Abstract

Purpose

The Sunbelt Melanoma Trial is a prospective randomized trial evaluating the role of high-dose interferon alfa-2b therapy (HDI) or completion lymph node dissection (CLND) for patients with melanoma staged by sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy.

Patients and Methods

Patients were eligible if they were age 18 to 70 years with primary cutaneous melanoma ≥ 1.0 mm Breslow thickness and underwent SLN biopsy. In Protocol A, patients with a single tumor-positive lymph node after SLN biopsy underwent CLND and were randomly assigned to observation versus HDI. In Protocol B, patients with tumor-negative SLN by standard histopathology and immunohistochemistry underwent molecular staging by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Patients positive by RT-PCR were randomly assigned to observation versus CLND versus CLND+HDI. Primary end points were disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS).

Results

In the Protocol A intention-to-treat analysis, there were no significant differences in DFS (hazard ratio, 0.82; P = .45) or OS (hazard ratio, 1.10; P = .68) for patients randomly assigned to HDI versus observation. In the Protocol B intention-to-treat analysis, there were no significant differences in overall DFS (P = .069) or OS (P = .77) across the three randomized treatment arms. Similarly, efficacy analysis (excluding patients who did not receive the assigned treatment) did not demonstrate significant differences in DFS or OS in Protocol A or Protocol B. Median follow-up time was 71 months.

Conclusion

No survival benefit for adjuvant HDI in patients with a single positive SLN was found. Among patients with tumor-negative SLN by conventional pathology but with melanoma detected in the SLN by RT-PCR, there was no OS benefit for CLND or CLND+HDI.

INTRODUCTION

The year 1996 was a landmark year in the field of melanoma. Balch et al1 published the results of the Intergroup Melanoma Trial, suggesting that some populations of patients with melanoma may benefit from elective lymph node dissection. Also in 1996, reports indicated that molecular staging of sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs) by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) detection of melanoma-specific mRNA could identify a high-risk population of patients with stage I or II melanoma who had tumor-negative SLNs by conventional hematoxylin and eosin (HE) histopathology and immunohistochemistry (IHC).2 Furthermore, the results of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) E1684 trial were published.3 This study, in which several groups of patients with high-risk melanoma were randomly assigned to observation versus high-dose interferon alfa-2b (HDI) adjuvant therapy, demonstrated that HDI therapy resulted in improved disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS).

Several interesting observations emerged from this study. First, this trial was heavily weighted toward patients with metachronous lymph node metastasis after prior wide local excision of the primary tumor (174 patients, 62%). This subgroup demonstrated the least improvement in DFS. In addition, 31 patients (11%) had thick primary melanomas with pathologically negative lymph nodes. This group demonstrated a trend toward worse DFS for HDI-treated patients, although this was not statistically significant. Overall, 73% of the patients enrolled in this trial consisted of subsets of patients who showed little or no benefit from treatment. The greatest reduction of hazard of relapse and death was demonstrated in patients with nonpalpable lymph node metastasis detected at elective lymph node dissection and in patients with palpable lymph nodes synchronous with the primary tumor. This suggested that adjuvant HDI therapy might have the greatest benefit for patients with early nodal metastatic disease. However, it was not possible to draw firm conclusions regarding the efficacy of HDI for patients with early (microscopic) lymph node metastases, given the small number of patients studied.

On the basis of this trial, HDI received US Food and Drug Administration approval for adjuvant therapy of patients with high-risk melanoma. However, HDI is expensive and has significant toxicity, including constitutional adverse effects, myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity, and neuropsychiatric adverse effects.3 Overall, 67% of all patients in ECOG E1684 had severe (grade 3) toxicity at some point during the year of treatment, 9% had life-threatening toxicity, and two had lethal hepatic toxicity. Dose delays and/or reductions due to toxicity were required in 37% of patients during induction therapy and in 36% of patients during maintenance therapy.

The convergence of these studies in 1996 provided the impetus for the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial, which was designed the same year and enrolled its first patient in 1997. The impact of adjuvant HDI on patients with minimal nodal tumor burden was unknown, the benefit of early lymphadenectomy in some subgroups of patients was untested, and the RT-PCR molecular staging of SLNs was promising. The following hypotheses were developed:

HDI therapy improves DFS and OS for patients with minimal nodal tumor burden, for example, those with a single tumor-positive SLN detected by HE staining or IHC.

Completion lymph node dissection (CLND) improves DFS and OS for patients with stage I or II melanoma in whom SLNs are tumor-negative by HE staining and IHC but demonstrate molecular evidence of melanoma cells by RT-PCR analysis.

HDI therapy improves DFS and OS for patients with stage I or II melanoma in whom SLNs are tumor-negative by HE staining and IHC but demonstrate molecular evidence of melanoma cells by RT-PCR analysis.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The Sunbelt Melanoma Trial is a prospective, randomized trial involving 70 centers in North America. The Institutional Review Board of each participating institution approved this study. An independent data safety and monitoring board provided oversight for the study and approved the final analysis. Patients age 18 to 70 years with cutaneous melanoma ≥ 1 mm Breslow thickness and without clinical evidence of regional or distant metastasis were eligible. After providing informed consent, patients were registered and underwent wide local excision of the primary melanoma and SLN biopsy with peritumoral intradermal injection of technetium 99mTc-sulfur colloid; intradermal isosulfan blue dye was also used in the majority of cases. All patients underwent wide local excision of the primary melanoma and SLN biopsy. The procedural details of the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial have been previously described, as have the results of the RT-PCR staging study.4,5 SLNs were evaluated by serial sectioning (at least five sections per block) with HE staining and IHC for S-100 protein. Some institutions also performed IHC for HMB-45, but this was not a requirement per protocol (Data Supplement). A histologically positive SLN was defined as evidence of metastatic tumor cells identified by either HE staining or IHC. A central pathology review committee evaluated the first 10 cases from each participating institution, as well as all cases of tumor-positive SLNs.

