Abstract

Context

Although many studies have addressed the integration of a religion and/or spirituality curriculum into medical school training, few describe the process of curriculum development based on qualitative data from students and faculty.

Objectives

The aim of this study is to explore the perspectives of medical students and chaplaincy trainees regarding the development of a curriculum to facilitate reflection on moral and spiritual dimensions of caring for the critically ill and to train students in self-care practices that promote professionalism.

Methods

Research staff conducted semiscripted and one-on-one interviews and focus groups. Respondents also completed a short and self-reported demographic questionnaire. Participants included 44 students and faculty members from Harvard Medical School and Harvard Divinity School, specifically senior medical students and divinity school students who have undergone chaplaincy training.

Results

Two major qualitative themes emerged: curriculum format and curriculum content. Inter-rater reliability was high (kappa = 0.75). With regard to curriculum format, most participants supported the curriculum being longitudinal, elective, and experiential. With regard to curriculum content, five subthemes emerged: personal religious and/or spiritual (R/S) growth, professional integration of R/S values, addressing patient needs, structural and/or institutional dynamics within the health care system, and controversial social issues.

Conclusion

Qualitative findings of this study suggest that development of a future medical school curriculum on R/S and wellness should be elective, longitudinal, and experiential and should focus on the impact and integration of R/S values and self-care practices within self, care for patients, and the medical team. Future research is necessary to study the efficacy of these curricula once implemented.

Keywords: Religion, spirituality, curriculum development, medical school, wellness

Introduction

The relationship between religion and/or spirituality (R/S) and medicine, and particularly the role of the physician in addressing the patient’s spiritual needs, is an emerging area of research. Although many studies have shown that R/S are frequently important to patients’ experience with illness,1 the role of physicians in this process is unclear.2 Most physicians and patients believe that some engagement of patients’ R/S is appropriate, especially in life-threatening disease.3–9 National standards for hospice and palliative care have increasingly incorporated guidelines for engaging patients’ spiritual needs and require training for medical professionals in this area;10,11 however, patients frequently report that their physicians have never discussed R/S beliefs with them.3,6,12 Furthermore, many medical professionals report a desire to provide spiritual care in the setting of terminal illness but typically provide spiritual care less often than desired.4,13 Inadequate training is the strongest predictor of infrequent spiritual care provision.13,14 Therefore, development of medical professional training in R/S would be a strategic intervention to ensure that spiritual care occurs at the level desired by patients, medical providers, and as mandated by national guidelines.

R/S is also related to physician formation and well-being. Because physicians are more than technicians,15 their role as healers partly relies on their moral and spiritual development and character.16,17 Thus, physicians’ R/S are associated with risk of burnout,18 moral distress, and compassion fatigue.19–21 Practices of self-care, including self-awareness of the physician’s own needs in conjunction with patient needs, support physicians’ well-being.22,23 Likewise, physicians are more likely to feel confident in discussing spirituality with patients when they are comfortable in their own spirituality.24,25 Spiritual awareness on behalf of the physician is intrinsic to addressing the spirituality of patients. Spiritual care training can facilitate this process of self-awareness.24

Integrated spiritual care training early in the process of professionalization of physicians may be an optimal time to address this inadequacy. Some studies have examined the feasibility and efficacy of incorporating R/S into medical school education,26–31 including studies that have developed and tested curricula.30,32,33 In 1993, only three (2.3%) U.S. medical schools provided training on R/S issues as applied to medicine.34 These numbers have increased with more than 100 (80%) medical schools now providing some training in R/S.31,34,35 However, previous studies often lack specifics about course content and thus are difficult to draw on to guide course development.36 Furthermore, few previous studies describe the process of curriculum development for such training or have incorporated a needs assessment from the perspective of medical students.36 There is a need for ongoing development of medical school curricula that address R/S within the practice of medicine.

The aim of this study was to explore the perspectives of medical and divinity students and faculty to develop a curriculum within a university health care setting. The interviews and focus groups sought to identify the key components for a curriculum centered on wellness, self-care, and R/S for health care professionals to improve care of both self and others. Interviewees included both medical and divinity school participants and both students and faculty. Medical faculty were involved to provide an experienced, administrative, and long-term perspective, whereas medical students were included to provide their proximate views of trainee needs and of how to integrate R/S within medical school training. Furthermore, because medical school training within R/S typically lacks attention to trainee spiritual formation, we included divinity faculty and students experienced within health care chaplaincy. Divinity chaplaincy training and professional development involve extensive attention to trainee spiritual formation, and hence their perspectives were garnered to provide insights into methods of facilitating trainee psychological, moral, and spiritual reflections. This exploratory qualitative study engaged the question: “How do we develop a curriculum that facilitates reflection on psychological, moral, and spiritual experiences in caring for the critically ill and trains future professional caregivers in practices of self-care undergirding professionalism?”

