Abstract

Importance

Visualization and interpretation of the optic nerve and retina is an essential part of most physical examinations.

Objectives

To design and validate a smartphone-based retinal adapter enabling image capture and remote grading of the retina

Design, setting and participants

Validation study comparing the grading of optic nerves from smartphones images with those of a Digital Fundus Camera. Both image sets were independently graded at Moorfields Eye Hospital Reading Centre. Nested within the six-year follow-up of the Nakuru Eye Disease Cohort in Kenya: 1,460adults (2,920eyes) aged 55years and above were recruited consecutively from the Study. A sub-set of 100 optic disc images from both methods were further used to validate a grading app for the optic nerves.

Main outcome(s) and measure(s)

Vertical cup-to-disc-ratio (VCDR) for each test was compared, in terms of agreement (Bland-Altman & weighted Kappa) and test-retest variability (TRV).

Results

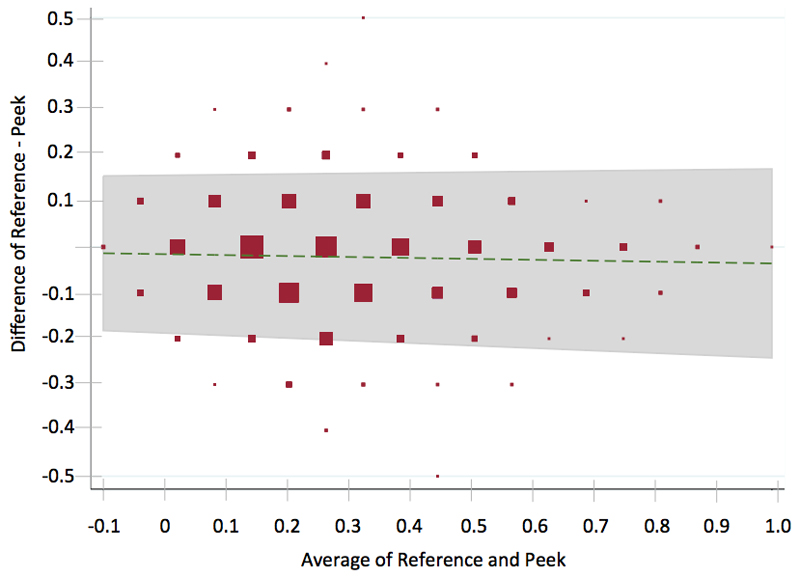

2,152 optic nerve images were available from both methods (additionally 371 from reference but not Peek, 170 from Peek but not the reference and 227 from neither the reference camera or Peek). Bland-Altman analysis demonstrated a difference of the average of 0.02 with 95% limits of agreement between -0.21 and 0.17 and a weighted Kappa coefficient of 0.69 (excellent agreement). An experienced retinal photographer was compared to a lay photographer (no health care experience prior to the study) with no observable difference in image acquisition quality between them.

Conclusions and relevance

Non-clinical photographers using the low-cost Peek Retina adapter and smartphone were able to acquire optic nerve images at a standard that enabled comparable independent remote grading of the images to those acquired using a desktop retinal camera operated by an ophthalmic assistant. The potential for task-shifting and the detection of avoidable causes of blindness in the most at risk communities makes this an attractive public health intervention.

Background

285 million people are visually impaired worldwide (Snellen Acuity <6/18) of whom 39 million are blind (<3/60 better eye). Low-income countries carry approximately 90% of the burden of visual impairment and 80% of this can be prevented or cured.1

There is a widening gap between the number of eye-health practitioners worldwide and increasing need as populations enlarge and age. Blinding eye disease is most prevalent in older people, and in many regions the population aged 60 years and over is growing at twice the rate of the number of practitioners.2,3

Diseases of the posterior segment are responsible for up to 37% of blindness in sub-Saharan Africa.4 However, diagnosis, monitoring and treatment are challenging in resource-poor countries due to a lack of trained personnel and the prohibitive cost of imaging equipment.

