Highlights

-

•

ECSWL failed to treat a residual gallbladder stone after failed cholecystectomy.

-

•

Even if a stone is fractured, it may not be expelled by a diseased gallbladder.

-

•

ECSWL should be followed by endoscopic retrieval to complete treatment.

Abbreviations: ECSWL, extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy; SCARE, surgical case report; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Keywords: Case report, Gallbladder, Gallstones, Cholecystectomy, Lithotripsy

Abstract

Introduction

Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ECSWL) for gallstones is rarely used due to high recurrence rates, but has been reported to be effective in some circumstances.

Presentation of case

We describe a case of a failed attempt at laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to gallbladder contraction and complete obliteration of Calot’s triangle. Cholecystotomy was performed to remove all visible stones, and completed by a subtotal cholecystectomy and closure of the gallbladder remnant. The patient remained symptomatic due to a residual stone in the Hartmann’s pouch. ECSWL was attempted to fragment the stone; however, follow-up imaging showed persistence of the calculus.

Discussion

Literature review shows that ECSWL for multiple gallbladder stones has a low success rate. Even if a stone is successfully fragmented, a diseased gallbladder remnant seems incapable of expelling the fragments. Without completion endoscopic clearance, therefore, the treatment is considered incomplete.

Conclusion

Our case suggests that ECSWL is ineffective in management of residual gallbladder stones after failed cholecystectomy.

1. Introduction

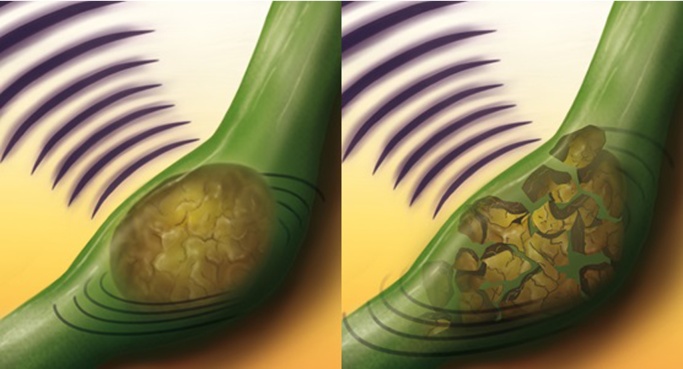

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice for symptomatic gallbladder disease; it is usually followed by excellent symptomatic relief and associated with a low recurrence rate [1]. extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ECSWL) has been used in adjunct with deoxycholic acid therapy to disintegrate large (>15 mm) ductal stones prior to completion endoscopic clearance (Fig. 1) [2], [3], [4]. Our attempt at ECSWL, for a stone in the residual gallbladder after an incomplete laparoscopic cholecystectomy proved to be unsuccessful. Here, we present our case as per SCARE guidelines [5].

Fig. 1.

Artist’s illustration of ECSWL for gallstones. Successful end result is shown on the right with fracturing of the stones; but these fragments require endoscopic clearance to complete therapy.

2. Presentation of case

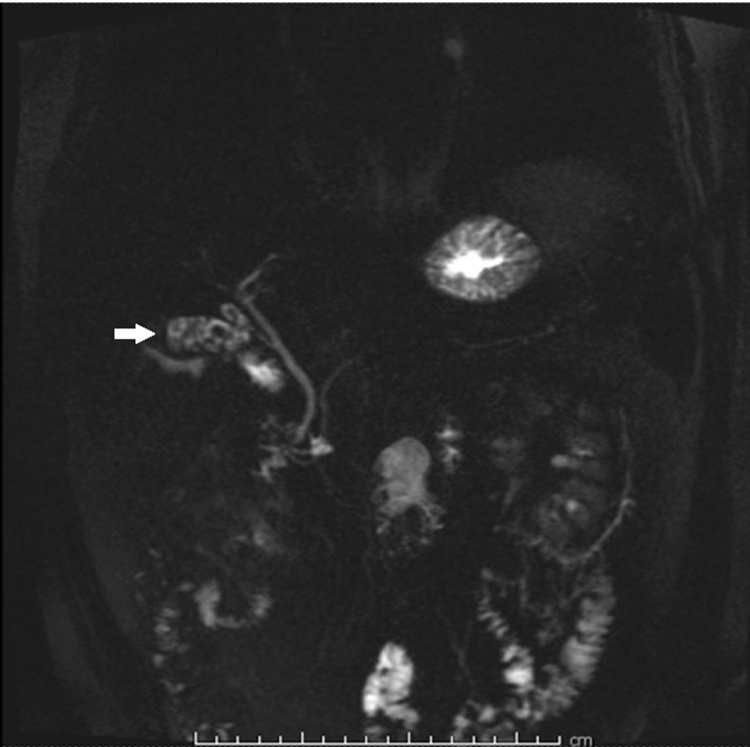

A 61-year-old man was referred to our general surgery clinic with a one-year history of typical biliary dyspepsia, with intermittent upper abdominal pain, on a background of at least one episode of jaundice and deranged liver function tests. An abdominal ultrasound scan had shown a normal liver, with a contracted gallbladder containing an acoustic shadow. Magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography (MRCP) confirmed the presence of multiple calculi inside a contracted gallbladder, whereas the ductal system appeared normal (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Coronal MRI taken before surgery. Multiple gallstones are visible in the gallbladder.

