Abstract

A critical aspect of mitosis is the interaction of the kinetochore with spindle microtubules. Fission yeast Mal3 is a member of the EB1 family of microtubule plus-end binding proteins, which have been implicated in this process. However, the Mal3 interaction partner at the kinetochore had not been identified. Here, we show that the mal3 mutant phenotype can be suppressed by the presence of extra Spc7, an essential kinetochore protein associated with the central centromere region. Mal3 and Spc7 interact physically as both proteins can be coimmunoprecipitated. Overexpression of a Spc7 variant severely compromises kinetochore–microtubule interaction, indicating that the Spc7 protein plays a role in this process. Spc7 function seems to be conserved because, Spc105, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog of Spc7, identified by mass spectrometry as a component of the conserved Ndc80 complex, can rescue mal3 mutant strains.

INTRODUCTION

Segregation of chromosomes requires the association of spindle microtubules and chromosomes. Attachment of the mitotic spindle fibers occurs at a multicomponent protein complex, the kinetochore, that is assembled on centromeric DNA. This DNA region differs greatly in structure and size among various organisms (reviewed in Pidoux and Allshire, 2000; Cleveland et al., 2003). The budding yeast centromere DNA is the simplest one described and consists of a very well defined 125-base pair region, whereas in higher eucaryotes, centromeric DNA is made up of highly repetitive sequences encompassing up to millions of base pairs. The centromere DNA of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe lies in between these two extremes: it occupies between 40 and 100 kb on each chromosome and is composed of a central region flanked by inner and outer repetitive sequences. To date, proteins found to be associated with these regions either bind to the central core region or to the outer repeats, thus pointing to the existence of two distinct domains in the fission yeast centromere (reviewed in Pidoux and Allshire, 2000). The heterochromatic outer repeats are required for centromere cohesion (reviewed in Bernard and Allshire, 2002), whereas the central region is needed for the assembly of the kinetochore per se (Saitoh et al., 1997; Goshima et al., 1999; Jin et al., 2002; Pidoux et al., 2003). However, in spite of the different cis-acting DNA requirements, a substantial number of kinetochore proteins have been conserved from yeast to humans, among them the four-component Ndc80 complex. This complex is required for kinetochore–microtubule association and spindle checkpoint signaling (He et al., 2001; Janke et al., 2001; Wigge and Kilmartin, 2001; Bharadwaj et al., 2004; McCleland et al., 2004).

The spindle microtubules that attach to kinetochores are highly dynamic structures that alternate between phases of growth and shrinkage (Kirschner and Mitchison, 1986). This dynamic behavior is also observed after microtubules are attached to kinetochores and is coregulated by components of the kinetochore complex and microtubule plus-end associated proteins. The role of kinetochore motors such as CENP-E–and Kin1-related proteins in this process has been amply documented (reviewed in McIntosh et al., 2002; Cleveland et al., 2003; Mimori-Kiyosue and Tsukita, 2003). Microtubule plus-end proteins also have been implicated in the local control of microtubule dynamics and in the attachment of microtubules to kinetochores. Members of the CLIP170 family are associated transiently with prometaphase kinetochores and are required for kinetochore–microtubule attachment (Dujardin et al., 1998; Lin et al., 2001). Recently, the nonmotor microtubule-associated protein (MAP) family CLASP has been identified as CLIP170/CLIP115 interaction partners (Akhmanova et al., 2001; Maiato et al., 2003). CLASP1 has been shown to localize near growing spindle microtubule plus-ends and at the outer corona kinetochore region and is required for microtubule dynamics at the microtubule–kinetochore interface (Akhmanova et al., 2001; Maiato et al., 2003).

Another functionally conserved group of plus-end MAPs is the EB1 family that includes the S. pombe Mal3 protein (reviewed in Beinhauer et al., 1997; Tirnauer and Bierer, 2000). Human EB1 was originally identified as an interaction partner of the adenomatous polyposis coli tumor suppressor APC (Su et al., 1995). Members of this family localize along microtubules, but they are preferentially associated with microtubule plus-ends, regulate microtubule dynamics, and have an important role in the interaction of the microtubule cytoskeleton with other cellular structures (reviewed in Tirnauer and Bierer, 2000; Schuyler and Pellman, 2001; Gundersen and Bretscher, 2003; Mimori-Kiyosue and Tsukita, 2003). Recently, EB1 and APC have been shown to localize to kinetochores, indicating an involvement in chromosome capture (Fodde et al., 2001; Kaplan et al., 2001). This association of EB1 is restricted to polymerizing microtubules pointing to a role for EB1 in regulating microtubule dynamics at the microtubule–kinetochore interface (Tirnauer et al., 2002a). Fission yeast Mal3 was identified in a screen for components required for genome stability, and although loss of the protein is not lethal it leads to increased chromosome loss and altered microtubule dynamics (Beinhauer et al., 1997). In addition, mal3 mutant cells showed a significant increase in the number of cells with condensed chromosomes, indicating defects in early aspects of mitosis (Beinhauer et al., 1997). To better understand the role of Mal3 in mitosis, we conducted a screen for extragenic suppressors of the mal3 mutant phenotype. We identified a total of 10 suppressors that were able to rescue the chromosome loss phenotype of the mal3 mutant strain. The most frequently isolated extragenic suppressor, the spc7+ gene, codes for an essential kinetochore protein that seems to interact with Mal3 at the microtubule–kinetochore interface.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Media

Genotypes of strains are listed in Table 1. For determination of genetic interaction at least three double mutants were tested per cross. S. pombe strains were grown in rich or minimal medium (YE5S, or EMM and MM) with appropriate supplements (Moreno et al., 1991). G418 resistance was scored on 100 mg/l G418 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). EMM with 5 μg/ml thiamine repressed the nmt1+ promoter. For high-level expression from the nmt1+ promoter cells were grown in thiamine-less liquid EMM for 18–22 h at 30°C. Suppression of thiabendazole (TBZ) hypersensitivity was monitored on selective MM with 5–7.5 μg/ml TBZ. Suppression of minichromosome loss was assayed as described (Beinhauer et al., 1997). Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains were grown in rich medium (YPD) or selective medium (SD) with appropriate supplements (Kaiser et al., 1994). Suppression of TBZ hypersensitivity was tested on selective SD with 75 μg/ml TBZ or YPD with 50–100 μg/ml TBZ; resistance to G418 on YPD containing 200 mg/l G418. For repression of the tetO-CYC1 promoter, cells were grown in nonselective SD containing 100 μg/ml doxycycline.

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Name | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| UFYS135 | h+ mal3Δ::his3+ ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3Δ | U. Fleig |

| UFYS0203 | h- mal3-1 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D6 Ch16[ade6-M216] | U. Fleig |

| UFY177 | h+ mal2-GFP/kanR ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | U. Fleig |

| UFY25CX | h+ spi1-25 leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-D6 his3Δ[ρ] | U. Fleig |

| KG425 | h- ade6-M210 leu1-32 his3Δ ura4-D18 | K. Gould |

| KG554 | h+ ade6-M216 leu1-32 his3Δ ura4-D18 | K. Gould |

| h- mal3-pkGFP/ura4+ ade6-M210 leu1-32 his3Δ ura4-D18 | H. Browning | |

| YUG37 | MATa ura3-52 trp1Δ63 GAL2 LEU2-tTA(leu2::pCM149) | J. Hegemann |

| YSH12 | MATa ura3-52 trp1-289 leu2-3112 his3Δ1 bim1:: kanR | J. Hegemann |

| UFY155 | h- spc7-GFP/KanR ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D6 | This study |

| UFY617 | h- spc7-HA/KanR ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D6 Ch16[ade6-M216] | This study |

| UFY498 | h+ spc7-HA/KanR mal2-GFP/KanR ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D6 | This study |

| UFY496 | h- spc7-GFP/KanR mal3Δ::his3+ ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4 his3Δ[ρ] | |

| UFY466 | h+ spc7-GFP/KanR nda3-KM311 ade6 leu1-32 ura4-D6 | This study |

| UFY637 | h+ mal3-pkGFP/ura4+ spc7-HA/KanR adeM-210 leu1-32 ura4-[ρ] | This study |

| UFY639 | h- mal3-pkGFP/ura4+ spc7-HA/KanR cut9-665 ade6-M210 leu1-32 | This study |

| UFY724 | h- mal2-1 spc7-GFP/KanR ade6-M210 ura4-[ι] Ch16[ade6-M216] | |

| UFY693 | h- spc7-GFP/KanR spi1-25 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D6 | This study |

| YJO359 | MATa ade2-101 trp1-Δ63 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 lys2-801 SPC105-ProA::His3MX6 sst1::loxP | This study |

| UFY699 | MATa ura3 trp1 bim1:: kanR LEU2-tTA (leu2:: pCM149) SPC105(-50, -1):: tetO-CYC1/KanR | This study |

| YCJ341 | ade2-101 trp1-Δ63 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 lys2-801 SPC24-ProA::His3MX6 cdc16-1::LYS2 | This study |

Identification of spc7+ and DNA Methods

Multicopy extragenic suppressors of the mal3 mutant phenotypes were isolated by transformation of the mal3-1 strain with a S. pombe genomic bank (Barbet et al., 1992). Ura+ transformants were replica-plated twice onto MM plates containing 7.5 μg/ml TBZ. Plasmids were isolated from transformants able to grow on TBZ-containing media and tested for the ability to rescue the increased minichromosome loss phenotype of the mal3-1 strain by visual screening for the suppression of colony sectoring (Niwa et al., 1986; Beinhauer et al., 1997).

