Abstract

Background

Persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH) smoke at higher rates than other adults and experience HIV-related and non-HIV-related adverse smoking consequences. The current study conducted a systematic review to synthesize current knowledge about gender differences in smoking behaviors among PLWH.

Methods

Over three thousand abstracts from MEDLINE were reviewed and seventy-nine publications met all of the review inclusion criteria (i.e., reported data on smoking behaviors for PLWH by gender). Sufficient data were available to conduct a meta-analysis for one smoking variable: current smoking prevalence.

Results

Across studies (n=51), the meta-analytic prevalence of current smoking among female PLWH was 36.3% (95% CI=28.0%-45.4%) and male PLWH was 50.3% (95% CI=44.4%-56.2%; meta-analytic OR=1.78, 95% CI=1.29-2.45). When analyses were repeated just on United States (U.S.) studies (n=23), the prevalence of current smoking was not significantly different for female PLWH (55.1%, 95% CI=47.6%-62.5%) compared to male PLWH (55.5%, 95% CI=48.2%-62.5%; meta-analytic OR=1.04, 95% CI=0.86-1.26). Few studies reported data by gender for other smoking variables (e.g., quit attempts, non-cigarette tobacco product use) and results for many variables were mixed.

Discussion

Unlike the general U.S. population, there was no difference in smoking prevalence for female versus male PLWH (both >50%) indicating that HIV infection status was associated with a greater relative increase in smoking for women than men. More research is needed in all areas of smoking behavior of PLWH to understand similarities and differences by gender in order to provide the best interventions to reduce the high smoking prevalence for all genders.

Keywords: smoking, tobacco, gender, HIV/AIDS, review, meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use is well-known to have numerous, serious health consequences and is a leading cause of mortality in the United States (U.S.) and around the world1,2. As HIV/AIDS treatment has advanced over time, smoking has had an increasing impact on the health and longevity of persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH). Tobacco has emerged as a leading killer among PLWH3 who smoke at two to three times the rate of the general adult population in the U.S.4. The negative impact of smoking on PLWH includes HIV-related complications (e.g., increased viral load, pneumonia), non-HIV medical illnesses (e.g., non-HIV/AIDS-related cancers), and greater mortality5-9. Women with HIV/AIDS face additional gender-specific consequences of smoking including adverse fetal-related outcomes (e.g., low birth weight, preterm birth) and early natural menopause10-12. Quitting smoking reduces HIV-related symptom burden13, causes of mortality related to HIV and AIDS such as bacterial pneumonia6,14, and cardiovascular morbidity15.

Gender differences in tobacco use exist in the general population. In the U.S., men are more likely than women to report current use of cigarettes and other tobacco products16,17 and nicotine dependence18. Men also report smoking more cigarettes per day (CPD) than women19,20. While the prevalence of smoking has decreased over time, women have shown less of a decrease in smoking than men16. While men and women do not differ in their interest in quitting smoking1, there is evidence that women have greater difficulty maintaining smoking abstinence20-23 (see also24) especially when quitting “cold turkey”20,25. When using pharmacotherapy, women appear to be less successful quitting with transdermal nicotine patch26,27 and more successful using varenicline compared to transdermal nicotine patch28. Further, women metabolize nicotine more quickly29, experience greater withdrawal symptoms30-32, and report greater perceived risks of quitting smoking33 than men. Together, men and women in the general population differ in a number of smoking-related behaviors, and it is important to understand whether these differences are similar or different in subgroups of smokers who are disproportionately impacted by smoking such as PLWH.

Smoking has serious health consequences for PLWH, especially for women with HIV/AIDS10-12. In addition, women in the general population appear to have more difficulty quitting smoking. It is important to identify differences in smoking behaviors for women versus men with HIV/AIDS in order to understand the best way to target efforts to reduce the consequences of smoking for all PLWH. The purpose of the current study was to conduct a systematic literature review to determine what is known about gender differences in smoking behaviors among PLWH. The goals of the review were to synthesize current knowledge, compare gender patterns to what is known in the general population, and identify areas in need of more research.

METHODS

Systematic review

A MEDLINE search was conducted on February 13, 2016 to identify papers examining gender and smoking among PLWH using search terms related to smoking (“smoking”, “cigarettes”, “tobacco”, “nicotine”) and HIV (“HIV”, “AIDS”). Abstracts from the MEDLINE search were individually examined by at least two authors to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. Full texts were obtained and examined if it was not clear whether the paper met the inclusion criteria from the abstract. Additional publications were identified from the reference lists of papers included in the review and review papers on smoking and HIV4,34,35.

In order to be included in the review, studies had to include (1) persons with HIV and/or AIDS, (2) both men and women, and (3) information about one or more aspects of smoking for men and women separately (e.g., smoking prevalence, desire to quit smoking). Exclusion criteria included: (1) being published in a language other than English, (2) not having a full text available, (3) study samples that were all or nearly all (i.e., >95%) male or female, (4) a small sample size (i.e., <30 participants), and (5) a sample where a specific number of smokers and non-smokers were recruited into the sample (for analysis of smoking prevalence). Information gathered from eligible publications included the country where the study occurred, sample size (overall and by gender), and data on smoking behavior for men versus women including statistics and p-values for the comparisons of smoking behavior for men versus women. Smoking behaviors included prevalence of current or lifetime smoking, nicotine dependence, motivation to quit, quit attempts, use of non-cigarette tobacco products, and quit outcomes. See Table 1 for a list of data gathered from studies.

Table 1.

Study characteristics and smoking variables that included data presented by gender.

| Reference | Country | Studya | Sample Sizeb | % Male | Smoking Prevalence | Nicotine Dependence | CPD | Smoking History | Post-Diagnosis Smoking | Motivation, Self-Efficacy, Beliefs about smoking | Tobacco Products | Quit Attempts | Smoking Treatmentc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collins et al., 200149 | U.S. | HCSUS | 2864 | 77 | X | ||||||||

| Turner et al., 200177 | U.S. | PCHIS | 548 | 88 | X* | ||||||||

| Mamary et al., 200246 | U.S. | -- | 228 | 83 | X | X | X | ||||||

| Gritz et al., 200443 | U.S. | -- | 348 | 78 | X* | X | |||||||

| Neumann et al., 200445 | Germany | -- | 309 | 78 | X* | X | |||||||

| Miguez-Burbarno et al., 200578 | U.S. | -- | 521 | 58 | X* | ||||||||

| Benard et al., 200679 | France | ANRS CO3 Aquitaine Cohort | 2036 | 75 | X* | ||||||||

| Elzi et al., 200668 | Ireland | -- | 417 | 82 | X | ||||||||

| Glass et al., 200680 | Switzerland | SHCS | 8033 | 69 | X* | ||||||||

| Mbulaiteye et al., 200681 | U.S. | NCI-AAC | 2795 | 82 | X | ||||||||

| Benard et al., 200739 | France | ANRS CO3 Aquitaine Cohort | 509 | 74 | X | X | |||||||

| Webb et al., 200735 | U.S. | -- | 212 | 57 | X* | ||||||||

| Carr et al., 200882 | U.S. | SMART | 4831 | 72 | X* | ||||||||

| De Socio et al., 200883 | Italy | SIMONE | 1230 | 72 | X* | ||||||||

| Duval et al., 200884 | France | -- | 593 | 70 | X* | ||||||||

| Jacobson et al., 200885 | U.S. | NHLS | 379 | 75 | X* | ||||||||

| Murdoch et al., 200886 | U.S. | UNC-CFAR | 300 | 67 | X* | ||||||||

| Desalu et al., 200987 | Nigeria | -- | 312 | 43 | X* | ||||||||

| Jaquet et al., 200988 | West Africae | IeDEA | 2920 | 29 | X* | ||||||||

| Peretti-Watel et al., 200952 | France | -- | 254 | 79 | X | ||||||||

| Webb et al., 200989 | U.S. | -- | 168 | 55 | X* | ||||||||

| Aboud et al., 201090 | U.K. | CREATE, HEART-UK | 990 | 74 | X* | ||||||||

| Cahn et al., 201091 | Latin Americaf | RAPID II | 4010 | 74 | X* | ||||||||

| Cui et al., 201048 | Canada | -- | 119 | 79 | X | ||||||||

| Encrenaz et al., 201058 | France | ANRS CO3 Aquitaine Cohort | 2223 | 77 | X | ||||||||

| Lifson et al., 201092 | 33 countriesg | SMART | 5472 | 73 | X* | ||||||||

| Tesoriero et al., 201040 | U.S. | -- | 1094 | 62 | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Amiya et al., 201153 | Nepal | -- | 321 | 57 | X* | X | |||||||

| Brion et al., 201193 | 4 countriesh | -- | 775 | 60 | X* | ||||||||

| Collazos et al., 201194 | Spain | -- | 782i | 72 | X* | ||||||||

| Petoumenos et al., 201195 | 9 countriesj | D:A:D | 27136 | 78 | X* | ||||||||

| Pines et al., 201196 | U.S. | ASD | 2108 | 80 | X* | ||||||||

| Shapiro et al., 201154 | South Africa | -- | 150 | 66 | X | ||||||||

| Stewart et al., 201197 | U.S. | -- | 289k | 56 | X* | ||||||||

| Beachler et al., 201247 | U.S. | MACS, WIHS | 379 (HIV), 266 (non-HIV) | 57 | X* | X | |||||||

