Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the proportion of guideline nonadherent Pap tests in women aged younger than 21 years and older than 65 years and posthysterectomy in a single large health system. Secondary objectives were to describe temporal trends and patient and health care provider characteristics associated with screening in these groups.

Methods

A retrospective cross-sectional chart review was performed at Fairview Health Services and University of Minnesota Physicians. Reasons for testing and patient and health care provider information were collected. Tests were designated as indicated or non-indicated per the 2012 cervical cancer screening guidelines. Point estimates and descriptive statistics were calculated. Patient and health care provider characteristics were compared between indicated and non-indicated groups using chi-squared and Wilcoxon Rank-sum tests.

Results

A total of 3,920 Pap tests were performed between 9/1/12–8/31/14. A total of 257 (51%; 95% CI 46.1–54.9%) of tests in the <21 years group, 536 (40%; 95% CI 37.7–43.1%) in the >65 group and 605 (29%; 95% CI 27.1–31.0%) in the posthysterectomy group were not indicated. White race in the >65 group was the only patient characteristic associated with receipt of a non-indicated Pap test (p=0.007). Provider characteristics associated with non-indicated Pap tests varied by screening group. Temporal trends showed a decrease in the proportion of non-indicated tests in the <21 years group, but an increase in the posthysterectomy group.

Conclusion

For women aged younger than 21 years and older than 65 years, and posthysterectomy, 35% of Pap tests performed in our health system were not guideline-adherent. There were no patient or health care provider characteristics associated with guideline nonadherent screening across all groups.

Introduction

In 2012 the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP), American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP), American Cancer Society (ACS) and the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published unified cervical cancer screening guidelines which sought to minimize the harms of over-screening while maintaining adequate detection of treatable cervical cancer precursors (1, 2). The guidelines recommended against screening in average-risk women younger than 21 years, older than 65 years of age provided adequate previous screening and no history of high-grade dysplasia in the past 20 years, and posthysterectomy with the cervix removed and no history of high-grade dysplasia in the past 20 years. For women for whom screening is still recommended, the guidelines lengthened the screening interval for all age groups (Table 1). These guidelines were developed based on an extensive systematic evidence review, and were endorsed by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) (3), with subsequent updates published by ACOG in 2016 (4).

Table 1.

2012 National Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines

| Screening Population | American Cancer Society, American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American Society of Clinical Pathologists, United States Preventive Services Task Force Recommendationsa |

|---|---|

| Age <21 years | No screening |

| Age 21–29 years | Pap test alone (no HPVb test) every 3 years |

| Age 30–65 years | Pap + HPV co-test every 5 years (recommended by American Cancer Society, American Society of Colposcopy and Clinical Pathology, American Society of Clinical Pathology) OR Pap test alone every 3 years (considered acceptable by American Cancer Society, American Society of Colposcopy and Clinical Pathology, American Society of Clinical Pathology) |

| Age >65years | No screening if:

|

| Post-hysterectomy | No screening if:

|

Recommendations apply only to average-risk women. Women who are immunocompromised or who were exposed to diethylstilbestrol require additional screening.

HPV, human papillomavirus

High-grade dysplasia also includes cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 or 3, carcinoma in situ (CIS) and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS).