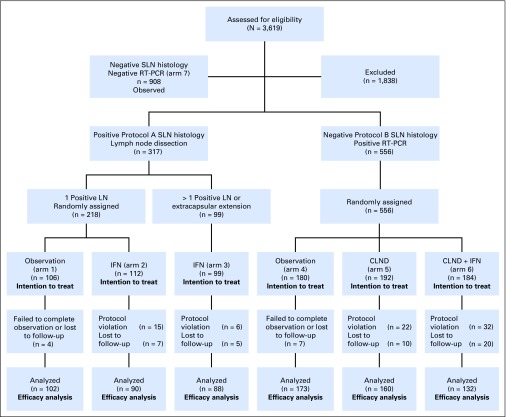

The schema for the trial is shown in Figure 1, and enrollment by center is provided in Appendix Table A1 (online only). Patients with histologically positive SLNs were eligible for enrollment in Protocol A, in which all patients underwent CLND. Patients with only a single tumor-positive SLN were randomly assigned to observation versus HDI therapy (20 million units/m2 intravenously per day, 5 days per week × 4 weeks, followed by 10 million units/m2 subcutaneously three times per week for 48 weeks). Patients with more than one positive lymph node or extracapsular extension of tumor in a lymph node were not randomly assigned but were treated with HDI. Patients with tumor-negative SLNs by standard HE and IHC underwent molecular staging of the SLN by RT-PCR with Southern blot detection of melanoma-specific mRNA (tyrosinase, melanoma antigen recognized by T cells-1 [MART-1], melanoma-associated antigen [MAGE], glycoprotein 100 [gp100]); patients were considered PCR positive if tyrosinase plus at least one other marker were detected.6-8 Patients with RT-PCR–positive but HE- and IHC-negative SLNs were considered to have molecular evidence of nodal metastasis and were eligible for Protocol B, in which they were randomly assigned to observation versus CLND versus CLND+HDI. In the year 1999, Protocol B was amended to administering 1 month of high-dose interferon (IFN) therapy only (20 million units/m2 intravenously per day, 5 days per week, for 4 weeks) without the additional 11-month subcutaneous injection treatment. These changes affected patients randomly assigned to arm 6: 46 patients (25%) were randomly assigned to the 1-month treatment plus an additional 11 months, whereas 138 patients were randomly assigned to the 1-month treatment only. Patients with histologically negative, RT-PCR–negative SLNs were not randomly assigned but were followed longitudinally. Some patients were registered in the study prior to SLN biopsy but did not proceed to randomization.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of enrollment and randomization in the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial. IFN, interferon; LN, lymph node; CLND, completion lymph node dissection; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; SLN, sentinel lymph node.

Block randomization in Protocols A and B was stratified by Breslow thickness category (1.0 to 2.0, > 2.0 to 4.0, and > 4.0 mm) and the presence or absence of primary tumor ulceration. In both Protocols A and B, enrollment targets were 150 patients in each group, which would provide 80% power to detect a 15% absolute difference in OS and DFS at 7 years. The anticipated enrollment in the trial to meet these sample size goals would be 1,370 patients. Intention-to-treat and efficacy analyses were performed.

Patients were included in the efficacy analysis if they accepted their assigned treatment and underwent CLND, if so assigned, and received at least one dose of HDI, if so assigned. The primary outcome was OS; the secondary outcome was DFS. Survival was calculated from the time of SLN biopsy to death as a result of any cause (OS) or from the time of SLN biopsy to documented recurrence of melanoma at any site (DFS). Survival times were compared by using Kaplan-Meier analysis and the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios [HRs]. All tests were two-sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with JMP software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

