Abstract

Sperm hyperactivation is regulated by hormones present in the oviduct. In hamsters, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT) enhances hyperactivation associated with the 5HT2 receptor and 5HT4 receptor, while 17β-estradiol (E2) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) suppress the association of the estrogen receptor and GABAA receptor, respectively. In the present study, we examined the regulatory interactions among 5HT, GABA, and E2 in the regulation of hamster sperm hyperactivation. When sperm were exposed to E2 prior to 5HT exposure, E2 did not affect 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation. In contrast, GABA partially suppressed 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation when sperm were exposed to GABA prior to 5HT. GABA suppressed 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation associated with the 5HT2 receptor although it did not suppress 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation associated with the 5HT4 receptor. These results demonstrate that hamster sperm hyperactivation is regulated by an interaction between the 5HT2 receptor-mediated action of 5HT and GABA.

Keywords: γ-Aminobutyric acid, Capacitation, 5-Hydroxytryptamine, Hyperactivation, Sperm

After ejaculation, mammalian sperm are transported to the female reproductive organs and begin to be capacitated. In the oviduct, sperm are capacitated and exhibit hyperactivation, during which flagella exhibit a large amplitude and asymmetric beating pattern of movement [1,2,3]. In hamsters and mice, hyperactivated sperm may writhe and swim in a figure 8 pattern. The pattern of hyperactivated sperm movement differs among mammals [1, 3]. Hyperactivation creates the propulsive force for swimming in the viscous oviductal fluid and for penetrating the zona pellucida [1, 2, 4, 5]. Finally, capacitated mammalian sperm undergo the acrosome reaction (AR), a specialized form of exocytosis that occurs at the sperm head [1]. AR is required for penetration of the zona pellucida and for binding to the egg [1, 4, 5].

Recently, it was shown that mammalian sperm hyperactivation is modulated by some oviductal molecules [3, 4], including progesterone (P4) [6,7,8,9,10,11], 17β-estradiol (E2) [8, 10, 12], melatonin (Mel) [12, 13], 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT) [14], and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [11, 15, 16]. P4, Mel, and 5HT enhance sperm hyperactivation in hamsters [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. In contrast, E2 and GABA suppress the enhancement of hamster sperm hyperactivation by P4 and Mel [8, 10,11,12]. In human sperm, P4 and GABA induce sperm hyperactivation [6, 15]. Moreover, GABA also induces sperm hyperactivation in rams [16].

Although 5HT enhances hamster sperm hyperactivation, 5HT is generally a neurotransmitter with many functions and acts through various types of 5HT receptors in the tissues. Most 5HT receptors are G-protein coupled receptors and affect adenylyl cyclase or phospholipase C (PLC) [17, 18]. When adenylyl cyclase is stimulated by 5HT, cAMP concentration increases. PLC induces the production of inositol 1,4,5-tris-phosphate (IP3) and increases intracellular Ca2+ levels. 5HT and 5HT receptors have been identified in oocytes, cumulus-oocyte complexes, follicular fluids, and embryos in mammals [19]. In hamster sperm, it has been suggested that 5HT induces AR and enhances hyperactivation through the 5HT2 and 5HT4 receptors in a dose-dependent manner [14, 20]. The 5HT2 receptor is a G-protein coupled receptor and stimulates PLC-induced Ca2+-release from IP3 receptor-gated Ca2+-stores [17, 18]. The 5HT4 receptor is also a G-protein coupled receptor that stimulates adenylyl cyclase inducing cAMP production [17, 18]. Ca2+ and cAMP are important second messengers in the regulation of sperm hyperactivation [1,2,3,4].

As described above, in vivo hyperactivation is induced in capacitated sperm in the specific environment of the oviduct. Thus, it is important to examine the effects of oviductal molecules on the occurrence of hyperactivation in order to understand the regulatory mechanisms involved in modulating sperm functions in the female reproductive tracts. In our previous studies [7, 8, 10,11,12,13], we showed that in vitro hyperactivation of hamster sperm was modulated by a combination of enhancers and suppressors. P4 enhances hyperactivation most effectively at 20 ng/ml [7]. E2 and GABA suppressed P4-enhanced hyperactivation [8, 10, 11]. Enhancement of hyperactivation by 20 ng/ml P4 was suppressed by > 20 pg/ml E2 [8, 10]. Moreover, 5 nM–5 μM GABA suppressed the enhancement of hyperactivation by 20 ng/ml P4 [11]. Additionally, 1 nM Mel also enhanced hyperactivation [13]. We found that > 20 pg/ml E2 suppressed 1 nM Mel-enhanced hyperactivation although GABA did not affect Mel-enhanced hyperactivation [12]. Low concentrations (fM to pM) of 5HT enhanced hyperactivation through the 5HT2 receptor and high concentrations (nM to μM) of 5HT enhanced hyperactivation through the 5HT4 receptor [14]. However, the suppressors of 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation have not been identified. Because the concentrations of molecules affecting hamster sperm hyperactivation change during the estrous cycle and/or ovulation [5], we hypothesized that sperm are hyperactivated by interactions between enhancers and suppressors [3]. In the present study, we examined whether hamster sperm hyperactivation is regulated by the interaction between 5HT (as an enhancer) and E2 and/or GABA (as suppressors).

