Abstract

Improving health behaviors is fundamental to preventing and controlling chronic disease. Health care providers who have a patient-centered communication style and appropriate behavioral change tools can empower patients to engage in and sustain healthy behaviors. This review highlights motivational interviewing and mindfulness along with other evidence-based strategies for enhancing patient-centered communication and the behavior change process. Motivational interviewing and mindfulness are especially useful for empowering patients to set self-determined, or autonomous, goals for behavior change. This is important because autonomously motivated behavioral change is more sustainable. Additional strategies such as self-monitoring are discussed as useful for supporting the implementation and maintenance of goals. Thus, there is a need for health care providers to develop such tools to empower sustained behavior change. The additional support of a new role, a health coach who specializes in facilitating the process of health-related behavior change, may be required to substantially influence public health.

Keywords: health behavior, mindfulness, motivational interviewing, health coaching

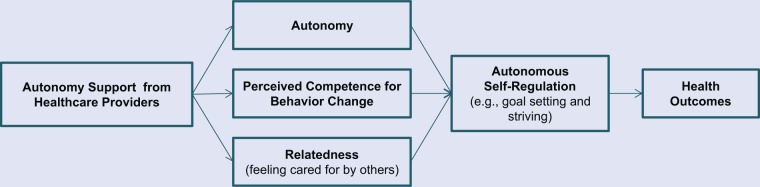

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is a particularly useful self-regulation theory for understanding how the role of a healthcare provider can influence individuals’ behavior change.

Chronic diseases are the leading cause of death in the United States, and improving health behaviors (eg, physical activity, proper nutrition) is fundamental to preventing and controlling chronic disease.1-3 Individuals generally recognize the need for behavior change, but are still unable to change their behavior.4 Thus, it is necessary to empower individuals to take an active role in self-regulating their health behaviors on an ongoing basis to improve health outcomes. Individual empowerment, the concept that “human beings have the right and ability to choose by and for themselves,” is a key concept to promoting healthy behaviors.5 The purpose of this review is to highlight evidence-based methods and resources that health care providers can use to increase patient empowerment and facilitate sustainable behavior change.

Self-Determination Theory

Data support that the quality of health care provider–patient communication promotes patient-empowerment and positive health outcomes.6 Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is a particularly useful self-regulation theory for understanding how the role of a health care provider can influence individuals’ behavior change. SDT emphasizes the importance of individuals’ sense of autonomy regarding their motivation to change a behavior, as opposed to feeling that they should change, in empowering them to engage in and sustain healthy behaviors.5,7 Providers may support this sense of autonomy by encouraging individuals to choose to adopt healthy behaviors that are derived from patients’ personal values. For example, an individual may decide to quit smoking to increase his ability to run a race with his son rather than for a reason that may be important to the provider (eg, reducing the individual’s risk of lung cancer). The opposite of being autonomy supportive is being controlling. Motivation that derives from a health care provider’s advice can still be autonomous if the patient adopts the behavior by his or her own choice, free from cohersion.8

SDT also posits that increased support for autonomy leads to patients’ increased perceived competence, and sense of relatedness (feeling cared for by others), which results in changes in their mental and physical health.9 Supporting autonomy further helps individuals successfully deal with barriers to change, and conveys feelings of acceptance and respect.9,10 Indeed, data support that patients with providers who support autonomy show improved health outcomes (eg, HbA1c values, depressive symptoms).11,12 This relationship between providers’ support of autonomy and sustained improvement in health outcomes is empirically explained in part through increasing patients’ autonomy, perceived competence, and relatedness.9

Autonomy Support

The concept of supporting an individual’s autonomy in SDT is consistent with the concept of providing patient-centered care. Reports published by the Institute of Medicine have identified patient-centered care as a key component of high-quality health care.13,14 The scope of this current review will focus on the influence of health care providers, although patient and health system factors also influence aspects of patient-centered care.15 Specifically, the literature on patient-centered care (also referred to as collaborative care) recommends that health care providers adopt a patient-centered communication style. This style focuses on how the health care provider exchanges information, fosters healing relationships, recognizes and responds to emotions, manages uncertainty, makes decisions, and enables patient self-management.16 In this approach “while professionals are experts about diseases, patients are experts about their own lives.”17(p2470)

Motivational Interviewing

One of the most commonly adopted interventions to enhance health care providers’ patient-centered communication skills is motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing is characterized by an overall spirit that consists of autonomy support, elicitation of patients’ own reasons for change, and collaboration with a focus on increasing patients’ readiness for behavior change.18 Some specific skills used in motivational interviewing include reflective statements (ie, repeating what the patient conveyed), open-ended questions, and eliciting what the patient knows before providing relevant education.

