Abstract

The vertebrate hindbrain includes neural circuits that govern essential functions including breathing, blood pressure and heart rate. Hindbrain circuits also participate in generating rhythmic motor patterns for vocalization. In most tetrapods, sound production is powered by expiration and the circuitry underlying vocalization and respiration must be linked. Perception and arousal are also linked; acoustic features of social communication sounds – e.g. a baby’s cry - can drive autonomic responses. The close links between autonomic functions that are essential for life and vocal expression have been a major in vivo experimental challenge. Xenopus provides an opportunity to address this challenge using an ex vivo preparation: an isolated brain that generates vocal and breathing patterns. The isolated brain allows identification and manipulation of hindbrain vocal circuits as well as their activation by forebrain circuits that receive sensory input, initiate motor patterns and control arousal. Advances in imaging technologies, coupled to the production of Xenopus lines expressing genetically encoded calcium sensors, provide powerful tools for imaging neuronal patterns in the entire fictively behaving brain, a goal of the BRAIN Initiative. Comparisons of neural circuit activity across species with distinctive vocal patterns (comparative neuromics) can identify conserved features, and thereby reveal essential functional components.

Keywords: fictive respiration, vocalization, pattern generation

Introduction

Xenopus has been a highly productive model system for developmental and cell biology (Gurdon and Hopwood, 2012; Wühr et al., 2015). Genomic resources (Pearl et al., 2012) are supporting ongoing efforts in gene regulation and evolution (Furman et al., 2015; Session et al., 2016). Analyses of neural circuits using the isolated Xenopus nervous system (reviewed here), together with emerging technologies for whole brain imaging (Tomer et al., 2015), will significantly advance understanding of how these circuits generate motor patterns. The ex vivo brain generates patterns of nerve activity that match the sound patterns of vocal communication signals (calls) and respiration (Rhodes et al., 2007; Zornik and Kelley, 2008). This fictively behaving preparation provides substantive insights not only into the function of experimentally challenging hindbrain circuits, but also into how those circuits are accessed and coordinated by descending input from forebrain regions that decode social cues (Hall et al., 2013). Hormonally-regulated, sexually differentiated circuit features are maintained ex vivo, facilitating analyses of mechanisms underlying endocrine action (Zornik and Yamaguchi, 2011; Zornik and Kelley, 2011). The ex vivo fictive preparation is accessible across species (Leininger and Kelley, 2013; Leininger et al., 2015) providing insight into how neural circuits are re tuned to generate phylogenetic diversity in vocal patterns. Retuning in response to hormones can also be followed across species with divergent modes of primary sex determination (Roco et al., 2015; Furman and Evans, 2016; Mawaribuchi et al., 2016). This approach (comparative neuromics) provides an important advantage for whole brain imaging studies: the ability to identify conserved and variable features across species in order to tease apart which aspects of a circuit’s activity are essential for its function (Katz, 2016; Gjorgjieva et al., 2016).

Vocal production; hindbrain circuitry

In Xenopus, sound pulses are generated by contraction of paired laryngeal muscles in response to activity on the vocal nerve (Tobias and Kelley, 1987; Yamaguchi and Kelley, 2000). This nerve arises from motor neurons located in nucleus ambiguus (NA) of the hindbrain and includes laryngeal motor neuron and glottal motor neuron axons as well as axons that innervate the heart (Simpson et al., 1986) The glottis gates airflow between the mouth and the lungs through the larynx (respiration) and is closed during sound pulse production (Yager, 1992; Zornik and Kelley, 2008). Thus, in Xenopus, as in most vocal vertebrates (Schmidt and Goller, 2016) sound production is linked to respiration though not powered by expiration.

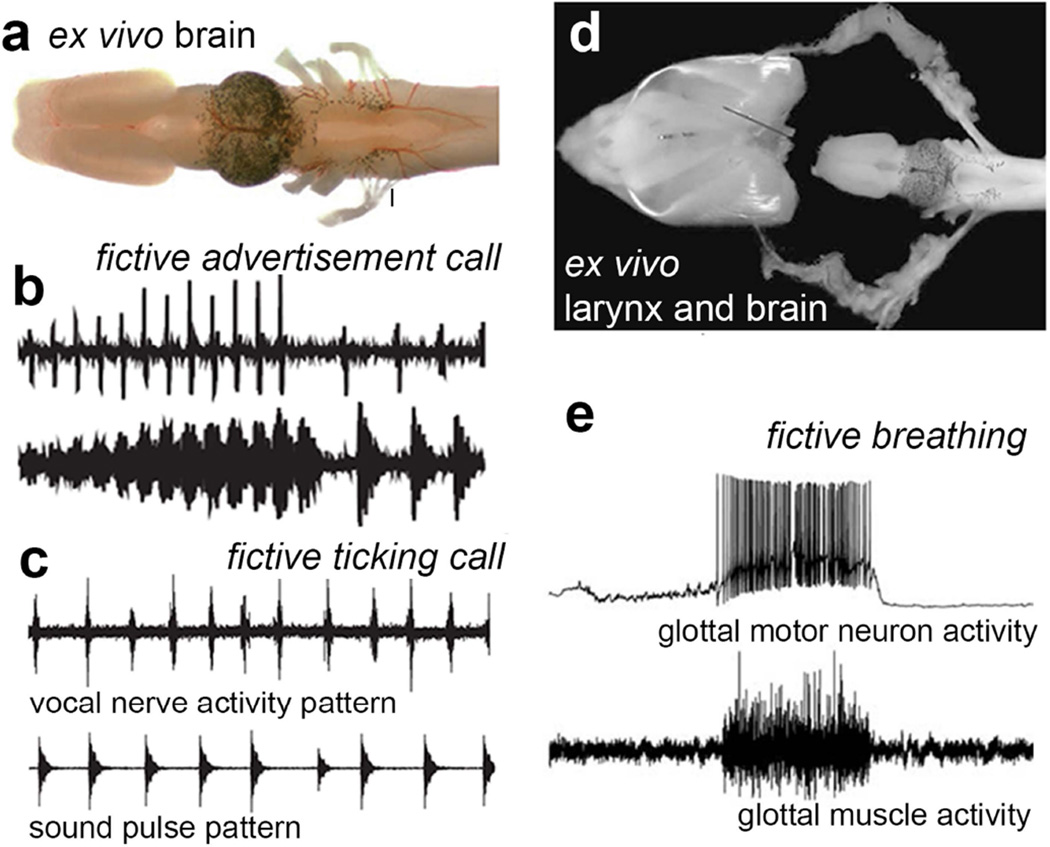

The pattern of vocal nerve activity recorded in vivo matches the pattern of sound pulse production of actual male and female calls (Fig. 1c). These patterns can also be recorded ex vivo (Fig. 2a) from the vocal nerve in an isolated brain and are thus termed fictive calling (Fig. 2b,c). When the larynx and the brain are isolated together (Fig. 2d), glottal muscle activity patterns that accompany contractions can be recorded from glottal motor neurons (Fig. 1e); the corresponding nerve activity patterns are termed fictive breathing. The ex vivo preparation in Xenopus thus provides an exceptional opportunity to study the linkages between neural circuit elements for vocalization and respiration.

