Abstract

High rates of exposure to violence and other adversities among Latino/a youth contributes to health disparities. The current paper addresses the ways in which community-based participatory research (CBPR) and human centered design (HCD) can help to engage communities in dialogue and action. We present a project exemplifying how community forums, with researchers, practitioners, and key stakeholders, including youth and parents, integrated HCD strategies with a CBPR approach. Given the potential for power inequities between these groups, CBPR+HCD acted as a catalyst for reciprocal dialogue and generated potential opportunity areas for health promotion and change. Future directions are described.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, human centered design, Latino/a, violence, health disparities

Latinos/as are the largest and fastest growing minority group in the United States,1 a fact that highlights the importance of understanding and addressing the unique health concerns facing this population. Exposure to violence represents a significant health disparity, as Latino/a youth and adolescents are three times more likely to witness violence (community or domestic) compared to non-Latino/as.2 Furthermore, violence exposure has disruptive effects on both physical and mental health.3

Nonetheless, Latinos/as in the United States continue to receive low quality health care, facing numerous barriers to accessing timely and effective services.4 Research suggests that this problem may be due to a variety of factors across systemic, community, provider, and patient levels.5 Cultural competence, which refers to the ability to “transform knowledge and cultural awareness into health and psychosocial interventions that support and sustain healthy client-system functioning within appropriate cultural contexts,”6(pp. 261) is often inadequately addressed.

Ethnic minority consumers and marginalized communities are rarely included at the research table when evaluating healthcare needs, designing prevention and intervention programs, and assessing barriers and facilitators of care.7 One reason may be that traditional research approaches can unintentionally silence, rather than foster, individual participants’ voices.8 Consequently, researchers lose the opportunity to capitalize on the unique contributions, experiences, perspectives, and knowledge that community members can provide, informing the development of culturally competent, effective community intervention and prevention efforts.9 Numerous subgroups of Latinos/as exist, pointing to the importance of including all voices at the table to incorporate within group diversity.5

One alternative is to use a participatory approach and equitably include community members in the efforts. Community based participatory research (CBPR) is a philosophical framework that has been cited for its innovative methods of incorporating the voices of a community into research, particularly around health disparities.5,8,10 Rooted in philosophical approaches described by Freire,11 the target population engages in a process of dialogue, reflection, and action, creating a continuous feedback loop, to reduce health disparities and increase equity. CBPR calls for a collaborative approach where academic researchers and members of the community under study strive to have an equal voice in all aspects of the research, including the research questions, study design, data collection, and analysis.10 Although CBPR is becoming increasingly popular, it is still in its infancy compared to traditional research perspectives.12 Therefore, the concept of CBPR may not be as widely understood by researchers. Providing specific rationales, strategies, and procedures utilized in CBPR health disparities work will help to guide and refine this growing field. It is particularly useful to take a CBPR approach with ethnic minority and other vulnerable popualtions because, at its core, CBPR aims to increase levels of community trust, engagement and empowerment.5 By incorporating the knowledge of community members, CBPR can improve the likelihood that health disparities are addressed in culturally meaningful and effective ways.10

Like CBPR, human-centered design (HCD) is a creative problem-solving framework based on the principle that “people who face those problems every day are the ones who hold the key to their answer.”13(pp. 9) HCD emerged from fields such as ergonomics, computer science, and artificial intelligence.14 However, more recently some researchers have begun to use both HCD and CBPR simultaneously to address health disparities. For example, Durand, Alam, Grande, and Elwyn15 used HCD in conjunction with CBPR to design a pictorial encounter decision aid for women of low socioeconomic status diagnosed with early stage breast cancer. Their goal was to address the disparities that exist in decision-making, treatment, and outcomes for this population.15 Using HCD approaches can include many overlapping methods that align with CBPR, including interviews with community members and emphasizing their importance in building empathy for the target population.13 One feature of HCD that is particularly useful in combination with CBPR is its focus on how to generate creative and innovative solutions to community or “human” problems. For example, IDEO, a global design firm specializing in HCD has a free toolkit available with many specific strategies for quickly and effectively engaging communities in problem solving and generating solutions.13