| Chander et al., 201298 | U.S. | -- | 492 | 50 | X* | ||||||||

| Kristoffersen et al., 201299 | Denmark | -- | 88 | 64 | X* | ||||||||

| Iliyasu et al., 2012100 | Nigeria | -- | 296 | 72 | X* | ||||||||

| Moadel et al., 201264 | U.S. | -- | 145 | 49 | X | ||||||||

| Shuter et al., 201256 | U.S. | -- | 60 | 53 | X | ||||||||

| Villanti et al., 2012101 | U.S. | NHBS | 669l | 61 | X* | ||||||||

| Batista et al., 201344 | Brazil | -- | 1815 | 62 | X* | X | X | X | |||||

| Bryant et al., 2013102 | U.S. | -- | 115 | 63 | X* | ||||||||

| Buchacz et al., 2013103 | U.S. | -- | 3166 | 79 | X | ||||||||

| Cropsey et al., 201365 | U.S. | -- | 40 | 48 | X | ||||||||

| Shirley et al., 2013104 | U.S. | -- | 200 | 84 | X* | ||||||||

| Siconolfi et al., 2013105 | U.S. | ROAH | 811m | 74 | X* | ||||||||

| Tami-Maury et al., 201360 | U.S. | -- | 474 | 70 | X | ||||||||

| Waweru et al., 2013106 | South Africa | -- | 207 | 48 | X* | ||||||||

| Aichelburg et al., 2014107 | Austria | -- | 305 | 73 | X* | ||||||||

| Chew et al., 201467 | U.S. | -- | 774 | 56 | X | ||||||||

| Luo et al., 2014108 | China | -- | 455 | 66 | X* | ||||||||

| Miguez-Barbano et al., 2014109 | U.S. | FILTERS | 393 | 57 | X* | ||||||||

| Pacek, Latkin, Crum, et al., 2014110 | U.S. | BEACON | 358n | 62 | X* | ||||||||

| Pacek, Latkin et al., 201451 | U.S. | BEACON | 267n | 60 | X | X | |||||||

| Pacek et al., 2014111 | U.S. | NSDUH | 349 | 75 | X* | ||||||||

| Shuter, Moadel, et al., 201455 | U.S. | -- | 272 | 53 | X | ||||||||

| Shuter, Morales, et al., 201462 | U.S. | -- | 138 | 55 | X | ||||||||

| Samperiz et al., 2014112 | Spain | -- | 275 | 78 | X* | ||||||||

| Torres et al., 2014113 | Brazil | -- | 2775 | 65 | X* | ||||||||

| Tron et al., 201442 | France | ANRS-Vespa2 | 3019 | 67 | X* | X | |||||||

| Vijayaraghavan et al., 201457 | U.S. | REACH | 296 | 72 | X | ||||||||

| Ahlstrom et al., 2015114 | Denmark | -- | 4515 | 75 | X* | ||||||||

| Cioe et al., 2015115 | U.S. | SUN | 689 | 76 | X* | ||||||||

| Estrada et al., 2015116 | Spain | -- | 860o,p | 76 | X* | ||||||||

| Mdodo et al., 201537 | U.S. | MMP, NHIS | 4217 (HIV), 27731 (GP) | 71 (HIV), 48 (GP) | X* | ||||||||

| Moreno et al., 2015117 | U.S. | -- | 203 | 76 | X* | ||||||||

| Nguyen et al., 2015118 | Vietnam | -- | 1133 | 59 | X* | ||||||||

| O'Cleirigh et al., 2015119 | U.S. | -- | 333 | 82 | X | ||||||||

| Rasmussen et al., 2015120 | Denmark | DHCS, CGPS | 3233 (HIV), 12932 (GP) | 79 | X* | ||||||||

| Schafer et al., 201559 | Switzerland | SHCS | 4833 | 73 | X | ||||||||

| Shelley et al., 201563 | U.S. | -- | 127 | 84 | X | ||||||||

| Zyambo et al., 2015121 | U.S. | UAB 1917 HCC | 2464 | 75 | X* | ||||||||

| Browning et al., 201661 | U.S. | LHS | 247 | 89 | X | ||||||||

| de Dios et al., 201666 | U.S. | -- | 444 | 64 | X | ||||||||

| Marando et al., 2016122 | Italy | DHIVA | 690 | 73 | X* | ||||||||

| Muyanja et al., 2016123 | Uganda | -- | 250 | 32 | X* | ||||||||

| Shuter et al., 201641 | U.S. | -- | 267 | 54 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Wang et al., 201650 | China | -- | 2973 | 63 | X |

Key: ANRS, Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le Sida et les Hépatites Virales; ASD, Adult and Adolescent Spectrum of HIV Disease Project; BEACON, Being Active & Connected Study; BHC, Bristol HIV Cohort Study; CPD, cigarettes per day; CPGS, Copenhagen General Population Study; CREATE, Cardiovascular Risk Evaluation and Antiretroviral Therapy Study; D:A:D, Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs Study; DHCS, Danish HIV Cohort Study; DHIVA, Dietitians in HIV Study; FILTERS, Florida International Liaison for Transdisciplinary and Educational Research on Smoking Study; GP, general population; HCSUS, HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study; HEART-UK, HEART-UK/Unilever CVD risk assessment study; IeDEA, International epidemiological Database to Evaluate AIDS; LHS, Lung HIV Study; MACS, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study; MMP, Medical Monitoring Project; NCI-ACC, National Cancer Institute's AIDS Cancer Cohort Study; NHBS, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey; NHLS, Nutrition for Healthy Living Study; NSDUH, National Survey on Drug Use and Health; PCHIS, Pulmonary Complications of HIV Infection Study; RAPID II, Registry and Prospective Analysis of Patients Infected with HIV and Dyslipidemia; REACH, Research on Access to Care in the Homeless study; ROAH, Research on Older Adults with HIV; SHCS, Swiss HIV Cohort Study; SIMONE, SIndrome Metabolica ONE Study; SMART, Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy Study; SUN, Study to Understand the Natural History of HIV and AIDS in the Era of Effective Therapy Study; UAB 1917 HCC, University of Alabama 1917 HIV Clinic Cohort; U.K., United Kingdom; UNC-CFAR, University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (UNC-CFAR) HIV Clinical Cohort Study; U.S., United States; WIHS, Women Interagency HIV Study

Included in meta-analysis (i.e., presented data on current smoking by gender)

Name of parent study from which data were taken for the analyses if one was reported

Samples are of adults unless otherwise noted with superscripts

Including use of treatments, treatment adherence, treatment completion, and smoking outcomes

Adult factory workers

Benin, Côte d'Ivoire, Mali

Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela

Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Morocco, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Thailand, United Kingdom, United States, Uruguay

U.S., Puerto Rico, South Africa, Kenya

Australia, Denmark, The Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, U.K., Switzerland, France, U.S.

Co-infected with hepatitis C virus

Low-income African-American adults

Adults with past-year injection drug use

Adults age 50 years and older

Former or current injection drug users

Full sample n=895, smoking data were presented for 860 participants

Adults without past cardiovascular disease

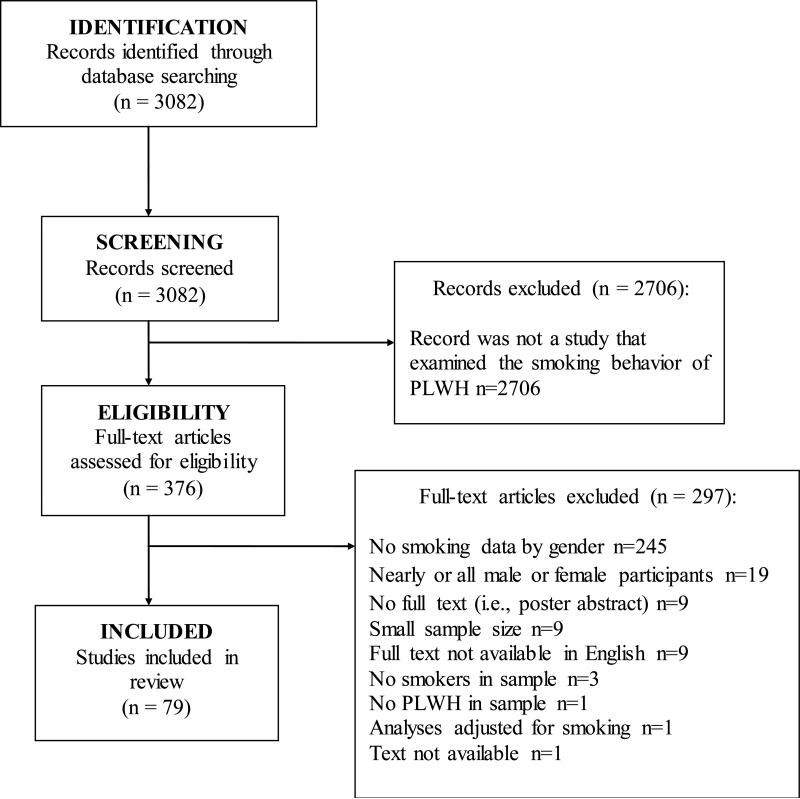

The MEDLINE search yielded 3,082 abstracts and 376 full texts were examined from the abstract list. Abstracts were excluded if the paper did not examine smoking behavior of PLWH. The main reasons for excluding full text articles were that smoking data were not presented for men and women separately, the sample consisted of all or nearly all men or women, and/or there was no full text available (e.g., an abstract of a poster conference). Seventy-nine publications met all of the inclusion criteria to be included in the review. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flowchart and Table 1 for a summary of the study characteristics and list of assessed outcomes.

