Abstract

The phnD gene of Escherichia coli encodes the periplasmic binding protein of the phosphonate uptake and utilization pathway. We have crystallized and determined structures of E. coli PhnD (EcPhnD) in the absence of ligand and in complex with the environmentally abundant 2-aminoethylphosphonate (2AEP). Similar to other bacterial periplasmic binding proteins, 2AEP binds near the center of mass of EcPhnD in a cleft formed between two lobes. Comparison of the open, unliganded structure with the closed 2AEP-bound structure shows that the two lobes pivot around a hinge by ~70° between the two states. Extensive hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions stabilize 2AEP, which binds to EcPhnD with low nanomolar affinity. These structures provide insight into phosphonate uptake by bacteria and facilitated the rational design of high signal-to-noise phosphonate biosensors based both on coupled small molecule dyes and autocatalytic fluorescent proteins.

INTRODUCTION

Under phosphorus-limiting conditions, the Pho regulon of E. coli activates a number of pathways to increase uptake of phosphorus-containing compounds1, including the 14-gene phn operon (phnC-P) allowing uptake and utilization of phosphonate (Pn)-containing compounds 2. phnC-E encode an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter complex for Pn, of which the protein product of phnD is a periplasmic binding protein (PBP) that recognizes and binds Pn. phnF encodes a putative transcriptional regulator 3, while the phnGHIJKLM genes all appear to be essential for the carbon-phosphorus lyase activity 2. Recently it was shown that phnGHIJK assemble into a large (~260 kDa), soluble protein complex 4, but the biochemical details of phosphonate catabolism are still not well understood. phnNOP have ribosyl 1,5-bisphosphokinase 5, aminophosphonate N-acetyltransferase 6, and phosphoribosyl cyclic phosphodiesterase 7 activities, respectively.

Periplasmic binding proteins enable selective nutrient uptake and mediate chemotactic responses in bacteria 8, and share a characteristic structure: two (or more, in rare cases) globular domains linked by a β-strand hinge region, with a ligand-binding site at the domain interface near the center of mass 9. A domain reorientation about the hinge is typically coupled to ligand binding, producing a movement that brings the two domains together to enclose the ligand 10. PBPs specific to a diverse range of ligands have been discovered, including carbohydrates 11, amino acids 12, transition metal ions 13, polyamines 14, and vitamins 15, among others.

The characteristic hinged, two-domain fold appears in a number of proteins with divergent sequences, including enzymes 16, transcriptional repressors 17, and neurotransmitter receptors 18. Part of this functional heterogeneity is no doubt due to this fold being particularly well-adapted to evolve binding pockets: the binding-site residues are positioned on the surface of the domains in the open form, permitting greater evolutionary plasticity 19, but upon binding-induced domain reorientation, the environment of the ligand is essentially that of a protein interior 11.

Pn compounds are environmentally abundant, including a significant manmade contribution from herbicides, insecticides, detergents, and chelating agents (including etidronic acid, widely used as an anti-oxidant and corrosion inhibitor). Several Pn compounds have potent bioactivities in humans, including antibiotics like fosfomycin, chemical warfare agents such as VX and sarin, and pharmaceuticals such as adefovir (for review of phosphonate interactions with the environment see 20). Previous biochemical characterization of EcPhnD demonstrated that it binds 2-aminoethylphosphonate (2AEP), the most abundant environmental Pn, with an affinity of ~5 nM 21. In that work, the authors also sought to prepare a fluorescent biosensor for Pn using EcPhnD by covalent attachment of environmentally sensitive fluorescent dyes to introduced cysteines. In the absence of an experimental structure of EcPhnD, however, they relied on a homology model from the sulfate-binding protein of E. coli, which shares only 13% sequence identity, for site-directed introduction of cysteine side-chains. This hampered biosensor construction and prevented engineering of altered binding specificity.

In this work we report crystal structures of the ligand-bound and -free (apo) forms of EcPhnD that provide insight into the process of environmental Pn recognition and transport in bacteria. As seen with other PBP structures, there is a large (tens of Ångstroms) conformational change between the two forms. Such large allosteric rearrangements can be transduced into fluorescent, electrochemical, or other observable signals 22. Fluorescent indicators can be made from either coupled small molecule dyes 22 or by genetic fusion to fluorescent protein(s) 23. We have recently published a method for creating high signal-to-noise single-wavelength sensors for small molecules from periplasmic binding proteins, using E. coli maltose-binding protein as a test case 24. The technique involves insertion of circularly permuted variants of fluorescent proteins, e.g. circularly permuted green fluorescent protein (cpGFP), at positions in the PBP sequence predicted to undergo dramatic allosteric rearrangement upon ligand binding.

With the determination of the ligand-bound structure of EcPhnD, we were able to prioritize dye attachment locations and cpGFP insertion sites for the creation of high-response indicators. We created dye-coupled biosensors with ~10-fold larger fluorescence increases than previously published 21, and we engineered genetically encoded 25 phosphonate indicators, which may be useful for visualizing phosphonate uptake and translocation in intact organisms.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ligand binding by PhnD

