Abstract

Basic research on delay discounting, examining preference for smaller–sooner or larger–later reinforcers, has demonstrated a variety of findings of considerable generality. One of these, the magnitude effect, is the observation that individuals tend to exhibit greater preference for the immediate with smaller magnitude reinforcers. Delay discounting has also proved to be a useful marker of addiction, as demonstrated by the highly replicated finding of greater discounting rates in substance users compared to controls. However, some research on delay discounting rates in substance users, particularly research examining discounting of small-magnitude reinforcers, has not found significant differences compared to controls. Here, we hypothesize that the magnitude effect could produce ceiling effects at small magnitudes, thus obscuring differences in delay discounting between groups. We examined differences in discounting between high-risk substance users and controls over a broad range of magnitudes of monetary amounts ($0.10, $1.00, $10.00, $100.00, and $1000.00) in 116 Amazon Mechanical Turk workers. We found no significant differences in discounting rates between users and controls at the smallest reinforcer magnitudes ($0.10 and $1.00) and further found that differences became more pronounced as magnitudes increased. These results provide an understanding of a second form of the magnitude effect: That is, differences in discounting between populations can become more evident as a function of reinforcer magnitude.

Keywords: delay discounting, magnitude effect, hypothetical, crowdsourcing, humans

Delay discounting is the process by which reinforcer valuation declines as a function of delay to its receipt (see Odum, 2011). This decreased valuation of temporally remote reinforcers can be observed in humans and nonhuman species using paradigms that present choices between smaller, sooner reinforcers and larger, later reinforcers. These preferences can be captured by hyperbolic functions, in which reinforcers lose subjective value more steeply over more proximal delays and less steeply over more distant delays. The discounting function can be modeled with Mazur’s (1987) equation:

| (1) |

where SV is the immediate subjective value of the reinforcer, A is the nominal, full-magnitude value, D is the delay to reinforcer receipt, and k describes the discounting rate of the function.

One common observation made in studies of the discounting of delayed reinforcers is the magnitude effect, referring to an inverse relationship between rate of discounting and magnitude of reinforcer. For example, Green, Myerson, and McFadden (1997) assessed rates of delay discounting in a 24-trial monetary choice task at nominal values of $100, $2,000, $25,000, and $100,000, available at delays ranging from 3 months to 20 years. The smaller–sooner choices varied in magnitude from 1% to 99% of the delayed reinforcer, and were always available immediately. They found that the rate of discounting estimated by the free parameter of the hyperbolic model above, k, decreased as the magnitude of the reinforcer being discounted, A, increased. That is, at larger reinforcer magnitudes ($25,000 or $100,000), individuals made more choices for the larger, later reinforcer. The magnitude effect has also been observed broadly in discounting procedures which determine discounting of hypothetical (Baker, Johnson, & Bickel, 2003; Grace & McLean, 2005; Johnson & Bickel, 2002) and real monetary reinforcers (Johnson & Bickel, 2002), health (Petry, 2003), and other commodities, and increases with increasing difference between the magnitudes of delayed reinforcers (Green, Myerson, Oliveira, & Chang, 2013), although its exact mechanism is unknown.

Another common observation is that certain populations discount delayed reinforcers at a higher rate than control populations. Individuals who make more self-controlled choices in regards to their health and safety discount future monetary gains less steeply than those who do not (Bickel & Marsch, 2001). Increased population-level discounting rates have been found to be evident in substance use disorders and may function as a behavioral marker of substance abuse in alcohol (MacKillop et al., 2010; Mitchell, Fields, D’Esposito, & Boettiger, 2005; Petry, 2001; Vuchinich & Simpson, 1999), nicotine (Bickel, Odum, & Madden, 1999; Johnson, Bickel, & Baker, 2007), stimulant (Heil, Johnson, Higgins, & Bickel, 2006; Hoffman et al., 2006; Mejía-Cruz, Green, Myerson, Morales-Chainé, & Nieto, 2016), and opiate use disorders (Kirby, Petry, & Bickel, 1999), as well as in use of multiple substances (see MacKillop et al., 2011 for meta-analysis; Petry, 2002). Other populations which discount delayed reinforcers to a relatively greater degree than controls include the overweight and obese (see Amlung, Petker, Jackson, Balodis, & MacKillop, 2016; Bickel et al., 2014; Epstein, Salvy, Carr, Dearing, & Bickel, 2010), and individuals who do not engage in health maintenance behaviors (e.g., dental visits, prostate exams, mammograms, exercise, and cholesterol testing; Bradford, 2010). The observation of excessive discounting among a variety of disorders has led to the suggestion that delay discounting is a trans-disease process (Bickel, Jarmolowicz, Mueller, Koffarnus, & Gatchalian, 2012); that is, that delay discounting is a process which undergirds the etiology or phenotype of multiple disorders, making findings from one disorder relevant to others.