Figure 1.

PRISMA figure for literature search.

Meta-analysis

We conducted random-effects meta-analyses to estimate meta-analytic prevalence of current smoking among women and men and to summarize odds ratios (OR) for the comparison of odds between women and men. Studies that included the current smoking prevalence data for men and women were included in the meta-analysis (see Tables 1 and 2). We used the R program Metafor for all analyses36, and employed an inverse variance weighting method. We first conducted the analyses for all studies that documented the prevalence of current smoking for women and men (n=51). Because the largest number of studies came from the U.S., we then limited the sample to studies conducted in the U.S. (n=23) and repeated the analyses.

Table 2.

Prevalence of lifetime smoking, current smoking, former smoking, and never smoking for male and female persons living with HIV/AIDS.

| Author | Group | Lifetime/Ever Smoking (%) | Current Smoking (%) | Former Smoking (%) | Never or Non-Smoking (%) | Significant Comparisonsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turner et al., 200177 | HIV Men | 42.1 | 2, OR=3.0; 95% CI=1.7-5.3 | |||

| HIV Women | 68.2 | |||||

| Gritz et al., 200443 | HIV Men | 50.4 | 19.1 | 30.5 | 1, OR=1.90, 95% CI=1.08-3.33 | |

| HIV Women | 34.8 | 7.6 | 57.6 | |||

| Neumann et al., 200445 | HIV Men | 67.5 | 1, p<0.01 | |||

| HIV Women | 49.3 | |||||

| Miguez-Burbarno et al., 200578 | HIV Men | 65.7 | ~11.0 | ~24.0 | Not reported | |

| HIV Women | 59.3 | ~13.0 | ~27.0 | |||

| Benard et al., 200679 | HIV Men | 51.1 | 4, OR=0.93, 95% CI-0.76-1.14 | |||

| HIV Women | 49.3 | |||||

| Glass et al., 200680 | HIV Men | 58.4 | Not reported | |||

| HIV Women | 53.8 | |||||

| Mbulaiteye et al., 200681 | HIV Men | 69b | Not reported | |||

| HIV Women | 55b | |||||

| HIV MSM | 60b | |||||

| Webb et al., 200735 | HIV Men | 54.8 | 4, p=0.52 | |||

| HIV Women | 56.7 | |||||

| Carr et al., 200882 | HIV Men | 42.7 | Not reported | |||

| HIV Women | 33.7 | |||||

| De Socio et al., 200883 | HIV Men | 61.8 | Not reported | |||

| HIV Women | 60.2 | |||||

| Duval et al., 200884 | HIV Men | 48.2 | 17.8 | 34.0 | 1, p<0.001 | |

| HIV Women | 30.3 | 16.3 | 53.4 | |||

| Jacobson et al., 200885 | HIV Men | 43.3 | Not reported | |||

| HIV Women | 66.7 | |||||

| Murdoch et al., 200886 | HIV Men | 67.2 | 1, p=0.015 | |||

| HIV Women | 53.5 | |||||

| Desalu et al., 200987 | HIV Men | 42.2 | 35.6 | 57.8 | 1, p<0.001 (LS) | |

| HIV Women | 13.6 | 11.9 | 86.4 | |||

| Jaquet et al., 20 0988 | HIV Men | 46.2 | 15.6 | 1, p-values not reported | ||

| HIV Women | 3.7 | 0.6 | ||||

| Webb et al., 200989 | HIV Men | 68.5 | 4, p=0.52 | |||

| HIV Women | 72.4 | |||||

| Aboud et al., 201090 | HIV Men | 45.0 | Not reported | |||

| HIV Women | 16.0 | |||||

| GP Men | 13.4 | |||||

| GP Women | 12.7 | |||||

| Cahn et al., 201091 | HIV Men | 25.0 | 1, p<0.001 | |||

| HIV Women | 16.7 | |||||

| Cui et al., 201048 | HIV Men | 45.7 | 22.3 | 31.9 | Not reported | |

| HIV Women | 36.0 | 8.0 | 56.0 | |||

| Lifson et al., 201092 | HIV Men | 42.8 | 26.8 | 30.4 | 1, p<0.001 | |

| HIV Women | 34.2 | 19.6 | 46.2 | |||

| Amiya et al., 201153 | HIV Men | 72.0 | 1, OR=9.20, 95% CI=3.80-22.26 | |||

| HIV Women | 15.0 | |||||

| Brion et al., 201193 | HIV Men | 50.7 | 1, p=0.001 | |||

| HIV Women | 38.7 | |||||

| Collazos et al., 201194 | HIV Men | 87.6 | 1, p=0.005 | |||

| HIV Women | 79.7 | |||||

| Petoumenos et al., 201195 | HIV Men | 46.1 | 24.8 | 29.1 | 1, p-values not reported | |

| HIV Women | 38.3 | 18.3 | 43.4 | |||

| Pines et al., 201196 | HIV Men | 69.7 | 8.0 | 22.3 | Not reported | |

| HIV Women | 57.2 | 7.9 | 34.9 | |||

| Stewart et al., 201197 | HIV Men | 43.2 | 1, OR=1.87, 95% CI= 1.14-3.06 | |||

| HIV Women | 28.9 | |||||

| Beachler et al., 201247 | HIV Men | 32.0 | 68.0 | Not reported | ||

| HIV women | 46.0 | 54.0 | ||||

| Non-HIV men | 18.0 | 82.0 | ||||

| Non-HIV women | 48.0 | 52.0 | ||||

| Chander et al., 201298 | HIV Men | 67.9 | 1, p<0.05 | |||

| HIV Women | 58.5 | |||||

| Iliyasu et al., 2012100 | HIV Men | 10.8 | 24.5 | 64.6 | 1, p<0.001 | |

| HIV Women | 0.0 | 1.2 | 98.8 | |||

| Kristoffersen et al., 201299 | HIV Men | 51.8 | 4, p=0.11 | |||

| HIV Women | 3.1 | |||||

| Villanti et al., 2012101 | HIV Men | 91.2 | 8.8 | Not reported | ||

| HIV Women | 90.0 | 10.0 | ||||

| Batista et al., 201344 | HIV Men | 32.5 | 25.0 | 42.5 | 1, p<0.001 | |

| HIV Women | 22.9 | 27.5 | 49.6 | |||

| Bryant et al., 2013102 | HIV Men | 58.3 | 15.3 | 26.4 | 4, p-value n.s. | |

| HIV Women | 74.4 | 9.3 | 16.3 | |||

| Buchacz et al., 2013103 | HIV Men | 59.3 | 1, p=0.001 | |||

| HIV Women | 51.1 | |||||

| Shirley et al., 2013104 | HIV Men | 29.8 | 39.9 | 30.3 | 4, p=0.71 | |

| HIV Women | 25.0 | 37.5 | 37.5 | |||

| Siconolfi et al., 2013105 | HIV H Men | 71.9 | 1, p<0.001 | |||

| HIV MSM | 36.8 | |||||

| HIV H Women | 55.9 | |||||

| Waweru et al., 2013106 | HIV Men | 23.3 | Not reported | |||

| HIV Women | 7.4 | |||||

| Aichelburg et al., 2014107 | HIV Men | 48.9 | Not reported | |||

| HIV Women | 37.8 | |||||

| Luo et al., 2014108 | HIV Men | 90.4, 0.3, 1.7c | 1, p<0.001d | |||

| HIV Women | 2.6, 22.1, 0.0c | |||||

| Miguez-Barbano et al., 2014109 | HIV Men | 66.5e | 1, p<0.03g | |||

| HIV Women | 53.9f | |||||

| Pacek, Latkin, Crum, et al., 2014110 | HIV Men | 73.4 | 4, p=0.34 | |||

| HIV Women | 77.9 | |||||

| Pacek et al., 2014111 | HIV Men | 48.3 | 16.9 | 34.9 | 3, p=0.025 | |

| HIV Women | 48.9 | 10.2 | 40.9 | |||

| Samperiz et al., 2014112 | HIV Men | 61.4 | 25.6 | 13.0 | 4, p-value n.s. | |

| HIV Women | 61.7 | 23.3 | 15.0 | |||

| Torres et al., 2014113 | HIV Men | 33.4 | 22.9 | 43.6 | 1, p<0.001 | |

| HIV Women | 23.3 | 25.8 | 50.9 | |||

| Tron et al., 201442 | HIV H Men | 32.8 | 38.2 | 29.0 | HIV men versus HIV women: Not reported; 5,p=0.001 6,p=0.002 |