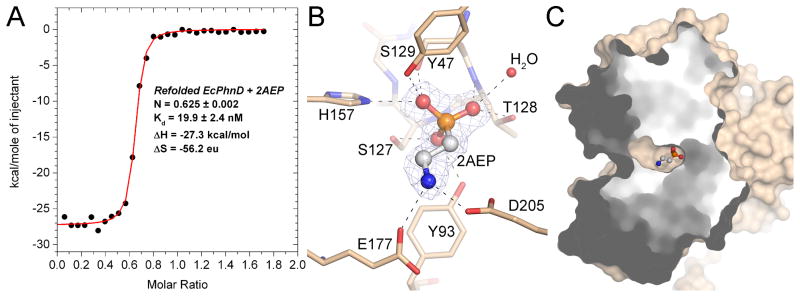

EcPhnD binds several phosphonate compounds, with 2AEP demonstrating the highest affinity of tested compounds 21. We directly measured the affinity of purified EcPhnD for 2AEP using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and found that the data were best fit using a two-site model with dissociation constants of 10 nM and 35 nM (supplemental Fig. S1). ITC of EcPhnD that was denatured, washed, and refolded fit a single-site binding model with a dissociation constant of 20 nM (Fig. 1A), suggesting that displacement of a ligand already bound to a fraction of the EcPhnD molecules was responsible for the observed two-site ITC profile. The stoichiometries of the ITC titrations are less than one, possibly due to tightly-bound copurified ligand, incomplete refolding, or another condition that renders a fraction of the EcPhnD molecules incapable of ligand binding. To observe the interactions between EcPhnD and phosphonates at atomic resolution, we added a five-fold molar excess of 2AEP to purified EcPhnD and crystallized the complex. The EcPhnD-2AEP structure was determined using multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) data to 2.5 Å resolution collected from selenomethionine-substituted protein crystals and refined against a native dataset to 1.7 Å resolution (Table 1). The ligand-binding site of EcPhnD is located approximately at its center of mass, mostly buried between the two lobes, and is composed of primarily hydrophilic amino acids from each lobe (Figs. 1B–C, 2A–C). Hydrogen bonds to the phosphonate oxygen atoms of 2AEP are observed from the side-chains of amino acids Tyr47, Tyr93, Ser127, Thr128, Ser129, and His157, as well as an ordered water molecule at the N-terminus of helix α3, and from the backbone amide nitrogen atoms of Thr128 and Ser129 at the N-terminus of helix α5 (Fig. 1B). His157 and the positive dipole at the N-terminus of helix α5 presumably help to stabilize the negative charge of the phosphonate group. Given that the phosphonate oxygens are tightly packed into the EcPhnD binding site and saturated with polar interactions, it is unlikely that Pn with substituents at the R2 position (attached to a phosphonate oxygen) would be easily accommodated. Indeed, previous data show that Pn compounds with alkyl groups at R2 (such as nerve gases & their analogs) have only millimolar Kd binding to EcPhnD (Table 2)21. Additional interactions are observed at the other end of 2AEP where its positively charged amino group interacts with Glu177 and Asp205 (Fig. 1B). Five ordered water molecules are observed filling the remainder of the binding cavity past the amino group of 2AEP, suggesting that phosphonate compounds with a longer R1 group could likely be accommodated in the binding pocket (supplemental Fig. S2). Previous work indeed showed that phosphonate compounds with larger, chemically diverse R1 moieties were bound by EcPhnD, some at high affinity (Table 2)21. Sequence alignment of EcPhnD with bacterial orthologs shows that the residues coordinating the phosphonate oxygens in our structure are highly conserved, but that Glu177 and Asp205 are not conserved (supplemental Fig. S3). This likely reflects the diversity of R1 side-chains of environmental phosphonates recognized by this family of binding proteins. Interestingly, Agrobacterium radiobacter was the only species of a panel of phosphonate-utilizing bacteria isolated from water treatment sludge that was able to grow on phosphinic acids (containing two carbon-phosphorus bonds, e.g. dimethylphospninic acid, (CH3)2PO2H) as a sole phosphorus source26. The PhnD ortholog from Agrobacterium radiobacter has proline residues substituted for Y47 and H157 (supplemental Fig. S3) observed to coordinate one of the phosphonate oxygens in our structure of EcPhnD (Fig. 1B). It seems possible that making these residues smaller and hydrophobic may allow accomodation of the second R group of phosphinic acids. These sequence features are conserved in a smaller group of PhnD orthologs; it would be interesting to examine whether other species in this group can utilize phospninic acids and to what extent PhnD dictates substrate specificity of the carbon-phosphorus lyase system.

FIGURE 1. Binding of 2AEP to EcPhnD.

A, ITC measurement of 2AEP binding to EcPhnD, following denaturing, washing, and refolding. Binding parameters calculated from the best fit binding model are inset. B, The phosphonate-binding site of EcPhnD with 2AEP bound. Selected portions of EcPhnD are displayed as sticks with tan color carbons. 2AEP is shown as ball-and-stick with white carbons. A portion of the 2Fo−Fc electron density omit map for 2AEP contoured at 2σ is shown as grey mesh. C, The solvent accessible surface of EcPhnD is shown with the front portion cut away to show the buried ligand binding pocket containing 2AEP (ball-and-stick).

Table 1.

X-ray data collection and refinement statistics.

| EcPhnD (PDB 3P7I) | Se-Met EcPhnD Se-peak | Se-Met EcPhnD inflection | Se-Met EcPhnD remote | Se-Met EcPhnD (PDB 3QK6) | Se-Met EcPhnD (PDB 3QUJ) | EcPhnD H157A (PDB 3S4U) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand added/ligand bound | 2AEP/2AEP | 2AEP/2AEP | 2AEP/2AEP | 2AEP/2AEP | none/unknown | none/unknown | none/none |

| Data collection | |||||||

| Space group | P21212 | P21 | P21 | P21 | C2 | P21 | P42212 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | |||||||

| a | 76.09 | 83.82 | 83.82 | 83.82 | 145.74 | 79.77 | 103.73 |

| b | 82.44 | 69.51 | 69.51 | 69.51 | 82.98 | 64.40 | 103.73 |

| c | 54.67 | 108.60 | 108.60 | 108.60 | 66.14 | 107.69 | 58.42 |

| β (degrees) | 90.00 | 94.14 | 94.14 | 94.14 | 103.20 | 93.52 | 90.00 |

| Beamline | APS 31-ID | APS 23-ID | APS 23-ID | APS 23-ID | APS 31-ID | APS 31-ID | APS 31-ID |

| Wavelength(Å) | 0.9793 | 0.97947 | 0.9796 | 0.95371 | 0.97929 | 0.97929 | 0.97929 |

| Resolution range (Å)a | 45.6 – 1.71 (1.8 – 1.71) | 50 – 2.5 (2.59 – 2.5) | 50 – 2.5 (2.59 – 2.5) | 50 – 2.5 (2.59 – 2.5) | 43.0 – 2.4 (2.53 – 2.4) | 28.9 – 2.2 (2.32 – 2.2) | 20 – 3.3 (3.48 – 3.3) |

| Total reflections | 401,252 | 715,199 | 659,059 | 795,397 | 125,600 | 314,573 | 124,059 |

| Unique reflections | 37,647 | 74,233 | 74,707 | 70,348 | 28,305 | 55,007 | 5,123 |

| Completeness (%)a | 99.7 (98.6) | 88.9 (63.3) | 89.7 (67.5) | 85.5 (57.1) | 94.3 (93.0) | 99.0 (98.6) | 99.5 (99.7) |

| I/σa | 9.8 (4.9) | 13.6 (3.3) | 20.6 (5.9) | 17.9 (4.6) | 9.4 (2.5) | 5.0 (2.9) | 17.9 (5.2) |

| Rsym (%)a,b | 10.2 (50.8) | 5.7 (20.1) | 5.4 (16.3) | 5.4 (19.6) | 8.8 (45.3) | 20.1 (41.9) | 17.8 (56.7) |

| Phasing | |||||||

| Number of Se sites/asu | 24 | ||||||

| Resolution range (Å) | 48.5 – 2.5 | ||||||

| Figure of Merit | 0.69 | ||||||

| Refinement | |||||||

| Rwork / Rfree (%)c | 22.3/25.1 | 20.9/26.7 | 20.6/27.3 | 20.3/28.8 | |||

| Resolution range (Å) | 45.6 – 1.71 | 43.0 – 2.4 | 28.9 – 2.2 | 20 – 3.3 | |||

| Number of atoms (B factor) | |||||||

| protein (chain A) | 2,518 (14.9) | 2,372 (24.5) | 2,359 (18.6) | ||||

| protein (chain B) | 2,409 (25.2) | 2,386 (16.1) | |||||

| protein (chain C) | 2,241 (20.8) | ||||||

| protein (chain D) | 2,226 (23.0) | ||||||

| water | 143 (21.53) | 29 (24.9) | 204 (14.8) | ||||

| 2-AEP | 7 (17.22) | ||||||

| Glycerol | 18 (38.60) | ||||||

| UNL | 10 (31.3) | 20 (10.7) | |||||

| RMSD values | |||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.028 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.021 | |||

| Bond angles (°) | 2.16 | 1.67 | 1.63 | 1.89 | |||

| Ramachandran (%) | |||||||

| Favored/Disallowed | 97.7/0 | 96.7/0 | 96.4/0.4 | 82.0/2.7 | |||

| Molprobity | |||||||

| Clashscore (percentile) | 10.08 (67) | 10.62 (93) | 9.97 (89) | 50.56 (54) | |||

| Molprobity score (percentile) | 1.98 (58) | 2.32 (80) | 2.38 (61) | 3.80 (38) |

The number in parentheses is for the highest resolution shell.

