Abstract

Oxidative stress and inflammation, which involve a dramatic increase in serum amyloid A (SAA) levels, are critical in the development of atherosclerosis. Most SAA circulates on plasma HDL particles, altering their cardioprotective properties. SAA-enriched HDL has diminished anti-oxidant effects on LDL, which may contribute to atherogenesis. We determined combined effects of SAA enrichment and oxidation on biochemical changes in HDL. Normal human HDLs were incubated with SAA, oxidized by various factors (Cu2+, myeloperoxidase, H2O2, OCl−), and analyzed for lipid and protein modifications and biophysical remodeling. Three novel findings are reported: addition of SAA reduces oxidation of HDL and LDL lipids; oxidation of SAA-containing HDL in the presence of OCl− generates a covalent heterodimer of SAA and apoA-I that resists the release from HDL; and mild oxidation promotes spontaneous release of proteins (SAA and apoA-I) from SAA-enriched HDL. We show that the anti-oxidant effects of SAA extend to various oxidants and are mediated mainly by the unbound protein. We propose that free SAA sequesters lipid hydroperoxides and delays lipoprotein oxidation, though much less efficiently than other anti-oxidant proteins, such as apoA-I, that SAA displaces from HDL. These findings prompt us to reconsider the role of SAA in lipid oxidation in vivo.

Keywords: high density lipoprotein, low density lipoprotein, inflammation and atherosclerosis, apolipoprotein release, lipoprotein peroxidation kinetics, amyloid A and apolipoprotein A-I amyloidosis, serum amyloid A

Inflammation and oxidative stress are critical in the development of atherosclerosis. Oxidation of LDL, which is promoted by LDL fusion and retention in the arterial wall (1), enhances LDL uptake by arterial macrophages (2). LDL uptake triggers a cascade of pro-inflammatory and pro-atherogenic responses, including activation of monocytes and conversion of arterial macrophages into cholesterol-laden foam cells that ultimately deposit in atherosclerotic plaques (3). HDL protects against this pathogenic process via multiple mechanisms, including reverse cholesterol transport, anti-inflammatory effects (4), and inhibition of LDL oxidation (5–7). The anti-oxidant effect of normal plasma HDL on LDL is largely attributed to HDL-associated lipolytic enzymes that hydrolyze oxidized phospholipids, such as paraoxonase 1 (PON1), as well as to apoA-I (28 kDa), the major structural and functional protein in normal plasma HDL (8, 9). During inflammation, plasma levels of HDL cholesterol and apoA-I decrease (10); moreover, HDL loses its cardioprotective and anti-oxidant properties (11). One of the main reasons for this loss of function is change in HDL protein composition during inflammation (12).

A major player in this process is serum amyloid A (SAA; ∼12 kDa), an ancient acute-phase response protein whose plasma levels increase transiently up to 1,000-fold and reach 1 mg/ml in inflammation and injury, making SAA a major plasma protein (13, 14). SAA circulates mainly on the HDL surface where it can displace other HDL-associated proteins, such as PON1 and other lipases, as well as a fraction of apoA-I (15). As a result, SAA becomes a major HDL protein during acute inflammation, thereby altering HDL metabolism and impairing its anti-oxidant activity (16, 17). Clinical, animal model, and in vitro studies show that in inflammation HDL loses its anti-oxidant effect on LDL and can become pro-oxidant (18, 19). This loss of function is attributed, in part, to high SAA levels in these HDL, which probably contributes to the emerging causal link between elevated plasma SAA and atherosclerosis (20). Furthermore, SAA forms a protein precursor of amyloid A (AA) that deposits as fibrils in AA amyloidosis, a major complication of chronic inflammation and the major human systemic amyloid disease worldwide (21, 22). Normal functions of SAA, which involve cholesterol transport via HDL, are subject of debate despite four decades of studies (22, 23). The direct effect of SAA on lipoprotein oxidation is unclear and is addressed in the current study.

In this work, we determined the combined effects of SAA enrichment and oxidation by various oxidative agents on the biochemical and biophysical modifications in HDL and LDL, with the main focus on HDL. Concurrently, Sato et al. (24) reported, for the first time, that human SAA retards the copper-induced oxidation of HDL and LDL. Together, these results indicate that SAA partially compensates for the loss of anti-oxidant HDL proteins, suggest a new physiological function for SAA as a mild anti-oxidant for lipids, and shed new light on the complex role of SAA in lipid oxidation and human disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Recombinant murine SAA1.1 (103 amino acids, 11.6 kDa), which is a major amyloidogenic isoform that binds HDL, was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as previously described (25). Murine SAA1 shares 75% amino acid sequence identity with human SAA1, but has more polar N-terminal residues 1-9, which improves protein solubility [(26) and references therein]. Monoclonal antibodies for apoA-I (#MAC20-001), apoA-II (#K45890G), and SAA (#H86177M) were from Meridian Life Sciences. Monoclonal antibody for oxidized phospholipid, E06 (#330001), was from Avanti Polar Lipids. Cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) purified from human plasma was a generous gift of Dr. Kerry-Ann Rye (University of New South Wales, Australia). Human myeloperoxidase (MPO) was from Calbiochem (lot #EC1.11.1.7); MPO purity assessed by SDS-PAGE was >95%, and the purity index was A430/A280 = 0.75. Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl; <5% chlorine) was from Across Organic; the HOCl concentration was determined spectrophotometrically using the extinction coefficient ε290 = 350 M−1·cm−1 (27). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; 30% solution) was from American Bioanalytical. All chemicals were of highest purity analytical grade.

Isolation of lipoproteins and apoA-I

Human lipoproteins were isolated from plasma of four anonymous healthy volunteers. The plasma was purchased from the blood bank (Research Blood Components, LLC) in full compliance with the Institutional Review Board. Single-donor lipoproteins were isolated from fresh EDTA-treated plasma by density gradient ultracentrifugation in the density range 0.94–1.006 g/ml for VLDL, 1.019–1.063 g/ml for LDL, and 1.063–1.21 g/ml for HDL following established protocols (28). Each lipoprotein fraction migrated as a single band on the agarose gel. Lipoproteins were dialyzed against standard buffer (10 mM Na phosphate, pH 7.5), degassed, and stored in the dark at 4°C. Lipoprotein stock solutions were used within 2–3 weeks during which no protein degradation was detected by SDS-PAGE and no changes in the lipoprotein electrophoretic mobility were seen on the agarose gel. ApoA-I isolated from fresh HDL was purified to ∼95% purity and refolded from 6 M guanidine chloride (Gdn HCl) upon extensive dialysis against standard buffer as previously described (29). apoA-I stock solution was stored at 4°C and was used within 1 month. Lack of apoA-I oxidation in the stock solution was verified by mass spectrometry as described below.

Preparation and characterization of SAA·HDL

HDL (0.5 mg/ml apoA-I concentration) was incubated with SAA at 37°C for 3 h in standard buffer; initial SAA:apoA-I molar ratios ranged from 0.5:1 to 4:1, which mimics the in vivo range found in inflammation (30). The total incubation mixture containing SAA-enriched HDL particles and the excess unbound protein is termed SAA·HDL(total) in this study. At 0.5:1 SAA:apoA-I molar ratio, most SAA and apoA-I was bound to HDL; increasing the SAA:apoA-I ratio to 1:1 and beyond progressively increased the fraction of the released apoA-I and excess unbound SAA detected by native PAGE (Fig. 1A) (30). HDL particles isolated from the total incubation mixture are termed SAA·HDL. Nonmodified native HDL (nHDL) particles from the same donor, which were treated identically to SAA-enriched HDL, were used as a control.

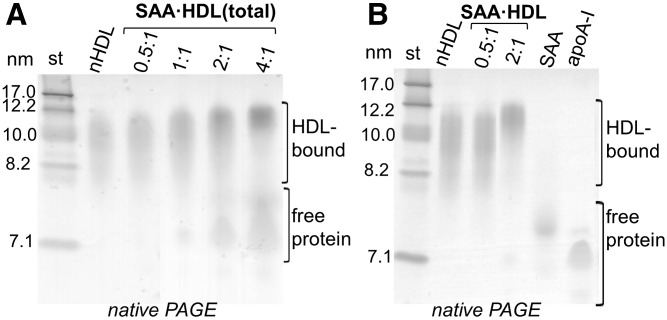

Fig. 1.

Particle size of SAA-enriched HDL and protein distribution between HDL-bound and unbound (free) forms. A: Native PAGE (4–20% Tris-glycine gel, Denville Blue protein stain in all gels) of the total incubation mixture, SAA·HDL(total). SAA:apoA-I mol:mol ratios are indicated. nHDL is shown for comparison. B: Native PAGE of SAA·HDL particles that have been isolated by density gradient centrifugation from the total mixture as described in the Materials and Methods. Lipid-free apoA-I and SAA, which is aggregated under these conditions, are shown for comparison.

SAA-enriched HDL particles, termed SAA·HDL, which were prepared at 0.5:1 or 2:1 SAA:apoA-I molar ratio, were isolated from the total mixture by density gradient centrifugation at d = 1.21 g/ml. SAA·HDL was recovered in the top 1 ml fraction (d = 1.06–1.13 g/ml) and was dialyzed against the standard buffer. Native PAGE showed that, compared with nHDLs, the size of SAA·HDL particles was invariant at 0.5:1, but increased at 2:1 mol:mol SAA:apoA-I (Fig. 1B), which is consistent with the previous studies and probably reflects additional protein bound to SAA·HDL at 2:1 SAA:apoA-I molar ratio (30).