|

| HIV MSM | 41.8 | 24.6 | 33.6 | |||

| HIV Women | 41.2 | 28.0 | 30.7 | |||

| GP Men | 29.2 | |||||

| GP Women | 22.9 | |||||

| Ahlstrom et al., 2015114 | HIV Men | 54.6 | 18.3 | 27.1 | Not reported | |

| HIV Women | 37.6 | 13.2 | 49.1 | |||

| Cioe et al., 2015115 | HIV Men | 40.4 | 2, p=0.04 | |||

| HIV Women | 48.8 | |||||

| Estrada et al., 2015116 | HIV Men | 54.8 | 4, p=0.81 | |||

| HIV Women | 53.9 | |||||

| Mdodo et al., 201537 | HIV Men | 65.2h | 42.9h, 40.9i | 22.3h | 4,p=0.34 (M versus W, p=0.14 (T versus W) 5,p<0.001 6,p<0.001 |

|

| HIV Women | 56.9h | 41.5h, 34.6i | 15.4h | |||

| HIV Transgender | 33.9h | |||||

| GP Men | 49.2 h | 23.3 i | 25.7 h | |||

| GP Women | 36.4 h | 18.0 i | 18.5 h | |||

| Moreno et al., 2015117 | HIV Men | 45.5j, 21.4k | 33.1 | 4, p=0.31 | ||

| HIV Women | 34.7j, 30.6k | 34.7 | ||||

| Nguyen et al., 2015118 | HIV Men | 59.7 | 15.6 | 24.7 | 1, p<0.01 | |

| HIV Women | 2.6 | 0.9 | 96.6 | |||

| O'Cleirigh et al., 2015119 | HIV Men | Not reported | 1, p=0.005l | |||

| HIV Women | Not reported | |||||

| Rasmussen et al., 2015120 | HIV Men | 51.6 | 19.4 | 28.9 | Not reported | |

| HIV H Men | 42.0 | 16.7 | 41.3 | |||

| HIV MSM | 51.4 | 0.2 | 28.5 | |||

| HIV Women | 29.9 | 15.9 | 54.1 | |||

| GP Men | 19.6 | 34.4 | 46.0 | |||

| GP Women | 19.2 | 34.4 | 46.4 | |||

| Zyambo et al., 2015121 | HIV H Men | 39.0 | 24.9 | 36.0 | 1 (CS), MH versus W, OR=1.8, 95% CI=1.3-2.6; MSM versus W, OR=1.5, 95% CI=1.1-1.9m 3 (FS), MH versus W, OR=2.3, 95% CI=1.5-3.2; MSM versus W, OR=1.7, 95% CI=1.2-2.4m |

|

| HIV MSM | 39.5 | 22.9 | 37.5 | |||

| HIV Women | 34.9 | 15.9 | 49.3 | |||

| Marando et al., 2016122 | HIV Men | 49.9 | 14.4 | 30.9 | 4, p=0.79 | |

| HIV Women | 53.4 | 12.2 | 29.1 | |||

| Muyanja et al., 2016123 | HIV Men | 44.4 | 6.2 | 4, p=0.06 (CS) 3, p<0.001 (LS) |

||

| HIV Women | 8.3 | 1.8 |

Note: data from general population (GP) samples or samples of men and women without HIV are presented in italics

Key: CPD, cigarettes per day; CS, current smoking; FS, former smoking; GP, general population; H, heterosexual; LS, lifetime smoking; M, men; MSM, men who have sex with men; T, transgender; W, women

Significant comparisons of the smoking prevalence of HIV men versus HIV women; HIV men versus GP men; and HIV women versus GP women are labeled by outcome (1-7, see below). If the comparison was for one or some of the smoking statuses but not all, the smoking status that the statistic refers to is labeled (e.g., CS, FS). Statistics may have been calculated for the percentage of men or women who reported a smoking status. If so, that p-value is presented and the percentage of smokers within gender was calculated by the authors.

1, significant difference in smoking prevalence for men with HIV compared to women with HIV or significant differences in distribution of smoking status for men with HIV compared to women with HIV: greater current smoking prevalence for men with HIV compared to women with HIV

2, significant difference in smoking prevalence for men with HIV compared to women with HIV or significant differences in distribution of smoking status for men with HIV compared to women with HIV: greater current smoking prevalence for women with HIV compared to men with HIV

3, significant difference in smoking prevalence for men with HIV compared to women with HIV or significant differences in distribution of smoking status for men with HIV compared to women with HIV: differences in lifetime, former, or never smoking

4, no significant difference in smoking prevalence or distribution of smoking prevalences for women with HIV versus men with HIV.

5, significant difference in smoking prevalence for men with HIV compared to GP men or significant differences in distribution of smoking status for men with HIV compared to GP men: greater smoking prevalence for men with HIV than GP men

6, significant difference in smoking prevalence for women with HIV compared to GP women or significant differences in distribution of smoking status for women with HIV compared to GP women: greater smoking prevalence for women with HIV than GP women

7, significant difference in smoking prevalence for MSM with HIV compared to GP MSM or significant differences in distribution of smoking status for MSM with HIV compared to GP MSM: greater smoking prevalence for MSM with HIV compared to GP MSM

Percent who reported smoking 10 or more cigarettes per day (lifetime)

Cigarettes only, chewing tobacco only, cigarettes and chewing tobacco, respectively

Greater prevalence of cigarette smoking for men versus women; greater prevalence of chewing tobacco use for women versus men

Nonmentholated cigarettes 22.3%, mentholated cigarettes 44.2%

Nonmentholated cigarettes 11.8%, mentholated cigarettes 42.0%

Greater prevalence of nonmentholated cigarette smoking for men versus women; similar prevalence of mentholated cigarette smoking for women versus men

Weighted prevalence, n=3981

Adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, and poverty level. HIV n=4207, GP n=27603

Prevalence of current daily smoking

Prevalence of current occasional smoking

While the smoking prevalences were not reported in the text, it was reported in text that smokers were more likely to be male than female

Adjusted for “clinically relevant” variables

RESULTS

Smoking prevalence (Table 2)

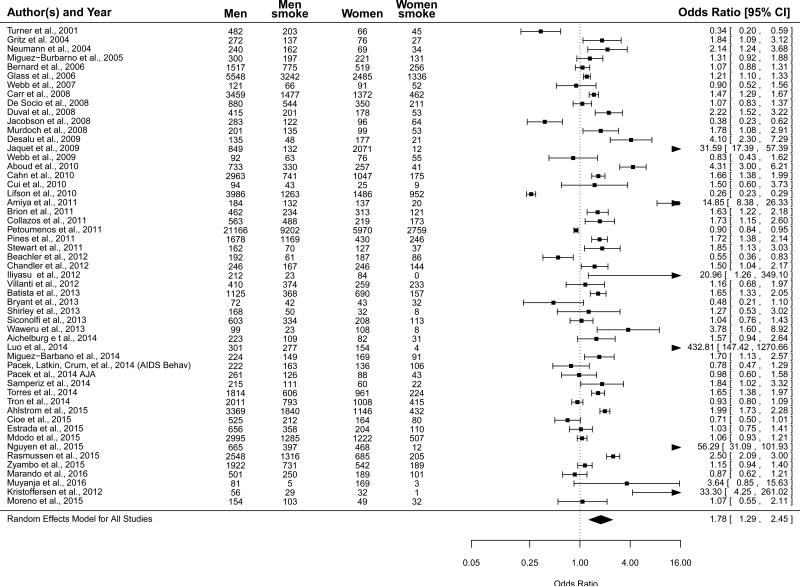

See Table 2 for prevalences of lifetime/ever, current, former, and never smoking for PLWH presented by gender. Across all studies that could be included in the meta-analysis (see Table 1), the prevalence of current smoking among women was 36.3% (95% CI=28.0%-45.4%) and among men was 50.3% (95% CI=44.4%-56.2%). For both women and men, the residual heterogeneity of effect sizes was large. For women, Q52=2322.94, p<0.001, and I2=99.45%. For men, Q52=3604.18, p<0.001, and I2=99.51%. When comparing women and men (referent = women), the meta-analytic OR was 1.78 (95% CI=1.29-2.45), indicating that averaged across investigations men had 78% greater odds of current smoking than women (Figure 2). Considering the high degree of residual heterogeneity (Q52=1508.67, p<0.001, and I2=98.92%), this OR should be interpreted as a weighted expected estimate across studies, without drawing conclusions about its representativeness for any one given study.

Figure 2.

Forrest plot for smoking prevalence for persons living with HIV/AIDS by gender for all eligible studies (referent = women; n=51).

