Abstract

In heterozygous patients with a diabetic syndrome called mutant INS gene–induced diabetes of youth (MIDY), there is decreased insulin secretion when mutant proinsulin expression prevents wild-type (WT) proinsulin from exiting the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which is essential for insulin production. Our previous results revealed that mutant Akita proinsulin is triaged by ER-associated degradation (ERAD). We now find that the ER chaperone Grp170 participates in the degradation process by shifting Akita proinsulin from high–molecular weight (MW) complexes toward smaller oligomeric species that are competent to undergo ERAD. Strikingly, overexpressing Grp170 also liberates WT proinsulin, which is no longer trapped in these high-MW complexes, enhancing ERAD of Akita proinsulin and restoring WT insulin secretion. Our data reveal that Grp170 participates in preparing mutant proinsulin for degradation while enabling WT proinsulin escape from the ER. In principle, selective destruction of mutant proinsulin offers a rational approach to rectify the insulin secretion problem in MIDY.

Introduction

Insulin is a peptide hormone secreted by pancreatic β-cells that controls blood glucose levels (1). Insulin biosynthesis begins when the precursor preproinsulin is translocated into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (2). This precursor harbors an N-terminal signal sequence, followed sequentially by the B chain, connecting C-peptide, and A chain. Upon translocation into the ER, the signal sequence is excised, forming proinsulin (2). Folding of proinsulin to its native conformation in the ER is coordinated with the formation of three highly conserved disulfide bonds (B chain 7th residue to A chain 7th residue, called the B7-A7 disulfide bond, plus the B19-A20 and A6-A11 disulfide bonds). When properly folded and oxidized, proinsulin is transported from the ER via the Golgi complex to immature secretory granules. Upon proteolytic excision of the C-peptide in this organelle, the B and A chains remain attached via their two interchain disulfide bonds, representing bioactive insulin that is poised for secretion to the bloodstream via exocytosis of secretory granules.

Recently over 29 missense mutations in the human insulin gene have been identified to cause an autosomal-dominant disease called mutant INS gene–induced diabetes of youth (MIDY) (3–6). Whereas most MIDY proinsulin mutants are misfolded and cannot form bioactive insulin, the initial onset of clinical insulin deficiency appears to be driven by dominant interference with the folding of wild-type (WT) proinsulin, impairing its ER exit and thereby limiting the production and eventual secretion of bioactive insulin. A decrease in insulin secretion causes hyperglycemia, which may provoke β-cells to further upregulate proinsulin synthesis (including the products of both mutant and WT alleles). Concomitant with proinsulin misfolding is ER stress and diabetes with eventual β-cell demise.

The most-studied MIDY mutant is Akita proinsulin, in which mutation of the A7 cysteine to tyrosine, so-called C(A7)Y, leaves an unpaired cysteine partner at the B7 position (7). This unpaired cysteine can potentially form an intermolecular disulfide bond with another misfolded Akita molecule or with WT proinsulin, generating both disulfide-bonded and noncovalent high–molecular weight (MW) protein complexes that are likely to engage ER resident proteins such as molecular chaperones. As a result of entry into such complexes, efficient ER exit of WT proinsulin is prevented, leading to the disease (3,5,6). The extent of blockade of WT proinsulin is directly related to the relative abundance of the mutant proinsulin protein (3,5). For this reason, we postulate that selective disposal of Akita proinsulin might facilitate the folding and export of the WT counterpart, thereby enhancing insulin secretion.

Because approximately one-third of cellular proteins are synthesized in the ER, it is not surprising that this organelle harbors rigorous protein quality control processes. One such process is called ER-associated degradation (ERAD), in which misfolded ER clients are retrotranslocated to the cytosol, where they are degraded by proteasomes (8–10). Recently, our laboratory and others identified several components of the ERAD machinery that facilitate degradation of Akita proinsulin (11), including the ER membrane-bound E3 ubiquitin ligase Hrd1, its membrane-binding partner Sel1L, and the cytosolic AAA+ ATPase p97 (12). We also reported that the ER luminal protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) may participate in reducing disulfide bonds that can help to liberate Akita proinsulin from high-MW protein complexes, generating smaller dimeric/trimeric species that are competent for retrotranslocation (12); another PDI family member, PDIA6 (encoding the P5 protein), may also play a role in this process (13). Whether other ER luminal components can help to drive Akita proinsulin along the ERAD pathway, and whether enhanced degradation of Akita proinsulin degradation can impact WT proinsulin export, are unknown.

Here we demonstrate that the ER luminal chaperone Grp170, an atypical member of the Hsp70 superfamily (14), promotes the degradation of Akita proinsulin. We show that Grp170 shifts the balance of high-MW oligomers bearing Akita proinsulin toward smaller oligomeric species that are capable of undergoing ERAD. Importantly, whereas WT proinsulin is trapped alongside the mutant in these high-MW protein complexes, overexpressing Grp170 can liberate WT proinsulin, enhancing Akita degradation and increasing WT insulin secretion. Hence, the ability to improve insulin secretion by selectively triaging a MIDY mutant suggests a rational strategy to treat the disease by rectifying the underlying MIDY defect.

Research Design and Methods

Antibodies

The antibodies used were as follows: rabbit anti-Myc (Immunology Consultants Laboratories); mouse anti-PDI and rabbit anti-Hsp90 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); rabbit anti-FLAG, and mouse/rabbit horseradish peroxidase secondary antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich); rabbit anti-GFP (green fluorescent protein; Proteintech); rabbit anti-Orp150/Grp170 (Abcam); rabbit anti-Sil1 (GeneTex); and mouse anti-VCP/p97 (Thermo Scientific). Chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich except when noted otherwise. Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) was from Acros Organics. DMEM, RPMI 1640 medium, and other cell culture reagents were from Life Technologies. Plasmids encoding Myc-epitope–tagged human C(A7)Y Akita mutant proinsulin (Akita-Myc), WT proinsulin-Myc, and WT proinsulin-superfolder GFP (sfGFP) were previously described (15,16). Human PDI trap mutant was a gift from T. Rapoport (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA). The INS-1 832/13 β-cell line was a gift from Christopher Newgard (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX). Subtilase cytotoxin complex (SubAB) and mutant SubAA272B were expressed in recombinant Escherichia coli with a B-subunit COOH-terminal His6 tag and purified by Ni-NTA chromatography, as previously described (17).

Cell Culture, Plasmid Transfection, Cycloheximide Chase, Immunoprecipitation, and Immunoblotting

Rat INS-1 832/13, human HEK 293T cells, and their derivative cell line (Tet-induced Grp170 expression cell line) were cultured at 37°C. Cells were seeded 1 day before transfection of 0.25–2 μg of plasmid DNA using polyethylenimine or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with cycloheximide (100 μg/mL) and chased for 0, 2, 4, and 6 h. Cells were harvested in PBS containing 10 mmol/L N-ethylmaleimide (NEM). For immunoprecipitation (IP), cells were lysed in 400 μL of radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with 10 mmol/L NEM and 1 mmol/L PMSF. Cells were incubated on ice for 10 min and centrifuged, and the resulting whole-cell extract (WCE) was incubated with antibody (1:200) at 4°C for 24 h, followed by 2 h of incubation with protein A/G-agarose beads at 4°C. Beads were washed and boiled in SDS sample buffer with or without 100 mmol/L dithiothreitol. For immunoblot analyses, cells were lysed in 100 μL of RIPA buffer to generate the WCE, which was boiled in SDS sample buffer with 100 mmol/L dithiothreitol. Samples were resolved on 8–15% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with specific primary and secondary antibodies.

