Abstract

Research suggests an important role of the eyes and mouth for discriminating facial expressions of emotion. A gaze-contingent procedure was used to test the impact of fixation to facial features on the neural response to fearful, happy and neutral facial expressions in an emotion discrimination (Exp.1) and an oddball detection (Exp.2) task. The N170 was the only eye-sensitive ERP component, and this sensitivity did not vary across facial expressions. In both tasks, compared to neutral faces, responses to happy expressions were seen as early as 100–120ms occipitally, while responses to fearful expressions started around 150ms, on or after the N170, at both occipital and lateral-posterior sites. Analyses of scalp topographies revealed different distributions of these two emotion effects across most of the epoch. Emotion processing interacted with fixation location at different times between tasks. Results suggest a role of both the eyes and mouth in the neural processing of fearful expressions and of the mouth in the processing of happy expressions, before 350ms.

1. Introduction

Facial expressions of emotion (hereafter facial emotions or facial expressions) are particularly salient stimuli and are direct indicators of others’ affective dispositions and intentions (Adolphs, 2003). The ability to quickly extract facial information and discriminate between facial emotions is crucial for proper social communication (e.g., discerning a friend from foe; Mehrabian, 1968) and the neural correlates of these cognitive processes have been studied extensively using various neuroimaging techniques. Scalp Event Related Potentials (ERPs) are well suited to study the temporal dynamics of neuro-cognitive events and have been used to examine the time course of facial expression processing. However, results remain inconsistent (Rellecke, Sommer, & Schact, 2013; and see Vuilleumier & Pourtois, 2007, for a review).

1.1 Early Event-Related Potentials in facial expression research

The first visual ERP investigated in facial emotion research is the visual P1, (~80–120ms post-stimulus onset at occipital sites), a component known to be sensitive to attention (Luck, 1995; Luck, Woodman, & Vogek, 2000; Mangun, 1995) and low-level stimulus properties such as colour, contrast and luminance (Johannes, Münte, Heinze & Mangun, 1995; Rossion & Jacques, 2008, 2012). A growing number of studies have now reported enhanced P1 amplitude for fearful relative to neutral faces (e.g., Batty & Taylor, 2003; Pourtois, Grandjean, Sander, & Vuilleumier, 2004; Sato, Kochiyama, Yoshikawa & Matsumura, 2001; Smith, Weinberg, Moran, & Jajcak, 2013; Wijers & Banis, 2012). It has been suggested that early occipito-temporal visual areas could be activated to a larger extent by intrinsically salient, threat-related stimuli, via possible projections from a subcortical route involving the amygdala (Vuilleumier & Pourtois, 2007). Fearful faces would automatically engage this subcortical structure which, in turn, would modulate and enhance cortical processing of the face stimuli (Morris et al., 1998; Vuilleumier, Richardson, Armony, Driver, & Dolan, 2004; Whalen et al., 1998). Because of P1 early timing, which corresponds to the activation of early extrastriate visual areas (e.g. V2, V3, posterior fusiform gyrus, e.g. Clark, Fan, & Hillyard, 1995), this P1 fear effect is thought to reflect a coarse emotion extraction, the “threat gist” (e.g., Luo, Feng, He, Wang, & Lu, 2010; Vuilleumier & Poutois, 2007), that might rely on fast extraction of low spatial frequencies (Vuilleumier, Armony, Driver, & Dolan, 2003). Actual processing of the visual threat would occur later, around or after the N170 (e.g., Luo et al., 2010), the second ERP component studied in facial expression research. However, let’s note that this early P1 modulation by emotion is debated as many studies also failed to report modulations of the P1 by facial expressions of emotion (see Vuilleumier & Pourtois, 2007 for a review).

The N170 is a negative-going face-sensitive component measured at lateral occipito-temporal electrodes ~130–200ms post stimulus onset, and is considered to index the structural processing of the face, i.e. a stage where features are integrated into the whole percept of a face (Bentin & Deouell, 2000; Bentin, Allison, Puce, Perez, & McCarthy, 1996; Itier & Taylor, 2002; Rossion et al., 2000). Studies have suggested the involvement of the fusiform gyrus (e.g. Itier & Taylor, 2002; Rossion et al., 1999), the Superior Temporal Sulcus (e.g. Itier & Taylor, 2004) and the Inferior Occipital Gyrus, or their combination, as potential generators of the N170 (for a review see Rossion & Jacques, 2012). Reports of the N170 sensitivity to facial emotions have been inconsistent. A number of studies have reported emotion effects with larger N170 recorded in response to emotional faces, especially fearful expressions, compared to neutral faces (e.g., Batty & Taylor, 2003; Blau, Maurer, Tottenham, & McCandliss, 2007; Caharel, Courtay, Bernard, Lalonde, 2005; Leppänen, Hietanen, & Koskinen, 2008; Leppänen, Moulson, Vogel-Farley, & Nelson, 2007; also see Hinojosa, Mercado, & Carretié, 2015). However, as seen for the P1, a lack of sensitivity to facial expressions of emotion has also been reported for the N170 component in many studies (e.g., Ashley, Vuilleumier, & Swick, 2004; Balconi & Lucchiari, 2005; Herrmann et al., 2002; Krolak-Salmon, Fischer, Vighetto, & Mauguière, 2001; Münte et al., 1998; Pourtois, Dan, Granjean, Sander, & Vuilleumier, 2005; Shupp, Junghöfer, Weike, & Hamm, 2004; Smith et al., 2013). Therefore it remains unclear whether facial expression processing, in particular that of fearful faces, interacts with the processing of the face structure, as indexed by the N170.

Another well studied ERP in facial expression research is the well-known marker of emotion processing Early Posterior Negativity (EPN), a negative deflection measured over temporo-occipital sites ~150–350ms post-stimulus onset. The EPN is enhanced for emotional relative to neutral stimuli, for both verbal and non-verbal material including faces (Schacht & Sommer, 2009; Schupp Markus, Weike, & Hamm, 2003; Schupp et al., 2004; Rellecke et al., 2013). Like the N170, the EPN is commonly reported to be most pronounced for threat-related expressions (i.e., fearful and angry) compared to neutral and happy expressions (e.g., Schupp et al., 2004; Rellecke, Palazova, Sommer, & Schacht, 2011), although there are reports of a general emotion effect with more negative amplitudes for both threatening and happy expressions compared to neutral expressions (Sato et al., 2001; Schupp, Flaisch, Stockburger, & Junghöfer, 2006). Therefore this effect has been suggested to reflect enhanced processing of emotionally salient faces in general or of threatening faces in particular (i.e., fearful and angry) in temporo-occipital areas possibly including occipital gyrus, fusiform gyrus and Superior Temporal Sulcus regions (Schupp et al., 2004). The current view is that the EPN reflects more in depth appraisal of the emotion, some form of semantic stage where the meaning of the emotion is extracted (Luo et al., 2010; Vuilleumier & Pourtois, 2007). Some studies have suggested that the EPN reflects the neural activity related to the processing of the emotion that is superimposed onto the normal processing of the face. This superimposed activity would sometimes start around the N170 and be responsible for the emotional effects reported for the N170 (Leppänen et al., 2008; Rellecke et al., 2011; 2013; Schupp et al., 2004), although it seems largest after the N170 peak and around the visual P2 (see Neath & Itier, 2015, for a recent example). In other words, the emotion effect on the N170 would actually reflect superimposed EPN activity (Rellecke et al., 2011; Rellecke, Sommer, & Schacht, 2012; Schacht & Sommer, 2009). According to this interpretation, face structural encoding, as indexed by the N170, and facial emotion encoding, do not really interact and are separate processes that occur independently and in parallel, as proposed by classic cognitive and neural models of face processing (Bruce & Young, 1986; Haxby, Hoffman, & Gobbini, 2000).

1.2 Role of facial features in the processing of facial expression

One factor possibly contributing to these inconsistent early ERP effects of emotion is the differing amount of attention to facial features. Some features characterize particular facial expressions better than others, like the smiling mouth for happy faces and the wide open eyes for fearful faces (e.g., Kohler et al., 2004; Leppänen & Hietanen, 2007; Nusseck, Cunningham, Wallraven, & Bülthoff, 2008; Smith, Cottrell, Gosselin, & Schyns, 2005). Behavioural research presenting face parts (e.g., Calder, Young, Keane, & Dean,2000) or using response classification techniques such as Bubbles (e.g., Blais, Roy, Fiset, Arguin, & Gosselin, 2012; Smith et al., 2005) has highlighted the importance of these so-called “diagnostic features” for the discrimination and categorization of these facial emotions. Eye-tracking research also supports the idea that attention is drawn to these features early on, as revealed by spontaneous saccades towards the eyes of fearful faces or the mouth of happy faces presented for as short as 150ms (Gamer, Schmitz, Tittgemeyer, & Schilbach, 2013; Scheller, Büchel, & Gamer, 2012).

The role of these diagnostic features in the neural response to facial expressions has recently been investigated in ERP research but remains unclear. Research using the Bubbles technique in combination with ERP recordings has suggested that the eye region provides the most useful diagnostic information for the discrimination of fearful facial expressions and the mouth for the discrimination of happy facial expressions, and that the N170 peaks when these diagnostic features are encoded (Schyns, Petro, & Smith,2007, 2009). Leppänen et al. (2008) reported that an early fear effect, seen as more negative amplitudes for fearful compared to neutral faces from the peak of the N170 (~160ms in that study) until 260ms (encompassing the visual P2 and EPN), was eliminated when the eye region was covered, demonstrating the importance of this facial area in the neural response to fearful expressions. Calvo and Beltrán (2014) reported hemispheric differences in the processing of facial expressions using face parts and whole faces. An enhanced N170 in the left hemisphere was seen for happy compared to angry, surprised and neutral faces for the bottom face region presented in isolation (including the mouth), but not for the top face region presented in isolation (including the eyes), or for the presentation of the whole face. In the right hemisphere in contrast, the N170 was enhanced for angry compared to happy, surprised and neutral faces for whole faces only.

