Significance

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder affecting approximately 1% of the world population. Mutations within genes encoding voltage-gated channels are the most frequently identified cause of monogenic epilepsies. Variable expressivity is a common feature of many epilepsies, suggesting that modifier genes make significant contributions to clinical phenotype. Here, we report an investigation of the molecular basis for strain-dependent seizure severity in the Scn2aQ54 epileptic mice. We show strain-dependent differences in pyramidal cell excitability correlate with divergent properties of voltage-gated sodium channels that could be explained by differences in calcium/calmodulin protein kinase II (CaMKII)-dependent modulation of neuronal sodium channels. These findings suggest that strain-dependent sodium channel modulation by CaMKII in Scn2aQ54 mice influences excitatory neuronal networks.

Keywords: epilepsy, voltage-gated sodium channel, CaMKII

Abstract

Monogenic epilepsies with wide-ranging clinical severity have been associated with mutations in voltage-gated sodium channel genes. In the Scn2aQ54 mouse model of epilepsy, a focal epilepsy phenotype is caused by transgenic expression of an engineered NaV1.2 mutation displaying enhanced persistent sodium current. Seizure frequency and other phenotypic features in Scn2aQ54 mice depend on genetic background. We investigated the neurophysiological and molecular correlates of strain-dependent epilepsy severity in this model. Scn2aQ54 mice on the C57BL/6J background (B6.Q54) exhibit a mild disorder, whereas animals intercrossed with SJL/J mice (F1.Q54) have a severe phenotype. Whole-cell recording revealed that hippocampal pyramidal neurons from B6.Q54 and F1.Q54 animals exhibit spontaneous action potentials, but F1.Q54 neurons exhibited higher firing frequency and greater evoked activity compared with B6.Q54 neurons. These findings correlated with larger persistent sodium current and depolarized inactivation in neurons from F1.Q54 animals. Because calcium/calmodulin protein kinase II (CaMKII) is known to modify persistent current and channel inactivation in the heart, we investigated CaMKII as a plausible modulator of neuronal sodium channels. CaMKII activity in hippocampal protein lysates exhibited a strain-dependence in Scn2aQ54 mice with higher activity in F1.Q54 animals. Heterologously expressed NaV1.2 channels exposed to activated CaMKII had enhanced persistent current and depolarized channel inactivation resembling the properties of F1.Q54 neuronal sodium channels. By contrast, inhibition of CaMKII attenuated persistent current, evoked a hyperpolarized channel inactivation, and suppressed neuronal excitability. We conclude that CaMKII-mediated modulation of neuronal sodium current impacts neuronal excitability in Scn2aQ54 mice and may represent a therapeutic target for the treatment of epilepsy.

Voltage-gated sodium channels are essential for the generation and propagation of action potentials in excitable cells (1). These proteins exist as heteromultimeric complexes formed by a large pore-forming α-subunit and one or more auxiliary β-subunits (2). Function of voltage-gated sodium channels is influenced by multiple intracellular factors including protein–protein interactions, channel phosphorylation, and intracellular calcium. The auxiliary β-subunits and a family of FGF homologous factors (FHF) have been shown to modulate trafficking and functional properties of voltage-gated sodium channels (3–5). Both PKA and PKC have been shown to modulate neuronal voltage-gated sodium current function (6, 7). Finally, intracellular calcium, calmodulin, and calcium/calmodulin protein kinase II (CaMKII) have been shown to have drastic effects on the cardiac sodium channel (8–10). Thus, differences in posttranslational modification of sodium channels may profoundly influence the physiology of excitable cells.

Mutations in genes encoding neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels (SCN1A, NaV1.1, and SCN2A, NaV1.2) have been associated with several types of human epilepsy, including genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+) and benign familial neonatal infantile seizures (BFNIS), and the more severe Dravet syndrome and early infantile epileptic encephalopathy type 11 (EIEE11) (2, 11). To date, more than 1,200 SCN1A mutations have been identified, making this gene the most frequently identified cause of monogenic epilepsy. Interestingly, variable expressivity is a common feature of monogenic epilepsy disorders, suggesting that genetic modifiers may contribute to clinical severity (12).

In Scn2aQ54 mice, transgenic expression of a gain-of-function sodium channel mutation results in epilepsy (13). Hippocampal pyramidal neurons isolated acutely from Scn2aQ54 mice exhibit enhanced persistent sodium current and spontaneous action potential firing. Scn2aQ54 mice congenic on the C57BL/6J strain (B6.Q54) show a progressive epilepsy beginning with spontaneous partial motor seizures that evolve to include secondary generalization as the mice age. Scn2aQ54 mice also exhibit a reduced life span compared with wild-type (WT) animals (13). Genetic background exerts a profound effect on phenotype severity in the Scn2aQ54 model. A single forward cross onto the SJL/J strain (F1.Q54) results in significant worsening of the epilepsy phenotype, with both increased seizure frequency and reduced life span compared with B6.Q54 animals (14).

Previous work identified two modifier loci that contribute to the strain difference in seizure frequency and severity in the Scn2aQ54 model (14). Moe1 (modifier of epilepsy 1) involves multiple genes including Cacna1g, encoding the T-type Ca2+ channel CaV3.1, and Hlf, a PAR bZip transcription factor, whereas Moe2 involves a single gene, Kcnv2, which encodes the silent K+ channel subunit KV8.2 (15–17). Additionally, RNA sequencing analysis of parent mouse strains revealed several other genes with divergent expression between mouse strains that may contribute to strain-dependent epilepsy severity, including genes directly involved in ion transport and posttranslational regulation of ion channel or transporters (18). However, the underlying physiological mechanisms of strain-dependent epilepsy remain unexplored.

Here, we tested the hypothesis that strain-dependent seizure severity in Scn2aQ54 mice results from differential neuronal hyperexcitability stemming from divergent sodium channel properties between strains. We demonstrated that neurons from F1.Q54 animals exhibit enhanced excitability compared with B6.Q54 animals, have greater persistent sodium current, and have sodium channels that are more resistant to inactivation. Additionally, we discovered that CaMKII modulates neuronal voltage-gated sodium conductance and may be an important mediator of strain-dependent seizure severity. Thus, our findings indicate that the epilepsy phenotype of the Scn2aQ54 model may be, in part, driven by divergent strain-dependent sodium channel dysfunction and that CaMKII modulation of neuronal voltage-gated sodium current impacts neuronal excitability.

Results

Scn2aQ54 mice exhibit spontaneous focal epilepsy associated with enhanced persistent sodium current in acutely dissociated hippocampal neurons (13). Additionally, the phenotype shows a strong strain dependence, with animals on a congenic C57BL/6J background (B6.Q54) having a significantly less severe phenotype compared with animals intercrossed with WT SJL/J mice for a single generation (F1.Q54) (14). However, the neurophysiological basis for strain-dependent phenotype severity is unknown.

Strain-Dependent Neuronal Excitability.

