Abstract

Background

Poor gait performance predicts risk of developing dementia. No structured critical evaluation has been conducted to study this association yet. The aim of this meta-analysis was to systematically examine the association of poor gait performance with incidence of dementia.

Methods

An English and French Medline search was conducted in June 2015, with no limit of date, using the medical subject headings terms “Gait” OR “Gait Disorders, Neurologic” OR “Gait Apraxia” OR “Gait Ataxia” AND “Dementia” OR “Frontotemporal Dementia” OR “Dementia, Multi-Infarct” OR “Dementia, Vascular” OR “Alzheimer Disease” OR “Lewy Body Disease” OR “Frontotemporal Dementia With Motor Neuron Disease” (Supplementary Concept). Poor gait performance was defined by standardized tests of walking, and dementia was diagnosed according to international consensus criteria. Four etiologies of dementia were identified: any dementia, Alzheimer disease (AD), vascular dementia (VaD), and non-AD (ie, pooling VaD, mixed dementias, and other dementias). Fixed effects meta-analyses were performed on the estimates in order to generate summary values.

Results

Of the 796 identified abstracts, 12 (1.5%) were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. Poor gait performance predicted dementia [pooled hazard ratio (HR) combined with relative risk and odds ratio = 1.53 with P < .001 for any dementia, pooled HR = 1.79 with P < .001 for VaD, HR = 1.89 with P value < .001 for non-AD]. Findings were weaker for predicting AD (HR = 1.03 with P value = .004).

Conclusions

This meta-analysis provides evidence that poor gait performance predicts dementia. This association depends on the type of dementia; poor gait performance is a stronger predictor of non-AD dementias than AD.

Keywords: Epidemiology, gait disorders/ataxia, motor control, dementia

Both gait and cognitive disorders are frequent in the elderly with a prevalence reaching 50% among individuals aged 85 years and older.1–4 This association exceeds a simple accumulation with aging and relies on a causal relationship.4,5 Cognitive dysfunction may result in gait disorders by disorganizing the highest levels of gait control.5–7 However, the chronological development of gait disorders caused by cognitive dysfunctions in the context of the progression of dementia and its clinical application have been poorly studied.

Identifying clinical markers that predict dementia is an important issue for the implementation of adapted care, better understanding of early brain disorganization, and, thus, for implications for preventive and symptomatic interventions.8–11 The emergence of brain imaging and biological markers contributes extensively to the early diagnosis of dementia,8–10 but the high expense limits their use, especially in primary care and community-dwelling populations.12–14 Recently, a syndrome combining cognitive complaint and slow gait speed, called the “motoric cognitive risk” (MCR) syndrome, has been associated with the occurrence of dementia.15,16 The uniqueness of the MCR syndrome is that it does not rely on a complex evaluation or laboratory investigations and, thus, is easy to apply clinically with low costs in large populations.16 This observation suggests that the assessment of gait performance may be useful for predicting dementia.1,15–25

At this time, no systematic critical evaluation of studies that have examined the association of poor gait performance and the occurrence of dementia has been performed, making it unclear whether poor gait performance can be used as an accurate predictor of dementia. Thus, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis with the aim to qualitatively and quantitatively synthesize the association of poor gait performance with incidence of dementia.

Methods

Search Strategy and Data Extraction

A systematic search was conducted in June 2015 with no time limit for all English and non-English articles in Medline (PubMed) and EMBASE (Ovid, EMBASE). Following medical subject heading terms “Gait” OR “Gait Disorders, Neurologic” OR “Gait Apraxia” OR “Gait Ataxia” AND “Dementia” OR “Frontotemporal Dementia” OR “Dementia, Multi-Infarct” OR “Dementia, Vascular” OR “Alzheimer Disease” OR “Lewy Body Disease” OR “Frontotemporal Dementia With Motor Neuron Disease” (Supplementary Concept) were used. Additional studies, not captured by the electronic database search, were identified by contacting experts and searching reference lists of extracted papers. Two authors (OB and GA) independently conducted data extraction. A consensus procedure was developed but was not necessary because of concordance.