A laparoscopic cholecystectomy was attempted; signs of severe chronic inflammation with shrinkage of the gallbladder, and complete obliteration of Calot’s triangle were noted, making a safe cholecystectomy impossible. Conversion to an open approach was considered; however, the laparoscopic image and access were clear, and the severe inflammation of Calot’s triangle would have remained a problem even in an open procedure. In order to avoid the high risk of injury to the common bile duct, dissection of Calot’s triangle was not attempted. Instead, cholecystotomy was performed and 17 gallstones were extracted, including three which had been impacted in the cystic duct. The gallbladder remnant, which included Hartmann’s pouch, was then closed.

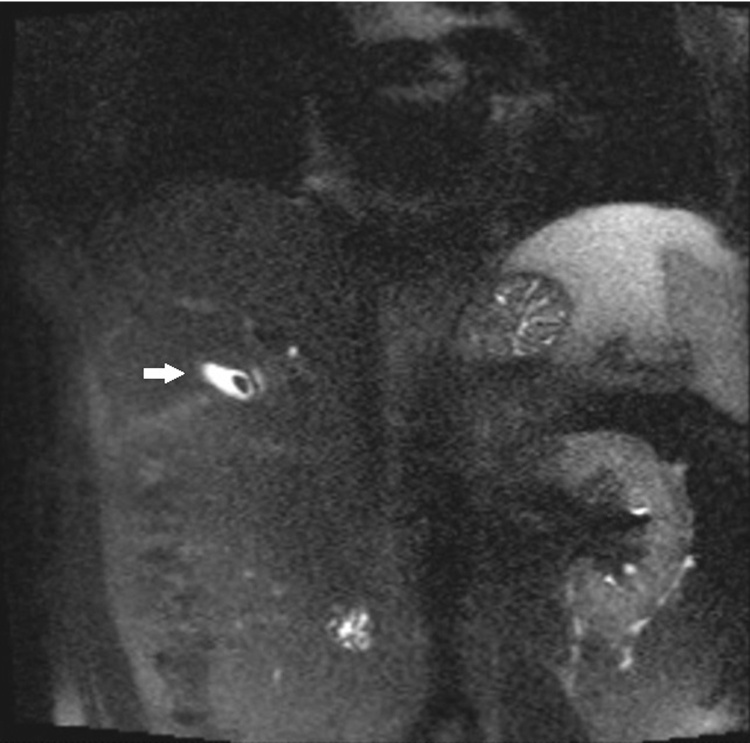

Eight months later the patient reported recurrence of his biliary dyspepsia symptoms. Magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography revealed a single residual stone within the gallbladder remnant, but none in the common bile duct (Fig. 4). The patient was commenced on deoxycholic acid and referred to our urology department for consideration of extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy.

Fig. 4.

Coronal MRI taken after surgery. A gallstone is visible in the gallbladder remnant.

