Abstract

The 58 kDa complex formed between the [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin, putidaredoxin (Pdx), and cytochrome P450cam (CYP101) from the bacterium Pseudomonas putida has been investigated by high-resolution solution NMR spectroscopy. Pdx serves as both the physiological reductant and effector for CYP101 in the enzymatic reaction involving conversion of substrate camphor to 5-exo-hydroxy-camphor. In order to obtain an experimental structure for the oxidized Pdx-CYP101 complex, a combined approach using orientational data on the two proteins derived from residual dipolar couplings and distance restraints from site-specific spin labeling of Pdx has been applied. Spectral changes for residues in and near the paramagnetic metal cluster region of Pdx in complex with CYP101 have also been mapped for the first time using 15N and 13C NMR spectroscopy, leading to direct identification of the residues strongly affected by CYP101 binding. The new NMR structure of the Pdx-CYP101 complex agrees well with results from previous mutagenesis and biophysical studies involving residues at the binding interface such as formation of salt bridge between Asp38 of Pdx and Arg112 of CYP101, while at the same time identifying key features different from earlier modeling studies. Analysis of the binding interface of the complex reveals that the side-chain of Trp106, the C-terminal residue of Pdx and critical for binding to CYP101, is located across from the heme-binding loop of CYP101 and forms non-polar contacts with several residues in the vicinity of heme group on CYP101, pointing to a potentially important role in complex formation.

Keywords: residual dipolar coupling, CYP101, protein complex, HADDOCK, spin labeling

Introduction

Heme monooxygenases from the P450 superfamily have been extensively studied in context of both the mechanism of electron transfer and redox partner recognition, due to their importance in drug metabolism, toxicity, xenobiotic degradation and biosynthesis.1 The catalytic cycle of P450 enzymes requires two electrons typically provided by an external reducing agent (NADH or NAD(P)H). An essential step in the catalytic reaction cycle of many P450 enzymes is the binding of an allosteric effector. The camphor hydroxylation pathway of the bacterium Pseudomonas putida has long served as a model system for detailed studies of such P450-effector interactions. In this pathway, putidaredoxin (Pdx), a [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin, acts as the physiological reductant and effector for cytochrome P450cam (CYP101), that results in conversion of the substrate, camphor, to product, 5-exo-hydroxycamphor. CYP101 is quite specific for Pdx in terms of its effector activity. While CYP101 can accept the first electron from any donor with the appropriate reduction potential, the second electron transfer specifically requires the presence of Pdx for full activity.2

Over the past three decades, numerous theoretical and experimental studies, based in large part on site-directed mutagenesis, spectroscopic and kinetic data, have been carried out to characterize the binding interactions between Pdx and CYP101 and in order to explain the role of Pdx as an effector.3–12 Results from such studies suggest that Pdx binds to the proximal surface of CYP101, enabling direct electron transfer from the [2Fe-2S] cluster to the heme.10,13 Electrostatic interactions are expected to play a key role in the complex formation, with a predicted salt-bridge between Asp38 of Pdx and Arg112 of CYP101 that is important in both binding and electron transfer.6,14–16 Additionally, the aromatic nature of the C-terminal residue Trp106 of Pdx has been deemed critical for binding to CYP101.3,11,17,18 Early solution NMR studies on the oxidized Pdx-CYP101 complex by Pochapsky and coworkers, based on chemical shift perturbations for Pdx and supplemented with molecular modeling, indicated the potential involvement of the above residues and a number of other residues on the surface of Pdx in complex formation with CYP101.15 Similarly, recent NMR studies on reduced CYP101-Pdx complex by the same group mapped out portions of the proximal Pdx binding surface on CYP101, and located structural regions in CYP101 that are affected by complexation including residues on the distal side of CYP101, remote from the proposed Pdx binding site.19

Inspite of the above studies, the precise binding geometry between Pdx and CYP101 in any of the redox state pairings is not known, which hampers elucidation of the exact structural role played by these residues. Furthermore, while NMR and spectroscopic studies by a number of groups have provided structural insights into the nature of conformational changes near the active site of CYP101, especially in context of orientation of substrate in the active site,20–24 little structural data is available from the previous NMR studies on the involvement of residues directly around the Pdx [2Fe-2S] cluster in interactions with CYP101, due to paramagnetic line broadening near the [2Fe-2S] cluster. This region, along with the C-terminal cluster of Pdx, has been implicated in modulating redox-dependent binding to CYP101.12,25–27 A more detailed structural characterization of the Pdx-CYP101 complex is obviously necessary to delineate specific interactions, especially in vicinity of redox center of Pdx.

Despite considerable efforts, the crystal structure of complex between Pdx and CYP101 has still remained elusive. Solution NMR spectroscopy has good potential to obtain high-resolution structural data on protein complexes, however structure determination of protein complexes the size of Pdx-CYP101 complex (MW ~ 58 kDa) by traditional nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE)-based methodology can be challenging, since this requires extensive assignments that are difficult to obtain, especially on side-chains of larger proteins. Recent advances in NMR methodology like transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy (TROSY)28 can allow acquisition of high-resolution data on larger protein systems and help derive long-range structural information for structural refinement of biomolecular complexes in concert with approaches such as residual dipolar coupling (RDC) or site-directed spin labeling. While orientational restraints from RDC measurements and paramagnetic distance restraints from spin-labeling are being applied individually to study an increasing number of protein complexes,29–37 a combination of these two methods for investigation of protein-protein complexes has not been reported. Combining the two approaches offers certain advantages in that it can augment their utility and improve accuracy of the calculated structures due to complementary nature of the measured restraints. In addition, measurements of fewer restraints may be required on the complexing proteins compared to when used individually and that too on only backbone nuclei. This allows rapid assembly of protein-protein complexes, providing a viable alternative to NOE-based or pure docking-based approaches.

Here, we demonstrate use of the combined RDC/spin labeling approach by measuring NMR orientational restraints on the Pdx-CYP101 complex in the form of RDCs and paramagnetic NMR distance restraints on CYP101 from spin labeled Pdx to obtain the solution NMR structure of the complex between oxidized Pdx (Pdx°) and oxidized substrate-bound CYP101 (CYP101°), the first such structure for a complex between a ferredoxin and cytochrome P450. The Pdx-CYP101 complex offers an excellent opportunity for application of this combined approach due to availability of high-resolution structures and NMR backbone assignments for both Pdx and CYP101,19, 38–42 and also the relatively weak binding in the complex between the oxidized forms of the two proteins, which can allow the study of this complex under fast exchange conditions (Kd ~ 17 μM for the oxidized complex).3,4,19,43,44 Successful demonstration of the combined approach here not only allows structural visualization of specific interactions in Pdx-CYP101 complex formation, but also opens up avenues for its application towards other protein complexes, especially those involving P450s that are typified by weak affinity interactions between binding partners in the micromolar to millimolar range and hence are less amenable to crystallization in complex form. Additionally, as part of this study, we have mapped spectral changes occurring for residues in immediate vicinity of the paramagnetic metal cluster of Pdx due to complex formation with CYP101 using 15N and 13C NMR spectroscopy, leading for the first time to direct spectroscopic identification of residues in this region strongly affected by CYP101 binding.

Results

NMR spectral changes in diamagnetic regions of Pdx° and CYP101° upon complexation