Many studies comparing population discounting rates have examined the discounting of magnitudes between $100 and $1,000. These tasks frequently reveal significant differences between controls and populations of interest in both substance use disorders (Bickel et al., 1999; Heil et al., 2006; Hoffman et al., 2006) and obesity (Bongers et al., 2015). However, the nominal full-magnitude value to be discounted varies widely across studies (i.e., $0.30 to $50,000 in MacKillop et al., 2011). Some of these studies at small reinforcer magnitudes ($10) have observed small effect sizes and nonsignificant differences in mean discounting rates between certain substance users and controls (Johnson, Herrmann, & Johnson, 2015; Kirby & Petry, 2004; Reynolds, Karraker, Horn, & Richards, 2003). This lack of effect size could be the result of no differences between populations that would be observed even at high magnitudes.

Alternatively, this difference may result from greater discounting associated with lower magnitudes obscuring population differences that would be evident at higher magnitudes. To the extent this is true, we call the magnitude-dependent ability to distinguish populations the second magnitude effect: That is, the ability to detect differences in delay discounting between different populations increases with magnitude of reinforcer. However, we note that at least some research has demonstrated that differences in discounting rates between populations do exist over at least some range of reinforcer magnitudes. Specifically, Kirby, Petry, and Bickel (1999) found that differences in discount rates between heroin-dependent participants and controls were preserved across all mean discount rates studied, ranging from $30-$80. Thus, we do not suggest that population-level differences are exclusive to high reinforcer magnitudes, only that differences are more robust at these magnitudes.

From the perspective of this second magnitude effect, we hypothesize in the present study that at very small reinforcer magnitudes, group differences in discounting rates between substance users and controls will be smaller than those differences at larger reinforcer magnitudes. If the second magnitude effect is observed, then the application of the basic observation of a magnitude effect in discounting of delayed reinforcers would be instrumental to translational efforts to understand differences in clinically relevant populations. In the present study, we used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) system, a crowdsourcing platform, to observe whether differences in discounting rates are magnitude-dependent between substance using and control populations. We examined discounting of five different magnitudes of delayed money, ranging from $0.10 to $1,000 in substance users (dual cigarette smokers and alcohol drinkers) and controls. Based on prior research (Moody, Franck, Hatz, & Bickel, 2016), this population was likely to show significant differences in discount rate in at least one of the magnitudes examined.

Method

Subjects

Participants (N = 129) were recruited from MTurk, which allows individuals to complete brief tasks as Human Intelligence Tasks (or HITs) and allows sampling from a large national population. High-risk substance users (n = 60) were required to score at least a 10 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT, Piccinelli, 1998) and a 4 on the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD, Fagerstrom, 2012). In contrast, control participants (n = 69) were required to score no more than a 7 and 3 on these scales, respectively. Data from individuals who did not meet these inclusion criteria were not analyzed. All participants were 18 years of age or older. Notably, we did not restrict this HIT to individuals with high HIT acceptance rates (indicating that the workers’ HITs have been accepted by requesters as following instructions a majority of the time; e.g., P. Johnson et al., 2015), as we were interested in recruiting from as broad a range of MTurk users as possible. This research was conducted with approval by the Virginia Tech Institutional Review Board.

Compensation for this HIT included a $4 base payment for the completion of the survey, with an additional $1 bonus if the responses passed data quality checks related to delay discounting. These quality checks had two response options: some amount of money now versus no money now, presented for each magnitude of reinforcer examined (see below). To pass the data quality check, the participant had to choose the nonzero monetary amount. Each participant who passed all checks received the $1 bonus for their effort. We only included in our final data set participants who passed all quality checks for all reinforcer magnitudes. For this reason, we excluded data for 13 participants (9 in high-risk dual substance users and 4 in the control condition). Our final dataset thus included 116 subjects.

