Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to develop an in-depth understanding of the rationale, experiences, evaluation and outcomes of using Cancer Information and Support (CIS) services in Australia, the UK and USA.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were used to gather data between November 2015 and January 2016. Telephone interviews were recorded, de-identified, transcribed and thematically analysed.

Ten users from each of three international CIS services (n = 30 in total) were recruited. Participants were eligible for inclusion if they had utilised the CIS in 2015 via telephone contact with a cancer nurse and identified as a patient or cancer survivor, or friend or family member of such a person.

Results

Four major themes were derived and included a total of 25 sub-themes. Key themes included (i) drivers for access, (ii) experience of the service, (iii) impact and (iv) an adjunct to cancer treatment services.

Conclusions

Cancer Information and Support nurses internationally act as expert navigators, educators and compassionate communicators who ‘listen between the lines’ to enable callers to better understand and contextualise their situation and discuss it with their healthcare team and family and friends. Use of the service can result in reduced worry, extend support repertoires and enable use of new knowledge and language as a tool to getting the most from the healthcare team. The positioning of CIS alongside cancer treatment services aids fuller integration of supportive care, benefiting both patients and clinicians.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00520-016-3513-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Supportive care, Cancer information, Oncology nursing, Patient experience, Cancer helpline, Patient empowerment

Introduction

Cancer Information and Support (CIS) services are community-based sources of practical, informational and emotional support for people affected by cancer. These services are predominantly offered by organisations that sit alongside, but are separate to, health services and include non-government organisations and charities including cancer societies. They typically interface with people affected by cancer through telephone helplines, e-mail or internet-based forums that act as conduits to specific supportive care programs and services. CIS services are an important resource for cancer patients, their families and friends, health professionals and in fact anyone seeking cancer information or support, which complement information from other care providers. [1]

CIS operate across many countries and settings [2]. The International Cancer Information Service Group (www.icisg.org) is a worldwide network of more than 70 organisations that deliver cancer information and support and share best practice to enhance CIS services. Although satisfaction for CIS services is routinely high, [3] a recent systematic review found that there was insufficient research regarding the level and types of benefits that CIS services may deliver [4]. ICISG recognises the need for CIS services to be evaluated beyond reasons for use and customer satisfaction. There is thought to be benefit in standardising evaluations of CIS services to cancer treatment providers. By defining the place and value of CIS in the pathway of cancer care, and integrating its referral in the clinical setting, duplication may be reduced and equity of service access promoted. There are inherent challenges associated with evaluation of services, which include scarcity of, or lack of knowledge about, appropriate and validated outcome measures; practical, logistical and resource barriers; lack of a ready to use evaluation tool; lack of research and evaluation skills and the notion that collecting evaluation metrics using a CIS interaction could disrupt that interaction [5]. There is no known routine mechanism for evaluating impact of CIS services internationally and no agreed standard for evaluating outcomes of interacting with CIS services. This study aimed to identify the perceived barriers and dimensions of benefit conferred from using a CIS as a starting point for understanding the types of constructs from which to develop a measure for more consistent evaluation of CIS services.

Evidencing the ideal function of CIS services is required to map contribution to health outcomes and quality of life and to support resource allocation decisions, service design and promotional strategies in a way that supports cancer care delivered in hospitals and primary care settings. It is known that clinician endorsement of CIS services encourages service uptake by patients [6, 7].

Methods

Design

This study utilised a qualitative descriptive research design to explore the rationale, experiences and outcomes of using CIS services. Semi-structured interviews were used to gather data between November 2015 and January 2016. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist [8] was used to aid both study design and reporting.

Setting and participants

The study was set at three different CIS services: Cancer Council Victoria’s 13 11 20 Cancer Information and Support Service (Australia), Cancer Research UK’s Cancer Information Service and American Cancer Society’s National Cancer Information Center. These services run to a similar model where nurse consultants answer cancer-related queries. There are slight differences in operation hours (American Cancer Society is the only CIS that operates 24/7). A triaged approach used in ACS meant that participants were limited to those who had contact with a nurse. Ethical approval to conduct the study was granted for all sites.

Participants were eligible for inclusion in the study if they had used a CIS in the participating organisations in 2015 via telephone contact with a CIS nurse and had consented to receive information regarding research projects and identified as a person affected by cancer—including a patient or cancer survivor or friend or family member of such a person. People affected by cancer were aged 18 years or older and able to converse in English. Callers who identified as health professionals or a member of the general public seeking general interest information were ineligible.