Small Interfering RNA Knockdown of Grp170, Sil1, and PDI

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) was transfected into cells using RNAi MAX (Invitrogen), and cells were chased and harvested 48–72 h after treatment. Sequences of the siRNAs are as follows:

PDI siRNA: (5′-CAACUUUGAAGGGGAGGUCTT-3′; Invitrogen),

Grp170 siRNA 1: (5′-GCUCAAUAAGGCCAAGUUUTddT-3′; Invitrogen),

Grp170 siRNA 2: (5′-GCCUUUAAAGUGAAGCCAUdTdT-3′; Invitrogen),

Grp170 siRNA 3: (5′-GCCUUUGAAGAACGACGAAdTdT-3′; Invitrogen),

Sil1 siRNA: (5′-GCUGAUCAACAAGUUCAAUdTdT-3′; Invitrogen).

Proinsulin Secretion Assay

A plasmid encoding WT proinsulin tagged with sfGFP in the C-peptide was transfected into Grp170-inducible and rat INS-1 832/13 β-cells using polyethylenimine and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), respectively. For the inducible cell lines, 1 µg/mL tetracycline (Tet) was added at the time of transfection. Six hours after transfection, the medium was replaced with 500 µL fresh medium supplemented with Tet and incubated for 16 h. The medium was collected in a 1.7-mL tube with 6× SDS reducing sample buffer and boiled. Cells were also harvested in PBS, lysed in RIPA buffer, and denatured in reducing SDS sample buffer. These samples were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Sucrose Gradient Fractionation

To prepare the lysate, cells were harvested in 10 mL PBS supplemented with 10 mmol/L NEM and pelleted at 1,500g for 5 min. Cell pellets were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with 10 mmol/L NEM and 1 mmol/L PMSF and incubated on ice. After a first centrifugation at 16,000g for 10 min, the resulting supernatant was further cleared by ultracentrifugation at 50,000 rpm (100,000g) for 20 min. The resulting supernatant was layered over a 10–50% discontinuous sucrose gradient and centrifuged using a Beckman SW50.1 rotor at 29,000 rpm for 24 h at 4°C. After centrifugation, tubes were removed and 50-µL fractions were collected.

Results

Grp170 Knockdown Impairs Degradation of Akita Proinsulin With Depletion of Oligomeric Forms

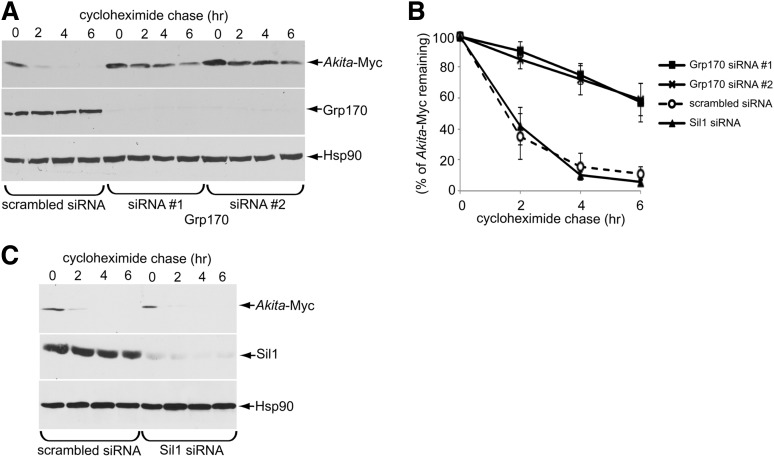

Grp170 was recently identified as a novel ER luminal factor promoting ERAD of misfolded ER clients (18), as well as toxic agents that hijack the ERAD pathway to cause infection (19,20). We therefore tested whether this chaperone promotes the degradation of Akita proinsulin using a cycloheximide chase approach in HEK 293T cells transiently expressing Akita-Myc, where the tag is appended within the C-peptide domain. We found that Grp170 knockdown using two different siRNAs targeted against Grp170 (siRNA 1 and 2) (Fig. 1A, second panel) significantly impaired the degradation of Akita-Myc when compared with cells treated with the control siRNA (scrambled) (Fig. 1A, top panel [the intensity of the Akita-Myc band is quantified in Fig. 1B]). Because Grp170 can act as a nucleotide exchange factor (NEF) against the ER luminal BiP ATPase (14), we asked whether the other ER-resident NEF called Sil1 also facilitates Akita-Myc degradation and found that it did not (Fig. 1C, top panel [quantified in Fig. 1B]). These results suggest Grp170 specifically promotes degradation of Akita proinsulin.

Figure 1.

Grp170 knockdown impairs Akita degradation. A: 293T cells expressing Akita-Myc (1 µg) were transfected with scrambled or Grp170-specific siRNA. Cells were then treated with 100 μg/mL cycloheximide for the indicated time and harvested. The resulting WCE was analyzed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. B: The Akita-Myc band intensity in A and C was quantified using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). Data represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. C: As in A, except cells were transfected with Sil1 siRNA.

