Summary

Suicide is a complex public health problem of global dimension. Suicidal behaviour (SB) shows marked differences between genders, age groups, geographic regions and socio-political realities, and variably associates with different risk factors, underscoring likely etiological heterogeneity. Although there is no effective algorithm to predict suicide in clinical practice, improved recognition and understanding of clinical, psychological, sociological, and biological factors may facilitate the detection of high-risk individuals and assist in treatment selection. Psychotherapeutic, pharmacological, or neuromodulatory treatments of mental disorders can often prevent SB; additionally, regular follow-up of suicide attempters by mental health services is key to prevent future SB.

Introduction

Suicide takes a staggering toll on global public health, with almost one million people annually who die from suicide world-wide.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared that reducing suicide-related mortality is a “global imperative,” a welcome contrast to the traditional taboo that has surrounded suicidal behaviours (SBs). Cultural and moral beliefs about suicide, and unnecessarily pessimistic views about our current clinical capability to intervene and prevent suicide are barriers against patient self-disclosure and clinicians’ routine inquiry about suicidal thoughts. Approximately 45% of individuals who die by suicide consult a primary care physician within one month of death, yet there is rarely documentation of physician inquiry or patient disclosure.2 In this paper, we review the epidemiology, risk factors, and extant effective interventions based in primary care and specialty mental health facilities aimed at the prevention or treatment of SB.

Definitions and assessment

Clear discussion, accurate research, and efficient treatment require accepted definitions of SBs. The difficulty of establishing intent of self-harming behaviours has hindered efforts to streamline the historically heterogeneous suicide nomenclature, but recent efforts, such as those resulting in the Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment,3 have contributed to standardizing nomenclature (table 1). SB exists on a spectrum of severity, on the basis of family studies showing the “progression” from less to more severe forms of suicidal ideation (SI) and behaviour, and from family and biological studies showing overlap between attempted and completed suicide.4

Table.

Nomenclature for SB

| Category | Definition | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Suicide | A fatal self-injurious act with some evidence of intent to die | |

| Suicide attempt (SA) | A potentially self-injurious behaviour associated with at least some intent to die | Some younger suicide attempters will report that their main motivation is other than to die, such as to escape an intolerable situation, to express hostility, or to get attention; however many will nonetheless acknowledge the possibility that their behaviour could have resulted in death. SA is characterized by greater functional impairment than non-suicidal self-injury (see below). |

| Active suicidal ideation (SI) | Thoughts about taking action to end one’s life, including: identifying a method, having a plan, and/or having intent to act | More specific SI like having made a plan or having intent is associated with a much greater risk of an SA with 12 months |

| Passive SI | Thoughts about death, or wanting to be dead with any plan or intent | |

| Non-suicidal self-injury | Self-injurious behaviour with no intent to die | NSSI and SA differ in terms of motivation, familial transmission (found only in SB), age of onset (younger in NSSI), psychopathology, and functional impairment (greater in SA). NSSI most commonly consists of repetitive cutting, rubbing, burning, or picking. The main motivations are either to relieve distress, “feel something,” induce self-punishment, get attention, or to escape a difficult situation. |

| Suicidal events | The onset or worsening of SI or an actual SA or an emergency referral for SI or SB | This endpoint is often used in pharmacological studies. The inclusion of rescue procedures in this umbrella category is because a patient with ideation who then received emergency intervention might have made an attempt had he or she not been recognized and treated. |

| Preparatory acts toward imminent SB | Action is taken to prepare to hurt oneself, but suicidal acts are stopped either by self or others | |

| Deliberate self-harm (DSH) | Any type of self-injurious behaviour, including SAs and NSSI | The combination of SA and NSSI into a single category reflects their high comorbidity, shared diathesis, and the fact that NSSI is a strong predictor of eventual SA. Not all events classified as an SA are motivated by a true desire “to die,” but rather by desires to attract attention, to escape, and to communicate hostility. However, when only DSH is reported, SA and NSSI cannot be subsequently disaggregated. |

Search strategy and selection criteria

Since the previous Lancet Seminar on Suicide5 was published in 2009, we searched PubMed and the Cochrane Library from January 2009 to May 2015 using the terms suicide, suicidal behaviour and self-harm along with category-specific terms, including epidemiology, genetics, intervention, prevention, and psychotherapy. Titles and abstracts of search results were sorted to assess inclusion of the article in the literature pool. Further articles were identified by scanning the reference sections of selected publications. We primarily selected articles published in the last 6 years, but also included relevant and notable articles published prior to 2009. We selected only English-language publications.

Epidemiology

Precise global estimates of suicide rates are difficult to obtain, as only 35% of WHO Member States have comprehensive vital registration with at least five years of data.1 Globally, there are an estimated 11·4 suicides per 100,000 people, resulting in 804,000 suicide deaths worldwide.1 There is considerable inter- and intra-country variability in suicide rates, with as much as a 10-fold difference between regions; this is in part correlated with economic status and cultural differences.1 Cultural influences may trump geographic location, since the suicide rates of immigrants are more closely correlated with their country of origin than with their adoptive country.6 Across the globe, indigenous peoples are burdened with markedly increased rates of suicide,7 which may be due to disruption of traditional cultural and family supports, lower socioeconomic status, and increased prevalence of alcohol and substance use, which are also risk factors for suicide in the general population.7

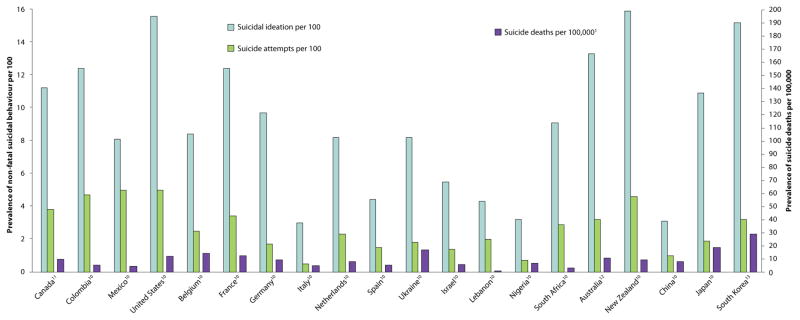

Non-fatal SBs occur at significantly higher frequencies than suicides.8,9 International comparisons based on the WHO World Mental Health Survey (2001–2007) data (n=108,705) indicate that the average twelve-month prevalence estimates are 2·0% and 2·1% for ideation, and 0·3% and 0·4% for attempts in developed and developing countries, respectively.9 Previously reported global lifetime prevalences for ideation and attempts were 9·2% and 2·7%, respectively (n=84,850),10 but rates of SI and SB vary strikingly between countries (figure 1).1,10–13 Individuals who report SI within the previous 12 months have significantly higher 12-month prevalence rates of SAs (15·1% in developed and 20·2% in developing countries), and suicidal planning further increases risk.8,9 Studies find that within 12 months, approximately one third of adolescent suicide ideators will go on to attempt suicide,8 and suicide attempters presenting to an emergency department have 12-month risks of suicide and of repeated SA of 1·6% and 16·3%, respectively, with a 5-year risk of suicide of 3·9%.14

Figure 1. Cross-national prevalence of SB.

