, and error bars indicate SEM. (B) B6 and Card9−/− BMDCs were incubated with oxLDL (left panel) or oxLDL ICs (right panel) for 2 h. Expression of inflammasome-related genes was measured using real-time RT-PCR and expressed as 2−ΔΔCT compared with the no-treatment group (n = 3 mice per group). Unlike letters denote significance (p < 0.01) by one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest. (C) BMDCs from B6 and Card9−/− mice were incubated with LPS, oxLDL, or oxLDL ICs for 24 h. TNF-α and IL-6 in culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. n = 3 mice per group; error bars represent SEM.

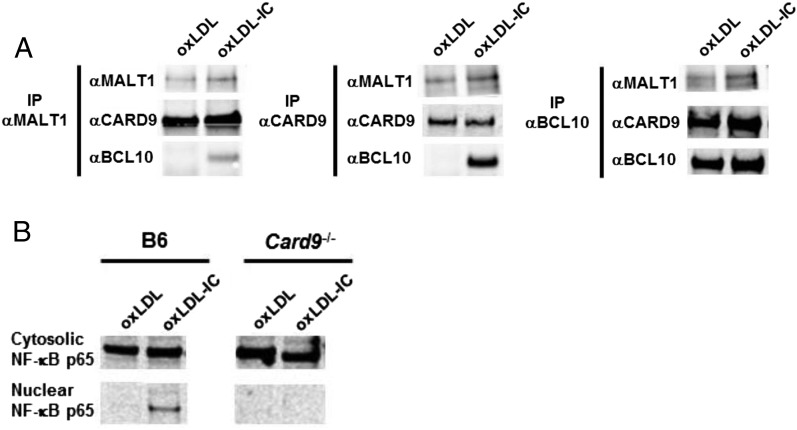

oxLDL ICs induce CBM complex formation and NF-κB translocation

To test whether oxLDL ICs elicited transcription of Nlrp3 genes and IL-1β production by promoting formation of the CBM complex, BMDCs were treated for 2 h with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs. Immunoprecipitation experiments with Abs to MALT1 and CARD9 showed that the entire CBM complex was only pulled down when cells were treated with oxLDL ICs and not oxLDL alone (Fig. 6A, left and middle panels). When lysates were immunoprecipitated with an Ab to Bcl10, the entire complex was pulled down in both treatment groups; however, there were much higher levels of MALT1 and CARD9 in the BMDCs treated with oxLDL ICs (Fig. 6A, right panel). Because CBM complex formation was found to promote nuclear translocation of NF-κB, we measured NF-κB p65 levels in the cytosol and nucleus of BMDCs treated with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs. oxLDL ICs induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB, and this translocation did not occur when the experiment was repeated in Card9−/− BMDCs (Fig. 6B). These results support Nlrp3 gene transcription through formation of the CBM complex.

FIGURE 6.

oxLDL ICs cause CBM formation. (A) BMDCs were treated with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs for 2 h. Immunoprecipitation using Abs to MALT1, CARD9, and BCL10 was performed on whole-cell lysates, followed by Western blot analysis. Shown is one representative of three similar experiments. (B) BMDCs were treated with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs for 2 h. Lysates were separated into nuclear and cytosolic fractions, followed by Western blotting for NF-κB p65. Shown is one of three representative experiments.

