Abstract

Objective

We conducted a large (N = 216) multisite clinical trial of the Challenging Horizons Program (CHP)—a yearlong after-school program that provides academic and interpersonal skills training for adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses suggest that, as predicted, the CHP resulted in significant reductions in problem behaviors and academic impairment when compared to community care. However, attendance in the CHP ranged from 0 to 60 sessions, raising questions about optimal dosing.

Method

To evaluate the impact of treatment compliance, complier average causal effect (CACE) modeling was used to compare participants who attended 80% or more of sessions to an estimate of outcomes for comparable control participants.

Results

Treatment compliers exhibited medium to large benefits (ds = 0.56 to 2.00) in organization, disruptive behaviors, homework performance, and grades relative to comparable control estimates, with results persisting six months after treatment ended. However, compliance had little impact on social skills.

Conclusions

Students most in need of treatment were most likely to comply, resulting in significant benefits in relation to comparable control participants who experienced deteriorating outcomes over time. Difficulties relating to dose-response estimation and the potentially confounding influence of treatment acceptability, accessibility, and client motivation are discussed.

Keywords: ADHD, training interventions, complier average causal effect (CACE)

Several psychosocial treatments for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are effective at reducing the symptoms and impairments of the disorder, but often require long-term engagement (Evans, Owens, & Bunford, 2014; Sibley et al., 2014). Successful interventions typically involve the manipulation of behavioral contingencies in a target setting (e.g., token systems at home, classroom management), but the benefits do not transfer to other settings or persist once the interventions are discontinued (Chronis et al., 2004). To improve outcomes, researchers have designed training interventions (TIs) to target age-appropriate ADHD coping skills, including organization of school supplies, study skills, and social problem solving (Evans et al., 2014). Unlike traditional clinic-based care, TIs are usually provided in schools over many months or even years, potentially leading to cumulative benefits over time (Evans et al., 2016; Evans, Serpell, Schultz, & Pastor, 2007).

In theory, TIs are well-suited to the neurodevelopmental nature of ADHD because the underlying deficits are typically performance-based rather than skill-based. Children with ADHD can often identify appropriate skills when discussing academic and social problems dispassionately, but are unable to enact those skills in real-time (Wheeler & Carlson, 1994). TIs provide ample time to practice new skills to the point of mastery (i.e., automaticity), thereby overcoming performance-related deficits. In this way, some of the complicating features of ADHD—namely, the tendency for children with ADHD to overestimate their social abilities (i.e., positive illusory bias; Owens et al., 2007) and for peers to maintain negative impressions (Hoza et al., 2005)—may be addressed.

The Challenging Horizons Program (CHP) is a set of school-based TIs for middle school students with ADHD that has been evaluated as an after-school program (Evans, Schultz, DeMars & Davis, 2011), a mentoring program (Evans et al., 2007), and most recently in a randomized trial comparing both versions to community care (Evans et al., 2016). In the after-school version of the CHP (hereafter, CHP-AS), students attend the program 2 days per week, for more than 2 hours per session, from September through May (i.e., one school year). Although this model offers a high dose of treatment, the demands placed on the young adolescents and their families result in varying degrees of attendance.

Assessing Treatment Compliance

Randomized trials address vital treatment development questions, but researchers most often examine the overall effect of an intervention based on original group assignment. Such intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses ignore unanticipated changes following randomization (e.g., early dropout, complementary treatments) and provide researchers with a conservative estimate of treatment effect that is averaged across all actual doses (Lochman et al., 2006). ITT analyses ostensibly reflect the real-world treatment deviations common in school and clinical settings, thereby providing an estimate of community impact (Jo, 2002); however, ITT results do not address questions regarding treatment compliance. Although community impact is critical to evaluate, it is equally important to determine whether compliance leads to the benefits that treatment developers anticipate. If so, interventionists might target treatments to likely compliers, or modify treatments to maximize availability and engagement. In the case of TIs for ADHD, a compliance benefit would suggest that long-term engagement leads to mastery of the targeted skills as intended. Moreover, a lasting compliance benefit would suggest that compliers are able to generalize those skills beyond the treatment setting.

The simplest approach to estimating a compliance effect is to compare compliers in a treatment group against a control group, but treatment compliers represent an unusual subset of participants who, by definition, are more motivated than their peers. By limiting the analysis in this way, the benefit of pretreatment randomization is lost and researchers cannot safely conclude causality (Lochman et al., 2006). Another option is to assess dose-response relationships, but these analyses are notoriously ambiguous in psychotherapy trials. In some studies participants increasingly benefit as sessions progress, as expected (e.g., Kopta et al., 1994), but often the relationship is inconclusive. One reason is that higher-functioning participants can reach their goals early and choose to discontinue treatment, while participants with greater need persist in treatment but make relatively smaller gains. Such trends can wash out the dose-response effect (Salzer, Bickman, & Lambert, 1999). In our work on the CHP-AS, we found that higher rates of attendance were rarely associated with improved outcomes (Langberg, Evans, Becker, Altaye, & Girio-Herrera, 2016), consistent with the wash-out hypothesis. Thus, treatment compliance in randomized trials is confounded with participant factors that cannot be adequately controlled through research design alone. Researchers must employ statistical models that account for the complications created by the voluntary nature of compliance.

Complier Average Causal Effect

Complier average causal effect (CACE) models estimate causal effects in the presence of treatment noncompliance. In instances where dosage is vital, such as treatments that require a minimum number of sessions, CACE models provide a fair comparison between compliers in the treatment group and similar individuals in the control group who most likely would have complied had treatment been offered. CACE models can be fit in many frameworks (e.g. instrumental variables, Bayesian) (Jo, 2002), but when fit as mixture models, treatment compliance within the control group is estimated as a categorical latent variable. When all participants in the treatment group comply, CACE and ITT analyses provide the same estimates of treatment effect; but, in the presence of noncompliance, CACE models estimate outcomes specific to compliers.

To avoid biased estimates, CACE models are premised on several statistical assumptions: (a) some proportion of participants comply with treatment; (b) there is an equal proportion of would-be compliers in a comparable control condition (i.e., random assignment); (c) outcomes for each participant is independent of outcomes for all other participants (i.e., Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption [SUTVA]); (d) the impact of treatment is never in the unintended direction (e.g., no treatment defiers); and (e) non-compliers do not benefit from the treatment (Connell, 2009; Muthén & Muthén, 2014). The last assumption is referred to as the exclusion restriction assumption and it is likely to be violated in psychotherapy trials because partial-compliers conceivably derive some benefit. Fortunately, the limits imposed when this assumption is violated can be relaxed by including pretreatment predictors of compliance in the model (Huang et al., 2014), which has the added benefit of improving statistical power in some instances (Jo, 2002).