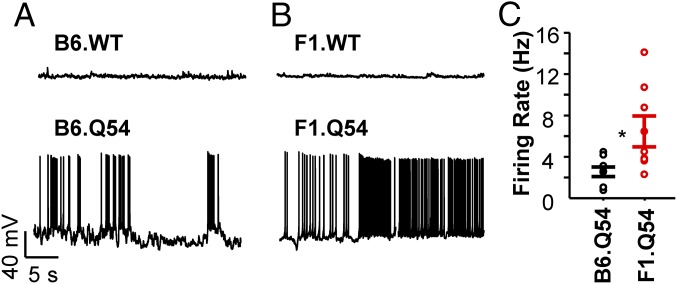

We hypothesized that differences in epilepsy severity observed between B6.Q54 and F1.Q54 animals correlate with differences in excitability of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. We used whole-cell current clamp recording to measure spontaneous and evoked action potential activity in pyramidal neurons isolated from transgenic animals of either background strain. Neurons isolated from WT animals exhibited minimal spontaneous action potential generation, as expected (Fig. 1 A and B). By contrast, and consistent with a spontaneous seizure phenotype, neurons from both strains of Scn2aQ54 animals fired spontaneous action potentials. However, neurons isolated from F1.Q54 animals exhibited a significantly higher frequency of spontaneous action potential firing compared with B6.Q54 animals (Fig. 1C; F1.Q54: 6.5 ± 1.5 Hz vs. B6.Q54: 2.5 ± 0.5 Hz, n = 8–9, P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Spontaneous action potential firing in pyramidal neurons. Representative current clamp recording of spontaneous action potentials from pyramidal neurons isolated from B6.WT and B6.Q54 (A) or F1.WT and F1.Q54 (B) mice. (C) Summary data for spontaneous action potential firing from B6.Q54 (black symbols) and F1.Q54 (red symbols) pyramidal neurons. Open symbols represent individual cells, whereas closed symbols are mean ± SEM for n = 8–9 measurements (*P < 0.05). There were no differences in spontaneous action potential firing frequency between nontransgenic mice on the two genetic backgrounds (B6.WT: 0.2 ± 0.2 Hz, vs. F1.WT: 0.3 ± 0.3 Hz; n = 2).

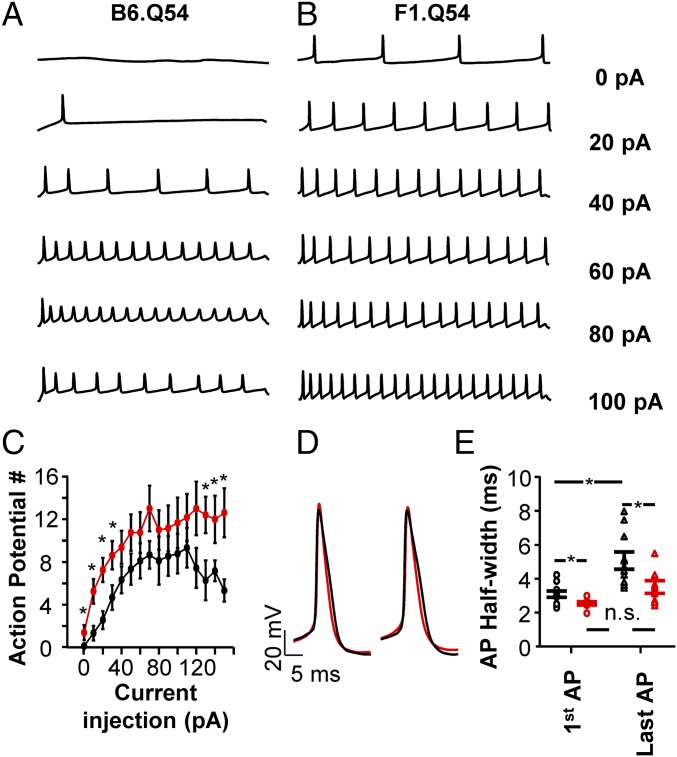

In addition to spontaneous activity, we also measured evoked action potential firing. Similar to spontaneous activity, neurons isolated from F1.Q54 animals exhibited significantly greater evoked activity compared with neurons from B6.Q54 mice across a range of current injection amplitudes (Fig. 2). Neurons from F1.Q54 mice were more excitable at low amplitude current injections and showed sustained activity at stronger stimuli compared with neurons from B6.Q54 animals (Fig. 2 A–C). No differences between strains were detected in either input resistance (B6.Q54 = 1.9 ± 0.3 GΩ vs. F1.Q54 = 2.2 ± 0.4 GΩ) or action potential threshold (B6.Q54 = −42.7 ± 0.8 mV vs. F1.Q54 = −42.5 ± 0.8 mV). Additionally, neurons from F1.Q54 animals displayed a more narrow action potential width both at the beginning and end of a train of action potentials evoked by a 50-pA stimulus (Fig. 2D; first action potential: B6.Q54 = 3.1 ± 0.2 ms vs. F1.Q54 = 2.5 ± 0.1 ms, P < 0.05; final action potential: B6.Q54 = 5.1 ± 0.5 ms vs. F1.Q54 = 3.5 ± 0.4 ms, P < 0.05, n = 8–9). Interestingly, action potential duration increased significantly during a train of action potentials for B6.Q54 animals (first AP: 3.1 ± 0.2 ms vs. last AP: 5.1 ± 0.5 ms, P < 0.05), whereas that of F1.Q54 animals did not (first AP: 2.5 ± 0.1 ms vs. last AP: 3.5 ± 0.4 ms), suggesting an adaptive mechanism present in B6.Q54 animals is absent in neurons from F1.Q54 mice. These results indicate that the strain-dependent epilepsy severity observed for the Scn2aQ54 mouse model is correlated with divergent excitability of hippocampal pyramidal cells. Differences in action potential morphology between strains further suggest variable contribution of conductances necessary for action potential generation and propagation.

Fig. 2.

Evoked action potentials in pyramidal neurons. Representative current clamp recordings of action potentials evoked by escalating amplitude of injected current from pyramidal neurons isolated from B6.Q54 (A) or F1.Q54 (B) mice. Cells were clamped to −80 mV and depolarizing current injections were made in 10-pA increments. (C) Summary data plotting the number of action potentials against current injection for B6.Q54 (black symbols) and F1.Q54 (red symbols) neurons. (D) Representative action potentials from either the second (Left) or final action potential (Right), evoked by a 50-pA current injection for either B6.Q54 (black trace) or F1.Q54 (red) trace. (E) Summary data of action potential half-width from either the first (circles) or final (triangles) action potential, evoked by a 50-pA current injection for either B6.Q54 (black) or F1.Q54 (red) neurons. Open symbols represent individual cells, whereas closed symbols are mean ± SEM for n = 8–9 cells (*P < 0.05; n.s., not significant).

Strain-Dependent Biophysical Properties of Neuronal Sodium Conductance.