Retinal imaging is frequently used in disease diagnosis and monitoring such as diabetic retinopathy (DR), glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration (AMD), Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP) 5 and systemic diseases such as hypertension 6 , malaria 7, HIV/AIDS 8 and syphilis.9

Ophthalmologists, physicians and eye-care workers have used ophthalmoscopes of varying types for more than a hundred-and-fifty years with the first reported use by Dr William Cumming in 1846.10 The development of fundus cameras has made it possible to record and share images to collect evidence of disease presence, severity and change.

The advent of digital imaging has made recording, processing and sharing of images far quicker and cheaper than previous film based methods.11 However fundus cameras remain impractical in many low-income countries and in primary care settings throughout the world where early detection of eye disease is prohibited due to high cost, large size, low portability, infrastructure requirements (e.g. electricity and road access) and difficulty of use.

Mobile phone access has reached near ubiquitous levels worldwide 12 with the highest growth rate of mobile phone ownership worldwide being in Africa. Telemedicine has in recent years begun to favour wireless platforms. With newer smartphone devices having high powered computational functions, cameras, image processing and communication capabilities. 13 Mobile phone cameras have shown promise when attached to imaging devices such as microscopes 14 and slit-lamp biomicroscopes, 15 however they remain impractical in many remote settings due to size and expense of the equipment to which the smartphone is attached. The development of a hand-held smartphone device used in clinical microscopy has proven successful.16

Retinal imaging is in principle similar to using a microscope, however it is more complex due to the interaction between the camera optics with the optics and illumination of the eye. 17

The goal of the Peek Retina prototype was to demonstrate the feasibility of creating a portable mobile phone retinal imaging system that is appropriate for field use in Kenya and similar contexts, characterized by portability, low-cost and ease of use by minimally trained personnel. Our primary aim was to validate such a smartphone adapter for optic nerve imaging in the context of a population-based study in Nakuru, Kenya.18

Methods

Participants

Participants included in the study were from the follow-up phase of a population-based cohort study on eye disease in Kenya (January 2013 to March 2014).18 100 clusters were selected at the baseline in 2007/08 with a probability proportional to the size of the population.19

Households were selected within clusters using a modified compact segment sampling method.20 Each cluster was divided into segments so that each segment included approximately 50 people aged ≥50years. An eligible individual was defined as someone aged ≥50 years living in the household for at least three months in the previous year at baseline and who was found and consented to follow-up assessment six-years later (2013-14).

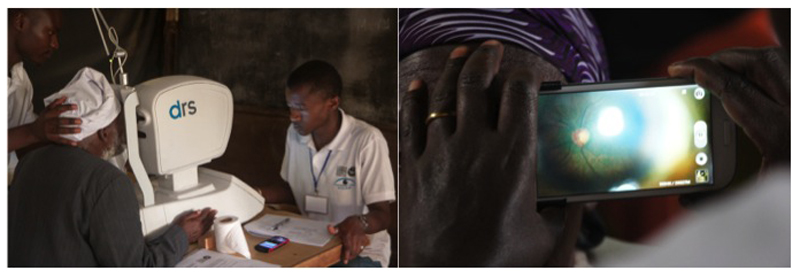

Peek Retina was available for use in the final 75 of the 100 clusters re-visited and all available participants in those clusters were examined. All participants were examined with both Peek Retina and a desktop fundus camera (CentreVue+ Digital Retinal System (DRS), Haag-Streit), which acted as the reference standard.

Ethical Approval

The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committees of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and the African Medical and Research Foundation (AMREF), Kenya. Approval was also granted by the Rift Valley Provincial Medical Officer and the Nakuru District Medical Officer for Health. Approval was sought from the administrative heads in each cluster, usually the village chief.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The objectives of the study and the examination process were explained to those eligible in the local dialect, in the presence of a witness. All participants gave written (or thumbprint) consent.

Test Methods

Pharmacologic dilation in all subject’s pupils was achieved using tropicamide 1% (minims) with phenylephrine 2.5% (minims) if needed. Dilation was not performed in subjects deemed at risk of narrow angle closure (inability to visualise >180° of posterior pigmented trabecular meshwork on non-indentation gonioscopy at the slit-lamp by the study ophthalmologist 21).