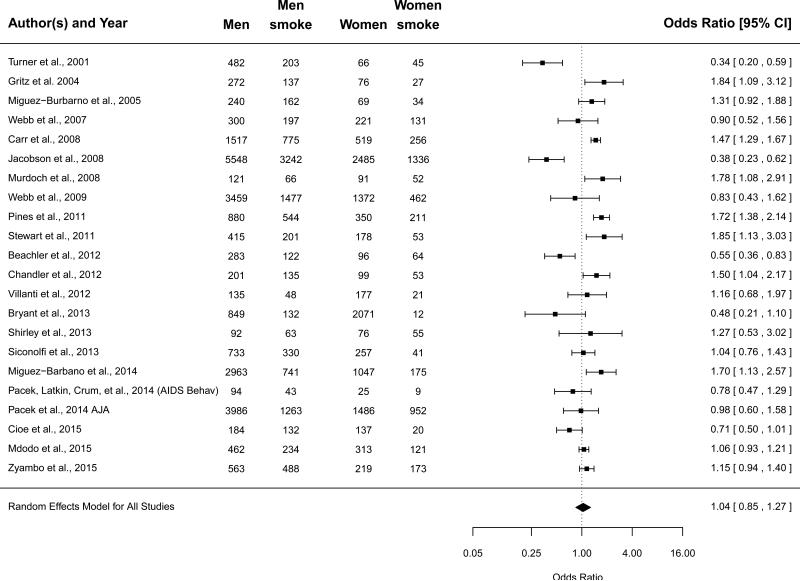

When selecting for studies conducted in the U.S. the meta-analytic prevalence of current smoking among women was 55.1% (95% CI=47.6%-62.5%), and among men was 55.5% (95% CI=48.2%-62.5%). For both women and men, the residual heterogeneity of effect sizes was large. For women Q22=453.39, p<0.001, and I2=96.52%. For men, Q22=931.21, p<0.001, and I2=98.54%. When comparing women and men (referent = women), the meta-analytic OR was 1.04 (95% CI=0.86-1.26), indicating a failure to reject the null hypothesis that across studies, women and men did not differ in their odds of current smoking (Figure 3). Considering the high degree of residual heterogeneity (Q22=110.41, p<0.001, and I2 =86.52%), this OR should be interpreted as a weighted expected estimate across studies, without drawing conclusions about its representativeness for any one given study.

Figure 3.

Forrest plot for smoking prevalence for persons living with HIV/AIDS by gender for studies conducted in the United States (referent = women; n=23).

Among studies that reported the prevalences of smoking for men and women with HIV and men and women in the general population, current smoking prevalences were higher and former smoking prevalences were lower for men and women with HIV (see Table 2). One study37 that included transgender participants also reported a higher current smoking prevalence for transgender PLWH compared to men or women from the general population.

Other aspects of smoking or tobacco use

Nicotine dependence/addiction

Two studies used the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence38 to examine moderate or strong dependence on nicotine in PLWH by gender39,40, a third study used the Modified Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire41, and a fourth study defined dependence by either the time to first cigarette in the morning (<30 minutes) or CPD (>20)42. While there was no significant gender difference in the report of moderate/strong nicotine dependence in 509 adults in France (men 60.9%; women 58.2%; OR=1.12, 95% CI=0.61-2.06)39, a lower percentage of women (47.8%) than men (60.0%) reported moderate/strong nicotine dependence in a sample of 1094 U.S. adults (OR=1.5, 95% CI=1.0-2.2, p<0.05)40. There was no difference in the average level of nicotine dependence in 167 U.S. adults (men M=4.8, SD=2.2; women M=5.1, SD=2.0; p=0.17)41. Finally, among 3,019 French adults42, HIV-infected men who have sex with men were more likely to report strong nicotine dependence than general population men (63.7% versus 49.0%; OR=1.37, 95% CI=1.24-1.51). In that study, heterosexual men with HIV and women with HIV were not more likely to report strong nicotine dependence than men or women in the general population, respectively.

Cigarettes per day (CPD)

Some studies found no gender differences in CPD41,43-45 while other studies reported a greater number of CPD smoked by men compared to women40,46. In one study of PLWH in New York (U.S.), more men (25.9%) than women (14.8%) reported smoking ≥20 CPD (p=0.03)41. Beachler and colleagues47 found that women with and without HIV reported a similar number of CPD (<1 CPD, 54% versus 52%; 1-9 CPD, 31% versus 31%; 10-19 CPD, 13% versus 14%; 20 or more CPD, 2% versus 3%; no significance test reported) while more men with HIV, compared to men without HIV, appeared to report smoking high numbers of CPD (<1 CPD, 68% versus 82%; 1-9 CPD, 12% versus 10%; 10-19 CPD, 11% versus 5%; 20 or more CPD, 10% versus 3%; no significance test reported).

Smoking history

There were no gender differences in the age of smoking initiation for 267 PLWH in New York (U.S.) (men M=16.6 years old, SD=6.3; women M=15.9, SD=4.3; p=0.34)41 or for 1,815 adults from Brazil (men M=16.9 years old; women M=16.5; p=0.61)44. One additional study found no gender difference in pack years (men M=24.0, SD=17.6, women M=24.0, SD=20.7)48.

Change in smoking after HIV diagnosis

Three studies examined changes in smoking behavior after an HIV diagnosis with mixed results44,49,50. There was no gender difference in cutting down or quitting smoking following an HIV diagnosis among 2,864 PLWH in the U.S.49 and no difference in starting smoking following an HIV diagnosis among 966 PLWH in Brazil44. In a study of 2,973 PLWH in China50, women were more likely than men to report quitting smoking following an HIV diagnosis (30.3% versus 18.4%, p<0.01). There were no gender differences with regard to increasing smoking or decreasing smoking after their diagnosis.

Motivation to quit

Studies consistently found no differences in motivation to quit smoking for male and female PLWH39-41,46,51-54.

Abstinence self-efficacy and beliefs about smoking

Shuter and colleagues found no gender differences in overall abstinence self-efficacy41,55, abstinence self-efficacy related to specific situations (e.g., positive affect/social situations, negative affect)41, or beliefs about smoking-related risks (e.g., looking older) and benefits (e.g., weight control)56. Tesoriero and colleagues40 also found no gender differences in general smoking knowledge (e.g., risk of lung cancer is higher among smokers) and HIV-related smoking knowledge (e.g., smoking is a serious health concern for HIV positive individuals).

Quit attempts and outcomes

In a sample of PLWH in San Francisco, California (U.S.), a greater proportion of men than women reported a lifetime quit attempt (81% versus 40%; p<0.001)46. Other studies found no gender differences in the proportion of men versus women who reported a quit attempt over one year40, two years57, or five years58. There were also no gender differences in the number of past-year or lifetime quit attempts among PLWH in New York (U.S.)41. Over a 14 year period, a similar number of men and women reported quitting smoking (26.6% versus 24.7%) and relapsing to smoking after quitting (11.8% versus 11.9%)59.

Use of non-cigarette tobacco products

Two papers examined the use of non-cigarette tobacco products by gender among PLWH in the U.S. entering smoking cessation treatments41,60. In the first study60, 23.2% of men and 17.7% of women reported polytobacco use (i.e., use of cigarettes plus at least one other tobacco product “every day or some days”; p=0.19). In the second study41, men and women did not differ in their reported use of pipes (5.8% versus 4.2%, p=0.78), cigars (18.1% versus 13.2%, p=0.28), chewing tobacco (2.9% versus 1.7%, p=0.69), or snuff (0.7% versus 0.0%; p=1.00).

Smoking cessation treatment

Use of Treatments

One study found that women were not significantly more likely than men to report lifetime use of any type of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy (OR=1.27, 95% CI=0.71-2.28)51. A second study41 found gender differences in the use of some smoking cessation treatments: more women than men reported past use of nicotine replacement therapy (68.3% versus 55.6%, p<0.05), varenicline (28.5% versus 17.4%, p<0.05), and acupuncture (24.4% versus 11.8%, p<0.01) while there were no differences in the use of bupropion, quit line, group counseling, individual counseling, or a website.

Treatment Completion and Adherence

In clinical trials of smoking cessation treatment for PLWH, gender was not associated with adherence to study medication (varenicline or nicotine replacement therapy)61-63, number of counseling calls completed61, or number of study appointments completed64. One study of brief counseling and nicotine replacement therapy reported that women were more likely to complete treatment than men (64.3% versus 25.0%; p=0.023)65. A trial of transdermal nicotine patch for smoking cessation in 444 PLWH found that gender was not a moderator in the relationship between greater social support and greater adherence to transdermal nicotine patch66.

