Abstract

The amygdala, important in forming and storing memories of aversive events, is believed to play a major role in debilitating tinnitus and hyperacusis. To explore this hypothesis, we recorded from the lateral amygdala (LA) and auditory cortex (AC) before and after treating rats with a dose of salicylate that induces tinnitus and hyperacusis-like behavior. Salicylate unexpectedly increased the amplitude of the local field potential (LFP) in the LA making it hyperactive to sounds ≥60 dB SPL. Frequency receptive fields (FRF) of multiunit (MU) clusters in the LA were also dramatically altered by salicylate. Neuronal activity at frequencies below 10 kHz and above 20 kHz was depressed at low intensities, but was greatly enhanced for stimuli between 10 and 20 kHz (frequencies near the pitch of the salicylate-induced tinnitus in the rat). These frequency-dependent changes caused the FRF of many LA neurons to migrate towards 10-20 kHz thereby amplifying activity from this region. To determine if salicylate-induced changes restricted to the LA would remotely affect neural activity in the AC, we used a micropipette to infuse salicylate (20 µl, 2.8 mM) into the amygdala. Local delivery of salicylate to the amygdala significantly increased the amplitude of the LFP recorded in the AC and selectively enhanced the neuronal activity of AC neurons at the mid-frequencies (10-20 kHz), frequencies associated with the tinnitus pitch. Taken together, these results indicate that systemic salicylate treatment can induce hyperactivity and tonotopic shift in the amygdala and infusion of salicylate into the amygdala can profoundly enhance sound-evoked activity in AC, changes likely to increase the perception and emotional salience of tinnitus and loud sounds.

Keywords: tinnitus, hyperacusis, salicylate, amygdala, auditory cortex, rat

1. Introduction

Subjective tinnitus, a phantom sound perception affecting 14% of the US population between the ages of 60 and 69 can be an extremely debilitating condition requiring medical treatment and intervention (De Ridder et al., 2006; Shargorodsky et al., 2010; Wazen et al., 1997). The tinnitus is generally associated with hearing loss and in addition is often accompanied by reduced sound tolerance (hyperacusis), an often undiagnosed condition (Gu et al., 2010; Nelson and Chen, 2004). In addition, severe tinnitus and hyperacusis are often accompanied by negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, distress and fear (Andersson et al., 2009; Cima et al., 2011; Savastano et al., 2007). Considerable effort has been directed at the identification of aberrant neural activity within the classical auditory pathway that could give rise to the phantom sound of tinnitus and hyperacusis. Human brain imaging studies have identified abnormal neural activity in many different structures within the auditory pathway of patients with tinnitus and hyperacusis, but aberrant activity has also been found outside the auditory pathway (Andersson et al., 2000; Arnold et al., 1996; Farhadi et al., 2010; Giraud et al., 1999; Langguth et al., 2006; Lockwood et al., 1998; Mirz et al., 1999; Mirz et al., 2000a; Reyes et al., 2002; Shulman et al., 1995).

A recurrent theme that has emerged from many brain imaging studies is that tinnitus pitch is correlated with expansion of the auditory cortex (AC) tonotopic map at frequencies at the edge of the hearing loss. Tonotopic map expansion in the AC has been considered as a neural correlate of tinnitus, much like somatotopic map expansion is for individuals with phantom limb pain (Karl et al., 2004; Montoya et al., 1998; Muhlnickel et al., 1998). Moreover, the AC is often hyperactive in participants with tinnitus and impaired loudness despite the fact the hearing loss reduces neural activity in the cochlea (Gu et al., 2010; Lockwood et al., 1998; Qiu et al., 2000). AC tonotopic map expansion and acoustic hyperactivity have also been observed in animals with behavioral evidence of tinnitus and hyperacusis induced by noise exposure and ototoxic drugs such as sodium salicylate (Engineer et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2011; Qiu et al., 2000; Salvi et al., 2000; Stolzberg et al., 2011; Wallhausser-Franke et al., 2003).

Aberrant structural and functional changes have also been observed in several brain regions outsides the classical auditory pathway, in particular parts of the limbic system which is involved in mood, motivation, emotion, memory and spatial navigation (Crippa et al., 2010; De Ridder et al., 2006; Lockwood et al., 1998; Mirz et al., 2000a; Schlee et al., 2009; Shulman et al., 1995; Vanneste et al., 2010). The amygdala, a limbic structure involved in processing aversive auditory stimuli (Zald and Pardo, 2002), has reciprocal connections with the medial geniculate body (MGB) and auditory cortex (AC) (Budinger et al., 2008; LeDoux, 2007; LeDoux, 2000; Romanski et al., 1993; Yang et al., 1993; Yang et al., 1999; Zhou et al., 1983). If the aberrant neural activity underlying tinnitus and hyperacusis is continuously associated with negative emotions processed by the amygdala, the aberrant activity may be amplified thereby increasing the perception and severity of tinnitus or hyperacusis (Jastreboff, 1990; Jastreboff, 2007; Moller, 2003; Rauschecker et al., 2010). The involvement of the amygdala is supported by clinical studies in which tinnitus, in particular pure tone tinnitus, was suppressed by infusion of amytal into the artery that provides the blood supply to this region (De Ridder et al., 2006). Conversely, salicylate, a drug which reliably induces tinnitus and hyperacusis-like behavior in rats, robustly increased activity in the amygdala as reflected by increased immunolabeling of Arc (alias arg3.1), a protein rapidly upregulated by increased synaptic activity (Mahlke and Wallhausser-Franke, 2004; Wallhausser-Franke et al., 2006). In addition, diffusion tensor imaging has shown that the white matter tracts between the amygdala and auditory cortex are more strongly coupled in those participants with high-frequency hearing loss-related tinnitus than controls (Crippa et al., 2010). While the amygdala is considered to play an important role in tinnitus and hyperacusis almost nothing is known about the electrophysiological changes that occur in this structure as a result of tinnitus and hyperacusis.

To address this issue, we measured the electrophysiological changes in the lateral amygdala (LA) after systemically administering a dose of salicylate that reliably induces tinnitus and hyperacusis-like behavior in rats. In a second experiment, salicylate was directly infused into the amygdala to determine how local drug application would affect neural activity in the AC. Our results show for the first time that systemic salicylate treatment caused the amygdala to become hyperactive and to change its tonotopic organization resulting in an overrepresentation of neurons tuned to 10–20 kHz, near the pitch of salicylate-induced tinnitus in the rat (Brennan and Jastreboff, 1991). Moreover, when salicylate was infused into the amygdala, it preferentially enhanced the responsiveness of AC neurons in the 10–20 kHz range.

2. Results

Normal auditory response of LA neurons

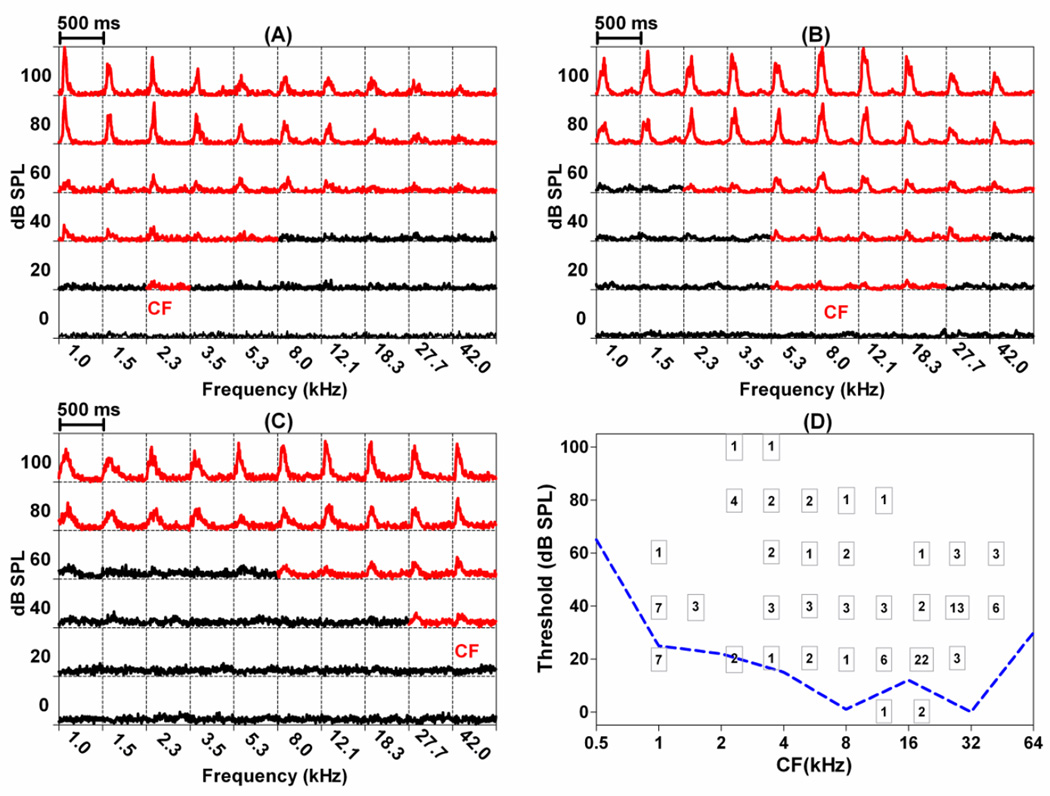

Many neurons in the LA responded to noise bursts and/or tone bursts. In total, recordings were obtained from 152 acoustically responsive MU clusters plus a few single units in the dorsal division of the LA, a region that receives direct input from the auditory thalamus and the AC. The majority of the units (141/152) showed good frequency tuning; 115 units had a single characteristic frequency (CF), the frequency with the lowest response threshold. The remaining 26 units (26/141) had double CFs. The FRF of each MU cluster was derived from a 6-intensity x 10-frequency matrix of PSTHs (Figure 1A). Each PSTH (5 ms bins, 500 ms time window) shows the spike rate (spikes/s) plotted as a function of post-stimulus time to 50 ms tone bursts (50 presentations). Frequency and intensity of the stimulus are shown on the abscissa and ordinate respectively in each panel. PSTHs that showed an increase in firing rate to the stimulus are presented in red; the red PSTHs therefore outline the excitatory FRF of each unit. Figure 1A–C shows the FRF, expressed as a matrix of PSTHs, of 3 representative MU clusters with a low-CF, mid-CF, and high-CF respectively. The CF of the MU cluster in Figure 1A, for example, was 2.3 kHz with a threshold of 20 dB SPL. Each of the squares in Figure 1D shows the number of units with that particular CF-threshold combination. The dashed line at the bottom of Figure 1D indicates behavioral audiogram of the rat (Heffner et al., 1994). The lowest thresholds of the MU clusters in the LA approximate the behavioral audiogram of the rat, indicating that signals that are barely audible to the rat are capable of activating units in the amygdala.

