Abstract

Objective

This study proposed and tested the first conceptual model of sexual minority specific (discrimination, internalized homophobia) and more general risk factors (perpetrator and partner alcohol use, anger, relationship satisfaction) for intimate partner violence among partnered lesbian women.

Method

Self-identified lesbian women (N=1048) were recruited from online market research panels. Participants completed an online survey that included measures of minority stress, anger, alcohol use and alcohol-related problems, relationship satisfaction, psychological aggression, and physical violence.

Results

The model demonstrated good fit and significant links from sexual minority discrimination to internalized homophobia and anger, from internalized homophobia to anger and alcohol problems, and from alcohol problems to intimate partner violence. Partner alcohol use predicted partner physical violence. Relationship dissatisfaction was associated with physical violence via psychological aggression. Physical violence was bidirectional.

Conclusions

Minority stress, anger, alcohol use and alcohol-related problems play an important role in perpetration of psychological aggression and physical violence in lesbian women's intimate partner relationships. The results of this study provide evidence of potentially modifiable sexual minority specific and more general risk factors for lesbian women's partner violence.

Keywords: lesbian, alcohol use, intimate partner violence, minority stress, domestic violence

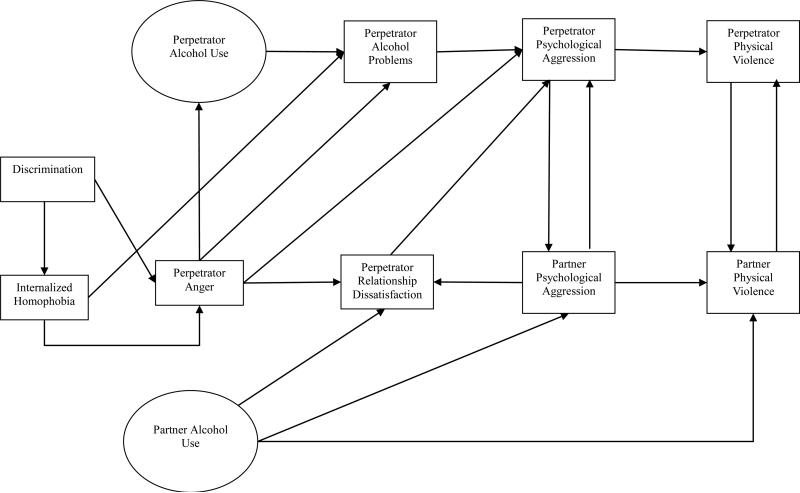

Although exact prevalence rates are difficult to determine, IPV among lesbian women seems to occur at rates equal to or higher than rates among heterosexual women (Edwards, Sylaska, & Neal, 2015; Walters, Chen, & Breiding, 2013). Based on a recent meta analysis, the mean prevalence estimates of lesbians’ physical IPV victimization and perpetration are 15% and 12%, respectively (Badenes-Ribera, Frias-Navarro, Bonilla-Campos, Pons-Salvador, & Monterde-i-Bort, 2015). Despite the frequency of IPV among lesbians, a conceptual framework for IPV perpetration among lesbian women has not been offered. Informed by minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003), models of IPV in heterosexual relationships (e.g., Leonard & Senchak, 1996; O'Leary, Smith Slep, & O'Leary, 2007; Smith Slep, Foran, Heyman, & U.S. Air Force Family Advocacy Research Program, 2014; Stuart et al., 2006), and a review of the literature on the association of substance use, minority stress, and IPV among sexual minority women (Lewis, Milletich, Kelley, & Woody, 2012), we developed a conceptual model that included both sexual minority specific factors (e.g., perceived discrimination and internalized homophobia) and individual- and couple-level variables (e.g., anger, partner and perpetrator alcohol use, perpetrator alcohol-related problems and relationship dissatisfaction) that were expected to be precursors to IPV (see Figure 1). The purpose of this study was to test the model in a community sample of young lesbian women (age 18-35 years). Our rationale for focusing on young lesbian women is that partner violence is more common among young women (Thompson et al., 2006), and younger lesbian women may be at particular risk for IPV as they engage in more heavy drinking with adverse consequences than older lesbian women (Hughes et al., 2006). Each of the components of the model is discussed in turn.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of partner and perpetrator IPV in lesbian relationships.

Sexual Minority Stress and IPV

The association between stress and IPV has been well documented (Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012). Although perceived stress and negative life events were associated with greater psychological and physical IPV perpetration (O'Leary et al., 2007) and daily hassles were associated with wives’ physical violence (Schumacher, Homish, Leonard, Quigley, & Kearns-Bodkin, 2008), stress associated with stigmatization and marginalization (i.e., sexual minority stress [SMS]; Meyer, 2003) merits consideration in a model of lesbian women's IPV. SMS includes distal experiences of violence, harassment, and discrimination, and proximal stressors related to concealment of sexual identity and negative feelings about one's self as a sexual minority individual (Meyer, 2003).

SMS is associated with a variety of negative health outcomes (e.g., Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Lehavot & Simoni, 2011) as well as IPV. Specifically, lifetime sexual minority discrimination was associated with psychological aggression perpetration in lesbian and bisexual women. Further, internalized homophobia (i.e., internalization of negative messages from society about sexual identity and/or conflict about one's same-sex attraction) was associated with the perpetration of physical or sexual violence in lesbian and bisexual women (Balsam & Szymanski, 2005). Among college students, identity concealment and internalized homophobia were associated with perpetration of physical, but not psychological or sexual violence (Edwards & Sylaska, 2013). Also, expectations of prejudice and discrimination were related to both IPV victimization and perpetration (Carvalho et al., 2011). In their recent review, Edwards et al. (2015) concluded that internalized minority stressors are positively related to increased physical and psychological IPV perpetration, whereas externalized minority stressors are generally unrelated to IPV perpetration, especially when considered alongside internalized minority stressors.