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

5HT, E2, 5-methoxytryptamine (MT), and α-methylserotonin maleate salt (MS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Bovine serum albumin fraction V was purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Other chemicals of reagent grade were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan).

Animals

All golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) used in the study were bred at the laboratory Animal Research Center of Dokkyo Medical University. The experiment was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Dokkyo Medical University (Experimental permission number: 0107) and carried out according to the Guidelines for Animal Experimentation of the university.

Preparation of hyperactivated sperm

Sperm were collected from the posterior epididymis of sexually mature (10–20-week-old) male hamsters. Hyperactivated sperm were prepared as described previously [12, 21]. Modified Tyrode′s albumin lactate pyruvate (mTALP) medium [12, 22] was used as a capacitation medium. A drop (~ 5 μl) of posterior epididymal sperm was placed on a culture dish (35-mm dish) (Iwaki, Asahi Glass, Tokyo, Japan) and 3 ml of the medium was carefully added to the dish. Hamster sperm were incubated for 5 min at 37°C to allow them to swim into the medium. The supernatant containing motile sperm was collected, placed on new dish, and incubated for 4 h at 37°C under 5% CO2 in air to induce hyperactivation. As a stock solution, 5HT (100 μM), MS (100 pM), bicuculline (Bic) (1 mM), and GABA (5 mM) were dissolved in pure water. MT (10 nM) and E2 (20 μg/ml) were dissolved in ethanol. GABA, E2, or vehicle was added to the mTALP medium after swim up, and after incubation for 5 min, 5HT, MS, MT, or vehicle was added to the medium (Figs. 1–3). Bic or vehicle was added to the medium after swim up, and after incubation for 5 min, GABA or vehicle was added to the medium. After additional incubation for 5 min, 5HT, MS, or vehicle was added to the medium again (Fig. 4). In all experiments, the maximal concentration of vehicle was 0.2%.

Fig. 1.

Effects of 17β-estradiol (E2) on enhancement of hyperactivation by 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT), α-methylserotonin maleate salt (MS), and 5-methoxytryptamine (MT). Percentages of hyperactivated sperm are shown when sperm were exposed to various concentrations of 5HT (A), 100 fM MS (B), or 10 pM MT (C) after exposure to 20 ng/ml E2. Data represent the mean ± SD. (A) (Vehicle): medium containing 0.1% (v/v) pure water and 0.1% (v/v) ethanol as a vehicle; (100 fM 5HT): medium containing 100 fM 5HT and vehicle; (100 pM 5HT): medium containing 100 pM 5HT and vehicle; (100 nM 5HT): medium containing 100 nM 5HT and vehicle; (E2): medium containing E2 and vehicle; (100 fM 5HT & E2): medium containing 100 fM 5HT, E2 and vehicle; (100 pM 5HT & E2): medium containing 100 pM 5HT, E2 and vehicle; (100 nM 5HT & E2): medium containing 100 nM 5HT, E2, and vehicle. (B) (Vehicle): same as above; (MS): medium containing MS and vehicle; (E2): medium containing E2 and vehicle; (MS & E2): medium containing MS, E2, and vehicle. (C) (Vehicle): medium containing 0.2% (v/v) ethanol as vehicle; (MT): medium containing MT and vehicle; (E2): medium containing E2 and vehicle; (MT & E2): medium containing MT, E2 and vehicle. *Significant difference compared with “Vehicle” or “E2” (P < 0.05).

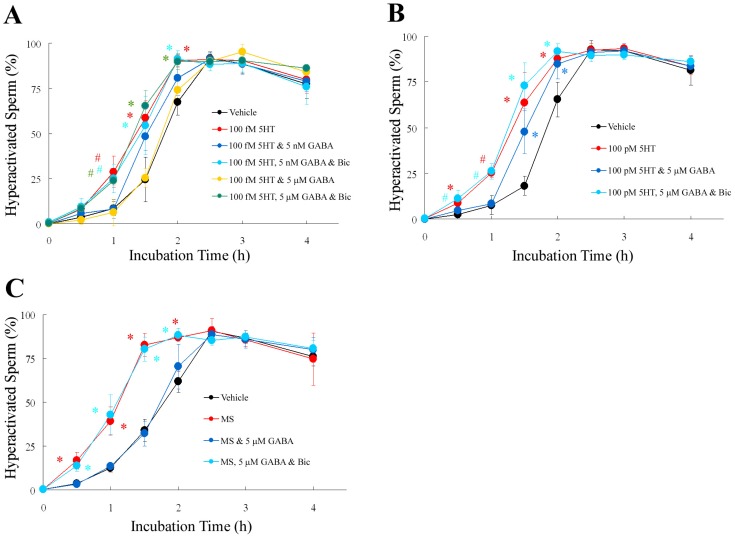

Fig. 3.