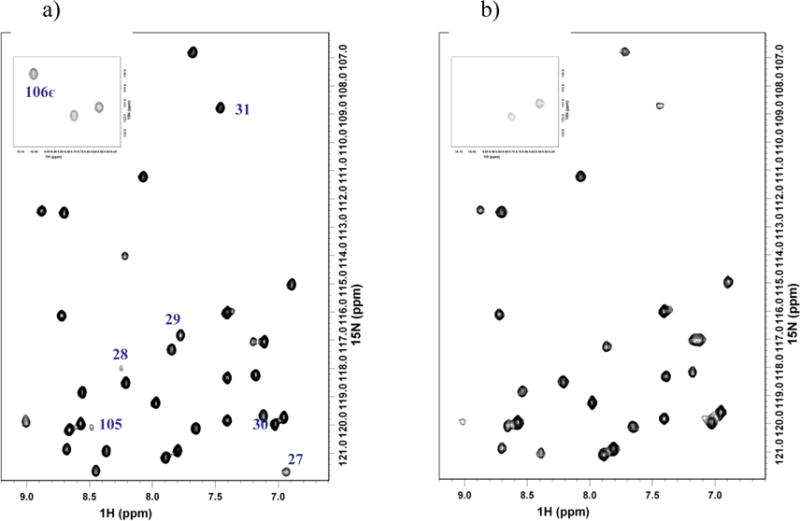

Spectral changes could be clearly monitored for a majority of the residues in the diamagnetic regions of Pdx° and CYP101° via simple 1H-15N TROSY spectra acquired on Pdx° and CYP101° in complex with each other and are depicted as line-broadening and chemical shift perturbations mapped onto the three-dimensional structures of Pdx° and CYP101° (Figure 1). While spectral changes affecting residues in Pdx° and CYP101° upon complexation have been reported previously,15,45 the increased sensitivity and resolution offered by the TROSY experiments on highly deuterated 15N-labeled samples allowed us to analyze the spectral changes between the two proteins in greater detail, making it possible to identify some new features, especially in Pdx°. In Pdx°, the most dramatic changes occur for backbone amide resonances of residues Val28, Ser29, Asn30 (helix D) and Trp106 NHε (C-terminus) that are broadened beyond detection upon addition of CYP101° (Figure 2). Other resonances that exhibit considerable line-broadening, but do not disappear completely, correspond to residues Ser26 and Ala27 on the D helix, Gly31 and Ile32 on the loop leading from the D helix to the Fe-S cluster binding loop, and Gln105 near the C-terminus. The observed broadening indicates that the amide groups of these residues enter a slower motional regime upon interaction with CYP101. The fact that these changes are primarily restricted to helix D and the C-terminal cluster, indicate that these structural features are motionally restricted in some fashion in the Pdx-CYP101 complex, either as a direct effect of binding, via interactions with residues across the binding interface in CYP101, or indirectly, due to solvent-mediated hydrogen-bonding interactions at the interface. While it is not possible to observe these water molecules directly in our experiment, we note that presence of interfacial water molecules has been predicted from osmotic pressure studies on the complex.44 Interestingly, we and others have previously noted conformational and dynamic changes also for these same residues as a function of oxidation state.12,40,41 This gives rise to the speculation that a mechanism involving these residues might exist, which can modulate binding of Pdx to CYP101 in a redox-dependent fashion. The distinctness of the slow exchange nature of Trp106 side-chain and helix D in the complex from the fast exchange binding observed for the rest of the protein supports this contention. Further experimental studies are needed to explore this further. In addition to changes reported above, significant chemical shift perturbations are also observed with minimal line-broadening for residues 66–68 (helix G), residues 8–13 on the loop connecting the N-terminal β-strands, residues 74–76 on the loop leading from the G helix to β-strand I, residue 88 on loop following the β-strand I and residue 104 near the C-terminus.

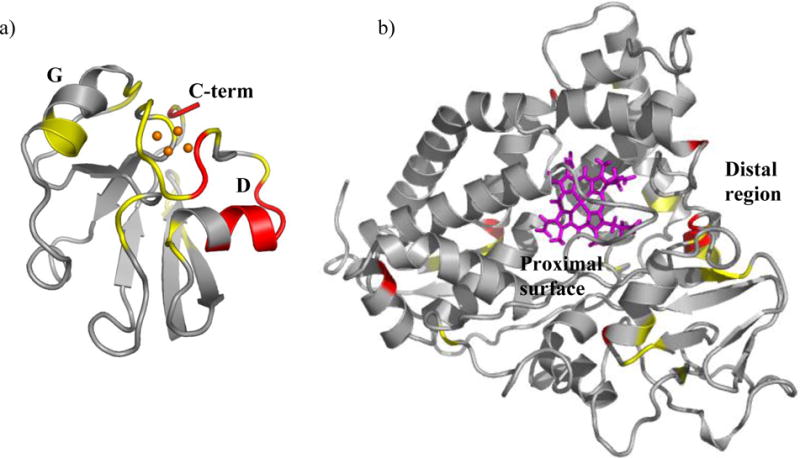

Figure 1.

Structural regions of Pdx° and CYP101° affected by complex formation. Residues in a) Pdx° and b) CYP101° structures are color coded to show distribution of 1H-15N resonances affected in NMR spectra of Pdx° and CYP101° upon complexation. Those depicted in red are residues whose resonances disappear or broaden severely upon binding of the other partner, while resonances for those in yellow do not disappear but are moderately broadened or perturbed upon binding. The [2Fe-2S] cluster is shown as orange spheres, while heme group is shown in pink. The secondary structure elements of Pdx° are labeled as “D” (helix D), “G” (helix G) and “C-term” (C-terminus). The proximal and distal surfaces of CYP101° are labeled. The figures were prepared using the program PyMOL.62

Figure 2.

Changes in 15N NMR spectra of uniformly 15N labeled Pdx° upon addition of CYP101°. a) 15N Pdx° and b) 15N Pdx° + CYP101° in a 3:1 molar ratio. Residues in helix D and C-terminus of Pdx° broadened by complexation are labeled. Line-broadening for Trp106 NH∊ resonance is shown as inset.

For CYP101°, the spectral changes are less prominent. Analogous to observed changes in Pdx°, resonances for residues Gly68, Ser83, Glu107, Glu152, and Leu274 disappear upon addition of Pdx° (shown in red in Figure 1) while resonances for Val54, Ala65, Thr66, Leu70, Cys85, Glu91, Cys148, Thr151, Arg186, Glu195, Ala196, Ile207, Ile300, and Leu301 show moderate to considerable broadening accompanied by change in chemical shift (shown in yellow in Figure 1). These are similar to those observed by Pochapsky and coworkers in their previous NMR studies, however less pronounced in comparison to those in the reduced CYP101-Pdx complex.19 While some of the residues are positioned at the proximal surface of CYP101 (68, 70, 83, 107, 274, 300, 301) near the heme as part of helices B, C, J and beta-strand β4, others are on the distal side of the heme (91, 93, 151, 152, 186, 195) and may be related to Pdx-induced conformational changes in the distal regions of CYP101 (Figure 1). In addition, there are several other resonances that do show line-broadening and/or perturbations but are as yet unassigned.

NMR spectral changes in paramagnetic region of Pdx° upon complexation with CYP101°

The current studies provide information about involvement of a number of critical residues near the [2Fe-2S] cluster in the interaction with CYP101. In Pdx°, these are residues that are too close to the paramagnetic [2Fe-2S] cluster (within ca. 5–8 Å) for their 1H resonances to be observed and assigned using standard NMR methods. However, in concert with selective labeling, direct 13C and 15N observation combined with double resonance and fast acquisition methods have previously provided sequence-specific chemical shift assignments for most 15N and 13C′ (carbonyl) hyperfine-shifted resonances in Pdx°.26 In turn, these assignments allow us to identify residues in the paramagnetic region of Pdx° that are most perturbed upon addition of CYP101°, providing a set of specific and sensitive probes for examining the interactions between the redox partners.

