Abstract

Among patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), the impact of residual pretransplant cytogenetically abnormal cells on outcomes remains uncertain. We analyzed HCT outcomes by time of transplant disease variables, including (1) blast percentage, (2) percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells and (3) Revised International Prognostic Scoring System (R-IPSS) cytogenetic classification. We included 82 MDS patients (median age 51 years (range 18–71)) transplanted between 1995 and 2013 with abnormal diagnostic cytogenetics. Patients with higher percentages of cytogenetically abnormal cells experienced inferior 5-year survival (37–76% abnormal cells: relative risk (RR) 2.9; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.2–7.2; P = 0.02; and 77–100% abnormal cells: RR 5.6; 95% CI 1.9–19.6; P < 0.01). Patients with > 10% blasts also had inferior 5-year survival (RR 2.9; 95% CI 1.1–7.2; P = 0.02) versus patients with ≤2% blasts. Even among patients with ≤2% blasts, patients with 77–100% cytogenetically abnormal cells had poor survival (RR 4.4; 95% CI 1.1–18.3; P = 0.04). Increased non-relapse mortality (NRM) was observed with both increasing blast percentages (P < 0.01) and cytogenetically abnormal cells at transplant (P = 0.01) in multivariate analysis. We observed no impact of disease burden characteristics on relapse outcomes due to high 1-year NRM. In conclusion, both blast percentage and percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells reflect MDS disease burden and predict post-HCT outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a heterogeneous group of hematologic malignancies characterized by bone marrow dysplasia, ineffective hematopoiesis, cytopenias and a risk of progression to acute myelogenous leukemia.1 Because the prognosis may vary considerably among patients, several scoring systems have been developed to individualize predictions of overall survival (OS) and risk of leukemic progression.2,3 Each scoring system utilizes stratifications of bone marrow blast percentage, cytogenetic risk and cytopenias to predict clinical outcomes. Based on these models, higher-risk patients are recommended for earlier hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), the only potentially curative treatment for MDS.4,5

Recently, research efforts have focused on the impacts of pre-HCT therapy and pre-HCT disease variables on HCT outcomes.6,7 In both settings, residual disease burden was defined by the percentage of bone marrow blasts. However, blast percentage alone may not precisely quantify the extent of disease burden in MDS. Incorporating the percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells into the pretransplant assessment may yield a more accurate measure of disease burden that may improve pre-HCT prognostic information as well as provide another measure of response to therapy.8 From a practical standpoint, transplant clinicians are commonly faced with the question of when to transplant patients with MDS, what disease characteristics define the ‘best’ pre-HCT disease burden and what pre-HCT therapy, if any, should be used to limit remaining disease burden and potentially improve post-HCT outcomes.

To investigate these uncertainties, we retrospectively analyzed HCT outcomes among MDS patients with abnormal diagnostic cytogenetics by their pre-HCT disease burden and cytogenetic risk. Disease burden was defined using percentage of bone marrow blasts and percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells by karyotype analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients, study end points and definitions

Through the University of Minnesota Blood Marrow Transplant database, we identified 82 consecutive adult patients (≥18 years of age) with MDS who had an abnormal karyotype at diagnosis and who underwent a first allogeneic HCT between 1995 and 2013. Patients with normal cytogenetics were excluded from analysis. Patients with disease progression to AML were also excluded.

The primary end point was to estimate the utility of pre-HCT disease burden assessment, measured by percentages of bone marrow blasts and cytogenetically abnormal cells, and Revised International Prognostic Scoring System (R-IPSS) cytogenetic stratification to predict post-HCT survival. Secondary end points included non-relapse mortality (NRM), disease relapse and disease-free survival (DFS). Disease relapse was defined as any recurrence of hematologic, morphologic or cytogenetic markers consistent with disease before transplant.

Disease-related variables

Diagnostic specimens were reviewed by institutional hemato-pathologists and classified by the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) MDS criteria.9 Therapy-related MDS (t-MDS) was defined clinically as MDS following exposure to alkylating agents, topoisomerase II inhibitors or radiotherapy. Blast percentage categories (≤2%, > 2– < 5, 5–10 and > 10) were chosen to distinguish patients with deeper levels of remission (≤2%, > 2– < 5) from those with a greater burden of persistent disease (5–10%, > 10). Standard G-banding techniques were used for cytogenetic analysis; consequently, the percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells reflected the ratio of abnormal cells to total cells analyzed (with ≥ 20 cells analyzed). Categories of disease burden by percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells (0, 1–36, 37–76 and 77–100) were developed using recursive partitioning to distinguish patients who achieved normal cytogenetics with pre-HCT therapy and to develop gradations of residual disease burden. Two authors (BJT and MD) independently scored all available cytogenetic analyses by R-IPSS cytogenetic stratification with discrepancies resolved by consensus review.3

Conditioning regimens

Conditioning regimens for myeloablative/reduced intensity conditioning related donor, unrelated donor and umbilical cord blood donor sources were previously reported.10–12 Equine anti-thymocyte globulin (15 mg/kg twice daily × 3 days) was provided to patients who had not received multiagent chemotherapy within 3 months of HCT for unrelated donor/umbilical cord blood or 6 months for matched-related donor. Treatment regimens were reviewed and approved by the University of Minnesota institutional review board and all participating subjects provided informed consent before proceeding to transplant.