Methods

Sample

Eligible Harvard Medical School (HMS) students were fourth-year medical students currently participating in clinical rotations or second-degree programs (e.g., Master of Public Health programs) and residents who recently graduated from HMS. Eligible HMS faculty were senior faculty members whose roles involve regular interaction with medical students and identified by medical student research staff as being open to discussing medical education and R/S. Eligible Harvard Divinity School (HDS) students were masters’ students who had completed at least one unit of Clinical Pastoral Education or an equivalent clinical chaplaincy training program. Eligible HDS faculty were professors and advisors who directly taught and worked with students in chaplaincy training programs. All participants (N = 44) provided informed consent according to protocols approved by the Harvard University Faculty of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Protocol

Students and faculty were enrolled between August 1, 2013 and December 15, 2013. For the medical students, student representatives on the research team familiar with the HMS community (Z. D. E.- P. and A. A.) identified other students and faculty who would provide a range of perspectives on medical training. The protocol sought a diversity of participants by choosing students from a range of spiritual backgrounds, race and/or ethnicities, genders, and specialty interests, as known and identified by research staff. Recruitment followed chain-referral sampling37 by which participants selected by research staff recommended other students or faculty who may be interested in participating. For the divinity students, the Office of Ministry Studies at HDS advertised the focus group opportunity via e-mail to the 14 eligible HDS students who had completed or were currently enrolled in Clinical Pastoral Education or chaplaincy training. Because the source population was small, all students who responded were included. A semi-structured interview guide was developed by an interdisciplinary expert panel of medical educators and religious experts (Table 1). R/S was undefined in the interviews to avoid superimposing a particular definition. The protocol enabled students’ and faculty members’ own definitions of these terms to shape focus group content. Research staff underwent a half-day training session in interview methods and received ongoing supervisory guidance from M. B. ensuring homogeneous interview procedures. Medical students conducted the medical student focus groups and faculty interviews, and a recent divinity school graduate conducted the divinity student focus groups and faculty interviews. Focus groups were used for all students (seven total: two for divinity students and five for medical students), and one-on-one interviews were used for all faculty. Interviews ranged between 30 and 60 minutes and focus groups between 90 and 120 minutes in duration. All participants received a $25 gift card.

Table 1.

Semiscripted Protocol Developed by Expert, Interdisciplinary Panel for HMS and HDS Student Focus Groups, and Individual Harvard Medical and Harvard Divinity Faculty/Staff Interviews

One of the purposes of these focus groups is to develop an elective course that facilitates students’ reflection on psychological, moral, and spiritual experiences in caring for patients and that trains future professional caregivers in practices of self-care. What might be the specific components of such a course?

|

HMS = Harvard Medical School; HDS = Harvard Divinity School.

This question was only posed to HMS faculty and students, not to HDS participants.

Measures

Characteristics

Respondents completed a demographic questionnaire. Demographic information about race, gender, educational status, and religious affiliation was self-reported. Two items from the Brief Multidimensional Measurement of R/S regarding the extent to which the participants considered themselves R/S were included.38

Analytic Methodology

Qualitative Methodology

The protocol’s methodology39 included triangulated analysis, involvement of multidis-ciplinary perspectives (medicine, sociology, and theology), and reflexive narratives, maximizing the transferability of interview data. Interviews were audio taped, transcribed verbatim, and participants were deidentified. Transcriptions were independently coded line by line by C. M. and Z. D. E.- P. and then compiled into an initial coding scheme. Following principles of grounded theory,40 a final set of themes and subthemes inductively emerged as the interviews and focus groups progressed, through an iterative process of constant comparison. Transcripts were then reanalyzed (using NVivo 10; QSR International, Burlington, MA) by J. B., C. M., and Z. D. E.- P., each coding independently based on previously derived categories and themes. The inter-rater reliability score was high (average triangulated kappa score of 0.75).

Results

Sample characteristics for participants (n = 44) are presented in Table 2. Respondent qualitative analysis identified two primary themes for a medical school curriculum on R/S: curriculum format and curriculum content, each of which were then divided into various subthemes. Additional representative quotations are contained in Table 3.

Table 2.