Rsym = Σihkl|Ii(hkl) − <I(hkl)>|/Σhkl <I(hkl)>, where Ii(hkl) is the ith measured diffraction intensity and <I(hkl)> is the mean of the intensity for the miller index (hkl).

Rwork = Σhkl ||Fo(hkl)| − |Fc(hkl)||/Σhkl |Fo(hkl)|. Rfree = Rwork for 5% of reflections not included in refinement.

FIGURE 2. Overall structure of EcPhnD.

A, Representation of the primary structure of EcPhnD colored by structural domain. B, Cartoon representation of the crystal structure of EcPhnD bound to 2AEP colored by domain as in A. 2AEP is shown as ball-and-stick. C, Topology diagram of the EcPhnD structure, colored as in A and B. α-helices are represented as circles, β-strands as triangles. Darker shaded shapes represent secondary structure elements that are not part of the conserved type II PBP fold. D, E, Cartoon representations of the closed, 2AEP-bound (tan) and open (burgundy) structures of EcPhnD, superimposed on Lobe 1 (panel D) or on Lobe 2 (panel E). A two-headed arrow points to equivalent regions of the structures, illustrating the magnitude of conformational change.

Table 2.

Phosphonate affinities (Kd in μM) for PhnD-based biosensors.

| EcPhnD-Q267C:acrylodan21 | EcPhnD-K181C:IANBD | EcPhnD90-cpGFP.L1ADΔΔ.L297R,L301R | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2AEP | 0.005 | 0.5 ± 0.043 | 37 ± 7 |

| Ethylphosphonate (EP) | 0.3 | 33 ± 4 | 130 ± 57 |

| Methylphosphonate (MP) | 1 | 290 ± 30 | 2733 ± 766 |

| Glyphosate (GP) | 650 | 260 ± 20 | NM1 |

| Ethylmethylphosphonate (EMPA) | 800 | ND2 | NM |

| Isopropylmethylphosphonate (IMPA) | 2000 | NM | NM |

| Pinacolylmethylphosphonate (PMPA) | 7000 | ND | NM |

No measurable binding, > 5000 μM.

Not determined.

Kd values from this work are ± standard deviation for three replicates.

EcPhnD was expressed and screened for crystallization without the addition of any exogenous ligand in an attempt to determine a structure of the ligand-free form. However, when we solved the structure from crystals obtained using this protein, we observed a strong electron density peak for a ligand in the binding pocket. The electron density was strongest for a five-atom tetrahedral shape at exactly the position of the phosphonate group in the 2AEP-bound structure (supplemental Fig. S4), but the quality of the electron density did not allow unambiguous identification of the ligand. Given that this protein resulted from E. coli grown in chemically defined LeMaster media with glucose as the primary carbon source, and that E. coli is not known to synthesize any phosphonate compounds 27, we suspect that the observed electron density could result from binding and co-purification of a monophosphorylated metabolite. Like other PBPs, native EcPhnD has an N-terminal periplasmic targeting sequence and is normally exported to the bacterial periplasm. However, to maximize protein yield for crystallography we over-expressed EcPhnD in the cytoplasm, without the periplasmic targeting signal. Therefore, binding of monophosphorylated metabolites to EcPhnD is unlikely to be a relevant issue in vivo.

Overall structure of EcPhnD

Since our efforts to crystallize the unliganded form of EcPhnD were hindered by co-purification and co-crystallization with an unidentified ligand, we created a substitution in the phosphonate binding site of EcPhnD, H157A, designed to disrupt ligand binding. EcPhnD H157A crystallized in an open conformation, and we solved its structure to 3.3 Å resolution by molecular replacement (Table 1).

The overall structure of EcPhnD is qualitatively similar to other PBPs 9(Fig. 2A, B), with the ligand-binding site located near the center of mass of EcPhnD in a cleft formed between two lobes of mixed α/β structure (Fig. 2B). The topology is typical of a type II PBP 28, with the polypeptide chain crossing over twice between the lobes (Fig. 2C). Following the canonical type II PBP topology are an additional three α-helices at the C-terminus (α10–α12). α10 is a short helix that forms part of the N-terminal lobe. Helices α11 and α12 form a long, anti-parallel coiled-coil that spans 6 turns of helix and packs against both lobes of EcPhnD (Fig. 2B).

Superposition of the open, unliganded and closed, 2AEP-bound structures shows that the individual lobes of EcPhnD do not change substantially in structure but undergo a rotation by ~70° relative to each other about a hinge comprising the two inter-lobe linkers, residues A86-W94 and S199-D205 (Fig. 2D,E). Difference-distance matrix comparison 29 of the open and closed structures clearly delineates the two lobes of EcPhnD (supplemental Fig. S5), while a Cα dihedral-difference analysis 30 shows the local backbone distortion at the inter-domain hinges (supplemental Fig. S6). The C-terminal coiled coil helices remain stationary relative to Lobe 1 (containing the amino terminus of EcPhnD), but make new interactions with Lobe 2 (helix α5) (Fig. 2D, E) upon 2AEP binding.

Structural comparison with other proteins

EcPhnD has very low sequence identity with paralogous PBPs with characterized specificity for other ligands, as is common for members of this protein superfamily 8; 31. A protein BLAST search with the EcPhnD sequence turns up the aliphatic sulfonate-binding protein family as the most similar non-phosphonate-binding group, but with expect values of ~1 or greater (suggesting that >1 match is expected by chance) and sequence identities of less than 20% (supplemental Fig. S7). Structural comparison of EcPhnD with other proteins using DALI 32 and SSM 33 revealed that transferrin-family proteins are structurally most similar to EcPhnD, although the RMSD is 3.4 Å or greater for aligning at least 80% of the alpha carbons (supplemental Fig. S8).

Recently, a crystal structure of PhnD from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PaPhnD) was deposited in the PDB (3N5L) by the Joint Center for Structural Genomics. PaPhnD and EcPhnD share 60% amino acid sequence identity, and the PaPhnD structure is very similar to the closed, 2AEP-bound structure reported here (supplemental Fig. S9), with an RMSD of 1.37 Å for comparing all 285 structurally equivalent Cα atoms. The PaPhnD structure has an unknown ligand modeled in the binding site that presumably co-purified with the protein. The unknown ligand has a tetrahedral-shaped substituent at exactly the position where we observe the phosphonate moiety of 2AEP, and the electron density feature has a similar size and shape to those that we observe for the unknown co-purified ligand in EcPhnD described above (supplemental Fig. S4). The largest structural variation between PaPhnD and EcPhnD is observed at the two C-terminal α-helices (supplemental Fig. S9). When the C-terminal α-helices are excluded from the structural alignment the two proteins superimpose with an RMSD of 0.57 Å for the remaining 231 Cα atoms.

Oligomeric state of EcPhnD

When purified by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), EcPhnD elutes as a single peak at a volume that corresponds to an estimated solution molecular weight intermediate between the monomer (36 kD) and dimer (72 kD) molecular weights calculated from the amino acid sequence (Fig. 3A). Injecting a higher concentration of EcPhnD resulted in a slightly earlier elution, suggesting the possibility of a rapid monomer-dimer equilibrium in solution.

FIGURE 3. Oligomeric state of EcPhnD.

A, SEC chromatograms of EcPhnD and C-terminal truncations. A calibration curve produced using protein standards is inset. Molecular weights estimated from each peak elution volume are shown as color coded dots and labels superimposed on the inset calibration curve. Theoretical molecular weights of each species are given in parentheses. B, Cartoon representation of the dimerization interface between two EcPhnD molecules (colored tan and blue). Selected side-chains participating in the dimerization interface are shown as sticks. 2AEP is shown as ball-and-stick. M304 of the tan molecule is labeled to highlight the site of the smallest truncation that disrupted dimerization.