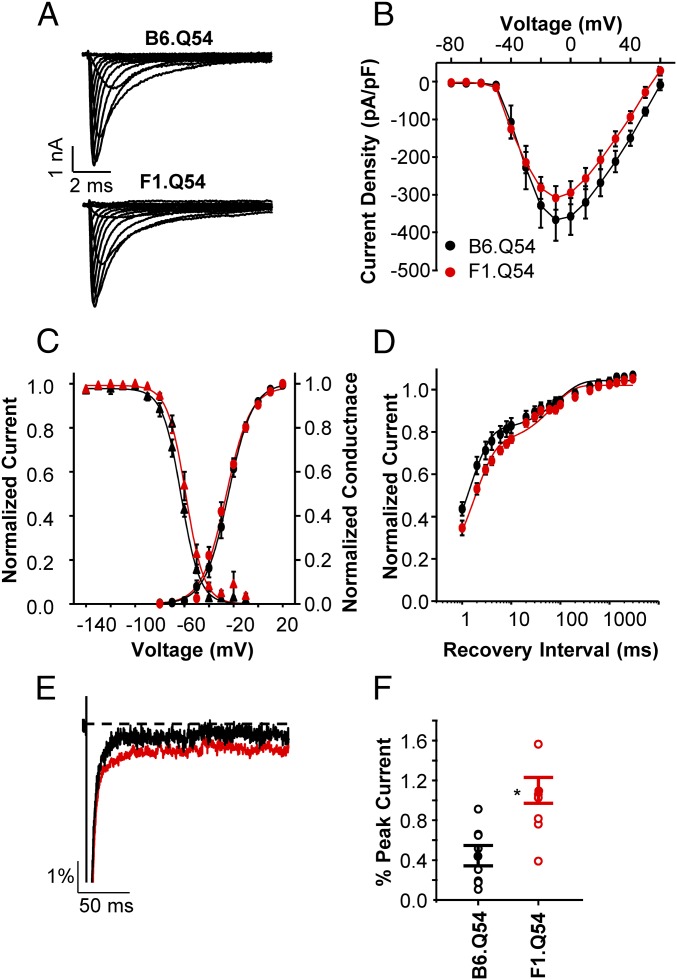

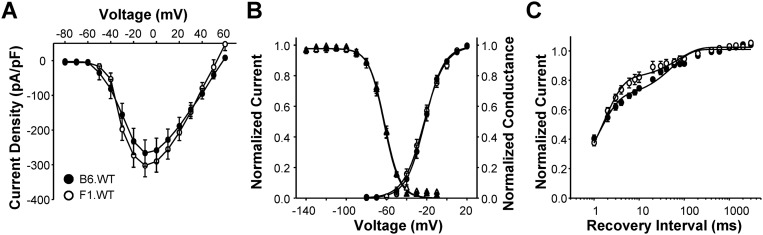

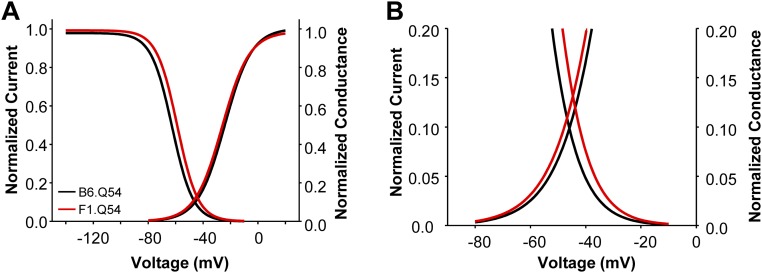

The Scn2aQ54 model was originally generated with a specific defect in voltage-gated sodium channels that gives rise to enhanced persistent sodium current. To determine strain-dependent differences in sodium current, we performed whole-cell voltage clamp recordings from acutely dissociated hippocampal pyramidal neurons from B6.Q54 and F1.Q54 mice, as well as WT animals (B6.WT and F1.WT). Sodium currents from neurons isolated from B6.Q54 and F1.Q54 animals exhibited similar current–voltage relationships and peak current densities (Fig. 3 A and B, B6.Q54: −366.8 ± 55.2 pA/pF vs. F1.Q54: −308.5 ± 31.3 pA/pF, n = 12–15). Further, there were no differences in peak current densities between neurons isolated from the corresponding nontransgenic WT animals (Fig. S1A, B6.WT: −266.4 ± 37.9 pA/pF vs. F1.WT: −302.0 ± 32.5 pA/pF, n = 13–16). Comparison of voltage dependence of activation, and recovery from fast inactivation, between B6.Q54 and F1.Q54 animals showed no significant differences (Fig. 3 C and D and Table 1). However, neurons from F1.Q54 animals exhibited significantly depolarized steady-state channel availability compared with neurons from B6.Q54 animals (Fig. 3C and Table 1). This difference indicated that sodium channels present in F1.Q54 neurons are more resistant to inactivation compared with those present in B6.Q54 animals, and this phenomenon may contribute to neuronal hyperexcitability. Consistent with this hypothesis, neurons from F1.Q54 animals show a larger window current than B6.Q54 neurons, implying a broader voltage range over which F1.Q54 neurons remain active (Fig. S2). No differences in sodium channel properties were detected between WT strains (Fig. S1 and Table 1), which suggests that the observed difference in sodium channel inactivation is mediated by the transgene.

Fig. 3.

Strain dependence of neuronal sodium current. (A) Representative whole-cell sodium current recordings from hippocampal pyramidal neurons isolated from either B6.Q54 (Upper) or F1.Q54 (Lower) mice. (B) Current–voltage relationship of voltage-dependent sodium channels from either B6.Q54 (black symbols) or F1.Q54 (red symbols) neurons. (C) Conductance voltage relationship (circles) and steady-state inactivation (triangles) of voltage-dependent sodium channels from either B6.Q54 (black symbols) or F1.Q54 (red symbols) neurons. (D) Recovery from inactivation of voltage-dependent sodium channels from either B6.Q54 (black symbols) or F1.Q54 (red symbols) neurons. (E) Representative normalized current trace illustrating persistent sodium current in response to a 200-ms depolarization (to 0 mV) from either B6.Q54 (black trace) or F1.Q54 (red trace) neurons. (F) Quantification of persistent current levels of B6.Q54 and F1.Q54 neurons expressed as percent of peak current. Open symbols represent individual cells, whereas closed symbols are mean ± SEM for n = 6–15 cells (*P < 0.05).

Fig. S1.

WT neuronal sodium channel properties. (A) Conductance voltage relationship of voltage-dependent sodium channels from either B6.Q54 (filled symbols) or F1.Q54 (open symbols) neurons. (B) Conductance voltage relationship (circles) and steady-state inactivation (triangles) of voltage-dependent sodium channels from either B6.Q54 (filled symbols) or F1.Q54 (open symbols) neurons. (C) Recovery from inactivation of voltage-dependent sodium channels from either B6.Q54 (filled symbols) or F1.Q54 (open symbols) neurons. Insets depict specific voltage protocols used to measure each biophysical property. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 7–16 cells.

Table 1.

Biophysical properties of Scn2aQ54 neuronal sodium channels

| Voltage dependence of activation | Voltage dependence of fast inactivation | Recovery from fast inactivation | Persistent current | ||||||||

| Strain | V1/2, mV | k, mV | n | V1/2, mV | k, mV | n | τf, ms (amplitude) | τs, ms (amplitude) | n | % peak current | n |

| B6.WT | −23.4 ± 1.7 | 8.6 ± 0.6 | 13 | −60.9 ± 1.9 | −7.1 ± 0.2 | 7 | 1.2 ± 0.1 (0.68 ± 0.04) | 65.4 ± 9.8 (0.33 ± 0.03) | 7 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 8 |

| B6.Q54 | −24.9 ± 1.9 | 9.0 ± 0.5 | 12 | −63.2 ± 1.0 | −7.9 ± 0.8 | 6 | 1.4 ± 0.1 (0.80 ± 0.04) | 119.1 ± 24.5 (0.23 ± 0.04) | 7 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 8 |

| F1.WT | −22.2 ± 1.8 | 9.9 ± 0.9 | 16 | −62.2 ± 1.3 | −7.4 ± 0.4 | 12 | 1.5 ± 0.1 (0.76 ± 0.02) | 79.6 ± 7.9 (0.25 ± 0.01) | 10 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 5 |

| F1.Q54 | −26.5 ± 1.5* | 9.0 ± 0.4 | 15 | −59.6 ± 1.0† | −7.1 ± 0.4 | 10 | 1.9 ± 0.2 (0.73 ± 0.02) | 81.8 ± 10.4 (0.28 ± 0.02) | 11 | 1.1 ± 0.2† | 6 |

P < 0.05 compared with nontransgenic animals of the same genetic background.

P < 0.05 compared with B6.Q54 animals.

Fig. S2.

Sodium channel window current. (A) Superimposed Boltzmann fits of neuronal sodium channel voltage dependence of activation and inactivation from either B6.Q54 (black lines) or F1.Q54 (red lines) neurons. (B) Enlargement of overlapping regions of channel voltage-dependent activation and inactivation curves, showing larger window current determined for F1.Q54 neuronal sodium channels.

Strain Dependence of Persistent Sodium Current.

We hypothesized that strain dependence of neuronal excitability may be due, in part, to differences in persistent sodium current between B6.Q54 and F1.Q54 animals. We found that B6.Q54 pyramidal neurons had persistent current levels that were not significantly different from WT mice (Table 1). However, pyramidal neurons isolated from F1.Q54 animals exhibited greater levels of persistent current compared with neurons from B6.Q54 mice (Fig. 3 E and F, 1.1 ± 0.2% vs. 0.4 ± 0.1, n = 6–8, P < 0.05). These data suggest that higher levels of persistent current in hippocampal pyramidal neurons correlate with enhanced excitability.

