Summary

Background

Depression, highly prevalent in HIV, is consistently associated with worse ART adherence. Integrating CBT for depression with adherence counseling using the “Life-Steps” approach (CBT-AD) has an emerging evidence base. The aim of the current study was to test the efficacy of CBT-AD.

Methods

We conducted a three-arm RCT (N=240 HIV-positive adults with depression), comparing CBT-AD to Life-Steps integrated with information and supportive psychotherapy (ISP-AD) (both 12 sessions), and to ETAU (1 session Life-Steps). Participants were recruited from three sites in New England area, two being hospital settings, and one being a community health center. Randomization was done via a 2:2:1 ratio, using random allocation software by the data manager, in pairs, stratified by three variables: site, whether or not the participant was prescribed antidepressant medications, and history of injection drug use. The primary outcome was adherence assessed via electronic pill caps (MEMs) with correction for “pocketed” doses. Secondary outcomes included depression, plasma HIV RNA and CD4. Follow-ups occurred at 4, 8 and 12 months. We used intent-to treat analyses with ANCOVA for independent-assessor pre-post assessments of depression and mixed effects modeling for longitudinal assessments. Clinical Trial Registration: NCT00951028, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00951028), closed to new participants.

Findings

The period of recruitment was February 26, 2009 to June 21, 2012, with the 12-month follow-up period extending until April 29, 2013. There were no study-related adverse events. CBT-AD (n=94 randomized, 83 retained) had greater improvements in adherence (Est.=1·00, CI=0·34, 1·66, p=0·003) and depression (CES-D Est.=−0·41, CI=−0·66, −0·16, p=0·001; MADRS Est.=−4·69, CI=−8·09, −1·28, p=0·007; CGI Est.=−0·66, CI=−1·11,-0·21, p=0·005) than ETAU (49 randomized, 46 retained) at post-treatment (4-month). Over follow-ups, CBT-AD (84 retained) maintained higher adherence (Est.=8·93, CI=1·90, 15·97, p=0·013) and lower depression on the CES-D (Est=−3·56, CI=−6·08, −1·05, p=·005) and CGI (Est.=−0·39, CI=−0·77, −0·18, p=·04) than ETAU (86 retained); however, not for the MADRS. There were no significant differences between CBT-AD and ISP-AD (97 randomized, 87 retained) for the post-treatment or follow-up (86 retained) analyses. There were no intervention effects on HIV RNA or CD4, though a higher percentage (91·4%) than expected was virally suppressed at baseline.

Interpretation

Integrating evidenced-based treatment for depression with evidenced-based adherence counseling is helpful for individuals living with HIV/AIDS and depression. Future efforts should examine how to best disseminate of effective psychosocial depression treatments such as CBT-AD to individuals living with HIV/AIDS, as well as examine the cost-effectiveness of such approaches.

Funding

National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH084757) and some author time from NIAID 5P30AI060354, and P30AI042853.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, antiretroviral therapy, ART, adherence, CBT, depression, randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

Depression is an interfering and distressing illness that is highly comorbid with HIV/ AIDS, and is associated with worse adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART),1 and potentially to long-term immune functioning.2,3 It is possible that the significant, but less than optimal effects of existing interventions to promote adherence may be due to the interfering effects of psychosocial problems such as depression.4

Integrating cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for adherence with CBT for depression (CBT-AD) has an emerging evidence base on both adherence and depression outcomes from a small (N=45) randomized controlled crossover trial in people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in HIV care,5 an efficacy trial (N=89) with injection drug use histories in drug abuse treatment,6 a pilot trial on the U.S.-Mexico border,7 and a pilot trial in South Africa.8 These studies generally used an enhanced treatment within the usual control condition and limited follow-up data,5–7 had a within-subjects design, or were initial studies with relatively small samples.8 The present study extends this work, with the primary aim of evaluating CBT-AD in a full-scale efficacy trial of individuals in HIV care across three HIV treatment sites. We employed a three-arm design so that the effects of the specific psychosocial treatment for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) could be compared to a time-matched alternative psychosocial treatment for depression and adherence, i.e., information and supportive psychotherapy with adherence counseling (ISP-AD), as well as to an enhanced treatment as usual with adherence counseling (ETAU). The ETAU condition is included so that the intervention can also be compared to what enhanced standard of care might be able to offer, without an intense and more costly intervention.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Study Design

This was a 12-month, 3-arm randomized controlled efficacy trial. The arms were 1) CBT-AD, 2) ISP-AD and 3) ETAU as described below. Major assessments were conducted at baseline, 4 months (post-treatment / acute outcome, after all of the intervention sessions ended), 8 months, and 12 months. Visits took place at one of three HIV clinics (two hospital-based, one community health center) in New England. All participants completed an informed consent process with a study clinician prior to undergoing any study procedures. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards: Massachusetts General Hospital, Fenway Health, and The Miriam Hospital.

