Abstract

Background

Residency programs are expected to educate residents in quality improvement (QI). Effective assessments are needed to ensure residents gain QI knowledge and skills. Limitations of current tools include poor interrater reliability and requirement for scorer training.

Objective

To provide evidence for the validity of the Assessment of Quality Improvement Knowledge and Skills (AQIKS), which is a new tool that provides a summative assessment of pediatrics residents' ability to recall QI concepts and apply them to a clinical scenario.

Methods

We conducted a quasi-experimental study to measure the AQIKS performance in 2 groups of pediatrics residents: postgraduate year (PGY) 2 residents who participated in a 1-year longitudinal QI curriculum, and a concurrent control group of PGY-1 residents who received no formal QI training. The curriculum included 20 hours of didactics and participation in a resident-led QI project. Three faculty members with clinical QI experience, who were not involved in the curriculum and received no additional training, scored the AQIKS.

Results

Complete data were obtained for 30 of 37 residents (81%) in the intervention group, and 36 of 40 residents (90%) in the control group. After completing a QI curriculum, the intervention group's mean score was 40% higher than at baseline (P < .001), while the control group showed no improvement (P = .29). Interrater reliability was substantial (κ = 0.74).

Conclusions

The AQIKS detects an increase in QI knowledge and skills among pediatrics residents who participated in a QI curriculum, with better interrater reliability than currently available assessment tools.

What was known and gap

Quality improvement (QI) skills are important for physicians, and their development is hampered by a dearth of reliable, easy to use, QI assessment tools.

What is new

The Assessment of Quality Improvement Knowledge and Skills (AQIKS) assesses residents' understanding and application of QI concepts.

Limitations

Single site, single specialty study reduces generalizability.

Bottom line

The AQIKS detected increases in QI knowledge and skills in pediatrics residents, with improved interrater reliability over existing tools.

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine recommends that residents receive training in patient safety and quality,1 and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has established expectations for quality improvement (QI) training in graduate medical education.2–4 Maintenance of certification requirements for practicing physicians includes ongoing development and assessment of QI skills.5 With these national efforts, reliable and useful tools for assessing trainees' QI skills and knowledge are needed.

Drawbacks of the existing approaches to QI assessment include reliance on self-reports,6,7 requirement for faculty training or expertise in QI,8,9 evaluation of only a limited subset of skills necessary to engage in QI,10,11 and limited validity evidence of instruments.12–15 Establishing strategies to measure QI skills and knowledge can help ensure that residency training programs prepare physicians to participate in and lead QI efforts. In pursuit of this goal, experts have called for more robust assessment strategies for QI curricula.16

The objective of this study was to provide validity evidence for the Assessment of Quality Improvement Knowledge and Skills (AQIKS), a tool that generates a summative assessment of residents' ability to recall QI concepts and apply them to a clinical scenario. We describe the AQIKS and its performance in assessing pediatrics trainees scored by junior faculty with limited experience in QI. We assessed the instrument's validity evidence in 3 domains: (1) content validity; (2) internal structure, measured by interrater reliability; and (3) impact of learner participation in a formal QI curriculum. AQIKS cases, questions, and scoring rubric are available at MedEdPORTAL.17

Methods

Instrument Development

The AQIKS cases and questions address the Institute of Medicine quality and safety aims—care should be timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient centered (STEEEP).1 The AQIKS was developed by a multidisciplinary team, including a survey methodologist and 2 pediatrics attending physicians with roles in clinical QI and education.

Glissmeyer et al15 previously described the development of pediatrics cases adapted from the QI Knowledge Assessment Tool (QIKAT). However, use of the QIKAT questions with pediatrics cases resulted in low interrater reliability, and did not discriminate well between learners with greater and lower QI knowledge.15 We designed a new question set that, together with cases developed by Glissmeyer et al,15 comprises the AQIKS. Using the “Model for Improvement” framework18 as a guide, we developed 9 questions, with each testing a unique concept or a skill central to the application of the model.18 Four questions are generally applicable to QI methods: testing learner conceptual understanding of Institute of Medicine quality aims (No. 1), aim statements (No. 2), key stakeholders (No. 6), and interpretation of a run chart (No. 9). Five questions are specific to the proposed QI intervention: test learner ability to generate a driver diagram (No. 3), describe a family of measures (No. 4), design a QI intervention (No. 5), test a QI intervention (No. 7), and develop a run chart (No. 8). All questions were pilot tested with 10 pediatrics residents.