Taken together these studies suggest that the expression-specific diagnostic features modulate the neural response to facial expression at the level of the N170 or later. Importantly, all these ERP studies have employed techniques that forced feature-based processing by revealing facial information through apertures of various sizes and spatial frequencies (e.g. Bubbles, Schyns et al., 2007, 2009), by presenting isolated face parts (Calvo & Beltrán, 2014; Leppänen et al., 2008) or by covering portions of the face (Leppänen et al., 2008). However the bulk of the literature on face perception supports the idea that faces are processed holistically, i.e. as a whole, whether the focus is on identity (McKone, 2008; Rossion & Jacques, 2008) or emotion (Calder & Jansen, 2005; Calder et al., 2000) recognition. Moreover, components such as the N170 are very sensitive to disruption of this holistic processing (Rossion & Jacques, 2012; Itier, 2015, for reviews). A systematic investigation of the impact of facial features on the neural processing of facial emotion in the context of the whole face is lacking. This is important given we almost invariably encounter whole faces in our daily social interactions, and eye tracking studies suggest that faces are explored and that fixation moves across facial features, with a larger exploration of the eyes (see Itier, 2015, for a review).

Using an eye-tracker and a gaze-contingent procedure to ensure fixation on specific facial features of fearful, happy, and neutral expressions, Neath and Itier (2015) recently reported different spatio-temporal emotion effects for happy and fearful faces. Smaller amplitudes for happy than neutral faces were seen mainly at occipital sites, starting on the P1 and most pronounced around 120ms, followed by a sustained effect until 350ms post-stimulus onset. Fearful faces elicited smaller amplitudes than neutral faces mainly at lateral-posterior sites, first transiently around 80ms on the left hemisphere only, and then bilaterally starting at 150ms, i.e. right after the N170 peak, until 300ms. The N170 peak itself was not significantly modulated by emotion. These main effects of emotion interacted with fixation location at occipital sites only during 150–200ms, with smaller amplitudes for both happy and fearful faces compared to neutral faces, seen only when fixation was on the mouth (no emotion effects were seen for fixation on the eyes or the nose). Although limited temporally, these interactions between emotion and fixation location suggested a possibly important role of the mouth in processing happy but perhaps also fearful faces, while fixation to the eyes did not yield specific effects for the processing of fearful faces.

The present study

The Neath and Itier (2015) study employed a gender discrimination task, which was emotion-irrelevant. However, the diagnostic feature hypothesis suggests that different features might be used depending on task demands ((Schyns, Jentzsch, Johnson, Schweinberger, & Gosselin, 2003; Schyns et al., 2007, 2009;; Smith & Merlusca, 2014). The goal of the current study was to follow-up on the Neath and Itier’s study to investigate the impact of fixation to facial features on the neural processing of facial emotions in the context of the whole face, during an explicit emotion discrimination (ED) task (Experiment 1) and during another emotion-irrelevant task (oddball detection (ODD) task, Experiment 2).

In the present study, fearful, happy and neutral faces were presented with fixation to the left eye, right eye, nose and mouth using the same gaze-contingent design as Neath and Itier (2015). That is, the stimulus was presented only when an eye–tracker detected that the fixation cross was fixated for a certain amount of time. A face stimulus was then presented offset so as to put the desired feature in fovea, at the location of the fixation cross. We expected to replicate the findings of Neath and Itier (2015) regarding low-level stimulus position effects on the P1, as well as the larger N170 amplitude for fixation to the eyes compared to the nose and mouth (see also de Lissa et al., 2014; Nemrodov, Anderson, Preston, & Itier, 2014). We also hoped to reproduce their distinct spatio-temporal pattern of fear and happiness effects. We expected that the different task demands would impact the fixation and emotion interactions such that, for the explicit emotion discrimination task, an enhanced fear effect would be seen for fixation to the eyes compared to the nose or mouth and a larger happiness effect would be seen for fixation to the mouth compared to the eyes or nose, given the respective diagnosticity of these features for the two emotions. If diagnostic features are tied to explicit emotion discrimination, this interaction should not be seen, or should be different, in the oddball task. The interactions were expected around the timing of the N170 or later, during the timing coinciding with the EPN.

2. Experiment 1- Explicit emotion discrimination (ED) task

2.1 Methods

2.1.1. Participants

Forty-seven undergraduate students from the University of Waterloo (UW) were recruited and received course credit for their participation. All participants lived in North America for at least 10 years and they all reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision, no history of head-injury or neurological disease, and were not taking any medication. They all signed informed written consent and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at UW. At the start of the study, calibration of the eye tracker failed for 8 participants who were not further tested. The remaining 39 participants were tested but 19 were rejected for the following reasons. One participant completed less than half of the study; four were removed due to artefacts resulting in many conditions with fewer than our 40 trials per condition cut-off (50% of the initial trials per condition); 13 had too few trials after removing trials with eye movements outside of our defined fixation location interest area of 1.4° of visual angle (see below)1; one participant was rejected due to problems during EEG recordings. The results from 20 participants were kept in the final analysis (21 ± 3.1 years, all right-handed, 10 females).

2.1.2. Stimuli

Images were fearful, happy and neutral facial expressions of 4 males and 4 females from the MacBrain Face Stimulus Set2 (“NimStim faces”, Tottenham et al., 2009) (see Fig. 1A for examples of expressions). Images were converted to greyscale in Adobe™ Photoshop CS5 and an elliptical mask was applied so hair, ears, shoulders and other non-face items (e.g., earrings) were not visible. The faces subtended 6.30° horizontally and 10.44° vertically when viewed from a distance of 70cm and were presented on a grey background for an image visual angle of 9.32° horizontally and 13.68° vertically. The grey images were presented on a white computer monitor. No significant differences in mean RMS contrast and mean normalized pixel intensity were seen between the three emotion categories (RMS: Mfearful = .33 (.01 S.D); Mhappy= .34 (.01 S.D); Mneutral = .34 (.01 S.D); pixel intensity: Mfearful = .58 (.01 S.D); Mhappy= .57 (.01 S.D); Mneutral = .57 (.01 S.D); all t-tests at p > 0.05 using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons).

Figure 1.

A Left panel: Examples of fearful and happy expressions (and flowers for Exp. 2 only), with fixation crosses overlaid on the face to indicate where the fixation would occur (note that fixation crosses were never presented on faces in the actual experiment). Right panel: Participants fixated in the center of the screen represented here by the white rectangle (neutral expression example) and the face was offset in such a way that gaze fixated four possible fixation locations: left eye, right eye, nose and mouth. Note that eye positions are from a viewer perspective (i.e., left eye is on the left of the picture). B. Trial example with right eye fixation and fearful expression. First a fixation point was displayed on the screen for a jittered amount of time (0–107ms) with an additional fixation trigger of 307ms. A grayscale picture was then flashed for 257ms. In Exp. 1 (Explicit Discrimination – ED), a response screen immediately followed the stimulus and displayed a vertical list of emotions; participants selected, using a mouse, the correct emotion label that the face was expressing. The response screen remained until the participant’s response, followed by a blink screen for 307ms. In Exp. 2 (Oddball –ODD-task) the stimulus was followed by a fixation cross that was presented for 747ms for face trials or until response for flower trials.

To ensure that participants fixated on specific facial features, fixation locations corresponding to the left eye, right eye, nose and mouth for each face stimulus were calculated. Left and right sides are from a participant’s perspective such that the left eye means the eye situated on the left side of the participant and the right eye, the eye situated on the right side of the participant. The locations of the nose and mouth fixations were determined by aligning them along an axis passing through the middle of the nose and face, and the locations of the eye fixations were on the center of the pupil. A fixation-cross at the centre of the screen was always used followed by the face presented offset so the predetermined center of each feature would land on the center of that fixation-cross (see Fig. 1A). Due to variations in the coordinates for each identity and the three expressions used, all pictures were presented in slightly different locations3.

For each picture, the mean normalized pixel intensity (PI) and RMS contrast were also calculated for the pre-defined Interest Areas (IA) of 1.4° diameter centered on fixation locations that ensured foveal vision on each facial feature with no overlap. Mean PI and RMS contrast were analyzed using a 3 (emotion) X 4 (IA) repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA). The highest RMS contrast was seen for the left and right eyes IA (which did not significantly differ), followed by the mouth and then the nose IA (which did not significantly differ; effect of fixation location, F(1.34, 9.40) = 16.34, p < .001, ηp2 = .70, all paired comparisons at p-values < .05; see Table 1). However, the emotion by fixation location interaction (F(2.74, 19.18) = 11.48, p < .001, ηp2 = .62) revealed different emotion differences for each fixation location analyzed separately. For the left eye IA, a larger contrast was seen for neutral compared to happy faces (F = 9.70, p < .01) and contrast was also larger for both fearful and happy compared to neutral faces for the mouth IA (F = 11.52, p < .01). No emotion differences were seen for the nose IA (p = .12) and an effect of emotion was seen for the right eye IA (F = 4.97, p < .05) but no significant pairwise comparisons were found.

Table 1.

Pixel intensity and RMS contrast values within 1.4° radius centered on the left eye, right eye, nose and mouth for the fearful, happy and neutral expressions used in both experiments (standard errors to the means in parenthesis). Values for whole pictures can be found in the text.

| Mean pixel intensity (std error) | Mean RMS Contrast (std error) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Left Eye | Right Eye | Nose | Mouth | Left Eye | Right Eye | Nose | Mouth | |

| Fear | .43 (.02) | .44 (.04) | .52 (.02) | .49 (.03) | .14 (.01) | .14 (.01) | .12 (.01) | .13 (.02) |

| Happy | .44 (.03) | .44 (.03) | .51 (.02) | .55 (.02) | .13 (.01) | .14 (.02) | .11 (.01) | .13 (.01) |

| Neutral | .43 (.03) | .43 (.02) | .51 (.03) | .50 (.02) | .14 (.03) | .14 (.01) | .11 (.01) | .10 (.01) |

The lowest PI was seen for the left and right eyes IA (which did not significantly differ), followed by the mouth and the nose IA (which did not significantly differ; effect of fixation location, F(1.77, 12.36) = 42.29, p < .001, ηp2 = .86, all paired comparisons at p-values < .01). The emotion by IA interaction was also significant (F(2.54,17.81) = 6.79, p < .05, ηp2 = .49). No differences between emotions were seen for the left eye (p = .76) and right eye (p = .54) IA. For the nose IA, larger PI was seen for fearful compared to happy and neutral faces (F = 11.38, p < .05) and for the mouth IA larger PI was seen for happy compared to fearful and neutral faces (F = 20.99, p < .001).