Procedure

We used the five-trial, adjusting-delay discounting task (Koffarnus & Bickel, 2014) to estimate delay discounting rates for each participant at five reinforcer magnitudes: $0.10, $1.00, $10.00, $100.00, and $1,000.00, presented in random order. This task was used because it provides accurate estimates of delay discounting, is sensitive to the effects of experimental variables (including magnitude) in a manner similar to that of traditional discounting tasks, and can be completed rapidly (less than 1 min per magnitude), thus making it ideal to assess discount rates across a broad range of magnitudes (Bickel, Wilson, Chen, Koffarnus, & Franck, 2016; Koffarnus & Bickel, 2014).

At each magnitude, participants completed five trials in which they chose between a larger, delayed option (i.e., the magnitudes listed above) and a smaller, immediate option that was always equal to half of the delayed option. On the first trial, the delay to the larger reinforcer was 3 weeks, with the delay adjusting in approximately logarithmic units over the next four trials depending on participants’ previous choices (see Koffarnus and Bickel, 2014, for further detail). The final adjusted delay served as an estimate of ED50 (range: 1 hr to 25 years), or the effective delay at which reinforcers lose half of their value (Yoon & Higgins, 2008). To allow for comparison between our results and prior literature on delay discounting which has used the discount rate parameter, k, from Mazur’s (1987) hyperbolic model, we then calculated each participant’s k value as a simple mathematical inverse of the ED50 (Koffarnus & Bickel, 2014; Yoon & Higgins, 2008). These k values were then natural log-normalized to compensate for nonnormal distribution and allow for analysis with parametric statistical tests.

Our statistical analyses included both between-group and within-subject comparisons. To compare groups and observe main effects for both group and magnitude of reinforcer, we performed mixed effects ANOVAs on the repeated measures of log-normalized discounting rates at five magnitudes between high-risk dual substance users and controls. We then performed follow-up t tests of the difference in means between dual substance users and controls at each magnitude, so our results would be maximally comparable to other work which typically compares differences in discounting between groups at only one magnitude (Dixon, Marley, & Jacobs, 2003; Reynolds et al. 2007). To quantify the effect size of the difference between groups at each magnitude, we calculated Cohen’s d, which is the difference in two means over their pooled standard deviation (using the RMS of the standard deviations of the groups of users and controls). To examine correspondence between discounting rates obtained at each magnitude, we generated correlation coefficients (Pearson’s r) between discounting rates from each task. Data were analyzed and graphed in GraphPad Prism 6.03, IBM SPSS Statistics 24, and G*Power 3.1.

Results

Our sample was classified into either substance-using or control groups based on the AUDIT and FTCD cutoffs above. Demographics for these groups are described in Table 1. Differences in sex between groups were marginal, but approached significance (χ2(1, N = 111) = 3.35, p = .06). We found no statistically significant differences between our control and high-risk substance-using group in race (χ2(3, N = 111) = 2.03, p = .56), ethnicity (χ2(1, N = 111) = 0.053, p = .52), or income (χ2(2, N = 111) = 1.56, p = .46) using Chi-square analyses. A simple two-tailed unpaired t-test demonstrated no differences in age (t(114) = 0.75, p = .45).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Characteristic | Control (n = 65) |

Dual Substance (n = 51) |

|---|---|---|

| AUDIT Score (Mean, SD) | 3.338, 2.340 | 17.647, 7.962 |

| FTCD Score (Mean, SD) | 0.861, 1.261 | 5.803, 1.575 |

| Age (Mean, SD) | 34.461, 12.537 | 32.960, 7.402 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Working full time | 43 | 42 |

| Working part time | 12 | 3 |

| Not working | 2 | 3 |

| Other | 8 | 3 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 31 | 33 |

| Female | 34 | 18 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 54 | 47 |

| Black | 4 | 3 |

| American Indian | 2 | 2 |

| Asian | 7 | 2 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 4 | 5 |

| Non Hispanic | 61 | 46 |

| Education | ||

| Finished high school or received GED | 7 | 11 |

| Some College | 25 | 15 |

| Bachelor's degree | 27 | 23 |

| Advanced degree (e.g., Masters or Doctorate) | 6 | 2 |

| Household Income | ||

| $1–$30,000 | 13 | 14 |

| $30,001–$60,000 | 34 | 21 |

| $60,001 or more | 18 | 16 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 21 | 24 |