Non-fatal SB data are from the cited references. Suicide fatalities (solid bars) reported are from the World Health Organization’s 2014 report, Mental health: suicide prevention.1

In high-income countries, middle-aged and elderly men have the highest rates of suicide.1 However, increasing rates of youth suicide are a growing cause for concern, and suicide is the second leading cause of death in individuals 15–29 years.1 The peak incidence of SI and SB is among adolescents and young adults, with lifetime prevalences of SI and SB of 12·1–33%, and 4·1–9·3%, respectively.8,15 In the elderly, rates of suicidality are also high, particularly among those with physical disorders, depression, and anxiety.16 Gender is also a clear factor in SB, with higher rates of SI and SA among females,9,10 but with generally higher rates of suicide deaths in males (15/100,000 in males vs. 8/100,000 in females, globally).1 The ratio of male to female suicides is higher in high vs. low-middle income countries (3·5 vs. 1·6) and Western vs. Asian/Pacific countries (3·6–4·1 vs. 0·9–1·6).1 Seasonal variation in suicide rates has also been reported, with peak incidence in spring and summer months, and suicide rates may correlate with latitude and exposure to sunshine.17

Contemporary models of suicide risk

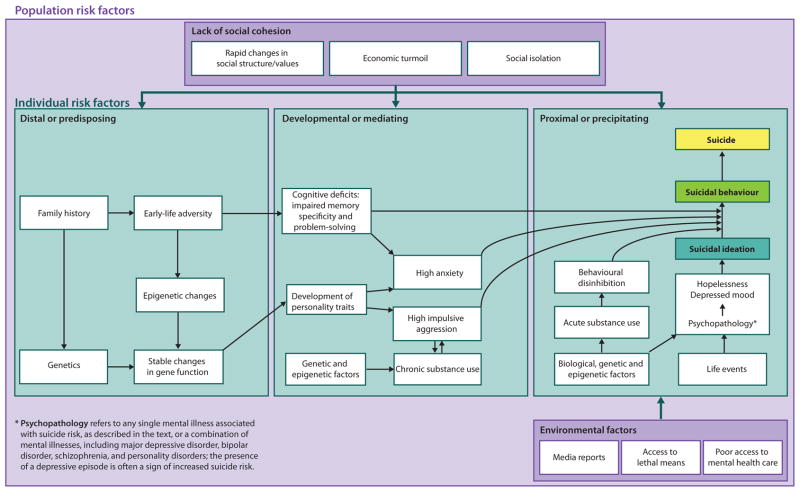

In the last century, we have progressively recognized the contributions of both social and individual factors to understanding suicide risk. A number of models have been proposed, most emphasizing the interaction between predisposing and precipitating factors.18–21 Figure 2 presents putative temporal relationships between the different suicide risk factors discussed in this paper. Suicide is etiologically heterogeneous, with significant variability in the strengths and patterns of association of risk factors across gender, age, culture, geographic location, and personal history. Thus, models have been proposed to explain suicide risk in specific subgroups of suicide, such as those exposed to early-life adversity (ELA).22,23

Figure 2. Model for suicide risk.

Suicide risk is modulated by a range of factors both at the population and individual levels. Population factors related to social cohesion include wide-scale changes to the social structure, societal pressures such as economic turmoil, and social isolation of individuals or groups of individuals. Environmental factors in the population that could impact an individual’s risk for suicide include representation of suicide in the media, accessibility of lethal means of suicide and difficulties in accessing appropriate healthcare. Individual risk factors can be grouped into distal (or predisposing), developmental (or mediating), and proximal (or precipitating) factors, and many of these factors interact to contribute to the risk of developing SBs.

Risk factors and associated mechanisms increasing risk for suicide

Population-level risk factors for suicide

More than a century ago, Durkheim recognized the profound impact of population-level social factors on suicide rates. Increases in suicide rates among indigenous peoples, such as the Canadian Inuit, correlate with social changes such as forced settlement, assimilation and disruption of traditional social structure.7 Conversely, there is evidence of very low suicide rates among homogenous societies with high social cohesion, common values, and moral objections to suicide,24,25 although the latter may also lead to under-reporting. Economic crises resulting in unemployment and decreased personal income have been correlated with increases in suicide, particularly in males, although a direct causal relationship has not yet been established.26,27 Media reporting of suicide also influences suicide rates, particularly within the first 30 days of publicity, with increases in the rates proportional to the amount of publicity, when details of a method are provided, if the decedent was a celebrity, and if the suicide was romanticized rather than reported in association with mental illness and the adverse consequences of the suicide on survivors.28 Adolescents and young adults are particularly susceptible to the effects of media publicity.29

Individual risk factors for suicide

Distal or predisposing risk factors

SBs run in families (odds ratio [OR] for first or second degree relatives ranging between 1·7–10·62, when adjusting for degree of relation),4,30,31 indicating that distal factors can increase suicide risk. Family studies show that the risk of attempts is increased in the relatives of those who died by suicide, and vice versa.32 Family concordance for SB is not attributable to imitation because adoption studies show concordance between biological, but not adoptive relatives.33 While psychopathology also aggregates in families, the transmission of SB appears to be mediated through the familial transmission of impulsive aggression.4,34 Twin and adoption studies indicate that genetic factors account for part of the familial transmission of SB, with estimates of heritability between 30–50%.35,36 However, when the heritability of other psychiatric conditions is taken into account, the specific heritability of suicidality may be closer to 17·4% for SAs, and 36% for SI.36 SI appears to be co-transmitted with mood disorders and shows a distinct pattern for transmission from SB.4,37 Despite consistent evidence for the heritability of SB, the identification of specific genes linked to suicide risk remains elusive, in spite of several candidate-gene and genome-wide association studies, which have mostly provided inconclusive results.22 Future genetic approaches in suicide research will gain from modelling the interactions between experience and genes.

In addition to heritable factors, other psychosocial, demographic and biological factors act distally, increasing vulnerability to suicide.18 Sexual orientation is associated with increased suicide risk, and while psychological autopsy-based studies investigating completed suicides have not consistently found an over-representation of sexual minority status in suicides, analysis of registry-based data suggests that individuals with a history of same-sex relationships have a 3–4 fold greater risk of dying by suicide, with a disproportionately greater risk for men than for women, and belonging to a sexual minority is universally linked with increased rates of SAs irrespective of gender.38

Another well-characterized risk factor is exposure to ELA, generally defined as parental neglect, childhood physical, sexual or emotional abuse. The association between ELA and lifetime suicide risk is supported by evidence from prospective39,40 and retrospective longitudinal,41 as well as multiple case-control studies,23 and is moderated by several factors, including the type of abuse (neglect, physical or sexual abuse), the frequency of the abuse, and the relationship of the victim with the abuser.40 ELA may also be familially transmitted, partly explaining the familial aggregation of SB.42 ELA may induce long-term effects through epigenetic changes in specific gene pathways. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis regulates physiological responses to stress to facilitate coping in the face of changing environments or challenging events, mainly through cortisol regulation. Individuals who have experienced ELA often exhibit a hyperactive HPA axis and an increased stress response,43 which is partly due to the decreased hippocampal expression of the glucocorticoid receptor and associates with increased DNA methylation of its promoter,44 a finding consistently observed in both central and peripheral tissues.45 The FK506-binding protein (FKBP5), involved in inhibiting glucocorticoid receptor signal transduction, may also contribute to the risk of SB, since FKBP5 sequence variants are associated with an increased risk of SB, especially in individuals who have experienced ELA.22

ELA is also associated with epigenetic modification of genes involved in neuronal plasticity, neuronal growth and neuroprotection.46,47 Animal models of ELA show hypermethylation, and consequent downregulation of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).48 Human studies using brain tissue from suicides show that mRNAs encoding BDNF and its receptor, tropomyosin-related kinase B (TRKB), are downregulated in multiple brain regions including the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus, and some studies report differential methylation of BDNF and TRKB in suicidal brains.49,50 Genome-wide association studies focused on differential methylation in central and peripheral tissues of suicidal individuals having experienced ELA have identified methylation changes in genes associated with stress, cognitive processes, and neural plasticity.46,47 This combined evidence of epigenetic regulation of suicide-related gene pathways supports the hypothesis that ELA mediates suicide risk through long-term epigenetic regulation of gene expression profiles.