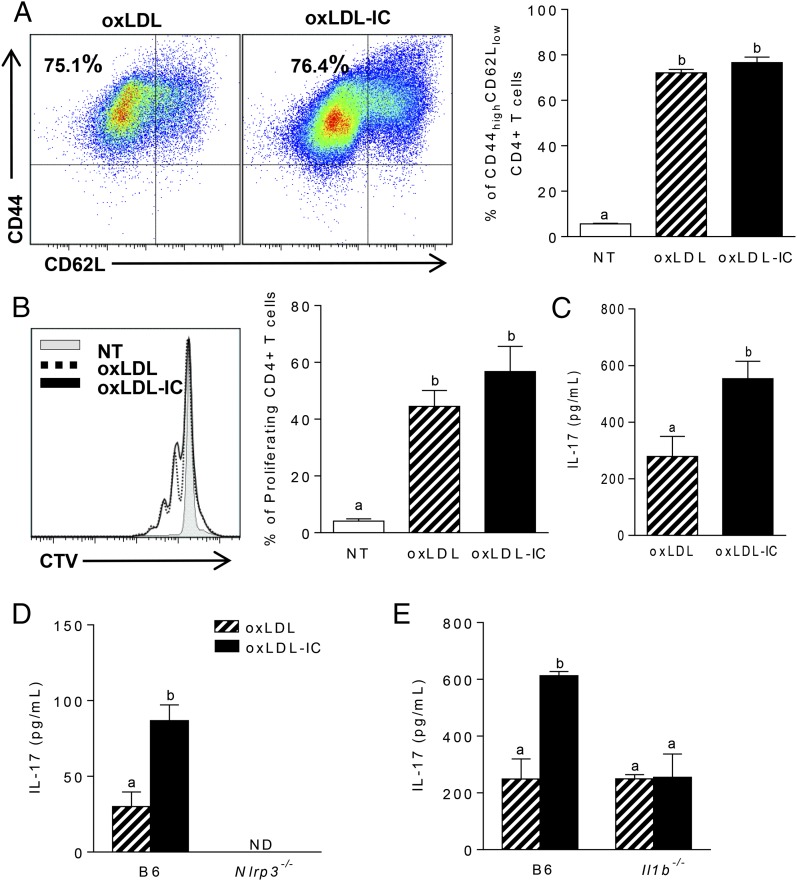

oxLDL IC–mediated IL-1β enhances IL-17 production from T cells

Given that IL-1β is an important cytokine involved in Th17 polarization, we hypothesized that oxLDL IC–mediated inflammasome activation would modulate T cell responses. To test whether increased oxLDL IC–induced IL-1β production by BMDCs modulated Ag-specific T cell responses, BMDCs were treated for 24 h with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs and then cocultured with bead-purified splenic OT-II CD4+ T cells in the presence of OVA323–339 peptide for an additional 72 h. Although there were no differences in T cell activation (Fig. 7A) or proliferation (Fig. 7B), analysis of cytokines in culture supernatants by ELISA showed that oxLDL IC treatment of BMDCs induced increased production of IL-17 from T cells compared with oxLDL alone (Fig. 7C). When this experiment was repeated using Nlrp3- or Il1b-deficient BMDCs, IL-17 production was reduced to levels observed with oxLDL alone, confirming that oxLDL ICs enhance the innate and adaptive immune response (Fig. 7D, 7E).

FIGURE 7.

oxLDL-mediated IL-1β production by BMDCs enhances Ag-specific Th17 responses. (A–C) A total of 104 BMDCs was treated with oxLDL or oxLDL ICs for 24 h, followed by coculture with 105 MACS-sorted OT-II CD4+ T cells and OVA peptide (50 μg/ml) for 72 h. (A) T cell activation was measured by expression of CD44 and CD62L on CD4+TCRβ+ cells using flow cytometry. Representative dot plots are shown (left panel), and percentages of CD44hiCD62Llo cells are quantified (right panel). (B) T cell proliferation was determined by CellTrace Violet dilution. Shown is a representative line graph (left graph); the percentage of proliferating cells is quantified (right panel). (C) IL-17 was measured in T cell culture supernatants by ELISA. Three mice were used per group, and the experiment was repeated three times. Unlike letters denote significance (p < 0.05) by the Student t test, and error bars represent SEM. The experiment described was repeated using Nlrp3−/− (D) and Il1b−/− (E) BMDCs. IL-17 in culture supernatants was measured by ELISA. Unlike letters denote significance (p < 0.01) by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest, and error bars represent SEM (n = 3 mice per group).