| Married | 27 | 19 |

| Other | 17 | 8 |

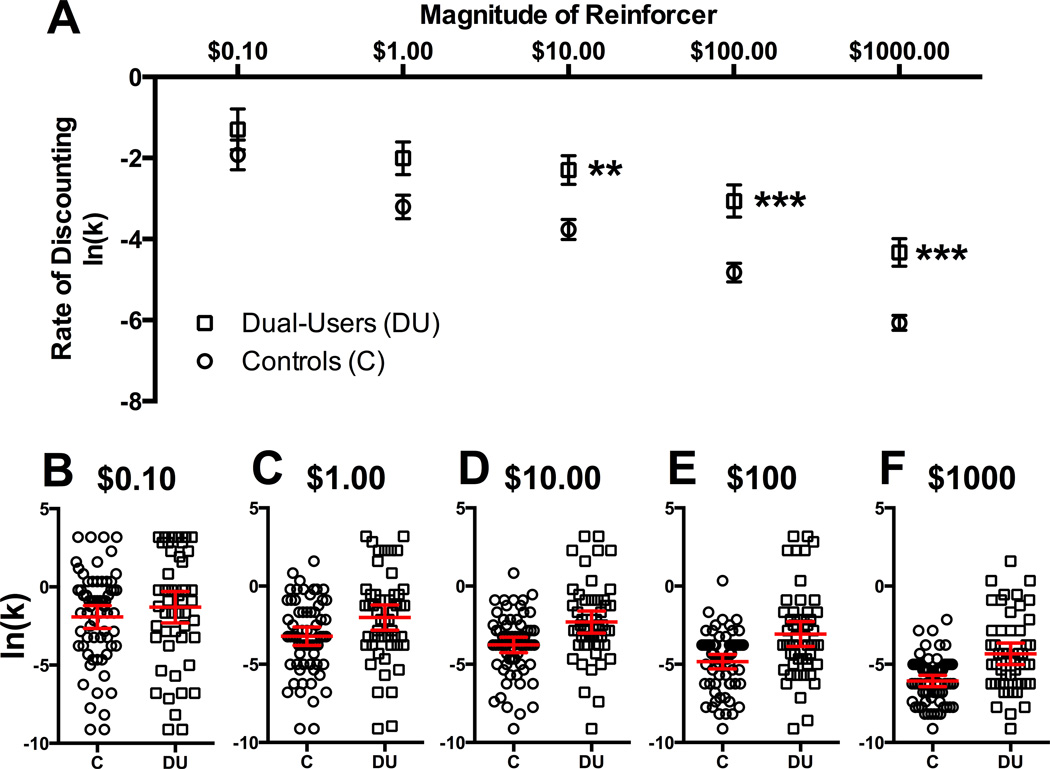

We compared the natural log of participants’ derived k values across both groups and magnitudes (see Figure 1). Figure 1 depicts natural log transformed k values for each group across all five reinforcer magnitudes. We performed a mixed-effects ANOVA with magnitude of discounting as a within-subjects repeated measure and substance use as a between-subjects group measure. Mauchly’s test (Mauchly 1940) indicated that the assumption of sphericity (or approximately equal variances across all possible pairs of within-subjects conditions) had been violated (χ2(2) = 61.9, p < .001), and therefore degrees of freedom were corrected using Greenhouse-Geisser estimates of sphericity (ε = 0.769), which accounts for intercorrelation of error between cells (Greenhouse & Geisser, 1959). Results of this ANOVA revealed a main effect for both magnitude (F(3.077, 350.74) = 76.670; p < .0001) and group (F(1, 114) = 12.90; p < .0001). The interaction term between group and magnitude was marginal, but approached significance (F(3.077, 350.74) = 2.25, p =.081).

Figure 1.

Displayed in panel A are group comparisons of discounting rates (as natural-log-normalized k values) between controls with low AUDIT ( < 8) & FTCD ( < 4) scores and dual-substance users with high AUDIT ( > 10) and FTCD ( > 4) scores, over all five magnitudes of reinforcer examined. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Asterisks denote levels of significance of group difference between mean discounting rates. Panels B-F display group data including mean and and 95% confidence intervals as well as individual data points representing individual participant’s natural-log-normalized discounting rates across the $0.10, $1.00, $10.00, $100.00, and $1000.00 conditions, in that order.

We performed follow-up comparisons between groups and across magnitudes using multiple t tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (Holm, 1979). We found no significant differences between controls and current substance users at the smallest magnitudes of reward, $0.10 (t(570) = 1.43, p = .17) and $1.00 (t(570) = 2.55, p = .011), but the groups were distinguishable at the $10 (t(570) = 3.11, p = .0019), $100 (t(570) = 3.75, p = .00019), and $1000 (t(570) = 3.69, p = .00023) conditions. We note that without corrections for multiple comparisons, the difference between substance users and controls was significant at the $1.00 level, but not at the $0.10 level. The effect size (Cohen’s d) of the difference in mean increased with increasing magnitude. Table 2 displays the means, standard deviations, and effect sizes between groups at all magnitudes.

