Abstract

Background

Outpatient management is safe and effective in preventing early recurrent stroke after TIA, but this approach may not be safe in patients with acute minor stroke.

Methods

We studied outcomes of clinic and hospital-referred patients with TIA or minor stroke (NIHSS≤3) in a prospective, population-based study (Oxford Vascular Study).

Results

Of 845 patients with TIA/stroke, 587 (67%) were referred directly to outpatient clinics and 258 (30%) directly to inpatient services. Of the 250 clinic-referred minor strokes (mean age=72.7 years), 237 (95%) were investigated, treated and discharged on the same day, of whom 16 (6.8%) were subsequently admitted to hospital within 30 days for recurrent stroke (n=6), sepsis (n=3), falls (n=3), bleeding (n=2), angina (n=1), and nursing care (n=1). The 150 patients (mean age=74.8 years) with minor stroke referred directly to hospital (median length-of-stay=9 days) had a similar 30-day-readmission rate (9/150;6.3%;p=0.83) after initial discharge and a similar 30-day risk of recurrent stroke (9/237 in clinic patients vs 8/150, OR=0.70,0.27-1.80,p=0.61). Rates of prescription of secondary prevention medication after initial clinic/hospital discharge were higher in clinic versus hospital-referred patients for antiplatelets/anticoagulants (p<0.05) and lipid lowering (p<0.001) and were maintained at one-year follow-up. The mean (SD) secondary care cost was £8323 (13,133) for hospital-referred minor stroke versus £743 (1794) for clinic-referred cases.

Conclusion

Outpatient management of clinic-referred minor stroke is feasible and may be as safe as inpatient care. Rates of early hospital admission and recurrent stroke were low and uptake and maintenance of secondary prevention was high.

Keywords: minor stroke, transient ischaemic attack, outpatient clinic

Introduction

Patients with TIA and minor stroke may be investigated and treated in the inpatient or outpatient clinic setting.1,2 Since patients differ in terms of risk factors, co-morbidities, type of event and other demographic and clinical characteristics, it is important to select the most appropriate setting for the management of each patient in order to improve prognosis and limit costs. Secondary prevention delivered via rapid access outpatient clinics has been shown to be effective in patients with TIA, significantly reducing the risk of early recurrent stroke,3,4 and is recommended in clinical guidelines.5–13 However, for patients with minor stroke, whether outpatient secondary care is similarly safe is less clear. Prompt specialist assessment is recommended for those with non-disabling stroke at high early risk of recurrence but most guidelines do not specify in which setting this should be delivered,6–11 some suggest admitting all with minor stroke to hospital,6,12,14 and others suggest that outpatient assessment is an option.5,13 Since a randomized trial of treatment setting would not be feasible, we aimed to assess the clinical outcomes, early hospital admission rates, and hospital care costs in clinic-referred and hospital-referred minor stroke patients in a prospective, population based study of all incident and recurrent TIA and stroke in Oxfordshire, UK (Oxford Vascular Study).

Methods

The Oxford Vascular Study (OXVASC) is a prospective, population based study of all stroke and TIA in 91,105 individuals of all ages registered with 63 general practitioners in Oxfordshire, UK. OXVASC is approved by our local ethics committee. The study methods have been described elsewhere.15,16 Briefly, multiple overlapping methods of “hot” and “cold” pursuit were used to achieve near complete ascertainment of all individuals presenting to medical attention with TIA or stroke.15,16 These include:

-

1)

1) A daily (weekdays only), urgent open-access “TIA clinic” to which participating general practitioners (GPs) and the local accident and emergency department (A&E) send all individuals with suspected TIA or stroke whom they would not normally admit to hospital, with alternative on-call review provision at weekends.

-

2)

Daily searches of admissions to the medical, stroke, neurology and other relevant wards.

-

3)

Daily searches of the local A&E attendance register.

-

4)

Monthly computerized searches of GP diagnostic coding and hospital discharge codes.

-

5)

Monthly searches of all cranial and carotid imaging studies performed in local hospitals.

-

6)

Monthly reviews of all death certificates and coroners reports.