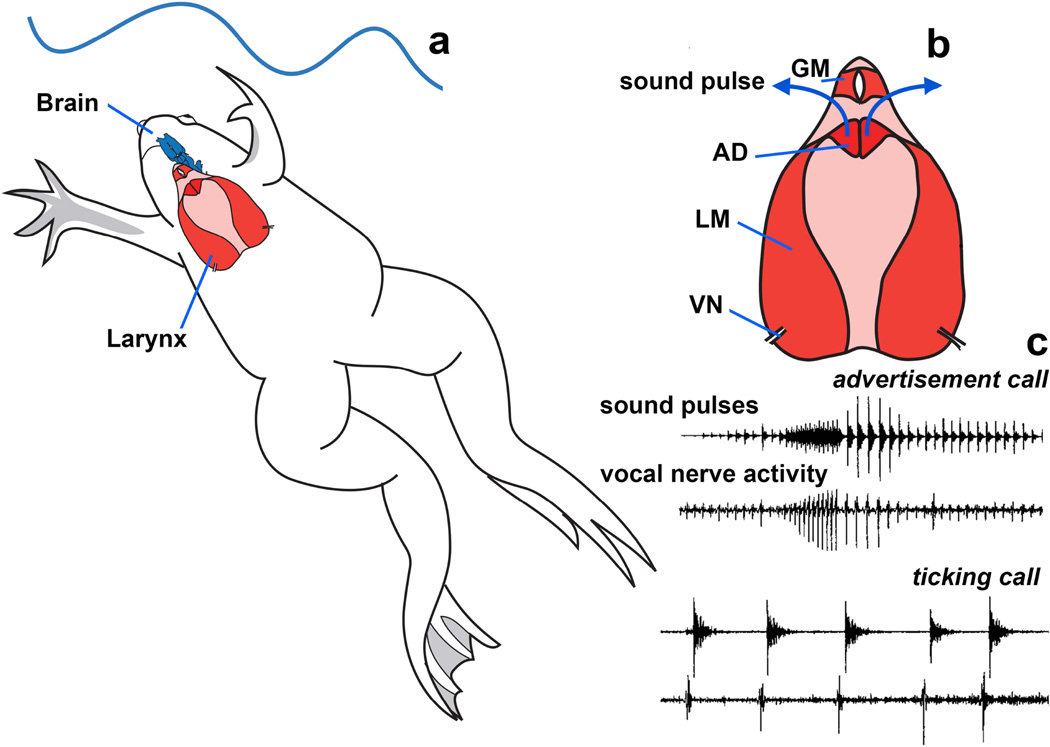

Fig. 1.

Vocal production in Xenopus. a Xenopus call while submerged. b Air travels through the glottis to the lungs. The glottis is closed during vocalization. Each sound pulse is generated by separation of paired arytenoids disks (AD), in response to contraction of laryngeal muscles (LM) driven by activity on the vocal nerve (VN). c Nerve activity patterns (lower traces) match the sexually differentiated patterns of sound pulses (upper traces) in the male advertisement call and the sexually unreceptive female ticking call.

Fig. 2.

Fictive calling and breathing preparations in X. laevis. a The isolated (ex vivo) brain viewed from above (dorsally) from olfactory bulb rostrally (left) to the end of the hindbrain caudally (right). The most caudal rootlet of cranial nerve IX–X (indicated by the line) contains the axons of motor neurons that innervate glottal, laryngeal and heart muscles and comprises the vocal nerve. b Fictive advertisement calling (upper trace) can be recorded from the VN when the neuromodulator serotonin is bath applied to the ex vivo brain. The pattern of VN activity follows the pattern of a male advertisement call (lower trace). c Fictive ticking (upper trace) can be recorded from the VN when the neuromodulator serotonin is bath applied to the ex vivo brain. The pattern of VN activity follows the pattern of female ticking (lower trace). (from Rhodes et al., 2007). d The isolated (ex vivo) brain and innervated larynx viewed from above A branch of cranial nerve IX–X enters the larynx caudally and contains the axons of motor neurons that innervate glottal and laryngeal muscles. e Recordings from glottal muscles (lower panel; also see Fig. 1b) reveal spontaneous bursts of activity that correspond to activity of hindbrain glottal motor neurons. This activity pattern produces the opening of the glottis that allows air to travel from the mouth through the larynx to the lungs and is thus termed fictive breathing.