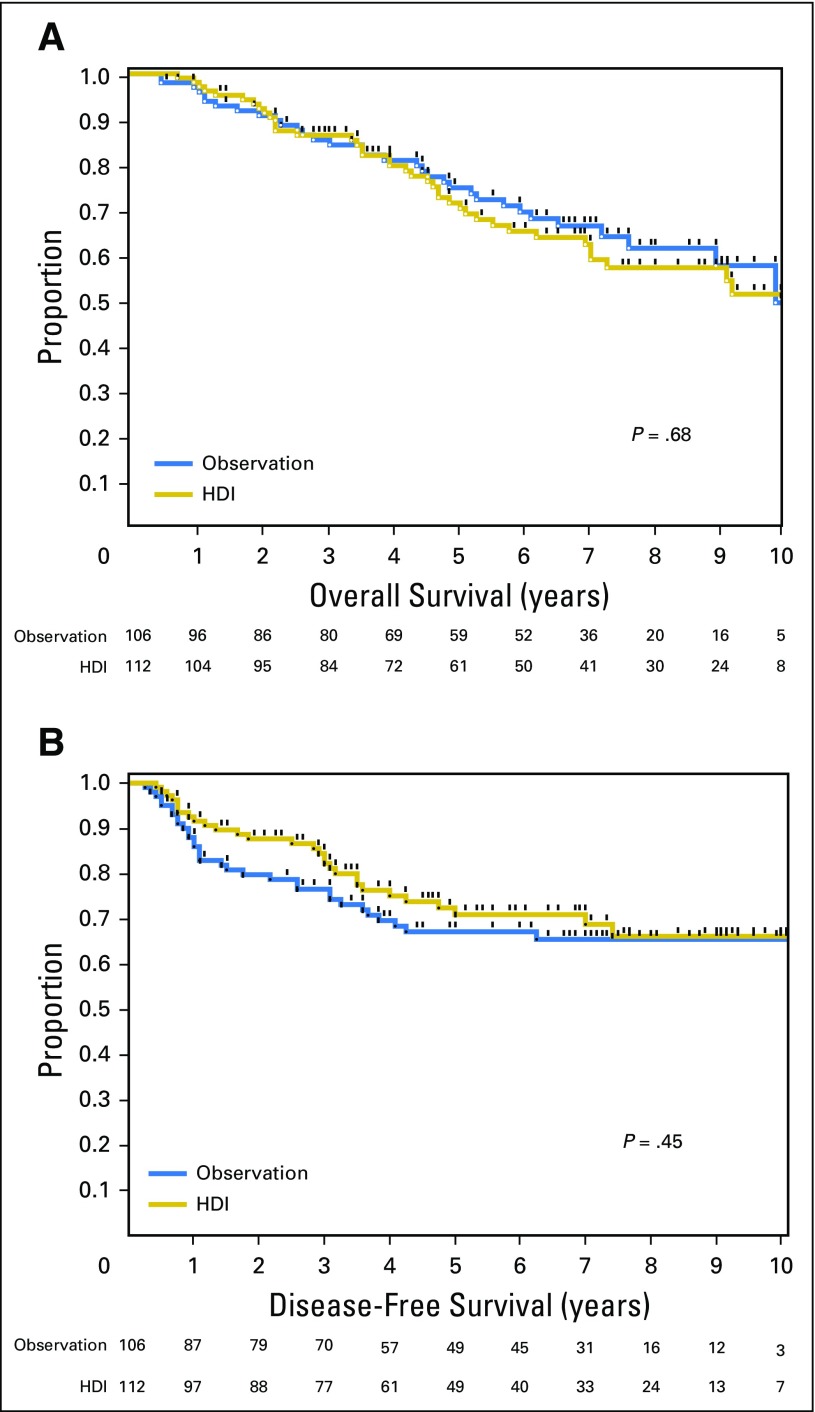

Patients were enrolled between June 1997 and October 2003. The median follow-up period was 71 months. A total of 218 patients were randomly assigned to Protocol A and 556 were assigned to Protocol B. The randomly assigned groups were well balanced in terms of major clinicopathologic risk factors in both protocols (Tables 1 and 2). In the Protocol A analysis, there were no overall significant differences in DFS (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.50 to 1.36; P = .45) or OS (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.69 to 1.76; P = 0.68) for patients randomly assigned to HDI versus observation (Fig 2). In patients with a single positive SLNs, 5-year OS was 74.8% in the observation group and 71.4% in the HDI group, whereas 5-year DFS was 67.1% in the observation group and 70.9% in the HDI group. In Protocol A, 10.4% of patients in the observation group and 17.0% of patients in the HDI group died prior to disease recurrence. HDI after CLND in patients with a single positive SLN did not offer a survival benefit compared with observation alone after CLND.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic Factors in the Observation (arm 1) Versus HDI (arm 2) Treatment Groups After CLND in Patients With a Single Positive Sentinel Lymph Node (Protocol A)

| Clinicopathologic Factors | Arm 1, Observation No. (%) | Arm 2, HDI No. (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 60 (56.6) | 60 (53.6) | .65 |

| Median age, years (interquartile range) | 49 (39-56.25) | 46 (40-56.75) | .28 |

| Median Breslow thickness, mm (interquartile range) | 1.96 (1.37-3.18) | 2.10 (1.60-3.64) | .26 |

| Clark level | |||

| II, III | 22 (21.4) | 17 (15.7) | .29 |

| IV, V | 81 (78.6) | 91 (84.3) | |

| Histologic subtype | |||

| Superficial spreading | 47 (46.1) | 51 (47.7) | .82 |

| Other | 55 (53.9) | 56 (52.3) | |

| Ulceration present | 36 (34.0) | 39 (35.1) | .86 |

| Lymphovascular invasion present | 15 (16.0) | 10 (9.9) | .21 |

| Regression present | 12 (13.0) | 10 (10.1) | .52 |

| Anatomic site | |||

| Extremity | 39 (36.8) | 44 (39.3) | .82 |

| Trunk | 60 (56.6) | 59 (52.7) | |

| Head/neck | 7 (6.6) | 9 (8.0) |

Abbreviations: CLND, completion lymph node dissection; HDI, high-dose interferon alfa-2b.

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic Factors in the Observation (arm 4), CLND (arm 5), or CLND+HDI (arm 6) Treatment Arms in Patients With RT-PCR–Positive Sentinel Lymph Nodes Only (Protocol B)

| Clinicopathologic Factors | Arm 4 Observation No. (%) | Arm 5 CLND No. (%) | Arm 6 CLND+IFN No. (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 108 (60.3) | 106 (55.5) | 84 (45.7) | .0165 |

| Median age, years (interquartile range) | 51.5 (41-59) | 50 (42-59) | 49 (38-57) | .57 |

| Median Breslow thickness, mm (interquartile range) | 1.55 (1.20-2.20) | 1.59 (1.20-2.50) | 1.47 (1.13-2.00) | .07 |

| Clark level | ||||

| II, III | 52 (29.5) | 48 (25.8) | 52 (29.0) | .69 |

| IV, V | 124 (70.5) | 138 (74.2) | 127 (71.0) | |

| Histologic subtype | ||||

| Superficial spreading | 97 (56.4) | 94 (51.1) | 101 (57.1) | .46 |

| Other | 75 (43.6) | 90 (48.9) | 76 (42.9) | |

| Ulceration present | 43 (24.2) | 45 (23.7) | 39 (21.2) | .77 |

| Lymphovascular invasion present | 7 (4.4) | 18 (10.4) | 9 (5.5) | .06 |

| Regression present | 13 (7.9) | 19 (11.3) | 21 (13.0) | .32 |

| Anatomic site | ||||

| Extremity | 78 (43.6) | 94 (49.5) | 80 (43.5) | .46 |

| Trunk | 75 (41.9) | 79 (41.6) | 82 (44.6) | |

| Head/neck | 26 (14.5) | 17 (8.9) | 22 (12.0) |

Abbreviations: CLND, completion lymph node dissection; HDI, high-dose interferon alfa-2b; IFN, interferon.

Fig 2.

Comparison of overall survival (A) and disease-free survival (B) in patients with a single positive sentinel lymph node randomly assigned to high-dose interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy (HDI) or observation.