Study Selection

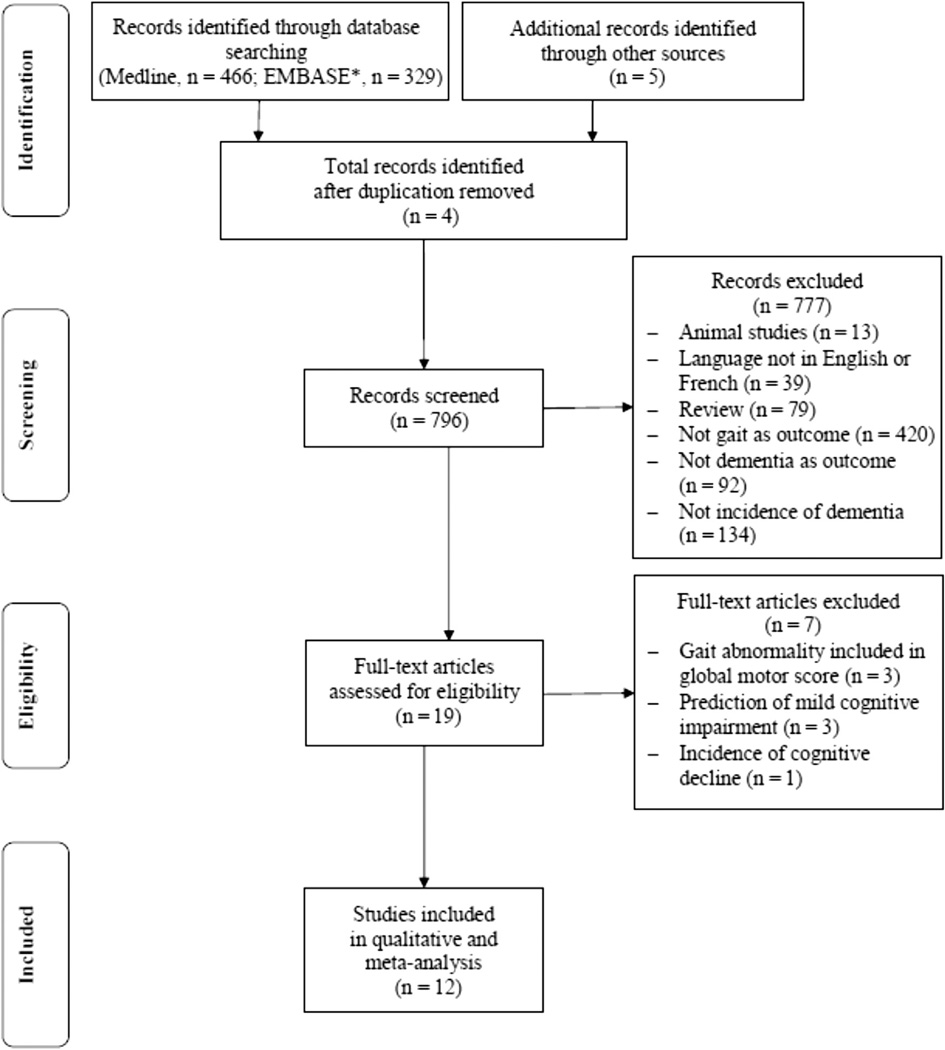

To be included in the primary analysis, selection criteria were (1) human study, (2) article published in English or French, (3) original study, (4) data collection of gait performance, (5) dementia used as outcome, and (6) prospective cohort design with information on the occurrence of dementia during the follow-up period. If a study met the initial selection criteria or its eligibility could not be determined from the title and abstract (or abstract not provided), the full text was retrieved. Two reviewers (OB and GA) then independently assessed the full text for inclusion status. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (CA). The full articles were screened using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist, which describes items that should be included in reports of cohort studies.26 Furthermore, the quality of each study included in the meta-analysis was assessed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist and the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.27,28 Final selection of criteria was, therefore, applied when at baseline assessment participants were free of dementia and when the prediction was about dementia. The study selection procedure is presented in the PRISMA flow diagram27 (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of selection of studies. *Ovid EMBASE.

Qualitative Analysis

Of the 796 identified abstracts, 19 (2.4%) met the initial inclusion criteria.1,15–25,29–35 After examination, we excluded 7 of those 19 studies because gait performance was included in a global motor score,29–31 prediction concerned mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and not dementia,32–34 and 1 study focused on cognitive decline and not cognitive status.35 The remaining 12 studies were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis1,15–25 Articles selected for the full review had the following information extracted: last name of authors and date of publication; country, name, and design of study, participant generic information (ie, setting, number of participants and proportion of women); age, cognitive status, and gait measures at baseline assessment; length of follow-up period; incident cases of dementia including number of individuals and etiology; and main results.

