Abstract

Objective

To estimate preterm birth risk among infants of HIV-infected women in Lilongwe, Malawi according to maternal antiretroviral therapy (ART) status and initiation time under Option B+.

Design

Retrospective cohort study of HIV-infected women delivering at ≥27 weeks of gestation, April 2012–November 2015. Among women on ART at delivery, we restricted our analysis to those who initiated ART before 27 weeks of gestation.

Methods

We defined preterm birth as a singleton live birth at ≥27 and <37 weeks of gestation, with births at <32 weeks classified as extremely to very preterm. We used log-binomial models to estimate risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between ART and preterm birth.

Results

Among 3074 women included in our analyses, 731 preterm deliveries were observed (24%). Overall preterm birth risk was similar in women who had initiated ART at any point before 27 weeks and those who never initiated ART (RR = 1.14; 95% CI: 0.84 – 1.55), but risk of extremely to very preterm birth was 2.33 (1.39 – 3.92) times as great in those who never initiated ART compared to those who did at any point before 27 weeks. Among women on ART before delivery, ART initiation before conception was associated with the lowest preterm birth risk.

Conclusions

ART during pregnancy was not associated with preterm birth, and it may in fact be protective against severe adverse outcomes accompanying extremely to very preterm birth. As pre-conception ART initiation appears especially protective, long-term retention on ART should be a priority to minimize preterm birth in subsequent pregnancies.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, preterm birth, premature, HIV, Option B, PMTCT

Introduction

Preterm birth, often defined as birth before 37 weeks of gestation,1 is the second-leading cause of death in children under five years,2 and accounts for 75% of all perinatal mortality worldwide.3,4 Of the estimated 15 million infants born preterm in 2010, more than one million died as a result of prematurity.1–4 In sub-Saharan Africa, about 12% of live births are preterm, with Malawi registering the highest preterm birth prevalence worldwide (18%).5

HIV is also endemic in sub-Saharan Africa, with 59% of all prevalent HIV infections occurring among women.6 Prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) is thus a major public health priority. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV-infected women during pregnancy can virtually eliminate the risk of vertical HIV transmission,7–9 with the additional, important benefit of reduced maternal morbidity and mortality.10–13

In July 2011, Malawi became the first country to adopt a strategy of universal life-long ART for pregnant and breastfeeding women regardless of HIV disease stage or CD4 count.14 The scale-up of this approach, called “Option B+”, is expected to help bring an end to new pediatric HIV infections and substantially improve maternal health in settings with high HIV burdens.15 Since the introduction of Option B+ in Malawi, the number of pregnant or breastfeeding women on ART has increased dramatically,16 and in 2013 the World Health Organization recommended it for all countries with a generalized HIV epidemic.17

Despite the clear benefits of Option B+ for maternal health and the prevention of vertical HIV transmission, the effects of ART exposure during pregnancy on fetal development and birth outcomes are still unclear.18–24 In particular, few studies have examined the relationship between the timing of maternal ART initiation and preterm delivery.18,25–29 In this study, we used data from the maternity unit of a large, urban hospital in Malawi to estimate preterm birth risk among HIV-infected women according to maternal ART status and time of ART initiation in the Option B+ era.

Methods

Study design, setting, and population

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data collected at delivery from HIV-infected pregnant women for whom the date of last menstrual period (LMP) was available and who delivered a singleton live birth at Bwaila Hospital in Lilongwe, Malawi from April 1, 2012 through November 15, 2015. Study data were obtained from a point-of-care electronic medical record system (POC-EMRS) developed by Baobab Health Trust and hosted at the hospital. All records in the POC-EMRS were entered directly by a health care worker at the time of delivery. Information about HIV status and ART (for HIV-infected women) was cross-checked with documentation in the mother’s personal health passport, a government-issued document containing information on general history, diagnoses, treatments, antenatal consultations, and deliveries.