Participants

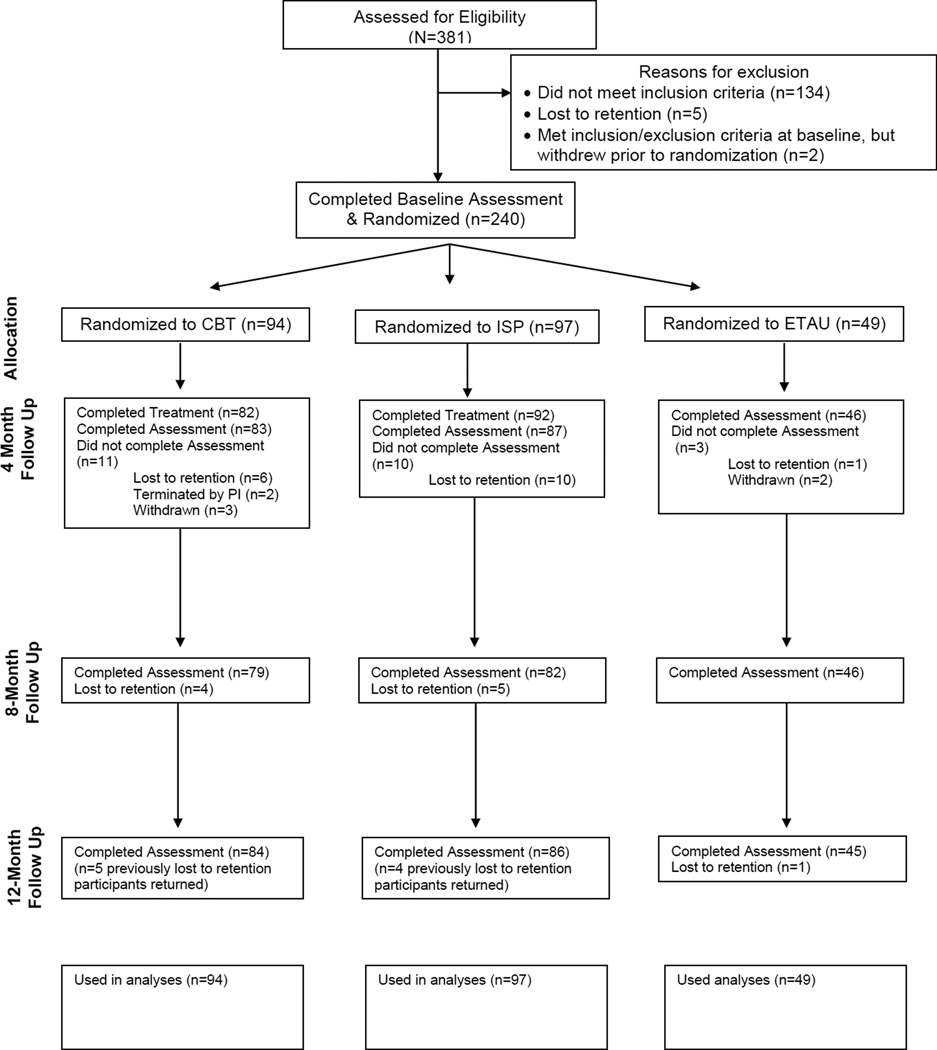

To be eligible, individuals needed to: a) be 18 years of age or older; b) be HIV-positive, c) have been prescribed ART for at least 2 months, and d) have either a current diagnosis of depression (i.e. current major depressive episode) or carry a diagnosis of depression in that they were prescribed an anti-depressant medication for depression and have at least some residual clinically significant depressive symptoms (having met full clinical criteria prior to antidepressant initiation, having a baseline CGI rating of at least 2). Participants were excluded for the following conditions: active, untreated, unstable, major mental illness (i.e., untreated primary psychosis or mania) that would interfere with study participation, any primary psychotic disorder, or a past year history of either CBT or intensive intervention for medication adherence. A total of 381 individuals enrolled in the study, with 7 either lost to retention or withdrawn and 134 excluded prior to randomization per inclusion/exclusion criteria (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram

Note: All randomized participants were included in analyses based on multiple imputation; results were equivalent with and without imputation.

Recruitment was conducted at each of the participating HIV treatment clinics, as well as through community self-referral via advertisements in newspapers and on-line venues. Two of the HIV clinics (MGH and Fenway) also utilized a depressive screening instrument (i.e., PHQ-2)9 with their patients, with scores of 2 or greater indicating possible depression, and therefore an invitation to be contacted to assess interest in participating. Interested participants completed an initial telephone screen, with those potentially eligible scheduled for a full baseline assessment to determine eligibility with a study assessor.

Randomization and masking

Randomization was conducted for 240 adults (94 CBT-AD, 97 ISP-AD, 49 ETAU). The randomization scheme was 2:2:1, such that the CBT-AD and ISP-AD conditions would have twice as many participants as the ETAU condition. We stratified randomization based on three variables which could potentially affect study outcomes so that they were relatively equally distributed across study conditions 1) current or prior problem with injection drug use (because our prior study of those with injection drug use histories had slightly different outcomes in follow-up than our initial trials of patients in HIV care), 2) whether or not participants were prescribed medications for the treatment of their depression, and 3) study site. The randomization sequence was generated by the study data manager using Random Allocation Software,10 that generated block-randomized lists of condition and unique identifier pairs based on parameters provided by the study. Randomization was masked to the interventionists until the end of the first counseling visit (when all participants received the Life-Steps intervention).

Procedures

Participants who completed baseline assessments and were deemed eligible were scheduled for a Life-Steps visit when randomization occurred after completion of the session. Life-Steps involves problem-solving and cognitive behavioral steps to facilitate adherence, as well as provision of tools including programming an electronic device (i.e., study provided watch or participant’s own cell phone) that would sound alarms as a dosing reminder and other reminder techniques.11 For all participants, a provider letter was also mailed documenting results of the baseline psychiatric evaluation and discussing involvement in the study (blinded to randomization status).

All study clinicians (Masters or Doctoral-level psychologists) were trained to administer each of the three conditions and attended weekly clinical supervision where cases were discussed and adherence to condition protocols was reviewed, including via audio review of sessions.

Comparison condition 1: ETAU

All participants had three enhancements to their usual care: 1) a single-session adherence counseling intervention following the Life-Steps,11,12 approach 2) a provider letter sent after the baseline visit and, 3) at follow-up visits, assessors would make referrals for depression treatment if clinically indicated. The Life-Steps approach involves a brief discussion about the patient’s adherence leading up to the visit, beliefs about medications, education about the importance of adherence and how medication resistance can develop, and making a plan and a back-up plan for 11 problem-solving / cognitive-behavioral steps needed for optimal adherence.

Comparison condition 2: ISP-AD

The second comparison condition was designed to examine whether CBT-AD would be different from a time-matched, alternative psychosocial treatment for depression that also integrated Life-Steps for adherence counseling. We chose information with supportive psychotherapy because it can be useful in the management of depression concurrent with medical illness.13 The 11 session ISP-AD manualized intervention developed by our group, with each session lasting up to 60 minutes, included first reviewing the patients’ medication adherence from the time since the last visit, continuing any problem-solving or revisions to the plans via Life-Steps, providing information on healthy living with HIV and then supportive psychotherapy for depression. The goals of supportive psychotherapy were to provide a participant-guided treatment that focused on participants current concerns and aimed to help build self-esteem and enhance adaptive coping using strategies such as normalization, containment and encouragement.14 Informational topics also included nutrition, sleep, and depression in the context of HIV, as well as topics related to managing HIV such as an overview of HIV, managing HIV medication side effects, and the impact of risky behaviors, such as drug use, on adherence.

CBT-AD

The 11-session counseling modules, each lasting up to 60 minutes, included 1) introducing the patient to the nature of CBT and motivational interviewing for behavior change (≈ one session); 2) increasing pleasurable activities and mood monitoring (≈ one session); 3) thought monitoring and cognitive restructuring (i.e., adaptive thinking; ≈ five sessions); 4) problem-solving as a skill to aid in decision-making processes, particularly those related to HIV self-care (≈ two sessions); and 5) relaxation training (≈ two sessions). The therapist and participant were able to structure the number of sessions spent on each module to meet the participants’ individual needs. For all modules participants were encouraged to apply these skills generally (i.e., via the use of home practice), but they were linked to HIV-care whenever possible. For additional details please see the published treatment manuals.15,16

Assessments

At baseline, the MINI17 was used to assess psychiatric diagnoses. All depression assessments were conducted by a study assessor (Masters or Doctoral-level psychologist, clinical social worker) trained via audio-tape supervision in the assessment protocols. An independent assessor (IA), blinded to treatment condition, conducted the interviewer-administered assessments of depression (see below) at the 4-month, 8-month, and 12-month outcome assessments.