Demographic Information of HMS Students (n = 25), HMS Faculty (n = 8), HDS Students (n = 8), HDS Faculty/Staff (n = 3) Interview Participants (Total n = 44)

| Demographic Characteristic | HMS, n = 33a

|

HDS, n = 11b

|

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||

| Female gender | 16 (49) | 9 (82) |

| Years in practice/servicec | NA | |

| Medical trainee | 20 (71) | |

| Medical school faculty, practicing 8–20 yrs | 5 (18) | |

| Medical school faculty, practicing more than 30 yrs | 3 (11) | |

| Interaction setting | ||

| Student focus groups | 25 (76) | 8 (73) |

| Faculty/staff interview | 8 (24) | 3 (27) |

| Medical specialty | 28d | NA |

| Internal medicine | 11 (39) | |

| Surgical specialtiese | 4 (14) | |

| Neurologyf | 3 (11) | |

| Psychiatry | 2 (7) | |

| Pediatrics/pediatric subspecialtiesg | 5 (18) | |

| Other subspecialtiesh | 3 (11) | |

| Do you consider yourself Hispanic or Latino? | ||

| Yes | 3 (10) | 0 (0) |

| No | 30 (91) | 11 (100) |

| What race or races do you consider yourself to be?i | ||

| White | 18 (56) | 10 (91) |

| Asian | 8 (25) | 1 (9) |

| Black or African American | 5 (16) | 1 (9) |

| Arab | 1 (3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Which of the following best indicates your religious affiliation? | ||

| Protestant | 16 (49) | 5 (46) |

| Roman Catholic | 5 (15) | 1 (9) |

| None | 5 (15) | 0 (0) |

| Jewish | 4 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Buddhist | 1 (3) | 2 (18) |

| Hindu | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Other religionj | 1 (3) | 3 (27) |

| If Jewish, would you say you are (n = 3) | ||

| Reform | 2 (67) | 0 (0) |

| Orthodox | 1 (33) | 0 (0) |

| If Christian, do you consider yourself evangelical? (n = 24) | ||

| No | 15 (63) | 5 (83) |

| Yes | 3 (13) | 1 (17) |

| How often do you attend religious services? | ||

| Several times a week | 1 (3) | 2 (18) |

| Every week | 7 (21) | 1 (9) |

| Nearly every week | 0 (0) | 7 (64) |

| Two to three times a month | 4 (12) | 1 (9) |

| About once a month | 4 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Several times a year | 7 (21) | 0 (0) |

| About once or twice a year | 3 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Less than once a year | 6 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Never | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| To what extent do you consider yourself a religious person?k | ||

| Very religious | 7 (21) | 2 (18) |

| Moderately religious | 6 (18) | 7 (64) |

| Slightly religious | 12 (36) | 1 (9) |

| Not religious at all | 8 (24) | 1 (9) |

| To what extent do you consider yourself a spiritual person?k | ||

| Very spiritual | 8 (24) | 8 (73) |

| Moderately spiritual | 14 (42) | 3 (27) |

| Slightly spiritual | 6 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Not spiritual at all | 5 (15) | 0 (0) |

HMS = Harvard Medical School; HDS = Harvard Divinity School; NA = not applicable.

When the totals do not equal 33 for each of the categories, it means that the respondent(s) did not provide a response for the particular question.

When the totals do not equal 11 for each of the categories, it means that the respondent(s) did not provide a response for the particular question.

This classification only applies to HMS participants. The medical trainee category includes students in the fourth year, fifth year MD/Master of Public Health, and Postgraduate year 5.

The five respondents who did not provide a medical specialty were all students.

Surgical specialties include surgery and orthopedics.

One respondent reported internal medicine and neurology. This response is recorded here in neurology.

Pediatric subspecialties include pediatric neurology, pediatric critical care, and pediatric anesthesiology.

Other subspecialities refer to anesthesia and/or critical care, dermatology, and radiation oncology.

One medical student did not identify her race, and one biracial divinity student selected two of the available options.

Other religion includes one Sabbatarian Christian and three unitarian universalists.

Self-reported religiousness and spirituality were measured using the validated National Institutes of Health-Fetzer Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality28 including, “To what extent do you consider yourself a religious person?” and “To what extent do you consider yourself a spiritual person?” Response options included very, moderately, slightly, or not at all.

Table 3.

