Abstract

Background and Objectives. β-Thalassemia and sickle cell disease are genetic disorders characterized by reduced and abnormal β-globin chain production, respectively. The elevation of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) can ameliorate the severity of these disorders. In sickle cell disease patients, the HbF level elevation is associated with three quantitative trait loci (QTLs), BCL11A, HBG2 promoter, and HBS1L-MYB intergenic region. This study elucidates the existence of the variants in these three QTLs to determine their association with HbF levels of transfusion-dependent Saudi β-thalassemia patients. Materials and Methods. A total of 174 transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia patients and 164 healthy controls from Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia were genotyped for fourteen single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from the three QTL regions using TaqMan assay on real-time PCR. Results. Genotype analysis revealed that six alleles of HBS1L-MYB QTL (rs9376090C p = 0.0009, rs9399137C p = 0.008, rs4895441G p = 0.004, rs9389269C p = 0.008, rs9402686A p = 0.008, and rs9494142C p = 0.002) were predominantly associated with β-thalassemia. In addition, haplotype analysis revealed that haplotypes of HBS1L-MYB (GCCGCAC p = 0.022) and HBG2 (GTT p = 0.009) were also predominantly associated with β-thalassemia. Furthermore, the HBS1L-MYB region also exhibited association with the high HbF cohort. Conclusion. The stimulation of HbF gene expression may provide alternative therapies for the amelioration of the disease severity of β-thalassemia.

1. Introduction

The most common hereditary hemolytic anemias are β-thalassemia and sickle cell disease (SCD). β-Thalassemia is characterized by absence or reduction of β-globin chain synthesis, while SCD is characterized by the production of abnormal β-globin chain. However, the pathophysiology of each disorder is different [1]. Both SCD and β-thalassemia are prevalent in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia and are characterized by a wide range of phenotypic heterogeneity [2–7]. Fetal hemoglobin (HbF; α2γ2) is a major genetic modifier of disease severity in SCD [8]. Elevated HbF can ameliorate the clinical and hematologic severity of the disease and persistently elevated HbF partially compensates for the lack of HbA in β-thalassemia and also decreases α/β chain imbalance and the consequent toxicity of unpaired α-globin chains [9]. In Saudi β-thalassemia patients, a highly elevated level of HbF, ranging from 40 to 98%, has been observed [10].

Understanding the regulation of HBG (γ-globin gene) expression is of both biological and clinical relevance [9]. A section of DNA locus that correlates with phenotypic variation is known as quantitative trait locus (QTL). The first identified QTL associated with an elevated HbF level was the −158 C>T, XmnI site (rs7482144), at the 5′ to HBG2 [11]. In the same region, that is, SNP rs5006884 in olfactory receptor (OR) genes (OR51B5 and OR51B6), upstream of the β-globin gene cluster has been reported to be associated with elevated HbF level in several populations. The rs2071348 in the β-globin locus is also in tight linkage disequilibrium with rs7482144 (HBG2) and is associated with elevated HbF [12]. Two other QTLs, located in the HBS1L-MYB intergenic region and in the BCL11A gene, are either directly involved in HbF gene silencing in adult life or in cell proliferation and differentiation [9, 13–15]. BCL11A (2p16.1), HBS1L-MYB (6q23.3) and HBG2 promoter regions account for approximately 10–50% of HbF variation depending on the population studied, with the remaining variance in HbF level unaccounted for, indicating that additional loci are involved [16]. More recently, a polymorphism in intron 9 of ANTXR1, a type 1 transmembrane protein and receptor for anthrax toxin, was found to be associated with elevated HbF in Saudi patients with the AI haplotype [17]. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the existence of known HbF enhancer loci, BCL11A, HBG, and HBS1L-MYB polymorphisms, and their haplotypes, in transfusion-dependent Saudi β-thalassemia patients.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a case control study conducted on 174 transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia patients (age range 2 to 18 years; 93 males and 81 females) and 164 age and sex matched healthy controls from the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. All β-thalassemia patients attending three major hospitals in the Eastern Province, namely, King Fahd Hospital of the University, Dammam; Maternity and Children's Hospital, Dammam; and King Fahd Hospital, Al-Ahssa, were requested to participate in the study. All the patients included in this study were clinically diagnosed with β-thalassemia major. In addition, the β-thalassemia mutations in the majority of these patients have been identified and reported previously [2, 7]. The HbF levels reported in this manuscript represent the first baseline measurement for these patients, who are transfused regularly every two to three weeks. The patients' mean hemoglobin was maintained at approximately above 7.0 g/dL. All the controls were randomly selected from the general population with no history or family history of β-thalassemia or SCD and from the same area.