Mediators of the Sexual Minority Stress - IPV Association

Anger

Although SMS is associated with IPV, mechanisms that may underlie the SMS-IPV relationship are not well understood. Daily diary studies with community samples have shown that women's anger is associated with relationship aggression (Crane & Eckhardt, 2013; Crane & Testa, 2014). Similar to models of IPV in heterosexual community samples (e.g., Leonard & Senchak, 1996) we proposed that women's anger would predict alcohol use which in turn would predict psychological aggression and physical violence. Furthermore, similar to a recent model of IPV among Air Force members (Smith Slep et al., 2014) emphasizing how individual functioning (i.e., depression, physical well-being, and coping) contributes directly to women's IPV perpetration and indirectly via alcohol problems and relationship satisfaction, we included anger as an individual functioning variable in our model. Therefore, in our conceptual model, we predicted that SMS (i.e., perceptions of discrimination due to one's sexual orientation and the internalizing of social stigma) would contribute to anger and that anger would be a distal individual level factor contributing to IPV. Anger then serves as a precursor to alcohol use, alcohol problems, and relationship dissatisfaction which are theorized to contribute to IPV perpetration via psychological aggression. As research with heterosexual couples has also demonstrated associations between anger and alcohol use/disorders (e.g., Leite, Machado, & Lara, 2014; Sharma, Suman, Murthy, & Marimuthu, 2011) and negative relationship quality (MacKenzie et al., 2014), we expected anger to be related to IPV via perpetrator alcohol use/problems and relationship dissatisfaction.

Alcohol use

Alcohol use and IPV have been linked theoretically and empirically in samples of heterosexual individuals (see reviews by Foran & O'Leary, 2008; Shorey, Stuart, & Cornelius, 2011; Stuart, O'Farrell, & Temple, 2009). Alcohol use, heavy drinking (5 or more drinks on 5 or more days in past 30 days), and binge drinking (5 or more drinks on 1 day in past 30 days) have been associated with bidirectional partner violence among heterosexual women (Cunradi, 2007; Melander, Noel, & Tyler, 2010). Furthermore, among hazardous drinking heterosexual women (drinking four or more drinks at one time monthly for six months), alcohol use temporally preceeded IPV perpetration (Stuart et al., 2013). Also, heterosexual women's alcohol-related problems were associated with female-to-male violence in a community sample (Cunradi, Caetano, Clark, & Schafer, 1999) and with both psychological aggression and physical violence in a sample arrested for domestic violence and court-mandated to treatment (Stuart et al., 2006).

Although much less research has examined alcohol and IPV among sexual minority women, both individual and partner alcohol use and problem drinking have been implicated in risk for IPV in female same-sex couples (Glass et al., 2008; Lewis et al., 2012). Specifically, lesbian women who reported daily or weekly binge drinking were more likely to report physical and sexual relationship violence (Goldberg & Meyer, 2013). Also, in a sample of women with a history of IPV in the past five years, Eaton et al. (2008) found a non-significant trend between hazardous alcohol use and same-sex IPV (defined as physical, sexual, and psychological aggression as well as property destruction and threatening to disclose sexual orientation). Partner alcohol use has also contributed to relationship discord, partner psychological aggression, and partner physical abuse among heterosexual women court-referred for domestic violence (Stuart et al., 2006). We expected partner alcohol use to contribute to perpetrator relationship dissatisfaction and partner psychological and physical relationship aggression and perpetrator alcohol problems to contribute to physical IPV by way of psychological aggression.

Relationship dissatisfaction

High levels of relationship conflict and low levels of relationship satisfaction have been associated with heterosexual women's IPV perpetration (O'Leary et al., 2007; Smith Slep et al., 2014; Stith, Green, Smith, & Ward, 2008). Also among heterosexuals, heavy drinking resulted in relationship conflict (i.e., disagreements and negative interactions) later that same day (Fischer et al., 2005). Among lesbian and bisexual women, relationship satisfaction was inversely correlated with past year physical or sexual violence (Balsam & Szymanski, 2005) and psychological aggression (Balsam & Szymanski, 2005; Matte & Lafontaine, 2011).

Our conceptual model includes partner's behaviors (e.g., partner alcohol use, partner psychological aggression, partner physical aggression) reported by the perpetrator. Stuart et al.'s (2006) model included similar predictors based on data collected from both partners and found that partner's psychological aggression was positively associated with relationship dissatisfaction. Panuzio and DiLillo (2010) found psychological aggression during the first year of marriage predicted lower victim marital satisfaction one and two years later. Furthermore, psychological aggression has been shown to be more detrimental to marital satisfaction than physical violence in a community sample of heterosexual couples (Yoon & Lawrence, 2013). For these reasons, we hypothesized that perpetrator relationship dissatisfaction would predict perpetrator psychological aggression which would lead to physical IPV.

A Conceptual Model of IPV among Lesbian Women

To advance our understanding of IPV among lesbian women, our conceptual model was informed by considering the unique experiences of lesbian women in terms of minority stress and the larger literature on heterosexual women's IPV and is, to our knowledge, the first conceptual model of IPV among sexual minority women. Our model included sexual minority stressors, anger, self and partner alcohol use, and psychological aggression with physical violence as the outcome variable. Among heterosexuals, psychological aggression predicts physical violence both in cross-sectional (Edwards, Desai, Gidycz, & VanWynsberghe, 2009; Testa, Hoffman, & Leonard, 2011) and longitudinal (Schumacher & Leonard, 2005; Testa et al., 2011) studies. Psychological aggression is related to physical violence among sexual minority women as well (Mason et al., 2014; Matte & Lafontaine, 2011). Therefore, psychological aggression was expected to be the most proximal variable to the outcome of physical violence in our model. Also, both partner and perpetrator alcohol use are included in our model as they have been implicated as risk factors for IPV (e.g., Glass et al., 2008; Lewis et al., 2012). Finally, as Smith Slep et al. (2014) noted, models of IPV perpetration often focus on non-modifiable risk factors such as childhood physical abuse or socioeconomic risk factors. In the hope of translating findings from this model into prevention and intervention efforts to reduce IPV, we were particularly interested in components of the model that could be targeted for change in prevention or intervention programs.