Discussion

Most studies of the immune response to oxLDL examined free oxLDL or Ab to oxLDL; however, only a few examined the importance of oxLDL-containing ICs (31–33). Although direct evidence of their role in cardiovascular disease pathogenesis is lacking, a number of studies provided data suggesting that oxLDL ICs have disease-modifying potential. For example, Apoe−/− and Ldlr−/− mice deficient in activating FcγRI/III have decreased atherosclerosis, whereas atherosclerosis-susceptible mice lacking the inhibitory FcγRIIb show strain-dependent increased or decreased atherosclerosis (8, 9, 34). Interestingly, Kyaw et al. (35, 36) elegantly showed that IgG plays an inflammatory role, whereas IgM inhibits the development of atherosclerosis. Although these studies support a pathogenic potential for oxLDL ICs, a direct mechanistic understanding of how these ICs may modulate disease progression is lacking. Furthermore, aside from work showing that oxLDL ICs bind FcγRI on a human macrophage cell line and induce the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, very little is understood about how oxLDL ICs affect immune responses in potential inflammatory cells (33). Our studies show that oxLDL ICs act directly on dendritic cells (and BMDMs), leading to upregulation of activation markers and differential cytokine production compared with oxLDL alone. This finding is novel and important because DCs provide a link between the innate and adaptive immune response.

Our current investigation shows that oxLDL ICs act as priming signals for IL-1β production and Nlrp3 inflammasome activation via FcγR, CD36, and TLR4. Studies by Sheedy et al. (37) demonstrated that oxLDL can be a second, activating signal for the inflammasome through a TLR4/TLR6/CD36 heterotrimer complex. This was largely facilitated by formation of cholesterol crystals and resulting lysosomal disruption. The investigators went on to suggest that oxLDL could act as both a priming and activating signal for the inflammasome via TLR ligation and cholesterol crystal formation, respectively. Given that high levels of IL-1β were observed following 24 h of treatment with oxLDL ICs (Fig. 1A), it is likely that oxLDL ICs are able to act as a priming and activating signal for the inflammasome even more robustly than free oxLDL. oxLDL IC priming of the inflammasome appears to be due to receptor-specific signaling, leading to production of pro–IL-1β, but the primary mechanism does not involve cholesterol crystal formation. These data are supported by the observations that oxLDL ICs enhance IL-1β production above oxLDL when used as a priming signal for the inflammasome; IL-1β production is partially decreased by removing CD36, TLR4, or FcγR; and oxLDL ICs increase transcription of the inflammasome-related genes Il1a, Il1b, and Nlrp3. It is possible that oxLDL ICs also act as an activating signal in vivo by inducing cell death via pyroptosis, resulting in the release of cellular contents, including ATP, and by cholesterol crystal formation and lysosomal disruption following uptake via FcγRs.

The aforementioned study and others showed that oxLDL induces inflammasome-mediated IL-1β production from BMDMs; however, we were not able to detect IL-1β in BMDM supernatants under our treatment conditions (Supplemental Fig. 1) (37–39). This discrepancy is likely a time- and dose-dependent issue. Jiang et al. (38) observed IL-1β production from BMDMs treated with increasing concentrations of oxLDL (25–200 μg/ml) for 12 h, choosing to do the majority of the experiments with 200 μg/ml oxLDL. Similarly, Liu et al. (39) used high concentrations of oxLDL (50–200 μg) for 24 h. Although these high concentrations of oxLDL elicit robust responses from innate immune cells, they are at the extreme upper limit of being physiologically relevant. We chose to use 10 μg/ml oxLDL for our studies to more closely mimic conditions in vivo. In addition, the longer incubation periods used during these studies allowed time for the formation of cholesterol crystals, which is the primary mechanism by which oxLDL activates the inflammasome. Our studies used a much shorter 3-h incubation with the Ags to tease apart the different mechanisms by which oxLDL and oxLDL ICs induced IL-1β production.