2.1.3. Apparatus and Procedure

Participants sat in a sound-attenuated Faraday-cage protected booth 70cm away from a ViewSonic P95f+ CRT 19-inch monitor (Intel Quad CPU Q6700; 75Hz refresh rate) while performing an explicit emotion discrimination (ED) task. Participants were first given an 8 trial practice session (repeated if necessary), followed by 960 experimental trials. Each trial began with a 1–107ms jittered fixation-cross (see Fig.1B for a trial example). Participants were instructed to fixate on the black fixation-cross in the center of the screen in order to initiate each trial and to not move their eyes until the response screen appeared. To ensure that participants’ fixation was on the cross, a fixation contingent trigger enforced the fixation on the cross for 307ms. Due to sensitivity of the eye-tracker, on average participants took 728ms (S.D. = 926.02) between the onset of the fixation-cross and the stimulus presentation. The face stimulus was then presented for 257ms, immediately followed by the response screen displaying a vertical list of the three emotions (emotion word order counterbalanced between participants). The response screen remained until the response. Participants were instructed to categorize faces by their emotion as quickly and accurately as possible using a mouse by clicking on the appropriate emotion label. They were instructed to keep their hand on the mouse during the entire experiment to avoid unnecessary delays. On average, it took participants 1293ms (S.D. = 256.6ms) to respond. After their response, a screen appeared that read “BLINK” for 307ms. Participants were instructed to blink during this time to prevent eye movement artifacts during the first 500ms of trial recording.

The block of 96 face trials (3 emotions X 4 fixation locations X 8 identities) was repeated 10 times in a randomized trial order, for a total of 80 trials per condition. Following the computer task, participants completed the 21- item trait test from the State-Trait Inventory for Cognitive and Somatic Anxiety (STICSA; Ree, French, MacLeod, & Locke, 2008). The STICSA is a Likert-scale assessing cognitive and somatic symptoms of anxiety as they pertain to one’s mood in general. All participants scored 44 or below on the STICSA, reflecting low to mild anxiety traits. Anxiety was monitored as it is knowns to impact the processing of fear (e.g. Bar-Haim et al., 2007).

2.1.4. Electrophysiological Recordings

The EEG recordings were collected continuously at 516Hz by an Active-two Biosemi system at 72 recording sites: 66 channels4 in an electrode-cap under the 10/20 system-extended and three pairs of additional electrodes. Two pairs of electrodes, situated on the outer canthi and infra-orbital ridges, monitored eye movements; one pair was placed over the mastoids. A Common Mode Sense (CMS) active-electrode and a Driven Right Leg (DRL) passive-electrode acted as ground during recordings.

2.1.5. Eye-Tracking Recordings

Eye movements were monitored using a remote SR Research Eyelink 1000 eye-tracker with a sampling rate of 1000Hz. The eye-tracker was calibrated to each participant’s dominant eye, but viewing was binocular. If participants spent over 10s before successfully fixating on the cross at the start of the trial, a drift correction was used. After two drift corrections, a mid-block recalibration was performed. Calibration was done using a nine-point automated calibration accuracy test. Calibration was repeated if the error at any point was more than 1°, or if the average for all points was greater than 0.5°. The participants’ head positions were stabilized with a head and chin rest to maintain viewing position and distance constant.

2.1.6. Data Processing and Analyses

Each trial was categorized as correct or incorrect based on the emotion categorization and only correct response trials were used for further analysis. In addition, for each participant we also kept trials in which RTs were within 2.5 S.D. from the mean of each condition (Van Selst & Jolicoeur, 1994) as a way to eliminate anticipatory responses (which could overlap with EPN component) or late responses, which excluded 7.05% of the total number of trials across the 20 participants. To ensure foveation to the predefined fixation location areas (left eye, right eye, nose and mouth), trials in which a saccadic eye movement was recorded beyond 1.4° visual angle (70 pixels) around the fixation-location were removed from further analysis. An average of 3.29% of trials were removed during this step across the 20 participants included in the final sample.

The ERP data were processed offline using the EEGLab (Delorme & Makeig, 2004) and ERPLab (http://erpinfor.org/erplab) toolboxes implemented in Matlab (Mathworks, Inc.). The electrodes were average-referenced offline. Average-waveform epochs of 500ms were generated with a 100ms pre-stimulus baseline and digitally band-pass filtered using a two-way least squares FIR filter (0.01–30Hz). Trials containing artifacts >±70μV were rejected using an automated procedure. Trials were then visually inspected and those still containing artefacts were manually rejected. After this two-step cleaning procedure, participants with less than 40 trials in any condition (out of 80 initial trials) were rejected (the average number of trials per condition (M = 61, S.D = 9) did not significantly differ across emotions (p = .35) or fixation location (p = .20)).

Using automatic peak detection, the P1 component was measured between 80 and 130ms post-stimulus-onset (peak around 100ms) at electrodes O1, O2 and Oz where it was maximal (see also Neath & Itier, 2015). The N170 component was maximal at different electrodes across participants, and within a given participant the N170 was often maximal at different electrodes across the two hemispheres (but maximal at the same electrodes across conditions). Thus, the N170 peak was measured between 120–200ms at the electrode where it was maximal for each subject and for each hemisphere (see Table 2; also see Neath & Itier, 2015). This approach, although still infrequently used, has been recommended by some to maximize sensitivity (e.g. Rousselet & Pernet, 2011). To better capture the time course of the fixation and emotion effects, mean amplitudes were also calculated within 50ms windows starting from 50 to 350ms. As P1 peaked on average around 100ms and N170 around 150ms, this approach allowed us to monitor the scalp activity in between these prominent ERP markers, which is important given reports that information integration starts at the transition between these peaks (e.g. Rousselet, Husk, Bennett, Sekuler, 2008; Schyns et al., 2007; see also Itier, Taylor, & Lobaugh, 2004). This approach also allowed to monitor the entire waveform as recommended (e.g. Rousselet & Pernet, 2011), an especially important step to accurately track the emotion-sensitive Early Posterior Negativity (EPN) previously analyzed at very different time windows depending on studies (e.g. Leppänen et al., 2008; Schacht & Sommer, 2009; Schupp et al., 2004).

Table 2.

Number of subjects for whom the N170 was maximal at left (P9, CB1, PO7, P7, O1, TP9) and right hemisphere (P10, CB2, P08, P8, O2, TP10) electrodes. LH: left hemisphere; RH: right hemisphere.

| Explicit Emotion Discrimination (Exp.1) | Oddball Detection (Exp.2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| LH | RH | LH | RH | |

| P9/P10 | 11 | 14 | 10 | 12 |

| CB1/CB2 | 6 | 4 | 11 | 6 |

| PO7/PO8 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| P7/P8 | - | - | - | 3 |

| O1/O2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| TP9/TP10 | - | - | 1 | - |

|

| ||||

| Total n | 20 | 20 | 26 | 26 |

Inspection of the data revealed different effects over occipital sites and lateral-posterior sites. Thus for each time window, separate analyses were conducted using mean amplitudes calculated across three clusters: an occipital cluster (Occ, averaging O1, O2 and Oz), a left lateral cluster (Llat, averaging CB1, P9, P7 and PO7) and a right lateral cluster (Rlat, averaging CB2, P10, P8 and PO8). Note that the lateral-posterior electrodes included the electrodes where the N170 was measured across participants and also included the visual P2 component (peaking around 200ms post-face onset) as well as the EPN. Finally, to test the idea that the “fear effect” (the amplitude difference between fearful and neutral faces) and the “happiness effect” (the amplitude difference between happy and neutral faces) occurred at different sites, we also analyzed scalp distributions. We first created difference waveforms for each subject and each fixation location, by subtracting ERPs to neutral faces from ERPs to fearful faces (F-N) and ERPs to neutral faces from ERPs to happy faces (H-N). We then calculated the mean amplitude at each electrode across each of the 6 time windows (50ms to 350ms in 50ms bins) and analyzed them statistically. Although they have been criticized (Luck, 2005; Urbach & Kutas, 2002), normalized amplitudes are also still quite often used so we also normalized all mean amplitudes according to the method described in McCarthy and Wood (1985).

Repeated-measure ANOVAs were conducted separately for correct categorization and ERP amplitudes using SPSS Statistics 22. Within-subject factors included emotion (3: fear, happiness, neutral) and fixation location (4: left eye, right eye, nose, mouth) for all analyses, as well as hemisphere for N170 (2: left, right), electrode for P1 (3: O1, O2, Oz), and cluster for mean amplitudes (3: Occ, Llat, Rlat). If necessary, further analyses of the interactions found were completed with separate ANOVAs for each cluster, each fixation location or each emotion. For scalp distribution analyses, mean amplitude difference scores at each time window were analyzed using a repeated measure ANOVA with emotion effect (2: fear effect, happiness effect), fixation location (4: Left Eye, Right Eye, Nose, Mouth) and electrode (72) as within-subject factors. Interactions between electrode and emotion effect would reveal a significant difference in scalp distribution between the two emotional effects.

All ANOVAs used Greenhouse-Geisser adjusted degrees of freedom whenever the Mauchly’s test of sphericity was significant (i.e. when sphericity was violated) and pair-wise comparisons used Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons.

2.2 Results

2.2.1. Correct responses

The overall categorization rate was very good (≥80%, Table 3). Overall, participants made fewer correct responses for neutral than happy faces (main effect of emotion, F(1.61, 30.67)=3.98, p< .05, ηp2= .17; significant neutral-happy paired comparison at p< .05). Correct responses were also slightly better for nose and mouth fixations compared to eye fixations (main effect of fixation location, F(2.35, 44.67)=18.01, p< .005, ηp2 =.24; left eye-nose and left eye-mouth paired comparisons at p< .05). No emotion by fixation location interaction was seen.