Reflective statements demonstrate active listening and offer the opportunity for a patient to elaborate or clarify what was said. For example, stating back to a patient what you heard them say (eg, “It sounds like you are frustrated that you keep waking up in the morning feeling sick”) may allow him or her to affirm and think more about the topic (eg, “Yes, I would like to stop drinking so much at night so that I can do more activities I enjoy each day”).

Open-ended questions usually start with the words “what” or “how.” An example of an open-ended question commonly used to elicit a patient’s values is, “What is important about that to you?” Tying health behaviors to patients’ values is likely to help them find their own motivation for change.

Understanding what patients know already before providing education allows the provider to target information and increases patients’ receptivity of material. For example, asking a patient “What resources are you aware of that may help you quit smoking?” allows the provider to discover that that the patient is already aware of plenty of resources. This knowledge enables the provider to direct the conversation to be more relevant to the patient and saves time used to discuss topics that are not of interest.

This self-discovery process facilitated by motivational interviewing encourages patients to explore and generate their individual reasons for change.

Motivational interviewing is an approach that was derived experientially and is usually applied to a specific aspect of behavior (eg, alcohol abuse, exercise).19 Motivational interviewing may be either a stand-alone treatment or an addition to other treatments.20,21 Research supporting the efficacy of motivational interviewing is strongest in the areas of addictive and health behaviors.19,22 Motivational interviewing is most useful for patients who are not yet motivated to change.

A limitation of motivational interviewing is that it may not be effective for those who are already prepared to take actions toward behavioral change.19 Furthermore, the effects of motivational interviewing decrease with time since the intervention19 and the optimal duration for the intervention is unknown. The emphasis on increasing the quantity of change talk (ie, number of times the patient mentions the intention to change) in motivational interviewing may also not capture the importance of a patient’s true desire to change.23 That is, patients may express many plans for behavior change consistent with what they expect the provider would like for them to do (eg, “I plan to join a gym so that I will achieve the recommended amount of exercise”) rather than change consistent with their personal values (eg, “I plan to walk daily on the trails near my house because feeling connected with nature is important to me”). Recent interest in the application of SDT to motivational interviewing has encouraged a shift in the emphasis from the quantity of the change talk to ensuring that the quality of the change talk is autonomously motivated.23,24 Therefore, SDT can be adopted to explain the efficacy of motivational interviewing when motivational interviewing emphasizes increasing the same construct important to achieve behavior change proposed in SDT (ie, autonomy support).

Mindfulness

The mindfulness of a health care provider, or tendency to be “attentive to and aware of what is taking place in the present,”25 supports patient autonomy.25-28 Mindfulness in this context is considered a disposition, or general tendency, that can be enhanced by practicing a mindful state through techniques such as meditation.25 Meditation is primarily training your attention to focus on the present moment without judgment. Instructions for a meditation practice could be as simple as the following:

Aim to keep your attention on your breath for the next 5 minutes (set a timer). Notice what moves in your body as you breathe. If your mind wanders, gently remind yourself to bring your attention back to your breathing. Each time you remember to bring your attention back, you are strengthening your ability to be mindful. There is no right or wrong way to do this exercise. Just notice your reactions and know that this meditation practice will likely be different each time you try it.

Indeed, research is emerging to support that a mindful disposition is associated with and mindfulness practices increase the patient-centeredness of health care providers.26,29-31 For example, health care providers (N = 45; physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants) with a higher self-reported mindfulness disposition were more likely to deliver patient-centered care than those with lower mindfulness scores.26 In addition, patients of health care providers who were high in dispositional mindfulness engaged in higher quality patient–physician communication even after adjusting for covariates such as length of visit. Patients of health care providers high in dispositional mindfulness also reported high overall satisfaction with care.

Another study of health care providers (N = 20 physicians) who completed an 8-week course on learning mindfulness practices revealed that they qualitatively perceived an improved ability to be attentive to their patients’ concerns and more effectively respond to such concerns.30 One provider in this study stated,

I am much more attuned to listening. I put a mental stopwatch in my head. I [now] have a heightened awareness and sensitivity to people’s conversation. I look at my own communication and pay much more attention to that. I pay much more attention in general.