Representative Quotes From Participant Focus Groups and Interviews, Divided by Theme and Subtheme

| Themes and Categories | Representative Quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Curriculum format | ||

| 1.A | Longitudinal or semester long? | In other words, it really needs to be throughout medical school. I mean, maybe at the end, there’s something that has a crescendo, but I think if you do nothing, put something, and then there’s internship, it’s not going to be powerful enough to withstand the huge tidal waves of internship, you know?—HMS faculty member (RI30) |

| 1.B | Required or elective? | So I think that in terms of a general entity that would involve spirituality or religion as part of the curriculum would need to be something that students can take as an elective, because they would then select themselves out to be people who say I have an interest in this or not.—HMS faculty member (AO07) |

| 1.C | Experiential or lecture based? | I think that my initial reaction is that, am I really going to learn anything? Is it just going to be a lot of stuff that’s just very obvious? Is it going to be a lot of PowerPoint lectures that are not going to help me in any way? So my inclination would be that like the course should be 100% practical, it should be very much very experiential.—HMS student (JR12) |

| Theme 2: Curriculum content | ||

| 2.A | Personal religious and spiritual growth | I think the first thing we’d need would have to be some kind of self-awareness exercise where people list a bunch of things that they feel they need to work on, need to get better at, and then trying to address these with either people who are professionals or people who they trust and respect or are more experienced, one at a time. I think it has to start with some kind of self-inspection exercise.—HMS faculty member (AO07) |

| 2.B | Professional integration of R/S values | Any course that’s going to talk about how do you engage someone in their spirituality, should have, I would think, some component of observing someone who’s really good at it.—HMS student (ML08) |

| 2.C | Addressing patient needs | I mean, I think the core of it should be engaging a patient in a spiritual discussion. Not necessarily you divulging your spiritual beliefs, but sort of being able to engage them and get a feel for what their belief system is like and how you can best go about respecting that and incorporating that into your medical care that you’re giving them.—HMS student (DF08) |

| 2.D. | Structural/institutional dynamics | I think there’s stunningly little interaction between medical students and nurses. I’m surprised even at this level how I hear disparaging remarks from classmates about nursing staff, and I think we have so little appreciation for what they do, and nurses are spending so much more time with patients than we are.—HMS student (KH10) |

| 2.E | Controversial social issues | Also, I would encourage the course to be controversial. I think back to what I said earlier about how I felt that the only real, agreed upon principle in the medical ethics base was autonomy and informed consent. If you really want meaningful reflection around being a caregiver and thinking about values and principles, give us an article by some prominent Catholic thinker about why abortion is wrong, and let us talk about it. Give us an article by someone from the American Enterprise Institute about why affirmative action is just terrible and destructive to our institutions, and let us talk about it.—HMS student (JG24) |

HMS = Harvard Medical School.

Theme 1. Curriculum Format

Longitudinal or Term Long?

One issue that was discussed in focus groups and interviews, as guided by the script of questions, was whether this curriculum should be offered longitudinally across all four years of medical school or contained within a term-long course. A few HMS and HDS students and faculty members felt that the purpose of the curriculum to encourage medical students in psychological, moral, and spiritual wellness could be accomplished within a single term of medical school, arguing that perhaps such a curriculum would be more useful once students had some clinical training in their third and fourth years and could reflect back on the ways in which they had changed. Most students and faculty agreed that a proposed curriculum on R/S would be more effective longitudinally, giving medical students an opportunity to self-reflect and check in as they evolve and change from first to fourth years. Students noted that even within the process of reflecting and sharing during the focus groups, they appreciated the ways in which they had changed over the course of their medical training. One medical student remarked,

We’ve all talked about the way that we’ve changed, the way we think spiritually, everything. So I think it would be neat to kind of follow through all four years.

Required or Elective?

Another debated topic in developing such a curriculum is whether it should be required training or an elective. Although requiring students to take the course would ensure the broadest reach in training future physicians to understand and integrate R/S in their practice, there was a great deal of hesitation among both medical students and faculty on making a religion-specific curriculum required. One HMS professor said,

To actually say that this is a mandatory course you need to sit through, I think would be difficult to substantiate, because some people would say, listen, I’m an Orthodox Jew, I don’t need to hear about Christian philosophy … or I don’t need to know about general principles, I already know it; or someone says, listen, I have no interest in this at all.

Several students echoed this sentiment, explicitly focusing on the particularities of the pluralistic ethos in a university setting. Although most HMS faculty and students expressed an awareness that leaving such a curriculum as an elective would result in a self-selecting population of participants, most deemed this an advantage as the students who chose to participate would be fully engaged with and open to the topic. Notably, one HDS professor did argue that the curriculum should be required because of the particular challenges that health care providers face in their daily work:

I think both doctors and chaplains have some challenges – that … if they were going to go into medicine or prepare themselves for ministry or chaplaincy –looking at religion and medicine actually should be required.

Experiential or Lecture Based?

The final discussion with regard to the format of a curriculum involved the methodology of how the topics of R/S, spiritual care, spiritual assessment, wellness, and others would be taught. The central issue was whether the curriculum should be more experiential or more lecture based. Most HMS and HDS faculty and students agreed that such a curriculum would be most beneficial if it was experiential, with several students independently agreeing that no one wants another PowerPoint. Because the medical students interviewed were third and fourth year students, most expressed a lack of interest in more lecture-based classes and a desire for more practical hands-on learning, as they had experienced during clerkships.