Adherence was measured using electronic pill caps (MEMS, AARDEX) as an index of medication adherence following procedures that we have done in our prior trials.5,6 MEMS cap data were read and reviewed at all study visits and allowed for participants to add any doses taken where the participant knew they did not use the cap, and a dose was considered missed if the participant did not take it within two hours of their designated target time. A percentage was calculated via proportion of meds recorded as taken. MEMs caps were given at the baseline assessment, and baseline MEMs scores were calculated at the randomization visit, approximately two weeks later. Follow-up visits used MEMs data for two weeks prior to that visit.

The interviewer-administered MADRS18 and the clinical global impression scale (CGI)19 were used to assess for severity of and distress/impairment due to depressive symptoms at baseline, and months 4, 8, and 12. Ratings were supervised via and audio review by a staff psychologist also blind to treatment condition on a weekly basis. Depression was also assessed via self-report, using the CES-D20 at all study visits, so that we could examine within-treatment gains during the acute treatment period.

At the major study assessment visits (baseline, 4, 8, 12-month) participants provided blood samples for testing HIV plasma RNA (viral load) and CD4+ lymphocyte count (or data were obtained via medical records if available for the prior month).

Outcomes

MEMs-based adherence was the primary outcome (at the four-month assessment), with depression (CESD, MADRS and CGI), HIV RNA (viral load), and CD4 as additional outcomes, and analyses also conducted for follow-ups. As the study was behavioral, we did not formally assess adverse events, however, we would record and report them as they became known to study staff in the context of scheduling, assessment, or counseling.

Statistical Analysis

Power analysis

We powered the study at a 10% difference21,22 in the rate of change in adherence between groups at the acute outcome, expecting both groups to show improvements from baseline. With a two-tailed p-value of 0·05, and assuming a standard deviation in change in adherence outcome of 19% over 4 months, group sample sizes of 80 patients per arm (i.e., the experimental intervention and the time-matched control) would give 90% power to detect a 10% or greater difference in adherence at 4-months in a pair-wise comparison. Additionally, unequal group sample sizes of 80 (CBT-AD and ISP-AD) and 40 (ETAU) would provide at least 88% power to detect a between arm difference of 12% or greater. Given that the ISP-AD arm is more intensive than the E-TAU arm, fewer participants were needed for the comparison to ETAU. Attrition was lower than had been anticipated, and hence the ultimate sample size was greater than 80, 80, and 40, respectively. For viral load, all values less than 75 copies/ml were reclassified as 75 copies/ml. The outcome was then log transformed for continuous analyses as well as categorized as detectable (>75 copies/ml) vs. undetectable (≥75 copies/ml).

Analytic strategy

We conducted two sets of analyses (using SAS 9·3) for each of the two planned comparisons (CBT-AD to ISP-AD, and CBT-AD to ETAU) to correspond to the two study steps: 1) Acute outcome (month 4, when the interventions ended), 2) Follow-up: whether benefits would be maintained post-intervention. Comparing CBT-AD to ISP-AD and to ETAU separately allowed for maximizing power with the 2:2:1 randomization scheme. To fully allow for intent-to-treat principles, we conducted Markov Chain Monte Carlo multiple imputation (with 100 imputations) to provide conservative estimates for missing data. Analyses that did not impute missing values revealed an identical pattern of results. For acute outcomes, missing data was less than 10% across all variables and time points. For follow-up outcomes, missing data was larger (<20%) due to study attrition.

Acute outcome analyses

For the MEMs-based adherence and CES-D scores, which were collected at each study visit (13 assessments for the CBT-AD and ISP-AD arms [randomization visit, 11 treatment visits, 4-month outcome], and 7 assessments for ETAU arm [randomization visit, 6 visits prior to 4-month outcome, 4-month outcome]), mixed effects models with indicators for random intercept and slope were used in order to model the correlation between time points for each participant.23 First, the models contained a term for treatment condition and time. In these models, the parameter estimate for condition refers to the difference in unstandardized units between the two conditions and the parameter estimate for time refers to the change in units from one measurement time point to the next. Second, the mixed effects models included an interaction term. In these analyses, a significant effect for the interaction would indicate superiority of one condition over the other. The parameter estimate for the interaction term specifically indicates the difference in slope for the conditions.

For acute treatment assessments of clinician-administered depression measures (CGI and MADRS) and biological markers of HIV disease (CD4 and viral load), where there were only two assessments (baseline and post-intervention) mixed effects models cannot be used and differences by condition in the post-intervention outcomes were evaluated using ANCOVA, for continuous measures and logistic regression for binary outcomes (detectable versus undetectable viral load) including the baseline value as a covariate. In these analyses the parameter estimates refer to the magnitude of difference in unstandardized units between the two conditions. For each set of analyses, model-adjusted means or proportions and standard errors were estimated and presented.

Follow-up analyses

We evaluated the follow-up data using mixed effects modeling with the 4, 8, and 12 month data for all study outcomes with indicators for random intercept and slope.

These models first contained terms for baseline values, treatment condition, and time. Then, the interaction of time by condition, which measured whether the differences between treatment conditions were maintained over time, was added to each model. Accordingly, during follow-up, a non-statistically significant difference for the interaction term would indicate that the intervention condition maintained its gains over the comparison group, in that any changes post-treatment would be similar across the two conditions. Parameter estimates for main effects and interactions are similar to those for MEMs based adherence and CESD depression scores in the acute outcome analyses.

For each set of analyses, model-adjusted means and standard errors were estimated and presented.

Additional analyses

In addition to these statistical tests, we ran the models using the Wei-Johnson method, a non-parametric test that examines the superiority of one treatment arm over another across time (using all available data) without forcing a parametric form on the overall response over time, due to potential non-normality. This yielded an identical pattern of results, but provided less information because it did not allow for examination or comparison of slopes, just of median differences, and hence we report on the parametric models.

Role of funding source

The study sponsor did not have a role in the design of the study, collection of data, analysis, interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

RESULTS

The period of recruitment was February 26, 2009 to June 21, 2012, with the 12-month follow-up period extending until April 29, 2013. There were 240 patients recruited and intent-to-treat analyses were employed. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the sample at baseline by study condition, with no differences on baseline demographic variables across conditions. Figure 1 presents study flow, including Ns at each assessment visit. All participants in the ETAU condition completed the intervention session, as that was also the randomization visit. In the CBT-AD condition, the mean number of sessions attended was 11·33 (SD=2·12), and in ISP-AD, 11·51 (SD=1·75). There were no study-related adverse events reported.

Table 1.