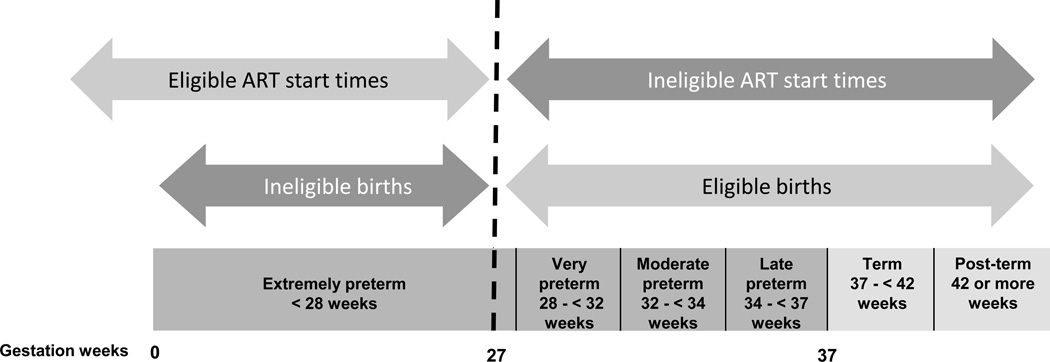

ART duration during pregnancy is intrinsically linked to length of gestation (and thus preterm birth): women initiating ART later in pregnancy are necessarily closer to reaching term, and are therefore less likely to experience preterm birth. In an attempt to remove this potentially confounding relationship from our analysis, we constructed our study population such that the risk period for the outcome (preterm birth) was entirely separate from the eligible ART start times. Specifically, we restricted our analysis to women who: a) delivered on or after 27 weeks of gestation, and b) either started ART before 27 weeks or did not receive ART at all before delivery (Figure 1). In other words, we chose a cut-off of 27 weeks to define the start of the risk period for preterm birth. This start point is at the upper end of values (which range from 20 to 28 weeks) that have been used in other settings;1 this choice allowed us to minimize the number of women initiating ART during pregnancy that we would need to exclude in order to keep ART start times separate from the preterm risk period. Women with missing information on the main exposure (ART use) were also excluded.

Figure 1.

Study eligibility on the basis of maternal ART start time and gestational age at birth

This study was approved by the National Health Sciences Research Committee (NHSRC) of Malawi and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Variable definitions and classifications

HIV Status

Each woman’s HIV status was determined upon maternity unit admission. Women whose health passports indicated prior HIV-positive test results were considered to be HIV-infected; women without health passport documentation of HIV-positive status underwent HIV testing. Women found to be HIV-infected based on either the health passport or testing at delivery were recorded as such in the database and were eligible for study inclusion.

Main outcome – preterm birth

Preterm birth status was based on gestational age at delivery, calculated as the difference between delivery date and the LMP date recorded in the health passport during the first antenatal visit. We defined preterm birth as birth on or after 27 weeks and before 37 weeks of gestation. Births occurring at 37+ weeks of gestation were considered full term.1

Main exposure – ART

ART status and timing of initiation were determined at delivery according to maternal interview and information recorded in the health passport. Eligible HIV-infected women with no history of ART use before delivery comprised the “never initiated” group in our analysis. Women whose health passports indicated ART initiation at or after 27 weeks of gestation (but before delivery) were excluded from the analysis, as their ART exposure during pregnancy began after the start of the preterm birth risk period. The remaining ART-exposed women were assigned to one of three categories according to timing of ART initiation: 1) before pregnancy (on ART at conception), 2) during the 1st trimester, or 3) during the 2nd trimester (specifically, the portion of the 2nd trimester <27 weeks).

Confounders

We used a directed acyclic graph (DAG),30,31 an epidemiological tool for encoding relationships among variables in studies of causal effects, to identify potential confounders. This tool helps to ensure that potential confounders are associated with both the exposure and the outcome, but are not on the causal pathway between them. In developing a DAG with variables in our database, we identified mother’s education, age, and parity as potential confounders for inclusion in the analysis. Based on the functional form of the relationship between each confounder and the outcome, we modeled mother’s age as continuous and parity as ordinal. We used a manual, backward elimination, change-in-estimate strategy at a 10% retention threshold to assess the necessity of including each confounder in the final model.32 We were unable to assess education as a confounder, as values for this variable were missing from 95% of records.

Statistical Analyses

We used Fisher exact tests to test differences in proportions between groups, and t-tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test differences in means as appropriate. We used log-binomial regression models to estimate unadjusted and adjusted risk ratios (uRRs and aRRs, respectively) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the association between ART exposure status and preterm birth (with those who were on ART as referent), and ART initiation time and preterm birth (with those initiating before conception as referent).

In sub-analyses, we considered three preterm birth sub-categories: extremely to very preterm (27 to < 32 weeks), moderate preterm (32 to < 34 weeks), and late preterm (34 to <37 weeks).1 In the first sub-analysis, we treated extremely to very preterm births (versus full term) as the outcome, excluding moderate to late preterm births. In a second sub-analysis, we treated moderate to late preterm births (again versus full term) as the outcome, this time excluding extremely to very preterm births. In a third sub-analysis, we dichotomized the outcome as <34 weeks versus ≥34 weeks (extremely to moderate preterm vs. late preterm or full term), because births before 34 weeks’ gestational age require advanced neonatal support, and their relationship with ART status and initiation time is thus of high clinical interest in this setting.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