Another potential risk factor for SB is infection by the brain-tropic parasite Toxoplasma gondii.51,52 In a large sample of women tested for T. gondii infection at childbirth and followed for over a decade, seropositive women had increased risk of self-directed violence, violent SA and suicide (OR=1·53, 1·81, and 2·05, respectively), with risk of self-directed violence correlated to levels of anti-toxoplasma antibodies.51 One proposed mechanism for this association implicates immunological responses to infection, which may alter neurotransmitter activity.53

Developmental or mediating risk factors

Distal factors are likely to act through personality traits and cognitive styles that mediate their association with SB. Although depression and anxiety make strong contributions to SB across the lifespan, both retrospective and prospective studies find that interpersonal conflict, impulsive aggression, conduct disorder, antisocial behaviour, and alcohol and substance abuse are more salient for SB in adolescents and young adults, while harm avoidance and mood disorders are increasingly present with increasing age.54,55 Younger subgroups of suicides often present a high burden of adversity and a history of childhood abuse/neglect.55 The highest risk for SB across the lifespan exists when a mood disorder that is associated with SI co-occurs with other conditions that either increase distress (panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder) or decrease restraint (conduct and antisocial disorders, substance abuse).8 The development of high impulsive-aggressive behaviours and high anxiety traits may also partly explain the relationship between ELA and suicide risk,56 and these traits explain part of the familial aggregation of SB.34,57 ELA causes cognitive deficits, particularly problem-solving and memory specificity, which are contributors to suicidality.58,59 ELA may play an especially important role in adolescent and young adult SB because adversity is related to earlier age of onset of psychiatric disorder,60 and because the cognitive effects of adversity interact with adolescents’ and young adults’ incompletely developed prefrontal cortical systems, which in turn increases the likelihood of risk-taking and impulsive behaviour.61 Individuals with a higher than average cortisol response to stress,62 a history of SI,63 or a first-degree relative who has committed suicide,64 have impaired cognitive functions following social or emotional stressors, as measured by decision-making, problem-solving and executive function. Adolescents who display poor problem-solving are more likely to experience SI after a stressful experience than their counterparts,65 suggesting that altered cognitive patterns may mediate the impact of ELA on SB.

Proximal or precipitating risk factors

Proximal risk factors are temporally associated with SB and act as their precipitants. Aside from past SA, psychopathology is the single most important predictor of suicide and strongly associates with other forms of SB.66,67 Retrospective, proxy-based interviews with informants, commonly referred to as psychological autopsies, have frequently been used to investigate the association between psychopathology and suicide, and consistently indicate that approximately 90% of individuals who die by suicide had an identifiable psychiatric disorder prior to death.66 Most individuals with a psychiatric illness do not die by suicide, but some psychiatric illnesses are more strongly linked to SBs than others. Major depressive episodes, associated with either major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder, account for at least half of suicide deaths.68 Among bipolar patients, mixed state episodes most strongly associate with SAs, with risk increasing according to the amount of time spent in mixed depressive episodes;68 suicide risk is highest within the first year of illness69 and associates with feelings of hopelessness.68 Adults with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders are also at heightened risk,70 with main clinical predictors of suicide including presence of depressive symptoms, young age, male gender, education, positive symptoms and illness insight.71

Multiple other factors are commonly present among suicides and may exacerbate underlying risk or interact with depression to increase risk of engaging in SBs, such as alcohol and drug-related disorders.67,72

Other illnesses commonly present among suicides are eating disorders and personality disorders, particularly cluster B personality disorders such as borderline and antisocial personality disorder, which are conditions characterized by high levels of aggressive and impulsive traits.73 Suicides frequently have histories of more than one disorder, and evidence suggests that in individuals with psychiatric illnesses such as depression, which associates with SI, comorbidity with disorders characterized by severe anxiety/agitation or poor impulse control predicts SB.72,73 Studies also suggest that suicides who do not meet criteria for a mental illness were probably affected by a psychiatric disorder, but the psychological autopsy protocol applied failed to detect it.74 Although psychological autopsies present a number of limitations inherent to their retrospective, proxy-based nature, they are often the only way to identify and describe risk factors that contribute to suicide and generally exhibit strong concordance between independent raters, personal and proxy-informants, and ante-mortem and post-mortem diagnoses.75

In addition to methodological factors, the age of the suicide subjects, geographic location, and gender largely explain the variability between studies. The younger the age at suicide, the higher the likelihood of increased comorbidity, particularly with cluster B personality pathology and substance disorders.54,76 In middle-aged suicide subjects, alcohol and substance use, high anxiety and comorbid major depression disorder are associated with suicide risk,77,78 while older suicide subjects show a stronger association between suicide and psychopathology, particularly in the case of major depressive disorder.79 Geographic origin is another important source of variation, with studies in Western societies showing higher proportions of suicides meeting criteria for psychiatric disorders than studies in samples from Asia,1 where other factors may also contribute to the unique suicide profile. In China, rural areas have threefold higher rates of suicide than urban areas.80 The easy access to highly lethal pesticides, which are the most common method of suicide in China, may contribute to the high rate of fatality for the largely impulsive, low-intent SAs that characterize suicide in rural China; increased lethality of SAs may partly explain why Chinese women, relative to men, have higher rates of suicide fatalities when compared to Western countries.80 In sum, although several factors explain variability among studies in the strength and characteristics of the association between psychopathology and suicide, it is clear that virtually all individuals who intentionally end their lives, regardless of whether or not they meet structured criteria for a psychiatric disorder, show evidence of hopelessness, depressed mood, and SI.