Treatment Outcomes

Among five smoking treatment studies — mostly of pharmacotherapy and counseling— that examined quit outcomes by gender62,64,66-68, none found significant gender differences in abstinence rates. One feasibility pilot study of a web-based intervention and transdermal nicotine patch62 found a trend toward a higher quit rate for women versus men (11.7% versus 2.7%; p=0.08) and may have been underpowered to find a statistically significant difference. Interestingly, female participants who completed all 8 web-based sessions and who visited all of the web pages showed high rates of quitting (30.8% and 40%, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Tobacco use is the most important preventable cause of excess mortality in adults worldwide1,2 with serious additional health risks for PLWH7,9. Gender differences in smoking behaviors have been found in general population samples16,20, and women with HIV face gender-specific consequences of smoking10-12. The purpose of this paper was to synthesize published data on gender differences in smoking behaviors for PLWH. A systematic review was conducted to examine a range of smoking behaviors and a meta-analysis compared the prevalence of current smoking for female versus male PLWH.

The largest amount of data available on gender and smoking for PLWH was for current smoking prevalence. Men and women with HIV/AIDS reported current smoking prevalences that were very high and much higher than men and women in the general population, consistent with other findings4. Even though men reported higher smoking prevalences than women when all global data were considered, the prevalences of current smoking for male PLWH and female PLWH were both greater than 50% and not statistically different from each other when considering U.S. data. Although men are more likely than women to report current smoking in the general U.S. population (men 16.7%; women 13.6%)16, this difference is not manifest in the subsample of U.S. adults with HIV, suggesting that the added relative risk of smoking for people with HIV is greater for women than for men. Whereas there is a continued need for targeted efforts to reduce smoking among all persons with HIV, women with HIV may demonstrate disproportionate health disparities related to smoking due to the greater relative difference in smoking between those with HIV and the general population for women (55.1% versus 13.6%) compared to men (55.5% versus 16.7%).

PLWH report high rates of current and past use of alcohol and other drugs124,125. Alcohol and substance abuse is related to higher smoking prevalences and lower quit rates for the general population126,127 and for PLWH37,43,121. In this review, two studies examined smoking prevalence in samples of current/past injection drug users101,110 and reported similar smoking rates for men and women (91.3% versus 90.0%101; 73.4% versus 77.9%110). The majority of the other studies (n=56) reported some aspects of alcohol and/or drug use behavior in their samples; however, no study examined the relationship of alcohol/drug use/abuse to gender differences in smoking behavior. It may be useful for future studies to examine how gender differences in smoking prevalence and other smoking-related behaviors differ for PLWH with and without alcohol and drug use/abuse.

Few studies examined gender differences in smoking-related behaviors other than smoking prevalence, suggesting the need for more research on gender for all aspects of smoking. Mixed results were reported for several smoking variables (e.g., CPD, quit attempts). For some of these variables, differences by gender have been found in general population samples. For example, U.S. women were more likely to report making a quit attempt than men (45.8% versus 41.5%; OR=1.19, 95% CI=1.13-1.26)69. Due to the small number of studies and the mixed results, it is not clear yet if men and women with HIV demonstrate differences in these smoking variables. Future examinations of smoking behavior by gender will help clarify where gender differences do and do not exist and how strategies tailored by gender may be useful for prevention and intervention programs.

While some gender differences were suggested for certain smoking variables, no gender differences were found for other variables (e.g., quit motivation, use of non-cigarette tobacco products). A lack of gender differences have also been found in general population samples in some cases (e.g., motivation to quit smoking70) while differences have been reported for other variables. For example, U.S. men are more likely than U.S. women to use non-cigarette tobacco products17, but this difference does not appear to be seen among PLWH, likely due to the higher rates of tobacco use by women with HIV compared to women in the general population. More research on non-cigarette tobacco products would be beneficial, especially alternative nicotine-delivery products that have shown recent increases in use (e.g., e-cigarettes71).

Successful smoking cessation sustained over time is critical for reducing smoking-related consequences and disease. Whereas no differences in quit outcomes were found for the studies that examined data by gender, overall quit rates were generally very low with the large majority of men and women being unable to abstain from smoking over time. In general, there is a need for more efficacious and effective smoking treatments for PLWH72-75. More data by gender on smoking variables would help to inform efforts to develop smoking interventions that improve quit outcomes for both men and women. For example, women in the general population are less likely than men to have success when quitting without pharmacotherapy20,25. In this review, women with HIV were equally or more likely than men to report the use of pharmacotherapies. The greatest number of women reported using nicotine replacement therapy, similar to general population samples69; however, varenicline shows a greater advantage over transdermal nicotine patch for women compared to men in the general population28. Women with HIV may benefit from information about the relative efficacy of different pharmacotherapies to quit smoking. No studies were identified that examined a number of smoking-related variables that may impact cessation success (e.g., cravings and withdrawal76) and would be additional useful areas of future research.

There are a number of limitations to the current work. First, the criteria for inclusion in the review led to the exclusion of papers in languages other than English, not accessible online, or published in the form of a conference abstract. Second, data on most smoking behaviors came from a small number of studies and from a limited number of countries. Consequently, meta-analysis could only be conducted on current smoking prevalence. As more researchers examine gender differences in other smoking behaviors of PLWH, a clearer picture of these behaviors for men and women will emerge and can then be applied to efforts to help men and women with HIV to quit smoking. Third, very few studies reported data on persons who identified as transgender. More research is needed to examine differences in smoking behaviors of PLWH who identify as transgender compared to PLWH who identify as cisgender.

CONCLUSIONS

PLWH smoke at very high rates compared to the general population and female gender is associated with a greater difference in smoking prevalence between PLWH and the general population. Little is known about the smoking behavior of transgender PLWH or gender differences in smoking behaviors related to cessation success such as withdrawal symptoms. A more detailed understanding of gender differences among PLWH relating to specific smoking behaviors and not limited to simple prevalence statistics would help to inform smoking cessation interventions for all PLWH. Further, more research on smoking interventions with an emphasis on gender would help to ensure that interventions are optimized for both men and women PLWH.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None

Sources of Support: This work was supported in part by awards R01-DA036445, R01-CA192954, and R34-DA037042 from the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Cancer Institute, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: Data from this paper has been accepted for presentation at the 2017 meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco.