Although cervical cancer screening guidelines have recommended against screening in women posthysterectomy and age >65 years since 2003 and against screening in women <21 years since 2009, survey studies have shown that a majority of women younger than age 21 years, older than age 65 years and posthysterectomy continue to undergo cytology screening (5, 6). While these self-reported high rates of continued screening are concerning, health care provider and patient surveys are only a proxy for true practice patterns. This study was performed to obtain a more objective measure of the rates of non-indicated cervical cancer screening at the extremes of age and posthysterectomy. The primary objective of this study was to determine the guideline non-indicated screening Pap test rates in women younger than age 21 years (<21), older than age 65 years (>65) or posthysterectomy in a single large health system. The secondary objectives of this study were to describe patient and health care provider characteristics associated with performance of a non-indicated Pap test in populations for whom the guidelines recommend against screening and to describe temporal trends during the study period.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. The electronic health record was queried using Common Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for all Pap tests performed between September 1, 2012 (6 months after publication of the American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American Society for Clinical Pathology and American Cancer Society guidelines) and August 31, 2014 within University of Minnesota Physicians and Fairview Health Services, a large nonprofit health center in Minnesota which partners with 2,500 physicians and has over 40 primary care clinics (7). The health system includes academic and community clinics in urban, suburban and rural locations. The dataset included the following information: 1) patient demographics: patient age at the time of Pap test, patient race; 2) Encounter information: clinic location and specialty; 3) Provider information: health care provider name and degree (Medical Doctor or Doctor of Osteopathy, Nurse Practitioner, Physician Assistant, Certified Nurse Midwife, other). The dataset was then further queried to identify the three following groups of patients: 1) younger than 21 years of age (<21); 2) older than 65 years of age (>65); 3) posthysterectomy. For patients undergoing more than one Pap test during the study period, only the first Pap test was included in the data analysis. A random number generator (www.randomizer.org/form.htm) was used to randomly select 30% of charts within each of the three screening groups for a manual chart review. For each group, if >10% of reviewed Pap tests were categorized as indicated based on patient risk factors and/or previous Pap test results, then all charts in that group were manually reviewed.