The 2.7-kb-long SPC105 open reading frame (ORF) was expressed from the modified nmt1 promoter in S. pombe plasmid pJR2–41 × U or from the MET25 promoter in the 2μ–containing S. cerevisiae plasmid pRS473MET25. Correct annotation of the SPCC1020.02 ORF was confirmed by amplification of this ORF via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by using a S. pombe cDNA Bank (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA).

A spc7 null allele (Δspc7) was generated by replacing the internal 3.06 kb of the 4.09 Kb spc7+ ORF with the his3+ marker in the diploid strain KG425 × KG554. Tetrad analysis of 28 heterozygous Δspc7/spc7+ diploids revealed that only the 2 his– spores/tetrad grew.

Immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) by using S. pombe strains was performed as described previously (Jin et al., 2002). Strains were shifted to 18°C for 2 h before fixation with 3% paraformaldehyde. Strains containing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged Spc7 or Mal2 were used for ChIP. Two microliters of rabbit anti-GFP antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used in the ChIP, and 25 μl of protein A agarose (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Multiplex PCR with TaqDNA polymerase (Roche Diagnostics) was used for analysis of centromeric chromatin in crude extracts and immunoprecipitates, by using the primer pairs for cnt (central core), otr (outer repeat), and fbp1+ (euchromatic control) as described previously (Jin et al., 2002) and the imr (inner most repeat) pair: 5′-GGATATATGTATTCTTGCACTC-3′ and 5′-GGCTACCAGCAT TGTTATTCATAACC-3′. PCR reactions contained 1.25 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM dNTPs, 2 μl ChIP sample, or 2 μl of 1/10 dilution of crude sample, with 50 ng of each primer in a 25-μl reaction.

For coimmunoprecipitation, wild-type strains or a cut9-665 strain incubated for 4 h at 36°C were washed once with STOP buffer (0.9% NaCl, 1 mM NaN3, 10 mM EDTA, and 50 mM NaF). Approximately 1 × 109 cells were resuspended in 80 μl of HEPES-lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and Complete protease inhibitor; Roche Diagnostics) and lysed using glass beads. Then, 450 μl of HEPES buffer was added, and samples were centrifuged twice for 30 min in a microfuge at 4°C. A 150-μl amount of each sample was incubated on ice for 1 h with 50 μl of antihemagglutinin (HA) MicroBeads or anti-GFP MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Immunoprecipitates were isolated using the μMACS epitope-tagged protein isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec), except that the immune complexes were washed for maximally 5 min. After elution, the immune complexes were boiled, resolved on SDS-7% polyacrylamide gels, and blotted onto Immobilon-P (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Because Spc7-HA is a 158-kDa protein and Mal3-GFP a 62-kDa protein, blots were cut in half and the top half (>85-kDa proteins) was probed with anti-HA antibody (monoclonal mouse; Roche Diagnostics) and the bottom half with anti-GFP antibody (polyclonal rabbit; Molecular Probes). Immobilized antigens were detected using the ECL Advance Western blotting kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Affinity Purification and Matrix-assisted Laser Desorption Ionization/Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) Analysis

We lysed 4000 OD of cells in 15 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 140 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM NaF, 100 mM glycerophosphate, and protease inhibitors) with glass beads. The cleared lysate was incubated with 200 μl of IgG-agarose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 4 h at 4°C. Subsequently, the agarose was washed with 20 ml of lysis buffer, 20 ml of wash buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 250 mM LiCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.5% NP 40) and 1 ml of 5 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.0). The sample was eluted with 2 ml of 500 mM ammonium acetate (pH 3.4), dried, and subjected to PAGE plus MALDI-TOF analysis a described previously (Shevchenko et al., 1996).

Microscopy

For S. pombe cells, photomicrographs were obtained using a Zeiss Axiovert200 fluorescence microscope coupled to a charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu Orca-ER) and Openlab imaging software (Improvision, Coventry, United Kingdom). Immunofluorescence microscopy was done as described previously (Hagan and Hyams, 1988; Bridge et al., 1998). For tubulin staining, primary monoclonal anti-tubulin antibody TAT1 (Woods et al., 1989) followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or Cy3-conjugated secondary sheep anti-mouse antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) were used. Strains expressing HA- and GFP-fusion proteins were observed in fixed cells by indirect immunofluorescence with mouse anti-HA antibody (Covance, Princeton, NJ) followed by Cy3-conjugated sheep anti-mouse antibodies (Sigma) and rabbit anti-GFP (Molecular Probes) followed by FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich). Processed cells were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) before mounting.

RESULTS

Identification of spc7+ as a Suppressor of the mal3 Mutant Phenotype

S. pombe strains carrying a mutant mal3 allele are hypersensitive to microtubule-destabilizing drugs such as TBZ and show a 400-fold increase in the loss of a nonessential minichromosome (Beinhauer et al., 1997). Furthermore, a Δmal3 (mal3 deletion) cell population showed a fourfold increase in the number of undivided condensed chromosomes compared with a wild-type strain (Beinhauer et al., 1997). In addition, the spindle checkpoint that monitors the correct alignment of chromosomes on the spindle seems to be activated in Δmal3 cells. Double-mutant strains of Δmal3 with a null allele of mph1+, which is an evolutionarily conserved component of the spindle checkpoint pathway (He et al., 1998), showed reduced growth compared with the single mutant strains (our unpublished data). To clarify the role of the Mal3 protein in mitosis, we conducted a search for multicopy suppressors of the mal3 mutant mitotic phenotypes (see Materials and Methods). Apart from the wild-type mal3+ ORF, we identified a total of 10 genes that were able to suppress the hypersensitivity to TBZ and the increased minichromosome loss of the mal3-1 strain (Vietmeier-Decker and Fleig, unpublished data). The screen was saturating as most suppressors were isolated several times.

A previously uncharacterized ORF with the systematic name SPCC1020.02 (S. pombe genome project at the Sanger Institute) was isolated most frequently, namely, 26 times, in this screen. We named this ORF spc7+ (S. pombe centromere). According to the sequence annotation of the S. pombe genome, the spc7+ ORF is 4095 base pairs in length and codes for a 153.5-kDa protein. We confirmed the annotation of this ORF by identification of a cDNA clone that contained the entire coding sequence (see Materials and Methods). The presence of extra spc7+ rescued the TBZ hypersensitivity and the increased loss of a nonessential minichromosome of the mal3-1 strain (Figure 1, A and B, respectively). Extra spc7+ also rescued the TBZ hypersensitivity of Δ mal3 and all other mal3 mutant strains tested (Figure 1A; our unpublished data), implying that suppression by spc7+ is not allele specific and can occur even in the absence of mal3+. The original genomic clone that suppressed the mal3 phenotypes only contained the last 2028 base pairs of the 4095-base pair-long spc7+ ORF. This fragment rescued as well as full length spc7+ (our unpublished data). The first in frame ATG was predicted to give rise to a Spc7 variant without the N-terminal 820 amino acids. To test whether this prediction was correct, the C-terminal 1635-base pair region of the spc7+ ORF was expressed from the modified nmt1 promoter in S. pombe plasmid pJR2–41 × U (Moreno et al., 2000). This Spc7 variant (Spc7-C) was able to fully suppress the mal3 phenotypes (our unpublished data).