Dose-dependent negative effects of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) on enhancement of hyperactivation by 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT) and α-methylserotonin maleate salt (MS). Percentages of hyperactivated sperm are shown when sperm were exposed to 100 fM 5HT (A), 100 pM (B), 5HT or 100 fM MS (C) after exposure to various concentrations of GABA. Data represent the mean ± SD. (A) (Vehicle): medium containing 0.2% (v/v) pure water as vehicle; (100 fM 5HT): medium containing 100 fM 5HT and vehicle; (100 fM 5HT & all concentrations of GABA): medium containing 100 fM 5HT, respective concentrations of GABA and vehicle. (B) (Vehicle): same as above; (100 pM 5HT): medium containing 100 pM 5HT and vehicle; (100 pM 5HT & all concentrations of GABA): medium containing 100 pM 5HT, respective concentrations of GABA and vehicle. (C) (Vehicle): same as above; (MS): medium containing MS and vehicle; (MS & all concentrations of GABA): medium containing 100 fM MS, respective concentrations of GABA and vehicle. * Significant difference compared to “Vehicle” (P < 0.05). # Significant difference compared to “Vehicle” or “100 pM 5HT” (P < 0.05). $ Significant difference compared to “Vehicle” or “MS” (P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Involvement of GABAA receptor in regulation of hyperactivation by γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT), and α-methylserotonin maleate salt (MS). Percentage of hyperactivated sperm are shown when sperm were exposed to 5HT (A, B) or 100 fM MS (C) after exposure to GABA and 1 μM bicuculline (Bic). Data represent the mean ± SD. (A) (Vehicle): medium containing 0.3% (v/v) pure water as vehicle; (100 fM 5HT): medium containing 100 fM 5HT and vehicle; (100 fM 5HT & 5 nM GABA): medium containing 100 fM 5HT, 5 nM GABA, and vehicle: (100 fM 5HT, 5 nM GABA, & Bic): medium containing 100 fM 5HT, 5 nM GABA, Bic, and vehicle; (100 fM 5HT & 5 μM GABA): medium containing 100 fM 5HT, 5 μM GABA, and vehicle: (100 fM 5HT, 5 μM GABA, & Bic): medium containing 100 fM 5HT, 5 μM GABA, Bic, and vehicle. * Significant difference compared to “Vehicle” or “100 fM 5HT & 5 μM GABA” (P < 0.05). # Significant difference compared to “Vehicle”, “100 fM 5HT & 5 nM GABA” or “100 fM 5HT & 5 μM GABA” (P < 0.05). (B) (Vehicle): same as above; (100 pM 5HT): medium containing 100 pM 5HT and vehicle; (100 pM 5HT & 5 μM GABA): medium containing 100 pM 5HT, 5 μM GABA, and vehicle: (100 pM 5HT, 5 μM GABA, & Bic): medium containing 100 pM 5HT, 5 μM GABA, Bic, and vehicle. * Significant difference compared to “Vehicle” (P < 0.05). #Significant difference compared to “Vehicle” or “100 pM 5HT & 5 μM GABA” (P < 0.05). (C) (Vehicle): medium containing 0.3% (v/v) pure water as vehicle; (MS): medium containing MS and vehicle; (MS & 5 μM GABA): medium containing MS, 5 μM GABA, and vehicle: (MS, 5 μM GABA, & Bic): medium containing MS, 5 μM GABA, Bic, and vehicle. * Significant difference compared to “Vehicle” or “MS & 5 μM GABA” (P < 0.05).

Measurement of motility and hyperactivation of sperm

Motility and hyperactivation measurements were performed as described previously [12, 21] with some modifications. Motile sperm were recorded on videotape via a CCD camera (Progressive 3CCD, Sony, Tokyo, Japan) attached to a microscope (IX70, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with phase-contrast illumination and a small CO2 incubator (MI-IBC, Olympus). Each observation was performed at 37°C, recorded for 2 min, and analyzed by manually counting the numbers of total sperm, motile sperm, and hyperactivated sperm in 4 different fields of observation. Analyses were conducted in a blinded manner. Motile sperm exhibiting asymmetric and whiplash-like flagellar movement and a circular and/or octagonal swimming locus were defined as hyperactivated sperm [3, 23]. Motile sperm (%) and hyperactivated sperm (%) were respectively defined as the number of motile sperm/number of total sperm × 100 and the number of hyperactivated sperm/number of total sperm × 100. Experiments were performed four times using four hamsters. When the percentage of motile sperm was 80% or less, the experiment was re-performed. Statistical analysis was carried out using the post-hoc test of ANOVA using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Japan, Tokyo, Japan) with the add-in software Statcel2 (OMS Publishing, Saitama, Japan). Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Effects of E2 and GABA on 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation

We previously showed that 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation occurred through the 5HT2 and 5HT4 receptors in hamster sperm [14]. Low concentrations (1 fM–100 pM) of 5HT enhanced sperm hyperactivation through the 5HT2 receptor, while high concentrations (1 nM–1 μM) of 5HT enhanced sperm hyperactivation through the 5HT4 receptor. In the present study, we used 100 fM 5HT to stimulate the 5HT2 receptor, 100 nM 5HT to stimulate the 5HT4 receptor, and 100 pM 5HT as an average of effective concentration and probable stimulator of the 5HT2 receptor. In addition, we used two 5HT receptor-specific agonists: MS (5HT2 receptor-specific agonist) and MT (5HT4 receptor-specific agonist).

First, we examined whether hamster sperm hyperactivation was regulated by the interaction between 5HT and E2. As shown in Fig. 1A, hamster sperm were exposed to 100 fM, 100 pM, and 100 nM 5HT after exposure to 20 ng/ml E2. Although 20 ng/ml E2 clearly suppressed P4-enhanced and Mel-enhanced hyperactivation [8, 10, 12], the 5HT-dependent increases in the percentage of hyperactivated sperm after 1, 1.5, or 2 h incubation were not affected by exposure to 20 ng/ml E2. In addition, when hamster sperm were exposed to 100 fM MS (Fig. 1B) or 10 pM MT (Fig. 1C) after exposure to 20 ng/ml E2, the 5HT receptor agonist-dependent increases in the percentage of hyperactivated sperm after 1, 1.5, or 2 h incubation were not affected by exposure to 20 ng/ml E2.

In the next step, sperm were exposed to 100 fM, 100 pM, and 100 nM 5HT after exposure to 5 nM or 5 μM GABA (Figs. 2A and 2B). GABA at range of 5 nM to 5 μM suppressed P4-enahnced hyperactivation [11]. GABA at 5 nM significantly suppressed 100 fM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation after incubation for 1 and 1.5 h. However, 5 nM GABA did not suppress the enhancement of hyperactivation by 100 pM and 100 nM 5HT. In addition, 5 μM GABA significantly suppressed 100 fM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation after incubation for 1 and 1.5 h. After incubation for 1 h, 5 μM GABA significantly suppressed 100 pM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation. However, 5 μM GABA did not suppress the enhancement of hyperactivation by 100 nM 5HT.

Fig. 2.

Effects of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) on enhancement of hyperactivation by 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT), α-methylserotonin maleate salt (MS), and 5-methoxytryptamine (MT). Percentages of hyperactivated sperm are shown when sperm were exposed to various concentration of 5HT (A, B), 100 fM MS (C), or 10 pM MT (D) after exposure to 5 nM or 5 μM GABA. Data represent mean ± SD. (A) (Vehicle): medium containing 0.2% (v/v) pure water as vehicle; (100 fM 5HT): medium containing 100 fM 5HT and vehicle; (100 pM 5HT): medium containing 100 pM 5HT and vehicle; (100 nM 5HT): medium containing 100 nM 5HT and vehicle; (5 nM GABA): medium containing 5 nM GABA and vehicle; (100 fM 5HT & 5 nM GABA): medium containing 100 fM 5HT, 5 nM GABA, and vehicle; (100 pM 5HT & 5 nM GABA): medium containing 100 pM 5HT, 5 nM GABA, and vehicle; (100 nM 5HT & 5 nM GABA): medium containing 100 nM 5HT, 5 nM GABA, and vehicle. * Significant difference compared to “Vehicle” or “5 nM GABA” (P < 0.05). ** Significant difference compared to “Vehicle”, “5 nM GABA”, or “100 fM 5HT & 5 nM GABA” (P < 0.05). (B) (Vehicle): medium containing 0.2% (v/v) pure water as vehicle; (100 fM 5HT): medium containing 100 fM 5HT and vehicle; (100 pM 5HT): medium containing 100 pM 5HT and vehicle; (100 nM 5HT): medium containing 100 nM 5HT and vehicle; (5 μM GABA): medium containing 5 μM GABA and vehicle; (100 fM 5HT & 5 μM GABA): medium containing 100 fM 5HT, 5 μM GABA, and vehicle; (100 pM 5HT & 5 μM GABA): medium containing 100 pM 5HT, 5 μM GABA, and vehicle; (100 nM 5HT & 5 μM GABA): medium containing 100 nM 5HT, 5 μM GABA, and vehicle. *Significant difference compared to “Vehicle” or “5 μM GABA” (P < 0.05). **Significant difference compared to “Vehicle”, “5 μM GABA”, or “100 fM 5HT & 5 μM GABA” (P < 0.05). #Significant difference compared to “Vehicle”, “5 μM GABA”, “100 fM 5HT & 5 μM GABA”, or “100 pM 5HT & 5 μM GABA” (P < 0.05). (C) (Vehicle): same as above; (MS): medium containing MS and vehicle; (MS & 5 nM GABA): medium containing MS, 5 nM GABA, and vehicle; (MS & 5 μM GABA): medium containing MS, 5 μM GABA, and vehicle. *Significant difference compared to “Vehicle” (P < 0.05). **Significant difference compared to “Vehicle” or “MS & 5 μM GABA” (P < 0.05). (D) (Vehicle): medium containing 0.1% (v/v) pure water and 0.1% (v/v) ethanol as vehicle; (MT): medium containing MT and vehicle; (MT & 5 nM GABA): medium containing MT, 5 nM GABA, and vehicle; (MT & 5 μM GABA): medium containing MT, 5 μM GABA, and vehicle. *Significant difference compared to “Vehicle” (P < 0.05).