The Present Study

We recently completed a large RCT designed to address two sets of treatment questions regarding the CHP-AS when compared to community care. The first involved the effects of treatment independent of participant engagement (ITT), and those results were previously reported (Evans et al., 2016). The second set of questions involved an examination of the benefit of treatment for those participants who attended over 80% of the CHP-AS activities. Long-term treatments like the CHP-AS place burdens on participants and their families, leading to inconsistent engagement and premature dropout. In comparison to less intensive delivery models and community care, we noted that the CHP-AS resulted in significantly higher rates of attrition (Evans et al., 2016). As a result, session attendance varied considerably. In the present study, we recreate our previous ITT analysis and then evaluate outcomes for treatment compliers using CACE modelling for comparison purposes. Our aim is twofold: First, we assess the degree to which compliers exhibit a distinct compliance benefit at the end of treatment. Second, we assess the degree to which the compliance benefit persists six months after treatment ends.

Method

Participants

Participants in the present study were 216 public middle school students who enrolled in the CHP multisite study and were randomly assigned to either the CHP-AS (N = 112) or a community care control group (N = 104). No significant differences were noted between the groups on any of the intake variables assessed, suggesting that the randomization procedures were successful (see Table 1).1 Consistent with the literature on ADHD, boys outnumbered girls in our sample at a ratio of nearly 3:1 (Willcutt, 2012). Our sample also appeared representative of rural and suburban Midwest populations in terms of race, ethnicity, and family income.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics by Treatment Group

| After-School (N = 112) |

Community Care (N = 104) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Boys | 79 | 70.5 | 77 | 74.0 |

| Grade | ||||

| 6 | 43 | 38.4 | 43 | 41.3 |

| 7 | 42 | 37.5 | 31 | 29.8 |

| 8 | 27 | 24.1 | 30 | 28.8 |

| Race/Ethnicitya | ||||

| African American | 8 | 7.1 | 15 | 14.4 |

| White | 83 | 74.1 | 83 | 79.8 |

| Biracial | 16 | 14.3 | 5 | 4.8 |

| Other | 5 | 4.5 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Hispanic | 3 | 2.7 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Family Status | ||||

| Two parents | 53 | 47.3 | 38 | 36.5 |

| Single/Blended | 46 | 41.1 | 49 | 47.1 |

| Other | 13 | 11.6 | 17 | 16.3 |

| Med Usage | 49 | 43.8 | 47 | 45.4 |

| ADHD-C | 55 | 49.1 | 49 | 47.1 |

| IEP/504 Plan | 41 | 36.6 | 32 | 30.1 |

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Household Incomec | 56.5 | 45.2 | 63.5 | 55.5 |

| Mother’s Educationd | 14.1 | 2.2 | 14.0 | 2.3 |

| Child FSIQe | 100.3 | 14.2 | 101.4 | 13.7 |

| Child Achievementf | ||||

| Basic Reading | 94.8 | 15.1 | 96.5 | 14.5 |

| Mathematics | 91.5 | 15.4 | 93.1 | 15.8 |

| Written Exp. | 95.6 | 13.7 | 97.3 | 14.3 |

| Previous GPAg | 2.2 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 0.9 |

| Child Age | 12.1 | 0.9 | 12.2 | 1.0 |

| CP Symptoms | ||||

| ODD | 4.5 | 2.3 | 4.4 | 2.2 |

| CD | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.4 |

Note. No significant differences were noted on any pre-treatment variables. ADHD-C = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Combined Subtype (all other cases were Predominately Inattentive); IEP = Individual Education Plan (Special Education); CP = conduct problems; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; CD = conduct disorder. Names of the covariates in the ITT and CACE models are italicized.

Race/ethnicity figures do not sum to 100% because ethnicity (Hispanic) was asked separate from race.

Met criteria for any anxiety disorder or depressive disorder on child self-report semi-structured diagnostic interview.

Reported in thousands.

Reported in grade equivalents.

Based on the highest 2, 3, or 4 subtest short-form of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (Wechsler, 2003).

Based on selected cluster scores of the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Second Edition (Wechsler, 2009).

Based on a 4-point scale (0.0 – 4.0)

Procedures

The Institutional Review Boards at Ohio University and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center approved all procedures. Participants were recruited from nine Midwestern public middle schools over three consecutive school years using a multiwave cohort design. Legal guardians who responded to a direct mailing and passed an initial phone screen were scheduled for university-based intake evaluations during spring and summer months. To be eligible for participation, adolescents needed to (a) meet DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for any subtype of ADHD (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000); (b) not meet diagnostic criteria for autistic spectrum, bipolar, psychosis or obsessive-compulsive disorders; (c) demonstrate clear impairments in academic and/or social domains; and (d) demonstrate an IQ of 80 or above as estimated using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Fourth Edition (WISC-IV; Wechsler, 2003). The first two criteria were assessed through diagnostic interviews with parents (Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes, Parent Version; Weller, Weller, Fristad, Rooney, & Schecter, 2000) or combined with teacher ratings on the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale (DBD; Van Eck, Finney, & Evans, 2010); the third criterion was assessed based on parent or teacher report on the Impairment Rating Scale (IRS; scores >3 constitute impairment; Fabiano et al., 2006). Two doctoral-level clinicians reviewed these data during consensus eligibility determinations at each participating site. Individuals deemed eligible for participation were randomly assigned to an experimental condition prior to the start of the school year, stratified by medication status at intake (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participant recruitment and assignment

a Exclusion decisions were made based on the following: Low FSIQ = 5; impairments caused by another disorder (e.g., OCD) = 9; insufficient ADHD symptoms = 5; impairments inconsistent with ADHD or ADHD treatment = 20; overlap with other services = 3; failed to recruit sufficient participants at a prospective school site = 4

b Participants assigned to a third treatment (“mentoring”) are not included in the present study (see Evans et al., 2016 for details)

c Did not attend any CHP-AS sessions: Child not interested = 1; family crisis = 1; online school = 1; moved = 3; study withdraw = 1

d There were 4 study withdrawals overall: One child passed away; one participant’s parent passed away; two were no longer interested in participating and requested no further contact

After-school program (CHP-AS)

Participants assigned to the CHP-AS program met two days per week for 2-hours, 15-minutes at their respective schools for one school year. Trained undergraduate students, advanced graduate students, and doctoral-level researchers travelled to the schools to staff the program. The CHP-AS interventions target the academic enablers often lacking among students with ADHD, including organization, study skills, assignment tracking, and social problem solving (see Schultz & Evans, 2015). Interventions targeting academic and social impairment were primarily provided in small groups, although each participant had a primary counselor who met with them one-to-one every session to help set goals and track progress.

All staff members in the present study were required to read the 203-page CHP-AS treatment manual and pass competency exams at or above 95% accuracy during an 8-hour preservice training. Throughout the school year, the implementation teams met weekly to problem-solve concerns, under the guidance of the principal investigators (second and third authors). In addition, program adherence was rated by independent observers and feedback was periodically provided to the team to ensure timely corrections.