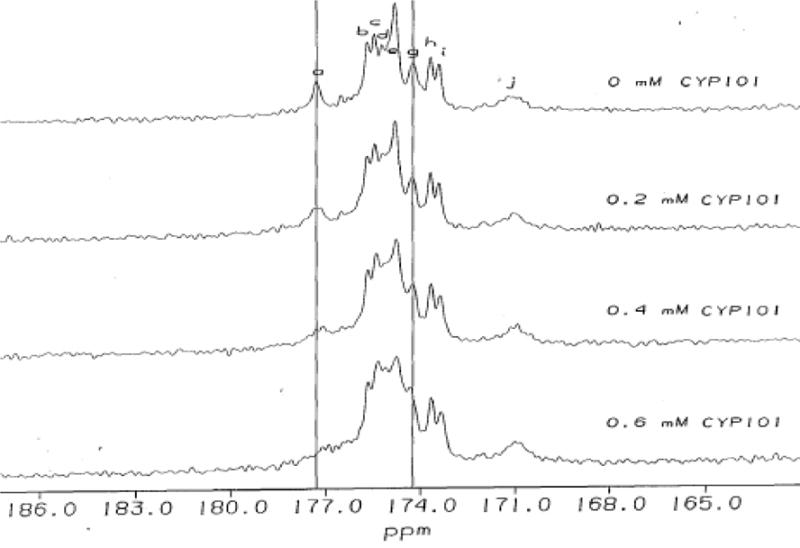

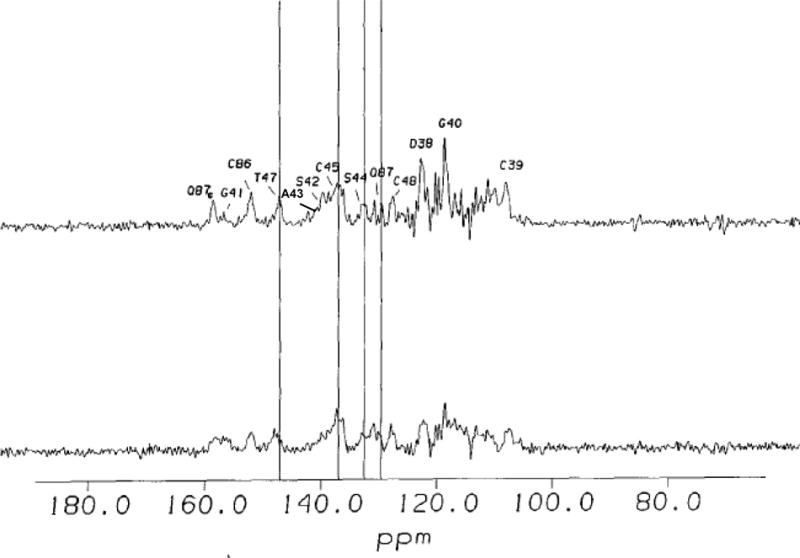

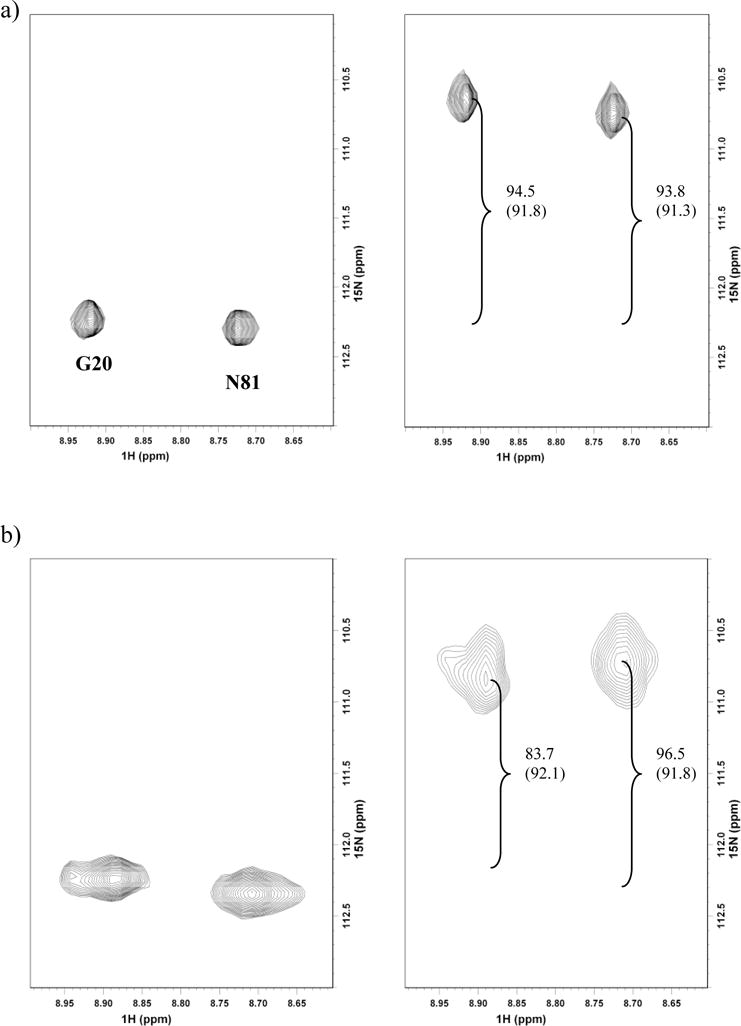

Figure 3 shows the results of titration of a Pdx° sample selectively labeled at 13C′ Gly (scrambled to 13C′ Ser and 13C′ Cys) with increasing amounts of camphor-bound CYP101°. Upon addition of CYP101°, the paramagnetically relaxed 13C′ (carbonyl) resonances of Pdx° undergo varied amounts of line broadening and change in their chemical shifts (Figure 3). Specifically, the 13C′ resonances of Cys39 and Gly40 show the greatest line broadening, whereas the 13C′ resonances of the other residues show moderate to little line broadening. In addition, the 13C′ resonances of all residues in the paramagnetic region shift progressively upfield upon addition of CYP101° except Ser42, which moves downfield. On the other hand, titration of uniformly labeled 15N Pdx° with CYP101° shows a distinct pattern of changes for the 15N hyperfine-shifted resonances (Figure 4). While most of the 15N resonances in the paramagnetic region of Pdx also shift upfield as CYP101° is added, the 15N resonances of Ala43, Ser44, Cys45, Thr47 and Gln87 show progressive downfield shifts (Figure 4). The NH protons of these five residues are thought to be hydrogen-bonded to the metal cluster based upon evidence from temperature dependence of their 15N resonances and the X-ray crystallographic structure of putidaredoxin.25,41 The differential behaviour of this group of residues upon complexation of CYP101° may reflect changes in the hydrogen bonding interactions with the metal cluster when CYP101° is bound to Pdx°. Apart from this group of residues that shows a collective response to binding as also the greatest response in their 15N shifts to changes in oxidation state of the metal cluster, comparison of 15N and 13C′ chemical shifts for other metal binding loop residues in oxidized and reduced Pdx (Pdxr) also suggests that significant conformational changes occur in the loop upon changing oxidation state. Taken together, these observations suggest that residues in the loop region are not only involved in CYP101 binding, but maybe in the redox modulation of that binding as well.

Figure 3.

Changes in 13C NMR spectra of 13C labeled Pdx° upon addition of 0.2 mM increments of CYP101°. Residues in paramagnetic region of Pdx° affected by complexation are labeled. Peak labels a,b,h,i,j in 13C spectrum correspond to cysteine residues 39, 85, 86, 48 and 45 respectively; d,g correspond to serine residues 44 and 42 respectively; c,e,f correspond to glycine residues 41, 37 and 40 respectively. Differential changes in line-broadening and chemical shift for Cys39 and Ser42 are indicated by vertical lines.

Figure 4.

Changes in 15N NMR spectra of uniformly 15N labeled Pdx° upon addition of CYP101°. Residues in paramagnetic region of Pdx° affected by complexation are labeled. Differential changes in line-broadening and chemical shift are indicated by vertical lines.

Finally, the response of Asp38, one of the key residues in Pdx-CYP101 interaction, to the presence of CYP101 was investigated. Addition of CYP101° causes noticeable perturbation in the position of 15N backbone amide resonance of Asp38 that could imply small changes in the main-chain conformation for this residue. A strong interaction of side-chain of Asp38 with side-chain of Arg112 has been postulated by various studies as part of a putative electron transfer pathway.6,14 It may be that reduction of Pdx sufficiently perturbs the metal binding loop so that Asp38, especially the side-chain, interacts with CYP101 more effectively in Pdxr.

Measurement of orientational and distance restraints for the Pdx°-CYP101° complex

RDC measurements to obtain orientational restraints were carried out for both Pdx° and CYP101° in complex using a TROSY/semi-TROSY scheme (Figure 5).46 Both proteins could be oriented in phage medium without any noticeable structural perturbations. Attempts to orient CYP101° in bicelle medium were unsuccessful, due to strong interaction of CYP101° with the bicelles, possibly via the charged patches on the surface of CYP101°. Although the resonances for the complex were well-resolved in the TROSY spectrum, the relatively high molecular weight of the complex caused significant line-broadening in the semi-TROSY spectrum, making difficult measurement of peak positions in the central overlapped regions of the semi-TROSY spectrum for both Pdx° and CYP101°. As such, RDC measurements were carried out with sufficient precision for only 36 residues in complexed Pdx° and 23 residues in complexed CYP101°. Also, in the case of CYP101°, non-availability of assignments for several of the resonances that could be measured limited the number of RDC measurements. While we note that the number of assigned RDCs is limited, complexation studies have been performed successfully with fewer measurements.35,36 In our case, highly accurate orientational restraints requiring a large number of RDC measurements may not be necessary, due to availability of several distance restraints that can compensate for deviations in orientation. Moreover, these measurements span the various structural elements in Pdx° and CYP101° and should be adequate to define orientational properties of the complex.

Figure 5.

15N-1H residual dipolar coupling measurements for a representative set of resonances from spectra recorded in a TROSY/semi-TROSY fashion46 at 600 MHz on a) 15N labeled sample of Pdx° and b) 15N,2H labeled Pdx° in complex with unlabeled CYP101°. Both samples were aligned in 5 mg/mL phage solution. 1DNH RDC values are measured from the difference in peak splittings (shown in Hz). Isotropic values of 1DNH are shown in brackets.