The purpose of this research was to test a conceptual model of IPV in a community sample of young lesbian women. It was hypothesized that (1) sexual minority stressors (discrimination, internalized homophobia) would be related to IPV via perpetrator anger, alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, and relationship satisfaction (see Figure 1). Based on previous research (e.g., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Misra, Selwyn, & Rohling, 2012; Matte & Lafontaine, 2011; Melander et al., 2010; Stuart et al., 2006), it was also hypothesized that (2) psychological aggression and physical violence would be bidirectional.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Self-identified lesbian women were recruited from several online market research panels. Participants were invited to join the online panels in a variety of ways such as ads on popular websites, then mailed invitations and received an incentive determined by the online panel to complete the survey (e.g., points or rewards that could be redeemed for gift cards or donated to charity). In order to be eligible to participate, women had to 1) self-identify as lesbian, 2) be between 18 and 35 years of age, 3) be in a romantic relationship with another woman for at least three months, and 4) report physically seeing their partner at least once a month (N = 1470). Among the original eligible sample, 2% (n = 36) chose not to participate after reading a description of the research, 1% (n = 21) did not consent to participate, 16% (n = 236) failed quality checks of the data (i.e., response patterns suggesting inattention, rushing through the items), and 9% (n = 126) dropped out after beginning the survey. After deleting these participants, N = 1051. Three participants were then removed due to reporting extreme alcohol use (> 90 drinks per week) resulting in a final N for data analyses of 1048. The mean age of the sample was 28.79 years (SD = 4.30 years). Other demographic characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1. Participants completed the online survey in approximately 30 minutes.

Table 1.

Demographics of Sample

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 813 | 77.6 |

| African American | 108 | 10.4 |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 11 | 1.0 |

| Asian | 43 | 4.1 |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander | 3 | 0.3 |

| Some other race alone | 43 | 4.1 |

| Two or more races | 15 | 1.4 |

| Prefer not to answer | 12 | 1.1 |

| Highest educational level | ||

| High school graduate | 57 | 5.4 |

| Some college | 224 | 21.4 |

| Associate's degree | 92 | 8.8 |

| Bachelor's degree | 399 | 38.1 |

| Master's degree | 217 | 20.7 |

| Doctoral/professional degree | 57 | 5.4 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.2 |

| Annual income | ||

| < $50,000 | 394 | 43.7 |

| $50,000 to < $100,000 | 356 | 34.0 |

| $100,000 to < $150,000 | 136 | 13.0 |

| > $150,000 | 45 | 4.2 |

| Declined to answer | 53 | 5.1 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single, dating in a casual relationship | 30 | 2.9 |

| Single, dating in a serious relationship | 51 | 4.9 |

| Partnered, in a casual relationship | 38 | 3.6 |

| Partnered, in a committed relationship | 668 | 63.7 |

| Partnered, married, or in a civil union | 243 | 23.2 |

| Other | 18 | 1.7 |

| Cohabitating with partner | ||

| Yes | 775 | 74.0 |

| No | 271 | 25.8 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.2 |

| Frequency physically seeing partner | ||

| Daily | 817 | 78.0 |

| A few times a week | 101 | 9.6 |

| Once or twice a week | 55 | 5.3 |

| A few times a month | 41 | 3.9 |

| Monthly | 34 | 3.2 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Only homosexual/lesbian | 755 | 72.0 |

| Mostly homosexual/lesbian | 272 | 26.0 |

| Other | 21 | 2.0 |

| Past year sexual behavior | ||

| Women only | 999 | 95.3 |

| Women and men | 38 | 3.6 |

| No one | 8 | 0.8 |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 | 0.3 |

| Sexual attraction | ||

| Only women | 611 | 58.3 |

| Mostly women | 432 | 41.2 |

| Prefer not to answer | 5 | 0.5 |

Note. N = 1048

Measures

Discrimination

Participants were asked to indicate how often they experienced discrimination because they were assumed to be lesbian in the past 12 months. Response options ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Higher scores indicated more discrimination. This item was modeled after the item used to assess discrimination in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) (cf. McCabe, Bostwick, Hughes, West, & Boyd, 2010). In prior research 31% of LGB individuals who reported sexual orientation discrimination assessed in this way reported past year substance use disorder compared to 18% of those who did not report any discrimination (McCabe et al., 2010).

Internalized homophobia

The 6-item Personal Feelings about being a Lesbian subscale of the Lesbian Internalized Homophobia scale short form (S-LIHS; Piggot, 2004) was used to measure internalized homophobia. Participants rated items on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A sample item is: “If I could change my sexual orientation and become heterosexual, I would.” Higher scores indicated more internalized homophobia. Scores on the Personal Feelings about being a Lesbian subscale were significantly correlated with greater depression and lower self-esteem (Pigott, 2004), providing evidence of predictive validity. Cronbach's alpha was .68. Removing the item “I don't feel disappointment in myself for being a lesbian” increased the alpha to .72. Results were identical when the item was removed or included. Therefore, results based on the complete scale are reported.

Anger

The Anger subscale of the Buss Perry Aggression Questionnaire – Short Form (BPAQ-SF; Bryant & Smith, 2001) measured anger, involving physiological arousal, preparation for aggression, and emotional aspects of behavior (Buss & Perry, 1992). Participants responded to three items on a scale ranging from 1 (extremely uncharacteristic of me) to 5 (extremely characteristic of me). A sample item is: “I have trouble controlling my temper.” Higher scores indicated more anger. Concurrent validity was demonstrated by strong correlations (r = .91) between the Buss Perry Aggression Questionnaire and the Anger subscale of the Multidimensional Anger Inventory (Bryant & Smith, 2001). Cronbach's alpha was .78.

Perpetrator and partner alcohol use

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) was used to measure perpetrator and partner alcohol use. Participants used a 7-day grid to provide the number of ‘standard’ drinks typically consumed weekly over the past 90 days. A standard drink is defined as one 12 oz. beer, 1 ½ oz. of liquor, or 5 oz. of wine. Participants filled out the DDQ for their own and for their partner's drinking separately. Drinking quantity was calculated as the sum of drinks reported weekly. Binge drinking was calculated as the number of days that at least 4 or more drinks were consumed. The DDQ demonstrated strong convergent validity with the longer Drinking Practices Questionnaire and successfully distinguished between light and heavy drinkers (Collins et al, 1985).