Procedures

Contact was made with eligible callers during the recruitment phase as they called CIS or with recent CIS users indicating an interest in participating in research. A script was used to clarify current interest in participating and, if affirmative, to describe the current study to the user. After receipt of a posted or e-mailed information sheet, people interested in participating in an interview provided verbal consent for their contact details to be supplied to the interviewer. At the midpoint of recruitment, purposive sampling with particular caller types (e.g. men, cancer diagnoses other than breast, family/friends in addition to patients) was made in an effort to provide a more diverse sample of study participants representative of CIS users.

An interview guide (Table 1) developed for the study based on recommendations by investigators and behavioural scientists across all three study sites was used. The final interview framework was assessed for face validity by two independent researchers and informally piloted by the interviewer. A scripted introduction was incorporated into the interview guide.

Table 1.

Interview guide and preamble

| Interview preamble | |

|---|---|

| Thank you for agreeing to participate in this research. I am conducting this interview with you today because you have recently used the cancer information or support service from [name of organisation]. I hope to find out more about the purpose of your contact with their cancer information and support services and how you have used the information you received. I will tape record the interview today, and please remember that you are able to stop this interview at any time and you do not have to answer any questions that you do not want to answer. The interview should take around 45 min. Can you confirm that you are happy to proceed? | |

| Topic | Specific questions |

| Experience in using the CIS |

1. What prompted you to access the service? 2. What were you expecting from the service? 3. How many times have you used the service? 4. What was your primary concern(s)? 5. What information or advice were you given? 6. How long did you engage with the service? |

| Evaluation of the CIS |

7. Was your contact with the service helpful? [How or why not?] 8. Was the information you received relevant to your query? 9. Did the service assist you in the way you were hoping? 10. Did you receive any additional information or support that was helpful? 11. Would you recommend this service to others? |

| Outcomes following the CIS |

12. Have you made contact with the support service since you first contacted them? 13. Did you feel more knowledgeable in your/others diagnosis? 14. Please describe anything you have done differently as a result of contact with this service? [eg self-care; writing a list of questions to ask oncologist at next visit] 15. Has this change been positive? [Follow up prompt: If yes, can you give an example. If not, why not?] 16. Have you been clearer about how to communicate with your health care team or informal support network [or that of the person you are caring for]? 17. Has using the CIS changed how distressed you feel about your/or others cancer diagnosis? 18. Have you felt better supported? |

| Future use |

19. Would you use a CIS again? 20. Do you feel confident a CIS could address any other information or support needs? |

All interviews were conducted via telephone by an external consultant based in the UK who was an experienced nurse proficient in exploratory research with vulnerable communities. The interviewer received a briefing on the context of the current research, participated in teleconference project meetings with project investigators during the study period and was given the opportunity to debrief after the interviews. Prior to each scheduled interview, the interviewer was informed of the participant’s name, age, status (person with cancer or carer/family member), and diagnosis (if applicable). This information was disclosed as being known by the interviewer at the outset of the interview and was often drawn on to build rapport and frame context in the initial stages of the interview. As the interviews were conducted, and in consultation with the project team, minor revisions were made to the interview framework to further explore emerging themes. Data collection stopped after data saturation was reached.

Data preparation

Interviews were audio taped and later transcribed verbatim by the interviewer. Identifying details were removed before the transcripts were shared with the research team. Original interview recordings were transferred securely to the respective CIS services and subsequently deleted from the interviewer’s files.

Categorisation of data

Two researchers (AB and AU) performed data analysis in an iterative process, identifying key concepts directly from the data. Initially, three transcripts (one from each country) were independently reviewed and concepts were theorised, compared and generated into theme lists. Secondly, all data was read and preliminary theme lists were expanded, discussed, sub-categorised and defined in tandem. As transcripts were re-read and contextualised, quotes expressing ways of imagining a particular phenomenon were identified as brief interpretations of constructs and manually assigned to themes and sub-themes as mutually agreed by the two researchers. The process of analysis moved from whole transcripts to the demonstrative quotes, to the draft definitions and back again to ensure that participants’ expressions were sufficiently appraised and interpreted through multiple lenses and not solely according to dominant constructs. This evolving analysis process expanded the theme repertoire beyond the constructs intentionally explored in the interview framework.