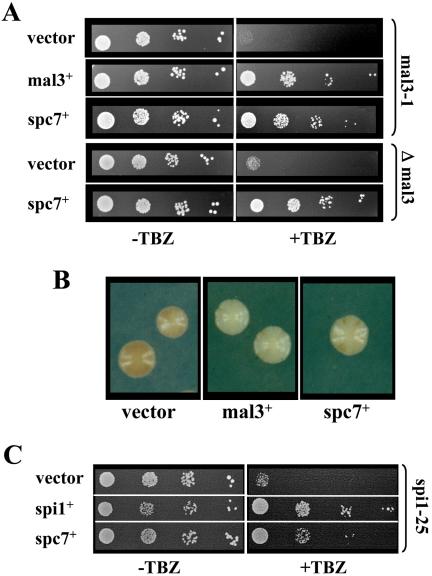

Figure 1.

spc7+ suppresses the phenotypes of mal3 and spi1-25 mutant strains. (A) TBZ hypersensitivity of the mal3-1 and Δmal3 strains is rescued by extra spc7+. Left and right, serial dilution patch tests (104 to 101 cells) of mal3-1 and Δmal3 transformants grown under selective conditions in the absence (–TBZ) or presence (+TBZ) of 7 μg/ml thiabendazole for 5 d at 24°C. Vector control indicates plasmid without insert; mal3+ denotes the presence of wild-type mal3+ on a plasmid. (B) Minichromosome loss phenotype of the mal3-1 strain, indicated by adenine auxotrophy and numerous red sectors in a white colony (vector), is rescued by the presence of mal3+ or spc7+ on a plasmid. Plates were incubated at 24°C. (C) TBZ hypersensitivity of the spi1-25 strain is rescued by extra spc7+. Panels show serial dilution patch tests of spi1-25 transformants grown under selective conditions in the absence (–TBZ) or presence (+TBZ) of 7 μg/ml TBZ for 5 d at 24°C. Vector control indicates plasmid without insert, whereas spi1+ denotes the presence of wild-type spi1+ on a plasmid.

We had tested for genetic interaction between mal3+ and other genes encoding microtubule plus-end–associated proteins such as dis1+ and alp14+/mtc1+, which encode members of the TOG/XMAP215 family (Ohkura et al., 1988; Nabeshima et al., 1995; Garcia et al., 2001; Nakaseko et al., 2001). No genetic interaction was observed between Δmal3 and the mutant dis1-288 allele. However, Δalp14 Δmal3 double mutants were synthetically lethal at all temperature tested, thus indicating that the two proteins have a role in the same essential process. We therefore assayed whether extra spc7+ could also rescue the mutant phenotypes of an Δalp14 strain (Garcia et al., 2001) but found that spc7+ was unable to rescue the temperature sensitivity or the TBZ hypersensitivity of the Δalp14 strain (our unpublished data).

Identification of spc7+ as a Suppressor of SpRan Mutant Phenotype

We have previously reported the characterization of a partial loss of function mutant of the S. pombe Ran GTPase Spi1 that led to aberrant mitosis and severe genome instability (Fleig et al., 2000). Strains carrying this specific mutation, named spi1-25, were hypersensitive to TBZ. This mutant phenotype was suppressed partially by the presence of extraMal3 (Fleig et al., 2000). A multicopy suppressor analysis identified several other genes that could rescue the spi1-25 TBZ hypersensitivity (Karig and Fleig, unpublished data). Among them was the spc7+ ORF. As shown in Figure 1C, plasmid-borne expression of spc7+ partially suppressed the TBZ hypersensitivity of the spi1-25 strain. In addition, spc7+ also rescued partially the temperature sensitivity of the spi1-25 strain (our unpublished data).

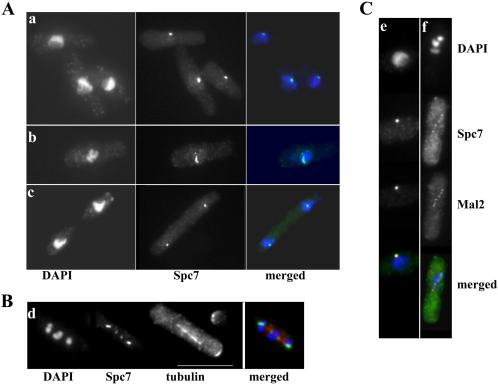

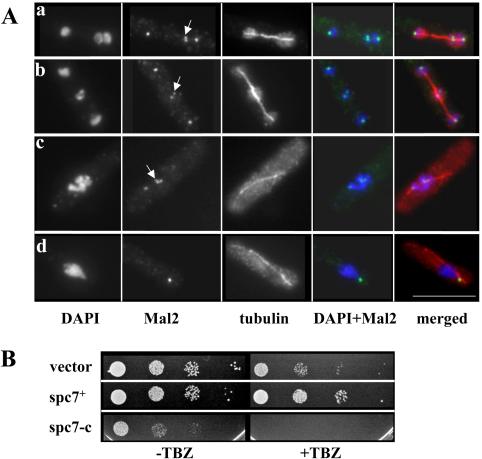

Spc7 Is an Essential Component of the Fission Yeast Kinetochore

To determine whether spc7+ was essential for vegetative growth, one copy of the spc7+ ORF was replaced with the his3+ marker in a diploid strain (see Materials and Methods). Sporulation and subsequent tetrad analysis of this strain revealed that only two of the four spores in a tetrad could grow into a colony, and these were always his–, indicating that spc7+ is an essential gene. To determine the subcellular localization of Spc7, a fluorescence-improved version of GFP was fused to the COOH-terminal end of the endogenous spc7+ coding region. The strain expressing the Spc7 fusion protein was indistinguishable in phenotype from the isogenic wild-type strain, indicating that the tagged gene was functional. Immunofluorescence analysis of interphase cells expressing Spc7-GFP revealed a single fluorescent dot near the nuclear periphery, whereas early mitotic cells showed up to six dots associated with the condensed chromatin (Figure 2A, a and b, respectively). Anaphase cells showed two Spc7-GFP dots that cosegregated with the separated chromatin (Figure 2A, c). Cells arrested in mitosis by overexpression of the spindle checkpoint component Mph1 (He et al., 1998) showed up to six fluorescent signals: two signals colocalized with each of the three duplicated chromosomes positioned on a short spindle (Figure 2B). Because this type of localization is characteristic of S. pombe kinetochore proteins, we compared the intracellular localization pattern of the Spc7 fusion protein with that of the known kinetochore protein Mal2 (Jin et al., 2002). For this purpose, a strain was used in which the endogenous spc7+ ORF had been tagged with the HA epitope and the endogenous mal2+ ORF fused to the GFP ORF. Colocalization of the Spc7 and Mal2 fusion proteins was observed in interphase and mitotic cells (Figure 2C, e–f) in all cells analyzed (n = 150). Interestingly, in interphase cells 71% of cells had the Mal2 signal closer to the nuclear periphery than the Spc7 signal (n = 76) (Figure 2C, e). Together, these data imply that the Spc7 protein is a component of the fission yeast kinetochore that localizes at centromeres throughout the cell cycle.

Figure 2.

Spc7 localizes to the kinetochore. (A) Localization of the Spc7-GFP protein in wild-type cells in interphase (a) early (b) or late (c) stages of mitosis. Fixed cells were stained with DAPI and anti-GFP antibody. (B) Localization of the Spc7 fusion in a wild-type cell arrested by overexpression of mph1+. GFP signals; spindles and condensed chromosomes were simultaneously observed by staining with anti-GFP antibody, anti-tubulin antibody and DAPI. (C) Colocalization of Spc7-HA (green) and Mal2-GFP (red) fusion proteins in interphase cells (e) and cells arrested by overexpression of mph1+ (f). Chromosomes, HA- and GFP-signals were simultaneously observed by staining with anti-GFP antibody, anti-HA antibody, and DAPI. Bar, 10 μm.

We next determined by immunofluorescence analysis whether the subcellular localization of Spc7-GFP was affected in the temperature-sensitive spi1-25 and mal2-1 strains, the cold-sensitive nda3-KM311 (β-tubulin) strain, and the Δmal3 strain (Umesono et al., 1983; Fleig et al., 1996, 2000; Beinhauer et al., 1997). For this purpose, the endogenous spc7+-GFP ORF was crossed into these strains. At the restrictive temperature, Spc7-GFP was localized correctly in the Ran mutant strain spi1-25 and the mal2-1 strain, which encodes a defective kinetochore component (Jin et al., 2002). Furthermore, kinetochore localization of Spc7 was not affected in the nda3-KM311 mutant strain at the nonpermissive temperature, implying that an intact microtubule-cytoskeleton is not required for Spc7 localization (our unpublished data).

