Abstract

We examined profiles of sibling relationship qualities in 246 Mexican-origin families living in the United States using latent profile analyses. Three profiles were identified: Positive, Negative and Affect-Intense. Links between profiles and youths’ familism values and adjustment were assessed using longitudinal data. Siblings in the Positive profile reported the highest familism values, followed by siblings in the Affect-Intense profile and, finally, siblings in the Negative profile. Older siblings in the Positive and Affect-Intense profiles reported fewer depressive symptoms than siblings in the Negative profile. Further, in the Positive and Negative profiles, older siblings reported less involvement in risky behaviors than younger siblings. In the Negative profile, younger siblings reported greater sexual risk behaviors in late adolescence than older siblings; siblings in opposite-sex dyads, as compared to same-sex dyads, engaged in riskier sexual behaviors. Our findings highlight sibling relationship quality as promotive and risky, depending on sibling characteristics and adjustment outcomes.

Keywords: adjustment, adolescence, Mexican-origin, siblings

Sibling Relationship Quality and Mexican-Origin Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Familism Values and Adjustment

Sibling relationships are multidimensional demonstrating a “love-hate” relationship (Dunn, 1993). Research with European American and African American youth using a person-oriented approach (Bergman, Magnusson, & El-Khouri, 2003), suggests that there is variability across families in the patterns of positive and negative sibling relationship qualities, and that these patterns are associated with youth well-being (e.g., McGuire, McHale, & Updegraff, 1996; McHale, Whiteman, Kim, & Crouter, 2007). In the present study, using an ethnic-homogeneous design, we extend this work to two-parent Mexican-origin families living in a metropolitan area of the southwestern United States where the Latino population is 40% (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014) and primarily composed of Latino individuals of Mexican descent (91%; Pew Research Center, 2011). Siblings are an important part of family life in Mexican American culture: (a) Mexican-origin youth spend more time in shared activities with siblings than parents or peers (Updegraff, McHale, Killoren, & Rodríguez, 2010); and (b) individuals of Mexican origin hold strong values regarding family support and interdependence (Cauce & Domenech-Rodríguez, 2002). Yet, we know little about sibling dynamics and their links to youth adjustment in this large and rapidly growing segment of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). The goals of the present study were: (a) to identify profiles of sibling relationship qualities in Mexican-origin families in the U.S.; and (b) to examine how these profiles in early and middle adolescence were associated with subsequent familism values and adjustment five and eight years later and to test birth order and sibling sex constellation as moderators of these associations.

Sibling Relationship Profiles

Our first goal was to identify different profiles of U.S. Mexican-origin adolescents’ sibling relationships in early/middle adolescence. Examining positive and negative relationship qualities simultaneously is important because these dimensions do not exist in isolation (Dunn, 1993) and how these dimensions work together has different implications for youth well-being and family dynamics (McGuire et al., 1996; McHale et al., 2007). For example, sibling negativity is associated with poorer family dynamics when it occurs in the absence versus the presence of sibling warmth (McGuire et al., 1996). Research exploring sibling relationship patterns has focused on three dimensions: intimacy, negativity (McGuire et al., 1996), and control (McHale et al., 2007). In European American families, four profiles were identified using a grouping strategy and cluster analysis (McGuire et al., 1996): harmonious (high intimacy, low negativity), hostile (low intimacy, high negativity), affect-intense (high intimacy, high negativity), and uninvolved (low intimacy, low negativity). McHale et al. (2007) found three profiles among African American youth using cluster analysis: positive (high intimacy, average or low negativity/control); negative (low intimacy, high negativity/control); and distant (low intimacy, negativity/control).

We extended this work to U.S. Mexican-origin siblings’ perspectives of intimacy, negativity, and control. We anticipated that positive and negative profiles would emerge, but that a distant profile may be less likely given the salience of family relationships in this cultural context (Cauce & Domenech- Rodríguez, 2002). Because Mexican-origin adolescent siblings spend a great deal of time together (Updegraff, McHale, Whiteman, Thayer, & Delgado, 2005) and are socialized to value their families, it is unlikely that they would have uninvolved relationships.

A strength of our design is that we can test how sibling profiles are linked to siblings’ cultural values to provide insights about how aspects of this cultural context are associated with variability in sibling dynamics. We focused on siblings’ familism values, which reflect a salient Mexican cultural value emphasizing family support and interdependence. Previous work shows that Latino adolescents (primarily Mexican-origin) reported stronger familism values than European American adolescents (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999). Moreover, stronger familism values have been associated with positive sibling relationships (Updegraff et al., 2005). We expected that siblings in a positive profile would describe stronger familism values than siblings in other profiles.