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Dammam in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Signed written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Blood samples were collected in EDTA vacutainers and DNA was extracted using blood minikit (Qiagen, GmbH, Hilden, Germany). HbF levels were determined using Bio-Rad Variant II (Variant II β-Thalassemia Short Program Recorder Kit, Hercules, CA 94547, USA). The patient cohort was subgrouped based on HbF level, with 106 patients having a HbF level > 40% and 68 patients having a HbF level < 40%. SNP genotyping was carried out by nuclease allelic discrimination assay with target-specific forward and reverse primers along with TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) labeled with VIC and FAM for each allele on the ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fourteen SNPs, namely, rs2071348, rs7482144, and rs5006884 (HBG2 promoter region), rs766432, rs11886868, rs4671393, and rs7557939 (BCL11A region), and rs28384513, rs9376090, rs9399137, rs4895441, rs9389269, rs9402686, and rs9494142 (HBS1L-MYB region), were studied. All the SNPs were tested for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). Chi square and odds ratio was determined by SPSS version 19 to evaluate allele association. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) test was carried out using HaploView 4.2 software program to identify the nonrandom association of these 14 SNPs. Haplotype blocks were constructed using HaploView 4.2 program [18]. Haplotypes associated with β-thalassemia were inferred based on the partition-ligation approach through EM algorithm. A p value below 0.05 was considered significant for all statistical analyses.

3. Results

The mean of hemoglobin level, mean corpuscular volume, ferritin, and iron of the 174 transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia patients were 7.89 ± 1.66 g/dL, 68.93 ± 9.31 fl, 3222 ± 2396 μg/L, and 81.05 ± 70.39 μmol/L, respectively. The range of HbF in patients' cohort was 1.4 to 99.4% (83.77 ± 23.78%). Only five patients were found to have HbF level below 10% (1.4% n = 1; 5.9% n = 1; 8.1% n = 1 and 9.8% n = 2). All other patients in the low HbF cohort had a value HbF of between 10–39.1%. From the total patient group, the HbF pretransfusion level was >40% in 106 patients. All patients are treated with Deferasirox (Exjade, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Ltd., UK) an orally administered iron chelation agent. From the study group, 53 patients had splenomegaly, 20 undergone splenectomy, and 18 had bone abnormalities.

The independent segregation genotype for all the SNPs in the control group was in agreement with the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Standard allelic association analysis of the 14 SNPs tested in the patient cohort showed that only six SNPs in the HBS1L-MYB region, namely, rs9376090, rs9399137, rs4895441, rs9389269, rs9402686, and rs9494142, were significantly associated with β-thalassemia. There were no significant differences in allele frequencies of SNPs in the HBG2 promoter region and BCL11A region between the β-thalassemia and control groups (Table 1). However, when the patients were subgrouped into those who had HbF > 40% (106 patients) and those who had HbF < 40% (68 patients), the group with HbF > 40% showed a significant association with the six β-thalassemia associated SNPs, in addition to two other SNPs, namely, rs7557939 (OR = 1.54, p = 0.013) and rs11886868 (OR = 1.47, p = 0.029) on BCL11A locus. The subgroup with HbF <40% showed only rs2071348 on HBG2 promoter region to be associated with β-thalassemia (Table S1 in Supplementary Material available online at https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1972429).

Table 1.