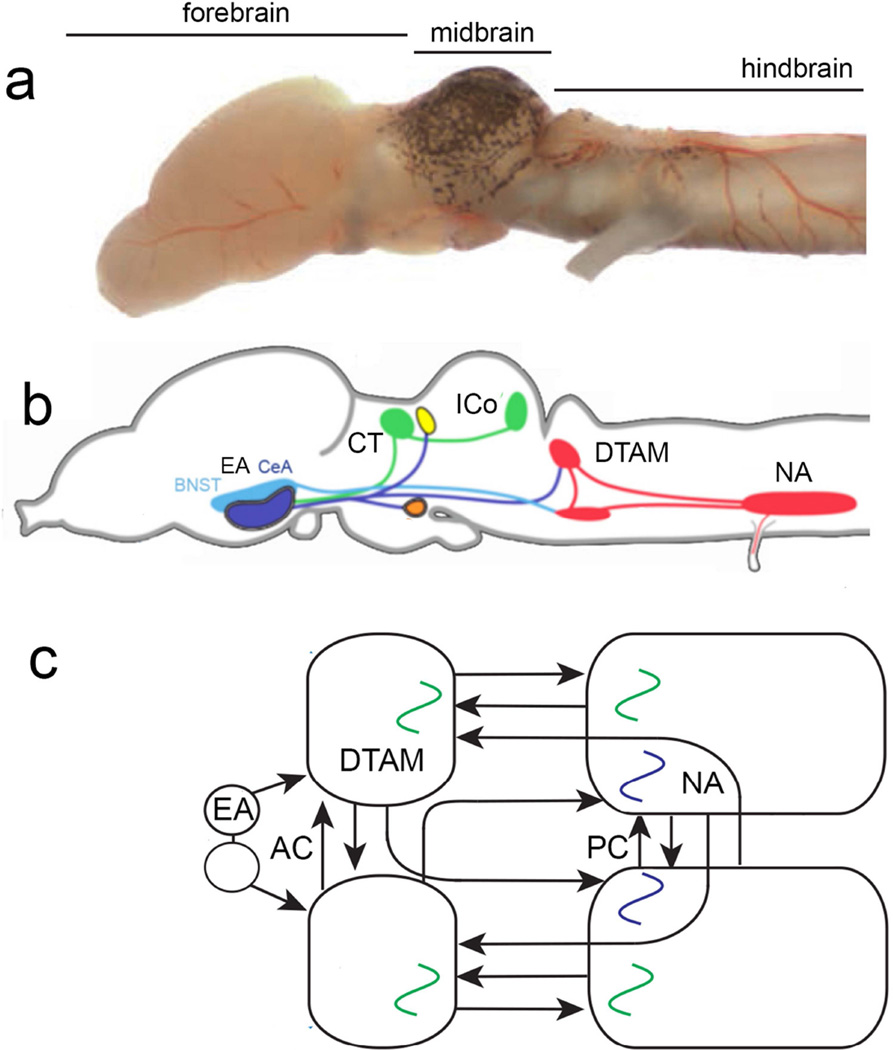

In X. laevis, the ex vivo preparation has revealed key features of hindbrain circuitry as well as the connections between forebrain and hindbrain nuclei that initiate vocalizations and control vocal patterning (Brahic and Kelley, 2003; Hall et al., 2013; Fig. 3a,b). The fictively calling brain has facilitated the analysis of the role of two groups of hindbrain neurons linked to respiration in many other vertebrates. One is a nucleus, DTAM, in the rostral hindbrain that projects throughout NA (Fig. 3b). DTAM is rhythmically active during fictive advertisement calling (Zornik et al., 2010; Fig. 3c). The male-specific advertisement call (Fig. 1) consists of fast and slow trills; DTAM controls fast trill duration and thus overall call duration and period (Zornik and Yamaguchi, 2012). The other respiratory-linked nucleus is NA in the caudal hindbrain that includes both glottal and laryngeal motor neurons. Nucleus ambiguus is responsible for the slow trill pattern initiated by descending input from DTAM (Fig. 3c). Each half of the hindbrain includes independent vocal pattern generators and these are coordinated by an anterior commissure (AC) at the level of DTAM and a posterior commissure (PC) at the level of NA as well as by reciprocal ipsilateral and contralateral connections between DTAM and NA (Fig. 3c). Activity in DTAM influences both vocalization and respiration. DTAM provides provides monosynaptic excitatory (glutamate) input to laryngeal motor neurons and excites inhibitory (GABA) interneurons that suppress activity of glottal motor neurons (Zornik and Kelley, 2008). Since Xenopus calls while submerged (Fig. 1a), this inhibitory circuit element prevents water in the mouth cavity from entering the lungs during vocal production.

Fig. 3.

Initiation and production of vocal motor patterns in X. laevis. a The ex vivo brain (Fig. 1a) now viewed from the side and illustrating subdivisions (hindbrain, midbrain and forebrain) that include neural circuits participating in initiation of vocal patterns. In an adult male brain, nucleus ambiguus (NA) that includes glottal and laryngeal motor neurons (b) is ~1 mm from rostral to caudal. b A current view of brain nuclei that participate in vocal patterning. The activity of neurons in the inferior colliculus (ICo) of the midbrain is preferentially driven by sound pulse rates characteristic of specific calls (Elliott et al., 2011). The ICo projects via the central nucleus of the thalamus (CT) to the central amygdala (Ce) in the ventral forebrain (Brahic and Kelley, 2003). Stimulation of either the CeA or the adjacent bed nucleus of the stria terminal is (BNST; together the extended amygdala or EA) in vivo initiates fictive advertisement calling (Hall et al., 2013). c A current view (from Yamaguchi et al., 2016) of the forebrain and hindbrain connections and activity responsible for initiating and coordinating fictive calling. This schematic, bilateral view (from the top) extends from the EA rostrally (left) to NA caudally. The hindbrain includes separate pattern generator circuits for the two components of the male advertisement call: fast trill and slow trill. The slow trill pattern generator (in blue) is co-extensive with NA while the fast trill generator (in green) is distributed between NA and a more rostral nucleus DTAM (used as a proper name). Coordination between the two halves of the hindbrain is accomplished by contralateral connections at the level of DTAM (the anterior commissure or AC) and NA (the posterior commissure or PC) and by bilateral connections between DTAM and NA.

Breathing and calling: brain circuit homologs

Individual neurons within neural circuits can be identified by their molecular identities - e.g. transcription factors, neurotransmitters, ion channels - as well as by their developmental origins and connections to other neurons. Molecular identities support homology (i.e. similarity across species due to inheritance from a recent ancestor) of the Xenopus caudal hindbrain nucleus that includes laryngeal and glottal motor neurons (N. IX–X) to the NA of mammals and other vertebrates (Albersheim-Carter et al., 2016). As in other vertebrates, including mammals, neurons in Xenopus N. IX–X express a key hindbrain transcription factor, pHox2B, and originate from caudal hindbrain segments (rhombomeres). N. IX–X motor neurons are cholinergic and project to glottal, laryngeal or heart muscles.