A recent study from Duffy et al. (40) showed that IgG-opsonized inactivated Francisella tularensis was able to activate the inflammasome in an FcγR/TLR-dependent fashion. The ability of ICs to enable cross-talk between these two receptors is likely facilitated by the tight clustering of TLRs and FcγRs in glycoprotein microdomains (41). In addition, fungal Ags, such as those from Candida albicans, were found to activate the inflammasome by binding to several ITAM-associated C-type lectins, including dectin-1, dectin-2, and mincle (28). Binding of these Ags leads to recruitment and phosphorylation of Syk and further signal propagation, resulting in formation of a CBM complex and nuclear translocation of NF-κB (28). Our current study shows that, similar to septic inflammation, oxLDL ICs use the CBM signaling pathway during sterile inflammation to enhance IL-1β responses in BMDCs and, by extension, IL-17 production by Ag-specific T cells. Surprisingly, increased CARD9-mediated NF-κB translocation did not result in increased production of TNF-α or IL-6, both of which are known transcriptional targets of NF-κB. There have been a handful of studies implicating CARD9 in increased ΤΝF-α production in models of fungal pathogenesis and no report connecting CARD9 signaling and IL-6 production (42–44). The studies examining CARD9-mediated TNF-α production all required dectin-1 ligation. It is possible that the FcγR–CARD9 pathway is distinct from the dectin-1–CARD9 pathway and involves a phosphorylation or ubiquitination event that gives NF-κB greater affinity for the IL-1 promoter. Because we only examined TNF-α levels at 24 h, it is also possible that levels are increased at earlier time points. Greater understanding of the FcγR–CARD9 pathway in sterile inflammation is an area of continued interested and warrants further study.

In stark contrast to our study, Janczy et al. (45) recently reported that IgG ICs inhibit inflammasome activation by LPS in BMDMs. Specifically, BMDMs primed with LPS in the presence of ICs containing sheep RBC, OVA, or C. albicans resulted in decreased IL-1β production compared with priming with LPS alone (45). We observed that, similar to BMDCs, BMDMs also exhibit enhanced IL-1β secretion in response to oxLDL ICs (Supplemental Fig. 1). One possible explanation for the discrepancy between this work and our current study is that the specific Ag contained in the IC plays an important role in the immune response. Our data show that oxLDL ICs activate the inflammasome by binding to multiple receptors on DCs, including TLR4, CD36, and FcγR. There is no precedent for sheep RBC or OVA binding to pattern recognition receptors and, although C. albicans can bind TLR2 and TLR4, LPS was shown to upregulate the expression of the inhibitory receptor FcγRIIb on the surface of cells, downregulating inflammation (46). Therefore, it is possible that pretreatment with LPS decreases IC-mediated inflammatory cytokines due to increased FcγRIIb expression. Given that high levels of LPS are not found in sterile inflammation, our experimental system may be more clinically relevant to diseases such as atherosclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis associated with ICs containing molecules that can signal through TLRs and FcγRs.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates that oxLDL ICs have the potential to enhance inflammation by priming the Nlrp3 inflammasome, and molecular mechanisms share signaling pathways with pathogens and/or ICs formed during bacterial infections (28, 40). Collectively, the data suggest that, although such responses may be beneficial during acute septic inflammation, IC-mediated production of cytokines, such as IL-1β, during chronic sterile inflammation is likely pathogenic. These findings identify an important contribution of oxLDL ICs to innate and adaptive immune responses that go beyond their previous recognition as biomarkers for atherosclerosis disease severity.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by grants from the Lupus Research Institute, the National Institutes of Health (Grant R21AR066971), and the Veterans Administration (Grant I01BX002968) (all to A.S.M.). J.P.R. was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants T32 AR059039 and F31 HL128040.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