Examination using the reference camera and Peek Retina was performed in a dimly lit room, however conditions slightly varied between clusters. An ophthalmic assistant took retinal images with the reference camera and one of two operators/photographers used Peek Retina, all users were masked to the alternative examination. The two examinations took place in different rooms where availability allowed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

[Left] The DRS Camera (Reference Camera) and [Right] Peek Retina

Reference Retinal Photography

An Ophthalmic Assistant performed digital photography of the lens and fundus on all study participants using the reference camera, which is approved for national diabetic retinopathy screening in the UK [http://diabeticeye.screening.nhs.uk/cameras]. Two 45° fundus photographs were taken in each eye, one optic disc centered and the other macula centered. Images were then securely uploaded to the Moorfields Reading Centre (MEHRC) for review and grading.

Peek Retina Photography of the optic disc

An experienced ophthalmic clinical officer or a lay technician with no healthcare background used a Samsung SIII GT-I9300 (Samsung C&T Corp., Seoul, Republic of Korea) and it’s native 8.0 Megapixel camera with the Peek Retina adapter (eFigure 1) to perform dilated retinal examinations on study participants. Images were recorded as video (approximate three-ten seconds/3-7MB per eye) with single frames (<0.5MB) used for disc analysis. Both examiners, henceforth termed “photographers” received basic training in anatomy and the identification of retinal features (including optic nerve and optic cup) at the beginning of the study.

Peek Retina consists of a plastic clip that covers the phone camera and flash (white LED) with a prism assembly. The prism deflects light from the flash to match the illumination path with the field of view of the camera to acquire images of the retina; the phone camera and clip are held in front and at close proximity to the eye. This allows the camera to capture images of the fundus. 22 A video sweep of the optic disc was performed using the Peek Retina adapter on a smartphone using the native camera app on each eye and securely uploaded to MEHRC for review and grading. A one-hour training session on how to use Peek Retina was delivered prior to the study commencing.

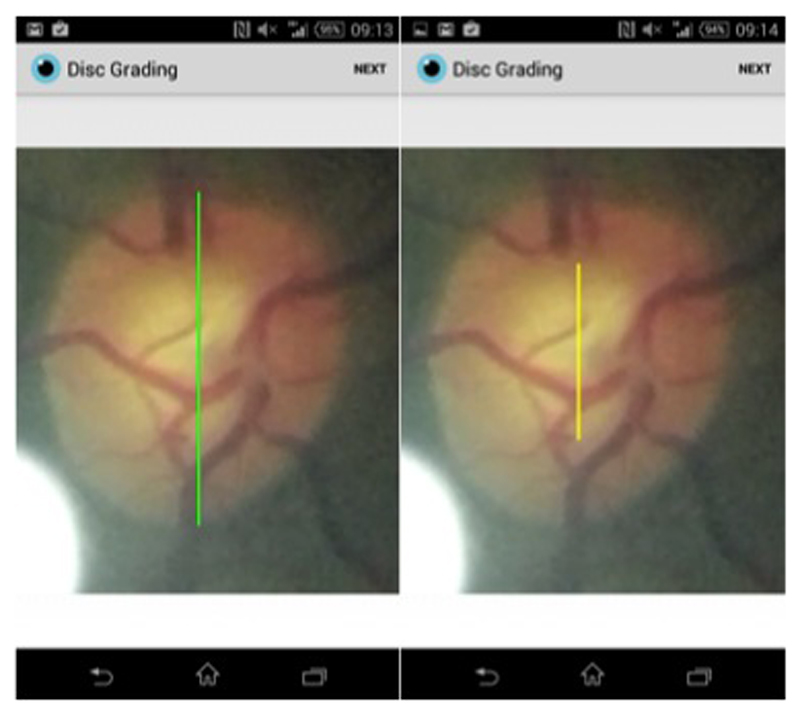

In a random subset of 100 optic nerve examinations acquired using Peek Retina, bespoke software (Peek Grader, Figure 2) was used by two local study examiners (one non-ophthalmologist experienced in retinal examination, one with no healthcare training, independent of the original photographers) to select still images of the optic disc from the video sweep and use on-screen calipers to measure the vertical cup-to-disc-ratio with no training provided beyond in app instructions on caliper placement.

Figure 2.