Using these kinds of criteria, candidate homologs for nucleus DTAM in the rostral hindbrain include the paratrigeminal respiratory group (pTRG) in a non-vocal basal vertebrate, the lamprey (Missaghi et al., 2016), and the parabrachial area (PBA) in vocal mammals (Dick et al., 1994; Smith et al, 2013). Neurons in the lamprey pTRG originate from rostral rhombomeres and provide glutamatergic innervation to NA. Neurons in the lamprey PTRG are rhythmically active and control expiration. Neurons in the mammalian PBA also express pHox2B, originate developmentally from rostral rhombomeres, provide glutamatergic innervation to nucleus ambiguus and are rhythmically active during respiration; PBA activity is also tied to vocalization (Hage et al., 2006). The role of DTAM in Xenopus vocalizations (shared with the PBA in mammals) could represent an exaptation (co-option) of an expiratory hindbrain circuit element present in basal vertebrates and preserved in many vertebrate lineages.

Another rhythmically active region, the preBötzinger nucleus, is located in the caudal hindbrain, ventral to NA, and appears essential for respiratory patterning in mammals including humans. Given the strong evolutionary conservation of the caudal rhombomeres from which this nucleus originates (Bass et al., 2008), homologs of the preBötzinger nucleus are likely contributors to respiratory and/or vocal patterns in other groups such as Xenopus. The pulmonary pattern generator of frogs, coextensive with NA, is a candidate homolog though circuit elements are not yet characterized molecularly (Smith et al., 2016). The slow trill pattern generator in X. laevis is contained within NA (Fig. 3c) and could be homologous to the mammalian preBötzinger complex. Characterizing transcription factor expression and electrophysiological characteristics, including rhythmicity, and connectivity will address this question.

Vocal production; forebrain initiation

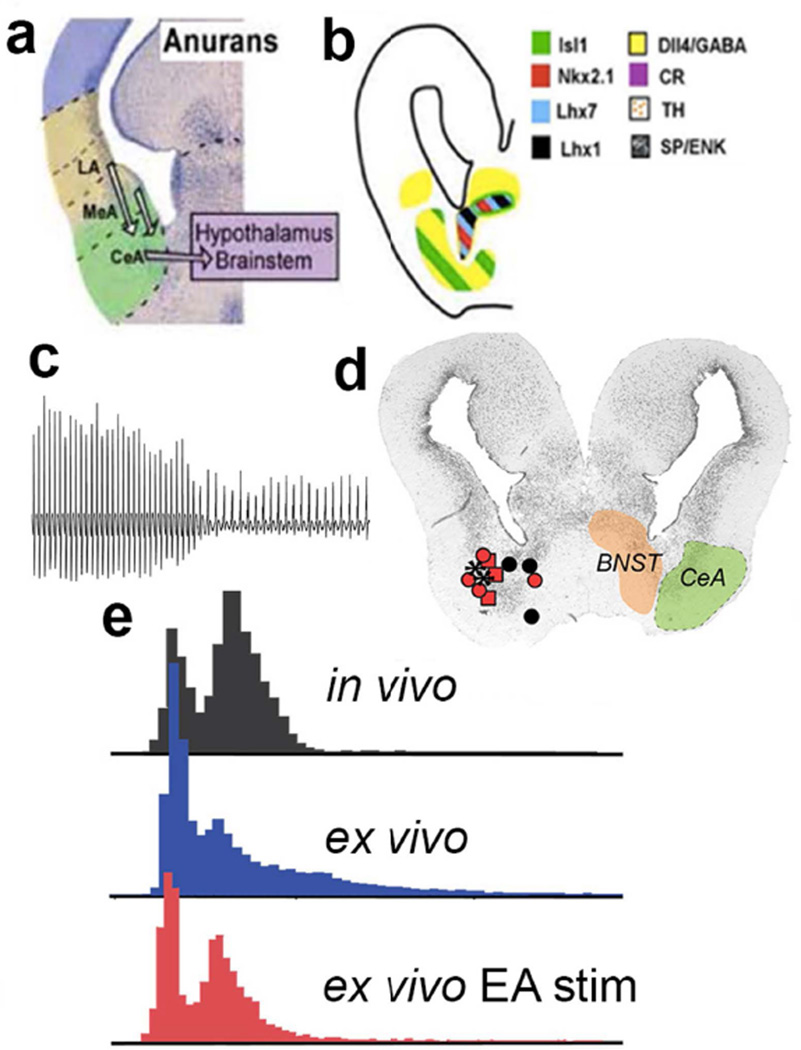

In Xenopus laevis, specific acoustic features of the calls of other frogs can evoke specific vocal response patterns. For example, female ticking transiently silences males (Elliott and Kelley, 2007) while intense male advertisement calling produces prolonged vocal suppression (Tobias et al., 2004). Selectivity for the specific temporal patterns of different calls can be demonstrated in a midbrain nucleus (Elliot and Kelley, 2011) and can be relayed to DTAM via a nucleus of the ventral forebrain (Fig. 3b). Transcription factor expression and connectivity (Moreno and Gonzalez, 2007) support the homology of this forebrain nucleus to the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA; Fig. 4a,b), known to govern both autonomic responses and vocalizations in other vertebrates including mammals (Ma and Kanwal, 2014). Electrical stimulation in the X. laevis ex vivo brain reveals that the CeA and the adjacent bed nucleus of the stria terminal is (collectively the extended amygdala or EA) initiate fictive advertisement calling in male brains (Hall et al., 2013; Fig. 4b–d). The output of the EA is inhibitory (GABAergic; Fig. 4b). When EA output to DTAM is removed bilaterally and the anterior commissure is transected, the left and right brainstem produce uncoordinated fictive fast trills but fictive slow trills remain coordinated (Yamaguchi et al., 2016; see Fig. 3c). The ex vivo brain preparation of Xenopus can thus reveal not only detailed hindbrain neural circuit mechanisms but also potential roles for sensory input in initiating vocal responses.

Fig. 4.

Molecular identity of forebrain nuclei that contribute to vocal initiation. a and b are modified from Moreno and Gonzalez, 2007. c–e are modified from Hall et al. 2013. a The anuran amygdaloid complex in a transverse hemisection of the caudal forebrain illustrating component nuclei, including descending projections to the brainstem (hindbrain); medial is to the right and dorsal is up. b A schematic hemisection corresponding to a and illustrating expression of a number of transcription factors (Isl1, Nkx2.1, Lhx7, Lhx1, Dll4), neurotransmitters or neuromodulators (GABA, TH, SP and ENK) and a calcium-binding protein (CR). Note the widespread distribution of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA within the CeA. Expression of these molecular markers corresponds to similar patterns in mammals (not included).c A fictive advertisement call recorded from the VN after microstimulation in the EA. d Effective (red, asterisks) and ineffective (black) stimulation sites for evoking fictive advertisement calls. e Comparison of temporal features (fast and slow trill) recorded from an advertisement calling male (in vivo), a fictively advertisement calling male brain (ex vivo), and following EA microstimulation (ex vivo EA stim) indicates that EA activity can initiate a specific fictive call pattern.