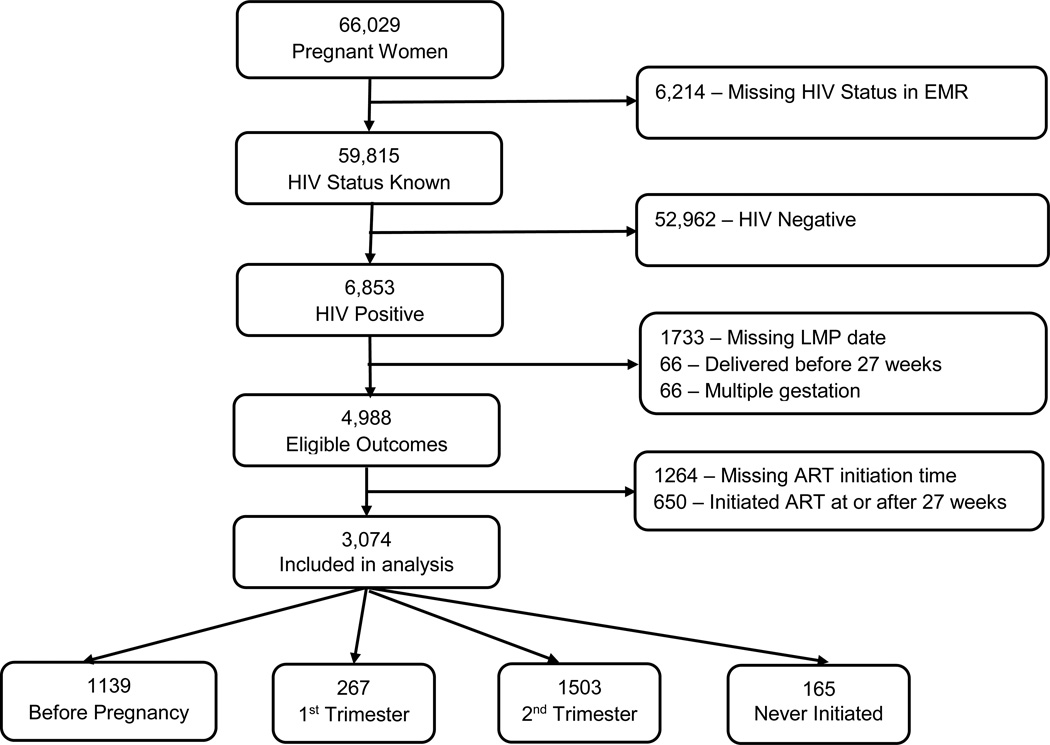

Among 66,029 women who delivered in the maternity ward at Bwaila Hospital during the study period, 6,853 women (10.4%) were known to be HIV-infected (Figure 2). Of these, 1733 (25.2%) were excluded due to missing LMP, 66 (1.0%) due to delivery before 27 weeks, and 66 (1.0%) due to multiple gestations. Among the women who were excluded for having delivered before 27 weeks, 17 had missing ART initiation time, 22 started ART before conception, 21 started ART during pregnancy, and six were not on ART, including one stillbirth. The remaining 4,988 HIV-infected women (72.8%) had singleton live births at 27+ weeks of gestation and thus had eligible outcomes. After excluding 1264 women (25.3%) with missing ART initiation time and 650 (13.0%) who initiated ART at or after 27 weeks, 3,074 women were included in the analyses. Compared to the 3,724 women who had ART initiation time available, women who were excluded due to missing ART initiation time were on average slightly older and had similar parity, but a slightly lower percentage of preterm infants (19.4% vs. 22.1%, Supplemental Table 1). Among included women, most had initiated ART before pregnancy (N=1139, 37.0%) or during the second trimester (N=1503, 48.9%). Only 5.4% had not initiated ART before delivery (N=165).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the inclusion criteria for the women included in the analysis

On average, women who did not start ART before delivery were younger than those who had received ART during pregnancy, and age at delivery increased with earlier ART initiation times (p < 0.001) (Table 1). The distribution of parity was different across the ART exposure categories (p < 0.001), and mean gestational age at delivery was similar between those who never initiated ART and those who were on ART, regardless of ART initiation time (p = 0.05). A total of 731 preterm births were observed during the study period (risk = 24%; 95% CI: 22% – 25%), with 149 being extremely to very preterm, 94 moderate preterm, and 488 late preterm. Women who delivered preterm babies were on average younger than those who delivered full term babies (mean age = 27.6 vs 28.4, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population

| Birth Status | ART initiation time during pregnancy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Preterm N =731 |

Full Term N =2343 |

Before pregnancy N =1139 |

1st trimester N =267 |

2nd trimester* N=1503 |

Never initiated N=165 |

| Mother’s age (mean, SD) | 27.6 (5.6) | 28.4 (5.8) | 30.4 (5.4) | 27.2 (5.4) | 26.9 (5.5) | 25.6 (5.5) |

| Gestation weeks at delivery (mean, SD) |

34.0 (2.2) | 39.4 (1.3) | 38.3 (2.7) | 37.9 (2.9) | 38.1 (2.8) | 38.0 (3,3) |

| Parity [N (%)] | ||||||

| Nulliparity | 20 (3.3) | 46 (2.3) | 12 (1.1) | 9 (4.1) | 40 (3.4) | 5 (4.1) |

| Primiparity (1 child) | 163 (26.9) | 567 (28.6) | 239 (22.3) | 64 (29.2) | 384 (32.7) | 43 (35.5) |