Perpetrator alcohol problems

The Short Index of Problems (SIP-2R; Miller, Tonigan & Longabaugh, 1995) is a 15-item measure that assessed alcohol-related consequences during the past three months such as “I have taken foolish risks when I have been drinking” and “My physical health has been harmed by my drinking”. Respondents indicated the degree to which these experiences occurred using a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). The SIP 2-R has strong internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Miller et al., 1995) and good concurrent validity with measures of alcohol problems among treatment-seeking adults (Alterman, Cacciola, Ivey, Habing, & Lynch, 2009). Cronbach's alpha was .93.

Relationship dissatisfaction

The 4-item Dyadic Satisfaction subscale of the Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (RDAS; Busby, Christensen, Crane, & Larson, 1995) measured relationship satisfaction. Participants responded to items on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (all the time) such as “How often do you discuss terminating your relationship?” Higher scores indicated greater relationship satisfaction; therefore, we reverse scored the items to reflect relationship dissatisfaction. Among 295 LGBT men and women, the Dyadic Satisfaction subscale of the RDAS was positively associated with the Relationship Satisfaction subscale of the Scale for Assessing Same-Gender Couples (SASC) as well as the total SASC (Keown-Belous, 2012). Cronbach's alpha was .82.

Perpetrator and partner psychological aggression

The 28-item short form of the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (PMWI; Tolman, 1989, 1995) assessed perpetrator (14 items) and partner psychological aggression (14 items). The PMWI assesses both dominance-isolation (e.g., jealousy, treating as an inferior, and isolation from resources) and emotional-verbal violence (e.g., name calling, screaming, and swearing). Sample items are “My partner called me names” and “I called my partner names”. Participants responded to items by indicating the frequency of dominance/isolation and emotional/verbal violence perpetration or victimization during the past year using a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (very frequently). Higher scores indicated greater perpetration or victimization of psychological aggression. Validity of the PMWI among lesbian women is demonstrated by correlations with physical assault, negative mental health, and relational intrusiveness for both perpetrator and partner (Mason, Gargurevich, & Lewis, 2015). Cronbach's alpha was .87 for perpetrator psychological aggression and .89 for partner psychological aggression.

Perpetrator and partner physical violence

Perpetrator and partner physical violence were measured by having participants complete the 12 physical assault items from the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) for both self and partner physical violence. Sample items are “My partner slapped me” (partner) and “I slapped my partner” (perpetrator). Participants indicated how often these events occurred in the past year using count-based anchors ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times). Higher scores indicated more frequent victimization or perpetration of physical abuse. Validity of the CTS2 physical assault subscale is demonstrated by associations with masculinity, insecure attachment, and relationship dissatisfaction among lesbian and gay adults (Balsam & Szymanski, 2005; (McKenry, Serovich, Mason, & Mosack 2006). Cronbach's alpha was .88 for both perpetrator and partner physical violence.

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are displayed in Table 2. Less than 1% of data were missing. Based on Straus et al.'s (1996) classification of CTS2 items into minor and severe acts of IPV, 17.4% of the sample reported perpetrating at least one act of minor physical violence, 17.2% of the sample reported being the victim of at least one act of minor physical violence, 6.5% of the sample reported perpetrating at least one act of severe physical violence, and 6.8% of the sample reported being the victim of at least one act of severe physical violence.

Table 2.

Pearson Correlations among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sexual minority discrimination | - | .14** | .20** | .02 | .05 | .05 | .07* | .14** | .07* | .13** | .10** | .13** | .14** |

| 2. Internalized homophobia | - | .17** | .02 | .04 | -.04 | -.01 | .23** | .25** | .19** | .04 | .16** | .04 | |

| 3. Perpetrator anger | - | .09** | .06 | .04 | .04 | .24** | .29** | .40** | .25** | .30** | .21** | ||

| 4. Perpetrator drinking quantity | - | .83** | .48** | .47** | .43** | .10** | .17** | .15** | .16** | .09** | |||

| 5. Perpetrator binge drinking | - | .42** | .50** | .41** | .09** | .16** | .15** | .15** | .11** | ||||

| 6. Partner drinking quantity | - | .84** | .25** | .04 | .15** | .16** | .15** | .20** | |||||

| 7. Partner binge drinking | - | .29** | .04 | .15** | .17** | .15** | .16** | ||||||

| 8. Perpetrator alcohol problems | - | .24** | .36** | .23** | .31** | .18** | |||||||

| 9. Perpetrator RD | - | .60** | .38** | .62** | .35** | ||||||||

| 10. Perpetrator PA | - | .57** | .86** | .51** | |||||||||

| 11. Perpetrator physical violence | - | .52** | .79** | ||||||||||

| 12. Partner PA | - | .54** | |||||||||||

| 13. Partner physical violence | - | ||||||||||||

| M | 2.15 | 9.00 | 5.85 | 7.40 | .59 | 6.40 | .51 | 1.94 | 4.30 | 5.07 | .92 | 5.56 | .92 |

| SD | .92 | 4.53 | 2.83 | 7.99 | 1.11 | 8.82 | 1.16 | 4.64 | 2.73 | 6.04 | 3.37 | 6.74 | 3.24 |

Note. RD = relationship dissatisfaction; PA = psychological aggression.

p < .05

p < .01.

With regard to alcohol use, 93% (n = 972) of the sample reported consuming at least one drink in the past 90 days, and approximately 30% (n = 319) reported drinking at least four drinks on one occasion. Among those who drank, the mean was 8.37 standard drinks per week (SD = 10.47). Those who reported binge drinking did so, on average, about twice per week (M= 1.92, SD= 1.22), and drank about 5.9 (SD=2.74) standard drinks on days that they engaged in binge drinking.