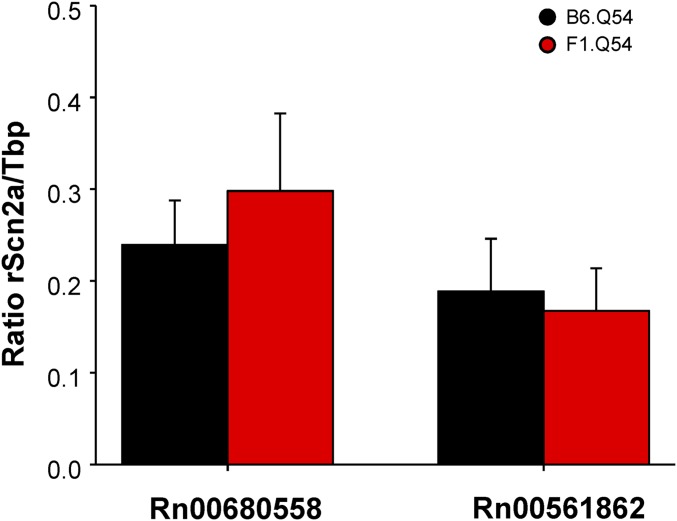

To exclude unequal transgene expression between B6.Q54 and F1.Q54 as an explanation for differences in persistent current, we quantified hippocampal transcript levels of rat NaV1.2 by using quantitative digital droplet RT-PCR (ddRT-PCR). Using two separate assays that are specific for the transgene, we found no difference in hippocampal transgene levels between B6.Q54 and F1.Q54 animals (Fig. S3; Assay Rn00680558: B6.Q54, 0.19 ± 0.03 vs. F1.Q54, 0.22 ± 0.05; Assay Rn00561862: B6.Q54, 0.13 ± 0.02 vs. F1.Q54 0.15 ± 0.05), thereby excluding divergent expression of the transgene. Therefore, we considered other factors that could account for the differences in sodium channel behavior.

Fig. S3.

Analysis of transgene expression level. Quantification of transgene transcript expression was determined by ddPCR of hippocampal first-strand cDNA using two separate assays specific for rat Scn2a. Relative transcript levels are expressed as a ratio of rat Scn2a concentration to Tbp concentration. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of five to seven biological replicates.

Strain-Dependent Hippocampal CaMKII Activity.

Previous work has shown that the cardiac sodium channel NaV1.5 can be modulated by intracellular Ca2+ and by CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation, which have profound effects on channel inactivation and persistent sodium current (8, 10, 19). Elevated intracellular Ca2+ has been demonstrated to evoke a depolarized shift in the voltage dependence of inactivation and suppression of persistent sodium current for cardiac NaV1.5 channels (8, 20). Similarly, CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of NaV1.5 causes a shift in the voltage dependence of inactivation, as well as increased persistent sodium current (10, 19, 21, 22). We examined the effects of Ca2+ and CaMKII on the Scn2aQ54 mutant to determine whether these factors could explain the observed differences in channel inactivation and persistent sodium current.

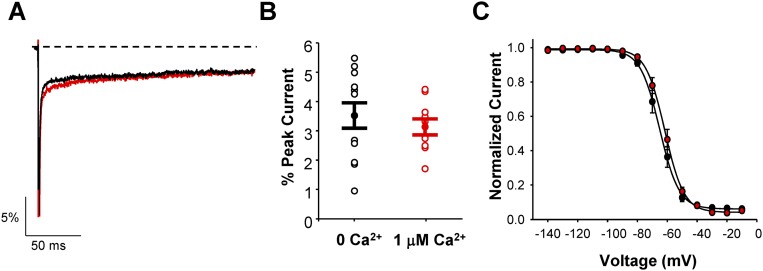

The voltage dependence of inactivation and magnitude of persistent sodium current were determined in the absence and presence of 1 μM free Ca2+ for heterologously expressed mutant rat NaV1.2 channels (NaV1.2-Q54; SI Materials and Methods), which is the Scn2aQ54 transgene. We observed no difference in the level of persistent sodium current between these two conditions (0 Ca2+: 3.5 ± 0.4%; 1 μM Ca2+: 3.1 ± 0.3%, n = 10–12, P = 0.48), and only a slight, but nonsignificant, depolarized shift in the voltage dependence of inactivation (0 Ca2+: −65.1 ± 2.0 mV; 1 μM Ca2+: −61.7 ± 1.8 mV, n = 10, P = 0.21; Fig. S4 A–C). These findings were consistent with previous reports showing no effect of intracellular Ca2+ on inactivation of WT NaV1.2 channels (23). We conclude from these data that the strain differences in neuronal sodium current properties do not depend strictly on intracellular Ca2+ concentration.

Fig. S4.

Effect of intracellular Ca2+ on neuronal sodium current. (A) Representative normalized current trace showing persistent sodium current in response to a 200-ms depolarization (to 0 mV) from HEK293T cells transfected with NaV1.2-Q54 in the presence of 0 μM Ca2+ (black trace) or 1 μM Ca2+ (red trace) neurons. Inset shows final 50 ms of the 200-ms depolarized voltage step. (B) Quantification of persistent current levels of NaV1.2-Q54 in the presence of 0 μM Ca2+ or 1 μM Ca2+ expressed as percent of peak current. (C) Steady-state inactivation for sodium channels in the presence of 0 μM Ca2+ (black symbols) or 1 μM Ca2+ (red symbols). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 9–11 cells (*P < 0.05).

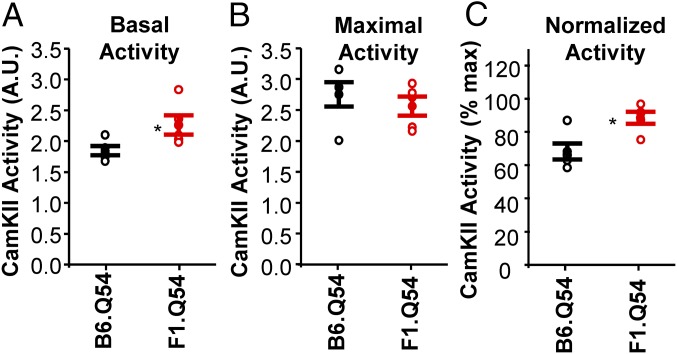

To determine whether divergent CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation underlies strain-dependent differences in voltage-gated sodium current, we quantified basal and maximal CaMKII activity from hippocampal protein lysates from B6.Q54 and F1.Q54 animals, and WT littermates. Basal hippocampal CaMKII activity measured in samples from F1.Q54 animals was significantly greater than in samples from B6.Q54 animals (2.3 ± 0.16 A.U. vs. 1.8 ± 0.07 A.U., P < 0.05, n = 5; Fig. 4A). Levels of maximal CaMKII activity, which were measured after adding exogenous Ca2+ and CaM to protein lysates, were not different between Scn2aQ54 strains (B6.Q54, 2.8 ± 0.2 A.U.; F1.Q54, 2.6 ± 0.6 A.U., P = 0.79, n = 5; Fig. 4B). Further, basal CaMKII activity normalized to maximal activity was significantly greater in samples from F1.Q54 mice compared with B6.Q54 animals (88.4 ± 3.6% vs. 68.2 ± 4.8%, P < 0.05, n = 5; Fig. 4C). There were no differences in basal or maximal CaMKII activity between WT littermates from the different genetic backgrounds (B6.WT, basal, 1.8 ± 0.03 A.U., maximal, 2.6 ± 0.04 A.U., n = 3; F1.WT, basal, 1.8 ± 0.05 A.U., maximal, 2.6 ± 0.07 A.U., n = 5). These differences suggest that differential CaMKII activity between mouse strains may contribute to strain-dependent differences in seizure severity in Scn2aQ54 mice.

Fig. 4.