Sibling Relationship Profiles and Adolescent/Young Adult Adjustment

Adolescence is an important developmental period to study links between sibling profiles and siblings’ adjustment problems, as sibling relationships provide a critical foundation of support or risk (Kim, McHale, Crouter, & Osgood, 2007). In this study, sibling relationships may have implications for younger siblings as they transition through adolescence, a period characterized by increases in depression and risky behaviors (Zahn-Waxler, Shirtcliff, & Marceau, 2008), and for older siblings as they navigate the complexities of becoming young adults in the U.S. The consideration of sibling relationship profile-adjustment linkages is also significant from a public health perspective: U.S. Latinos (65% Mexican origin; U.S. Census Bureau, 2014) face disproportionate risk for negative outcomes, including high rates of depression (Gore & Aseltine, 2003), delinquency (CDC, 2007), and sexual risk behaviors (CDC, 2011). Although our study focuses on Mexican-origin adolescents/young adults, we draw on work examining U.S. Latinos as many studies do not examine national origin subgroups separately. Most research examining family correlates of Latino adolescents’ adjustment focuses on parent-adolescent relationships. For instance, previous work has revealed that more supportive parent-adolescent relationships are associated with positive adjustment (Ozer, Flores, Tschann, & Pasch, 2011). Given evidence that sibling relationships are a prominent part of family life and that siblings share contexts outside the family where these risk behaviors may occur, it is important to consider whether sibling relationship dynamics are linked to Latino adolescents’/young adults’ subsequent adjustment.

Our second goal was to investigate associations between sibling relationship profiles in early/middle adolescence and younger and older siblings’ adjustment five and eight years later, accounting for prior adjustment. Drawing from a risk and resilience perspective (Rutter, 1987) and attending to patterns of developmental progression in adjustment, we examined the associations between sibling profile membership and adolescents’ depressive symptoms, risky behaviors, and sexual risk behaviors to provide insights into how U.S. Mexican-origin adolescents’ sibling relationships in early/middle adolescence are associated with subsequent adjustment in late adolescence/young adulthood. Our consideration of birth order and sibling sex constellation as moderators was informed by social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) and research documenting that relationship-adjustment linkages differ by sibling characteristics (e.g., Kim et al., 2007).

Using a risk and resilience perspective, researchers have documented the protective benefits of sibling intimacy (McHale et al., 2007) and the risks associated with sibling negativity/control (Solmeyer, McHale, & Crouter, 2014), particularly in the absence of positivity (McGuire et al., 1996). This is in accordance with Rutter’s (1987) work on resilience, in which he identified family cohesion as a protective factor (leads to positive outcomes despite exposure to risk) and family discord as a risk factor (leads to negative outcomes). Protective factors such as close family relationships may enhance an individual’s self-esteem, leading to better adjustment (Rutter, 1987). Sameroff (1999) introduced promotive factors, which have a positive effect regardless of risk exposure; thus, we use “promotive factor” when describing the positive effect that intimate sibling relationships may have on adolescents’/young adults’ outcomes. Intimate sibling relationships have been associated with stronger ethnic identity among African American youth (McHale et al., 2007). Alternatively, family discord (i.e., sibling conflict) is associated with involvement in risky behaviors (McHale et al.). Researchers hypothesize that adolescents learn negative interaction styles when they engage in high levels of hostility with their siblings (Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1990), which they generalize to their peer relationships. This negative interaction style increases the likelihood adolescents will befriend deviant peers, resulting in risky behavior involvement (Patterson et al., 1990). We expected that sibling relationships characterized by high levels of negativity/control and low intimacy would be related to more adjustment problems. Further, sibling relationships characterized by patterns of high intimacy and low negativity/control would be associated with fewer adjustment problems.