For each overarching theme and definition, sub-themes were named and defined and coded data (quotes) were assigned. In order to verify authenticity of analysis framework and assignment of data, themes, definitions and coded data were discussed among the research team and with input from a critical reviewer (oncology research nurse) considered a global leader in cancer control who has experience of CIS work internationally. No additional themes were identified during this process.

Results

Participant sample

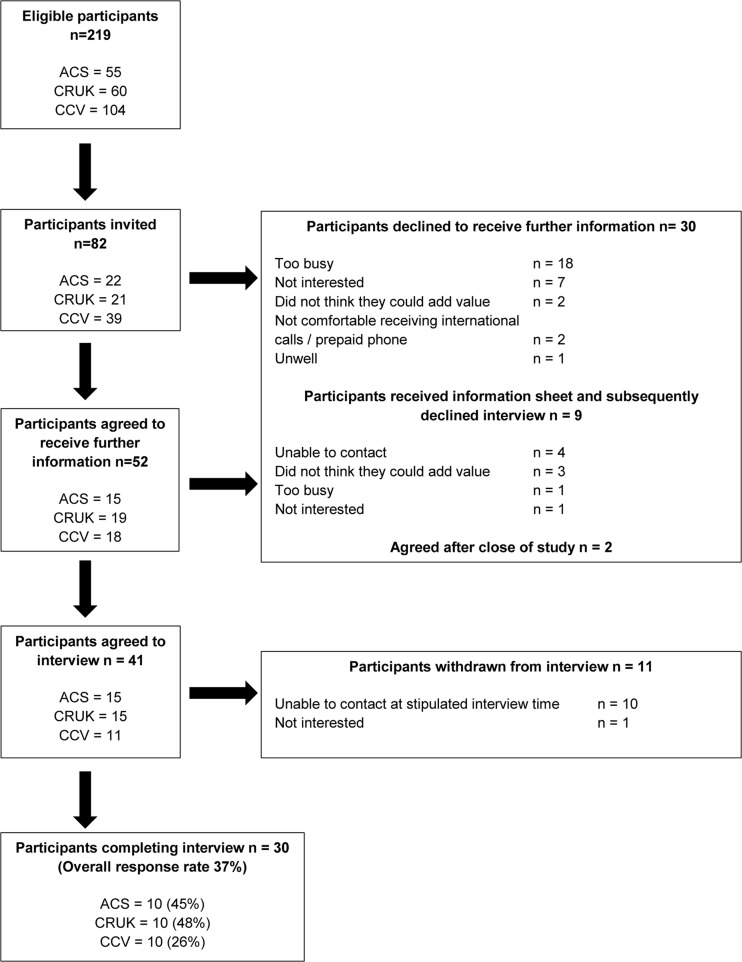

As shown in Fig. 1, 82 CIS users were approached to take part in this study from a database of 219. Of the 82 approached, 52 agreed to receive further information about the study and 30 participated in an interview (n = 10 per CIS). Overall response rate for the study was 37%. Response rates for individual CISs were 48% in the UK, 45% in the USA and 26% in Australia.

Fig. 1.

Recruitment of study sample

Demographics of the interview sample are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographics of interview sample

| CCVa | CRUKb | ACSc | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person with cancer | 6 | 4 | 9 | 19 (63%) |

| Female | 5 | 3 | 8 | 16 |

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Mean age | 59 | |||

| Tumour type | ||||

| Breast | 8 | |||

| Lymphoma | 3 | |||

| Prostate | 1 | |||

| Melanoma | 1 | |||

| Pancreas | 1 | |||

| Ovarian | 1 | |||

| Endometrial | 1 | |||

| Anal | 1 | |||

| Multiple myeloma | 1 | |||

| Familial adenomatous polyposis | 1 | |||

| Carer or family member | 4 | 6 | 1 | 11 (37%) |

| Female | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 |

| Male | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Mean age | 53 | |||

aCancer Council Victoria

bCancer Research UK

cAmerican Cancer Society

Family and friends recruited were not connected with the people affected by cancer in the sample; rather, they were calling about people with cancer who either had not used the CIS or were not interviewed as part of this study. Participants had used their local CIS at least once but sometimes multiple times and in various formats (such as via web or face to face) in addition to speaking to a cancer nurse.