Strain dependence of hippocampal CaMKII activity. (A) Basal CaMKII activity of hippocampal protein lysates from B6.Q54 (black symbols) or F1.Q54 (red symbols) reported as absorbance at 450 nM. (B) Maximal CaMKII activity following stimulation with Ca2+/CaM measured in hippocampal protein lysates from B6.Q54 (black symbols) or F1.Q54 (red symbols) reported as absorbance at 450 nM. (C) Basal CaMKII activity normalized to maximal activity for B6.Q54 (black symbols) or F1.Q54 (red symbols). Open symbols represent individual animals, whereas closed symbols are mean ± SEM for n = 5 animals (*P < 0.05).

Regulation of Sodium Channel Inactivation by CaMKII.

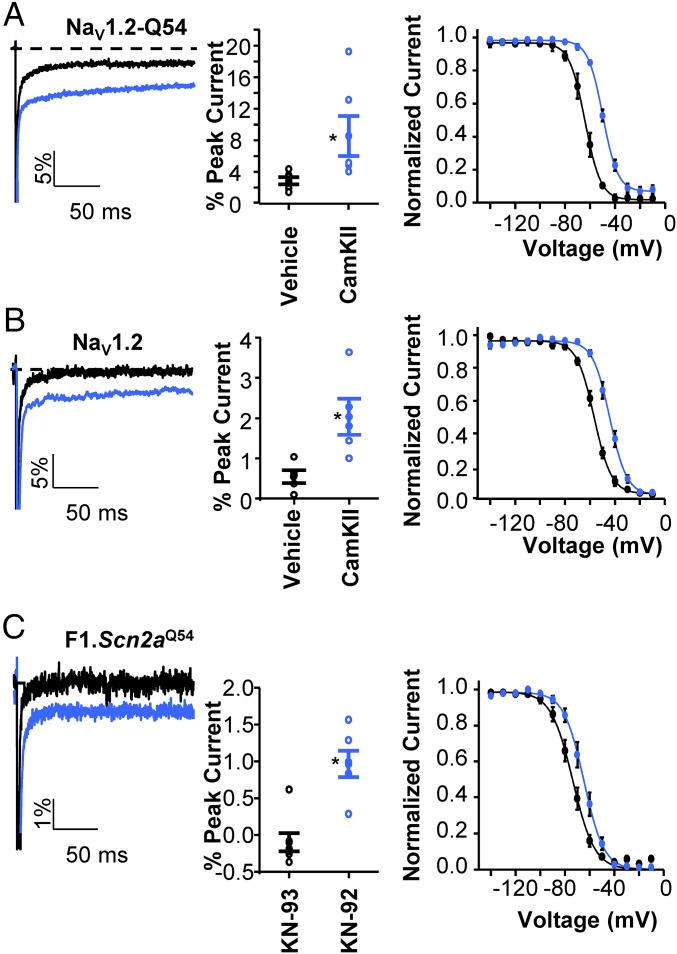

We assessed whether CaMKII modulates persistent sodium current and voltage dependence of channel inactivation exhibited by heterologously expressed NaV1.2-Q54. When activated CaMKII monomer was included in the intracellular pipette solution, persistent sodium current mediated by NaV1.2-Q54, was 8.5 ± 2.5% (n = 6) compared with 2.8 ± 0.4% for cells exposed to vehicle alone (n = 6, P < 0.05; Fig. 5A). Additionally, we observed a large depolarized shift in the voltage dependence of inactivation compared with cells exposed to vehicle (Fig. 5A, −49.6 ± 1.2 mV vs. −61.9 ± 2.4 mV, n = 3–5, P < 0.05). Importantly, we found that CaMKII exerts similar effects on WT NaV1.2 to enhance persistent sodium current (CaMKII = 2.0 ± 0.4%; Vehicle = 0.5 ± 0.2%, n = 6, P < 0.05; Fig. 5B) and induce a large depolarized shift in the voltage dependence of inactivation (−43.7 ± 1.5 mV vs. −56.4 ± 1.1 mV, n = 4–5, P < 0.05; Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

CaMKII regulation of voltage-gated sodium current. (A and B, Left) Representative normalized current trace illustrating persistent sodium current in response to a 200-ms depolarization (to 0 mV) recorded from HEK293T cells transfected with NaV1.2-Q54 (A) or NaV1.2-WT (B) in the presence of activated CaMKII monomer (blue trace) or vehicle (black trace). (A and B, Center) Quantification of persistent current levels of NaV1.2-Q54 (A) or NaV1.2-WT (B) in the presence of activated CaMKII monomer or vehicle expressed as percent of peak current. (A and B, Right) Steady-state inactivation for sodium channels in the presence of activated CaMKII monomer (blue symbols) or vehicle (black symbols). (C, Left) Representative normalized current trace illustrating persistent sodium current in response to a 200-ms depolarization (to 0 mV) recorded from F1.Q54 pyramidal neurons in the presence of 10 μM KN-93 (black trace) or 10 μM KN-92 (blue trace). (C, Center) Quantification of persistent current levels from pyramidal neurons in the presence of 10 μM KN-93 or 10 μM KN-92 expressed as percent of peak current. (C, Right) Steady-state inactivation for sodium channels in the presence of 10 μM KN-93 (black symbols) or 10 μM KN-92 (blue symbols). Open symbols represent individual cells, whereas closed symbols are expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 3–7 cells (*P < 0.05).

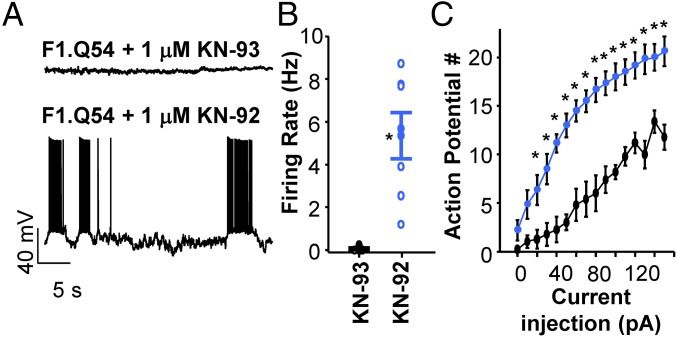

We also compared persistent current and steady-state inactivation in pyramidal neurons isolated from F1.Q54 animals pretreated with either KN-93, a CaMKII inhibitor, or KN-92, an inactive analog. Fig. 5C illustrates that neurons treated with KN-93 exhibited virtually no persistent current (0.1 ± 0.1% n = 6) and a hyperpolarized V1/2 for steady-state inactivation (V1/2 = −73.9 ± 2.2 mV, n = 6) compared with neurons treated with KN-92 (0.96 ± 0.2% n = 7, V1/2 = −64.9 ± 2.3 mV, n = 7, P < 0.05, compared with KN-93–treated cells). Finally, we compared spontaneous firing frequency of neurons treated intracellularly with 1 μM KN-93 or 1 μM KN-92 and found that suppression of CaMKII activity with KN-93 abolished spontaneous firing of F1.Q54 neurons (0.06 ± 0.04 Hz, n = 7). By contrast, neurons treated with KN-92 exhibited a high spontaneous firing frequency (5.4 ± 1.1 Hz, n = 7, P < 0.05; Fig. 6 A and B) similar to untreated cells. We also observed that KN-93–treated neurons showed less evoked action potential firing compared with neurons treated with KN-92 (Fig. 6C). These data support our hypothesis that differential modulation of sodium channels by CaMKII significantly impacts neuronal excitability.

Fig. 6.

CaMKII regulation of neuronal excitability. (A) Representative current clamp recordings of spontaneous action potential activity from F1.Q54 animals in the presence of either 1 μM intracellular KN-93 (Upper) or 1 μM KN-92 (Lower). (B) Summary data for spontaneous action potential firing from KN-93 (black symbols) and KN-92 (blue symbols) treated pyramidal neurons. Open symbols represent individual cells. (C) Summary data plotting the number of action potentials against current injection for KN-93 (black symbols) and KN-92 (blue symbols) treated neurons. Closed symbols represent mean ± SEM for n = 5–7 measurements (*P < 0.05).

