Abstract

Altered postural control and balance are major disabling issues of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Static and dynamic posturography have provided insight into PD’s postural deficits; however, little is known about impairments in postural coordination. We hypothesized that subjects with PD would show more ankle strategy during quiet stance than healthy control subjects, who would include some hip strategy, and this stiffer postural strategy would increase with disease progression.

We quantified postural strategy and sway dispersion with inertial sensors (one placed on the shank and one on the posterior trunk at L5 level) while subjects were standing still with their eyes open. A total of 70 subjects with PD, including a mild group (H&Y≤2, N=33) and a more severe group (H&Y≥3, N=37), were assessed while OFF and while ON levodopa medication. We also included a healthy control group (N=21).

Results showed an overall preference of ankle strategy in all groups while maintaining balance. Postural strategy was significantly lower ON compared to OFF medication (indicating more hip strategy), but no effect of disease stage was found. Instead, sway dispersion was significantly larger in ON compared to OFF medication, and significantly larger in the more severe PD group compared to the mild. In addition, increased hip strategy during stance was associated with poorer self-perception of balance.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Levodopa, postural strategy

1. INTRODUCTION

Postural coordination to maintain body equilibrium in upright position is organized into 2 movement patterns: the ankle and the hip strategy [1]. Recent evidence suggests that both patterns are used during quiet stance with more hip strategy used during larger sway dispersion [2][3]. Although postural control is known to deteriorate with disease severity in subjects with Parkinson’s disease (PD) [4], it is not known if severity of PD or antiparkinson medication affects postural coordination. The aim of the present study is to investigate the effects of disease severity and levodopa medication on postural strategies during quiet stance in PD using our recently proposed objective method using body-worn inertial sensors [5]. Our hypothesis was that subjects with PD would show more ankle strategy than controls and this stiffer postural strategy would increase with disease progression.

2. METHODS

2.1 Subjects

This study included 70 subjects with a diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease and a group of 21 healthy control subjects of similar age. All subjects with PD were treated with levodopa medication, and all the participants were free of musculoskeletal and other neurological impairments that could affect gait and balance. The protocol was approved by the OHSU Institutional Review Board and all participants gave their consent for the study. Subjects characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

mean values and standard deviations of clinical characteristics of PD patients and information about age, height in centimeters, body mass in kilograms, number and gender of the participants.

| Age | Height (cm) |

Body mass (kg) |

Participants | M/F | UPDRS | UPDRS rigidity subset |

PIGD | Postural stability | ABC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTR | 67(6) | 167(10) | 76(17) | 21 | 9/12 | – | – | – | – | 94(6) | |||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

|

PD |

HY 1–2 |

67(5) | 172(10) | 81(14) | 33 | 24/9 | OFF | 35(8) | OFF | 3(1) | OFF | 8(4) | OFF | 0(0) | 86(12) |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| ON | 29(8) | ON | 2(1) | ON | 7(4) | ON | 0(0) | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| HY 3–4 |

67(7) | 171(8) | 78(16) | 37 | 20/17 | OFF | 42(11) | OFF | 5(2) | OFF | 10(4) | OFF | 1(1) | 78(15) | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| ON | 35(10) | ON | 4(2) | ON | 9(4) | ON | 1(1) | ||||||||

Subjects with PD were divided for analysis into 2 groups based on disease severity, quantified by the Hoehn & Yahr scale: H&Y≤2 for mild disease and H&Y≥3 for moderate-to-severe disease.

2.2 Experimental set-up and data analysis

Subjects with PD were tested in their practical OFF state (12h after their last levodopa medication) and in the ON state (1h after levodopa medication at 1.25 times their regular dose). All participants performed 3 repetitions of quiet standing (30s each) with their arms at their sides looking straight ahead. A template was used to achieve consistent foot placement [6].

The Motor Part of the Unified Parkinson’s disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) was assessed both in OFF and ON state, and the Postural Instability and Gait Disability (PIGD) subscore was calculated as the sum of four-item of the UPDRS Part III: arising from chair, posture, gait, and pull test.

Two inertial sensors (MTX, Xsens Technologies, Enschede, Netherlands) were placed on the trunk at L5 level and on the right shank and data were collected at 50Hz. The SI was computed from the processed AP accelerations as described in our previous work [5]:

with TIP the percentage of time spent in in-phase pattern, TCP the percentage of time spent in counter-phase pattern and W a weighting factor that accounts for the percentage of time during which a clearly identified pattern is present. The SI ranges from −1 (pure hip strategy) to 1 (pure ankle strategy). Postural sway dispersion was computed as the root mean square of the trunk acceleration signal in the AP direction (RMS AP) [7][5].