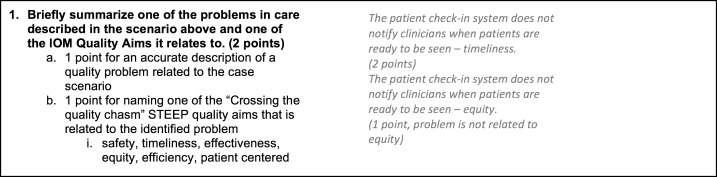

Once the 9 AQIKS questions were selected, we developed a scoring rubric. The point total assigned to each question reflects the complexity of the concept or skill tested. The figure displays a sample question, scoring instructions, and sample responses with appropriate point assignments provided to scorers.

Figure.

Sample AQIKS Question, Scoring Rubric, and Response

Abbreviations: AQIKS, Assessment of Quality Improvement Knowledge and Skills; IOM, Institute of Medicine.

The AQIKS cases, questions, and scoring rubric were reviewed by a panel of 5 national QI and education experts (separate from the study team), who provided feedback to refine the instrument. The panel deemed that the final AQIKS instrument tests QI skills and knowledge used in the Model for Improvement Framework.

Instrument Testing

We conducted a quasi-experimental study using precurriculum and postcurriculum assessment of a QI curriculum taught in a large, urban, pediatrics residency program with clinical sites at a safety-net hospital and a quaternary hospital. The intervention group included 37 postgraduate year (PGY) 2 pediatrics residents participating in a longitudinal QI curriculum, and the concurrent control group included 40 PGY-1 pediatrics residents not exposed to a QI curriculum. Residents who participated in pilot testing were not included. Each participant completed the questions for 2 randomly selected cases of the 6 pediatrics case scenarios, before delivery of a QI curriculum to the intervention group, and 2 different randomly selected cases after delivery of the curriculum. No participant received any case more than once.

Three raters from different institutions and specialties (neonatology, infectious diseases, and general pediatrics) scored responses to the AQIKS. Raters were junior faculty members with 2 to 5 years of experience in clinical QI, who were not involved in delivering the QI curriculum, design of the AQIKS, or design of the study. Raters were instructed to score learners' responses to all 9 questions for each case according to the AQIKS scoring rubric. Raters received no additional training or scoring instructions, and were blinded to intervention or control and preintervention or postintervention status.

QI Curriculum

Residents in the intervention group participated in a 12-month longitudinal QI curriculum based on the Model for Improvement,18 including 20 hours of didactics and participation in a faculty-mentored group project. Over the academic year, each resident had approximately 20 hours of protected time away from clinical duties to work on a QI project with a group of 5 to 6 other residents. Projects included developing an electronic tablet–based asthma education module, improving emergency department handoff procedures, and decreasing outpatient clinic patient wait times. One group presented results from a project they conceptualized during this curriculum at a national conference,19 and another group received external grant support to expand the QI effort piloted during the curriculum.

The Institutional Review Board of Boston Children's Hospital approved this study and granted a waiver of informed consent.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses included an analysis of internal structure, measured by interrater reliability in scoring and analyses of individual questions, and an analysis of overall test performance, including an analysis of the influence of completing a QI curriculum on AQIKS score over time.

Cohen's kappa measures interrater reliability, but is known to show paradoxically low kappa values if the marginal score distributions of raters are unbalanced.20 We measured interrater reliability using Brennan-Prediger's kappa, which is less influenced by unbalanced score distributions.21 The cutoff for acceptable interrater reliability was set at κ = 0.21, denoting at minimum “fair” interrater reliability.22,23

We used summary statistics to describe individual question performance among subjects who participated in a QI curriculum, compared to subjects who had not participated in a QI curriculum. We also used repeated measures linear mixed models to assess the efficacy of the intervention, for each of the 9 questions separately, and for the summary scores of the cases using the arithmetic mean of the scores of the 3 raters. We chose this method because of its flexibility to include a fixed effect to account for repeated measures within 1 group of trainees (preintervention versus postintervention assessment), as well as a fixed effect for membership in 1 of 2 groups (intervention versus control group). In addition, the models allowed for 2 random effects, 1 associated with the intercept for each subject and 1 with the intercept for the intervention. The covariance structure of the random effects was assumed to be independent. We calculated interitem correlations using Spearman rank correlation coefficients, with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple testing.

All analyses were performed using Stata version 12.1 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX). For all tests, P ≤ .05 was considered significant.

Results

In total, 30 of 37 residents (81%) in the intervention group and 36 of 40 (90%) in the control group completed the AQIKS at baseline and after the curriculum was delivered to the intervention group. The other residents were excluded because they did not complete the AQIKS either at baseline or at follow-up. All residents in the intervention group completed all required didactic elements of the QI curriculum and participated in a group QI effort.

