Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is one of the major causes of death and disability worldwide. No effective treatment has been identified from clinical trials. Compelling evidence exists that treatment with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) exerts a substantial therapeutic effect after experimental brain injury. In addition to their soluble factors, therapeutic effects of MSCs may be attributed to their generation and release of exosomes. Exosomes are endosomal origin small-membrane nano-sized vesicles generated by almost all cell types. Exosomes play a pivotal role in intercellular communication. Intravenous delivery of MSC-derived exosomes improves functional recovery and promotes neuroplasticity in rats after TBI. Therapeutic effects of exosomes derive from the exosome content, especially microRNAs (miRNAs). miRNAs are small non-coding regulatory RNAs and play an important role in posttranscriptional regulation of genes. Compared with their parent cells, exosomes are more stable and can cross the blood-brain barrier. They have reduced the safety risks inherent in administering viable cells such as the risk of occlusion in microvasculature or unregulated growth of transplanted cells. Developing a cell-free exosome-based therapy may open up a novel approach to enhancing multifaceted aspects of neuroplasticity and to amplifying neurological recovery, potentially for a variety of neural injuries and neurodegenerative diseases. This review discusses the most recent knowledge of exosome therapies for TBI, their associated challenges and opportunities.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury, exosomes, microRNAs, mesenchymal stem cells, treatment, neuroplasticity, cell therapy

Unmet Need for Treatment for Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

TBI is one of the major causes of death and disability worldwide. An estimated 1.7 million people sustain TBI each year in the United States, and more than 5 million people are coping with disabilities from TBI at an annual cost of more than $76 billion. Despite improved supportive and rehabilitative care of TBI patients, no effective pharmacological treatments are available for reducing TBI mortality and improving functional recovery because all phase II/III TBI clinical trials have failed. Emerging preclinical data indicate that restorative therapies targeting multiple parenchymal cells including cerebral endothelial cells, neural stem/progenitor cells and oligodendrocyte progenitor cells enhance TBI-induced angiogenesis, neurogenesis, axonal sprouting, and oligodendrogenesis, respectively (Xiong et al., 2009). These interacting neuroplastic events in concert improve neurological function after TBI. There is a compelling need to develop novel therapeutics specifically designed to stimulate neuroplasticity which subsequently promote neurological recovery after TBI.

Mechanisms Underlying Cell Therapy for TBI

Cell therapies including bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have shown promise in the field of regenerative medicine for treating various diseases including TBI. Exogenously administered MSCs selectively target injured tissue (homing), interact with brain parenchymal cells, reduce expression of axonal inhibitory molecules, stimulate the production of growth and plasticity positive factors, which increase neurite outgrowth, promote neurorestoration and recovery of neurological function after brain injuries (Chopp and Li, 2002). Administration of MSCs through different routes (intraarterial, intravenous, and intracerebral) exhibit robust therapeutic effects in experimental TBI. However, there are some disadvantages for each route. For example, relatively few MSCs can be injected intracranially; intraarterial injection of MSCs can cause brain ischemia; and intravenous injection results in body-wide distribution of MSCs. The efficacy of MSC transplantation in treating TBI has been observed to be independent of differentiation of MSCs. The possibility that their therapeutic benefit is derived by replacement of injured tissue with differentiated MSCs is highly unlikely because only a small proportion of transplanted MSCs actually survive and fewer differentiate into neural cells in injured brain tissues. MSCs secrete or express factors that reach neighboring parenchymal cells via either a paracrine effect or a direct cell-to-cell interaction, or MSCs may induce host cells to secrete bioactive factors, which promote survival and proliferation of the parenchymal cells (brain remodeling) and thereby improve functional recovery. It is well documented that the predominant mechanisms by which MSCs promote brain remodeling and functional recovery after brain injury are related to bioactive factors secreted from MSCs or from parenchymal cells stimulated by MSCs (Chen et al., 2002; Mahmood et al., 2004). Much of research on MSC secretion has centered on individual small molecules such as growth factors, chemokines and cytokines. Paradigm-shifting findings that therapeutic effects of MSCs are mediated by secreted factors as opposed to the previous notion of differentiation into injured tissues offer numerous possibilities for ongoing therapeutic development of MSC secreted products.