The Current Study

Understanding the main mechanisms and social determinants of health disparities related to violence among Latino/a youth is paramount to better serving this population; it is especially important for working to interrupt and prevent the cyclical nature of violence and its sequelae. The current study integrated CBPR and HCD (CBPR+HCD) in order to to understand and address health disparities related to violence among Latino/a youth. In addition to a focus on the prevention of negative outcomes, the project also investigated how to best promote positive developmental trajectories for youth, including supporting resilience and healthy developmental pathways, increasing assets, and strengthening protective factors that could moderate the potential negative impact of exposure to stressors.16 Proyecto HÉROES (Project HEROES; the acronym spells out in Spanish: Honor, Educación, Respeto, Oportunidad, Esperanza, y Soluciones), is a CBPR partnership bringing together a transdisciplinary group of researchers, practitioners, and key stakeholders in order to increase knowledge and cultural competence regarding the social determinants of health disparities on Latino/a youth, family, and community health and mental health. CBPR+HCD invited full participation of all key stakeholders from a diverse range of developmental, educational, socio-economic, linguistic and cultural backgrounds to generate creative ideas, problem-solving and lead to innovative solutions.

Method

Participants

173 adults and 21 youth (under the age of 18) participated in one of three community forums on Latino/a youth that were free and open to the public. The first community forum consisted of 70 adults and 11 youth (Females N = 60; 86%), the second forum included 63 adults and 5 youth (Females N = 32; 51%), and 40 adults and 5 youth participants (Females N = 34; 85%) participated in the third forum. The first two forums took place on Saturdays and served lunch, and the last forum took place on a weekday evening and included dinner. All forums took approximately three hours, provided free childcare, and used simultaneous, two-way (English and Spanish) interpretation17–18 using multiple listener technology19 with an interpreter and headphones available for all participants.

Participatory Co-Design of Community Forums

At the outset of the project, a community advisory board (CAB) was formed. The CAB participated in the content, structure, and methods for all aspects of the research. The CAB included 24 key stakeholders, including representatives from community organizations serving Latino/a youth (i.e., school district, afterschool programs, religious organizations, mental health), leaders from key community sectors (i.e., city council, police department), interdisciplinary researchers (i.e., psychology, education, sociology), parents, and Latino/a youth themselves. For the community forums, the CAB helped to determine the titles, advertising, content (ie. semi-structured questions to facilitate dialogue), and activities.10 The CAB also played a critical role in identifying speakers for the community forums, resource tables, and staffing of the events. Youth CAB members helped to plan the community forums, and also, helped identify relevant youth speakers for the forums. Latino/a youth presented their photographs (from a photovoice project that was facilitated by Proyecto HÉROES20), poetry, and personal experiences. Community organizations also provided resource tables for families, including information about mental health services, social support networks, and safety and security resources. Feedback from each forum informed the collaborative design process and content of the forums that followed.

Community-Driven Discovery

Both CBPR and HCD highlight the importance of creating opportunities for community members to lead research efforts.10,13 There are a number of potential benefits to putting community researchers at the helm of data collection efforts, such as increasing comfort and honesty among participants who might be able to better express their perspectives to a respected peer. Community researchers may also have insights from their own first-hand knowledge; their contributions can be useful in gathering relevant information more quickly, or in more nuanced and effective ways. Fifty-five community leaders and volunteers helped facilitate the three forums (N = 25, N = 18, and N = 12, respectively). All facilitators completed a two-hour training focused on handling off-topic conversations, managing time, engaging community participants, and techniques to generate dialogue and brain-storming.

Community Forum Recruitment and Advertising

The community forums took place in three locations in low-income and predominantly Latino/a neighborhoods, within a larger context of extreme income disparities and racial and socio-economic stratification. Flyers about the community forums were posted in the community, handed out directly to residents by walking the neighborhoods, distributed at local public schools, and advertised at youth-serving agencies. CAB youth, and a youth group for 20 youth living in local low-income housing projects, provided recommendations about location of the forums, methods for advertising, and activities to help draw youth and families to participate.