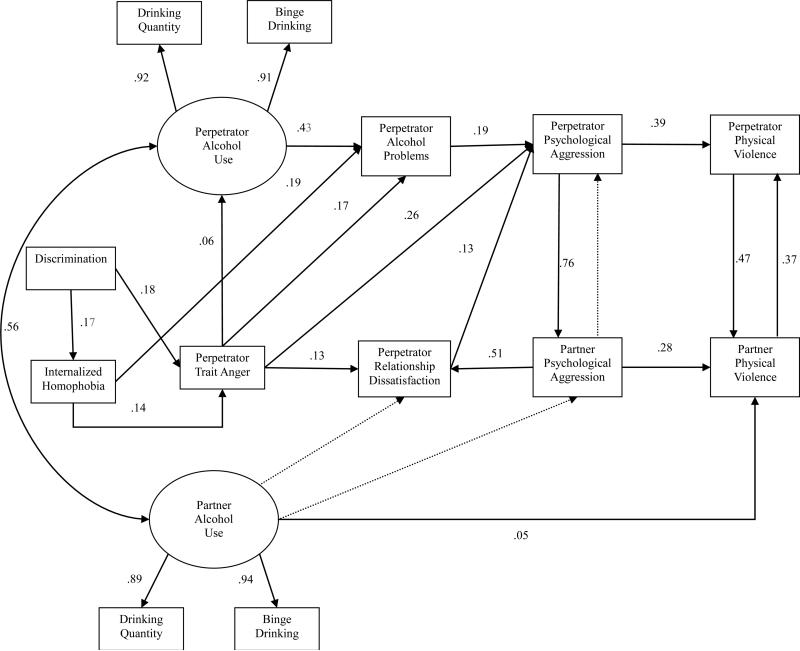

To evaluate the hypotheses and test our conceptual model (see Figure 1), structural equation modeling (SEM) with Mplus 7.1 was used (Muthén & Muthén, 2013). Missing data were handled through full information maximum likelihood estimation. Two latent variables were constructed: perpetrator alcohol use (consisting of perpetrator drinking quantity and perpetrator binge drinking) and partner alcohol use (consisting of partner drinking quantity and partner binge drinking) (see Figure 2 for standardized factor loadings). The structural model proposed and tested in hypothesis 1 demonstrated good model fit, χ2 (52) = 243.04, p < .001, CFI = .97, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .06, and SRMR = .04. All fit indices met the recommended cutoffs (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Figure 2.

Structural model of partner and perpetrator IPV in lesbian relationships. Solid lines denote significant paths and dashed lined indicate non-significant paths.

Significance testing was done using 95% bias-corrected (BC) confidence intervals (CIs) generated from 5,000 bootstrap samples for both direct effects. BC confidence intervals are presented in Table 3. If the confidence interval did not include 0, then it was significant. The model explained 3% of the variance in internalized homophobia, 6% of the variance in perpetrator anger, 28% of the variance in perpetrator alcohol problems, 40% of the variance in relationship dissatisfaction, 73% of the variance in partner psychological aggression, 55% of the variance in perpetrator psychological aggression, 61% of the variance in partner physical violence, and 60% of the variance in perpetrator physical violence.

Table 3.

Path Estimates with Bootstrapped SEs and CIs

| Path | β | B | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Paths | |||

| Discrimination→ IH | .17 | .81 | [.44, 1.20] |

| Discrimination → Anger | .18 | .55 | [.35, .74] |

| IH→ Anger | .14 | .09 | [.05, .13] |

| IH→Perpetrator alcohol problems | .19 | .20 | [.09, .31] |

| Anger→ Perpetrator alcohol use | .06 | .02 | [.001 .04] |

| Anger→ Perpetrator alcohol problems | .17 | .28 | [.18, .39] |

| Anger→ Relationship dissatisfaction | .13 | .13 | [.07, .19] |

| Anger→ Perpetrator psychological aggression | .26 | .55 | [.42, .75] |

| Perpetrator alcohol use →Perpetrator alcohol problems | .43 | 2.00 | [1.50, 2.58] |

| Partner alcohol use→ Perpetrator relationship dissatisfaction | -.04 | -.11 | [-.23, .03] |

| Partner alcohol use → Partner psych aggression | .03 | .19 | [-.10, .61] |

| Partner alcohol use → Partner phys violence | .05 | .16 | [-.14, .58] |

| Perpetrator alcohol problems→ Perpetrator psych aggression | .19 | .26 | [.10, .39] |

| Perpetrator relationship dissatisfaction → Perpetrator psych aggression | .13 | .30 | [.02, .60] |

| Perpetrator psych aggression → Partner psych aggression | .76 | .84 | [.67, 1.00] |

| Perpetrator psych aggression→Perpetrator phys violence | .39 | .22 | [.13, .35] |

| Partner psych aggression → Perpetrator relationship dissatisfaction | .51 | .21 | [.17, .25] |

| Partner psych aggression → Partner phys violence | .28 | .14 | [.07, .23] |

| Partner psych aggression → Perpetrator psych aggression | .21 | .19 | [-.17, .35] |

| Perpetrator phys violence → Partner phys violence | .47 | .45 | [.14, .69] |

| Partner phys violence → Perpetrator phys violence | .37 | .39 | [.07, .63] |

Note. psych = psychological; phys = physical.

Sexual minority discrimination contributed to higher internalized homophobia and perpetrator anger. Internalized homophobia contributed to greater perpetrator anger and perpetrator alcohol problems. Perpetrator anger was associated with more perpetrator alcohol problems, which in turn was associated with perpetrator psychological aggression and more perpetrator relationship dissatisfaction. Perpetrator alcohol use contributed to increased perpetrator alcohol problems and perpetrator alcohol problems contributed to increased perpetrator psychological aggression. Perpetrator psychological aggression was associated with more perpetrator physical violence and, similarly, partner psychological aggression was associated with more partner physical violence. Partner alcohol use was related to greater partner physical violence.

With regard to hypothesis 2, based on bivariate correlations, reports of perpetration and victimization for psychological aggression and physical violence were both highly related (r's = .86 and .79, respectively). In the model, the path from perpetration of psychological aggression to victimization of psychological aggression was significant but the opposite directional path was not significant. The paths for perpetration and victimization of physical violence were significant in both directions, demonstrating bi-directionality.