Table 2.

Group statistics and Cohen’s d at each magnitude

| Dual users | Controls | Cohen’s d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnitude | Mean k | SD | Mean k | SD | |

| $0.10 | −1.29 | 3.58 | −1.92 | 2.94 | 0.192 |

| $1.00 | −2.01 | 2.87 | −3.21 | 2.35 | 0.457 |

| $10.00 | −2.30 | 2.52 | −3.76 | 1.99 | 0.643 |

| $100.00 | −3.06 | 2.83 | −4.83 | 1.87 | 0.735 |

| $1000.00 | −4.33 | 2.44 | −6.07 | 1.49 | 0.860 |

Table 3 displays Pearson's correlation coefficients between delay discounting rates across magnitudes for each group. Within both groups, all discounting rates were significantly correlated (p < .01), with r values varying from .327 (a small positive correlation) to .750 (a large positive correlation; see Cohen, 1988). In general, correlation coefficients were stronger in the control group. In controls, correlation coefficients between discounting rates at the highest magnitude ($1000) positively covaried with magnitude; that is, correlation between discounting at $1000 and discounting at $100 and $10 was large, and only correlation with discounting at $1.00 and $0.10 was small. In the dual user group, discounting at the $1000 condition was also most closely correlated with the $100 condition. Discounting rates at lower magnitudes ($10.00 and below) were not correlated with discounting at $1000 in a magnitude-dependent fashion.

Table 3.

Correlations between delay discounting rates across magnitudes

| Controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $0.10 | $1.00 | $10.00 | $100.00 | $1000.00 | |

| $0.10 | - | ||||

| $1.00 | 0.605*** | - | |||

| $10.00 | 0.659*** | 0.713*** | - | ||

| $100.00 | 0.557*** | 0.566*** | 0.750*** | - | |

| $1000.00 | 0.327* | 0.430** | 0.633*** | 0.670*** | - |

| Dual Users | |||||

| $0.10 | $1.00 | $10.00 | $100.00 | $1000.00 | |

| $0.10 | - | ||||

| $1.00 | 0.690*** | - | |||

| $10.00 | 0.582*** | 0.602*** | - | ||

| $100.00 | 0.490** | 0.590*** | 0.600*** | - | |

| $1000.00 | 0.534*** | 0.467** | 0.497** | 0.735*** | - |

indicates a weak positive correlation (r > 0.1)

indicates a moderate positive correlation (r > 0.3)

indicates a strong positive correlation (r > 0.5) (from Cohen, 1988)

Discussion

We investigated whether dual substance users of alcohol and tobacco may be differentiable from controls over $0.10, $1.00, $10.00, $100.00, and $1,000 delay discounting tasks. Although the direction of the differences in means between substance using and non-substance-using groups was consistent with established literature that shows substance users discount more than controls, the degree of this difference varied systematically with magnitudes and was not statistically significant at or below $1. Both controls and current high-risk substance users discounted these magnitudes heavily, with no significant differences between substance users and controls at a $0.10 and $1 magnitudes. At the $10.00 magnitude, a difference emerged between the groups, which became larger (i.e., higher Cohen’s d) at higher magnitudes up to the $100 condition. We additionally found that the effect size indicating difference in mean discounting rates between our two groups increased with the magnitude of reward being discounted. We suggest that this finding is a second form of the magnitude effect; that is, the magnitude effect operates when comparing populations and therefore the study of low-magnitude reinforcers can diminish the ability to detect difference in delay discounting between populations.

Research in delay discounting has been used to try to identify differences in groups with poor health outcomes (i.e., substance users), and has been highly productive; however, some research has not found differences between groups, possibly due to the magnitude of reward in the delay discounting task used. We hypothesized that this could be due to interplay between the magnitude effect, where individuals make more immediate choices at lower magnitudes, and the group effect found when comparing controls and substance users. Our results provide a context within which to interpret other research that has found small or negligible differences in discounting between smokers and controls at smaller magnitudes, such as $10 (P. Johnson et al., 2015; Reynolds et al., 2003) or alcohol users and controls at $25-$85 magnitudes (Kirby & Petry, 2004). Considering this form of the magnitude effect may be useful when evaluating negative results such as comparing discounting rates of pathological gamblers to controls in discounting of $25-$85, (Madden, Petry, & Johnson, 2009) or overweight/obese participants to controls in discounting of $10 (Fields, Sabet, & Reynolds, 2013; Hendrickson & Rasmussen, 2013).