| Low Multiparity (2–4 children) | 394 (65.0) | 1243 (62.8) | 739 (68.9) | 140 (63.9) | 695 (59.2) | 63 (52.1) |

| Grand multiparity (≥ 5 children) | 29 (4.8) | 124 (6.3) | 82 (7.7) | 6 (2.7) | 55 (6.7) | 10 (8.3) |

before 27 weeks

Overall, preterm birth risk was similar in women who never initiated ART compared to those who had initiated ART at any point before delivery (24.8% vs. 23.7%; aRR = 1.14; 95% CI: 0.84 – 1.55) (Table 2). Among women who initiated ART before delivery, preterm risk was lowest in those starting ART before conception, with aRRs for those initiating during the 1st and 2nd trimester of 1.31 (95% CI: 1.03 – 1.68) and 1.17 (0.99 – 1.37), respectively. Preterm risk was also elevated in those never initiating ART vs. those starting ART before pregnancy (aRR =1.27; 95% CI: 0.92 – 1.76).

Table 2.

Associations between ART status and timing of initiation with preterm birth

| Preterm (N=731) N (%) |

Full Term (N=2343) N (%) |

Unadjusted RR (95% CI) |

Adjusted RR† (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ART initiation status | ||||

| On ART | 690 (94.4) | 2219 (94.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Never Initiated | 41 (5.6) | 124 (5.3) | 1.05 (0.80, 1.38) | 1.14 (0.84, 1.55) |

| ART initiation time | ||||

| Before Pregnancy | 235 (32.2) | 904 (38.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1st Trimester | 77 (10.5) | 190 (8.1) | 1.40 (1.12, 1.74) | 1.31 (1.03, 1.68) |

| 2nd Trimester* | 378 (51.7) | 1125 (48.0) | 1.22 (1.06, 1.41) | 1.17(0.99, 1.37) |

| Never initiated | 41 (5.6) | 124 (5.3) | 1.20 (0.90, 1.61) | 1.27 (0.92, 1.76) |

Adjusted for mother’s age and parity

before 27 weeks

In sub-analyses, we found a strong association between no ART use during pregnancy and extremely to very preterm birth vs. full term birth (aRR = 2.33; 95% CI: 1.39 – 3.92) (Table 3). Among women who started ART before delivery, risk of extremely to very preterm birth was elevated in those starting ART in the first trimester (aRR = 1.30; 95% CI: 0.72–2.36) but not the second trimester (aRR=1.00; 95% CI=0.68–1.48) compared with women starting before conception. Not starting ART before delivery more than doubled the risk of extremely to very preterm birth compared with starting ART before pregnancy (aRR = 2.41; 95% CI: 1.36 – 4.24).

Table 3.

Associations between ART status and timing of initiation with alternate preterm categorizations

| Extremely to Very Preterm* (N = 149) N (%) |

Full Term‡ (N = 2343) N (%) |

Unadjusted RR (95% CI) |

Adjusted RR§ (95% CI) |

|

| ART initiation status | ||||

| On ART | 133 (86.3) | 2219 (94.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Never Initiated | 16 (10.7) | 124 (5.3) | 2.02 (1.24, 3.30) | 2.33 (1.39, 3.92) |

| ART initiation time | ||||

| Before Pregnancy | 50 (33.6) | 904 (38.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1st Trimester | 14 (9.4) | 190 (8.1) | 1.31 (0.74, 2.32) | 1.30 (0.72, 2.36) |

| 2nd Trimester** | 69 (46.3) | 1125 (48.0) | 1.10 (0.77, 1.57) | 1.00 (0.68, 1.48) |

| Never initiated | 16 (10.7) | 124 (5.3) | 2.18 (1.28, 3.75) | 2.41 (1.36, 4.24) |

| Moderate to late Preterm† (N = 582) N (%) |

Full Term‡ (N = 2343) N (%) |

|||

| ART initiation status | ||||

| On ART | 557 (95.7) | 2219 (94.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Never Initiated | 25 (4.3) | 124 (5.3) | 0.84 (0.58, 1.20) | 0.86 (0.55, 1.34) |

| ART initiation time | ||||

| Before Pregnancy | 185 (31.8) | 904 (38.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1st Trimester | 63 (10.8) | 190 (8.1) | 1.47 (1.14, 1.88) | 1.36 (1.02, 1.82) |

| 2nd Trimester** | 309 (53.1) | 1125 (48.0) | 1.27 (1.08, 1.49) | 1.23 (1.02, 1.48) |

| Never initiated | 25 (4.3) | 124 (5.3) | 0.99 (0.68, 1.45) | 0.99 (0.63, 1.57) |