All patients were consented and seen by study physicians as soon as possible after their initial presentation. Baseline characteristics and time of first seeking medical attention were recorded in all patients. Assessments were made for severity of event using the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)17 and clinical features. Events were classified as minor stroke if there was a focal neurological deficit lasting more than 24 hours and an NIHSS score ≤3 at time of assessment by a study physician. Brain imaging (usually CT) and 12-lead ECG were obtained on the same day or shortly thereafter. Carotid ultrasound imaging (all patients) and trans-thoracic or trans-oesophageal echocardiography (when clinically indicated) were arranged during the following week. Patients with swallowing difficulties or physiotherapy needs were referred for assessments when clinically indicated. The treatment protocol for clinic patients has been described previously.4 All cases were subsequently reviewed by the study senior neurologist (PMR) and classified as TIA, stroke or other condition using standard definitions.15 Aetiological classification of events was performed according to the TOAST classification once investigations were complete.18 This paper includes all cases with events from the 1st April 2002 to 31st March 2007. The cases identified during the study period included a small number of patients who were ascertained later but were not included in previous publications.4 Nested within OXVASC, the Early use of Existing Preventive Strategies for Stroke (EXPRESS) study evaluated the introduction of early assessment and treatment of patients in the daily TIA and minor stroke clinic.4 The EXPRESS study intervention involved more urgent assessment and immediate treatment in clinic from 1st October 2004- March 31st 2007.4 Prior to this, treatment was initiated in primary care after clinic assessment.

All patients were followed up face-to-face at 1 month, 6 months, 1 year and 5 years by a study nurse or physician. Recurrent symptoms, medications and any episodes requiring hospitalisation were recorded with reason for admission and length of hospital stay. All recurrent events requiring hospital admission would also be identified acutely by ongoing daily case-ascertainment within OXVASC. All patients with recurrent events were reassessed by a study physician and reviewed by PMR.

Analysis

We restricted analysis to patients with first TIA or stroke in the study period (index event) referred to secondary care. Cases presenting to non-OXVASC clinics (such as neurology or the eye hospital) were included as clinic treated cases. Those who had their event whilst out of the study area and were ascertained late after the event were excluded. Secondary prevention measures started after the index event were analysed, including prescription of anti-platelet, anticoagulant, lipid lowering and blood-pressure lowering medications and referral for carotid endarterectomy. As a measure of safety of the out-patient clinic, we analysed the risk of recurrent stroke and all hospitalisations up to 30 days after clinic assessment with reasons for admission including admission for recurrent stroke. Patients admitted directly from clinic due to worsening symptoms, recurrent stroke or need for nursing care were analysed as clinic-referred cases since this was an appropriate use of the clinic. Patients who were admitted with a recurrent stroke before their clinic appointment were included as clinic-referred patients for the analysis. For those treated in hospital, readmission rates up to 30 days after discharge, reasons for re-admission and recurrent stroke rates were also analysed.

All admissions to hospital, day case assessments, and lengths of stay were recorded. Unit costs were obtained from national reference costs and calculated for each day spent in each specialty ward and each outpatient clinic appointment. Costs were standardised to 2008–09 prices by use of the UK National Health Service hospital and community health services inflation index to calculate the 30 day hospital care cost per patient. Costs were adjusted for characteristics different at baseline. The daily TIA clinic cost was derived from UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines on stroke and TIA management.6 A regression analysis, with robust standard errors, was performed to assess whether being visited in clinic was an independent predictor of reduced 30-day hospital care costs. Included as predictors were NIHSS score, history of AF, days to medical attention, and whether the patient was living alone. Due to the skewness in cost data, costs were logarithmically transformed. Predicted costs obtained from the regression were then retransformed using Duan’s smearing estimator.

