Abstract

Background

The aim of the present study was to assess plantar pressure distribution and musculoskeletal symptoms following the use of customized insoles among female assembly line workers.

Methods

The study included 29 female assembly line workers (age, 29.76 ± 5.79 years; weight, 63.79 ± 12.11 kg) with musculoskeletal symptoms who work predominantly while standing. The Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire was administered to the study population. Plantar pressure was determined using a computerized plantar pressure feedback system. A control group (n=13) used ethylvinylacetate insoles (Podaly®) that were individually heat molded and heat glued. The intervention group (n=14) also used the insoles and a strip of the same material was added to the site of greatest plantar pressure as determined by the electronic feedback device. After five weeks, the plantar pressure data were collected again and the questionnaire was administered a second time.

Results

There was no significant difference between groups with regard to pain in any anatomic site. However, within each group the lumbar region exhibited a reduction in symptoms in the intervention group (P<0.05), and the feet exhibited a reduction in symptoms in both groups (P<0.05). Mean plantar pressure increased and plantar surface decreased in the intervention group (P<0.05).

Conclusion

Insoles increased foot comfort in both groups. However, the added strip did not significantly modify either plantar pressure or other symptoms in female workers.

Keywords: Worker health, Orthopedic devices, Foot

Plantar insoles are often used in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain and problems in the lower limbs.1,2 Specifically regarding the use of insoles, scientific findings report the prescription of this device for sports,3,4 for pain in the lumbar region and lower limbs,5–7 for alleviating plantar pressure,8–10 and for improving foot ulcers caused by diabetes.10,11

In the work environment, insoles are used as an ergonomic tool for reducing work-related symptoms especially in subjects who predominantly remain in a standing position.12,13 Standing for extended time periods affects venous blood flow, inter-vertebral stress, and weight-bearing joints, and thereby causes pain and discomfort as well as exacerbates musculoskeletal conditions.14,15 Despite the evident nature of the problem, there are few clinical trials addressing the use of and response to insoles in the work environment. Assessing the ergonomics of the issue is, therefore, important.

Few studies have examined the use of insoles in order to verify the reduction of complaints, without associating them with weight-bearing changes or other mechanical factors that may explain the change.13 Few studies have evaluated the effectiveness of this intervention in the workplace,12,13 and none have made comparisons between different insoles on the market in a work environment. In this sense, there are gaps in knowledge for interventions aimed at standing and static positions in symptomatic workers, in regard to plantar behavior and comparisons of insoles found on the market.

The present study is justified by factory worker complaints of pain, with possible harm to worker health, due to the biomechanical load from remaining in a standing position for extended periods of time. The aim of this study was to assess plantar pressure distribution and musculoskeletal symptoms following the use of customized insoles among female assembly line workers.

Methods

Sample and Study Design

The sample was made up of 40 female workers at an assembly line in the northeastern portion of the state of São Paulo, Brazil. All the women remain standing throughout their daily work shift, wearing the same shoes and cutting leather for the production of dog chew bones. Women over age 18 years with signs and symptoms of work-related musculoskeletal conditions in the lumbar region or lower limbs that developed while performing the current bone-production job were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included onset of symptoms prior to their work activities at the firm, systemic diseases, structural deformity or previous trauma (9 women); and transfer from the work sector (2 women). Thus, the final sample was made up of 29 female workers, with an average age of 29.76 ± 5.79 years and an average weight of 63.79 ± 12.11 kg. The choice of the female gender was based on epidemiological data that reveal women to be more affected by this type of injury.16

The study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee (process number n° 6032/2005) and authorization was obtained from the firm where the study was conducted. Participation of the individuals required reading, comprehension and signing an informed consent form. This study was registered in the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR) under number ACTRN12609000922279.