Peek Grader being used to measure vertical cup to disc ratio on the phone

Data management and analysis – Moorfields Reading Centre

All images were first examined on a large screen display for quality. For gradable images two independent graders reviewed optic disc pairs.

In case of grading difficulties, the adjudicator (TP) determined the image grade and verified a random sample of 10% of images for quality assurance and control. Graders re-graded a random selection of 100 images after a minimum of 14-days to assess intragrader reliability. The adjudicator also graded 5% of randomly selected images to ensure quality control. Data was consistency checked by a data monitor. Optic disc images were graded as normal, suspicious or abnormal. A disc was considered abnormal if there was neuro-retinal rim (NRR) thinning as defined by the ISNT rule23, notching or disc hemorrhage present, if the Vertical Cup to Disc Ratio (VCDR) was ≥0.7. A suspicious disc was one where adjudication was necessary to determine if its appearance was abnormal.

Service Provision

All participants identified with treatable disease in this study were offered appropriate care including free surgery and transport to the Rift Valley General Provincial Hospital or St Mary’s Mission Hospital, Elementita. A trained ophthalmic nurse or Ophthalmic Clinical Officer (OCO) discussed the diagnosis and provided counseling to subjects. In addition, non-study attendees were examined and treated by the study team.

Analyses

We used the Bland-Altman method24 to analyze agreement and repeatability between and within diagnostic tests and weighted Kappa scores to compare the VCDR measurements made on different images sets or on re-grading 24,25 For Kappa weighted agreement of VCDR between observers and imaging methods the following weights were applied: 1.0 for a 0.0 difference, 0.95 for a 0.05 difference, 0.90 for a 0.10 difference, 0.50 for a 0.15 difference, 0.20 for a 0.20 difference and 0.00 for all differences >0.20 as used in a previous analysis of disc agreement. 25 We performed the following specific comparisons:

Reference DRS Image Repeatability: subset of 100 optic disc images randomly selected for repeat grading by an MEHRC grader to assess intra-observer agreement.

Peek Retina Repeatability: subset of 100 optic disc images randomly selected for repeat grading by MEHRC grader to assess intra-observer agreement (the same subjects as used for reference image intra-observer repeatability assessment).

Reference DRS images (by expert grader on large screen) vs. Peek Retina images using the on-screen calipers in Peek Grader, Figure 2), the same 100 images as comparisons 1 and 2.

Peek Retina images (by MEHRC grader on large screen) vs. Peek Retina images (by field ophthalmologist or lay person using Peek Grader), the same 100 images as comparisons 1 and 2.

Reference DRS images (by MEHRC grader) vs. Peek Retina images (by MEHRC grader, on large screen): all 2,152 image pairs analyzed together.

Reference DRS images (by MEHRC grader) vs. Peek Retina images (by MEHRC grader, on large screen): 2,152 image pairs subdivided by whether the images were collected by either an experienced photographer or a lay photographer.

Results

Participants

Recruitment took place between January 2013 and March 2014. A total of 1,460 individuals from 75 clusters participated. Their mean age was 68 years (S.D. 9.4; total range 55–99 years) and 700(52%) were female. Participants underwent retinal examination using Peek and the standard desktop retinal camera. A total of 2,920 eyes were imaged, of which 2,152(74%) eyes had gradable images from both Peek and the reference camera. In 170 eyes a gradable image was obtainable with Peek but not the reference camera and conversely, in 371 eyes a gradable image was obtainable with the reference camera but not with Peek. In 227 eyes a disc image was not possible from either modality. (eFigure 2)

Reference Image Disk Parameters

The VCDR parameters derived from the analysis of the 2,152 Reference DRS images from this population (eFigure 3), using the definitions in the International Society for Geographical & Epidemiological Ophthalmology (ISGEO) classification were: mean VCDR 0.38, 97.5th percentile VCDR 0.7 and 99.5th percentile VCDR 0.9.

Intra-observer Repeatability

A set of images from 100 eyes were used to assess intra-observer repeatability. Bland-Altman analysis and Kappa scores found excellent intra-observer repeatability for MEHRC graders for both the Reference DRS images (Comparison 1, Table 1) and Peek Retina images (Comparison 2, Table 1).