The aim of the community forums was to address health disparities related to violence and other stressors affecting the Latino/a community. Nonetheless, CAB members suggested that starting with broader topics would provide greater flexilibity for participants to communicate their true needs, and that some families may be reluctant to attend a forum that only focused on violence. Thus, two forums launched conversations around school experiences and safety, while one forum directly mentioned violence with a focus on solutions. Ultimately, participates raised issues about violence and related adversities. including bullying and discrimination, at all forums. The first community forum, “Nuestras Escuelas: Voces de la Comunidad” (“Our Schools: Voices of the Community”), included speakers who highlighted school experiences (i.e., school climate, bullying, belonging, support) for Latino/a youth. The second community forum, “Esta es nuestra communidad: Estos son nuestros hijos: Let’s find solutions together to increase safety and reduce trauma and violence,” underscored innovative solution-building to address violence and trauma exposure among Latino/a youth. The third forum, “Apoyando a Nuestros Ninos y Jovenes Latinos: Como Proveer Seguridad y Fortalecer su Desarrollo” (“Safe Lives and Healthy Futures for Latino Youth and Families”) emphasized sense of safety, resilience, and youth well-being.

Anchoring the Dialogue through Community Voices

A number of strategies were utilized in order to engage participants in reciprocal dialogues about solutions about violence exposure, health disparities, and youth thriving. First, the CAB strategically planned for key speakers who represented a range of constituencies, including those with both professional and personal knowledge, leaders in the community, community members whose voices might otherwise go unheard, and youth themselves. In sum, the speakers included five high school students, four undergraduates who read poetry from Latino youth in juvenile detention, two parents, one community outreach worker from the school, one Promotora de Salud (community health worker), three school officials (i.e., guidance counselor, School Board representative, and Director of Pupil Services), and two elected officials (i.e., city council, and school board member). Each forum had a keynote speaker who was a youth-serving professional who was bilingual and bicultural, and had personally faced challenges during childhood such as poverty, immigration, family and community violence, racial profiling, and discrimination.

Youth voices were also captured through multi-media displays. Participants viewed a bilingual video with photographs and narratives from twenty-four Latino/a high school students who participated in the Proyecto HÉROES photovoice program.20 The youths’ photographs were also exhibited at forums.

Engaging Community Members in Idea Generation

Two main strategies were used to engage community members in a co-learning process during the community forums, (1) small group reciprocal dialogue and (2) written responses to prompts. In small groups, participants were divided into eight groups comprised of approximately three youth and five to eleven adults. Each group gathered to have thirty minute ‘circulos’ (circles) that were led in either Spanish or English by two facilitators. There was one bilingual, bicultural Latina per group that served as a scribe. Facilitators used semi-structured questions to evoke dialogue focused on family stressors, community problems, challenges to addressing family needs, recommendations for change in family, school, and community settings, and action steps. Groups also generated written information that was collected, including brainstorming possible solutions on a large-scale post-it notes to share with the larger forum, and with the research team.