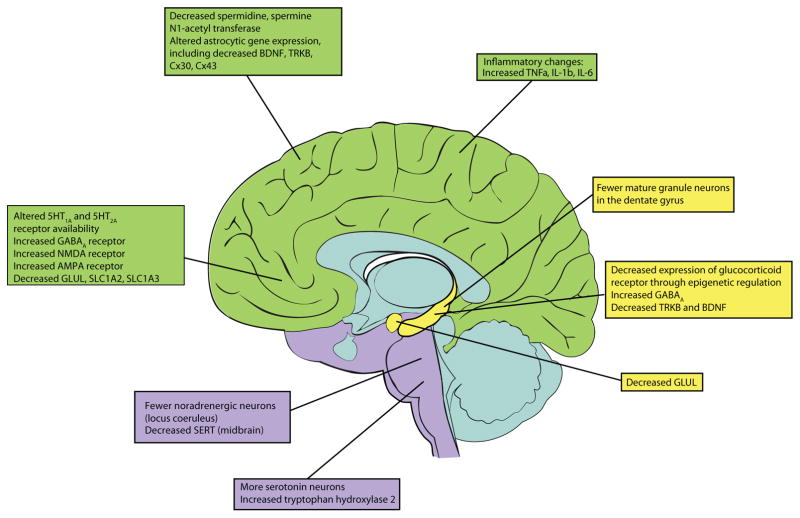

Suicidal states associate with a variety of molecular changes that are detectable both in the periphery and in the brains of suicidal subjects (figure 3).22 Among the first to be described was the altered levels of serotonin and serotonin signalling in suicidal individuals.81 Multiple studies link disrupted serotonin expression to SA or suicide, and despite discrete differences in serotonin receptor and transporter expression between depressed and suicidal patients,82 it remains unclear to what extent altered serotonin signalling in suicides can be distinguished from changes associated with depression due to the frequent co-occurrence of these two phenotypes.83 There is evidence that suicidal individuals have unique serotonin genotype and expression patterns,84,85 and low serotonin is associated with personality traits linked to suicidality, such as impulsive aggression.86 Other neurotransmitters recently implicated in depression and suicide are glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA),87,88 and treatments targeting the glutamate pathway, such as ketamine, have yielded some promising initial results in the treatment of severe depression and SI.89 Aside from known neurotransmitters, inflammatory responses have been linked to SB, with some evidence suggesting that inflammation linked to suicidality may occur both in the central nervous system and in the periphery.90

Figure 3. Biological changes in the suicidal brain.

5HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine, or serotonin; AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; BDNF, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor; Cx, connexin; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GLUL, Glutamine synthetase; IL, interleukin; NMDA, N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid; SERT, serotonin transporter; SLC, solute carrier family; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; TRKB, Tropomyosin receptor kinase B

Consistent with the data available from ELA studies, stress response systems may be altered during suicidal states. Significant alterations of the polyamine system91 and the HPA axis44,92 have been described in the brains of suicide attempters and completers. Altered responses to stressful social situations may lead to psychopathology and SB, with evidence that suicidality is associated with a number of changes in the brains of suicidal patients.93 Glial cell function may also be disrupted in the suicidal brain,94 where astrocyte-specific genes linked to structural integrity are downregulated,95,96 and neurotrophic factors such as the BDNF receptor TRKB show differential expression patterns between suicide completers and controls.49

Other proximal risk factors also play an important role in suicidal risk, either independently or by interacting with psychopathology. Social and physical factors that affect risk of suicide are reviewed in panel 1.97–100

Panel 1. Social and physical factors that affect risk of suicide.

Social factors associated with an increased risk of suicide

Living alone

High introversion

Extreme hopelessness, helplessness and worthlessness, or defeat and entrapment, which may result from depressive psychopathology

Traumatic events in adulthood

Interpersonal stressors

Loss/bereavement: causes emotional distress, can lead to an enduring inability to cope with the loss; complicated grief and development of SI or behaviour is more likely in cases of bereavement due to a violent death such as suicide

Financial or legal difficulties

Physical illnesses with concurrent depression: respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) and asthma (OR=1·5–2·06), cardiovascular diseases such as coronary heart disease and stroke (OR=1·53–1·54), degenerative diseases such as osteoporosis and multiple sclerosis (OR=2·33–2·54); gender differences present, with increased risk for women97,98

Chronic diseases acting independently of mental disorders: inflammatory bowel disease, migraine (HR=1·34)99 and epilepsy (AOR=2·9 when controlling for sociodemographic factors and using sibling controls);100 in the case of epilepsy, SBs may precede onset of seizures and/or may be a sequelae of treatment

Sleep disturbances and insomnia: increased risk of SI or SBs may be independent of depression; may be mediated by increased impulsivity, negative cognitive bias, and reward-seeking

Traumatic brain injury (TBI): athletes and war veterans who have sustained chronic traumatic encephalopathy especially vulnerable; possibly mediated by a decrease in impulse-control following repeated TBIs; lifetime occurrence of psychiatric disorder associated with a greater risk of suicide in TBI victims

Social factors associated with a decreased risk of suicide

Well-developed social support network

Strong reasons for living

Responsibility for young children

Religiosity (frequent attendance of religious service or personal religiosity); may be related to religious views on suicide, or to social support derived from the religious community

Extraversion and optimism

Effective coping and problem solving

Interventions to prevent or treat SB

Prevention

Recent discussions of the efficacy and level of evidence supporting the different prevention practices can be found elsewhere.101–104 School, workplace, and community-based interventions, and multi-component primary care interventions can reduce the incidence of suicide or SB, as can the organization and access to care, and reduced access to lethal means of suicide.

School-based interventions have been found to reduce the incidence of SI or SB. The Good Behavior Game, a teacher-led classroom intervention for first-graders, reduced levels of SI and SB in one of two randomized trials,103 and the SOS program, which educates students about the relationship between mental disorders and suicide, self-identification of depression and suicidal risk, and encourages appropriate help-seeking, also reduced the incidence of SAs.103 A recent, multi-country cluster randomized trial comparing screening and referral, gatekeeper training, and a mental health awareness program similar to the SOS program, found that only the mental health awareness program was associated with a lower incidence of serious SI and SAs.105 Post-high school suicide prevention efforts similarly have found no effect for educational or gatekeeper interventions, but one quasi-experimental study found that method restriction and mandatory professional evaluation of suicidal students reduced the suicide rate.104

A multi-component preventive intervention program in the United States Air Force, including leadership and gatekeeper training, increased access to mental health services, coordination of care for high-risk individuals, and a higher level of confidentiality for those who disclosed suicidality, reduced suicide rates by 35% after implementation.106 Among the elderly, there is some evidence that interventions to decrease isolation and augment social support through activity groups and telephone outreach may also reduce mortality due to suicide.102

A substantial proportion of patients are seen in primary care within one month of suicide, but are rarely diagnosed with a mental disorder.2 Education programs for general practitioners targeting identification and treatment of depression can decrease regional suicide rates, particularly in women, but require continued education and additional physician support to improve patient outcomes.107–109 In particular, supporting physicians via an informational website, increasing liaison between physicians and psychiatric facilities, conducting public education campaigns to train key community facilitators in the recognition of depression and suicide risk, and providing a suicide hotline may all be important aspects of prevention strategies.110 Collaborative care, in which care management for psychiatric disorders is co-located on site in primary care, has been shown to provide significant benefits over usual care in outcomes for depression and anxiety,111 and to improve SI in depressed, older patients.112

Patients recently discharged from psychiatric inpatient units are at extremely high risk for completed suicide. Through decades of research, Appleby and colleagues have identified mental systems level factors that are associated with increased suicide risk, made recommendations for systems change, and evaluated the relationship between regional changes in suicide rate and the level of regional implementation of the recommended systems modifications.113 Declining regional suicide rates are related to the extent of care, clear policies on the management of dual diagnosis patients, and multidisciplinary reviews of suicide deaths.