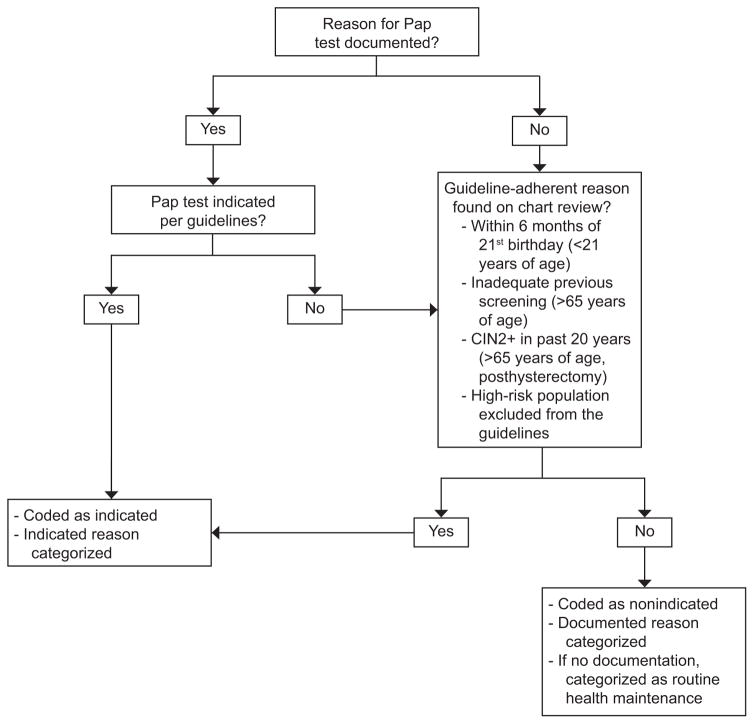

For the manual chart reviews, encounter notes, previous Pap and Human Papillomavirus test results and patient medical and surgical histories were reviewed to determine the indication for the Pap test. For the <21 group, indicated reasons for Pap testing included: 1) immunosuppression, including transplant clearance; 2) follow-up of a previous abnormal Pap test; 3) age 21 years within 6 months of Pap test. Although screening women age 20.5 years is not specifically indicated by the guidelines, we assumed that health care providers were providing necessary preventive healthcare due to worry that these women may not return to clinic for several years, and thus these Pap tests were analyzed as indicated. For the >65 group, indicated reasons for screening included: 1) history of high-grade dysplasia within the past 20 years; 2) inadequate previous screening (adequate previous screening defined per the guidelines as at least three documented normal Pap tests or two normal co-tests within the past 10 years with at least one test within 5 years of age 65 years); 3) immunosuppression; 4) in-utero diethylstilbestrol exposure; 5) cancer surveillance (cervical, vulvar, vaginal, anal, endometrial, ovarian cancer surveillance). For the posthysterectomy group, indicated screening included: 1) supracervical hysterectomy (a supracervical hysterectomy was assumed unless removal of the cervix was documented in the surgical history, clinic or operative notes or vaginal cytology was specified on the Pap order); 2) history of high-grade dysplasia within the past 20 years; 3) immunosuppression; 4) diethylstilbestrol exposure; 5) cancer surveillance. Although vaginal cytology is no longer recommended for endometrial cancer surveillance, it was not removed from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network surveillance guidelines until 2015 and thus was categorized as indicated for the study period. During the study period national cancer surveillance guidelines did not recommend vaginal cytology for ovarian cancer surveillance, however, since this was recommended by most of the local gynecologic oncologists during the study period, Pap tests performed for this reason were coded as indicated. For encounter notes detailing the reason for cervical cancer screening, the stated reason was used as the indication, unless a more guideline-adherent reason also existed. For example, if the clinic note documented that screening was performed in a woman >65 per patient request, but review of her labs and previous clinic notes did not document three normal Pap tests within 10 years, inadequate previous screening was listed as the indication for screening. For women <21 years of age who were presenting for prenatal care or their postpartum visit with no other indicated reason for Pap testing, “pregnancy” was listed as the reason for screening unless the patient was within 6 months of her 21st birthday. For charts in which the reason for Pap testing was not stated and an indicated reason was not discovered during chart review, “routine health maintenance” was assigned by the investigators as the indication for screening (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart describing the designation of Pap tests as indicated or non-indicated. Documented reasons were used unless a non-documented but indicated reason for a Pap test was discovered on chart review. Pap tests without a documented reason and for which no guideline-adherent indication was found were categorized as “routine health maintenance.”

Health care provider information, including gender and birthdate to calculate age in 2012, was obtained from the Minnesota Board of Medical Practice for physicians and physician assistants, and from the Minnesota Board of Nursing for nurse practitioners and certified nurse midwives. The zip codes for the clinics were documented, and clinic locations were dichotomized as less than or greater than 60 miles from Minneapolis to serve as a surrogate for urban/suburban (<60 miles) or rural (>60 miles) clinics.

The primary objective of the study was to determine the proportion of non-indicated screening Pap tests performed in women <21 and >65 years of age and posthysterectomy. The secondary objectives were to describe patient and health care provider characteristics associated with screening in populations for whom the guidelines recommend against screening and to describe temporal trends during the study period. Point estimates and exact 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the proportion of non-indicated Pap tests were calculated for each screening group. Differences in the proportion of non-indicated Pap tests were compared within each screening scenario by patient race and year of test using chi-squared tests and age using Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests. Descriptive statistics for health care provider level data were calculated, and adherence to guidelines by health care provider level characteristics, including age, gender, degree, specialty, clinic location, and frequency of Pap orders (dichotomized as <1 Pap per week or 1+ Pap per week), was compared using general estimating equation models to account for repeated measures for some health care providers assuming an exchangeable correlation structure. Multivariate models were considered for each screening group including both patient and health care provider level characteristics identified as potentially relevant based on the univariate analyses, including variables with p-values <0.10. Data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC) and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Between September 1, 2012 and August 31, 2014, a total of 122,254 Pap tests were performed in 77,899 individual patients within the health system. Pap tests were performed in a total of 3,920 women <21 and >65 and posthysterectomy (5% of the total population). During this time period, co-testing was not uniformly performed, but reflex Human Papillomavirus testing was performed as indicated per the American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology Management guidelines (8); primary Human Papillomavirus testing was not performed during the study period. In the review of a random sample of 30% of the charts in each age group, 31% (n=62) in the <21, 51% (n=207) in the >65 and 48% (n=506) in the posthysterectomy group were guideline-indicated Pap tests. Therefore, all charts within each group were manually reviewed.