One HMS student said: “I think that might be important to just do a quick background, but I think that mainly, I would love to be part of a class that was experiential, whether it was shadowing the chaplain rather than having a PowerPoint lecture from someone from chaplaincy who tells you, ‘Here’s when you refer to us, and here are a couple stories from my career.”’ Some medical students recommended content that would require some lecture-based class time, suggesting that perhaps a combination of lecture and practice would be the ideal format.

Theme 2. Curriculum Content

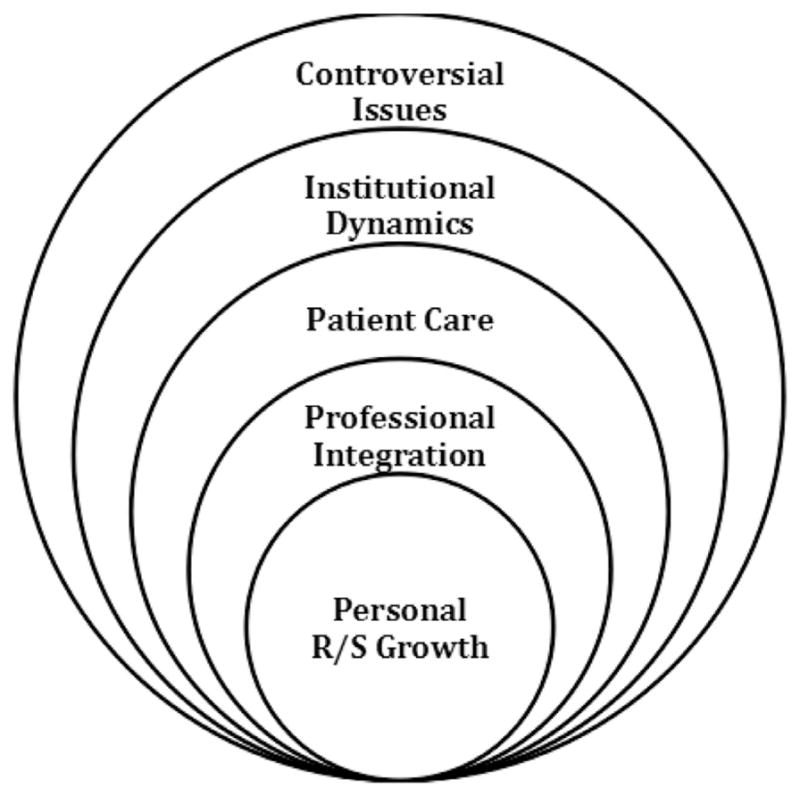

Five areas of content were identified as critical dimensions for a medical school curriculum on R/S. Figure 1 depicts respondent subthemes, thematically arranged according to multiple levels of learning and development, expanding outward from the individual level to the societal and/or global level.

Fig. 1.

Content of the course, explained in an exploratory diagram, moving outward in five levels. 1) The individual level focused on personal growth, including educational activities, such as writing a spiritual autobiography, self-care training, and shadowing a chaplain. 2) The level at which these values become professionally integrated, involving activities, such as interviews of other medical team members, self-reflection, and an understanding of team dynamics. 3) The patient care level, which involves gaining a deeper understanding the patient experience, learning the basics of spiritual care provision, and basic religious literacy. 4) The institutional and/or structural level, where the student will learn about the structure of the medical team, local religious communities, and social structures (health care and socioeconomic status). 5) The societal level, where students will discuss controversial issues dealing with religion and/or spirituality and medicine, providing multiple viewpoints of social issues (abortion, health care, religious views on medicine, etc.).

Personal R/S Growth

The individual level of development involved personal R/S growth, a lifelong process that can be facilitated through self-care instruction and self-reflective activities. Students suggested that the curriculum introduce and discuss various practices for healthy living and supporting data associated with these self-care practices. A specific area of interest was exercise, with other students suggesting the practice of meditation as a form of self-care. Most students agreed that some form of self-reflection and self-awareness is necessary for their future careers in clinical care. Students suggested different avenues for this process of reflection to occur, with students in one HMS focus group agreeing that there should be no written assignments. However, other students felt that writing thoughts, challenges, and motivations may facilitate reflection. Several students and staff members from HDS suggested the process of writing a spiritual autobiography—a reflection on one’s R/S background and development. One HDS student commented, “I would love it if health care providers had the opportunity to do the same work on their own spiritual autobiography and their spirituality that we get to do in divinity school.”