Allelic association of 14 SNPs related to BCL11A, HBS1L-MYB, and HBG2 promoter region in patients with β-thalassemia and controls.

| SNP ID | Candidate gene | Chromosome position | Alleles (EA/OA) | Case versus control | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ 2 | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | ||||

| rs2071348 | HBG2 region | 11:5242916 | T/G | 1.184 | 0.832 (0.598–1.159) | 0.277 |

| rs7482144 | HBG2 region | 11:5254939 | C/T | 0.498 | 0.881 (0.620–1.252) | 0.480 |

| rs5006884 | HBG2 region | 11:5352021 | T/C | 1.222 | 0.818 (0.577–1.168) | 0.269 |

| rs766432 | BCL11A | 2:60492835 | A/C | 0 | 0.999 (0.719–1.388) | 0.997 |

| rs11886868 | BCL11A | 2:60493111 | T/C | 1.637 | 0.821 (0.607–1.111) | 0.201 |

| rs4671393 | BCL11A | 2:60493816 | G/A | 0.006 | 0.987 (0.709–1.375) | 0.940 |

| rs7557939 | BCL11A | 2:60494212 | A/G | 2.055 | 0.802 (0.592–1.085) | 0.152 |

| rs28384513 | HBS1L-MYB | 6:135055071 | G/T | 2.496 | 0.741 (0.511–1.075) | 0.114 |

| rs9376090 | HBS1L-MYB | 6:135090090 | C/T | 11.053 | 0.406 (0.235–0.700) | 0.0009∗ |

| rs9399137 | HBS1L-MYB | 6:135097880 | C/T | 7.228 | 0.473 (0.271–0.824) | 0.008∗ |

| rs4895441 | HBS1L-MYB | 6:135105435 | G/A | 8.785 | 0.449 (0.262–0.771) | 0.004∗ |

| rs9389269 | HBS1L-MYB | 6:135106021 | C/T | 7.096 | 0.495 (0.293–0.837) | 0.008∗ |

| rs9402686 | HBS1L-MYB | 6:135106679 | A/G | 7.096 | 0.495 (0.293–0.837) | 0.008∗ |

| rs9494142 | HBS1L-MYB | 6:135110502 | C/T | 9.936 | 0.459 (0.280–0.751) | 0.002∗ |

∗Significant association p values (p < 0.05) for the allelic model. EA: effect allele tested for association; OA: other allele; p: p value unadjusted; chromosome position as per GRCh38.p2 Assembly.