A total of 509 women under age 21 years (1% of all patients) underwent at least one Pap test during the study period. Of those, 257 (50.5%; 95% CI 46.1–54.9%) of these Pap tests were not indicated per the 2012 guidelines; if patients within 6 months of their 21st birthdays had been coded as not indicated, then 94% of Pap tests in this age group would have been non-indicated. The reasons for the non-indicated tests included routine health maintenance (66%), pregnancy (27%), and patient request (7%). A majority of indicated Pap tests were performed in women who were within 6 months of their 21st birthday (89%), with a smaller number performed to follow-up abnormal Pap tests performed prior to 2012 (8%), due to immunocompromised status or transplant clearance (3%), or as a requirement to enroll in the military (0.4%). There was a difference in median age between those for whom screening was indicated compared to those for whom screening was not indicated (p<0.0001), likely due to inclusion of all women within 6 months of their 21st birthday as indicated.(Table 2). Patients in this age group were seen by 219 health care providers; the median number of patients seen by each health care provider was 1 (range: 1–19). Providers performing non-indicated Pap tests were more likely to be older (p=0.01), male (p=0.0005), and to perform Pap tests less than once per week (p=0.002). Compared to physicians, nurse practitioners (p=0.05) and physician assistants (p=0.003) were less likely to perform non-indicated Pap tests. However, in multivariate analysis, only performing Pap tests less than once per week remained significant (p=0.003) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Age <21 Group

| Patient characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N=509) | Pap Not Indicated (N=257) | Pap Indicated (N=252) | p-valuea | |

| Patient Age, years median (range) | 20 (14–20) | 19 (14–20) | 20 (18–20) | <0.0001 |

| Race n (%) | 0.58 | |||

| African/African Am | 54 (10.6) | 31 (57.4) | 23 (42.6) | |

| Am Indian/Alaskan | 7 (1.4) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | |

| Asian | 16 (3.2) | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | |

| White | 406 (79.8) | 205 (50.5) | 201 (49.5) | |

| No response | 26 (5.1) | 13 (50.0) | 13 (50.0) | |

| Provider characteristics | ||||

| Pap Not Indicated (N=257) | Pap Indicated (N=252) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-valueb | |

| Provider Age, years mean ±SD | 47.6±11.3 | 44.8±10.9 | 1.03 (1.01–1.05)c | 0.01 |

| Gender | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Female | 181 (45.6) | 217 (54.5) | 1.00 | |

| Male | 76 (68.5) | 35 (31.5) | 2.44 (1.48–4.03) | 0.0005 |

| Provider Degree | ||||

| MD/DO | 190 (57.6) | 140 (42.4) | 1.00 | |

| NP | 35 (41.7) | 49 (58.3) | 0.53 (0.29–0.99) | 0.05 |

| CNM | 5 (27.8) | 13 (72.2) | 0.40 (0.14–1.14) | 0.09 |

| PAC | 27 (35.1) | 50 (64.9) | 0.43 (0.24–0.75) | 0.003 |

| Specialty | ||||

| Family Medicine | 192 (52.2) | 176 (47.8) | 1.00 | |

| Internal Medicine | 19 (43.2) | 25 (56.8) | 0.67 (0.35–1.26) | 0.21 |

| Obstetrics/Gynecololgy | 43 (48.3) | 46 (51.7) | 0.72 (0.37–1.39) | 0.32 |

| Other | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 0.50 (0.10–2.44) | 0.39 |

| Clinic within 60 miles of Minneapolis | ||||

| Yes | 236 (49.6) | 240 (50.4) | 1.00 | |

| No | 21 (63.6) | 12 (36.4) | 1.71 (0.69–4.24) | 0.25 |

| Frequency of Pap Orders | ||||

| 1+ Pap per week | 194 (47.1) | 218 (52.9) | 1.00 | |

| <1 Pap per week | 63 (65.0) | 34 (35.1) | 2.20 (1.34–3.61) | 0.002 |

| Multivariate Modelb,d | ||||

| Provider age | 1.02 (1.00–1.04)c | 0.06 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1.00 | |||

| Male | 1.28 (0.72–2.28) | 0.40 | ||

| Provider Degree | ||||

| MD/DO | 1.00 | |||

| NP | 0.54 (0.28–1.03) | 0.06 | ||

| CNM | 0.37 (0.13–1.07) | 0.06 | ||

| PAC | 0.53 (0.28–1.00) | 0.05 | ||

| Frequency of Pap Orders | ||||

| 1+ Pap per week | 1.00 | |||

| <1 Pap per week | 2.27 (1.33–3.86) | 0.003 | ||

Am, American. MD, Medical Doctor. DO, Doctor of Osteopathy. NP, Nurse Practitioner. CNM, Certified Nurse Midwife. PAC, Physician Assistant.