Discussion

The results supported the conceptual model (hypothesis 1) demonstrating that the sexual minority stressors of discrimination and internalized homophobia are associated with lesbian women's increased anger that is in turn associated with physical IPV via perpetrator and partner alcohol use, perpetrator alcohol problems, relationship dissatisfaction, and psychological aggression. Hypothesis 2 was partially supported in that physical IPV was bidirectional. Although perpetrator and partner psychological aggression were highly correlated, they were not bidirectional in the final model. The overall model results suggest that sexual minority stress may be a risk factor of particular relevance to lesbians that is associated with alcohol use and anger, which may ultimately be associated with acts of relationship violence.

Anger was associated with perpetrator alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. Anger and alcohol-related problems were associated with IPV, by way of psychological aggression. Both anger and hazardous alcohol use have been implicated as risk factors for IPV in heterosexual couples (e.g., Finkel & Eckhardt, 2013; Maldonado, Watkins, & DiLillo, 2015). This is the first study to our knowledge to associate these variables with IPV among lesbian women. In our sample of partnered lesbian women between the ages of 18 and 35, more than 90% reported drinking alcohol, and 30% reported engaging in binge drinking (4 drinks on one occasion) at least once in the past 90 days. Further, the typical binge drinker in our sample did so an average of twice per week and drank just under 6 standard drinks during a binge episode. Our results are consistent with studies that have shown that lesbian identity is associated with greater likelihood of hazardous drinking (e.g., Hughes et al., 2006; McCabe, Hughes, Bostwick, West, & Boyd, 2009) and point to the importance of alcohol use as a risk factor for IPV among young lesbian women.

As expected, relationship satisfaction was an important predictor of physical IPV via psychological aggression. These findings are similar to O'Leary et al. (2007) who found that marital adjustment predicted partner aggression via dominance/jealousy. Counter to expectations, partner alcohol use was not related to perpetrator relationship satisfaction or partner psychological aggression. As predicted, however, partner alcohol use was associated with more partner physical violence.

Although partner alcohol use was associated with more partner physical violence, it was not related to perpetrator relationship satisfaction or partner psychological aggression. Alcohol use is often considered a risk factor for IPV, yet research suggests that it is not alcohol use per se, but rather alcohol problems that is most predictive of IPV. For instance, Stuart et al. (2006) found partner alcohol problems predicted relationship discord and both partner psychological aggression and physical abuse among heterosexual women arrested for domestic violence. In a community sample of heterosexual couples, women's own alcohol use was associated with relationship aggression after controlling for demographic variables only, but was no longer significant after other predictors of aggression were considered, such as husband's alcohol use and women's anger (Leonard & Senchak, 1996).

Participants reported their own and their partners’ alcohol use. Despite the inherent limitation of one partner reporting on another's drinking, few models of women's IPV perpetration consider both perpetrator and partner alcohol use (Leonard & Senchak, 1996 and Stuart et al., 2006 are exceptions). The literature for heterosexual partners suggests that partner drinking patterns is associated with relationship adjustment (see review by Fischer & Wiersma, 2012), which is typically proximal to IPV in many models. Recent findings that discrepant drinking patterns in lesbian women are associated with poorer relationship adjustment (Kelley, Lewis, & Mason, 2015) suggest that both perpetrator and partner alcohol use merit consideration in future models of IPV in lesbian women.

Consistent with research among heterosexual couples (Follingstad, 2009; Schumacher & Leonard, 2005) and as hypothesized, we found that psychological aggression preceded physical violence and psychological aggression and physical violence were associated. Also consistent with research in community samples of heterosexual (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., 2012; Lawrence, Yoon, Langer, & Ro, 2009) and lesbian couples (Matte & Lafontaine, 2011) physical violence was bidirectional (hypothesis 2). We did not find evidence for bi-directionality for psychological aggression given the nonsignificant path from victimization of psychological aggression to perpetration of psychological aggression. However, the magnitude of the path from victimization of psychological aggression to perpetration of psychological aggression was similar to other significant paths that were detected (standardized path = .21). Because relationship satisfaction is strongly associated with psychological aggression, only having reports of perpetrator relationship satisfaction may have affected the ability to find the bidirectional relationship between perpetration and victimization of psychological aggression in the model.

Limitations

Although we found support for the hypothesized conceptual model, the data collected to test this model are cross-sectional limiting our ability to confirm directionality. Therefore, replication of these findings with longitudinal data is also necessary. Also, approximately 29% of eligible participants did not complete the survey. The nature of data collection from the online market research firm did not permit us to examine characteristics of completers vs. noncompleters to see if there were systematic differences between these groups.

Ours was a convenience sample that was fairly well educated, mainly White, and relatively open about their sexual identity. As a result, we cannot generalize the findings to a more diverse sample or to those who are more likely to conceal their identity. Also, participants completed measures for themselves and their partners, creating measurement error in the partner measures. Although the high correlations found between perpetration and partner psychological aggression and physical aggression may reflect bidirectional IPV, items were paired such that respondents reported on their own followed by their partners’ aggressivbehaviors. This format of data collection may have increased the likelihood of reporting bidirectional IPV.

Research Implications

Future research will benefit from collecting data from both members of the couple in order to reduce potential bias associated with one partner reporting on another's behavior. Understanding the contribution of discrimination and minority stress to negative outcomes, such as anger, alcohol abuse, and psychological aggression and physical violence, is critical for populations such as lesbians, who experience stigma and prejudice. Future research should continue to explore these population-specific variables as well as possible buffers, such as social support or community resources, that may help in mitigating the effects of minority stress.

Clinical and Policy Implications

Recent reviews have identified the lack of empirical research on intervention for same-sex IPV (e.g., Edwards et al., 2015). Cannon and Buttell (2015) note that conceptual models of same-sex IPV are necessary to develop and evaluate such interventions. Current findings suggest that addressing external and internal minority stressors and relationship issues in lesbians’ individual and couple's counseling may be useful. As with heterosexual couples, the consistent finding that alcohol plays a direct role in psychological and/or physical violence emphasizes the part that identification and treatment of alcohol use and related problems should play in addressing problems of relationship violence among lesbian women. Also, helping lesbians appreciate the connections between stressors, anger, alcohol problems, and IPV may assist them in breaking these links and/or developing mechanisms to cope with stressors in less destructive ways.