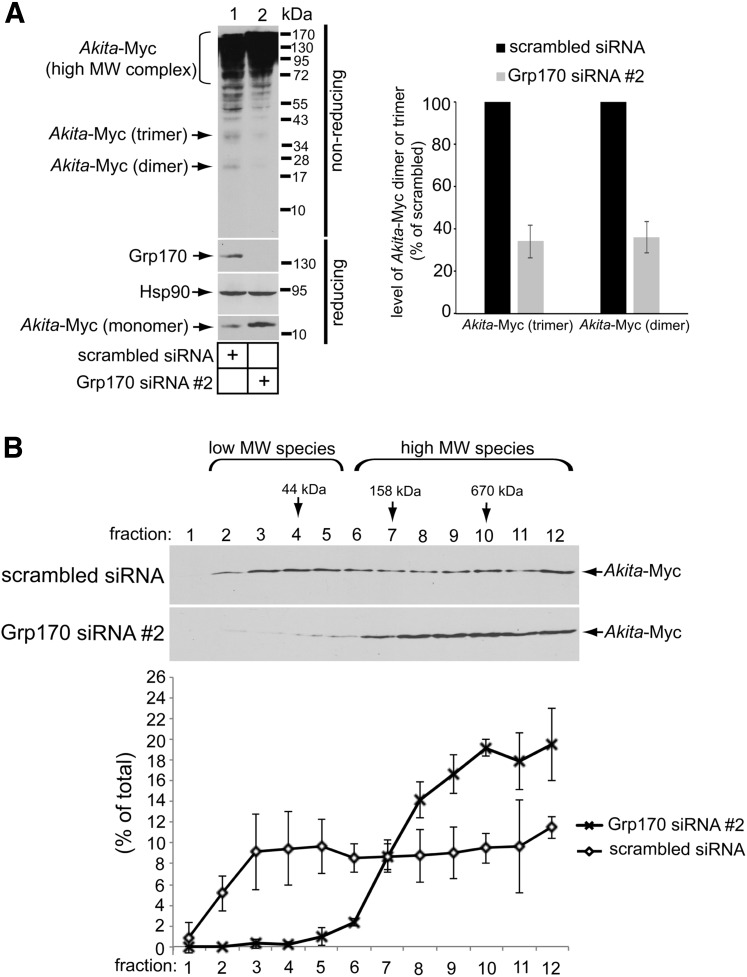

Using nonreducing SDS-PAGE, we previously reported that Akita-Myc forms high-MW protein complexes as well as smaller dimeric/trimeric oligomeric species (12). In cells with siRNA-mediated knockdown of Grp170, these smaller Akita-Myc oligomers were depleted when compared with the control (Fig. 2A, top panel; quantified in graph). However, under reducing conditions, in cells with siRNA-mediated knockdown of Grp170, the total level of Akita-Myc was actually increased (Fig. 2A, bottom panel). One plausible explanation for these results is that in the absence of Grp170, smaller oligomeric species of Akita proinsulin may be further shifted into higher-MW protein complexes. To evaluate this possibility, extracts from control or Grp170-depleted cells expressing Akita-Myc were sedimented on a 10–50% discontinuous sucrose gradient. Individual fractions were collected and subjected to reducing SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting using an antibody against Myc. Whereas Akita-Myc distributed throughout the entire gradient under the control condition, in Grp170-depleted cells the mutant proinsulin accumulated in fractions corresponding to high-MW protein species (Fig. 2B, compare top and second panels; the Akita-Myc band intensity is quantified in the graph below). These results are consistent with the notion that when Grp170 is knocked down, smaller oligomeric species of Akita proinsulin are further shifted into high-MW protein complexes. Our findings support the hypothesis that Grp170 promotes degradation by shifting the balance of Akita proinsulin in favor of lower MW (smaller) species that are competent to undergo ERAD (12).

Figure 2.

Depleting Grp170 increases the size of Akita oligomeric complexes. A: 293T cells expressing Akita-Myc (1 µg) were transfected with either scrambled siRNA or Grp170 siRNA #2. The resulting WCE was subjected to nonreducing and reducing SDS-PAGE, as indicated, and immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. The graph shows quantification of the relative amount of Akita-Myc dimeric and trimeric species generated from at least three independent experiments. B: 293T cells expressing Akita were transfected with either scrambled siRNA or Grp170 siRNA #2. Cells were harvested, lysed, and precleared; loaded onto a 10–50% sucrose gradient; and ultracentrifuged for 24 h. Samples were collected into 12 fractions, subjected to reducing SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted. The lower graph shows the relative quantity of Akita-Myc in each fraction. Data represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments.

Overexpressing Grp170 Facilitates Degradation of Akita Proinsulin

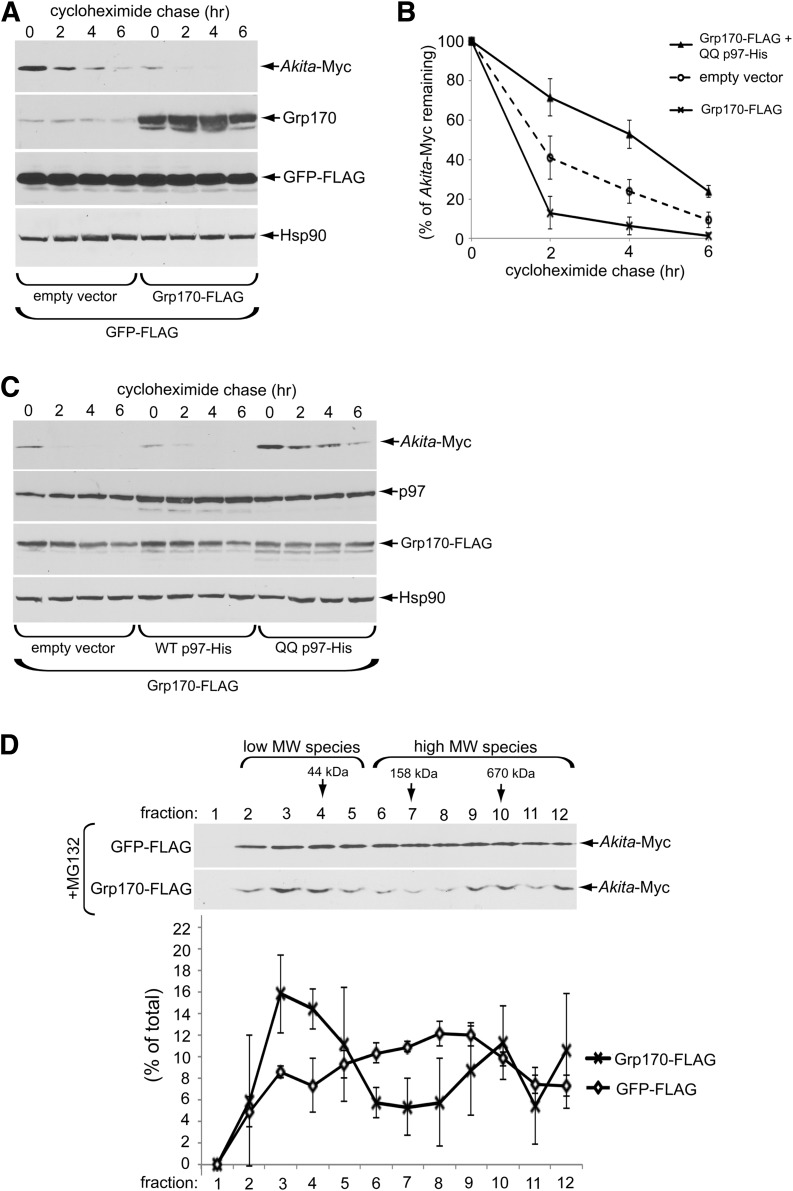

To complement the loss-of-function (knockdown) approach, we used a gain-of-function (overexpression) strategy to further assess the role of Grp170 in the degradation of Akita proinsulin. We found that overexpressing Grp170-FLAG (Fig. 3A, second panel) stimulated the time-dependent disposal of Akita-Myc (Fig. 3A, top panel [quantified in Fig. 3B]) but also lowered the steady-state level of Akita proinsulin even at the start of the experiment (Fig. 3A, top panel, zero time). The Grp170-induced degradation of Akita proinsulin is ERAD dependent because blocking ERAD by expressing the ATPase-defective p97 (QQ p97-His) (12,21) but not WT p97 prevented the overexpressed Grp170 from stimulating Akita degradation (Fig. 3C, top panel [Akita-Myc band intensity is quantified in Fig. 3B]). These data strongly suggest that Grp170 triggers Akita proinsulin degradation through the classic ERAD pathway.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of Grp170 stimulates Akita degradation. A: 293T cells expressing Akita-Myc (1 µg) and GFP-FLAG (0.25 µg) were transfected with an empty vector or a Grp170-FLAG plasmid (1 µg). Cells were then treated with cycloheximide for the indicated time and harvested, and the resulting WCE was analyzed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. B: The Akita-Myc band intensity in A and C was quantified with ImageJ. Data represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. C: As in A, except cells were transfected with Grp170-FLAG (1 µg) and additional empty vector, WT p97-His, or QQ p97-His construct (0.25 μg). D: 293T cells expressing Akita-Myc (1 µg) were transfected with GFP-FLAG or Grp170-FLAG plasmids (1 µg). Three hours preharvest, cells were treated with 10 μmol/L MG132. Cells were then harvested and separated on a 10–50% sucrose gradient by ultracentrifugation. The resulting fractions were separated using reducing SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting analysis. The lower graph shows relative distribution of Akita-Myc in each fraction. Data represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments.