SI Materials and Methods

Generation of Scn2a-Q54 mice.

Scn2aQ54 mice [Tg(Eno2-Scn2a1*)Q54Mm] were generated as described (13). The line is maintained as a congenic strain on C57BL/6J (B6.Q54) by continued backcrossing of hemizygous B6.Q54 males to C57BL/6J females (stock no. 000664; Jackson Laboratory). F1.Q54 mice are generated by crossing hemizygous B6.Q54 males to SJL/J females (stock no. 000686, Jackson Laboratory).

Acute Dissociation of Hippocampal Neurons.

Neurons were isolated as described (33). Briefly, male and female mice [age range postnatal day (P)21–P24] were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane then rapidly decapitated. The brain was promptly removed under aseptic conditions and placed in ice-cold dissecting solution containing (in mM) 2.5 KCl, 110 NaCl, 7.5 MgCl2·6H2O, 10 Hepes, 25 dextrose, 75 sucrose, with pH adjusted to 7.35 with NaOH. Coronal slices (400 µm) were made through the hippocampi by using a Leica VT 1200 vibratome (Leica Microsystems) in ice-cold dissecting solution bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. Slices were incubated for 1 h at 30 °C in artificial CSF (ACSF, in mM: 124 NaCl, 4.4 KCl, 2.4 CaCl2·2H2O, 1.3 MgSO4, 1 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, and 10 Hepes with pH adjusted to 7.35 with NaOH) bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2.

Hippocampi were dissected from the slices and digested for 10–15 min at room temperature with proteinase (1 mg/mL) from Aspergillus melleus type XXIII in dissociation solution (in mM: 82 Na2SO4, 30 K2SO4, 5 MgCl2·6H2O, 10 Hepes, and 10 dextrose with pH adjusted to 7.35 with NaOH), then washed multiple times with dissociation solution containing 1 mg/mL BSA and allowed to recover for ≥10 min before mechanical dissociation by gentle trituration with sequentially fire-polished Pasteur pipettes of decreasing diameter. The cell suspension was allowed to settle on coverslips for 5 min before experiments. Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Mutagenesis and Heterologous Expression of NaV1.2.

Mutagenesis of recombinant rat NaV1.2 (rNaV1.2) was performed as described (33–37). Three mutations (GAL879-881QQQ) were introduced into full-length rNaV1.2 to generate rNaV1.2GAL879-881QQQ (designated NaV1.2-Q54). To minimize spontaneous mutagenesis of rNaV1.2 cDNA in bacterial culture, recombinants were always propagated in Stbl2 cells (Invitrogen) at 30 °C. The ORF of all plasmid preparations were fully sequenced before transfection.

Heterologous expression of rNaV1.2 was performed in HEK293T cells. Cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 units/mL penicillin, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. Expression of rNaV1.2 and the accessory β1 and β2 subunits was achieved by using transient transfection with Qiagen SuperFect reagent (Qiagen) (2 μg of total plasmid DNA was transfected with a cDNA ratio of 10:1:1 for α1:β1:β2 subunits). Human β1 and β2 cDNAs were cloned into plasmids also encoding the CD8 receptor (CD8-IRES-hβ1) or enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) (EFGP-IRES-hβ2), respectively, as transfection markers.

Voltage-Clamp Recording.

Glass coverslips with plated hippocampal neurons were placed into the recording chamber of an inverted microscope equipped with a Moticam 3000 digital camera. Individual neurons were photographed, then whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were made at room temperature by using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices) in the absence and presence of 500 nM tetrodotoxin. Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (Harvard Apparatus Ltd.) with a multistage P-97 Flaming-Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instruments) and fire-polished by using a microforge (Narashige MF-830) to a pipette resistance of 1.5–2.5 MΩ. For sodium channel recording, the pipette solution consisted of (in mM) 5 NaF, 105 CsF, 20 CsCl, 2 EGTA, and 10 Hepes with pH adjusted to 7.35 with CsOH and osmolarity adjusted to 280 mOsmol/kg with sucrose. The recording chamber was continuously perfused with a bath solution containing (in mM) 20 NaCl, 100 N-methyl-d-glucamine, 10 Hepes, 1.8 CaCl2·2H2O, 2 MgCl2·6H2O, and 20 tetraethylammonium chloride with pH adjusted to 7.35 with HCl and osmolarity adjusted to 310 mOsmol/kg with sucrose. The reference electrode consisted of a 2% (mass/vol) agar bridge with composition similar to the bath solution. Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Whole-cell voltage clamp experiments of heterologous cells were performed as described (37). The recording solution was continuously perfused with bath solution containing (in mM) 145 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Glucose, and 10 Hepes with pH 7.35 and osmolarity 310 mOsmol/kg. For experiments measuring the effect of intracellular Ca2+, the recording pipette was filled with a calcium-free solution containing (in mM) 10 NaF, 100 CsF, 20 CsCl2, 20 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA), and 10 Hepes, or with a solution containing 1 μM free calcium composed of (in mM) 10 NaF, 100 CsF, 20 CsCl2, 1 BAPTA, 10 Hepes, and 0.9 CaCl2, with pH adjusted to 7.35 with CsOH and osmolarity adjusted to 310 with sucrose. For experiments measuring the effect of CamKII, recording pipettes were filled with solution containing (in mM) 10 NaMeSO3, 120 CsMeSO3, 1.5 CaCl2, 5 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 10 Glucose, and 5 MgATP, pH adjusted to 7.35 with CsOH. CaMKII (New England Biolabs) was activated by diluting 50,000 units of enzyme in a reaction buffer containing (in mM) 50 Tris⋅HCl, 10 MgCl2, 2 DTT, 2 CaCl2, 0.1 EDTA, 0.2 MgATP, and 0.0012 calmodulin. Activated CamKII, or vehicle control substituting glycerol for CamKII, was diluted 1:25 in pipette solution such that the final CamKII concentration was 2000 U/mL (19). For experiments measuring the effect of either KN-93 or KN-92 in neurons, cells were incubated in extracellular solution containing 10 μM KN-93 or KN-92 for 15 min before recording. Recording solutions were as described above for neuronal voltage-gated sodium channel recording. KN-93 and KN-92 were obtained from Tocris Bioscience, prepared as 10 mM stocks in DMSO, and diluted to 10 μM in extracellular recording solution the day of experiment.

Voltage-clamp pulse generation and data collection were done by using Clampex 10.2 (Molecular Devices, LLC). Whole-cell capacitance was determined by integrating capacitive transients generated by a voltage step from −120 mV to −110 mV filtered at 100 kHz low-pass Bessel filtering. Series resistance was compensated with prediction >70% and correction >85% to assure that the command potential was reached within microseconds with a voltage error <3 mV. Leak currents were subtracted by using an online P/4 procedure. All whole-cell currents were filtered at 5 kHz low-pass Bessel filtering and digitized at 50 kHz. All voltage-clamp experiments were conducted at room temperature (20–23 °C).

Current Clamp Recording.

Whole-cell recordings of neuronal cell bodies were made in current clamp mode by using an Axon MultiClamp 700B amplifier. Patch pipettes were fabricated from borosilicate glass to have pipette resistance 2.0–2.5 MΩ when filled with a solution containing (in mM: 110 K-gluconate, 10 NaCl, 10 KCl, 0.1 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, 5 EGTA, 10 Tris-phosphocreatine, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP, pH 7.35, 280 mOsmol/kg). Bath solution consisted of (in mM) 155 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, 10 Dextrose at pH 7.35. The reference electrode consisted of a 2% (mass/vol) agar bridge with composition of the bath solution. Recordings were low-pass Bessel filtered at 5 kHz and digitized at 50 kHz. Membrane potential was clamped to −80 mV for both spontaneous and evoked action potential firing measurements. Action potentials were evoked by a 500-ms depolarizing current injection in 10-pA increments. All current clamp experiments were conducted at room temperature (20–23 °C). KN-93 and KN-92 were prepared as 2 mM stocks and were diluted to 1 μM in intracellular pipette solution the day of the experiment.