Supportive care

All patients received supportive care including blood product support, infection prophylaxis (bacterial, fungal, CMV/herpes simplex virus and Pneumocystis jiroveci) and GvHD prophylaxis. For GvHD prophylaxis, the majority of patients received cyclosporine-based regimens (targeting trough levels > 200 ng/mL) through day +180 with either pulsed methotrexate in myeloablative regimens or mycophenolate mofetil through day +30 with reduced intensity conditioning regimens. Filgrastim was administered to all patients through absolute neutrophil count recovery.

Data analysis

Patient outcomes following HCT were prospectively recorded in the University of Minnesota Blood Marrow Transplant database. Factors considered in statistical analysis included the following: patient age, gender, Karnofsky performance status, HCT-Comorbidity Index, recipient CMV serostatus, year of transplant, donor graft source, conditioning regimen intensity, GvHD prophylactic regimen, MDS WHO diagnosis, t-MDS, R-IPSS cytogenetic category at transplant, blast percentage and percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells at transplant.

Statistical methods

Unadjusted univariate estimates of OS and DFS were calculated by Kaplan–Meier curves.13 Comparisons were completed with the log-rank test. NRM and relapse were estimated using cumulative incidence treating relapse as a competing risk for NRM and non-event deaths as competing risks for relapse.14 Gray’s test completed comparisons among cumulative incidence curves.15 To assess whether a trend existed within an index, Tarone’s test for trend was employed.16 Cox regression was used to assess the independent effect of indices on OS and DFS; Fine and Gray proportional hazards regression was used to assess the independent effect of indices on NRM and relapse.17,18 Stepwise elimination was used to achieve a final model. Martingale residuals were used to test against nonproportionality.19 G-band karyotypes (normal versus 1–36% versus 37–76% versus 77–100%), blasts at transplant (≤2% versus 2–4% versus 5–10% versus > 10%) and R-IPSS cytogenetic categories (good/very good versus intermediate versus poor versus very poor) were included in all models. Recursive partitioning was employed to determine the cut-points for G-banding karyotypes.20 Because of significant correlations among blast percentage, percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells and R-IPSS cytogenetic risk-groups, the Akaike information criterion was used to measure the level of model fitting for each HCT outcome with a lower number identifying the ‘best fit’.21 All reported P-values were two sided. SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R 3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Australia) were used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Patient demographics

Patient, disease and transplant characteristics for the 82 patients (median age 51 years, range 18–71) are shown in Table 1. HCT-Comorbidity Index risk groups were evenly represented: low risk (28%), intermediate risk (37%) and high risk (35%). A majority of patients were diagnosed with either refractory anemia with excess blasts (40%) or refractory cytopenias with multilineage dysplasia/ringed sideroblasts (32%). Twenty patients (24%) had t-MDS. A total of 41 patients (50%) received some type of pre-HCT therapy and included traditional induction chemotherapy in 18 patients and hypomethylating agents in 20 patients. The highest use of induction chemotherapy was in the cohort that achieved a complete cytogenetic remission (0% cytogenetically abnormal cells) and the group with 37–76% cytogenetically abnormal cells at transplant. Treatment details across these individual cohorts are found in the Supplementary Tables 1A and 1B.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 82 (100%) |