To test the hypothesis that Grp170 promotes ERAD by shifting Akita proinsulin toward low-MW (smaller) species, we treated both control cells and cells overexpressing Grp170 with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 to block ERAD downstream in order to detect the oligomeric state of the accumulated Akita-Myc (omission of MG132 resulted in insufficient Akita-Myc accumulation to allow for such analysis; Fig. 3A, top panel). By sucrose gradient centrifugation, Akita-Myc in the control cell extract was found fairly evenly throughout the entire gradient (Fig. 3D, top panel and quantified below). Strikingly, in cells overexpressing Grp170, the distribution of Akita-Myc was shifted toward fractions 3–4, corresponding to low-MW (smaller) species (with an apparent decrease in fractions 6–8 corresponding to larger Akita-Myc oligomers) (Fig. 3D, bottom panel and quantified below). Thus, these gain-of-function studies also support the hypothesis that Grp170 facilitates ERAD of Akita proinsulin by favoring the generation of ERAD-competent low-MW (smaller) species.

Grp170 Promotes the Interaction of PDI With Akita Proinsulin

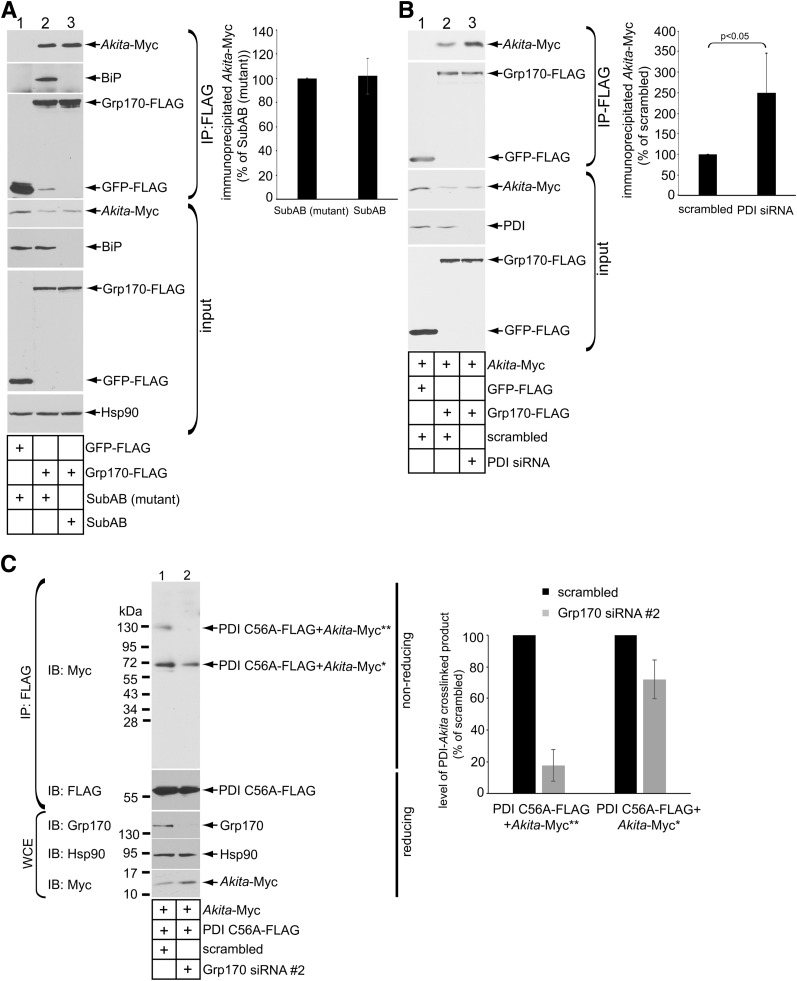

We envision that to promote an increase in ERAD-competent low-MW Akita proinsulin, Grp170 is likely to bind to the ERAD substrate. In cells expressing Akita-Myc and Grp170-FLAG (or a control protein [GFP-FLAG]), immunoprecipitating Grp170-FLAG but not GFP-FLAG coprecipitated Akita-Myc (Fig. 4A, top panel, compare lane 2 to 1). Endogenous BiP also coprecipitated with Grp170-FLAG but not GFP-FLAG (Fig. 4A, second panel). These findings are consistent with the established role of Grp170 as a NEF for BiP (14). However, regardless of whether cells were intoxicated with the SubAB toxin that cleaves BiP or an inactive mutant SubAA272B that cannot degrade BiP (Fig. 4A, fifth panel, compare lane 3 to 2) (22), the Grp170-Akita proinsulin interaction persisted (Fig. 4A, top panel; quantified in graph), indicating that the Grp170-Akita proinsulin association is BiP independent.

Figure 4.

Grp170 promotes the interaction of PDI with Akita proinsulin. A: 293T cells expressing Akita (1 µg) were transfected with GFP-FLAG or Grp170-FLAG (1 µg), with intoxication of SubAB (0.5 μg/mL) or mutant SubAA272B (0.5 μg/mL) where indicated for 6 h before harvest. FLAG-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from the resulting WCE using FLAG antibody conjugated beads. The precipitated material and input were subjected to reducing SDS-PAGE as indicated and immunoblotted using the appropriate antibodies. The graph represents the amount of immunoprecipitated Akita-Myc normalized to the level of immunoprecipitated Akita-Myc under the SubAB (mutant) control condition. B: 293T cells expressing Akita-Myc (1 µg) were transfected with scrambled siRNA or PDI siRNA as indicated. Cells were harvested and the resulting WCEs were subjected to IP using FLAG antibody conjugated beads. The immunoprecipitated material and input were subjected to reducing SDS-PAGE as indicated and immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. The graph represents the immunoprecipitated Akita-Myc level normalized to the level of immunoprecipitated Akita-Myc in the scrambled control. C: Similar to B, except PDI C56A-FLAG (1 µg) was transfected into cells transfected with scrambled siRNA or Grp170 siRNA #2. The resultant WCE was incubated with FLAG antibody conjugated beads, and the precipitated material was separated on nonreducing and reducing SDS-PAGEs followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Single and double asterisks indicate covalent adducts containing monomer or dimer of PDI C56A-FLAG + Akita-Myc, respectively. The graph represents the level of PDI-Akita crosslinked product formation normalized to the levels of these products generated under the scrambled siRNA control condition. IB, immunoblot.