Current Study

Our first goal was to identify profiles of sibling relationship qualities among a sample of U.S. Mexican-origin adolescent siblings in early/middle adolescence. Based on research with European American (McGuire et al., 1996) and African American samples in the U.S. (McHale et al., 2007), we expected two profiles reflecting positive and negative sibling relationships, but did not anticipate an uninvolved profile. Our second goal was to examine associations between these profiles and older and younger siblings’ familism values, depressive symptoms, risky behavior involvement, and sexual risk behaviors five and eight years later. We hypothesized that positive sibling relationships would be associated with fewer adjustment problems, whereas negative sibling relationships would be linked to future adjustment difficulties. Further, we explored sibling characteristics as moderators of the links between sibling profiles and adjustment problems. Covariates for our first goal included mothers’ nativity, family income, and youths’ familism values, as they have been associated with sibling relationship qualities (Updegraff et al., 2005). By including familism values as a covariate in our profile analyses we account for variance in familism values reported by siblings. For our second goal, to determine the unique effects of siblings on later familism values and adjustment, we controlled for adolescents’ familism values/adjustment in early/middle adolescence, and family income. We also accounted for parent-adolescent acceptance given its association with adolescent adjustment in prior work (Ozer et al., 2011; Author Citation).

Method

Participants

Data came from a longitudinal study of 246 Mexican-origin families in the U.S. (Author Citation). Participants were recruited through schools in the Phoenix, Arizona area; 40% of the population is Latino (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014), and 91% of Latinos in Arizona are of Mexican origin (Pew Research Center, 2011).

To recruit families, letters and brochures describing the study (in Spanish and English) were sent to families with 7th graders of Latino origin in five public school districts and five parochial schools. Follow-up telephone calls were conducted by bilingual staff to determine each family’s eligibility in participating in the project. A total of 1,851 letters were sent, but for 396 families, the contact information was incorrect and no updated information was available; an additional 146 families refused to be screened. Eligible families included 421 families (32% of those we contacted and screened), and 284 of these families (67%) agreed to participate, 95 (23%) refused, and 42 (10%) moved before we completed the recruitment process. Interviews were completed with 246 families.

At Time 1 (T1), median family income was $40,000. The percentage of families that met federal poverty guidelines was 18.3%, similar to the 18.6% of two-parent Mexican-origin families living in poverty in the county from which the sample was drawn (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). Parents completed an average of 10 years of education (M = 10.34; SD = 3.74 for mothers, and M = 9.88; SD = 4.37 for fathers). Most parents were born outside the U.S. (70%), and completed their interviews in Spanish (67%). Thirty-eight percent of younger and 47% of older siblings were born in Mexico and 83% of siblings were interviewed in English. At T1, younger siblings and older siblings were 12.77 (SD = .58) and 15.70 (SD = 1.60) years of age, respectively. Sibling sex constellation (older sibling-younger sibling) was as follows: sister-sister dyads (n = 68), sister-brother dyads (n = 55), brother-sister dyads (n = 57), brother-brother dyads (n = 66).

Retention rates were 75% and 70% for Time 2 or T2 (five years after T1) and Time 3 or T3 (eight years after T1), respectively. Those who did not participate could not be located (n = 43 at T2; n = 45 at T3), had moved to Mexico (n = 2 at T2; n = 4 at T3), could not presently participate (n = 8 at T2; n = 4 at T3), or refused to participate (n = 8 at T2; n = 8 at T3). Participating families reported higher maternal education and family income at T1 versus non-participating families at T2 and T3 (see Author Citation for detailed information).

Procedure

Data were collected during home interviews. Interviews were conducted individually using laptops by bilingual interviewers and lasted an average of three hours for parents and two hours for adolescents. All questions were read aloud to participants in either English or Spanish. Honorariums were $100 and $125 for each family at T1 and T2, respectively, and $75 for each family member at T3. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board. Measures were forward translated to Spanish and back translated to English by separate individuals for local Mexican dialect. Discrepancies were resolved by the research team.

Measures

For all measures, higher scores indicate higher levels of the construct name.

Family Background (T1)

Mothers and fathers reported on their annual income, years living in the U.S., number of children in the home, and siblings’ ages. The family income score was created by adding mothers’ and fathers’ reports of income from employment with log transformation applied to correct for skewness. A sibling dyad sex constellation was calculated (opposite-sex dyads = 0; same-sex dyads = 1).

Sibling Relationship Qualities (T1)