Sexual differentiation of vocal circuits

The Xenopus vocal repertoire differs by sex (Fig. 1). In X. laevis, as in most vertebrates, sexual differentiation reflects the secretion of steroids (androgens and estrogens) from the gonads during development or in adulthood (Zornik and Kelley, 2011). The male-typical advertisement call pattern can be evoked, even in adult females, by androgen treatment (Potter et al., 2005). Some neurons in NA and DTAM express androgen receptor (a ligand-activated transcription factor) in both sexes (Perez et al., 1996). Following androgen treatment, ex vivo brains from adult females produce fictive advertisement calling rather than fictive ticking (Potter et al., 2011). The fictively calling adult female brain thus provides an opportunity to determine how neural circuits are re tuned during the course of exposure to, and withdrawal of, androgens. In addition, the developmental effects of gonadal steroids on neural circuitry (the classical “organizational” effects (Wallen, 2009) experienced by males can be isolated from the effects of hormone secretions during adulthood (the classical “activational” effects) experienced both by males and androgen-treated females. Gonadal steroids regulate sensitivity to acoustic features of Xenopus vocalizations as well as motor patterns (Hall et al., 2016). Auditory sensitivity to species-specific sound frequencies in advertisement calls is greater in adult females due to ovarian hormones; steroids thus may also retune sensory circuits. As we understand more fully additional endocrine and sensory cues that govern behavioral interactions (Rhodes et al., 2014), the ex vivo brain preparation should also prove valuable in uncovering responsible neural mechanisms.

Comparative neuromics; gene expression and neural circuits

Comparing neural circuit functions across species uses the long term “experiment” of evolution to uncover the genetic mechanisms responsible for behavioral differences. This approach – comparative neuromics – is analogous to the comparative genomics approach used to distinguish functional and non-functional DNA within evolutionarily conserved sequences and to identify some important functional elements. Comparative neuromics has been used at the single neuron and circuit levels level to compare locomotory circuits in gastropod species (Katz, 2016). Here we propose extending this approach to analyze neural circuits that generate vocal patterns (Fig. 5). The fictively calling preparation in recently diverged species (10 to 500 thousand generations) should reveal mechanisms for retuning a specific neural circuit component. Over longer time scales (a few million generations), we can determine which elements of neuronal circuitry diverged. Comparisons over time scales of 10’s of millions of generations can identify invariant and critical neural circuit components for a specific function (but see Gjorgjieva et al., 2016).

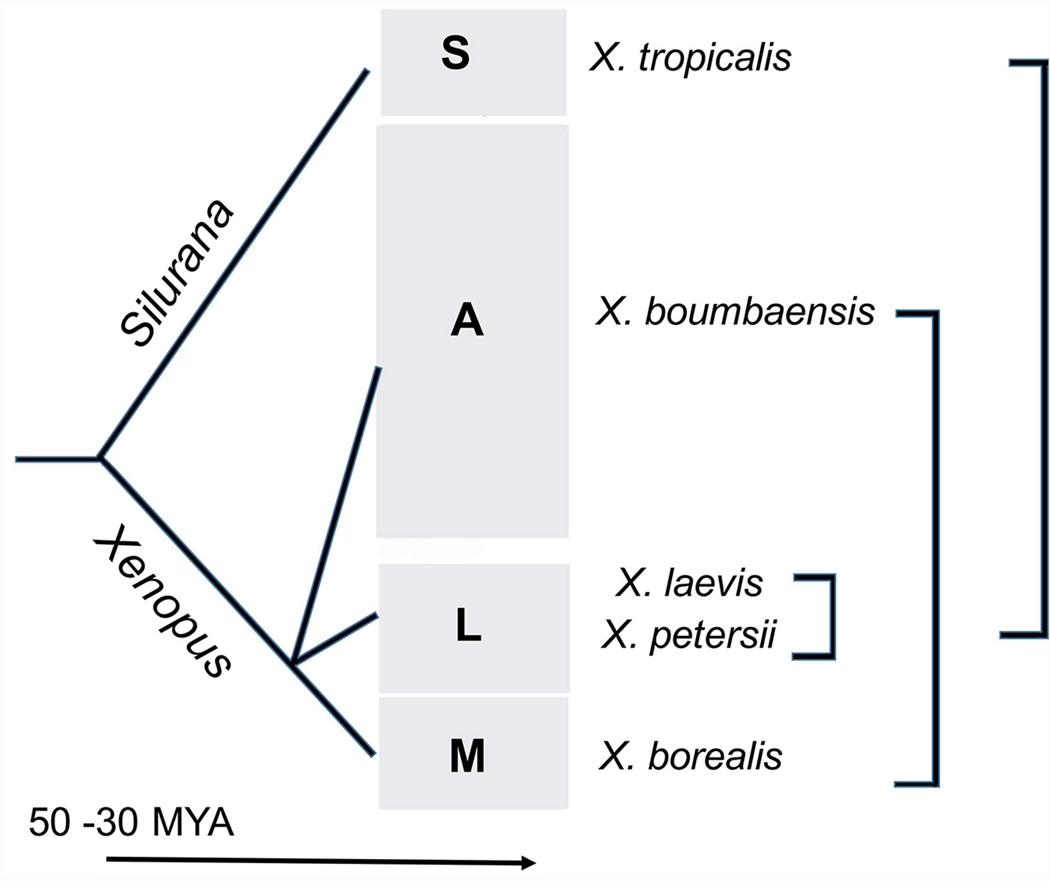

Fig. 5.

Examples of vocal circuit comparisons across and within Xenopus clades. The S, L, and M clades use different genetic mechanisms for primary sex determination. Comparison of neural circuit elements - using a fictively calling preparation - across species from these clades should reveal common and diverged neural circuit mechanisms. Divergence time estimates of Silurana and Xenopus based on Canatella, 2015. Phylogeny simplified from Evans et al., 2015.