These previous studies may have also observed nonsignificant results due to an interaction between this second form of the magnitude and relatively small sample sizes. We performed power analyses to estimate the numbers of participants required to observe significant differences between groups of high-risk dual users (a subclinical substance-using population) and controls. These analyses, based on the effect sizes presented in Table 2, indicate that to distinguish between groups at a magnitude of $0.10 would require 1412 participants; to distinguish between groups at a magnitude of $1.00, 252; at $10.00, 128; at $100, 100; and finally, at $1000, 74 individuals. These findings suggest that published studies failing to report significant differences in discounting between substance users and controls may not have included samples of sufficient sizes (e.g., Kirby and Petry 2004; Reynolds et al. 2003). These power analyses demonstrate that delay discounting at larger magnitudes leads to a potentially greater ability to distinguish between groups at smaller sample sizes, indicating that delay discounting of $1,000 is the most sensitive measure presented here.

Distinguishing between populations is multiply determined, however, and we acknowledge other research has found discounting tasks at smaller magnitudes to be sensitive to some group differences, and not uniformly with small effect sizes (Fields, Leraas, Collins, & Reynolds, 2009; e.g., Mitchell, 1999). This result may in part be due to the criteria used to categorize individuals as substance users (with subclinical inclusion criteria leading to smaller effect sizes; Johnson et al., 2007; MacKillop et al., 2011; Ohmura, Takahashi, & Kitamura, 2005). Future work that seeks to detect differences in delay discounting rates between populations will need to take into account not only the degree of substance use (Johnson et al., 2007; MacKillop et al., 2011; Ohmura, Takahashi, & Kitamura, 2005), but also the magnitude of reinforcer used in the delay discounting task (with smaller magnitudes leading to smaller differences).

We acknowledge several limitations in the present study. We opted for classification of high-risk substance use behavior rather than substance dependence criteria. Our substance-using sample thus represents individuals who both drink and smoke in high-risk ranges. Future research may be better able to resolve the relationship between extent of substance use in other groups of substance users and sensitivity of discounting tasks to group differences at various magnitudes. Furthermore, due to the structure of Amazon’s MTurk system, only individuals who completed the HIT (i.e., individuals who proceeded through all questionnaires and all five discounting tasks) could be compensated for their work and included in the final data set, which may have selected for more conscientious workers. Additionally, due to the sensitivity of the minute discounting task to each individual response, we did not analyze any data from participants who missed any data quality checks throughout the entirety of the HIT. This exclusion may have further encouraged selection towards individuals with relatively higher conscientiousness. We attempted to compensate for this effect by recruiting from the general Amazon MTurk population, rather than selecting for only the most dedicated workers based on high HIT acceptance rates, as has been done in other discounting work on MTurk (Johnson et al., 2015). Finally, we acknowledge the restriction of our findings to one particular delay discounting procedure, the adjusting-delay task, and recognize the need for replication with other procedures.

This finding of a second type of magnitude effect could be the result of an interaction between reinforcer magnitude and group over the broad range of monetary values examined, a ceiling effect in discounting rates produced at lower reinforcer magnitudes, or a combination of the two. Given our results demonstrated only a marginally significant interaction term between magnitude of discounting task and group, interpretation of an interaction effect is difficult. A ceiling effect in discount rates when reinforcer magnitudes are very small would indicate that all groups discount these values so steeply that differences cannot be detected between groups using the delay discounting tasks used. This ceiling effect could be methodological, resulting from the particular adjusting-delay discounting task used, although we note that this task allows measurement of a broad range of k values (i.e., 0.000110 to 24; see Koffarnus and Bickel, 2014). Alternatively, our null findings at small magnitudes could represent a more general limit in the degree to which individuals value delayed receipt of very small reinforcers, such as $0.10. Regardless of the source of a possible ceiling effect, this effect would require a reduction in variance in discount rates at the lowest magnitudes examined, which was not apparent in our results (see Fig. 1). However, we again note that due to the range restrictions in discount rates observable in this task, replication with other discounting tasks is necessary to clarify the nature of this magnitude-dependent degree of difference in delay discounting between substance users and controls.