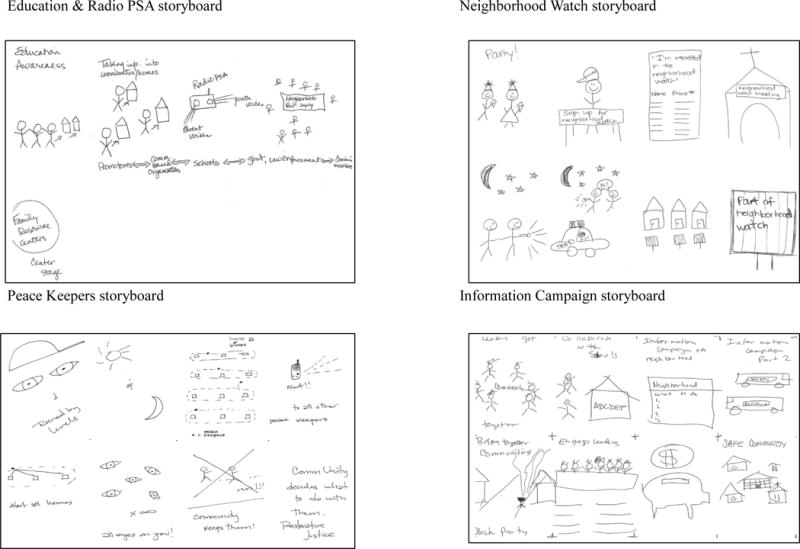

Drawing from HCD, we used storyboards as a method to foster creativity and sidea generation.15 The storyboard method can be a relatively time-efficient and effective way to brainstrm ideas and develop a visual representation of possible solutions to a problem. The procedures are simple and don’t rely solely on verbal skills. These factors are particularly useful for a randomly assembled group whose members don’t have prior relationships, have varying educational and professional levels, different languages, and include a wide range of ages. Table 1 describes our storyboard procedures. Because we had already conducted the photovoice project22, we were able to use a prompt taken directly from a youth narrative in order to initiate relevant and meaningful dialogue. Participants were invited to add complexity to the scenario by drawing on their understanding of the broader issues youth face in the community. Facilitators guided the dialogue from problem-focused to solution-focused and participants brainstormed a list of potential solutions. Ideas were built upon by adding one new aspect and then another. The final step was for participants to help visualize a solution that appealed to them by creating an individual storyboard, visually depicting the features of the solution, and generating a sequence of pictures to form the storyboard of how the solution would work (i.e., using cartoon boxes). Figure 1 provides a few storyboard examples.

Table 1.

Human Centered Design: Storyboard Activity

| Step 1 | Read scenario of issue and encourage participants to add complexity to the scenario with similar issues faced (i.e., what other stressors/challenges, how do these experiences affect the individual?). |

| Step 2 | Generate as many ideas of solutions to the issues raised in the scenario as possible. Write the solutions for the group to see and build off of. |

| Step 3 | Pair participants and encourage each to add to one of the ideas they find compelling. Have participants elaborate on that idea by adding a feature and then another. |

| Step 4 | Participants create a storyboard of the solution by creating a visual step-by-step depiction (i.e., images and words displayed in a panel by panel sequence). |

Figure 1.

Storyboard Examples

To engage participants during the community forums a non-verbal approach drawn from an HCD activity called “Conversation Starters” was utilized.13 The goal of this approach is to foster creativity, elicit reactions, and initiate dialogue from participants. The conversation starters we used were youth photovoice images paired with thought-provoking questions which were posted around the room and allowed participants to provide written responses. Examples of these questions included: (1) What do these pictures say about our community? (2) What vision for change do these pictures suggest? (3) What memories do these pictures bring up for you? And (4) What do you see in these pictures?

Finally, a painting of a tree image on a large piece of plywood allowed participants to add their own ideas for peace in the community on individual heart-shaped pieces of paper that were added to the tree as ‘leaves.’ One goal of this free-write activity was to provide an avenue for expression for participants who were less extroverted or preferred anonymity; in addition, it created a visual depiction of participants’ perspectives on peace in the community, took a value stance by highlighting the positive (peace) over the negative (violence), and elicited ideas for change. Participants could write in Spanish or English, depending on their own preference.

Strategies for Building Community and Reducing Barriers

It is critical to identify potential barriers for attendance at community forums, as well as make forums accessible, appealing, and meaningful for potential participants. One strategy is to focus on how best to foster a sense of community and appreciation for the participants’ cultural backgrounds. As mentioned, simultaneous, bidirectional interpretation was provided to all participants. Each of our community forums included typical Latino/a fare served for lunch or dinner, depending on the time of the forum. Parents could bring children and be assured that their family would be served a meal, and that children’s activities were also included during the forum, so that parents did not need to obtain childcare. Additionally, Latino/a music and performances by local youth dance troupes created a positive atmosphere, and celebrated cultural pride and youth achievements (e.g., youth flamenco dance award winners). Raffle prizes donated by local organizations, and bags of groceries provided by the local Food Bank were also provided to participants. Finally, the timing and location of the events were planned with CAB members, and additional youth advisors, who provided guidance on how to reduce barriers of transportation, and to involve as many different sub-groups within the community as possible.

Results

Health Disparities and Challenges Faced by the Latino/a Community

During the community forums, participants noted several key challenges and identified factors that they believed had negative ramifications for youth mental health and well-being. The most common challenges included (1) economic hardship, (2) violence exposure, (3) family acculturative stressors, and (4) social barriers to seeking health and mental health services.

Economic Hardship

Many community members described economic hardship as a central stressor for families. In particular, because of having to take on multiple jobs and long hours, parents felt that they did not have enough time to spend together as a family, and worried that it impacted how effectively they could parent, monitor, and bond with their children. For example, one mother described, “I am a single mother of four kids, it’s hard to get out of work to devote time to [my kids] after school.”

In addition, low-paying, high-demand jobs and limited income contributed to emotional stress and consequently, created more tension in family relationships. One immigrant parent described: “Work in this country demands a lot from you; you get home frustrated and just want to rest.” Community members also pointed out that work obligations and economic restrictions hampered their ability to adequately attend to their health and mental health needs, or participate in any recreational or pleasurable activities.