Demographics and sample characteristics at baseline.

| TAU (n=49) |

CBT (n=94) |

ISP (n=97) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age M (SD) | 47·1 (8·7) | 48·6 (8·0) | 46·5 (8·6) |

| Gender n (%) | |||

| Male | 36 (73·5) | 72 (76·6) | 57 (58·8) |

| Female | 13 (26·5) | 22 (23·4) | 40 (41·2) |

| Race n* | |||

| African American/Black | 14 | 26 | 28 |

| Caucasian/White | 31 | 63 | 62 |

| Other | 7 | 10 | 14 |

| Hispanic/Latino n (%) | |||

| Yes | 7 (14·3) | 7 (7·4) | 12 (12·4) |

| No | 42 (85·7) | 87 (92·6) | 85 (87·6) |

| Education n (%) | |||

| Partial high school or less | 9 (18·4) | 11 (11·7) | 13 (13·4) |

| High school graduate | 12 (24·5) | 25 (26·6) | 28 (28·9) |

| Partial college | 14 (28·6) | 32 (34) | 24 (24·7) |

| College graduate | 14 (28·6) | 26 (27·7) | 32 (33) |

| On Disability n (%) | |||

| Yes | 32 (65·3) | 55 (58·5) | 52 (53·6) |

| No | 17 (34·7) | 39 (41·5) | 45 (46·4) |

| Sexual Orientation n (%) | |||

| Exclusively homosexual | 26 (53·1) | 29 (30·9) | 26 (26·8) |

| Homosexual with some heterosexual experience | 3 (6·1) | 22 (23·4) | 17 (17·5) |

| Bisexual | 2 (4·1) | 4 (4·3) | 8 (8·2) |

| Heterosexual with some homosexual experience | 3 (6·1) | 9 (9·6) | 6 (6·2) |

| Exclusively heterosexual | 15 (30·6) | 30 (31·9) | 40 (41·2) |

| MEMs based adherence | 71.29 (24.43) | 72.33 (22.69) | 71.77 (25.53) |

| Clinical Global Impression (CGI) M (SD) | 4.51 (1.16) | 4.33 (1.26) | 4.67 (1.14) |

| MADRS M (SD) | 24.33 (7.95) | 23.48 (8.04) | 26.86 (8.30) |

| CESD M (SD) | 29.33 (8.36) | 26.31 (6.80) | 27.42 (7.71) |

| CD4 M (SD) | 560.33 (256.88) | 585.44 (284.28) | 578.26 (275.40) |

| Viral Load (log 10) M (SD) | 1.96 (0.26) | 2.14 (0.73) | 1.98 (0.48) |

| Detectable viral load, proportion | .15 | .17 | .11 |

Race category not mutually exclusive, as participants could choose more than one category. Ns for viral load (47, 92, 92), CD4 (48, 91, 92), and MEMs (49, 92, 94) for ETAU, CBT-AD and ISP-AD respectively are lower than the other measures due to issues with lab processing or user/technology issues with starting MEMs.

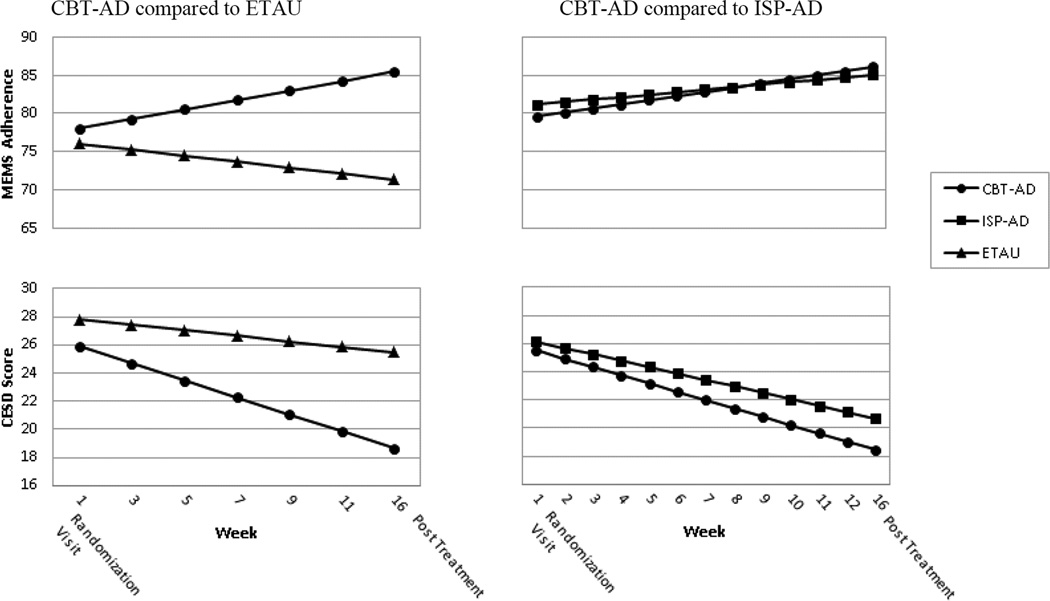

In the reminder of this section, we first depict the findings related to the comparison of CBT-AD to ETAU, starting with the acute (up to month 4) results, and then the follow-up. We then present the findings related to the comparison of CBT-AD to ISP-AD in a similar fashion. For the acute (up to month 4) outcome for MEMs-based adherence comparing CBT to ETAU, mixed effects models did not reveal improvement over time (Est.=0·27, 95% CI=−0·05, 0·60, p=0·10); but did based on study condition (Est.= 7·55, 95% CI=1·42, 13·67, p=0·016). These main effects, however, were qualified by a significant interaction term, indicating that CBT-AD demonstrated an estimated 1·00 percentage point increase in adherence from one assessment visit to the next compared to ETAU over the treatment period (Est.=1·00, 95% CI=0·34, 1·66, p=0·003) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Adjusted acute treatment outcomes by study condition.

Figure notes: MEMS-based adherence and depression (CESD) scores are adjusted through mixed-effects analyses. CBT-AD=cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression; ISP-AD=individualized supportive psychotherapy for adherence and depression; ETAU=enhanced treatment as usual; MEMS=Medication Event Monitoring System; CESD=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Numbers on the X axes denote the week of the visit. Accordingly CBT-AD and ISP-AD 12 visits that were scheduled weekly and ETAU had 6 which were scheduled approximately every other week. The 4-month outcome visit was at approximately 16 weeks.

For depression as assessed on the CES-D, in the comparison of CBT-AD to ETAU, during the acute (up to month 4) outcome period, mixed effects models revealed a main effect for time (Est.=−3·35, 95% CI=−5·66, −1·04, p=0·004), and for condition (Est.=−0·46, 95% CI=−0·59,-0·34, p<0·001). These effects were also qualified by a significant interaction term indicating that CBT-AD demonstrated an estimated 0·41 point greater reduction in the CESD from one assessment visit to the next compared to ETAU over the treatment period (Est.=−0·41, 95% CI=−0·66, −0·16, p=0·001) (see Figure 2).

Regarding clinician-assessed depression comparing CBT-AD to ETAU at the acute (month 4) assessment, controlling baseline, per the ANCOVA analysis, depression severity was approximately 0·66 units lower for CBT-AD compared to ETAU at month 4 for the CGI (Est.=−0·66, 95% CI=−1·11,-0·21, p=0·005) and approximately 4·69 points lower on the MADRS (Est.=−4·69, 95% CI=−8·09,-1·28, p=0·007) (Table 2).