This line of research extends in multiple future directions. Whether the same magnitude- dependent differences in discounting rates (i.e., the second form of the magnitude effect) can be observed with other populations remains to be empirically tested. If these magnitude-dependent differences exist, then the importance of this second form of magnitude effect as a determinant of detecting population differences would be confirmed. Further, although discounting rates from hypothetical delay discounting procedures correlate with procedures which present real or potentially real reinforcers (Madden, Begotka, Raiff, & Kastern, 2003; Wilson, Franck, Koffarnus, & Bickel, 2016), whether these other measures may show similar magnitude-dependent differences in population-level discounting rates remains unclear. The applicability of these results to other decision making may also be studied. If differences in impulsivity between substance users and controls are greatest at higher reinforcer magnitudes, it would follow that substance users’ real-world decisions might be most markedly different from non-substance-users’ when the rewards at stake are greatest. For example, substance users and controls may differ most in their decisions to delay gratification (or not) for “big-ticket” items like housing or medical care, rather than in relatively small, low-impact items like purchasing foods at full price or waiting for a marginal discount.

This study is an example of using basic science concerning the magnitude effect in delay discounting and translating it to address a clinical application; that is, detecting differences across populations with delay discounting. Here, we have found that differences in decision-making between controls and current substance users are most pronounced at the greatest reinforcer magnitudes—that is, when the rewards at stake are larger, the substance using population demonstrated the most immediate decisions, relatively. This finding can help to inform the further application of delay discounting tasks to identify treatment outcomes and to classify substance use disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Amlung M, Petker T, Jackson J, Balodis I, MacKillop J. Steep discounting of delayed monetary and food rewards in obesity: a meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2016;46(11):2423–2434. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000866. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716000866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker F, Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Delay discounting in current and never-before cigarette smokers: similarities and differences across commodity, sign, and magnitude. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112(3):382–392. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.382. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12943017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, George Wilson A, Franck CT, Terry Mueller E, Jarmolowicz DP, Koffarnus MN, Fede SJ. Using crowdsourcing to compare temporal, social temporal, and probability discounting among obese and non-obese individuals. Appetite. 2014;75:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.12.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Koffarnus MN, Gatchalian KM. Excessive discounting of delayed reinforcers as a trans-disease process contributing to addiction and other disease-related vulnerabilities: emerging evidence. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2012;134(3):287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.02.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA. Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: delay discounting processes. Addiction. 2001;96(1):73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961736.x. https://doi.org/10.1080/09652140020016978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Odum AL, Madden GJ. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146(4):447–454. doi: 10.1007/pl00005490. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00005490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Wilson AG, Chen C, Koffarnus MN, Franck CT. Stuck in time: Negative income shock constricts the temporal window of valuation spanning the future and the past. PloS One. 2016 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers P, van de Giessen E, Roefs A, Nederkoorn C, Booij J, van den Brink W, Jansen A. Being impulsive and obese increases susceptibility to speeded detection of high-calorie foods. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2015;34(6):677–685. doi: 10.1037/hea0000167. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford WD. The association between individual time preferences and health maintenance habits. Medical Decision Making: An International Journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making. 2010;30(1):99–112. doi: 10.1177/0272989X09342276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X09342276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the social sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Marley J, Jacobs EA. Delay discounting by pathological gamblers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36(4):449–458. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Salvy SJ, Carr KA, Dearing KK, Bickel WK. Food reinforcement, delay discounting and obesity. Physiology & Behavior. 2010;100(5):438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom K. Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2012;14(1):75–78. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr137. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields SA, Sabet M, Reynolds B. Dimensions of impulsive behavior in obese, overweight, and healthy-weight adolescents. Appetite. 2013;70:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.06.089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.06.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields S, Leraas K, Collins C, Reynolds B. Delay discounting as a mediator of the relationship between perceived stress and cigarette smoking status in adolescents. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2009;20(5–6):455–460. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328330dcff. https://doi.org/10.1097/FBP.0b013e328330dcff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace RC, McLean AP. Integrated versus segregated accounting and the magnitude effect in temporal discounting. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2005;12(4):732–739. doi: 10.3758/bf03196765. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16447389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J, McFadden E. Rate of temporal discounting decreases with amount of reward. Memory & Cognition. 1997;25(5):715–723. doi: 10.3758/bf03211314. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9337589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J, Oliveira L, Chang SE. Delay discounting of monetary rewards over a wide range of amounts. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2013;100(3):269–281. doi: 10.1002/jeab.45. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhouse SW, Geisser S. On methods in the analysis of profile data. Psykometrika. 1959;24:95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Heil SH, Johnson MW, Higgins ST, Bickel WK. Delay discounting in currently using and currently abstinent cocaine-dependent outpatients and non-drug-using matched controls. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(7):1290–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson KL, Rasmussen EB. Effects of mindful eating training on delay and probability discounting for food and money in obese and healthy-weight individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2013;51(7):399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.04.