Categorical variables: Fisher’s Exact test; continuous variables: Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

General estimating equation model

Per 1 year increase in age

Adjusted for health care provider age, health care provider gender, health care provider degree and frequency of pap orders; effective sample size: N=197

A total of 1,327 women older than age 65 years (2% of all patients) underwent at least one Pap test during the study period. Of these, 536 (40.4%; 95% CI 37.7–43.1%) were not indicated. The most common reason for non-indicated Pap tests was routine health maintenance (88%). Other reasons for non-indicated Pap tests were patient request (7%), follow-up of previous abnormal Pap tests for which the guidelines do not recommend follow-up (e.g. follow-up of an ASCUS Pap test 10 years prior with subsequent normal Pap tests; 5%), and history of high-grade cervical dysplasia more than 20 years prior with subsequent normal screening (0.6%). The most common reasons for indicated cervical cancer screening in this age group were inadequate previous screening (56%), followed by guideline-adherent follow-up of an abnormal cervical cancer screening test (18%). Other reasons for indicated Pap testing were cancer surveillance (11%), evaluation of post-menopausal bleeding or abnormal exam findings (10%), high-grade dysplasia within the past 20 years (3%), immunocompromised state or transplant clearance (1%), diethylstilbestrol exposure (0.1%), and to meet a requirement for a research study (0.1%). In this group, white women were more likely to receive non-indicated screening (p=0.007) (Table 3). Patients in this age group were seen by 317 health care providers; the median number of patients seen by each health care provider was 2 (range: 1–52). Providers performing non-indicated Pap tests in this group were more likely to be older (p=0.008), male (p=0.02), in specialties other than gynecology (p=0.04) and to work within 60 miles of Minneapolis (p=0.002). In multivariate analysis, male gender (p=0.01), specialty (p=0.02) and clinic location (p=0.001) remained significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Age >65 Group

| Patient characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N=1327) | Pap Not Indicated (N=536) | Pap Indicated (N=791) | p-valuea | |

| Patient Age, years median (range) | 69 (65–95) | 68 (66–88) | 69 (65–95) | 0.25 |

| Race n (%) | 0.007 | |||

| African/African Am | 33 (2.5) | 6 (18.2) | 27 (81.8) | |

| Am Indian/Alaskan | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (100.0) | |

| Asian | 26 (2.0) | 7 (26.9) | 19 (73.1) | |

| White | 1239 (93.4) | 516 (41.7) | 723 (58.4) | |

| No response | 24 (1.8) | 7 (29.2) | 17 (70.8) | |

| Provider characteristics | ||||

| Pap Not Indicated (N=536) | Pap Indicated (N=791) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-valueb | |

| Provider Age, years mean ±SD | 51.5±11.9 | 48.8±11.3 | 1.02 (1.00–1.03)c | 0.008 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 351 (37.5) | 585 (62.5) | 1.00 | |

| Male | 185 (47.3) | 206 (52.7) | 1.53 (1.07–2.18) | 0.02 |

| Provider Degree | ||||

| MD/DO | 476 (41.6) | 669 (58.4) | 1.00 | |

| NP | 40 (34.5) | 76 (65.5) | 0.76 (0.48–1.20) | 0.24 |

| CNM | 1 (9.1) | 10 (90.9) | 0.22 (0.03–1.75) | 0.15 |

| PAC | 19 (34.6) | 36 (65.5) | 0.90 (0.45–1.79) | 0.76 |

| Specialty | ||||

| Family Medicine | 334 (41.8) | 466 (58.3) | 1.00 | |

| Internal Medicine | 70 (42.2) | 96 (57.8) | 1.06 (0.67–1.68) | 0.79 |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 128 (37.1) | 217 (62.9) | 0.66 (0.44–0.99) | 0.04 |

| Clinic within 60 miles of Minneapolis | ||||

| Yes | 532 (42.8) | 711 (57.2) | 1.00 | |

| No | 4 (4.8) | 80 (95.2) | 0.13 (0.04–0.46) | 0.002 |

| Frequency of Pap Orders | ||||

| 1+ Pap per week | 428 (41.2) | 611 (58.8) | 1.00 | |

| <1 Pap per week | 108 (37.5) | 180 (62.5) | 0.91 (0.65–1.29) | 0.61 |

| Multivariate Modelb,d | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1.00 | |||