Meta-Analysis

The association between poor gait performance and occurrence of dementia was determined using the adjusted hazard ratio (HR), the adjusted relative risk (RR,) or the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for dementia with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). In all cases, the longest follow-up period was used to calculate HR, RR, and OR, and only adjusted values of participant’s baseline characteristics were used. The analyses used different outcomes: any dementia, Alzheimer disease (AD), vascular dementia (VaD), and non-AD (ie, pooling VaD, mixed dementias, and other dementias) for the dependent variables, and poor gait performance, estimated from gait score or gait speed, as independent variables. Poor gait performance was defined by standardized tests based on clinical gait assessment of distance walked on a defined distance or per day. Dementia was diagnosed according to the established international consensus criteria. Fixed effects meta-analyses were performed on the estimates to generate summary values. Results are presented as forest plots. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using Cochrane χ2 test for homogeneity, and the amount of variation because of heterogeneity was estimated by calculating the I2.36 Statistical analyses were performed using the software program WINPEPI Computer Programs for Epidemiologists (v 11.48).37

Results

Table 1 summarizes the 12 studies included in this review.1,15–25 All studies were published over the last 13 years. Seven studies were conducted in the United States.1,15,18,20,22,23,25 The 4 other studies were conducted in Norway,17 France,19 The Netherlands,21 and Australia.24 One study combined cohorts from different countries.16 The number of participants ranged from 17117 to 3855,16 with 0%18 to 100%19 women. All participants were older adults at baseline, aged from ≥6016,17 to ≥751,19, 23, 24 years. Data collection was based on observational studies with longitudinal prospective cohort design, except in 1 study, which used a retrospective case-control design.21 At baseline, all participants were free of dementia.1,15–25 Two studies included participants with MCI,20,25 2 studies included participants with MCR,15,16 and 1 study selected participants with Parkinson disease (PD).17 Gait speed at usual pace at baseline assessment was used as the main outcome in 6 studies.15,16,19,20,24,25 In 3 of them, the gait speed value was categorized using quartile segmentation, and a scaled score was built from slowest to fastest gait speed.19,20,25 Clinical gait abnormalities were used as the predictor in three studies.1,17,21 In the first study, they corresponded to falls and problems with walking.21 In the second study, clinical gait abnormalities were rated as unsteady gait, frontal gait, hemiparetic gait, neuropathic gait, ataxic gait, parkinsonian gait, and spastic gait.1 In the third one, clinical gait abnormalities were based on an abnormal score for the gait items of Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale subscales II and III.17 In 1 study, poor gait performance combined slow gait speed and extrapyramidal symptoms (based on the presence of bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor)24; while in the other one, they were defined as the presence of hemiparetic, frontal, or unsteady gait.23 Abnormalities in pace, rhythm, and variability were used to define poor gait performance in 1 study.22 In addition, in another study, the distance walked per day expressed in miles and separated in 4 levels from <0.25 (ie, lowest) to >2 (highest) miles was used for defining poor gait performance. The length of follow-up ranged from 315 to 916 years. In 5 studies, incidental cases of the 5 subgroups of dementia were recorded (ie, any dementia, AD, non-AD, VaD, mixed, and other dementias). Any dementia was recorded in 2 studies21,24 and AD20 and VaD23 in 1 study. One study recorded AD and any dementia,16 whereas another one reported any dementia, AD, and VaD.22 One study reported incidence of dementia in patients with PD. Incidence of dementia during the follow-up ranged from 6.5%23 to 52.9%.17 Most studies found an association between poor gait performance and occurrence of any dementia, except in 2 studies.15,25 In a study by Verghese et al,15 a nonsignificant association was reported for slow gait speed (excluding participants with MCR), whereas a significant association was found with MCR. The nonsignificant association reported in a study by Waite et al24 was present for the follow-up at 6 years, but not at 3 years [OR 3.6 (1.2;10.3)]. Results were more controversial regarding AD onset. Four studies found a significant association,16,18,20,25 whereas 3 studies did not.1,15,22,25 In a study by Aggarwal et al,20 both significant and nonsignificant associations were reported, when considering gait speed and Parkinson gait score. Gait disturbances were associated with the occurrence of VaD, except in 1 study.18 For non-AD, a significant association was reported in 1 study,1 whereas others found a nonsignificant association.16,18 Finally, the highest HR value reported was 80.0 for PD dementia.17

Table 1.