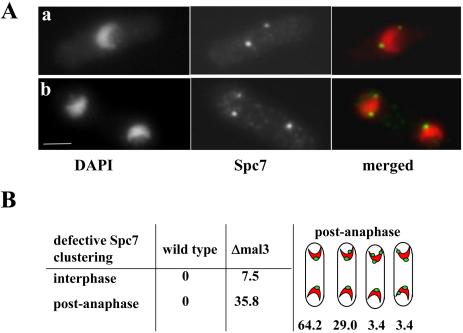

As described previously, the Δmal3 population showed a fourfold increase in the number of cells with condensed chromosomes, indicating an early mitotic defect. Immunofluorescence analysis of these fixed cells revealed that the majority (>90%, n = 76) showed six fluorescent Spc7-GFP dots on a metaphase spindle (3 × 2 sister centromeres; our unpublished data). No severe anaphase defects were observed. However clustering of the Spc7 protein at the spindle pole body (SPB) was affected severely in postmitotic Δmal3 cells. In wild-type cells, centromeres and the associated kinetochore proteins cluster adjacent to the SPB in interphase cells, and this association with each other and the SPB is only disrupted in M phase (Funabiki et al., 1993; Ekwall et al., 1995; Saitoh et al., 1997). Δmal3 G2 interphase cells (7.5%) showed instead of the expected single Spc7-GFP signal, two dots associated with the nuclear periphery (Figure 3A, a). The brighter one of these dots colocalized with the SPB by using the Cut12 SPB marker (our unpublished data; Bridge et al., 1998). Interestingly, >35% of Δmal3 postanaphase cells showed two or rarely three Spc7-GFP signals per nucleus (Figure 3A, b and B). These data demonstrate that the Mal3 protein is required for SPB clustering of Spc7, especially in postanaphase cells. However Mal3 is not per se required for clustering of centromeres/kinetochores at the SPB. Microscopic examination of Δmal3 cells expressing the GFP-tagged Mal2 kinetochore protein always revealed a single fluorescent dot in G2 cells and two Mal2-GFP dots that colocalized with the separated chromatin in postanaphase cells (our unpublished data; Jin et al., 2002). Because Spc7 clustering does not require an intact microtubule cytoskeleton, it is possible that SPB-associated Mal3 is required for Spc7 clustering. A Dictyostelium member of the EB1 family has been shown to be a genuine component of the centrosome (Rehberg and Graf, 2002).

Figure 3.

Clustering of Spc7 is defective in a Δmal3 strain. (A) Localization of the Spc7-GFP fusion protein in Δmal3 cells in G2 (a) and postanaphase (b) cells. Fixed cells pregrown at 24°C were stained with DAPI and anti-GFP antibody. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Shown are the percentages of interphase cells (G2) (n = 120) and postanaphase cells (n = 174) that have more than one Spc7 signal per nucleus. The right-most panel shows the various distributions observed for the Spc7 signal in Δmal3 postanaphase cells. Red, chromatin; green, Spc7-GFP signal.

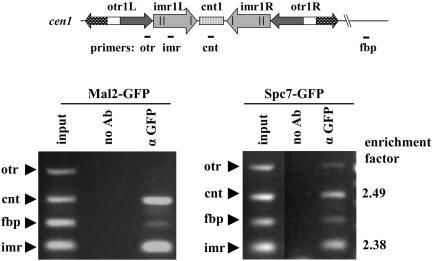

Spc7 Is Associated with the Central Core Region of the Fission Yeast Centromere

The centromeric DNA of S. pombe is 40–100 kb in size and consists of a central core (cnt) flanked by arrays of inner (imr/B) and outer repeats (otr/K+L) (Figure 4 shows the centromeric DNA of chromosome I) (reviewed in Clarke, 1998). To identify the centromere region with which the Spc7 protein associates, ChIP was carried out (Partridge et al., 2000). Cells expressing either Mal2-GFP or Spc7-GFP fusion proteins were analyzed in ChIP assays by using anti-GFP antibodies. DNA present in crude extracts or immunoprecipitates by using anti-GFP antibodies were analyzed by multiplex PCR, by using primers to amplify the cnt, imr, and otr regions in the centromere of chromosome I and an unrelated euchromatic control region fbp. As previously reported, the Mal2 protein associates with the central core region as shown by a specific enrichment of the cnt and imr sequences in the Mal2-GFP ChIP (Jin et al., 2002) (Figure 4). The Spc7 ChIPs also showed an enrichment of the cnt and imr sequences. These DNA sequences were enriched 2.5- and 2.4-fold, respectively, relative to the fbp DNA in Spc7 ChIPs in comparison with the input control. The otr sequence was not enriched in Spc7 ChIPs. These data indicate an association of the Spc7 fusion protein with the central domain of the centromere and imply an involvement of this domain in kinetochore–microtubule attachment. Interestingly, the enrichment of the cnt and imr sequences in Spc7 ChIPs was repeatedly and reproducibly approximately two-fold lower compared with Mal2 ChIPs (Figure 4; our unpublished data).

Figure 4.

Spc7 is associated with the central domain of cen1. Cells expressing Spc7-GFP or Mal2-GFP were fixed and processed for ChIP by using anti-GFP antibodies. Chromatin in immunoprecipitates and crude extracts was analyzed by multiplex PCR, by using primers to amplify regions in cen1: cnt, imr, otr, and an euchromatic negative control locus, fbp. cnt and imr sequences are specifically enriched in ChIPs of proteins associated with the central domain such as the Mal2 fusion protein. The cnt and imr sequences are also enriched in Spc7-GFP ChIPs, indicating association of the Spc7 fusion protein with the central centromere domain.

Spc7 Affects Kinetochore–Microtubule Interactions

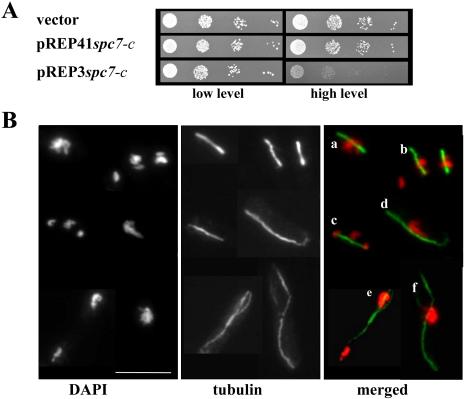

We had found that wild-type cells expressing full-length Spc7 from the modified nmt1 promoter (pREP41; moderate overexpression) had no visible effect on the growth of the cells, nor did overproduction from the wild-type nmt1+ promoter (pREP3; strong overexpression) (our unpublished data). Moderate overproduction of the C-terminal part of Spc7 (Spc7-C), which is sufficient to suppress the mal3 mutant phenotypes, also showed no effect on cell growth (Figure 5A, middle). However, strong overproduction of this Spc7 variant, which is still able to associate with the kinetochore (our unpublished data), led to severe growth inhibition (Figure 5A, bottom). The growth inhibition was not due to a simple displacement of the full-length Spc7 protein by Spc7-C at the kinetochore. The Spc7-GFP fusion protein was properly localized in wild-type cells overexpressing spc7-c (our unpublished data). To assay the consequences of Spc7-C overproduction, we looked at immunofluorescence staining of a wild-type strain overexpressing spc7-c for 18–22 h. Although interphase cells showed no obvious abnormalities, cells undergoing mitosis were severely affected. After 18 h of induction, 24% of the cells in a population were in mitosis, and this number increased to 40% at later time points (22 h). Sixty-seven percent of mitotic cells showed severe chromosome segregation defects and cells with a “cut” phenotype became more frequent (Figure 5B; our unpublished data). Two predominant defective chromosome resolution phenotypes were observed: 1) no separation of highly condensed chromatin on an elongating spindle (Figure 5B, cells a, d, and f) and 2) unequal segregation of the chromatin (Figure 5B, cells b, c, and e). In the first phenotypic class, chromosomes were not separated on an elongating spindle. Using the Mal2 protein as a kinetochore marker we found 1) that association of Mal2 with the kinetochore was unaffected by Spc7-C overexpression and 2) that not all kinetochores in these cells were associated with the mitotic spindle (Figure 6c, nonattached kinetochore marked by an arrow). In cells where the chromatin had an arrow like appearance, kinetochores were clustered at the “tip” of the arrow (Figure 6d). The second phenotypic class consisted of chromatin that was segregated asymmetrically. Part of the chromosomes were found at one end of a short anaphase spindle (Figure 5B, cell b) or only part of the chromosomal material had been segregated to the two ends of the spindle, whereas the rest remained unseparated at the equatorial plate (Figure 5B, cell c). Rarely, we also observed fully elongated spindles showing asymmetric segregation of the chromosomes (Figure 5B, cell e). Cells belonging to the second phenotypic class often contained kinetochores that did not seem to be attached to spindle microtubules (Figure 6, a and b). We repeated the above-mentioned experiment using a second kinetochore marker, namely, Spc24, and obtained similar results (our unpublished data; Wigge and Kilmartin, 2001).