Data Collection and Questionnaire

Participants were assessed before and after the protocols with the use of insoles. The plantar pressure distribution (primary outcome) and musculoskeletal symptoms (secondary outcome) were assessed by means of an electronic plantar pressure plate (FootWork, AM3-IST, France) connected to a microcomputer (Pentium III) and responses to the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire, respectively.

The study was a double-blind randomized clinical trial. The participants included in the study were randomized into two groups by means of a lottery: the control group (CG) and intervention group (IG). An opaque, sealed envelope containing the groups studied was used for the randomization. The names “CONTROL” and “INTERVENTION” were used to ensure the confidentiality of the allocation of the participants. A researcher who was unaware of the objectives or purposes of the study, and who was not aware which group the particpants were in, carried out these procedures.

Data were collected at the work site during the first trimester of 2008, addressing questions on personal information such as age, weight, height, systemic disease, structural deformity and trauma prior to the analysis. The Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ) was used for the description of musculoskeletal complaints, employing the version validated for the Portuguese language.17 This model is used internationally and was developed in order to standardize studies on the subject. The NMQ is of easy comprehension and contains simple, direct questions.18 This questionnaire is based on multiple or binary choices regarding the occurrence of symptoms in different anatomical regions of the body over the last twelve months and in the last seven days, as well as withdrawal from their activities. Participants reported how often they felt the symptoms (pain, numbness, or discomfort) during the 12 months prior to completing the questionnaire.17 However, for data analysis, the scale was broken into two parts, namely, the presence or absence of musculoskeletal symptoms. Questions were added regarding the severity of the complaint for each anatomical region, on a scale of one to four, in which “one” represented no symptoms, while index “two” was attributed to a mild symptom, index “three” to a moderate symptom, and finally, index “four” to a severe symptom.16 The questionnaire was administered by the researcher during the work shift on two separate occasions: (1) prior to the intervention and (2) five weeks after arch support use. The interview format was adopted in order to avoid biases stemming from participants with different degrees of schooling, as suggested by Pastre et al.16

A digital scale was used to determine body weight (kg) and a metric tape attached to the wall was used to determine height (to an accuracy of 0.1 cm). Plantar pressure values were obtained using an electronic plantar pressure plate (FootWork, AM3-IST, France), connected to a microcomputer (Pentium III). The system has 2704 active surface sensors with a frequency of 150 Hz, and it emits a mathematical mean value of plantar pressure for each support as well as contact surface and maximal peak in kilogram-force/cm2, which was measured in both phases of the experiment (T1 and T2).

The volunteers remained in a standing position, with eyes looking straight ahead, arms alongside the body, base free of support within the delimited space on the pressure plate. The automatic calibration of the equipment considered the body weight of the individual, which is an important factor in establishing the validity of the pressure measurements. The recording of the test then began with the individual remaining on the pressure plate for ten seconds in bipodal support and barefoot. This procedure was repeated three consecutive times in each phase of the experiment (T1 and T2). All evaluations were performed in the morning following the work shift.

Description of Insoles

Ethylvinylacetate (EVA) insoles (Podaly® Palmilhas do Brasil) were used (Figure 1) in this study. All participants had plantar measurements taken in order to facilitate the design of the insoles. The insoles were then individually heat-glued and heat-molded and placed in a press (Termoprensa Ortopédica) at approximately 100°C. The insole was then inserted into a molder on which the individual stepped for 60 seconds, thereby giving shape to the insole, in compliance with the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Figure 1.

Insole Design

In the IG, an additional element consisting of a 2 mm strip of the same material was added to the site of greatest plantar pressure obtained from the plantar pressure analysis system.