Professional Integration of R/S Values

Still focused on the individual level, but expanding outward toward professionalism, a second level of instruction in a curriculum would guide students in ways of integrating their R/S values into their professional lives. This was envisioned to occur through role model interactions and direction with successful self-care practices and thoughtful group discussion of how to integrate one’s R/S into practice. The concept of observing and interacting with both positive and negative role models was frequently mentioned by both students and faculty as a tool for learning professional integration of values. This echoed the call for experiential learning, by shadowing, speaking with, or working with a physician who is skilled at integrating self-care activities into his or her daily practice of medicine. The open discussion of barriers to the practice of self-care was mentioned by one HMS faculty member, who said:

So, you know, Albert Schweitzer once said ‘By example is not a way people learn behavior, it’s the only way’ so you know how you teach this: the faculty should take care of themselves, and then the students will, but we don’t.

Beyond self-care, students also desired a space to learn how to incorporate their own personal R/S beliefs into practice, with one HMS student noting:

I think the secondary focus should be how can you as a physician go about exercising your own spiritual beliefs within the constraints of the work place. And without compromising the patient-doctor relationship.

Finding ways of retaining and integrating their own personal R/S beliefs, although also respecting the R/S beliefs of patients, was an important dynamic that many students desired to master in their professional development.

Addressing Patient Needs

On an interpersonal level, students and faculty from both HMS and HDS were concerned with how medical professionals could best address patient needs, particularly those that involve R/S. Following the desired curriculum format of experiential learning, students suggested that hearing directly from patients about their experiences of and needs around receiving spiritual care would be helpful. One strategy for addressing this suggestion within a curriculum would be engaging with patients who openly and willingly share their R/S experiences with students. Related to understanding and attending to patient’s R/S needs, most HDS students and faculty recommended that medical students receive training in basic religious literacy for a variety of faith traditions. One divinity school student retold a story of a physician displaying lack of knowledge about Buddhism, noting, “I would love [the medical team] to be a bit more knowledgeable about world religions.” Notably, basic religious literacy was not a concern for most medical students but was mentioned in almost every divinity school interview or focus group.

Structural and/or Institutional Dynamics

At an institutional level, several medical students noted their lack of training and understanding regarding the dynamics of the medical team. Although medical students were taught the role of a physician, they felt less knowledgeable about the role of nurses, social workers, chaplains, and other health care professionals as part of the comprehensive care team. With regard to spiritual care, students suggested that if they had an opportunity to shadow chaplains, or even interact with them more regularly, there could be much greater collaboration on the medical team, understanding of the chaplain’s role, and potentially increased referrals that otherwise are not appropriately placed. One HMS student suggested:

Or maybe linked with one patient who requested a chaplain and who would be willing to have a student there with them. That would be really helpful too, to hear the patient’s story directly and then ask what they want out of that interaction and then watch it.

Controversial Social Issues

At a societal level, several medical students desired a safe environment to discuss controversial issues in medical care, especially as they relate to and are informed by R/S. Medical students suggested that this curriculum could provide a comfortable open space for dialogue and reflection on topics, which may be influenced by patients’ religious beliefs, such as abortion, regulations with the Affordable Care Act, patient autonomy, and the ethics of decision making in medical care. Students wanted the opportunity to hear both sides of an issue and then be provided a space to discuss and reflect on their understanding of it. One medical student commented, “Give us two real sides, and let us talk about it. I think that too often, these ideas around spirituality and meditation and reflection end up being very soft and noncontroversial, and as a result, unproductive.” However, medical and divinity students also expressed concern that the curriculum creates a safe and trusting environment, as one student described: “There has to be space for people to say, ‘Well, you know, I think this procedure is wrong,’ or, ‘I think this is not a choice you should be allowed to make,’ and I think that’s something this course could offer.”

Discussion

Despite calls to enhance R/S training in medical curricula, to our knowledge, this study represents the first qualitative examination of student and faculty perspectives in the U.S. regarding the optimal content and structure of such a curriculum. This study found that a medical school curriculum in R/S should include attention to issues of format and content, as described earlier.

The suggested format of an elective curriculum raises the important issue of self-selection. If such a curriculum is designed as an elective, registered students may already be predisposed to an interest in understanding R/S, when in fact it may be the students who are not interested who would most benefit from studying such material and incorporating it into their practice. The question remains that should such a curriculum meet the desires of students (as described in the results) or the needs of students? A survey of medical schools that offer training in spirituality and health was conducted by Koenig et al.27 in 2008 and found that although more than 80% of schools have some spirituality and health content in their curriculum, only 7% of schools have a dedicated course as a requirement. Although it could present a challenge both ideologically and logistically to require curricula on R/S at a medical school, this may be a significant way to improve competency in meeting national standards10,11 for physicians in addressing this particular set of patient needs.