Figure 5.

Overexpression of a Spc7 variant in a wild-type strain leads to growth inhibition and severe mitotic defects. (A) Spc7-C was expressed from two different versions of the regulatable nmt1+ promoter. pREP3 gives rise to strong and pREP41 to moderate overexpression. Shown are serial dilution patch tests (104 to 101 cells) of transformants grown under selective conditions for 4 d at 30°C. (B) Photomicrographs of wild-type cells overexpressing spc7-c from pREP3. Fixed cells were stained with anti-tubulin antibody and DAPI. Shown is a composite of cells displaying various mitotic defects: nonseparated chromatin (a, d, and f) or unequally/partially divided chromatin on elongating spindles (b, c, and e). Bar, 10 μm.

Figure 6.

Association between spindle and kinetochore is altered by Spc7-C overproduction. (A) Photomicrographs of mal2+-GFP cells overexpressing spc7-c. Fixed cells were stained with DAPI, anti-GFP and anti-tubulin antibody. Shown are elongating spindles without or with unequal segregation of the chromatin. Merged images show chromatin, Mal2-GFP, and the spindle. The arrows indicate kinetochores not attached to the spindle. Bar, 10 μm. (B) Overexpression of Spc7 or Spc7-C from pREP3 alters sensitivity to microtubule-destabilizing drug TBZ. Left and right, serial dilution patch tests (104 to 101 cells) of wild-type transformants expressing high levels of spc7+ or spc7-c in the absence or presence of TBZ. Vector control indicates plasmid without insert.

Interestingly, overexpression of full-length Spc7 or Spc7-C from the wild-type nmt1+ promoter in a wild-type strain led to differences in the sensitivity to TBZ. As shown in Figure 6B, overproduction of full-length Spc7 leads to increased resistance to the microtubule-destabilizing drug TBZ, whereas overexpression of the Spc7 variant Spc7-C gave rise to the opposite effect.

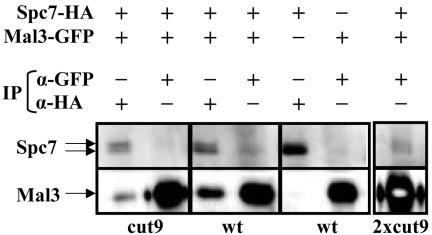

Spc7 Coimmunoprecipitates with Mal3

Given the finding that extra spc7+ could suppress the mitotic phenotypes of mal3 mutant strains, we investigated whether the Mal3 and Spc7 proteins interacted. For this purpose, we tested whether Spc7 coimmunoprecipitated Mal3 and vice versa. Immunoprecipitation with anti-GFP or anti-HA antibodies was carried out with protein extracts from strains expressing endogenous Mal3-GFP and/or Spc7-HA. These immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by Western blotting by using anti-GFP and anti-HA antibodies. As shown in Figure 7 immunoprecipitation of Spc7-HA clearly coimmunoprecipitates Mal3-GFP in wild-type cell extracts. We also could coimmunoprecipitate Mal3-GFP with anti-HA antibodies from mitotically arrested cut9-665 extracts (Figure 7). cut9+ codes for a subunit of the anaphase promoting factor (Yamada et al., 1997). Furthermore, immunoprecipitation of Mal3-GFP also coimmunoprecipitated Spc7-HA although the amount of Spc7-HA that was coimmunoprecipitated was low (Figure 7). Western blot analysis showed the existence of two Spc7-HA specific bands. Our preliminary analysis indicates that the slower migrating form is phosphorylated and the predominant form in cut9-665–arrested cells (our unpublished data; Figure 7). Both forms could be coimmunoprecipitated by Mal3. Our data thus imply that the Mal3 and Spc7 proteins interact with each other. Interestingly, we were unable to coimmunoprecipitate Spc7 and Mal3 upon prolonged washing steps, indicating that the interaction between Mal3 and Spc7 is not a stable one.

Figure 7.

Spc7 and Mal3 coimmunoprecipitate. Protein extracts were prepared from wild-type (wt) and cut9-665 (cut9) strains expressing Spc7-HA, Mal3-GFP, or both. Lysates were halved: one half was used for immunoprecipitation (IP) with an anti-HA antibody, and the other with an anti-GFP antibody. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, blotted to Immobilon-P, and cut in half at the 85-kDa size marker. The top half was probed with anti-HA antibody, and the bottom half with anti-GFP antibody. Immobilized antigens were detected using the ECL kit. Positions of Spc7 and Mal3 are indicated by arrows. The right most lane (2 × cut9) is identical to lane 2 except that twice the amount of immunoprecipitate was used. This illustrates more clearly the coimmunoprecipitation of Spc7-HA by Mal3-GFP.

Spc7 Belongs to a Conserved Protein Family That Copurifies with the Conserved Ndc80 Complex

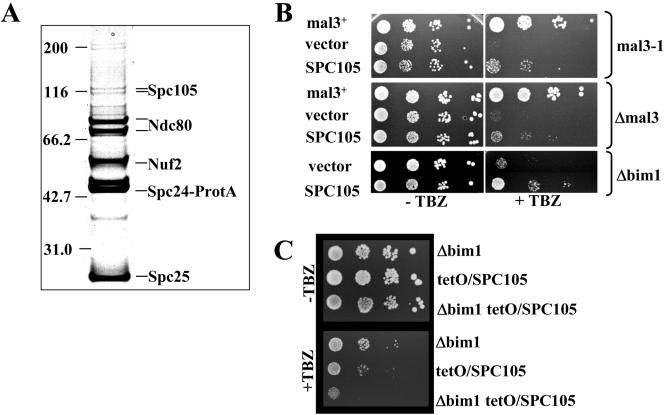

Database searches using PEDANT at MIPS identified nine potential homologues from other fungal organisms. Although the overall sequence identity between these proteins is only ∼22%, the amino acid comparison showed a number of conserved sequence motifs of yet unknown function (our unpublished data). Among these homologues is the 105-kDa S. cerevisiae Spc105 protein, which shares a number of sequence motifs with the C-terminal part of the 153-kDa Spc7 protein (our unpublished data; Wigge et al., 1998; Nekrasov et al., 2003). To determine whether members of this family have a similar function, we tested the ability of the S. cerevisiae Spc105 protein to suppress phenotypes of mal3 mutant strains. Spc105 is part of the S. cerevisiae kinetochore as shown by ChIP and immunofluorescence analysis of a Spc105 fusion protein (our unpublished data; Nekrasov et al., 2003). We identified the Spc105 protein as a component that copurified with the centromere associated, highly conserved Ndc80 complex. Spc24, a known Ndc80 complex component was protein A-tagged and the fusion protein isolated from cell extracts by using affinity chromatography with IgG-Sepharose. The proteins that copurified with protein A-tagged Spc24 were identified by peptide mass fingerprints (MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry). In addition to the previously identified components of the Ndc80 complex, namely, Ndc80, Nuf2, Spc24, and Spc25 (Janke et al., 2001; Wigge and Kilmartin, 2001), we also identified Spc105 in this analysis (Figure 8A). We thus conclude that Spc105 is associated closely with the evolutionarily conserved Ndc80 complex. Next, we protein A-tagged Spc105 and identified the Ydr532c protein as a copurification partner (our unpublished data). The 44-kDa Ydr532c protein has been identified as a component of the SPB and very recently as a new component of the budding yeast kinetochore (Giaever et al., 2002; Huh et al., 2003; Nekrasov et al., 2003).

Figure 8.