Experiment

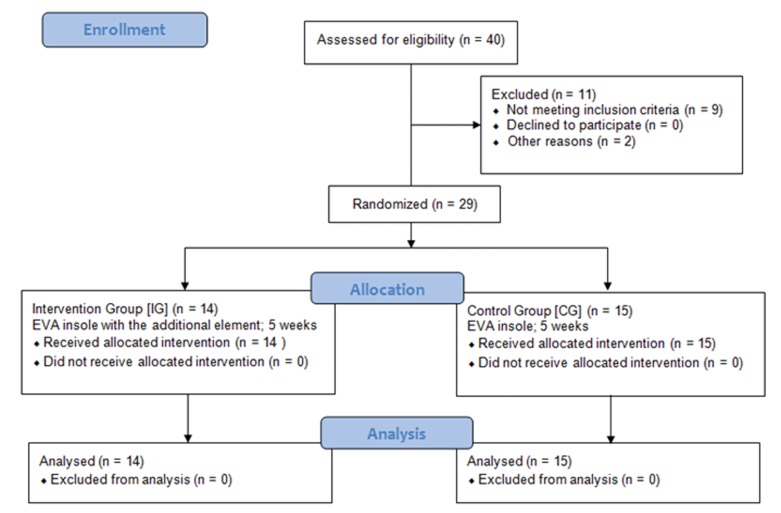

The participants were randomly divided into two groups. The CG (n=15) used the EVA insole and the IG (n=14) used the EVA insole with the additional element. The participants were instructed to use the insoles on a daily basis as part of their work clothing for a period of five weeks. Visits to the work site confirmed that the participants made use of the insoles during their labor activities throughout the 5-week period of the experiment. A total of 29 eligible subjects participated in this study. After randomization of the two groups no participants were excluded. Therefore, all 29 participants completed the trial and were included in subsequent analyses (Figure 2). The experiment was divided into two evaluation times: one prior to the intervention (T1) and another at the end of the 5-week period of insole use (T2). The NMQ and plantar pressure analysis system were administered on both occasions.

Figure 2.

Flow Chart of study based on CONSORT.

Data Analysis

The parameters used for the evaluation of the data for both feet were peak contact pressure, mean plantar pressure, and contact surface of the feet. Values for the properly positioned participant were recorded continuously. However, as described above, the equipment offers the mean values recorded during the evaluation. In order to establish localization limits within the anatomic structure, the option was made to use the mean of pressures as reference, which is indicated by the computational program, defining the anterior region as the forefoot and the posterior region as the hindfoot. From the plantar pressure values taken from the three 10-second collections, mean values were calculated for use in the data analysis. This procedure was adopted in order to correct possible interpretation biases related to the oscillation or disequilibrium of the volunteer throughout the test. This measure was adopted for all the variables at both evaluation times (prior to and following intervention). All data collected were entered in an electronic spreadsheet for the subsequent statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis involved descriptive measures of the anthropometric values using the Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney test for the comparison between groups. The Mann-Whitney test was used for the comparative study of variables related to anatomic site, pain intensity and evaluation time. Non-parametric analysis of variance for three-way ANOVA was used for the analysis of plantar pressure distribution in relation to the evaluation times. Goodman’s test was used to determine the association between groups, and pain in anatomic sites. The level of significance for all statistical tests was 5%.

Results

The anthropometric data of both groups showed that it is homogeneous (Table 1). There was no statistically significant association for any anatomic site between groups before or after intervention. However, within each group a reduction in pain levels occurred between the initial and final evaluation times (T1 and T2) for the feet in both groups (P<0.05) and for the lumbar region in the IG (P<0.05) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation of variables according to groups

| Groups | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Variable | Control ± SD (n=15) |

Intervention ± SD (n=14) |

| Age* | 31.93 ± 6.33 | 28.29 ± 5.17 |

| Weight (kg)† | 63.53 ± 11.96 | 64.07 ± 12.16 |

| Height (m)† | 1.59 ± 6.94 | 1.61 ± 3.79 |

| BMI (kg.m2)† | 25.39 ± 5.97 | 24.50 ± 5.08 |

Student’s t-test;

Mann-Whitney test

SD, standard deviation

Table 2.