MSC-derived Exosome as a Novel Therapy for TBI

Recent studies indicate that therapeutic effects of MSCs are likely attributed to their robust generation and release of exosomes (Lai et al., 2010; Xin et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015). Exosomes are endosome-derived small membrane vesicles, approximately 30 to 100 nm in diameter, and are released into extracellular fluids by cells in all living systems. Administration of cell-free exosomes derived from MSCs is sufficient to exert therapeutic effects of intact MSCs after brain injury (Xin et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015, 2016). A recent report demonstrates that extracellular vesicles (EVs) from MSCs are not inferior to MSCs in a rodent stroke model by comparing therapeutic efficacy of MSC-EVs with that of MSCs (Doeppner et al., 2015). The exosomes transfer RNAs and proteins to other cells which then act epigenetically to alter the function of the recipient cells. The development of cell-free exosomes derived from MSCs for treatment of TBI is just in its infancy (Zhang et al., 2015, 2016; Kim et al., 2016). In a proof-of-principle study, an intravenous delivery of MSC-derived exosomes improves functional recovery and promotes neuroplasticity in young adult male rats subjected to TBI induced by controlled cortical impact (Zhang et al., 2015), as shown in Figure 1. A recent study also demonstrated that isolated extracellular vesicles from MSCs reduce cognitive impairments in a mouse model of TBI (Kim et al., 2016). Administration of cell-free nanosized exosomes may avoid potential concerns associated with administration of living cells, which can replicate. Compared to their parent cells, exosomes may have a superior safety profile, they do not replicate or induce microvascular embolism, and can be safely stored without losing function. Exosomes could substitute for the whole cell therapy in the treatment of TBI. This may open new clinical applications for “off-the-shelf” interventions with MSC-derived exosomes for TBI. MSCs are most typically grown in traditional 2 dimensional (2D) adherent cell culture. Three dimensional (3D) conditions such as spheroid culture have been shown to stimulate higher levels of trophic factor secretion compared to monolayer culture. MSCs seeded in the 3D collagen scaffolds generated significantly more exosomes compared to the MSCs cultured in the 2D conventional condition (Zhang et al., 2016). Exosomes derived from MSCs cultured in 3D scaffolds provided better outcome in spatial learning than exosomes from MSCs cultured in the 2D condition, although an equal amount of exosomes isolated from MSCs in 2D or 3D conditions was administered intraperitoneally into rats after TBI (Zhang et al., 2016). These data suggest that the content of the exosomes is responsible for the differential therapeutic effects, and the 3D conditioned exosomes likely contain a different profile of proteins and genetic materials compared to 2D conditioned exosomes. The efficacy of exosomes may critically depend on the exosome contents including proteins, RNAs, lipids and DNAs (mitochondrial origin). The mechanisms underlying regenerative activities of MSC-derived exosomes are attractive subjects of ongoing investigation. A better understanding of the effects of exosomes derived from MSCs on functional recovery and brain remodeling and the underlying mechanisms of their actions are prerequisite for the development of MSC exosomes as an efficacious and novel therapy for TBI.

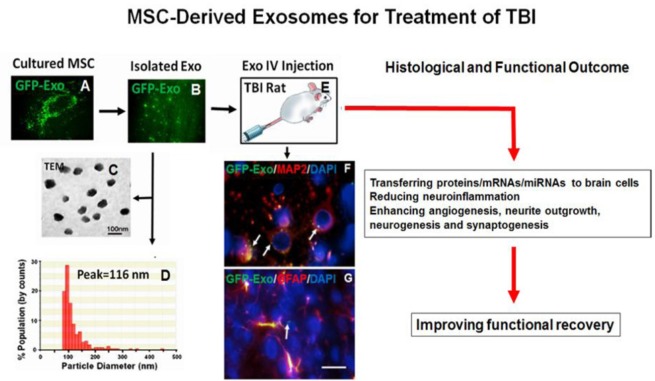

Figure 1.

Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for treatment of traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Microscopic images showing CD63-GFP expression in a cultured rat mesenchymal stem cell (rMSC, A) and in isolated exosomes from rMSCs (B). The TEM image showing morphology of isolated exosomes within a size range of 40–120 nm (C). Nanopore-based measurement with qNano showing a peak diameter of exosome-enriched particles at 116 nm (D). CD63-GFP tagged MSC exosomes (100 μg/rat) were intravenously (i.v.) administered 24 hours post TBI (E) and 30 minutes later, the rat brain was removed and processed for vibratome sectioning (100 μm) and double fluorescent immunostaining (microtubule associated protein 2, MAP2, for mature neurons, glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP, for astrocytes). Confocal images showing that CD63 GFP-tagged exosomes isolated from MSCs are taken up by neurons and astrocytes in the brain (F, G, arrows). Scale bar: 25 μm (G).

microRNAs in MSC-derived Exosomes as Possible Mediators of Neuroplasticity

microRNAs (miRNAs), small non-coding regulatory RNAs (usually 18 to 25 nucleotides), regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level (Chopp and Zhang, 2015), via binding to complementary sequences on target message RNA (mRNA) transcripts, and cause mRNA degradation or translational repression and gene silencing. In eukaryotic cells, miRNAs constitute a major regulatory gene family. Different cell types and tissues express different sets of miRNAs. By affecting gene regulation, miRNAs are likely to be involved in most biological processes such as developmental timing and host-pathogen interactions as well as cell differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis and tumorigenesis in various organisms. We propose that exosomes transfer miRNAs to the brain, which subsequently promote neuroplasticity and functional recovery after brain injury. For example, functional miRNAs transferred from MSCs to neural cells via exosomes promote neurite remodeling and functional recovery of stroke rats (Xin et al., 2012). As a control of exosomes, treatment with liposome mimic consisting of the lipid components of the exosome (no proteins and genetic materials) provides no therapeutic benefit compared with naïve exosome treatment after TBI (Zhang et al., 2016), indicating that the therapeutic effects of exosomes derive from the exosome content, including proteins and genetic materials, such as miRNAs. Additional research is warranted to determine the role of active miRNAs (master regulators of gene translation) of exosomes in promoting functional recovery and neurovascular remodeling, and regulating neuroinflammation and peripheral immune response as well as brain growth factors.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

MSC-derived exosomes have shown promise in the field of regenerative medicine including treatment of TBI, and 3D MSC culture further enhances generation of exosomes and therapeutic effects. Exosomes play an important role in intercellular communication. The refinement of MSC therapy from a cell-based therapy to cell-free exosome-based therapy offers several advantages, as it eases the arduous task of preserving cell viability and function, storage and delivery to patient because their bi-lipid membranes can protect their biologically active cargo allowing for easier storage of exosomes, which allows a longer shelf-life and half-life in patients. As such, exosomes are more amenable to development as an “off-the-shelf” therapeutic agent that can be delivered to patients in a timely manner. They also reduce the safety risks inherent in administering viable cells such as the risk of occlusion in microvasculature or unregulated growth of transplanted cells. Exosome-based therapy for stroke and TBI does not compromise efficacy associated with using complex therapeutic agents such as MSCs (Xin et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2016; Zhang and Chopp, 2016). In contrast to transplantation of exogenous neural stem/progenitor cells, MSC-derived exosomes that stimulate endogenous neural stem/progenitor cells to repair injured brain may have several main advantages including: (1) no ethical issue of embryonic and fetal cells, (2) less invasiveness, (3) low or no immunogenicity, and (4) low or no tumorigenicity. Exosomes are promising therapeutic agents because their complex cargo of proteins and genetic materials has diverse biochemical potential to participate in multiple biochemical and cellular processes, an important attribute in the treatment of complex diseases with multiple secondary injury mechanisms involved, such as TBI. A clinical trial using exosomes from cord blood β-cell mass for treatment of Type I diabetes mellitus is ongoing (NCT02138331). Developing a cell-free exosome-based therapy for TBI may open up a variety of means to deliver targeted regulatory genes (miRNAs) to enhance multifaceted aspects of neuroplasticity and to amplify neurological recovery, potentially for a variety of neural injuries and neurodegenerative diseases. Further investigation is warranted to take full advantage of regenerative potential of cell free MSC-derived exosomes, including the choice of MSC sources and their culture conditions, as these have been shown to impact the functional properties of the exosomes. In addition to the role of miRNAs, further investigation of exosome-associated proteins is warranted to fully appreciate the mechanisms of trophic activities underlying exosome-induced therapeutic effects in TBI.

