Abstract

Background: In the United States, 17% of children are currently obese. Increasing feelings of fullness may prevent excessive energy intake, lead to better diet quality, and promote long-term maintenance of healthy weight.

Objective: The purpose of this study was to develop a fullness-rating tool (aim 1) and to determine whether a high-protein (HP), high-fiber (HF), and combined HP and HF (HPHF) breakfast increases preschoolers’ feelings of fullness before (pre) and after (post) breakfast and pre-lunch, as well as their diet quality, as measured by using a composite diet quality assessment tool, the Revised Children’s Diet Quality Index (aim 2).

Methods: Children aged 4 and 5 y (n = 41; 22 girls and 19 boys) from local Head Start centers participated in this randomized intervention trial. Sixteen percent of boys and 32% of girls were overweight or obese. After the baseline week, children rotated through four 1-wk periods of consuming ad libitum HP (19–20 g protein), HF (10–11 g fiber), HPHF (19–21 g protein, 10–12 g fiber), or usual (control) breakfasts. Food intake at breakfast was estimated daily, and for breakfast, lunch, and snack on day 3 of each study week Student’s t tests and ANOVA were used to determine statistical differences.

Results: Children’s post-breakfast and pre-lunch fullness ratings were ≥1 point higher than those of pre-breakfast (aim 1). Although children consumed, on average, 65 kcal less energy during the intervention breakfasts (P < 0.007) than during the control breakfast, fullness ratings did not differ (P = 0.76). Relative to the control breakfast, improved diet quality (12%) was calculated for the HP and HF breakfasts (P < 0.027) but not for the HPHF breakfast (aim 2).

Conclusions: Post-breakfast fullness ratings were not affected by the intervention breakfasts relative to the control breakfast. HP and HF breakfasts resulted in higher diet quality. Serving HP or HF breakfasts may be valuable in improving diet quality without lowering feelings of satiation or satiety. This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT02122224.

Keywords: fullness, diet quality, RCDQI, preschool, protein, fiber, breakfast, hunger, spontaneous compensation

Introduction

The rate of obesity in American children has increased over the past few decades, with 17% of children now classified as obese (1). In preschool children, the prevalence of obesity increased from 7% in 1988 to 12% in 2013 (2, 3). Obesity is associated with an increased risk of several chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (4, 5), risk factors that are apparent as early as preschool age (6). Early nutrition intervention is essential because weight status and eating behaviors track from early childhood through later life (7–10). Eating behaviors, such as food responsiveness [“eating in response to environmental cues” (11)] and satiety responsiveness [“ability of a child to reduce food intake after eating to regulate its energy intake” (11)], are correlated in children aged 4–10 y (12).

Modifying energy intake at an early age is a viable approach to decrease the prevalence of obesity. One possible way to decrease excess energy intake may be to increase feelings of fullness. Fullness reflects satiation and satiety. Satiation refers to feelings that will increase during an eating occasion and eventually prompt the cessation of that eating occasion (feeling full at the end of the snack or meal), whereas satiety refers to the feelings initiated at the end of an eating occasion and continuing through the intermeal period (13). Results from parent reports (14, 15) suggest that children who are overweight or obese have decreased satiety responses compared with children of average weight. Consistent with these findings are data that indicate that satiety responsiveness tracks from preschool to preadolescence (12). Lower satiety responsiveness may lead to more frequent eating and therefore increased energy intake and body weight.

The consumption of foods and beverages that result in greater feelings of satiation and satiety (16, 17) can help reduce excessive energy intake. Food components known for their association with increased feelings of fullness are protein and fiber. Protein is generally considered the most satiating macronutrient, and fiber activates stretch receptors and can slow the dispersion of digestive enzymes and nutrient absorption (16, 18). Many studies have evaluated these effects in adults, but data on preschool children are limited, due, in part, to the complexity of conducting research in that age group.

In older children and adults, fullness ratings are typically obtained through visual analog scales (19–22). Only 2 tools have been developed for young children (23–25): one targeted primary school children (ages 5–9 y old) (23) and the other was developed in 20 children aged 4–6 y who were asked to rate feelings of hunger and fullness in response to imaginary eating occasions by using a 5-point scale (24). The latter task may not be developmentally appropriate for preschoolers because serration and ordering skills usually develop between the ages of 4 and 5 y. However, preschool children are able to compare amounts, and a 2-level comparison approach is developmentally appropriate (26). We developed a fullness-rating tool by using 2 silhouettes (Supplemental Figure 1) that preschool children are able to distinguish (26). To our knowledge, no research is available to evaluate how fullness ratings of imaginary events would compare with an actual eating occasion.

Preschool children from low-income families are more likely to have poor diet quality than are children of higher socioeconomic status (27), and the prevalence of obesity in low-income children is almost twice the national average for their age group (28); thus, low-income preschool children are a high-priority population for nutrition interventions. Preschools offer excellent opportunities for nutrition interventions, because at least 60% of American children aged <6 y spend time in care outside the household (29).

The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of consuming high-protein (HP)8, high-fiber (HF), and combined HP and HF (HPHF) breakfasts on low-income preschoolers’ feelings of fullness and their diet quality, which was measured by using a composite diet quality score.