Thus illustrating a specific instance of how mindfulness can influence the patient-centeredness of communication. Furthermore, a study of 70 health care providers (ie, primary care physicians) who completed an 8-week course on mindfulness practices reported positive changes in providers’ own health in addition to increases in their empathy and belief that patients’ psychosocial issues are important, which are characteristics related to providing patient-centered care.29 Therefore, the health care providers themselves are likely to benefit from the practice of mindfulness in addition to the positive effect of mindfulness on their patients. Indeed, other studies support the benefits of mindfulness practices for health care providers such as reduced burnout, improved job satisfaction, and improved emotional well-being.29,32-34

The goals of a mindfulness practice include understanding one’s own responses and biases so that it is possible to accurately understand and skillfully relate to the patient.27 When both the physician and patient are engaged, their interaction can lead to a greater outcome than either person could achieve separately.35 The importance of the relationship between the patient and provider is also consistent with the concept of individual’s need for relatedness in SDT.36 Relationships can help individuals process complex information and come to an informed decision.37 People consider multiple components when making decisions, including analytic thinking, feelings, and intuition. If both the patient and provider mindfully experience these multiple components when a medical decision is presented, the discussion of their unique experiences can lead to a more sound decision.37 Understanding patients’ desire for involvement in decision making is considered an important component of patient-centered care.16 It is particularly important to engage patients in the decisions that involve a personal preference such as the decision to change a behavior.38 Therefore, it is likely that increasing the mindfulness of both the patient and health care provider will increase the patient-centeredness of the interaction and likelihood that a patient will decide on an autonomously motivated reason for behavior change.

Facilitating Autonomous Self-Regulation

Self-regulation, or the processes related to achieving a desired outcome,4 can be facilitated by motivational interviewing and mindfulness. Self-regulation consists of 2 overarching processes: goal setting and goal striving.4,39 Patients who are involved in the first process of goal setting may not yet be considering a behavior change. As mentioned previously, motivational interviewing is likely most useful for patients in this stage.19 Mindfulness, or self-awareness, is viewed as the first step in facilitating self-regulation according to the self-regulation theory presented by SDT.28 Mindfulness enhances patients’ ongoing ability to accurately perceive their behavior and how that differs from their desired outcome. In addition, preliminary evidence supports that enhancing mindfulness thorough mind–body practices (eg, meditation, yoga) is related to improvements in lifestyle change (eating disorders, smoking cessation).40,41 For example, noticing the effects of food on the body may influence the desire for an improved diet and result in weight loss (eg, “I notice that I feel sluggish after eating fried food and would like to eat it less so that I am more able to concentrate on my work”).40 Highlighting discrepancies between current and desired states is also used as a technique in motivational interviewing to generate autonomous motivation for and the intention to change.19 Patients who are aware of such discrepancies are more likely to generate intrinsic goals, or goals that are motivated by a self-determined (autonomous) rather than an externally determined reason.7 Intrinsically motivated goals are more likely to be achieved than goals that are extrinsically motivated.4 This point is also illustrated by an intervention to facilitate the self-management of chronic diseases (ie, heart disease, lung disease, stroke, or arthritis) that provided participants with the opportunity to self-select their goals rather than prescribing specific behavior changes.42 Results showed that this process of autonomous goal setting successfully changed health behaviors and reduced hospitalizations.42

Goal Setting

Once patients have determined their motivation to act, health care providers may choose to shift the focus of the conversation to goal setting. Some guidance for goal setting includes having patients4:

Develop goals that are framed toward obtaining a desired rather than an undesired outcome because this makes it more feasible to assess success. For example, it is more tangible to determine if one has attained the goal of walking more frequently than a goal of being less sedentary. One exception is if there is an existing undesired outcome that one would like to eliminate such as a cough from smoking.

Set a goal that is balanced between being ideal and at a realistic level of difficulty. That is, ideal goals such as winning a gold medal in the Olympics may be quite motivating and serve as a useful overarching vision; however, starting with a more short-term goal of beating your personal best performance in the chosen sport may be a more realistic first step. Choosing a goal with the appropriate level of difficulty will increase expectations for a positive outcome and beliefs that one is capable of achieving the goal.

Create a goal that is focused on gradually mastering the process of developing a new behavior rather than an “all-or-nothing” strategy for immediately achieving the ultimate outcome.