Results

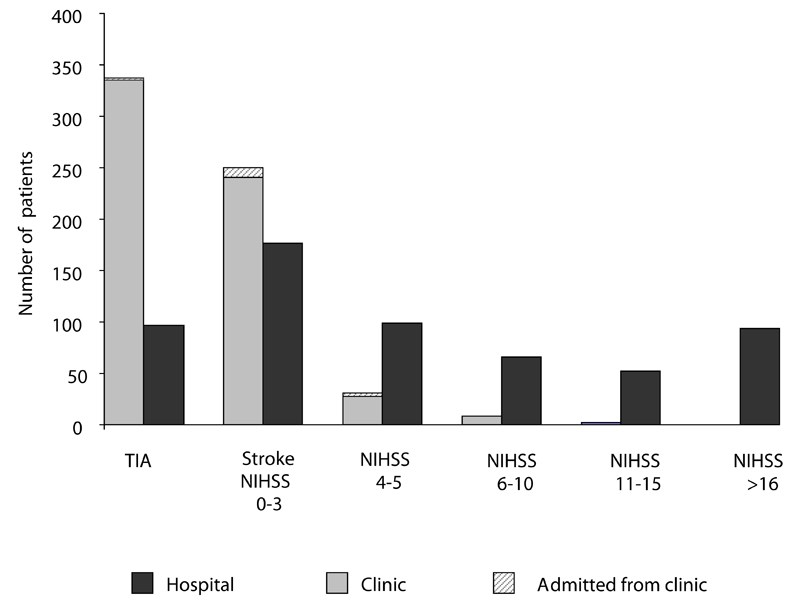

Of 1293 patients with TIA and stroke who sought medical attention, 1213 (94%) were referred to secondary care. Of these, 434 patients had TIA, 411 had minor stroke (15 with primary intracerebral haemorrhage (PICH)), 326 had major stroke (46 PICH) and 42 had subarachnoid haemorrhage. Amongst patients with minor stroke, 61% (250) were referred to the outpatient clinic (including 14 to non-OXVASC clinics such as neurology or ophthalmology) and 39% (161) were referred directly or self-presented to hospital, of which 54/161 (33.5%) received stroke unit care. The outpatient clinic also treated 78% of patients with TIA (337) and 13% (41) of patients with major stroke (NIHSS >3) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of patients referred to secondary care by event type, severity and treatment provision setting, n=1213 (excludes 31 cases who had their event on holiday)

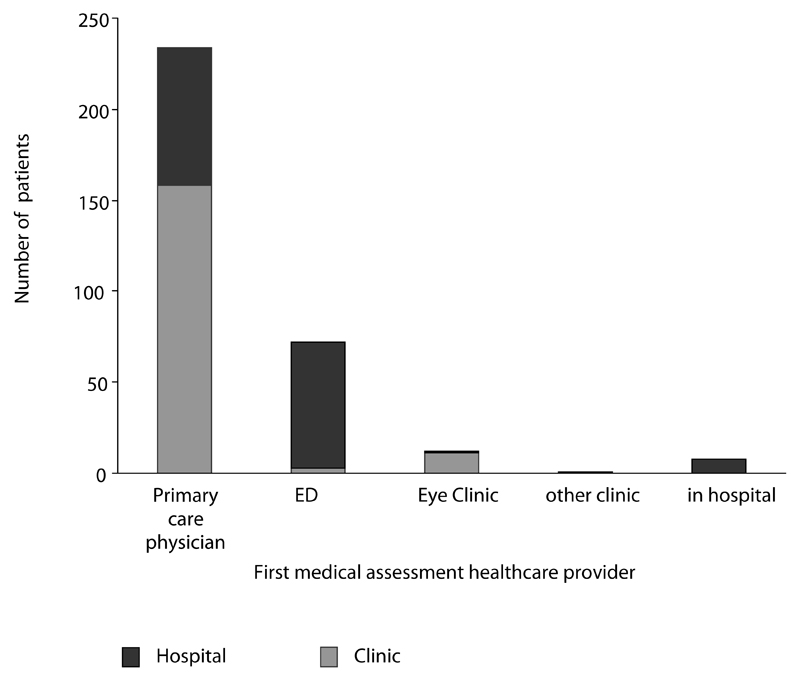

Of those with minor stroke, 80% (327) sought medical attention within 24-hours of symptom onset. Of these, 72% (234) presented to their primary care physician and 22% (72) presented to the hospital emergency department (ED) (Figure 2). Of those seeking medical attention within 24-hours from the primary care physician, 68% (158) were referred to clinic and 32% (76) were referred to hospital. Premorbid mRS>2 and subsequent diagnosis of PICH were associated with hospital referral (p=0.005 and p=0.04 respectively). The median time from seeking medical attention in primary care to clinic attendance was 2 days (IQR 1-5), although this was reduced to 1 day (IQR 0-4) post-EXPRESS and 41 (16.4%) of patients were seen on the same day.

Figure 2.