There are several potential impacts of developing cell-free MSC-derived exosomes as a treatment for TBI. First, it will open up important and novel ways to elucidate how exogenously administered MSCs communicate with and alter neural cells to activate restorative events in TBI rats. Second, it represents a major leap forward in our understanding of intercellular communication via exosomal miRNAs and will lead to novel ways to augment brain recovery by targeting angiogenesis, neurogenesis and synaptogenesis as well as brain and peripheral immune response. Third, development of exosome-based therapy serves as a prototype to further transport specific miRNAs, and also to manufacture designer exosomes for functional gain or loss of specific miRNAs. Exosome-based cell-free therapy for TBI is promising. The wealth of methods applied thus far are focused on addressing many basic questions concerning exosomes including mechanisms of generation and release, size, constituent components, and targeting and interaction with recipient cells.

The ongoing and next steps for exosome research in the translational regenerative medicine would be to determine the mechanisms (central and peripheral effects) of the exosomes underlying improved functional recovery after TBI, maximize generation of exosomes by the MSCs, identify the optimal sources of cells used for generating exosomes and determine potential effects of age and sex of donor cells on exosome generation and contents, refine the isolation procedure for exosomes, define the optimal dose and therapeutic time window and potential routes of administration, identify the contents of exosomes, modify the content contained in or on exosomes for targeted treatment, develop exosomes as a drug delivery system that can cross the blood-brain barrier and facilitate drug penetration into the brain, scale up cell manufacturing and exosome preparation by developing and refining 3D culture methods such as scaffolds, or tissue-engineered models, cell spheroids, and micro-carrier cultures, monitor potential adverse effects, and move towards translating these studies into therapies for TBI and other diseases. Although exosomes provide promising beneficial effects in the rodent TBI model, the field of using exosomes as a regenerative medicine needs to address additional questions, including exactly how exosomes pass the blood-brain barrier into the brain, how their contents including mRNAs, miRNAs, lipids and proteins are transferred from exosomes to parenchymal cells, and which factor(s) play a major role in the treatment of TBI.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 NS088656 to MC. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not the necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- Chen X, Katakowski M, Li Y, Lu D, Wang L, Zhang L, Chen J, Xu Y, Gautam S, Mahmood A, Chopp M. Human bone marrow stromal cell cultures conditioned by traumatic brain tissue extracts: growth factor production. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69:687–691. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopp M, Li Y. Treatment of neural injury with marrow stromal cells. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:92–100. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopp M, Zhang ZG. Emerging potential of exosomes and noncoding microRNAs for the treatment of neurological injury/diseases. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2015;20:523–526. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2015.1061993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doeppner TR, Herz J, Gorgens A, Schlechter J, Ludwig AK, Radtke S, de Miroschedji K, Horn PA, Giebel B, Hermann DM. Extracellular vesicles improve post-stroke neuroregeneration and prevent postischemic immunosuppression. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:1131–1143. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DK, Nishida H, An SY, Shetty AK, Bartosh TJ, Prockop DJ. Chromatographically isolated CD63+CD81+ extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stromal cells rescue cognitive impairments after TBI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:170–175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522297113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai RC, Arslan F, Lee MM, Sze NS, Choo A, Chen TS, Salto-Tellez M, Timmers L, Lee CN, El Oakley RM, Pasterkamp G, de Kleijn DP, Lim SK. Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. 2010;4:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood A, Lu D, Chopp M. Intravenous administration of marrow stromal cells (MSCs) increases the expression of growth factors in rat brain after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:33–39. doi: 10.1089/089771504772695922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin H, Li Y, Cui Y, Yang JJ, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Systemic administration of exosomes released from mesenchymal stromal cells promote functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity after stroke in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1711–1715. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin H, Li Y, Buller B, Katakowski M, Zhang Y, Wang X, Shang X, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Exosome-mediated transfer of miR-133b from multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells to neural cells contributes to neurite outgrowth. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1556–1564. doi: 10.1002/stem.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Chopp M. Emerging treatments for traumatic brain injury. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2009;14:67–84. doi: 10.1517/14728210902769601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chopp M, Meng Y, Katakowski M, Xin H, Mahmood A, Xiong Y. Effect of exosomes derived from multipluripotent mesenchymal stromal cells on functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity in rats after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2015;122:856–867. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.JNS14770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chopp M, Zhang ZG, Katakowski M, Xin H, Qu C, Ali M, Mahmood A, Xiong Y. Systemic administration of cell-free exosomes generated by human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells cultured under 2D and 3D conditions improves functional recovery in rats after traumatic brain injury. Neurochem Int. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.08.003. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Exosomes in stroke pathogenesis and therapy. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:1190–1197. doi: 10.1172/JCI81133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]