| < 34 weeks (N = 243) N (%) |

≥ 34 weeks (N = 2831) N (%) |

Unadjusted RR (95% CI) |

Adjusted RR§ (95% CI) |

|

| ART initiation status | ||||

| On ART | 227 (93.4) | 2682 (94.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Never Initiated | 16 (6.6) | 149 (5.3) | 1.24 (0.77, 2.01) | 1.42 (0.85, 2.36) |

| ART initiation time | ||||

| Before Pregnancy | 83 (34.2) | 1056 (37.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1st Trimester | 24 (9.8) | 243 (8.6) | 1.23 (0.80, 1.90) | 1.24 (0.79, 1.96) |

| 2nd Trimester** | 120 (49.4) | 1383 (48.9) | 1.10 (0.84, 1.43) | 1.02 (0.76, 1.37) |

| Never initiated | 16 (6.6) | 149 (5.3) | 1.33 (0.80, 2.22) | 1.47 (0.86, 2.52) |

Extremely to very preterm: 27 to < 32 gestation weeks

Moderate to late preterm: 32 to < 37 gestation weeks

Full term: ≥ 37 gestation weeks

Adjusted for mother’s age and parity

before 27 weeks

Risk of moderate to late preterm (vs. full term) birth was similar in those not initiating ART before delivery and those who were on ART (aRR = 0.86; 95% CI: 0.55 – 1.34) (Table 3), but among those on ART at delivery, initiation in either the 1st trimester or 2nd trimester was associated with a higher risk of moderate to late preterm birth compared with ART initiation before conception.

Finally, we found suggestion that not starting ART before delivery increased risk of birth at less than 34 weeks’ gestation, although the estimate was imprecise (aRR = 1.42; 95% CI: 0.85 – 2.36) (Table 3). Among those initiating ART before delivery, risk of birth before 34 weeks was similar among those starting ART before pregnancy and those starting during the second trimester, but the point estimate for ART initiation during the 1st trimester suggested increased risk. The point estimate comparing no ART to ART initiated before pregnancy also suggested increased risk, but this estimate was similarly imprecise.

Discussion

In this study of infants born to HIV-infected mothers in Malawi since the start of Option B+, we did not find a strong association between ART initiation before delivery and preterm birth overall. Importantly, we found ART to be quite strongly associated with a reduced risk of extremely to very preterm birth (birth between 27 and 32 weeks of gestation), and moderately associated with a reduction in preterm birth before 34 weeks. These results are encouraging because mortality increases as gestational age decreases, with only 30% of babies born between 28 and 32 weeks in low-income countries surviving.1 In general, ART initiation before conception was associated with better outcomes relative to ART non-use, particularly with respect to the more severe preterm birth outcomes. Among women who were on ART before delivery, initiation before conception or during the second trimester was associated with lower risk of the more severe preterm birth outcomes than was initiation during the first trimester.

Our findings related to early ART initiation and overall preterm birth risk are consistent with previous studies that have shown a protective effect of earlier maternal ART against preterm birth. A study of predominantly black African pregnant women delivering at a single hospital in London found a decreased odds of preterm delivery among women who conceived while receiving ART compared to women who received ART following conception.27 Results from a study in Malawi and Mozambique showed a protective effect of a longer course of ART during pregnancy against preterm birth, although the investigators did not differentiate between those starting ART before conception and those starting during pregnancy.28

Other studies have found ART initiation before pregnancy to be associated with increased preterm birth risk. In an analysis of abstracted obstetrical records at six sites in Botswana, women starting highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) before pregnancy had a higher odds of preterm delivery compared to HIV-infected women with no ART exposure and those initiating HAART or zidovudine monotherapy during pregnancy.20 Similarly, results from a prospective cohort study in Brazil found that starting ART before conception increased the odds of preterm birth, although the effect estimate was very imprecise.25 Most recently, a large prospective cohort study in Tanzania found that HAART before conception was associated with a higher risk of preterm birth overall and very preterm birth in particular.29 Importantly, however, the referent population in that study was women starting zidovudine monotherapy after 28 weeks of gestation, so these women (by virtue of the fact that their pregnancies had survived to at least 28 weeks) may have been at lower preterm risk than any of the groups to whom we compared our own women who initiated ART before conception. We also note that all of these prior studies were performed in the era when ART initiation for health and PMTCT was only available to those with advanced disease. Advanced maternal HIV is associated with increased preterm birth risk33 and these earlier findings may not be directly applicable to the Option B+ era in which lifelong ART is initiated during pregnancy regardless of HIV disease stage or CD4 count.