Because PDI, an ER oxidoreductase, also interacts with Akita proinsulin (12), we examined the relationship between the respective PDI and Grp170 associations with Akita-Myc. We found that in cells coexpresssing Grp170-FLAG, knockdown of PDI caused Akita proinsulin association with Grp170 to be augmented (Fig. 4B, top panel, compare lane 3 to 2; quantified in graph). By contrast, in cells with knockdown of Grp170, the interaction of Akita proinsulin with a PDI “trap mutant” (that forms mixed disulfide adducts with Akita proinsulin) (12) diminished (Fig. 4C, top panel; quantified in graph). Thus, the efficiency of PDI interaction with Akita proinsulin appears to be promoted by the availability of Grp170, whereas the efficiency of Grp170 interaction with Akita proinsulin is not promoted (and might even be competed) by the availability of PDI.

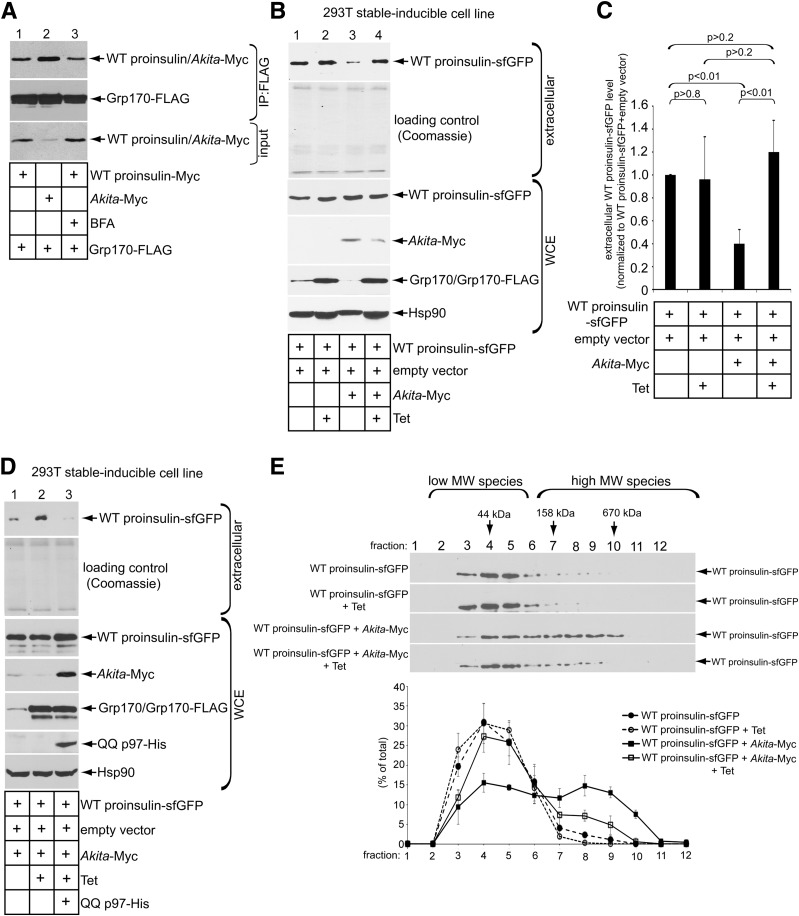

Grp170-Dependent Restoration of Small Oligomeric Forms Promotes ERAD of Akita Proinsulin Concomitant With ER Export of Coexpressed WT Proinsulin

Because WT and mutant proinsulins are coexpressed in the disease known as MIDY, we asked whether Grp170 displays preferential binding to either of these two proteins. In cells coexpressing Grp170-FLAG and either WT proinsulin-Myc or Akita-Myc (where the tag is incorporated within the C-peptide domain), precipitating equal amounts of Grp170-FLAG pulled down more Akita than WT proinsulin (Fig. 5A, top panel, compare lane 2 to 1). This preference is even more exaggerated when considering the lower abundance of Akita proinsulin levels in these cells (Fig. 5A, third panel, compare lane 2 to 1). Even when cells were treated with brefeldin A to block anterograde cargo exit from the ER (23), the Grp170 interaction with ER-entrapped WT proinsulin was not enhanced (Fig. 5A, top panel, compare lane 3 to 1). Taken together, these results indicate that Grp170 intrinsically favors the misfolded Akita proinsulin over WT proinsulin.

Figure 5.

Grp170 overexpression promotes ERAD of Akita and ER export of coexpressed WT proinsulin. A: 293T cells expressing Grp170-FLAG (1 µg) were transfected with WT proinsulin-Myc or Akita-Myc (1 µg) and treated with EtOH or 2.5 μmol/L brefeldin A for 1 h. Cells were harvested, lysed, and subjected to IP using FLAG antibody conjugated beads. The precipitated material and input were separated on a reducing SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. B: Secretion of WT proinsulin-sfGFP assay was performed in Grp170-inducible 293T cells under indicated transfection conditions. The extracellular medium and WCE were harvested, separated on SDS-PAGE, and subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibody. C: The WT proinsulin-sfGFP band intensity in B was quantified with ImageJ. Data represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. The Student t test was used to calculate the P values. D: As in B, except cells were transfected with QQ p97-His (0.25 µg) where indicated. E: The MW size of WT proinsulin-sfGFP in the WCE in B was analyzed by sucrose sedimentation centrifugation, as described in Fig. 2B. The lower graph represents the relative level of WT proinsulin-sfGFP in each fraction under the indicated experimental conditions.

Because Grp170 stimulates ERAD of Akita proinsulin (Fig. 3A and B), the preferential association of Grp170 with Akita proinsulin might allow WT proinsulin to escape from the ER en route to subsequent secretion. To test this, we used a 293T cell line with inducible expression of Grp170-FLAG (18). Conveniently, because 293T cells do not express prohormone convertases or secretory granules involved in the endoproteolytic conversion of proinsulin to insulin, proinsulin export from the ER of these cells can be monitored by the secretion of proinsulin itself. In these cells, transient expression of WT proinsulin-sfGFP (where sfGFP is incorporated within the C-peptide domain) was followed by induction of Grp170-FLAG via the addition of Tet. Tet addition did not affect WT proinsulin-sfGFP secretion (Fig. 5B, top panel [quantified in Fig. 5C]). As expected (3,6), coexpression of Akita-Myc inhibited the secretion of WT proinsulin-sfGFP (Fig. 5B, top panel [quantified in Fig. 5C]). Strikingly, Grp170-FLAG induction in cells expressing Akita-Myc restored the secretory trafficking of WT proinsulin-sfGFP (Fig. 5B, top panel [quantified in Fig. 5C]). Overcoming this dominant-negative behavior of Akita proinsulin on WT proinsulin by Grp170 requires an intact ERAD pathway, as WT proinsulin rescue by Grp170 could no longer be observed in cells coexpressing QQ p97-His (Fig. 5D, lane 3). These findings strongly suggest that the rescue of WT proinsulin export by Grp170 requires active ERAD and is mediated in parallel with the selective degradation Akita proinsulin.