First medical assessment provider of patients with minor stroke seeking medical attention within 24 hours and referred to secondary care, n=327

Of 250 clinic referred patients with minor stroke, 2 with minor ischaemic stroke (MIS) were admitted with a recurrent stroke before their appointment, both of whom were pre-EXPRESS. In addition, 1 patient with MIS was an in-patient at the time of clinic referral and 10 patients (6 MIS, 4 PICH) were admitted directly from the clinic for further investigation or nursing care. Those with minor stroke seen in the clinic were less likely to live alone (28% vs 38.5%, p=0.03), less likely to have prior AF (13.2% vs 23.6%, p=0.008), less likely to present at the weekend (12.8% vs 29.2%, p<0.001), and had less severe events (median NIHSS 1 (IQR 0-2) vs NIHSS 2 (0-3, p<0.001) (Table 1). There was a higher proportion with cardioembolic aetiology amongst in-patients with MIS (26% vs 13% in clinic cases, p=0.002). Undetermined and unknown aetiology were more common amongst clinic patients (p<0.01). The proportions of cases with large artery disease were similar in both treatment settings (10% vs 6.7%, p=0.28).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with minor stroke (NIHSS≤3) by treatment setting, n=411*.

| Stroke clinic, n=250 (%) | Acute hospital, n=161 (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean (SD)) | 72.7 (12.1) | 74.8 (12.2) | 0.08 |

| Male | 122 (48.8) | 101 (62.7) | 0.06 |

| Living alone | 70 (28.0) | 62 (38.5) | 0.03 |

| Hypertension | 149 (59.6) | 96 (59.6) | 1.0 |

| Diabetes | 27 (10.8) | 18 (11.2) | 1.0 |

| Current smoking | 39 (15.6) | 22 (13.7) | 0.67 |

| Prior angina or myocardial infarction | 45 (18.0) | 41 (25.5) | 0.08 |

| Prior stroke | 42 (16.8) | 20 (12.4) | 0.26 |

| Prior TIA | 30 (12.0) | 11 (6.8) | 0.09 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 20 (8.0) | 14 (8.7) | 0.86 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 33 (13.2) | 38 (23.6) | 0.008 |

| Prior antiplatelet | 101 (40.4) | 78 (48.4) | 0.13 |

| Prior statin | 51 (20.4) | 32 (19.9) | 1.0 |

| Prior anti-hypertensive | 147 (58.8) | 93 (57.8) | 0.84 |

| Premorbid mRS≥2 | 75 (30.2) | 60 (37.3) | 0.13 |

| Days to seeking medical attention, median (IQR) | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-0) | <0.001 |

| Presented at the weekend | 32 (12.8) | 47 (29.2) | <0.001 |

| NIHSS, median (IQR) | 1 (0-2) | 2 (0-3) | <0.001 |

| TOAST subtype (MIS, n=396) | |||

| Cardioembolic | 33 (13.4) | 39 (26.0) | 0.002 |

| Large artery | 25 (10.2) | 10 (6.7) | 0.28 |

| Small vessel | 66 (26.8) | 30 (20.0) | 0.15 |

| Undetermined | 97 (39.4) | 35 (23.3) | 0.001 |

| Unknown | 14 (5.7) | 27 (18.0) | <0.001 |

| Multiple | 4 (1.6) | 3 (2.0) | 1.0 |

| Other | 7 (2.8) | 6 (4.0) | 0.57 |

includes 15 PICH, 4 clinic-referred, 11 hospital-referred

Of 237 patients with MIS discharged from clinic, 6.8% (16) required non-elective admission within 30 days (8 within 7 days). There was no difference in the 30-day admission rate in patients seen in the clinic compared with the 30-day readmission rate after discharge in hospital treated patients (16/237 vs 9/150, p=0.83, Table 2). Most of those with MIS requiring readmission within 30 days from both treatment settings were those who presented within 24-hours of symptom onset, 88% (22/25). The 30-day recurrent stroke risk in patients with MIS was also similar between those discharged from clinic compared with those seen in hospital (3.8% (9/237) vs 5.3% (8/150), OR 0.70, 0.27-1.80, p=0.61). However, the 30-day recurrent stroke risk after MIS discharged from the clinic was higher than in those discharged after TIA (3.8% (9/237) vs1.2% (4/326), OR 3.18, 1.02-9.84, p=0.05). All results were similar when patients presenting at the weekend were excluded

Table 2.