Because 100 fM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation was strongly suppressed by GABA (Figs. 2A and 2B), we examined whether GABA suppressed the enhancement of hyperactivation via stimulation of the 5HT2 receptor. When sperm were exposed to 100 fM MS (5HT2 receptor agonist) after exposure to 5 nM or 5 μM GABA, MS-enhanced hyperactivation was significantly suppressed by only 5 μM GABA after incubation for 1 and 1.5 h although it was not suppressed by 5 nM GABA (Fig. 2C). When hamster sperm were exposed to 10 pM MT (5HT4 receptor agonist) after exposure 5 nM or 5 μM GABA, the percentage of hyperactivated sperm and MT-enhanced hyperactivated sperm were not affected (Fig. 2D).

Dose-dependent suppression of 5HT2 receptor-mediated enhancement of hyperactivation by GABA

Because 5 nM or 5 μM GABA suppressed 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation associated with 5HT2 receptor (Fig. 2), we examined the dose-dependent suppression of 5HT2 receptor-mediated enhancement of hyperactivation by GABA (Fig. 3). When sperm were exposed to 100 fM 5HT after exposure to 5 pM–5 μM GABA, GABA significantly suppressed 100 fM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). After incubation for 1 h, 5 nM–5 μM GABA significantly suppressed 100 fM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation. After incubation for 1.5 h, 50 nM–5 μM GABA significantly suppressed 100 fM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation. GABA at 500 pM and 5 nM slightly suppressed 100 fM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation although their suppression was not significant compared with the vehicle and 100 fM 5HT. After incubation for 2 h, 5 μM GABA only significantly suppressed 100 fM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation.

As shown in Fig. 3B, GABA significantly suppressed 100 pM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation in a dose-dependent manner when sperm were exposed to 100 pM 5HT after exposure to 5 pM–5 μM GABA. After incubation for 1 h, 5 μM GABA significantly suppressed 100 pM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation. GABA at 500 nM significantly suppressed 100 pM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation, while 100 pM 5HT significantly enhanced hyperactivation following exposure to 500 nM GABA. GABA at 50 nM slightly suppressed 100 pM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation although its suppression was not significant. After incubation for 1.5 h, 50 nM–5 μM GABA slightly suppressed 100 pM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation although their suppression were not significant compared with vehicle and 100 pM 5HT. After incubation for 2 h, GABA did not suppress 100 pM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation.

When sperm were exposed 100 fM MS after exposure to 5 nM–5 μM GABA, GABA significantly suppressed MS-enhanced hyperactivation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). After incubation for 0.5 and 1 h, 5 μM GABA significantly suppressed MS-enhanced hyperactivation. GABA at 500 nM slightly suppressed MS-enhanced hyperactivation although its suppression was not significant. After incubation for 1.5 h, 5 μM GABA significantly suppressed MS-enhanced hyperactivation. After incubation for 2 h, GABA did not suppress MS-enhanced hyperactivation.

Involvement of the GABAA receptor in suppression of 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation by GABA

Previously, we showed that GABA suppressed P4-enhanced hyperactivation through the GABAA receptor [11]. Because GABA suppressed 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation associated with the 5HT2 receptor (Figs. 2 and 3), we examined the involvement of the GABAA receptor in the suppression of 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation by GABA (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4A, 100 fM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation was significantly suppressed by 5 nM GABA, while this suppression was negated by 1 μM Bic (GABAA receptor inhibitor) after incubation for 1 h. Moreover, 100 fM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation was suppressed by 5 μM GABA, but this suppression was also negated by Bic after incubation for 1, 1.5, and 2 h. As shown in Fig. 4B, 5 μM GABA suppressed 100 pM 5HT-enhanced sperm hyperactivation, which was negated by Bic after incubation for 0.5 and 1 h. As shown in Fig. 4C, 100 fM MS-enhanced hyperactivation was significantly suppressed by 5 μM GABA, and its suppression was negated by 1 μM Bic after incubation for 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 h.