Figure 1.

Representative frequency-receptive fields of clusters recorded in the LA: (A) low-CF, (B) mid-CF, and (C) high-CF. Each square contains a PSTH (500 ms duration, 5 ms bin width) in response to tone bursts (50 ms duration) presented at the frequency and intensity indicated on the abscissa and ordinate respectively. PSTHs in red showed an increase in firing rate during the stimulus. (D) Number inside each square shows the number of MU clusters with a CF at the indicated frequency (abscissa) and threshold (ordinate). CF: characteristic frequency; FRF: frequency receptive field; PSTH: peristimulus time histogram. Dashed line shows rat behavioral audiogram (Heffner et al., 1994).

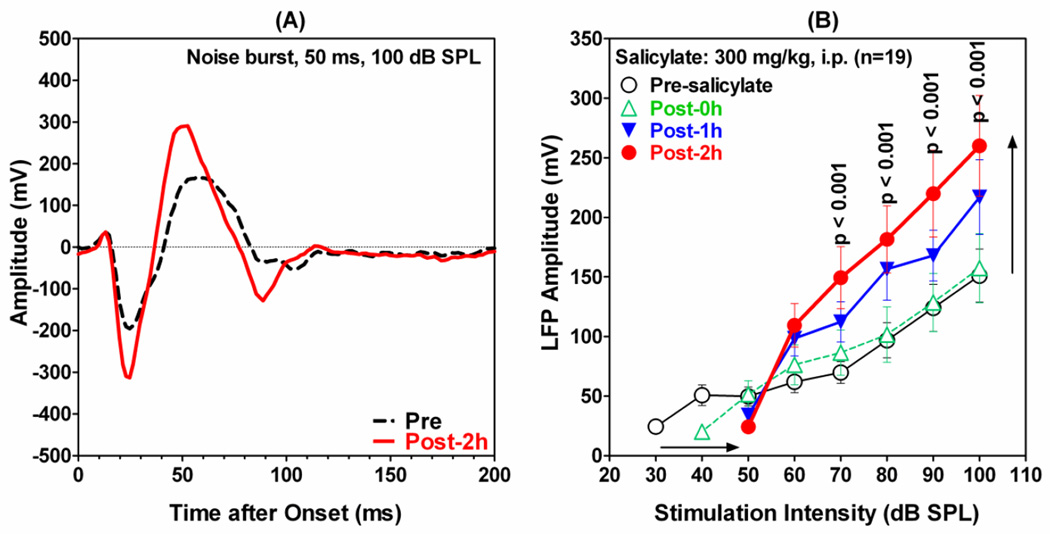

Salicylate enhances amplitude of the local field potential

Recordings were obtained from the LA before and after systemic administration of 300 mg/kg (i.p.) of sodium salicylate, a dose that reliably induced behavioral evidence of tinnitus and hyperacusis-like behavior in Sprague Dawley rats (Lobarinas et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2009) as well as tonotopic reorganization of the AC (Stolzberg et al., 2011). The systemic salicylate treatment had a profound effect on the LFP recorded from the LA. Figure 2A shows a typical LFP-waveform (black dashed line) recorded from the amygdala in response to noise burst (50 ms duration, 100 dB SPL). The main response consisted of an initial negative peak near 25 ms (N25) followed by a large positive peak around 50–60 ms (P50). The difference between N25 and P50 was used to quantify the amplitude of the LFP-amplitude. After salicylate injection, the LFP trough-to-peak response was significantly enhanced (red solid line); both the negative and positive peaks increased and the latency of P50 decreased slightly. Figure 2B presents the mean (±SEM) LFP amplitudes as a function of stimulus intensity before and starting at 0, 1 and 2 h post- treatment (note: here and elsewhere 0 h refers to data acquired during the first 28 minutes following the salicylate treatment). After salicylate treatment, the amplitude of the LFP gradually increased over time at intensities equal to or greater than 55 dB SPL. In contrast, the amplitude decreased at lower intensities and the intensity needed to elicit a detectable threshold response increased approximately 20 dB (horizontal arrow, Figure 2B). A two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant effect of treatment. A Bonferroni post-hoc analysis indicated that LFP amplitudes were significantly increased relative to pre-salicylate values from 70 to 100 dB SPL.

Figure 2.

Effect of systemic salicylate injection on LFP recorded from the amygdala in response to 50 ms noise burst. (A) A representative LFP waveform pre-salicylate (black dashed line) and 2 h following salicylate (red solid line); noise burst intensity 100 dB SPL. (B) Mean (±SEM; n=19) LFP amplitudes as a function of noise burst (50 ms) intensity before (open circle, black line) and 0 h, 1 h and 2 h after systemic administration of 300 mg/kg (i.p.) salicylate. Note significant amplitude enhancement (black vertical arrow) at intensities ≥60 dB SPL; salicylate increased thresholds approximately 20 dB (black horizontal arrow) and reduced LFP amplitudes at intensities below 60 dB SPL.