Reasons for non-elective admission in patients with TIA and minor ischaemic stroke up to 7 and 30 days after discharge from treatment provision setting, n=810*

| Stroke clinic, n=563 | Acute hospital, n=247 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIA, n=326 | MIS, n=237 | TIA, n=97 | MIS, n=150 | |||||

| <7 days | 8-30 days | <7 days | 8-30 days | <7 days | 8-30 days | <7 days | 8-30 days | |

| Recurrent stroke | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1 PICH, 1 ischaemic stroke) |

| Recurrent TIA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rehabilitation | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Sepsis | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Fall | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bleeding | 0 | 2 (GI bleed) | 0 | 2 (1GI, 1GU bleed) | 0 | 2 (GI bleed) | 0 | 1(GI bleed) |

| Other | 1 (angina) | 1 (giant cell arteritis) | 1 (angina) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (urinary retention, colitis, pulmonary oedema) |

| Total | 8 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

13 deaths at 30 days: 3 clinic referred (1TIA, 2 MIS), 10 hospital cases (3 TIA, 7 MIS).

Of 161 patients with minor stroke seen in hospital, 96% sought medical attention within 24 hours compared with 69% of clinic referred patients (154/161 vs 173/250, p<0.001). The median length of hospital stay for in-patients with minor stroke presenting in 24 hours was 8 days (IQR 3-32) and for all patients was 9 (3-33) days.

In those presenting within 24 hours, the 30-day recurrent stroke risks after MIS in clinic and hospital referred patients were similar (5.2%, 9/172 vs 4.1% 6/145, OR 1.27, 0.46-3.54, p=0.79). The 30-day readmission rates were also similar (8.1%, 14/172 vs 5.5% 8/145, OR 1.5, 0.63-3.6, p=0.36). The mean (SD) 30-day hospital care cost per patient with MIS was £8323 (13,133) for those referred to hospital versus £743 (1794) for those referred to the outpatient clinic, representing a mean significant difference of £7567 (95% CI of the difference: 5866 - 9269; p<0.0001) per patient. After adjusting for NIHSS score, history of atrial fibrillation, days to medical presentation and living arrangements, the adjusted mean 30-day hospital care cost per patient with MIS was £5852 for those referred to hospital versus £973 for those referred to the outpatient clinic (p<0.0001). In those presenting within 24 hours, the mean (SD) 30-day hospital care cost per patient was £8327 (13,342) for those seen in hospital versus £807 (1765) for those seen in the outpatient clinic representing a mean significant difference of £7520 (95% CI of the difference: 5444 - 9596; p<0.0001) per patient.

Of the 8 recurrent strokes requiring admission after MIS within 30 days of discharge from both settings, 6 were ischaemic, 1 was a PICH and 1 was due to CNS vasculitis. The recurrent stroke risk remained similar in patients treated in the clinic compared with those managed in hospital at one year (11.6% (27/237, 7.6-15.8) vs 13.1% (18/150, 7.4-18.8),OR 0.9 (0.48-1.87, p=0.72) and five year follow–up (21.2% (15.5-26.9) vs 20.5% (14.2-26.8) p=0.84).

Regarding other causes of 30-day admission in clinic-referred patients with MIS, 3 were due to sepsis and 3 because of falls. Admission for nursing care was not common (1 patient). The 30 day outcomes after clinic managed patient with TIA were similar (12/326, 4.0% vs 16/237, 6.8%, p=0.12) patients requiring readmission within 30 days of clinic discharge. 4 patients (2 TIA, 2 MIS) were admitted due to bleeding (3 gastrointestinal, 1 gynaecological). In all cases, bleeding occurred later, at 8-30 days after clinic discharge.

Amongst 387 patients with MIS discharged from secondary care, rates of secondary prevention implementation were high, though there were differences between patients seen in hospital and those seen in the clinic (Table 3). Patients treated in hospital were more likely to receive warfarin (12.7% vs 6.3%, p=0.04). Patients seen in clinic were more likely to receive lipid lowering therapy (p<0.001). Similar proportions of patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis ≥50% were referred for carotid endarterectomy in both settings (32%, 9/28 vs 20%, 2/10, p=0.69). At 1 year follow up, higher rates of statin use in clinic referred patients remained (84%, 190/225 vs 69%, 81/117, p=0.002).

Table 3.