Spin-labeling of Pdx° was performed using the sulfhydryl group of the only surface-accessible cysteine residue, C73.39–41 We took advantage of this structural characteristic by acquiring 15N-1H NMR spectra of Pdx° selectively labeled at Cys73 with the MTSL spin label, which show selective broadening of backbone amide resonances around Cys73 to a distance of 26 Å (data not shown), with resonances within 8 Å of Cys73 (Gln72-Ala76 NH, Trp106 NεH), being broadened to invisibility. On the other hand, little or no change in chemical shift is observed for any resonance, indicating negligible change in structure of Pdx° due to spin labeling.

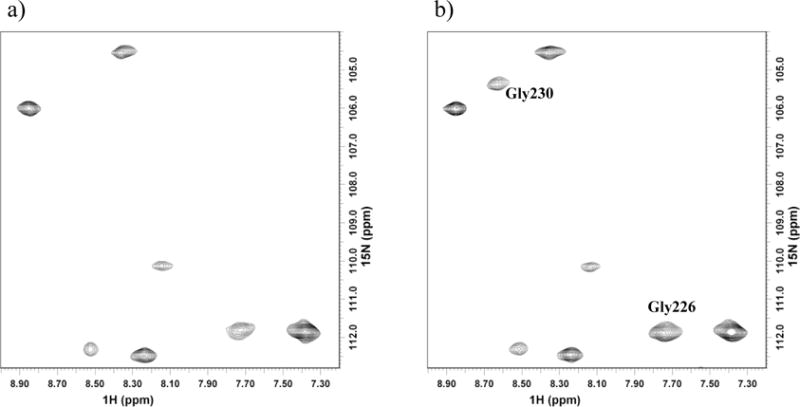

Previous NMR studies on the complex by Pochapsky and coworkers suggest that Cys73 is near the binding interface of Pdx° and CYP101°.15 We tested this possibility by titrating MTSL-tagged Pdx° with CYP101° and in fact detected peak intensity changes for several resonances in CYP101o 15N-1H spectra, indicating that the spin label is within interacting distance of several residues near the binding interface in CYP101°. Comparison of chemical shift changes in the Pdx°/CYP101° complex spectra with and without the spin label indicated that the presence of spin label near the binding interface does not alter the binding properties of the Pdx°-CYP101° complex. Spin-label induced broadening was used to obtain multiple distance restraints to residues in between Pdx° and CYP101° in the complex. Table 1 shows the list of residues in CYP101° to which distances from spin label on Pdx° were measured. Much of the Pdx binding surface in CYP101° is affected by paramagnetism of heme, and NH resonances from this region are not observed in 1H, 15N correlation spectra of the oxidized protein. We were therefore able to obtain restraints only to residues in regions beyond those affected by paramagnetism of the heme, are not severely overlapped and for which sequence-specific assignments are available. As such, changes in peak intensities as a function of oxidation state of spin label could be measured with confidence for only 7 residues. However, these are distributed over a large portion of the binding interface in CYP101° and are of sufficient accuracy to constrain Pdx° translationally relative to CYP101° in concert with available orientational restraints during the docking process. An example of such measurements is shown in Figure 6.

Table 1.

Distance restraints measured from paramagnetic relaxation enhancement of resonances in CYP101° upon addition of spin labeled Pdx° versus back calculated from docked complex structure

| Residue Number | CYP101°complex (measured Å)a | Cyp101°complex (back calculated Å)a |

|---|---|---|

| 230 | 16.3 | 14.8 |

| 228 | 19.2 | 16.8 |

| 226 | 17.4 | 17.2 |

| 85 | 21.0 | 21.1 |

| 77 | 17.7 | 17.4 |

| 70 | 21.3 | 22.9 |

| 67 | 23.4 | 26.6 |

Distances are reported from the Nitrogen atom of the nitroxide moiety in the MTSL spin label to HN backbone amide atom of the corresponding residue.

Figure 6.

Comparison of spectral changes in 1H-15N correlation spectra of CYP101° showing change in peak intensities of selected resonances due to intermolecular paramagnetic relaxation enhancement upon addition of Pdx° spin labeled with MTSL. Effect on resonances of Gly230 and Gly226 in CYP101° due to a) paramagnetic spin label and b) diamagnetic spin label reduced with ascorbic acid.

Structural characterization of the Pdx°-CYP101° complex

The combination of distance restraints (from spin-label-induced broadening) with orientational restraints from RDCs helps overcome the ambiguity problem in orientation typically observed in structures calculated with RDCs measured in one alignment medium.47 No major conformational changes were observed for either Pdx° or CYP101°, as expected from a semi-flexible mode of docking, where only the active and passive residues are designated as flexible. The resulting structure calculated in HADDOCK showed no distance violations and only 6 RDC violations (> 3 Hz) corresponding to residues Asn9, Gly20, Arg66, Glu67, Ile68 and Thr91 of Pdx°. This is not surprising though, since these residues are known to be part of highly mobile regions in Pdx° and can lead to anomalous RDC values due to motional averaging.

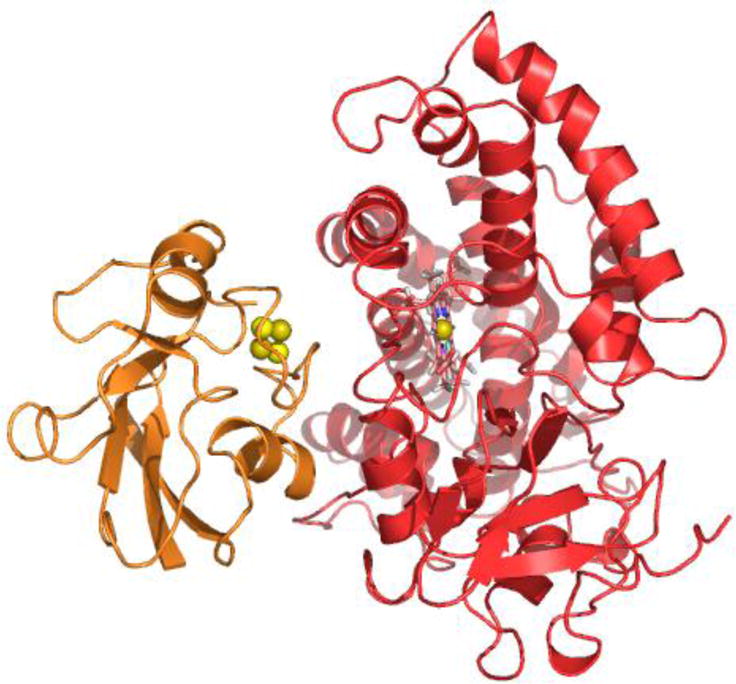

Analysis of the complex structure shown reveals that the binding surfaces of Pdx° and CYP101° are sterically complementary to each other (Figure 7). There are minimal interactions present in the binding interface, as expected from the low binding affinity for the oxidized complex (Kd ~17 μM) and as predicted by other studies.9,15,44,48 Binding of Pdx° takes place on the proximal surface of CYP101° with the metal cluster binding loop in Pdx° directly facing the heme. The distance between the Fe atom closest to the surface in the [2Fe-2S] cluster and the Fe atom in heme is measured at 17.1 Å (Figure 8), which corresponds to the expected distance for electron transfer between the two metal centers.49 The metal binding loop in Pdx° along with the surrounding helices D and G fits quite well into the groove formed by helices B and C around the heme in CYP101°. This along with the C-terminal region in Pdx° and the heme-binding loop in CYP101° constitutes majority of the binding interface between the two proteins. Residues in Helix D of Pdx°, though not observed to be present directly at the binding interface, are near several polar residues in CYP101°. In particular, side-chains of Gln25, Val28 and Tyr33 in Pdx° are in close proximity to side-chains of Arg72, Glu76 and His352 in CYP101°, which may contribute in part to the observed line-broadening and slowing of motion of this helix due to influence of the polar residues in CYP101°.

Figure 7.