Means restriction effects are estimated on the basis of before-after or other types of quasi-experimental designs. Means restriction strategies are guided by the assumption that many suicides are impulsive, and increasing access barriers to lethal methods may forestall a suicidal crisis; even if method substitution takes place, the suicidal person will have access to less lethal, potentially non-fatal means of suicide.114 The impact of the availability and regulations that affect availability of a given method for attempting or completing suicide have been examined using case-control studies and cross-regional comparisons of suicide rates and methods over time. The rate of suicide by a given method, whether due to firearms, domestic gas, car exhaust, paracetamol, substitution of lower toxicity medications (e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs] vs. tricyclic antidepressants) pesticides, or jumping from bridges is related to the ease of access.114 Laws that impede access to a given method, whether stricter firearms control laws, detoxification of domestic gas or car exhaust, limitation of access and use of blister packs for paracetamol, lock boxes for pesticides, or bridge barriers (often combined with a telephone hotline for crisis intervention), impact the suicide rate by that method, even though there may be some method substitution over time.114 Brief, individual-level interventions to encourage safe storage can improve the safety of storage, although the impact of these interventions on morbidity or mortality have not been documented.114

Case management and outreach

Panel 2 summarizes the key aspects of detecting and treating SB in patients.115,116 Maintaining active contact to follow-up with suicide attempters presenting to an emergency department (ED) can reduce repetition of SA in the following 12 months (overall RR=0·83, N=5,319),117 as evidenced by two interventions that decreased the suicide rate compared to usual care:118 a large international ED-based intervention that provided follow-up case management and encouragement of adherence resulted in a suicide rate of 0·2% vs. 2·2% (N=1,867), and supportive letters sent to non-adherent suicidal patients discharged from an inpatient unit resulted in a decreased suicide rate within the first two years of the intervention (1·8% vs. 3·52%, N=843). Many studies attempting to replicate the latter findings using postcards for patients engaged in self-poisoning found a reduction in the hazard of repeated overdose.118

Panel 2. Intervention – Detecting and treating SB.

Detecting patients at risk of suicide

Contact with health care services:

Suicide completers and attempters often seek medical help within 12 months of their suicide or SA, most often consulting primary care services.

There is an opportunity for primary health care workers to reach individuals who are contemplating suicide before they act out.

Adolescents are less likely than adults to seek help in the last year and month before suicide:

Despite high prevalence of lifetime contact for emotional or substance-related difficulties, fewer than 20% use services within one year of onset of SB.

More effective outreach programs for youth are required.

Assessing the degree of risk

Often general practitioners do not adequately assess the level of suicide risk at the last visit before their death.

Clinical indicators of suicide risk:

The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale115 is a widely-used measure to establish the degree of suicide risk.

Previous SA and method of SA predicts increased suicide risk.

Suicide completers are likely to have had repeated hospital admissions; recurrence of self-harming is most likely within 3–6 months of first presentation.

Ambivalence, worthlessness, helplessness, and notably, hopelessness are key indicators of heightened suicide risk.

High-risk cases should be followed closely post-discharge.

Diagnosing patients:

Fewer than one-third of suicidal patients express their suicidal intent to their treating healthcare professional.

The Self-Injury–Implicit Association Test116 detects implicit thoughts of DSH, but its sensitivity is limited.

Previous history, presence of risk factors and collateral information can inform physicians about suicide risk.

Particular states, such as mixed state bipolar disorder and psychotic episodes during depression can significantly increase the risk of imminent suicidal acts, and require particular attention.

Defining the level of intervention

Treatment can include initiating pharmacotherapy, behavioural therapy, or referring the patient to specialized care, such as psychological, psychiatric or social therapists or to an emergency department, in case of serious risk of imminent harm.

Any diagnosed psychiatric illness should guide treatment decisions, including selection of pharmacological treatment.

Treatment should be selected based on the patient’s profile and manifestations of B: multidisciplinary interventions strongly based on psychotherapy for chronic SB and more aggressive forms of intervention for acute SB.

Elderly patients manifesting acute SB typically require interventions that guarantee safety, such as hospitalization.

Internet-based applications to monitor patients after discharge and between appointments may be effective methods to improve patient outcomes, although further study is necessary to demonstrate their effectiveness.

Improved coordination between primary and secondary care and frequent post-discharge follow-up are likely to improve patient outcomes.

Somatic treatment options for SB

Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for the pharmacological treatment of depression find that antidepressant treatment decreases SI in individuals 25 years and older.119 Limited evidence suggests that SSRIs result in greater reduction of SI than either venlafaxine or bupropion.120,121 In participants aged 24 and younger, antidepressant treatment results in decreased depressive symptoms, but does not always diminish SI.119 Antidepressant treatment in youth under age 25 is associated with about a 1–2% risk difference in the incidence of suicidal events, i.e., new-onset or worsening SI, or SAs.122 The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States issued a Black Box Warning in 2004 about the possibility of increased suicidality associated with antidepressants in youth, and several other countries followed suit. Following this warning, rates of diagnosis of depression and prescriptions of antidepressants for youth have declined,123 while overdoses of psychotropic medication and suicide among youth have increased.124 Pharmacoepidemiological studies show that sales and prescriptions of SSRIs are inversely correlated with national and regional suicide rates, including in youth.125 The larger size and unselected nature of samples used in pharmacoepidemiological studies, which include high risk patients who typically would be excluded from RCTs, may explain the discrepancy between the apparent protective effect of antidepressant use in pharmacoepidemiological studies and increased incidence of suicidal events reported in youth enrolled in clinical trials.

Besides antidepressants, other pharmacological interventions used in mood disorders have shown some efficacy on SB. Observational studies show that lithium content in water is inversely correlated with regional suicide rates,126 naturalistic treatment studies associate exposure to lithium with a lower suicide and SA rate relative to antiepileptic agents,127,128 and meta-analyses of RCTs support lithium’s protective effect against suicide.129 In 48 RCTs involving 6,674 individuals in both unipolar and bipolar individuals, lithium was associated with a markedly diminished rate of suicide relative to placebo (RR=0·13), and a decreased rate of DSH in lithium vs. carbamazepine.129 Although the exact mechanisms by which lithium may decrease SBs are unknown, it is possible that it may act by reducing mood disorder episodes and/or by decreasing impulsive and aggressive behaviour.130

There is growing enthusiasm for use of ketamine, a glutamatergic agent used as an anaesthetic, to treat SB. Trials using low doses have shown an antidepressant response within minutes of administration in patients with MDD or bipolar disorder.131 Preliminary studies have shown that single and repeated doses of ketamine can reduce SI, making it a promising agent for treatment of the suicidal patient in the ED.89 The main disadvantages of ketamine, however, are its abuse potential, the transient nature of the response, and untoward cardiac and psychotomimetic side effects.