The protein concentration was determined by a modified Lowry assay. The SAA to apoA-I ratio in SAA·HDL was estimated from the calibration plot using 10–20% SDS-PAGE. Briefly, known amounts of apoA-I and SAA were run on SDS-PAGE, the bands were quantified using Image J software (31), and a calibration curve was constructed by averaging band intensities obtained from five independent gels. SAA·HDLs and nHDLs were loaded in various amounts from 5 to 15 μg total protein, and their band intensities were compared with those of standard bands. The results obtained by this method were reproducible within 5% error. The initial protein molar ratios in SAA·HDL(total) (0.5:1 and 2:1 SAA:apoA-I) were close to the final molar ratios in SAA·HDL (0.45:1 and 1.8:1) measured by this method (30).

Preparation of SAA:DMPC complexes

The complexes were reconstituted by incubating SAA with multilamellar vesicles of DMPC (1:4 w/w protein:lipid ratio) overnight at 25°C. After incubation, the samples were spun down to pellet any unbound lipid as previously described (30).

Lipoprotein oxidation

HDL was oxidized by nonenzymatic factors (Cu2+, H2O2) or by MPO in the absence or in the presence of chloride following established protocols (31–34). For copper-induced oxidation, HDL solution of 0.1 mg/ml protein concentration was equilibrated at 37°C, and the oxidation was initiated by adding CuSO4 to 10 μM final concentration. The time course of lipid peroxidation at 37°C was monitored continuously by absorbance [optical density (OD)] at 234 nm, OD234, using Varian Cary-300 UV/vis spectrometer with thermoelectric temperature control. The increase in OD234 reflects mainly the conjugated diene formation upon oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids, followed by generation of oxysterols (35). The reaction was stopped with 1 mM EDTA and 10 μM BHT, followed by sample cooling on ice. HDL that has been incubated in this manner with CuSO4 for 100 min is termed ox·HDL.

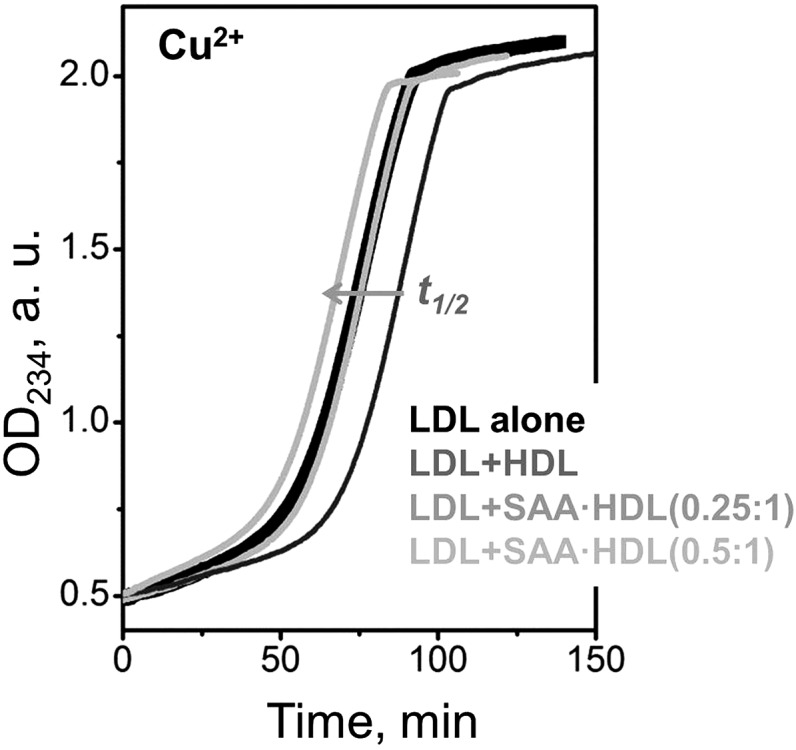

Copper-induced LDL oxidation was monitored continuously by OD234 in a similar manner (35, 36). LDL (0.1 mg/ml protein) was incubated with 10 μM CuSO4 at 37°C with or without HDL (0.1 mg/ml protein), and OD234 was measured for up to 12 h.

To selectively oxidize HDL proteins with minimal lipid modifications, hypochlorite (OCl−) was used. HDL (0.5 mg/ml protein in standard buffer) was incubated for 1 h at 37°C with NaOCl using an oxidant to protein molar ratio of 10:1 (37). The reaction was terminated with 2.5 mM methionine. The samples were dialyzed overnight against standard buffer at 4°C. Lack of major lipid oxidation was confirmed by OD234 and by the dot blot using E06 antibody specific to oxidized phosphatidylcholine (38). Mildly oxidized HDLs obtained by this method are marked “mox” in figures.

For MPO-induced oxidation, HDL solution (0.5 mg/ml protein) was dialyzed against 50 mM Na phosphate buffer at pH 7.5 containing 0.1 mM diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid, and MPO was added to a final concentration of 60 nM. The reaction was initiated by adding 50 μM H2O2 in three aliquots at 15 min intervals. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. A 100-fold excess of L-methionine was added to quench the reaction (39). MPO/H2O2/Cl−-catalyzed oxidation was carried out following a similar protocol, except that HDL solution contained 150 mM NaCl.

Statistical analysis of lipoprotein oxidation by copper

The kinetic data of lipoprotein oxidation, OD234(t), were approximated by a sigmoidal function to obtain the transition midpoint, t1/2; the maximal rate of accumulation of absorbing products, Vmax, was determined from the first derivative of the sigmoidal curve. The values of t1/2 (in minutes) and Vmax (in OD units per minute), which were obtained from three to five independent measurements, were used for the statistical analysis. Statistically significant differences were assessed by the t-test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. ORIGIN software was used for the statistical analysis and display of the data.

HDL remodeling

To probe the effects of SAA on the protein dissociation and particle fusion, which occurs during normal metabolic remodeling of plasma lipoproteins, three methods were used that have been previously shown to induce such remodeling in nHDL: i) chemical denaturation by Gdn HCl (40); ii) remodeling by CETP that transfers cholesterol esters and TGs among plasma lipoproteins (41); and iii) spontaneous HDL remodeling under ambient conditions at 37°C (42).

For remodeling by a denaturant, nHDL and SAA·HDL were incubated with 3 M Gdn HCl at 37°C for 3 h, followed by extensive dialysis against standard buffer. For remodeling by CETP, nHDL and SAA·HDL (final protein concentration 1 mg/ml) were incubated with VLDL as a source of TG (final TG concentration 5 mM) and CETP (final activity of 5 units/ml) in standard buffer at 37°C for 24 h. The samples were placed on ice to terminate the reaction, followed by fractionation by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). The isolated fractions were concentrated for further studies. For spontaneous remodeling, nHDL and SAA·HDL were incubated for 12 h at 37°C in 20 mM MES buffer at pH 5.5.

Gel electrophoresis, immunoblotting, and SEC

For native PAGE, Novex™ 4–20% Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen) were loaded with 6 μg protein per lane and run to termination at 1,500 V · h under nondenaturing conditions in Tris-glycine buffer. For SDS-PAGE, Novex™ 4–20% Tris-glycine gels were loaded with 5 μg protein per lane and run at 200 V for 1 h under denaturing conditions in SDS-Tris-glycine buffer. The gels were stained with Denville Blue protein stain (Denville Scientific).

For Western blotting, the proteins were separated either on native or on SDS gels and were transferred to PVDF membranes at 100 V for 1 h at 4°C. The membranes were blocked for 1 h in Tris-buffered saline/casein blocking buffer. The blots were probed with antibodies for apoA-I, apoA-II, or SAA in blocking buffer for 1 h. The blots were washed three times for 10 min each and were visualized using an ECL system (NEN Life Science Products).

Phospholipid oxidation in lipoproteins was monitored by dot blot analysis. HDLs were incubated with the oxidant for various amounts of time for up to 12 h, and 10 μl of HDL sample (0.5 mg/ml protein concentration) was deposited on a nitrocellulose membrane. To ensure that the protein load was comparable in different dots, the membrane was stained with Ponceau-S protein stain. The stain was washed off, the membrane was blocked with fat-free milk, and was reacted with the E06 antibody. HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was used for detection.

SEC was performed with a Superose 6 10/300 GL column controlled by an AKTA UPC 10 FPLC system (GE Healthcare). Samples were eluted in PBS at pH 7.5 at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min.

Mass spectrometry

For MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, the spectra were recorded on a Reflex-IV spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA) equipped with a 337 nm nitrogen laser. The instrument was operated in the positive-ion reflection mode at 20 kV accelerating voltage with time-lag focusing enabled. Calibration was performed in linear mode using a standard calibration mixture containing oxidized B-chain of bovine insulin, equine cytochrome C, equine apomyoglobin, and BSA. The matrix, cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (α cyano, MW 189), was prepared as a saturated solution in 70% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water. Mass spectrometry results were reported as an average of three independent experiments.

Absorption and fluorescence spectrometry

A Varian Cary-300 absorption spectrometer was used to monitor carotenoid consumption at various stages of HDL oxidation as previously described (43). Intrinsic Trp fluorescence was measured using a Fluoromax-2 spectrofluorimeter. HDLs were oxidized to various stages, and the spectra were recorded at 25°C from 310 to 450 nm using a 295 nm excitation wavelength and 5 nm excitation and emission slit widths as previously described (43).

To ensure reproducibility, all experiments reported in this study were repeated from four different HDL batches (each batch from a different human donor), three or more times for each batch. All gel data were repeated five times for each lipoprotein batch.