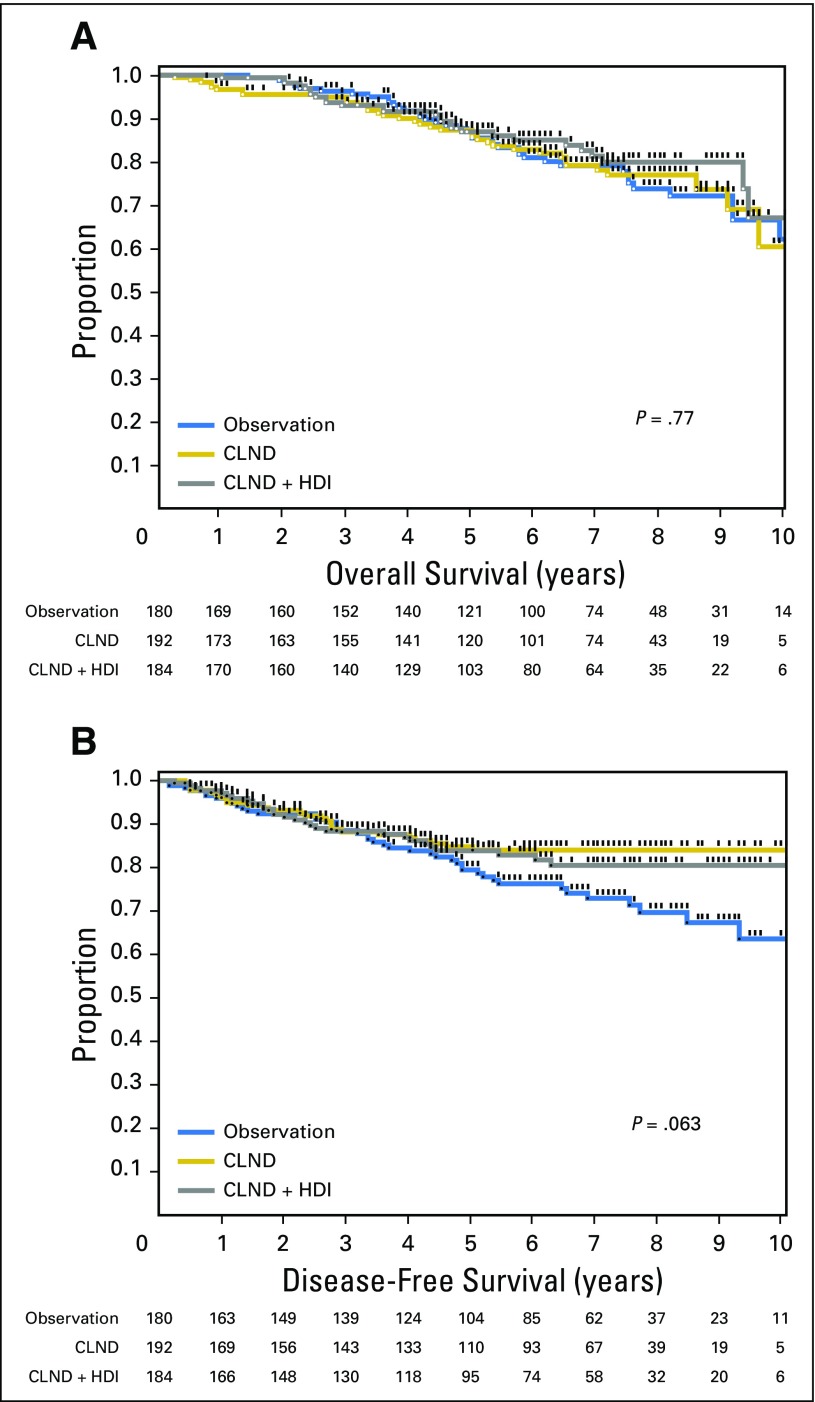

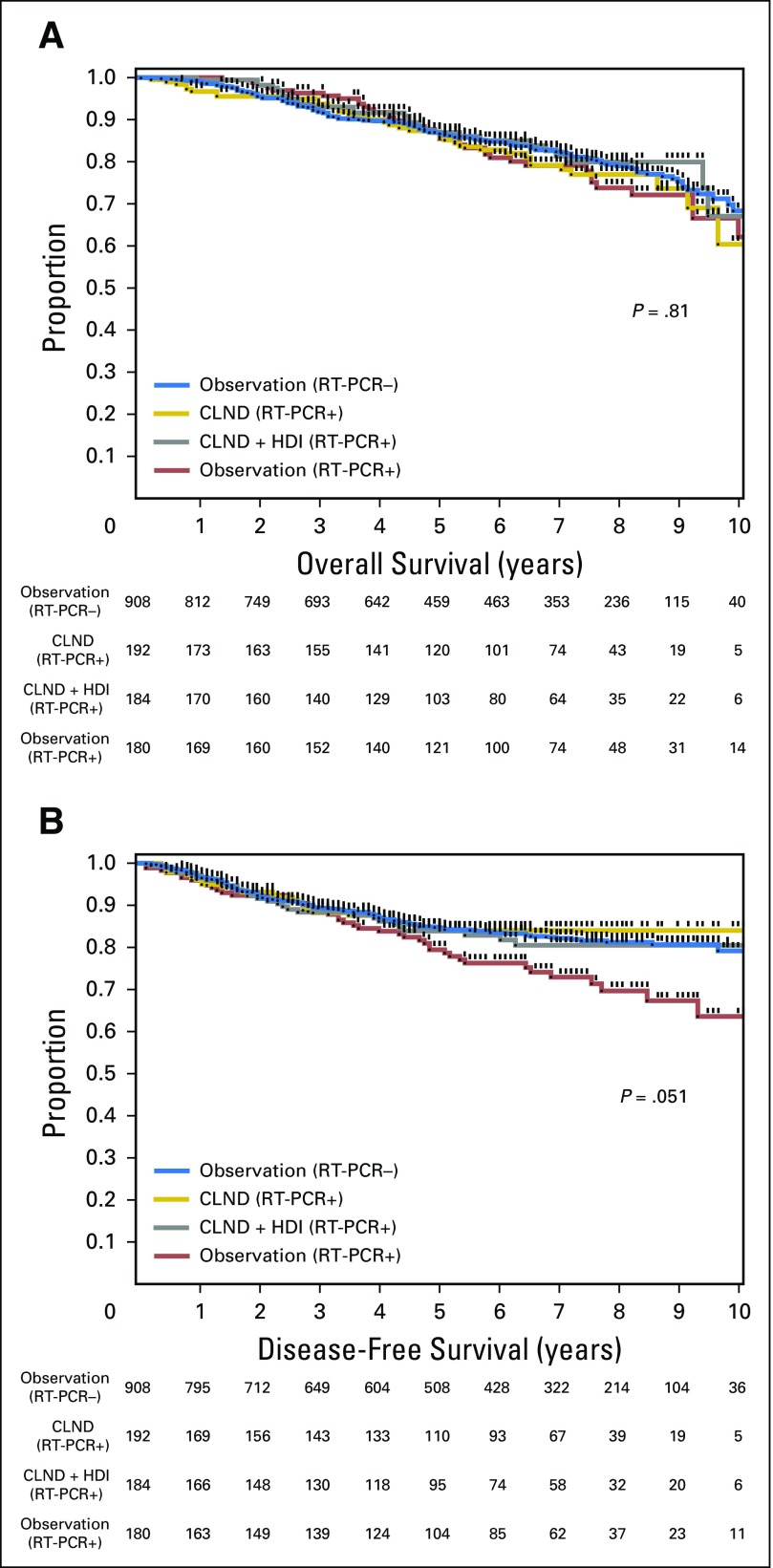

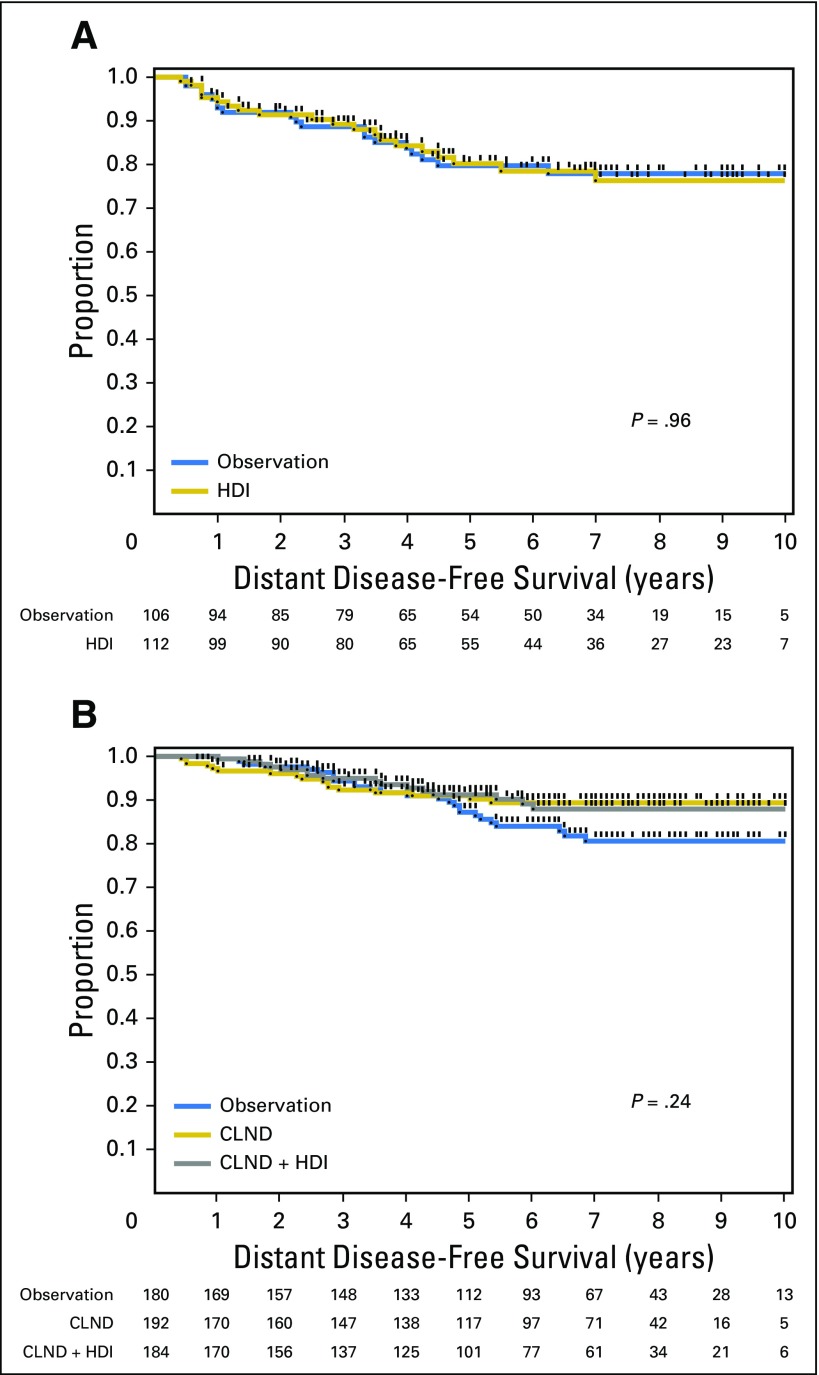

In the Protocol B analysis, there were no overall significant differences in DFS (P = .069) or OS (P = .77) among patients randomly assigned to CLND or CLND+IFN (Fig 3). When individually compared with observation, CLND alone was associated with an improvement in DFS (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.94; P = .0277), but not OS (HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.634 to 1.59; P = .99), whereas CLND+IFN was not associated with a significant difference in DFS (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.42 to 1.09; P = .11) or OS (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.52 to 1.40; P = .55) versus observation. In patients with negative SLNs by routine HE and IHC, 5-year OS was 85.5% in the observation group, 85.9% in the CLND group, and 86.9% in the CLND+HDI group. Five-year DFS was 79.4% in the observation group, 84.0% in the CLND group, and 83.9% in the CLND+IFN group. In Protocol B, 7.2%, 8.9%, and 4.4% of patients in the observation, CLND, and CLND+HDI groups died prior to disease recurrence. We have previously reported that SLN RT-PCR analysis under conditions and definitions used in this study did not predict a worse prognosis; patients with RT-PCR–negative and RT-PCR–positive SLNs had similar DFS and OS.5 Therefore, the randomization in Protocol B can be considered to be a comparison of observation versus CLND versus CLND+IFN in SLN-negative (stage I and II) patients. By including patients in the observation arm (arm 7) who were RT-PCR negative, one can see there is no difference in DFS or OS (Fig 4). There were no significant differences in distant DFS in either Protocol A or B (Appendix Fig A1).