Table 1.

Agreement (Bland-Altman and Weighted Kappa) of optic disc VCDR scores between different imaging modalities and different graders. The comparison number relates to the specific comparisons that are described in the methodology section.

| Comparison Number | Reference Image | Comparison Image | Number | VCDR |

Weighted Kappa (SD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Difference | 95% limits of agreement | ||||||||||

| Camera | Grader | Screen | Camera | Grader | Screen | Upper | Lower | ||||

| 1 | DRS | Expert | Large | DRS | Expert | Large | 100 | -0.07 | 0.07 | -0.21 | 0.90 (0.01) |

| 2 | Peek | Expert | Large | Peek | Expert | Large | 100 | -0.01 | 0.16 | -0.18 | 0.77 (0.04) |

| 3a | DRS | Expert | Large | Peek | Ophth | Phone | 100 | -0.08 | -0.11 | -0.53 | 0.30 (0.07) |

| 3b | DRS | Expert | Large | Peek | Non-Ophth | Phone | 100 | -0.07 | 0.24 | -0.38 | 0.19 (0.06) |

| 4a | Peek | Expert | Large | Peek | Ophth | Phone | 100 | -0.08 | -0.11 | -0.56 | 0.35 (0.07) |

| 4b | Peek | Expert | Large | Peek | Non-Ophth | Phone | 100 | -0.06 | 0.21 | -0.33 | 0.25 (0.06) |

| 5 | DRS | Expert | Large | Peek | Expert | Large | 2,152 | 0.02 | 0.17 | -0.21 | 0.69 (0.01) |

| 6a | DRS | Expert | Large | Peek (Exp.Exam) | Expert | Large | 1,239 | -0.02 | 0.17 | -0.20 | 0.68 (0.02) |

| 6b | DRS | Expert | Large | Peek (Lay Exam) | Expert | Large | 913 | -0.02 | 0.16 | -0.21 | 0.71 (0.02) |

Note: DRS = reference desktop camera image. Peek = smartphone image. Expert = independent trained grader/image reader. Phone = smartphone on-screen disc grading application. Ophth = App grading performed by ophthalmologist. Non-Ophth = App grading performed by non health care worker.

Comparison of Expert and Field Grading

For the same 100 eyes we compared the VCDR measured on the Reference DRS images by the MEHRC grader and the images of the same eye taken using Peek Retina with the VCDR graded on the phone screen (Figure 2) by either an ophthalmologist (Comparison 3a, Table 1) or a lay person (Comparison 3b, Table 1). Although the mean difference of the average by Bland-Altman was less than 0.1 the weighted Kappa scores were relatively low. We performed a similar analysis with using the Peek image graded by the MEHRC grader, compared to the VCDR measured using Peek Grader (Comparisons 4a and 4b, Table 1). Again we found a small difference in the mean difference of the average but low Kappa scores.

Comparison of Reference Image with Peek Retina Images

We compared (Comparison 5, Table 1) the VCDR measured by an expert grader (MEHRC) from Peek Retina and Reference DRS images for 2,152 eyes (eTable 1). The Bland-Altman analysis demonstrated a mean difference of the average of -0.02 with 95% limits of agreement between -0.21 and 0.17 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Bland-Altman Plot of 2,152 optic nerve images taken from both the reference camera and Peek Retina, both graded by an expert grader at Moorfields Eye Hospital Reading Centre.

Inter-Examiner Variability

Two members of the field team collected retinal images using Peek Retina. The first was a trained eye care worker and experienced in the assessment of the retina (Experienced photographer). The second had no prior health care or eye care experience but was proficient in the use of a smartphone (Lay photographer). A Bland-Altman analysis was performed comparing the Reference images and Peek Retina images, both graded at MEHRC. For the 1,239 eyes that had Peek Retina images collected by the experienced retinal photographer the difference of the average was -0.02 with 95% limits of agreement between -0.22 to 0.17 (Comparison 6a, Table 1). For the 913 eyes that had Peek Retinal images collected by the lay photographer the difference of the average was also -0.02 with 95% limits of agreement between -0.20 and 0.16 (Comparison 6b, Table 1). There was no observable difference in image acquisition quality between the experienced retinal photographer and lay photographer.