RESULTS

Addition of SAA decreases copper-induced oxidation of HDL

First, we determined the effect of SAA on copper-induced HDL oxidation. Figure 2A shows the time course of lipid peroxidation during incubation of nHDL or SAA·HDL with Cu2+. nHDL showed characteristic oxidation kinetics, with a lag phase during which antioxidants were consumed, a steep propagation phase when lipid hydroperoxides were rapidly generated (observed after ∼25 min in Fig. 2A), and a saturation phase (observed after 50 min in Fig. 2A). SAA·HDL obtained at 0.5:1 SAA:apoA-I molar ratio showed similar oxidation kinetics. However, at 2:1 SAA:apoA-I ratio, the propagation phase in SAA·HDL was blocked and was not observed even after more than 200 min of incubation (line 2:1, Fig. 2A; supplemental Fig. S1). This result was surprising because it is well-documented that HDLs enriched with SAA lose their anti-oxidant effects on LDLs and may even become pro-oxidant (18, 19) (see the Discussion for details).

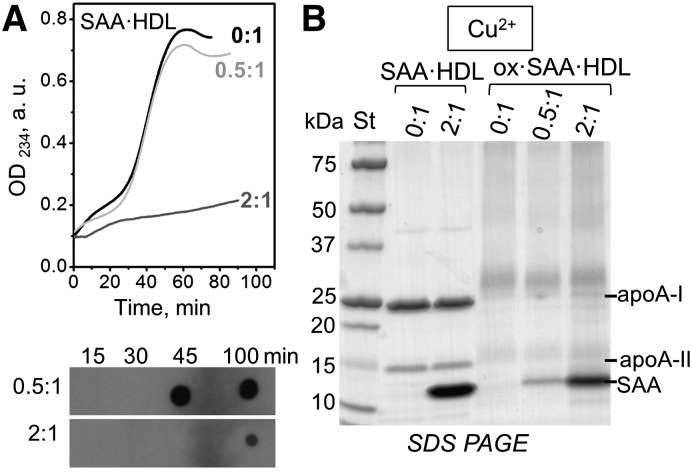

Fig. 2.

Effects of SAA on HDL oxidation by Cu2+: biochemical changes. A: Time course of lipid oxidation in SAA·HDL prepared at SAA:apoA-I molar ratios of 0.5:1 or 2:1 (indicated); 0:1 designates nHDL in all figures. CuSO4 (10 μM) was added to HDL solutions containing 0.1 mg/ml protein at time t = 0. Top panel: The time course of conjugated diene formation monitored by absorbance at 234 nm, OD234. Bottom panel: Aliquots of Cu2+-oxidized samples were collected at the indicated time points and analyzed by dot blot with EO6 antibody for phospholipid oxidation that follows accumulation of conjugated dienes. B: SDS-PAGE of nonoxidized and oxidized nHDL and SAA·HDL. The particles were incubated with 10 μM CuSO4 for 100 min as described in the Materials and Methods. The major HDL proteins are indicated. In all figures “apoA-II” stands for the ∼17 kDa disulfide-linked dimer that is predominant in human plasma.

To determine whether this unexpected inhibitory effect of SAA on the peroxidation of HDL lipids involved biochemical changes in HDL proteins, we used SAA·HDL at 2:1 SAA:apoA-I molar ratio to assess protein modifications upon HDL incubation with Cu2+. Previous studies of normal HDL showed that such incubation leads to cross-linking of the major HDL proteins, apoA-I and apoA-II (44). In our studies, SDS-PAGE of normal HDL and of SAA·HDL, which had been incubated for 100 min with Cu2+ (marked ox in the figures), showed similar cross-linking patterns (Fig. 2B). Western blots using antibodies for apoA-I, apoA-II, and SAA detected cross-links in apoA-I and apoA-II and confirmed that the cross-linking patterns in apoA-I and apoA-II in nHDL and in SAA-enriched HDL were similar at SAA:apoA-I ratios from 0:1 to 2:1 mol:mol; in the latter particles, SAA showed homo-cross-links but no hetero-cross-links (data not shown). These results show that, even though at 2:1 SAA:apoA-I molar ratio, SAA decreased copper-induced formation of conjugated dienes in HDL, it did not block radical decomposition of lipid peroxides, which mediates Lys cross-linking.

As additional probes for the lipid and protein oxidation, we used dot blot analysis along with absorption and fluorescence spectrometry to monitor HDL at various stages of copper oxidation. The stages corresponded to the lag, transition, and post-transition phases in the OD234 curve for 0.5:1 SAA:apoA-I (Fig. 2A; supplemental Fig. S2). Dot blot of SAA·HDL at 0.5:1 and 2:1 SAA:apoA-I ratios was used to monitor phospholipid oxidation (Fig. 2A, bottom), UV/vis absorption spectra monitored carotenoid consumption in the HDL core (supplemental Fig. S2A), and intrinsic Trp fluorescence spectra monitored Trp oxidation (supplemental Fig. S2B) as previously described (43). The results revealed that increasing the SAA:apoA-I ratio from 0.5:1 to 2:1 greatly delayed phospholipid oxidation, carotenoid consumption, and Trp oxidation in HDL (Fig. 2A; supplemental Fig. S2). Together, these results consistently show that exogenous SAA diminishes lipid and protein oxidation in HDL.

To probe whether HDL enrichment with SAA combined with oxidation affects the biophysical remodeling of HDL, we used native PAGE and SEC to test for protein dissociation from HDL and lipoprotein fusion upon oxidation of SAA·HDL containing 0:1 to 2:1 SAA:apoA-I. Interestingly, oxidation by Cu2+ led to a spontaneous protein release from SAA·HDL under ambient conditions. The released protein was detected only in SAA-containing HDL, but not in nHDL, and showed a dose-dependent increase with increasing the SAA:apoA-I ratio from 0:1 to 2:1 (Fig. 3A, B). No major changes in the lipoprotein size were detected upon protein release, indicating the absence of HDL fusion. SDS-PAGE revealed that the proteins released from SAA·HDL contained apoA-I and SAA, but no apoA-II, which is more hydrophobic and more tightly bound to HDL (supplemental Fig. S3A). The unbound proteins were isolated by SEC (Fig. 3B) and quantified by SDS-PAGE; the results showed that they contained approximately 60% SAA and 40% apoA-I by weight. We call this unbound protein “free” to distinguish it from the HDL-bound protein, even though, similar to apoA-I, SAA released from HDL may carry lipid molecules (45).

Fig. 3.

Effects of SAA on HDL oxidation by Cu2+: lipoprotein remodeling and protein release. Representative native PAGE (A) and SEC data of oxidized SAA·HDL (B) show significant amounts of dissociated (free) protein at 2:1, but not at 0:1 SAA:apoA-I. The particles were prepared as described in Fig. 2.

MALDI-TOF analysis of free SAA and apoA-I released from oxidized SAA·HDL revealed an increase in the molecular mass of each protein by 48 Da corresponding to the addition of three oxygen atoms (see supplemental Fig. S3B for details). Such a mass increase suggests that the three Met in apoA-I and in SAA have been oxidized. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that Met oxidation augments apoA-I release from HDL (46) and suggest a similar effect for SAA, with one important distinction: the release of Met-oxidized SAA and apoA-I from SAA·HDL under ambient conditions is spontaneous, while the release of Met-oxidized apoA-I from HDL in the absence of SAA (Fig. 3A, B) requires additional perturbations (thermal, chemical, etc.). In summary, the results in Figs. 2 and 3 reveal that increasing SAA levels from 0:1 to 2:1 mol:mol SAA:apoA-I, which is within the range observed in plasma under normal and pro-inflammatory conditions (17), greatly delays lipid peroxidation in HDL and leads to a spontaneous release of a fraction of SAA and apoA-I from SAA·HDL.

Lipid oxidation in lipoproteins is delayed upon addition of free apolipoproteins such as apoA-I (7, 9, 47). To determine whether free SAA causes a similar delay, we analyzed the dose-dependent effects of SAA on the kinetics of copper-induced oxidation in the total incubation mixture of SAA and HDL. HDL (0.5 mg/ml apoA-I) was incubated for 3 h at 37°C with SAA at various concentrations corresponding to SAA:apoA-I molar ratios from 0.5:1 to 4:1, and the resulting SAA·HDL(total) was analyzed. Native PAGE showed that SAA·HDL(total) contained HDL-bound and unbound protein. These two protein fractions were isolated by SEC and analyzed by SDS-PAGE; the results showed that each fraction contained both apoA-I and SAA (30). The proportion of the free protein in SAA·HDL(total), estimated from the native PAGE, increased from ∼5% at 0.5:1 SAA:apoA-I to 60% at 4:1 SAA:apoA-I [(30) and Fig. 1A]. The free protein in SAA·HDL(total) included excess SAA and apoA-I released from HDL. Importantly, increasing the SAA:apoA-I molar ratio from 0.5:1 to 1:1 and beyond prolonged the lag and progressively decreased the maximal rate (Vmax) and the maximal magnitude (ODmax) of lipid peroxidation (supplemental Fig. S4A, Fig. 4A). These results are consistent with the lack of the rapid peroxidation observed in isolated SAA·HDL at 2:1 SAA:apoA-I ratio (Fig. 2A) and show that the anti-oxidant effect of SAA on HDL lipids is dose-dependent.