In the crystal structures of EcPhnD presented here, we repeatedly observe a dimer (Fig. 3B). In four distinct crystal forms including the apo H157A EcPhnD structure, we observe five crystallographically unique EcPhnD dimers that all exhibit the same dimerization interface. In the closed, ligand-bound structures, 38 residues from each monomer participate in the interaction and 1665 Å2 of the solvent accessible surface area of each monomer (11% of the total surface area of each monomer) is buried at this interface. Dimerization is mediated exclusively by the two C-terminal coiled-coil alpha helices and a poorly structured stretch of nine amino acids at the extreme C-terminus that interacts with the coiled-coil of the other monomer (Fig. 3B). This small C-terminal region appears to be flexible since it is disordered in several of the crystallographically unique EcPhnD molecules.

Although the vast majority of PBPs are monomeric, three have been reported to be oligomeric: the α-keto acid-binding protein TakP from Rhodobacter sphaeroides 34, the iron transport protein FitE from E. coli 35, and TM0322 36, a PBP homologous to TRAP family proteins 37. Although C-terminal alpha helices play important roles in the dimerization of FitE and TakP, the conformations of the C-terminal helices, the interaction surfaces of the two monomers, the relative monomer orientations, and the amino acid sequences of the C-terminal regions are completely different from each other and from EcPhnD. A sequence alignment of EcPhnD with orthologous bacterial proteins clearly illustrates that sequence conservation within the C-terminal helices is significantly lower than for the rest of the protein (supplemental Fig. S3), suggesting that dimerization via these helices is not an evolutionarily conserved phenomenon. PaPhnD, which shares 60% overall sequence identity with EcPhnD but only 31% sequence identity within the C-terminal helices, crystallized as a monomer. The physiological role of PBP dimerization is not well understood 37.

Since the dimerization of EcPhnD is mediated exclusively by the C-terminus of the protein, we introduced stop codons by site-directed mutagenesis to remove different amounts from the C-terminus. Truncations at positions 298 and 304, at or near the end of helix α12, resulted in soluble, functional protein (supplemental Figs. S10, S11). Both the N298Δ and M304Δ truncations showed an elution profile suggestive of a monomer even at high concentrations by SEC (Fig. 3A), illustrating that removal of just the C-terminal nine poorly structured amino acids is sufficient to disrupt dimerization (Fig. 3B) in solution. Truncation at position 251, which removes the two C-terminal α-helices, α11 and α12, resulted in a protein that was insoluble when expressed in E. coli (supplemental Fig. S10).

Improvement of EcPhnD-based exogenous-fluorophore phosphonate sensors

Previous attempts have been made to construct a fluorescent biosensor from EcPhnD by introducing cysteines via site-directed mutagenesis for covalent conjugation of fluorescent reporter dyes 21. In that work, positions for mutagenesis to introduce cysteines were chosen based on a threading model constructed using the structure of the E. coli sulfate binding protein (SBP; PDB 1SBP), which has low (13%) sequence identity with EcPhnD. The structure of EcPhnD presented here illustrates that there are substantial differences when compared with that of SBP (supplemental Fig. S12). The RMSD for the best-fit superposition of EcPhnD and SBP was 3.8 Å when comparing the 232 (of 309) Cα positions that share any structural similarity. Indeed, when the positions of the six cysteine-containing variants previously used to create fluorescent biosensors 21 are mapped onto the superimposed structures of EcPhnD and SBP, there is an average difference of 27 Å between each position on the SBP-based threading model and the experimentally-determined EcPhnD structure (supplemental Fig. S12).

To create an improved generation of exogenous fluorophore-based EcPhnD sensors, the experimentally determined EcPhnD-2AEP structure was used to select cysteine positions for screening fluorescence changes when coupled to the environment-sensitive fluorophore IANBD. Thirty-one positions were selected by identifying the most surface-exposed residues that are within 20 Å of the bound 2AEP but do not make direct contact with it in our 2AEP-bound EcPhnD structure (supplemental Fig. S13A). These criteria were chosen to identify residues that were likely to be conformationally coupled with binding events (distance to binding site) and both amenable to amino acid substitution and available for labeling as cysteines (solvent exposure). The cysteine-containing EcPhnD variants were screened using a rapid, cell- and cloning-free workflow (Fig. 4A, Experimental Procedures), and two sites with large fluorescence signal changes in response to 2AEP were discovered: Q17C (increase) and K181C (decrease). These two variants were cloned, expressed, purified, and characterized by titration with 2AEP after IANBD conjugation (Fig. 4B,C): EcPhnD-Q17C:IANBD was found to have a ΔF/F0 of 1.2±0.1 and a Kd of 11±5 nM, and EcPhnD-K181C:IANBD a ΔF/F0 of −0.72±0.01 and a Kd of 540±40 nM (mean ± SEM; n = 3). The lower affinity of EcPhnD-K181C:IANBD for 2AEP may be a result of possible interactions between the conjugated dye and the phosphonate ligand given the close proximity of position 181 to the binding pocket.

FIGURE 4. In vitro screening for exogenous-fluorophore phosphonate sensors.

A, Change in fluorescence from IANBD-conjugated EcPhnD single cysteine variants following addition of either buffer control (black bars) or 1 mM 2AEP (red bars). Fluorescence titrations of purified, IANBD-conjugated EcPhnD variants Q17C (B) and K181C (C) with 2AEP were then carried out. Curve fit was a single-site binding isotherm [y=((Fmax−Fo)/(1+(Kd/x)))+Fo]. Error bars show standard deviation (n = 3).

These IANBD-conjugate sensors were designed based only on the closed, ligand-bound structure of EcPhnD which was obtained first. A retrospective analysis in light of the open, unliganded EcPhnD structure is now possible. In our EcPhnD-2AEP structure, Gln17 is located on Lobe 1 close to the interface between the two lobes (supplemental Fig. S14A), such that potential stable interactions of the conjugated IANBD with Lobe 2 might only be accessible in the closed, ligand-bound conformation (for an analysis of such interactions in a related sensor, from E. coli maltose-binding protein, see 38). In the ligand-free state, our open structure shows a pocket on the surface of the protein near position Lys181 that could accommodate at least part of the NBD given the linker length from the coupled Cys181 (supplemental Fig. S14B). This could potentially immobilize the IANBD and lead to a high fluorescence in the apo state; in the bound state the fluor could be more solvent-exposed due to exclusion of this pocket at the interface between lobes. The decrease in affinity of the labeled Lys181Cys EcPhnD is potentially caused by steric hindrance of the completely closed conformation by the coupled NBD.

For rational design of environmentally sensitive dye-conjugate sensors, it may be most informative to compare the predicted solvent accesibility of the dye between the two conformational states and target positions with the largest differences in solvent accessibility, thereby maximizing the potential fluorescence signal change. A plot of the change in percent solvent acessible surface area (Δ%SASA) calculated at each amino acid position between open and closed EcPhnD shows twelve positions that change their % solvent accessibility by more than 30% (supplemental Fig. S13B). With the exception of position 181, which led to a sensor with a large fluorescence decrease, none of these positions was selected for cysteine introduction and dye conjugation according to the criteria outlined above. Although several of these positions are nearby the bound ligand (supplemental Fig. S13A) and were specifically not chosen to avoid interference with ligand binding, future work could target these sites in hopes of even larger fluorescence changes from conjugated dyes.