Methods

We conducted 2 independent studies to 1) develop a fullness-rating tool that is age-appropriate for preschool children and 2) to evaluate the effect of serving children 3 types of intervention breakfasts—HF (10 g fiber/d), HP (20 g protein/d), and HPHF (20 g protein and 10 g fiber/d, respectively)—compared with usual breakfasts (control) at local preschools serving low-income populations (Head Start centers). The nutrient content of the study breakfasts is shown in Table 1. The intervention breakfasts were matched for energy content to the control preschool breakfasts (300 ± 25 kcal). The HPHF breakfasts contained ≥1.5 times the average protein or fiber served in the control breakfast, which represented the highest achievable amounts with the use of child-friendly foods and adhering to Child and Adult Care Food Guidelines (30). All of the study foods were tested for acceptability at a nonparticipating childcare center and recipes were modified until ≥80% of children rated the study foods as “acceptable.”

TABLE 1.

Nutrient content of intervention breakfasts by breakfast type1

| Breakfast | Energy, kcal | Protein, g | Fat, g | Carbohydrate, g | Fiber, g |

| HP | 299 (282–319) | 19.8 (19.2–20.3) | 6.8 (3.5–11.1) | 42.3 (25.9–55) | 3.6 (1.8–4.7) |

| HF | 283 (277–291) | 9.9 (8.8–11.2) | 3.8 (3.2–5.5) | 56.2 (55.7–56.8) | 10.5 (9.8–11.0) |

| HPHF | 304 (299–312) | 20.5 (19.0–21.7) | 6.2 (3.6–6.4) | 49.6 (39.5–57.9) | 11.0 (10.0–12.1) |

| Control | 311 (180–424) | 12.4 (7.6–21.9) | 7.9 (2.1–14.4) | 49.9 (33.1–70.2) | 3.1 (1.4–6.4) |

Values are means (ranges). HF, high-fiber diet; HP, high-protein diet; HPHF, high-protein and high-fiber diet.

Teachers and parents of 4- and 5-y-old children were approached through the centers. Recruitment packets included a questionnaire to ascertain information on selected demographic characteristics and children’s food allergies. Children with known food allergies were excluded from participation.

All data collection procedures were standardized through extensive training with research staff and followed a written protocol to ensure age-appropriate and consistent communications with the children. The protocols for these studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Purdue University, and the feeding trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT02122224. Parents provided written consent, and all participating children were asked for verbal assent before each study procedure; children’s refusal to participate was honored.

Food intake while at preschool was recorded by research staff by using a validated method (Diet Observation for Child Care) to assess food consumption in children by direct observation (31). This method was preferable to alternative methods, such as measuring plate waste, to minimize disruption to classroom procedures. The training manual was followed, and research staff practiced visually estimating portion sizes of >20 commonly served foods and beverages at the participating preschools. On the basis of the validated training methods, practice continued until all study staff accurately estimated portion sizes within 2 tablespoons of food. To assess what children were eating and drinking outside of preschool hours, parents were asked to keep a record of what their child ate and drank on Wednesdays of each study week before and after preschool. Parents were instructed on how to complete food records for their child with the booklet from Nutrient Data System for Research as an aid in estimating portion sizes.

All dietary data were entered in Nutrient Data System for Research version 2012, developed by the Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota, to calculate gram, energy, food group, and nutrient intakes. Diet quality was calculated with the Revised Children’s Diet Quality Index (RC-DQI) (32) to rate actual intake compared with age- and sex-specific population intake guidelines for important foods and nutrients. The RC-DQI was chosen over the Healthy Eating Index because it includes components specific to child growth and health concerns and does not dichotomize the population into those with poor and good diets, as the Healthy Eating Index has been shown to do (33). The RC-DQI scoring theme was originally designed based on repeated 24-h dietary intake data to assess total diet. The study was designed to assess total daily intake; however, because only a very few parents of the subjects enrolled in this study returned the 24-h food intake forms, diet quality estimates were assessed on the basis of the directly observed meals at the centers. Intakes during breakfast, lunch, and snack were observed on day 3 of each study week. According to the literature, an estimated 66% of preschoolers’ total food intake occurs during those eating occasions (34). The RC-DQI scoring was adjusted to reflect a target goal of two-thirds of the intake recommendation for the entire day.

Aim 1: tool development to assess feelings of fullness

Children aged 4–5 y (n = 65) were recruited from local preschools for a week-long pilot study to test a child-appropriate adaptation of a visual analog scale to assess feelings of fullness before and after eating a meal (lunch). Study procedures were conducted in the classroom and followed the usual schedule of activities: snack at 0900, lunch between 1130 and 1200, naptime, and snack at 1430. On the first day of the study, all children in the classroom listened to a short (∼5 min) story about the differences between having an “empty tummy” compared with having a “full tummy.” The story was read in English and Spanish, when appropriate, and introduced the labeling of the feelings associated with an “empty versus full tummy.” The story was followed by application exercises as visual examples of fictitious characters who had eaten different amounts of food were shown, and the children were asked to describe if the character’s “tummy” was feeling empty or full and the estimated magnitude of the feeling (a little or very). Children responded verbally or pointed to the silhouettes of “empty” and “full.”