Fig 3.

Comparison of (A) overall survival and (B) disease-free survival in patients with a sentinel lymph node positive by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction only randomly assigned to observation, completion lymph node dissection (CLND), or CLND plus high-dose interferon alfa-2b (HDI) adjuvant therapy.

Fig 4.

Comparison of (A) overall survival and (B) disease-free survival in patients with sentinel lymph nodes positive by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR+) only randomly assigned to observation, completion lymph node dissection (CLND), or CLND plus high-dose interferon alfa-2b (HDI) adjuvant therapy, while including patients with negative sentinel lymph nodes by RT-PCR−.

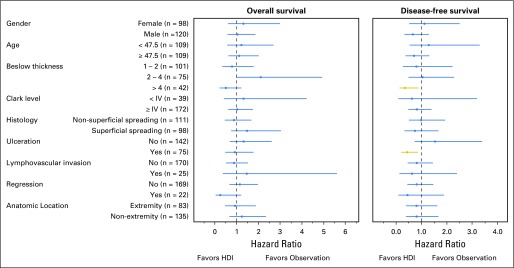

In Protocol A, the nonrandomized group with more than one positive lymph node or extracapsular extension of tumor in a lymph node who received HDI did poorly, despite HDI therapy; 5-year DFS was 44.2%, and 5-year OS was 53.4%. Subgroup analysis was performed to identify any particular groups that may benefit from HDI in Protocol A (Fig 5). In patients with a single positive SLN, HDI was associated with an improvement in DFS only in patients with ulceration (HR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.21 to 0.87; P = .0183; n = 75)9 and with Breslow thickness more than 4 mm (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.14 to 0.88; P = .0259; n = 42). No improvement in OS was seen in these or other high-risk groups. Efficacy analysis (excluding patients who did not receive the assigned treatment) did not demonstrate significant differences in DFS or OS in Protocol A or Protocol B. For both Protocols A and B, a competing risk model was analyzed for DFS by using death prior to recurrence as a competing risk. There remained no significant differences in DFS for Protocol A (P = .62) or B (P = .07) across treatment arms.

Fig 5.

Subgroup analysis of Protocol A, examining differences in disease-free and overall survival in patients with a single positive sentinel lymph node randomly assigned to high-dose interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy (HDI) or observation.

DISCUSSION

The most important finding in this trial was that adjuvant HDI did not improve survival in patients with a single tumor-positive SLN. No survival advantage was found in RT-PCR–positive patients treated with CLND or CLND+HDI compared with observation alone. EGOG directed three major intergroup trials: ECOG E1684, ECOG E1690, and ECOG E1694. In ECOG E1684, HDI was shown to improve both DFS and OS in a high-risk melanoma population comprising principally patients with palpable nodal disease (in an era prior to the advent of SLN biopsy).3 The second, larger study, ECOG E1690, in which HDI for 1 year was compared with low-dose IFN for 2 years or observation in stage IIB and III melanoma, revealed a borderline DFS advantage for HDI, with no improvement in OS.10 The third study, ECOG E1694, was stopped early by the data safety and monitoring board because of superiority of the HDI-treated group versus those treated with a ganglioside vaccine (GMK).11 In the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 18961 trial, this same GMK vaccine was subsequently shown to have a significantly detrimental effect on DFS and OS compared with observation.12 The results of this study refute the conclusion that improved DFS and OS in ECOG E1694 was due to a beneficial effect of HDI because HDI treatment in ECOG E1694 was not compared with observation or placebo, but to a vaccine that is now known to be associated with a greater risk of recurrence and mortality. Although, admittedly, the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial was not adequately powered to detect small differences in DFS or OS and did not meet its accrual goals, there was no trend toward improvement in OS for patients treated with HDI. Therefore, only a single randomized trial of HDI, ECOG E1684, which began accrual in 1984, has shown convincing and statistically significant improvement in DFS and OS. These conflicting data, along with the substantial toxicity and cost associated with adjuvant HDI therapy, have done little to quell the ongoing controversy.

Several studies have evaluated other dosing regimens of IFN, including low and intermediate doses, as well as a pegylated formulation of IFN alfa-2b. A recent meta-analysis of these studies showed that IFN is associated with a significant improvement in DFS, as well as a small improvement in OS (approximately 3% absolute OS advantage; number needed to treat, 29).13 However, this meta-analysis included ECOG E1694, which would now likely be considered inappropriate for inclusion because the GMK vaccine is not equivalent to observation or placebo and did not include the results of the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial, which showed no improvement or trend for improvement in OS associated with HDI treatment. Taken together, these data support the conclusion that the benefit of HDI is small, perhaps because only a fraction of the patient population responds to the therapy.

Survival in Protocol A was similar to the recently published final results of the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial 1 (MSLT-1).14 In the MSLT-1 trial, 5-year OS ranged from 67% to 86% in thick and intermediate-thickness melanoma, with associated 5-year DFS ranging from 43% to 77%. These rates are similar to the results of the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial, in which patients with a single tumor-positive SLN had 5-year OS rates of 71.4% and 74.8%, and 5-year DFS rates of 67.1% and 70.9% in patients with Breslow thickness more than 1.0 mm.