Ribbon representation of the NMR structure of Pdx°/CYP101° complex derived from docking of Pdx° (in orange) and CYP101° (in red) structures in HADDOCK56 using RDC orientational and intermolecular paramagnetic spin label distance restraints. The [2Fe-2S] metal cluster of Pdx° is shown as spheres, while the heme prosthetic group of CYP101° is shown as sticks. The figure was prepared using the program PyMOL.62

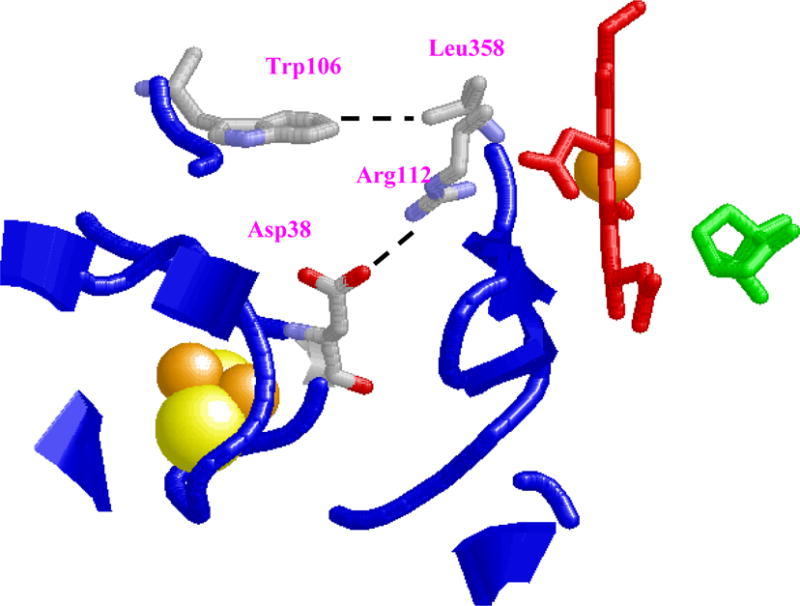

Figure 8.

Structural representation of binding interface between Pdx° and CYP101°. Key interactions involving possible salt-bridge formation between Asp38(Pdx°)-Arg112(CYP101°), interaction between sidechains of Trp 106(Pdx°)-Leu 358(CYP101°) are shown. Predicted distance between the [2Fe-2S] metal cluster (spheres) of Pdx° and heme Fe center (sticks) of CYP101° in the docked complex is shown as well. The substrate camphor is shown in green. This figure was prepared using the program RasMol.63

Corresponding changes in regions around the heme, especially in the substrate binding site, could not be monitored due to paramagnetism of the heme and also lack of restraints to neighbouring residues. Hence, in our docking scheme, residues in the active site and the substrate camphor were allowed to maintain fixed conformation. While change in orientation of the substrate in the binding site has been confirmed in several NMR studies on the reduced carbon-monoxy complex as also in a crystal structure of L358P mutant of CYP101 that mimics partially the activity of Pdx bound CYP101,23 lacking sufficient data, we cannot comment on nature of these changes in the present study of the oxidized complex and whether they are similar to the reduced complex.

Role of the key residues Trp106, Asp38 and Arg112 in Pdx°/CYP101° complex formation

One of the most prominent interactions observed in the structure is the expected formation of a salt-bridge between Asp38(Pdx°)-Arg112(CYP101°) (Figure 8). Even in docking runs where no explicit restraint between Asp38 and Arg112 was used, but other restraints were kept intact, the formation of this salt-bridge was a recurring feature (data not shown). This interaction therefore is quite likely present in the complex and is supported by numerous mutagenesis, binding and kinetic studies on both the oxidized and reduced complex.5,6,14 Several of these studies have also postulated an electron transfer pathway involving Asp38 and Arg112, whereby the electron is transferred through-bond from the Fe1 atom of Pdx° to Asp38 side-chain via backbone atoms of Cys39, and then onto Arg112 of CYP101° via the salt-bridge. Since the side-chain of Arg112 is in direct contact with the heme propionate in crystal structures of both reduced and oxidized CYP101°, it is possible that the electron from Pdx° is passed to the heme iron via this pathway as proposed in models of the complex by Roitberg and coworkers.9 NMR study of the reduced complex by Pochapsky and coworkers also noted strong perturbation for the resonance of Arg112 NεH upon addition of Pdx to CYP101.18

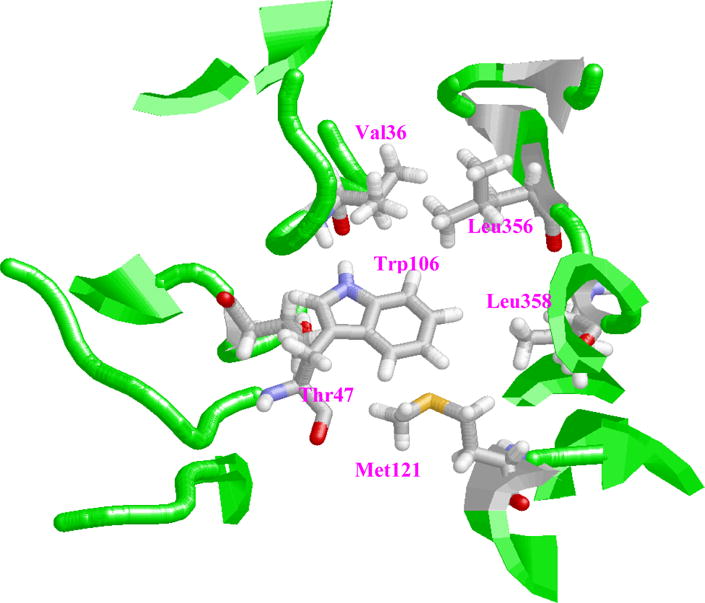

An interaction not observed in previous modeling studies of Pdx°-CYP101° complex involves one of the key residues in Pdx°, Trp106. From the structure for the complex in the present work, it is observed that Trp106 is located in a hydrophobic pocket surrounded by Leu358 (CYP101°), Leu356 (CYP101°), His361 (CYP101°), Met121 (CYP101°), Ile35 (Pdx°), Val36 (Pdx°) and Thr47 (Pdx°), and has non-bonded contacts with the methyl groups of Leu356, Leu358, Met121, His361 and Thr47 (Pdx°) (Figure 9). The presence of these interactions points to the role played by Van der Waals interactions in influencing the formation of the complex and is supported by ITC studies performed previously on the Pdx°/CYP101° complex.43 Based on the negative enthalpic and entropic values noticed for the complex, it was concluded that the formation of the complex is likely dominated by Van Der Waals and hydrogen bond interactions associated with loss in mobility, making the interaction more specific. The complex structure derived in this study, provides structural evidence for the first time on the role of Trp106 in driving the complex formation, with specific contacts to residues such as Leu358 and Leu356 on CYP101°. The contacts formed by Trp106 side-chain with these residues helps stabilize the complex to large extent, as there are minimal other contacts at the binding interface, explaining the critical role played by this residue in Pdx-CYP101 interaction.

Figure 9.

Location of Trp106 side-chain in hydrophobic pocket formed by various residues within the binding interface of Pdx°-CYP101° complex. This figure was prepared using the program RasMol.63

Other residues that form part of the binding interface include Arg109, Ser44, Lys344 and Arg79 of CYP101. Mutation of these residues to non-charged or oppositely charged residues is known to lead to reduced binding and electron transfer.6,10 Their presence in the binding interface is unsurprising since they are close to the key residues such as Asp38, Arg112 and Trp106.

Discussion

The Pdx°-CYP101° complex structure reported here provides a reasonable structural interpretation of results from earlier biochemical and biophysical experiments, especially concerning the role of key residues such as Trp106, Asp38 and Arg112 with a level of detail inaccessible by previous NMR and molecular modeling methods. One of the earliest structure-based models for the Pdx°/CYP101° complex by Pochapsky and coworkers premised a close approach between the metal centers of the two proteins and interactions between aromatic residues on the surfaces of the two proteins.15 However, due to lack of experimentally derived restraints, the relative orientation of Pdx° relative to CYP101° in their model differs by almost 180° when compared to the present structure. While some of the key intermolecular interactions such as presence of the salt-bridge between Asp38-Arg112 were correctly identified in that model, other interactions such as formation of Asp34-Arg109 salt-bridge are not observed in the present structure. The previous model also assumed that Trp106 is mainly involved in stabilization of the complex by interacting with another aromatic residue on CYP101°. As a consequence, Trp106 was located in an aromatic stacking interaction with Tyr78 and His352, and not near Leu358 as observed in the present study. Our observations on location of Trp106 near Leu358 are also supported by another docking study of the Pdx°/CYP101° complex based on data from Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy measurements.50 Similar to the present study, while Asp38-Arg112 interaction was observed in all docked structures, neither Trp106 nor Asp34 were located near the residues predicted by the previous model. The exact location for Trp106 was not specified though in those structures. Based on analysis of the two docking orientations presented in their paper, it is likely that Trp106 would in proximity to Leu358 in one of the orientations.