Other classes of drugs also exhibit antisuicidal effects. In the InterSePT RCT, clozapine, an atypical neuroleptic used for treatment-refractory schizophrenia, decreased SAs and emergency referrals for SI compared to olanzapine (RR=0·76) in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder at high risk for SB.132 Naturalistic studies show that patients treated with clozapine have one-third the incidence of completed and attempted suicide compared to patients treated with other antipsychotics.133

In addition to pharmacological interventions, there is also evidence that electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may improve SB. In an open treatment of depressed patients at high suicidal risk, over three-fourths had no suicidal thoughts or intent by 9 ECT sessions, which is consistent with previous studies.134,135 Other neuromodulatory treatments may have similar effects on SI. Preliminary evidence indicates that high doses of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation applied to the left prefrontal cortex may be an effective treatment to rapidly decrease SI.136

Psychotherapeutic interventions for recurrent SB

Most efficacious treatments for SB share a number of common elements: using exploratory interventions to understand the SB and change-oriented interventions to encourage positive, and discourage negative, behaviours; explicitly focusing on SB; having the therapist adopt an active therapeutic stance; planning for coping with suicidal urges; focusing on emotional and cognitive precursors of SB.137

Dialectic Behaviour Therapy (DBT) is probably the most commonly investigated psychotherapy for recurrent SB. DBT has mainly been studied in patients with borderline personality disorder; it promotes self-efficacy, interpersonal effectiveness, and emotional regulation, and has repeatedly been shown to reduce the recurrence of SB relative to treatment as usual (TAU), with more modest differences relative to expert community care.138 DBT is derived from cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), which is also effective in reducing recurrence of SB, with larger effects in adults vs. adolescents, individual vs. group treatment, and when suicidality is an explicit treatment focus.139,140 The psychodynamically-derived mentalization-based therapy (MBT), in which the patient is taught how to conceptualize actions in terms of thoughts and feelings, is also effective in reducing SBs according to two trials in adults with borderline personality disorder.138 For adolescents, a meta-analysis of studies addressing self-harm found an overall effect of treatment vs. TAU, with some of the most promising interventions being CBT, DBT, mentalization, and family therapy; successful interventions were more likely to have a family component and be offered as multiple sessions.141

Perspectives

SBs are heterogeneous, both in terms of presentation and treatment, making it difficult to provide an all-encompassing model of suicide risk or to suggest a clear treatment formula. Due to the complexity and the breadth of the subject, this paper presents an overview of the current state of knowledge in suicide research. Certain aspects, such as detailed discussions of the psychology of suicide and suicide prevention are well described elsewhere.18,142 On-going advances in suicide research are enriching the clinician’s toolbox to manage suicidal patients. Based on clinical trials and natural experiments in pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions, improvements in patient identification and treatment, outreach, and method restriction, there is strong evidence that suicide is a preventable outcome. Greater sensitivity to the potential for SB, continued improvements to public health policy, as well as basic and translational research have the potential to contribute to reducing global suicide rates in the coming years.

Acknowledgments

GT is supported by grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research MOP93775, MOP11260, MOP119429, and MOP119430; from the National Institutes of Health 1R01DA033684 and by the Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Santé through a Chercheur National salary award and through the Quebec Network on Suicide, Mood Disorders and Related Disorders. GT has received investigator-initiated grants from Pfizer Canada, and honoraria from Bristol-Meyers Squibb Canada, Janssen Canada, and Servier. DAB is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Mental Health MH056612, MH100451, and MH104311. DAB receives royalties from Guilford Press, receives royalties from the electronic self-rated version of the C-SSRS from ERT, Inc., and is on the editorial board of UptoDate. The authors are indebted to Sylvanne Daniels for essential help in the preparation of this review.

Footnotes

Contributors

Both authors contributed to the literature search, figures, interpretation and writing of the seminar article.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Contributor Information

Prof. Gustavo Turecki, McGill Group for Suicide Studies, Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Douglas Mental Health University Institute, 6875 Lasalle Blvd, Montreal, QC H4H 1R3, Canada.

Prof. David A. Brent, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. [accessed 5 November 2014];Mental health: suicide prevention. 2014 http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/en/