Summary of the Main Characteristics of Selected Studies (n = 11) Included in the Qualitative Systematic Review Exploring the Association Between Poor Gait Performance and Occurrence of Dementia

| References | Country/Name and Design of Study/ Participants (Setting, Number, Women %) |

Baseline Assessment |

Length of Follow-Up, Years |

Incidence Cases of Dementia (Number of Individuals, Etiology*) |

Main Results† [95% CI] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, (Years) | Cognitive Status | Gait Measures | |||||

| Alves, 200617 |

|

≥60 |

|

|

8 |

|

|

| Abbott, 200418 |

|

>70 |

|

|

7 |

|

|

| Abellan van Kan, 201319 |

|

≥75 |

|

|

7 |

|

|

| Aggarwal, 200620 |

|

79 |

|

|

7 |

|

|

| Ramakers, 200721 |

|

79 |

|

|

5 |

|

|

| Verghese, 20021 |

|

75 to 85 |

|

|

7 |

|

|

| Verghese, 200722 |

|

≥70 |

|

|

5 |

|

|

| Verghese, 200723 |

|

75 to 85 |

|

|

5 |

|

|

| Verghese, 201315 |

|

≥70 |

|

|

3 |

|

|

| Verghese, 201416 |

|

≥60 |

|

|

5 to 9 |

|

|

| Waite, 200524 |

|

≥75 |

|

|

6 |

|

|

| Wang, 200625 |

|

≥65 |

|

|

6 |

|

|

CHI, cognitively healthy individuals; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MCR, motoric cognitive risk; EPIDOS, epidémilogie de l’ostéoporose; H-EPESE, Hispanic established population for epidemiologic study of the elderly; m, meter; MAP, Memory and aging project; ROS, religious orders study; N, number of participants; S, second; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale; US, United States of America.

AD, non-AD [VaD, mixed dementia (vascular plus neurodegenerative dementia) and other dementia.

All results at least adjusted on age and gender and only longest follow-up period information is considered in the analysis.

Based on modified version of the motor portion of the UPDRS (gait disorders classification based on 6 items).

Falls and problem with walking.

Including unsteady gait, frontal gait, hemiparetic gait, neuropathic gait, ataxic gait, parkinsonian gait, and spastic gait.

Spatiotemporal gait analysis providing quantitative values obtained from GAITRite system and 2 consecutive trials at usual pace.

Gait factors (ie) used as continuous variable in Cox models.

Presence of any one of hemiparetic, frontal and unsteady gaits.

Association of absence of dementia plus cognitive complaint plus slower gait speed (defined as 1 standard deviation or more below age and sex appropriate mean values).

Associated with other extrapyramidal features including bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor.

By 1-point decrease in gait speed score.