Table 2.

CBT-AD compared to ETAU and ISP-AD: Adjusted acute (month 4) outcome scores by study condition, mean and standard error

| CBT-AD | ETAU | Significance level | CBT-AD | ISP-AD | Significance level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGI | 2·60 (0·13) | 3·26 (0·18) | 0·005 | 2·60 (0·14) | 2·80 (0·13) | 0·308 |

| MADRS | 17·65 (1·03) | 22·33 (1·38) | 0·007 | 18·48 (1·03) | 19·04 (1·00) | 0·698 |

| CD4 | 586·86 (19·68) | 595·55 (26·45) | 0·791 | 593·73 (21·42) | 603·42 (21·21) | 0·748 |

| Viral load (log10) | 1·99 (0·06) | 2·10 (0·08) | 0·288 | 1·98 (0·06) | 2·09 (0·06) | 0·308 |

| Detectable viral load, proportion |

0.17 (0.06) | 0.17 (0.04) | 0·799 | 0.16 (0.04) | 0.20 (0.05) | 0·471 |

Data are mean (SE) for continuous measures and proportion (SE) for binary measures. Scores are adjusted for baseline outcome measures and through the use of ANCOVA (for continuous measures) and logistic regression (for binary measures). CBT-AD=cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression; ETAU=enhanced treatment as usual; ISP-AD=individualized supportive psychotherapy for adherence and depression; CGI=Clinical Global Impression scale; MADRS=Montgomery-Asberger Depression Rating Scale.

At the acute (4-month outcome visit), controlling for baseline, per the ANCOVA analysis, there were no significant differences in log HIV RNA (Est.=−0·11, 95% CI=−0·31,0·09, p=0·288) or CD4 cell count (Est.=−8·69, 95% CI=−73·31,55·92, p=0·791) between CBT-AD and ETAU at (Table 2)‥ Similarly, using logistic regression, there were no differences in detectable viral load (Est.=0·13, 95% CI=−0·91, −1·18, p=0·799) between CBT-AD and ETAU at month 4.

In the follow-up analyses comparing CBT-AD to ETAU, the mixed effects models revealed a significant main effect for condition with CBT-AD maintaining approximately 8·93 percentage points higher adherence than ETAU (Est.=8·93, 95% CI=1·90, 15·97, p=0·013). The main effect for time was also significant (Est.=−4·50, 95% CI=−7·06, 1·94, p=0·0006), indicating that adherence declined on average approximately 4.50 percentage points across conditions after treatment discontinuation at each visit. However, when adding the interaction term, it was not statistically significant (Est.=−4·54, 95% CI=−9·71, 0·62, p=0·09), indicating that the adherence changes in the CBT-AD arm compared to the ETAU arm were not significantly different over follow-up (Table 3).

Table 3.

CBT-AD compared to ETAU and ISP-AD: Adjusted follow-up outcome scores by study condition, mean and standard error

| Month 4 | Month 8 | Month 12 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETAU as the comparison group | ||||||

| CBT-AD | ETAU | CBT-AD | ETAU | CBT-AD | ETAU | |

| MEMS | 81.66 (2.39) | 69.76 (3.17) | 75.61 (2.22) | 68.25 (2.96) | 69.55 (3.04) | 66.73 (4.07) |

| CESD | 20.75 (0.86) | 25.04 (1.16) | 21.41 (0.76) | 24.81 (1.04) | 22.07 (0.94) | 24.59 (1.27) |

| CGI | 2.62 (0.13) | 3.15 (0.18) | 2.67 (0.11) | 3.05 (0.15) | 2.72 (0.14) | 2.94 (0.19) |

| MADRS | 17.90 (1.02) | 21.16 (1.37) | 17.84 (0.88) | 19.78 (1.19) | 17.78 (1.07) | 18.40 (1.46) |

| CD4 | 586.27 (19.39) | 585.49 (26.00) | 593.04 (18.63) | 636.36 (25.15) | 599.80 (28.87) | 687.23 (38.93) |

| Viral load (log10) | 2.00 (0.06) | 2.11 (0.08) | 2.01 (0.04) | 2.08 (0.06) | 2.02 (0.04) | 2.05 (0.06) |

| Detectable viral load, proportion |

0.17 (0.04) | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.18 (0.03) | 0.16 (0.04) | 0.20 (0.05) | 0.15 (0.06) |

| ISP-AD as the comparison group | ||||||

| CBT-AD | ISP-AD | CBT-AD | ISP-AD | CBT-AD | ISP-AD | |

| MEMS | 81.75 (2.17) | 79.09 (2.08) | 75.69 (2.10) | 75.49 (2.08) | 69.63 (3.02) | 71.88 (3.04) |

| CESD | 20.55 (0.89) | 21.17 (0.85) | 21.20 (0.75) | 21.76 (0.73) | 21.86 (0.91) | 22.35 (0.91) |

| CGI | 2.61 (0.14) | 2.81 (0.13) | 2.67 (0.12) | 2.72 (0.12) | 2.72 (0.15) | 2.63 (0.15) |

| MADRS | 18.68 (1.02) | 18.98 (0.98) | 18.62 (0.89) | 17.84 (0.89) | 18.55 (1.12) | 16.70 (1.14) |

| CD4 | 593.09 (20.91) | 597.51 (20.46) | 599.86 (19.15) | 599.16 (18.96) | 606.62 (25.52) | 600.81 (25.32) |

| Viral load (log10) | 1.99 (0.07) | 2.12 (0.07) | 2.00 (0.05) | 2.12 (0.05) | 2.01 (0.05) | 2.11 (0.05) |

| Detectable viral load, proportion (SE) |

0.16 (0.04) | 0.21 (0.04) | 0.18 (0.03) | 0.21 (0.03) | 0.20 (0.05) | 0.22 (0.05) |

Data are mean (SE) for continuous measures and proportion (SE) for binary measures. Scores are adjusted for baseline outcome measures and through the use of mixed-effects analyses

CBT-AD=cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression; ETAU=enhanced treatment as usual; ISP-AD=individualized supportive psychotherapy for adherence and depression; MEMS=Medication Event Monitoring System; CESD=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale; CGI=Clinical Global Impression scale; MADRS=Montgomery-Asberger Depression Rating Scale.

Looking at self-reported depression in the follow-up period comparing CBT-AD to ETAU, mixed effect models revealed a significant main effect for condition such that CBT-AD maintained approximately 3.56 units lower depression scores compared to ETAU during follow-up (Est.=−3·56, 95% CI=−6·08, −1·05, p=0·005). The main effect for time was not significant (Est.=0·35, 95% CI=−0·40, 1·10, p=0·35) indicating that depression did not change after treatment discontinuation. When adding the interaction term into the equation, it was not statistically significant (Est.=0·88, 95% CI=−0·66, 2·43, p=0·26) indicating that any changes in depression over follow-up were not significantly different across the two conditions (Table 3).