Within 5 min of the beginning and the end of lunch, children were shown the pictures of the silhouettes and research staff first asked “How does your tummy feel right now? Does it feel empty or full?” as the staff member pointed to each silhouette. After the child responded, he or she was then asked, “Does your tummy feel a little empty/full, or very empty/full?” Although the questions were read in order, the prompting of the reply “empty or full” and “a little or very” was used at random, often triggered by the participant pointing to the response before the sentence with the question had been completed.

Aim 2: feeding intervention study

This crossover, randomized, controlled intervention trial was conducted in 2 preschools (n = 41) that did not participate in the study for aim 1. A sample size of 18 subjects was needed for 95% power to detect a 1-point change in the fullness score [1.1 SD (35)] with a 2-sided error of α = 0.05.

Teachers of 6 classrooms of 4- and 5-y-old children were approached and agreed to participate in the study. Packets were sent home with parents, and if the parents chose to have their child participate, signed packets were returned to the teachers. All data collection was conducted in the classrooms with teachers and nonparticipating children present on Monday through Thursday (centers were closed on Friday) over the course of 9 wk. The study schedule and weekly study procedures are shown in Supplemental Figure 2. Groups 1 and 2 were located in the same preschool and began the study 1 wk earlier than groups 3 and 4, allowing for study staff to conduct the study at a single preschool at a time (groups 1 and 2 were in washout phases when data collection commenced in groups 3 and 4). The first week of the study was used for baseline data collection and as an acclimation period for children to become accustomed to the presence of the research staff.

On Tuesday of the baseline week and weeks 3 and 7, study staff took children’s anthropometric measurements with the use of a standardized height rod attached to the stand of a calibrated body weight scale (Seneca) to record standing height and weight, without shoes, to the nearest 1 cm and 0.05 kg, respectively. Children were classified as underweight or normal weight or as overweight or obese at baseline as per CDC guidelines (36).

The order of the study conditions (one of the interventions or control) was selected at random for the entire group. On each study day, participating children reported their feelings of fullness on 3 occasions: before breakfast, after breakfast, and before lunch. The procedures described for aim 1 were followed to assess feelings of fullness with one modification: the training story was read on Monday and Tuesday of the baseline week as well as on the Monday of each study week thereafter.

Due to inclement weather and the associated center closings, some of the data collection days were not completed as originally scheduled and make-up days were scheduled. Study procedures were identical to those of the missed day.

Data analysis

All of the data were entered into Excel (Microsoft Corporation) spreadsheets with the use of double-entry procedures, and analyses were conducted by using Stata 11.2 (Stata Statistical Software, release 12; StataCorp LP). Significance was assumed at α < 0.05.

Aim 1.

Because day 1 of the study was an “acclimation day” for children and attendance in preschool was very low on day 5 (Friday; n = 17), only data for days 2–4 were analyzed. Children’s responses were coded on a Likert scale, with “1” being “very empty,” “2” being “a little empty,” “3” being “a little full,” and “4” being “very full.” If a child chose not to answer the second survey question (n = 2) to describe their tummy as “very” or “a little” empty or full, the response was dropped from analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample, and paired t tests were used to compare the participants’ pre- to post-meal ratings. Spearman correlations were used to compare actual energy and gram intakes with the fullness ratings.

Aim 2.

An intent-to-treat analysis was completed. Data from absent children were maintained in the data set, and other missing data (i.e., children chose not to eat) were not imputed.

The fullness score analysis was modified from that for aim 1 in that if a child had answered the first question (“hungry” or “full”) but did not further specify “a little” or “very” hungry or full, the response was recorded as a half-way point. For example, for a child who only reported feeling hungry, a 1.5-point score was assigned.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample (means, SDs, proportions) and to describe mean scores and food intake. Student’s t tests were used to directly compare differences in rating scores from pre- and post-breakfast as well as pre-lunch. Mean differences were also calculated and tested to assess differences in actual food intake by breakfast type. Bonferroni corrections were applied to account for multiple testing.

Repeated-measures ANOVAs were performed to determine if breakfast type was associated with differences in energy intake at lunch or with diet quality, controlling for week. Ordered logistic regression was performed to determine if breakfast type had any effect on fullness survey responses after breakfast or before lunch, controlling for study week, age, sex, race, and weight status.

Results

Aim 1.

Sixty-five children from 10 classrooms were recruited into the study. Characteristics of all participants included in the analysis (n = 59) are presented in Table 2. Six children did not provide any fullness data or were absent (n = 5) on ≥50% of data collection days. Fifteen children (7.7%) were absent at some point over the course of the study. Some children refused to answer the survey questions before breakfast (n = 8) and 1 child started eating before the questions could be asked, resulting in 4.5% missing pre-meal data points. Only 1 child refused to complete the fullness questionnaire after breakfast (<1% of post-meal responses).

TABLE 2.

Tool development pilot study (aim 1): participant demographic characteristics1

| Boys (n = 27) | Girls (n = 32) | Total (n = 59) | |

| Age | |||

| 4 y | 21 (77.8) | 23 (71.9) | 44 (74.6) |

| 5 y | 6 (22.2) | 9 (28.1) | 15 (25.4) |

| Race | |||

| American Indian | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) |

| Asian | 1 (3.7) | 2 (6.3) | 3 (5.1) |

| Black | 7 (25.9) | 2 (6.3) | 9 (15.3) |

| White | 7 (25.9) | 16 (50.0) | 23 (39.0) |

| Mixed | 4 (14.8) | 1 (3.1) | 5 (8.5) |

| Other | 5 (25.9) | 11 (34.4) | 18 (30.5) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 6 (22.2) | 12 (37.5) | 18 (30.5) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 21 (77.8) | 20 (62.5) | 41 (69.5) |

Values are n (%).