| Male | 1.73 (1.14–2.61) | 0.01 | ||

| Specialty | ||||

| Family Medicine | 1.00 | |||

| Internal Medicine | 1.13 (0.68–1.85) | 0.64 | ||

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 0.62 (0.42–0.92) | 0.02 | ||

| Clinic Location | ||||

| <60 miles from Minneapolis | 1.00 | |||

| >60 miles from Minneapolis | 0.12 (0.03–0.44) | 0.001 | ||

Am, American. MD, Medical Doctor. DO, Doctor of Osteopathy. NP, Nurse Practitioner. CNM, Certified Nurse Midwife. PAC, Physician Assistant.

Categorical variables: Fisher’s Exact test; continuous variables: Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

General estimating equation model

Per 1 year increase in age

Adjusted for health care provider gender, health care provider specialty and clinic location; effective sample size: N=290

A total of 2,084 women had at least one Pap test posthysterectomy (3% of all patients). Of these, 605 (29.0%; 95% CI 27.1–31.0%) were not indicated per the guidelines. The most common reason for non-indicated Pap tests was routine health maintenance (87%), with a much smaller proportion performed for non-indicated follow-up of abnormal Pap tests in the distant past (6%), patient request (4%), history of high-grade dysplasia more than 20 years prior (3%), and cancer surveillance in cancers without a Pap test indication, such as non-genital melanoma (0.7%). The most common reasons for indicated Pap tests were cancer surveillance (45%) and supracervical hysterectomy (37%). Other indications were history of high-grade dysplasia within the past 20 years (11%), guideline-adherent follow-up of an abnormal Pap test (3%), evaluation of vaginal bleeding or an abnormal exam finding (3%), and diethylstilbestrol exposure, immunocompromised state or transplant clearance, patient request (each <1%). There were no differences patient characteristics between those who had indicated versus non-indicated testing (Table 4). Patients in this group were seen by 362 health care providers; the median number of patients seen by each health care provider was 3 (range: 1–122). Gynecologists were less likely than primary care health care providers to order non-indicated Pap tests (p=0.003); no other health care provider characteristics were associated with the ordering of non-indicated tests (Table 4).

Table 4.

Post-hysterectomy Group

| Patient characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N=2084) | Pap Not Indicated (N=605) | Pap Indicated (N=1479) | p-valuea | |

| Patient Age, years median (range) | 54 (24–89) | 55 (28–88) | 54 (24–89) | 0.12 |

| Race n (%) | 0.64 | |||

| African/African Am | 95 (4.6) | 31 (32.6) | 64 (67.4) | |

| Am Indian/Alaskan | 24 (1.2) | 4 (16.7) | 20 (83.3) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 40 (1.9) | 13 (32.5) | 27 (67.5) | |

| White | 1854 (89.0) | 539 (29.1) | 1315 (70.9) | |

| No response | 71 (3.4) | 18 (25.4) | 53 (74.7) | |

| Provider characteristics | ||||

| Pap Not Indicated (N=605) | Pap Indicated (N=1479) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-valueb | |

| Provider Age, years mean ±SD | 47.2±11.7 | 45.8±10.5 | 1.00 (0.99–1.02)c | 0.50 |

| Gender | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Female | 449 (26.9) | 1219 (73.1) | 1.00 | |

| Male | 156 (37.5) | 260 (62.5) | 1.25 (0.89–1.74) | 0.20 |

| Provider Degree | ||||

| MD/DO | 433 (31.2) | 953 (68.8) | 1.00 | |

| NP | 91 (18.9) | 391 (81.1) | 1.16 (0.77–1.74) | 0.49 |

| CNM | 3 (18.8) | 13 (81.3) | 0.75 (0.18–3.10) | 0.70 |

| PAC | 78 (39.0) | 122 (61.0) | 1.35 (0.90–2.03) | 0.15 |

| Specialty | ||||

| Family Medicine | 397 (38.4) | 638 (61.6) | 1.00 | |

| Internal Medicine | 63 (37.1) | 107 (62.9) | 0.91 (0.60–1.39) | 0.67 |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 130 (28.6) | 324 (71.4) | 0.61 (0.44–0.85) | 0.003 |