Table 3.

Mean correct responses for fearful, happy and neutral expressions presented during the emotion discrimination task in Exp. 1 (standard errors to the means in parenthesis).

| Mean (%) Correct in ED task (std error) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Left Eye | Right Eye | Nose | Mouth | |

| Fear | 87.4 (1.2) | 90.8 (1.2) | 90.0 (1.0) | 97.0 (1.2) |

| Happy | 90.7 (0.8) | 91.4 (1.1) | 91.6 (0.9) | 91.7 (1.1) |

| Neutral | 85.9 (1.9) | 87.5 (1.8) | 88.8 (1.2) | 91.4 (1.0) |

2.2.2. P1 Peak Amplitude

Overall largest P1 amplitude was found for fixation to the mouth (main effect of fixation, F(2.18, 41.39) = 31.9, p < .0001, ηp2 = .63) (see Fig. 2A). Fixation location also interacted with electrode (F(2.58, 48.97) = 9.9, p < .0001, ηp2 = .34) due to opposite hemispheric effects for fixation to each eye. On the left hemisphere (O1), P1 was larger for the mouth and left eye (which did not differ significantly) compared to the right eye and the nose fixations (which did not differ) (main effect of fixation location, F(1.95, 37.13)=27.75, p< .0001, significant paired comparisons at p< .0001). On the right hemisphere (O2), P1 was larger for the mouth and right eye (which did not differ significantly) compared to the left eye and nose fixations which did not differ (main effect of fixation location, F(2.34, 44.5)=14.45, p< .0001; significant paired comparisons p< .001). At Oz electrode, P1 was also larger for fixation to the mouth compared to the left eye, right eye and nose which did not differ significantly from each other (main effect of fixation location, F(2.04, 38.71) = 34.62, p < .0001, ηp2 = .65; significant paired comparisons with mouth fixation at p < .001) (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

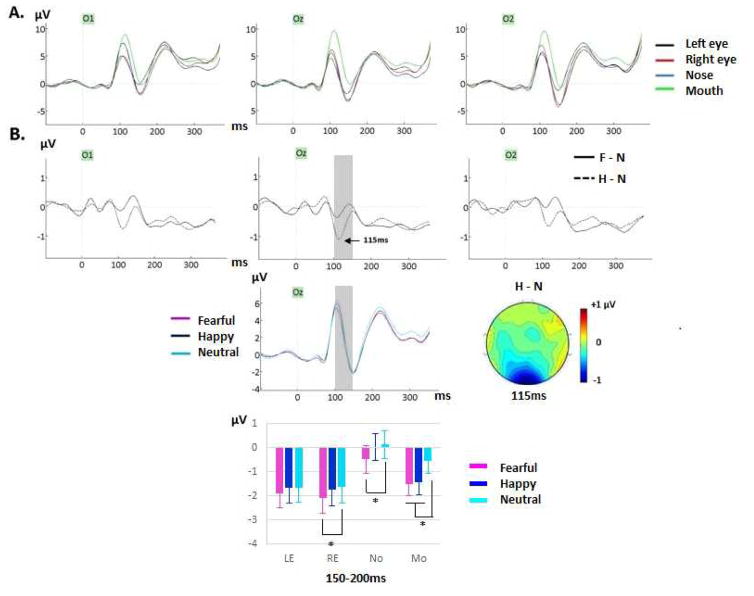

(A) Grand-averages featuring the P1 component for Exp. 1 (ED) for neutral faces at O1, Oz, and O2 electrodes, showing effects of fixation location with larger amplitudes for mouth fixation and opposite hemispheric effects for eye fixations. (B) Grand-average difference waveforms generated by subtracting ERPs to neutral faces from ERPs to fearful faces (F-N, solid line) and ERPs to neutral faces from ERPs to happy faces (H-N, dashed line) (across fixation locations). A clear difference peak for H-N was seen between 100–150ms (light gray band on Oz, peak of the “happiness effect” around 115ms, see topographic map – view from above) and was confirmed by mean amplitude analysis during that time window (see main text and Table 4). The grand-averaged waveforms for fearful, happy and neutral faces (across fixation locations) at Oz clearly show that this “happiness effect” started on the P1 peak. (C) Between 150–200ms, the happiness effect was seen for the mouth fixation condition only (smaller amplitudes for happy than neutral faces) as shown by the bar graph (computed across clusters). The fear effect was also seen mainly for mouth fixation and to a lesser extent for nose and right eye fixations.

An effect of emotion was also found (F(1.86, 35.47) = 3.37, p = .049, ηp2 = .15) due to a reduced positivity for happy expressions, but the Bonferroni corrected happy-neutral paired comparison only approached significance (p=.088). Although the emotion by electrode interaction also only approached significance (F(2.61, 49.69) = 2.72, p = .062, ηp2 = .125), we analyzed each electrode separately given our previous study where a similar emotion effect was found only at Oz site (Neath & Itier, 2015). This happiness effect was indeed significant at Oz (main effect of emotion, F(1.98, 37.65) = 5.74, p <.01, ηp2 = .23; happy-neutral paired comparison p=.013) as best seen by difference waveforms (happy-neutral), and was largest right after the P1, around 115ms (Fig. 2B). In contrast, no emotion effect was seen at O1 (F(1.81, 34.5)=2.75, p=.083) or O2 (F(1.96, 37.31)=.22, p=.79) electrodes. This occipital happiness effect was also confirmed statistically with mean amplitude analyzes during the 100–150ms window as an interaction between cluster and emotion (Table 4, discussed below). Please note that in the remainder of the paper, the “happiness effect” will denote significantly smaller amplitudes for happy than neutral faces and the “fear effect” will denote significantly smaller amplitudes for fearful than neutral faces.

Table 4.

Exp. 1 (Emotion discrimination –ED- task) statistical effects on mean amplitudes analyzed over six 50ms time windows at 3 clusters (occipital cluster - Occ: O1, Oz, O2-, Left lateral cluster – Llat: CB1, P7, PO7, P9- and Right lateral cluster – Rlat: CB2, P8, PO8, P10), with F, p and ηp2 values. LE, left eye; RE, right eye; No, nose; Mo, mouth; F, fear; H, happiness; N, neutral. Significant Bonferroni-corrected paired comparison tests are also reported with their p values (e.g., H < F + N means that mean amplitude for happy was significantly smaller compared to both fearful and neutral expressions, while H + F < N means that mean amplitudes for both happy and fearful faces were significantly smaller than to neutral expressions). Effects reported in italics in parenthesis are effects that were weak and not clear and thus were treated as non-significant and not discussed in the text.

| Statistical effects | 50–100ms | 100–150ms | 150–200ms | 200–250ms | 250–300ms | 300–350ms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation location | - |

F (3,57)= 22.41, p<.0001, ηp2 =.54 Mo > LE > RE + No |

F(1.78,33.87)= 12.46, p<.0001, ηp2=.4 LE + RE + Mo < No |

F(3,57)= 3.78, p=.024, ηp2=.17, RE + Mo < No | - | - |

| Emotion | - | - |

F(2,38)= 22.32, p<.0001, ηp2=.54 F< H+N |

F(2,38)= 31.26, p<.0001, ηp2=.62, F<H<N |

F(2,38)= 23.33, p<.0001, ηp2=.55 F<H<N |

F(2,38)= 21.32, p<.0001, ηp2=.53 F<H<N |

| Cluster X Emotion | - |

F(4,76)= 7.23, p<.0001, ηp2=.28 *Occ: F (2,38)= 7.09, p=.003, ηp2= .27 H<N (p=.009); H<F (p=.025); *Llat: no emotion effect *Rlat: F (2,38)= 5.16, p=.014, ηp2=.21, F>N (p=.013); |

- |

F(4,76)= 2.95, p=.037, ηp2=.13 *Occ: F (2,38)= 11.6, p<.0001, ηp2=.38 H<N (p=.037) *Llat: F (2,38)= 29.39, p<.0001, ηp2=.61 F<H ; F<N (ps<.001) *Rlat: F (2,38)= 29.34, p<.0001, ηp2=.61 F<H; F<N; H<N (ps<.005) |

- | - |

| Cluster X Fixation location | - (F(3.47,66.02)= 5.27, p=.002, ηp2 =.22, *Occ: no fixation effect *Llat: F(1.96,37.33)= 4.2, p=.023, ηp2=.18, Paired Comparisons ns *Rlat: F(3,57)=3.48, p=.031; ηp2=.16 Paired Comparisons ns) |

F(6,114)= 21.89, p<.0001, ηp2=.54 *Occ: F(3,57)= 35.25, p<.0001, ηp2=.65 Mo > all (ps<.0001); LE > RE (p=.015) *Llat: F(3,57)= 12.54, p<.0001, ηp2=.4 LE > RE + No (ps<.001) *Rlat: F(3,57) =5.19, p=.004; ηp2 =.22 Mo > No (p=.005) |

F(3.28,62.34)= 3.34, p=.021, ηp2=.15 *Occ: F(1.91, 36.34)= 4.2, p=.024, ηp2=.18; No + Mo > eyes but paired comparisons ns *Llat: F(3,57)= 11.31, p<.0001, ηp2 =.37 RE < LE < No *Rlat: F(3,57) =15.33, p<.0001; ηp2=.45 LE + RE < Mo < No |

- | - |

- (F(2.88,54.67)= 2.82, p=.05, ηp2=.13 *Occ: no fixation effect *Llat: no fixation effect *Rlat: no fixation effect) |

| Emotion X Fixation location | - | - |

F (6, 114) = 3.03, p=.009, ηp2=.14 *LE: no emotion effect *RE: F(2,38) = 4.85, p=.013, ηp2=.2; F<N (p=.028) *No: F(2,38) = 6.85, p=.003, ηp2=.26; F<H (p=.016); F<N (p=.01) *Mo: F(2,38) = 15.38, p<.0001, ηp2=.45; F<N ; H<N (ps<.001) |