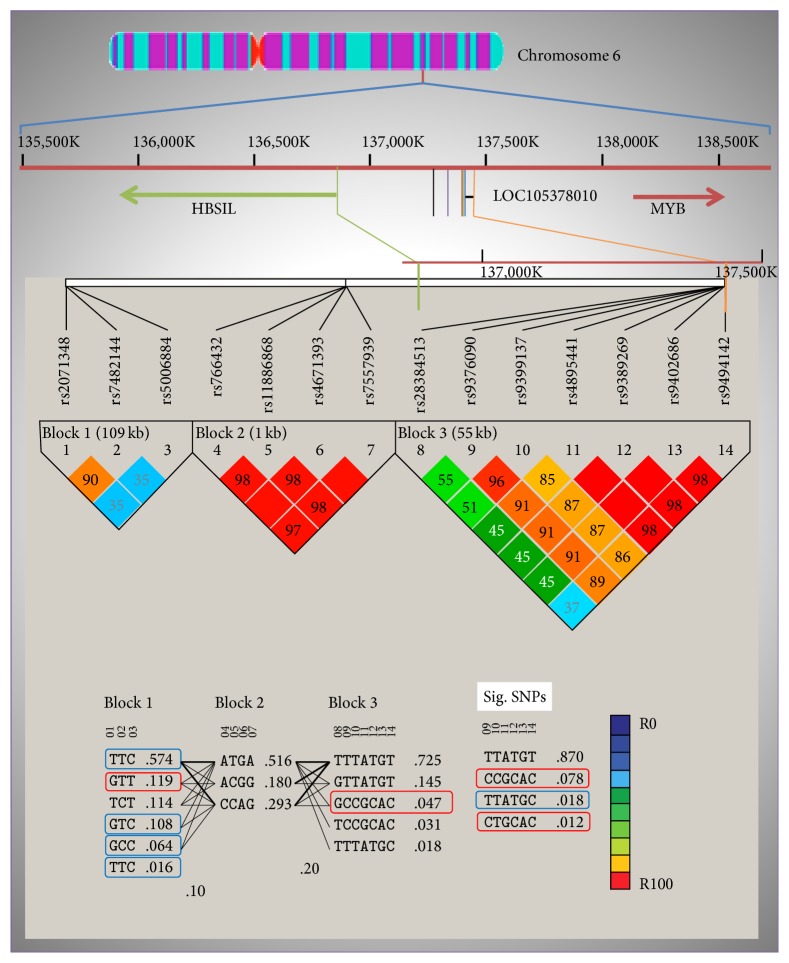

The predominant haplotypes in the whole β-thalassemia cohort consisted of GTT and TCC in the HBG2 promoter region and GCCGCAC (p = 0.022; χ2 = 5.257) in the HBS1L-MYB region (Figure 1). The CCGCAC (rs9376090C, rs9399137C, rs4895441G, rs9389269C, rs9402686A, and rs9494142C) haplotype pattern was the most significant HbF enhancer haplotype (p = 0.005; χ2 = 7.739) followed by CTGCAC (p = 0.04; χ2 = 4.181) (Table 2). The predominant haplotypes in the subgroup with HbF > 40% consisted of GTT in the HBG2 promoter region, ATGA in BCL11A, and GCCGCAC in the HBS1L-MYB region. The predominant haplotypes in the subgroup with HbF < 40% consisted of TCC in the HBG2 promoter region (Table S2).

Figure 1.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis patterns between 3 HBG2, 4 BCL11A, and 7 HBS1L-MYB SNPs compared in thalassemia patients against control cohort. The figure illustrates the chromosome 6 loci inhabiting the seven HBS1L-MYB interregion SNPs outlining the chromosomal location, SNP ID, and the positions that were genotyped in this study. HaploView output of LD across 14 SNPs from the genotyping data in Saudi population. The pairwise correlation between the SNPs was measured as r2 and shown (×100) in each diamond. Enhancer haplotypes are in red boxes and diminisher haplotypes are in blue boxes. Coordinates are according to the NCBI build dbSNP 144 Homo sapiens annotation release 107 (reference sequence NT_025741.16). Sig. SNPs: haplotypes of significant SNPs.

Table 2.

Frequency of haplotypes of SNPs in HBG2, BCL11A, and HBS1L-MYB compared between patients with β-thalassemia and control cohorts.

| Block | Candidate gene | Haplotype | Case versus control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall frequency | Case; control frequencies | χ 2 | p value | |||