Engineering of genetically encoded phosphonate sensors

In addition to creating a biosensor by chemical modification of EcPhnD (primarily useful for in vitro applications), we sought to create a genetically encoded sensor, which could be useful for studying in vivo phosphonate transport and metabolism. Genetically encoded fluorescent sensors typically contain either a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) donor and acceptor pair (for review, see 23), or a single, circularly permuted fluorescent protein (FP) (the canonical sensor in this family is the GCaMP calcium indicator 39). In addition to several practical advantages, the recent structure determination of the apo and Ca2+-bound forms of GCaMP 40; 41 has facilitated design and optimization of single-FP sensors.

To create a genetically encoded phosphonate sensor, we inserted cpGFP at positions 87, 90, 142, and 241 within EcPhnD (supplemental Fig. S15) using sequence and structural analogy with our recently published EcMBP-cpGFP sensors for maltose24. Insertion of cpGFP at positions 142 and 147 led to dramatically decreased affinity for 2AEP by ITC analysis (supplemental Fig. S16), suggesting that these modifications disrupted proper EcPhnD folding or function. Extensive mutagenic screening of the inter-domain linkers of EcPhnD142-cpGFP resulted in no variants with ΔF/F0 >0.3 (supplemental Fig. S17). By ITC, EcPhnD87-cpGFP shows high affinity for 2AEP, large ΔH, and the two-site titration curve seen for the wild-type protein (supplemental Fig. S16). A screen of linker variants of EcPhnD87-cpGFP resulted in some variants with moderate fluorescence changes (ΔF/F0 as low as −0.5 and as high as +0.4) (supplemental Fig. S17).

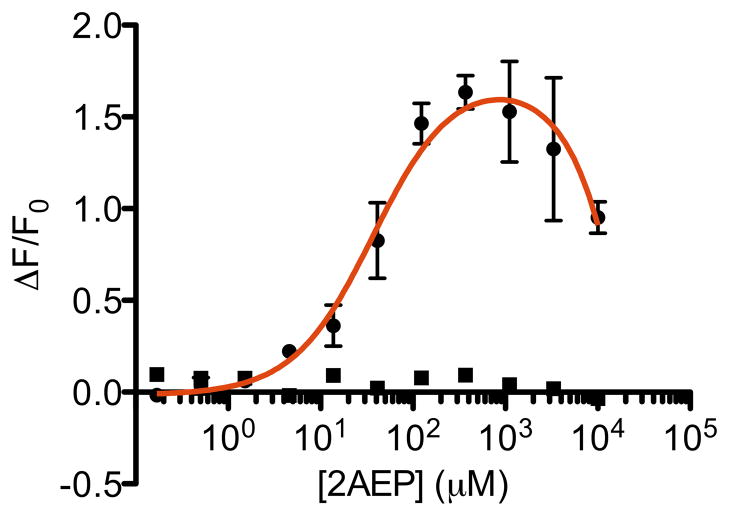

Since it was possible that EcPhnD residue 87 was on the edge of the inter-lobe hinge, we chose to explore another cpGFP insertion point in the vicinity of the region we expected to undergo significant local backbone changes, EcPhnD90-cpGFP. A screen of linker mutants of EcPhnD90-cpGFP, including deletions and insertions of residues, yielded variants with ΔF/F0 near 1 in E. coli lysate (supplemental Fig. S17). One variant had an AlaAsp EcPhnD-cpGFP linker (L1AD), and a ΔF/F0 of 1.2 when purified and titrated with 2AEP. This variant included a linker with two deleted residues, effectively making the insertion point of cpGFP occur after residue D88, and then skipping to residue P91 at the cpGFP-EcPhnD linker (supplemental Fig. S18). It is with this insertion site/linker combination, EcPhnD90-cpGFP.L1ADΔΔ, that we performed subsequent binding assays. Additional substitutions L297R and L301R, made in the context of EcPhnD90-cpGFP.L1ADΔΔ to attempt disruption of the observed dimer, led to ΔF/F0 increases of 1.6 in response to 2AEP (Fig. 5). We observed a fluorescence decrease at very high [2AEP] (> 1 mM), which we attribute to non-specific quenching of the cpGFP fluorescence. Fluorescent reponses to other phosphonate compounds with this sensor are lower, and some have more complicated binding patterns (supplemental Fig. 19). The affinity of this sensor for phosphonates is lower than that of the IANBD-conjugated EcPhnD sensors reported here, as well as previously reported dye-conjugate sensors (Table 2). It is possible that the insertion of cpGFP into EcPhnD introduces steric impediments to adopting the closed, ligand-bound conformation, thereby lowering the affinity for ligands.

FIGURE 5. A genetically encoded phosphonate sensor.

A, Fluorescence titration of the best genetically encoded phosphonate sensor, EcPhnD90-cpGFP.L1ADΔΔ.L297R,L301R, with 2AEP. Titration of a cpGFP fusion with a glucose binding protein that has no affinity for phosphonates is shown in square symbols as a negative control. We attribute the marked decrease of fluorescence at high concentrations of 2AEP in the sensor titration to fluorescence quenching. Curve fit was a single-site binding isotherm plus a linear component to account for quenching. Error bars show standard deviation (n = 3).

When we later solved the structure of the open, ligand-free form of the protein (with a substitution in the Pn binding site, H157A), we were able to perform a retrospective ΔCα-dihedral analysis (measuring the difference in dihedral angle calculated using four consecutive Cα positions between the closed, liganded and open, unliganded structures) to improve our understanding of why only the insertions of cpGFP at positions 87 and 90 in cpGFP led to viable sensors. The region of greatest Cα dihedral change is the group of residues from 88–90 (Supplemental Fig. S6), just one amino acid away from the site we had chosen by functional homology. The retrospective Cα dihedral analysis also serves as a reasonable explanation for why insertion of cpGFP at residues 142 in EcPhnD did not result in a sensor – the ΔCα dihedral for that segment of the protein is nearly zero.

We anticipate that our development of a genetically encoded phosphonate sensor (EcPhnD90-cpGFP.L1ADΔΔ.L297R,L301R) will facilitate future screening of high-affinity and -specificity sensors for phosphonate compounds of commercial or environmental interest, such as glyphosate (Roundup®), or nerve gasses and their breakdown products. This could, for example, allow visualization of glyphosate uptake and processing in plants. Libraries of mutations of the phosphonate binding site (defined by the crystal structure) could be screened in E. coli lysate for fluorescence response to lower concentrations of these compounds, similar to the methodology used here to screen linker variants for response to 2AEP.