Thematic analysis

Four major themes were derived from the data and included a total of 25 sub-themes. Themes, sub-themes, definitions and a selection of examples of assigned data are shown in the data analysis framework (refer to Online Resource 1).

Theme 1: drivers for access

Participants were explicitly asked about their reasons for using CIS services. Factors or conditions that prompted initial contact usually related to gaps in information or a particular emotional state which contributed to a sense of needing cancer information or support for the CIS user to be able to ‘move on’. Often, the responses pointed to an interaction in another part of the healthcare or wider cancer information system that led to a lack of, or uncertainty about, clinical information received.

[Sub-theme: previous hospital experience] I’ve only used the service a couple of times and the reason I used it was because, in my opinion, I didn’t think that I could quite get the response I needed at the hospital. [UK 4, cancer patient]

Some people, cited not knowing what to do or where to go and often with no fixed agenda, turned to a CIS without any clear knowledge of intended benefit. Participants reported feelings of being ‘lost’ and contacted a CIS on the off chance that it might be helpful. In other cases, the CIS user had a very clear practical need they knew could be satisfied by making contact with the CIS (e.g. to obtain a free wig when affected by hair loss secondary to cancer treatment).

For family and friends, CIS was considered an accessible place to ask clarifying or contextualising questions about a person they were concerned for, including gaining information relevant to someone being treated in another country.

[Sub-theme: seeking answers] There were questions that I wanted to know. We knew in Australia that there was new treatment available in America. They had removed the melanoma and weren’t doing anything else; and I thought surely he should be having follow up treatment? What about this new treatment that we’ve heard about in America” Why isn’t he having that? What about the chances of melanoma coming back as stage IV melanoma? [AUS 2, sister]

CIS services were accessed by people not understanding what the cancer meant for them, either because they had too much information and sought clarity or because the shock of diagnosis meant questions took some time to be formulated.

[Sub-theme: stunned and confused] From our point of view, not so much the first diagnosis but the third and the prognosis took us by surprise. Looking back, if I had any questions then I could have done it. But we just did not. [UK 1, son]

Theme 2: experience of using the CIS

CIS users described a range of experiences and benefits of using CIS services which served to offer an additional point of access, clarify information and help to identify new potential information and support avenues for further exploration. Participants experienced CIS nurses as reliable experts, compassionate communicators and sensitive problem solvers, which enhanced their trust and comfort in the service. CIS nurses were accessible, accommodating and gave callers the space to be heard. Notably, the nurses were reported to listen and sought to understand more than just the clinical context for the caller in order to provide most salient and tailored information and support. As a result of the nurses’ role as a navigator, callers often reported ‘bonuses’ in information, support, education or expansion of a caller’s support repertoire.

[Sub-theme: a trustworthy reliable source] She introduced herself and explained that she was a nurse and straightaway that gave me confidence; it helped me feel secure. [UK 10, cancer patient]

[Sub-theme: expert knowledge] Having that conviction to talk met by someone who has a whole wealth of experience is actually really important [UK 9, cancer patient]

Theme 3: impact

For participants, nurses helped to reduce worry, fear or burden, through reassurance, normalising or meeting information needs.

[Sub-theme: reducing worry or burden] Yeah and it makes me relaxed, like peaceful that there’s somebody to go to, that you’re not stuck somewhere with a question in your mind that’s going to make you not sleep for five days, and that’s when you call and you give them the specifics and you can work it out for that. [USA10, cancer patient]

The interaction with the CIS often resulted in improved confidence and competence to manage own health. This came about by better knowledge of systems, supports and the language with which to participate in conversations about cancer. This resulted in enhanced productivity of conversations with family, friends and the healthcare team.

[Sub-theme: preparing and informing my family] They’ve got some fantastic booklets, for example I had to use one, Talking to Children About Cancer. I found that helpful. I talked to my daughter about what is happening and what is going to happen, so she was prepared. [AUS 3, cancer patient]

Callers felt that through information obtained from the CIS, they may be able to engage in their health or the health of friends and family in a more empowered way, not only feeling both confident and competent to manage own health but also through extending their support repertoire.