2.3 Statistical Approach

The median SI and RMS AP of the 3 trials was used. Data were not normally distributed using the Kolgorov-Smirnov test, therefore a square root transformation was applied. A 2-way repeated measures ANOVA (disease severity × medication) was used to investigate the effects of disease severity and levodopa replacement on SI and RMS. Student t-tests were employed to investigate differences between healthy control subjects and PD reporting only comparison that reached a p<0.01 (Bonferroni correction for 4 comparisons). Spearman correlation was used to assess the relationship between SI, RMS AP and clinical scores. All the computations were performed using Matlab R2012b and NCSS software.

3. RESULTS

The UPDRS part III significantly improved ON compared to OFF medication in both mild and moderate-to-severe subjects with PD (p<0.0001).

3.1 Strategy Index and Postural sway

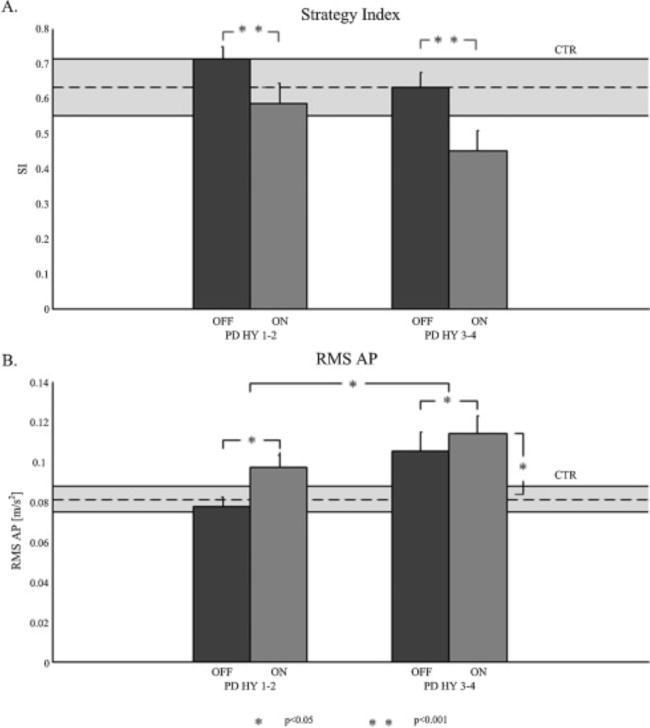

SI values show that ankle strategy is more dominant than the hip strategy in quiet stance in both PD and control subjects (Figure 1). Information about specific strategy use are reported in Table 2.

Figure 1.

(A): mean values and standard errors of Strategy Index (SI) for PD H&Y 1–2 (mild group), OFF and ON, and PD H&Y 3–4 (severe group), OFF and ON. SI for controls is represented in the stripe behind. (B): mean values and standard errors of the root mean square of acceleration in antero-posterior direction (RMS AP) for PD H&Y 1–2 OFF and ON, and PD H&Y 3–4 OFF and ON. RMS AP for controls is represented in the stripe behind.

Table 2.

mean values and standard deviations of percentages of time, with respect to trial duration, characterized by hip strategy (TCP) and ankle strategy (TIP) for the controls and PD subjects. TGREY represents the percentage of time spent in undefined strategy.

| TIP | TCP | TGREY | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTR | 76(5)% | 12(4)% | 11(1)% | ||

|

| |||||

| PD | HY 1–2 |

OFF | 80(2)% | 8(1)% | 12(1)% |

|

| |||||

| ON | 72(3)% | 13(2)% | 14(1)% | ||

|

| |||||

| HY 3–4 | OFF | 75(3)% | 12(2)% | 13(1)% | |

|

| |||||

| ON | 65(3)% | 19(3)% | 15(1)% | ||

A significant effect of medication (F=18.9, p<0.0001), but not of disease stage, was found for the SI (Figure 1A). Specifically, SI was lower (less pure ankle strategy) ON medication compared to the OFF medication.

Instead, a significant effect of medication (F=10.26, p=0.002) and of disease stage (F=5.7, p=0.02) were found for the RMS AP (Figure 1B). Specifically, RMS AP was larger in the ON medication compared to the OFF medication, with significantly increasing values with disease severity (Figure 1B). Moderate-to-severe subjects with PD ON medication showed a larger RMS AP compared to controls (p=0.008).

3.2 Correlations of SI and RMS with Clinical Scores

SI was significantly associated with the UPDRS Part III in subjects with PD ON medication (ρ=0.17, p=0.04), with more hip strategy in moderate-to-severe PD. The RMS AP was significantly associated with the UPDRS Part III (ρ=0.25, p=0.03), PIGD subscore (ρ=0.27, p=0.02) and pull test (ρ=0.26, p=0.03) in subjects with PD OFF, but not ON medication. SI and RMS AP were negatively associated (e.g., more hip strategy with larger sway) among subjects with PD, both OFF (ρ=−0.40, p<0.0001) and ON medication (ρ=−0.45, p<0.0001), but not in control subjects. The perception of balance (measured by the ABC scale) was associated to SI in subjects with PD (e.g., worse perception of balance with larger hip strategy) both OFF (ρ=0.27, p=0.03), and ON medication (ρ=0.37, p=0.001), but, again, no significant correlation was found in control subjects.