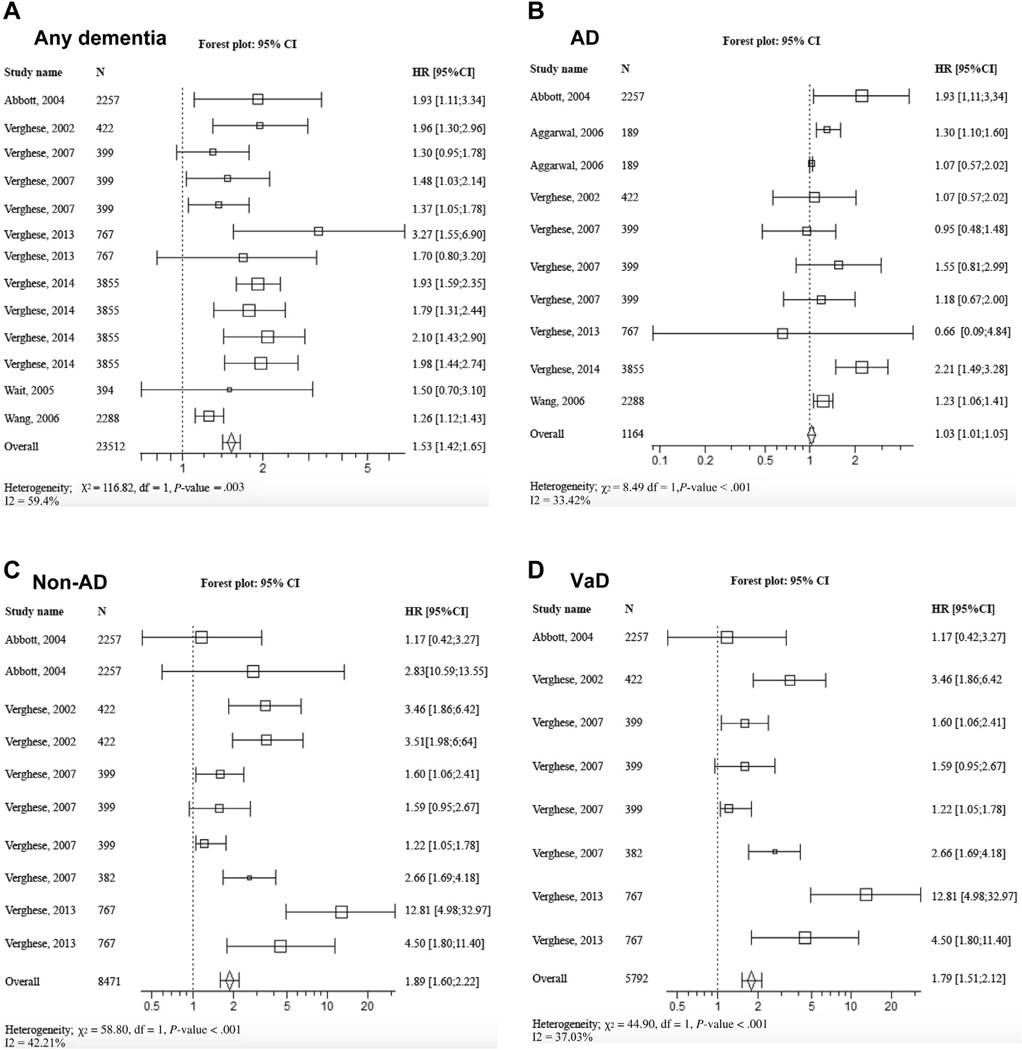

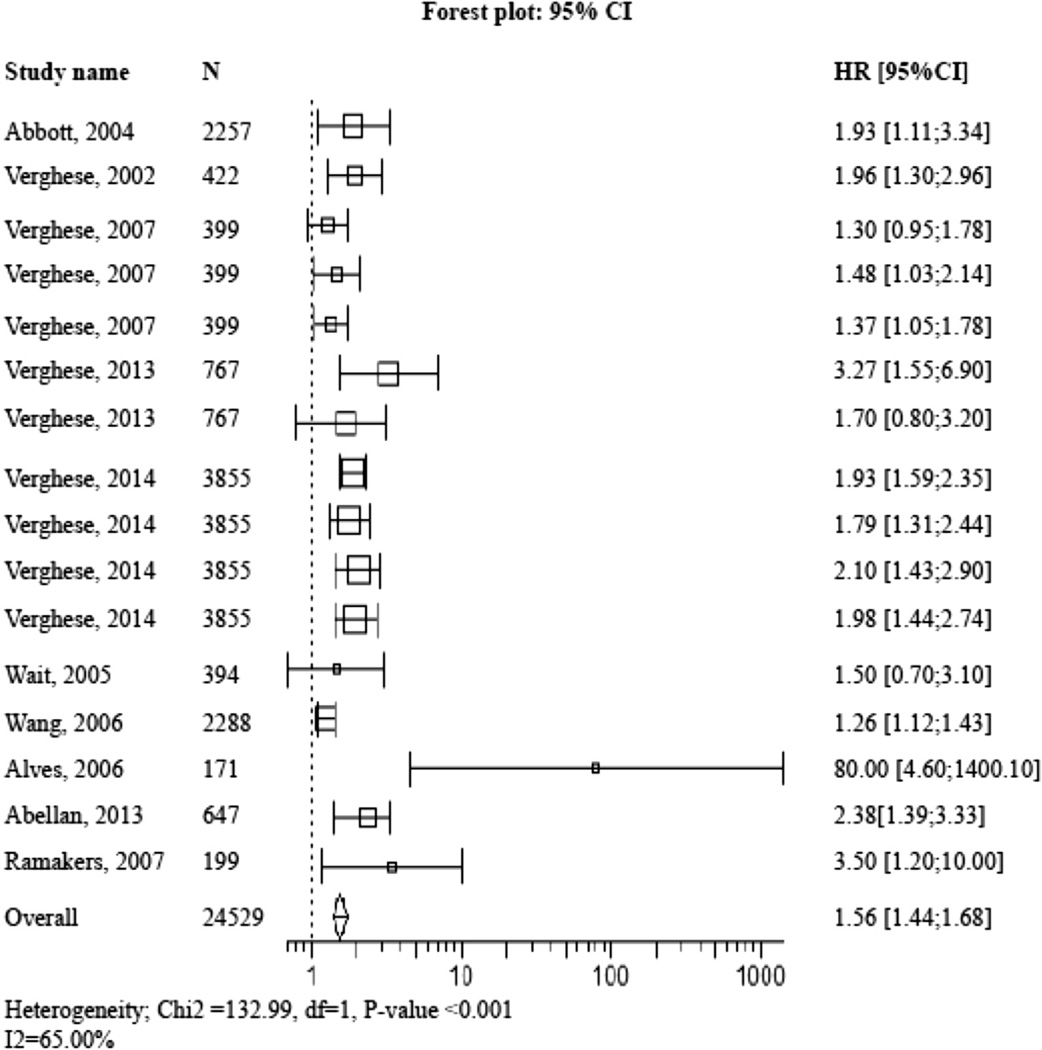

Figure 2 shows the forest plot of pooled HR and RR of incident dementias computed with meta-analysis technique. The pooled HR and RR was 1.53 (95% CI 1.42–1.65) with P value < .001 for any dementia,1.03 (95% CI 1.01–1.05) with P value = .004 for AD,1.89 (95% CI 1.60–2.22) with P value < .001 for non-AD, and 1.79 (95% CI 1. 51–2.12) with P value < .001 for VaD. When pooling all values (ie, HR, RR, and OR), the overall value was 1.56 (95% CI 1.44–.68) with P value < .001 for any dementia (Figure 3).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of pooled estimated HR for risk of incident dementia. (A) Any dementia, (B) AD, (C) non-AD, and (D) VaD in participants with abnormal gait at baseline compared with those with normal gait. Square box area proportional to the sample size of each study; horizontal lines corresponding to the 95% CI; diamond representing the summary value; vertical line corresponding to a HR combined with RR of 1.00, equivalent to no difference.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of pooled estimated HR pooled with OR for risk of incident of any dementia in participants with abnormal gait at baseline compared with those with normal gait. Square box area proportional to the sample size of each study; horizontal lines corresponding to the 95% CI; diamond representing the summary value; vertical line corresponding to a HR combined with RR and OR of 1.00, equivalent to no difference.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis provide evidence that poor gait performance predicts dementia, especially when considering non-AD and VaD. Findings are more inconsistent for the prediction of AD; some studies showed a significant association whereas others did not, and the pooled effect for AD was weaker than that seen with non-AD dementias as the outcome.