- |

F (6,114) = 2.47, p=.048, ηp2=.12, *LE: F(2,38) = 14.72, p<.001, ηp2=.44; F<H; F<N (ps<.005) *RE: F(2,38) = 16.23, p<.001, ηp2=.46; F<H (p=.017); F<N (p<.0001) *No: no emotion effect *Mo: F(2,38) = 7.99, p=.001, ηp2=.30; F<N (p=.007); H<N (p=.015); |

F (6, 114) = 3.27, p=.012, ηp2=.15 *LE: F(2,38) = 9.81, p=.001, ηp2=.34; F<N (p=.001) *RE: F(2,38) = 11.03, p<.001, ηp2=.37; F<N (p<.001) *No: no emotion effect *Mo: F(2,38) = 16.56, p<.0001, ηp2=.47; F<N (p=.001); H<N (p<.001); |

| Cluster X Emotion X Fixation location |

- | - (F(6.45,122.5)= 2.5, p=.023, ηp2=.12 *Occ: no emo x fix *Llat: no emo x fix *Rlat: emo x fix, F(6,114)= 3.35, p=.011, ηp2 =.15 but no emotion effect for any fixation location) |

- | - | - | - |

2.2.3. N170 Peak Amplitude

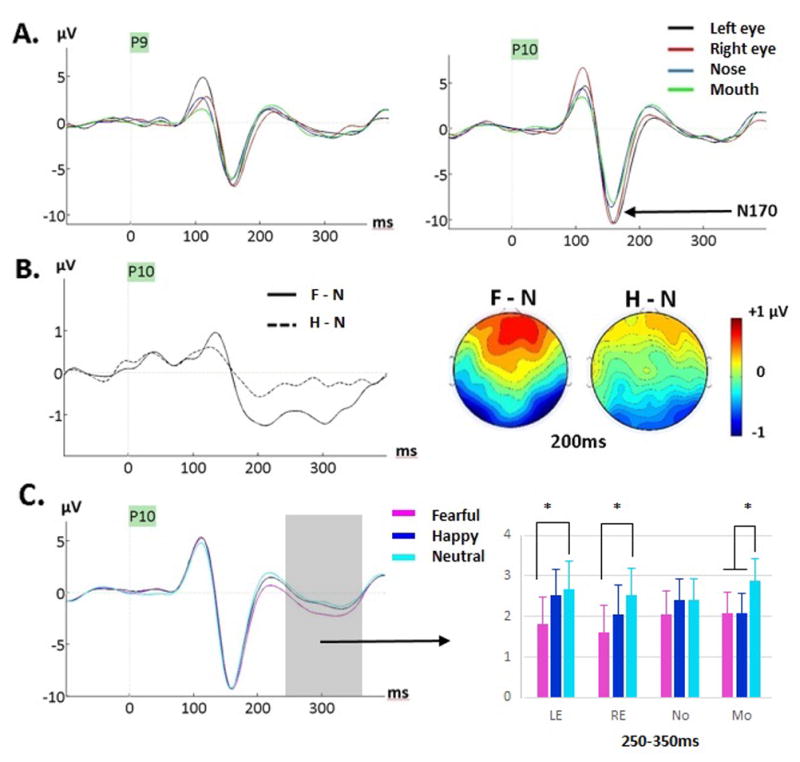

The N170 amplitude was larger for fixation to the left and right eyes (which did not differ) compared to fixation to the mouth and nose which did not differ significantly (main effect of fixation location, F(1.49, 28.29)=12.63, p<.0001, ηp2=.40; all paired comparisons at p-values <.01) (Fig. 3A). This fixation effect was more pronounced on the right than on the left hemisphere (hemisphere by fixation location, F(1.57, 29.84)=3.61, p<.05, ηp2=.56). The N170 amplitude was also larger in the right compared to the left hemisphere (main effect of hemisphere, F(1, 19)=8.52, p<.01, ηp2=.31). No effects of emotion or emotion by fixation location interaction were seen.

Figure 3.

(A) Grand-averages featuring the N170 component for neutral faces at P9 and P10 as a function of fixation location during Exp. 1 (ED task). A clearly larger N170 for eyes compared to nose and mouth fixations, is seen. The opposite hemispheric effects for eye fixations are also seen on the preceding P1. (B) Grand-average difference waveforms generated by subtracting ERPs to neutral from ERPs to fearful faces (F-N, solid line) and ERPs to neutral from ERPs to happy faces (H-N, dashed line) at P10, showing the emergence of the fear effect around 200ms with lack of emotion effect on the N170. The maps show the voltage difference between fearful and neutral faces (F-N) and happy and neutral faces (H-N) at 200ms post-stimulus, when the fear effect was largest. (C) Grand-averages for fearful, happy and neutral faces (across fixation locations) at P10 site where the effect was clearly seen. The gray interval over 250–350ms is where an emotion by fixation interaction was seen (see Table 5); the bar graph depicts the mean amplitudes averaged across the 250–300 and 300–350ms intervals (across the three clusters). The fear effect was seen for both eyes and mouth fixations while the happiness effect was seen for mouth fixation only.

2.2.4. Mean Amplitudes over Six Time Windows (Occipital, Left lateral and Right lateral clusters)

Statistical results for these analyses (50–350ms) are reported in Table 4 and visually depicted in Figures 2, 3 and 4.

Figure 4.

Mean voltage distribution maps of the grand-average difference waveforms between fear and neutral and happy and neutral faces across six 50ms time intervals from 50ms to 350ms (averaged across fixation location) in Exp. 1 (ED task, left panels) and in Exp. 2 (ODD task, right panels). The early occipital effect for happy faces is clearly seen between 100–150ms while the fear effect starts at 150–200ms. Different topographies are seen for the two emotions. The grand-average difference waveforms (F-N and H-N, across fixation locations) are shown at lateral-posterior sites (left and right clusters, bottom panels) and show the stronger fear than happiness effect across most of the epoch. The gray zones indicates the time during which significant emotion effects were seen at these sites (150–350ms, see Tables 4–5).

Fixation location interacted with clusters between 100–200ms (Table 4). More positive amplitudes were seen when fixation was to the mouth compared to the other facial features between 100 and 150ms, and this effect was strongest at occipital sites, as found for P1 peak (Table 4, Fig.2). During that time window, amplitudes were also larger for the left than right eye fixation at left lateral sites, reminiscent of the fixation effect seen on the P1 peak. Between 150 and 200ms, overall more positive amplitudes were seen during fixation to the nose and mouth at occipital sites. A lateral sites, mean amplitudes became more negative for the eyes than the nose and mouth, paralleling effects seen on the N170 component (Fig.3). Between 200 and 250ms, the mean amplitudes were overall larger for nose and mouth fixations than for eye fixations. After 250ms, no more fixation location effect was seen.

An emotion effect was first seen during the 100–150ms time window with smaller amplitudes for happy compared to neutral (and fearful) expressions (Fig. 2B) at occipital sites only (cluster x emotion, Table 4), confirming the happiness effect found on P1 reported previously. At 150–200ms, a significant emotion by fixation location interaction revealed that the happiness effect was only seen for the mouth fixation condition (Fig.2B, Table 4). During that time window, a fear effect (more negative amplitudes for fearful than neutral faces) was seen for the right eye, nose and mouth fixations, but not for the left eye fixation. Between 200–250ms, the happiness effect was seen at occipital and right lateral sites but not at left lateral sites, while the fear effect was seen at both left and right lateral sites but not at occipital sites (cluster x emotion interaction, Table 4). Between 250 and 350ms, emotion interacted again with fixation location (Table 4, Fig. 3C) as the happiness effect was seen only at the mouth fixation while the fear effect was seen when fixation was on the eyes and mouth, but not when fixation was on the nose.

To summarize, a happiness effect was seen from ~100ms until 350ms, as clearly seen on the difference waveforms and their topographic maps (Fig. 4, see also Fig. 2B). This happiness effect was overall less pronounced than the fear effect, and was only seen at the mouth fixation location between 150–200ms, and between 250–350ms. A fear effect was seen a bit later, starting at 150ms until 350ms, best captured by difference waves and their topographies as a bilateral posterior negativity with positive counterpart at frontal sites (Fig. 3–4); this fear effect peaked around 200ms (Fig. 3B).

2.2.5. Scalp Topographies

The analysis of the mean amplitude differences (fear-neutral and happy-neutral) revealed a significant interaction between the emotion effect and electrode factors for all but one time windows: 50–100ms (F(6.55, 124.54)=2.12, p=.05, ηp2=.1); 100–150ms (F(5.52, 105.05)=2.03, p=.073, ηp2=.097); 150–200ms (F(7.64, 145.15)=4.51, p<.0001, ηp2=.192); 200–250ms (F(7.01, 133.24)=5.45, p<.0001, ηp2=.223); 250–300ms (F(5.47, 103.88)=3.69, p=.003, ηp2=.163); 300–350ms (F(7.87, 149.5)=3.06, p=.003, ηp2=.139). When normalized amplitudes were used, the interaction between emotion effect and electrode factors was significant for the same time windows: 50–100ms (F(7.05, 134.01)=2.87, p=.008, ηp2=.13); 100–150ms (F(6.29, 119.52)=1.68, p=.127, ηp2 =.081); 150–200ms (F(7.79, 147.96)=4.01, p<.001, ηp2 =.174); 200–250ms (F(7.32, 139.08)=3.94, p<.0005, ηp2=.172); 250–300ms (F(6.75, 128.25)=3.02, p=.006, ηp2=.137); 300–350ms (F(8.06, 153.05)=2.34, p=.021, ηp2=.11). These results confirm that scalp topographies of the fear and happiness effects were different during most of the epoch analyzed (see Figure 4), and based on the effect sizes, the difference was maximal between 150ms and 250ms.