Violence Exposure

Community members described exposure to violence as a major stressor. In particular, both youth and adults identified domestic violence, interpersonal violence, gang and general community violence, and school bullying as the most common types of experiences. Interpersonal violence, including emotional abuse and verbal abuse, experienced by youth was cited as a central concern. Gang and general community violence were also pinpointed as particularly disquieting issues because of how pervasive they were; one parent explained “Estamos viviendo en tiempos muy intensos, hay cambios y violencia.” (“We are living in very intense times, there are changes and violence”). Community members lamented that children imitated the violence they witness in their environment. They also worried about the impact of exposure to violence, bullying, and harassment. For example, one parent expressed: “I’ve seen lots of bullying…it was hard on my child. My child doesn’t want to go to school now.”

Family Acculturative Stressors

Community forum participants described how acculturative stressors contributed to their distress and isolation, and increased barriers to accessing systems of care. In particular, for many parents, limited English language skills had a substantial impact in reducing their sense of self-efficacy, inhibited them from asking for help or knowing about and reaching community resources.

Parents also described both cultural and linguistic barriers to accessing school resources or afterschool activities, expressing the sentiment that did not have the necessary knowledge or support to navigate these systems. Acculturative gaps between parents and youth created conflict and divisions within the household. One parent explained: “Kids begin to speak more English so parents don’t understand what they are going through because they talk to their peers in English.” Parents specified that technology (i.e., cell phones, computers) reduced opportunities for shared experience, and interfered with family time because youth spent more time interacting with peers through technology than with parents.

Social Barriers to Seeking Health and Mental Health Stressors

Many community members described a deep lack of trust with systems of care, and reduced their engagement with schools, and health and mental health resources. Moreover, both parents and youth expressed their reluctance to seek help because of a sense of stigma, and the shame and fear of being labeled. Participants underscored that domestic violence and mental health problems were particularly difficult to disclose due to stigma.

Synthesis and Brainstorming Opportunity Areas to Reduce Health Disparities

HCD describes ‘opportunity areas’ as stepping stones that rearticulate problems in generative ways to allow for a group to brainstorm multiple future-centered solutions.15 Three major opportunity areas generated in our forums, to address stressors, barriers to care, and health disparities were: (1) parent support to increase knowledge and family involvement, (2) peer mentorship to create low stigma avenues to address youth mental health and well-being, and (3) community prevention efforts to increase sense of safety and belonging.

Providing Parent Support to Increase Knowledge and Family Involvement

A core opportunity area focused on provision of services to strengthen families. One group described the importance of “programas de apoyo familiar” (“family support programs”), with a particular focus on “aprender las señales de los jóvenes” (“understanding the warning signs in youth”). Participants highlighted the need for more parent education to increase their understanding of child development issues (“Parents have to foster emotional, physical, social and mental development for their kids. How can we promote this or teach this to parents in our community?”), and responding to their childrens’ needs and stressors such as peer relationships which sometimes led to conflict, harassment, and bullying. Participants suggested that the most helpful strategy would be “preparándonos como poder escuchar y ayudarlos a confiar en nosotros sin sentirse juzgados” (“helping us learn how to best listen to and help youth trust [parents] without them feeling judged by us”).

In addition to improving parent-child relationships, participants highlighted the importance of engaging and supporting parents in their relationships with service providers, including parent-school communication. Already existing systems, such as the parent-teacher association (PTA), and parent-parent support systems in neighborhoods were noted as primary opportunity areas. Participants underscored the importance of addressing the needs of those parents who had the fewest resources, and/or immigrant parents. One community member articulated, “as a community we have to look for ways to create support cushions for those that don’t know how the system works” and another similarly stated, “We need to offer more free resources for immigrant families who are not aware of their rights or don’t seek help because of documentation status.”

Peer Mentorship to Create Low Stigma Avenues to Address Youth Mental Health and Well-Being

Participants detected another opportunity area in creating and supporting interpersonal relationships that were transformative and health promoting, “como peer to peer” (“for example, peer to peer”), in the form of peer mentorship. Specifically, community members drew attention to the value of “jóvenes ayudando a otro jóvenes” (“youth helping other youth”). Groups expressed an interest in mentorship programs for youth that worked to buffer the effects of violence exposure and other stressors. They viewed this potential solution as one that could provide an avenue for addressing youth mental health and well-being in a way that had little to no negative stigma attached to it. If youth needed further support, they would also have a mentor who could provide a bridge. Parents also expressed an interest in these kinds of relationships for themselves.