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WF, Moore M, Templin R, McFarland B, Hitzemann RJ, Mitchell SH. Neuropsychological function and delay discounting in methamphetamine-dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology. 2006;188(2):162–170. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0494-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-006-0494-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;77(2):129–146. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.77-129. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2002.77-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK, Baker F. Moderate drug use and delay discounting: a comparison of heavy, light, and never smokers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15(2):187–194. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.187. https://doi.org/10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PS, Herrmann ES, Johnson MW. Opportunity costs of reward delays and the discounting of hypothetical money and cigarettes. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2015;103(1):87–107. doi: 10.1002/jeab.110. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM. Heroin and cocaine abusers have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than alcoholics or non-drug-using controls. Addiction. 2004;99(4):461–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00669.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General. 1999;128(1):78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10100392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Bickel WK. A 5-trial adjusting delay discounting task: accurate discount rates in less than one minute. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2014;22(3):222–228. doi: 10.1037/a0035973. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Amlung MT, Few LR, Ray LA, Sweet LH, Munafò MR. Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216(3):305–321. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Miranda R, Jr, Monti PM, Ray LA, Murphy JG, Rohsenow DJ, Gwaltney CJ. Alcohol demand, delayed reward discounting, and craving in relation to drinking and alcohol use disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(1):106–114. doi: 10.1037/a0017513. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Begotka AM, Raiff BR, Kastern LL. Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11(2):139–145. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.2.139. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12755458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Petry NM, Johnson PS. Pathological gamblers discount probabilistic rewards less steeply than matched controls. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17(5):283–290. doi: 10.1037/a0016806. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauchly JW. Significance test for sphericity of a normal n-variate distribution. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1940;5:269–287. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE. An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. Commons, ML.; Mazur, JE.; Nevin, JA. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Mejía-Cruz D, Green L, Myerson J, Morales-Chainé S, Nieto J. Delay and probability discounting by drug-dependent cocaine and marijuana users. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233(14):2705–2714. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4316-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-016-4316-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, Fields HL, D’Esposito M, Boettiger CA. Impulsive responding in alcoholics. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(12):2158–2169. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000191755.63639.4a. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16385186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SH. Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146(4):455–464. doi: 10.1007/pl00005491. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10550496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody L, Franck C, Hatz L, Bickel WK. Impulsivity and polysubstance use: A systematic comparison of delay discounting in mono-, dual-, and trisubstance use. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2016;24(1):30–37. doi: 10.1037/pha0000059. https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL. Delay discounting: I’m a k, you're a k. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2011;96(3):427–439. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2011.96-423. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2011.96-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmura Y, Takahashi T, Kitamura N. Discounting delayed and probabilistic monetary gains and losses by smokers of cigarettes. Psychopharmacology. 2005;182(4):508–515. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0110-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-005-0110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154(3):243–250. doi: 10.1007/s002130000638. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11351931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Discounting of delayed rewards in substance abusers: Relationship to antisocial personality disorder. Psychopharmacology. 2002;162(4):425–432. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1115-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-002-1115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Discounting of money, health, and freedom in substance abusers and controls. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71(2):133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00090-5. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12927651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccinelli M. Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) Epidemiologia E Psichiatria Sociale. 1998;7(01):70–73. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00007144. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1121189X00007144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Karraker K, Horn K, Richards JB. Delay and probability discounting as related to different stages of adolescent smoking and non-smoking. Behavioural Processes. 2003;64(3):333–344. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(03)00168-2. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14580702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Patak M, Shroff P, Penfold RB, Melanko S, Duhig AM. Laboratory and self-report assessments of impulsive behavior in adolescent daily smokers and nonsmokers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15(3):264. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, Simpson CA. Delayed-reward discounting in alcohol abuse. The Economic Analysis of Substance Use. 1999 and. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11157.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AG, Franck CT, Koffarnus MN, Bickel WK. Behavioral economics of cigarette purchase tasks: Within-subject comparison of real, potentially real, and hypothetical cigarettes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2016;18(5):524–530. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv154. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JH, Higgins ST. Turning k on its head: Comments on use of an ED50 in delay discounting research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95(1–2):169–172. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]