The primary outcome variable of this aim of the randomized controlled trial was the change in fullness ratings. The daily mean self-reported fullness rating was 2.0 (ranging from 1.7 to 2.4), which significantly (P < 0.05) increased after lunch (mean: 3.7; ranging from 3.6 to 3.9). Daily energy intakes at lunch fluctuated between 179 ± 122 and 194 ± 98 kcal (mean ± SD), and there was no significant difference in protein, carbohydrate, or fat intakes (Table 3). No significant associations were observed between the energy and grams consumed at lunch and the pre- and post-meal fullness ratings or between the energy and grams consumed and the change in self-reported fullness.

TABLE 3.

Tool development pilot study (aim 1): nutrient intakes of children according to day1

| Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | |

| Energy, kcal | 194 ± 98 | 184 ± 116 | 179 ± 122 |

| Protein, g | 7 ± 4 | 5 ± 5 | 7 ± 5 |

| Carbohydrate, g | 31 ± 15 | 28 ± 18 | 24 ± 19 |

| Fat, g | 6 ± 4 | 6 ± 6 | 7 ± 6 |

| Food + beverage, g | 190 ± 94 | 171 ± 111 | 195 ± 134 |

Values are means ± SDs; n = 59. Day 1 is not listed because it was used as an acclimation day and no data were collected.

Aim 2.

A total of 44 children were recruited for the nutrition intervention study. Two children were withdrawn from the preschool and 1 child withdrew from participation after week 1, leaving 41 children in the analysis. Of those, 5 children were absent for >2 d in a study week.

The majority of the sample was 4 y old at baseline, and there were similar numbers of boys and girls (Table 4). Most children (75%) were classified as being of normal weight. Although family income data were not collected, all of the children were from low-income families, as specified by Head Start Program participation guidelines (37).

TABLE 4.

Intervention study (aim 2): participant baseline demographic characteristics

| Boys (n = 19) | Girls (n = 22) | Total (n = 41) | |

| Age | |||

| 4 y | 13 (68.4) | 12 (54.6) | 25 (61.0) |

| 5 y | 6 (31.6) | 10 (45.5) | 16 (39.0) |

| Race | |||

| American Indian | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) |

| Asian | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.6) | 1 (2.4) |

| Black | 7 (36.8) | 2 (9.1) | 9 (22.0) |

| White | 3 (15.8) | 7 (31.8) | 10 (24.4) |

| Mixed | 2 (10.5) | 1 (4.6) | 3 (7.3) |

| Other | 6 (31.6) | 11 (50.0) | 17 (41.5) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 5 (26.3) | 11 (50.0) | 16 (39.0) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 14 (73.7) | 11 (50.0) | 25 (61.0) |

| Weight status | |||

| Underweight or normal weight | 16 (84.2) | 15 (68.2) | 31 (75.6) |

| Overweight or obese | 3 (15.8) | 7 (31.8) | 10 (24.4) |

Values are n (%).

The primary outcome variable of this aim of the randomized controlled trial was change in food intake. Weekly mean energy and nutrient intakes are shown in Table 5, which included children who did not consume food at breakfast (n = 5 total during the intervention weeks, and n = 8 during the control week). Baseline intake means were similar to those of the control week, with the exception of a higher mean fat intake during the baseline week than during the control week (P = 0.017). As expected, variations in energy and nutrient intakes were observed throughout the study. Children consumed significantly less total energy during the intervention breakfasts, which was consistent with the significantly lower intake of fat compared with the control breakfast. Mean protein intake did not differ from control, but mean protein density (g/100 kcal) was higher during the HP (P = 0.003) and HPHF (P = 0.003) weeks than during the control week. Mean fiber intake and fiber density (g/100 kcal) were higher during all 3 study breakfast weeks, and mean carbohydrate intake was lower compared with control in the HP and HPHF but not the HF breakfast week.

TABLE 5.

Nutrient and energy intake by intervention week1

| Energy, kcal | Protein, g | Carbohydrate, g | Fat, g | Fiber, g | Protein density, g/100 kcal | Fiber density, g/100 kcal | |

| Control | 201 ± 114 | 7 ± 4 | 32 ± 15 | 6 ± 6 | 2 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 |

| HP | 129 ± 145* | 9 ± 6 | 22 ± 12* | 3 ± 2* | 3 ± 2* | 6 ± 1* | 2 ± 1* |

| HPHF | 129 ± 62* | 8 ± 4 | 22 ± 22* | 3 ± 2* | 4 ± 2* | 6 ± 2* | 3 ± 1* |

| HF | 154 ± 74* | 5 ± 3 | 33 ± 15 | 2 ± 1* | 5 ± 3* | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1* |

Values are means ± SDs. *Different from control, P < 0.05. HF, high-fiber diet; HP, high-protein diet; HPHF, high-protein and high-fiber diet.