Community care (CC)

Participants assigned to the CC condition received services indigenous to their schools and communities, with some assistance in the form of resource lists prepared by the research team. Upon request, summaries of the intake assessment results were also prepared for parents to present to school and community provides, but otherwise no novel services were provided. We previously noted that roughly 45% of both conditions received ADHD medications at intake and planned to continue those medications during the study (Evans et al., 2016). We also found that 30.1% of the CC group received special education services or a 504 plan (see Spiel, Evans, & Langberg, 2014 for details), which is roughly equivalent to rates noted in the CHP-AS (refer to Table 1).

Measures

To assess outcomes, we examined parent behavior ratings and report card grades over time. Parent behavior ratings were collected at up to six measurement occasions, including intake (described above), early in the school year (October/November), second-quarter (January/February), third-quarter (March/April), end-of-treatment (May/June), and then at a follow-up session 6-months after treatment ended (November). Grades were collected at four grading periods in each of the treatment year and post-treatment year, but only end-of-year final grades were collected for the pretreatment year.

Children’s Organizational Skills Scale (COSS; Abikoff & Gallagher, 2009)

The COSS is a parent rating scale that assesses child organization relevant to home and school settings. The COSS consists of 58 items, each using a Likert-type response format ranging from 1 (Hardly ever or never) to 4 (Just about all of the time). We examined the results of three subscales of the COSS, including Materials Management (α = .82), Task Planning (α = .81), and Organized Actions (α = .64). The internal reliability of the latter scale appeared low, but we noted that one specific item appeared to compromise the estimate. Without this one item the internal reliability appeared acceptable (α = .82), so we chose not to adjust the scale in our analyses. We collected the COSS at all six measurement occasions except for early in the school year (an effort to reduce the assessment burden on parents at that time point).

Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale (DBD; Pelham, Evans, Gnagy, & Greenslade, 1992)

The DBD is a 45-item parent rating scale that assesses symptoms of disruptive behavior disorders. Each item of the DBD utilizes a Likert-type response format ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Very much). The DBD was updated to reflect the relevant symptom descriptions provided in the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000), and research on this version has found a DSM-consistent factor structure when used with parents of middle school students (Van Eck et al., 2010). For the present study, we focused on two DBD subscales measuring the inattentive (α = .88) and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms (α = .89) of ADHD. We collected the DBD at all six measurement occasions.

Grades

To assess academic performance, we examined report card data for four core courses: Language Arts, Math, Social Studies, and Science. All letter-grades were converted to four-point scales, ranging from A = 4.0 to F = 0.0, to ensure consistency across schools. Although grades are subject to situational factors (e.g., classroom accommodations), these data offer a proxy measure of school performance with ecological validity. As mentioned previously, grades were collected quarterly based on the school calendar.

Homework Problems Checklist (HPC; Anesko, Schoiock, Ramirez, & Levine, 1987)

The HPC measures parent perception of child performance on homework and consists of 20 items, each using a Likert-type response format ranging from 1 (Never) to 4 (Very Often). Factor analysis of the HPC results in a reliable two-factor solution (Langberg et al., 2010; Power et al., 2006). The first factor is related to inattention and avoidance of homework (Factor 1; α = .91), and the second factor is related to poor productivity and rule-breaking behavior during homework (Factor 2; α = .88). We collected the HPC at all six measurement occasions.

Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS; Gresham & Elliott, 2008)

The SSIS is a set of rating scales that measure social skills, problem behaviors, and academic competencies. Psychometric data provided in the SSIS examiner’s manual and subsequent research reveal acceptable validity, reliability, and internal consistency (Gresham et al., 2011). Given that items relating to problem behaviors and school-related issues overlapped our other measures, we focused our present analysis on the seven subscales of the parent-report SSIS relating to prosocial skills, including Communication (α = .72), Cooperation (α = .81), Assertion (α = .68), Responsibility (α = .84), Empathy (α = .90), Engagement (α = .79), and Self-Control (α = .83). These subscales are comprised of 46 total items that use two Likert-type response formats. The first response format measures frequency of behaviors on a 4-point scale ranging from N (Never) to A (Almost Always), and the second measures the importance of each behavior on a 3-point scale ranging from N (Not important) to C (Critical). Given the length of the SSIS, we administered it only three times (intake, end-of-treatment, and follow-up).

Analytic Strategy

Defining compliance

We defined compliance as 80% or greater attendance in the CHP-AS for two reasons. First, the CHP-AS treatment manual outlines TIs that theoretically require extensive practice with monitoring and performance feedback. After mastery, students progressively apply the new skills to situations outside of the program. For this reason, we asked participating families to commit to at least 80% of the total number of sessions offered to ensure ample time to progress through all phases of the curriculum. Second, attendance at 80% or more sessions ensured that participants had an opportunity to practice the skills in all four grading periods at the participating schools. In previous research, we found that the risk of academic failure varied across grading periods, with the highest risk occurring near the beginning and end of the school year (Schultz, Evans, & Serpell, 2009). The 80% attendance criterion ensures that completers were coached to apply the skills to some degree in all grading periods. Based on this criterion, 46 CHP-AS participants (41%) complied with the treatment as intended.

Statistical modelling

All analyses were conducted with Mplus v. 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2014). For each outcome, results were fit with both CACE and ITT2 models. CACE methods model compliance and non-compliance in the control group as a latent variable, but only effects for compliers are reported (treatment effects for non-compliers were fixed to zero to meet the exclusion restriction assumption).

Treatment effects were estimated by regressing outcomes on a binary predictor representing treatment (0 = CC; 1 = CHP-AS). For the DBD, HPC, grades, and COSS, effects of treatment at baseline and end-of-treatment were assessed using growth curve models with end-of-treatment represented as the intercept in the model. This was accomplished by changing the coding of time such that end-of treatment was represented by time 0; for example, time in the DBD was coded as −4, −3, −2, −1, and 0. Changing the coding of time in this way affects estimates of the intercept, but it does not influence estimates of the linear or quadratic slope, nor does it influence model fit (Little, 2013). The intercept was then regressed onto the treatment variable for an estimate of treatment effects (see Figure 2A). The COSS was measured on four occasions from intake to end-of-treatment and was modeled in a similar manner, but with a linear trend (see Figure 2B). The SSIS was collected less often (baseline, end-of-treatment, and follow-up), so these outcomes were modelled using a residual difference score approach. The residual difference score approach provides an estimate of change from baseline (Little, 2013) and was assessed by regressing end-of-treatment scores onto baseline scores and the treatment variables. We used this same approach to model all treatment effects at the six month follow-up because doing so avoided the assumption that change from baseline to follow-up is a monotonic function (see Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Complier average causal effect models

We examined the possibility that the SUTVA assumption of CACE modelling was violated because the CHP-AS is a group-based intervention. Outcomes for individuals within group settings are clearly impacted by the outcomes from other individuals in the same group. However, we assume SUTVA because each adolescent worked on individual goals in one-to-one sessions with a primary counselor that were evaluated (and rewarded) separately from the performance of other participants. Additionally, the outcomes we examine in the present study are based on parent report, and those impressions were formed entirely outside of the group. Still, all analyses were run with cluster robust standard errors to address the possibility of SUTVA violation.