Community Prevention Efforts to Increase Sense of Safety and Belonging

Finally, participants identified a third opportunity area: community prevention to increase a sense of safety and belonging. The importance of building safety was articulated, “Para trabajar en conjunto y tener una comunidad más segura” (“working together to have a safer community”).

Parents and youth focused on improving police-community relationships as groups generated ideas about how to increase diversity among members of the police force to create a stronger bridge. One community member explained, “tener mejor comunicación con la policía, con policías bilingües y respetando la privacidad de uno” (“having better communication with the police, greater number of bilingual police available, and more respect for one’s privacy”). Building trust and community policing efforts were highlighted as key elements to helping parents and youth feel safer with law enforcement officers helping to protect and support, rather than punish or demean, the community. Alternatives, such a hotline for assistance that did not necessitate police involvement, were suggested as possible ways to decrease fears about reporting community problems and to increase the likelihood that families would seek help and guidance when it was needed. In addition, strengthening community networks, creating more organic systems such neighborhood watch groups and other ways to reconnect community members to one another, were viewed as having great potential to improve belonging and sense of safety among Latino youth and families.

Discussion

This study provides an overview of how HCD strategies can be utilized within a CBPR study to address health disparities related to violence among Latino/a youth and families. Using a participatory co-design approach with community partners and advisors, communityforums were conceived. The CBPR+HCD integration approach used in the community forums included steps such as community driven discovery, anchoring the dialogue through community voices, engaging community members in idea generation, and synthesis and brainstorming opportunity areas. While this paper describes how the first phase of HCD was integrated into a CBPR project, the project is ongoing, and further phases of HCD (i.e., putting ideas into action through prototyping, mini-pilots, iteration, and ultimately, creating a sustainable model13) will be implemented based on these initial efforts.

A CBPR+HCD integration approach created an innovative way of generating ideas in an open community forum setting, where Latino/a families from multiple immigrant and lifespan generations, alongside service providers, students, and researchers, could equitably and efficiently distill collective knowledge about the social determinants of health disparities in the local community, and generate possible solutions to their identified needs. We used various HCD techniques including (1) storyboards to foster creativity and sharing, (2) prompting discussion with conversation starters, and (3) using a variety of formats for idea generation (i.e. verbal discussion, drawing, and written responses). All of these techniques enhanced the richness and quality of data gathered. This project contributes to the emerging literature on CBPR+HCD integration approaches to design and assess tools for underserved and vulnerable populations.15

In this study, community members converged on several focal points which highly correlated with existing literature on key social determinants of health disparities. Namely, the results were consistent with other studies which have established the detrimental effects of poverty,21 violence exposure,22–23 and family acculturative stress on violence24 (see Smokowski et al.25 for a review of acculturation and violence). Moreover, it is clearly established that social barriers to help-seeking, such as stigma,26 hinder opportunities for prevention and intervention efforts to buffer the negative effects of these stressors. In particular, one systematic review, of 144 manuscripts, found that stigma is among the top five cited barriers to accessing mental health, and is known to have a negative impact on help-seeking.26 Another systematic review of articles related to Latina survivors of violence found that the barriers to help-seeking also included language, and immigration/deportation fears.27

Participants identified parent support, peer mentorship, and community prevention as key opportunity areas for change. There are a number of evidence-based family strengthening interventions that help identify how best to provide parents with opportunities, skills, resources and supports to promote their children’s positive development,28 including the Strengthening Families Program which has been adapted for Latino/a families.29 Community health workers, or promotoras, can be an effective bridge to help elicit parent involvement in health promotion, prevention, and increasing access to health care has been highlighted in the literature.30 Research suggests that mentoring programs can promote positive youth development31–32 in areas such as high-risk and violent behaviors, academic/educational outcomes, and career/employment outcomes.32–34 There is less research on outcomes of mentoring specific to Latino/a youth, but preliminary findings are positive.35–37 In a meta-analysis, Hall32 identified a number of key features which help to make mentoring schedules successful, including monitoring of program implementation, screening of prospective mentors, matching of mentors and youth on relevant criteria, training, supervision, support for mentors, structured activities for mentors and youth, parental support and involvement, frequency of contact and length of relationship.