| 1 | HBG2 region | TCC | 0.574 | 0.618, 0.528 | 5.652 | 0.0174ϕ |

| HBG2 region | GTT | 0.119 | 0.150, 0.086 | 6.767 | 0.0093∗ | |

| HBG2 region | TCT | 0.114 | 0.103, 0.126 | 0.907 | 0.3409 | |

| HBG2 region | GTC | 0.108 | 0.079, 0.138 | 6.136 | 0.0132ϕ | |

| HBG2 region | GCC | 0.064 | 0.044, 0.085 | 4.858 | 0.0275ϕ | |

| HBG2 region | TTC | 0.016 | 0.003, 0.029 | 7.306 | 0.0069ϕ | |

|

| ||||||

| 2 | BCL11A | ATGA | 0.516 | 0.540, 0.491 | 1.648 | 0.1992 |

| BCL11A | CCAG | 0.293 | 0.290, 0.296 | 0.025 | 0.8752 | |

| BCL11A | ACGG | 0.18 | 0.158, 0.204 | 2.439 | 0.1183 | |

|

| ||||||

| 3 | HBS1L-MYB | TTTATGT | 0.725 | 0.692, 0.760 | 3.898 | 0.0484 |

| HBS1L-MYB | GTTATGT | 0.145 | 0.139, 0.152 | 0.243 | 0.6223 | |

| HBS1L-MYB | GCCGCAC | 0.047 | 0.065, 0.028 | 5.257 | 0.0219∗ | |

| HBS1L-MYB | TCCGCAC | 0.031 | 0.041, 0.021 | 2.25 | 0.1336 | |

| HBS1L-MYB | TTTATGC | 0.018 | 0.023, 0.012 | 1.13 | 0.2877 | |

|

| ||||||

| Significant SNPs | HBS1L-MYB | TTATGT | 0.87 | 0.830, 0.912 | 9.837 | 0.0017ϕ |

| HBS1L-MYB | CCGCAC | 0.078 | 0.106, 0.049 | 7.739 | 0.0054∗ | |

| HBS1L-MYB | TTATGC | 0.018 | 0.023, 0.012 | 1.15 | 0.2835 | |

| HBS1L-MYB | CTGCAC | 0.012 | 0.020, 0.003 | 4.181 | 0.0409∗ | |

∗Significant risk haplotypes (p < 0.05). Order of significant SNPs: rs9376090, rs9399137, rs4895441, rs9389269, rs9402686, and rs9494142. ϕHaplotype associated with low HbF levels.

4. Discussion

Human erythroid progenitor based functional studies revealed that reduced transcription factor bindings, which could affect long-range interactions with MYB due to common variants within the intergenic region (HBS1L-MYB), result in reduced MYB expression leading to elevated HbF levels [19]. In addition, common variants have been identified to be associated with elevated HbF in the BCL11A region and HBG2 promotor region in SCD [20]. The stimulation of HbF expression may provide alternative therapies for the amelioration of disease severity in β-thalassemia and SCD [21]. Increased knowledge and understanding of the genetics of HbF regulation supports the development of innovative therapeutic targets, including the development of novel drug therapies.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting the influence of 14 genetic markers spanning the three important QTLs, namely, HBG2 promoter, BCL11A, and HBS1L-MYB regions in β-thalassemia major patients. In this study, we examined selected SNPs in the BCL11A, HBG2, and HBS1L-MYB loci on chromosomes 11p15.4, 2p16.1, and 6q23.3, respectively, in Saudi β-thalassemia patients from the Eastern Province to determine their association with HbF levels. The selection of the SNPs was based on recently published studies, which reported that these genetic variants were most strongly associated with increased HbF levels in SCD and β-thalassemia intermedia type of patients [9, 20, 22–28].

Six of the 14 SNPs in the HBS1L-MYB region showed a strong association with β-thalassemia. This is consistent with previous reports from European, Chinese and African β-thalassemia intermedia and SCD patients [9, 13, 20, 22, 23, 25, 26, 28]. However, two of these SNPs (rs4895441 and rs93991370) did not show an association in SCD patients from the South-Western Province of Saudi Arabia [3]. It has to be noted that SCD in the Eastern Province carries the Arab-Indian haplotype, while in the South-Western Province, SCD patients carry the Benin haplotype [3].

The effects of BCL11A QTL on HbF levels have been reported in β-thalassemia intermedia in different populations [29, 30]. In the present study, two SNPs, namely, rs7557939 and rs11886868, were found to be associated with β-thalassemia in patients with HbF level > 40%. The other SNPs in the same region showed a lack of association with β-thalassemia, in contrast to other studies conducted on Chinese and Portuguese populations [28, 31]. The lack of association with the transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia major and association with the Hb E/β-thalassemia cases [31] and beta-thalassemia carriers [28] suggests that rs4671393, rs7557939, and rs11886868 are HbF enhancer SNPs in β-thalassemia intermedia.

It has been reported that the XmnI Gγ-158(C→T) polymorphism (rs7482144) of HBG2 was associated with increased production of Gγ globin, and hence HbF can influence the heterogeneity of both blood transfusion-dependent and transfusion-independent β-thalassemia patients [32–37]. Although this SNP was reported to be associated with β-thalassemia in a number of populations, in our cohort this association is lacking [24, 38]. Moreover, other SNPs (rs2071348 and rs5006884) in the HBG2 promoter region were shown to lack an association with β-thalassemia in our cohort.