From these observations, it is interesting to speculate on the structural role that Trp106 plays in Pdx/CYP101 interaction. It is known from mutagenesis and kinetic studies that the aromatic nature of Trp106 is critical for both binding and electron transfer. In a study examining the effect of deleting or replacing Trp106 with non-aromatic residues, Davies et al. suggested that the role of Trp106 may be to protect the iron-sulfur cluster from the solvent, thereby increasing the magnitude of electrostatic effects from nearby charged residues and hence the electron transfer efficiency.3 This theory, though plausible, seems unlikely since Trp106 is located on one side of the [2Fe-2S] cluster in our structure, leaving the metal cluster and the Asp38-Arg112 slightly exposed to the solvent. Moreover, osmotic pressure studies on the complex suggest presence of several solvent molecules in the binding interface of both oxidized and reduced complex that could dilute the effect of Trp106 on electrostatic interactions.44 Thus, the proposed mechanism of Davies et al. may not be adequate to fully explain the structural role of the C-terminal residue. It however clearly points to the need of aromatic character for this residue, especially in context of observed binding affinity differences between oxidized and reduced Pdx.

An explanation may be forthcoming from our structural study as to why aromatic nature of Trp106 influences the binding affinity of Pdx for CYP101. The bulky nature of the Trp106 indole ring allows it to insert deep into the binding interface and form efficient interactions with non-polar residues such as Leu358 and Leu356 of the heme-binding loop, which may not be possible with a non-bulky side-chain. This would explain the loss of binding affinity when Trp106 is replaced with non-aromatic and polar residues, since the binding is likely dominated by non-polar, Van der Waals interactions as also suggested by ITC studies.43 Kuznetsov et al. in a recent study of the reduced Pdx/CYP101 complex also considered this possibility.49 On basis of kinetic and modeling data, they concluded that Trp106 couples the second electron transfer event to product formation possibly via its “push” effect on the heme-binding loop. The location of Trp106 across from Leu358 in close proximity to heme-binding loop in the oxidized complex lends credence to this possibility. A previous structural and functional study of the L358P mutant of CYP101 that mimics the Pdx-bound state of CYP101 also observed the displacement of the heme-binding loop towards heme via movement of Arg112 that could help facilitate the electron transfer from the electron donor.23 Since our structural analysis here is limited only to the oxidized complex, whether the general features of the interaction between Trp106 and heme-binding loop in the oxidized complex are likely conserved in the reduced complex and play a role in electron transfer/effector activity cannot be ascertained at this point and awaits further structural confirmation. The combined approach illustrated here will be quite valuable in such case.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of protein samples and NMR spectroscopy

Expression and purification of isotopically labeled Pdx and CYP101 were carried out using previously published protocols.19 Protein concentrations used for NMR samples of the complex ranged from 0.3–0.5 mM. Purified samples of Pdx and CYP101 were dialyzed against NMR sample buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM camphor, pH 7.4, 10% D2O) before being used for NMR measurements. Residual dipolar coupling (RDC) measurements were performed on the following samples – a) 15N, 2H sample (> 90% deuteration) of Pdx° in complex with unlabeled CYP101° in a molar ratio of 1:1, b) 15N,2H sample (>70% deuteration) of CYP101° in complex with unlabeled Pdx° in a molar ratio of 1:1, c) 15N labeled Pdx° and d) 15N, 2H labeled sample (>70% deuteration) of CYP101°. 1H-15N one-bond couplings were measured for each sample from two-dimensional sensitivity enhanced TROSY-HSQC spectra in a TROSY/semi-TROSY fashion,46 where each component of the coupling was measured in different sub-spectrum corresponding to the TROSY peak and the semi-TROSY peak in the 15N dimension. RDC values were measured from the difference in peak splittings in the pair of spectra for the isotropic and aligned phase. A 5 mg/ml phage solution (Asla Ltd, Latvia) was used for collection of data in aligned phase for all samples. For RDC data analysis, sequence-specific backbone 15N-1H assignments for Pdx° published previously were used.39 CYP101 assignments were as previously published, supplemented by recent assignments.19,42

Spin labeled Pdx was prepared by allowing [1-acetyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-3-pyrroline-3-methyl]-methanethiosulfonate (MTSL) spin label (Toronto Research Chemicals, ON, Canada) to react with the protein in a MTSL:protein molar ratio of 3:1 for 3 hrs at room temperature, followed by extensive dialysis against NMR sample buffer to remove the excess spin label. Pdx was spin labeled selectively at Cys73 site with MTSL using this method to an extent greater than 95% as confirmed by NMR and mass spectroscopy. A 2D 15N-1H correlation spectrum was collected for 15N-labeled CYP101° in complex with spin labeled Pdx°. The sample was reduced with three-fold molar excess of ascorbic acid and another 2D 15N-1H spectrum was collected under identical conditions. Selective reduction of only the spin label with ascorbic acid was observed and did not affect the oxidation state of metal center of either protein, as checked by a 2D HSQC spectrum for each protein in a separate experiment (data not shown).

Direct detect 15N and 13C experiments to observe hyperfine shifted resonances of Pdx° in complex with CYP101° were performed using methods described previously for Pdx alone.26,27 All NMR experiments were carried out on a Varian Unity Inova 600 MHz spectrometer at 17 °C, except the direct detect experiments which were carried out on a Bruker AMX500 spectrometer, operating at 50.68 and 125.76 MHz for 15N and 13C respectively, and equipped with a 5-mm broadband probe for heteronuclear detection. A typical 15N or 13C rapid acquisition experiment (recycling time <50 ms) consisted of 4K data points with a spectral width of 50000 Hz. Broadband 1H decoupling was used during all 15N acquisitions. The rapid acquisition of signals allowed for the efficient detection of paramagnetic resonances due to suppression of the diamagnetic resonances. Acquired NMR data was processed and analyzed using NMRPipe and NMRView software respectively.51,52

Calculation of order tensors and distance restraints

Dipolar couplings measured for complexed Pdx° and CYP101° correspond to an average between the free and bound states. Bound state dipolar couplings for either protein were calculated from the equation:

| (1) |

where Db is the dipolar coupling in the bound state, Dobs is the observed dipolar coupling, xf is the fraction of protein in the free state, Df is the dipolar coupling measured for protein in the free state and xb is the fraction of protein in the bound state. The fraction free and fraction bound for each protein were estimated using the known Kd value (~17 μM) of the Pdx°-CYP101° complex.43,44 It is estimated that majority of protein is in the bound form (~90%) and hence the measured RDCs reflect primarily the bound form RDCs. These were then used in the structure calculation protocol of HADDOCK as described below. For Pdx, a total of 36 RDC values were used while for CYP101, a total of 23 RDC values were used in the complex structure calculation. Experimental errors were estimated from the measurements and set to ± 3 Hz during structure calculation.

Intermolecular distance estimates were obtained from difference in intensities observed in 1H-15N HSQC spectra of spin labeled Pdx° in complex with CYP101° before and after reduction with ascorbic acid using the approach described by Battiste and Wagner.53 Briefly, the intensities (peak heights) of cross-peaks affected by paramagnetism of MTSL spin label were extracted directly using the peak-picking routines in NMRView. Intensity ratios between oxidized (Iox) (paramagnetic) and reduced (Ired) (diamagnetic) spectra were then converted into paramagnetic rate enhancements (R2sp) according to Eq. 2:

| (2) |

where t is the total polarization transfer time (~9 ms) and R2 is the intrinsic diamagnetic transverse relaxation rate for each amide estimated from the peak width of reduced spectra. Paramagnetic rate enhancements were then converted into distances using the following equation:

| (3) |

where r is the distance between the electron of spin label and nuclear spins, τc is the estimated global correlation time (~20 ns) of the protein complex from the Stokes-Einstein equation,54 ωh is the Larmor frequency of proton nuclear spin and K is the constant 1.23*10−32 cm6s−2.55 Distances larger than 26 Å were omitted from the restraints and ±4 Å bounds were applied during structure calculation. Distances calculated from the observed intensities are average between the free and bound state of CYP101°. Bound state distances were calculated from the dissociation constant of the complex in a manner similar to that for RDC calculation in equation (1). A total of seven distance restraints were obtained from the spin label to residues in CYP101 and are listed in Table 1.