Discussion

Capacitation is a necessary event that occurs in the female reproductive tract. The observable phenotype associated with capacitation consists of AR and hyperactivation. Some hormones and neurotransmitters are known to induce AR. P4, Mel, 5HT, and GABA induce AR in hamsters, humans, mice, rams, and rats [20, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. P4-induced AR is suppressed by E2 in human [24, 34]. Additionally, hyperactivation is also enhanced by some hormones and neurotransmitters in a dose-dependent manner. P4, Mel, and 5HT enhance hyperactivation in hamsters and humans [6, 7, 13, 14]. GABA also enhances hyperactivation in rams and humans, but not in hamsters, [11, 15, 16]. P4-enhanced hyperactivation is dose-dependently suppressed by E2 and GABA in hamsters [8, 10, 11]. In addition, Mel-enhanced hyperactivation of hamster sperm is suppressed by E2 in a dose-dependent manner [12]. In humans and hamsters, GABA binds to the GABAA receptor [11, 15]. However, P4 also binds to the GABAA receptor in humans [15] although in hamsters P4 binds to its receptor [7, 8, 11]. Generally, the GABAA receptor is a receptor-coupled Cl- channel and induces Cl- influx and hyperpolarization [39]. Therefore, in humans, P4 and GABA may bind to the GABAA receptor and induce hyperactivation through Cl- influx and hyperpolarization. In contrast, in hamsters, P4 likely binds to its receptor and enhances hyperactivation. In addition, GABA binds to the GABAA receptor and suppresses P4-enhanced hyperactivation. Previous studies [7, 8, 11, 15] suggested that P4 and GABA regulate hyperactivation through a species-specific regulatory mechanism in humans and hamsters.

In the present study, we examined whether 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation was suppressed by E2 and/or GABA in hamster sperm. E2 at 20 ng/ml, which suppressed P4- and Mel-enhanced hyperactivation [8, 10, 12], did not affect 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation (Fig. 1). In addition, we also found that 5HT-dependent enhancement of hyperactivation in the sperm after 1, 1.5, or 2 h incubation was not affected by exposure to higher concentrations of E2 (20 μg/ml) (data not shown). In contrast, GABA suppressed the enhanced hyperactivation by 100 fM and 100 pM 5HT (Fig. 2). Previously, we demonstrated that low concentrations (fM–pM order) of 5HT enhanced hyperactivation through the 5HT2 receptor, while high concentrations (nM–μM order) of 5HT enhanced hyperactivation through the 5HT4 receptor [14]. Thus, GABA likely suppressed 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation through the 5HT2 receptor. Using the 5HT2 receptor agonist (MS) and 5HT4 receptor agonist (MT) (Fig. 2), we found that MS-enhanced hyperactivation was suppressed by GABA, while MT-enhanced hyperactivation was not. These observations suggest that GABA suppressed 5HT2 receptor-mediated enhancement of hyperactivation, but not 5HT4 receptor-mediated enhancement. Moreover, the inhibitory effect of GABA on 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation was concentration-dependent (Figs. 2 and 3). GABA at 5 nM (nM order) suppressed 100 fM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation although it did not suppress 100 pM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation and MS-enhanced hyperactivation. In contrast, GABA at 5 μM suppressed 100 fM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation, 100 pM 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation, and MS-enhanced hyperactivation. Based on those results, suppression of 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation by 5 μM GABA was stronger than that by 5 nM GABA. Moreover, stimulation by 100 pM 5HT was stronger that that by 100 fM 5HT because stimulation by 100 pM 5HT was not suppressed by 5 nM GABA, while stimulation by 100 fM 5HT was suppressed by 5 nM GABA. Therefore, our previous study [14] and the present results suggest that 5HT dose-dependently enhances sperm hyperactivation through the 5HT2 and 5HT4 receptors, while enhancement via the 5HT2 receptor is suppressed by GABA. We did not identify molecules that suppressed the enhancement involved in 5HT4 receptor activity.

We previously showed that GABA suppressed P4-enhanced hyperactivation of hamster sperm through the GABAA receptor [11]. In the present study, GABA also suppressed the enhancement of hyperactivation via the 5HT2 receptor through the GABAA receptor (Fig. 4). The GABAA receptor is a ligand-gated Cl- channel that induces hyperpolarization [39]. Because GABA inhibited the binding of P4 to its receptor through the GABAA receptor, we predict that GABA bound to the GABAA receptor induces Cl- influx and hyperpolarization to inhibit the binding of P4 to its receptor [11]. However, the mechanisms of the negative effects of GABA on P4-enhanced hyperactivation remain unclear. In the present study, GABA suppressed the enhancement of hyperactivation via the 5HT2 receptor through the GABAA receptor. GABA may bind to the GABAA receptor to induce Cl- influx and hyperpolarization, which suppresses the enhancement of hyperactivation via the 5HT2 receptor although the mechanisms of the negative effects of GABA on enhanced hyperactivation via the 5HT2 receptor remain unclear. A common regulatory mechanism exists between P4-enhanced hyperactivation and enhanced hyperactivation via the 5HT2 receptor. P4 enhances sperm hyperactivation through Ca2+-signaling associated with PLC, IP3 receptor, and protein kinase C [9]. The enhancement of hyperactivation via 5HT2 receptor may be regulated through Ca2+-signaling associated with PLC and the IP3 receptor [11] because the 5HT2 receptor in neurons stimulates PLC-induced Ca2+-release form IP3 receptor-gated Ca2+-stores [17, 18]. In future studies, we will examine the inhibitory mechanisms by which GABA suppresses P4-enhanced hyperactivation and enhances hyperactivation via the 5HT2 receptor.