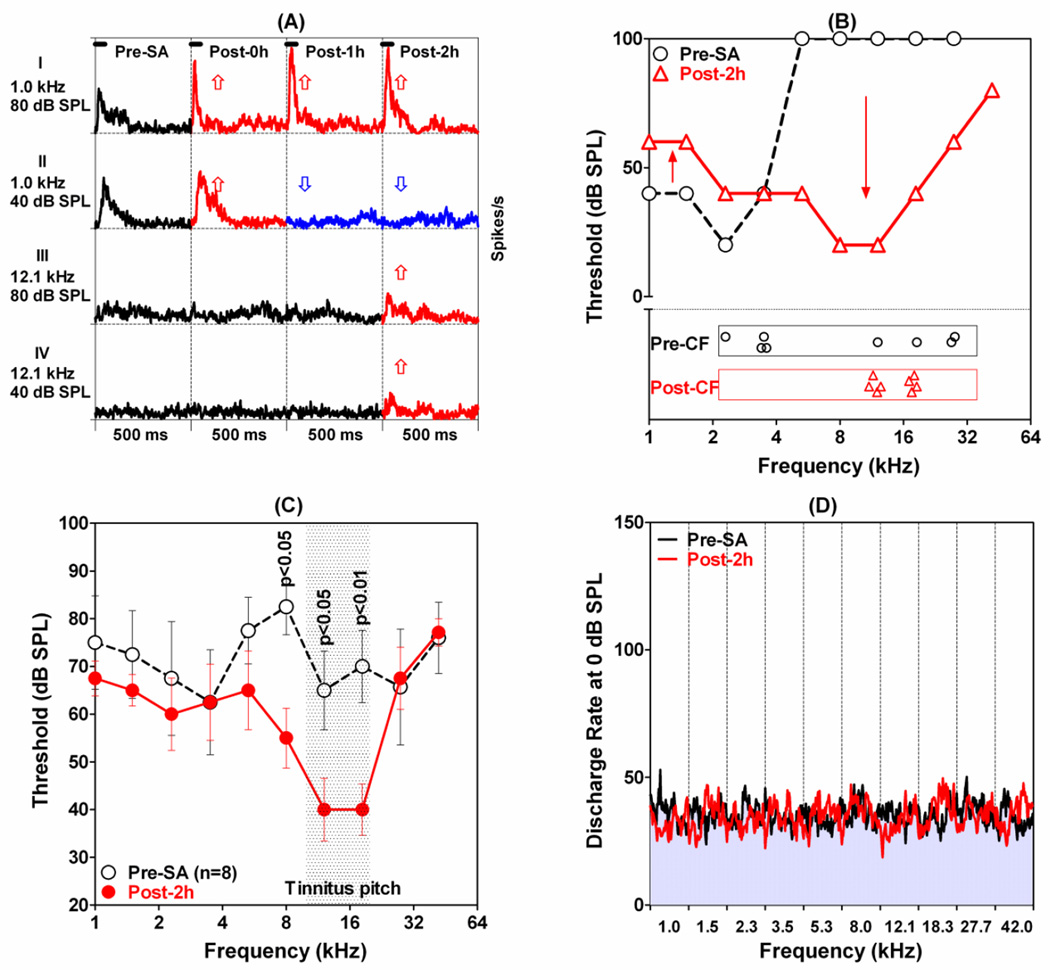

Salicylate alters LA tonotopy and excitability

Systemic salicylate treatment caused large changes in neural tuning and excitability in the LA as illustrated in Figure 3A. Prior to salicylate treatment, this MU cluster was highly responsive to low frequency stimuli as illustrated by the PSTHs to 1 kHz tone bursts presented at 40 and 80 dB SPL. In contrast, 12.1 kHz tones presented at 40 and 80 dB SPL produced little or no activity (Figure 3A, left column). The PSTHs to these same stimuli change dramatically following salicylate treatment (Figure 3A, right three columns). The PSTHs to 1 kHz tone bursts presented at 80 dB SPL all showed much larger responses after salicylate treatment. In addition, the shape of the PSTH at 80 dB SPL changed from a moderate onset response followed by sustained response to one with a large onset response followed by a very small sustained response (Figure 3A, top row), i.e., salicylate transformed the response pattern from tonic to phasic. The discharge rate at the peak of the PSTHs increased from 140 spikes/s pre-salicylate to 228, 268, and 268 spikes/s 0, 1 and 2h post-treatment. Similarly, the mean discharge rate (first 100 ms of the PSTHs) increased from 64 spikes/s pre-salicylate to 64, 103 and 106 spikes/s at 0, 1 and 2 h post-salicylate. Salicylate had much different effects on the PSTHs collected to 1 kHz tone bursts presented at 40 dB SPL. The PSTH increased slightly at 0 h post-treatment, but then largely disappeared at 1 and 2 h post-treatment. Salicylate effects at 12.1 kHz were nearly the opposite of those at 1 kHz. The MU cluster was largely unresponsive at 12.1 kHz at 0 and 1 h post-treatment, but surprisingly the PSTHs measured 2 h post-treatment had small to moderate onset response and sustained response. In this case, the MU cluster paradoxically became less responsive to low frequencies and more responsive to high frequencies. This frequency-dependent shift in excitability occurred over a broad range of frequencies and produced major changes in the FRF measured 2 h post-salicylate as shown in Figure 3B. Salicylate up-shifted low-frequency thresholds and downshifted high-frequency thresholds resulting in a right-shift in the FRF and its CF (see Fig. 3B). In this example, the CF was up-shifted 2 octaves or more. The panel at the bottom of Figure 3B shows the CFs of eight MU clusters before (black open circles) and after (red open triangles) salicylate treatment. Pre-salicylate CFs were distributed from 2 to 32 kHz. However, at 2 h post-salicylate the CFs were all clustered between 10 and 20 kHz. CFs above 20 kHz and CFs below 10 kHz were down-shifted and up-shifted respectively into the 10–20 kHz range. These CF up-shifts and downshifts are similar to those observed in the AC post-salicylate (Stolzberg et al., 2011) and provide the basis for tonotopic reorganization in the LA.

Figure 3.

The effects of system salicylate (300 mg/kg, i.p.) on neurons in the LA. (A): Typical changes observed in PSTHs (tone bursts, 500 ms duration, 5 ms bin width) recorded from MU clusters in the LA before (left column) and 0 h, 1 h and 2 h after salicylate treatment (second, third and fourth column from left). Row I (80 dB SPL, 1 kHz): Note enhanced firing rate (red PSTHs, up arrow) after salicylate injection. Row II (1 kHz, 40 dB SPL): PSTH showed a slight enhancement (red) shortly after salicylate treatment (red PSTH, up arrow) followed by a large decrease in PSTHs amplitude (blue PSTHs, down arrow) 1 h and 2 h post-salicylate. Row III (12.1 kHz, 80 dB SPL) and Row IV (12.1 kHz, 40 dB SPL): PSTHs showed little or no response before salicylate and 0 and 1 h post-salicylate (black PSTHs); note increase in PSTH amplitude 2 h post-salicylate (red). (B) FRF of the MU cluster shown in panel A before (open circle dashed line) and 2 h post-salicylate (red open triangle, solid line). Salicylate caused an increase in low-frequency thresholds (up arrow), decrease in high-frequency thresholds (down arrow), migration of FRF toward the high frequencies and up-shift in CF. Lower portion of panel B shows CFs of 8 MU cluster in LA pre-salicylate (black open circles) and 2 h post-salicylate (red open triangles). Note up-shift of low CFs and down shift of high CF MU clusters into the 10-20 kHz range. (C) Mean (±SEM) FRFs of all 8 MU clusters (10 test frequencies, 1 to 42 kHz, 50 ms tone bursts) before (open black circles, dashed line) and 2 h post-salicylate (filled red circles, solid line). Salicylate: 300 mg/kg (i.p.). (D). Each column shows the mean PSTHs of all 8 MU clusters measured at 0 dB SPL (subthreshold) at 10 test frequencies from 1 to 42 kHz. Mean firing rate at subthreshold intensity essentially unchanged after 300 mg/kg salicylate (i.p.).

The FRF of the eight MU clusters (see CFs in bottom panel of Figure 3B) were combined into a mean pre-salicylate FRF by computing the average thresholds at each frequency and plotting the average threshold as function of frequency (Figure 3C, open circles). The mean (±SEM) FRF was computed for the same eight MU clusters at 2 h post-salicylate (Figure 3C, filled red circles). The mean pre-salicylate thresholds are uniformly high because thresholds are averaged across FRFs with CFs scattered between 2 and 32 kHz (Figure 3B, bottom panel). Since salicylate up-shifted or downshifted the CFs of the MU clusters towards the mid-frequencies, the mean FRF thresholds 2 h post-salicylate were significantly lower than the pre-salicylate thresholds at 8, 12.1 and 18.3 kHz (Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, p value shown in Figure 3C). The overall increase in sensitivity in the mid-frequency region matches the tinnitus pitch reported in rats with behavioral evidence of tinnitus (Brennan and Jastreboff, 1991; Kizawa et al., 2010; Lobarinas et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2007).

Although systemic salicylate increased suprathreshold LFP amplitudes and firing rates, neural activity near threshold appeared to be largely unaffected. To confirm this impression, we computed the mean (8 MU clusters) PSTHs obtained at 0 dB SPL of 50 ms tone bursts presented at frequencies from 1 to 42 kHz. Since 0 dB SPL was well below the average threshold (Figure 3C) and since the 50 ms tone burst was off for 90% of measurement window, the firing rates largely reflect spontaneous activity. Each column in Figure 3D shows the mean PSTHs before (gray with black line) and 2 h after salicylate (red line). The mean firing rates in the LA were largely unchanged following systemic salicylate. Even though systemic salicylate caused a large increase in suprathreshold activity, it had little or no effect on subthreshold firing rates (i.e., spontaneous activity).

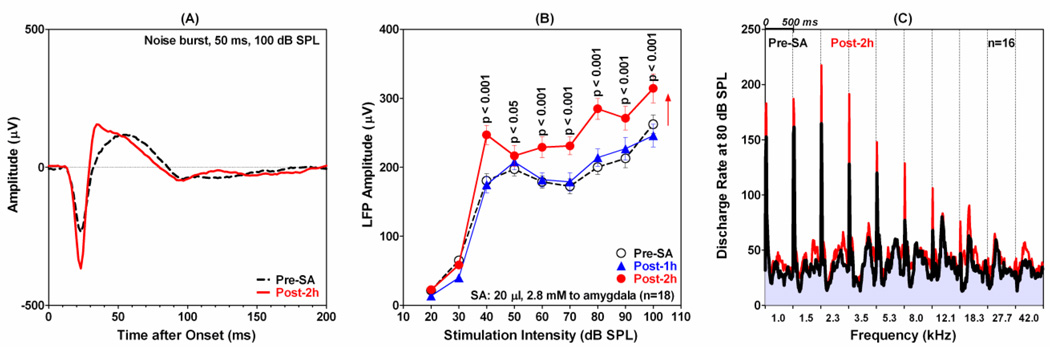

Salicylate into LA causes AC hyperactivity

Systemic salicylate induced changes in the LA (Figures 2–3) similar to those recently observed in the AC (Stolzberg et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2009). Previous reports have suggested that salicylate-induced plasticity in the AC may results from the drug’s effects on the amygdala (Mahlke and Wallhausser-Franke, 2004; Wallhausser-Franke et al., 2006). To explore this possibility, we infused salicylate (20 µl, 2.8 mM) directly into the LA while recording from MU clusters in the ipsilateral primary AC. Figure 4A shows the typical LFP waveform recorded from the AC before and after local infusion of salicylate into the ipsilateral LA. The pre-salicylate LFP waveform in response to 50 ms noise burst presented at 100 dB SPL consisted of a large, narrow negative peak near 20 ms followed by a smaller, broader, positive peak around 52 ms (Figure 4A, black dashed line). The amplitude of the LFP in the AC became considerably larger after salicylate was infused into the LA (Figure 4A, red line). In addition, the latency of the positive peak decreased from approximately 53 ms to 35 ms and the total duration of response decreased. The mean (±SEM) amplitude-intensity function for the AC LFP was computed using the trough-to-peak amplitude of the response (Figure 4B). Infusion of salicylate into the LA increased the amplitude of the AC LFP at 2 h post-treatment; the increases were significant for all intensities from 40 to 100 dB SPL (Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc analysis). Importantly, infusion of salicylate into the LA had no effect on the AC LFP threshold; this is fundamentally different from the 20 dB LFP threshold shifts seen after the systemic salicylate treatment.

Figure 4.

The effect of infusing 20 µl of 2.8 mM salicylate into the LA on the response properties of the AC. (A) Representative LFP waveforms to 50 ms tone burst presented at 100 dB SPL before (black dash line) and 2 h post-salicylate (red solid line). Note increase in LFP amplitude post-salicylate. (B): Mean (n=18, ±SEM) LFP amplitudes as a function of noise burst intensity (50 ms) before (open circles, dashed line) and 1 h (filled diamonds) and 2 h post-salicylate (filled circles). Note significant enhancement of LFP amplitudes from 40-100 dB SPL and lack of threshold shift. (C) Mean (n=16) PSTHs (500 ms duration, 10 ms bin width) to 50 ms tone bursts presented at 80 dB SPL at frequencies from 1 to 42 kHz. Pre-salicylate PSTHs (black line/gray body) superimposed on red PSTHS (2 h post-salicylate). Tone-evoked firing rates 2 h post-salicylate are higher than pre-salicylate firing rates, i.e., red regions above gray-black PSTHs show increases in firing rate.

Recordings were obtained from 16 MU clusters in the AC before and after infusing salicylate into the LA. Salicylate increased the firing rate of most MU clusters at suprathreshold intensities consistent with the LFP results. To illustrate the overall trends, the mean PSTHs (500 ms duration, 10 ms bin width) from all 16 MU clusters were averaged together for each frequency-intensity combination in data acquisition matrix. Figure 4C shows the mean (n=16) PSTHs (500 ms duration, 10 ms bin width) to 50 ms tone bursts presented at 80 dB SPL at frequencies from 1 to 42 kHz. The pre-salicylate PSTHs (black line/gray body) were superimposed on the red PSTHS obtained 2 h post-salicylate. Since the mean firing rates 2 h post-salicylate were greater than the mean rates pre-salicylate, the red regions that lie above the gray-black PSTHs represent the increase in firing rate 2 h post-salicylate. It is clear from Figure 4C, that the mean firing rates 2 h post-salicylate are greater than the mean pre-salicylate firing rates consistent with the suprathreshold LFP amplitude enhancement (Figure 4B).