Restraint-based docking of the Pdx°/CYP101° complex

Restraint-based docking calculations for Pdx°/CYP101° complex were performed using the docking protocol in HADDOCK.56 The topologies and starting structural coordinate files for input into HADDOCK were generated from the crystal structures of Pdx° and CYP101° (1XLP and 2CPP).38,41 The X-ray structure for Pdx° was used instead of the NMR structure,38 due to better definition of the surface-exposed side-chains. Docking of the complex was performed following the three stages in the protocol of HADDOCK, namely randomization of starting orientation and rigid body energy minimization, semi-flexible simulated annealing and flexible refinement in explicit water. Experimental restraints in form of ambiguous interaction restraints (AIRs), RDC orientational restraints and paramagnetic spin label distance restraints were defined and provided as input data to HADDOCK before commencement of the docking. For generation of AIRs, active and passive residues were defined on Pdx° and CYP101° based on NMR chemical shift perturbation, mutagenesis data and solvent accessibility (>50%). Residues 38, 106, 44 on Pdx° that are likely involved in interaction with CYP101° from mutagenesis data were defined as active residues.3,6 Pdx surface residues 28–31, Cys39 exhibiting severe line-broadening and significant chemical shift perturbation from NMR spectra (diamagnetic and paramagnetic) were defined as passive residues. These were not defined as active residues since they may not be involved in direct binding, but might be part of the binding interface. Similarly, for CYP101°, residues Cys357, Leu358 and Arg112 were defined as active site residues due to their proximity to heme and involvement in direct interaction with Pdx° from mutagenesis data.14,23,57 Nearby surface residues Lys344, Arg72 and His352 also implicated as important in binding interaction from mutagenesis data,13,50 but to a lesser extent than active residues, were defined as passive residues. Residue solvent accessibility for active and passive residues was calculated using NACCESS computer program (http://wolf.bms.umist.ac.uk/naccess). Segments of Pdx° and CYP101° that constituted these active and passive residues plus two sequential residues on either side of the active and passive residues were defined as flexible for purposes of docking.

RDCs were used to provide both inter- and intra-molecular orientation restraints in structure calculation. Two protocols for applying RDC restraints are available in HADDOCK: SANI and VEAN. While SANI is based on aligning the RDC represented bond vectors of both proteins according to the derived unique molecular alignment tensor, VEAN restrains structure orientations by the inter-vector projection angle restraints that do not depend on the accuracy of calculated alignment tensor. It has been shown that the docked results with combined protocol (SANI and VEAN) fit better with experimental RDC restraints and show better convergence.58–60 In this study, we used VEAN protocol in the first two docking stages and SANI protocol in the final refinement stage as described previously by van Dijk and others.58 The alignment tensor for SANI was calculated using the program PALES based on RDCs and protein structures.61 Intervector projection angle restraints for VEAN were generated with the python script provided in HADDOCK. Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) derived distances in Table 1 were used as unambiguous distance restraints in all three docking stages.

The docking was initiated with random starting orientations of Pdx° and CYP101° under AIR and orientational restraints. Rigid-body docking solutions were first generated by energy minimization followed by semi-flexible simulated annealing in torsion angle space and a final refinement in water in a 8 Å shell of TIP3P water molecules with 2 fs time steps. Both non-bonded and electrostatic energy terms were included in the calculation. Docked structures corresponding to the 20 best solutions with lowest intermolecular energies were generated and clustered based on a backbone rmsd tolerance of 2 Å. The lowest energy structure in this cluster was used subsequently for structure analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristen Holbrook for assistance with protein purification and Elina Tjioe for help with data analysis. This work was supported by a pilot project grant from the Center of Excellence for Structural Biology, University of Tennessee at Knoxville. TCP and SSP acknowledge support from PHS grant R01-GM44191.

Abbreviations

- Pdx

putidaredoxin

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- RDC

Residual Dipolar couplings

- CYP101

cytochrome P450cam

- Pdx°

oxidized putidaredoxin

- Pdxr

reduced putidaredoxin

- PdR

putidaredoxin reductase

- Adx

Adrenodoxin

- 2D

two-dimensional

Footnotes

Supplemental Material:

A table containing 1DNH RDC values measured in phage medium for the Pdx°/CYP101° complex and a figure showing changes in 15N NMR spectra of 15N labeled Asp Pdx° is available as supplementary material.