- B6

- C57BL/6J

- BMDC

- bone marrow–derived DC

- BMDM

- bone marrow–derived macrophage

- CBM

- CARD9–Bcl10–MALT1

- DC

- dendritic cell

- IC

- immune complex

- Myd88−/−

- B6.129P2 (SJL)-Myd88tm1Defr/J

- Nlrp3−/−

- B6N.129-Nlrp3tm1Hhf/J

- ova-IC

- OVA-containing IC

- oxLDL

- oxidized low-density lipoprotein.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Fernandez-Madrid F., Mattioli M. 1976. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA): immunologic and clinical significance. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 6: 83–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao X., Okeke N. L., Sharpe O., Batliwalla F. M., Lee A. T., Ho P. P., Tomooka B. H., Gregersen P. K., Robinson W. H. 2008. Circulating immune complexes contain citrullinated fibrinogen in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 10: R94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krishnan M. R., Wang C., Marion T. N. 2012. Anti-DNA autoantibodies initiate experimental lupus nephritis by binding directly to the glomerular basement membrane in mice. Kidney Int. 82: 184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sokolove J., Zhao X., Chandra P. E., Robinson W. H. 2011. Immune complexes containing citrullinated fibrinogen costimulate macrophages via Toll-like receptor 4 and Fcγ receptor. Arthritis Rheum. 63: 53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salonen J. T., Ylä-Herttuala S., Yamamoto R., Butler S., Korpela H., Salonen R., Nyyssönen K., Palinski W., Witztum J. L. 1992. Autoantibody against oxidised LDL and progression of carotid atherosclerosis. Lancet 339: 883–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopes-Virella M. F., Virella G., Orchard T. J., Koskinen S., Evans R. W., Becker D. J., Forrest K. Y. 1999. Antibodies to oxidized LDL and LDL-containing immune complexes as risk factors for coronary artery disease in diabetes mellitus. Clin. Immunol. 90: 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Virella G., Atchley D., Koskinen S., Zheng D., Lopes-Virella M. F., DCCT/EDIC Research Group 2002. Proatherogenic and proinflammatory properties of immune complexes prepared with purified human oxLDL antibodies and human oxLDL. Clin. Immunol. 105: 81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendez-Fernandez Y. V., Stevenson B. G., Diehl C. J., Braun N. A., Wade N. S., Covarrubias R., van Leuven S., Witztum J. L., Major A. S. 2011. The inhibitory FcγRIIb modulates the inflammatory response and influences atherosclerosis in male apoE(−/−) mice. Atherosclerosis 214: 73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernández-Vargas P., Ortiz-Muñoz G., López-Franco O., Suzuki Y., Gallego-Delgado J., Sanjuán G., Lázaro A., López-Parra V., Ortega L., Egido J., Gómez-Guerrero C. 2006. Fcgamma receptor deficiency confers protection against atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Circ. Res. 99: 1188–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao M., Wigren M., Dunér P., Kolbus D., Olofsson K. E., Björkbacka H., Nilsson J., Fredrikson G. N., Bjo H. 2010. FcgammaRIIB inhibits the development of atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 184: 2253–2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruscitti P., Cipriani P., Di Benedetto P., Liakouli V., Berardicurti O., Carubbi F. 2015. Monocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and type 2 diabetes mellitus display an increased production of interleukin (IL)-1β via the nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat containing family pyrin 3 (NLRP3)-inflammasome activation: a possible implication for therapeutic decision in these patients. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 182: 35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choulaki C., Papadaki G., Repa A., Kampouraki E., Kambas K., Ritis K., Bertsias G., Boumpas D. T., Sidiropoulos P. 2015. Enhanced activity of NLRP3 inflammasome in peripheral blood cells of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17: 257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pontillo A., Reis E. C., Liphaus B. L., Silva C. A., Carneiro-sampaio M. 2015. Inflammasome polymorphisms in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity 48: 434–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroder K., Tschopp J. 2010. The inflammasomes. Cell 140: 821–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hise A. G., Tomalka J., Ganesan S., Patel K., Hall B. A., Brown G. D., Fitzgerald K. A. 2009. An essential role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in host defense against the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe 5: 487–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Body-malapel M., Amer A., Park J., Kanneganti T., Nesrin O., Franchi L., Whitfield J., Barchet W., Colonna M., Vandenabeele P., et al. 2006. Bacterial RNA and small antiviral compounds. Nature 440: 233–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang C. A., Chiang B. L. 2015. Inflammasomes and human autoimmunity : a comprehensive review. J. Autoimmun. 