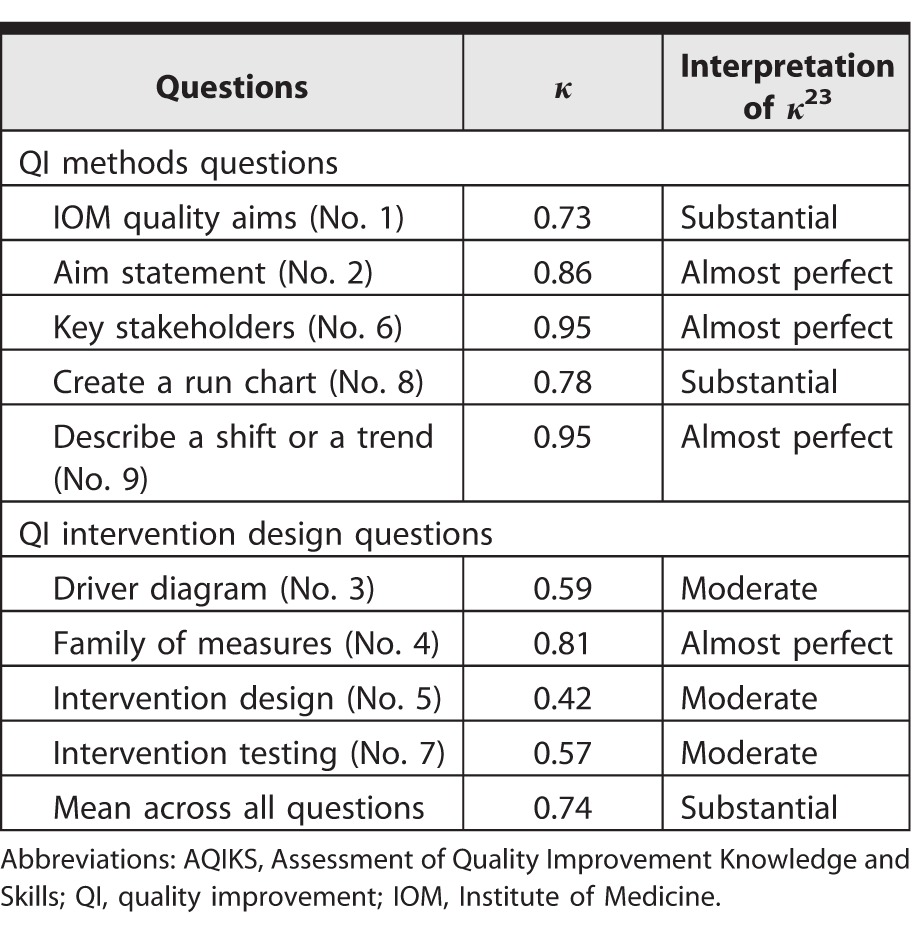

Internal Structure: Interrater Reliability

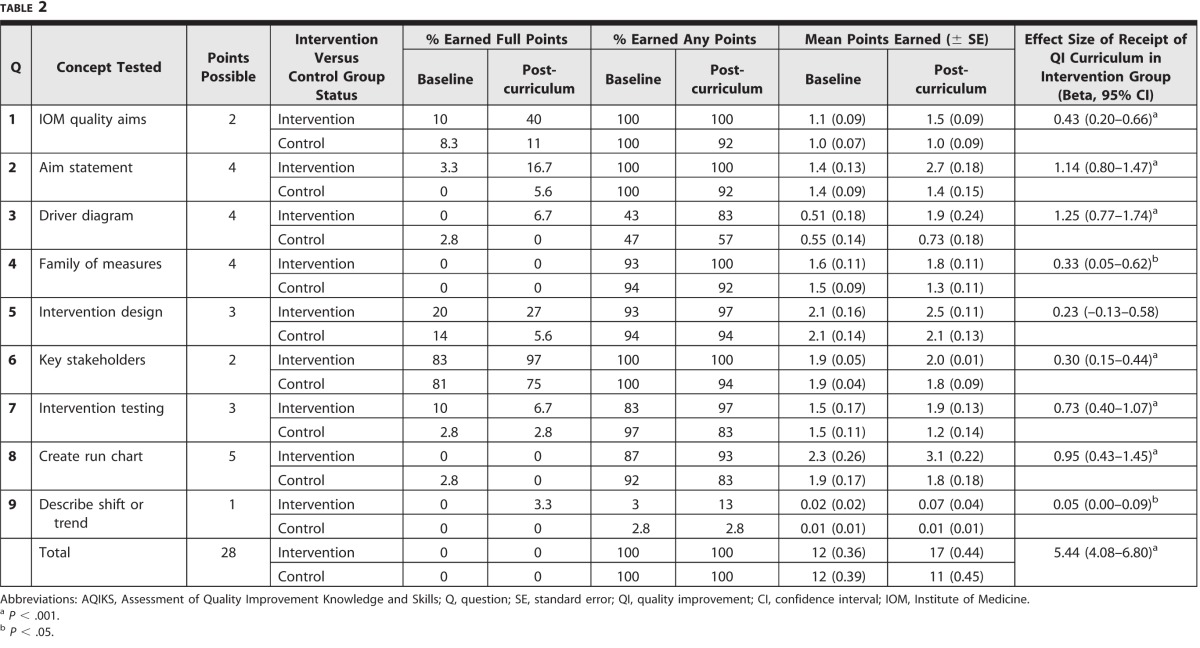

Table 1 displays Brennan-Prediger's kappa values for interrater reliability of 3 independent raters for each question and the overall AQIKS score, a summation of individual point totals on each question. Interrater reliability was moderate or better for each question. For the overall AQIKS score, interrater reliability was substantial (κ = 0.74).

Table 1.

Interrater Reliability Across 3 Raters for Each AQIKS Question and Overall AQIKS Score

Individual Question and Overall Test Performance

Question performance is described in table 2. Few residents earned full points on any individual question. The intervention group had significantly higher scores after participating in the QI curriculum, both for the total score for a case (P < .001) and 8 of 9 questions (P value range from P < .001 to P = .046). Spearman rank correlation coefficients were low (range 0.009–0.37), suggesting that questions address different knowledge areas.

Table 2.

Comparison of AQIKS Question Performance for Intervention and Control Groups at Baseline and Postcurriculum Completion

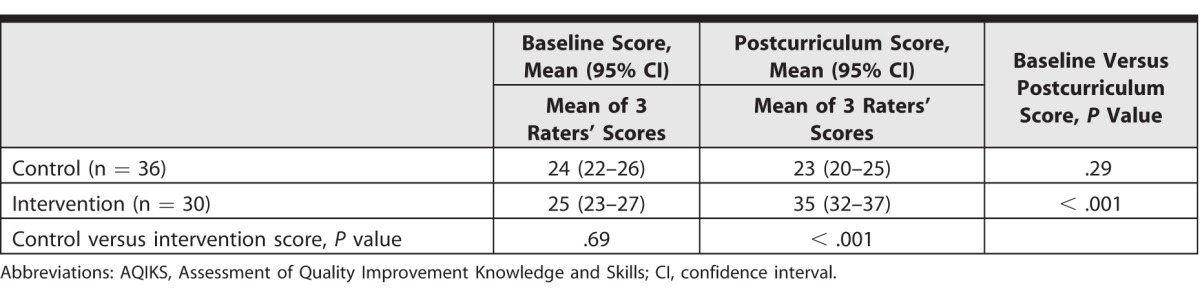

Relation to QI Curriculum Completion

Table 3 presents a comparison of baseline and postcurriculum mean AQIKS scores with 95% confidence intervals. There was no significant difference in baseline mean AQIKS scores between the intervention and control groups. The mean score of the intervention group increased by 42% after participating in the QI curriculum (P < .001). The control group had no difference in baseline and follow-up scores (P = .29).

Table 3.

Comparison of Baseline and Postcurriculum Mean AQIKS Score for Intervention and Control Groups

Discussion