| Age < 50 | 35 (43%) |

| Male | 58 (71%) |

| KPS ≥ 90 | 65 (79%) |

| HCT-CI score | |

| Low risk (0) | 23 (28%) |

| Intermediate (1–2) | 30 (37%) |

| High (≥ 3) | 29 (35%) |

| WHO MDS Classification | |

| MDS–Unknown | 16 (20%) |

| MDS–RA/RARS | 7 (9%) |

| MDS–RAEB | 33 (40%) |

| MDS–RCMD/RS | 26 (32%) |

| Therapy–MDS | 20 (24%) |

| % of cytogenetically abnormal cells at HCT | |

| 0 | 13 (16%) |

| 1–36 | 17 (21%) |

| 37–76 | 41 (50%) |

| 77–100 | 11 (13%) |

| Blasts at HCT | |

| ≤ 2% | 43 (52%) |

| > 2 to < 5% | 21 (26%) |

| 5–10% | 12 (15%) |

| > 10% | 6 (7%) |

| R-IPSS cytogenetic category at HCT | |

| Very good/good | 19 (23%) |

| Intermediate | 21 (26%) |

| Poor | 19 (23%) |

| Very poor | 23 (28%) |

| Year of HCT | |

| 1995–2005 | 36 (44%) |

| 2006–2013 | 46 (56%) |

| Donor type | |

| RD | 42 (51%) |

| URD | 12 (15%) |

| UCB | 28 (34%) |

| Conditioning | |

| MA | 36 (44%) |

| RIC w/or w/o ATG | 46 (56%) |

| GvHD prophylaxis | |

| CSA/MMF | 48 (59%) |

| CSA/other | 34 (41%) |

Abbreviations: ATG = anti-thymocyte globulin; CSA = cyclosporine; HCT-CI = hematopoietic cell transplant-Comorbidity Index; KPS = Karnofsky Performance Status; MA = myeloablative; MDS = myelodysplastic syndrome; MMF = mycophenolate mofetil; RA = refractory anemia; RAEB = refractory anemia with excess blasts; RARS = refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts; RCMD = refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia; RD = related donor; RIC = reduced intensity conditioning; R-IPSS = Revised International Prognostic Scoring System; RS = ringed sideroblasts; UCB = umbilical cord blood; URD = unrelated donor; WHO = World Health Organization; w/or w/o = with or without.

Fifty-two percent of patients had ≤ 2% blasts at transplant. R-IPSS cytogenetic categories were evenly represented: very good/good (23%), intermediate (26%), poor (23%) and very poor (28%). Thirteen patients (16%) with previously abnormal cytogenetics achieved normal cytogenetics following pre-HCT therapy. The majority had residual cytogenetic abnormalities by G-banding at HCT: 1–36% abnormal (21%); 37–76% abnormal (50%); 77–100% abnormal (13%). Median follow-up among surviving patients was 5 years (range 1–17 years).