61: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aytac S., Batu E. D., Unal S., Bilinger Y., Cetin M., Tuncer M., Gumruk F., Ozen S. 2016. Macrophage activation syndrome in children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 36: 1421–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleischmann R. M., Tesser J., Schiff M. H., Schechtman J., Burmester G., Bennett R., Modafferi D., Zhou L., Bell D., Appleton B. 2006. Safety of extended treatment with anakinra in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65: 1006–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duewell P., Kono H., Rayner K. J., Sirois C. M., Vladimer G., Bauernfeind F. G., Schnurr M., Espevik T., Lien E., Fitzgerald K. A., et al. 2010. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 464: 1357–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lutz M. B., Kukutsch N., Ogilvie A. L., Rössner S., Koch F., Romani N., Schuler G. 1999. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods 223: 77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shornick L. P., De Togni P., Mariathasan S., Goellner J., Strauss-Schoenberger J., Karr R. W., Ferguson T. A., Chaplin D. D. 1996. Mice deficient in IL-1beta manifest impaired contact hypersensitivity to trinitrochlorobenzone. J. Exp. Med. 183: 1427–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Means T. K., Latz E., Hayashi F., Murali M. R., Golenbock D. T., Luster A. D. 2005. Human lupus autoantibody-DNA complexes activate DCs through cooperation of CD32 and TLR9. J. Clin. Invest. 115: 407–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stutz A., Golenbock D. T., Latz E. 2009. Inflammasomes: too big to miss. J. Clin. Invest. 119: 3502–3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nimmerjahn F., Ravetch J. V. 2006. Fcgamma receptors: old friends and new family members. Immunity 24: 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perrin-Cocon L., Coutant F., Agaugué S., Deforges S., André P., Lotteau V. 2001. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein promotes mature dendritic cell transition from differentiating monocyte. J. Immunol. 167: 3785–3791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hara H., Ishihara C., Takeuchi A., Imanishi T., Xue L., Morris S. W., Inui M., Takai T., Shibuya A., Saijo S., et al. 2007. The adaptor protein CARD9 is essential for the activation of myeloid cells through ITAM-associated and Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 8: 619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gross O., Poeck H., Bscheider M., Dostert C., Hannesschläger N., Endres S., Hartmann G., Tardivel A., Schweighoffer E., Tybulewicz V., et al. 2009. Syk kinase signalling couples to the Nlrp3 inflammasome for anti-fungal host defence. Nature 459: 433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saijo S., Iwakura Y. 2011. Dectin-1 and Dectin-2 in innate immunity against fungi. Int. Immunol. 23: 467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson M. J., Osorio F., Rosas M., Freitas R. P., Schweighoffer E., Gross O., Verbeek J. S., Ruland J., Tybulewicz V., Brown G. D., et al. 2009. Dectin-2 is a Syk-coupled pattern recognition receptor crucial for Th17 responses to fungal infection. J. Exp. Med. 206: 2037–2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopes-Virella M. F., Hunt K. J., Baker N. L., Lachin J., Nathan D. M., Virella G., Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group 2011. Levels of oxidized LDL and advanced glycation end products-modified LDL in circulating immune complexes are strongly associated with increased levels of carotid intima-media thickness and its progression in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 60: 582–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopes-Virella M. F., Virella G. 2013. Pathogenic role of modified LDL antibodies and immune complexes in atherosclerosis. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 20: 743–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saad A. F., Virella G., Chassereau C., Boackle R. J., Lopes-Virella M. F. 2006. OxLDL immune complexes activate complement and induce cytokine production by MonoMac 6 cells and human macrophages. J. Lipid Res. 47: 1975–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng H. P., Zhu X., Harmon E. Y., Lennartz M. R., Nagarajan S. 2015. Reduced atherosclerosis in apoE-inhibitory FcγRIIb-deficient mice is associated with increased anti-inflammatory responses by T cells and macrophages. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 35: 1101–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kyaw T., Tay C., Krishnamurthi S., Kanellakis P., Agrotis A., Tipping P., Bobik A., Toh B. H. 2011. B1a B lymphocytes are atheroprotective by secreting natural IgM that increases IgM deposits and reduces necrotic cores in atherosclerotic lesions. Circ. Res. 109: 830–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kyaw T., Tay C., Khan A., Dumouchel V., Cao A., To K., Kehry M., Dunn R., Agrotis A., Tipping P., et al. 2010. Conventional B2 B cell depletion ameliorates whereas its adoptive transfer aggravates atherosclerosis. J. Immunol. 185: 4410–4419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheedy F. J., Grebe A., Rayner K. J., Kalantari P., Ramkhelawon B., Carpenter S. B., Becker C. E., Ediriweera H. N., Mullick A. E., Golenbock D. T., et al. 2013. CD36 coordinates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by facilitating intracellular nucleation of soluble ligands into particulate ligands in sterile inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 14: 812–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang Y., Wang M., Huang K., Zhang Z., Shao N., Zhang Y., Wang W., Wang S. 2012. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces secretion of interleukin-1β by macrophages via reactive oxygen species-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 425: 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu W., Yin Y., Zhou Z. 2014. OxLDL-induced IL-1beta secretion promoting foam cells formation was mainly via CD36 mediated ROS production leading to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Inflamm. Res. 63: 33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duffy E. B., Periasamy S., Hunt D., Drake J. R., Harton J. A. 2016. FcγR mediates TLR2- and Syk-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation by inactivated Francisella tularensis LVS immune complexes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 100: 1335–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shang L., Daubeuf B., Triantafilou M., Olden R., Dépis F., Raby A., Herren S., Dos Santos A., Malinge P., Dunn-siegrist I., et al. 2014. Selective antibody intervention of Toll-like receptor 4 activation through Fc γreceptor tethering. J. Biol. Chem. 289: 15309–15318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pedroza L. A., Kumar V., Sanborn K. B., Mace E. M., Niinikoski H., Nadeau K., Vasconcelos Dde. M., Perez E., Jyonouchi S., Jyonouchi H., et al. 2012. Autoimmune regulator (AIRE) contributes to Dectin-1-induced TNF-α production and complexes with caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 9 (CARD9), spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk), and Dectin-1. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129: 464–472.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whibley N., Jaycox J. R., Reid D., Garg A. V., Taylor J. A., Clancy C. J., Nguyen M. H., Biswas P. S., Mcgeachy M. J., Brown G. D., Gaffen S. L. 2016. Delinking CARD9 and IL-17: CARD9 protects against Candida tropicalis infection through a TNF-α dependent, IL-17-independent mechanism. J. Immunol. 195: 3781–3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goodridge H. S., Shimada T., Wolf A. J., Hsu Y. S., Becker C. A., Lin X., Underhill D. M. 2009. Differential use of CARD9 by Dectin-1 in macrophages and dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 182: 1146–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janczy J. R., Ciraci C., Haasken S., Iwakura Y., Olivier A. K., Cassel S. L., Sutterwala F. S. 2014. Immune complexes inhibit IL-1 secretion and inflammasome activation. J. Immunol. 193: 5190–5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y., Liu S., Liu J., Zhang T., Shen Q., Yu Y., Cao X. 2009. Immune complex/Ig negatively regulate TLR4-triggered inflammatory response in macrophages through Fc gamma RIIb-dependent PGE2 production. J. Immunol. 182: 554–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.