| Other | 15 (3.5) | 410 (96.5) | 0.07 (0.04–0.15) | <0.001 |

| Clinic within 60 miles of Minneapolis | ||||

| Yes | 582 (28.9) | 1435 (71.2) | 1.00 | |

| No | 23 (34.3) | 44 (65.7) | 1.24 (0.64–2.40) | 0.53 |

| Frequency of Pap Orders | ||||

| 1+ Pap per week | 513 (29.2) | 1243 (70.8) | 1.00 | |

| <1 Pap per week | 92 (28.1) | 236 (72.0) | 1.05 (0.76–1.44) | 0.78 |

Am, American. MD, Medical Doctor. DO, Doctor of Osteopathy. NP, Nurse Practitioner. CNM, Certified Nurse Midwife. PAC, Physician Assistant.

Categorical variables: Fisher’s Exact test; continuous variables: Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

General estimating equation model

Per 1 year increase in age

Between 2012 and 2014, the total number of Pap tests ordered per month decreased in all 3 groups. However, temporal trends in the proportion of non-indicated Pap tests ordered each year varied by group. In the <21 group, there was a decline in the proportion of non-indicated Pap tests over the study time period (p=0.006). In contrast, there was an increase in the proportion of non-indicated tests ordered in the posthysterectomy group during the same time period (p=0.04). The proportion of non-indicated Pap tests in the >65 group remained relatively stable over time (p=0.91).

Discussion

Cervical cancer screening at the extremes of age and posthysterectomy was performed in 35% patients in our health system despite recommendations against screening for more than a decade. The proportion of non-indicated Pap tests appeared to increase in the posthysterectomy group despite a temporal decrease in the total number of Pap tests and a concomitant decrease in the proportion of non-indicated tests in the <21 years age group. There were no common patient or health care provider characteristics associated with excess screening across all groups. Non-indicated screening is likely due to confusion about the guidelines and patient and health care provider worry that omitting screening will increase the cervical cancer incidence.

Our results build on those of previous survey studies showing that women at low risk for developing cervical cancer continue to undergo screening. A claims database study showed that 57% of women younger than age 21 years had Pap tests performed (5), and a 2010 study using data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that 58.4% of women >65 years of age and 34.1% of women posthysterectomy continued Pap testing (6).

Lack of knowledge of the guidelines is one reason for non-adherence (9). Unified guidelines were created in 2012 (1–3), but the guidelines are complex and changed frequently prior to 2012 (10, 11) and will likely become even more complicated in the future as primary Human Papillomavirus testing (12) and different guidelines for those vaccinated against Human Papillomavirus (13) are incorporated. Our chart review showed that health care providers often did not differentiate between abnormal cytology and a histologic diagnosis of dysplasia. Furthermore, the coupling of Pap tests with prenatal care increased screening in women <21 years of age.

Some health care providers distrust the guidelines. In a 2016 California survey, 35% of primary care and 59% of gynecologists did not feel that the current guidelines were clinically appropriate (14); interestingly gynecologists had lower rates of non-indicated screening in our study. Some respondents to the California survey felt that the guidelines were created to save money and that decreasing screening would result in an increased incidence of cervical cancer. Other health care providers continue screening to meet patient expectations during health maintenance visits, and many health care providers do not have adequate time to explain the guideline changes to patients (14). Lastly, some health care providers acknowledged financial incentive to continuing cervical cancer screening (14).

In this study, the increase in the proportion of non-indicated Pap tests in the posthysterectomy group may be due to a change in the total number of Pap tests performed rather than a true increase in the performance of non-indicated tests. During the study period the total number of Pap tests performed in the posthysterectomy group declined by 56% while the number of non-indicated Pap tests only decreased by 46%. This may reflect adoption of the guidelines by some while those who intentionally disregarded the guidelines continued to screen.