The main findings of this meta-analysis confirm that poor gait performance predicts the occurrence of dementia after a long follow-up period. Poor gait performance, regardless of how it was defined, was present between 3 and 9 years before dementia was diagnosed, which provides evidence for a close relationship between gait and cognitive dysfunctions, and its directionality. Indeed, 92% of the studies were based on a longitudinal prospective cohort design providing information on the chronological but not causal relationship. Poor gait performance precedes clinical symptoms of dementia; this chronological association is especially due to brain lesions caused by vascular and/or neurodegenerative processes.1 Indeed, there is increasing evidence that poor motor performance is caused by brain damage related to cognitive decline.1,5–7 These motor disorders lead to poor gait performance and gait instability, and are usually provoked by a disorganization of the brain regions involved in the highest levels of gait control at the onset of dementia.5–7 Recently, it has been reported, in a sample of 1719 participants (77.4 ± 7.3 years, 53.9% female) separated into cognitively healthy individuals, patients with amnestic and nonamnestic MCI, and patients with mild and moderate stages of AD and non-AD, that performance of spatiotemporal gait parameters declined in parallel to the stage of cognition, from MCI to moderate dementia.38 Gait parameters of patients with nonamnestic MCI were more disturbed compared with patients with amnestic MCI; MCI subgroups performed better than demented patients.38

Gait control depends largely on cognition6; disturbed cognitive performance is responsible for poorer gait performance and greater instability in patients with dementia or pre-dementia stages such as MCI or MCR, but also in cognitively healthy individuals.1,5–7,39 In particular, episodic memory and executive function have been separately associated with gait performance in the 2 latter categories of nondemented individuals.40–42 Thus, we suggest that, in the recruited samples composed of participants free of dementia, those with poor gait performance were those with most altered brain health and, thus, who were most exposed to dementia. Therefore, measures of gait performance could be a simple and accessible way to predict dementia in large populations compared with psychometric assessment, and morphologic and biologic biomarkers,15,16 which is especially relevant for the early diagnosis of dementia in primary care or developing countries.