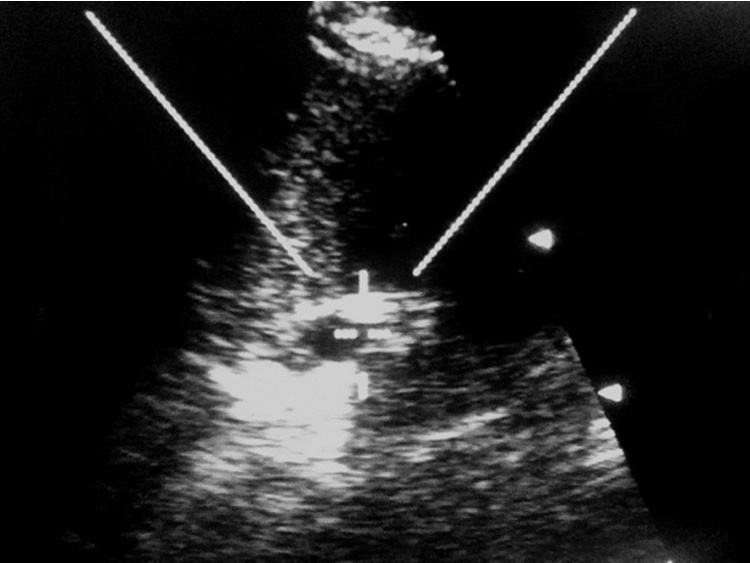

A single round of lithotripsy was performed nine months later by a senior radiographer. The stone was located by ultrasound (Fig. 2). Using water as a conduction medium, 4500 low-energy (up to E2.0) shots were applied at up to 2 shocks per second. From 1000 shots onwards, increasing fragmentation and movement of fragments observed. Towards the end of the procedure, fragmentation was detected along the whole length of the stone, and the patient tolerated the procedure well. On this basis, the lithotripsy treatment was judged to be successful and no further sessions were booked. However, a follow-up MRCP five months later showed similar appearances to the previous scan, with a 9 mm calculus persisting within the gallbladder remnant (Fig. 5).

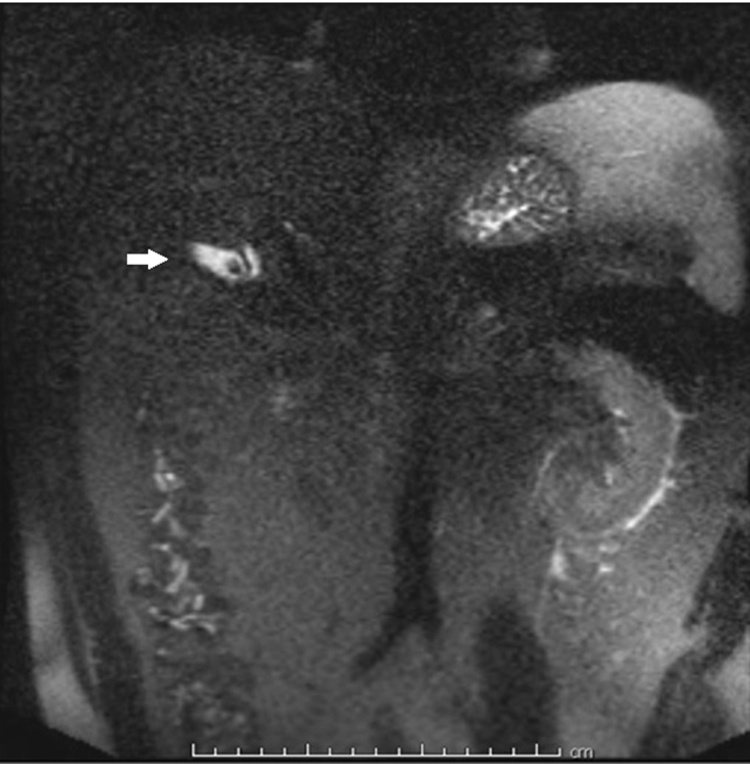

Fig. 2.

Ultrasound image of the gallbladder remnant during ECSWL. The gallstone is visible in the centre of the image.

Fig. 5.

Coronal MRI taken after ECSWL. The gallstone remains visible in the gallbladder remnant.

Timeline

- 0 months

Initial presentation to GP with abdominal pain

- 9 months

Seen in general surgery clinic; MRI confirmed gallbladder stones

- 15 months

Laparoscopic cholecystotomy and gallstone extraction performed

- 20 months

MRI showed residual stone in gallbladder remnant

- 23 months

Remained symptomatic; commenced on deoxycholic acid

- 32 months

ECSWL performed

- 37 months

MRI showed persistent stone in gallbladder remnant

3. Discussion

Review of the literature suggests a number of factors that may affect the success or failure of ECSWL for gallstones, including location and number of stones. ECSWL has been shown to be an effective adjunct for the clearance of common bile duct (CBD) stones resistant to endoscopic retrieval [3], [4]. ECSWL can be effective for small solitary stones gallbladder stones but the success rate is low for multiple gallbladder stones, or for stones with high density [6]. It is also believed that normal gallbladder contractility is needed for stone fragments to be cleared from the gallbladder into the ductal system [7], [8], [9], which 80% of the time will require endoscopic extraction for successful clearance [10].

In our case, the residual calculus was located within the diseased gallbladder remnant. We applied ECSWL, hoping that the resultant gallstone fragments would be spontaneously extruded into the ductal system (and eventually into the duodenum) by the contraction of the gallbladder remnant, facilitated by the effect of the deoxycholic acid. However, the fragments were not extruded, likely because fibrosis (secondary to recurrent cholecystitis) had rendered the gallbladder remnant non-contractile. Even if the gallstone fragments had been extruded into the ductal system, a completion endoscopic retrieval from the common bile duct would have been required to deliver them into the duodenum.

We remain convinced that conversion to an open approach at index surgery would have been inappropriate; as this would have increased the risk of morbidity, in return for dubious benefit. We nevertheless recognise that there were some pitfalls in our management strategy that are worthy of discussion as learning points.