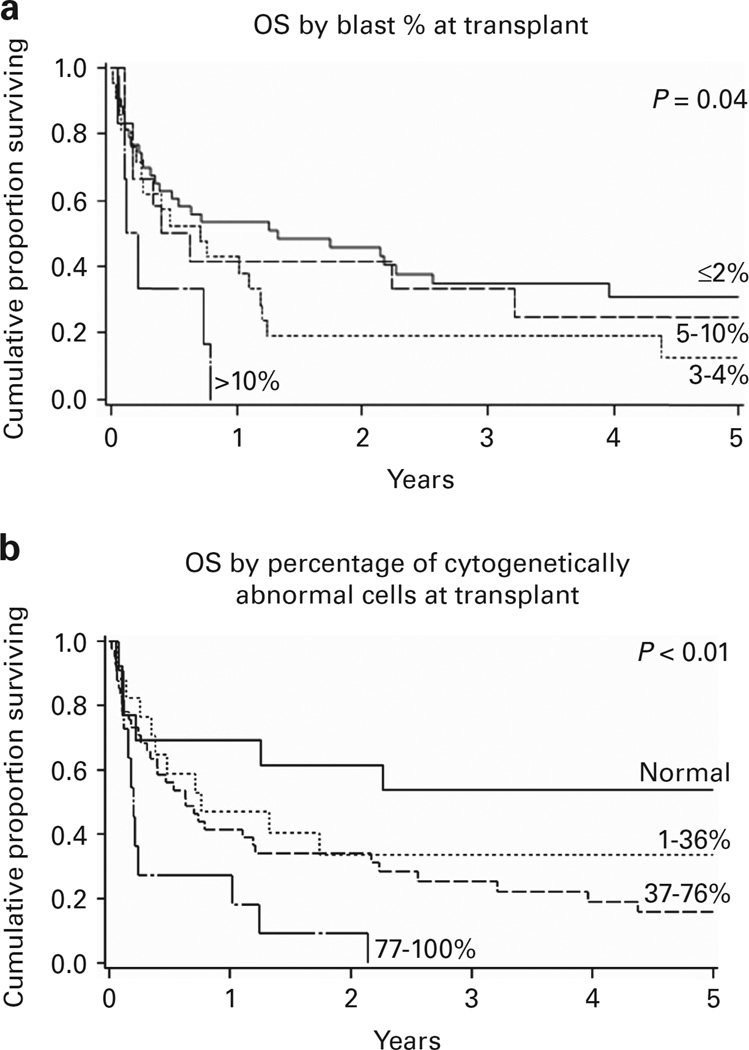

OS DFS

The 1 and 5-year OS among the entire cohort was 45% (95% confidence interval (CI) 34–55%) and 23%(95% CI 14–33%), respectively (Table 2). The 5-year OS was worse in patients with more cytogenetically abnormal cells and blasts at transplant as well as those with lower Karnofsky performance status. Survival at 5 years among patients who achieved normal cytogenetics (0% abnormal cells) was 54% (95% CI 25–76%). Inferior 5-year OS was seen in those with higher percentages of cytogenetically abnormal cells: 1–36% abnormal (OS 34%; 95% CI 13–56%); 37–76% abnormal (OS 16%; 95% CI 6–30%); and 77–100% abnormal (OS 0%; P < 0.01; Figure 1). Patients with low blast percentages (≤2%) had superior 5-year OS (31%; 95% CI 17–46%) compared with patients with > 10% blasts (0%, P = 0.04); survival among the remaining blast percentage categories (> 2 to < 5%, 5–10%) was similar. Neither patient age, HCT-Comorbidity Index risk group, MDS WHO classification, t-MDS, R-IPSS cytogenetic risk category at transplant, donor type, year of transplant, nor conditioning intensity influenced 5-year OS.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of HCT -outcomes by MDS disease variables

| Patient, disease and HCT variables | N | 5-Year OS (95% CI) | P-value | 1-Year NRM (95% CI) | P-value | 1-year relapse (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 82 | 23% (14–33%) | 39% (28–50%) | 27% (1737%) | |||

| Age | 0.95 | 0.12 | 0.49 | ||||

| < 50 | 35 | 28% (15–44%) | 49% (31–66%) | 20% (7–33%) | |||

| ≥ 50 | 47 | 18% (8–32%) | 32% (18–46%) | 32% (18–46%) | |||

| KPS | < 0.01 | 0.2 | 0.49 | ||||

| < 90 | 17 | 0% | 53% (28–78%) | 29% (8–51%) | |||

| 90–100 | 65 | 29% (18–41%) | 35% (23–47%) | 26% (15–37%) | |||

| HCT-CI risk | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.15 | ||||

| Standard (0) | 23 | 33% (15–53%) | 30% (12–49%) | 17% (2–33%) | |||

| Intermediate (1–2) | 30 | 21% (8–37%) | 47% (28–66%) | 23% (8–39%) | |||

| High (3+) | 29 | 16% (5–33%) | 38% (19–56%) | 38% (20–56%) | |||

| % Cytogenetically abnormal cells | < 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.92 | ||||

| 0 | 13 | 54% (25–76%) | 15% (0–34%) | 38% (12–65%) | |||

| 1–36 | 17 | 34% (13–56%) | 29% (8–51%) | 29% (8–51%) | |||

| 37–76 | 41 | 16% (6–30%) | 44% (28–60%) | 24% (11–38%) | |||

| 77–100 | 11 | 0% | 64% (33–95%) | 18% (0–38%) | |||

| % Blasts | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.59 | ||||

| ≤ 2 | 43 | 31% (17–46%) | 26% (12–39%) | 33% (18–47%) | |||

| > 2 to < 5 | 21 | 13% (3–31%) | 52% (30–75%) | 14% (0–29%) | |||

| 5–10 | 12 | 25% (6–50%) | 42% (14–69%) | 33% (7–59%) | |||

| > 10 | 6 | 0% | 83% (50–100%) | 17% (0–36%) | |||

| R-IPSS cytogenetic category | 0.33 | 0.81 | 0.16 | ||||

| Very good/good | 19 | 37% (17–57%) | 26% (7–46%) | 42% (19–65%) | |||

| Intermediate | 21 | 13% (3–31%) | 48% (26–70%) | 29% (9–48%) | |||

| Poor | 19 | 30% (12–51%) | 47% (24–71%) | 11% (0–24%) | |||

| Very poor | 23 | 9% (1–32%) | 35% (15–55%) | 26% (8–44%) | |||

| Therapy-related MDS | 0.68 | 0.19 | 0.64 | ||||

| No | 62 | 22% (12–33%) | 37% (25–50%) | 27% (16–39%) | |||

| Yes | 20 | 26% (8–49%) | 45% (17–74%) | 25% (7–43%) | |||

| Donor type | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.81 | ||||

| RD | 42 | 16% (6–29%) | 45% (29–61%) | 24% (10–37%) | |||

| URD | 12 | 42% (15–67%) | 33% (8–59%) | 33% (8–59%) | |||

| UCB | 28 | 27% (12–44%) | 32% (15–50%) | 29% (12–46%) | |||

| Conditioning intensity | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.15 | ||||

| MA | 36 | 24% (12–39%) | 44% (28–61%) | 17% (4–29%) | |||

| RIC w/ ATG | 30 | 27% (12–45%) | 33% (16–51%) | 33% (16–51%) | |||

| RIC w/out ATG | 16 | 16% (3–38%) | 38% (13–62%) | 38% (14–61%) | |||

| Year of transplant | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.66 | ||||

| 1995–2005 | 36 | 19% (9–34%) | 47% (30–64%) | 22% (8–36%) | |||

| 2006–2013 | 46 | 28% (15–42%) | 33% (19–47%) | 30% (17–44%) | |||

| Pre-HCT therapy | 0.71 | 0.37 | 0.35 | ||||

| No | 41 | 24% (12–39%) | 46% (30–63%) | 22% (9–35%) | |||

| Yes | 41 | 23% (12–37%) | 32% (17–46%) | 32% (17–46%) |

Abbreviations: ATG = anti-thymocyte globulin; HCT-CI = hematopoietic cell transplant-Comorbidity Index; KPS = Karnofsky Performance Status; MA = myeloablative; MDS = myelodysplastic syndrome; OS = overall survival; RD = related donor; RIC = reduced intensity conditioning; R-IPSS = Revised International Prognostic Scoring System; UCB = umbilical cord blood; URD = unrelated donor; w/ = with; w/o = without.