- 2.Ahmedani BK, Simon GE, Stewart C, et al. Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):870–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2767-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7):1035–43. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.7.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brent DA, Bridge J, Johnson BA, Connolly J. Suicidal behavior runs in families. A controlled family study of adolescent suicide victims. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(12):1145–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120085015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. Lancet. 2009;373(9672):1372–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60372-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spallek J, Reeske A, Norredam M, Nielsen SS, Lehnhardt J, Razum O. Suicide among immigrants in Europe-a systematic literature review. Eur J Public Health. 2014 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King M, Smith A, Gracey M. Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):76–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60827-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):300–10. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borges G, Nock MK, Haro Abad JM, et al. Twelve-month prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(12):1617–28. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04967blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. Prevalence of suicide ideation and suicide attempts in nine countries. Psychol Med. 1999;29(1):9–17. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston AK, Pirkis JE, Burgess PM. Suicidal thoughts and behaviours among Australian adults: findings from the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43(7):635–43. doi: 10.1080/00048670902970874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeon HJ, Lee JY, Lee YM, et al. Lifetime prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation, plan, and single and multiple attempts in a Korean nationwide study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(9):643–6. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ef3ecf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll R, Metcalfe C, Gunnell D. Hospital presenting self-harm and risk of fatal and non-fatal repetition: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brezo J, Paris J, Barker ED, et al. Natural history of suicidal behaviors in a population-based sample of young adults. Psychol Med. 2007;37(11):1563–74. doi: 10.1017/S003329170700058X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conwell Y, Van Orden K, Caine ED. Suicide in older adults. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34(2):451–68. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christodoulou C, Douzenis A, Papadopoulos FC, et al. Suicide and seasonality. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(2):127–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Connor RC, Nock MK. The psychology of suicidal behaviour. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(1):73–85. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mann JJ. Neurobiology of suicidal behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4(10):819–28. doi: 10.1038/nrn1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moscicki EK. Gender differences in completed and attempted suicides. Ann Epidemiol. 1994;4(2):152–8. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE., Jr The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turecki G. The molecular bases of the suicidal brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(12):802–16. doi: 10.1038/nrn3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turecki G, Ernst C, Jollant F, Labonte B, Mechawar N. The neurodevelopmental origins of suicidal behavior. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35(1):14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egeland JA, Sussex JN. Suicide and family loading for affective disorders. JAMA. 1985;254(7):915–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jollant F, Malafosse A, Docto R, Macdonald C. A pocket of very high suicide rates in a non-violent, egalitarian and cooperative population of South-East Asia. Psychol Med. 2014:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713003176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fountoulakis KN, Kawohl W, Theodorakis PN, et al. Relationship of suicide rates to economic variables in Europe: 2000–2011. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(6):486–96. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeves A, McKee M, Stuckler D. Economic suicides in the Great Recession in Europe and North America. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(3):246–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.144766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pirkis J, Nordentoft M. Media influences on suicide and attempted suicide. In: O’Connor RC, Platt S, Gordon J, editors. International handbook of suicide prevention: research, policy and practice. Chichester; Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. pp. 531–44. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gould MS. Suicide and the media. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;932:200–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05807.x. discussion 21–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim CD, Seguin M, Therrien N, et al. Familial aggregation of suicidal behavior: a family study of male suicide completers from the general population. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(5):1017–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tidemalm D, Runeson B, Waern M, et al. Familial clustering of suicide risk: a total population study of 11. 4 million individuals. Psychol Med. 2011;41(12):2527–34. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brent DA, Melhem N. Familial transmission of suicidal behavior. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(2):157–77. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulsinger F, Kety SS, Rosenthal D, Wender PH. A family study of suicide. In: Schou M, Strömgren E, editors. Origin, Prevention and Treatment of Affective Disorders. London: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 277–87. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGirr A, Alda M, Seguin M, Cabot S, Lesage A, Turecki G. Familial aggregation of suicide explained by cluster B traits: a three-group family study of suicide controlling for major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(10):1124–34. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08111744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Statham DJ, Heath AC, Madden PA, et al. Suicidal behaviour: an epidemiological and genetic study. Psychol Med. 1998;28(4):839–55. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu Q, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, et al. A twin study of genetic and environmental influences on suicidality in men. Psychol Med. 2002;32(1):11–24. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lieb R, Bronisch T, Hofler M, Schreier A, Wittchen HU. Maternal suicidality and risk of suicidality in offspring: findings from a community study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(9):1665–71. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, et al. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. J Homosex. 2011;58(1):10–51. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Risk factors and life processes associated with the onset of suicidal behaviour during adolescence and early adulthood. Psychol Med. 2000;30(1):23–39. doi: 10.1017/s003329179900135x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brezo J, Paris J, Vitaro F, Hebert M, Tremblay RE, Turecki G. Predicting suicide attempts in young adults with histories of childhood abuse. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(2):134–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.037994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Afifi TO, Enns MW, Cox BJ, Asmundson GJ, Stein MB, Sareen J. Population attributable fractions of psychiatric disorders and suicide ideation and attempts associated with adverse childhood experiences. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(5):946–52. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Melhem NM, Brent DA, Ziegler M, et al. Familial pathways to early-onset suicidal behavior: familial and individual antecedents of suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1364–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heim C, Shugart M, Craighead WE, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiological and psychiatric consequences of child abuse and neglect. Dev Psychobiol. 2010;52(7):671–90. doi: 10.1002/dev.20494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D’Alessio AC, et al. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(3):342–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turecki G, Meaney MJ. Effects of the Social Environment and Stress on Glucocorticoid Receptor Gene Methylation: A Systematic Review. Biol Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weder N, Zhang H, Jensen K, et al. Child abuse, depression, and methylation in genes involved with stress, neural plasticity, and brain circuitry. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(4):417–24. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Labonte B, Suderman M, Maussion G, et al. Genome-wide epigenetic regulation by early-life trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(7):722–31. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roth TL, Lubin FD, Funk AJ, Sweatt JD. Lasting epigenetic influence of early-life adversity on the BDNF gene. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(9):760–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ernst C, Deleva V, Deng X, et al. Alternative splicing, methylation state, and expression profile of tropomyosin-related kinase B in the frontal cortex of suicide completers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(1):22–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.66.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keller S, Sarchiapone M, Zarrilli F, et al. Increased BDNF promoter methylation in the Wernicke area of suicide subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):258–67. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pedersen MG, Mortensen PB, Norgaard-Pedersen B, Postolache TT. Toxoplasma gondii infection and self-directed violence in mothers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(11):1123–30. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arling TA, Yolken RH, Lapidus M, et al. Toxoplasma gondii antibody titers and history of suicide attempts in patients with recurrent mood disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(12):905–8. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181c29a23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Flegr J. How and why Toxoplasma makes us crazy. Trends Parasitol. 2013;29(4):156–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McGirr A, Renaud J, Bureau A, Seguin M, Lesage A, Turecki G. Impulsive-aggressive behaviours and completed suicide across the life cycle: a predisposition for younger age of suicide. Psychol Med. 2008;38(3):407–17. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seguin M, Beauchamp G, Robert M, DiMambro M, Turecki G. Developmental model of suicide trajectories. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(2):120–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.139949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wanner B, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE, Turecki G. Childhood trajectories of anxiousness and disruptiveness explain the association between early-life adversity and attempted suicide. Psychol Med. 2012:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brent DA, Melhem NM, Oquendo M, et al. Familial pathways to early-onset suicide attempt: a 5. 6-year prospective study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):160–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang B, Clum GA. Childhood stress leads to later suicidality via its effect on cognitive functioning. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2000;30(3):183–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sinclair JM, Crane C, Hawton K, Williams JM. The role of autobiographical memory specificity in deliberate self-harm: correlates and consequences. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1–3):11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scott KM, McLaughlin KA, Smith DA, Ellis PM. Childhood maltreatment and DSM-IV adult mental disorders: comparison of prospective and retrospective findings. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(6):469–75. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.103267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee FS, Heimer H, Giedd JN, et al. Mental health. Adolescent mental health--opportunity and obligation. Science. 2014;346(6209):547–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1260497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van den Bos R, Harteveld M, Stoop H. Stress and decision-making in humans: performance is related to cortisol reactivity, albeit differently in men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(10):1449–58. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Williams JM, Barnhofer T, Crane C, Beck AT. Problem solving deteriorates following mood challenge in formerly depressed patients with a history of suicidal ideation. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114(3):421–31. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McGirr A, Diaconu G, Berlim MT, et al. Dysregulation of the sympathetic nervous system, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and executive function in individuals at risk for suicide. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2010;35(6):399–408. doi: 10.1503/jpn.090121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grover KE, Green KL, Pettit JW, Monteith LL, Garza MJ, Venta A. Problem solving moderates the effects of life event stress and chronic stress on suicidal behaviors in adolescence. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(12):1281–90. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arsenault-Lapierre G, Kim C, Turecki G. Psychiatric diagnoses in 3275 suicides: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hoertel N, Franco S, Wall MM, et al. Mental disorders and risk of suicide attempt: a national prospective study. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(6):718–26. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Holma KM, Haukka J, Suominen K, et al. Differences in incidence of suicide attempts between bipolar I and II disorders and major depressive disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(6):652–61. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Angst F, Stassen HH, Clayton PJ, Angst J. Mortality of patients with mood disorders: follow-up over 34–38 years. J Affect Disord. 2002;68(2–3):167–81. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sharifi V, Eaton WW, Wu LT, Roth KB, Burchett BM, Mojtabai R. Psychotic experiences and risk of death in the general population: 24–27 year follow-up of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Br J Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.143198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hor K, Taylor M. Suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4 Suppl):81–90. doi: 10.1177/1359786810385490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(8):868–76. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tyrer P, Reed GM, Crawford MJ. Classification, assessment, prevalence, and effect of personality disorder. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):717–26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61995-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ernst C, Lalovic A, Lesage A, Seguin M, Tousignant M, Turecki G. Suicide and no axis I psychopathology. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Conner KR, Beautrais AL, Brent DA, Conwell Y, Phillips MR, Schneider B. The next generation of psychological autopsy studies. Part I. Interview content. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2011;41(6):594–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim C, Lesage A, Seguin M, et al. Patterns of co-morbidity in male suicide completers. Psychol Med. 2003;33(7):1299–309. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Akechi T, Iwasaki M, Uchitomi Y, Tsugane S. Alcohol consumption and suicide among middle-aged men in Japan. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:231–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Park JE, Lee JY, Jeon HJ, et al. Age-related differences in the influence of major mental disorders on suicidality: a Korean nationwide community sample. J Affect Disord. 2014;162:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Cox C, Herrmann JH, Forbes NT, Caine ED. Relationships of age and axis I diagnoses in victims of completed suicide: a psychological autopsy study. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(8):1001–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Phillips MR, Yang G, Zhang Y, Wang L, Ji H, Zhou M. Risk factors for suicide in China: a national case-control psychological autopsy study. Lancet. 2002;360(9347):1728–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11681-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Asberg M, Thoren P, Traskman L, Bertilsson L, Ringberger V. Serotonin depression -- a biochemical subgroup within the affective disorders. Science. 1976;191(4226):478–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1246632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Arango V, Underwood MD, Mann JJ. Serotonin brain circuits involved in major depression and suicide. Prog Brain Res. 2002;136:443–53. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)36037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mann JJ. The serotonergic system in mood disorders and suicidal behaviour. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368(1615):20120537. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sullivan GM, Oquendo MA, Milak M, et al. Positron Emission Tomography Quantification of Serotonin1A Receptor Binding in Suicide Attempters With Major Depressive Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brezo J, Bureau A, Merette C, et al. Differences and similarities in the serotonergic diathesis for suicide attempts and mood disorders: a 22-year longitudinal gene-environment study. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(8):831–43. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yanowitch R, Coccaro EF. The neurochemistry of human aggression. Adv Genet. 2011;75:151–69. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380858-5.00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sequeira A, Mamdani F, Ernst C, et al. Global brain gene expression analysis links glutamatergic and GABAergic alterations to suicide and major depression. PLoS One. 2009;4(8):e6585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Choudary PV, Molnar M, Evans SJ, et al. Altered cortical glutamatergic and GABAergic signal transmission with glial involvement in depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(43):15653–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507901102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rajkumar R, Fam J, Yeo EY, Dawe GS. Ketamine and suicidal ideation in depression: Jumping the gun? Pharmacol Res. 2015;99:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Black C, Miller BJ. Meta-analysis of Cytokines and Chemokines in Suicidality: Distinguishing Suicidal Versus Nonsuicidal Patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Turecki G. Polyamines and suicide risk. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(12):1242–3. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nemeroff CB, Owens MJ, Bissette G, Andorn AC, Stanley M. Reduced corticotropin releasing factor binding sites in the frontal cortex of suicide victims. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(6):577–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800300075009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.van Heeringen K, Mann JJ. The neurobiology of suicide. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(1):63–72. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rajkowska G. Postmortem studies in mood disorders indicate altered numbers of neurons and glial cells. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(8):766–77. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00950-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bernard R, Kerman IA, Thompson RC, et al. Altered expression of glutamate signaling, growth factor, and glia genes in the locus coeruleus of patients with major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(6):634–46. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ernst C, Nagy C, Kim S, et al. Dysfunction of Astrocyte Connexins 30 and 43 in Dorsal Lateral Prefrontal Cortex of Suicide Completers. Biol Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bolton JM, Walld R, Chateau D, Finlayson G, Sareen J. Risk of suicide and suicide attempts associated with physical disorders: a population-based, balancing score-matched analysis. Psychol Med. 2014:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Webb RT, Kontopantelis E, Doran T, Qin P, Creed F, Kapur N. Suicide risk in primary care patients with major physical diseases: a case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):256–64. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ilgen MA, Kleinberg F, Ignacio RV, et al. Noncancer pain conditions and risk of suicide. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(7):692–7. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fazel S, Wolf A, Langstrom N, Newton CR, Lichtenstein P. Premature mortality in epilepsy and the role of psychiatric comorbidity: a total population study. Lancet. 2013;382(9905):1646–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60899-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nordentoft M. Crucial elements in suicide prevention strategies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(4):848–53. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lapierre S, Erlangsen A, Waern M, et al. A systematic review of elderly suicide prevention programs. Crisis. 2011;32(2):88–98. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Katz C, Bolton SL, Katz LY, et al. A systematic review of school-based suicide prevention programs. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(10):1030–45. doi: 10.1002/da.22114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Harrod CS, Goss CW, Stallones L, DiGuiseppi C. Interventions for primary prevention of suicide in university and other post-secondary educational settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;10:CD009439. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009439.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wasserman D, Hoven CW, Wasserman C, et al. School-based suicide prevention programmes: the SEYLE cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Knox KL, Pflanz S, Talcott GW, et al. The US Air Force suicide prevention program: implications for public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2457–63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rutz W, von Knorring L, Walinder J. Long-term effects of an educational program for general practitioners given by the Swedish Committee for the Prevention and Treatment of Depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;85(1):83–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb01448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Szanto K, Kalmar S, Hendin H, Rihmer Z, Mann JJ. A suicide prevention program in a region with a very high suicide rate. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(8):914–20. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sikorski C, Luppa M, Konig HH, van den Bussche H, Riedel-Heller SG. Does GP training in depression care affect patient outcome?- A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Szekely A, Konkoly Thege B, Mergl R, et al. How to decrease suicide rates in both genders? An effectiveness study of a community-based intervention (EAAD) PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e75081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Bruce ML, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(8):882–90. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.While D, Bickley H, Roscoe A, et al. Implementation of mental health service recommendations in England and Wales and suicide rates, 1997–2006: a cross-sectional and before-and-after observational study. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1005–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61712-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yip PS, Caine E, Yousuf S, Chang SS, Wu KC, Chen YY. Means restriction for suicide prevention. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2393–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60521-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nock MK, Banaji MR. Assessment of self-injurious thoughts using a behavioral test. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(5):820–3. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.5.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Inagaki M, Kawashima Y, Kawanishi C, et al. Interventions to prevent repeat suicidal behavior in patients admitted to an emergency department for a suicide attempt: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2014;175C:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Luxton DD, June JD, Comtois KA. Can postdischarge follow-up contacts prevent suicide and suicidal behavior? A review of the evidence. Crisis. 2013;34(1):32–41. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Davis J, Mann JJ. Suicidal thoughts and behavior with antidepressant treatment: reanalysis of the randomized placebo-controlled studies of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(6):580–7. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Vitiello B, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Long-term outcome of adolescent depression initially resistant to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment: a follow-up study of the TORDIA sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):388–96. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05885blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Grunebaum MF, Ellis SP, Duan N, Burke AK, Oquendo MA, John Mann J. Pilot randomized clinical trial of an SSRI vs bupropion: effects on suicidal behavior, ideation, and mood in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(3):697–706. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Stone M, Laughren T, Jones ML, et al. Risk of suicidality in clinical trials of antidepressants in adults: analysis of proprietary data submitted to US Food and Drug Administration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2880. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Libby AM, Orton HD, Valuck RJ. Persisting decline in depression treatment after FDA warnings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(6):633–9. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lu CY, Zhang F, Lakoma MD, et al. Changes in antidepressant use by young people and suicidal behavior after FDA warnings and media coverage: quasi-experimental study. BMJ. 2014;348:g3596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ludwig J, Marcotte DE, Norberg K. Anti-depressants and suicide. J Health Econ. 2009;28(3):659–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Vita A, De Peri L, Sacchetti E. Lithium in drinking water and suicide prevention: a review of the evidence. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30(1):1–5. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sondergard L, Lopez AG, Andersen PK, Kessing LV. Mood-stabilizing pharmacological treatment in bipolar disorders and risk of suicide. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(1):87–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Goodwin FK, Fireman B, Simon GE, Hunkeler EM, Lee J, Revicki D. Suicide risk in bipolar disorder during treatment with lithium and divalproex. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1467–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.11.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cipriani A, Hawton K, Stockton S, Geddes JR. Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3646. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.O’Donnell KC, Gould TD. The behavioral actions of lithium in rodent models: leads to develop novel therapeutics. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31(6):932–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Fond G, Loundou A, Rabu C, et al. Ketamine administration in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014;231(18):3663–76. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3664-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, et al. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(1):82–91. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]