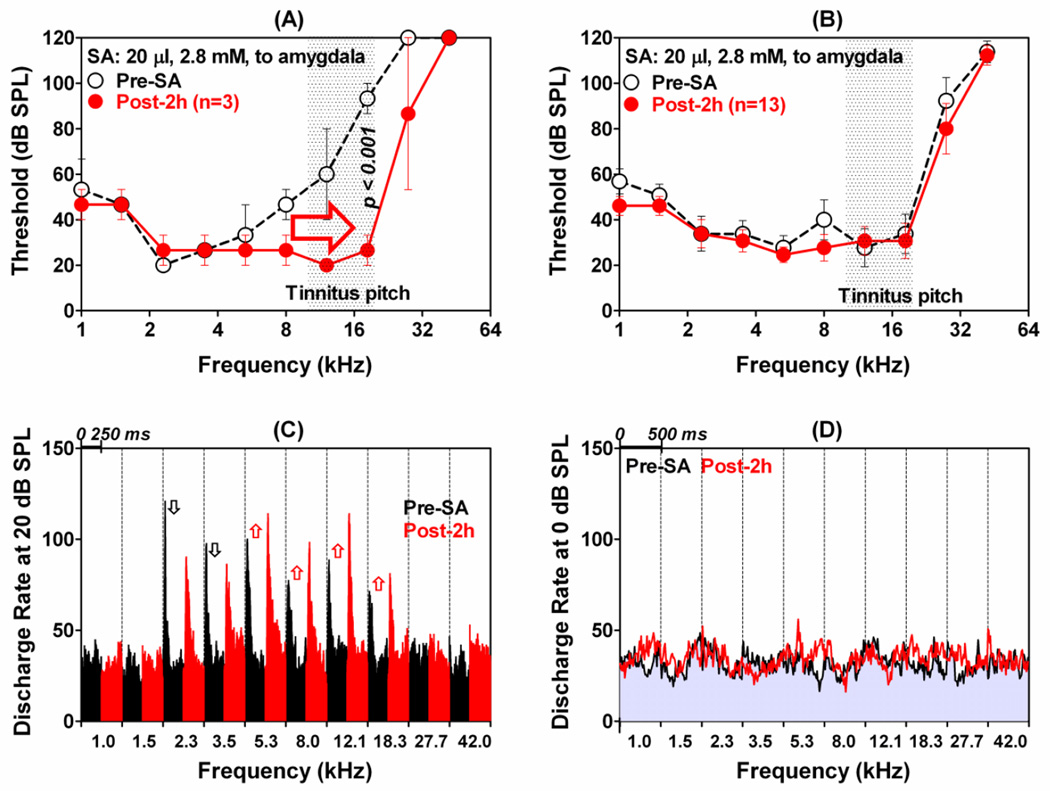

Salicylate infusion into LA changes AC tuning

Responses of 16 MU clusters in the AC were recorded before and after salicylate was infused into the LA. Only three of the AC MU clusters showed significant FRF expansion; the remaining 13 were largely unaffected by salicylate infusion into the LA. All three of the AC MU clusters that were affected by salicylate had low CFs. The average (±SEM) FRFs of these three AC clusters before and 2 h after infusing salicylate into the LA are shown in Figure 5A. Salicylate infusion caused the mean FRF to expand toward the high frequencies. The high-frequency edge of the FRF shifted rightward by much as 1 to 2 octaves. This expansion occurred because thresholds from 8 to 27.7 kHz decreased substantially. In contrast, thresholds below 8 kHz were largely unchanged. Figure 5B presents the mean (±SEM) FRF thresholds of the remaining 13 AC units before and after local salicylate treatment. Pre- and post-FRFs were largely unaffected by infusion of salicylate into the LA.

Figure 5.

The effects of infusing 20 µl of 2.8 mM of salicylate into LA on neuronal activity in AC. (A): Averaged (±SEM) FRFs of three low-CF MU clusters in the AC before (open circles, dashed line) and 2 h post-salicylate (filled circles, solid line). Note decrease in threshold and expansion along high-frequency side of the FRFs after infusing salicylate into the LA. (B): Averaged (±SEM) FRF of 13 MU clusters in the AC that showed no change in their frequency-threshold tuning after infusing salicylate into the LA. (C): Mean PSTHs (250 ms duration, 1 ms bin width) of the 13 MU clusters in panel B to tone bursts presented at 20 dB SPL. Each column shows the mean PSTH before (black, left) and 2 h post-salicylate (red, right) at frequencies from 1 to 42 kHz. Note increase in mean discharge rates from 5.3 to 18.3 kHz (up arrows) and decreased firing rates at 2.3 and 3.5 kHz (down arrows). (D) Mean PSTHs (500 ms duration, 10 ms bin width) for 13 MU clusters to tone bursts presented at 0 dB SPL (~20 below mean AC thresholds). Mean PSTHs before (gray with black line) and 2 h after (red line) salicylate infused into LA. Each column shows the mean PSTH at frequencies from 1 to 42 kHz; mean discharge rates at subthreshold intensity largely unchanged by salicylate.

Salicylate infusion into LA induced AC hyperactivity

Although the mean FRFs were virtually unchanged, infusion of salicylate into the LA increased suprathreshold firing rates to mid-frequency stimuli. To illustrate the global changes in firing rate at suprathreshold levels, Figure 5C presents averaged PSTHs (250 ms duration, 1 ms bin width from the 13 AC MU clusters in response to 20 dB SPL tone bursts ranging in frequency from 1 to 42 kHz. The black and red PSTHs show the results obtained before and 2 h after salicylate infusion into the LA. Two hours after salicylate infusion into the LA, the AC-neurons showed an enhancement of the peak firing rate at frequencies from 5.3 to18.3 kHz (up arrows), but a decrease in the peak rate at 2.3 and 3.5 kHz (down arrows). These results show that local application of salicylate into the LA mainly enhanced the firing rate of AC neurons at the mid–frequencies at sound intensities slightly above threshold whereas at much high intensities the enhanced firing occurred over a broader range of frequencies (Figure 4C).

Mean PSTHs were also computed at 0 dB SPL for the 13 MU clusters in the AC, an intensity roughly 20 dB below the mean AC threshold (Figure 4B, 5A–B). Each column in Figure 5D shows the mean PSTHs (500 ms duration, 10 ms bin width) before (gray with black line) and 2 h after salicylate (red line) was locally applied to the LA. The mean firing rates at 0 dB SPL (sub or near threshold) were largely unchanged by infusion of salicylate into the AC. Taken together, these results indicate that infusion of salicylate into the LA increases suprathreshold firing rates in the AC, but not subthreshold firing rates (Figure 5D) consistent with LFP input/output functions (Figure 4B).

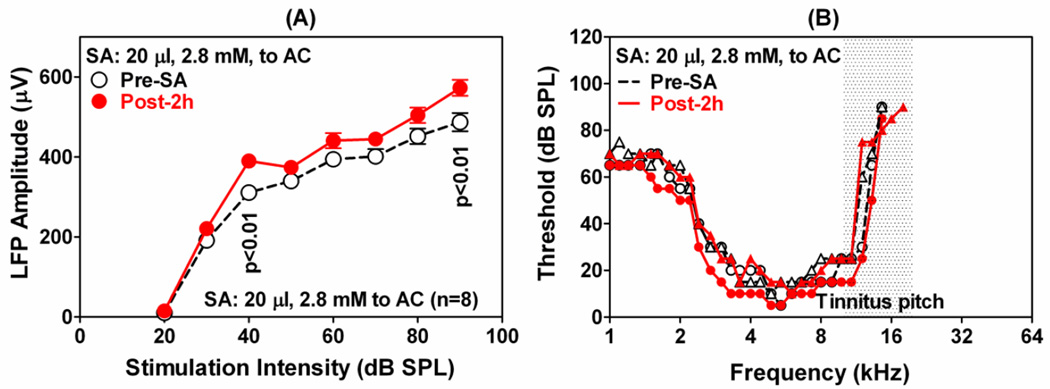

Salicylate Application to AC

To determine the direct effects of salicylate on the AC, LFP and MU clusters were recorded from the AC before and after application of 20 µl of 2.8 mM salicylate on the AC. Figure 6A shows the mean (±SEM) LFP input/output functions obtained with 50 ms noise bursts before and 2 h after salicylate treatment. Local application of salicylate has no effect on the threshold; however, LFP amplitudes increased at suprathreshold levels, but the increases only reached significance at 40 and 90 dB SPL (Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc analysis). Direct infusion of salicylate on the AC failed to induce major changes in the FRFs of MU clusters in the AC. Figure 6B shows representative FRFs of two MU clusters in the AC pre- (open black symbols) and post-salicylate (filled red symbols). The FRFs showed only minor changes 2 h after salicylate treatment.

Figure 6.

Change in AC activity when salicylate was applied to the AC. (A): Mean (n=8, ±SEM) LFP amplitudes as a function of noise burst (50 ms) intensity; significant changes in amplitude indicated on the graph. (B): Representative FRFs of 2 AC neurons pre-salicylate (black) and 2 h post-salicylate (red). One MU cluster showed a slight FRF-expansion on both sides (opened and filled circles) and one which did not (open and filled triangles). Salicylate: 20 µl at 2.8 mM. Stimulation: tone bursts of 50 ms.