The design of the CHP study also brings the exclusion restriction assumption into question because it seems unlikely that participants receiving less than 80% of the treatment would not benefit at all. However, the bias introduced when this assumption is violated can be relaxed by the inclusion of covariates that predict compliance. Dozens of potential predictors were available for consideration, so we selected variables supported by theory and previous research. Healthcare research (e.g., Haboush-Deloye et al., 2014) shows that family income is an important determinant of treatment access, and indeed family income was significantly different for compliers and noncompliers in the CHP-AS in the anticipated direction (t = 2.38; p = .02). We also selected well-established predictors of school success, including FSIQ (t = 2.06; p = .04) and academic performance in the previous school year (t = 2.29; p = .02). Finally, we included conduct disorder symptoms based on our hypothesis that adolescents with severe conduct problems would disproportionately refuse treatment. Although differences between compliers and noncompliers were inconclusive on this covariate (t = −1.82, p = .07), we included it in our models to adjust for one of the most common and complicating comorbidities with ADHD. No other candidate predictors were supported by previous research, nor was there sufficient theoretical justification to include more.3

Results

To address our hypothesis that participants with less need for treatment attend at lower rates than needier peers, we estimated both ITT and CACE models. Model fit statistics for ITT models of the treatment year were acceptable (RMSEA .017 - .121, CFI .848 - .999), but could not be estimated when models were saturated, as was the case for follow-up year analyses (residual difference score models). The mixture models used to estimate CACE do not provide comparable fit statistics; however, the entropy index offers an estimate of classification quality, with scores approaching 1.0 suggesting ideal classification. Thus, entropy can be considered a measure of the confidence in the descriptive statistics for the CACE control group. Summary statistics from the ITT and CACE analyses are provided in Table 2. The entropy estimates for the CACE models ranged from 0.55 to 0.79, which is acceptable given the confirmatory nature of our aims (cf. Dishion, Brennan, Shaw, McEachern, Wilson, & Jo, 2014), but indicates that the summary statistics in Table 2 may deviate from the model results due to classification and model error. As a result, these estimates should be interpreted with caution. Model results are summarized in Table 3 and described below.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for ITT and CACE Models at Intake, End-of-treatment, and Follow-up

| Intake (Baseline) |

End-of-Treatment |

Six Month Follow-up |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITT-T | ITT-C | CACE-T | CACE-C | ITT-T | ITT-C | CACE-T | CACE-C | ITT-T | ITT-C | CACE-T | CACE-C | ||