Intimacy was measured using an 8-item scale (Blyth & Foster-Clark, 1987). Items (e.g., “How much do you go to sister/brother for advice or support?”) were rated by each sibling on a 5-point scale (1) not at all to (5) very much. Cronbach’s alphas were above .81. Sibling negativity was measured using a 5-item subscale of the Network Relationship Inventory (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985), assessing the extent of disagreements and negative affect between siblings (e.g., “How much do you and sister/brother get upset or mad at each other?”). Older and younger siblings completed items using a 5-point scale from (1) not at all to (5) very much. Cronbach’s alphas were above .89. Sibling control was assessed using an 8-item measure (Stets, 1995). Siblings rated interpersonal control (both behavioral and psychological) by the other sibling using a 5-point scale (1) never to (5) very often. Example items include “My sister/brother keeps me from doing things she/he doesn’t like”; “My sister/brother decides what we do when we are together”; “My sister/brother expects that everything will be done his/her way”; and “In our relationship, my sister/brother is the boss”. Cronbach’s alphas were .76 for both siblings (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean (and Standard Deviations) for Study Variables

| Variables | Older sibling | Younger sibling | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | |

| Sibling Relationship Quality | ||||

| Intimacy | 3.30 | (.78) | 3.36 | (.73) |

| Negativity | 3.15 | (.94) | 3.09 | (.89) |

| Control | 2.00 | (.65) | 2.41 | (.73) |

| Familism values | ||||

| Familism values T1 | 4.23 | (.60) | 4.26 | (.52) |

| Familism values T2 | 4.12 | (.50) | 4.15 | (.48) |

| Familism values T3 | 4.28 | (.45) | 4.34 | (.40) |

| Adjustment Outcomes | ||||

| Depressive symptoms T1 | 17.19 | (9.81) | 16.43 | (9.88) |

| Depressive symptoms T2 | 12.88 | (9.36) | 13.31 | (9.50) |

| Depressive symptoms T3 | 12.66 | (9.49) | 13.39 | (8.94) |

| Risky behaviors T1 | 1.48 | (.43) | 1.36 | (.39) |

| Risky behaviors T2 | 1.45 | (.37) | 1.55 | (.42) |

| Risky behaviors T3 | 1.42 | (.38) | 1.47 | (.40) |

| Sexual intentions T1 | 2.15 | (1.11) | 1.52 | (.77) |

| Sexual risk behaviors T21 | −0.02 | (.76) | 0.04 | (.77) |

| Sexual risk behaviors T31 | 0.01 | (.77) | 0.02 | (.75) |

Note. N = 246. T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2, and T3 = Time 3. Range: Sibling relationship qualities and familism values (1–5), depressive symptoms (0–3), risky behaviors (1–4).

Standardized means for the average scale score for the three items.

Familism Values (T1 covariate, T2, T3; see Table 1)

Familism values were measured with the 16-item familism subscale of the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (Knight et al., 2010). Items (e.g., “It is always important to be united as a family”) were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) and averaged to create an overall score (α’s were above .84).

Adjustment Outcomes (T1 covariate, T2, T3; see Table 1)

Adolescents rated their depressive symptoms using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Items (e.g., “During the past month, I was bothered by things that don’t usually bother me”) were rated on a scale ranging from (0) rarely or none of the time to (3) most of the time. Scores were summed (α’s were above .76). The risky behaviors scale (Eccles & Barber, 1990) assessed adolescents’ involvement in 23 risky behaviors (e.g., “Stolen something worth $50 or more?”) rated on a 4-point scale ranging from (1) never to (4) more than ten times. Scores were averaged (α’s were greater than .86).

The sexual risk behaviors scale (Harris et al., 2009) assessed adolescents’ involvement in risky sexual behaviors in the past 12 months using three items: (a) the number of sexual partners; (b) the frequency of sexual relations under the influence of drugs or alcohol; and (c) the frequency of sexual relations without contraception. The last two items were rated on a 4-point scale (1) never to (4) more than 10 times. In this sample, older siblings averaged 2.05 (SD = 2.55) and 2.28 (SD = 3.31) sexual partners at T2 and T3, respectively, and younger siblings averaged 1.06 (SD = 1.73) sexual partners at T2 and 1.83 (SD = 2.25) at T3. Frequency of sexual relations under the influence of drugs and alcohol averaged 1.61 (SD = 0.91) and 1.73 (SD = 0.97) for older siblings at T2 and T3, respectively, and 1.27 (SD = 0.71) and 1.47 (SD = 0.88) for younger siblings at T2 and T3, respectively. Frequency of sexual relations without contraception averaged 1.88 (SD = 1.11) and 2.23 (SD = 1.18) for older siblings at T2 and T3, respectively, and 1.64 (SD = 0.99) and 1.98 (SD = 1.15) for younger siblings at T2 and T3, respectively. These items were standardized and the average was used as the scale score.