Looking at clinician-assessed depression over the follow-up period, also comparing CBT-AD to ETAU, mixed effect models showed, for CGI, a significant main effect for study condition such that CBT-AD maintained approximately 0·39 units lower scores compared to ETAU (Est.=−0·39, 95% CI=−0·77, −0·18, p=0·04). The main effect for time was not significant (Est.=−0·00, 95%=−0·12, 0·12, p=0·996) indicating that CGI-assessed depression did not change after treatment discontinuation. Additionally, the gains in the CGI-assessed depression for CBT-AD compared to ETAU did not significantly change over follow-up, as evidenced by the non-significant interaction term when adding it into the equation (Est.=0·18, 95% CI= −0·10, 0·42, p=0·24) (Table 3).

For MADRS, during the follow-up, comparing CBT-AD to ETAU, there was not a significant main effect for study condition via the mixed effect models, indicating that CBT-AD did not maintain better MADRS-assessed depression scores (Est.=−2·06, 95% CI=−4·96, 0·83, p=0·16). The main effect for time was not significant (Est.=−0·52, 95% CI=−1·41, 0·38, p=0·26), however, indicating that MADRS-assessed depression did not significantly change after treatment discontinuation. Moreover, when adding the interaction term, it was not significant (Est.=1·32, 95% CI= −0·54, 3·17, p=0·16) indicating that any changes were not different by condition over follow-up (Table 3).

For log viral load, the main effects for study condition (Est.=−0·05, 95% CI=−0·18, 0·07, p=0·41), time (Est.=−0·004, 95% CI=−0·06, 0·05, p=0·89) and, when added to the equation, their interaction (Est.=0·04, 95% CI=−0·07, 0·15, p=0·48), were not significant via the mixed effect models comparing CBT-AD to ETAU during the follow-up. Similarly, for detectable viral load, the main effects for study condition (Est.=0·15, 95% CI=−0·57, 0·87, p=0·68), time (Est.=0·06, 95% CI=−0·29, 0·42, p=0·72) and, when added to the equation, their interaction (Est.=0·18, 95% CI=−0·56, 0·92, p=0·64), were not significant via the mixed effect models for CBT-AD compared to ETAU during the follow-up. For CD4, the main effects study condition (Est.=−22·54, 95% CI=−79·25, 34·18, p=0·44), time (Est.=21·88, 95% CI=−3·44, 47·20, p=0·09), and, when added to the equation, their interaction (Est.=−44·10, 95% CI= −96·93, 8·72, p=0·10) were not significant (Table 3) comparing CBT-AD to ETAU during the follow-up period.

Looking at CBT-AD compared to ISP-AD, at the acute outcome assessment, the mixed effects models indicated a significant effect for time (Est.=0·43, 95% CI=0·18, 0·68, p=0·007) suggesting a 0·43 percentage point improvement in adherence from one study visit to the next during the treatment period across both of these treatment conditions. There was not a significant effect for condition (Est.=0·10, 95% CI=−4·19, 4·39, p=0·965) or the interaction (Est.=0·22, 95% CI=−0·28, 0·71, p=0·39) (see Figure 2), indicating that CBT-AD was not superior to ISP-AD on improvements in adherence.

Again, looking at CBT-AD compared to ISP-AD during the treatment period, but for self-reported depression, there was a significant effect for time for the CESD (Est.=−0·52, 95% CI=−0·63, −0·41, p<0·0001) using mixed effects models, indicating that at each study visit, scores in these two conditions improved by approximately 0·52 points from one visit to the next during the treatment period. There was not an effect for condition (Est.=−1·18, 95% CI=−3·00, 0·65, p=0·207) or the interaction (Est.=−0·13, 95% CI=−0·36, 0·09, p=0·25) (see Figure 2), again indicating that CB-AD was not superior to ISP-AD during the treatment period.

For clinician-rated depression at the acute outcome assessment (month 4), after controlling for baseline values using ANCOVA, there were no significant differences in depression between CBT-AD and ISP-AD for either the CGI (Est.=−0·20, 95% CI=−0·58,0·19, p=0·308) or the MADRS (Est.=−0·56, 95% CI=−3·43,2·30, p=0·698) (Table 2), also indicating that CB-AD was not superior to ISP-AD.

With respect to the biological markers at the acute outcome assessment (month 4), for the CBT-AD to ISP-AD comparison, after controlling for baseline values using ANCOVA, there were no significant differences in log viral load (Est.=−0·11, 95% CI=−0·27,0·06, p=0·211) or CD4 cell count (Est.=−9·69, 95% CI=−69·16,49·78, p=0·748) between these two conditions (Table 2). Similarly, using logistic regression, there were no differences in detectable viral load (Est.=−0·31, 95% CI=−1·15, 0·53, p=0·471) between CBT-AD and ISP-AD at month 4 (Table 2).

In the follow-up analyses for the CBT-AD to ISP-AD comparison, mixed effects models revealed that the main effect for study condition was not significant (Est.=1·33, 95% CI=−4·02, 6·68, p=0·63). A significant main effect for time (Est.=−4·81, 95% CI=−6·99, −2·64, p=<0·001) indicated that adherence gains waned by approximately 4·81 percentage points from one visit to the next after treatment discontinuation. When adding the interaction term, it was not significant (Est.=−2·45, 95% CI=−6·86, 1·96, p=0·28), indicating that this reduction did not differ by study condition (Table 3).

For self-reported depression over follow-up, in the comparison of CBT-AD to ISP-AD, mixed effects models revealed that main effects for study condition (Est.=−0·57, 95% CI=−2·62, 1·48, p=0·59), time (Est.=0·62, 95% CI=−0·05, 1·29, p=0·07), and, when added to the equation, their interaction (Est.=0·07, 95% CI=−1·31, 1·45, p=0·92) were not significant (Table 3).