Conflicts of Interest For the other authors, none were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.USDHHS . The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . WHO Global Report: Mortality Attributable to Tobacco. WHO Press; Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helleberg M, Afzal S, Kronborg G, et al. Mortality attributable to smoking among HIV-1-infected individuals: A nationwide, population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:727–34. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park LS, Hernandez-Ramirez RU, Silverberg MJ, et al. Prevalence of non-HIV cancer risk factors in persons living with HIV/AIDS: A meta-analysis. AIDS. 2016;30(2):273–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ande A, McArthur C, Ayuk L, et al. Effect of mild-to-moderate smoking on viral load, cytokines, oxidative stress, and cytochrome P450 enzymes in HIV-infected individuals. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0122402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De P, Farley A, Lindson N, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Influence of smoking cessation on incidence of pneumonia in HIV. BMC Med. 2013;11:15. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calvo M, Laguno M, Martinez M, Martinez E. Effects of tobacco smoking on HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Rev. 2015;17(1):47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverberg MJ, Lau B, Achenbach CJ, et al. Cumulative incidence of cancer among persons with HIV in North America: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(7):507–18. doi: 10.7326/M14-2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helleberg M, May MT, Ingle SM, et al. Smoking and life expectancy among HIV-infected individuals on antiretroviral therapy in Europe and North America. AIDS. 2015;29(2):221–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aliyu MH, Weldeselasse H, August EM, et al. Cigarette smoking and fetal morbidity outcomes in a large cohort of HIV-infected mothers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):177–84. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calvet GA, Grinsztejn BG, Quintana Mde S, et al. Predictors of early menopause in HIV-infected women: A prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(6):765.e1–765.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suy A, Martinez E, Coll O, et al. Increased risk of pre-eclampsia and fetal death in HIV-infected pregnant women receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2006;20(1):59–66. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198090.70325.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vidrine DJ, Arduino RC, Gritz ER. The effects of smoking abstinence on symptom burden and quality of life among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(9):659–66. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benard A, Mercie P, Alioum A, et al. Bacterial pneumonia among HIV-infected patients: decreased risk after tobacco smoking cessation. ANRS CO3 Aquitaine Cohort, 2000-2007. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(1):e8896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petoumenos K, Worm S, Reiss P, et al. Rates of cardiovascular disease following smoking cessation in patients with HIV infection: Results from the D:A:D study. HIV Med. 2011;12(7):412–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamal A, King BA, Neff LJ, et al. Current cigarette smoking among adults — United States, 2005–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(44):1205–11. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6544a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CDC Tobacco Product Use Among Adults — United States, 2012–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(25):542–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou P, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1107–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendelsohn C. Women who smoke: A review of the evidence. Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39:403–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith PH, Kasza K, Hyland A, et al. Gender differences in medication use and cigarette smoking cessation: Results from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(4):463–72. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bohadana A, Nilsson F, Rasmussen T, et al. Gender differences in quit rates following smoking cessation with combination nicotine therapy: Influence of baseline smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(1):111–6. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000060482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wetter DW, Kenford SL, Smith SS, et al. Gender differences in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(4):555–62. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinberger AH, Pilver CE, Mazure CM, et al. Stability of smoking status in the U.S. population: A longitudinal investigation. Addiction. 2014;109(9):1541–53. doi: 10.1111/add.12647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarvis MJ, Cohen JE, Delnevo CD, et al. Dispelling myths about gender differences in smoking cessation: Population data from the USA, Canada, and Britain. Tob Control. 2013;22(5):356–60. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikkelsen SS, Dalum P, Skov-Ettrup LS, et al. What characterises smokers who quit without using help? A study of users and non-users of cessation support among successful ex-smokers. Tob Control. 2015;24:556–61. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinberger AH, Smith PH, Kaufman M, et al. Consideration of sex in clinical trials of transdermal nicotine patch: A systematic review. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;22(5):373–83. doi: 10.1037/a0037692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perkins KA, Scott J. Sex differences in long-term smoking cessation rates due to nicotine patch. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1245–51. doi: 10.1080/14622200802097506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith PH, Weinberger AH, Zhang J, et al. Sex differences in smoking cessation pharmacotherapy comparative efficacy: A network meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw144. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw144 [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benowitz NL, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Swan GE, et al. Female sex and oral contraceptive use accelerate nicotine metabolism. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79(5):480–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leventhal AM, Walters AJ, Boyd S, et al. Gender differences in acute tobacco withdrawal: Effects on subjective, cognitive, and physiological measures. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15(1):21–36. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pang RD, Leventhal AM. Sex differences in negative affect and lapse behavior during active tobacco abstinence: A laboratory study. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;21(4):269–76. doi: 10.1037/a0033429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piasecki TM, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, et al. Smoking withdrawal dynamics: III. Correlates of withdrawal heterogeneity. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;11(4):276–85. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.4.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKee SA, O'Malley SS, Salovey P, et al. Perceived risks and benefits of smoking cessation: Gender-specific predictors of motivation and treatment outcome. Addict Behav. 2005;30(3):423–35. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vidrine DJ. Cigarette smoking and HIV/AIDS: Health implications, smoker characteristics, and cessation strategies. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(Suppl A):3–13. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3_supp.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Webb MS, Vanable PA, Carey MP, et al. Cigarette smoking among HIV+ men and women: Examining health, substance use, and psychosocial correlates across the smoking spectrum. J Behav Med. 2007;30(5):371–83. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9112-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfgang V. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the Metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mdodo R, Frazier EL, Dube SR, et al. Cigarette smoking prevalence among adults with HIV compared with the general adult population in the United States: Cross-sectional surveys. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(5):335–44. doi: 10.7326/M14-0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benard A, Bonnet F, Tessier JF, et al. Tobacco addiction and HIV infection: toward the implementation of cessation programs. ANRS CO3 Aquitaine Cohort. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(7):458–68. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tesoriero JM, Gieryic SM, Carrascal A, et al. Smoking among HIV positive New Yorkers: Prevalence, frequency, and opportunities for cessation. AIDS & Behavior. 2010;14(4):824–35. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shuter J, Pearlman BK, Stanton CA, et al. Gender differences among smokers living with HIV. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2016;15(5):412–417. doi: 10.1177/2325957416649439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tron L, Lert F, Spire B, et al. Tobacco smoking in HIV-infected versus general population in France: Heterogeneity across the various groups of people living with HIV. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e107451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gritz ER, Vidrine DJ, Lazev AB, et al. Smoking behavior in a low-income multiethnic HIV/AIDS population. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(1):71–7. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Batista Jd, Militao de Albuquerque MdeF, Ximenes RA, et al. Prevalence and socioeconomic factors associated with smoking in people living with HIV by sex, in Recife, Brazil. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2013;16(2):432–43. doi: 10.1590/S1415-790X2013000200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neumann T, Woiwod T, Neumann A, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and probability for cardiovascular events in HIV-infected patients. Part II: gender differences. Eur J Med Res. 2004;9(2):55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mamary EM, Bahrs D, Martinez S. Cigarette smoking and the desire to quit among individuals living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2002;16(1):39–42. doi: 10.1089/108729102753429389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beachler DC, Weber KM, Margolick JB, et al. Risk factors for oral HPV infection among a high prevalence population of HIV-positive and at-risk HIV-negative adults. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(1):122–33. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cui Q, Carruthers S, McIvor A, et al. Effect of smoking on lung function, respiratory symptoms and respiratory diseases amongst HIV-positive subjects: a cross-sectional study. AIDS Res Ther. 2010;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collins RL, Kanouse DE, Gifford AL, et al. Changes in health-promoting behavior following diagnosis with HIV: Prevalence and correlates in a national probability sample. Health Psychol. 2001;20(5):351–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y, Chen X, Li X, et al. Cigarette smoking among Chinese PLWHA: An exploration of changes in smoking after being tested HIV positive. AIDS Care. 2016;28(3):365–9. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1090536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pacek LR, Latkin C, Crum RM, et al. Interest in quitting and lifetime quit attempts among smokers living with HIV infection. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;138:220–4. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peretti-Watel P, Garelik D, Baron G, et al. Smoking motivations and quitting motivations among HIV-infected smokers. Antivir Ther. 2009;14(6):781–7. doi: 10.3851/IMP1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amiya RM, Poudel KC, Poudel-Tandukar K, et al. Physicians are a key to encouraging cessation of smoking among people living with HIV/AIDS: A cross-sectional study in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:677. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shapiro AE, Tshabangu N, Golub JE, et al. Intention to quit smoking among human immunodeficiency virus infected adults in Johannesburg, South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(1):140–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shuter J, Moadel AB, Kim RS, et al. Self-efficacy to quit in HIV-infected smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(11):1527–31. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shuter J, Bernstein SL, Moadel AB. Cigarette smoking behaviors and beliefs in persons living with HIV/AIDS. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36(1):75–85. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.36.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vijayaraghavan M, Penko J, Vittinghoff E, et al. Smoking behaviors in a community-based cohort of HIV-infected indigent adults. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(3):535–43. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0576-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Encrenaz G, Benard A, Rondeau V, et al. Determinants of smoking cessation attempts among HIV-infected patients results from a hospital-based prospective cohort. Curr HIV Res. 2010;8(3):212–7. doi: 10.2174/157016210791111089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schäfer J, Young J, Bernasconi E, et al. Predicting smoking cessation and its relapse in HIV-infected patients: The Swiss HIV Cohort Study. HIV Med. 2015;16:3–14. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tami-Maury I, Vidrine DJ, Fletcher FE, et al. Poly-tobacco use among HIV-positive smokers: implications for smoking cessation efforts. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(12):2100–6. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Browning KK, Wewers ME, Ferketich AK, et al. Adherence to tobacco dependence treatment among HIV-infected smokers. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(3):608–21. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1059-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shuter J, Morales D, Considine-Dunn S, et al. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a web-based smoking cessation intervention for HIV infected smokers: A randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(1):59–66. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shelley D, Tseng TY, Gonzalez M, et al. Correlates of adherence to varenicline among HIV+ smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(8):968–74. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moadel AB, Bernstein SL, Mermelstein RJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a tailored group smoking cessation intervention for HIV-infected smokers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(2):208–15. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182645679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cropsey KL, Hendricks PS, Jardin B, et al. A pilot study of screening, brief intervention, and referral for treatment (SBIRT) in non-treatment seeking smokers with HIV. Addict Behav. 2013;38(10):2541–6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Dios MA, Stanton CA, Cano MÁ, et al. The influence of social support on smoking cessation treatment adherence among HIV+ smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):1126–33. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chew D, Steinberg MB, Thomas P, et al. Evaluation of a smoking cessation program for HIV infected individuals in an urban HIV clinic: Challenges and lessons learned. AIDS Res Treat. 