Discussion

The findings of this study are discussed within the context of optic disc imaging in a population-based study in Kenya. We compared the performance of two imaging modalities and different image grading expertise. The results demonstrate that Peek Retina images, when analysed by an independent expert show excellent agreement with images from a reference desktop camera read by the same expert.

Intra-observer agreement within imaging modalities also showed excellent agreement for both the reference camera and Peek Retina images. This indicates a high degree of confidence to be able to measure real change over time when a threshold for VCDR increase 0.2 or greater is used.

Although the Bland-Altman limits of agreement were acceptable for all comparisons, the Peek Grader App, particularly when performed by a non-clinically trained user were of only fair or slight agreement with the expertly graded reference image. The lower levels of agreement with the Grader App may be accounted for by images being graded on a small screen with no user guidance given beyond basic instructions within the app to “measure the disc” and “measure the cup”.

Although stereoscopic disc images are the preference for optic nerve grading it has been shown that monscopic images, as used in this study do not represent a significant disadvantage for grading glaucoma likelihood. 26

The finding that non-clinically trained personnel can acquire images of the optic disc using a low-cost smartphone adapter that are of a standard that is comparable to desktop retinal camera operated by a dedicated ophthalmic technician/assistant suggests there is great potential for use of such devices in mHealth and tele-ophthalmology.

In this study we only assessed optic disc features, however, potential use in retinal diseases warrants further investigation, the findings of which would have implications for diabetic retinopathy screening programs. Previously described uses of smartphone-based cameras for diabetic retinopathy have been in a clinic setting when operated by a retinal specialist and found to provide good agreement with slit-lamp biomicroscopy examination also performed by a retinal specialist. 27,28 Further assessment of smartphone-based tools by non-specialists in non-ophthalmic settings is warranted.

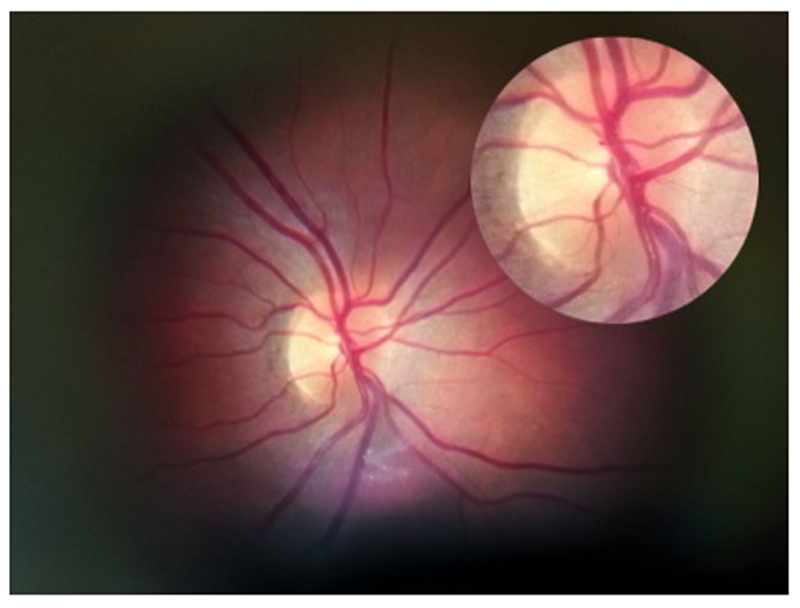

A limitation of this study, typical of clinical research based on highly iterative technologies is that, in relying on rapidly evolving platforms, the time to dissemination of results is long compared with the evolution of the technology itself. This often results in the presentation of data from technology that has been superseded by subsequent prototypes or commercially available devices. In this field study, an early iteration of Peek Retina (internally identified as Mark II) was used throughout. However, by the time of completing the analysis, a more advanced iteration of Peek Retina (Mark VI) was available. An image acquired using Mark VI is shown in Figure 4. When compared to Figure 2, which shows an image from Mark II, a significant improvement is evident.

Figure 4.

Retina and optic disc image from Peek Retina Mark VI taken through a dilated pupil with an approximate field of view of 20-30 degrees. The optic disc has been cropped and magnified.