S. cerevisiae Spc105, a component of the conserved Ndc80 kinetochore complex, rescues mal3 mutants. (A) Spc105 copurifies with the Ndc80 complex. Protein A-tagged Spc24 was purified from 4000 OD of cells by affinity chromatography with IgG-agarose, and the complete preparation was subjected to SDS-PAGE. Copurifying proteins 578were identified from Coomassie-stained bands by peptide mass finger printing (MALDI-TOF). Bands that are not labeled represent contaminants. (B) TBZ hypersensitivity of the S. pombe mal3-1 and Δmal3 strains and the S. cerevisiae Δbim1 strain is partially rescued by overexpression of SPC105. Panels show serial dilution patch tests (104 to 101 cells) of mal3-1, Δ mal3, and Δ bim1 transformants grown under selective conditions in the absence (–TBZ) or presence (+TBZ) of TBZ. Plates were incubated for 5 d at 24°C (mal3 strains) or 3 d at 30°C (Δbim1 strain). Vector control indicates plasmid without insert. (C) Serial dilution patch tests of Δbim1, tetO-CYC1/SPC105 single and double mutant strains on YPD with doxycyline with or without 50 μg/ml TBZ. Strains were grown at 30°C for 48 h.

To test whether Spc105 and Spc7 might have a similar function, we tested whether Spc105 could suppress the TBZ hypersensitivity of mal3 mutant strains. As shown in Figure 8B, SPC105 expressed from the regulatable S. pombe nmt1+ promoter was able to partially suppress the TBZ hypersensitivity of the S. pombe mal3-1 and Δmal3 strains. In addition, SPC105 expressed from the MET25 promoter on a plasmid was able to partially suppress the TBZ hypersensitivity of the S. cerevisiae Δbim1 strain (Figure 8B). Bim1 is the S. cerevisiae member of the EB1 family (Schwartz et al., 1997).

We next tested whether SPC105 and BIM1 interacted genetically. For this purpose, we used a strain where SPC105 was expressed from an ectopic promoter. The endogenous SPC105 promoter was replaced by the doxycycline regulatable tetO-CYC1 promoter in a strain with an integrated tetR-VP16(tTA) activator allowing regulated expression from the tetO-CYC1 promoter (Gari et al., 1997). Cells carrying this construct are viable but show a strong increase in the loss of a GFP-marked chromosome fragment and increased sensitivity to TBZ (our unpublished data; Figure 8C). The TBZ-hypersensitivity of the tetO-CYC/SPC105 strain was increased by the absence of bim1+ as a tetO-CYC/SPC105 Δ bim1 double mutant strain was more sensitive to TBZ than the single mutant strains (Figure 8C). Furthermore, the double mutant strain showed reduced growth at 36 and at 18°C compared with the single mutant strains (our unpublished data), thus implying that BIM1 and SPC105 show genetic interaction.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the role of S. pombe EB1 family member in mitosis by screening for suppressors that were able to rescue the mal3 mutant phenotypes, namely, TBZ hypersensitivity and increased chromosome loss. The most frequently isolated suppressor, spc7+, codes for an essential component of the kinetochore, thus demonstrating that Mal3 plays a role at the spindle–kinetochore interface. Members of the EB1 family have been shown to be associated with kinetochores (Juwana et al., 1999; Fodde et al., 2001; Kaplan et al., 2001; Rehberg and Graf, 2002; Tirnauer et al., 2002a), but the interaction partner at the kinetochore has remained unclear. The finding that the S. cerevisiae Spc105 protein seems to be a homolog of Spc7 implies that this interaction at the spindle–kinetochore interface has been conserved.

The Spc7 protein is an essential component of the S. pombe kinetochore that associates specifically with the central centromere region, implying that this region is required for kinetochore–microtubule association. Although phenotypic analysis of various S. pombe kinetochore mutants had suggested that this region is needed for kinetochore–microtubule association (Saitoh et al., 1997; Goshima et al., 1999; Jin et al., 2002; Pidoux et al., 2003), Spc7 is the first central centromere region protein for which a direct involvement at the kinetochore–microtubule interface has been demonstrated. In support of this finding, Dis1, a member of the TOG/XMAP215 family of microtubule-associated proteins, is associated with this region in mitosis, although the other XMAP215 homologue in S. pombe, Alp14/Mtc1, shows a somewhat different localization (Garcia et al., 2001; Nakaseko et al., 2001). Association of Mal3 with a specific centromere region needs yet to be demonstrated. Our attempts to map the centromere region with which Mal3 interacts by using ChIP followed by multiplex PCR were not successful (our unpublished data). However, given the finding that Spc7 and Mal3 could be coimmunoprecipitated, it is feasible that Mal3 is associated with the central centromere region.

Enrichment of the central region DNA sequences in Spc7 ChIPs was repeatedly twofold lower than that of another central region-associated protein, namely, Mal2. This might imply that in an assembled kinetochore Spc7 is physically further away from the centromeric DNA than Mal2. Ultrastructural analysis has shown that S. pombe centromeres are multilayered structures (Kniola et al., 2001). In particular, the Ndc80 complex, with which Spc7 is probably associated, was shown to be part of an “anchor structure” close to the SPB and distinct from the localization of the S. pombe CENP-A homolog Cnp1 (Kniola et al., 2001). Consistent with this observation, we found that in the majority of interphase cells the Spc7 signal was further away from the nuclear periphery than the Mal2 signal.

Our experimental data indicate that the role of the Spc7 protein at the kinetochore is that of linking the kinetochore to microtubule-plus ends and possibly influencing the dynamics of kinetochore microtubules. First, spc7+ rescued the increased chromosome loss phenotype of a mal3 mutant strain and can be coimmunoprecipitated with the microtubule plus-end protein Mal3. Second, overexpression of an Spc7 variant (Spc7-C) led to a dominant negative phenotype and kinetochores that were not associated with the mitotic spindle, implying that Spc7 affects kinetochore–microtubule interactions. Third, preliminary evidence indicates that Spc7 might have a role in microtubule dynamics. Extra spc7+ is able to rescue the TBZ-hypersensitivity of specific strains such as mal3 mutants and the Ran mutant spi1-25. Overexpression of full-length Spc7 increases the resistance of cells to the microtubule destabilizing drug TBZ, whereas overproduction of Spc7-C has the opposite effect. Fourth, the S. cerevisiae kinetochore protein Spc105 can partially suppress the phenotypes of S. pombe mal3 mutant strains, suggesting that Spc7 and Spc105 might be functionally homologous. We identified Spc105, as a copurification partner of the Ndc80 complex. The highly conserved Ndc80/HEC1 kinetochore complex is required for the establishment and maintenance of kinetochore–microtubule interactions and plays a role in spindle checkpoint activity (He et al., 2001; Janke et al., 2001; Wigge and Kilmartin, 2001; DeLuca et al., 2002; Bharadwaj et al., 2004; McCleland et al., 2004). Spc105 also has been found recently in affinity purifications of S. cerevisiae kinetochore proteins that define the Mtw1p complex (De Wulf et al., 2003; Nekrasov et al., 2003). Furthermore, Spc105 affinity purification has been described to contain components of the Ndc80 complex (Nekrasov et al., 2003). Our finding that Spc105 copurifies with the Ndc80 complex component Spc24 confirms that Spc105 is in proximity to the Ndc80 complex. The fact that Spc105 was not detected in Ndc80 preparations (Nekrasov et al., 2003) might reflect the fact that Spc105 is more closely associated with Spc24 than Ndc80. Alternatively, this might be due to differences in the experimental conditions.

Homologues of the Ndc80 complex also exist in S. pombe and have been shown to be part of the kinetochore (Kniola et al., 2001; Wigge and Kilmartin, 2001). It is at present unclear whether Spc7 is closely associated with or part of this complex. However, Spc7 can be coimmunoprecipitated by the S. pombe Spc24 protein and vice versa (Kerres and Fleig, unpublished data). Furthermore, Spc24, like Spc7, is associated with the central centromere region (Kerres and Fleig, unpublished data). It is thus feasible to propose that Spc7 is associated with the S. pombe Ndc80 complex.

The identification of Spc7/Spc105, as a suppressor of the mal3 mutant phenotype implies that the Ndc80 complex or proteins in proximity to this complex might possibly play a more direct role in association with microtubule plus-ends than previously envisaged (reviewed in Cheeseman et al., 2002). Interestingly, components of the Ndc80 complex as well as Spc105 but not inner kinetochore proteins such as Ndc10 were identified in enriched SPB preparations (Wigge et al., 1998).