Although there has been ample support of the negative effects of sexual minority stress on individual mental health, current findings demonstrate another potential downstream negative consequence of discrimination for lesbian women, namely IPV. Although the current study assessed individual perceived discrimination, institutional discrimination (i.e., structural stigma) has also been shown to be associated with negative health outcomes for sexual minorities (e.g., Hatzenbuehler, 2014). Social policies that reduce discrimination against sexual minority individuals may in the long run contribute toward reducing IPV, although it will be necessary to examine this in future research.

Conclusion

The current study offers the first conceptual model of IPV in a community sample of lesbian women incorporating both sexual minority specific and general risk factors. Consistent with research among heterosexual couples, we confirmed the role of perpetrator anger, alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, relationship dissatisfaction, and psychological aggression in interpersonal physical violence. We also confirmed the association of partner alcohol use and partner physical violence. The sexual minority specific variables of discrimination and internalized homophobia are also important contributors to the model, suggesting that these components are unique aspects to understanding relationship violence among lesbian women.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under award number R15AA020424 to author RJL (PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The Harris Interactive Service Bureau (HISB) was responsible solely for the data collection in this study. The authors were responsible for the study's design, data analysis, reporting the data, and data interpretation.

A portion of this research was presented at the 2015 American Psychological Association annual convention in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

References

- Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Ivey MA, Habing B, Lynch KG. Reliability and validity of the alcohol short index of problems and a newly constructed drug short index of problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:304–307. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badenes-Ribera L, Frias-Navarro D, Bonilla-Campos A, Pons-Salvador G, Monterde-i-Bort H. Intimate partner violence in self-identified lesbians: A meta-analysis of its prevalence. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2015;12:47–59. doi: 10.1177/1524838015584363. doi:10.1007/s13178-014-0164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Szymanski DM. Relationship quality and domestic violence in women's same-sex relationships: The role of minority stress. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:258–269. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00220.x. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB, Smith BD. Refining the architecture of aggression: A measurement model for the Buss–Perry aggression questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality. 2001;35:138–167. doi:10.1006/jrpe.2000.2302. [Google Scholar]

- Busby DM, Christensen C, Crane DR, Larson JH. A revision of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale for use with distressed and nondistressed couples: Construct hierarchy and multidimensional scales. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1995;21:289–308. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1995.tb00163.x. [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Perry M. The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:452–459. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon C, Buttell F. Illusion of Inclusion: The Failure of the Gender Paradigm to Account for Intimate Partner Violence in LGBT Relationships. Partner Abuse. 2015;6:65–77. doi:10.1891/1946-6560.6.1.65. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:231–280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. doi:10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho AF, Lewis RJ, Derlega VJ, Winstead BW, Viggiano C. Internalized sexual minority stressors and same-sex intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2011;26:501–509. doi:10.1007/s10896-011-9384-2. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Eckhardt CI. Negative affect, alcohol consumption, and female-to-male intimate partner violence: A daily diary investigation. Partner Abuse. 2013;4:332–355. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.4.3.332. doi:10.1891/1946-6560.4.3.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Testa M. Daily associations among anger experience and intimate partner aggression within aggressive and nonaggressive community couples. Emotion. 2014;14:985–994. doi: 10.1037/a0036884. doi:10.1037/a0036884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB. Drinking level, neighborhood social disorder, and mutual intimate partner violence. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2007;31:1012–1019. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00382.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark CL, Schafer J. Alcohol-related problems and intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the U.S. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:1492–1501. doi:10.1097/00000374-199909000-00011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton L, Kaufman M, Fuhrel A, Cain D, Cherry C, Pope H, Kalichman SC. Examining factors co-existing with interpersonal violence in lesbian relationships. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:697–705. doi:10.1007/s10896-008-9194-3. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Desai AD, Gidycz CA, VanWynsberghe A. College women's aggression in relationships: The role of childhood and adolescent victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2009;33:255–265. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01498.x. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards K, Sylaska K. The perpetration of intimate partner violence among LGBTQ college youth: The role of minority stress. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2013;42:1721–1731. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9880-6. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9880-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Sylaska KM, Neal AM. Intimate partner violence among sexual minority populations: A critical review of the literature and agenda for future research. Psychology of Violence. 2015;5:112–121. doi: 10.1037/a0038656. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JL, Wiersma JD. Romantic relationships and alcohol use. Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2012;5:98–116. doi: 10.2174/1874473711205020098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, Eckhardt CI. Intimate partner violence. In: Simpson JA, Campbell L, editors. The Oxford handbook of close relationships. Oxford University Press; New York, NY, US: 2013. pp. 452–474. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JL, Fitzpatrick J, Cleveland B, Lee J-M, McKnight A, Miller B. Binge drinking in the context of romantic relationships. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1496–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.03.004. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad DR. The impact of psychological aggression on women's mental health and behavior: The status of the field. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2009;10:271–289. doi: 10.1177/1524838009334453. doi:10.1177/1524838009334453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O'Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass N, Perrin N, Hanson G, Bloom T, Gardner E, Campbell JC. Risk for reassault in abusive female same-sex relationships. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1021–1027. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.117770. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.117770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg NG, Meyer IH. Sexual orientation disparities in history of intimate partner violence: Results from the California Health Interview survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013;28:1109–1118. doi: 10.1177/0886260512459384. doi:10.1177/0886260512459384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. doi:10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma and the health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Current Directions in Psychological Science (Sage Publications Inc.) 2014;23:127–132. doi: 10.1177/0963721414523775. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Wilsnack SC, Szalacha LA, Johnson TP, Bostwick WB, Seymour R, Kinnison KE. Age and racial/ethnic differences in drinking and drinking-related problems in a community sample of lesbians. Journal of Studies On Alcohol And Drugs. 2006;67:579–590. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, Lewis RJ, Mason TB. Discrepant alcohol use, intimate partner violence, and relationship adjustment among lesbian women and their relationship partners. Journal of Family Violence. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10896-015-9743-5. doi: 10.1007/s10896-015-9743-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keown-Belous C. Development of a scale to assess same-gender relationships (Order No. 3548843) 2012 Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1282633268). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1282633268?accountid=12967.