Goal setting is an effective strategy that leads to behavior change as at least partially explained through increasing perceived competence (also called self-efficacy).43,44 Perceived competence is important at different stages of behavior change (ie, goal setting and goal striving).39

Goal Striving

Once patients have set a goal to initiate a behavior change, the next step is to engage in goal pursuit. This process involves performing and sustaining the intended action.39 In this process, it is important to cultivate a patient’s perceived competence for performing the behaviors needed to achieve a goal (eg, knowledge of when, where, how behaviors will be performed) and perceived competence for maintaining the goal once the new behavior is initiated (eg, confidence in identifying barriers and planning alternative actions). Some recommended strategies for supporting successful goal pursuit include having patients4:

Specify what actions will be taken and when to achieve the goal.

Prevent disruptions to goal achievement using various strategies such as (a) identify possible obstacles and plan ways to alter consequences of taking undesired actions, (b) create automatic habits by consistently engaging in the desired behavior in a particular context, and (c) find ways to remember to think of big picture related to the overall goal rather than the specific situation that may contain an obstacle.

A successful action process also includes self-monitoring (eg, identifying methods for developing accountability to achieving goal), which is another strategy supported by evidence for inclusion in behavior change interventions.45-47 The process of goal striving will be supported by regular interactions with a health care provider who is knowledgeable of the patient’s goals.48

Figure 1 illustrates evidence-based relationships among the SDT concepts discussed.7,9,10

Figure 1.

A Self-Regulation Model for Enhancing Patients’ Sustained Behavior Change.

Health Coaching

Health coaching is a new profession that draws from multiple evidence-based tools for facilitating patients’ autonomous self-regulation (eg, motivational interviewing, mindfulness, self-monitoring) to address the growing need for an increase in healthy behaviors. Health coaches generally support individuals in identifying health behavior change goals and maintaining desired changes over a series of coaching sessions. Health coaches have emerged from 2 general perspectives: (a) within a health care context with the goal of managing chronic medical conditions and (b) from a life coaching background with the goal of supporting optimal health. A National Consortium for Credentialing Health and Wellness Coaches (http://ncchwc.org/) has convened and is in the process of creating a formal uniform definition. Although there is considerable variability in the current definition of a health coach, a recent systematic review has identified similarities within these diverse existing interventions such that most include the following common components: a patient-centered approach, encouragement of self-discovery, content education, goal setting determined by the patient, and mechanisms such as self-monitoring for developing accountability.49 Thus, health coaching is an approach that emphasizes supporting the autonomy of the patient in facilitating behavior change and is consistent with the principles of behavior changed outlined by SDT.23,50

Reviews of the existing literature on the overall efficacy of health coaching are promising yet inconclusive due to the previous variability in the definition of health coaching and limited number of high-quality studies.49,51-54 In general, these reviews provide preliminary support for the capacity of health coaching to improve behavior change and mental and physical health outcomes. Published interventions that utilize the term “health coach” in the context of health also differ with regard to variables such as the educational background, level of training as a health coach,49 level of experience, and additional skills that may be incorporated (eg, mindfulness practices).55 The background of health coaches varies with a majority who hold additional professional degrees (eg, 51% allied health professionals and 42% nurses).49 Therefore, future research with stronger methodological designs that adopt the newly established definition of a health coach and include reporting of treatment fidelity processes are needed.49,53

Health Coaching and Motivational Interviewing

The encouragement of self-discovery in health coaching is similar to the focus of evoking a patient’s self-determined reason for behavior change used in motivational interviewing. Thus, a health coach may adopt motivational interviewing as one of multiple tools utilized.56 This approach engages patients in problem solving rather than the health care provider didactically prescribing behavioral change. Health coaches enable patients to develop individualized action plans by eliciting what content education is needed, facilitating autonomous goal setting, and mechanisms for developing accountability. Although many coaching techniques are drawn from a subset of the psychological literature, diagnosing or working with psychopathology is not within the scope of a health coach’s role.57

Recent individual studies with strong methodology demonstrate the efficacy of coaching to improve some specific health behaviors and outcomes. For example, a randomized controlled trial (N = 415) found that coaching implemented both in person and remotely as compared to a self-directed control group resulted in sustained weight loss at 24 months for obese patients who had at least one cardiovascular risk factor.58 Another randomized controlled trial (N = 410) found that a telephone-based coaching intervention as compared to usual care improved moderate physical activity, body mass index, and dietary habits after 12 months in colorectal cancer survivors.59 Both of these health coaching interventions used motivational interviewing plus additional behavior change techniques (eg, self-monitoring, mindfulness) and found a significant effect of multiple coaching contacts (ie, >10 sessions) implemented remotely.58,59