A further limitation is that no evaluation of optic discs from either imaging modality was performed without mydriasis. Previous investigations have found the limits of agreements between non-mydriatic optic disc grading to be outside clinically acceptable levels.29 Anecdotally we found it possible to acquire good optic nerve images in undilated pupils of 2.5-3.0mm diameter.

Peek Retina prototypes, subsequent commercially available devices and alternative portable retinal imaging systems could contribute to tackling avoidable blindness and in screening for diseases with eye manifestations, particularly in low-income countries and remote communities where mobile phone infrastructure is ubiquitous but trained personnel are few. Existing telecommunications infrastructure can enable greater access to health care by permitting timely diagnosis using data sharing via the communication capabilities intrinsic to the phone. With the development of automated retinal imaging systems (ARIS), 30 we could soon see real time diagnostics by a technician, rather than by the more scarcely available eye care personnel.

Coupling imaging with other smartphone based diagnostic tests31 and geo-tagging enables database creation of examined individuals based on pre-determined parameters as demonstrated by systems such as EpiCollect.32 Such systems make follow-up and epidemiological data collection more feasible in resource-poor settings.

Smartphone penetration continues to increase with higher computing power, purpose built software and hardware, greater connectivity and lower handset costs, there is now an opportunity to reach the most underserved populations in a manner that was not possible just a decade ago.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment of Funding: The Nakuru Eye Disease Cohort Study was jointly funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC) and the Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement and Fight for Sight. Additional funding supporting the study (equipment and field staff) were provided by the International Glaucoma Association and the British Council for the Prevention of Blindness (BCPB). MJB is supported by the Wellcome Trust (Reference Number 098481/Z/12/Z).

Peek Vision research is funded under the Commonwealth Eye Health Consortium by the Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Trust.

The funding bodies had no involvement with design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript

Kevin Wing - Analysis

Peter Blows - analysis

Arrianne O’Shea - analysis

Footnotes

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years,other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

The principal author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

The principal author had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis

Roles of the authors:

Design and conduct of the study: AB, HK, MJB

Collection: AB, HKR

Management: AB, HKR

Analysis: AB, HAW, NS, TP, SH

Interpretation of data: AB, IATL, HAW, SH, HK, MJB

Manuscript preparation: AB, MJB

Manuscript review: AB, IATL, HAW, TP, HK, MJB

Approval of manuscript: AB, IATL, HAW, SJ, HK, MJB

References

- 1.Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2011 Dec 1; doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnikoff S, Felch W, Gauthier TM, Spivey B. The number of ophthalmologists in practice and training worldwide: a growing gap despite more than 200 000 practitioners. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2012 Mar 26; doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastawrous A, Hennig BD. The global inverse care law: a distorted map of blindness. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2012 Jun 27; doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bastawrous A, Burgess PI, Mahdi AM, Kyari F, Burton MJ, Kuper H. Posterior segment eye disease in sub-Saharan Africa: review of recent population-based studies. Trop Med Int Health. 2014 May;19(5):600–609. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott KE, Kim DY, Wang L, et al. Telemedical diagnosis of retinopathy of prematurity intraphysician agreement between ophthalmoscopic examination and image-based interpretation. Ophthalmology. 2008 Jul;115(7):1222–1228 e1223. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyman BN. The Eye as a Target Organ: An Updated Classification of Hypertensive Retinopathy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2000 May;2(3):194–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beare NA, Lewallen S, Taylor TE, Molyneux ME. Redefining cerebral malaria by including malaria retinopathy. Future Microbiol. 2011 Mar;6(3):349–355. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah JM, Leo SW, Pan JC, et al. Telemedicine screening for cytomegalovirus retinitis using digital fundus photography. Telemed J E Health. 2013 Aug;19(8):627–631. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2012.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu EX, Geraets RL, Dodds EM, et al. Superficial retinal precipitates in patients with syphilitic retinitis. Retina. 2010 Jul-Aug;30(7):1135–1143. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181cdf3ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman SE. The history of the ophthalmoscope. Doc Ophthalmol. 1989 Feb;71(2):221–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00163473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hildred RB. A brief history on the development of ophthalmic retinal photography into digital imaging. J Audiov Media Med. 1990 Jul;13(3):101–105. doi: 10.3109/17453059009055111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statistics. [Accessed 03.01.2012];2010 http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/statistics/index.html.