One area that appears to be under-addressed in the literature is improving community-police relationships among Latino/a communities. High levels of mistrust and fear of police among Latinos/as in the United States leads to feelings of isolation, disconnectedness, and a lack of safety.38 A multi-tiered intervention to reducing youth violence might incorporate elements relating to police relationships with youth and families.

One limitation was that community forums were not evenly composed of adults and youth. Our CAB helped plan and design the forums, including advertising and recruitment of participants, and we attempted to incorporate many elements to increase participation (e.g., food, childcare, raffle prizes, entertainment). It is possible that waiting for a specific event (e.g., community violence that recently occurred) to draw a larger group of concerned individuals would have increased the number of youth and adults. Future researchers should continue to identify elements that appeal to adolescent youth participants more directly. Given the challenges of drawing youth to the event itself, we were able to incorporate youth voices by scheduling youth speakers, and capitalizing on the narratives and images that youth had created as part of a youth photovoice project that led up to the community forums.

Other researchers also emphasize a framework that considers cultural and contextual aspects of ethnic minority youths’ lives.39 Innovative approaches to engaging youth in the dialogue about solutions, while also considering the stressors and contextual factors, may aid in moving towards increasing opportunities for youth to benefit from prevention and intervention efforts. Wilson and Deane40 conducted focus groups with youth to elicit their ideas about reducing these barriers and found that utilizing peer networks to share information about help-seeking may help to minimize barriers.

It is important to continue to recognizing the benefits of eliciting youth perspectives of solutions to address disparities/barriers, and increase the voices of ethnic minority individuals who are often not included in dialogues about health disparities. The current study aimed to drive these efforts forward by offering the possibility of integrating HCD strategies into CBPR partnership efforts to engage the community in a reciprocal dialogue. Future research should examine which strategies are most effective in generating creative and innovative solutions to challenging, and long-standing community problems. More research is needed that uses creative approaches to elicit youth, family, and community perspectives about solutions to address violence and related stressors, and reduce barriers that may impede access to prevention and intervention for health and mental health care.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure of Funding:

Funding for this project was made possible (in part) by Grant R13 HD075495-01 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention by trade names, commercial practices or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

- 1.U.S. Bureau. State and county quickfacts 2013. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/00.

- 2.National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Promoting culturally competent trauma informed practices. NCTSN Culture & Trauma Briefs. 2005;1(1) www.NCTSN.org. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alegria M, Greif Green J, McLaughlin K, Loder S. Disparities in child and adolescent mental health and mental health services in the US. New York, NY: William T Grant Foundation; 2015. https://philanthropynewyork.org/sites/default/files/resources/Disparities_in_child_and_adolescent_health.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escarce JJ, Kapur K. Access to and quality of health care. In: Tienda M, Mitchell F, editors. Hispanics and the Future of America. Washington, DC: National Academics Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sánchez M, Cardemil E, Adams ST, et al. Brave new world: Mental health experiences of Puerto Ricans, immigrant Latinos, and Brazilians in Massachusetts. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2014;20(1):16–26. doi: 10.1037/a0034093. doi: http://doi.org/10.1037/a0034093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McPhatter AR. Cultural competence in child welfare: What is it? How do we achieve it? What happens without it? Child Welfare. 1997;76(1):255–278. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perilla JL, Wilson AH, Wold JL, Spencer L. Listening to migrant voices: Focus groups on health issues in South Georgia. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 1998;15(4):251–263. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn1504_6. doi: http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327655jchn1504_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice. 2006;7(3):312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinto RM, McKay M, Escobar C. “You’ve gotta know the community”: Minority women make recommendations about community-focused health research. Women and Health. 2008;47(1):21–44. doi: 10.1300/J013v47n01_05. doi: http://doi.org/10.1300/J013v47n01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Methods for community-based participatory research for health. 2nd. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freire P. The pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banks S, Armstrong A, Carter K, et al. Everyday ethics in community-based participatory research. Contemporary Social Science. 2013;8(3):1–15. http://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2013.769618. [Google Scholar]

- 13.The field guide to human-centered design. IDEO.org. 2015 http://www.designkit.org/resources/1 Accessed on June 10, 2016.