We found evidence for validity of the content and internal structure of the AQIKS, and evidence that AQIKS scores were higher in learners who had participated in a QI curriculum.

The AQIKS has several advantages compared to QI assessment tools currently in use. First, it tests ability to design a hypothetical QI intervention, drawing on skills and knowledge across multiple QI domains. This assessment strategy balances the need for an assessment to be rapidly administered in a training environment with the need for thorough assessment of skills expected after a learner leaves the training environment. Second, it performs well when scored by junior faculty raters with fewer than 5 years clinical QI experience, who have completed no training related to administering or scoring the assessment. Ease of administration without requirement for scorer training may facilitate use of the assessment tool in training programs where lack of faculty expertise is a barrier to QI education.24

Limitations of this study include that findings from this single specialty, single center study may not be generalizable to other groups of learners or other specialties. An additional limitation common to many written assessments of applied skills is that performance on assessment tools alone does not offer a comprehensive assessment of the outcomes of an education program. For QI education programs, other important outcomes include participation in QI initiatives after graduation and production of scholarly activity in QI. Areas for further study include application of the AQIKS questions and scoring rubric to cases relevant to other clinical disciplines (eg, QIKAT-R11 cases) and generalizability studies with different populations of learners and scorers. A larger, fully crossed, experimental study, where all cases are administered to each subject and rated by all raters, would facilitate the use of generalizability theory to evaluate the reliability of the AQIKS.