Electrophysiological Data Analyses.

Data were analyzed by using a combination of Clampfit 10.2 (Molecular Devices), Excel 2007 (Microsoft), and SigmaPlot 10.0 (Systat Software). The peak current was normalized for cell capacitance and plotted against step voltage to generate a peak current density–voltage relationship. Whole-cell conductance (GNa) was calculated as GNa = I/(V – Erev), where I is the measured peak current, V is the step voltage, and Erev is the calculated sodium reversal potential. GNa at each voltage step was normalized to the maximum conductance between −80 mV and 20 mV. To calculate voltage dependence of activation (protocol described in figure insets), normalized GNa was plotted against voltage and fitted with the Boltzmann function G/Gmax= (1 + exp[(V – V1/2)/k])−1, where V1/2 indicates the voltage at half-maximal activation and k is a slope factor describing voltage sensitivity of the channel. Voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation was assessed by plotting currents generated by the −10 mV postpulse voltage step normalized to the maximum current against prepulse voltage step from −140 to −10 mV in 10-mV increments. The plot was fitted with the Boltzmann function.

Spontaneous action potential firing was measured as the number of action potentials fired over a period of 3–8 min. Action potentials were counted in pClamp 10 by using threshold search, with an overshoot crossing 0 mV being counted as an action potential. Frequency was determined by dividing the number of action potentials fired by the measured time period in seconds. Evoked action potential firing was measured in pClamp 10 as the number of action potentials evoked over 500 ms as a function of current injection.

Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed by using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Intact hippocampi were dissected from male and female (B6.Q54 and F1.Q54 mice (age P21). Total hippocampal RNA was extracted by using the TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies). RNA was DNase treated by using TURBO DNA-free according to the manufacturer’s instructions for routine treatment (Life Technologies). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 4 μg of RNA by using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (RT) (Life Technologies). First-strand cDNA samples were diluted 1:2 and 5 µL was used as template. ddPCR was performed by using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Life Technologies) for rat Scn2a (FAM-MGB-Rn00561862_m1 and FAM-MGB-Rn00680558_m1) and TATA binding protein (Tbp) (VIC-MGB-Mm00446971_m1) and ddPCR Supermix for Probes (No dUTP) (Bio-Rad). Reactions were partitioned into 20,000 droplets (1 nL each) in a QX200 droplet generator (Bio-Rad). Thermocycling conditions were 95 °C for 10 min, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min (ramp rate of 2 °C/sec), and a final inactivation step of 98 °C for 10 min. Following amplification, droplets were analyzed with a QX200 droplet reader with QuantaSoft v1.6.6.0320 software (Bio-Rad). Rat Scn2a assays lacked detectable signal in WT mouse samples; all assays lacked detectable signal in no-RT and no template controls. Relative transcript levels were expressed as a ratio of rat Scn2a concentration to Tbp concentration. Statistical comparison between groups was made by using unpaired Student’s t tests. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of four to six biological replicates.

CamKII Phosphyorylation ELISA.

Whole hippocampi were dissected from P21 to P24 mice and flash frozen. Protein lysates were prepared in N-PER neuronal protein extraction reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche). Supernatants were collected after centrifugation (13,600 × g) for 30 min at 4 °C and used for CamKII activity measurements (CycLex CamKII assay, MBL International). The BCA protein assay (Bio-Rad) was used to determine protein concentration in each sample to ensure equal protein loading. Each well was loaded with 1 μg of protein in a reaction mixture either in the presence or absence of Ca2+/CaM to measure maximal and basal CamKII activity, respectively. We performed the assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol, with each protein sample assayed in duplicate. CamKII activity was measured by using a Varioskan Lux plate reader (Thermo Scientific) by measuring absorbance at 450 nM.

Discussion

Mutations in voltage-gated sodium channel genes are associated with a spectrum of genetic epilepsies that may exhibit variable expressivity, which is attributable in part to the action of genetic modifiers. The influence of genetic modifiers on variable expressivity can be studied by using engineered mice bearing mutations in sodium channel genes. In this study, we examined the strain-dependent seizure severity observed in the gain-of-function Scn2aQ54 epileptic mouse and identified neurophysiological features that may contribute to variable phenotype expression.

The Scn2aQ54 mouse model exhibits spontaneous seizures originating within the hippocampus, the severity of which depends greatly on genetic background. These mice show increased persistent sodium current as a result of mutant Scn2a transgene expression, and this phenomenon is a plausible contributing factor to epilepsy. Extracellular recording of hippocampal slices from F1.Q54 animals showed that both the CA1 and CA3 regions show spontaneous action potential firing not present in WT mice (24). Additionally, brain slices from F1.Q54 animals have greater spontaneous and after-discharge activity following tetanic stimulation (24). Consistent with this prior work, we demonstrated that hippocampal pyramidal neurons isolated from WT animals show no spontaneous action potentials, but pyramidal neurons isolated acutely from either B6.Q54 or F1.Q54 animals exhibit spontaneous action potentials, with cells from F1.Q54 mice having a higher firing frequency. Additionally, F1.Q54 animals exhibit significantly greater evoked action potential firing.

Action potential morphology is an important contributor to neuronal firing frequency, with high frequency firing being associated with narrow action potential width (25). We observed that pyramidal neurons from F1.Q54 mice exhibited narrower action potentials compared with neurons from B6.Q54 animals. Moreover, neurons from B6.Q54 animals exhibited a trend toward a greater degree of action potential broadening during a train of action potentials compared with neurons from F1.Q54 animals (Fig. 2), consistent with the hypothesis that excitatory neurons from F1.Q54 animals can maintain higher firing rates for longer periods of time and may promote a more severe seizure phenotype. Although increased persistent current is predicted to broaden action potentials in neurons from F1.Q54 mice, previously reported strain-dependent differences in K+ channel expression may also contribute in a manner opposing the effect of enhanced sodium current (15). Specifically, B6.Q54 mice express a higher level of Kcnv2, a silent K+ channel subunit that forms heterotetramers with KV2.1 and suppresses delayed rectifier current. Reduced KV2.1-mediated current is predicted to enhance excitability of neurons from B6.Q54 mice, similar to what has been demonstrated for KV2.1 knockout mice, and evoked action potential broadening during a train of action potentials (26), which is what we observed in this study (Fig. 2).

We observed no strain differences in sodium channel properties measured from WT neurons. By contrast, neurons isolated from F1.Q54 animals exhibited higher levels of persistent current and a depolarized steady-state inactivation compared with B6.Q54 mice. A consequence of the shift in steady-state inactivation for F1.Q54 animals compared with B6.Q54 animals is a larger window current, which has been shown to be a common feature of cardiac arrhythmias resulting from mutations in SCN5A (27, 28). The greater tendency for spontaneous action potential firing observed in F1.Q54 neurons may be a result of both increased persistent current and increased window current. Importantly, the larger persistent sodium current could not be explained by differences in transgene expression within brain regions we used to isolate neurons for electrophysiological recording. These observations suggest the existence of other factors that may modulate sodium channels.