One concern expressed about having a required course on R/S was that there is no single moral or spiritual tradition that fits a pluralistic student body at a secular medical school. Partially in response to this dynamic, the construct of spirituality is said to not only encompass religion but also expand beyond it, involving human meaning, purpose, and connectedness.17 Consequently, the focus on spirituality is believed to overcome issues raised by pluralism. Others have critiqued this view,41,42 and some have suggested an open pluralism in medical education, referring to the moral and spiritual training of medical students in partnership with particular moral communities of formation.15,16 This approach suggests that trainees need to critically examine and work out their R/S convictions pertaining to medicine in mentorship from other physicians and local moral communities rooted in a spiritual tradition that a trainee identifies or chooses (e.g., Buddhist, catholic, humanist, etc). This approach is skeptical that medical education alone can train students in how to provide spiritual care, facilitate personal R/S growth, or socialize trainees to resist the hidden curriculum.19 Instead, medical education can create curricula that partner with physician guilds able to teach and mentor trainees based within a particular set of spiritual beliefs and practices. Further research is needed to compare the efficacy of required curricula as opposed to elective curricula and the role that nonprofessional communities may hold.

This study also revealed several differences in feedback between divinity school students and medical school students, particularly around the issue of self-reflection. Divinity-chaplain trainees noted that they are given time to explore self-awareness throughout their training, including the process of writing spiritual autobiographies and reflection papers about their motivations and values. Students training in chaplaincy are also provided with strategies and mechanisms to process challenging experiences they encounter in patient care, including group processes, supervision, and spaces for reflection outside the hospital.43 In contrast, medical students frequently noted that they are permitted little space and time for processing amidst the unending demands and pressures of training. The unexamined emotions that physicians hold in the face of constant encounters with illness, loss, and grief can lead to distress, disengagement, depression, and burnout for physicians.44 A curriculum that could address this gap for medical students and allow them to examine some of those emotions more carefully could help prevent some of the risk for burnout that students face.45,46

As an exploratory study at one university based on chain referral, the findings are not intended to be generalizable and may have unintentionally excluded critical perspectives. Future research remains critical in developing and testing medical school curricula as they intersect with R/S.

In summary, this qualitative study engaging medical and divinity faculty and student perspectives provides key themes to guide the development of curricula addressing R/S within medical student training. Major themes include consideration of format, with frequent preference for longitudinal, elective, and experiential learning. The second major theme highlighted key content to be addressed: personal R/S growth, professional integration of R/S values, addressing patient needs, structural and/or institutional dynamics of the health care system, and controversial social issues. These findings suggest important format and content areas to be evaluated in future curricula addressing R/S in the practice of medicine.

Acknowledgments

Contributors: Harvard Medical School and Harvard Divinity School. Funders: The John Templeton Foundation. Prior presentations: None to report. The authors declare no associated conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Vallurupalli M, Lauderdale K, Balboni MJ, et al. The role of spirituality and religious coping in the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation therapy. J Support Oncol. 2012;10:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sloan RP. Blind faith: The unholy alliance of religion and medicine. 1. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Astrow AB, Wexler A, Texeira K, He MK, Sulmasy DP. Is failure to meet spiritual needs associated with cancer patients’ perceptions of quality of care and their satisfaction with care? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5753–5757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curlin FA, Lawrence RE, Odell S, et al. Religion, spirituality, and medicine: psychiatrists’ and other physicians’ differing observations, interpretations, and clinical approaches. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1825–1831. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daaleman TP, Nease DE., Jr Patient attitudes regarding physician inquiry into spiritual and religious issues. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:564–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King DE, Bushwick B. Beliefs and attitudes of hospital in-patients about faith healing and prayer. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehman JW, Ott BB, Short TH, Ciampa RC, Hansen-Flaschen J. Do patients want physicians to inquire about their spiritual or religious beliefs if they become gravely ill? Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1803–1806. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maugans TA, Wadland WC. Religion and family medicine: a survey of physicians and patients. J Fam Pract. 1991;32:210–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacLean CD, Susi B, Phifer N, et al. Patient preference for physician discussion and practice of spirituality. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:38–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NCP Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. [Accessed March 1, 2010];National Consensus Project. (2). 2009 Available at: http://ww.nationalconsensusproject.org/guideline.pdf.

- 11.The Joint Commission. PC.02.02.13. 3.7.0.0 ed.: Edition. [Accessed March 28, 2013];2011 Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/LTC_Core_PC.pdf.