Statistically significant values are indicated in bold.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier OS curves by time-of-transplant disease burden. (a) Blast percentage. (b) Cytogenetically abnormal cell percentage.

The most common causes of death included disease relapse (n = 19), infection (n = 12) acute GvHD (aGvHD; n = 10) and organ failure or acute respiratory distress syndrome (n = 9). Relapse as a cause of death was similar across % blast and % cytogenetically abnormal cell cohorts. Death due to aGvHD was more prominent in those with 37–76% and 77–100% cytogenetically abnormal cells, accounting for 9 of the 10 aGvHD-related deaths. Infectious deaths were also more common in those with 37–76% and 77–100% cytogenetically abnormal cells, accounting for 9 of the 12 infection-related deaths.

In multiple regression analysis, 5-year OS modeling showed better outcome prediction using the percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells (Akaike information criterion 463.2) compared with the blast percentage (469.0) or R-IPSS cytogenetic stratification (471.1; Table 3). Patients with a higher percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells experienced inferior survival (37–76% (relative risk (RR) 2.9; 95% CI 1.2–7.2; P = 0.02) and 77–100% (RR 5.6; 95% CI 1.9–19.6; P < 0.01)) compared with those with 0% cytogenetically abnormal cells (RR 1.0). Measuring disease burden by blast percentage, patients with > 10% blasts had worse survival (RR 2.9 (95% CI 1.1–7.2,); P = 0.02) versus patients with ≤ 2% blasts (RR 1.0).

Table 3.

Multiple regression analysis of HCT outcomes by MDS disease variables

| Model | Disease variable | 5-Year OS AIC | 5-Year OS RR (95% CI) | P-value | 1-Year NRM AIC | 1-Year NRM RR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | % Abnormal cells | 463.2 | 267.3 | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 1–36 | 2.0 (0.7–5.5) | 0.18 | 2.0 (0.4–10.6) | 0.44 | |||

| 37–76 | 2.9 (1.2–7.2) | 0.02 | 3.2 (0.7–14.8) | 0.13 | |||

| 77–100 | 5.6 (1.9–16.6) | < 0.01 | 5.7 (1.1–23.0) | 0.04 | |||

| 2 | % Blasts | 469 | 265.2 | ||||

| ≤2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| > 2 to < 5 | 1.7 (0.9–3.1) | 0.09 | 2.4 (1.0–5.5) | 0.04 | |||

| 5–10 | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | 0.53 | 1.8 (0.6–5.0) | 0.29 | |||

| > 10 | 2.9 (1.1–7.2) | 0.02 | 5.0 (1.9–13.2) | < 0.01 | |||

| 3 | R-IPSS cytogenetics | 471.1 | 272.1 | ||||

| Very good/good | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Intermediate | 1.9 (0.9–4.0) | 0.11 | 2.0 (0.7–5.9) | 0.2 | |||

| Poor | 1.0 (0.5–2.3) | 0.96 | 1.8 (0.6–5.4) | 0.26 | |||

| Very poor | 1.4 (0.6–3.1) | 0.39 | 1.5 (0.5–4.6) | 0.52 |

Abbreviations: AIC = Akaike information criterion; CI = confidence interval; HCT = hematopoietic cell transplantation; MDS = myelodysplastic syndrome; NRM = non-relapse mortality; OS = overall survival; R-IPSS = Revised International Prognostic Scoring System; RR = relative risk. Lower AIC = better ’fit’.

Values in bold include the ’better fit’ AIC and statistically significant variables.

We additionally measured the effect of increasing percentages of cytogenetically abnormal cells among the blast percentage groups on 5-year OS (Table 4). Among patients with ≤ 2% blasts, patients with 77–100% cytogenetically abnormal cells had worse survival (RR 4.4; 95% CI 1.1–18.3) compared with patients with 0% abnormal cells (RR 1.0; P = 0.04). Higher percentages of cytogenetically abnormal cells appeared to have less impact on patient outcome as blast percentage increased.

Table 4.