Our experimental data suggest that one of the factors required for kinetochore–microtubule association is an interaction between the kinetochore protein Spc7 and the microtubule plus-end–associated protein Mal3. The Ran GTPase seems to play a role in this specific association as extra Spc7 can rescue a spi1 mutation, which results in a decrease in the amount of active Ran in cells that are competent for nucleocytoplasmic transport (Fleig et al., 2000; Salus et al., 2002). Recently, Ran has been implicated in kinetochore function as the GTPase activating proteins Ran GAP1 and RanBP2 are associated with metaphase kinetochores and Caenorhabditis elegans Ran was localized to kinetochores, where it seemed to play a role in the association of kinetochore microtubules to chromosomes (Bamba et al., 2002; Joseph et al., 2002). Furthermore, in Xenopus egg extracts the spindle checkpoint and the kinetochore association of spindle checkpoint proteins is directly regulated by Ran-GTP levels (Arnaoutov and Dasso, 2003).

What is the function of Mal3 at the kinetochore–microtubule interface? Our coimmunoprecipitation analysis suggests that the interaction between Spc7 and Mal3 is not a stable one, thus making it unlikely that the main role of Mal3 is that of continuous microtubule–kinetochore attachment. In support of this is the finding that the kinetochore localization of EB1 was restricted to a subset of early mitotic kinetochores that were associated with polymerizing microtubule plus-ends (Tirnauer et al., 2002a). It is thus more feasible that Mal3 has a role in regulating microtubule dynamics at the kinetochore. The effect of EB1 family members on microtubule dynamics has been amply documented (Beinhauer et al., 1997; Tirnauer et al., 1999; Nakamura et al., 2001; Busch and Brunner, 2004). Absence of EB1 family members leads to reduced microtubule length, whereas overexpression of EB1 bundles microtubules (Bu and Su, 2001; Nakamura et al., 2001; Rogers et al., 2002; Tirnauer et al., 2002b; Ligon et al., 2003). Furthermore, Mal3 affects microtubule dynamics by initiating microtubule growth and inhibiting catastrophe events in interphase microtubule arrays (Beinhauer et al., 1997; Busch and Brunner, 2004). Because overexpression of Spc7 makes wild-type cells more resistant to microtubule-destabilizing drugs, we would like to suggest that Mal3 and Spc7 are part of the complex protein machinery that modulates the dynamic behavior of microtubules at the kinetochore. In this context, it is interesting to note that the ability of EB1 to promote microtubule polymerization was dependent on the presence of the C-terminal part of APC, suggesting that EB1 function is modulated by other proteins (Nakamura et al., 2001). Whether Spc7 has a similar effect on the function of Mal3 or whether it acts in this process but independently of Mal3 remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shelley Sazer for the careful reading of the manuscript and Heidi Browning, Tony Carr, Iain Hagan, Mitsuhiro Yanagida, Takashi Toda, Kathy Gould, John Kilmartin, Ulrich Güldener, and Keith Gull for reagents. Special thanks to Alison Pidoux for teaching us how to do S. pombe ChIP. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E04–06–0443. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04–06–0443.

References

- Akhmanova, A., et al. (2001). Clasps are CLIP-115 and -170 associating proteins involved in the regional regulation of microtubule dynamics in motile fibroblasts. Cell 104, 923–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutov, A., and Dasso, M. (2003). The Ran GTPase regulates kinetochore function. Dev. Cell 5, 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamba, C., Bobinnec, Y., Fukuda, M., and Nishida, E. (2002). The GTPase Ran regulates chromosome positioning and nuclear envelope assembly in vivo. Curr. Biol. 12, 503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbet, N., Muriel, W.J., and Carr, A.M. (1992). Versatile shuttle vectors and genomic libraries for use with Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Gene 114, 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beinhauer, J.D., Hagan, I.M., Hegemann, J.H., and Fleig, U. (1997). Mal3, the fission yeast homologue of the human APC-interacting protein EB-1 is required for microtubule integrity and the maintenance of cell form. J. Cell Biol. 139, 717–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, P., and Allshire, R. (2002). Centromeres become unstuck without heterochromatin. Trends Cell Biol. 12, 419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj, R., Qi, W., and Yu, H. (2004). Identification of two novel components of the human Ndc80 kinetochore complex. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 13076–13085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, A.J., Morphew, M., Bartlett, R., and Hagan, I.M. (1998). The fission yeast SPB component Cut12 links bipolar spindle formation to mitotic control. Genes Dev. 12, 927–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu, W., and Su, L.K. (2001). Regulation of microtubule assembly by human EB1 family proteins. Oncogene 20, 3185–3192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch, K.E., and Brunner, D. (2004). The microtubule plus end-tracking proteins mal3p and tip1p cooperate for cell-end targeting of interphase microtubules. Curr. Biol. 14, 548–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman, I.M., Drubin, D.G., and Barnes, G. (2002). Simple centromere, complex kinetochore: linking spindle microtubules and centromeric DNA in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 157, 199–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, L. (1998). Centromeres: proteins, protein complexes, and repeated domains at centromeres of simple eukaryotes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 8, 212–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, D.W., Mao, Y., and Sullivan, K.F. (2003). Centromeres and kinetochores: from epigenetics to mitotic checkpoint signaling. Cell 112, 407–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wulf, P., McAinsh, A.D., and Sorger, P.K. (2003). Hierarchical assembly of the budding yeast kinetochore from multiple subcomplexes. Genes Dev. 17, 2902–2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca, J.G., Moree, B., Hickey, J.M., Kilmartin, J.V., and Salmon, E.D. (2002). hNuf2 inhibition blocks stable kinetochore-microtubule attachment and induces mitotic cell death in HeLa cells. J. Cell Biol. 159, 549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin, D., Wacker, U.I., Moreau, A., Schroer, T.A., Rickard, J.E., and De Mey, J.R. (1998). Evidence for a role of CLIP-170 in the establishment of metaphase chromosome alignment. J. Cell Biol. 141, 849–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekwall, K., Javerzat, J.P., Lorentz, A., Schmidt, H., Cranston, G., and Allshire, R. (1995). The chromodomain protein Swi 6, a key component at fission yeast centromeres. Science 269, 1429–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleig, U., Salus, S.S., Karig, I., and Sazer, S. (2000). The fission yeast Ran GTPase is required for microtubule integrity. J. Cell Biol. 151, 1101–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleig, U., Sen-Gupta, M., and Hegemann, J.H. (1996). Fission yeast mal2+ is required for chromosome segregation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 6169–6177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodde, R., et al. (2001). Mutations in the APC tumour suppressor gene cause chromosomal instability. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki, H., Hagan, I., Uzawa, S., and Yanagida, M. (1993). Cell cycle-dependent specific positioning and clustering of centromeres and telomeres in fission yeast. J. Cell Biol. 121, 961–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.A., Vardy, L., Koonrugsa, N., and Toda, T. (2001). Fission yeast ch-TOG/XMAP215 homologue Alp14 connects mitotic spindles with the kinetochore and is a component of the Mad2-dependent spindle checkpoint. EMBO J. 20, 3389–3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gari, E., Piedrafita, L., Aldea, M., and Herrero, E. (1997). A set of vectors with a tetracycline-regulatable promoter system for modulated gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 13, 837–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever, G., et al. (2002). Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 418, 387–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshima, G., Saitoh, S., and Yanagida, M. (1999). Proper metaphase spindle length is determined by centromere proteins Mis12 and Mis6 required for faithful chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 13, 1664–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen, G.G., and Bretscher, A. (2003). Cell biology. Microtubule asymmetry. Science 300, 2040–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, I.M., and Hyams, J.S. (1988). The use of cell division cycle mutants to investigate the control of microtubule distribution in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Cell Sci. 89, 343–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X., Jones, M.H., Winey, M., and Sazer, S. (1998). Mph1, a member of the Mps1-like family of dual specificity protein kinases, is required for the spindle checkpoint in S. pombe. J. Cell Sci. 111, 1635–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X., Rines, D.R., Espelin, C.W., and Sorger, P.K. (2001). Molecular analysis of kinetochore-microtubule attachment in budding yeast. Cell 106, 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh, W.K., Falvo, J.V., Gerke, L.C., Carroll, A.S., Howson, R.W., Weissman, J.S., and O'Shea, E.K. (2003). Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature 425, 686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke, C., Ortiz, J., Lechner, J., Shevchenko, A., Magiera, M.M., Schramm, C., and Schiebel, E. (2001). The budding yeast proteins Spc24p and Spc25p interact with Ndc80p and Nuf2p at the kinetochore and are important for kinetochore clustering and checkpoint control. EMBO J. 20, 777–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Q.W., Pidoux, A.L., Decker, C., Allshire, R.C., and Fleig, U. (2002). The mal2p protein is an essential component of the fission yeast centromere. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7168–7183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, J., Tan, S.H., Karpova, T.S., McNally, J.G., and Dasso, M. (2002). SUMO-1 targets RanGAP1 to kinetochores and mitotic spindles. J. Cell Biol. 156, 595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juwana, J.P., Henderikx, P., Mischo, A., Wadle, A., Fadle, N., Gerlach, K., Arends, J.W., Hoogenboom, H., Freudschuh, M., and Renner, C. (1999). EB/RP gene family encodes tubulin binding proteins. Int. J. Cancer 81, 275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, C., Michaelis, S., and Mitchell, A. (1994). Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Kaplan, K.B., Burds, A.A., Swedlow, J.R., Bekir, S.S., Sorger, P.K., and Nathke, I.S. (2001). A role for the adenomatous polyposis coli protein in chromosome segregation. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 429–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner, M., and Mitchison, T. (1986). Beyond self-assembly: from microtubules to morphogenesis. Cell 45, 329–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kniola, B., O'Toole, E., McIntosh, J.R., Mellone, B., Allshire, R., Mengarelli, S., Hultenby, K., and Ekwall, K. (2001). The domain structure of centromeres is conserved from fission yeast to humans. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 2767–2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon, L.A., Shelly, S.S., Tokito, M., and Holzbaur, E.L. (2003). The microtubule plus-end proteins EB1 and dynactin have differential effects on microtubule polymerization. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 1405–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H., de Carvalho, P., Kho, D., Tai, C.Y., Pierre, P., Fink, G.R., and Pellman, D. (2001). Polyploids require Bik1 for kinetochore-microtubule attachment. J. Cell Biol. 155, 1173–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiato, H., Fairley, E.A., Rieder, C.L., Swedlow, J.R., Sunkel, C.E., and Earnshaw, W.C. (2003). Human CLASP1 is an outer kinetochore component that regulates spindle microtubule dynamics. Cell 113, 891–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleland, M.L., Kallio, M.J., Barrett-Wilt, G.A., Kestner, C.A., Shabanowitz, J., Hunt, D.F., Gorbsky, G.J., and Stukenberg, P.T. (2004). The vertebrate Ndc80 complex contains Spc24 and Spc25 homologs, which are required to establish and maintain kinetochore-microtubule attachment. Curr. Biol. 14, 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, J.R., Grishchuk, E.L., and West, R.R. (2002). Chromosome-microtubule interactions during mitosis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 18, 193–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimori-Kiyosue, Y., and Tsukita, S. (2003). “Search-and-capture” of microtubules through plus-end-binding proteins (+TIPs). J. Biochem. 134, 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, M.B., Duran, A., and Ribas, J.C. (2000). A family of multifunctional thiamine-repressible expression vectors for fission yeast. Yeast 16, 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, S., Klar, A., and Nurse, P. (1991). Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 194, 795–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabeshima, K., Kurooka, H., Takeuchi, M., Kinoshita, K., Nakaseko, Y., and Yanagida, M. (1995). p93dis1, which is required for sister chromatid separation, is a novel microtubule and spindle pole body-associating protein phosphorylated at the Cdc2 target sites. Genes Dev. 9, 1572–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, M., Zhou, X.Z., and Lu, K.P. (2001). Critical role for the EB1 and APC interaction in the regulation of microtubule polymerization. Curr. Biol. 11, 1062–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaseko, Y., Goshima, G., Morishita, J., and Yanagida, M. (2001). M phase-specific kinetochore proteins in fission yeast. Microtubule-associating Dis1 and Mtc1 display rapid separation and segregation during anaphase. Curr. Biol. 11, 537–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekrasov, V.S., Smith, M.A., Peak-Chew, S., and Kilmartin, J.V. (2003). Interactions between centromere complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 4931–4946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa, O., Matsumoto, T., and Yanagida, M. (1986). Construction of a minichromosome by deletion and its mitotic and meiotic behaviour in fission yeast. Mol. Gen. Genet. 203, 397–405. [Google Scholar]