Findings around the relationship between preterm birth overall and any ART during pregnancy have been mixed. Preliminary results of the PROMISE trial,34 which randomized HIV-positive pregnant women with high CD4 counts to one of two triple ARV regimens vs. antepartum ZDV, found an association between the triple ARV arms and birth before 37 weeks, but not birth before 34 weeks. On the other hand, a recent study from South Africa reported significantly lower odds of preterm birth among women receiving any ART under Option B+ versus those not receiving ART.35 In general, heterogeneities across studies, particularly with respect to ART regimens, analytical choices around referent populations, and inclusion of women starting ART after preterm risk began, make direct comparison between our findings and those of previous studies difficult.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to provide evidence that ART initiation before conception is protective against preterm birth in the era of Option B+. As the Option B+ program matures and the proportion of women on lifelong ART following a prior pregnancy grows, we expect that increasing proportions of women will be on ART before conception. Our finding that preterm risk was lowest in this group suggests that preterm prevalence among HIV-infected mothers is likely to decrease as the time since Option B+ implementation increases. Our results also suggest that being on ART during pregnancy is protective against extremely to very preterm birth, regardless of time of ART initiation. These findings suggest that increased ART uptake in the Option B+ era could have a profound impact on preterm birth and neonatal mortality in developing countries where fertility rates are high, HIV is endemic, and advanced nursery facilities are not readily available.

Several mechanisms have been hypothesized for possible adverse effects of ART on birth outcomes. Specifically, it has been proposed that protease inhibitor (PI)-based ART could induce preterm birth by a cytokine-mediated regulation of the immune system through increased Th1 and decreased Th2 cytokines production.36,37 Women with recurrent pregnancy losses have been observed to have increased Th1 and decreased Th2 cytokines.38,39 Compared to non-PI-based ART, women on PI-based ART have a higher risk of having preterm birth.20,21 However, the same cytokine mechanism has been hypothesized to be protective against HIV disease progression.40,41 Women who are on established ART before conception may have a stabilized cytokine environment due to long exposure to ART, which can be one reason we observed ART initiation before pregnancy being protective against preterm birth. Additionally, the ART regimen used in Malawi, tenofovir/lamivudine/efavirenz (TDF/3TC/EFV), is not PI-based, which may explain the similar preterm birth risk we observed in women who initiated ART at any point before 27 weeks and those who never initiated ART.

Studies focusing on the association between ART exposure duration in utero and other fetal outcomes have also suggested that earlier ART is not detrimental. Earlier ART initiation during pregnancy was not associated with increased risk of stillbirth or low birthweight (LBW) in South Africa (with ART initiation dichotomized at < 28 weeks or ≥ 28 weeks of pregnancy),18 or with LBW in United States (with ART initiation dichotomized at ≤ 25 weeks or ≥ 32 weeks of gestation).24 A recent cohort analysis in Zambia among infants born at term also did not find increased risk of LBW or decreased mean birthweight due to longer ART duration during pregnancy.42

ART duration during pregnancy is intrinsically linked to length of gestation and thus preterm birth. To confine the preterm risk period to an interval in which women were either always or never on ART, and to maximize the number of ART initiation intervals (before pregnancy, during the 1st trimester, during the 2nd trimester) before the start of the risk period that we could examine, we restricted our analysis to births that occurred on or after 27 weeks and to women who either started ART before 27 weeks or did not receive ART at all before delivery. We are therefore unable to draw any conclusions about the effects of early ART on extremely early preterm birth (prior to 27 weeks) or the effects of ART initiated at or after 27 weeks on subsequent preterm births.

We note that there may have been some misclassification of preterm status and ART initiation time within pregnancy due to inaccurate estimates of the last menstrual period. The general consistency of our findings across analyses suggests that such misclassification may not be a large concern, and our specific finding that women initiating ART at any point during pregnancy were less likely to experience extremely to very preterm birth (vs. term birth) may be especially robust, given the five-week difference between the upper gestational age limit of very preterm (32 weeks) and the lower limit of full term (37 weeks).

Information on several covariates was either unavailable or insufficient. In particular, we did not have information on the interrelated covariates of ART adherence, CD4 count, and viral load. Poor ART adherence can result in drug resistance,43,44 lower CD4, and higher viral loads, leading to adverse maternal and birth outcomes. In general, ART adherence is high during pregnancy,45 and we expect that the fixed-dose TDF/3TC/EFV combination of one tablet per day in our study population would have encouraged high adherence.14 Furthermore, we would consider viral load and CD4 count to be casual intermediates between ART and preterm birth, and thus statistical adjustment would have been inappropriate even if viral load and CD4 data had been available. We also note that there may have been data entry errors, but we do not expect such errors to have been differential according to exposure or outcome status. It is, however, possible that some exclusions due to missing LMP or ART initiation time resulted in selection bias, but it is difficult to predict the magnitude and direction of any such biases. Furthermore, we note that some of our comparisons suffered from low precision due to small numbers of births, particularly in the analyses of preterm sub-categories.

ART initiation in pregnancy is an indicator of access to prenatal care and other health care services. In Malawi, HIV-infected women not on ART are initiated on life-long ART during an antenatal care visit,46 in addition to receiving treatment for anemia, malaria, and other infections as standard prenatal care. Women who attend antenatal care are less likely to deliver low birthweight infants, especially from preterm births.47,48 In the likely event that the women who had never initiated ART before delivery were less likely to have had access to prenatal care, then the higher preterm birth risk among those who did not initiate ART may not be fully attributable to lack of ART during pregnancy. No information on dates or numbers of antenatal visits, or of treatments received during such visits, was available in the POC-EMRS to allow control for antenatal care or specific components thereof.