The evolutionary history of the genus Xenopus has been estimated using molecular phylogenetics and other evidence. An advertisement call is present in males of all extant species and inter-species variation in temporal and spectral features of these advertisement calls have been evaluated in a phylogenetic context (Tobias et al., 2011). Comparison of species closely related to X. laevis (L clade: Fig. 5) reveal that intrinsic differences in the period and duration of activity in one circuit element - DTAM - can account for species differences in call temporal patterns (Barkan and Kelley, 2012). Advertisement call patterns within different Xenopus clades (A, M and L) diverge dramatically. Across these clades, the very distantly related species - X. borealis and X. boumbaensis (Fig. 5) - share a temporally simplified advertisement call pattern (Tobias et al., 2011). In X. boumbaensis, the hindbrain neural circuit has been re-tuned to reduce the duration of fast trill (Leininger et al., 2015). In X. borealis, however, the hindbrain neural circuit of males produces a temporally simplified pattern (Leininger and Kelley, 2013), suggesting a global alteration in active neural circuit elements, such as inactivation of DTAM contributions identified in X. laevis. Within the S clade (Fig. 5), one species (X. tropicalis) is in wide use as a biological model for genetics and development (Koide et al., 2005; Blum et al., 2009). Comparison of neural circuit elements - using a fictively calling preparation - across species from the S, A, M and L clades should reveal common and diverged neural circuit mechanisms. Recent evidence from X. tropicalis, X. laevis and X. borealis suggests the operation of at least three genomic mechanisms for primary sex determination, one in the S, one in the L and one in the M clade (Roco et al., 2015; Mawaribuchi et al., 2016; Furman and Evans, 2016; see Fig. 5). Retuning in response to hormones can thus also be followed across species with divergent modes of primary sex determination.

Xenopus and the BRAIN Initiative

In 2013, the United States launched an effort known as the BRAIN (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) Initiative to “accelerate the development and application of innovative technologies … to produce a revolutionary new dynamic picture of the brain that, for the first time, shows how individual cells and complex neural circuits (https://www.braininitiative.nih.gov/) interact in both time and space”. The potential payoff for this initiative is extraordinary but the challenges are steep. The major hurdles for the BRAIN Initiative are: imaging activity at scale, extracting functional circuit activity and determining the molecular ID of individual neurons in those circuits.

The smaller the brain, the easier it is to visualize all of the neurons responsible for producing a specific circuit function. Neural activity produces transient changes in calcium levels that can be tracked as fluorescent signals using genetically encoded calcium sensors (Nakai et al., 2001). Imaging an entire brain requires that all neurons express these sensors and this can be achieved via inserting the sensor molecule (e.g. GCaMP) into the genome and restricting expression to nerve cells (Ahrens et al., 2013). While some nervous systems such as flies (Drosophila) and worms (Caenorhabditis) are small enough for whole nervous system imaging (Prevedel et al., 2014), fundamental brain functions in these non-vertebrate models – such as the control of breathing and vocalizations – differ markedly from vertebrates as might be expected from estimates of vertebrate/invertebrate divergence (~600 million years). Within vertebrates, zebrafish (Danio rerio) larval escape and locomotion-related neural activity patterns can be imaged in vivo with calcium sensors and light-sheet microscropy (e.g. Dunn et al., 2016a,b). Imaging in zebrafish is, to date, however confined to larval stages and individual behaviors, rather than social interactions; imaging usually requires experimental immobilization or natural immobility (Muto and Kawakami, 2016). Ventilation via the gills, and the absence of vocalization (unlike some other fish e.g. Feng and Bass, 2016), preclude zebrafish as a model for understanding linkages between respiration and vocalization.

Xenopus, like other anurans (Huber and Gerhardt, 2002), are vocal. Their small brains generate fictive respiratory and distinct, sex-specific vocal patterns ex vivo obviating the need for immobility. The ex vivo preparation also offers the rare ability to study forebrain influences on motor patterns. Transgenic lines of X. laevis that express a calcium sensor (GCaMp6s) in all neurons (a collaboration with the National Xenopus Resource at the Marine Biological Laboratory) are being generated for evaluation in the fictively calling brain. Recent advances in light sheet microscropy and the post-imaging identification of individual neurons (Tomer et al., 2014, 2015) will provide new tools for understanding functional circuits in Xenopus not only for motor patterns but also for sensory processing. Whole brain activity mapping in the fictively calling Xenopus brain can substantially advance the objectives of the BRAIN Initiative.

Could a neuroscientist understand a microprocessor?

In an influential recent post (http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2016/05/26/055624), Jonas and Kording argue, using a microprocessor as a model organism, that currently available algorithms fail to reveal the hierarchy of information processing actually built into the circuit. Our ability to analyze the large and complex data sets supplied by whole brain imaging is limited not only by technological limitations, but also by gaps in our knowledge of the evolutionary breadth of nervous systems. In living organisms, essential components of information processing can be obscured by shared phylogenies. For example, some neurons in a nucleus of the ventral forebrain (the hippocampus) encode a specific spatial location (“place” or “grid” cells). In rodents, the hippocampus exhibits strong neuronal oscillations at 6 – 10Hz, the theta wave, which has been linked in both rats and mice to memory and navigation (Buzsáki and Moser, 2011). Bats also have place and grid cells but no theta waves (Yartsev et al., 2011), suggesting that theta is not essential and that its prominence in mice and rats is due to shared phylogeny rather than conserved function. Thus the comparative neuromics approach described above also has the potential to contribute to understanding which conserved neural circuit elements might be essential for a neural function and which reflect a shared phylogenetic history.

In summary, the fictively behaving ex vivo preparation in Xenopus provides a rare opportunity to combine recent advances in the analysis of neural circuits – brain-wide imaging, connectomics, molecular identification of single neurons – with comparative neuromics to determine specific functional components. Systematic analyses of the neural circuits underlying vocalizations can identify CNS mechanisms that underlie changes in behavioral phenotypes across evolution.

Acknowledgments

NIH support: NS23684 (D.B.K.), NS048834 (A.Y.), NS091977 (E.Z.)