- 13.Tachakra S, Wang XH, Istepanian RS, Song YH. Mobile e-health: the unwired evolution of telemedicine. Telemed J E Health. 2003 Fall;9(3):247–257. doi: 10.1089/153056203322502632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimic M, Coronel J, Gilman RH, Luna CG, Curioso WH, Moore DA. Can the power of mobile phones be used to improve tuberculosis diagnosis in developing countries? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009 Jun;103(6):638–640. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lord RK, Shah VA, San Filippo AN, Krishna R. Novel uses of smartphones in ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2010 Jun;117(6):1274–1274 e1273. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breslauer DN, Maamari RN, Switz NA, Lam WA, Fletcher DA. Mobile phone based clinical microscopy for global health applications. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett TJ, Barry CJ. Ophthalmic imaging today: an ophthalmic photographer's viewpoint - a review. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2009 Jan;37(1):2–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bastawrous A, Mathenge W, Peto T, et al. The Nakuru eye disease cohort study: methodology & rationale. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014;14(1):60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathenge W, Bastawrous A, Foster A, Kuper H. The Nakuru Posterior Segment Eye Disease Study: Methods and Prevalence of Blindness and Visual Impairment in Nakuru, Kenya. Ophthalmology. 2012 Jun 19;119(10):2033–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner AG, Magnani RJ, Shuaib M. A not quite as quick but much cleaner alternative to the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) Cluster Survey design. Int J Epidemiol. 1996 Feb;25(1):198–203. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narayanaswamy A, Sakata LM, He MG, et al. Diagnostic performance of anterior chamber angle measurements for detecting eyes with narrow angles: an anterior segment OCT study. Archives of ophthalmology. 2010 Oct;128(10):1321–1327. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giardini ME, Livingstone IA, Jordan S, et al. A smartphone based ophthalmoscope. Conference proceedings : … Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual Conference; 2014. pp. 2177–2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harizman N, Oliveira C, Chiang A, et al. The ISNT rule and differentiation of normal from glaucomatous eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006 Nov;124(11):1579–1583. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.11.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986 Feb 8;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harper R, Radi N, Reeves BC, Fenerty C, Spencer AF, Batterbury M. Agreement between ophthalmologists and optometrists in optic disc assessment: training implications for glaucoma co-management. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001 Jun;239(5):342–350. doi: 10.1007/s004170100272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan HH, Ong DN, Kong YX, et al. Glaucomatous optic neuropathy evaluation (GONE) project: the effect of monoscopic versus stereoscopic viewing conditions on optic nerve evaluation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014 May;157(5):936–944. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russo A, Morescalchi F, Costagliola C, Delcassi L, Semeraro F. Comparison of smartphone ophthalmoscopy with slit-lamp biomicroscopy for grading diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015 Feb;159(2):360–364 e361. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan ME, Rajalakshmi R, Prathiba V, et al. Comparison Among Methods of Retinopathy Assessment (CAMRA) Study: Smartphone, Nonmydriatic, and Mydriatic Photography. Ophthalmology. 2015 Jul 15; doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirwan JF, Gouws P, Linnell AE, Crowston J, Bunce C. Pharmacological mydriasis and optic disc examination. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000 Aug;84(8):894–898. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.8.894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maker MP, Noble J, Silva PS, et al. Automated Retinal Imaging System (ARIS) Compared with ETDRS Protocol Color Stereoscopic Retinal Photography to Assess Level of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012 Mar 2; doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bastawrous A, Rono HK, Livingstone IA, et al. Development and Validation of a Smartphone-Based Visual Acuity Test (Peek Acuity) for Clinical Practice and Community-Based Fieldwork. JAMA ophthalmology. 2015 May 28; doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aanensen DM, Huntley DM, Feil EJ, al-Own F, Spratt BG. EpiCollect: linking smartphones to web applications for epidemiology, ecology and community data collection. PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e6968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.