- Ohkura, H., Adachi, Y., Kinoshita, N., Niwa, O., Toda, T., and Yanagida, M. (1988). Cold-sensitive and caffeine-supersensitive mutants of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe dis genes implicated in sister chromatid separation during mitosis. EMBO J. 7, 1465–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge, J.F., Borgstrom, B., and Allshire, R.C. (2000). Distinct protein interaction domains and protein spreading in a complex centromere. Genes Dev. 14, 783–791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidoux, A.L., and Allshire, R.C. (2000). Centromeres: getting a grip of chromosomes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12, 308–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidoux, A.L., Richardson, W., and Allshire, R.C. (2003). Sim 4, a novel fission yeast kinetochore protein required for centromeric silencing and chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol. 161, 295–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehberg, M., and Graf, R. (2002). Dictyostelium EB1 is a genuine centrosomal component required for proper spindle formation. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 2301–2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S.L., Rogers, G.C., Sharp, D.J., and Vale, R.D. (2002). Drosophila EB1 is important for proper assembly, dynamics, and positioning of the mitotic spindle. J. Cell Biol. 158, 873–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh, S., Takahashi, K., and Yanagida, M. (1997). Mis6, a fission yeast inner centromere protein, acts during G1/S and forms specialized chromatin required for equal segregation. Cell 90, 131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salus, S.S., Demeter, J., and Sazer, S. (2002). The Ran GTPase system in fission yeast affects microtubules and cytokinesis in cells that are competent for nucleocytoplasmic protein transport. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 8491–8505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuyler, S.C., and Pellman, D. (2001). Microtubule “plus-end-tracking proteins”: the end is just the beginning. Cell 105, 421–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, K., Richards, K., and Botstein, D. (1997). BIM1 Encodes a Microtubule-binding Protein in Yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 2677–2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko, A., Wilm, M., Vorm, O., and Mann, M. (1996). Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68, 850–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.K., Burrell, M., Hill, D.E., Gyuris, J., Brent, R., Wiltshire, R., Trent, J., Vogelstein, B., and Kinzler, K.W. (1995). APC binds to the novel protein EB1. Cancer Res. 55, 2972–2977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirnauer, J.S., and Bierer, B.E. (2000). EB1 Proteins Regulate Microtubule Dynamics, Cell Polarity, and Chromosome Stability. J. Cell Biol. 149, 761–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirnauer, J.S., Canman, J.C., Salmon, E.D., and Mitchison, T.J. (2002a). EB1 targets to kinetochores with attached, polymerizing microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 4308–4316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirnauer, J.S., Grego, S., Salmon, E.D., and Mitchison, T.J. (2002b). EB1-microtubule interactions in Xenopus egg extracts: role of EB1 in microtubule stabilization and mechanisms of targeting to microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 3614–3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirnauer, J.S., O'Toole, E., Berrueta, L., Bierer, B.E., and Pellman, D. (1999). Yeast Bim1p promotes the G1-specific dynamics of microtubules. J. Cell Biol. 145, 993–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umesono, K., Toda, T., Hayashi, S., and Yanagida, M. (1983). Cell division cycle genes nda2 and nda3 of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe control microtubular organization and sensitivity to anti-mitotic benzimidazole compounds. J. Mol. Biol. 168, 271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigge, P.A., Jensen, O.N., Holmes, S., Soues, S., Mann, M., and Kilmartin, J.V. (1998). Analysis of the Saccharomyces spindle pole by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry. J. Cell Biol. 141, 967–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigge, P.A., and Kilmartin, J.V. (2001). The Ndc80p complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains conserved centromere component and has a function in chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol. 152, 349–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods, A., Sherwin, T., Sasse, R., MacRae, T.H., Baines, A.J., and Gull, K. (1989). Definition of individual components within the cytoskeleton of Trypanosoma brucei by a library of monoclonal antibodies. J. Cell Sci. 93, 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, H., Kumada, K., and Yanagida, M. (1997). Distinct subunit functions and cell cycle regulated phosphorylation of 20S APC/cyclosome required for anaphase in fission yeast. J. Cell Sci. 110, 1793–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]