The authors acknowledge the support of the National Xenopus Resource at the Marine Biological Laboratory (National Xenopus Resource RRID:SCR_013731): Marko Horb, Esther Pearl, Will Ratzen, Marcin Wlizla, Rosie Falco and Sean McNamara. We thank Raju Tomer at Columbia University for helpful discussion of brain imaging and comparative neuromics.

References

- Ahrens MB, Orger MB, Robson DN, Li JM, Keller PJ. Whole-brain functional imaging at cellular resolution using light-sheet microscopy. Nature methods. 2013;10:413–420. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albersheim-Carter J, Blubaum A, Ballagh IH, Missaghi K, Siuda ER, McMurray G, Bass AH, Dubuc R, Kelley DB, Schmidt MF, Wilson RJ. Testing the evolutionary conservation of vocal motoneurons in vertebrates. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology. 2016;224:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass AH, Gilland EH, Baker R. Evolutionary origins for social vocalization in a vertebrate hindbrain–spinal compartment. Science. 2008;321:417–421. doi: 10.1126/science.1157632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkan CL, Kelley DB. Neuromodulation of fictive vocal patterns in the isolated Xenopus laevis brain; Front. Behav. Neurosci. Conference Abstract: Tenth International Congress of Neuroethology; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Blum M, Beyer T, Weber T, Vick P, Andre P, Bitzer E, Schweickert A. Xenopus, an ideal model system to study vertebrate left-right asymmetry. Developmental dynamics. 2009;238:1215–1225. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahic CJ, Kelley DB. Vocal circuitry in Xenopus laevis: telencephalon to laryngeal motor neurons. Journal of comparative neurology. 2003;464:115–130. doi: 10.1002/cne.10772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G, Moser EI. Memory, navigation and theta rhythm in the hippocampal-entorhinal system. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16:130–138. doi: 10.1038/nn.3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannatella D. Xenopus in Space and Time: Fossils, Node Calibrations, Tip-Dating, and Paleobiogeography. Cytogenetic and genome research. 2015;145:283–301. doi: 10.1159/000438910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick TE, Bellingham MC, Richter DW. Pontine respiratory neurons in anesthetized cats. Brain research. 1994;636:259–269. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn TW, Gebhardt C, Naumann EA, Riegler C, Ahrens MB, Engert F, Del Bene F. Neural circuits underlying visually evoked escapes in larval zebrafish. Neuron. 2016a;89:613–628. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn TW, Mu Y, Narayan S, Randlett O, Naumann EA, Yang CT, Schier AF, Freeman J, Engert F, Ahrens MB. Brain-wide mapping of neural activity controlling zebrafish exploratory locomotion. eLife. 2016b;5:e12741. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott TM, Kelley DB. Male discrimination of receptive and unreceptive female calls by temporal features. Journal of experimental biology. 2007;210:2836–2842. doi: 10.1242/jeb.003988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott TM, Christensen-Dalsgaard J, Kelley DB. Temporally selective processing of communication signals by auditory midbrain neurons. Journal of neurophysiology. 2011;105:1620–1632. doi: 10.1152/jn.00261.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans BJ, Carter TF, Greenbaum E, Gvoždík V, Kelley DB, McLaughlin PJ, Pauwels OSG, Portik DM, Stanley EL, Tinsley RC, Tobias ML, Blackburn DC. Genetics, morphology, advertisement calls, and historical records distinguish six new polyploid species of African clawed frog (Xenopus, Pipidae) from West and Central Africa. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e01422823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng NY, Bass AH. “Singing” Fish Rely on Circadian Rhythm and Melatonin for the Timing of Nocturnal Courtship Vocalization. Current biology. 2016;26:2681–2689. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman BL, Evans BJ. Sequential turnovers of sex chromosomes in African clawed frogs (Xenopus) suggest some genomic regions are good at sex determination. Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 2016;6:3625–3633. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.033423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt HC, Huber F. Acoustic Communication in Insects and Anurans: Common Problems and Diverse Solutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gjorgjieva J, Drion G, Marder E. Computational implications of biophysical diversity and multiple timescales in neurons and synapses for circuit performance. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2016;37:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurdon JB, Hopwood N. The introduction of Xenopus laevis into developmental biology: of empire, pregnancy testing and ribosomal genes. International Journal of Developmental biology. 2003;44:43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hage SR, Jürgens U. On the role of the pontine brainstem in vocal pattern generation: a telemetric single-unit recording study in the squirrel monkey. The Journal of neuroscience. 2006;26:7105–7115. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1024-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall IC, Ballagh IH, Kelley DB. The Xenopus amygdala mediates socially appropriate vocal communication signals. The Journal of neuroscience. 2013;33:14534–14548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1190-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall IC, Woolley SM, Kwong-Brown U, Kelley DB. Sex differences and endocrine regulation of auditory-evoked, neural responses in African clawed frogs (Xenopus) Journal of comparative physiology A. 2016;202:17–34. doi: 10.1007/s00359-015-1049-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz PS. Phylogenetic plasticity in the evolution of molluscan neural circuits. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2016;41:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide T, Hayata T, Cho KW. Xenopus as a model system to study transcriptional regulatory networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:4943–4948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408125102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leininger EC, Kelley DB. Distinct neural and neuromuscular strategies underlie independent evolution of simplified advertisement calls. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2013;280(1756):20122639. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leininger EC, Kitayama K, Kelley DB. Species-specific loss of sexual dimorphism in vocal effectors accompanies vocal simplification in African clawed frogs (Xenopus) Journal of experimental biology. 2015;218:849–857. doi: 10.1242/jeb.115048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MZ, Schnitzer MJ. Genetically encoded indicators of neuronal activity. Nature neuroscience. 2016;19:1142–1153. doi: 10.1038/nn.4359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Kanwal JS. Stimulation of the basal and central amygdala in the mustached bat triggers echolocation and agonistic vocalizations within multimodal output. Frontiers in physiology. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00055. article 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawaribuchi S, Takahashi S, Wada M, Uno Y, Matsuda Y, Kondo M, Fukui A, Takamatsu N, Taira M, Ito M. Sex chromosome differentiation and the W-and Z-specific loci in Xenopus laevis. Developmental biology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.06.015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.06.015 0012-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missaghi K, Le Gal JP, Gray PA, Dubuc R. The neural control of respiration in lampreys. Respiratory physiology and neurobiology. 