| CACE Entropy† |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

|

| COSS | |||||||||||||

| Total | .60/.62 |

68.9 (9.3) |

66.4 (8.2) |

69.5 (9.7) |

69.5 (8.6) |

61.4 (11.1) |

65.2 (9.6) |

62.0 (11.0) |

71.4 (8.4) |

58.9 (11.4) |

62.3 (11.3) |

58.8 (12.7) |

72.9 (8.0) |

| Memory & Materials | .67/.63 |

67.6 (11.9) |

65.5 (12.0) |

67.8 (12.0) |

73.1 (12.6) |

59.5 (12.7) |

63.7 (12.5) |

61.0 (13.1) |

73.9 (10.7) |

56.7 (12.7) |

62.0 (12.0) |

56.4 (14.1) |

74.4 (8.0) |

| Organized Actions | .63/.63 |

62.3 (5.4) |

61.2 (5.4) |

62.9 (5.0) |

65.2 (3.5) |

58.7 (8.0) |

61.0 (6.2) |

60.4 (8.8) |

64.9 (4.5) |

57.7 (8.2) |

59.7 (7.7) |

58.4 (8.9) |

65.5 (4.4) |

| Task Planning | .61/.61 |

67.8 (12.7) |

63.0 (11.1) |

68.5 (12.4) |

65.8 (10.8) |

58.5 (12.3) |

61.5 (12.5) |

57.6 (10.7) |

66.8 (11.1) |

54.6 (12.3) |

58.5 (13.7) |

53.5 (12.6) |

72.9 (10.0) |

| DBD | |||||||||||||

| Inattention | .79/.63 |

18.8 (5.8) |

18.2 (5.6) |

18.8 (5.2) |

19.3 (4.9) |

11.1 (6.6) |

13.2 (7.6) |

11.3 (6.9) |

18.6 (5.1) |

10.7 (6.9) |

13.2 (7.0) |

10.5 (7.0) |

19.0 (4.6) |

| Hyper/Imp | .72/.65 |

14.8 (6.6) |

14.2 (6.3) |

14.3 (7.0) |

17.7 (5.6) |

10.6 (6.6) |

11.4 (6.8) |

10.5 (7.0) |

15.8 (6.2) |

8.9 (7.0) |

10.6 (7.4) |

9.1 (7.4) |

17.4 (6.2) |

| Grades | .73/.67 |

2.4 (0.9) |

2.3 (0.9) |

2.2 (0.9) |

1.6 (0.7) |

2.4 (1.0) |

2.3 (1.0) |

2.1 (1.0) |

1.6 (0.7) |

2.3 (1.0) |

2.2 (0.9) |

2.2 (1.1) |

1.5 (0.7) |

| HPC | |||||||||||||

| Factor 1 | .72/.67 |

34.4 (7.8) |

33.4 (7.4) |

35.0 (7.0) |

35.9 (5.9) |

26.3 (8.1) |

29.2 (8.6) |

27.9 (8.5) |

36.5 (4.9) |

22.1 (8.3) |

27.2 (8.9) |

20.5 (7.5) |

35.0 (4.9) |

| Factor 2 | .68/.65 |

16.5 (4.7) |

16.2 (4.4) |

17.1 (4.4) |

17.4 (4.2) |

12.5 (4.5) |

14.8 (4.5) |

13.9 (4.9) |

18.0 (3.2) |

11.8 (4.7) |

14.1 (5.2) |

11.2 (4.6) |

19.2 (3.7) |

| SSIS | |||||||||||||

| Communication | .58/.56 |

13.4 (3.5) |

13.4 (3.4) |

13.5 (3.5) |

12.8 (3.8) |

13.7 (3.7) |

14.2 (3.3) |

13.7 (4.2) |

14.6 (3.9) |

13.8 (4.3) |

14.0 (3.0) |

13.8 (4.4) |

13.7 (3.1) |

| Cooperation | .57/.55 |

9.2 (2.9) |

9.7 (2.8) |

9.1 (2.8) |

9.0 (3.0) |

10.6 (3.5) |

10.5 (3.2) |

10.3 (3.6) |

9.3 (3.4) |

11.3 (3.7) |

10.6 (3.0) |

11.1 (3.8) |

9.4 (2.9) |

| Assertion | .59/.55 |

12.6 (3.5) |

12.7 (3.3) |

12.9 (3.5) |

11.8 (3.3) |

12.9 (3.2) |

13.1 (3.1) |

12.9 (3.4) |

13.7 (3.6) |

12.4 (3.5) |

13.2 (3.1) |

12.7 (3.2) |

12.8 (2.2) |

| Responsibility | .59/.57 |

9.5 (3.6) |

10.1 (3.3) |

9.5 (3.6) |

9.5 (3.3) |

11.0 (3.5) |

10.6 (3.4) |

10.6 (3.6) |

8.9 (3.5) |

11.2 (4.3) |

11.1 (3.4) |

11.0 (4.5) |

9.9 (2.9) |

| Empathy | .59/.58 |

10.9 (3.9) |

11.2 (3.8) |

11.5 (3.9) |

11.3 (3.9) |

10.9 (3.7) |

11.6 (3.7) |

11.2 (3.5) |

12.4 (3.6) |

11.4 (4.0) |

11.7 (3.7) |

12.1 (3.9) |

12.9 (2.7) |

| Engagement | .60/.56 |

12.1 (4.2) |

12.3 (3.7) |

12.6 (4.1) |

12.8 (3.3) |

12.9 (4.0) |

12.8 (3.7) |

13.0 (3.5) |

14.3 (2.5) |

12.0 (4.2) |

12.4 (3.8) |

12.9 (3.6) |

13.3 (2.7) |

| Self-Control | .57/.59 |

8.1 (3.7) |

9.3 (3.5) |

7.3 (3.9) |

8.4 (3.6) |

9.6 (4.2) |

10.4 (3.8) |

9.3 (4.0) |

10.3 (3.4) |

10.4 (4.3) |

10.3 (3.9) |

9.4 (4.3) |

7.5 (3.1) |

Note. ITT-T = Intent-to-treat treatment group; ITT-C = Intent-to-treat control group; CACE-T = Complier average causal effect estimate of treatment compliers; CACE-C = Complier average causal effect estimate of would-be compliers in the control condition; all estimates should be interpreted with caution

Entropy estimates are provided for end-of-treatment and six-month follow-up models respectively

Table 3.

Results from ITT and CACE Analyses Comparing Treatment versus Control at End-of-Treatment and Six Month Follow-up

| End-of-Treatment |

Six Month Follow-up† |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITT |

CACE |

ITT |

CACE |

|||||||||

| Measure/Subscale | B | (SE) | d | B | (SE) | d | B | (SE) | d | B | (SE) | d |

| COSS | ||||||||||||

| Total | 3.79 | (1.56) | 0.39 | 7.17 | (2.25) | 0.71 | 5.75 | (2.04) | 0.63 | 11.21 | (3.36) | 1.15 |

| Memory & Materials | 4.36 | (1.36) | 0.36 | 9.76 | (2.53) | 0.79 | 6.84 | (2.45) | 0.66 | 12.28 | (4.59) | 1.13 |

| Organized Actions | 2.86 | (1.47) | 0.47 | 3.84 | (1.72) | 0.61 | 2.18 | (1.32) | 0.36 | 4.68 | (1.82) | 0.79 |

| Task Planning | 3.30 | (1.30) | 0.30 | 9.14 | (2.28) | 0.93 | 6.48 | (2.18) | 0.58 | 14.61 | (4.12) | 1.24 |

| DBD | ||||||||||||

| Inattention | 2.28 | (1.09) | 0.45 | 6.99 | (2.16) | 2.00 | 2.94 | (0.94) | 0.45 | 6.51 | (1.93) | 0.99 |

| Hyper/Imp | 0.75 | (0.61) | 0.12 | 5.31 | (1.23) | 0.94 | 2.19 | (0.85) | 0.35 | 5.67 | (1.57) | 0.92 |

| Grades | 0.14 | (0.18) | 0.16 | 0.46 | (0.25) | 0.61 | 0.27 | (0.16) | 0.25 | 0.86 | (0.26) | 0.83 |

| HPC | ||||||||||||

| Factor 1 | 2.58 | (0.81) | 0.33 | 7.07 | (1.21) | 1.16 | 5.69 | (1.47) | 0.76 | 12.33 | (1.95) | 1.90 |

| Factor 2 | 2.20 | (0.59) | 0.51 | 3.42 | (0.83) | 0.86 | 2.43 | (0.88) | 0.54 | 5.85 | (1.51) | 1.32 |

| SSIS | ||||||||||||

| Communication | 0.45 | (0.48) | 0.15 | 1.05 | (0.62) | 0.37 | 0.15 | (0.86) | 0.05 | 0.13 | (0.76) | 0.05 |

| Cooperation | 0.34 | (0.22) | 0.13 | 0.55 | (0.90) | 0.21 | 0.91 | (0.52) | 0.36 | 1.34 | (0.78) | 0.55 |

| Assertion | 0.28 | (0.45) | 0.11 | 1.00 | (1.02) | 0.37 | 0.51 | (0.49) | 0.17 | 0.33 | (1.15) | 0.14 |

| Responsibility | 0.64 | (0.36) | 0.24 | 1.30 | (0.40) | 0.56 | 0.50 | (0.57) | 0.16 | 0.95 | (0.91) | 0.36 |

| Empathy | 0.39 | (0.34) | 0.15 | 1.03 | (0.79) | 0.37 | −0.02 | (0.61) | 0.01 | 0.08 | (1.12) | 0.03 |

| Engagement | 0.32 | (0.60) | 0.11 | 0.69 | (1.01) | 0.31 | 0.12 | (0.69) | 0.04 | 0.11 | (1.41) | 0.04 |

| Self-Control | 0.01 | (0.38) | 0.003 | 0.01 | (0.88) | 0.03 | 1.25 | (0.52) | 0.40 | 2.26 | (0.54) | 0.80 |

Note. B represents mean difference; d is the standardized mean difference. Significant mean differences are in bold (p < .05). ITT = intent-to-treat analysis; CACE = complier average causal effect analysis; COSS = Children’s Organizational Skills Scale; DBD = Disruptive Behaviors Disorder Rating Scale; HPC = Homework Problems Checklist; and SSIS = Social Skills Improvement System. Positive effect sizes represent gains for treatment over control.

For estimates at six-month follow-up (other than grades), we did not use growth curve modelling because the lag time was longer than in previous measurement occasions. Instead, we examined those scores controlling for baseline.

Organization

At both the end of treatment and six-month follow-up, the ITT analysis showed a significant improvement for the treatment group compared to the control group for three of the COSS subscales, including Total Score, Materials Management, and Task Planning. The ITT analysis did not show a significant difference between treatment and control groups for the Organized Actions subscale. In the CACE analysis at both end of treatment and follow-up all subscale scores were significantly improved for participants in the treatment condition when compared to the control condition. In addition, effect sizes comparing treatment and control were larger for the CACE model than the ITT model, particularly for the Task Planning subscale. The difference between the ITT and CACE models are illustrated in Figure 3. The trajectory of the treatment group is similar for both models, but the estimates for the control group diverge. Specifically, in the ITT model, the control group improved over time, but the CACE estimates worsen slightly over time. This suggests that the control group participants who were most similar to the compliers in the treatment group had worse organizational outcomes than the control group overall.