5HT is mainly released from cumulus cells in female reproductive organs [19]. The 5HT content in the rat oviduct ranges from 2.06 to 3.34 μg/g fresh tissue [35]. In human, the concentrations of 5HT in preovulatory follicles and cystic degenerated follicles are 14.3 ± 8.9 and 12.2 ± 6.2 μg/100 ml, respectively [36]. In contrast, greater than 2.5-fold greater levels of GABA are found in the rat oviduct than in the rat brain [37]. In addition, the GABA concentration changes in the rat female genital tract with the estrous cycle [37, 38]. GABA concentration at the pro-estrous stage was found to be higher than at the estrous stage [37, 38]. Therefore, the concentration of 5HT and GABA appear to change during the estrous cycle. Based on the results of our previous study [14] and the present study, regulation of the hyperactivation by 5HT (enhancer) and GABA (suppressor) may be associated with the estrous cycle.

Recently, we reported that several hormones and neurotransmitters regulate hamster sperm hyperactivation [7, 8, 10,11,12,13,14]. P4, Mel, and 5HT enhance hyperactivation [7, 13, 14]. P4-enahnced hyperactivation is suppressed by E2 [8, 10] and GABA [11] and Mel-enhanced hyperactivation is suppressed by E2 [12]. In the present study, we showed that the 5HT-enhanced hyperactivation involved in the 5HT2 receptor was suppressed by GABA. Thus, hamster sperm hyperactivation is regulated by at least three enhancers and two suppressor. Moreover, the regulation of hyperactivation by these hormones and neurotransmitters may be associated with the estrous cycle and the interaction between the sperm and oocyte (or cumulus-oocytes complexes).

Declaration of interest: Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding: This research received no funding from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

References

- 1.Yanagimachi R. Mammalian fertilization. In: Knobil E, Neill JD (ed.), The Physiology of Reproduction Vol. 2, 2nd ed. New York: Raven Press; 1994: 189–317.

- 2.Mohri H, Inaba K, Ishijima S, Baba SA. Tubulin-dynein system in flagellar and ciliary movement. Proc Jpn Acad. Ser B 2012; 88: 397–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujinoki M, Takei GL, Kon H. Non-genomic regulation and disruption of spermatozoal in vitro hyperactivation by oviductal hormones. J Physiol Sci 2016; 66: 207–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujinoki M. Non-genomic regulation of mammalian sperm hyperactivation. Reprod Med Biol 2009; 8: 47–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schillo KK. Reproductive Physiology of Mammals: From Farm to Field and Beyond. New York: Delmar; 2009: 214–338. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang J, Serres C, Philibert D, Robel P, Baulieu EE, Jouannet P. Progesterone and RU486: opposing effects on human sperm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994; 91: 529–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noguchi T, Fujinoki M, Kitazawa M, Inaba N. Regulation of hyperactivation of hamster spermatozoa by progesterone. Reprod Med Biol 2008; 7: 63–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujinoki M. Suppression of progesterone-enhanced hyperactivation in hamster spermatozoa by estrogen. Reproduction 2010; 140: 453–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujinoki M. Progesterone-enhanced sperm hyperactivation through IP3-PKC and PKA signals. Reprod Med Biol 2013; 12: 27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujinoki M. Regulation and disruption of hamster sperm hyperactivation by progesterone, 17β-estradiol and diethylstilbestrol. Reprod Med Biol 2014; 13: 143–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kon H, Takei GL, Fujinoki M, Shinoda M. Suppression of progesterone-enhanced hyperactivation in hamster spermatozoa by γ-aminobutyric acid. J Reprod Dev 2014; 60: 202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujinoki M, Takei GL. Estrogen suppresses melatonin-enhanced hyperactivation of hamster spermatozoa. J Reprod Dev 2015; 61: 287–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujinoki M. Melatonin-enhanced hyperactivation of hamster sperm. Reproduction 2008; 136: 533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujinoki M. Serotonin-enhanced hyperactivation of hamster sperm. Reproduction 2011; 142: 255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calogero AE, Hall J, Fishel S, Green S, Hunter A, DAgata R. Effects of γ-aminobutyric acid on human sperm motility and hyperactivation. Mol Hum Reprod 1996; 2: 733–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de las Heras MA, Valcarcel A, Perez LJ. In vitro capacitating effect of gamma-aminobutyric acid in ram spermatozoa. Biol Reprod 1997; 56: 964–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noda M, Higashida H, Aoki S, Wada K. Multiple signal transduction pathways mediated by 5-HT receptors. Mol Neurobiol 2004; 29: 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganong WF. Synaptic & junctional transmission. In: Ganong WF (ed.), Revies of Medical Physiology, 22 ed. New York: the MaGraw-Hill companies; 2005: 85–127.