Post hoc subgroup analysis of EORTC 18952 and EORTC 18991 trials demonstrated that, among patients with stage IIB and III (microscopic nodal metastases) melanoma, ulceration is an important predictor of response to HDI. HDI treatment in patients with ulcerated melanomas, but not those with nonulcerated melanomas, was shown to be associated with improved OS.15 The results of this study support this hypothesis by showing that ulceration predicted improved DFS among patients treated with HDI. The favorable effect of HDI on patients with ulcerated primary melanomas in this study has been studied closely and reported by our group previously; we found that this effect was most pronounced and statistically significant among SLN-positive patients with ulcerated melanomas.9 In contrast to the larger EORTC trials, however, we did not find that IFN treatment was associated with improved OS among patients with ulcerated primaries. This limited cohort of 75 patients with high-risk, ulcerated primary tumors is a limitation of this study; perhaps a larger sample size would result in discrimination of a significant difference in OS as well. Subgroup analysis also demonstrated that HDI appeared to have a significant improvement in DFS for thicker (> 4.0 mm) melanoma. This finding parallels the finding of HDI benefit in patients with ulcerated melanomas. There may be a role for HDI in select, high-risk patients with unfavorable primary tumor characteristics, such as ulceration or high Breslow thickness, but the effect on OS may be limited.

Molecular staging by RT-PCR, as performed in this study, had no prognostic significance and did not identify patients with high-risk stage I or II melanoma. However, there does appear to be a trend toward improved DFS in the two CLND treatment arms compared with observation, most notably after 5 years of observation. Subgroup analysis does indeed suggest that there is a DFS benefit in patients with RT-PCR–positive SLNs who undergo CLND compared with observation (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.94; P = .0277). This may simply reflect a decrease in regional nodal recurrence as a result of CLND that does not translate into an OS advantage.

The limitations of the study need to be considered. The Sunbelt Melanoma Trial partially met its accrual goals. In Protocol A, only 106 and 112 patients were randomly assigned in arms 1 and 2, respectively, rather than the stated goal of 150. The rate of positive SLNs and entry into Protocol A was 17.8%. This is much lower than the anticipated rate of SLN positivity and entry into Protocol A, which was expected to be approximately 34% in our pretrial planning. The trial actually exceeded intended enrollment, which was 1,370 patients enrolled in arms 1 to 7. Total accrual was 1,781 patients.

Because of the lower rate of SLN positivity, more patients were placed in Protocol B or observed because they were RT-PCR negative (arm 7). Thus, Protocol A did not meet its accrual goals, whereas Protocol B and the observation arm exceeded them. The HDI treatment protocol in the RT-PCR–positive arm (arm 6) was altered one fourth of the way through the trial, because results from ECOG E1690 were published, suggesting limited benefit in patients with high-risk disease.10 This caused trial investigators to reconsider a taxing, 11-month treatment regimen in what was already recognized as a low-risk patient population.

In conclusion, the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial did not identify a DFS or OS advantage for adjuvant HDI in patients with a single tumor-positive SLN. In patients who have tumor-negative SLNs by routine HE and IHC, there is no survival benefit offered by CLND or adjuvant HDI compared with observation alone, although CLND may slightly improve locoregional disease control.

Acknowledgment

For a list of participating investigators, see Data Supplement.

We thank Deborah Hulsewede and Ivan Deyahs for data management, and Sherri Matthews for regulatory oversight, as well as members of the Central Pathology Review Committee (Martin Mihm, MD; Jane Messina, MD; Frank Glass, MD; and Victor Prieto, MD, PhD) and the Data Safety and Monitoring Board (Vernon Sondak, MD; Lawrence Flaherty, MD; and Troy Abell, PhD).

Presented at the 44th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, May 30-June 3, 2008.

Appendix

Fig A1.

Comparison of distant disease-free survival (A) in patients with a single positive sentinel lymph node randomly assigned to high-dose interferon alfa-2b (HDI) adjuvant therapy or observation and (B) in patients with a sentinel lymph node positive by RT-PCR only randomly assigned to observation, completion lymph node dissection (CLND), or CLND+HDI.

Table A1.

Number of Patients Randomly Assigned to Treatment Arms in the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial at Each Participating Site

| Center Identification No. | Intention to Treat Enrollment | Efficacy Enrollment |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 175 | 163 |

| 1 | 115 | 109 |

| 40 | 98 | 91 |

| 25 | 94 | 78 |

| 3 | 91 | 80 |

| 84 | 85 | 70 |

| 75 | 82 | 80 |

| 66 | 72 | 69 |

| 21 | 52 | 50 |

| 20 | 40 | 35 |

| 63 | 39 | 38 |

| 19 | 36 | 31 |

| 12 | 35 | 31 |

| 26 | 33 | 27 |

| 10 | 32 | 28 |

| 8 | 29 | 26 |

| 36 | 29 | 29 |

| 64 | 29 | 24 |

| 62 | 27 | 26 |

| 11 | 26 | 22 |

| 44 | 26 | 26 |

| 29 | 25 | 22 |

| 5 | 24 | 23 |

| 28 | 24 | 18 |

| 87 | 24 | 21 |

| 35 | 22 | 22 |

| 98 | 22 | 17 |

| 31 | 21 | 17 |

| 13 | 20 | 16 |

| 60 | 19 | 18 |

| 88 | 17 | 16 |

| 94 | 17 | 17 |

| 14 | 16 | 16 |

| 17 | 16 | 12 |

| 86 | 16 | 13 |

| 9 | 15 | 15 |

| 27 | 14 | 13 |

| 37 | 13 | 12 |

| 41 | 13 | 13 |

| 73 | 13 | 13 |

| 4 | 12 | 11 |

| 18 | 12 | 7 |

| 43 | 12 | 11 |

| 6 | 11 | 10 |

| 16 | 11 | 8 |

| 24 | 11 | 11 |

| 74 | 10 | 10 |

| 78 | 10 | 7 |

| 96 | 10 | 9 |

| 57 | 8 | 8 |

| 67 | 8 | 7 |

| 92 | 8 | 2 |

| 97 | 8 | 7 |

| 39 | 7 | 6 |

| 91 | 7 | 6 |

| 32 | 5 | 5 |

| 45 | 5 | 4 |

| 38 | 4 | 4 |

| 48 | 4 | 4 |

| 89 | 4 | 3 |

| 85 | 3 | 3 |

| 7 | 2 | 2 |

| 15 | 2 | 2 |

| 34 | 2 | 2 |

| 46 | 2 | 2 |

| 82 | 2 | 2 |

| 99 | 2 | 1 |

| 30 | 1 | 1 |

| 42 | 1 | 1 |

| 68 | 1 | 1 |

Footnotes

Listen to the podcast by Dr Balch at www.jco.org/podcasts

Funded by a grant from Schering Oncology Biotech.