Figure 3.

Total T-score of the parent version of the COSS scale from intake (0) through end-of-treatment measurement occasions (4). Six-month follow-up estimates (not shown) were calculated separately given the differing lag time. COSS data were only collected at times 0, 2, 3, and 4 in the plot. Lines represent the linear trend based on these data.

Disruptive Behavior

At the end of treatment the ITT analysis did not show a significant difference between treatment and control groups for either the Hyperactivity or the Inattention subscales of the DBD. In the CACE analysis, both Hyperactivity and Inattention scores significantly improved for participants in the treatment condition when compared to the control estimate. Again, similar to organization, effect sizes comparing treatment and control were larger for the CACE model than the ITT model. At follow-up, both the ITT and CACE models showed significant improvement in the Hyperactivity and Inattention subscales, but the effect size estimates for the CACE model remain much larger than that for the ITT model. The trends for each estimate suggested a similar pattern to that seen for organization; specifically, the CACE estimate of the control group suggests that the participants most similar to treatment group compliers experienced progressively worse outcomes over time.

Grades

Unlike our other outcomes, grade data were collected over nine measurement occasions, beginning with final grades for the year prior to the treatment year, followed by four grading periods in each of the treatment and post-treatment school years. Given the lag in time caused by the summer months, we elected to run separate growth curve models for the treatment year controlling for pretreatment year, and the follow-up year controlling for a single estimate of the treatment year. The ITT model suggests no significant differences between treatment and control in either analysis; however, compliers significantly outperform the control estimate in the CACE model in the follow-up year. Again, the estimate of compliance in the control group suggests that participants who would comply if offered treatment perform much worse than average when treatment is withheld.

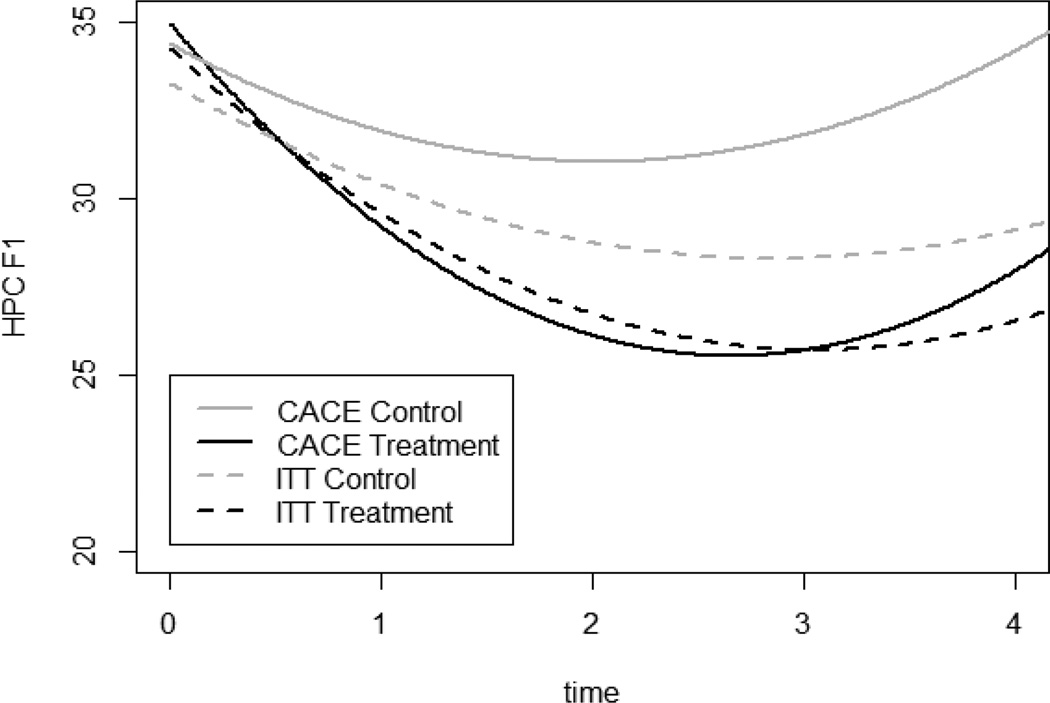

Homework Performance

At both the end of treatment and follow-up the ITT analysis showed a significant improvement for the treatment group compared to the control group for both HPC factors. Similarly, CACE estimates of both factor scores at end of treatment and follow-up were higher for participants in the treatment condition than in the control condition. In addition, effect sizes comparing treatment and control were larger for the CACE model than the ITT model. The difference between the ITT and CACE models are illustrated in Figure 4. The trajectory of the treatment group is similar for the ITT and CACE models, but the estimated trajectories for the control group diverge. Specifically, in the ITT model the control group improved in their scores over time, while in the CACE model scores worsened slightly over time. This suggests that the treatment is especially effective for compliers, and non-compliers may include some individuals who improve spontaneously.

Figure 4.

Factor 1 score of the parent version of the HPC scale from intake (0) through end-of-treatment measurement occasions (4). Six-month follow-up estimates (not shown) were calculated separately given the differing lag time.

Social Skills

At both the end of treatment and follow-up the ITT analysis did not show a significant difference for the treatment group compared to the control group for any of the SSIS subscales except for the Self-control subscale at follow-up. Scores on the Self-control subscale at follow-up were higher in the treatment condition than in the control condition. In the CACE analysis, at both end of treatment and follow-up, conditions did not differ for most SSIS subscales. At end of treatment, scores on the Responsibility subscale were higher in the treatment condition than the control condition, and at follow-up scores on the Self-control subscale were higher in the treatment condition than in the control condition. In addition, effect sizes comparing treatment and control were larger for the CACE model than the ITT model.

Discussion

The results of this study reveal that those participants who attended 80% or more of the CHP-AS sessions (i.e., compliers) demonstrated medium to large gains when compared to similar participants in the control condition. This benefit was evident on multiple parent rating scales of academic functioning (e.g., organization, homework compliance) as well as with grade point averages. In addition, unlike the results of the ITT analyses reported previously (Evans et al., 2016), there were significant improvements in two dimensions of social functioning rated by parents on the SSIS (i.e., Responsibility and Self-Control subscales). Although not as compelling as the gains in academic functioning, these findings suggest that some dimensions of social impairment may be effectively addressed with the CHP-AS when participants are optimally engaged. Using CACE modelling, the effect sizes over all variables ranged from a d of 0.56 to 2.00 at the end of treatment and from a d of 0.79 to 1.90 at follow-up. These effects are equivalent to or greater than medication effects with the same age participants in an analogue classroom study (Evans et al., 2001) and a naturalistic study of response to methylphenidate in academic functioning (Pelham et al., 2013). From these results we conclude that, consistent with the theoretical rationale of the program, TIs enable adolescents to master ADHD coping skills when attendance is commensurate with need. Moreover, training benefits persist six months post-treatment on most outcomes, suggesting that mastered skills survive into the following school year.