For CGI, using mixed effects models, in the comparison of CBT-AD to ISP-AD, the main effects for study condition (Est.=−0·07, 95% CI=−0·39, 0·25, p=0·67), time (Est.=−0·02, 95% CI=−0·13, 0·09, p=0·73) and, when added to the equation, their interaction (Est.=0·15, 95% CI=−0·08, 0·37, p=0·21) were not significant during the follow-up. Similarly, for MADRS over follow-up, the main effects for study condition (Est.=0·58, 95% CI=−1·88, 3·04, p=0·64), time (Est.=−0·61, 95%= −1·42, 0·20, p=0·14), and, when added to the equation, their interaction (Est.=1·08, 95% CI=−0·56, 2·71, p=0·20) were not significant (Table 3) in the comparison of CBT-AD to ISP-AD. For viral load during follow-up, using mixed effects models, the main effects for study condition (Est.=−0·12, 95% CI=−0·24, 0·004, p=0·06), time (Est.=0·002, 95% CI=−0·05, 0·06, p=0·94), and, when added to the equation, their interaction (Est.=0·02, 95% CI= −0·09, 0·12, p=0·78) were not significant in the comparison of CBT-AD to ISP-AD. Similarly, for detectable viral load over follow-up, the main effects for study condition in the comparison of CBT-AD to ISP-AD (Est.=−0·25, 95% CI=−0·84, 0·32, p=0·38), time (Est.=0·07, 95% CI=−0·23, 0·37, p=0·65) and, when added to the equation, their interaction (Est.=0·12, 95% CI=−0·48, 0·72, p=0·69), were not significant via the mixed effect models. For CD4 over follow-up in the CBT-AD to ISP-AD comparison, there were not significant main effects for treatment condition (Est.=−0·63, 95% CI=−51·79, 50·54, p=0·98), time (Est.=4·17, 95% CI=−13·75, 22·09, p=0·65), or, when added to the equation, their interaction (for CD4: Est.=5·12, 95% CI=−32·14, 42·37, p=0·79) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this paper was that CBT-AD outperformed ETAU on MEMs-based adherence at post-treatment and over follow-up, but did not outperform another (time-matched) treatment for depression integrated with adherence counseling, ISP-AD. Acute (post-treatment) results were also in favor of CBT on depression outcomes compared to ETAU. These depression results were generally maintained over follow-up. Prospective studies of people living with HIV and depression diagnoses that have provided pharmacological treatment for depression without HIV medication adherence counseling have generally found depression but not adherence improvement.24,25 The current results are generally consistent with our prior work integrating adherence counseling with CBT for depression in smaller samples5,7 and persons with injection drug use histories.6 Taken together, the study adds to the evidence that integrating a cognitive-behavioral treatment to promote adherence with treatment for depression (CBT-AD) can be a useful strategy to improve both adherence and depression in persons living with HIV who carry a depression diagnosis.

In the prior study of those with clinical depression and injection drug use histories,6 depression gains were maintained over follow-up but adherence gains were not. In the present study, with a sample of individuals in HIV care regardless of injection drug use history, relative gains in adherence and depression compared to ETAU were generally maintained. However, there was a main effect for the reduction in adherence after the acute outcome. In all of our studies, depression gains were maintained after treatment discontinuation. As we concluded in our study of those with clinical depression and injection drug use histories, it is possible that continued booster sessions to maintain optimal adherence would be necessary in individuals who present at baseline with clinical depression and have initial improvements in both adherence and depression.

CBT-AD, however, was not superior on the outcomes when compared to a time-matched alternative psychosocial treatment for depression that also integrated adherence counseling (ISP-AD). While CBT is the most widely studied psychosocial treatment for depression, there is also evidence that supportive psychotherapy and other structured short-term psychotherapies can also be useful approaches.26 In fact, in one of the original NIMH trials of CBT for depression, interpersonal psychotherapy was originally designed as comparison condition27 and now it is considered a validated treatment.28 Those who were assigned ISP-AD received adherence counseling via the Life-Steps approach in each and every treatment session, and problem-solving and brief cognitive restructuring about pill-taking-- cognitive behavioral techniques – were allowed for regarding adherence goals. Hence, while we may conclude that CBT-AD is better than a less intensive single-session adherence intervention for individuals with HIV and comorbid clinical depression, the results of the current study do not support the specificity of CBT-AD compared to another psychotherapy for depression that takes the same time and integrates active adherence counseling with depression treatment. It may be that integrating Life-Steps, a cognitive behavioral intervention for adherence, with whatever psychotherapy one is receiving for depression, could result in adherence gains that are parallel with depression improvements.

The present study also did not find effects on viral load or CD4. This may be due to the relatively high proportion of participants in the trial who were virally suppressed at baseline, and hence there would be a ceiling effect on improvement. Additionally, the sample size was based on studies of the association of adherence to viral load in samples not selected for depression, and this may have affected the original power analysis. In the past several years, we have seen in the U.S. larger rates of viral suppression in individuals in HIV care, likely due to the increased potency of ART.29 One study of a similar approach employed here, but delivered via computer30 that selected only individuals with detectable viral loads, did find effects on viral load. Accordingly, future studies of this intervention should target subjects who are currently not suppressed or those with recent virologic failure due to non-adherence. CD4 counts, high at baseline, did not significantly improve here, contrary to our prior study of individuals with HIV and a history of injection drug use.6

There are several limitations to note. As described above, the inclusion of persons with suppressed virus at baseline, limited our biological findings. A second limitation is that the MEMS caps, although an objective but imperfect indicator of adherence, could underestimate adherence if participants did not use the cap, or overestimate adherence if participants opened the cap but did not take their pill. Regarding the potential to underestimate adherence, our approach involved querying participants at the visits to learn if they recalled times when they took pills but did not open the bottle.5,6 Additionally, for individuals that were previously using pill-boxes, having to put one medication in the MEMs container could have been disruptive, which could result in the intervention effects being mitigated. All of the sites were medical centers in the Northeast, all of which have services available to enhance adherence as part of standard of care. This may limit generalizability. Treatments were also delivered under the supervision of PhD-level therapists with extensive knowledge of the intervention. This may limit the exportability of the treatment, and hence implementation studies are needed.

This adequately powered trial demonstrated that CBT-AD is a useful approach to improving adherence and decreasing depression in individuals with HIV. Though a brief intervention from the perspective of psychotherapies, it may be considered an intensive intervention when integrated into HIV care settings where patients have limited resources, competing priorities for care, and comorbid conditions. Accordingly, a cost-effectiveness analysis is another important next step in examining the utility of the intervention. Given the high prevalence of depression with HIV, and the demonstrated association of depression with non-adherence, approaches that address both of these problems may help both the quality of life as well as the ability to adhere to self-care regimens for those living with HIV.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Clinical depression is highly prevalent (approximately 37%) in individuals living with HIV, and depression severity is associated to non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy (as documented by a meta-analysis from our group). Cognitive behavioral therapy is a well-studied non-pharmacotherapy treatment for depression. However, there is a general lack of efficacy studies on psychosocial treatments for depression and adherence in individuals living with HIV. We conducted literature review searches at various time points using Pubmed and Psychinfo, searching for terms such as “HIV and depression treatment”, “HIV and CBT”, “HIV and behavior therapy” “HIV and psychological treatment” during the study planning phases, and also kept track of emerging studies as they were available while planning and implementing this trial.