- 14.Giacomin J. What is human centered design. The Design Journal. 2014;17(4):606–623. doi: 10.2752/175630614X14056185480186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durand MA, Alam S, Grande SW, Elwyn G. “Much clearer with pictures”: Using community-based participatory research to design and test a picture option grid for underserved patients with breast cancer. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010008. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010008. doi: http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kia-Keating M, Dowdy E, Morgan ML, Noam GG. Protecting and promoting: An integrative conceptual model for healthy development of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48(3):220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esposito N. From meaning to meaning: The influence of translation techniques on non-English focus group research. Qualitative Health Research. 2001;11(4):568–579. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroll JF, De Groot AMB. Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sperling J. Communicating more for less: Using translation and interpretation technology to serve limited English proficient individuals. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blinded.

- 21.McAra L, McVie S. Understanding youth violence: The mediating effects of gender, poverty and vulnerability. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2016;45:1–77. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1767921557?accountid=14522. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brady SS, Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB, Tolan PH. Adaptive coping reduces the impact of community violence exposure on violent behavior among African American and Latino male adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(1):105–15. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9164-x. doi: http://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9164-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gudiño OG, Nadeem E, Kataoka SH, Lau AS. Relative impact of violence exposure and immigrant stressors on Latino youth psychopathology. Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;39(3):316–335. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hokoda A, Galván DB, Malcarne VL, Castañeda DM, Ulloa EC. An exploratory study examining teen dating violence, acculturation and acculturative stress in Mexican-American adolescents. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2007;14(3):33–49. http://search.proquest.com/docview/916522947?accountid=14522. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smokowski PR, David-Ferdon C, Stroupe N. Acculturation and violence in minority adolescents: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30:215–263. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0173-0. doi: doi.org/10.1007/s10935-009-0173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45(1):11–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rizo CF, Macy RJ. Help seeking and barriers of Hispanic partner violence survivors: A systematic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;16(3):250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2011.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caspe M, Lopez ME. Lessons from family-strengthening interventions: Learning from evidence-based practice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Family Research Project; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chartier KG, Negroni LK, Hesselbrock MN. Strengthening family practices for Latino families. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2010;19(1):1–17. doi: 10.1080/15313200903531982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stacciarini JMR, Rosa A, Ortiz M, Munari DB, Uicab G, Balam M. Promotoras in mental health. Family & Community Health. 2012;35(2):92–102. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3182464f65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DuBois DL, Karcher MJ. Youth mentoring: Theory, research, and practice. In: DuBois DL, Karcher MJ, editors. Handbook of Youth Mentoring. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall J. Mentoring and young people: A literature review. Glasgow: The SCRE Centre, Faculty of Education, University of Glasgow; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grossman JB, Tierney JP. Does mentoring work? An impact study of the Big Brothers Big Sisters program. Evaluation Review. 1998;22(3):403–426. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9802200304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGill DE, Mihalic SF, Grotpeter JK, Elliott DS. Blueprints for violence prevention, book two: Big brothers big sisters of America. Boulder, CO: Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence; 1997. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/174195NCJRS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barron-McKeagney T, Woody JD, D’Souza HJ. Mentoring at-risk Latino children and their parents: Impact on social skills and problem behaviors. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2001;18(2):119–136. doi: http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007698728775. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernal DD, Alemán EJ, Garavito A. Latina/o undergraduate students mentoring Latina/o elementary students: A borderlands analysis of shifting identities and first-year experiences. Harvard Educational Review. 2009;79(4):560–585. http://dx.doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.4.01107jp4uv648517. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phinney JS, Campos CMT, Kallemeyn DMP, Kim C. Processes and outcomes of a mentoring program for Latino college freshmen. Journal of Social Issues. 2011;67(3):599–621. doi: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01716.x. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Theodore N. Insecure communities: Latino perceptions of police involvement in immigration enforcement. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois at Chicago; 2013. http://www.issuelab.org/resource/insecure_communities_latino_perceptions_of_police_involvement_in_immigration_enforcement. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodriguez M, Paradise M, et al. Cultural and contextual influences in mental health seeking: A focus on ethnic minority youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(1):44–55. doi: 10.10359/0022-006X.10.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson CJ, Deane FP. Adolescent opinions about reducing help-seeking barriers and increasing appropriate help engagement. J of Educational and Psychological Consultation. 2001;12(4):345–364. doi: 10.1207/S1532768XJEPC1204_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]