3. Discussion

The neural networks underlying severe tinnitus and hyperacusis are thought to involve centers outside the classical auditory pathway such as the amygdala, which assigns emotional significance to sensory stimuli (Crippa et al., 2010; De Ridder et al., 2006; Jastreboff and Jastreboff, 2006; Lockwood et al., 1998; Mirz et al., 2000b; Vanneste et al., 2010). Previous neuroanatomical studies have shown that the activity markers, c-fos and arg3.1, are strongly upregulated in the amygdala by high doses of salicylate that induce tinnitus and hyperacusis-like behaviour (Brennan and Jastreboff, 1991; Lobarinas et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2011; Mahlke and Wallhausser-Franke, 2004; Wallhausser-Franke et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2007). The results presented here show for the first time that systemic salicylate induces profound electrophysiological changes in the LA. As expected, systemic salicylate increased LFP acoustic thresholds approximately 20 dB; however, at suprathreshold intensities LFP amplitudes increased by nearly 70% (Figure 2B). Second, systemic salicylate produced large frequency-dependent changes in the responses of MU clusters; firing rates to mid-frequency stimuli (10–20 kHz) increased substantially whereas responses to lower and higher frequencies decreased. Third, the CFs of low-frequency MU clusters up-shifted to the mid-frequencies whereas the CFs of high-frequency MU clusters down-shifted. These shifts altered the tonotopy of the LA making it more responsive to the mid-frequencies and less responsive to lower and higher frequencies. To determine if the salicylate-induced changes in the LA would affect the AC, salicylate was infused into the LA while recording from the AC. Unlike systemic administration, local delivery of salicylate into the LA did not alter AC LFP thresholds (Figure 4B) or MU clusters thresholds (Figure 5B). However, infusion of salicylate into the LA substantially increased AC suprathreshold LFP amplitudes (Figure 4B) and suprathreshold MU firing rates (Figures 4C and 5C), but not subthreshold firing rates (Figure 5D). Finally, when salicylate was applied directly to the AC, the thresholds of LFP and MU clusters in the AC were largely unaffected. However, LFP amplitudes in the AC increased slightly (Figure 6A).

Thresholds

When salicylate was administered systemically, LFP thresholds in the LA increased approximately 20 dB (Figure 2B). Others have reported thresholds shifts of similar magnitude at the level of the cochlea, IC and AC after systemic salicylate treatments (Ma et al., 2006; Muller et al., 2003; Ochi and Eggermont, 1996; Silverstein et al., 1967). Likewise, when salicylate was applied directly to the cochlea it also increased thresholds in the cochlea, IC and AC (Sun et al., 2009). Unlike previous reports, our new findings show that when salicylate was applied to either the AC or LA there was little or no change in LFP thresholds in the AC. In other words, central application with salicylate did not cause hearing loss. Taken together, these results imply that the threshold shifts in the LA following systemic administration result from cochlear hair cell or neural dysfunction (Chen et al., 2010; Muller et al., 2003; Silverstein et al., 1967).

Salicylate increases central gain

Systemic salicylate reduces neural activity in the cochlea and auditory midbrain (Chen et al., 2010; Muller et al., 2003; Silverstein et al., 1967; Sun et al., 2009). Despite this reduction, neural responses in the LA were enhanced at suprathreshold levels (Figure 2–3) similar to what has been reported in the AC (Lu et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2009). Likewise, systemic salicylate increased immunolabeling of neural activity and neuroplasticity markers in the AC and LA (Mahlke and Wallhausser-Franke, 2004; Wallhausser-Franke et al., 2003). The amplitude enhancements seen in both the LA and AC after systemic salicylate are likely to involve the loss of inhibition. Salicylate suppresses GABAergic inhibition in the spinal cord, hippocampus and auditory cortex (Gong et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2005). Iontophoresis of GABAa antagonists into the AC increased driven discharge rates, lowered thresholds and expanded the excitatory response areas of many AC neurons (Wang et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2002); these electrophysiological changes are similar to those observed after systemic salicylate treatment. The LA also contains numerous GABAa receptors (McDonald and Mascagni, 1996) and sensory responses in the amygdala are enhanced by GABAa antagonists (Faingold et al., 1985). Thus, the enhanced activity seen in the LA following systemic salicylate could be due to a reduction of GABAa mediated inhibition. The salicylate-induced deafferentation may also play a certain role in the central enhancement of auditory response since the central enhancement was also observed after cochlear damage by intense noise or ototoxic agents (Popelar et al., 1987; Qiu et al., 2000; Salvi et al., 1990; Salvi et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2008; Syka et al., 1994), although local salicylate application on the round window or systemic salicylate treatment in the rats anesthetized with isoflurane, which enhances GABA activity, did not enhance response of the auditory cortex (Sun et al., 2009).

While systemic salicylate increases excitability in both the AC and the LA, it is unclear if the changes in these two regions are completely independent or if the alteration in one region affects the other. Some insights into this issue may be gleaned by comparing the relative increase in AC LFP amplitude after applying the same dose of salicylate into the LA and AC (Figure 4B vs. 6A). Inspection of the data indicates that the amplitude increase of AC response was proportionately larger when the salicylate was applied to the LA than to the AC itself.

Peripheral contribution to the salicylate-induced tonotopic plasticity

Following systemic salicylate treatment, the FRFs of very low CF and very high CF MU clusters in the LA shifted their CFs into the 10–20 kHz region resulting in an over representation of neurons located near the pitch of the salicylate-induced tinnitus in the rat (Figure 3B–C). This change in LA tonotopy is very similar to that reported in the AC after systemic salicylate treatment (Stolzberg et al., 2011). The change in LA and AC tonotopy appears to be related to a frequency-dependent loss of cochlear amplification in outer hair cells (Chen et al., 2010; Oliver et al., 2001; Stolzberg et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2008) which was less severe near 16 kHz (Stolzberg et al., 2011). As previously noted “Such a rapidly altered profile of cochleoneural output to the brain would be incongruous with established tonotopic maps in central auditory structures providing an impetus for central mechanisms of neuronal plasticity to accommodate the new profile of input” (Stolzberg et al., 2011). Indeed, the expansion of FRF tuned to 10–20 kHz is consistent with the pitch of salicylate induced tinnitus observed in rats (Jastreboff, 1994; Yang et al., 2007) as wells as models of tinnitus based on tonotopic reorganization (Engineer et al., 2011; Muhlnickel et al., 1998; Norena and Eggermont, 2005; Stolzberg et al., 2011). In contrast to the large changes following systemic treatment, when salicylate was infused into the AC or LA, AC neurons showed little change in threshold and tuning.

Subthreshold firing rates

Increases and decreases in spontaneous rate or abrupt changes in spontaneous rate along the tonotopic gradient have been proposed as possible mechanisms for tinnitus (Chen and Jastreboff, 1995; Kaltenbach, 2006; Kiang et al., 1976; Mulders et al., 2011; Salvi et al., 1978). Both increases and decreases in spontaneous rate have been observed at different locations along the auditory pathways following systemic administration at different doses of salicylate that induce threshold elevations and behavioral evidence of tinnitus (Chen and Jastreboff, 1995; Evans et al., 1981; Ma et al., 2006; Muller et al., 2003). Salicylate also increased c-fos expression, a neural activity marker, in the amygdala and AC of quiet reared gerbils (Mahlke and Wallhausser-Franke, 2004; Wallhausser-Franke et al., 2003). Despite the increase in c-fos, systemic salicylate failed to produce an overall change in subthreshold firing rates of MU clusters in the LA (Figure 3D). Likewise, local infusion of salicylate into the LA did not alter the average firing rate of MU clusters in the AC (Figure 5D). Taken together, our results indicate that systemic and local salicylate have their greatest effects on suprathreshold firing rates in the LA and AC.