In the absence of WT proinsulin, Akita proinsulin can form high-MW protein complexes. In this condition, overexpressing Grp170 stimulates Akita proinsulin degradation by increasing the abundance of ERAD-competent low-MW (smaller) species (Fig. 3). When WT proinsulin is coexpressed with Akita, WT proinsulin becomes entrapped along with Akita proinsulin in the ER (3,12). Thus, we hypothesize that increased activity of Grp170 should not only stimulate the degradation of Akita proinsulin, but WT proinsulin may also be disconnected from high-MW protein complexes, enhancing the export of WT proinsulin from the ER. We used sucrose sedimentation analysis to evaluate changes in the oligomeric state of WT proinsulin upon coexpression with Akita proinsulin, along with the effect of induced expression of Grp170. When expressed by itself, WT proinsulin-sfGFP was found in fractions corresponding to low-MW oligomeric species (Fig. 5E, top panel; quantified in the graph below); induction of Grp170 did not affect its oligomeric state (Fig. 5E, second panel; quantified below). As expected, coexpressing Akita-Myc caused a pool of WT proinsulin-sfGFP to migrate into higher-MW fractions (Fig. 5E, third panel; quantified below). Importantly, upon Grp170 induction, a significant pool (≥25%) of WT proinsulin-sfGFP was shifted out of the higher MW fractions back to its original smaller oligomeric state (Fig. 5E, fourth panel; quantified below). These findings suggest that increased Grp170 activity helps to increase the abundance of low-MW forms of both Akita proinsulin and WT proinsulin, thereby facilitating ERAD of Akita proinsulin while concomitantly facilitating anterograde transport of WT proinsulin.

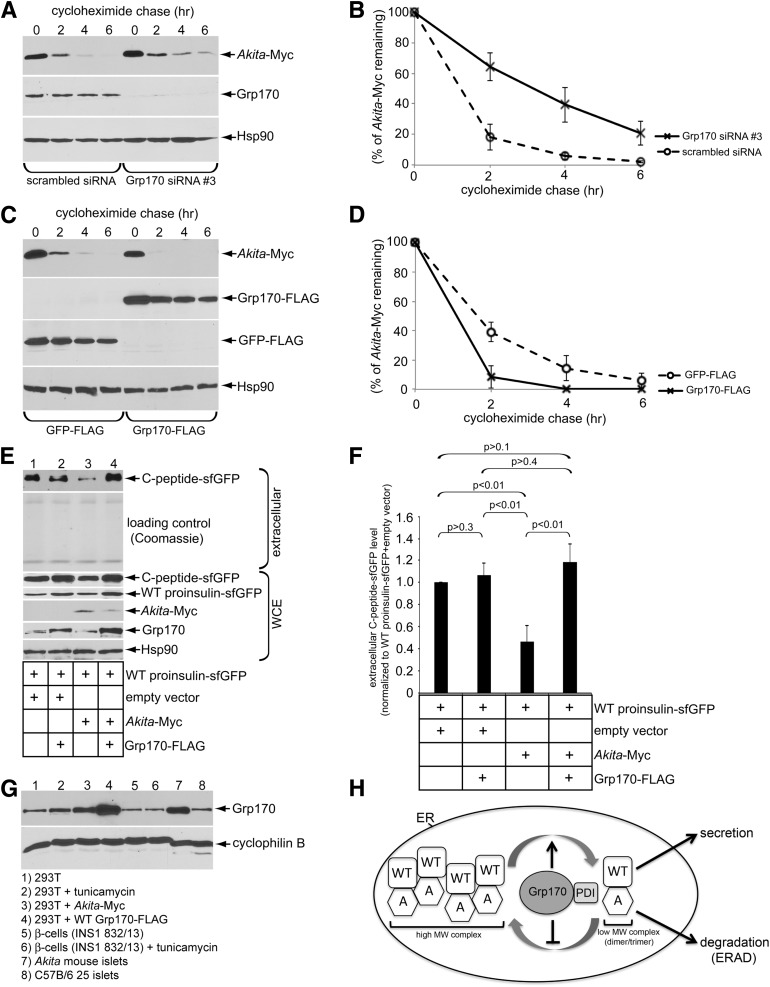

The Role of Grp170 in Akita Proinsulin Degradation and WT Proinsulin Secretion in β-Cells

Because the foregoing experiments were executed in a heterologous system, we asked whether these data could be recapitulated in the context of pancreatic β-cells. For this, we used INS1 832/13 (rat-derived) β-cells in which Akita-Myc is transiently expressed. Whereas depleting Grp170 decreased Akita-Myc degradation (Fig. 6A, top panel [quantified in Fig. 6B]), overexpressing Grp170-FLAG enhanced its degradation (Fig. 6C, top panel [quantified in Fig. 6D]).

Figure 6.

The role of Grp170 in Akita proinsulin degradation and WT proinsulin secretion in β-cells. A: β-Cells expressing Akita-Myc (1 µg) were transfected with scrambled siRNA or Grp170 siRNA #3 (because Grp170 siRNA #1 or #2 did not efficiently deplete endogenous Grp170 in these cells). Cells were then treated with cycloheximide for the indicated time and harvested, and the resulting WCE was analyzed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. B: The Akita-Myc band intensity in A was quantified using ImageJ. Data represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. C: β-Cells expressing Akita-Myc (1 µg) were transfected with GFP-FLAG or Grp170-FLAG (1 µg). Cells were then treated with cycloheximide for the indicated time and harvested, and the resulting WCE was analyzed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. D: The Akita-Myc band intensity in C was quantified using ImageJ. Data represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. E: Secretion of WT proinsulin C-peptide-sfGFP assay was performed in the β-cells under the indicated transfection conditions. The extracellular medium and WCE were harvested, separated on SDS-PAGE, and subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. F: The WT proinsulin C-peptide-sfGFP band intensity in E was quantified using ImageJ. Data represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. The Student t test was used to calculate the P values. G: Endogenous Grp170 protein expression across different physiological and pharmacology conditions. Treatment with 2.5 μg/mL tunicamycin was administered for 5 h. All transient transfections consisted of 1 μg of plasmid DNA for 24 h. Twenty-five Akita mouse islets (female) and 25 C57B/6 mouse islets (female) were harvested and lysed in 40 μL RIPA buffer with 10 mmol/L NEM plus protease inhibitors. H: A model depicting how Grp170 coordinates with PDI to promote ERAD of Akita (A) to restore WT proinsulin secretion (see Discussion for more details).

To measure insulin secretion from β-cells, we expressed WT proinsulin-sfGFP and subsequently monitored the C-peptide-sfGFP released to the extracellular medium (using high-sensitivity immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibody). Because β-cells harbor prohormone convertases, the intervening C-peptide-sfGFP is excised from proinsulin, costored in secretory granules, and secreted in parallel with insulin (16,24). In these cells, we found that coexpressing Akita-Myc with WT proinsulin-sfGFP blocked secretion of the C-peptide-sfGFP, as anticipated (Fig. 6E, top panel [quantified in Fig. 6F]). Remarkably, additional expression of Grp170-FLAG decreased the intracellular abundance of Akita-Myc and restored C-peptide-sfGFP secretion (Fig. 6E, top panel [quantified in Fig. 6F]). Hence, in a more physiologically relevant cellular context, these findings confirm that enhancing Grp170 activity allows for facilitating the ERAD of Akita proinsulin while concomitantly facilitating anterograde transport of WT proinsulin with the production of insulin (and C-peptide-sfGFP), leading to enhanced insulin (and C-peptide-sfGFP) secretion.