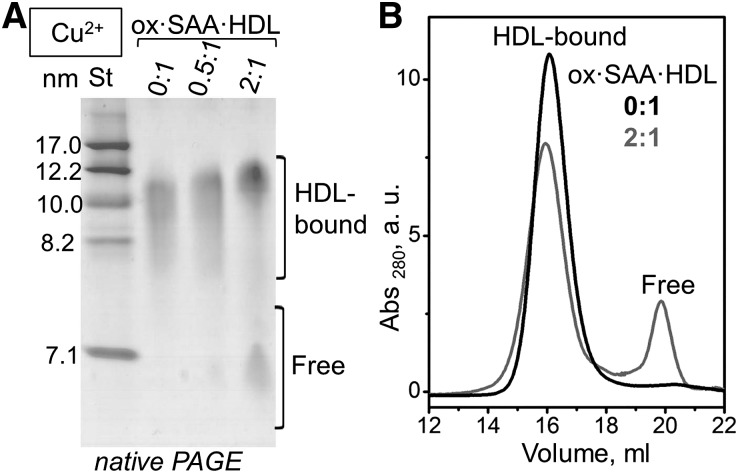

Fig. 4.

Effects of SAA on the kinetics of lipid peroxidation by Cu2+ in the total mixture of SAA with either HDL or LDL. A: SAA-enriched HDLs (0.1 mg/ml protein) at the indicated SAA:apoA-I molar ratios were incubated with 10 μM CuSO4 at 37°C; lipid oxidation was continuously monitored by OD234. B: Similar oxidation data were recorded of LDL (0.1 mg/ml apoB) either in the absence (LDL alone) or in presence of lipid-free SAA (+SAA) or lipid-free apoA-I (+apoA-I). SAA:apoB or apoA-I:apoB weight ratio was 1:1. C: Native PAGE of lipid-free SAA and of fully lipidated SAA in complexes with DMPC (marked SAA and SAA:DMPC, respectively). The SAA:DMPC complexes were prepared as previously described (30). D: Copper oxidation data recorded of LDL (0.1 mg/ml apoB) and HDL (0.1 mg/ml total protein) in the absence or in the presence of SAA:DMPC complexes. SAA:apoB and SAA:apoA-I weight ratio was 1:1.

Notably, prolonged lag accompanied by a decrease in Vmax were detected in SAA·HDL(total) (Fig. 4A) and in SAA·HDL at SAA:apoA-I ratios above 0.5:1 (Fig. 1A) when a substantial fraction of SAA and apoA-I was unbound (30). We reasoned that this unbound protein was at least partially responsible for the observed decrease in the HDL lipid peroxidation, and tested this idea as described below.

Free SAA delays LDL lipid peroxidation by copper

To clearly distinguish the effect of the unbound SAA on lipoprotein oxidation without the interference from apoA-I, LDL was incubated with lipid-free SAA and then incubated with Cu2+ for 100 min. In each LDL particle, one apoB molecule (550 kDa) comprises >95% of the total protein mass, and there is little or no apoA-I. Importantly, in these experiments, SAA does not bind to normal LDL, as confirmed by native PAGE and immunoblotting (data not shown). Therefore, LDL provides a useful system to determine how free SAA affects the kinetics of lipid peroxidation.

Figure 4B shows the data recorded from a mixture of LDL with SAA containing 0.1 mg/ml apoB and 1:1 SAA:apoB (w/w). Similar data for a mixture of LDL with free apoA-I at 1:1 apoA-I:apoB (w/w) are shown for comparison. Upon addition of free SAA, LDL showed a prolonged lag and a decreased maximal rate of oxidation, Vmax. Notably, apoA-I extended the lag phase of LDL even more than SAA (Fig. 4B; for a statistical analysis see supplemental Fig. S4).

Although the anti-oxidant effect of apoA-I on LDL is well-established, to our knowledge this is one of the first reports of a similar, but smaller, effect of free SAA on LDL (Fig. 4B), along with a very recent study by Sato et al. (24) reporting that SAA decelerates copper-induced LDL oxidation. Both our study and the study by Sato et al. also show that SAA decelerates copper-induced HDL oxidation in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 2A, 4A). Furthermore, our results suggest that the prolonged lag and decreased Vmax of lipid oxidation observed in SAA·HDL and in SAA·HDL(total) are due, at least in part, to the unbound SAA. To further test this idea, we used fully lipidated SAA in the form of SAA:DMPC complexes (Fig. 4C). The complexes were prepared as previously described (30). In stark contrast with free SAA, addition of fully lipidated SAA had little effect on the oxidation time course of either HDL or LDL (Fig. 4D). This result supports our idea that the anti-oxidant effect of SAA is exerted mainly by the unbound protein.

In summary, our results together with the recent study by Sato et al. (24) revealed that SAA can retard copper-induced lipid peroxidation in HDL (Figs. 2A, 4A; supplemental Fig. S1) and LDL (Fig. 4B), though less efficiently than apoA-I (Fig. 4B). This anti-oxidant effect is due fully (for LDL) or at least in part (for HDL) to unbound (free) SAA.

SAA delays MPO-mediated HDL oxidation and forms a heterodimer with apoA-I in the presence of Cl−

Next, we explored the effect of SAA on the HDL oxidation by MPO, which mediates lipoprotein oxidation in the arterial wall (48). MPO uses hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, as a substrate to generate halogenating and nitrating intermediates in vivo (49–51). In particular, MPO uses H2O2 and Cl− to generate hypochlorous acid, OCl− (51). This aspect of the MPO reaction can be mimicked by using NaOCl in vitro. Chemical modifications produced by these reagents have been previously determined for the two major HDL proteins, apoA-I and apoA-II (43, 52), but not for SAA. We determined the effects of SAA on HDL modifications by OCl− upon nonenzymatic or enzymatic oxidation using NaOCl or MPO/H2O2/Cl−, respectively. We carefully chose incubation conditions (1:10 protein:OCl− molar ratio at 37°C for 1 h) that produced significant protein oxidation and cross-linking, but minimal lipid oxidation in HDL. The latter was verified by the lack of changes in OD234 (data not shown) and by a negative reaction with the EO6 antibody (Fig. 5C, 1 h). The particles produced by this method, termed mox·HDL, mimicked mildly oxidized HDL formed in vivo during inflammation (50). These particles were used to determine the combined effects of SAA and mild oxidation on HDL proteins.

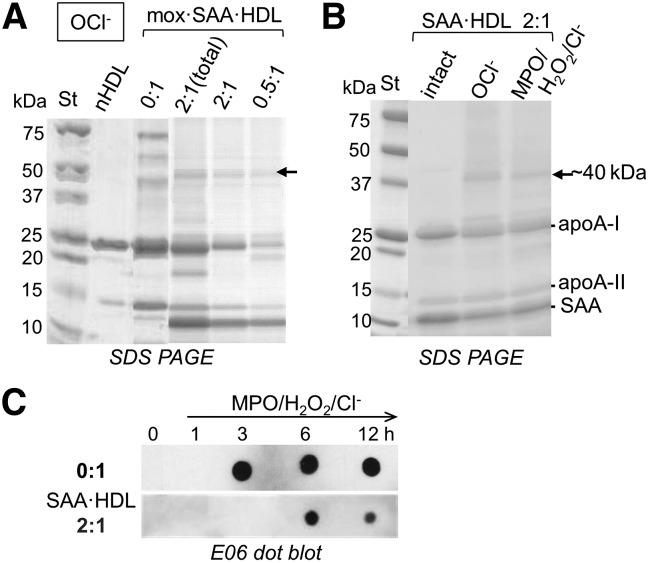

Fig. 5.

Mild oxidation of HDL proteins and lipids by using OCl−. A: SAA-enriched HDL, which was prepared at the indicated SAA:apoA-I molar ratios, was oxidized using OCl− as described in the Materials and Methods and was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. nHDL and native oxidized HDL (0:1) are shown for comparison. Arrow indicates the ∼40 kDa species formed upon oxidative protein cross-linking in the presence of chlorine. B: SDS-PAGE of SAA·HDLs, which were prepared at 2:1 SAA:apoA-I molar ratio and were either intact or oxidized by OCl− or by MPO/H2O2/Cl−. Major protein bands are indicated. C: End-point measurements of oxidized phospholipids. nHDL (0:1) and SAA·HDL prepared at 2:1 SAA:apoA-I (2:1) were incubated with MPO/H2O2/Cl−, and the aliquots taken after incubation for 1–12 h (hours are shown by numbers) were analyzed by dot blot using E06 antibody. After 3 h of incubation, phospholipid oxidation was detected in nHDL but not in SAA-enriched HDL.

In nHDL, mild oxidation by OCl− induces cross-linking of apoA-I and apoA-II [(43) and references therein]. Interestingly, SDS-PAGE of mox·SAA·HDL showed a ∼40 kDa band (Fig. 5A, arrow) that was also observed upon mild oxidation of SAA·HDL by MPO/H2O2/Cl− (Fig. 5B). This band was detected at 0.5:1 and at 2:1 SAA:apoA-I molar ratio in SAA·HDL, and was found both in isolated SAA·HDL and in SAA·HDL(total), but not in nHDL (Fig. 5A, 0:1), suggesting the direct involvement of SAA.