Role of the Amygdala

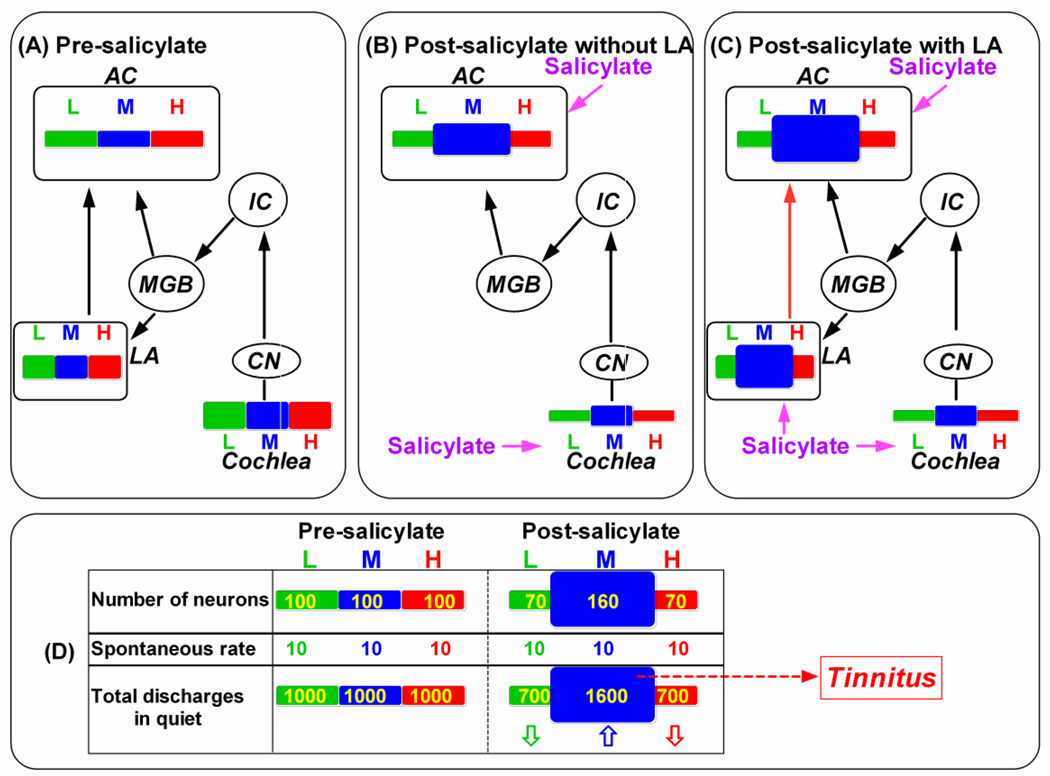

The amygdala and other parts of the limbic system have been implicated in tinnitus and hyperacusis in particular in the pure tone tinnitus (De Ridder et al., 2006; Jastreboff, 2007; Levitin et al., 2003; Mahlke and Wallhausser-Franke, 2004; Moller, 2003; Wallhausser-Franke et al., 2003). According to the neurophysiological model of Jastreboff, tinnitus and hyperacusis signals are generated in the auditory pathway. If the neural activity associated with tinnitus and hyperacusis is classified as a neutral signal, it is ignored; however, if the aberrant neural activity is associated with danger or distress, the limbic system amplifies the aberrant auditory activity increasing its perceptual salience (Jastreboff and Jastreboff, 2006; Jastreboff, 2007). A simplified scheme illustrating how the LA contributes to hyperactivity in the auditory cortex is shown in Figure 7. For simplicity, only the cochlea, cochlear nucleus (CN), inferior colliculus (IC), medial geniculate body (MGB) and AC in the auditory pathway are shown. Figure 7A illustrates the tonotopic area within the cochlea, LA and AC activated by low, middle and high frequencies under normal conditions (pre-salicylate); the width of each bar indicates the size of the tonotopic area. The amount of excitation within each frequency region is indicated by its height. Figure 7B illustrates how the system would respond following systemic salicylate treatment when the LA is removed or inactivated. Salicylate enters both the cochlea and central nervous system, but has different effects. Salicylate suppresses the overall neural output of the cochlea, but the suppression is less at mid-frequencies (blue) than low (green) or high (red) frequencies creating a bandpass-like output as we previously reported (Stolzberg et al., 2011). Salicylate reduces GABA-mediated inhibition in the AC (Lu et al., 2011; Su et al., 2009). The salicylate actions may result in two major changes. One is an expansion of mid-frequencies of the tonotopic map (increased width of blue bar) and the other is an increase in excitability (increased height of blue bar) as previously reported (Stolzberg et al., 2011). Figure 7C illustrates how the system responds to systemic salicylate when the LA is added back into the model. In addition to its effects on the cochlea and AC, salicylate also reduces GABA-mediated inhibition in the LA and other regions of the limbic system (Gong et al., 2008). Salicylate increases excitability of neurons in the LA (increased height of blue bar) and expands the mid-frequency region of the tonotopic map (increased width of blue bar, Figure 7C) which further enhances the salicylate effects on the AC (Figure 7C); this interpretation is supported by the results in Figure 4. According to this scheme, the salicylate-induced reduction of GABA-mediated inhibition in the LA further amplifies the effects that are propagated from the cochlea up to the AC. The model schematized in Figure 7A–C could potentially account for severity of tinnitus and hyperacusis associated with chronic stress. Stressors that reduce GABA function in the amygdala or other parts of the limbic system (Amano et al., 2010; Duvarci and Pare, 2007; Holm et al., 2011; O’Mahony et al., 2011; Reznikov et al., 2009) could increase the severity of tinnitus and hyperacusis. The increased auditory evoked response (suprethreshold response) may account for the hyperacusis, which is defined as physical discomfort resulting from an exposure to a moderate sound (Jastreboff and Jastreboff, 2006). How the results are related to the generation of tinnitus? Salicylate induces migration of frequency receptive field of neurons towards the mid-frequency region or the “tinnitus region”. In other words, salicylate exposure results in an increased number of neurons which turn to represent the “tinnitus-frequency”. Although the mean spontaneous discharge rate may not be affected (see Fig. 3D), the total discharges of neurons which represent the “tinnitus-frequency” can be significantly higher than those representing any other frequency leading to imbalance of activity in the brain leading to a sound sensation in quiet --- tinnitus. Figure 7D illustrates how salicylate induces tinnitus. Under normal condition (pre-salicylate), the total discharges of neurons in quiet in the AC/LA in different tonotopic regions (neuron number x spontaneous discharge rate) should be equivalent (100 x 10 = 1000). After exposure to a high dose of salicylate, more neurons turn to respond to mid-frequencies leading to an increased number of neurons in the mid-frequency region and a decreased number of neurons in the low- and high-frequency regions. The total discharges in the mid-frequency region in this model increase from 1000 to 1600 even though the mean spontaneous discharge rate may not be affected. The total discharges in the low- and high-frequency regions decrease from 1000 to 700. The relatively more total discharges in the mid-frequency region in quiet may be accepted as a sound stimulation --- the sound sensation without a sound stimulation, a phantom sound sensation.

Figure 7.

Highly simplified scheme showing the lateral amygdala (LA) and the auditory pathway that includes the cochlea, cochlear nucleus (CN), inferior colliculus (IC), medial geniculate body (MGB) and auditory cortex (AC). Tonotopy of the cochlea, LA and AC is indicated by bars in different colors. Extent of cochlea, LA and AC is occupied by low (L = green), middle (M = blue) and high (H = red) frequencies indicated by width of rectangle; magnitude of excitation within each frequency region indicated by height of rectangle. (A) Pre-salicylate condition showing region extent and magnitude of activity with the cochlea, LA and AC. (B) Post-salicylate scheme with the LA removed. Salicylate causes overall decrease in activity in cochlea; decreases is greatest at low and high frequencies and least at mid-frequencies (10-20 kHz). Note expansion of mid-frequency region in AC and moderate increase in excitation. (C) Post-salicylate scheme including LA. Same as in panel B except that now salicylate also increases activity in mid-frequency region of LA; hyperactivity in mid-frequency region of LA sent to corresponding region of AC further enhancing activity in the mid-frequency region of the AC. (D) Relative discharges (total discharges) in quite in the central auditory system (neuron number x spontaneous discharge rate) are equivalent across tonotopic regions under normal condition (pre-salicylate). However, an increased number of discharges in the mid-frequency region (up arrow) and a decreased number of discharges in the low- and high-frequency regions (down arrows) are expected after a high dose of salicylate due to the change of numbers of neurons which tune to the frequency. The relatively more discharges in the mid-frequency region in quiet may be accepted as a sound stimulation --- tinnitus.

A limitation of this study is that the data were collected in the anesthetized animals and the salicylate-induced tinnitus was not measured, although the salicylate injection at the dosage of 300 mg/kg was reported reliably to induce tinnitus (Lobarinas et al., 2004).

4. Experimental procedure or methods and materials

Subjects

Twenty-five Sprague–Dawley rats (male, 2–6 months) were used in this study. Animals were housed in the University at Buffalo laboratory animal facility; colony room was maintained at 71°F with 12 h/12 h light-dark cycle. All the procedures used in this project were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (HER05080Y) at the University at Buffalo and carried out in accordance with NIH guidelines.

Salicylate treatments

In the first experiment, recordings were made from neurons in the LA before and after systemic treatment with sodium salicylate (i.p., 300 mg/kg, 50 mg/ml in saline; S3007, Sigma-Aldrich), a dose known to reliably induce tinnitus and hyperacusis-like behavior in rats (Lobarinas et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2011). In the second experiment, sodium salicylate was slowly infused directly into the amygdala (20 µl, 2.8 mM dissolved in saline) through a glass micropipette (tip diameter of ~100 µm). Note that salicylate concentrations of 1.4 mM were observed in the CSF after systemic treatment with 460 mg/kg i.p. of sodium salicylate (Jastreboff et al., 1986). We expect that our salicylate concentrations near the pipette would rapidly decline to 1.4 mM or lower due to diffusion.

Electrodes

Electrophysiological recordings from the LA were obtained using either a custom electrode assembly consisting of 2 to 4 polyimide-insulated tungsten electrodes (FHC Inc., impedance ~1 MΩ) or a 16-channel, linear silicon microelectrode (A-1x16-10mm 100–177, NeuroNexus Technologies). Electrophysiological activity of neurons in the AC was recorded with a 16-channel silicon microelectrode arranged in a 4 x 4 matrix (A-4x4-3mm 100–125–177, NeuroNexus Technologies).

Surgery, stimuli and physiological recordings

Rats were anesthetised with ketamine and xylazine (50 and 6 mg/kg i.m.) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus with ear bars. The dorsal surface of the skull was exposed and a head bar firmly attached to the skull using screws and dental cement. The head bar was attached to a rod mounted on a magnetic base. The head bar assembly was used to hold the rat’s head in the stereotaxic frame after removing the right stereotaxic ear bar. This allowed the right ear to be acoustically stimulated using a free-field loudspeaker. An opening was made in the skull at the appropriate location(s) to gain access to the left, contralateral LA and/or left AC. The dura was removed from the surface of the brain overlying the left amygdala and/or left AC. Electrodes were inserted into the left dorsal surface of the cortex and advanced into the LA using stereotaxic coordinates (AP=2.8-3.8 mm, ML=5.4–5.8 mm, and DV=7.0–8.5 mm from Bregma) (Watson and Paxinos, 2004). The 16-channel (4x4) silicon electrode was advanced into the primary AC (Polley et al., 2007). Placement of the electrode in the primary AC was guided by anatomical landmarks and confirmed on the basis of multiunit (MU) clusters or single units response properties, specifically short latency responses and canonical frequency receptive fields (FRF) (Polley et al., 2007).

Tone or broadband noise bursts (50 ms duration, 1 ms rise/fall time, cosine2-gated) were generated (TDT RX6-2, ~100 kHz sampling rate) and presented at a rate of 2/s. The stimuli were delivered through a loudspeaker (FT28D, Fostex) located 10 cm in front of the right ear (Note: recordings made from left LA and AC contralateral to stimulated ear). Stimuli were calibrated using the electrical signal output from a sound level meter (Larson Davis model, ¼ inch microphone, model 2520). Responses to the noise bursts were obtained at 11 intensity levels (0–100 dB SPL, 10-dB steps, 50 repetitions per intensity, pseudorandom presentation). Responses to tone bursts were collected at 10 frequencies (1.0, 1.5, 2.3, 3.5, 5.3, 8.0, 12.1, 18.3, 27.7, and 42.0 kHz) at 6 intensity levels (0–100 dB SPL, 20-dB steps, 50 repetitions per frequency-intensity combination; pseudorandom presentation order).