Haplotype analysis showed that CCGCAC in the HBS1L-MYB region is strongly associated with β-thalassemia in our cohort (χ2 = 7.739; p = 0.005), while in the HBG2 region the haplotypes GTT (χ2 = 6.767; p = 0.009) and TCC (χ2 = 5.652; p = 0.017) showed a strong association with β-thalassemia. Paucity of literature on the GTT haplotypes among β-thalassemia prevents the comparison of their effect.

The haplotype analysis of present and previous studies of the SNPs from the three tested regions (HBG2 locus, BCL11A, and the HBS1L-MYB interregion) showed stronger association with elevated HbF level than single SNPs taken individually [15, 39]. Moreover, it has been shown that the distribution of BCL11A enhancer haplotypes showed significant differences based on geographical origin accounting for the HbF level deviation [40]. Interestingly, the ATGA haplotype formed from the four SNPs rs766432, rs11886868, rs4671393, and rs7557939, though it lacked an association with β-thalassemia major. However, this haplotype was found to be associated with HbF in the subgroup of patients with HbF > 40%. This haplotype has been previously reported to be associated with elevated HbF in Saudi SCD patients from the Eastern Province [40].

5. Conclusion

The stimulation of HbF expression may provide alternative therapies for the amelioration of the disease severity of β-thalassemia and SCD. Furthermore, increasing knowledge and understanding of the genetics of HbF regulation will support the development of innovative therapeutic targets, including the development of novel drug therapies. Therefore, our study provided valuable insights on the elements that influence elevated HbF levels in β-thalassemia.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Allelic association of 14 SNPs related to BCL11A, HBS1L-MYB, and HBG2 promoter region in patients with β-thalassemia and elevated HbF levels. Table S2: Frequency of haplotypes of SNPs in HBG2, BCL11A, and HBS1L-MYB compared between High HbF and Control cohorts.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology for funding the project (to Dr. Cyril Cyrus, Grant no. LGP 31-34). They also thank Mr. Geoffrey James Tam Moro and Mr. Mohammed Al Shamlan for their technical and administrative support.