Median, minimal and maximal values of pain level according to group and evaluation time (intervention group (n=14) and control group (n=15))

| Local | Group | Evaluation time

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | ||

| Lumbar region | Control | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 1.0 (1.0–4.0) |

| Intervention | 3.0 (1.0–4.0)* | 1.0 (1.0–3.0) | |

|

| |||

| Hip | Control | 1.0 (1.0–4.0) | 1.0 (1.0–4.0) |

| Intervention | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | |

|

| |||

| Knee | Control | 1.0 (1.0–4.0) | 1.0 (1.0–4.0) |

| Intervention | 1.0 (1.0–4.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | |

|

| |||

| Foot | Control | 4.0 (3.0–4.0)* | 3.0 (1.0–4.0) |

| Intervention | 4.0 (2.0–4.0)* | 1.0 (1.0–4.0) | |

Statistically significant difference between the times (P<0.05); Mann-Whitney test

Regarding the distribution of plantar pressure at the different evaluation times, there was a reduction in contact surface for both feet in both groups (Table 3). However, there was a significant difference for the IG as well as for the right foot in the CG (P<0.05). There was a significant difference in the IG regarding mean plantar pressure distribution (P<0.05). In the lumbar region, knee, and feet, an improvement in symptoms occurred in both groups when comparing evaluation times prior to and following the intervention (P<0.05) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Mean, standard deviation and 95% confidence interval of variables according to plantar pressure distribution and evaluation time (intervention group (n=14) and control group (n=15))

| Variable | Group | Foot | Evaluation time

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before ± SD [95% CI] |

After ± SD [95% CI] |

|||

| Mean of foot | Control | R | 0.320 ± 0.036 | 0.329 ± 0.040 |

| [0.308 – 0.334] | [0.316 – 0.340] | |||

| Intervention | R | 0.304 ± 0.030 | 0.340 ± 0.034# | |

| [0.294 – 0.313] | [0.329 – 0.351] | |||

|

| ||||

| Control | L | 0.354 ± 0.049* | 0.353 ± 0.038 | |

| [0.338 – 0.368] | [0.341 – 0.365] | |||

| Intervention | L | 0.331 ± 0.034* | 0.359 ± 0.038# | |

| [0.321 – 0.342] | [0.346 – 0.370] | |||

|

| ||||

| Peak of foot | Control | R | 0.855 ± 0.086 | 0.873 ± 0.116 |

| [0.828 – 0.880] | [0.838 – 0.908] | |||

| Intervention | R | 0.852 ± 0.111 | 0.875 ± 0.115 | |

| [0.817 – 0.887] | [0.838 – 0.910] | |||

|

| ||||

| Control | L | 0.876 ± 0.090 | 0.893 ± 0.077 | |

| [0.848 – 0.902] | [0.869 – 0.915] | |||

| Intervention | L | 0.891 ± 0.098 | 0.890 ± 0.099 | |

| [0.860 – 0.921] | [0.858 – 0.920] | |||

|

| ||||

| Plantar surface | Control | R | 174.667 ± 26.765# | 162.311 ± 26.576 |

| [166.62 – 182.71] | [154.32 – 170.30] | |||

| Intervention | R | 179.546 ± 28.832# | 161.071 ± 31.081 | |

| [170.56 – 188.53] | [151.38 – 170.76] | |||

|

| ||||

| Control | L | 181.623 ± 28.181 | 176.600 ± 25.264 | |

| [173.15 – 190.09] | [169.00 – 184.20] | |||

| Intervention | L | 181.643 ± 27.015# | 171.548 ± 30.202 | |

| [173.22 – 190.06] | [162.13 – 180.96] | |||

Significant difference (P<0.05) in comparison between feet (R vs L) in the same group and time

Significant difference (P<0.05) in comparison between time (before vs after) in the same group and foot

Non-parametric analysis of variance for three way ANOVA

SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval

Table 4.