Our findings also show that the prediction of dementia depends on its subtype. Poor gait performance, particularly slow walking speed, predicted VaD with the third highest value reported (HR 3.46 and pooled HR 1.79). This strong association is likely to be related to abnormalities in white matter and basal ganglia that are frequently implicated in VaD.43–45 Recently, the strong association between VaD and mobility impairment was underscored. Indeed, Tolea et al30 reported that the specific etiology of dementia may play an important role in how rapidly one progresses to disability. They reported that non-AD dementias, in general, and VaD, in particular, were associated with a faster decline in physical functionality compared with AD and normal cognition in a longitudinal study of 766 older adults whose physical performance and cognitive status were assessed annually. In addition, it has also been shown that patients with non-AD dementia, including VaD, had worse gait performance than those with AD dementia.38 The highest value (HR 80.0) reported in the study focusing on PD supports the involvement of the basal ganglia, especially the dopaminergic pathway. In contrast, the prediction of AD remains more uncertain because of both conclusive and inconclusive associations, and of low significant pooled value of 1.03. Certain explanations could be related to the type of gait performance recorded in the studies selected in this meta-analysis (no common cut-off value for gait speed across the studies) or by the various inclusion criteria for age ranging from ≥60 to ≥75. In studies showing inconclusive associations, poor gait performance was usually defined clinically without reference to spatiotemporal and, thus, objective parameters (ie, unsteady gait, frontal gait, hemiparetic gait, neuropathic gait, ataxic gait, parkinsonian gait or spastic gait). Gait examination based on a clinical observation of health professionals has 2 main limitations: its subjectivity depending on the background and the experience of the person who performed the gait assessment that may lead to a poor inter-rater reliability; and its limited extent of information. Recently, it was reported that in older community-dwellers without dementia, higher (ie, worse) stride-to-stride variability of stride time (STV; gait cycle duration) was associated with lower (ie, worse) cognitive performance in episodic memory and executive function.38 The results of a meta-analysis confirmed this finding by underscoring that higher STV was related to both MCI and dementia.38 Thus, higher STV appears to be a motor phenotype of cognitive decline both before and during the course of dementia.

Some potential limitations of this systematic review and metaanalysis should be considered. The inclusion of various ages, limited number of studies, different gait protocols employed in included studies (quantitative vs clinical), different lengths of respective follow-up, inclusion of older adults only from developed countries, and various proportions of women may limit the generalization of the present findings. In addition, it is important to consider that most of the studies included in the meta-analysis were performed by the same group; this may further limit extension of our results to the general population.

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis provides evidence that poor gait performance predicts dementia. The association depends on the type of dementia; poor gait performance more consistently predicts VaD than AD. The predictive value for AD remains uncertain because of mixed results and low value of HR (1.03). The exploration of the association between poor gait performance and dementia may improve our knowledge on the interaction of disorganization of brain functions with cognitive decline being more likely associated with the highest level of gait control. Perspectives on improving dementia prediction may rely on the use of more specific markers of the highest level of gait control such as the STV, or the combined use of measures of gait performance with other clinical markers of dementia such as cognitive performance.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the authors of the selected articles for providing additional data required for meta-analysis.

The statistical analysis was conducted by Olivier Beauchet, MD, PhD. G Allali is supported by a grant from the Geneva University Hospitals and the Resnick Gerontology Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Yeshiva University.