As all “Grps” (glucose-regulated proteins) are induced during stress, we asked whether our overexpression system was comparable in Grp170 expression to Akita mouse islets. For this, we used different pharmacological and physiological conditions to examine the expression of Grp170. Interestingly, Akita-Myc expression in HEK 293T cells drives Grp170 protein expression to levels similar to Akita mouse islets (Fig. 6G, top panel, compare lanes 3 to 7), clearly indicating that Grp170 levels are upregulated by misfolded proinsulin entrapped in the ER. Importantly, overexpression of Grp170 in HEK 293T cells enabled us to achieve protein levels that are slightly higher than the endogenous upregulation of Grp170 in Akita mouse islets (Fig. 6G, compare lanes 4 to 7). Indeed, it is this overexpression in 293T cells compared with the physiological ER stress response that drives the degradation of the Akita proinsulin mutant, supporting our central premise that it will require more than merely increasing Grp170 to ER stress levels in order to enhance degradation of the Akita proinsulin mutant in MIDY.

Discussion

In this discussion, we address two main points developed by the current studies. First, we have identified a novel ER luminal component that promotes degradation of a misfolded proinsulin. Second, we highlight a principle that may be exploited to rectify the protein-misfolding problem underlying the disease known as MIDY.

Function of Grp170 in ERAD of Akita Proinsulin

First, on the basis of our studies conducted both in 293T cells and in a pancreatic β-cell line, we propose that the ER-resident chaperone Grp170 promotes ERAD of Akita proinsulin by shifting the balance of Akita proinsulin in favor of smaller oligomeric species that are competent to undergo ERAD (Fig. 6H). Grp170 may accomplish this feat by using two different potential mechanisms. In one mechanism, Grp170 binds to the smaller species of Akita proinsulin in the ER, preventing their further association in high-MW complexes; these smaller species are more efficiently targeted for destruction along the ERAD pathway. Indeed, a recent study (25) suggests that Grp170 preferentially recognizes amino acids in clients that are predisposed to go on to aggregation. Whether Grp170 shields aggregation-prone residues within smaller species of Akita proinsulin remains to be tested. If this is the case, we speculate that the long COOH-terminal “holdase” domain of Grp170, which serves a role in substrate binding (14,26), may be responsible for interacting with these amino acids. Because Grp170 was shown to associate with the core ERAD membrane machinery via binding directly to Sel1L (18), Grp170 can execute its function proximal to the retrotranslocation site. This scenario may potentially allow Grp170 to present smaller species of Akita proinsulin for ER-to-cytosol translocation, thereby enhancing the efficiency of ERAD.

In an alternative mechanism, Grp170 associates with high-MW aggregates of Akita proinsulin and dissociates small oligomeric species from their entrapment within the high-MW protein complexes by untangling the noncovalent forces that help to hold these complexes together. Because Grp170 is not a reductase, it cannot directly disrupt disulfide-bonded protein complexes such as those seen in Fig. 2. This suggests that Grp170 must operate coordinately with a bona fide ER reductase, such as PDI, to reduce aberrant intermolecular (and intramolecular) disulfide bonds (12). Indeed, not only are Grp170 and PDI found together in the same multiprotein complex (27), but we also found that Grp170 availability promotes the association of PDI with Akita proinsulin. We consider it a reasonable possibility that Grp170-mediated disaggregation may expose disulfide bonds within the high-MW protein complexes, enabling PDI to more efficiently reduce these covalent bonds. Of note, the cytosolic counterpart of Grp170 is the Hsp110 chaperone family, including Hsp105 (28). In conjunction with a J-protein and Hsc70, Hsp105 has been shown to trigger disaggregation of aggregated protein complexes (29–32). Additionally, the Hsp105-Hsc70-J-protein triad can disassemble a large viral particle in vitro (33). These findings support the possibility that Grp170 may function in concert with a J-protein and BiP (the Hsp70 family member of the ER) to disaggregate high-MW protein complexes of misfolded proinsulin. If so, the nucleotide exchange function of Grp170 for BiP might serve as a pivotal link that connects the actions of these two ER chaperones.

Restoring Insulin Secretion Concomitant With ERAD of Mutant Proinsulin

The second critical point revealed in this study is a strategy to rectify the block in insulin secretion that is fundamental to the pathogenesis of MIDY. Because all such patients are heterozygotes, WT proinsulin is coexpressed with mutant proinsulin in MIDY (4,15). Interestingly, our analyses demonstrated that Grp170 displays a higher affinity for Akita proinsulin compared with WT proinsulin, suggesting that the efficiency of association of this chaperone with proinsulin is linked to the misfolded state. Whereas the precise molecular feature that Grp170 recognizes within Akita proinsulin remains undefined, we note that when both WT and Akita proinsulin are coexpressed, imposing a block downstream in the ERAD pathway not only causes Akita-Myc to accumulate in cells, but the intracellular abundance of coexpressed WT proinsulin increases also (Fig. 5D). Moreover, coexpressed WT proinsulin associates much more with BiP in Akita pancreatic islets than it does in WT mouse islets (15). Thus, WT proinsulin that is ordinarily recognized very little by Grp170 is likely to display new misfolded features that are more strongly recognized by Grp170 when WT proinsulin enters high-MW complexes containing Akita proinsulin.

With this in mind, we postulate that Grp170 engagement can have simultaneous beneficial effects on both Akita proinsulin and coexpressed WT proinsulin. Whereas small oligomeric species of Akita proinsulin (enriched by Grp170) are especially competent for ERAD, the enrichment of small oligomeric species of WT proinsulin offer an opportunity to fold successfully, followed by anterograde exit of WT proinsulin from the ER, allowing the formation of mature bioactive insulin that becomes available for secretion. Indeed, we found that in cells coexpressing Akita and WT proinsulins (where these two proteins are locked in the high-MW protein complexes), Grp170 induction liberated WT proinsulin from the high-MW complexes and restored insulin (C-peptide) secretion that was previously limited by the presence of Akita proinsulin. The dramatic effects of the overexpression of Grp170 in promoting insulin secretion suggest that the endogenous Grp170 level may be either insufficient to prevent Akita and WT proinsulins from entering the high-MW complexes or insufficiently abundant to effectively disaggregate high-MW species of misfolded proinsulin. In an in vivo transgenic mouse model, overexpressing Grp170 by 1.5-fold was unable to stimulate insulin secretion (34), suggesting that this is an insufficiently high level of Grp170 to overcome the misfolding block of proinsulin transport that leads to insulin secretion. Indeed, we now recognize that Akita mouse islets already have an ER stress–induced increase of Grp170 that is >1.5-fold and that still greater augmentation of Grp170 activity is required to rescue the WT proinsulin. As chemical compounds that act as allosteric regulators of the BiP/Hsp70 chaperones have been successfully developed (35), it is conceivable that analogous compounds strongly stimulating Grp170 activity could also be generated. If so, the therapeutic benefit of such an agent in restoring insulin secretion should be explored.