Gallstones detected within 2 years after attempted removal are considered ‘residual’ [11]. Our patient’s symptoms returned within 8 months, and an MRCP confirmed the presence of a stone. This stone was likely, therefore, missed during the initial operation.

The fibrosed gallbladder remnant, containing the residual stone, was closely applied to the bile duct; this constituted a Type I Mirrizzi syndrome, presenting us with a management dilemma [12]. The index surgery was difficult; re-operation would have been much more challenging, with an unacceptably high risk of ductal injury, and requiring complex biliary reconstruction. The option of endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy and retrieval was discussed; but deemed too unsafe, due to the size of the residual gallstone, difficult access to the gallbladder remnant via the cystic duct, and the risk of basket entrapment which would have forced us into difficult emergency surgery. At the time, ECSWL seemed to be a reasonable option; however, in retrospect, it is clear that it was inappropriate in this case, as a contractile gallbladder should be a prerequisite when considering ECSWL for gallbladder stones. In the context of a non-contractile gallbladder, the adjunct use of deoxycholic acids was a waste of expensive resources.

If gallstone fragments had been extruded into the common bile duct, endoscopic removal would have been mandatory to complete the treatment. In this case, perhaps endoscopic retrieval of the fractured stone from the gallbladder remnant should have been attempted; although success would not have been guaranteed due to difficulty in manipulating the endoscopic baskets into the gallbladder remnant. Nevertheless, not doing so is considered an incomplete therapy and a possible missed opportunity.

4. Conclusion

This is the first reported case of attempted ECSWL, with or without adjunct deoxycholic acid, for a persistently impacted gallstone in a post-cholecystotomy gallbladder remnant. Our case confirms that, while this technique might be successful at fracturing the stone, the treatment is incomplete and a waste of resources if endoscopic retrieval does not follow. This must be borne in mind in all cases considered for ECSWL for residual biliary stones.

Conflicts of interest

None to declare.

Funding for your research

No funding.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Consent

The patient has given verbal and written consent for the publication of this case report and associated images.

Author contribution

Sadik Quoraishi: Lead author: planning, data collection, literature review, writing.

Jake Ahmed: Literature review and patient liaison.

Andrew Ponsford: Performed ECSWL and described technique.

Ashraf Rasheed: Editing, providing illustration, and supervision.

The manuscript has been read and approved by all authors.

Guarantor

Sadik Quoraishi.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ransohoff D.F., Gracie W.A. Treatment of gallstones. Ann. Intern. Med. 1993;119(7_Part_1):606–619. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_1-199310010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis R.D., Jenkins A.P., Thompson R.P.H., Ede R.J. Clearance of refractory bile duct stones with extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy. Gut. 2000;47:728–731. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.5.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muratori R., Azzaroli F., Buonfiglioli F., Alessandrelli F., Cecinato P., Mazzella G., Roda E. ESWL for difficult bile duct stones: a 15-year single centre experience. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010;16(33):4159–4163. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i33.4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sackmann M., Holl J., Sauter G.H., Pauletzki J., von Ritter C., Paumgartner G. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for clearance of bile duct stones resistant to endoscopic extraction. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001;53(1):27–32. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.111042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34(October):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabenstein T., Radespiel-Tröger M., Höpfner L., Benninger J., Farnbacher M., Greess H., Lenz M., Hahn E.G., Schneider H.T. Ten years experience with piezoelectric extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy of gallbladder stones. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005;17(6):629–639. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200506000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ochi H., Tazuma S., Kajihara T., Hyogo H., Sunami Y., Yasumiba S., Nakai K., Tsuboi K., Asamoto Y., Sakomoto M., Kajiyama G. Factors affecting gallstone recurrence after successful extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2000;31(3):230–232. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200010000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pauletzki J., Sailer C., Klüppelberg U., Von Ritter C., Neubrand M., Holl J., Sauerbruch T., Sackmann M., Paumgartner G. Gallbladder emptying determines early gallstone clearance after shock-wave lithotripsy. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(5):1496–1502. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donald J.J., Fache J.S., Burhenne H.J. Biliary lithotripsy: correlation between gallbladder contractility before treatment and the success of treatment. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1991;157(2):287–290. doi: 10.2214/ajr.157.2.1853808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritter C., Paumgartner G. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for clearance of bile duct stones resistant to endoscopic extraction. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001;53(1):27–32. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.111042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kibria S., Hall R. Recurrent bile duct stones after transduodenal sphincteroplasty. HPB. 2002;4(2):63–66. doi: 10.1080/136518202760378416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uppara M., Rasheed A. Systematic review of Mirizzi’s syndrome’s management. JOP: J. Pancreas. 2016;18(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]