Other important findings can be gleaned from examining the results of the CACE analyses in comparison to the ITT analyses. For most of the comparisons there appears to be little difference between treatment compliers and outcomes for the treatment group overall (see Figures 3 and 4). This suggests that those who attended fewer than 80% of the sessions performed at levels roughly equivalent to those who attended more often. However, average group performance at the end of treatment and follow-up fell within in the normal range on several measures (e.g., COSS), suggesting that attendance varied at least partially as a function of need. We found that many of the parents whose child discontinued or had low attendance explained that they no longer “needed” the program. It is important to note that attendance in the CHP-AS is demanding on adolescents (i.e., attendance for 2 hrs. 15 min two times per week for entire academic year) and can cause challenges to parents regarding transportation. Thus, it seems that parents weighed the costs of the program against the benefits throughout the year and opted to reduce treatment once their child’s performance seemed acceptable.

The primary difference between the CACE and ITT findings pertain to the notably worse estimates for community care participants who theoretically would have complied with treatment (i.e., CACE control) when compared to the community care group overall (i.e., ITT control). In other words, when matched with compliers based on family income, conduct problems, full scale IQ, and previous academic performance, community care participants appeared to have particularly poor outcomes. These findings suggest that if treatment compliers had not consistently attended, their outcomes would have also been poor. We believe these findings are consistent with the cost-benefit hypothesis described above; specifically, the parents of participants who persisted in treatment seemed to have accurately weighed their child’s ongoing needs when deciding whether or not to continue.

Other researchers have come to similar conclusions when examining other forms of psychotherapy for adolescents. For example, Huang and colleagues (2014) examined a family intervention for Hispanic families with adolescents at-risk for substance abuse. Results of a CACE analysis suggested that treatment compliers were far less likely to report recent drug use than comparable controls, mostly due to high rates of drug use in the CACE comparison estimate. Specifically, the model suggested that likely compliers in the control group were far more likely to report substance use after treatment ended (> 45%) than the control group as a whole (31.3%). Similar to the present study, these results suggest that compliers represent a unique subset of participants who perform worse than average without treatment. Thus, CACE modelling appears particularly useful for assessing the potential potency of interventions when compliance varies, as compared to ITT analyses that answer questions pertaining to likely impact for a whole population.

Limitations

There are several limitations in the present study. First, our research design threatens two of the statistical assumptions of CACE modelling (i.e., SUTVA, exclusion restriction), as described previously. Although we attained similar results when relaxing these assumptions, we are unable to assess the degree to which these threats may have affected our estimates, so our results should be interpreted with caution. Second, our definition for treatment compliance is based on program-specific rationales, but other criteria may be as defensible. As noted in other studies (Connell, 2009; Huang et al., 2014) more stringent definitions of adequate engagement or attendance will yield larger CACE estimates and less stringent definitions lead to smaller effects. Although our rationale is based on characteristics of the CHP-AS, other definitions of compliance may yield findings that are meaningfully different from the ones reported here. Third, this study focused almost entirely on parent ratings of treatment outcome rather than teacher ratings. Given that the CHP-AS is a school-based intervention, the teacher perspective is an important component for fully evaluating treatment efficacy. However, as noted elsewhere, problems with measurement sensitivity and disagreement between secondary school teachers make these data difficult to interpret (Evans, Allen, Moore, & Strauss, 2005; Molina, Pelham, Blumenthal, & Galiszewaski, 1998). Additional research and development is needed to determine how best to incorporate secondary school teacher perspectives in treatment outcomes research. Finally, we defined compliance based on the number of sessions that participants attended, but there are alternative ways to define this construct. For example, Clarke and colleagues (2015) found that adherence to treatment protocols is more predictive of treatment response than attendance. In the present study, however, our intent was to assess the need for long-term treatment, which is consistent with the perspective that ADHD is a chronic condition requiring sustained intervention efforts. As such, session counts seemed most apt for answering our specific aims, but our findings do not speak to compliance in any qualitative sense.

Conclusion

The present results offer context for our earlier finding (Langberg et al., 2016) that attendance in the CHP-AS was unrelated to outcomes. The notion that more is better is not necessarily true, as our present findings suggest that more is better for some participants but not others. As a result, it would be helpful to have meaningful progress indicators to gauge when mastery goals are met for each participant, rather than leaving termination decisions entirely to parents. Thus, a next step in the development and refinement of the CHP is to identify algorithms for discontinuing or tapering participation. Several progress indicators might be considered for this purpose, but in our view skill mastery and generalization are crucial for maintaining developmentally appropriate treatment goals. The most recent version of the CHP is delivered by school staff during a designated period in the school day (e.g., study hall), which reduces transportation burdens on families, but potentially distances parents from treatment decisions. Establishing benchmarks and tapering procedures in this context would optimally allocate school resources without compromising outcomes important to parents or other stakeholders.

In addition to establishing benchmarks for treatment tapering, there is also a need to reexamine the effects of the CHP on social functioning. Although we noted some promising results in the present study, much more work is needed to address ADHD-related social impairments. In particular, it will be critical to examine the underlying features of the disorder most causally related to social impairment and then revise the CHP procedures to address those needs, where possible. The CHP is not unique in this respect—social impairment for children and adolescents with ADHD remains the domain of functioning least impacted by the available treatments. Furthermore, valid measures of social functioning for adolescents are lacking due to the complexity of adolescent social behavior and decreased adult monitoring over time. Such issues limit the utility of many measures of social functioning, including the SSIS.

Future research is also needed to examine strategies for successful dissemination and sustainment of the CHP. In particular, integration of the program into the regular school day can remove many of the participation barriers experienced by families (e.g., transportation). Once such barriers are removed, the CHP might then be targeted to adolescents most likely to benefit from long-term engagement. However, teachers and administrators are unlikely to adopt new programs when overwhelmed by other concerns (e.g., limited resources). Similar to parents, school officials must weigh the costs and benefits of maintaining programs like the CHP, so efficient and sustainable delivery systems are a priority. The present study provides evidence to suggest that the CHP can be efficiently targeted to specific subpopulations of students with ADHD, but additional research is needed to refine aspects of the intervention package and progress monitoring strategy as further integration occurs.

Public Health Significance.

The results of this study suggest that adolescents with ADHD who comply with long-term psychosocial treatments experience significant reductions in academic impairment when compared to comparable individuals who do not receive such treatment

Footnotes

Another 110 students were randomly assigned to a mentoring version of the program, but those participants will not be included in the present study because it generally results in lower treatment doses and “compliance” requires the participation of both students and consulting teachers (see Evans et al., 2016).