Health Coaching and Mindfulness

Mindfulness is likely to strengthen both the health care provider’s support of the patient’s autonomy and the patient’s ability to autonomously engage in the self-regulation process. That is, mindfulness may augment the patient-centeredness of the interaction between patient and provider and subsequently optimize the likelihood of a patient’s successful behavioral change. The International Coach Federation identifies coaching presence as a core competency of coaching in general (not specific to “health” coaching). A component of coaching presence, that a coach “is present and flexible during the coaching process, dancing in the moment,” is consistent with being mindful (http://www.coachfederation.org/). Thus, coaching as a field recognizes that mindfulness is essential to a coaching relationship; however, not all training programs specifically include mindfulness practices as tools to enhance this competency. An existing health coaching intervention that has adopted mindfulness (ie, self-awareness) as a central component found improved self-efficacy, accountability, and clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes.60 Yet, the specific impact of mindfulness on the efficacy of health coaching has not been investigated. An exciting direction for future research and clinical practice will be the evaluation of enhancing mindfulness among health coaches to improve efficacy.

Future Directions

Given the impact of poor health behaviors, strategies to promote and sustain behavioral change are a fundamental public health concern. Presently, there are a lack of programs and resources in health care to support behavioral change as we have outlined. Possible cost savings resulting from successful behavior change and thus possible reduced health care utilization61 may generate the resources needed to support behavior change interventions.

Health care providers interested in strengthening their mindfulness and behavioral change skills may choose to pursue training in these tools separately or in combination. For example, mindfulness may be learned through Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction courses that are offered at many locations (http://w3.umassmed.edu/MBSR/public/searchmember.aspx) and motivational interviewing may be learned through trainings offered by the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (http://www.motivationalinter viewing.org/). Health coaching programs are offered remotely or in person at various independent locations and universities with some programs that specifically incorporate mindfulness training components (eg http://www.instituteofcoaching.org/images/ARticles/Heath%20and%20Wellness%20CoachTrainingPrograms-July-2011.pdf).

The optimal role of a health coach in health care has yet to be determined. One proposed model is that medical practices could optimize their patients’ health outcomes by hiring a health coach as a new professional who specifically focuses on the behavior change process.62 Future documentation of clinical outcomes and research reporting on the efficacy of health coaching will be necessary to clarify this new role. Health coaches have the potential to improve the burden of chronic disease on patients and ultimately the overall population.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Office of Research on Women’s Health, Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) Scholar Program (2K12HD043483-11) and the NIH, National Center for Complementary & Alternative Medicine Grant K23 AT006965-01A1. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic disease—overview. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm#2. Accessed April 3, 2013.