The strengths of this study are the large number of patients from a large health system which includes urban, suburban and rural sites and both academic and community clinics. All charts were manually reviewed; an electronic health record query alone would have inaccurately doubled the number of non-indicated Pap tests in women <21 and >65 years old, and tripled the number in posthysterectomy patients. Nonetheless, our study provides a conservative estimate of the number of non-indicated Pap tests, and the true number may be much higher. The primary limitation of our study is the fact that we could only compare the number of non-indicated Pap tests to the total number of Pap tests performed within each screening group; ideally we would have compared the number of Pap tests performed to the total number of women seen within the health system in each group, however we were unable to query the data in this way. This study was performed within a single health system, so our results may not be generalizable to other health systems. Other limitations of the study are those inherent to a retrospective chart review. Data collection was limited by the quality of documentation and we only had access to records within our electronic health record It is possible that patients had a Pap testing history outside of our system which likely resulted in an over-estimate in the number of women >65 years of age who continued screening due to inadequate previous testing.

The 2012 guidelines seek to maintain the benefits of screening while limiting potential harms, such as preterm delivery in future pregnancies following excisional procedures, increased risk of pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence following hysterectomy, or vaginal stenosis following treatment of vaginal dysplasia (2). Continued screening in populations at low risk for cervical cancer limits the protections sought by the current guidelines.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

The Masonic Cancer Center Women’s Health Scholar is sponsored by the University of Minnesota Masonic Cancer Center, a comprehensive cancer center designated by the National Cancer Institute, and administrated by the University of Minnesota Deborah E. Powell Center for Women’s Health. Research is supported by the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Grant (# K12HD055887) and administered by the University of Minnesota Deborah E. Powell Center for Women’s Health. This award is co-funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health (NICHD) and the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH). This award is also funded by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (OD), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the office views of the co-funders. Also supported by NIH grant P30 CA77598 utilizing the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Core shared resource of the Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR000114.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has indicated that he/she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Presented at the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology annual meeting, New Orleans, LA, April 13–16, 2016; and at the 2016 BIRCWH (Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health) meeting, Bethesda, MD, June 7, 2016.

References

- 1.Moyer VA. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of internal medicine. 2012 Jun 19;156(12):880–91. W312. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-12-201206190-00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, Killackey M, Kulasingam SL, Cain J, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. American journal of clinical pathology. 2012 Apr;137(4):516–42. doi: 10.1309/AJCPTGD94EVRSJCG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 131: Screening for cervical cancer. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012 Nov;120(5):1222–38. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e318277c92a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Practice Bulletin No. 168: Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016 Oct;128(4):e111–30. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirth JM, Tan A, Wilkinson GS, Berenson AB. Compliance with cervical cancer screening and human papillomavirus testing guidelines among insured young women. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2013 Sep;209(3):200, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kepka D, Breen N, King JB, Benard VB, Saraiya M. Overuse of papanicolaou testing among older women and among women without a cervix. JAMA internal medicine. 2014 Feb 1;174(2):293–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Services FH. Overview of our services. 2016 [cited 11/16/2016]; Available from: http://www.fairview.org/About/Whoweare/OverviewofOurServices/index.htm. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- 8.Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, Katki HA, Kinney WK, Schiffman M, et al. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013 Apr;121(4):829–46. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182883a34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teoh DG, Marriott AE, Isaksson Vogel R, Marriott RT, Lais CW, Downs LS, Jr, et al. Adherence to the 2012 national cervical cancer screening guidelines: a pilot study. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 Jan;212(1):62, e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saslow D, Runowicz CD, Solomon D, Moscicki AB, Smith RA, Eyre HJ, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of cervical neoplasia and cancer. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2002 Nov-Dec;52(6):342–62. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.6.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomon D, Breen N, McNeel T. Cervical cancer screening rates in the United States and the potential impact of implementation of screening guidelines. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2007 Mar-Apr;57(2):105–11. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, Davey DD, Goulart RA, Garcia FA, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 Feb;125(2):330–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossi PG, Carozzi F, Federici A, Ronco G, Zappa M, Franceschi S. Cervical cancer screening in women vaccinated against human papillomavirus infection: Recommendations from a consensus conference. Preventive medicine. 2016 Nov 25; doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boone E, Lewis L, Karp M. Discontent and Confusion: Primary Care Providers’ Opinions and Understanding of Current Cervical Cancer Screening Recommendations. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2016 Mar;25(3):255–62. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]