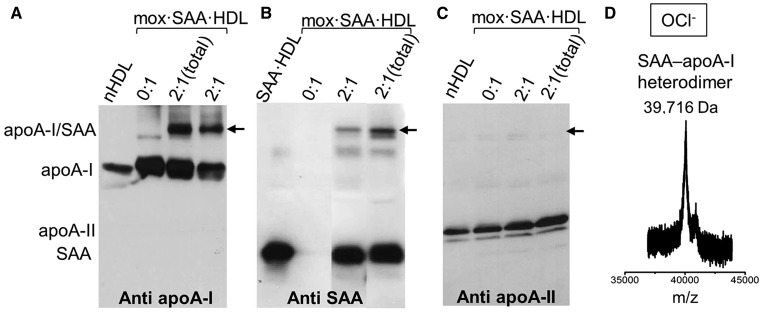

To identify the origin of this 40 kDa band, we used Western blotting and mass spectrometry to analyze SAA·HDL that had been mildly oxidized either by OCl− (Fig. 6) or by MPO/H2O2/Cl− (supplemental Fig. S5). Immunoblotting using antibodies specific to apoA-I, apoA-II, or SAA revealed that the ∼40 kDa band formed in these particles was an SAA-apoA-I heterodimer (Fig. 6, supplemental Fig. S5). The exact molecular mass of this heterodimer determined by MALDI-TOF was 39,716 Da (Fig. 6D), which corresponds to one copy of apoA-I (28,087 Da) and one copy of SAA (11,608 Da) (supplemental Fig. S3, bottom).

Fig. 6.

Protein cross-linking in mildly oxidized HDL. SAA-enriched HDL, which was prepared at the indicated SAA:apoA-I molar ratios, was mildly oxidized by OCl− (mox·SAA·HDL), followed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific for major HDL proteins: apoA-I (A), SAA (B), or apoA-II (C). Arrows indicate the position of the ∼40 kDa band corresponding to the SAA-apoA-I heterodimer. D: MALDI-TOF reveals the molecular mass of the heterodimer.

When SAA·HDL was oxidized by the peroxide radical (O22−) using MPO/H2O2 without Cl−, the SAA-apoA-I heterodimer was not observed (supplemental Fig. S6). We conclude that chlorination facilitates formation of the SAA-apoA-I heterodimer upon enzymatic or nonenzymatic oxidation of SAA·HDL. To our knowledge, such a covalent heterodimer formed by apoA-I and SAA has not been previously reported.

To determine whether the SAA-apoA-I heterodimer forms exclusively on the HDL surface, we characterized the oxidation products of lipid-free apoA-I, lipid-free SAA, and their mixture. Oxidation of free apoA-I, by using either NaOCl or MPO/H2O2/Cl−, produced a homodimer (37, 48). Oxidation of free SAA by NaOCl or MPO/H2O2/Cl− produced SAA homodimer and homotrimer (supplemental Figs. S7B, S8C). In contrast, oxidation of free SAA by MPO/H2O2 in the absence of Cl− produced no detectable cross-linking (supplemental Fig. S8B). Importantly, in contrast to SAA·HDL, no heterodimer was detected in a mixture of lipid-free apoA-I and SAA (1:1 mol:mol SAA:apoA-I) upon oxidation by any factors explored, including either NaOCl or MPO/H2O2/Cl− (supplemental Fig. S7; apoA-I+SAA). Together, these results show that the SAA-apoA-I heterodimer forms in the presence of Cl− upon oxidation of HDL-bound rather than free proteins.

Mild oxidation of SAA·HDL shifts the equilibrium from the HDL-bound to free protein

To determine whether mild oxidation of HDL proteins contributes to their spontaneous release from the SAA-containing HDL in the absence of major lipid modifications, SAA·HDL was mildly oxidized by NaOCl, MPO/H2O2/Cl−, or MPO/H2O2, followed by native PAGE and SDS-PAGE analysis. Supplemental Fig. S8A shows a representative native PAGE for the NaOCl-induced oxidation. Spontaneous release of a protein fraction upon mild oxidation of SAA·HDL, but not nHDL, was observed by using any oxidant explored (supplemental Fig. S8A, mox·SAA·HDL). SDS-PAGE of the released protein (not shown) revealed that it contained apoA-I and SAA. Therefore, spontaneous release of these proteins from SAA·HDL occurs upon mild protein oxidation in the absence of extensive lipid peroxidation.

Together, our results reveal that the combined action of HDL enrichment with SAA and mild oxidation, which mimics inflammatory conditions in vivo, shifts the population distribution from HDL-bound to unbound proteins under ambient conditions. This shift is accompanied by methionine sulfoxide [Met(O)] formation in SAA and in apoA-I, which diminishes the binding affinity of these proteins for the HDL surface.

Effects of SAA on the remodeling of oxidized HDL by various factors

Next, we determined how SAA enrichment and oxidation influence HDL remodeling by various factors, including those that remodel plasma HDL during metabolism (45). Biochemical and structural remodeling of the SAA-enriched HDL is an important determinant of HDL function in inflammation, and is particularly relevant to the oxidative environment in arteries and tissues. To mimic HDL remodeling in vivo, we used three methods: i) denaturation by Gdn HCl, ii) remodeling upon lipid transfer by CETP, and iii) spontaneous remodeling upon HDL incubation at 37°C.

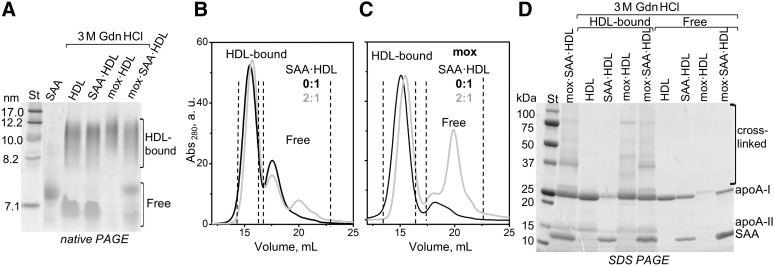

Previously we showed that the remodeling of nHDL by Gdn HCl mimics important aspects of the metabolic HDL remodeling in vivo, such as apoA-I release and HDL fusion (40). Here, we used Gdn HCl as a tool to determine the effects of SAA enrichment and HDL oxidation on such remodeling. HDL was either native or was mildly oxidized by NaOCl for 1 h (mox·HDL), or was enriched with SAA at 2:1 SAA:apoA-I molar ratio and then mildly oxidized (mox·SAA·HDL). These particles were incubated for 3 h under mild denaturing conditions (3 M Gdn HCl, 37°C), followed by native PAGE and SEC analyses.

Figure 7 shows representative data for unoxidized and mildly oxidized HDL. As expected, incubation of nHDL with Gdn HCl led to the release of a substantial fraction of apoA-I (HDL, Fig. 7A). Protein release was also observed upon Gdn HCl treatment of SAA·HDL (Fig. 7A). In contrast, mildly oxidized HDL, which contained cross-linked proteins, showed little protein liberated upon Gdn HCl treatment (mox·HDL, Fig. 7A). These results are consistent with our previous studies of nHDL showing that initial protein oxidation that was mainly limited to Met(O) formation promoted apoA-I release from HDL, while more extensive oxidation that induced protein cross-linking on HDL retarded protein release (53).

Fig. 7.

Effects of SAA enrichment and mild oxidation by OCl− on the biophysical remodeling of HDL by Gdn HCl. The lipoproteins were native (marked HDL or 0:1) or SAA-enriched at 2:1 SAA:apoA-I molar ratio (SAA·HDL). A subset of these lipoproteins was mildly oxidized (mox) by OCl− as described in the Materials and Methods. Next, the lipoproteins were incubated for 3 h at 37°C with 3 M Gdn HCl, followed by the PAGE and SEC analysis. A: Native PAGE shows substantial dissociation of free proteins from mox·SAA·HDL, but not from mox·HDL. SEC analysis of unoxidized (B) and oxidized (C) lipoproteins confirms that the combined effect of SAA enrichment and oxidation leads to dissociation of free protein (gray lines, 2:1). Dotted lines in (B, C) encompass fractions of HDL-bound and free proteins that were separated by SEC. D: SDS-PAGE of these fractions shows oxidative protein cross-linking in HDL-bound but not in free proteins.

Interestingly, in contrast to mox·HDL, in mildly oxidized SAA·HDL, a substantial fraction of SAA and apoA-I dissociated from the lipid upon incubation with Gdn HCl (mox·SAA·HDL, Fig. 7A). The HDL-bound and unbound protein fractions were isolated by SEC and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 7B–D). Cross-linked forms of apoA-I, apoA-II, and SAA, including the SAA-apoA-I heterodimer, were found exclusively in the HDL-bound fraction, while the unbound free fraction contained mainly apoA-I and SAA monomers (Fig. 7D). Together, these results show that: i) oxidative cross-linking of HDL proteins increases their retention on the HDL surface, ii) the presence of SAA on HDL promotes protein release upon mild oxidation, and iii) the released proteins contain monomeric apoA-I and SAA.

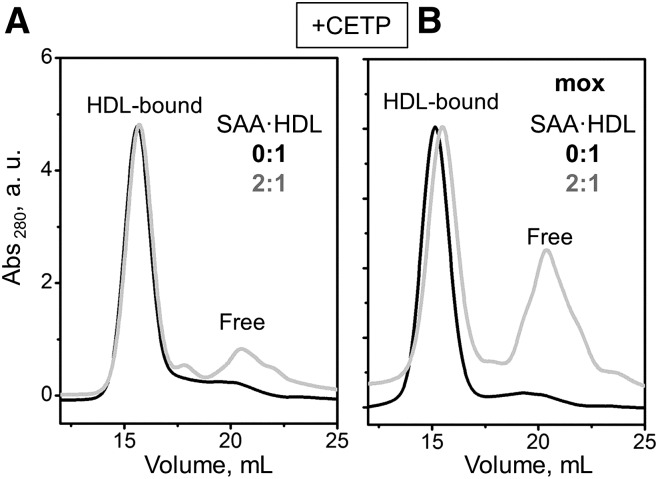

A similar trend was observed during remodeling of mildly oxidized HDL and SAA·HDL with CETP. CETP transfers cholesterol esters and TG among plasma lipoproteins, which can shift the balance between the HDL core and surface and promote apoA-I release (54). The results in Fig. 8 show that, upon CETP-induced remodeling of mildly oxidized HDL, a much larger protein fraction was released from SAA-containing particles, as compared with unmodified particles (2:1 and 0:1 SAA:apoA-I in Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Effects of SAA enrichment and mild oxidation on HDL remodeling by CETP. Native (0:1) or SAA-containing HDLs (2:1 SAA:apoA-I mol:mol) were remodeled by CETP, and a fraction of these proteins was mildly oxidized by OCl− as described in the Materials and Methods. SEC data of unoxidized (A) and oxidized (B) lipoproteins shows enhanced dissociation of free protein from the mildly oxidized particles (gray line).