References

- 1.Denisov IG, Makris TM, Sligar SG, Schlichting I. Structure and chemistry of cytochrome P450. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2253–2277. doi: 10.1021/cr0307143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipscomb JD, Sligar SG, Namtvedt MJ, Gunsalus IC. Autooxidation and Hydroxylation Reactions of Oxygenated Cytochrome P-450cam. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:1116–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies MD, Sligar SG. Genetic-Variants in the Putidaredoxin Cytochrome-P-450(Cam) Electron-Transfer Complex - Identification of the Residue Responsible for Redox-State-Dependent Conformers. Biochemistry. 1992;31:11383–11389. doi: 10.1021/bi00161a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brewer CB, Peterson JA. Single Turnover Kinetics of the Reaction between Oxycytochrome-P-450cam and Reduced Putidaredoxin. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:791–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hintz MJ, Mock DM, Peterson LL, Tuttle K, Peterson JA. Equilibrium and Kinetic-Studies of the Interaction of Cytochrome-P-450cam and Putidaredoxin. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:4324–4332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holden M, Mayhew M, Bunk D, Roitberg A, Vilker V. Probing the interactions of putidaredoxin with redox partners in camphor p450 5-monooxygenase by mutagenesis of surface residues. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21720–21725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagano S, Shimada H, Tarumi A, Hishiki T, Kimata-Ariga Y, Egawa T, Suematsu M, Park SY, Adachi S, Shiro Y, Ishimura Y. Infrared spectroscopic and mutational studies on putidaredoxin-induced conformational changes in ferrous CO-P450cam. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14507–14514. doi: 10.1021/bi035410p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimada H, Nagano S, Ariga Y, Unno M, Egawa T, Hishiki T, Ishimura Y. Putidaredoxin-cytochrome P450(cam) interaction - Spin state of the heme iron modulates putidaredoxin structure. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9363–9369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roitberg A, Holden M, Mayhew M, Beratan D, Kurnikov I, Vilker V. Binding and electron transfer between putidaredoxin and cytochrome P450cam. Theory and experiments Abs Pap Am Chem Soc. 1998;215:U236–U237. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stayton PS, Sligar SG. The Cytochrome-P-450cam Binding Surface as Defined by Site-Directed Mutagenesis and Electrostatic Modeling. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7381–7386. doi: 10.1021/bi00484a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sligar SG, Debrunne Pg, Lipscomb JD, Namtvedt MJ, Gunsalus IC. Role of Putidaredoxin Cooh-Terminus in P-450 Cam (Cytochrome-M) Hydroxylations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:3906–3910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pochapsky TC, Ratnaswamy G, Patera A. Redox-Dependent H-1-Nmr Spectral Features and Tertiary Structural Constraints on the C-Terminal Region of Putidaredoxin. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6433–6441. doi: 10.1021/bi00187a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stayton PS, Poulos TL, Sligar SG. Putidaredoxin Competitively Inhibits Cytochrome-B5-Cytochrome-P-450cam Association - a Proposed Molecular-Model for a Cytochrome-P-450cam Electron-Transfer Complex. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8201–8205. doi: 10.1021/bi00446a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koga H, Sagara Y, Yaoi T, Tsujimura M, Nakamura K, Sekimizu K, Makino R, Shimada H, Ishimura Y, Yura K, Go M, Ikeguchi M, Horiuchi T. Essential Role of the Arg112 Residue of Cytochrome-P450cam for Electron-Transfer from Reduced Putidaredoxin. FEBS Letters. 1993;331:109–113. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80307-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pochapsky TC, Lyons TA, Kazanis S, Arakaki T, Ratnaswamy G. A structure-based model for cytochrome P450(cam)-putidaredoxin interactions. Biochimie. 1996;78:723–733. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(97)82530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unno M, Shimada H, Toba Y, Makino R, Ishimura Y. Role of Arg(112) of cytochrome P450(cam) in the electron transfer from reduced putidaredoxin - Analyses with site-directed mutants. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17869–17874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies MD, Qin L, Beck JL, Suslick KS, Koga H, Horiuchi T, Sligar SG. Putidaredoxin Reduction of Cytochrome P-450cam - Dependence of Electron-Transfer on the Identity of Putidaredoxins C-Terminal Amino-Acid. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:7396–7398. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stayton PS, Sligar SG. Structural Microheterogeneity of a Tryptophan Residue Required for Efficient Biological Electron-Transfer between Putidaredoxin and Cytochrome-P-450cam. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1845–1851. doi: 10.1021/bi00221a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pochapsky SS, Pochapsky TC, Wei JW. A model for effector activity in a highly specific biological electron transfer complex: The cytochrome P450(cam)-putidaredoxin couple. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5649–5656. doi: 10.1021/bi034263s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mouro C, Bondon A, Jung C, Hoa GHB, De Certaines JD, Spencer RGS, Simonneaux G. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance study of the binary complex of cytochrome P450cam and putidaredoxin: interaction and electron transfer rate analysis. FEBS Letters. 1999;455:302–306. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00898-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simonneaux G, Bondon A, Mouro C, Legrand N, Jung C. Carbon and 2D proton NMR studies of cytochrome P450camCO: Assignment of heme resonances and substrate interactions. FASEB J. 1997;11:A794–A794. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tosha T, Yoshioka S, Takahashi S, Ishimori K, Shimada H, Morishima I. NMR study on the structural changes of cytochrome P450cam upon the complex formation with putidaredoxin - Functional significance of the putidaredoxin-induced structural changes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39809–39821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tosha T, Yoshioka S, Ishimori K, Morishima I. L358P mutation on cytochrome P450cam simulates structural changes upon putidaredoxin binding - The structural changes trigger electron transfer to oxy-P450cam from electron donors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42836–42843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei JY, Pochapsky TC, Pochapsky SS. Detection of a high-barrier conformational change in the active site of cytochrome P450(cam) upon binding of putidaredoxin. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6974–6976. doi: 10.1021/ja051195j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pochapsky TC, Kostic M, Jain N, Pejchal R. Redox-dependent conformational selection in a Cys(4)Fe(2)S(2) ferredoxin. Biochemistry. 2001;40:5602–5614. doi: 10.1021/bi0028845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain NU, Pochapsky TC. Redox dependence of hyperfine-shifted C-13 and N-15 resonances in putidaredoxin. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:12984–12985. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain NU, Pochapsky TC. A new assignment strategy for the hyperfine-shifted C-13 and N-15 resonances in Fe2S2 ferredoxins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;258:54–59. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pervushin K, Riek R, Wider G, Wuthrich K. Attenuated T-2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hus JC, Marion D, Blackledge M. De novo determination of protein structure by NMR using orientational and long-range order restraints. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:927–936. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwahara J, Zweckstetter M, Clore GM. NMR structural and kinetic characterization of a homeodomain diffusing and hopping on nonspecific DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15062–15067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605868103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang C, Iwahara J, Clore GM. Visualization of transient encounter complexes in protein-protein association. Nature. 2006;444:383–386. doi: 10.1038/nature05201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonvin AMJJ, Boelens R, Kaptein R. NMR analysis of protein interactions. Curr Op Chem Biol. 2005;9:501–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mackereth CD, Simon B, Sattler M. Extending the size of protein-RNA complexes studied by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chembiochem. 2005;6:1578–1584. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jain NU, Venot A, Umemoto K, Leffler H, Prestegard JH. Distance mapping of protein-binding sites using spin-labeled oligosaccharide ligands. Prot Sci. 2001;10:2393–2400. doi: 10.1110/ps.17401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jain NU, Noble S, Prestegard JH. Structural characterization of a mannose-binding protein-trimannoside complex using residual dipolar couplings. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:451–462. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jain NU, Wyckoff TJO, Raetz CRH, Prestegard JH. Rapid analysis of large protein-protein complexes using NMR-derived orientational constraints: The 95 kDa complex of LpxA with acyl carrier protein. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:1379–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vlasie MD, Fernandez-Busnadiego R, Prudencio M, Ubbink M. Conformation of pseudoazurin in the 152 kDa electron transfer complex with nitrite reductase determined by paramagnetic NMR. J Mol Biol. 2008;375:1405–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poulos TL, Finzel BC, Gunsalus IC, Wagner GC, Kraut J. The 2.6-a Crystal-Structure of Pseudomonas-Putida Cytochrome-P-450. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:6122–6130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pochapsky TC, Jain NU, Kuti M, Lyons TA, Heymont J. A refined model for the solution structure of oxidized putidaredoxin. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4681–4690. doi: 10.1021/bi983030b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jain NU, Tjioe E, Savidor A, Boulie J. Redox-dependent structural differences in putidaredoxin derived from homologous structure refinement via residual dipolar couplings. Biochemistry. 2005;44:9067–9078. doi: 10.1021/bi050152c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sevrioukova IF. Redox-dependent structural reorganization in putidaredoxin, a vertebrate-type [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin from Pseudomonas putida. J Mol Biol. 2005;347:607–621. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rui LY, Pochapsky SS, Pochapsky TC. Comparison of the complexes formed by cytochrome P450(cam) with cytochrome b(5) and putidaredoxin, two effectors of camphor hydroxylase activity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3887–3897. doi: 10.1021/bi052318f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aoki M, Ishimori K, Fukada H, Takahashi K, Morishima I. Isothermal titration calorimetric studies on the associations of putidaredoxin to NADH-putidaredoxin reductase and P450cam. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1384:180–188. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Furukawa Y, Morishima I. The role of water molecules in the association of cytochrome P450cam with putidaredoxin - An osmotic pressure study. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12983–12990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aoki M, Ishimori K, Morishima I. NMR studies of putidaredoxin: associations of putidaredoxin with NADH-putidaredoxin reductase and cytochrome P450cam. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1386:168–178. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weigelt J. Single scan, sensitivity- and gradient-enhanced TROSY for multidimensional NMR experiments. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:10778–10779. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Hashimi HM, Valafar H, Terrell M, Zartler ER, Eidsness MK, Prestegard JH. Variation of molecular alignment as a means of resolving orientational ambiguities in protein structures from dipolar couplings. J Magn Res. 2000;143:402–406. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mukhopadhyay R, Wong LL, Lo KK, Pochapsky T, Hill HAO. A molecular level study of complex formation between putidaredoxin and cytochrome P450 by scanning tunnelling microscopy. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2002;4:641–646. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuznetsov VY, Poulos TL, Sevrioukova IF. Putidaredoxin-to-cytochrome P450cam electron transfer: Differences between the two reductive steps required for catalysis. Biochemistry. 2006;45:11934–11944. doi: 10.1021/bi0611154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karyakin A, Motiejunas D, Wade RC, Jung C. FTIR studies of the redox partner interaction in cytochrome P450: The Pdx-P450cam couple. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1770:420–431. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. Nmrpipe - a Multidimensional Spectral Processing System Based on Unix Pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson BA, Blevins RA. Nmr View - a Computer-Program for the Visualization and Analysis of Nmr Data. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:603–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00404272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Battiste JL, Wagner G. Utilization of site-directed spin labeling and high-resolution heteronuclear nuclear magnetic resonance for global fold determination of large proteins with limited nuclear overhauser effect data. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5355–5365. doi: 10.1021/bi000060h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Volkov AN, Worrall JAR, Holtzmann E, Ubbink M. Solution structure and dynamics of the complex between cytochrome c and cytochrome c peroxidase determined by paramagnetic NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18945–18950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603551103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kosen PA. Spin Labeling of Proteins. Meth Enzymol. 1989;177:86–121. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)77007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dominguez C, Boelens R, Bonvin AMJJ. HADDOCK: A protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1731–1737. doi: 10.1021/ja026939x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoshioka S, Takahashi S, Hori H, Ishimori K, Morishima I. Proximal cysteine residue is essential for the enzymatic activities of cytochrome P450(cam) Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:252–259. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2001.01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Dijk ADJ, Fushman D, Bonvin AMJJ. Various strategies of using residual dipolar couplings in NMR-driven protein docking: Application to Lys48-linked Di-ubiquitin and validation against N-15-relaxation data. Proteins-Struct Func Bioinform. 2005;60:367–381. doi: 10.1002/prot.20476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Dijk ADJ, Bonvin AMJJ. Solvated docking: introducing water into the modelling of biomolecular complexes. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2340–2347. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Dijk M, van Dijk ADJ, Hsu V, Boelens R, Bonvin AMJJ. Information-driven protein-DNA docking using HADDOCK: it is a matter of flexibility. Nucl Acids Res. 2006;34:3317–3325. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zweckstetter M, Bax A. Prediction of sterically induced alignment in a dilute liquid crystalline phase: Aid to protein structure determination by NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3791–3792. [Google Scholar]

- 62.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific; Palo Alto, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sayle RA, Milnerwhite EJ. RASMOL:biomolecular Graphics for all. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:374–376. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.