[Sub-theme: knowledge as power] I picked up some medical jargon and buzzwords from the CIS that I could actually speak to the urologist. Sometimes when you engage in a conversation with an expert and you are able to throw back some of the terminology then they will say ‘well, it seems that you have done your research’. They can’t bamboozle you because you have already become a little bit more educated. So, the CIS provided the literature to explain something in very simple language. [AUS 10, cancer patient]

Theme 4: an adjunct to cancer treatment services

Participants identified CIS as a clear categorisation outside of but as a useful adjunct to the support from cancer treatment services. These supports were seen as complementary and additive to those received from health services. Participants expressed that optimal benefit cannot be fully realised without the two sources of support being drawn on, integrated and respected.

[Sub-theme: positioning and integration] I don’t know why it is that I didn’t know about the CIS in the beginning before the current oncologist…getting the word out is probably the most important thing, getting it out to every oncologist. They do their part and we need more, we need more. [USA 6, cancer patient]

Participants clearly distinguished between the scope of practice of the healthcare team responsible for the patient’s individual medical needs and the CIS who work to identify and address broader cancer informational, emotional and practical support needs and assist the caller’s interactions with their cancer care team.

[Sub-theme: boundaries] I asked, should I continue to be taking Tamoxifen and she very directly sent me back to the medical people to ask that of a consultant—it’s not for her to say. I still don’t have an answer but I’m going to see a breast consultant now about the medication. [UK10, cancer patient]

Sometimes, CIS was the only accessible source of non-clinical but essential supportive care for cancer patients and their friends and families. It was viewed as a point of access not available in the hospital setting. CIS was viewed as a ‘gap filler’—a place to go outside of set appointment times while waiting for the next stage of care.

Discussion

CIS nurses internationally act as navigators, educators and therapeutic communicators who listen between the lines to enable callers to better understand and contextualise their situation, its implications and the support options available to them. CIS services work to both interpret and enhance the meaning of information gathered from other sources and to increase a person’s informational, emotional and practical support repertoire. Use of the service can support heath literacy and empower people affected by cancer to better manage their own health and wellbeing. Central to this is support to get the most from the healthcare team. CIS is a useful adjunct to the clinical cancer environment which holds rightful responsibility for individual medical treatment. CIS nurses are found to be more accessible for cancer information and support needs with regard to the amount of time available, emotional approachability and openness to spontaneous contact from anyone who has a question about cancer.

This study is limited to English-speaking participants from Australia, UK and USA. As such, it does not represent the use and impact of CIS services across all cancer contexts or cultures, nor does it explore the use and impact of CIS by people who experience language barriers within their own health services. Different CIS users will also have different needs based on clinical, personal and geographical characteristics. Future research can draw on these differences to best characterise the usefulness of CIS services for different user profiles. Additionally, people with a more positive view of the service or those with higher levels of engagement in own health or the care of another person may be more likely to participate in an evaluation study through a bias towards more positive perspectives. However, participation in this study in all three countries was made available to any user of CIS so people with a strong negative view were equally able to participate. Reasons for declining participation mainly pertained to being too busy. It is possible participants were inclined to reflect on positive outcomes of their experience with a CIS as a result of terminology used in the interview guide. However, study rigour was enhanced by using only one interviewer to conduct all interviews across the three countries and by seeking independent and critical review of qualitative data analysis in order to minimise interpretation bias and strengthen inter-rater reliability. This study design and execution required effective collaboration to simultaneously evaluate impact of multiple CIS services. This work enables application of findings for CIS service improvement internationally.

This work extends the knowledge contributed by previous studies which focused mainly on customer satisfaction [9], reasons for using a CIS [10, 11], and functions of a CIS [12] and suggested marketing strategies for CIS services to make clearer what is available to patients and how the service is staffed [13]. Work by Livingston and colleagues [14] measured how cancer support programs empower survivors with regard to indicators such as feeling more in control of illness, feeling more confident about seeking support and being able to navigate around the healthcare system. The current study contributes information from which a pool of indicators for more consistent evaluation of CIS services can be derived. Novel in the current study is the new insight into how what is experienced in a CIS contact can then be used to facilitate beneficial and engaging interactions in the clinical context or with other support networks. This study was a first step to inform a more consistent approach to evaluating CIS services. Although it was beyond the scope of this study to explore in detail the extent of congruence in experience and outcomes for CIS users across countries, more similarities than differences were described across the participant sample. Despite key differences in healthcare models in Australia, UK and USA, the theme of CIS being an accessible mechanism for information and support when resource constraints limited extensive support seeking from cancer treatment specialists was common.