The 5-year overall survival by percentages of blasts and cytogenetically abnormal cells

| % Abnormal cells | Blasts ≤ 2% | Blasts > 2 to 10% | Blasts > 10% | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 5-Year OS RR (95% CI) | P-value | N | 5-Year OS RR (95% CI) | P-value | N | 5-Year OS RR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| 0% | 13 | 1 | 0 | No patients | 0 | No patients | |||

| 1–36% | 12 | 2.3 (0.8–6.5) | 0.13 | 5 | 1 | 0 | No patients | ||

| 37–76% | 15 | 1.8 (0.6–4.9) | 0.28 | 23 | 3.1 (0.7–13.4) | 0.13 | 3 | 1 | |

| 77–100% | 3 | 4.4 (1.1–18.3) | 0.04 | 5 | 4.5 (0.9–23.9) | 0.08 | 3 | 3.3 (0.3–33.4) | IE |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; IE = insufficient event; OS = overall survival; RR = relative risk.

Statistically significant values are indicated in bold.

The 5-year DFS was 20% (95% CI 12–30%) among all patients. The 5-year DFS worsened with increasing percentages of cytogenetically abnormal cells: 0% abnormal cells (38%; 95% CI 14–63%); 1–36% abnormal (34%; 95% CI 13–56%); 37–76% abnormal (15%; 95% CI 6–28%); and 77–100% abnormal (0%; P = 0.02). Blast percentage and R-IPSS cytogenetic stratification at HCT were not associated with 5-year DFS.

GvHD

Overall incidence of aGvHD at 100 days was 27% (95% CI 17–37%). Those with higher disease burden at transplant had higher rates of severe aGvHD. Among patients with 77–100% cytogenetically abnormal cells, the incidence of grade III–IV aGvHD was 73% (95% CI 42–100%; P < 0.01) and among those with > 10% blasts the incidence was 67% (95% CI 29–100%; P < 0.01). In multiple regression analysis the association of severe aGvHD and % cytogenetically abnormal cells remained (RR 8.4; 95% CI 2.0–35.7 for those with 77–100% abnormal cells, P = 0.004). Cumulative incidence of chronic GvHD at 1 year was 30% (95% CI 19–42%) across the entire cohort and was not affected by advanced disease status.