For this reason, ITT estimates in the present study vary somewhat from our previous ITT analyses based on hierarchical linear modelling (cf. Evans et al., 2016), but determinations regarding statistical significance are generally identical.

Some variability in CHP-AS compliance was noted across school sites, but the inclusion of this variable did not meaningfully change our model estimates. We also ran the models with the exclusion restriction assumption relaxed (see Jo, 2002) and, again, the pattern of results did not meaningfully change.

Contributor Information

Brandon K. Schultz, East Carolina University

Steven W. Evans, Ohio University

Joshua M. Langberg, Virginia Commonwealth University

Alexander M. Schoemann, East Carolina University

References

- Abikoff H, Gallagher R. Children’s organizational skills scales: Technical manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Anesko KM, Scholock G, Ramirez R, Levine FM. The homework problems checklist: Assessing children’s homework difficulties. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Chronis AM, Fabiano GA, Gnagy EM, Onyango AN, Pelham WE, Williams A, Seymour KE. An evaluation of the summer treatment program for children with ADHD using a treatment withdrawal design. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:561–585. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AT, Marshall SA, Mautone JA, Soffer SL, Jones HA, Costigan TE, Power TJ. Parent attendance and homework adherence predict response to a family- school intervention for children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44:58–67. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.794697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM. Employing complier average causal effect analytic methods to examine effects of randomized encouragement trials. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:253–259. doi: 10.1080/00952990903005882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Brennan LM, Shaw DS, McEachern AD, Wilson MN, Jo B. Prevention of problem behavior through annual family check-ups in early childhood: Intervention effect from home to early elementary school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:343–354. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9768-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Allen J, Moore S, Strauss V. Measuring symptoms and functioning of youth with ADHD in middle schools. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:695–706. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-7648-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Langberg JM, Schultz BK, Vaughn A, Altaye M, Marshall SA, Zoromski AK. Evaluation of a school-based treatment program for young adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2016;84:15–30. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Owens JS, Bunford N. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(4):527–551. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.850700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Pelham WE, Smith BH, Bukstein O, Gnagy EM, Greiner AR, Altenderfer L, Baron-Myak C. Dose-response effects of methylphenidate on ecologically-valid measures of academic performance and classroom behavior in adolescents with ADHD. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9:163–175. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Schultz BK, DeMars CE, Davis H. Effectiveness of the Challenging Horizons after-school program for young adolescents with ADHD. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Serpell ZN, Schultz B, Pastor D. Cumulative benefits of secondary school-based treatment of students with ADHD. School Psychology Review. 2007;36:256–273. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Jr, Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Lahey BB, Chronis AM, Burrows-Maclean L. A practical measure of impairment: Psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:369–385. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Social skills improvement system: Rating scales manual. Bloomington, MN: Pearson Clinical Assessment; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN, Vance MJ, Cook CR. Comparability of the Social Skills Rating System to the Social Skills Improvement System: Content and psychometric comparisons across elementary and secondary age levels. School Psychology Quarterly. 2011;26:27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Haboush-Deloye A, Hensley S, Teramoto M, Phebus T, Tanata-Ashby D. The impacts of health insurance coverage on access to healthcare in children entering kindergarten. Maternal and Child Health. 2014;18:1753–1764. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1420-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Gerdes AC, Mrug S, Hinshaw SP, Bukowski WM, Gold JA, Wigal T. Peer-assessed outcomes in the multimodal treatment study of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;34:74–86. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Cordova D, Estrada Y, Brincks AM, Asfour LS, Prado G. An application of the complier average causal effect analysis to examine the effects of a family intervention in reducing illicit drug use among high-risk Hispanic adolescents. Family Process. 2014;53:336–347. doi: 10.1111/famp.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo B. Statistical power in randomized intervention studies with noncompliance. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:178–193. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopta SM, Howard KI, Lowry JL, Beutler LE. Patterns of symptomatic recovery in psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:1009–1016. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Arnold LE, Flowers AM, Altaye M, Epstein JN, Molina BSG. Assessing homework problems in children with ADHD: Validation of a parent-report measure and evaluation of homework performance patterns. School Mental Health. 2010;2:3–12. doi: 10.1007/s12310-009-9021-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Evans SW, Schultz BK, Becker SP, Altaye M, Girio-Herrera E. Trajectories and predictors of response to the Challenging Horizons Program for adolescents with ADHD. Behavior Therapy. 2016;47:339–354. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Boxmeyer CL, Powell NP, Roth D, Windle M. Masked intervention effects: Analytic methods for addressing low dosage of intervention. New Directions for Evaluation. 2006;110:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Molina B, Pelham WE, Blumenthal J, Galiszewaski E. Agreement among teachers’ behavior ratings of adolescents with a childhood history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:330–339. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2703_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Owens JS, Goldfine ME, Evangelista NM, Hoza B, Kaiser NM. A critical review of self-perceptions and the positive illusory bias in children with ADHD. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2007;10:335–351. doi: 10.1007/s10567-007-0027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Evans SW, Gnagy EM, Greenslade KE. Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders: Prevalence, factor analyses, and conditional probabilities in a special education sample. School Psychology Review. 1992;21(2):285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Smith BH, Evans SW, Bukstein O, Gnagy EM, Greiner AR, Sibley MH. The effectiveness of short and long-acting stimulant medication for adolescents with ADHD in a naturalistic secondary school setting. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1087054712474688. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Werba BE, Watkins MW, Angelucci JG, Eiraldi RB. Patterns of parent-reported homework problems among ADHD-referred and non-referred children. School Psychology Quarterly. 2006;21(1):13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Salzer MS, Bickman L, Lambert EW. Dose-effect relationship is children’s psychotherapy services. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:228–238. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz BK, Evans SW. A practical guide to implementing school-based interventions for adolescents with ADHD. New York: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz BK, Evans SW, Serpell ZN. Preventing academic failure among middle school students with ADHD: A survival analysis. School Psychology Review. 2009;38:14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Kuriyan AB, Evans SW, Waxmonsky JG, Smith BH. Pharmacological and psychosocial treatments for adolescents with ADHD: An updated systematic review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34:218–232. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiel CF, Evans SW, Langberg JM. Evaluating the content of individualized education programs and 504 plans of young adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology Quarterly. 2014;29:452–468. doi: 10.1037/spq0000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck K, Finney SJ, Evans SW. Parent report of ADHD symptoms of early adolescents: A confirmatory factor analysis of the disruptive behavior disorders scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2010;70:1042–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 4th. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Individual Achievement Test. 3rd. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weller EB, Weller RA, Fristad MA, Rooney MT, Schecter J. Children’s interview for psychiatric syndromes (ChIPS) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:76–84. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler J, Carlson C. The social functioning of children with ADD and hyperactivity and ADD without hyperactivity: A comparison of their peer relations and social deficits. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 1994;2:2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG. The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analytic review. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9:490–499. doi: 10.1007/s13311-012-0135-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]