- 19.Dubé F, Amireault P. Local serotonergic signaling in mammalian follicles, oocytes and early embryos. Life Sci 2007; 81: 1627–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meizel S, Turner KO. Serotonin or its agonist 5-methoxytryptamine can stimulate hamster sperm acrosome reactions in a more direct manner than catecholamines. J Exp Zool 1983; 226: 171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujinoki M, Suzuki T, Takayama T, Shibahara H, Ohtake H. Profiling of proteins phosphorylated or dephosphorylated during hyperactivation via activation on hamster spermatozoa. Reprod Med Biol 2006; 5: 123–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maleszewski M, Kline D, Yanagimachi R. Activation of hamster zona-free oocytes by homologous and heterologous spermatozoa. J Reprod Fertil 1995; 105: 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujinoki M, Ohtake H, Okuno M. Serine phosphorylation of flagellar proteins associated with the motility activation of hamster spermatozoa. Biomed Res 2001; 22: 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baldi E, Luconi M, Muratori M, Marchiani S, Tamburrino L, Forti G. Nongenomic activation of spermatozoa by steroid hormones: facts and fictions. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2009; 308: 39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casao A, Mendoza N, Pérez-Pé R, Grasa P, Abecia J-A, Forcada F, Cebrián-Pérez JA, Muino-Blanco T. Melatonin prevents capacitation and apoptotic-like changes of ram spermatozoa and increases fertility rate. J Pineal Res 2010; 48: 39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.du Plessis SS, Hagenaar K, Lampiao F. The in vitro effects of melatonin on human sperm function and its scavenging activities on NO and ROS. Andrologia 2010; 42: 112–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukami K, Yoshida M, Inoue T, Kurokawa M, Fissore RA, Yoshida N, Mikoshiba K, Takenawa T. Phospholipase Cdelta4 is required for Ca2+ mobilization essential for acrosome reaction in sperm. J Cell Biol 2003; 161: 79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osman RA, Andria ML, Jones AD, Meizel S. Steroid induced exocytosis: the human sperm acrosome reaction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1989; 160: 828–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sueldo CE, Oehninger S, Subias E, Mahony M, Alexander NJ, Burkman LJ, Acosta AA. Effect of progesterone on human zona pellucida sperm binding and oocyte penetrating capacity. Fertil Steril 1993; 60: 137–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi QX, Roldan ERS. Evidence that a GABAA-like receptor is involved in progesterone-induced acrosomal exocytosis in mouse spermatozoa. Biol Reprod 1995; 52: 373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu JH, He XB, Wu Q, Yan YC, Koide SS. Biphasic effect of GABA on rat sperm acrosome reaction: involvement of GABA(A) and GABA(B) receptors. Arch Androl 2002; 48: 369–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu JH, He XB, Wu Q, Yan YC, Koide SS. Subunit composition and function of GABAA receptors of rat spermatozoa. Neurochem Res 2002; 27: 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wistrom CA, Meizel S. Evidence suggesting involvement of a unique human sperm steroid receptor/Cl- channel complex in the progesterone-initiated acrosome reaction. Dev Biol 1993; 159: 679–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luconi M, Francavilla F, Porazzi I, Macerola B, Forti G, Baldi E. Human spermatozoa as a model for studying membrane receptors mediating rapid nongenomic effects of progesterone and estrogens. Steroids 2004; 69: 553–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Juorio AV, Chedrese PJ, Li XM. The influence of ovarian hormones on the rat oviductal and uterine concentration of noradrenaline and 5-hydroxytryptamine. Neurochem Res 1989; 14: 821–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bòdis J, Bognàr Z, Hartmann G, Török A, Csaba IF. Measurement of noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin contents in follicular fluid of human graafian follicles after superovulation treatment. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1992; 33: 165–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martín del Rio R. γ-aminobutyric acid system in rat oviduct. J Biol Chem 1981; 256: 9816–9819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Louzan P, Gallardo MGP, Tramezzani JH. Gamma-aminobutyric acid in the genital tract of the rat during the oestrous cycle. J Reprod Fertil 1986; 77: 499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chebib M, Johnston GA. GABA-Activated ligand gated ion channels: medicinal chemistry and molecular biology. J Med Chem 2000; 43: 1427–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]