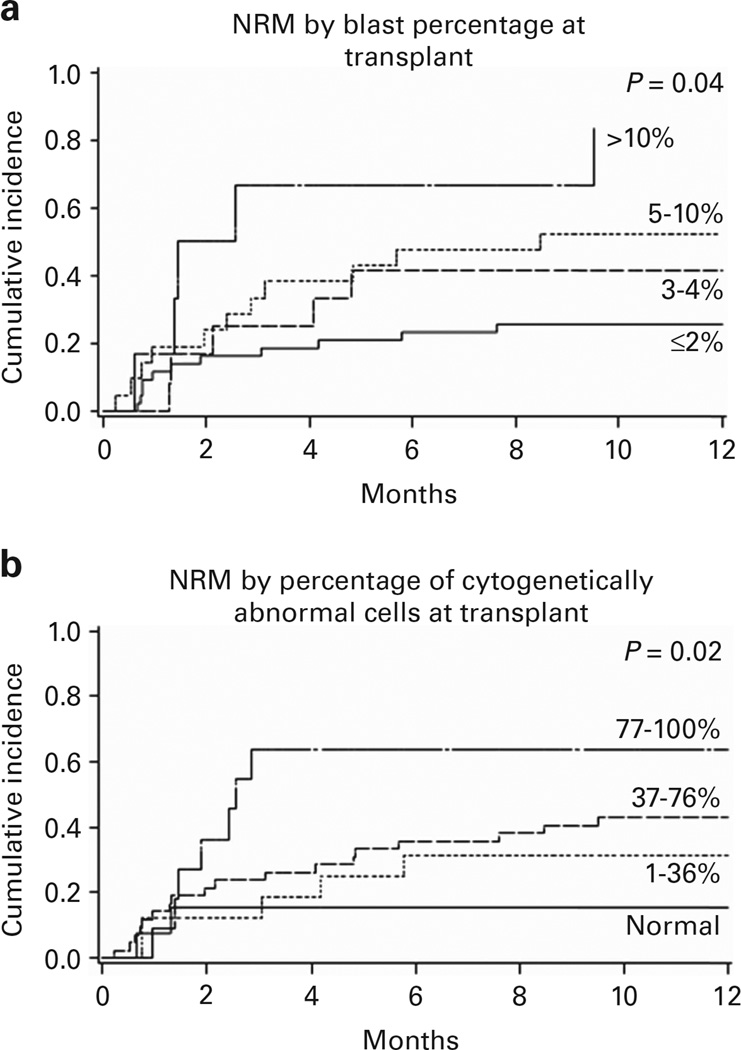

NRM and relapse

NRM at 1 year among all patients was 39% (95% CI 28–50%). Two factors, both measures of disease burden (blast percentage and percentage of abnormal cells at transplant), were associated with increased NRM (Table 2 and Figures 2a and b). NRM among patients with 77–100% cytogenetically abnormal cells (64%; 95% CI 33–95%, 95% CI) was higher than for those with 0% abnormal cells (15%; 95% CI 0–34%) and 1–36% abnormal cells (29%; 95% CI 8–51%; P = 0.02). Patients with > 10% blasts at transplant experienced greater NRM (83%; 95% CI 50–100%, 95% CI) compared with the others: ≤2% (26%; 95% CI 12–39%); > 2 to < 5% (52%; 95% CI 30–75%); and 5–10% (42%; 95% CI 14–69%; P = 0.04). Patient age, Karnofsky performance status, HCT-Comorbidity Index risk, donor type, conditioning regimen, year of transplant, WHO MDS diagnosis, t-MDS and R-IPSS cytogenetic stratification at transplant were not associated with 1-year NRM.

Figure 2.

NRM curves by time-of-transplant disease burden. (a) Blast percentage. (b) Cytogenetically abnormal cell percentage.

Both blast percentage and percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells at HCT were predictive of 1-year NRM but multiple regression analysis highlighted blast percentage as the ‘best fit’ (Akaike information criterion 265.2, P < 0.01) versus percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells (267.3, P = 0.01) and R-IPSS cytogenetic risk category (272.1, P = 0.64; Table 3).

Overall relapse was 27% (95% CI 17–37%) among all patients. No disease or transplant factors were predictive of relapse in either univariate or multivariate analysis because of the high NRM in those with higher pre-HCT disease burden.

DISCUSSION

We tested a novel pre-HCT MDS disease burden assessment, defined by percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells, to predict transplant outcomes. Our observations support the hypothesis that the detection of clonally abnormal cells through standard G-banding techniques may better estimate the true bulk of residual disease compared with blast percentage and be a more accurate assessment of pre-HCT disease burden, extending our previous observations.22 Given the requirement for dividing cells for G-band assessment, further analysis with FISH assessments may be helpful; however, this analysis was not feasible with our cohort because of lack of FISH data in the earlier years of our data cohort.

Optimal pre-HCT disease burden and the method to achieve that state remain controversial. We previously reported inferior post-HCT outcomes with a pre-HCT bone marrow blast percentage of > 5% and also found no difference in outcome based on therapy modality required to achieve a < 5% pre-HCT blast percentage.22 More recently, Della Porta et al.7 reviewed pre-HCT characteristics of 519 MDS and oligoblastic AML (20–29% blasts) patients. They observed inferior OS among patients with > 10% blasts at the time of HCT (P < 0.001). In addition, Damaj et al.6 reported HCT outcomes for 265 MDS patients undergoing allogeneic HCT who had received either hypomethylating agents or induction chemotherapy before HCT. Their data highlight similar 3-year OS, event-free survival, relapse and NRM in patients receiving hypomethylating agents or induction chemotherapy but reveal inferior outcomes in patients requiring both hypomethylating agents and induction chemotherapy, suggesting a more biologic assessment of disease character. Previous studies, including recent reports from our institution, have found R-IPSS cytogenetic risk categorization to be associated with transplant outcomes.23,24 The exclusion of patients with normal diagnostic cytogenetics in our analysis may explain the lack of R-IPSS cytogenetic risk impact on post-HCT outcomes in this patient cohort. We demonstrate the novel finding that even among those patients achieving marked cytoreduction (blasts < 2%), a high percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells still portends a poor outcome.

Our study revealed an incredibly high NRM for those with advanced disease at the time of transplant as measured by either high blast percentage or high percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells. These patients were not found to be more heavily pretreated, were not preferentially transplanted in earlier years and did not have a larger proportion of low Karnofsky performance status. Those with a higher blast % or higher percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells did have higher rates of grade III–IV aGvHD that may account for the higher NRM in those cohorts. It is unclear why these groups would be at higher risk for severe GvHD as they were not more heavily pretreated, were not managed differently post HCT with earlier withdrawal of immunosuppression or post-HCT maintenance therapy. In addition, rates of infectious death were higher in those with 37–76% or 77–100% cytogenetically abnormal cells, regardless of blast percentage and this is likely some explanation for the inferior OS in that lower blast, higher % cytogenetically abnormal cell cohort noted in Table 4. As above, there is no obvious reason for this finding with respect to pre-HCT therapy or post-HCT modifications. The higher NRM in these more advanced MDS patients is a cause for concern and suggests caution regarding treatment choice for this group. Therapies alternative to transplant may be a reasonable consideration in this subset of patients.