Competing Interests

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contributions

Cyril Cyrus, Chittibabu Vatte, and Shahanas Chathoth designed the study, performed the assay, and drafted the manuscript. Zaki A. Nasserullah and Ahmed Sulaiman provided the β-thalassemia patient samples; Hatem Qutub and Amein K. Al Ali provided the age and sex matched controls. Sana Al Jarrash and Hatem Qutub collected all medical data of the individual participant from the hospital records. J. Francis Borgio performed the HaploView analyses. Martin H. Steinberg and Alhusain J. Alzahrani were involved in drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content. Abdullah Al-Rubaish and Amein K. Al Ali provided critical review of the manuscript. All authors made significant intellectual contributions and have read and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- 1.Ataga K. I., Cappellini M. D., Rachmilewitz E. A. β-Thalassaemia and sickle cell anaemia as paradigms of hypercoagulability. British Journal of Haematology. 2007;139(1):3–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Ali A. K., Al-Ateeq S., Imamwerdi B. W., et al. Molecular bases of β-thalassemia in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2005;2005(4):322–325. doi: 10.1155/JBB.2005.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alsultan A., Solovieff N., Aleem A., et al. Fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell anemia: Saudi patients from the Southwestern province have similar HBB haplotypes but higher HbF levels than African Americans. American Journal of Hematology. 2011;86(7):612–614. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akhtar M. S., Qaw F., Francis Borgio J., et al. Spectrum of α-thalassemia mutations in transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia patients from the eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Hemoglobin. 2013;37(1):65–73. doi: 10.3109/03630269.2012.753510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borgio J. F., AbdulAzeez S., Al-Nafie A. N., et al. A novel HBA2gene conversion in cisor trans: ‘α12 allele’ in a Saudi population. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2014;53(4):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Nafie A. N., Borgio J. F., AbdulAzeez S., et al. Co-inheritance of novel ATRX gene mutation and globin (α & β) gene mutations in transfusion dependent beta-thalassemia patients. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2015;55(1):27–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borgio J. F., AbdulAzeez S., Naserullah Z. A., et al. Mutations in the β-globin gene from a Saudi population: an update. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology. 2016;38(2):e38–e40. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ngo D. A., Steinberg M. H. Genomic approaches to identifying targets for treating β hemoglobinopathies. BMC Medical Genomics. 2015;8(1, article 44) doi: 10.1186/s12920-015-0120-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uda M., Galanello R., Sanna S., et al. Genome-wide association study shows BCL11A associated with persistent fetal hemoglobin and amelioration of the phenotype of β-thalassemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(5):1620–1625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711566105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Awamy B. H. Thalassemia syndromes in Saudi Arabia: meta-analysis of local studies. Saudi Medical Journal. 2000;21(1):8–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labie D., Dunda-Belkhodja O., Rouabhi F., Pagnier J., Ragusa A., Nagel R. L. The -158 site 5′ to the G gamma gene and G gamma expression. Blood. 1985;66:1463–1465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solovieff N., Milton J. N., Hartley S. W., et al. Fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell anemia: genome-wide association studies suggest a regulatory region in the 5′ olfactory receptor gene cluster. Blood. 2010;115(9):1815–1822. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menzel S., Jiang J., Silver N., et al. The HBS1L-MYB intergenic region on chromosome 6q23.3 influences erythrocyte, platelet, and monocyte counts in humans. Blood. 2007;110(10):3624–3626. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-093419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thein S. L., Menzel S., Peng X., et al. Intergenic variants of HBS1L-MYB are responsible for a major quantitative trait locus on chromosome 6q23 influencing fetal hemoglobin levels in adults. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(27):11346–11351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611393104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galarneau G., Palmer C. D., Sankaran V. G., Orkin S. H., Hirschhorn J. N., Lettre G. Fine-mapping at three loci known to affect fetal hemoglobin levels explains additional genetic variation. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(12):1049–1051. doi: 10.1038/ng.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borg J., Papadopoulos P., Georgitsi M., et al. Haploinsufficiency for the erythroid transcription factor KLF1 causes hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(9):801–807. doi: 10.1038/ng.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vinod V., Farrell J. J., Wang S., et al. A candidate trans-acting modulator of fetal hemoglobin gene expression in the Arab-Indian haplotype of sickle cell anemia. American Journal of Hematology. 2016;91(11):1118–1122. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrett J. C., Fry B., Maller J., Daly M. J. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stadhouders R., Aktuna S., Thongjuea S., et al. HBS1L-MYB intergenic variants modulate fetal hemoglobin via long-range MYB enhancers. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2014;124(4):1699–1710. doi: 10.1172/jci71520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thein S. L., Menzel S., Lathrop M., Garner C. Control of fetal hemoglobin: new insights emerging from genomics and clinical implications. Human Molecular Genetics. 2009;18(2):R216–R223. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atweh G. F., Loukopoulos D. Pharmacological induction of fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. Seminars in Hematology. 2001;38(4):367–373. doi: 10.1016/s0037-1963(01)90031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lettre G., Sankaran V. G., Bezerra M. A. C., et al. DNA polymorphisms at the BCL11A, HBS1L-MYB, and β-globin loci associate with fetal hemoglobin levels and pain crises in sickle cell disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(33):11869–11874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804799105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creary L. E., Ulug P., Menzel S., et al. Genetic variation on chromosome 6 influences F cell levels in healthy individuals of African descent and HbF levels in sickle cell patients. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004218.e4218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen T. K. T., Joly P., Bardel C., Moulsma M., Bonello-Palot N., Francina Alain A. The XmnI Gγ polymorphism influences hemoglobin F synthesis contrary to BCL11A and HBS1L-MYB SNPs in a cohort of 57 β-thalassemia intermedia patients. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2010;45(2):124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makani J., Menzel S., Nkya S., et al. Genetics of fetal hemoglobin in Tanzanian and British patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2011;117(4):1390–1392. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farrell J. J., Sherva R. M., Chen Z.-Y., et al. A 3-bp deletion in the HBS1L-MYB intergenic region on chromosome 6q23 is associated with HbF expression. Blood. 2011;117(18):4935–4945. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-317081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cardoso G. L., Diniz I. G., Martins da Silva A. N. L., et al. DNA polymorphisms at BCL11A, HBS1L-MYB and Xmn1-HBG2 site loci associated with fetal hemoglobin levels in sickle cell anemia patients from Northern Brazil. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2014;53(4):176–179. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira C., Relvas L., Bento C., Abade A., Ribeiro M. L., Manco L. Polymorphic variations influencing fetal hemoglobin levels: association study in beta-thalassemia carriers and in normal individuals of Portuguese origin. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2015;54(4):315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menzel S., Garner C., Gut I., et al. A QTL influencing F cell production maps to a gene encoding a zinc-finger protein on chromosome 2p15. Nature Genetics. 2007;39(10):1197–1199. doi: 10.1038/ng2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sedgewick A. E., Timofeev N., Sebastiani P., et al. BCL11Ais a major HbF quantitative trait locus in three different populations with β-hemoglobinopathies. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2008;41(3):255–258. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He Y., Chen P., Lin W., Luo J. Analysis of rs4671393 polymorphism in hemoglobin E/β-thalassemia major in guangxi province of China. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2012;34(4):323–324. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3182370bff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thein S. L., Wainscoat J. S., Sampietro M., et al. Association of thalassaemia intermedia with a beta-globin gene haplotype. British Journal of Haematology. 1987;65(3):367–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1987.tb06870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fucharoen S., Siritanaratkul N., Winichagoon P., et al. Hydroxyurea increases hemoglobin F levels and improves the effectiveness of erythropoiesis in β-thalassemia/hemoglobin E disease. Blood. 1996;87(3):887–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dedoussis G. V., Mandilara G. D., Boussiu M., et al. HbF production in beta thalassaemia heterozygotes for the IVS-II-1 G–>A beta(0)-globin mutation Implication of the haplotype and the (G) gamma-158 C–>T mutation on the HbF level. American Journal of Hematology. 2000;64(3):151–155. doi: 10.1002/1096-8652(200007)64:3<151::aid-ajh2>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alebouyeh M., Moussavi F., Haddad-Deylami H., Vossough P. Hydroxyurea in the treatment of major β-thalassemia and importance of genetic screening. Annals of Hematology. 2004;83(7):430–433. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0836-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olivieri N. F., Muraca G. M., O'Donnell A., Premawardhena A., Fisher C., Weatherall D. J. Studies in haemoglobin E beta-thalassaemia. British Journal of Haematology. 2008;141(3):388–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nuntakarn L., Fucharoen S., Fucharoen G., Sanchaisuriya K., Jetsrisuparb A., Wiangnon S. Molecular, hematological and clinical aspects of thalassemia major and thalassemia intermedia associated with Hb E-β-thalassemia in Northeast Thailand. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2009;42(1):32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dabke P., Colah R., Ghosh K., Nadkarni A. Effect of cis acting potential regulators in the β globin gene cluster on the production of HbF in thalassemia patients. The Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases. 2013;5(1) doi: 10.4084/mjhid.2013.012.e2013012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bauer D. E., Kamran S. C., Lessard S., et al. An erythroid enhancer of BCL11A subject to genetic variation determines fetal hemoglobin level. Science. 2013;342(6155):253–257. doi: 10.1126/science.1242088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sebastiani P., Farrell J. J., Alsultan A., et al. BCL11A enhancer haplotypes and fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell anemia. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2015;54(3):224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Allelic association of 14 SNPs related to BCL11A, HBS1L-MYB, and HBG2 promoter region in patients with β-thalassemia and elevated HbF levels. Table S2: Frequency of haplotypes of SNPs in HBG2, BCL11A, and HBS1L-MYB compared between High HbF and Control cohorts.