Support information appears at the end of this article.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Kelly M. McMasters, Michael J. Edwards, Merrick I. Ross, Douglas S. Reintgen, Marshall M. Urist

Financial support: Kelly M. McMasters

Administrative support: Kelly M. McMasters, Merrick I. Ross

Provision of study materials or patients: Kelly M. McMasters, Merrick I. Ross, Douglas S. Reintgen, R. Dirk Noyes, Jeffrey E. Gershenwald

Collection and assembly of data: Michael E. Egger, Douglas S. Reintgen, R. Dirk Noyes, Robert C.G. Martin II, James S. Goydos, Peter D. Beitsch, Marshall M. Urist, Stephan Ariyan, Jeffrey J. Sussman, B. Scott Davidson, Jeffrey E. Gershenwald, Lee J. Hagendoorn

Data analysis and interpretation: Michael E. Egger, Douglas S. Reintgen, Jeffrey E. Gershenwald, Lee J. Hagendoorn, Arnold J. Stromberg, Charles R. Scoggins

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Final Results of the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial: A Multi-Institutional Prospective Randomized Phase III Study Evaluating the Role of Adjuvant High-Dose Interferon Alfa-2b and Completion Lymph Node Dissection for Patients Staged by Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Kelly M. McMasters

Leadership: Provectus Biopharmaceuticals

Stock or Other Ownership: Provectus Biopharmaceuticals

Michael E. Egger

No relationship to disclose

Michael J. Edwards

No relationship to disclose

Merrick I. Ross

Leadership: Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck

Honoraria: Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Neostem, Novartis, Amgen, Provectus Biopharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline

Speakers' Bureau: Merck, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Neostem

Research Funding: Amgen, Neostem, Provectus Biopharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Merck, Amgen, Neostem, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Douglas S. Reintgen

No relationship to disclose

R. Dirk Noyes

No relationship to disclose

Robert C.G. Martin II

Consulting or Advisory Role: Angiodynamics

James S. Goydos

No relationship to disclose

Peter D. Beitsch

No relationship to disclose

Marshall M. Urist

Consulting or Advisory Role: Myriad Genetics

Stephan Ariyan

Employment: Pfizer (I)

Leadership: Pfizer (I)

Stock or Other Ownership: Pfizer (I)

Jeffrey J. Sussman

Honoraria: Castle Biosciences

Consulting or Advisory Role: Castle Biosciences

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Elsevier

B. Scott Davidson

No relationship to disclose

Jeffrey E. Gershenwald

Consulting or Advisory Role: Castle Biosciences, Merck

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Mercator Therapeutics

Lee J. Hagendoorn

Employment: Advertek

Leadership: Advertek

Stock or Other Ownership: Advertek

Consulting or Advisory Role: Advertek

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Advertek

Arnold J. Stromberg

No relationship to disclose

Charles R. Scoggins

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Balch CM, Soong SJ, Bartolucci AA, et al. Efficacy of an elective regional lymph node dissection of 1 to 4 mm thick melanomas for patients 60 years of age and younger. Ann Surg. 1996;224:255–263. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199609000-00002. discussion 263-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van der Velde-Zimmermann D, Roijers JF, Bouwens-Rombouts A, et al. Molecular test for the detection of tumor cells in blood and sentinel nodes of melanoma patients. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:759–764. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirkwood JM, Strawderman MH, Ernstoff MS, et al. Interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma: The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial EST 1684. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:7–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMasters KM, Noyes RD, Reintgen DS, et al. Sunbelt Melanoma Trial Lessons learned from the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial. J Surg Oncol. 2004;86:212–223. doi: 10.1002/jso.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scoggins CR, Ross MI, Reintgen DS, et al. Prospective multi-institutional study of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction for molecular staging of melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2849–2857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellado B, Colomer D, Castel T, et al. Detection of circulating neoplastic cells by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction in malignant melanoma: Association with clinical stage and prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2091–2097. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.7.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miliotes G, Albertini J, Berman C, et al. The tumor biology of melanoma nodal metastases. Am Surg. 1996;62:81–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarantou T, Chi DD, Garrison DA, et al. Melanoma-associated antigens as messenger RNA detection markers for melanoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1371–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMasters KM, Edwards MJ, Ross MI, et al. Ulceration as a predictive marker for response to adjuvant interferon therapy in melanoma. Ann Surg. 2010;252:460–465. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f20bb1. discussion 465-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkwood JM, Ibrahim JG, Sondak VK, et al. High- and low-dose interferon alfa-2b in high-risk melanoma: First analysis of intergroup trial E1690/S9111/C9190. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2444–2458. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkwood JM, Ibrahim JG, Sosman JA, et al. High-dose interferon alfa-2b significantly prolongs relapse-free and overall survival compared with the GM2-KLH/QS-21 vaccine in patients with resected stage IIB-III melanoma: Results of intergroup trial E1694/S9512/C509801. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2370–2380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eggermont AM, Suciu S, Rutkowski P, et al. Adjuvant ganglioside GM2-KLH/QS-21 vaccination versus observation after resection of primary tumor > 1.5 mm in patients with stage II melanoma: Results of the EORTC 18961 randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3831–3837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.9303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mocellin S, Pasquali S, Rossi CR, et al. Interferon alpha adjuvant therapy in patients with high-risk melanoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:493–501. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. MSLT Group Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:599–609. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eggermont AM, Suciu S, Testori A, et al. Ulceration and stage are predictive of interferon efficacy in melanoma: Results of the phase III adjuvant trials EORTC 18952 and EORTC 18991. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]