Binding specificity of phosphonate sensors

The EcPhnD K181C:IANBD dye-conjugate and the EcPhnD90-cpGFP.L1ADΔΔ.L297R,L301R genetically encoded sensors were further titrated with a variety of other phosphonate compounds (supplemental Figs. S19 and S20, Table 2). Although the sensors described here bind phosphonates with overall lower affinity than previous sensors and the wild-type protein (21 and Fig. 1A), likely due to steric effects as discussed earlier, some clear trends in affinity are obvious. Each sensor recognizes 2AEP with the highest affinity, followed by ethylphosphonate and then methylphosphonate. This seems reasonable since removal of the positively charged amine of 2AEP to generate ethylphosphonate takes away an ionic interaction. Further removal of a methylene to produce methylphosphonate reduces the Van der Waals’ interactions between the phosphonate alkyl chain and EcPhnD. None of the sensors show high-affinity binding (<500 μM) to phosphonates with a substituent at one of the phosphonate oxygens (EMPA, IMPA, PMPA), which makes sense given that the phosphonate oxygens are saturated with protein interactions in our 2AEP-bound structure (Fig 1B).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Crystallization and structure determination

A synthetic E. coli codon-optimized gene encoding the EcPhnD protein (UniProt ID Q0T9T8), lacking the 26-amino acid N-terminal periplasmic export signal but encoding a hexa-histidine (6xHis) affinity tag at the N-terminus (MHHHHHHGSEEQEK…) was cloned into the pRSETa plasmid (Invitrogen). Protein expression was carried out using E. coli strain BL21(DE3) grown in Luria-Bertani medium for native EcPhnD, or using the T7 Express Crystal strain (NEB) grown in LeMaster minimal medium 43 supplemented with selenomethionine (SeMet) for SeMet-labeled EcPhnD. Cultures were grown in shaker flasks at 37°C, and protein expression was induced with 1mM IPTG at OD600nm = 0.8. Three hours after IPTG induction, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 12,000g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Pellets were stored at −80°C until protein purification. E. coli cells were lysed by sonication after resuspension in 20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0 (buffer 1), and the insoluble fraction was removed by centrifugation at 25,000g for 30 min at 4°C. Protein purification was achieved from the soluble lysate first by Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography (Qiagen) and then by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) on a Superdex 200 column (GE Biosciences) in buffer 1. EcPhnD produced by this procedure was >95% pure as judged by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE and was concentrated to 10–30 mg/mL in TBS for crystallization. 2AEP was added from a concentrated stock in buffer 1 to give a 5-fold molar excess over EcPhnD.

EcPhnD was crystallized at 20°C by sitting-drop vapor diffusion using commercially available sparse-matrix screens (Hampton Research); crystallization details for each crystal form described are provided in supplemental Table S1. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source, beamlines 23-ID and 31-ID. Diffraction data were processed using HKL2000 44 or d*Trek 45 (Table 1). Attempts at structure solution using molecular replacement with other PBPs or domains thereof using the initial native dataset failed. Therefore, a three-wavelength multiple anomalous dispersion (MAD) dataset was collected from a crystal of SeMet-substituted EcPhnD (P21 crystal form, Table 1). Solve 46 and Resolve 47 implemented in the software package Phenix 48 were used to locate 24 Se sites, calculate experimental phases, and modify the resulting electron density map by solvent flattening and non-crystallographic symmetry averaging. The density-modified map at 2.5 Å resolution was readily interpretable, and the monomer with the best quality electron density was traced manually using Coot 49 to produce an initial EcPhnD model. This model was used as a molecular replacement search model into the higher-resolution native dataset (P21212 crystal form, Table 1) using Phaser 50. Iterative cycles of refinement in Refmac 51, including TLS refinement using groups suggested by TLSMD analysis 52; 53, and rebuilding in Coot led to the EcPhnD-2AEP model reported in Table 1. Other structures of EcPhnD described here were solved by molecular replacement with the EcPhnD-2AEP model or fragments thereof and refined as described above. Figures of protein structure were prepared using PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org/). Protein interfaces were analyzed with the PISA software package 54. MolProbity 55 and Ramachandran analysis of the final structural models is given in Table 1.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Calorimetric titrations of 2AEP into solutions of EcPhnD proteins were carried out using a VP-ITC instrument (MicroCal Corp., Northampton, MA). 2AEP and purified EcPhnD were prepared in Tris-Buffered Saline (TBS: 20 mM Tris, 138 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). 100 μM 2AEP was titrated into 10 μM EcPhnD at 25°C. Data were analyzed using VP-ITC software scripts within Origin (OriginLab), and binding parameters were determined by nonlinear least-squares fitting of the baseline-corrected titration curves.

In vitro screen of exogenous-fluorophore sensors

An open reading frame (T7 promoter and ribosome-binding site 5′; T7 terminator 3′) encoding an N-terminally 6xHis-tagged and C-terminally FLAG epitope-tagged EcPhnD was designed and synthesized using the techniques previously described in 56 (supplemental Fig. S21). 31 variants of this EcPhnD sequence were synthesized, each with a single amino acid replaced with cysteine; no cysteines are present in the natitive sequence of EcPhnD (supplemental Fig. S18). These open reading frames (ORFs) were then re-amplified with 5′ biotinylated primers to generate biotinylated, linear DNA to drive in vitro transcription/translation reactions (ivTTs). In addition to the inclusion of a no-DNA ivTT reaction and the wild-type (no cysteine) EcPhnD as negative controls, an ORF containing an S131C variant Thermotoga maritima glucose-binding protein (TmGBP) 57 (titrated with glucose) was included as a positive control. E. coli lysate and ivTT reaction buffer were prepared as described in the Supplemental Information of 58. Each of the ORFs was expressed in 100 μL ivTTs. The 100 μL reaction was incubated in a 2mL microtube at 30°C for 8 hours while being shaken at 500rpm in a shaker-equipped microtube heat block (Thermomixer R, Eppendorf). The 2mL tubes were left open and covered with gas-permeable tape (AirPore, Qiagen). We found that the use of a flat-bottom 2mL tube with a 100 μL reaction permitted the reaction to be mixed gently with lower-speed shaking.

50 μL of a 50% v/v solution of EZview Red HIS-select resin (Sigma-Aldrich) in 20 mM MOPS, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 (MBS) was added to each reaction at 4°C, and shaking was resumed at 500rpm at this temperature for one hour to permit binding of the 6xHis-tagged protein to the resin. After one hour these mixtures were aspirated from the 2mL tubes and dispensed into wells in a clear, flat-bottomed 96-well microplate and held at a 45° angle on a microplate stand. This and subsequent steps were performed at room temperature. The hold at a 45° angle caused the resin to partially settle against one side of the microplate, facilitating the removal of the buffer upon returning the microplate to resting flat on the bench. In this manner the resin was washed twice with MBS and then reacted with 50 μL of a 200 μM solution of IANBD (Invitrogen) in MBS for one hour at room temperature on a microplate shaker at 500 rpm. Following this reaction the resin was washed three times with 200 μL MBS, resuspended in 200 μL MBS, and the contents of each well were divided equally into two wells of a black, flat-bottomed 96-well plate (Greiner Fluotrac 200) for assay.

The black microplate containing triplicate samples of each EcPhnD variant was shaken at 500rpm and then rested to resuspend and then settle the resin. Fluorescence intensities were read from each well in a FluoDia T70 plate reader (PTI) with 475BP20 and 540BP20 filters (Omega Optical) for excitation and emission, respectively. This cycle was performed three times, after which the resin was settled at a 45° angle, the MBS drawn off, and either MBS or MBS plus 1mM glucose (in the case of the TmGBP positive control) or 1mM 2AEP (to all others) was added to the two wells. The triplicate shake, settle, read cycle was then performed again to obtain ΔF/F0 (defined by (F0-Fsat)/F0; F0 = baseline fluorescence, Fsat = saturated fluorescence) values for each IANBD-conjugated EcPhnD variant against buffer or analyte.