Finally, a similar trend was observed during spontaneous remodeling of HDL upon incubation at 37°C at pH 5.5. We used low pH to mimic the acidity of deep hypoxic areas of atherosclerotic plaques where the pH can drop below pH 6 (55). Supplemental Fig. S9 shows representative SEC data at pH 5.5. Again, upon mild oxidation, a larger amount of proteins was released from the SAA-containing HDL as compared with the unmodified HDL.

In summary, our studies of minimally oxidized HDLs that were subjected to various perturbations (by a denaturant, a lipid transfer protein, or by incubation at 37°C) clearly show that the combined effects of SAA enrichment followed by mild oxidation promote protein release from HDL, and that the released protein includes both apoA-I and SAA monomers (Figs. 7, 8; supplemental Fig. S9). This observation may have important implications for the clearance and misfolding of these proteins in vivo.

DISCUSSION

Exogenous SAA retards the oxidation of human plasma HDL and LDL

The first surprising finding of the current work is that SAA added to HDL or LDL at physiologically relevant ratios delays lipoprotein oxidation, albeit much less efficiently than apoA-I (Figs. 2, 4). This anti-oxidant effect of SAA was observed in Cu2+ oxidation studies by several independent methods that monitored conjugate diene formation and phospholipid oxidation in HDL surface, carotenoid consumption in HDL core, and Trp oxidation in HDL proteins (Figs. 2, 4; supplemental Fig. S2). Similarly, SAA delayed HDL oxidation by MPO, which was monitored by the immunoblotting for oxidized phospholipids (Fig. 5C). These results are in excellent agreement with a recent study showing that human SAA delays Cu2+-induced lipid peroxidation in HDL and LDL (24). The authors reported that human plasma HDL, which has been either enriched with human recombinant SAA or isolated from patients’ serum with high SAA levels, showed similar dose-dependent effects of SAA in decelerating copper-induced lipid peroxidation (24). These new findings are surprising because it is well-established that normal plasma HDL acts as an anti-oxidant for LDL, and that this effect is abrogated or even reversed in inflammation in vitro (18, 19), as well as upon HDL enrichment with SAA in vitro (Fig. 9). The apparent contradiction between this well-known effect and the new findings can be resolved by considering the biochemical basis for the anti-oxidant action of normal HDL.

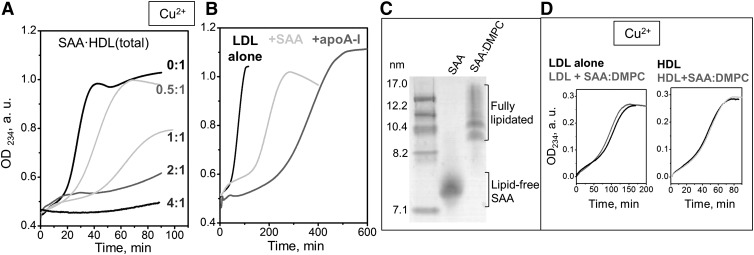

Fig. 9.

Dose-dependent effects of SAA-containing HDL on LDL oxidation by copper. Human LDL has been incubated with Cu2+ (0.1 mg/ml apoB, 10 μM CuSO4) at 37°C and lipid peroxidation was continuously monitored by absorbance at 234 nm. Addition of native human HDL at an apoB:apoA-I weight ratio of 1:1 (dark gray) prolonged the lag in LDL oxidation and significantly increased the time t1/2 corresponding to the transition midpoint. For HDLs that were enriched with SAA, this effect was abolished at 0.25:1 SAA:apoA-I molar ratio (gray line overlapping the black line for LDL alone), and was reversed at 0.5:1 SAA:apoA-I (light gray line). Gray arrow shows the direction of the dose-dependent changes in t1/2 upon increasing SAA concentration in HDL. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that HDLs lose their anti-oxidant effect on LDL and, ultimately, become pro-oxidant upon HDL enrichment with SAA in a dose-dependent manner (32, 35).

This anti-oxidant action is attributed mainly to HDL-associated lipolytic enzymes such as PON1, which degrades lipoprotein-associated lipid hydroperoxides (56), as well as the platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase and lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase, which hydrolyze oxidized phospholipids (57, 58). In addition, apoA-I also delays lipoprotein oxidation (Fig. 4B) by sequestering lipid hydroperoxides (7, 9, 47). Together, these anti-oxidant effects of HDL proteins counterbalance pro-oxidant effects of HDL lipids that contain substantial amounts of lipid hydroperoxides (35). This balance shifts in inflammation when the protective enzymes are displaced from HDL and thereby inactivated by SAA (15). As a result, the anti-oxidant action of HDL on LDL can be diminished or even reversed.

Our study, together with (24), clearly shows that SAA does not cause a direct pro-oxidant effect on lipoproteins. Moreover, SAA alone acts as an anti-oxidant for HDL and LDL in a dose-dependent manner in a range of relative protein and lipid concentrations that mimic pro-inflammatory conditions in plasma (Figs. 2A; 4A, B; 5C) (24). However, SAA is less efficient in its anti-oxidant capacity than the proteins that it displaces from HDL, such as apoA-I (Fig. 4B); hence, it can at least partially compensate for the loss of these proteins. Further support for the anti-oxidant effect of SAA emerged from a very recent population study reporting that HDL from patients with higher SAA levels has better anti-oxidant activity than controls (59).

Possible mechanisms of the anti-oxidant effect of SAA

Previous studies of lipoprotein oxidation showed that an increase in the lag accompanied by a decrease in Vmax indicate that an anti-oxidant binds Cu2+ and/or blocks the Cu2+ binding sites on lipoproteins, while a decrease in both Vmax and ODmax indicates nonradical decomposition of lipid peroxides [reviewed in (60)]. Our results (Fig. 4A, B) reveal that the addition of free SAA increases the lag phase in HDL and LDL and decreases the rate, Vmax, of the copper-induced lipid peroxidation in HDL, whereas fully lipidated SAA has little or no effect (Fig. 4D). These results imply that free SAA directly interferes with Cu2+ binding to HDL and LDL, either by binding Cu2+ or by blocking the Cu2+ binding sites on the lipoproteins, or both. In fact, free SAA was implicated to bind Cu2+ with ∼10 μM affinity (61); this binding is expected to be significant in oxidation studies such as ours, which use 10 μM Cu2+ (35). Such a direct interference of SAA with Cu2+ binding to lipoproteins is apparently one of the processes contributing to the observed anti-oxidant effect of SAA.

Additional processes that are not specific to a particular oxidant must also be involved. In fact, our results reveal that the anti-oxidant effect of SAA on lipoprotein lipids is not limited to copper, but extends to other oxidants such as MPO. This is evident from a significant delay in the MPO-induced oxidation of HDL containing 2:1 SAA:apoA-I, which was observed by dot blots for oxidized phospholipids (Fig. 5C). Because MPO is a major lipoprotein oxidant in vivo, the anti-oxidant effect of SAA observed in vitro is physiologically relevant.

What is the mechanistic explanation for the anti-oxidant effect of SAA on lipoproteins? SAA-induced decrease in both Vmax and ODmax of HDL (Fig. 4A, supplemental Fig. S1) suggests that, similar to free apoA-I (9), free SAA helps eliminate lipoprotein-associated lipid hydroperoxides. In fact, structural and binding studies showed that free SAA tetramer can bind a small lipophilic vitamin retinol and sequester it in the hydrophobic cavity (62) formed by the two amphipathic helices, h1 and h3, in SAA (26). This observation prompts us to hypothesize that oligomeric free SAA can sequester other small apolar molecules and their oxidation products in a similar manner, and thereby delay or block the propagation of lipid oxidation. Other mechanisms, such as SAA adhesion to the lipoprotein surface to screen it from the oxidative agents, might also be involved.

A hypothetical function of SAA as an anti-oxidant for lipids

On the basis of our in vitro studies, we postulate that the mild anti-oxidant effect of SAA may partially counterbalance the displacement of the anti-oxidant proteins from HDL during inflammation. Although SAA shows a weaker anti-oxidant effect than apoA-I on a milligram basis (Fig. 4B), this effect is strongly dose-dependent in the range of SAA:apoA-I molar ratios of 0:1 to 2:1 (Figs. 2, 3), which encompasses the plasma range under normal and inflammatory conditions (16, 17). Similarly, a dose-dependent anti-oxidant effect of SAA was observed in the physiologically relevant range of SAA to HDL ratios by Sato et al. (24), who used human HDL that was either enriched with human SAA or was obtained from serum of patients with high SAA levels. These observations suggest that the mild anti-oxidant effect of SAA is amplified by the dramatic upregulation of this acute-phase response protein. We propose that this anti-oxidant effect represents a novel beneficial function of SAA in acute injury or inflammation. This function may be important not only for delaying the oxidation of HDL and LDL lipids, but also for decelerating the pathogenic oxidation of phospholipids and cholesterol in damaged cell membranes. This idea is consistent with the concomitant upregulation of SAA and PLA2 within hours of acute-phase response (10, 11, 63). We speculate that PLA2 and SAA act in synergy in clearing cell debris: PLA2 hydrolyses phospholipids from the damaged cell membranes while SAA decelerates their toxic oxidation.