Secondary prevention measures at discharge and one year follow-up in patients with MIS seen in the clinic and hospital, n=387

| At discharge | One year follow-up† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke clinic n=237 (%) | Acute hospital n=150 (%) | p | Stroke clinic n=225(%) | Acute hospital n=117 (%) | p | |

| Antiplatelet | 206 (86.9) | 112 (74.7) | 0.003 | 182 (80.9) | 90 (76.9) | 0.40 |

| Warfarin | 15 (6.3) | 19 (12.7) | 0.04 | 24 (10.7) | 14 (12.0) | 0.72 |

| Lipid lowering | 199 (84.0) | 103 (68.7) | <0.001 | 190 (84.4) | 81 (69.2) | 0.002 |

| At least 1 anti-hypertensive | 183 (77.2) | 115 (76.7) | 0.90 | 183 (81.3) | 90 (76.9) | 0.39 |

| 2 or more antihypertensives | 113 (47.7) | 57 (38.0) | 0.07 | 128 (56.9) | 59 (50.4) | 0.3 |

| Symptomatic carotid stenosis ≥50%* | 28 (11.8) | 10 (6.7) | 0.58 | |||

| Referred for carotid endarterectomy | 9 (3.8) | 2 (1.3) | 0.22 | |||

48 cases without carotid imaging (3 clinic cases, 45 hospital cases)

50 cases dead at 1-year (21 clinic cases, 29 hospital cases), data missing on 4 hospital cases

Discussion

Clinics offering urgent assessment and treatment after TIA have been shown to have good outcomes and to be cost-effective.3,4,19 Our study of the feasibility, safety and cost of management of patients with minor stroke in a specialised outpatient clinic showed that the 30-day recurrent stroke risk and unplanned admission rates were low, with similar outcomes to those after hospital treatment of minor stroke, recognizing, of course, that there were differences in clinical characteristics of patients referred to clinic versus admitted to hospital. However, after controlling for these differences in a regression analysis, our results showed savings, of around £4800 per patient treated in clinic, with patients seen in hospital costing over 6 times more after adjusting for patient characteristics.

The outpatient clinic treated 40% of patients with stroke and 61% of those with minor stroke in our study population. We found that 80% of patients with minor stroke sought medical attention within 24 hours, of which 72% first presented to their primary care physician. In a similar US survey, 88% of stroke patients presenting to family practices were evaluated on the day of symptom onset, but two thirds were hospitalised,1 whereas two thirds were managed as outpatients in our study. We found similar delays to secondary care as in a Dutch study of management of TIA and stroke in which 71% of hospital-admitted patients arrived within 24 hours of onset compared to 17% of outpatients.20 This study also found less use of secondary prevention measures amongst admitted patients,20 in keeping with our finding of lower rates of lipid-lowering therapy in this group. The reasons for this may be physician or patient related.

Potential advantages of hospitalisation after TIA include early access to thrombolysis to treat recurrent stroke,21 but thrombolysis would generally not be indicated to treat recurrence after minor stroke due to the increased risk of intracerebral haemorrhage, but admission may provide early access to secondary prevention and rehabilitation. However, nearly all clinic managed patients in our study received antiplatelet therapy and more than three quarters received statins, suggesting secondary prevention was at least as good as in the hospital.

The disadvantages of outpatient assessment may be related to delays in appointment times therefore missing the opportunity for early intervention, but recurrent stroke rates in our study were similar in both settings, and most recurrences after clinic assessment occurred in the pre-EXPRESS phase of our study where delays to clinic assessment were greater and there was a delay to subsequent initiation of secondary prevention in primary care.

The risk of recurrent stroke and other complications are highest during the first days after a minor stroke.3,4,22–26 We found 4% of clinic referred patients with minor stroke were admitted directly after their appointment for further investigations or nursing care in hospital. In those additional patients subsequently admitted after clinic discharge, it is possible that initial hospitalisation could have reduced the likelihood of adverse outcomes such as falls. However, since up to 96% of patients hospitalised for stroke experience medical or neurological complications during their admission27, the benefit of outpatient care in avoiding hospitalisation related morbidity, such as hospital-acquired infection, also should be considered. We found the 30-day unplanned admission rate after clinic attendance after minor stroke was similar to that in patients with TIA discharged from the clinic.