Distribution of occurrence of pain according to group and evaluation time (intervention group (n=14) and control group (n=15)).

| Local | Group | Before evaluation

|

After evaluation

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absence of pain | Presence of pain | Absence of pain | Presence of pain | ||

| Lumbar region | Control | 4 (26.67%) | 11 (73.33%) | 8 (53.33%) | 7 (46.67%) |

| Intervention | 2 (14.29%) | 12 (85.71%) | 9 (64.29%) | 5 (35.71%) | |

|

| |||||

| Hip | Control | 11 (73.33%) | 4 (26.67%) | 11 (73.33%) | 4 (26.67%) |

| Intervention | 13 (92.86%) | 1 (7.14%) | 13 (92.86%) | 1 (7.14%) | |

|

| |||||

| Knee | Control | 10 (66.67%) | 5 (33.33%) | 11 (73.33%) | 4 (26.67%) |

| Intervention | 8 (57.14%) | 6 (42.86%) | 13 (92.86%) | 1 (7.14%) | |

|

| |||||

| Foot | Control | 0 (0.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 4 (26.67%) | 11 (73.33%) |

| Intervention | 0 (0.0%) | 14 (100.0%) | 8 (57.14%) | 6 (42.86%) | |

Goodman’s test

Discussion

The choice of the sample population in the present study should first be discussed. According to Walsh et al19 and Reis et al,20 women between ages 20 and 39 years are affected by a greater frequency of musculoskeletal disorders. Andersen et al,21 Orlando et al,22 King,23 and Messing et al24 point out that the use of the standing position in the workplace has a significant impact on worker health, productivity, and absenteeism. Thus, based on these issues related to gender, age, and work, the sample selected for the present study offered excellent control conditions for the investigation.

The results of plantar pressure distribution in the present clinical trial revealed a reduction in contact surface in both groups. An increase in mean plantar pressure in the IG was also observed demonstrating that the inclusion of the additional element to the insoles did not have an effect on improving plantar pressure distribution. These findings corroborate those described by Raspovic et al,11 who found no positive effects of the use of insoles with the placement of strips on areas of ulceration in patients with diabetes. Our findings are also in agreement with Pawelka et al25 who found no improvement in plantar pressure distribution using insoles with no additional elements. However, the findings of the present study are in disagreement with those described by Guldemond et al,9 Tsung et al,10 and Kelly et al26 who demonstrated that the use of insoles without additional elements were able to reduce plantar pressure in diverse populations, especially in the forefoot. However, these studies did not make comparisons between insoles with and without additional strips. In addition, customization of the insoles, inclusion of added elements, material type and thickness of insoles and other factors influencing absoption of shock were not the same in all studies.9,27 Therefore, any baropodometric data should be interpreted with caution, as suggested by Oliveira et al.28

It should be stressed that there was no standardization in the aforementioned studies regarding the customization of the insoles, the inclusion of additional elements in the insoles or the type and thickness of the material employed, which are factors that influence shock absorption. This hinders the comparison of results, as pointed out by Chiu et al27 and Guldemond et al.9

In the present study, a positive response, in relation to the distribution of plantar pressure, was expected; however, such effects were not observed. One of the hypotheses that could be raised regarding this finding concerns the specificity of the intervention. The participants used the insoles in a particular position and in a repetitive activity. However, the initial and final evaluations were preformed with a predefined protocol in a static, standing position, without the characteristic movements performed by the workers in the work environment. Thus, the expected adaptation processes may not have been identified by the proposed analysis, as the stimuli were given in a situation completely different from the initial and final analyses. Future studies should evaluate the effect of insoles in the work setting specific to a particular function taking into account the kinematic and kinetic characteristics of the motor actions employed by the workers. Such considerations reinforce the need for caution in analyzing plantar pressure data, as suggested by Oliveira et al.28