2.3 Discussion

Using the same gaze-contingent procedure as Neath and Itier (2015), we investigated the effects of fixation to different facial features on the neural processing of fearful, happy and neutral facial expressions in an explicit emotion discrimination task. Overall emotion categorization performance was very good and in line with the ratings originally reported in the validation study of the NimStim database when using faces with open mouths (Tottenham et al., 2009), with better discrimination for happy relative to neutral expressions. A categorization performance advantage was also seen during fixation to the nose and mouth compared to the eyes, supporting the idea of an emotion recognition advantage from facial information in the bottom half of the face (e.g., Blais et al., 2012).

As predicted, a clear fixation effect was seen between 100 and 150ms at occipital sites (Figure 2A, Table 4) with larger amplitude when fixation was on the mouth compared to the eyes and nose. This effect was also seen on P1 peak and likely reflected sensitivity to the face position on the screen, given that most facial information was in the upper visual field during fixation to the mouth. P1 amplitude was also larger when fixation was on the right than on the left eye on the right hemisphere and larger for fixation on the left eye compared to the right eye on the left hemisphere (Fig.2A). The larger amplitude for the left than the right eye fixation was also captured by mean amplitude analyses between 100–150ms (Table 4). This fixation effect reflects hemifield presentation effects as most of the facial information was in the left visual field when fixation was on the right eye and the right visual field when fixation was on the left eye (Fig.1A). This effect mirrors fixation effects reported by recent studies using similar gaze-contingent procedures (de Lissa et al., 2014; Neath & Itier, 2015; Nemrodov et al., 2014; Zerouali, Lena, & Jemel, 2013).

As also expected, we found larger N170 amplitudes for both eye fixations (Fig. 3A) compared to the nose and mouth fixations (de Lissa et al., 2014; Neath & Itier, 2015; Nemrodov et al., 2014). This larger amplitude for the eyes was also found with the mean amplitude analysis at lateral-posterior sites between 150–200ms and supports the idea of a special role for the processing of eyes at the level of the face structural encoding. This N170 eye sensitivity was seen to the same extent for the three facial expressions, as also reported by Neath and Itier (2015), and there was no effect of emotion on this component, consistent with previous ERP studies requiring discrimination of facial expressions (e.g., Kerestes et al., 2009; Leppänen et al., 2008; Schupp et al., 2004; however see Hinojosa et al., 2015).

Like Neath and Itier (2015), we also found smaller amplitudes for happy relative to neutral expressions (happiness effect) starting on P1, ~100–350ms post-stimulus, and smaller amplitudes for fearful relative to neutral expressions (fear effect) starting later, right after the N170, ~150–350ms post-stimulus. The overall scalp distribution and timing of these happiness and fear effects were remarkably similar to the Neath and Itier (2015) study and topography analyses confirmed the different scalp distribution of these effects during most of the epoch, especially during 150–250ms. The mean amplitude analysis also revealed differences at posterior sites, with the happiness effect being uniquely occipital early on (100–150ms). Between 200–250ms, the happiness effect was distributed over occipital and right lateral sites (but not left lateral sites), while the fear effect was found at both right and left lateral sites but not at occipital sites. Together these findings suggest that these emotion effects have a distinct time course and that their underlying generators are distinct or work differently.

Emotion also interacted with fixation location between 150 and 200ms post-stimulus onset (Table 4), with the happiness effect seen only during fixation to the mouth while the fear effect was seen when fixation was on the right eye, the nose and the mouth (Fig. 2B). Neath and Itier (2015) reported a similar interaction during that same time period except only at occipital sites with both fear and happiness effects seen for the mouth fixation only. This lsight difference is likely due to the separate measure of occipital and posterior lateral sites in that study, compared to a cluster approach in the current study. Novel to the current explicit emotion discrimination task was an emotion by fixation location interaction between 250 and 350ms (coinciding with EPN), with a fear effect seen when fixation was on either the eyes or the mouth, but not on the nose. During that time window, a happiness effect was only seen during fixation on the mouth, but not during fixation on the nose or eyes. In other words, fixation on the eyes impacted processing of fearful faces but not happy faces while fixation on the mouth impacted processing of both happy and fearful expressions.

Overall, the present results support the importance of diagnostic features at the neural level. In line with eye movement monitoring studies (Bombardi et al., 2013; Eisenbarth & Alpers, 2011) the current study suggests that both the mouth and eyes are important for the processing of fearful faces, not just the eyes as suggested by others (e.g., Schyns et al., 2007, 2009; Smith et al., 2005). It is important to note, however, that these results might be specific to the current emotion discrimination task. Whether these features play an important role in the processing of fearful and happy expressions during tasks where less attention to the face is required was tested in Experiment 2 (oddball detection task).

3. Experiment 2 – Oddball (ODD) detection task

3.1 Method

3.1.1. Participants

Forty-five undergraduate students were tested at UW and received course credit. All participants lived in North America for at least 10 years and reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision, no history of head-injury or neurological disease, and were not taking any medication. They all signed informed written consent and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at UW. A total of 19 participants were rejected: 2 for completing less than half of the experiment thus rendering too few trials per condition; 5 for too many trials with artefacts resulting in too few trials per condition; 10 due to too few trials remaining after removing trials with eye movements greater than 1.4° of visual angle from the fixation location (see Exp. 1 method); and 2 due to high anxiety (scores equal or higher than 44 on the STICSA, Van Dam, Gros, Earleywine, & Antony, 2013). The results from 26 participants were kept in the final analysis (20.8 ± 1.7 years, 15 female, 22 right-handed). None of the participants took part in Exp.1.

3.1.2. Stimuli

The exact same faces as those in Exp. 1 were used. In addition, 6 flower images were used as oddball stimuli. To be consistent with the face images, all flower stimuli were converted to greyscale in Adobe™ Photoshop CS5 and an elliptical mask was applied (see Fig. 1A bottom left). As in Exp. 1, a unique central fixation-cross was used and each face was presented offset so the pre-determined center of each feature would land on the center of the fixation-cross. To keep in line with the experimental paradigm, coordinates corresponding to the left eye, right eye, nose and mouth of a randomly selected neutral face identity were used for all flower stimuli (see Fig. 1A).

3.1.3. Apparatus and Procedure

Participants completed an oddball-detection task where they were instructed to press the space bar as quickly and accurately as possible to the target stimuli (flowers) which occurred infrequently (20% of the time) amongst non-target stimuli (fearful, happy and neutral faces). Participants were given 8 practice trials to introduce them to the experimental procedure. The experimental session used the same gaze-contingent procedure as in Exp. 1 except for the response screen (Fig. 1B). On average participants took 880ms (S. D. = 781) between the onset of the fixation cross and the stimulus presentation. The stimulus was immediately followed by a fixation cross that was presented until response after a flower stimulus, and for 747ms after a face stimulus or if no response was recorded to the flower picture. Participants were instructed to blink during this time.

Each block contained 96 face trials (3 emotions X 4 fixation locations X 8 identities) and 24 flower trials (4 fixation locations X 6 flowers), and was repeated 10 times in a randomized order, yielding 80 trials per face condition. Participants then completed the 21 item trait anxiety test from the STICSA.

3.1.4. Electrophysiological and eye-tracking recordings

Identical to Exp. 1.

3.1.5. Data processing and analyses

Identical to Exp. 1. In this task 6.8% of trials across the final 26 participants were removed due to eye movements recorded beyond 1.4° visual angle (70px) around the fixation location. The average trial number (M= 55, S.D = 10) did not differ significantly by emotion (p = .17) or fixation location (p = .33).

3.2 Results

Overall detection of flower stimuli was excellent (~98%) demonstrating that participants were attending to the task. In addition, participants correctly withheld their responses when they detected a facial stimulus (~99%) and this did not differ by emotion (p = .13) or fixation location (p = .17).

3.2.1. P1 Peak Amplitude

P1 amplitude was largest at O2 (main effect of electrode, F(2, 50) = 7.29, p = .002, ηp2 = .23; O2-Oz comparison p =.002, O2-O1 comparison p =.09) and overall largest for fixation to the mouth (main effect of fixation, F(2.21, 55.19) = 14.39, p < .0001, ηp2 =.37) (see Fig. 5A). As seen in Exp. 1, an interaction between fixation location and electrode (F(3.45, 86.25) = 15.77, p <.0001, ηp2 =.39) was due to eye fixations yielding opposite effects on each hemisphere. On the left hemisphere (O1), P1 was larger for the mouth and left eye (which did not differ significantly) compared to the right eye and the nose fixations (which did not differ) (main effect of fixation location, F(2.42, 60.72) = 20.32, p < .0001; ηp2 = .45). On the right hemisphere (O2), P1 was larger for the mouth and right eye (which did not differ significantly) compared to the left eye and nose fixations which did not differ (main effect of fixation location, F(1.85, 46.27) = 11.57, p < .001; ηp2 = .32; significant paired comparisons p < .01). P1 at Oz was also larger for fixation to the mouth compared to all other fixation locations which did not differ significantly from each other (main effect of fixation location, F(2.42, 60.53) = 14.69, p < .0001, ηp2 = .37; significant paired comparisons with mouth fixation at p < .05) (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

(A) Grand-averages featuring the P1 component for Exp. 2 (ODD task) for neutral faces at O1, Oz, and O2 electrodes, showing effects of fixations with larger amplitudes for mouth fixation and opposite hemispheric effects for eye fixations. (B) Top row: Grand-average difference waveforms generated by subtracting ERPs to neutral from ERPs to fearful faces (F-N, solid line) and ERPs to neutral from ERPs to happy faces (H-N, dashed line) at O1, Oz and O2 (across fixation locations). A clear peak for the happy-neutral difference was seen between 100–150ms (gray band, peak of the effect around 120ms) and was confirmed by mean amplitude analysis at occipital sites during that time window (see main text and Table 5). Bottom row: (middle) Grand-averaged waveforms for fearful, happy and neutral faces (across fixation locations) at Oz showing the “happiness effect” starting at P1, although only for the mouth fixation condition (left, bar graph). (Right) The topographic map depicting the happy-neutral difference is shown at 120ms, clearly revealing an occipital distribution.