Two IANBD-conjugated variants that displayed a large fluorescent signal change upon 2AEP binding were identified, and subsequently cloned into pET21a using restriction digestion (5′ NdeI and 3′ XhoI). Clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Protein expression was carried out using E. coli strain BL21(DE3) grown in Superior Broth (AthenaES). Cultures were grown in shaker flasks at 37°C until an OD600nm value of 0.8 was reached, at which point the cultures were moved to an 18°C shaker incubator and induced with 1mM IPTG. Induction was permitted to continue overnight at this temperature. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 12,000g for 30 minutes and lysed by sonication after resuspension in TBS. Lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 30,000g for 30 min. Protein purification was achieved by Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography, subsequent extensive dialysis (five 200x exchanges over at least 72 hours) against 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, and size exclusion chromatography on an S75 column (GE). The purified proteins were labeled by reaction with a 5-fold molar excess of IANBD iodoacetamide (Invitrogen) for one hour at room temperature, followed by removal of unreacted fluorophore by buffer exchange on a 10DG column (Bio-Rad).

The purified, labeled proteins were titrated against various phosphonate molecules by adding equal parts of a 2 nM protein stock solution to a series of serial ligand dilutions across rows of a 96-well black fluorescence microplate (Greiner Fluotrac 200). The plates were shaken for 30 seconds, allowed to equilibrate for at least 5 minutes, then read on a Tecan Safire2 plate reader (λex=475nm, bandpass=12nm; λem=540nm, bandpass=12nm).

Construction of a genetically encoded phosphonate sensor

The EcPhnD-cpGFP insertion variants were constructed by overlap PCR using the synthetic EcPhnD sequence and the cpGFP146 variant from GCaMP2 59. Detailed sequences are provided in supplemental Fig. S18. The linker regions were mutated by single-stranded template mutagenesis 60 using the primers listed in supplemental Fig. S22, transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3), and plated on 24 cm × 24 cm agar plates with 60 μg/mL ampicillin. Individual colonies were picked with the aid of a QPix2XT colony-picking robot (Genetix) into 96-well plates filled with 800 μL ZYM-5052 auto-induction media 61 and 100 μg/mL ampicillin, and grown with rapid (900 rpm) shaking overnight at 30°C. 100 μL cell culture was removed and archived. The remaining cells were harvested by centrifugation (3,000g for 10 min.) and frozen. Protein was extracted by freeze-thaw lysis and rapid shaking in 800 μL TBS. Crude lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 4000g for 30 minutes. 100 μL clarified lysate was transferred to flat-bottom black 96-well plates (Greiner) for fluorescence measurement. Fluorescence was assayed in a Tecan Safire2 plate-reading fluorimeter with stacker. Excitation and emission wavelengths were 485 nm and 515 nm respectively, with a 5 nm bandpass. Gain was 100V. Fluorescence was measured again after addition of 10 μL 1 mM 2AEP (final 2AEP concentration 100 μM). After calculation of ΔF/F0 ((Fsat−F0)/F0), interesting candidates were streaked on agar plates from archived aliquots, grown for plasmid DNA isolation, and sequenced. Fluorescence titration data were fit to a single binding site model with a linear component to account for quenching; for a negative control to estimate non-specific quenching of cpGFP fluorescence we used a cpGFP fusion with a glucose binding protein that has no affinity for phosphonates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to members of the Looger lab and Schreiter lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the University of Puerto Rico - Río Piedras Campus. I.A. thanks NIH-RISE (R25GM61151) for research support. Work performed at UT Austin was funded by the Department of Homeland Security (HSHQDC-08-C-00072), Welch Foundation (F-1654), and the National Security Science and Engineering Faculty Fellowship (FA9550-10-1-0169). The published material represents the position of the author(s) and not necessarily that of the sponsors. Use of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the Lilly Research Laboratories Collaborative Access Team (LRL-CAT) beamline at Sector 31 of the Advanced Photon Source was provided by Eli Lilly Company, which operates the facility. GM/CA CAT has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (Y1-CO-1020) and the National Institute of General Medical Science (Y1-GM-1104).

The abbreviations used are

- EcPhnD

E. coli PhnD

- 2AEP

2-aminoethylphosphonate

- cpGFP

circularly permuted green fluorescent protein

- IANBD

N,N′-dimethyl-N-(iodoacetyl)-N′-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-YL)-ethylenediamine