2016;234:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno N, González A. Evolution of the amygdaloid complex in vertebrates, with special reference to the an amnio-amniotic transition. Journal of anatomy. 2007;211:151–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00780.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto A, Kawakami K. Calcium Imaging of neuronal activity in free-swimming larval zebrafish. In: Kawakami K, Patton E, Orger M, editors. Methods in Molecular Biology. Clifton, NJ: Springer; 2026. pp. 1333–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai J, Ohkura M, Imoto K. A high signal-to-noise Ca2+ probe composed of a single green fluorescent protein. Nature biotechnology. 2001;19:137–141. doi: 10.1038/84397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl EJ, Grainger RM, Guille M, Horb ME. Development of Xenopus resource centers: The national Xenopus resource and the European Xenopus resource center. genesis. 2012;50:155–163. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez J, Cohen MA, Kelley DB. Androgen receptor mRNA expression in Xenopus laevis CNS: sexual dimorphism and regulation in laryngeal motor nucleus. Journal of neurobiology. 1996;30:556–568. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199608)30:4<556::AID-NEU10>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter KA, Bose T, Yamaguchi A. Androgen-induced vocal transformation in adult female African clawed frogs. Journal of neurophysiology. 2005;94:415–428. doi: 10.1152/jn.01279.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevedel R, Yoon YG, Hoffmann M, Pak N, Wetzstein G, Kato S, Schrödel T, Raskar R, Zimmer M, Boyden ES, Vaziri A. Simultaneous whole-animal 3D imaging of neuronal activity using light-field microscopy. Nature methods. 2014;11:727–730. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes HJ, Heather JY, Yamaguchi A. Xenopus vocalizations are controlled by a sexually differentiated hindbrain central pattern generator. The Journal of neuroscience. 2007;27:1485–1497. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4720-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes HJ, Stevenson RJ, Ego CL. Male-male clasping may be part of an alternative reproductive tactic in Xenopus laevis. PloS one. 2014;9:e97761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roco ÁS, Olmstead AW, Degitz SJ, Amano T, Zimmerman LB, Bullejos M. Coexistence of Y, W, and Z sex chromosomes in Xenopus tropicalis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112:E4752–E4761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505291112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MF, Goller F. Breath taking songs: Coordinating the neural circuits for breathing and singing. Physiology. 2016;31:442–451. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00004.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Session AM, Uno Y, Kwon T, Chapman JA, Toyoda A, Takahashi S, Fukui A, Hikosaka A, Suzuki A, Kondo M, van Heeringen SJ. Genome evolution in the allotetraploid frog Xenopus laevis. Nature. 2016;538:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature19840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson HB, Tobias ML, Kelley DB. Origin and identification of fibers in the cranial nerve IX-X complex of Xenopus laevis: Lucifer Yellow backfills in vitro. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1986;244:430–444. doi: 10.1002/cne.902440403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Abdala AP, Borgmann A, Rybak IA, Paton JF. Brainstem respiratory networks: building blocks and microcircuits. Trends in neurosciences. 2013;36:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Hires SA, Mao T, Huber D, Chiappe ME, Chalasani SH, Petreanu L, Akerboom J, McKinney SA, Schreiter ER, Bargmann CI. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nature methods. 2009;6:875–881. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias ML, Kelley DB. Vocalizations by a sexually dimorphic isolated larynx: peripheral constraints on behavioral expression. The Journal of neuroscience. 1987;7:3191–3197. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-10-03191.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias ML, Barnard C, O'Hagan R, Horng SH, Rand M, Kelley DB. Vocal communication between male Xenopus laevis. Animal Behaviour. 2004;67:353–365. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias M, Evans BJ, Kelley DB. Evolution of advertisement calls in African clawed frogs. Behaviour. 2011;148:519–549. doi: 10.1163/000579511X569435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomer R, Ye L, Hsueh B, Deisseroth K. Advanced CLARITY for rapid and high-resolution imaging of intact tissues. Nature protocols. 2014;9:1682–1697. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomer R, Lovett-Barron M, Kauvar I, Andalman A, Burns VM, Sankaran S, Grosenick L, Broxton M, Yang S, Deisseroth K. SPED light sheet microscopy: Fast mapping of biological system structure and function. Cell. 2015;163:1796–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallen K. The organizational hypothesis: Reflections on the 50th anniversary of the publication of Phoenix, Goy, Gerall, and Young (1959) Hormones and behavior. 2009;55:561–565. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JW, Wong AM, Flores J, Vosshall LB, Axel R. Two-photon calcium imaging reveals an odor-evoked map of activity in the fly brain. Cell. 2003;12:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wühr M, Güttler T, Peshkin L, McAlister GC, Sonnett M, Ishihara K, Groen AC, Presler M, Erickson BK, Mitchison TJ, Kirschner MW. The nuclear proteome of a vertebrate. Current biology. 2015;25:2663–2671. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager D. A unique sound production mechanism in the pipid anuran Xenopus borealis. Zoological journal of the Linnean society. 1992;104:351–375. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi A, Kelley DB. Generating sexually differentiated vocal patterns: laryngeal nerve and EMG recordings from vocalizing male and female African clawed frogs (Xenopus laevis) The Journal of neuroscience. 2000;20:1559–1567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01559.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi A, Barnes J, Appleby T. Rhythm generation, coordination, and initiation in the vocal pathways of male African clawed frogs. Journal of neurophysiology. 2016 doi: 10.1152/jn.00628.2016. jn-0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yartsev MM, Witter MP, Ulanovsky N. Grid cells without theta oscillations in the entorhinal cortex of bats. Nature. 2011;479:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature10583. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zornik E, Kelley DB. Regulation of respiratory and vocal motor pools in the isolated brain of Xenopus laevis. The Journal of neuroscience. 2008;28:612–621. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4754-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zornik E, Kelley DB. A neuroendocrine basis for the hierarchical control of frog courtship vocalizations. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 2011;32:353–366. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zornik E, Katzen AW, Rhodes HJ, Yamaguchi A. NMDAR-dependent control of call duration in Xenopus laevis. Journal of neurophysiology. 2010;103:3501–3515. doi: 10.1152/jn.00155.2010. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zornik E, Yamaguchi A. Coding rate and duration of vocalizations of the frog, Xenopus laevis. The Journal of neuroscience. 2012;32:12102–12114. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2450-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]