An effect of emotion was also found, with reduced positivity for happy compared to neutral (and fearful) faces (main effect of emotion, F(1.98, 49.56) = 5.67, p =.006, ηp2 = .19; significant paired comparisons happy-neutral, p=.014 and happy-fearful, p=.03). This happiness effect also interacted with fixation location (F(4.96, 123.99) = 2.49, p =.035, ηp2 =.09) as the effect of emotion was only significant at mouth fixation (F(1.63, 40.75) =9.9, p=.001; significant comparisons: happy-neutral p =.002, and happy-fearful, p =.023). No emotion effect was seen for the left eye (p =.99) or the right eye (p =.42); although an effect of emotion was seen for the nose fixation (p =.038), paired comparisons did not reach significance (see Fig 5B P1 bar graph). Difference waveforms (fearful-neutral and happy-neutral, across fixation locations) clearly revealed this happiness effect at occipital sites that was largest around 120ms (Fig. 5B). This early effect was confirmed with mean amplitude analyzes during the 100–150ms window (Fig.4, see below).

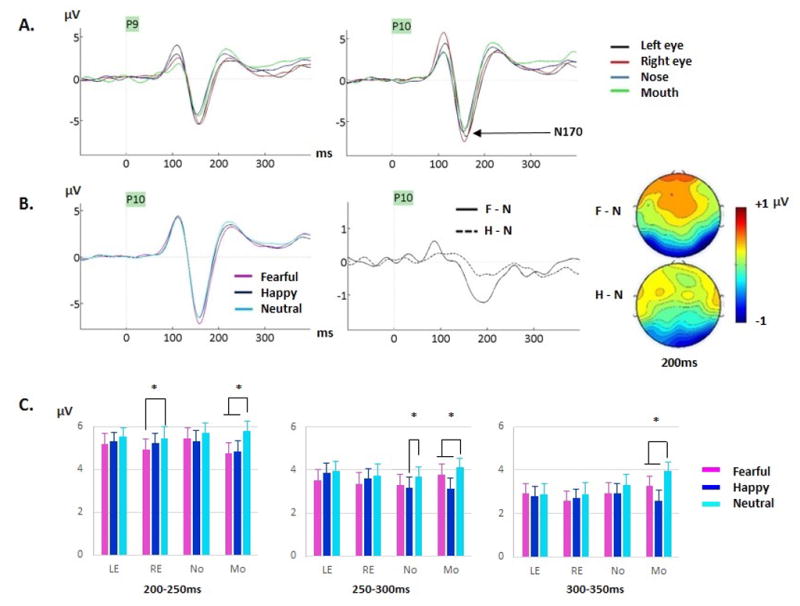

3.2.2. N170 Peak Amplitude

The N170 amplitude was larger in the right compared to the left hemisphere (F(1,25)=7.12, p=.013, ηp2=.22) and for fixation to the left and right eye (which did not differ) compared to fixation to the mouth and nose which did not differ significantly (main effect of fixation location, F(2.66, 66.41)=23.52, p<.0001, ηp2=.49; all paired comparisons at p-values <.001) (Fig. 6A). In contrast to Exp.1, the N170 was larger for fearful compared to neutral (and happy) faces (Fig. 6B) (main effect of emotion, F(1.93, 48.33)=10.34, p<.001, ηp2=.29; significant fearful-happy and fearful-neutral paired comparisons p<.01). There was also an emotion by hemisphere interaction (F(1.94, 48.37)=4.33, p=.02, ηp2=.15) such that N170 amplitudes were larger for fearful compared to both neutral and happy faces in the left hemisphere (emotion effect, F=11.28, p<.001; significant fearful-neutral paired comparison p=.028 and fearful-happy p=.001), while N170 was larger for fearful only compared to neutral faces in the right hemisphere (emotion effect, F=6.61, p<.01; significant fearful-neutral comparison p=.003).

Figure 6.

(A) Grand-averages featuring the N170 component for neutral faces at P9 and P10 as a function of fixation location during Exp.2 (ODD task). A clearly larger N170 for eyes compared to nose and mouth fixations, is seen. The opposite hemispheric effects for eye fixations are also seen on the preceding P1. (B) Left. Grand-averages for fearful, happy and neutral faces (across fixation locations) at P10 site featuring a larger N170 peak for fearful than neutral and happy faces. Right. Grand-average difference waveforms generated by subtracting ERPs to neutral from ERPs to fearful faces (F-N, solid line) and ERPs to neutral from ERPs to happy faces (H-N, dashed line) at P10. The maps show the F-N and H-N voltage differences across the scalp at a latency of 200ms where the effects were largest. (C) Emotion by fixation location interactions are displayed in 3 bar graphs, between 200–250ms, 250–300ms and 300–350ms. Note the clear fear and happiness effects at mouth fixation (also see Table 5).

3.2.3. Mean Amplitudes over Six Time Windows (Occipital, Left lateral and Right lateral clusters)

Statistical results for these analyses (50–350ms) are reported in Table 5 and visually depicted in Figures 4, 5 and 6.

Table 5.

Exp. 2 (Oddball –ODD- task) statistical effects on mean amplitudes analyzed over six 50ms time windows at 3 clusters (occipital cluster - Occ: O1, Oz, O2-, Left lateral cluster – Llat: CB1, P7, PO7, P9- and Right lateral cluster – Rlat: CB2, P8, PO8, P10), with F, p and ηp2 values. LE, left eye; RE, right eye; No, nose; Mo, mouth; F, fear; H, happiness; N, neutral. Bonferroni-corrected significant paired comparison tests are also reported with their p values (e.g., H < F + N means that mean amplitude for happy was significantly smaller compared to both fearful and neutral expressions, while H + F < N means that mean amplitudes for both happy and fearful faces were significantly smaller than to neutral expressions). Effects reported in italics in parenthesis are effects that were weak and not clear and thus were treated as non-significant and not discussed in the text.

| Statistical effects | 50–100ms | 100–150ms | 150–200ms | 200–250ms | 250–300ms | 300–350ms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation location | - |

F (2.25,56.43)= 21.43, p<.0001, ηp2 = .46 Mo > LE > RE + No |

F(1.78,44.39)= 20.74, p<.0001, ηp2=.45 LE + RE + Mo < No |

- | - | F(2.37,59.29)= 3.42, p=.032, ηp2=.12, Mo > RE |

| Emotion | - | - |

F(1.59,39.88)= 17.22, p<.0001, ηp2=.41 F<H<N |

F(2,50)= 17.13, p<.0001, ηp2=.41 F+H<N |

F(2,50)= 8.92, p<.001, ηp2=.26 F+H<N |

F(2,50)= 13.43, p<.0001, ηp2=.35, F+H<N |

| Cluster X Emotion | - |

F(4,100)= 15.72, p<.0001, ηp2=.39 *Occ: F (2,50)= 16.32, p=.0001, ηp2 = .39 H<F; H<N (ps<.0001) *Llat: no emotion effect *Rlat: no emotion effect |

F(4,100)= 6.79, p<.0001, ηp2=.21 *Occ: F (2,50)= 13.72, p=.0001, ηp2=.35 F<N; H<N (ps=.001) *Llat: F (1.51,37.85)= 11.18, p<.001, ηp2=.31 F<H; F<N (ps<.005) *Rlat: F (2,50)= 19.23, p<.0001, ηp2=.44 F<N (p<.001); H<N (p=.02) |

F(4,100)= 3.78, p=.009, ηp2=.13 *Occ: F (2,50)= 16.65, p<.0001, ηp2=.4 F<N; H<N (ps<.001) *Llat: F (2,50)= 10.3, p<.001, ηp2=.29 F<N (p=.001) *Rlat: F (2,50)= 15.65, p<.0001, ηp2=.38 F<N (p<.001); H<N (p=.02) |

F(4,100)= 4.74, p=.002, ηp2=.16 *Occ: F (2,50)= 9.5, p<.0001, ηp2=.27 H<N (p<.001) *Llat: F (2,50)= 5.53, p=.007, ηp2=.18 F<N (p=.024) *Rlat: F (2,50)= 8.33, p=.001, ηp2=.25 F<N (p=.017); H<N (p<.001) |

- |

| Cluster X Fixation location |

F(6,150)= 5.42, p<.001, ηp2 =.18 *Occ: no fixation effect *Llat: F(3,75)= 4.71, p=.007, ηp2 = .16 LE > RE *Rlat: F(3,75)=5.46, p=.003; ηp2 = .18; RE + No > LE + Mo |

F(6,150)= 21.46, p<.0001, ηp2=.46 *Occ: F(2.23, 55.74)= 40.98, p=.007, ηp2 = .62 Mo > all (ps<.0001); LE > RE (p=.016) *Llat: F(3,75)= 6.39, p=.001, ηp2 =.2 LE + Mo > RE + No *Rlat: F(2.08,52.21) =6.92, p=.002; ηp2 =.22 RE + LE + Mo > No |

F(3.87,96.7)= 4.41, p=.003, ηp2=.15, *Occ:

F(1.71, 42.7)= 7.48, p=.003, ηp2=.23 RE + Mo < No (ps<.05) *Llat: F(1.79,44.93)= 20.94, p<.0001, ηp2 =.46 RE + Mo < No (ps<.05) *Rlat: F(3,75) =18.87, p<.0001; ηp2=.43 LE + RE + Mo < No (ps<.001) |

F(6,150)= 7.5, p<.0001, ηp2=.23 *Occ: F(2.19, 54.83)= 6.67, p=.002, ηp2=.21 Mo<all (ps<.05) *Llat: no fixation effect *Rlat: F(2.03,50.73) =3.23, p=.047; ηp2=.11 paired comparisons ns |

F(4.01,100.27)= 4.86, p=.001, ηp2=.16 *Occ: F(3, 75)= 4.55, p=.007, ηp2=.15 No<LE (p=.009) *Llat: F(3,75)=6.47, p=.001, ηp2=.21; RE<LE+Mo *Rlat: no fixation effect |