With regard to the symptoms, the use of both types of insoles led to a reduction in pain levels. This result is similar to that described by Sobel et al12 who found an improvement in musculoskeletal discomfort among police officers. It should be pointed out, however, that the authors used elastomer insoles with the inclusion of various additional elements placed at different plantar pressure sites for five weeks. Although the intervention period was the same, the material was different and there was no comparison to a CG or standardization with regard to the placement of the additional elements. Another study used polyethylene viscoelastic insoles with no additional elements and found an improvement in symptoms after five weeks of use among workers who remained standing 75% of the time, which corroborates our results.13

The feet had the greatest frequency of improved symptoms following insole use in both groups. This finding may be explained by the fact that the participants received a supportive structure for the feet, which minimized the transmission of force due to the hard surface on which the workers are stationed to perform their work.

There was also an improvement in pain for the lumbar region, but only in the IG. A possible explanation would be directed toward biomechanical aspects. However, the findings of the present study do not support this statement, as there was no improvement in the distribution of plantar pressure. Furthermore, despite the improvement in foot symptoms, which one may expect to be reflected in an ascending fashion to the back, this finding was observed in both groups, which also limits this line of reasoning. Thus, excluding chance, the initial evaluation method and specificity of the prescription of the insoles merit special attention in future studies.

In a generic, but supported analysis, it was determined that the use of insoles causes a sensation of comfort,13,29 which is a fundamental aspect to the success of the prescription. This, in turn, causes a subjective sensation of improvement in symptoms triggered by the standing position. In an obvious conclusion, but pertinent to this discussion, the literature suggests that standing on a soft surface is less fatiguing and more comfortable than standing on a hard surface.23 The results of the present study reveal that, although pressure levels were negative, benefits were demonstrated in terms of symptoms. Thus, it is undeniable that the condition of greater comfort is a positive factor in relation to a reduction in symptoms of less clinical importance.

This study is limited by a lack of comparativeness with previously published investigations. Although the method adopted in this trial was adequate, there was an absence of standardization in the data collection, and greater specificity from the standpoint of the clinical intervention as well as the data collection and recording is needed to improve comparability between studies. Furthermore, the need for an individualized insole prescription should be addressed, considering foot type, ankle mobility, insole material and thickness, and standardization in the placement of additional elements. Attention to these aspects could provide different results from those encountered in the present study, and thus, facilitate the discussion of the results.

We believe that strategic actions that unite health and work should be encouraged to establish therapeutic proposals, such as the individualized prescription of insoles which are designed to provide greater comfort, reduce physical load, and musculoskeletal symptoms imposed on the bodily structures of workers. Such actions can have a positive impact on worker health, in addition to improvements in social life.

Conclusion

Insoles increased the feet comfort in both groups and added strip did not either significantly modify the plantar pressure or other musculoskeletal symptoms in female workers.