2014;2014:237834. doi: 10.1155/2014/237834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Elzi L, Spoerl D, Voggensperger J, et al. A smoking cessation programme in HIV-infected individuals: A pilot study. Antivir Ther. 2006;11(6):787–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):102–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.CDC Quitting smoking among adults---United States, 2001-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(44):1513–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McMillen RC, Gottlieb MA, Whitmore Shaefer RM, et al. Trends in electronic cigarette use among U.S. adults: Use is increasing in both smokers and nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(10):1195–1202. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ledgerwood DM, Yskes R. Smoking cessation for people living with HIV/AIDS: A literature review and synthesis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(12):2177–2184. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nahvi S, Cooperman NA. Review: The need for smoking cessation among HIV-positive smokers. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(Suppl A):14–27. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3_supp.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moscou-Jackson G, Commodore-Mensah Y, Farley J, et al. Smoking-cessation interventions in people living with HIV infection: A systematic review. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(1):32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pool ERM, Dogar O, Lindsay RP, et al. Interventions for tobacco use cessation in people living with HIV and AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD011120. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011120.pub2. Art. No., doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011120.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Piasecki TM. Relapse to smoking. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(2):196–215. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Turner J, Page-Shafer K, Chin DP, et al. Adverse impact of cigarette smoking on dimensions of health-related quality of life in persons with HIV infection. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2001;15(12):615–24. doi: 10.1089/108729101753354617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miguez-Burbano MJ, Ashkin D, Rodriguez A, et al. Increased risk of Pneumocystis carinii and community-acquired pneumonia with tobacco use in HIV disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9(4):208–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Benard A, Tessier JF, Rambeloarisoa J, et al. HIV infection and tobacco smoking behaviour: prospects for prevention? ANRS CO3 Aquitaine Cohort, 2002. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(4):378–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Glass TR, Ungsedhapand C, Wolbers M, et al. Prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected patients over time: The Swiss HIV Cohort Study. HIV Med. 2006;7(6):404–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mbulaiteye SM, Atkinson JO, Whitby D, et al. Risk factors for human herpes virus 8 seropositivity in the AIDS Cancer Cohort Study. J Clin Virol. 2006;35(4):442–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carr A, Grund B, Neuhaus J, et al. Asymptomatic myocardial ischaemia in HIV-infected adults. AIDS. 2008;22(2):257–67. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f20a77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.De Socio GV, Parruti G, Quirino T, et al. Identifying HIV patients with an unfavorable cardiovascular risk profile in the clinical practice: results from the SIMONE study. J Infect. 2008;57(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duval X, Baron G, Garelik D, et al. Living with HIV, antiretroviral treatment experience and tobacco smoking: Results from a multisite cross-sectional study. Antivir Ther. 2008;13(3):389–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jacobson DL, Spiegelman D, Knox TK, et al. Evolution and predictors of change in total bone mineral density over time in HIV-infected men and women in the nutrition for healthy living study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(3):298–308. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181893e8e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Murdoch DM, Napravnik S, Eron JJ, Jr, et al. Smoking and predictors of pneumonia among HIV-infected patients receiving care in the HAART era. Open Respir Med J. 2008;2:22–8. doi: 10.2174/1874306400802010022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Desalu OO, Oluboyo PO, Olokoba AB, et al. Prevalence and determinants of tobacco smoking among HIV patients in North Eastern Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2009;38(2):103–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jaquet A, Ekouevi DK, Aboubakrine M, et al. Tobacco use and its determinants in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in West African countries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13(11):1433–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Webb MS, Vanable PA, Carey MP, et al. Medication adherence in HIV-infected smokers: The mediating role of depressive symptoms. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(Suppl 3):94–105. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3_supp.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Aboud M, Elgalib A, Pomeroy L, et al. Cardiovascular risk evaluation and antiretroviral therapy effects in an HIV cohort: implications for clinical management: The CREATE 1 study. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(9):1252–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02424.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cahn P, Leite O, Rosales A, et al. Metabolic profile and cardiovascular risk factors among Latin American HIV-infected patients receiving HAART. Braz J Infect Dis. 2010;14(2):158–66. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702010000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lifson AR, Neuhaus J, Arribas JR, et al. Smoking-related health risks among persons with HIV in the Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1896–903. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.188664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brion JM, Rose CD, Nicholas PK, et al. Unhealthy substance-use behaviors as symptom-related self-care in persons with HIV/AIDS. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13(1):16–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Collazos J, Carton JA, Asensi V. Gender differences in liver fibrosis and hepatitis C virus-related parameters in patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus. Curr HIV Res. 2011;9(5):339–45. doi: 10.2174/157016211797635982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Petoumenos K, Worm S, Reiss P, et al. Rates of cardiovascular disease following smoking cessation in patients with HIV infection: Results from the D:A:D study(*). HIV Med. 2011;12(7):412–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pines H, Koutsky L, Buskin S. Cigarette smoking and mortality among HIV-infected individuals in Seattle, Washington (1996-2008). AIDS Beh. 2011;15(1):243–51. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9682-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Stewart DW, Jones GN, Minor KS. Smoking, depression, and gender in low-income African Americans with HIV/AIDS. Behav Med. 2011;37(3):77–80. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2011.583946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chander G, Stanton C, Hutton HE, et al. Are smokers with HIV using information and communication technology? Implications for behavioral interventions. AIDS Beh. 2012;16(2):383–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9914-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kristoffersen US, Lebech A-M, Mortensen J, et al. Changes in lung function of HIV-infected patients: A 4.5-year follow-up study. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2012;32(4):288–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2012.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Iliyasu Z, Gajida AU, Abubakar IS, et al. Patterns and predictors of cigarette smoking among HIV-infected patients in northern Nigeria. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23(12):849–52. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2012.012001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Villanti A, German D, Sifakis F, et al. Smoking, HIV status, and HIV risk behaviors in a respondent-driven sample of injection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland: The BeSure Study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24(2):132–47. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bryant VE, Kahler CW, Devlin KN, et al. The effects of cigarette smoking on learning and memory performance among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2013;25(10):1308–16. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.764965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Buchacz K, Baker RK, Palella FJ, Jr, et al. Disparities in prevalence of key chronic diseases by gender and race/ethnicity among antiretroviral-treated HIV-infected adults in the US. Antivir Ther. 2013;18(1):65–75. doi: 10.3851/IMP2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shirley DK, Kesari RK, Glesby MJ. Factors associated with smoking in HIV-infected patients and potential barriers to cessation. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(11):604–12. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Siconolfi DE, Halkitis PN, Barton SC, et al. Psychosocial and demographic correlates of drug use in a sample of HIV-positive adults ages 50 and older. Prev Sci. 2013;14(6):618–27. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Waweru P, Anderson R, Steel H, et al. The prevalence of smoking and the knowledge of smoking hazards and smoking cessation strategies among HIV- positive patients in Johannesburg, South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2013;103(11):858–60. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.7388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Aichelburg MC, Mandorfer M, Tittes J, et al. The association of smoking with IGRA and TST results in HIV-1-infected subjects. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(6):709–16. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Luo X, Duan S, Duan Q, et al. Tobacco use among HIV-infected individuals in a rural community in Yunnan Province, China. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134:144–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Miguez-Burbano MJ, Vargas M, Quiros C, et al. Menthol cigarettes and the cardiovascular risks of people living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(5):427–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pacek LR, Latkin C, Crum RM, et al. Current cigarette smoking among HIV-positive current and former drug users: Associations with individual and social characteristics. AIDS Beh. 2014;18(7):1368–77. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0663-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pacek LR, Harrell PT, Martins SS. Cigarette smoking and drug use among a nationally representative sample of HIV-positive individuals. Am J Addict. 2014;23:582–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2014.12145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Samperiz G, Guerrero D, Lopez M, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for pulmonary abnormalities in HIV-infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2014;15(6):321–9. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Torres TS, Luz PM, Derrico M, et al. Factors associated with tobacco smoking and cessation among HIV-infected individuals under care in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e115900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ahlstrom MG, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Legarth R, et al. Smoking and renal function in people living with human immunodeficiency virus: A Danish nationwide cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:391–9. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S83530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cioe PA, Baker J, Kojic EM, et al. Elevated soluble CD14 and lower d-dimer are associated with cigarette smoking and heavy episodic alcohol use in persons living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(4):400–5. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Estrada V, Bernardino JI, Masia M, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and lifetime risk estimation in HIV-infected patients under antiretroviral treatment in Spain. HIV Clin Trials. 2015;16(2):57–65. doi: 10.1179/1528433614Z.0000000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Moreno JL, Catley D, Lee HS, Goggin K. The relationship between ART adherence and smoking status among HIV+ individuals. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(4):619–25. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0978-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nguyen NP, Tran BX, Hwang LY, et al. Prevalence of cigarette smoking and associated factors in a large sample of HIV-positive patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Vietnam. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0118185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.O'Cleirigh C, Valentine SE, Pinkston M, et al. The unique challenges facing HIV-positive patients who smoke cigarettes: HIV viremia, ART adherence, engagement in HIV care, and concurrent substance use. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(1):178–85. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0762-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Rasmussen LD, Helleberg M, May MT, et al. Myocardial infarction among Danish HIV-infected individuals: population-attributable fractions associated with smoking. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(9):1415–23. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zyambo CM, Willig JH, Cropsey KL, et al. Factors associated with smolking status among HIV-positive patients in routine clinical care. J AIDS Clin Res. 2015;6:7. doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Marando F, Gualberti G, Costanzo AM, et al. Discrepancies between physician's perception of depression in HIV patients and self-reported CES-D-20 assessment: The DHIVA study. AIDS Care. 2016;28(2):147–59. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1080794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Muyanja D, Muzoora C, Muyingo A, et al. High prevalence of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease risk among people with HIV on stable ART in southwestern Uganda. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(1):4–10. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Parhami I, Fong TW, Siani A, Carlotti C, Khanlou H. Documentation of psychiatric disorders and related factors in a large sample population of HIV-positive patients in California. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2792–801. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0386-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Pence BW, Miller WC, Whetten K, et al. Prevalence of DSM-IV-defined mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in an HIV clinic in the southeastern United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:298–306. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219773.82055.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Smith PH, Mazure CM, McKee SA. Smoking and mental illness in the US population. Tob Control. 2014;23:e147–e53. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Weinberger AH, Funk AP, Goodwin RD. A review of epidemiologic research on smoking behavior among persons with alcohol and illicit substance use disorders. Prev Med. 2016;92:148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]