F(4.22,105.37)= 2.48, p=.045, ηp2=.09 *Occ: no fixation effect *Llat: F(2.29,57.45)= 5.25, p=.006, ηp2=.17, RE<Mo (p=.001) *Rlat: F(3,75)= 3.86, p=.019, ηp2=.13 RE<Mo (p=.045) |

| Emotion X Fixation location |

(F(6, 150) = 2.87, p=.023, ηp2=.10 *LE: no emotion effect *RE: no emotion effect *No: F(2,50) = 8.31, p=.001, ηp2 = .25; H<F (p<.001) *Mo: no emotion effect) |

- |

F (6, 150) = 2.62, p=.031, ηp2=.095 *LE: F(2,50) = 5.31, p=.009, ηp2=.175; F<N (p=.009) *RE: F(2,50) = 5.44, p=.01, ηp2=.179; F<H (p=.023); F<N (p=.01) *No: F(2,50) = 7.24, p=.003, ηp2=.225; F<H (p=.026); F<N (p=.005) *Mo: F(2,50) = 16.01, p<.0001, ηp2=.39; F<N; H<N (ps<.001) |

F (4.23, 105.72) = 3.06, p=.018, ηp2=.11 *LE: no emotion effect *RE: F(2,50)=4.21, p=.026, ηp2=.14; F<N (p=.038) *No: no emotion effect *Mo: F(2,50) = 16.81, p<.0001, ηp2=.4; F<N; H<N (ps<.001) |

F (4.32, 107.99) = 3.95, p=.004, ηp2=.14 *LE: no emotion effect *RE: no emotion effect *No: F(1.53,38.43) = 4.69, p=.022, ηp2=.16; H<N (p=.034) *Mo: F(2,50) = 12.58, p<.0001, ηp2=.34; H<F; H<N (ps<.005) |

F (6, 150) = 5.42, p<.001, ηp2=.18 *LE: no emotion effect *RE: no emotion effect *No: no emotion effect *Mo: F(2,50)=26.31, p<.0001, ηp2=.51 H<F; H<N; F<N (ps<.005) |

| Cluster X Emotion X Fixation location |

- |

F(6.5,162.57)= 2.82, p=.01, ηp2=.102 *Occ: emo x fix, F(6,150)= 4.38, p=.001, ηp2 = .15 -LE & RE: no emotion effect -No: H<F (p=.001); H<N (p=.037) -Mo: H<F (p=.001); H<N (p=.001) *Llat: no emo x fix *Rlat: no emo x fix |

- | - | - | - |

Between 50 and 100ms, fixation location interacted with cluster such that a different effect of fixation to the eyes was seen on each hemisphere at lateral clusters, while no fixation effect was seen at occipital sites (Table 5). This different effect of eye fixation depending on the hemisphere was carried across the 100–150ms window (although less clearly) while at occipital sites, amplitudes were most positive when fixation was on the mouth, reminiscent of the P1 effects (Fig.5A). From 150 to 300ms various fixation effects were seen with no clear stable pattern other than more negative amplitudes for the eyes between 150–200ms, paralleling the N170 results.

Small amplitude differences were seen between happy and fearful expressions between 50 and 100ms for nose fixation (emotion by fixation interaction, Table 5). However, as no difference was seen between any emotion and neutral expressions, this sporadic effect is treated as meaningless. As seen in Exp.1, a true emotion effect was first seen during the 100–150ms time window at occipital sites with smaller amplitudes for happy compared to neutral (and fearful) expressions (Fig. 5B), confirming the happiness effect found on P1 peak reported previously. However, in contrast to Exp.1, this effect was seen for the nose and mouth fixations, but not for the eye fixations (cluster by emotion by fixation location interaction, Table 5). The happiness effect was also seen at occipital and right (but not left) lateral sites from 150–300ms (cluster by emotion interactions, Table 5, Fig. 4–6). During that time, the happiness effect was seen only for mouth fixation, as well as for nose fixation during 250–300ms (emotion by fixation interactions, Table 5, Fig.6C).

The fear effect started at 150ms, i.e. after the happiness effect, and lasted until 350ms (Fig.4). This fear effect was seen at left and right lateral sites from 150–300ms and at occipital sites from 150–250ms (cluster by emotion interactions, Table 5, Fig. 4–6). It was seen maximally around 200ms (Fig.6B). From 150–200ms, the fear effect was seen at all fixation locations. From 200–250ms, it was seen at all but the left eye fixation. By 250ms, the effect was no longer seen when fixation was on the eyes, but was still seen for nose and mouth fixations. Finally, from 300–350ms, the fear effect was seen only for mouth fixation (Fig.6C).

3.2.4. Scalp Topographies

The analysis of the mean amplitude differences (fear-neutral and happy-neutral) revealed a significant interaction between the emotion effect and electrode factors for 4 of the 6 time windows. In the 50–100ms window, the emotion effect by electrode interaction was not significant (F(6.43, 160.95)=1.26, p=.27, ηp2=.048). However, the emotion effect by electrode interaction was significant during 100–150ms (F(5.88, 147.21)=9.58, p<.0001, ηp2=.227) and 150–200ms (F(7.1, 177.63)=4.98, p<.0001, ηp2=.166); trending during 200–250ms (F(6.63, 165.84)=1.79, p=.096, ηp2=.067); and significant again during 250–300ms (F(7.26, 181.56)=2.26, p=.03, ηp2=.083) and 300–350ms (F(9.28, 232.22)=1.96, p=.043, ηp2=.073). When normalized amplitudes were used, similar results were found: the emotion effect by electrode interaction was not significant between 50–100ms (F(7.3, 182.48) =1.69, p=.109, ηp2 =.064); was significant between 100–150ms (F(6.48, 162.11)=8.32, p<.0001, ηp2 =.25) and 150–200ms (F(7.73, 193.29)=5.1, p<.0001, ηp2 =.17); was trending during 200–250ms (F(7.85, 196.32)=1.84, p=.073, ηp2=.068) and 250–300ms (F(8.49, 212.47)=1.81, p=.073, ηp2 =.067) and was not significant between 300–350ms (F(10.01, 250.35)=1.48, p=.146, ηp2=.056). Overall, scalp topographies of the fear and happiness effects were similar to those seen in Exp.1 and were different from each other from 100–300ms, but maximally so between 100ms and 200ms (Fig.4).

3.3 Discussion

Using the same gaze-contingent procedure as Exp.1 we investigated the effects of fixation to different facial features on the neural processing of fearful, happy and neutral facial expressions during an oddball detection task that required less attention to the face compared to the emotion discrimination task. Overall, behavioural performance was excellent demonstrating that participants were attending well to the task.

Consistent with Exp. 1, P1 and N170 components were sensitive to fixation location. Fixation effects on the P1 reflected differences in face position on the screen (Fig.1A) whereas effects on the N170 reflected an eye-sensitivity during encoding of the structure of the face (Nemrodov et al., 2014), as discussed in section 2.3. We come back to these effects in the general discussion.

General emotion effects were also consistent with Exp. 1, reproducing the distinct distributions of the effects for fearful and happy expressions. An early happiness effect began on P1 ~100ms and was seen only at occipital sites between 100–150ms during which no fear effect was found. The happiness effect was also seen at occipital and right (but not left) lateral sites between 150–300ms. The fear effect, in contrast, was seen at both occipital and lateral sites between 150–250ms after which time it was seen at lateral sites only (until 300ms). Despite no modulation of the N170 by emotion in Exp. 1, the N170 amplitude was larger for fearful compared to neutral (and happy) expressions in this oddball task. Inspection of the difference waves and topographical maps (Figures 4–6) revealed that the fear effect was extremely similar between the two experiments, starting around or right after the N170 and continuing until 350ms, encompassing the Early Posterior Negativity (EPN; Leppänen et al., 2008; Rellecke et al., 2013; Schupp et al., 2004; see Hinojosa et al., 2015). The reason why this effect starts slightly earlier in some studies (e.g., in the present ODD task) so as to impact the N170, but not in other studies (Exp.1) remains unknown, but could be related to attentional task demands (Hinojosa et al., 2015). However, two recent studies directly comparing tasks reported a lack of significant task by emotion interaction (Rellecke et al., 2012), or an emotional modulation of the N170 in a discrimination task and not in a gender task but only on the right hemisphere (Wronka & Walentoska, 2011). The present study cannot directly address this point given task was a between-subjects factor. More within-subject task comparisons are needed to illuminate this point. Consistent with Exp.1, there was no early effect of fear on the P1. Previous reports of early fear effects in oddball detection tasks (e.g., Batty & Taylor, 2003) may have been driven by uncontrolled low-level stimulus properties.

The emotion effects for happy and fearful expressions also interacted with fixation to facial features. The happiness effect was seen only during fixation to the mouth between 100–350ms (except during 250–300ms where it was also seen for nose fixation). The mouth thus seems to provide important information for the processing of happy expressions, both early, during a stage that is most likely reflecting sensitivity to the low-level cues of the smile, and later, during the processing of the emotional content of the face (EPN). We come back to these effects in the general discussion.

The fear effect interacted with fixation location during several time windows. Between 150–200ms, the fear effect was seen for all fixation locations. By 250ms, the effect was no longer seen for eye fixations but was still seen for nose and mouth fixations and remained seen only for mouth fixation from 300–350ms (Fig. 6C). Thus, information provided by the mouth and the eyes appears to be critical to process the emotional content of fearful expressions even when attention is not directed to the emotional content of the face, as in this oddball task.

4. General Discussion

Combining ERP and eye-tracking recordings using a gaze-contingent procedure, the current study tested the impact of fixation to the eyes and mouth on the neural processing of whole fearful and happy expressions, and whether this differed between an emotion-relevant (Exp. 1) and an emotion-irrelevant (Exp. 2) tasks. Effects of fixation location were seen for the P1 and N170 components, with an eye-sensitivity specific to the N170. Remarkably similar emotion effects were seen in both experiments, with only a few differences between the two tasks. Importantly, these emotion effects interacted with fixation location, revealing an important role of the mouth for processing happy expressions and for both the mouth and the eyes for processing fearful expressions.

4.1. P1 sensitivity to face position