The study was supported by “Biomathics.” The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Verghese J, Lipton RB, Hall CB, et al. Abnormality of gait as a predictor of non-Alzheimer’s dementia. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1761–1768. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander NB. Gait disorders in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:434–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb06417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Odenheimer G, Funkenstein HH, Beckett L, et al. Comparison of neurologic changes in ‘successfully aging’ persons vs the total aging population. Arch Neurol. 1994;51:573–580. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540180051013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nutt JG. Classification of gait and balance disorders. Adv Neurol. 2001;87:135–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montero-Odasso M, Verghese J, Beauchet O, Hausdorff JM. Gait and cognition: A complementary approach to understanding brain function and the risk of falling. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:2127–2136. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seidler RD, Bernard JA, Burutolu TB, et al. Motor control and aging: Links to age-related brain structural, functional, and biochemical effects. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34:721–733. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beauchet O, Allali G, Montero-Odasso M, et al. Motor phenotype of decline in cognitive performance among community-dwellers without dementia: Population-based study and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: The IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:614–629. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris JC, Blennow K, Froelich L, et al. Harmonized diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations. J Intern Med. 2014;275:204–213. doi: 10.1111/joim.12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings JL, Dubois B, Molinuevo JL, Scheltens P. International Work Group criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Med Clin North Am. 2013;97:363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anand R, Gill KD, Mahdi AA. Therapeutics of Alzheimer’s disease: Past, present and future. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76:27–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Handels RL, Joore MA, Tran-Duy A, et al. Early cost-utility analysis of general and cerebrospinal fluid-specific Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers for hypothetical disease-modifying treatment decision in mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:896–905. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthews FE, Arthur A, Barnes LE, et al. Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Collaboration. A two-decade comparison of prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 years and older from three geographical areas of England: Results of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study I and II. Lancet. 2013;382:1405–1412. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61570-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, et al. The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verghese J, Wang C, Lipton RB, Holtzer R. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome and the risk of dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:412–418. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verghese J, Annweiler C, Ayers E, et al. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome: Multicountry prevalence and dementia risk. Neurology. 2014;83:718–726. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alves G, Larsen JP, Emre M, et al. Changes in motor subtype and risk for incident dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1123–1130. doi: 10.1002/mds.20897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abbott RD, White LR, Ross GW, et al. Walking and dementia in physically capable elderly men. JAMA. 2004;292:1447–1453. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.12.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abellan van Kan G, Rolland Y, Gillette-Guyonnet S, et al. Gait speed, body composition, and dementia. The EPIDOS-Toulouse cohort. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:425–432. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aggarwal NT, Wilson RS, Beck TL, et al. Motor dysfunction in mild cognitive impairment and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1763–1769. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.12.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramakers IH, Visser PJ, Aalten P, et al. Symptoms of preclinical dementia in general practice up to five years before dementia diagnosis. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24:300–306. doi: 10.1159/000107594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verghese J, Wang C, Lipton RB, et al. Quantitative gait dysfunction and risk of cognitive decline and dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:929–935. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.106914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verghese J, Derby C, Katz MJ, Lipton RB. High risk neurological gait syndrome and vascular dementia. J Neural Transm. 2007;114:1249–1252. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0762-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waite LM, Grayson DA, Piguet O, et al. Gait slowing as a predictor of incident dementia: 6-year longitudinal data from the Sydney Older Persons Study. J Neurol Sci. 2005;229–230:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Larson EB, Bowen JD, van Belle G. Performance-based physical function and future dementia in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1115–1120. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. [Accessed March 25, 2015];The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2013 Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 29.Buchman AS, Leurgans SE, Boyle PA, et al. Combinations of motor measures more strongly predict adverse health outcomes in old age: The rush memory and aging project, a community-based cohort study. BMC Med. 2011;9:42. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tolea MI, Morris JC, Galvin JE. Trajectory of mobility decline by type of dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2015 doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000091. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tolea MI, Morris JC, Galvin JE. Longitudinal associations between physical and cognitive performance among community-dwelling older adults. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buracchio T, Dodge HH, Howieson D, et al. The trajectory of gait speed preceding mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:980–986. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Camicioli R, Howieson D, Oken B, et al. Motor slowing precedes cognitive impairment in the oldest old. Neurology. 1998;50:1496–1498. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marquis S, Moore MM, Howieson DB, et al. Independent predictors of cognitive decline in healthy elderly persons. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:601–606. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mielke MM, Roberts RO, Savica R, et al. Assessing the temporal relationship between cognition and gait: Slow gait predicts cognitive decline in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:929–937. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abramson JH. WINPEPI updated: Computer programs for epidemiologists, and their teaching potential. Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2011;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-5573-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allali G, Annweiler C, Blumen HM, et al. Gait phenotype from mild cognitive impairment to moderate dementia: Results from the GOOD initiative. Eur J Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/ene.12882. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beauchet O, Annweiler C, Verghese J, et al. Biology of gait control: Vitamin D involvement. Neurology. 2011;76:1617–1622. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318219fb08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ble A, Volpato S, Zuliani G, et al. Executive function correlates with walking speed in older persons: The InCHIANTI study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:410–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hausdorff JM, Yogev G, Springer S, et al. Walking is more like catching than tapping: Gait in the elderly as a complex cognitive task. Exp Brain Res. 2005;164:541–548. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-2280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beauchet O, Annweiler C, Montero-Odasso M, et al. Gait control: A specific subdomain of executive function? J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2012;9:12. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosso AL, Olson Hunt MJ, Yang M, et al. Health ABC study. Higher step length variability indicates lower gray matter integrity of selected regions in older adults. Gait Posture. 2014;40:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.03.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosano C, Sigurdsson S, Siggeirsdottir K, et al. Magnetization transfer imaging, white matter hyperintensities, brain atrophy and slower gait in older men and women. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1197–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosano C, Brach J, Studenski S, et al. Gait variability is associated with sub-clinical brain vascular abnormalities in high-functioning older adults. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29:193–200. doi: 10.1159/000111582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]