- Pn

phosphonate

- ABC

ATP-binding casette

- PBP

periplasmic binding protein

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- MAD

multi-wavelength anomolous dispersion

- SEC

size-exclusion chromatography

- SBP

sulfate binding protein

- SeMet

selenomethionine

- Tris

tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- MOPS

3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

- MBS

MOPS-buffered saline

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The atomic coordinates for the crystal structures presented here are available from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Databank (http://www.pdb.org) under PDB # 3P7I for wild-type EcPhnD in complex with 2AEP, under PDB # 3QUJ and 3QK6 for SeMet-substituted EcPhnD in the closed conformation bound to an unknown ligand, and under PDB # 3S4U for EcPhnD variant H157A in the open conformation.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wanner BL. In: Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology 2nd edit. Neidhardt FC, Curtiss R III, Ingraham JL, Lin ECC, Low KB, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger HE, editors. ASM Press; Washington, D.C.: 1996. pp. 1357–1381. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metcalf WW, Wanner BL. Mutational analysis of an Escherichia coli fourteen-gene operon for phosphonate degradation, using TnphoA’ elements. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3430–42. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3430-3442.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebhard S, Cook GM. Differential regulation of high-affinity phosphate transport systems of Mycobacterium smegmatis: identification of PhnF, a repressor of the phnDCE operon. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1335–43. doi: 10.1128/JB.01764-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jochimsen B, Lolle S, McSorley FR, Nabi M, Stougaard J, Zechel DL, Hove-Jensen B. Five phosphonate operon gene products as components of a multi-subunit complex of the carbon-phosphorus lyase pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104922108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hove-Jensen B, Rosenkrantz TJ, Haldimann A, Wanner BL. Escherichia coli phnN, encoding ribose 1,5-bisphosphokinase activity (phosphoribosyl diphosphate forming): dual role in phosphonate degradation and NAD biosynthesis pathways. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2793–801. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.9.2793-2801.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Errey JC, Blanchard JS. Functional annotation and kinetic characterization of PhnO from Salmonella enterica. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3033–9. doi: 10.1021/bi052297p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hove-Jensen B, McSorley FR, Zechel DL. Physiological role of phnP-specified phosphoribosyl cyclic phosphodiesterase in catabolism of organophosphonic acids by the carbon-phosphorus lyase pathway. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133:3617–24. doi: 10.1021/ja1102713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tam R, Saier MH., Jr Structural, functional, and evolutionary relationships among extracellular solute-binding receptors of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:320–46. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.320-346.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quiocho FA, Ledvina PS. Atomic structure and specificity of bacterial periplasmic receptors for active transport and chemotaxis: variation of common themes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharff AJ, Rodseth LE, Spurlino JC, Quiocho FA. Crystallographic evidence of a large ligand-induced hinge-twist motion between the two domains of the maltodextrin binding protein involved in active transport and chemotaxis. Biochemistry. 1992;31:10657–63. doi: 10.1021/bi00159a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quiocho FA. Atomic structures of periplasmic binding proteins and the high-affinity active transport systems in bacteria. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1990;326:341–51. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1990.0016. discussion 351–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abouhamad WN, Manson M, Gibson MM, Higgins CF. Peptide transport and chemotaxis in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: characterization of the dipeptide permease (Dpp) and the dipeptide-binding protein. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1035–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CY, Berish SA, Morse SA, Mietzner TA. The ferric iron-binding protein of pathogenic Neisseria spp. functions as a periplasmic transport protein in iron acquisition from human transferrin. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:311–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugiyama S, Matsuo Y, Maenaka K, Vassylyev DG, Matsushima M, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K, Morikawa K. The 1.8-A X-ray structure of the Escherichia coli PotD protein complexed with spermidine and the mechanism of polyamine binding. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1984–90. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karpowich NK, Huang HH, Smith PC, Hunt JF. Crystal structures of the BtuF periplasmic-binding protein for vitamin B12 suggest a functionally important reduction in protein mobility upon ligand binding. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8429–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212239200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campobasso N, Costello CA, Kinsland C, Begley TP, Ealick SE. Crystal structure of thiaminase-I from Bacillus thiaminolyticus at 2.0 A resolution. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15981–9. doi: 10.1021/bi981673l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis M, Chang G, Horton NC, Kercher MA, Pace HC, Schumacher MA, Brennan RG, Lu P. Crystal structure of the lactose operon repressor and its complexes with DNA and inducer. Science. 1996;271:1247–54. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5253.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogner A, Greenwood JR, Liljefors T, Lunn ML, Egebjerg J, Larsen IK, Gouaux E, Kastrup JS. Competitive antagonism of AMPA receptors by ligands of different classes: crystal structure of ATPO bound to the GluR2 ligand-binding core, in comparison with DNQX. J Med Chem. 2003;46:214–21. doi: 10.1021/jm020989v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murzin AG. Can homologous proteins evolve different enzymatic activities? Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:403–5. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nowack B. Environmental chemistry of phosphonates. Water research. 2003;37:2533–46. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(03)00079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rizk SS, Cuneo MJ, Hellinga HW. Identification of cognate ligands for the Escherichia coli phnD protein product and engineering of a reagentless fluorescent biosensor for phosphonates. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1745–51. doi: 10.1110/ps.062135206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dwyer MA, Hellinga HW. Periplasmic binding proteins: a versatile superfamily for protein engineering. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frommer WB, Davidson MW, Campbell RE. Genetically encoded biosensors based on engineered fluorescent proteins. Chemical Society reviews. 2009;38:2833–41. doi: 10.1039/b907749a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marvin JS, Schreiter ER, Echevarria IM, Looger LL. A Genetically Encoded, High-Signal-to-Noise Maltose Sensor. Proteins in press. 2011 doi: 10.1002/prot.23118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer AE, Qin Y, Park JG, McCombs JE. Design and application of genetically encoded biosensors. Trends in biotechnology. 2011;29:144–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wackett LP, Shames SL, Venditti CP, Walsh CT. Bacterial carbon-phosphorus lyase: products, rates, and regulation of phosphonic and phosphinic acid metabolism. Journal of bacteriology. 1987;169:710–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.710-717.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metcalf WW, van der Donk WA. Biosynthesis of phosphonic and phosphinic acid natural products. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:65–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.091707.100215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukami-Kobayashi K, Tateno Y, Nishikawa K. Domain dislocation: a change of core structure in periplasmic binding proteins in their evolutionary history. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:279–90. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards FM, Kundrot CE. Identification of structural motifs from protein coordinate data: secondary structure and first-level supersecondary structure. Proteins. 1988;3:71–84. doi: 10.1002/prot.340030202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flocco MM, Mowbray SL. C alpha-based torsion angles: a simple tool to analyze protein conformational changes. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2118–22. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berntsson RP, Smits SH, Schmitt L, Slotboom DJ, Poolman B. A structural classification of substrate-binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2606–17. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holm L, Rosenstrom P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W545–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2256–68. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904026460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonin S, Arnoux P, Pierru B, Lavergne J, Alonso B, Sabaty M, Pignol D. Crystal structures of an Extracytoplasmic Solute Receptor from a TRAP transporter in its open and closed forms reveal a helix-swapped dimer requiring a cation for alpha-keto acid binding. BMC Struct Biol. 2007;7:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi R, Proteau A, Wagner J, Cui Q, Purisima EO, Matte A, Cygler M. Trapping open and closed forms of FitE: a group III periplasmic binding protein. Proteins. 2009;75:598–609. doi: 10.1002/prot.22272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cuneo MJ, Changela A, Miklos AE, Beese LS, Krueger JK, Hellinga HW. Structural analysis of a periplasmic binding protein in the tripartite ATP-independent transporter family reveals a tetrameric assembly that may have a role in ligand transport. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32812–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803595200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mulligan C, Fischer M, Thomas GH. Tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporters in bacteria and archaea. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35:68–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dattelbaum JD, Looger LL, Benson DE, Sali KM, Thompson RB, Hellinga HW. Analysis of allosteric signal transduction mechanisms in an engineered fluorescent maltose biosensor. Protein science: a publication of the Protein Society. 2005;14:284–91. doi: 10.1110/ps.041146005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakai J, Ohkura M, Imoto K. A high signal-to-noise Ca(2+) probe composed of a single green fluorescent protein. Nature biotechnology. 2001;19:137–41. doi: 10.1038/84397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Q, Shui B, Kotlikoff MI, Sondermann H. Structural basis for calcium sensing by GCaMP2. Structure. 2008;16:1817–27. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akerboom J, Rivera JD, Guilbe MM, Malave EC, Hernandez HH, Tian L, Hires SA, Marvin JS, Looger LL, Schreiter ER. Crystal structures of the GCaMP calcium sensor reveal the mechanism of fluorescence signal change and aid rational design. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:6455–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807657200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guntas G, Ostermeier M. Creation of an allosteric enzyme by domain insertion. Journal of molecular biology. 2004;336:263–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LeMaster DM, Richards FM. 1H-15N heteronuclear NMR studies of Escherichia coli thioredoxin in samples isotopically labeled by residue type. Biochemistry. 1985;24:7263–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00346a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Otwinowski Z, Minor W, Carter Charles W., Jr . Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 276. Academic Press; 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode; pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pflugrath JW. The finer things in X-ray diffraction data collection. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:1718–25. doi: 10.1107/s090744499900935x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terwilliger TC, Berendzen J. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:849–61. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Terwilliger TC. Maximum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:965–72. doi: 10.1107/S0907444900005072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallog. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–55. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Painter J, Merritt EA. TLSMD web server for the generation of multi-group TLS models. J Appl Cryst. 2006;39:109–111. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:439–50. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cox JC, Lape J, Sayed MA, Hellinga HW. Protein fabrication automation. Protein Sci. 2007;16:379–90. doi: 10.1110/ps.062591607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tian Y, Cuneo MJ, Changela A, Hocker B, Beese LS, Hellinga HW. Structure-based design of robust glucose biosensors using a Thermotoga maritima periplasmic glucose-binding protein. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2240–50. doi: 10.1110/ps.072969407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allert M, Cox JC, Hellinga HW. Multifactorial determinants of protein expression in prokaryotic open reading frames. J Mol Biol. 2010;402:905–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tallini YN, Ohkura M, Choi BR, Ji G, Imoto K, Doran R, Lee J, Plan P, Wilson J, Xin HB, Sanbe A, Gulick J, Mathai J, Robbins J, Salama G, Nakai J, Kotlikoff MI. Imaging cellular signals in the heart in vivo: Cardiac expression of the high-signal Ca2+ indicator GCaMP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4753–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509378103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kunkel TA, Bebenek K, McClary J. Efficient site-directed mutagenesis using uracil-containing DNA. Methods in enzymology. 1991;204:125–39. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Studier FW. Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein expression and purification. 2005;41:207–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.