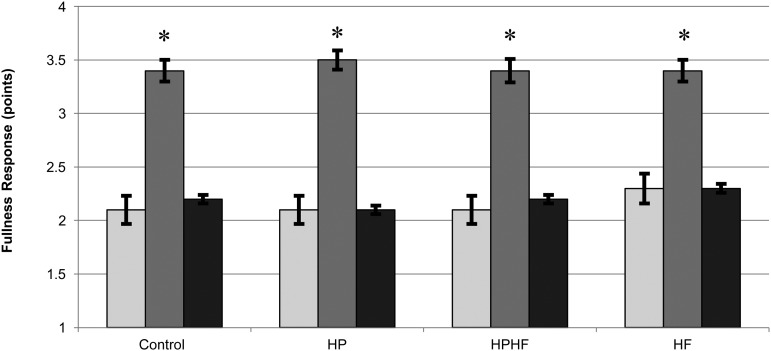

Mean fullness responses by intervention week are shown in Figure 1, which indicates that participants felt significantly “less full” before breakfast than after breakfast in each week (P < 0.05). Similarly, participants reported higher mean fullness after breakfast than pre-lunch (P < 0.05). Ordered logistic regression suggested that breakfast type had no effect on post-breakfast (P = 0.76) or pre-lunch (P = 0.68) fullness. Study week was the only significant predictor of fullness ratings (P = 0.008). Sex, age, race, and weight status were not predictors of the association. In addition, neither fiber density nor protein density were significant predictors of post-breakfast or pre-lunch fullness ratings.

FIGURE 1.

Fullness response by intervention week. Values are means ± SDs. *P < 0.05. Light-gray bars, pre-breakfast; medium-gray bars, post-breakfast; solid bars, pre-lunch. HF, high-fiber diet; HP, high-protein diet; HPHF, high-protein and high-fiber diet.

Children’s food intake and RC-DQI scores were intended to reflect children’s daily (24-h) intakes. However, because the number of diet records returned by parents was deemed too low for analysis (<15 records returned for each intervention week), mean daily energy and nutrient intakes as well as RC-DQI scores were calculated on the basis of the foods and beverages consumed at preschool. The RC-DQI scoring scheme was adapted to reflect that only ∼66% of children’s daily diets were captured. Thus, the scoring scheme was modified to allow full points when children met two-thirds of the intake goals.

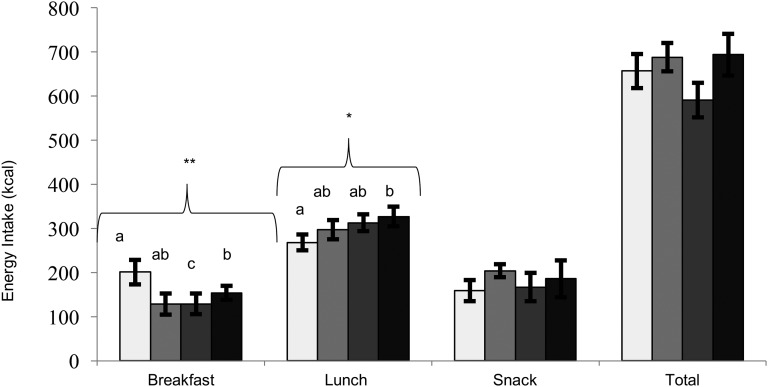

Mean energy intakes on day 3 of each intervention week are shown in Figure 2. Repeated-measures ANOVA suggested differences in energy intakes at breakfast and lunch in the control week compared with the 3 intervention breakfast weeks (P < 0.01 and P = 0.048, respectively) but not at snack (P = 0.51) or over the school day (P = 0.45; data not shown). No significant differences in energy or nutrient intake were observed by children’s weight status.

FIGURE 2.

Energy intakes at breakfast, lunch, and snack on day 3 of each intervention week by breakfast type. Values are means ± SDs. Different letters indicate significantly different values. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Light-gray bars, control; medium-gray bars, HP; dark-gray bars, HPHF; solid bars, HF. HF, high-fiber diet; HP, high-protein diet; HPHF, high-protein and high-fiber diet.