Nevertheless, our results suggest that ART initiation before delivery does not increase preterm birth risk, and that it may in fact be protective against extremely to very preterm birth. Our results further suggest that ART initiation before conception may provide the optimal benefit. As the era of Option B+ continues, post-weaning ART retention should thus be a priority. These findings also suggest that HIV testing of women who wish to become pregnant, followed by ART initiation before conception in those testing HIV-positive, could be beneficial. If adequate uptake and retention can be achieved, then Option B+ may not only dramatically reduce vertical HIV transmission and improve maternal health, but also reduce preterm birth in settings with heavy, overlapping burdens of HIV and neonatal mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers KL2 TR001109, R01 HD080485, D43 TW001039-14) and a Gilead Training Fellowship.

References

- 1.March of Dimes P, Save the Children, WHO. Born Too Soon: The Global Action Report on Preterm Birth. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet. 2012 Jun 9;379(9832):2151–2161. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCormick MC. The contribution of low birth weight to infant mortality and childhood morbidity. The New England journal of medicine. 1985 Jan 10;312(2):82–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501103120204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008 Jan 5;371(9606):75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. 2012 Jun 9;379(9832):2162–2172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UNAIDS. How AIDS Changed Everything. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Vincenzi I. Triple antiretroviral compared with zidovudine and single-dose nevirapine prophylaxis during pregnancy and breastfeeding for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 (Kesho Bora study): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2011 Mar;11(3):171–180. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilewo C, Karlsson K, Ngarina M, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 through breastfeeding by treating mothers with triple antiretroviral therapy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: the Mitra Plus study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2009 Nov 1;52(3):406–416. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b323ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chasela CS, Hudgens MG, Jamieson DJ, et al. Maternal or infant antiretroviral drugs to reduce HIV-1 transmission. The New England journal of medicine. 2010 Jun 17;362(24):2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sterne JA, May M, Costagliola D, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in AIDS-free HIV-1-infected patients: a collaborative analysis of 18 HIV cohort studies. Lancet. 2009 Apr 18;373(9672):1352–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60612-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miro JM, Manzardo C, Mussini C, et al. Survival outcomes and effect of early vs. deferred cART among HIV-infected patients diagnosed at the time of an AIDS-defining event: a cohort analysis. PloS one. 2011;6(10):e26009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hargrove JW, Humphrey JH. Mortality among HIV-positive postpartum women with high CD4 cell counts in Zimbabwe. AIDS (London, England) 2010 Jan 28;24(3):F11–F14. doi: 10.1097/qad.0b013e328335749d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed S, Kim MH, Abrams EJ. Risks and benefits of lifelong antiretroviral treatment for pregnant and breastfeeding women: a review of the evidence for the Option B+ approach. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2013 Sep;8(5):474–489. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328363a8f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schouten EJ, Jahn A, Midiani D, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and the health-related Millennium Development Goals: time for a public health approach. Lancet. 2011 Jul 16;378(9787):282–284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO. Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating Pregnant Women and Preventing HIV Infection in Infants: Towards Universal Access: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CDC. Impact of an innovative approach to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV--Malawi, July 2011–September 2012. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2013 Mar 1;62(8):148–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection. Recommendation for a Public Health Approach. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Merwe K, Hoffman R, Black V, Chersich M, Coovadia A, Rees H. Birth outcomes in South African women receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy: a retrospective observational study. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2011;14:42. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez M, Figueras F, Hernandez S, et al. Association of HIV infection with spontaneous and iatrogenic preterm delivery: effect of HAART. AIDS (London, England) 2012 Jan 2;26(1):37–43. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834db300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen JY, Ribaudo HJ, Souda S, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and adverse birth outcomes among HIV-infected women in Botswana. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2012 Dec 1;206(11):1695–1705. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cotter AM, Garcia AG, Duthely ML, Luke B, O'Sullivan MJ. Is antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery, low birth weight, or stillbirth? The Journal of infectious diseases. 2006 May 1;193(9):1195–1201. doi: 10.1086/503045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kourtis AP, Schmid CH, Jamieson DJ, Lau J. Use of antiretroviral therapy in pregnant HIV-infected women and the risk of premature delivery: a meta-analysis. AIDS (London, England) 2007 Mar 12;21(5):607–615. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32802ef2f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuomala RE, Shapiro DE, Mofenson LM, et al. Antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy and the risk of an adverse outcome. The New England journal of medicine. 2002 Jun 13;346(24):1863–1870. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa991159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuomala RE, Watts DH, Li D, et al. Improved obstetric outcomes and few maternal toxicities are associated with antiretroviral therapy, including highly active antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2005 Apr 1;38(4):449–473. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000139398.38236.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Machado ES, Hofer CB, Costa TT, et al. Pregnancy outcome in women infected with HIV-1 receiving combination antiretroviral therapy before versus after conception. Sexually transmitted infections. 2009 Apr;85(2):82–87. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.032300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darak S, Darak T, Kulkarni S, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) during pregnancy on pregnancy outcomes: experiences from a PMTCT program in western India. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2013 Mar;27(3):163–170. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin F, Taylor GP. Increased rates of preterm delivery are associated with the initiation of highly active antiretrovial therapy during pregnancy: a single-center cohort study. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2007 Aug 15;196(4):558–561. doi: 10.1086/519848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marazzi MC, Palombi L, Nielsen-Saines K, et al. Extended antenatal use of triple antiretroviral therapy for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 correlates with favorable pregnancy outcomes. AIDS (London, England) 2011 Aug 24;25(13):1611–1618. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283493ed0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li N, Sando MM, Spiegelman D, et al. Antiretroviral Therapy in Relation to Birth Outcomes among HIV-infected Women: A Cohort Study. J. Infect. Dis. 2016 Apr 1;213(7):1057–1064. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.) 1999 Jan;10(1):37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernan MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Werler MM, Mitchell AA. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: an application to birth defects epidemiology. American journal of epidemiology. 2002 Jan 15;155(2):176–184. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. American journal of epidemiology. 1993 Dec 1;138(11):923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aebi-Popp K, Lapaire O, Glass TR, et al. Pregnancy and delivery outcomes of HIV infected women in Switzerland 2003–2008. Journal of perinatal medicine. 2010 Jul;38(4):353–358. doi: 10.1515/jpm.2010.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fowler M, Qin M, Fiscus S, Currier J, Makanani B, Martinson F. PROMISE: efficacy and safety of 2 strategies to prevent perinatal HIV transmission; Paper presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2015. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moodley T, Moodley D, Sebitloane M, Maharaj N, Sartorius B. Improved pregnancy outcomes with increasing antiretroviral coverage in South Africa. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2016;16:35. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0821-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiore S, Newell M-L, Trabattoni D, et al. Antiretroviral therapy-associated modulation of Th1 and Th2 immune responses in HIV-infected pregnant women. Journal of reproductive immunology. 2006;70(1):143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fiore S, Ferrazzi E, Newell ML, Trabattoni D, Clerici M. Protease inhibitor-associated increased risk of preterm delivery is an immunological complication of therapy. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2007 Mar 15;195(6):914–916. doi: 10.1086/511983. author reply 916–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Shazly S, Makhseed M, Azizieh F, Raghupathy R. Increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in placentas of women undergoing spontaneous preterm delivery or premature rupture of membranes. American journal of reproductive immunology (New York, N.Y.: 1989) 2004 Jul;52(1):45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prigoshin N, Tambutti M, Larriba J, Gogorza S, Testa R. Cytokine gene polymorphisms in recurrent pregnancy loss of unknown cause. American journal of reproductive immunology (New York, N.Y.: 1989) 2004 Jul;52(1):36–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clerici M, Shearer GM. A TH1-->TH2 switch is a critical step in the etiology of HIV infection. Immunology today. 1993 Mar;14(3):107–111. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clerici M, Shearer GM. The Th1–Th2 hypothesis of HIV infection: new insights. Immunology today. 1994;15(12):575–581. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bengtson AM, Chibwesha CJ, Westreich D, et al. Duration of cART Before Delivery and Low Infant Birthweight Among HIV-Infected Women in Lusaka, Zambia. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2016 Apr 15;71(5):563–569. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyons FE, Coughlan S, Byrne CM, Hopkins SM, Hall WW, Mulcahy FM. Emergence of antiretroviral resistance in HIV-positive women receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in pregnancy. AIDS (London, England) 2005 Jan 3;19(1):63–67. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200501030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paredes R, Cheng I, Kuritzkes DR, Tuomala RE. Postpartum antiretroviral drug resistance in HIV-1-infected women receiving pregnancy-limited antiretroviral therapy. AIDS (London, England) 2010 Jan 2;24(1):45–53. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e5303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nachega JB, Uthman OA, Anderson J, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy during and after pregnancy in low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS (London, England) 2012 Oct 23;26(16):2039–2052. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359590f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Republic of Malawi MoH. Malawi Guidelines for Clinical Management of HIV in Children and Adults. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reichman NE, Kenney GM. Prenatal care, birth outcomes and newborn hospitalization costs: patterns among Hispanics in New Jersey. Family planning perspectives. 1998 Jul-Aug;30(4):182–187. 200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vintzileos AM, Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Scorza WE, Knuppel RA. The impact of prenatal care in the United States on preterm births in the presence and absence of antenatal high-risk conditions. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2002 Nov;187(5):1254–1257. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.