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Misra TA, Selwyn C, Rohling ML. Rates of bidirectional versus unidirectional intimate partner violence across samples, sexual orientations, and race/ethnicities: A comprehensive review. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:199–230. doi:10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.199. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Yoon J, Langer A, Ro E. Is psychological aggression as detrimental as physical aggression? The independent effects of psychological aggression on depression and anxiety symptoms. Violence and Victims. 2009;24:20–35. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.20. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, Simoni JM. The impact of minority stress on mental health and substance use among sexual minority women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:159–170. doi: 10.1037/a0022839. doi:10.1037/a0022839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite L, Machado LN, Lara DR. Emotional traits and affective temperaments in alcohol users, abusers and dependents in a national sample. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;163:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.021. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Senchak M. Prospective prediction of husband marital aggression within newlywed couples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:369–380. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.369. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.105.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Milletich RJ, Kelley ML, Woody A. Minority stress, substance use, and intimate partner violence among sexual minority women. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2012;17:247–256. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2012.02.004. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie J, Smith TW, Uchino B, White PH, Light KC, Grewen KM. Depressive symptoms, anger/hostility, and relationship quality in young couples. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2014;33:380–396. doi:10.1521/jscp.2014.33.4.380. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado RC, Watkins LE, DiLillo D. The interplay of trait anger, childhood physical abuse, and alcohol consumption in predicting intimate partner aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015;30:1112–1127. doi: 10.1177/0886260514539850. doi:10.1177/0886260514539850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason TB, Gargurevich M, Lewis RJ. Minority stress, mental health outcomes, and IPV. 2015. Unpublished data.

- Mason TB, Lewis RJ, Milletich RJ, Kelley ML, Minifie JB, Derlega VJ. Psychological aggression in lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals' intimate relationships: A review of prevalence, correlates, and measurement issues. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2014;19:219–234. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.04.001. [Google Scholar]

- Matte M, Lafontaine M-F. Validation of a measure of psychological aggression in same-sex couples: Descriptive data on perpetration and victimization and their association with physical violence. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2011;7:226–244. doi:10.1080/1550428x.2011.564944. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, West BT, Boyd CJ. The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the united states. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1946–1952. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163147. doi:10.2105/ajph.2009.163147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, West BT, Boyd CJ. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction. 2009;104:1333–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenry PC, Serovich JM, Mason TL, Mosack K. Perpetration of gay and lesbian partner violence: A disempowerment perspective. Journal of Family Violence. 2006;21:233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Melander LA, Noel H, Tyler KA. Bidirectional, unidirectional, and nonviolence: A comparison of the predictors among partnered young adults. Violence and Victims. 2010;25:617–630. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.617. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 1995. (NIH Publication No. 95–3911) [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén B. Mplus user's guide. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary KD, Smith Slep AM, O'Leary SG. Multivariate models of men's and women's partner aggression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:752–764. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.752. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panuzio J, DiLillo D. Physical, psychological, and sexual intimate partner aggression among newlywed couples: Longitudinal prediction of marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Violence. 2010;25:689–699. doi:10.1007/s10896-010-9328-2. [Google Scholar]

- Piggot M. Double jeopardy: Lesbians and the legacy of multiple stigmatized identities (unpublished thesis) Swinburne University of Technology; Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Quigley BM, Kearns-Bodkin JN. Longitudinal moderators of the relationship between excessive drinking and intimate partner violence in the early years of marriage. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0013250. doi:10.1037/a0013250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Leonard KE. Husbands' and wives' marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical violence as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:28–37. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.28. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.73.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma MK, Suman LN, Murthy P, Marimuthu P. State-trait anger and quality of life among alcohol users. German Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;14:60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Stuart GL, Cornelius TL. Dating violence and substance use in college students: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2011;16:541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2011.08.003. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Slep AM, Foran HM, Heyman RE, United States Air Force Family Advocacy Research Program An ecological model of intimate partner violence perpetration at different levels of severity. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28:470–482. doi: 10.1037/a0037316. doi:10.1037/a0037316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Green N, Smith D, Ward D. Marital satisfaction and marital discord as risk markers for intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:149–160. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9137-4. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi:10.1177/019251396017003001. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Meehan JC, Moore TM, Morean M, Hellmuth J, Follansbee K. Examining a conceptual framework of intimate partner violence in men and women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:102–112. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Moore TM, Elkins SR, O'Farrell TJ, Temple JR, Ramsey SE, Shorey RC. The temporal association between substance use and intimate partner violence among women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:681–690. doi: 10.1037/a0032876. doi:10.1037/a0032876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, O'Farrell TJ, Temple JR. Review of the association between treatment for substance misuse and reductions in intimate partner violence. Substance Use and Misuse. 2009;44:1298–1317. doi: 10.1080/10826080902961385. doi:10.1080/10826080902961385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Hoffman JH, Leonard KE. Female intimate partner violence perpetration: Stability and predictors of mutual and nonmutual aggression across the first year of college. Aggressive Behavior. 2011;37:362–373. doi: 10.1002/ab.20391. doi:10.1002/ab.20391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RS, Bonomi AE, Anderson M, Reid RJ, Dimer JA, Carrell D, Rivara FP. Intimate partner violence: Prevalence, types, and chronicity in adult women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30:447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.01.016. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM. The development of a measure of psychological maltreatment of women by their male partners. Violence and Victims. 1989;4:159–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM. PMWI-F (Short Versiion) and PMWI-M (Short Version) 1995 Retreived from http://sitemaker.umich.edu/pmwi/files/pmwifs.pdf.

- Walters ML, Chen J, Breiding MJ. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 findings on victimization by sexual orientation. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JE, Lawrence E. Psychological victimization as a risk factor for the developmental course of marriage. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27:53–64. doi: 10.1037/a0031137. doi:10.1037/a0031137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]