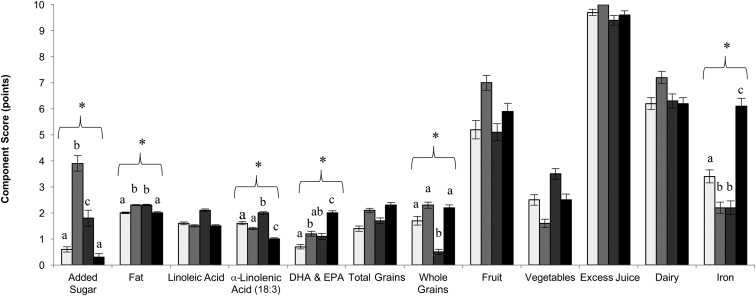

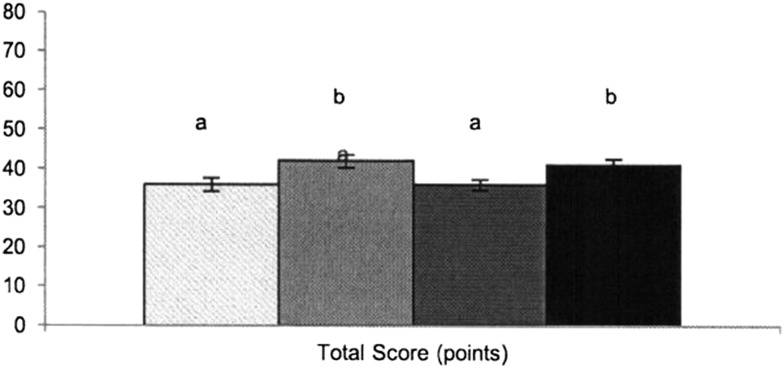

Diet quality component scores are shown in Figure 3. Differences in component scores between diets were seen in component 1 (added sugar; P < 0.001), component 2 (fat; P < 0.001), component 3 [linoleic acid (18:2)], component 4 [α-linolenic acid (18:3); P < 0.001], component 5 (DHA and EPA; P = 0.023), component 7 (whole grains; P < 0.001), and component 12 (iron; P < 0.001). Overall diet quality scores differed between intervention breakfasts (P = 0.027), and the highest diet quality scores were observed during the HP and HF breakfast conditions (Figure 4). There were no differences in diet quality scores by children’s weight status (P = 0.76).

FIGURE 3.

Mean RC-DQI component scores for intakes at breakfast, lunch, and snack on day 3 of each intervention week by breakfast type. Values are means ± SDs. Different letters indicate significantly different values. *P < 0.05. Light-gray bars, control; medium-gray bars, HP; dark-gray bars, HPHF; solid bars, HF. HF, high-fiber diet; HP, high-protein diet; HPHF, high-protein and high-fiber diet; RC-DQI, Revised Children’s Diet Quality Index.

FIGURE 4.

Mean total RC-DQI scores for intakes at breakfast, lunch, and snack on day 3 of each intervention week by breakfast type. Values are means ± SDs. Different letters indicate significantly different values, P < 0.05. Light-gray bars, control; medium-gray bars, HP; dark-gray bars, HPHF; solid bars, HF. HF, high-fiber diet; HP, high-protein diet; HPHF, high-protein and high-fiber diet; RC-DQI, Revised Children’s Diet Quality Index.

Discussion

Feelings of fullness contribute to energy balance, and some nutrients have been shown to affect fullness (38). A recent laboratory study in 29 children aged 10 y showed that increased protein content of breakfast (compared with higher carbohydrate content) led to increased energy expenditure, fat oxidation, and higher satiety (39). However, whether these associations hold true in preschool children has not been studied to date to our knowledge.

One challenge for research on feelings of fullness in young children is that preschool children have limited cognitive and concentration abilities. We used previously published methods to develop a new age-appropriate self-assessment tool for 4- and 5-y-olds to communicate their feeling of fullness (24, 25). Our tool does not require lengthy and individual training sessions and is therefore user-friendly for classroom or clinical settings.

The feeding intervention reported here is not consistent with a recent study in slightly older children (22). This may be due to the unique eating environment found in childcare centers and preschools. For safety and socialization reasons, center policy usually demands that all children sit at the table for snacks or meals, even when not hungry. Sitting at the table with food within easy reach may trigger eating because children’s eating behavior is socially facilitated (40). However, there is no evidence for this phenomenon and one could argue that preschoolers simply do not (yet) respond to changes in breakfast nutrient profile. Other results suggest that preschoolers consumed less energy when served an HP (compare with a high-carbohydrate) lunch and continued to consume less during an afternoon snack (41). Some might argue that there is no difference by the time of day, but research in children supports a unique role of breakfast for learning and food-intake control (42–44), which is not consistently reported in adults (45, 46).

As in all studies, limitations must be acknowledged. Ideally, our fullness-rating tool would have been validated by comparing results to a “gold standard” however, no such standard exists. Our results may have been different if fullness ratings had been collected ≥15 min after the meal, a time at which they may peak (42, 47). Due to the schedules of preschools, which include outdoor playtime after the meal, and preschoolers’ very limited ability to focus on a task while other “fun” activities are ongoing, it was necessary to collect fullness responses immediately after eating. Children in this study showed reduced energy intake during the intervention breakfast. This result is due in part to the study design, in which the intervention breakfasts had lower fat and higher protein and fiber density. In addition, preschoolers might have experienced food neophobia—an aversion to consuming new foods—which might have led to lower food intake. Food neophobia has been shown to disappear with repeated exposure to the foods. However, due to the study design, an acclimation period to the new foods could not be accommodated because of the burden on the participating teachers.

There is a lack of data on preschoolers’ daily intakes when they attend preschool. Several studies have indicated that children consume an estimated ≥66% of their daily energy and nutrients while at preschool; however, this estimate likely differs according to children’s socioeconomic background, with some low-income children consuming ≥90% of their diet while at preschool (34).

Although it would have been preferable to have dietary intake data on the children for the entire day to examine if diet quality varies in the 4 different breakfast conditions, the lack of complete intake reports did not allow for such analysis. However, because the observed diet in the preschools covered the same time period for each participant, calculation of a complete daily diet quality score was not necessary to compare diet quality between the 4 breakfast conditions. In lieu of comparing participants’ daily diet quality, we were able to assess the relative change in component and total scores under each of the study conditions. Interestingly, higher scores were seen with the HP and HF breakfasts, but the expected additive effect of combining the 2 was not observed. This result calls for more research to determine a possible ceiling effect or potentially overlapping fullness responses to protein and fiber. Overall diet quality is important to consider in obesity research, because children who skip breakfast are at higher risk of overweight and poor diet quality than are those who habitually consume breakfast (48). Better diet quality has been associated with improved BMI values among low-income overweight children (49).