Our study did not assess patients' preferences for treatment, but many patients may prefer outpatient management if it is considered safe. Patients should be informed which treatments are available and their preferences should be taken in account.28 Such an approach may increase adherence to treatment and decrease dissatisfaction, two additional potential gains of outpatient treatment for medically stable patients.28,29 On the other hand, it may be that hospitalisation reinforces the seriousness of the event and alleviates concerns about potential side effects of secondary prevention which may lead to better treatment adherence.31,32 However, in our study, rates of secondary prevention at one year were as high in clinic managed patients compared with hospital managed patients. Finally, the economic aspect of hospitalisation of TIA and minor stroke patients should also be considered. We showed that the cost of outpatient management of minor stroke was substantially lower than inpatient care.

The main strengths of the present study are its population-based design, rigorous ascertainment and follow-up. The possibility of selection and misclassification bias was minimised since all stroke patients presenting for medical attention in the study population were prospectively recruited, and outcomes were assessed by assessors blinded to the study hypotheses.15,16 However, our study has also limitations. First, it was not a randomised comparison of different management strategies. Randomised assessment may not be feasible as patients may not consent to random allocation to either setting of care. We simply aimed to determine the outcomes in those patients that family doctors considered appropriate for referral for potential outpatient management. We acknowledge that non-randomised allocation to either group may have favoured outcomes in the clinic-referred group due to systematic bias, indeed we found those referred to the outpatient clinic tended to have less severe strokes and different aetiologies to those admitted directly to hospital. However, there was considerable overlap between the groups, all had NIHSS<3, and 68% of patients with minor stroke in our population who sought medical attention from family practitioners within 24 hours of symptom onset were referred to the clinic. Second, differences in baseline characteristics in the clinic managed group may have influenced GPs decision to refer to the clinic rather than the hospital. However, whilst we have presented outcomes after clinic discharge, we did study events after referral and before clinic attendance and there were only 2 patients with recurrent stroke. Third, the median length of stay was long in our study, if this was shorter, for example in other countries, the cost savings may be less. Fourth, we did not assess patients’ preferences, but it is common for patients to prefer to avoid hospital admission where possible. Fifth, we did not assess the cost of follow up, indirect costs or long-term disability. It may be that early access to rehabilitation in hospital reduces long-term disability which may offset the initial cost-savings of clinic care. However, this effect is unlikely to be substantial in patients with minor stroke.

In conclusion, our non-randomised study shows that rapid assessment and treatment of minor stroke can be achieved in the outpatient clinic and the complication rate of outpatient management is relatively low. A randomised comparison of either treatment setting would be justified although may not be feasible due to limited patient acceptability of either treatment.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

The Oxford Vascular Study is funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Dunhill Medical Trust, Stroke Association, BUPA Foundation, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Thames Valley Primary Care Research Partnership, NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford, and the Wellcome Trust. Professor Rothwell is in receipt of an NIHR Senior Investigator Award and Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Statemement

Nicola L M Paul MRCP: study concept and design, acquisition of data, draft and revision of the manuscript, statistical analysis and interpretation of data.

Silvia Koton PhD: revision of the manuscript content, acquisition of data

Michela Simoni MRCP: revision of the manuscript content, acquisition of data.

Olivia Geraghty MRCP: revision of the manuscript content, acquisition of data.

Ramon Luengo-Fernandez PhD: revision of the manuscript content, economic analysis, acquisition of data.

Professor Peter M Rothwell PhD FMedSci: study concept and design, draft and revision of the manuscript, analysis and interpretation of data, study supervision.

Contributor Information

Silvia Koton, Stanley Steyer School of Health Professions, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University, Israel.

Ramon Luengo-Fernandez, Health Economics Research Centre, Department of Public Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

References

- 1.Goldstein LB, Bian J, Samsa GP, et al. New transient ischemic attack and stroke: outpatient management by primary care physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2941–2946. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.19.2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roebers S, Wagner M, Ritter MA, et al. Attitudes and current practice of primary care physicians in acute stroke management. Stroke. 2007;38:1298–1303. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000259889.72520.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavallee PC, Meseguer E, Abboud H, et al. A transient ischaemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access (SOS-TIA): Feasibility and effects. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:953–960. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70248-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370:1432–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party. National clinical guideline for stroke. 3rd edition. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National collaborating centre for chronic conditions. Diagnosis and initial management of acute stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA) [Accessed May 3 2011]; NICE clinical guideline 68. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG68/NICEGuidance/pdf/English.