SAA-apoA-I heterodimer is a new HDL-bound species

Our second unexpected finding is the formation of a covalent SAA-apoA-I heterodimer upon enzymatic or nonenzymatic oxidation of SAA·HDL with chlorination. Because lipoprotein oxidation involving OCl−/Cl− is significant in vivo (48, 50), the SAA-apoA-I heterodimer is expected to form in vivo under pro-oxidant conditions in inflammation. In our in vitro study, such a heterodimer was detected by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting, and MALDI-TOF (Figs. 5A, B; 6) and was clearly attributed to the HDL-bound protein (Fig. 7). Notably, a recent study identified chemically cross-linked SAA and apoA-I on HDL obtained from mice with inflammation, suggesting close proximity between SAA and apoA-I on the HDL surface (64). Our results suggest that SAA and apoA-I molecules are in direct contact with each other on the HDL surface.

Although the full biological significance of the SAA-apoA-I heterodimer remains to be established, it is clear that SAA cross-linked to apoA-I is retained on HDL more strongly (Fig. 7) than the non-cross-linked monomeric SAA that binds HDL only transiently (30). Therefore, a small fraction of SAA that gets cross-linked upon oxidation in vivo is expected to have an unusually long residence time on HDL, which may significantly impact HDL metabolism.

Protein release from SAA·HDL upon mild oxidation: implications for amyloidosis

Our third unexpected finding is that the combined effects of SAA enrichment and oxidation promote the release of HDL proteins, including SAA and apoA-I. For example, copper-oxidized HDL shows spontaneous protein release under ambient conditions from SAA-enriched particles, but not native particles (Fig. 2C, D). Similarly, studies employing various perturbations that mimic HDL remodeling in vivo, including Gdn HCl, CETP, or incubation at 37°C, revealed that the combined effects of SAA enrichment and mild oxidation shift the population distribution from the HDL-bound to free proteins (Figs. 7, 8; supplemental Fig. S9). Mass spectrometry analysis suggests that this shift is associated with the Met(O) formation (supplemental Fig. S3). Enhanced apolipoprotein dissociation from the lipid surface upon Met oxidation was previously observed in other HDL proteins, apoA-I and apoA-II, and was attributed to the formation of polar Met(O) in the apolar lipid-binding faces of the amphipathic α-helices in these proteins, diminishing their affinity for lipid (46). SAA contains two conserved Met located in the apolar face of an amphipathic α-helix, h1 (residues 1-27), that is proposed to bind HDL (26). We hypothesize that oxidation of these Met contributes to the observed shift from HDL-bound to free SAA. Thus, Met oxidation enhances the release of a fraction of free monomeric SAA and apoA-I, while the cross-linked proteins are retained on the HDL surface (Fig. 7).

Importantly, the release of SAA from HDL is an obligatory early step in protein misfolding during inflammation-linked AA amyloidosis; similarly, apoA-I release from HDL is thought to be an obligatory early step in apoA-I amyloidosis [(65) and references therein]. In fact, in contrast to HDL-bound apolipoproteins, which are protected by the protein-lipid interactions, free apoA-I and, particularly, SAA form structurally labile metabolically active transient species that are susceptible to proteolytic degradation and misfolding [(65) and references therein]. Therefore, our results suggest that mild oxidation under pro-inflammatory conditions in vivo, which augments the release of SAA and apoA-I from HDL, may contribute to the pathogenesis of AA and apoA-I amyloidoses and may also accelerate the clearance of these oxidized proteins from circulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Dr. Kerry-Ann Rye (University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia) for her kind gift of purified CETP. They thank Nicholas M. Frame for reading the manuscript prior to publication.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- AA

- amyloid A

- CETP

- cholesterol ester transfer protein

- Gdn HCl

- guanidine hydrochloride

- Met(O)

- methionine sulfoxide

- mox·HDL

- HDL mildly oxidized by OCl−

- MPO

- myeloperoxidase

- nHDL

- nonmodified native HDL

- OD

- optical density

- ODmax

- maximal magnitude of copper-induced lipid peroxidation

- ox·HDL

- HDL extensively oxidized by Cu2+ after 100 min incubation

- PON1

- paraoxonase 1

- SAA

- serum amyloid A

- SAA-apoA-I

- covalent heterodimer of serum amyloid A and apoA-I

- SAA·HDL

- serum amyloid A-enriched HDL particles isolated from the total incubation mixture

- SAA·HDL(total)

- incubation mixture of HDL with serum amyloid A

- SEC

- size-exclusion chromatography

- Vmax

- maximal rate of copper-induced lipid peroxidation

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant GM067260 (O.G., S. J.) and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Foundation Grant HA 7138/2-1 (C.H.).