- 2. Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mann T, de Ridder D, Fujita K. Self-regulation of health behavior: social psychological approaches to goal setting and goal striving. Health Psychol. 2013;32:487-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aujoulat I, d’Hoore W, Deccache A. Patient empowerment in theory and practice: polysemy or cacophony? Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66:13-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152:1423-1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory: a macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can Psychol. 2008;49:182-185. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Markland D, Ryan RM, Tobin VJ, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2005;24:811-831. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ng JYY, Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, et al. Self-determination theory applied to health contexts a meta-analysis. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012;7:325-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Williams GC, Minicucci DS, Kouides RW, et al. Self-determination, smoking, diet and health. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:512-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Williams GC, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1644-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williams GC, McGregor HA, King D, Nelson CC, Glasgow RE. Variation in perceived competence, glycemic control, and patient satisfaction: relationship to autonomy support from physicians. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:39-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10027&page=4. Accessed September 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Committee on Improving the Quality of Cancer Care, Institute of Medicine. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=18359&page=3. Accessed September 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in patient-physician consultations: theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1516-1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McCormack LA, Treiman K, Rupert D, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in cancer care: a literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1085-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288:2469-2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hartzler B, Beadnell B, Rosengren DB, Dunn C, Baer JS. Deconstructing proficiency in motivational interviewing: mechanics of skilful practitioner delivery during brief simulated encounters. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2010;38:611-628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64:527-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:843-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lundahl B, Moleni T, Burke BL, et al. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory in health care and its relations to motivational interviewing: a few comments. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Meeting in the middle: motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:822-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beach MC, Roter D, Korthuis PT, et al. A multicenter study of physician mindfulness and health care quality. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:421-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999;282:833-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD. Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychol Inq. 2007;18:211-237. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302:1284-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beckman HB, Wendland M, Mooney C, et al. The impact of a program in mindful communication on primary care physicians. Acad Med. 2012;87:815-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. West C, Dyrbye L, Rabatin J, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:527-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fortney L, Luchterhand C, Zakletskaia L, Zgierska A, Rakel D. Abbreviated mindfulness intervention for job satisfaction, quality of life, and compassion in primary care clinicians: a pilot study. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:412-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goodman MJ, Schorling JB. A mindfulness course decreases burnout and improves well-being among healthcare providers. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;43:119-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cohen-Katz J, Wiley SD, Capuano T, Baker DM, Kimmel S, Shapiro S. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on nurse stress and burnout, part II: a quantitative and qualitative study. Holist Nurs Pract. 2005;19:26-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Suchman AL. A new theoretical foundation for relationship-centered care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S40-S44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ryan RM, Patrick H, Deci EL, Williams GC. Facilitating health behaviour change and its maintenance: interventions based on self-determination theory. Eur Health Psychol. 2008;10:2-5. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Epstein RM. Whole mind and shared mind in clinical decision-making. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90:200-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Politi MC, Wolin KY, Légaré F. Implementing clinical practice guidelines about health promotion and disease prevention through shared decision making. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:838-844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schwarzer R, Lippke S, Luszczynska A. Mechanisms of health behavior change in persons with chronic illness or disability: the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA). Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56:161-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Godsey J. The role of mindfulness based interventions in the treatment of obesity and eating disorders: an integrative review. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21:430-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Carim-Todd L, Mitchell SH, Oken BS. Mind-body practices: an alternative, drug-free treatment for smoking cessation? A systematic review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:399-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care. 1999;37:5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lorig KR. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Strecher VJ, Seijts GH, Kok GJ, et al. Goal setting as a strategy for health behavior change. Health Educ Q. 1995;22:190-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bird EL, Baker G, Mutrie N, Ogilvie D, Sahlqvist S, Powell J. Behavior change techniques used to promote walking and cycling: a systematic review. Health Psychol. 2013;32:829-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kelly NR, Mazzeo SE, Bean MK. Systematic review of dietary interventions with college students: directions for future research and practice. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45:304-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bodenheimer T. Helping patients improve their health-related behaviors: what system changes do we need? Dis Manag. 2005;8:319-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wolever RQ, Simmons LA, Sforzo GA, et al. A systematic review of the literature on health and wellness coaching: defining a key behavioral intervention in healthcare. Glob Adv Health Med. 2013;2:34-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wolever RQ, Eisenberg DM. What is health coaching anyway? Standards needed to enable rigorous research: comment on “Evaluation of a behavior support intervention for patients with poorly controlled diabetes.” Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:2017-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Newnham-Kanas C, Gorczynski P, Morrow D, Irwin J. Annotated bibliography of life coaching and health research. Int J Evid Based Coach Mentor. 2009:39-103. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Olsen JM, Nesbitt BJ. Health coaching to improve healthy lifestyle behaviors: an integrative review. Am J Health Promot. 2010;25:e1-e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hutchison AJ, Breckon JD. A review of telephone coaching services for people with long-term conditions. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17:451-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Frates EP, Moore MA, Lopez CN, McMahon GT. Coaching for behavior change in psychiatry. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90:1074-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wolever RQ, Caldwell KL, Wakefield JP, et al. Integrative health coaching: an organizational case study. Explore. 2011;7:30-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Simmons LA, Wolever RQ. Integrative health coaching and motivational interviewing: synergistic approaches to behavior change in healthcare. Glob Adv Health Med. 2013;2:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jordan M, Livingstone JB., Coaching vs. psychotherapy in health and wellness: overlap, dissimilarities, and the potential for collaboration. Glob Adv Health Med. 2013;2:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Appel LJ, Clark JM, Yeh HC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1959-1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hawkes AL, Chambers SK, Pakenham KI, et al. Effects of a telephone-delivered multiple health behavior change intervention (CanChange) on health and behavioral outcomes in survivors of colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2313-2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wolever RQ, Dreusicke M, Fikkan J, et al. Integrative health coaching for patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:629-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wennberg DE, Marr A, Lang L, O’Malley S, Bennett G. A randomized trial of a telephone care-management strategy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1245-1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bodenheimer T, Laing BY. The teamlet model of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:457-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]