- 12.Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:555–560. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Enzinger AC, et al. Nurse and physician barriers to spiritual care provision at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48:400–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Amobi A, et al. Why is spiritual care infrequent at the end of life? Spiritual care perceptions among patients, nurses, and physicians and the role of training. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:461–467. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinghorn WA. Medical education as moral formation: an Aristotelian account of medical professionalsim. Perspect Biol Med. 2010;53:87–105. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinghorn WA, McEvoy MD, Michel A, Balboni M. Professionalism in modern medicine: does the emperor have any clothes? Acad Med. 2007;82:40–45. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000249911.79915.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the consensus conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:885–904. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon JD, Daley BM, Curlin FA. The association between a sense of calling and physician well-being: a national study of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Acad Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s40596-016-0487-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balboni MJ, Bandini J, Mitchell C, et al. Religion, spirituality, and the hidden curriculum: medical student and faculty reflections. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allegra CJ, Hall R, Yothers G. Prevalence of burnout in the U.S. Oncology community: results of a 2003 survey. J Oncol Pract. 2005;1:140–147. doi: 10.1200/jop.2005.1.4.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asai M, Morita T, Akechi T, et al. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among physicians engaged in end-of-life care for cancer patients: a cross-sectional nationwide survey in Japan. Psychooncology. 2007;16:421–428. doi: 10.1002/pon.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Best M, Butow P, Olver I. Creating a safe space: a qualitative inquiry into the way doctors discuss spirituality. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515001236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kearney MK, Weininger RB, Vachon ML, Harrison RL, Mount BM. Self-care of physicians caring for patients at the end of life: “being connected… a key to my survival”. JAMA. 2009;301:1155–1164. E1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paal P, Helo Y, Frick E. Spiritual care training provided to healthcare professionals: a systematic review. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2015;69:19–30. doi: 10.1177/1542305015572955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchez-Reilly S, Morrison LJ, Carey E, et al. Caring for oneself to care for others: physicians and their self-care. J Support Oncol. 2013;11:75–81. doi: 10.12788/j.suponc.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neely D, Minford EJ. Current status of teaching on spirituality in UK medical schools. Med Educ. 2008;42:176–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koenig HG, Hooten EG, Lindsay-Calkins E, Meador KG. Spirituality in medical school curricula: findings from a national survey. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2010;40:391–398. doi: 10.2190/PM.40.4.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucchetti G, Lucchetti AL, Espinha DC, et al. Spirituality and health in the curricula of medical schools in Brazil. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:78. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucchetti G, Lucchetti AL, Puchalski CM. Spirituality in medical education: global reality? J Relig Health. 2012;51:3–19. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9557-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puchalski CM, Larson DB. Developing curricula in spirituality and medicine. Acad Med. 1998;73:970–974. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199809000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puchalski CM. Spirituality and medicine: curricula in medical education. J Cancer Educ. 2006;21:14–18. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2101_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anandarajah G, Mitchell M. A spirituality and medicine elective for senior medical students: 4 years’ experience, evaluation, and expansion to the family medicine residency. Fam Med. 2007;39:313–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Musick DW, Cheever TR, Quinlivan S, Nora LM. Spirituality in medicine: a comparison of medical students’ attitudes and clinical performance. Acad Psychiatry. 2003;27:67–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.27.2.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cobb M, Puchalski CM, Rumbold BD. Oxford textbook of spirituality in healthcare. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puchalski CM, Blatt B, Kogan M, Butler A. Spirituality and health: the development of a field. Acad Med. 2014;89:10–16. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fortin AH, Barnett KG. STUDENTJAMA. Medical school curricula in spirituality and medicine. JAMA. 2004;291:2883. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Group, Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working. Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research. Kalamazoo, MI: Fetzer Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358:483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curlin FA, Hall DE. Strangers or friends? A proposal for a new spirituality-in-medicine ethic. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:370–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balboni MJ, Puchalski CM, Peteet JR. The relationship between medicine, spirituality and religion: three models for integration. J Relig Health. 2014;53:1586–1598. doi: 10.1007/s10943-014-9901-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fitchett G, Altenbaumer ML, Atta OK, Stowman SL, Vlach K. Critically engaging “mutually engaged supervisory processes”: a proposed theory for CPE supervisory education. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2014;68:1–11. doi: 10.1177/154230501406800405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meier DE, Back AL, Morrison RS. The inner life of physicians and care of the seriously ill. JAMA. 2001;286:3007–3014. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wachholtz A, Rogoff M. The relationship between spirituality and burnout among medical students. J Contemp Med Educ. 2013;1:83–91. doi: 10.5455/jcme.20130104060612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doolittle BR, Windish DM, Seelig CB. Burnout, coping, and spirituality among internal medicine resident physicians. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:257–261. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00136.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]