4. DISCUSSION

This short report quantifies postural strategy as well as sway dispersion during quiet stance in subjects with PD across a range of severity in both the ON and OFF levodopa state using wearable sensors. Our study demonstrated that:

Ankle strategy was preferentially used to control quiet stance in both mild and severe PD, as well as control subjects, although PD used more hip strategy in the ON dopa state;

Both disease severity and levodopa-replacement were associated with increased sway dispersion in subjects with PD;

Patient perception of balance, measured by the ABC scale, was associated with more hip strategy.

Counter to our hypothesis, subjects with PD did not show greater use of an ankle strategy compared to healthy control subjects during quiet stance, nor an increase in ankle strategy in moderate-to-severe PD compared to mild. Levodopa replacement increased the use of hip strategy, with no difference in mild or moderate PD and such increase may be related to a decreased rigidity ON medication, allowing increased postural sway, requiring more hip strategy control [8]. Although dyskinesia ON medication could be responsible for an increase use of the hip strategy, it is unlikely in the present study because we filtered the acceleration signals at 0.5 Hz, below the 1–3Hz dyskinesia components found by [9].

Postural sway dispersion was significantly related to both disease severity and medication. Larger sway was associated with severe disease, and was found ON medication, as previously reported (Curtze et al TO ADD PLEASE). Increase in postural sway with severity of disease may be due to the deterioration of other neurotransmitters in addition to dopamine later in the disease, such as acetylcholine [10][11][12]. Our objective SI measure of postural coordination was significantly associated with subjects’ perception of balance; this relationship is of particular interest as use of the hip strategy may represent more difficulty controlling balance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kelsey Priest and Triana Nagel for scheduling and testing subjects. This publication was made possible with support from Kinetics Foundation, NIH grants RC1 NS068678 and R37 AG006457.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

OSHU and Dr. Horak have a significant financial interest in and/or are employees of APDM, a company that may have a commercial interest in the results of this research and technology. This potential institutional and individual conflict has been reviewed and managed by OSHU and the Portland VA.

References

- 1.Horak FB, Nashner LM. Central programming of postural movements: adaptation to altered support-surface configurations. J Neurophysiol. 1986;55:1369–81. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.6.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Creath R, Kiemel T, Horak FB, Peterka R, Jeka J. A unified view of quiet and perturbed stance: simultaneous co-existing excitable modes. Neurosci Lett. 2005;377:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Accornero N, Capozza M, Rinalduzzi S, Manfredi GW. Clinical multisegmental posturography: age-related changes in stance control. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Mot Control. 1997;105:213–9. doi: 10.1016/S0924-980X(97)96567-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bronte-Stewart HM, Minna Y, Rodrigues K, Buckley EL, Nashner LM. Postural instability in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: the role of medication and unilateral pallidotomy. Brain. 2002;125:2100–14. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baston C, Mancini M, Schoneburg B, Horak F, Rocchi L. Postural strategies assessed with inertial sensors in healthy and parkinsonian subjects. Gait Posture. 2014;40:70–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McIlroy WE, Maki BE. Preferred placement of the feet during quiet stance: Development of a standardized foot placement for balance testing. Clin Biomech. 1997;12:66–70. doi: 10.1016/S0268-0033(96)00040-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mancini M, Salarian A, Carlson-Kuhta P, Zampieri C, King L, Chiari L, et al. ISway: a sensitive, valid and reliable measure of postural control. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2012;9:59. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuo AD, Speers RA, Peterka RJ, Horak FB. Effect of altered sensory conditions on multivariate descriptors of human postural sway. Exp Brain Res. 1998;122:185–95. doi: 10.1007/s002210050506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtze C, Nutt JG, Carlson-Kuhta P, Mancini M, Horak FB. Levodopa Is a Double-Edged Sword for Balance and Gait in People With Parkinson’s Disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30:1361–70. doi: 10.1002/mds.26269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Müller MLTM, Bohnen NI. Cholinergic dysfunction in parkinson’s disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13 doi: 10.1007/s11910-013-0377-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baston C, Ursino M. A Biologically Inspired Computational Model of Basal Ganglia in Action Selection. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2015;2015:1–24. doi: 10.1155/2015/187417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baston C, Ursino M. A computational model of Dopamine and Acetylcholine aberrant learning in Basal Ganglia. IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc Proc. 2015:6505–8. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2015.7319883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]