References

- 1.Collins N, Bisset L, McPoil T, Vicenzino B. Foot orthoses in lower limb overuse conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Foot Ankle Int 2007;28(3):396–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vicenzino B. Foot orthotics in the treatment of lower limb conditions: a musculoskeletal physiotherapy perspective. Man Ther 2004;9(4):185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Withnall RD, Eastaugh J, Freemantle N. Do shock absorbing insoles reduce lower limb injury? A randomized trial in british military subjects: 1825. 3:15 PM – 3:30 PM [abstract]. [Google Scholar]; Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37(5)(Supplement):S346. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baur H, Hirschmueller A, Mueller S, Gollhofer A, Dickhuth HH, Mayer F. Therapeutic efficiency of insoles in runners: 1141boards [abstract]. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37(Supplement):S214–S215. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sahar T, Cohen MJ, Ne’eman V, et al. Insoles for prevention and treatment of back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;4(4):CD005275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jannink M, van Dijk H, Ijzerman M, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K, Groothoff J, Lankhurst G. Effectiveness of custom-made orthopaedic shoes in the reduction of foot pain and pressure in patients with degenerative disorders of the foot. Foot Ankle Int 2006;27(11):974–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodge MC, Bach TM, Carter GM. Orthotic management of plantar pressure and pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1999;14(8):567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goske S, Erdemir A, Petre M, Budhabhatti S, Cavanagh PR. Reduction of plantar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guldemond N, Leffers P, Schaper N, Sanders A, Nieman F, Walenkamp G. Comparison of foot orthoses made by podiatrists, pedorthists and orthotists regarding plantar pressure reduction in The Netherlands. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2005;6(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsung BYS, Zhang M, Mak AFT, Wong MWN. Effectiveness of insoles on plantar pressure redistribution. J Rehabil Res Dev 2004;41(6)(6A):767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raspovic A, Newcombe L, Lloyd J, Dalton E. Effect of customized insoles on vertical plantar pressures in sites of previous neuropathic ulceration in the diabetic foot. Foot 2000;10(3):133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sobel E, Levitz SJ, Caselli MA, Christos PJ, Rosenblum J. The effect of customized insoles on the reduction of postwork discomfort. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2001;91(10):515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basford JR, Smith MA. Shoe insoles in the workplace. Orthopedics 1988;11(2):285–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Messing K, Tissot F, Stock S. Distal lower-extremity pain and work postures in the Quebec population. Am J Public Health 2008;98(4):705–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melzer ACS. Physical and organizational risk factors associated to work-related musculoskeletal disorders in textile industry. Fisioterapia e Pesquisa 2008;15(1):19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pastre EC, Carvalho Filho G, Pastre CM, Padovani CR, Almeida JS, Netto Júnior J. Queixas osteomusculares relacionadas ao trabalho relatadas por mulheres de centro de ressocialização. Cad Saude Publica 2007;23(11):2597–2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinheiro FA, Tróccoli BT, Carvalho CV. Validação do Questionário Nórdico de Sintomas Osteomusculares como medida de morbidade. Rev Saude Publica 2002;36(3):307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Barros ENC, Alexandre NMC. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire. Int Nurs Rev 2003;50(2):101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh IAP, Corral S, Franco RN, Canetti EEF, Alem MER, Coury HJCG. [Work ability of subjects with chronic musculoskeletal disorders]. Rev Saude Publica 2004;38(2):149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; heel pressures: Insole design using finite element analysis. J Biomech 2006;39(13):2363–2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reis RJ, Pinheiro TMM, Navarro A, Martin MM. Perfil da demanda atendida em ambulatório de doenças profissionais e a presença de lesões por esforços repetitivos. Rev Saude Publica 2000;34(3):292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen JH, Haahr JP, Frost P. Risk factors for more severe regional musculoskeletal symptoms: A two-year prospective study of a general working population. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56(4):1355–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orlando AR, King PM. Relationship of demographic variables on perception of fatigue and discomfort following prolonged standing under various flooring conditions. J Occup Rehabil 2004;14(1):63–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King PM. A comparison of the effects of floor mats and shoe in-soles on standing fatigue. Appl Ergon 2002;33(5):477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Messing K, Kilbom Å. Standing and very slow walking: foot pain-pressure threshold, subjective pain experience and work activity. Appl Ergon 2001;32(1):81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawelka S, Kopf A, Zwick EB, Bhm T, Kranzl A. Comparison of two insole materials using subjective parameters and pedobarography (pedar-system). Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1997;12(3):S6–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly A, Winson I. Use of ready-made insoles in the treatment of lesser metatarsalgia: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Foot Ankle Int 1998;19(4):217–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiu MC, Wang MJJ. Professional footwear evaluation for clinical nurses. Appl Ergon 2007;38(2):133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Oliveira GS, Greve JMDA, Imamura M, Bolliger Neto R. Interpretação das variáveis quantitativas da baropodometria computadorizada em indivíduos normais. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo 1998;53(1):16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shabat S, Gefen T, Nyska M, Folman Y, Gepstein R. The effect of insoles on the incidence and severity of low back pain among workers whose job involves long-distance walking. Eur Spine J 2005;14(6):546–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]