- 7.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of patients with stroke or TIA: assessment, investigation, immediate management and secondary prevention: A national clinical guideline. [Accessed May 3 2011];2008 www.sign.ac.uk.

- 8.Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients with Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:227–276. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181f7d043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Stroke Foundation (Australia): Melbourne. Clinical Guidelines for Acute Stroke Management. [Accessed May 3 2011];2007 www.strokefoundation.com.au/acute-clinical-guidelines-for-Acute-stroke-management.

- 10.The European Stroke Organisation (ESO) Executive Committee and the ESO Writing Committee. Guidelines for management of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack 2008. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:457–507. doi: 10.1159/000131083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stroke foundation of New Zealand. New Zealand guideline for the assessment and management of people with recent transient ischaemic attack (TIA) [Accessed May 3 2011];2008 www.stroke.org.nz.

- 12.The Stroke Prevention and Educational Awareness Diffusion (SPREAD) Collaboration. The Italian Guidelines for stroke prevention. Neurol Sci. 2006;21:5–12. doi: 10.1007/s100720070112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canadian Stroke Strategy: Canadian Best Practice Recommendations for Stroke Care: 2006. Canadian Stroke Network and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada; Ottawa: [Accessed May 3 2011]. www.canadianstrokestrategy.ca/eng/resourcestools/documents/StrokeStrategyManual.pdf.. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwamm LH, Pancioli A, Acker JE, 3rd, et al. Recommendations for the establishment of stroke systems of care: recommendations from the American Stroke Association's Task Force on the Development of Stroke Systems. Stroke. 2005;36:690–703. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000158165.42884.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Giles MF, et al. Change in stroke incidence, mortality, case-fatality, severity, and risk factors in Oxfordshire, UK from 1981 to 2004 (Oxford Vascular Study) Lancet. 2004;363:1925–1933. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Silver LE, et al. Population-based study of event-rate, incidence, case fatality, and mortality for all acute vascular events in all arterial territories (Oxford Vascular Study) Lancet. 2005;366:1773–1783. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67702-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brott T, Adams HP, Jr, Olinger CP, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20:864–870. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.7.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams HP, Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luengo-Fernandez R, Gray AM, Rothwell PM. Effect of urgent treatment for transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on disability and hospital costs (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:235–243. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scholte op Reimer WJ, Dippel DW, Franke CL, et al. Quality of hospital and outpatient care after stroke or transient ischemic attack: insights from a stroke survey in the Netherlands. Stroke. 2006 Jul;37:1844–1849. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000226463.17988.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen-Huynh MN, Claiborne Johnston S. Is hospitalization after TIA cost-effective on the basis of treatment with tPA? Neurol. 2005;65:1799–1801. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187067.93321.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369:283–292. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Flossmann E, et al. A simple score (ABCD) to identify individuals at high early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2005;366:29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66702-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothwell PM, Buchan A, Johnston SC. Recent advances in management of transient ischaemic attacks and minor ischaemic strokes. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:323–331. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coull AJ, Lovett JK, Rothwell PM. Population based study of early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke: implications for public education and organisation of services. BMJ. 2004;328:326. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37991.635266.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, et al. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA. 2000;284:2901–2906. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingeman A, Andersen G, Hundborg HH, et al. Processes of care and medical complications in patients with stroke. Stroke. 2011 Jan;42:167–172. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.599738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowling A, Ebrahim S. Measuring patients' preferences for treatment and perceptions of risk. Qual Health Care. 2001;10(Suppl 1):i2–i8. doi: 10.1136/qhc.0100002... [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asplund K, Jonsson F, Eriksson M, et al. Patient dissatisfaction with acute stroke care. Stroke. 2009;40:3851–3856. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.561985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ovbiagele B, Saver JL, Fredieu A, et al. In-hospital initiation of secondary stroke prevention therapies yields high rates of adherence at follow-up. Stroke. 2004;35:2879–2883. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000147967.49567.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Touzé E, Coste J, Voicu M, et al. Importance of in-hospital initiation of therapies and therapeutic inertia in secondary stroke prevention: IMplementation of Prevention After a Cerebrovascular evenT (IMPACT) Study. Stroke. 2008;39:1834–1843. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.503094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Josephson SA, Sidney S, Pham TN, et al. Factors associated with the decision to hospitalize patients after transient ischemic attack before publication of prediction rules. Stroke. 2008;39:411–413. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.491316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]