Local field potentials (LFP) and spike discharges were sampled simultaneously from the same electrode at 24414.06 Hz using a RA16PA preamplifier and RX5 base station (Tucker-Davis Technologies System-3, Alachua, FL) using custom-written data acquisition and analysis software (MATLAB R2007b, MathWorks) as previously described (Stolzberg et al., 2011). Following digital bandpass filtering (2 – 300 Hz), LFP signals were down-sampled online to 610 Hz. Averaged evoked LFPs were computed from the down-sampled data over a 500 ms time window following stimulus onset. Spike detection was performed online using a manually set voltage threshold (spike signal digitally filtered: 300–3500 Hz). Spikes were time-stamped with a resolution of 40.96 microseconds and used to construct peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) offline using custom software. PSTHs were generated with a time window up to 500 ms; bin widths were typically 1–10 ms. Spike counts from the PSTHs were used to construct FRF of each neuron or MU cluster.

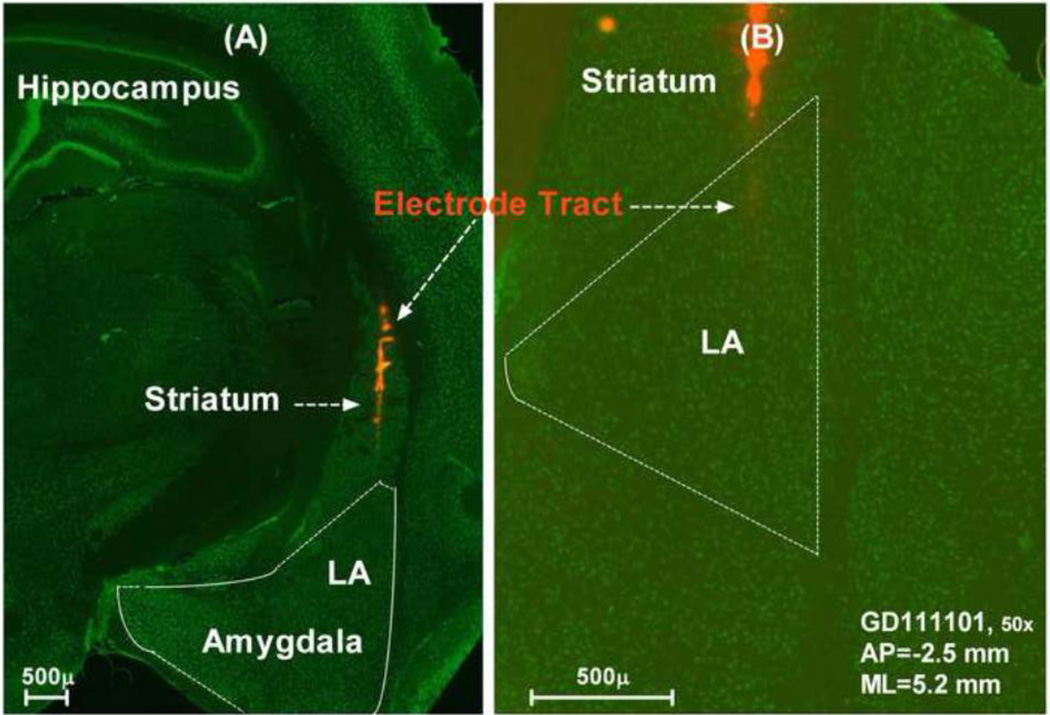

Anatomical confirmation of electrode position

The electrode penetrations into the LA were guided by stereotaxic coordinates (Watson and Paxinos, 2004) and electrophysiological responses to acoustic stimuli (Bordi and LeDoux, 1992; Bordi et al., 1993); electrode position was adjusted to identify acoustically responsive area in the LA. Electrode position in the LA was further verified in some animals by painting a fluorescence dye (DiI, Cat# 42364, Sigma-Aldrich) on the surface of the electrode before penetration. After completing the recording, the brain was removed from the skull, placed in 10% buffered formalin for one week and immersed in sucrose solution (30%) for two days. The brain was cryosectioned (50 µm) in the coronal plane following our published procedures (Kraus et al., 2010; Manohar et al., 2012). After blocking in normal horse serum, slices were incubated in a primary mouse anti-neuronal nuclei (NeuN) monoclonal antibody (1:1000, Chemicon, MAB377), washed three times with phosphate buffered saline and incubated with a donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000; Invitrogen, A21202). Sections were washed with phosphate buffered and mounted onto Fisher Superfrost polarized slides and coverslipped with Prolong Antifade mounting medium (Invitrogen). Sections were visualized and photographed with a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 Microscope equipped with a digital camera and images were processed with Zeiss AxioVision software. Figure 8A presents a typical example of a section showing a penetration of the electrode through the striatum into the LA. Figure 8B is an enlarged image showing the DiI labelling of the electrode track near the tip in the LA.

Figure 8.

(A) Photomicrograph of a coronal section through the left side of the brain showing DiI labeling (red) of the electrode track through the striatum and into the dorsal division of the lateral amygdala (LA). Neurons immunolabeled with a monoclonal antibody against NeuN and fluorescently-conjugated secondary antibody against Alexa Fluor 488 (green). (B) Higher magnification of adjacent section from the same animal as in (A) showing electrode tract in the LA. AP: anterior-posterior refer to the Bregma; ML: middle-lateral refer to the middle line.

Statistical analysis

Repeated measures ANOVAs with Bonferroni post-test (GraphPad ver. 5, Prism) were used to evaluate the significance of the results.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01DC009091; R01DC009219; F31DC010931) and Tinnitus Research Initiative. The authors gratefully acknowledge the extensive technical support of Daniel Stolzberg in developing the software used in this study.