Recent advances in molecular-based MDS risk assessment25,26 expand the potential for diagnostic prognostic assessment, therapeutic response assessment and measurement of minimal residual disease. Although these approaches are likely to be the future for MDS disease burden assessment, molecular assessments are yet to be universally or consistently used in current practice. Utilizing the percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells thus remains a viable mode of disease burden assessment for those centers yet to employ routine molecular monitoring in MDS. Its use is limited to those with abnormal karyotype and does not account for the ‘character’ of the cytogenetic abnormality, but these limitations can be overcome by combining our assessment with the diagnostic R-IPSS cytogenetic risk stratification.

Accurate MDS disease burden and biologic assessment is critical to determine optimal HCT timing and improve HCT outcomes. Disease burden assessment using a combination of both blast percentage and percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells along with molecular analyses may provide an additional approach for disease monitoring and as a treatment goal for MDS patients before HCT. Additional study is required to validate these findings in a larger cohort of patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study received funding from the National Institute of Health T32 Training Grant (to BJT and ZS). This work was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute P01 CA65493 (to TED).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Bone Marrow Transplantation website (http://www.nature.com/bmt)

REFERENCES

- 1.Tefferi A, Vardiman JW. Myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1872–1885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, Fenaux P, Morel P, Sanz G, et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 1997;89:2079–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg PL, Tuechler H, Schanz J, Sanz G, Garcia-Manero G, Sole F, et al. Revised international prognostic scoring system for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;120:2454–2465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-420489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutler CS, Lee SJ, Greenberg P, Deeg HJ, Perez WS, Anasetti C, et al. A decision analysis of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for the myelodysplastic syndromes: delayed transplantation for low-risk myelodysplasia is associated with improved outcome. Blood. 2004;104:579–585. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koreth J, Pidala J, Perez WS, Deeg HJ, Garcia-Manero G, Malcovati L, et al. Role of reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in older patients with de novo myelodysplastic syndromes: an international collaborative decision analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2662–2670. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.8652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damaj G, Duhamel A, Robin M, Beguin Y, Michallet M, Mohty M, et al. Impact of azacitidine before allogeneic stem-cell transplantation for myelodysplastic syndromes: a study by the societe francaise de greffe de moelle et de therapiecellulaire and the groupe-francophone des myelodysplasies. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4533–4540. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.3499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Della Porta MG, Alessandrino EP, Bacigalupo A, van Lint MT, Malcovati L, Pascutto C, et al. Predictive factors for the outcome of allogeneic transplantation in patients with MDS stratified according to the revised IPSS-R. Blood. 2014;123:2333–2342. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-542720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheson BD, Greenberg PL, Bennett JM, Lowenberg B, Wijermans PW, Nimer SD, et al. Clinical application and proposal for modification of the international working group (IWG) response criteria in myelodysplasia. Blood. 2006;108:419–425. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia:rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114:937–951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Majhail NS, Brunstein CG, Shanley R, Sandhu K, McClune B, Oran B, et al. Reduced-intensity hematopoietic cell transplantation in older patients with AML/MDS: umbilical cord blood is a feasible option for patients without HLA-matched sibling donors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:494–498. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warlick ED, Tomblyn M, Cao Q, Defor T, Blazar BR, Macmillan M, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning followed by related allografts in hematologic malignancies: long-term outcomes most successful in indolent and aggressive non-hodgkin lymphomas. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1025–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ustun C, Wiseman AC, Defor TE, Yohe S, Linden MA, Oran B, et al. Achieving stringent CR is essential before reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in AML. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:1415–1420. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin DY. Non-parametric inference for cumulative incidence functions in competing risks studies. Stat Med. 1997;16:901–910. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970430)16:8<901::aid-sim543>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray R. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarone RE. Tests for trend in life table analysis. Biometrika. 1975;62:679–682. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J Royal Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the sub-distribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colett D. Modelling Survival Data in Medical Research. London, UK: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.LeBlanc M, Crowley J. Relative risk trees for censored survival data. Biometrics. 1992;48:411–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bozdogan H. Model selection and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC): the general theory and its analytical extensions. Phychometrika. 1987;52:345–370. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warlick ED, Cioc A, DeFor T, Dolan M, Weisdorf D. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for adults with myelodysplastic syndromes: importance of pretransplant disease burden. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ustun C, Trottier BJ, Sachs Z, DeFor TE, Shune L, Courville EL, et al. Monosomal karyotype at the time of diagnosis or transplantation predicts outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in myelodysplastic syndrome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:866–872. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deeg HJ, Scott BL, Fang M, Shulman HM, Gyurkocza B, Myerson D, et al. Five-group cytogenetic risk classification, monosomal karyotype, and outcome after hematopoietic cell transplantation for MDS or acute leukemia evolving from MDS. Blood. 2012;120:1398–1408. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-423046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bejar R, Stevenson K, Abdel-Wahab O, Galili N, Nilsson B, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2496–2506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bejar R, Stevenson KE, Caughey B, Coleman Lindsley R, Mar BG, Stojanov P, et al. Somatic mutations predict poor outcome in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2691–2697. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.