Conclusion

This study not only identifies a new ER factor that triages a misfolded mutant proinsulin molecule for destruction, it also suggests a potential strategy for remedying the block in WT proinsulin transport that causes the insulin deficiency of MIDY. These findings may also have broad implications for other ER protein-misfolding diseases.

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors thank members of the Tsai laboratory for helpful discussions.

Funding. P.A. and B.T. are supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant RO1-DK-111174. P.A. is also supported by NIH grant RO1-DK-48280. This work is also partially supported by the Protein Folding Disease Initiative (University of Michigan). C.N.C. is supported by Cellular and Molecular Biology Program NIH Training Grant T32-GM-007315.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. C.N.C. and K.H. researched data, contributed to discussion, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. A.A. isolated mouse islets, contributed to discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. A.W.P. and J.C.P. reviewed and edited the manuscript. P.A. and B.T. contributed to discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. B.T. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Hales CN. The role of insulin in the regulation of glucose metabolism. Proc Nutr Soc 1971;30:282–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steiner DF, Cunningham D, Spigelman L, Aten B. Insulin biosynthesis: evidence for a precursor. Science 1967;157:697–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu M, Hodish I, Rhodes CJ, Arvan P. Proinsulin maturation, misfolding, and proteotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:15841–15846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Støy J, Edghill EL, Flanagan SE, et al.; Neonatal Diabetes International Collaborative Group . Insulin gene mutations as a cause of permanent neonatal diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:15040–15044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss MA. Diabetes mellitus due to the toxic misfolding of proinsulin variants. FEBS Lett 2013;587:1942–1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu M, Hodish I, Haataja L, et al. . Proinsulin misfolding and diabetes: mutant INS gene-induced diabetes of youth. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2010;21:652–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J, Takeuchi T, Tanaka S, et al. . A mutation in the insulin 2 gene induces diabetes with severe pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction in the Mody mouse. J Clin Invest 1999;103:27–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruggiano A, Foresti O, Carvalho P. Quality control: ER-associated degradation: protein quality control and beyond. J Cell Biol 2014;204:869–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai B, Ye Y, Rapoport TA. Retro-translocation of proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum into the cytosol. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2002;3:246–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith MH, Ploegh HL, Weissman JS. Road to ruin: targeting proteins for degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science 2011;334:1086–1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen JR, Nguyen LX, Sargent KE, Lipson KL, Hackett A, Urano F. High ER stress in beta-cells stimulates intracellular degradation of misfolded insulin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;324:166–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He K, Cunningham CN, Manickam N, Liu M, Arvan P, Tsai B. PDI reductase acts on Akita mutant proinsulin to initiate retrotranslocation along the Hrd1/Sel1L-p97 axis. Mol Biol Cell 2015;26:3413–3423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorasia DG, Dudek NL, Safavi-Hemami H, et al. . A prominent role of PDIA6 in processing of misfolded proinsulin. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016;1864:715–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Behnke J, Feige MJ, Hendershot LM. BiP and its nucleotide exchange factors Grp170 and Sil1: mechanisms of action and biological functions. J Mol Biol 2015;427:1589–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu M, Haataja L, Wright J, et al. . Mutant INS-gene induced diabetes of youth: proinsulin cysteine residues impose dominant-negative inhibition on wild-type proinsulin transport. PLoS One 2010;5:e13333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haataja L, Snapp E, Wright J, et al. . Proinsulin intermolecular interactions during secretory trafficking in pancreatic β cells. J Biol Chem 2013;288:1896–1906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paton AW, Srimanote P, Talbot UM, Wang H, Paton JC. A new family of potent AB(5) cytotoxins produced by Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli. J Exp Med 2004;200:35–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue T, Tsai B. The Grp170 nucleotide exchange factor executes a key role during ERAD of cellular misfolded clients. Mol Biol Cell 2016;27:1650–1662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams JM, Inoue T, Chen G, Tsai B. The nucleotide exchange factors Grp170 and Sil1 induce cholera toxin release from BiP to enable retrotranslocation. Mol Biol Cell 2015;26:2181–2189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue T, Tsai B. A nucleotide exchange factor promotes endoplasmic reticulum-to-cytosol membrane penetration of the nonenveloped virus simian virus 40. J Virol 2015;89:4069–4079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye Y, Meyer HH, Rapoport TA. The AAA ATPase Cdc48/p97 and its partners transport proteins from the ER into the cytosol. Nature 2001;414:652–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paton AW, Beddoe T, Thorpe CM, et al. . AB5 subtilase cytotoxin inactivates the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone BiP. Nature 2006;443:548–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klausner RD, Donaldson JG, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Brefeldin A: insights into the control of membrane traffic and organelle structure. J Cell Biol 1992;116:1071–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu S, Larkin D, Lu S, et al. . Monitoring C-Peptide Storage and Secretion in Islet β-Cells In Vitro and In Vivo. Diabetes 2016;65:699–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Behnke J, Mann MJ, Scruggs FL, Feige MJ, Hendershot LM. Members of the Hsp70 family recognize distinct types of sequences to execute ER quality control. Mol Cell 2016;63:739–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behnke J, Hendershot LM. The large Hsp70 Grp170 binds to unfolded protein substrates in vivo with a regulation distinct from conventional Hsp70s. J Biol Chem 2014;289:2899–2907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meunier L, Usherwood YK, Chung KT, Hendershot LM. A subset of chaperones and folding enzymes form multiprotein complexes in endoplasmic reticulum to bind nascent proteins. Mol Biol Cell 2002;13:4456–4469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andréasson C, Rampelt H, Fiaux J, Druffel-Augustin S, Bukau B. The endoplasmic reticulum Grp170 acts as a nucleotide exchange factor of Hsp70 via a mechanism similar to that of the cytosolic Hsp110. J Biol Chem 2010;285:12445–12453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rampelt H, Kirstein-Miles J, Nillegoda NB, et al. . Metazoan Hsp70 machines use Hsp110 to power protein disaggregation. EMBO J 2012;31:4221–4235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shorter J. The mammalian disaggregase machinery: Hsp110 synergizes with Hsp70 and Hsp40 to catalyze protein disaggregation and reactivation in a cell-free system. PLoS One 2011;6:e26319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mattoo RU, Sharma SK, Priya S, Finka A, Goloubinoff P. Hsp110 is a bona fide chaperone using ATP to unfold stable misfolded polypeptides and reciprocally collaborate with Hsp70 to solubilize protein aggregates. J Biol Chem 2013;288:21399–21411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nillegoda NB, Kirstein J, Szlachcic A, et al. . Crucial HSP70 co-chaperone complex unlocks metazoan protein disaggregation. Nature 2015;524:247–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ravindran MS, Bagchi P, Inoue T, Tsai B. A non-enveloped virus hijacks host disaggregation machinery to translocate across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. PLoS Pathog 2015;11:e1005086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozawa K, Miyazaki M, Matsuhisa M, et al. . The endoplasmic reticulum chaperone improves insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2005;54:657–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li X, Srinivasan SR, Connarn J, et al. . Analogs of the allosteric heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) inhibitor, MKT-077, as anti-cancer agents. ACS Med Chem Lett 2013;4:1042–1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]