We sought to understand the basis for different persistent current levels between B6.Q54 and F1.Q54 animals. Phosphorylation of sodium channels is a critical regulator of channel activity, with phosphorylation state changing dramatically as a function of seizure activity in the brain (6, 7). In the heart, CaMKII phosphorylation has been shown to enhance persistent sodium current and induce a shift in steady-state channel availability (19). Although the sites for CaMKII phosphorylation of NaV1.5 are not perfectly conserved across all sodium channels, 24 of 36 CaMKII phosphorylation sites identified by either mass spectrometry analysis or functional analyses, including the critical sites S516 and S571, are conserved in rodent NaV1.2 (10, 21). Our experiments demonstrated that hippocampal lysates from Scn2aQ54 mouse strains have divergent levels of CaMKII activity. Previous reports have shown that CaMKII autophosphorylation is initially reduced in various epilepsy models, including pilocarpine and kainic acid-induced seizure models, but total CaMKII protein may be increased in prolonged timepoints following seizure onset (29–31). Interestingly, WT littermates do not show strain dependence of CaMKII activity, suggesting that seizures may also influence CaMKII activity in the hippocampus of Scn2aQ54 mice. Although our findings strongly support CaMKII modulation of neuronal sodium current and excitability of neurons from Scn2aQ54 mice, we cannot exclude epileptogenic effects of CaMKII on other cellular targets that also have strain dependence.

In summary, our work demonstrated CaMKII modulation of neuronal sodium channels in heterologous cells and in acutely isolated neurons from a mouse model of epilepsy. CaMKII evokes a mechanism to regulate neuronal sodium current in a manner that impacts neuronal excitability. Pharmacological strategies for suppressing CaMKII activity in brain might conceivably exert antiepileptic effects.

Materials and Methods

All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Northwestern University in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (32). Hippocampal neuron dissociations were performed as described (33). All mutagenesis, heterologous expression, voltage-clamp, and current-clamp recordings were performed as described (33–37). For description of materials and methods used, SI Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sunita Misra for initial assistance with project and Jeffrey Calhoun, Alison Miller, Clint McCollom, and Nicole Zachwieja for mouse colony assistance. This work was supported by Epilepsy foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship 189645 (to C.H.T.) and NIH Grants NS053792 (to J.A.K.) and NS032387 (to A.L.G.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1615774114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Catterall WA, Kalume F, Oakley JC. NaV1.1 channels and epilepsy. J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 11):1849–1859. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.187484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.George AL., Jr Inherited disorders of voltage-gated sodium channels. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):1990–1999. doi: 10.1172/JCI25505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang C, Wang C, Hoch EG, Pitt GS. Identification of novel interaction sites that determine specificity between fibroblast growth factor homologous factors and voltage-gated sodium channels. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(27):24253–24263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.245803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pablo JL, Wang C, Presby MM, Pitt GS. Polarized localization of voltage-gated Na+ channels is regulated by concerted FGF13 and FGF14 action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(19):E2665–E2674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521194113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan H, Pablo JL, Wang C, Pitt GS. FGF14 modulates resurgent sodium current in mouse cerebellar Purkinje neurons. eLife. 2014;3:e04193. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baek JH, Rubinstein M, Scheuer T, Trimmer JS. Reciprocal changes in phosphorylation and methylation of mammalian brain sodium channels in response to seizures. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(22):15363–15373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.562785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheuer T. Regulation of sodium channel activity by phosphorylation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22(2):160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potet F, Beckermann TM, Kunic JD, George AL., Jr Intracellular calcium attenuates late current conducted by mutant human cardiac sodium channels. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8(4):933–941. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.002760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Petegem F, Lobo PA, Ahern CA. Seeing the forest through the trees: Towards a unified view on physiological calcium regulation of voltage-gated sodium channels. Biophys J. 2012;103(11):2243–2251. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashpole NM, et al. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) regulates cardiac sodium channel NaV1.5 gating by multiple phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(24):19856–19869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.322537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meisler MH, Kearney JA. Sodium channel mutations in epilepsy and other neurological disorders. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2010–2017. doi: 10.1172/JCI25466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meisler MH, O’Brien JE, Sharkey LM. Sodium channel gene family: Epilepsy mutations, gene interactions and modifier effects. J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 11):1841–1848. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.188482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kearney JA, et al. A gain-of-function mutation in the sodium channel gene Scn2a results in seizures and behavioral abnormalities. Neuroscience. 2001;102(2):307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00479-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergren SK, Chen S, Galecki A, Kearney JA. Genetic modifiers affecting severity of epilepsy caused by mutation of sodium channel Scn2a. Mamm Genome. 2005;16(9):683–690. doi: 10.1007/s00335-005-0049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorge BS, et al. Voltage-gated potassium channel KCNV2 (Kv8.2) contributes to epilepsy susceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(13):5443–5448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017539108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkins NA, Kearney JA. Hlf is a genetic modifier of epilepsy caused by voltage-gated sodium channel mutations. Epilepsy Res. 2016;119:20–23. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calhoun JD, Hawkins NA, Zachwieja NJ, Kearney JA. Cacna1g is a genetic modifier of epilepsy caused by mutation of voltage-gated sodium channel Scn2a. Epilepsia. 2016;57(6):e103–e107. doi: 10.1111/epi.13390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawkins NA, Kearney JA. Confirmation of an epilepsy modifier locus on mouse chromosome 11 and candidate gene analysis by RNA-Seq. Genes Brain Behav. 2012;11(4):452–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00790.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aiba T, et al. Na+ channel regulation by Ca2+/calmodulin and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85(3):454–463. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wingo TL, et al. An EF-hand in the sodium channel couples intracellular calcium to cardiac excitability. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11(3):219–225. doi: 10.1038/nsmb737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herren AW, et al. CaMKII phosphorylation of Na(V)1.5: Novel in vitro sites identified by mass spectrometry and reduced S516 phosphorylation in human heart failure. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(5):2298–2311. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hund TJ, et al. A β(IV)-spectrin/CaMKII signaling complex is essential for membrane excitability in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(10):3508–3519. doi: 10.1172/JCI43621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang C, et al. Structural analyses of Ca2+/CaM interaction with NaV channel C-termini reveal mechanisms of calcium-dependent regulation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4896. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kile KB, Tian N, Durand DM. Scn2a sodium channel mutation results in hyperexcitability in the hippocampus in vitro. Epilepsia. 2008;49(3):488–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bean BP. The action potential in mammalian central neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(6):451–465. doi: 10.1038/nrn2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Speca DJ, et al. Deletion of the Kv2.1 delayed rectifier potassium channel leads to neuronal and behavioral hyperexcitability. Genes Brain Behav. 2014;13(4):394–408. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beckermann TM, McLeod K, Murday V, Potet F, George AL., Jr Novel SCN5A mutation in amiodarone-responsive multifocal ventricular ectopy-associated cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(8):1446–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen TP, Wang DW, Rhodes TH, George AL., Jr Divergent biophysical defects caused by mutant sodium channels in dilated cardiomyopathy with arrhythmia. Circ Res. 2008;102(3):364–371. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kochan LD, Churn SB, Omojokun O, Rice A, DeLorenzo RJ. Status epilepticus results in an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent inhibition of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II activity in the rat. Neuroscience. 2000;95(3):735–743. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00462-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamagata Y, Imoto K, Obata K. A mechanism for the inactivation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II during prolonged seizure activity and its consequence after the recovery from seizure activity in rats in vivo. Neuroscience. 2006;140(3):981–992. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu XB, Murray KD. Neuronal excitability and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II: Location, location, location. Epilepsia. 2012;53(Suppl 1):45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1996) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Natl Inst Health, Bethesda), DHHS Publ No (NIH) 85–23.

- 33.Mistry AM, et al. Strain- and age-dependent hippocampal neuron sodium currents correlate with epilepsy severity in Dravet syndrome mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;65:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lossin C, Wang DW, Rhodes TH, Vanoye CG, George AL., Jr Molecular basis of an inherited epilepsy. Neuron. 2002;34(6):877–884. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00714-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhodes TH, Lossin C, Vanoye CG, Wang DW, George AL., Jr Noninactivating voltage-gated sodium channels in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(30):11147–11152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402482101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kahlig KM, et al. Divergent sodium channel defects in familial hemiplegic migraine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(28):9799–9804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711717105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson CH, Kahlig KM, George AL., Jr SCN1A splice variants exhibit divergent sensitivity to commonly used antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 2011;52(5):1000–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]