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lu M., and Gursky O.. 2013. Aggregation and fusion of low-density lipoproteins in vivo and in vitro. Biomol. Concepts. 4: 501–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parthasarathy S., Raghavamenon A., Garelnabi M. O., and Santanam N.. 2010. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Methods Mol. Biol. 610: 403–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sima A. V., Stancu C. S., and Simionescu M.. 2009. Vascular endothelium in atherosclerosis. Cell Tissue Res. 335: 191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assmann G., and Gotto A. M.. 2004. HDL cholesterol and protective factors in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 109(23, Suppl. 1) III8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barter P. J., Nicholls S., Rye K. A., Anantharamaiah G. M., Navab M., and Fogelman A. M.. 2004. Antiinflammatory properties of HDL. Circ. Res. 95: 764–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navab M., Hama S. Y., Cooke C. J., Anantharamaiah G. M., Chaddha M., Jin L., Subbanagounder G., Faull K. F., Reddy S. T., Miller N. E., et al. 2000. Normal high density lipoprotein inhibits three steps in the formation of mildly oxidized low density lipoprotein: step 1. J. Lipid Res. 41: 1481–1494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navab M., Hama S. Y., Anantharamaiah G. M., Hassan K., Hough G. P., Watson A. D., Reddy S. T., Sevanian A., Fonarow G. C., and Fogelman A. M.. 2000. Normal high density lipoprotein inhibits three steps in the formation of mildly oxidized low density lipoprotein: steps 2 and 3. J. Lipid Res. 41: 1495–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackness M. I., Arrol S., Abbott C., and Durrington P. N.. 1993. Protection of low-density lipoprotein against oxidative modification by high-density lipoprotein associated paraoxonase. Atherosclerosis. 104: 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayek T., Oiknine J., Dankner G., Brook J. G., and Aviram M.. 1995. HDL apolipoprotein A-I attenuates oxidative modification of low density lipoprotein: studies in transgenic mice. Eur. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 33: 721–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tietge U. J., Maugeais C., Lund-Katz S., Grass D., deBeer F. C., and Rader D. J.. 2002. Human secretory phospholipase A2 mediates decreased plasma levels of HDL cholesterol and apoA-I in response to inflammation in human apoA-I transgenic mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22: 1213–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navab M., Reddy S. T., Van Lenten B. J., Anantharamaiah G. M., and Fogelman A. M.. 2009. The role of dysfunctional HDL in atherosclerosis. J. Lipid Res. 50: S145–S149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ansell B. J., Fonarow G. C., and Fogelman A. M.. 2007. The paradox of dysfunctional high-density lipoprotein. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 18: 427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benditt E. P., and Eriksen N.. 1977. Amyloid protein SAA is associated with high density lipoprotein from human serum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 74: 4025–4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benditt E. P., Eriksen N., and Hanson R. H.. 1979. Amyloid protein SAA is an apoprotein of mouse plasma high density lipoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 76: 4092–4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabana V. G., Reardon C. A., Feng N., Neath S., Lukens J., and Getz G. S.. 2003. Serum paraoxonase: effect of the apolipoprotein composition of HDL and the acute phase response. J. Lipid Res. 44: 780–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malle E., Steinmetz A., and Raynes J. G.. 1993. Serum amyloid A (SAA): an acute phase protein and apolipoprotein. Atherosclerosis. 102: 131–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malle E., and De Beer F. C.. 1996. Human serum amyloid A (SAA) protein: a prominent acute-phase reactant for clinical practice. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 26: 427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Lenten B. J., Wagner A. C., Nayak D. P., Hama S., Navab M., and Fogelman A. M.. 2001. High-density lipoprotein loses its anti-inflammatory properties during acute influenza A infection. Circulation. 103: 2283–2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han C. Y., Tang C., Guevara M. E., Wei H., Wietecha T., Shao B., Subramanian S., Omer M., Wang S., O’Brien K. D., et al. 2016. Serum amyloid A impairs the antiinflammatory properties of HDL. J. Clin. Invest. 126: 266–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson J. C., Jayne C., Thompson J., Wilson P. G., Yoder M. H., Webb N., and Tannock L. R.. 2015. A brief elevation of serum amyloid A is sufficient to increase atherosclerosis. J. Lipid Res. 56: 286–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Röcken C., Menard R., Buhling F., Vockler S., Raynes J., Stix B., Kruger S., Roessner A., and Kahne T.. 2005. Proteolysis of serum amyloid A and AA amyloid proteins by cysteine proteases: cathepsin B generates AA amyloid proteins and cathepsin L may prevent their formation. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64: 808–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westermark G. T., Fändrich M., and Westermark P.. 2015. AA amyloidosis: pathogenesis and targeted therapy. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 10: 321–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kisilevsky R., and Manley P. N.. 2012. Acute-phase serum amyloid A: perspectives on its physiological and pathological roles. Amyloid. 19: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato M., Ohkawa R., Yoshimoto A., Yano K., Ichimura N., Nishimori M., Okubo S., Yatomi Y., and Tozuka M.. 2016. Effects of serum amyloid A on the structure and antioxidant ability of high-density lipoprotein. Biosci. Rep. 36: e00369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kollmer M., Meinhardt K., Haupt C., Liberta F., Wulff M., Linder J., Handl L., Heinrich L., Loos C., Schmidt M., et al. 2016. Electron tomography reveals the fibril structure and lipid interactions in amyloid deposits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 113: 5604–5609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frame N. M., and Gursky O.. 2016. Structure of serum amyloid A suggests a mechanism for selective lipoprotein binding and functions: SAA as a hub in macromolecular interaction networks. FEBS Lett. 590: 866–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnhold J., Weigel D., Richter O., Hammerschmidt S., Arnold K., and Krumbiegel M.. 1991. Modification of low density lipoproteins by sodium hypochlorite. Biomed. Biochim. Acta. 50: 967–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schumaker V. N., and Puppione D. L.. 1986. Sequential floatation ultracentrifugation. Methods Enzymol. 128: 155–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jayaraman S., Gantz D. L., and Gursky O.. 2005. Kinetic stabilization and fusion of apolipoprotein A-2:DMPC disks: comparison with apoA-1 and apoC-1. Biophys. J. 88: 2907–2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jayaraman S., Haupt C., and Gursky O.. 2015. Thermal transitions in serum amyloid A in solution and on the lipid: implications for structure and stability of acute-phase HDL. J. Lipid Res. 56: 1531–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abràmoff M. D., Magalhães P. J., and Ram S. J.. 2004. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International. 11: 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinchuk I., Schnitzer E., and Lichtenberg D.. 1998. Kinetic analysis of copper-induced peroxidation of LDL. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1389: 155–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hazell L. J., and Stocker R.. 1993. Oxidation of low-density lipoprotein with hypochlorite caused transformation of the lipoprotein into a high-uptake form for macrophages. Biochem. J. 290: 165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Exner M., Hermann M., Hofbauer R., Hartmann B., Kapiotis S., and Gmeiner B.. 2004. Thiocyanate catalyzes myeloperoxidase-initiated lipid oxidation in LDL. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 37: 146–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinchuk I., and Lichtenberg D.. 2002. The mechanism of action of antioxidants against lipoprotein peroxidation, evaluation based on kinetic experiments. Prog. Lipid Res. 41: 279–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gieseg S. P., and Esterbauer H.. 1994. Low density lipoprotein is saturable by pro-oxidant copper. FEBS Lett. 343: 188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jayaraman S., Gantz D. L., and Gursky O.. 2008. Effects of protein oxidation on the structure and stability of model discoidal high-density lipoproteins. Biochemistry. 47: 3875–3882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palinski W., Hörkkö S., Miller E., Steinbrecher U. P., Powell H. C., Curtiss L. K., and Witztum J. L.. 1996. Cloning of monoclonal autoantibodies to epitopes of oxidized lipoproteins from apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Demonstration of epitopes of oxidized low density lipoprotein in human plasma. J. Clin. Invest. 98: 800–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng L., Settle M., Brubaker G., Schmitt D., Hazen S. L., Smith J. D., and Kinter M.. 2005. Localization of nitration and chlorination sites on apolipoprotein A-I catalyzed by myeloperoxidase in human atheroma and associated oxidative impairment in ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux from macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mehta R., Gantz D. L., and Gursky O.. 2003. Human plasma high-density lipoproteins are stabilized by kinetic factors. J. Mol. Biol. 328: 183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rye K. A., Hime N. J., and Barter P. J.. 1997. Evidence that cholesteryl ester transfer protein-mediated reductions in reconstituted high density lipoprotein size involve particle fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 3953–3960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen S. D., Öörni K., Lee-Rueckert M., Pihlajamaa T., Metso J., Jauhiainen M., and Kovanen P. T.. 2012. Spontaneous remodeling of HDL particles at acidic pH enhances their capacity to induce cholesterol efflux from human macrophage foam cells. J. Lipid Res. 53: 2115–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao X., Jayaraman S., and Gursky O.. 2008. Mild oxidation promotes and advanced oxidation impairs remodeling of human high-density lipoprotein in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 376: 997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kagan V. E. 1988. Lipid Peroxidation in Biomembranes. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rye K. A., and Barter P. J.. 2004. Formation and metabolism of prebeta-migrating, lipid-poor apolipoprotein A-I. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24: 421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anantharamaiah G. M., Hughes T. A., Iqbal M., Gawish A., Neame P. J., Medley M. F., and Segrest J. P.. 1988. Effect of oxidation on the properties of apolipoproteins A-I and A-II. J. Lipid Res. 29: 309–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garner B., Waldeck A. R., Witting P. K., Rye K. A., and Stocker R.. 1998. Oxidation of high density lipoproteins. II. Evidence for direct reduction of lipid hydroperoxides by methionine residues of apolipoproteins AI and AII. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 6088–6095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bergt C., Pennathur S., Fu X., Byun J., O’Brien K., McDonald T. O., Singh P., Anantharamaiah G. M., Chait A., Brunzell J., et al. 2004. The myeloperoxidase product hypochlorous acid oxidizes HDL in the human artery wall and impairs ABCA1-dependent cholesterol transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101: 13032–13037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schultz J., and Kaminker K.. 1962. Myeloperoxidase of the leucocyte of normal human blood. I. Content and localization. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 96: 465–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DiDonato J. A., Aulak K., Huang Y., Wagner M., Gerstenecker G., Topbas C., Gogonea V., DiDonato A. J., Tang W. H., Mehl R. A., et al. 2014. Site-specific nitration of apolipoprotein A-I at tyrosine 166 is both abundant within human atherosclerotic plaque and dysfunctional. J. Biol. Chem. 289: 10276–10292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klebanoff S. J. 1967. A peroxidase mediated anti-microbial system in leukocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 46: 1078–1085. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kameda T., Usami Y., Shimada S., Haraguchi G., Matsuda K., Sugano M., Kurihara Y., Isobe M., and Tozuka M.. 2012. Determination of myeloperoxidase-induced apoAI-apoAII heterodimers in high-density lipoprotein. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 42: 384–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang W. Q., Merriam D. L., Moses A. S., and Francis G. A.. 1998. Enhanced cholesterol efflux by tyrosyl radical-oxidized high density lipoprotein is mediated by apolipoprotein AI-AII heterodimers. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 17391–17398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rye K. A., Hime N. J., and Barter P. J.. 1995. The influence of cholesteryl ester transfer protein on the composition, size, and structure of spherical, reconstituted high density lipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Öörni K., Rajamäki K., Nguyen S. D., Lähdesmäki K., Plihtari R., Lee-Rueckert M., and Kovanen P. T.. 2015. Acidification of the intimal fluid: the perfect storm for atherogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 56: 203–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aviram M., Rosenblat M., Bisgaier C. L., Newton R. S., Primo-Parmo S. L., and La Du B. N.. 1998. Paraoxonase inhibits high-density lipo-protein oxidation and preserves its functions. A possible peroxidative role for paraoxonase. J. Clin. Invest. 101: 1581–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watson A. D., Navab M., Hama S. Y., Sevanian A., Pres S. M., Stafforini D. M., McIntyre T. M., Du B. N., Fogelman A. M., and Berliner J. A.. 1995. Effect of platelet activating factor-acetylhydrolase on the formation and action of minimally oxidized-low density lipoprotein. J. Clin. Invest. 95: 774–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Forte T. M., Subbanagounder G., Berliner J. A., Blanche P. J., Clermont A. O., Jia Z., Oda M. N., Krauss R. M., and Bielicki J. K.. 2002. Altered activities of anti-atherogenic enzymes LCAT, paraoxonase, and platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase in atherosclerosis-susceptible mice. J. Lipid Res. 43: 477–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsunoda F., Lamon-Fava S., Horvath K. V., Schaefer E. J., and Asztalos B. F.. 2016. Comparing fluorescence-based cell-free assays for the assessment of antioxidative capacity of high-density lipoproteins. Lipids Health Dis. 15: 163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pinchuk I., Schnitzer E., and Lichtenberg D.. 1998. Kinetic analysis of copper-induced peroxidation of LDL. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1389: 155–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang L., and Colón W.. 2007. Effect of zinc, copper, and calcium on the structure and stability of serum amyloid A. Biochemistry. 46: 5562–5569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Derebe M. G., Zlatkov C. M., Gattu S., Ruhn K. A., Vaishnava S., Diehl G. E., MacMillan J. B., Williams N. S., and Hooper L. V.. 2014. Serum amyloid A is a retinol binding protein that transports retinol during bacterial infection. eLife. 3: e03206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vadas P., Browning J., Edelson J., and Pruzanski W.. 1993. Extracellular phospholipase A2 expression and inflammation: the relationship with associated disease states. J. Lipid Mediat. 8: 1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Digre A., Nan J., Frank M., and Li J. P.. 2016. Heparin interactions with apoA1 and SAA in inflammation-associated HDL. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 474: 309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Das M., and Gursky O.. 2015. Amyloid-forming properties of human apolipoproteins: sequence analyses and structural insights. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 855: 175–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.