Young children from families with low socioeconomic status are disproportionally affected by obesity (28). Early nutrition intervention to prevent and treat obesity is vital, because risk factors for chronic disease associated with obesity can present during the preschool years (6). This study targeted an identified research priority by offering data from a well-controlled intervention study in the preschool setting (50). Some of the study results could be used to develop future studies. For instance, a similar study design in which children are able to freely choose what they eat in the meals and snacks after the study breakfasts would allow a better understanding of a possible compensation mechanism. In addition, total diet should be included in the examination of feeding interventions in children. However, until data collection tools that allow the recording of food intake outside of preschools are developed or venues to increase parental self-report are available, capturing total diet remains a challenge.

In conclusion, we showed that the preschoolers in this study were able to communicate their feelings of fullness by using a newly developed pictorial assessment tool. Crossover exposure to 3 experimental and 1 control breakfast conditions showed an overall consistent change in energy and nutrient intakes for all 3 intervention breakfasts. Our results differ from other published results, in that the children in this study compensated for the reduced energy intake at breakfast during lunch. This study offers a further step toward a better understanding of preschool child nutrition. The role of satiation and satiety may be a critical aspect of obesity prevention and treatment in early childhood.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ningning Chen for important advice on the statistical analysis. MB oversaw the data collection and data analysis and provided the original draft of the manuscript; SK revised the manuscript and had primary responsibility for the final content; and SK, MB, WWC, RDM, and AJS assisted in designing the study and provided crucial feedback. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: HF, high-fiber; HP, high-protein; HPHF, high-protein and high-fiber; RC-DQI, Revised Children’s Diet Quality Index.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress on childhood obesity [Internet] [cited 2015 Mar 2]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/ChildhoodObesity/.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood obesity facts: prevalence of childhood obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan L, Blanck HM, Sherry B, Dalenius K, Grummer-Strawn LM. Trends in the prevalence of extreme obesity among US preschool-aged children living in low-income families, 1998–2010. JAMA 2012;308:2563–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biro FM, Wien M. Childhood obesity and adult morbidities. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91(Suppl):1499S–505S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magnussen CG, Koskinen J, Chen W, Thomson R, Schmidt MD, Srinivasan SR, Kivimaki M, Mattsson N, Kahonen M, Laitinen T, et al. Pediatric metabolic syndrome predicts adulthood metabolic syndrome, subclinical atherosclerosis, and type 2 diabetes mellitus but is no better than body mass index alone: the Bogalusa Heart Study and the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Circulation 2010;122:1604–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shashaj B, Bedogni G, Graziani MP, Tozzi AE, DiCorpo ML, Morano D, Tacconi L, Veronelli P, Contoli B, Manco M. Origin of cardiovascular risk in overweight preschool children: a cohort study of cardiometabolic risk factors at the onset of obesity. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168:917–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikkilä V, Räsänen L, Raitakari OT, Pietinen P, Viikari J. Consistent dietary patterns identified from childhood to adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Br J Nutr 2005;93:923–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med 1997;337:869–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johannsson E, Arngrimsson SA, Thorsdottir I, Sveinsson T. Tracking of overweight from early childhood to adolescence in cohorts born 1988 and 1994: overweight in a high birth weight population. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:1265–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinberger J, Moran A, Hong CP, Jacobs DR Jr, Sinaiko AR. Adiposity in childhood predicts obesity and insulin resistance in young adulthood. J Pediatr 2001;138:469–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sleddens EF, Kremers SP, Thijs C. The children’s eating behaviour questionnaire: factorial validity and association with body mass index in Dutch children aged 6–7. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008;5:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashcroft J, Semmler C, Carnell S, van Jaarsveld CH, Wardle J. Continuity and stability of eating behaviour traits in children. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008;62:985–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattes RD, Hollis J, Hayes D, Stunkard AJ. Appetite: measurement and manipulation misgivings. J Am Diet Assoc 2005;105(5, Suppl 1):S87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spence JC, Carson V, Casey L, Boule N. Examining behavioural susceptibility to obesity among Canadian pre-school children: the role of eating behaviours. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011;6:e501–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webber L, Hill C, Saxton J, Van Jaarsveld CH, Wardle J. Eating behaviour and weight in children. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33:21–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rebello CJ, Johnson WD, Martin CK, Xie W, O’Shea M, Kurilich A, Bordenave N, Andler S, van Klinken BJ, Chu YF, et al. Acute effect of oatmeal on subjective measures of appetite and satiety compared to a ready-to-eat breakfast cereal: a randomized crossover trial. J Am Coll Nutr 2013;32:272–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fallaize R, Wilson L, Gray J, Morgan LM, Griffin BA. Variation in the effects of three different breakfast meals on subjective satiety and subsequent intake of energy at lunch and evening meal. Eur J Nutr 2013;52:1353–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brennan IM, Luscombe-Marsh ND, Seimon RV, Otto B, Horowitz M, Wishart JM, Feinle-Bisset C. Effects of fat, protein, and carbohydrate and protein load on appetite, plasma cholecystokinin, peptide YY, and ghrelin, and energy intake in lean and obese men. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2012;303:G129–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattes R. Soup and satiety. Physiol Behav 2005;83:739–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flint A, Raben A, Blundell J, Astrup A. Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000;24:38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker BA, Sturm K, MacIntosh CG, Feinle C, Horowitz M, Chapman IM. Relation between food intake and visual analogue scale ratings of appetite and other sensations in healthy older and young subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004;58:212–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kral TV, Bannon AL, Chittams J, Moore RH. Comparison of the satiating properties of egg- versus cereal grain-based breakfasts for appetitie and energy intake control in children. Eat Behav 2016;20:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett C, Blissett J. Measuring hunger and satiety in primary school children: validation of a new picture rating scale. Appetite 2014;78:40–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faith MS, Kermanshah M, Kissileff HR. Development and preliminary validation of a silhouette satiety scale for children. Physiol Behav 2002;76:173–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keller KL, Assur SA, Torres M, Lofink HE, Thornton JC, Faith MS, Kissileff HR. Potential of an analog scaling device for measuring fullness in children: development and preliminary testing. Appetite 2006;47:233–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood D. How children think and learn. Malden (MA): Blackwell; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cameron AJ, Ball K, Pearson N, Lioret S, Crawford DA, Campbell K, Hesketh K, McNaughton SA. Socioeconomic variation in diet and activity-related behaviours of Australian children and adolescents aged 2–16 years. Pediatr Obes 2012;7:329–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight and obesity. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Child care and early education (ECE). Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.USDA. Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP). Beltsville (MD): USDA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ball SC, Benjamin SE, Ward DS. Development and reliability of an observation method to assess food intake of young children in child care. J Am Diet Assoc 2007;107:656–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kranz S, Hartman T, Siega-Riz AM, Herring AH. A diet quality index for American preschoolers based on current dietary intake recommendations and an indicator of energy balance. J Am Diet Assoc 2006;106:1594–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kranz S, McCabe GP. Examination of the five comparable component scores of the diet quality indexes HEI-2005 and RC-DQI us ing a nationally representative sample of 2–18 year old children: NHANES 2003–2006. J Obes 2013;2013:376314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ball SC, Benjamin SE, Ward DS. Dietary intakes in North Carolina child-care centers: are children meeting current recommendations? J Am Diet Assoc 2008;108:718–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mirza NM, Klein CJ, Palmer MG, McCarter R, He J, Ebbeling CB, Ludwig DS, Yanovski JA. Effects of high and low glycemic load meals on energy intake, satiety and hunger in obese Hispanic-American youth. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011;6:e523–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. BMI percentile calculator for child and teen. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.USDA Department of Health and Human Services. Head Start Program performance standards and other regulations. Beltsville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leidy HJ, Todd CB, Zino AZ, Immel JE, Mukherjea R, Shafer RS, Ortinau LC, Braun M. Consuming high-protein soy snacks affects appetite control, satiety, and diet quality in young people and influences select aspects of mood and cognition. J Nutr 2015;145:1614–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baum JI, Gray M, Binns A. Breakfasts higher in protein increase postprandial energy expenditure, increase fat oxidation, and reduce hunger in overweight children from 8 to 12 years of age. J Nutr 2015;145:2229–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clayton DA. Socially facilitated behavior. Q Rev Biol 1978;53:373–92. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Araya H, Hills J, Alvina M, Vera G. Short-term satiety in preschool children: a comparison between high protein meal and a high complex carbohydrate meal. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2000;51:119–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leidy HJ, Racki EM. The addition of a protein-rich breakfast and its effects on acute appetite control and food intake in ‘breakfast-skipping’ adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:1125–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marlatt KL, Farbakhsh K, Dengel DR, Lytle LA. Breakfast and fast food consumption are associated with selected biomarkers in adolescents. Prev Med Rep 2015;3:49–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kesztyüs D, Traub M, Lauer R, Kesztyus T, Steinacker JM. Correlates of longitudinal changes in the waist-to-height ratio of primary school children: implications for prevention. Prev Med Rep 2015;3:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kant AK, Graubard BI. Within-person comparison of eating behaviors, time of eating, and dietary intake on days with and without breakfast: NHANES 2005–2010. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102:661–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bi H, Gan Y, Yang C, Chen Y, Tong X, Lu Z. Breakfast skipping and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr 2015;18:3013–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leidy HJ, Apolzan JW, Mattes RD, Campbell WW. Food form and portion size affect postprandial appetite sensations and hormonal responses in healthy, nonobese, older adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:293–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dubois L, Girard M, Potvin Kent M, Farmer A, Tatone-Tokuda F. Breakfast skipping is associated with differences in meal patterns, macronutrient intakes and overweight among pre-school children. Public Health Nutr 2009;12:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lioret S, McNaughton SA, Cameron AJ, Crawford D, Campbell KJ, Cleland VJ, Ball K. Three-year change in diet quality and associated changes in BMI among schoolchildren living in socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Br J Nutr 2014;112:260–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sisson SB, Krampe M, Anundson K, Castle S. Obesity prevention and obesogenic behavior interventions in child care: a systematic review. Prev Med 2016;87:57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]