This study reinforces that there are distinct and complementary roles for cancer treatment and CIS services respectively, in supporting people affected by cancer. CIS users identify and respect these differences and seek to feel valued and heard throughout all components of the cancer support system as they draw on multiple sources of information and care. This study supports a sense of interdependence of CIS on the clinical environment and vice versa where optimal benefit from healthcare provision cannot be realised without the two sources of support being drawn on, integrated and mutually respected by those who work within it.

Study implications show there is a need to improve continuity of care and equity in access between cancer treatment services and CIS whilst respecting professional boundaries, in order to optimise cancer care and utilise the health system appropriately. With an in-depth understanding of the experience of engaging with CIS, these data can now be used to further inform the development of more consistent approaches to evaluating CIS services. There is a need to test these identified themes in new countries and languages enabling the exploration of differences between services to improve the specificity of future tools developed.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 28 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to Professor Sanchia Aranda, President-Elect, Union for International Cancer Control and CEO of Cancer Council, Australia, for the critical review of the data analysis framework and an early version of the manuscript. Sincerest thanks to Anthea Cooke of Inukshuk Consultancy, UK, for conducting the interviews in both a professional and compassionate way. Thanks to Beverly Shaw and Scott Ritchey, ACS, for their recruitment support and Kirstie Osborne, CRUK, for the review of qualitative approach.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. All authors have full control of primary data and agree to allow the journal to review data is requested.

Ethics approval

Conduct of the study at all sites was approved and reviewed by the following ethics bodies: American Cancer Society Morehouse School of Medicine International Review Board, USA (project no. 830783-1).

Cancer Council Victoria Institutional Research Review Committee, Australia (project no. IER 509). All study participants gave informed consent before taking part.

References

- 1.Grogan S, Jefford M, Kirke B, Yeoman G, Boyes A. Australia’s cancer helpline: an audit of utility and caller profile. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34:393–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morra M, Thomsen C, Veniza A, Akkerman D, Bright MA, Dickens C, et al. The international cancer information service: a worldwide resource. J Cancer Educ. 2007;22:S61–S69. doi: 10.1007/BF03174348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jefford M, Black C, Grogan S, Yeoman G, White V, Akkerman D. Information and support needs of callers to the cancer helpline, the Cancer Council Victoria. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2005;14:113–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinton-McHarg T, Paul C, Boyes A, Rose S, Valentine P, O’Brien L. Do cancer helplines deliver benefits to people affected by cancer? A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97(3):302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvador-Carulla L. Routine outcome assessment in mental health research. Curr Opin in Psychiatry. 1999;12(2):207–210. doi: 10.1097/00001504-199903000-00012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eakin EG, Stryker LA. Awareness and barriers to use of cancer support and information resources by HMO patients with breast, prostate or colon cancer: patient and provider perspectives. Psychooncology. 2001;10(2):103–113. doi: 10.1002/pon.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beesley VL, Janda M, Eakin EG, Auster JF, Chambers SK, Aitken JK, et al. Gynecological cancer survivors and community support services: referral, awareness, utilization and satisfaction. Psychooncology. 2001;19(1):54–61. doi: 10.1002/pon.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ledwick M. User survey of a cancer telephone helpline and email service. Cancer Nursing Practice. 2012;11(4):33–36. doi: 10.7748/cnp2012.05.11.4.33.c9096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckberg K, McDermott J, Brindle L, Little P, Leydon GM. The role of helplines in cancer care: intertwining emotional support with information or adviceseeking needs. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2014;32(3):359–381. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2014.897294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean A, Scanlon K. Telephone helpline to support people with breast cancer. Nurs Times. 2007;103(42):30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross T. Prostate cancer telephone helpline: nursing from a different perspective. Br J Nurs. 2007;16(3):161. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2007.16.3.22970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boltong A, Byrnes B, McKiernan S, Quin N, Chapman K. Exploring the preferences, perceptions and satisfaction of people seeking cancer information and support: implications for the Cancer Council helpline. The Australian Journal of Cancer Nursing. 2015;16(1):20–28. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livingston PM, Osborne RH, Botti M, Mihalopoulos C, McGuigan S, Heckel L, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of an outcall program to reduce carer burden and depression among carers of cancer patients [PROTECT]: rationale and design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 28 kb)