Added value of this study

This study found that for individuals living with HIV who have a clinical diagnosis of depression, 12 sessions of counseling integrating cognitive behavioral therapy for depression with a cognitive behavioral approach to enhancing antiretroviral medication adherence (Life-Steps), was more effective than a single session of adherence counseling and a provider letter documenting one’s depression. These gains were evident at the end of treatment (approximately 4 months), as well as over follow-up (8- and 12-month follow-up). This approach was not superior, however, to another manualized 12-session treatment for depression (information with supportive psychotherapy) that also integrated the same cognitive behavioral approach to adherence counseling. The current findings support the utility of integrating this cognitive-behavioral adherence counseling (Life-Steps) into evidenced-based psychosocial treatments for depression. Accordingly, mental health providers who treat patients living with HIV may wish to integrate this counseling into their treatment in order to improve medication adherence, which may, in turn, improve HIV outcomes.

Implications of all the available evidence

Mental health care providers should consider adding adherence counseling into their psychiatric treatment of patients with HIV who have comorbid depression and poor HIV medication adherence. Policy implications require cost-effectiveness analyses as this study showed that a more intensive treatment for adherence/depression was more effective than a less intensive approach. Implementation and effectiveness trails are also needed.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project came from a National Institute of Mental Health grant R01MH084757 to Dr. Steven A. Safren. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. Some of the author time, and resources for statistical consultation were also supported by grant NIAID 5P30AI060354, and P30AI042853. Clinical Trial Registration: NCT00951028, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00951028).

The study occurred thanks to innumerable contributions, including but not limited to study interventionists, assessors, as well research assistants working on daily study operations, quality assurance, recruitment, and other study coordination tasks. We also thank the Harvard Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) and Heather Ribaudo specifically for statistical consultation. Finally, we thank the contributions of the participants with respect to their time and effort to complete the study assessments and procedures, as well as the Community Advisory Board at Fenway Health who gave input regarding the design and the recruitment of participants.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

Dr. Safren receives royalty statements from Oxford University Press and Guilford Publications, and has a contract with Springer Publications for CBT treatment related material. All other authors have no interests to declare.

Data Safety Monitoring Committee

Anne Eden Evins, Oliver Freudenrich, Joel Pava.

Individual Author Contributions

SAS developed the intervention and oversaw all aspects of the study and manuscript. SAS, CO, MJM, GKR, MDS, KHM designed the study, while CAB, CO, MP, EK directed the study at the respective study sites and contributed to design issues on an as-needed basis. CAB, DSH, JAL, LT, MP, DSH were interventionists and assessors, while CO was the clinical supervisor. JAL conducted data management and KBB, with the help of MJM, statistical analyses. All authors contributed to article content and revisions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS Treatment Nonadherence: A Review and Meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(2) doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822d490a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alciati A, Gallo L, Monforte AD, Brambilla F, Mellado C. Major depression-related immunological changes and combination antiretroviral therapy in HIV-seropositive patients. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2007;22(1):33–40. doi: 10.1002/hup.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Kumar M, Kaplan L, Balbin E, Kelsch CB, et al. Psychosocial and Neurohormonal Predictors of HIV Disease Progression (CD4 Cells and Viral Load): A 4 Year Prospective Study. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(8):1388–1397. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0877-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blashill AJ, Perry N, Safren SA. Mental Health: A Focus on Stress, Coping, and Mental Illness as it Relates to Treatment Retention, Adherence, and Other Health Outcomes. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(4):215–222. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0089-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Tan JY, Raminani SR, Reilly LC, Otto MW, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychol. 2009;28(1):1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0012715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safren SA, O’Cleirigh CM, Bullis JR, Otto MW, Stein MD, Pollack MH. Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected injection drug users: A randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(3):404–415. doi: 10.1037/a0028208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simoni JM, Wiebe JS, Sauceda JA, Huh D, Sanchez G, Longoria V, et al. A Preliminary RCT of CBT-AD for Adherence and Depression Among HIV-Positive Latinos on the U.S.Mexico Border: The Nuevo Día Study. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2816–2829. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0538-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen LS, Leaver M, Kagee A, O’Cleirigh CM, Safren SA, Joska J. Ziphamandla: A study aimes at adapting cognitive-behavioral based intervention for adherence and depression in HIV to the South African context. Oral session presented at: the 7th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence; 2012 Jun; Miami, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saghaei M. Random allocation software for parallel group randomized trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2004;4(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-4-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL. Life-steps: Applying cognitive behavioral therapy to HIV medication adherence. Cogn Behav Pract. 1999;6(4):332–341. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL, Salomon E, Johnson W, Mayer K, et al. Two strategies to increase adherence to HIV antiretroviral medication: life-steps and medication monitoring. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39(10):1151–1162. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simson U, Nawarotzky U, Friese G, Porck W, Schottenfeld-Naor Y, Hahn S, et al. Psychotherapy intervention to reduce depressive symptoms in patients with diabetic foot syndrome. Diabet Med. 2008;25(2):206–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winston A, Rosenthal RN, Pinsker H. Introduction to Supportive Psychotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safren SA, Gonzalez JS, Soroudi N. Coping with chronic illness: Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression, therapist guide. NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Safren SA, Gonzalez JS, Soroudi N. Coping with chronic illness: Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression, client workbook. NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shehann DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett-Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The Development and Validation of a Structured Diagnostic Psychiatric Interview. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134(4):382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute of Mental Health. CGI: Clinical Global Impression Scale - NIMH. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;21:839–844. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Charlebois ED, Clark RA, Robertson M, Zolopa AR, et al. Non-adherence to highly active antiretro-viral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2001;15(9):1181–1183. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200106150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu H, Miller LG, Hays RD, Golin CE, Wu T, Wenger NS, et al. Repeated Measures Longitudinal Analyses of HIV Virologic Response as a Function of Percent Adherence, Dose Timing, Genotypic Sensitivity, and Other Factors. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(3):315–322. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000197071.77482.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pence BW, Gaynes BN, Adams JL, Thielman NM, Heine AD, Mugavero MJ, et al. The effect of antidepressant treatment on HIV and depression outcomes: results from a randomized trial. AIDS. 2015;29(15):1975–1986. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai AC, Karasic DH, Hammer GP, Charlebois ED, Ragland K, Moss AR, et al. Directly observed antidepressant medication treatment and HIV outcomes among homeless and marginally housed HIV-positive adults: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):308–315. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun SR, Gregor B, Tran US. Comparing Bona Fide Psychotherapies of Depression in Adults with Two Meta-Analytical Approaches. In: Davey CG, editor. PLoS ONE. 6. Vol. 8. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weissman MM. A brief history of interpersonal psychotherapy. Psychiatr Ann. 2006;36(8):553. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jakobsen JC, Hansen JL, Simonsen S, Simonsen E, Gluud C. Effects of cognitive therapy versus interpersonal psychotherapy in patients with major depressive disorder: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses. Psychol Med. 2012;42(07):1343–1357. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. [cited 2016 Jan 13];Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services. [Internet] Available from: http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

- 30.Hersch RK, Cook RF, Billings DW, Kaplan S, Murray D, Safren S, et al. Test of a Web-Based Program to Improve Adherence to HIV Medications. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(9):2963–2976. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0535-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]