Abbreviations

- AC

auditory cortex

- CF

characteristic frequency

- FRF

frequency receptive field

- LA

Lateral amygdala

- LFP

local field potential

- MGB

medial geniculate body

- PSTH

peristimulus time histogram

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amano T, Unal CT, Pare D. Synaptic correlates of fear extinction in the amygdala. Nature neuroscience. 2010;13:489–494. doi: 10.1038/nn.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow during tinnitus: a PET case study with lidocaine and auditory stimulation. Acta Otolaryngol. 2000;120:967–972. doi: 10.1080/00016480050218717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, et al. Tinnitus distress, anxiety, depression, and hearing problems among cochlear implant patients with tinnitus. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2009;20:315–319. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.20.5.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold W, et al. Focal metabolic activation in the predominant left auditory cortex in patients suffering from tinnitus: a PET study with [18F]deoxyglucose. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1996;58:195–199. doi: 10.1159/000276835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordi F, LeDoux J. Sensory tuning beyond the sensory system: an initial analysis of auditory response properties of neurons in the lateral amygdaloid nucleus and overlying areas of the striatum. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2493–2503. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02493.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordi F, et al. Single-unit activity in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala and overlying areas of the striatum in freely behaving rats: rates, discharge patterns, and responses to acoustic stimuli. Behavioral neuroscience. 1993;107:757–769. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.107.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan JF, Jastreboff PJ. Generalization of conditioned suppression during salicylate-induced phantom auditory perception in rats. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 1991;51:15–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budinger E, et al. Non-sensory cortical and subcortical connections of the primary auditory cortex in Mongolian gerbils: bottom-up and top-down processing of neuronal information via field AI. Brain Res. 2008;1220:2–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.07.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GD, Jastreboff PJ. Salicylate-induced abnormal activity in the inferior colliculus of rats. Hear Res. 1995;82:158–178. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)00174-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GD, et al. Too much of a good thing: long-term treatment with salicylate strengthens outer hair cell function but impairs auditory neural activity. Hear Res. 2010;265:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cima RF, Crombez G, Vlaeyen JW. Catastrophizing and fear of tinnitus predict quality of life in patients with chronic tinnitus. Ear and hearing. 2011;32:634–641. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31821106dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crippa A, et al. A diffusion tensor imaging study on the auditory system and tinnitus. The open neuroimaging journal. 2010;4:16–25. doi: 10.2174/1874440001004010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ridder D, et al. Amygdalohippocampal involvement in tinnitus and auditory memory. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;(Suppl):50–53. doi: 10.1080/03655230600895580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvarci S, Pare D. Glucocorticoids enhance the excitability of principal basolateral amygdala neurons. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27:4482–4491. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0680-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engineer ND, et al. Reversing pathological neural activity using targeted plasticity. Nature. 2011;470:101–104. doi: 10.1038/nature09656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans EF, Wilson JP, Borerwe TA. Animal models of tinnitus. Ciba Found Symp. 1981;85:108–138. doi: 10.1002/9780470720677.ch7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faingold CL, Hoffmann WE, Caspary DM. Comparative effects of convulsant drugs on the sensory responses of neurons in the amygdala and brainstem reticular formation. Neuropharmacology. 1985;24:1221–1230. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(85)90158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhadi M, et al. Functional brain abnormalities localized in 55 chronic tinnitus patients: fusion of SPECT coincidence imaging and MRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:864–870. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraud AL, et al. A selective imaging of tinnitus. Neuroreport. 1999;10:1–5. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199901180-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong N, et al. The aspirin metabolite salicylate enhances neuronal excitation in rat hippocampal CA1 area through reducing GABAergic inhibition. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu JW, et al. Tinnitus, diminished sound-level tolerance, and elevated auditory activity in humans with clinically normal hearing sensitivity. Journal of neurophysiology. 2010;104:3361–3370. doi: 10.1152/jn.00226.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner HE, et al. Audiogram of the hooded Norway rat. Hearing research. 1994;73:244–247. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm MM, et al. Hippocampal GABAergic dysfunction in a rat chronic mild stress model of depression. Hippocampus. 2011;21:422–433. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff PJ, et al. Differential uptake of salicylate in serum, cerebrospinal fluid, and perilymph. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;112:1050–1053. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1986.03780100038004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff PJ. Phantom auditory perception (tinnitus): mechanisms of generation and perception. Neurosci Res. 1990;8:221–254. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(90)90031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff PJ, Jastreboff MM. Tinnitus retraining therapy: a different view on tinnitus. ORL; journal for oto-rhino-laryngology and its related specialties. 2006;68:23–29. doi: 10.1159/000090487. discussion 29-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff PJ. Tinnitus retraining therapy. Progress in brain research. 2007;166:415–423. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)66040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff PJ, Sasaki CT. An animal model of tinnitus: a decade of development. Am. J. Otol. 1994;15:19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA. Summary of evidence pointing to a role of the dorsal cochlear nucleus in the etiology of tinnitus. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;(Suppl):20–26. doi: 10.1080/03655230600895309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl A, et al. Neuroelectric source imaging of steady-state movement-related cortical potentials in human upper extremity amputees with and without phantom limb pain. Pain. 2004;110:90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang NY, Liberman MC, Levine RA. Auditory-nerve activity in cats exposed to ototoxic drugs and high-intensity sounds. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1976;85:752–768. doi: 10.1177/000348947608500605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizawa K, et al. Behavioral assessment and identification of a molecular marker in a salicylate-induced tinnitus in rats. Neuroscience. 2010;165:1323–1332. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus KS, et al. Noise trauma impairs neurogenesis in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2010;167:1216–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langguth B, et al. The impact of auditory cortex activity on characterizing and treating patients with chronic tinnitus--first results from a PET study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;(Suppl):84–88. doi: 10.1080/03655230600895317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux J. The amygdala. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R868–R874. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitin DJ, et al. Neural correlates of auditory perception in Williams syndrome: an fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2003;18:74–82. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobarinas E, et al. A novel behavioral paradigm for assessing tinnitus using schedule-induced polydipsia avoidance conditioning (SIP-AC) Hear Res. 2004;190:109–114. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(04)00019-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood AH, et al. The functional neuroanatomy of tinnitus: evidence for limbic system links and neural plasticity. Neurology. 1998;50:114–120. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, et al. GABAergic neural activity involved in salicylate-induced auditory cortex gain enhancement. Neuroscience. 2011;189:187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma WL, Hidaka H, May BJ. Spontaneous activity in the inferior colliculus of CBA/J mice after manipulations that induce tinnitus. Hear Res. 2006;212:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlke C, Wallhausser-Franke E. Evidence for tinnitus-related plasticity in the auditory and limbic system, demonstrated by arg3.1 and c-fos immunocytochemistry. Hear Res. 2004;195:17–34. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manohar S, et al. Expression of doublecortin, a neuronal migration protein, in unipolar brush cells of the vestibulocerebellum and dorsal cochlear nucleus of the adult rat. Neuroscience. 2012;202:169–183. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Mascagni F. Immunohistochemical localization of the beta 2 and beta 3 subunits of the GABAA receptor in the basolateral amygdala of the rat and monkey. Neuroscience. 1996;75:407–419. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirz F, et al. Positron emission tomography of cortical centers of tinnitus. Hear Res. 1999;134:133–144. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirz F, et al. Cortical networks subserving the perception of tinnitus--a PET study. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2000a;543:241–243. doi: 10.1080/000164800454503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirz F, et al. Functional brain imaging of tinnitus-like perception induced by aversive auditory stimuli. Neuroreport. 2000b;11:633–637. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200002280-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller AR. Pathophysiology of tinnitus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2003;36:249–266. v–vi. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(02)00170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya P, et al. The cortical somatotopic map and phantom phenomena in subjects with congenital limb atrophy and traumatic amputees with phantom limb pain. The European journal of neuroscience. 1998;10:1095–1102. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlnickel W, et al. Reorganization of auditory cortex in tinnitus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10340–10343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulders WH, et al. Relationship between auditory thresholds, central spontaneous activity, and hair cell loss after acoustic trauma. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2011;519:2637–2647. doi: 10.1002/cne.22644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M, et al. Auditory nerve fibre responses to salicylate revisited. Hear Res. 2003;183:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JJ, Chen K. The relationship of tinnitus, hyperacusis, and hearing loss. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2004;83:472–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norena AJ, Eggermont JJ. Enriched acoustic environment after noise trauma reduces hearing loss and prevents cortical map reorganization. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25:699–705. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2226-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony CM, et al. Strain differences in the neurochemical response to chronic restraint stress in the rat: relevance to depression. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2011;97:690–699. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochi K, Eggermont JJ. Effects of salicylate on neural activity in cat primary auditory cortex. Hearing research. 1996;95:63–76. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(96)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver D, et al. Intracellular anions as the voltage sensor of prestin, the outer hair cell motor protein. Science. 2001;292:2340–2343. doi: 10.1126/science.1060939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polley DB, et al. Multiparametric auditory receptive field organization across five cortical fields in the albino rat. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:3621–3638. doi: 10.1152/jn.01298.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popelar J, Syka J, Berndt H. Effect of noise on auditory evoked responses in awake guinea pigs. Hearing research. 1987;26:239–247. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu C, et al. Inner hair cell loss leads to enhanced response amplitudes in auditory cortex of unanesthetized chinchillas: evidence for increased system gain. Hearing research. 2000;139:153–171. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauschecker JP, Leaver AM, Muhlau M. Tuning out the noise: limbic-auditory interactions in tinnitus. Neuron. 2010;66:819–826. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes SA, et al. Brain imaging of the effects of lidocaine on tinnitus. Hear Res. 2002;171:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00346-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznikov LR, Reagan LP, Fadel JR. Effects of acute and repeated restraint stress on GABA efflux in the rat basolateral and central amygdala. Brain research. 2009;1256:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanski LM, et al. Somatosensory and auditory convergence in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107:444–450. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.3.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvi RJ, Hamernik RP, Henderson D. Discharge patterns in the cochlear nucleus of the chinchilla following noise induced asymptotic threshold shift. Experimental brain research. Experimentelle Hirnforschung. Experimentation cerebrale. 1978;32:301–320. doi: 10.1007/BF00238704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvi RJ, et al. Enhanced evoked response amplitudes in the inferior colliculus of the chinchilla following acoustic trauma. Hearing research. 1990;50:245–257. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90049-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvi RJ, Wang J, Ding D. Auditory plasticity and hyperactivity following cochlear damage. Hearing research. 2000;147:261–274. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savastano M, Aita M, Barlani F. Psychological, neural, endocrine, and immune study of stress in tinnitus patients: any correlation between psychometric and biochemical measures? The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2007;116:100–106. doi: 10.1177/000348940711600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlee W, et al. Mapping cortical hubs in tinnitus. BMC Biol. 2009;7:80. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shargorodsky J, Curhan GC, Farwell WR. Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus among US adults. Am J Med. 2010;123:711–718. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman A, et al. SPECT Imaging of Brain and Tinnitus-Neurotologic/Neurologic Implications. Int Tinnitus J. 1995;1:13–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein H, Bernstein JM, Davies DG. Salicylate ototoxicity. A biochemical and electrophysiological study. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1967;76:118–128. doi: 10.1177/000348946707600109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolzberg D, et al. Salicylate-induced peripheral auditory changes and tonotopic reorganization of auditory cortex. Neuroscience. 2011;180:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su YY, et al. Differential effects of sodium salicylate on current-evoked firing of pyramidal neurons and fast-spiking interneurons in slices of rat auditory cortex. Hearing research. 2009;253:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, et al. Noise exposure-induced enhancement of auditory cortex response and changes in gene expression. Neuroscience. 2008;156:374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, et al. Salicylate increases the gain of the central auditory system. Neuroscience. 2009;159:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syka J, Rybalko N, Popelar J. Enhancement of the auditory cortex evoked responses in awake guinea pigs after noise exposure. Hearing research. 1994;78:158–168. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanneste S, et al. The neural correlates of tinnitus-related distress. NeuroImage. 2010;52:470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallhausser-Franke E, et al. Expression of c-fos in auditory and non-auditory brain regions of the gerbil after manipulations that induce tinnitus. Exp Brain Res. 2003;153:649–654. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1614-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallhausser-Franke E, et al. Scopolamine attenuates tinnitus-related plasticity in the auditory cortex. Neuroreport. 2006;17:1487–1491. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000230504.25102.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HT, et al. Sodium salicylate reduces inhibitory postsynaptic currents in neurons of rat auditory cortex. Hear Res. 2006;215:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Caspary D, Salvi RJ. GABA-A antagonist causes dramatic expansion of tuning in primary auditory cortex. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1137–1140. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200004070-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, et al. Gamma-aminobutyric acid circuits shape response properties of auditory cortex neurons. Brain Res. 2002;944:219–231. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02926-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson C, Paxinos G. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 5th. Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wazen JJ, Foyt D, Sisti M. Selective cochlear neurectomy for debilitating tinnitus. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1997;106:568–570. doi: 10.1177/000348949710600707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, et al. Sodium salicylate reduces gamma aminobutyric acid-induced current in rat spinal dorsal horn neurons. Neuroreport. 2005;16:813–816. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200505310-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, et al. Salicylate induced tinnitus: behavioral measures and neural activity in auditory cortex of awake rats. Hear Res. 2007;226:244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Feng MZ, Zhou SC. A study on the effect of stimulation of amygdaloid complex on the electrical response of auditory cortex in rabbits. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 1993;45:75–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, et al. The inhibitory effect of amygdaloid stimulation on the “on-off” response of medial geniculate body neurons in rabbits. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 1999;51:333–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu N, et al. Prestin up-regulation in chronic salicylate (aspirin) administration: an implication of functional dependence of prestin expression. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2008;65:2407–2418. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8195-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zald DH, Pardo JV. The neural correlates of aversive auditory stimulation. Neuroimage. 2002;16:746–753. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SC, Lu XY, Yin HZ. Study of inhibitory effect of amygdaloid stimulation on auditory response of medial geniculate body (MGB) and analysis of transmissive pathway of the said effect. Sci Sin B. 1983;26:262–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]