Conclusion

The AQIKS is a promising new tool with good discriminatory capacity and good interrater reliability. Its advantages include open-ended questions, adaptability to different clinical scenarios, and an assessment of a learner's ability to design a hypothetical clinical QI intervention as a proxy for real-world QI activities.

References

- 1. The National Academies Press; Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century ; Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Clinical Learning Environment Review. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Initiatives/Clinical-Learning-Environment-Review-CLER. Accessed October 27, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weiss KB, Wagner R, Nasca TJ. . Development, testing, and implementation of the ACGME Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program. J Grad Med Educ. 2012; 4 3: 396– 398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, et al. The next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366 11: 1051– 1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Board of Medical Specialties. Based on core competencies. http://www.abms.org/maintenance_of_certification/MOC_competencies.aspx. Accessed October 27, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Canal DF, Torbeck L, Djuricich AM. . Practice-based learning and improvement: a curriculum in continuous quality improvement for surgery residents. Arch Surg. 2007; 142 5: 479– 482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peters AS, Kimura J, Ladden MD, et al. A self-instructional model to teach systems-based practice and practice-based learning and improvement. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23 7: 931– 936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tomolo AM, Lawrence RH, Watts B, et al. Pilot study evaluating a practice-based learning and improvement curriculum focusing on the development of system-level quality improvement skills. J Grad Med Educ. 2011; 3 1: 49– 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ogrinc G, Ercolano E, Cohen ES, et al. Educational system factors that engage resident physicians in an integrated quality improvement curriculum at a VA hospital: a realist evaluation. Acad Med. 2014; 89 10: 1380– 1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morrison L, Headrick L, Ogrinc G, et al. The quality improvement knowledge application tool: an instrument to assess knowledge application in practice-based learning and improvement. Paper presented at: Society of General Internal Medicine 26th Annual Meeting; 2003; Vancouver, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Singh MK, Ogrinc G, Cox KR, et al. The Quality Improvement Knowledge Application Tool Revised (QIKAT-R). Acad Med. 2014; 89 10: 1386– 1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ogrinc G, Headrick LA, Morrison LJ, et al. Teaching and assessing resident competence in practice-based learning and improvement. J Gen Intern Med. 2004; 19(5, pt 2):496–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lawrence RH, Tomolo AM. . Development and preliminary evaluation of a practice-based learning and improvement tool for assessing resident competence and guiding curriculum development. J Grad Med Educ. 2011; 3 1: 41– 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vinci LM, Oyler J, Johnson JK, et al. Effect of a quality improvement curriculum on resident knowledge and skills in improvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010; 19 4: 351– 354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Glissmeyer EW, Ziniel SI, Moses J. . Use of the quality improvement (QI) knowledge application tool in assessing pediatric resident QI education. J Grad Med Educ. 2014; 6 2: 284– 291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wong BM, Levinson W, Shojania KG. . Quality improvement in medical education: current state and future directions. Med Educ. 2012; 46 1: 107– 119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doupnik S, Ziniel S, Glissmeyer E, et al. The Assessment of Quality Improvement Knowledge and Skills (AQIKS). MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2015;11:10255. https://www.mededportal.org/publication/10255. Accessed October 27, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Langley GJ, Moen R, Nolan KM, et al. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. New York, NY: Jossey-Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zwemer EK, Moulton E, Rowe EG, et al. Asthma discharge contract: improving the transition to outpatient care for patients hospitalized with asthma. Poster presented at: American Pediatric Society/Society for Pediatric Research Meeting, May 4, 2014. Vancouver, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cicchetti DV, Feinstein AR. . High agreement but low kappa: II, resolving the paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990; 43 6: 551– 558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brennan RL, Prediger DJ. . Coefficient kappa: some uses, misuses, and alternatives. Educ Psychol Meas. 1981; 41 3: 687– 699. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Landis JR, Koch GG. . The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977; 33 1: 159– 174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Viera AJ, Garrett JM. . Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005; 37 5: 360– 363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wong BM, Etchells EE, Kuper A, et al. Teaching quality improvement and patient safety to trainees: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2010; 85 9: 1425– 1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]