T1 adjustment measures were used as covariates, with the exception of sexual risk behaviors, which were not measured at T1. We included a measure of sexual intentions as a control for sexual risk behaviors (East, 1998). Older and younger siblings reported on their intentions to engage in sexual intercourse (e.g., “How likely is it that you will have sexual intercourse in the next year?’) using the average score of a 5-item measure (1 = very unlikely/very unsure to 5 = very likely/very sure). Cronbach’s alphas were above .86.

Parent-Adolescent Acceptance (T1; covariate)

Mothers and fathers completed an 8-item parent version of the acceptance subscale of the Children’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (Schwarz, Barton-Henry, & Pruzinsky, 1985). Each parent reported on their relationship with older and younger siblings. Eight items (e.g., “I am able to make ‘child’s name’ feel better when he/she is upset”) were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from (1) almost never to (5) almost always. Cronbach’s alphas were above .80 for mothers’ and fathers’ reports. The average of mothers’ and fathers’ acceptance, created separately for older (M = 4.18; SD =.48) and younger siblings (M = 4.21; SD = .45), were included as covariates.

Results

To address Goal 1, latent profile analysis (LPA) in Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) was used to identify profiles of sibling relationship quality using older and younger siblings’ reports of intimacy, conflict, and control. LPA is a model-based procedure that identifies categorical latent variables from observed variables and creates probabilities for subgroup membership based on a series of continuous item scores (i.e., in this study, older and younger siblings’ intimacy, negativity, and control). The categories of the latent profile variables consist of individuals who are similar to each other and different from individuals in other profile classes on the patterns across the continuous item scores. First, four unconditional latent profile models were estimated, including the sibling relationship quality indicators. To determine the number of profiles, we used a combination of fit criteria (Collins & Lanza, 2010): (a) Bayesian Information Criteria (i.e., a decrease indicates improved model fit); (b) Lo-Mendell-Rubin Adjusted Likelihood Ratio Test (i.e., a significant test indicates that the given number of profiles fit the data significantly better than a simpler model with one fewer profile); (c) the substantive interpretation of class solutions; (d) size of profiles (i.e., profiles with small ns may not provide quality information); and (e) the conditional response means (i.e., the profile-specific means of the sibling relationship quality indicators) were compared with the overall sample means to determine whether each profile offered a unique pattern that was substantively different from other profiles. Results revealed that the unconditional three-profile solution (i.e., the model without covariates) was the most parsimonious and optimal solution (based on all the previously discussed criteria; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Model Fit Indices for the Unconditional Latent Profile Analyses

| Profile1 | BIC | ABIC | LMR | Adjusted LMR |

BLRT | Average

assignment probabilities |

n for

each class solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3,525.86 | 3,487.82 | — | — | — | — | 246 |

| 2 | 3,445.66 | 3,385.43 | 118.73* | 115.73* | 118.73* | .94,.86 | 178,68 |

| 3 | 3,445.58 | 3,363.17 | 38.62 | 37.64 | 38.62* | .89,.81,.88 | 30,56,160 |

| 4 | 3,450.11 | 3,345.50 | 34.01 | 33.15 | 34.01* | .93,.81,.83,.81 | 28,95,62,61 |

Note. N = 246. BIC = Bayesian information criterion; ABIC = sample size-adjusted Bayesian information criterion; LMR = Lo-Mendell-Rubin; BLRT = bootstrap likelihood ratio test. Bolded text indicates the optimal solution. Dashes indicate that fit indices were not applicable.

p < .05.

The profile classifications presented are based on the unconditional models which are prior to the inclusion of covariates.

Second, as suggested by Collins and Lanza (2010), the three-profile solution was refit to include covariates (i.e., family income, older and younger siblings’ familism values, mothers’ nativity) to account for within-group heterogeneity across profiles. The indices for this conditional three-profile solution (i.e., model with covariates) indicated good fit (i.e., BIC = 3,444.95; ABIC = 3,337.17; LMR = 70.76, p < .01; Adjusted LMR = 69.91, p < .01; BLRT = 70.76, p < .001; Average assignment probabilities = .92, .89, .92). Comparisons of the pattern of means for the unconditional vs. conditional three-profile solution revealed consistency across the solutions, with only slight variation in actual means and profile sizes due to the inclusion of covariates, which suggests a close replication from the unconditional to the conditional model.

LPA also assigns each sibling dyad a probability of membership in each profile. Ideally, each sibling dyad has a high probability of being in one profile and a low probability of being in the other profiles. In this analysis, the average assignment probabilities for the most likely latent profile memberships were high for the three-profile solution with covariates, indicating that each sibling dyad in our sample fit clearly within one of the three profiles. Because the average probabilities were high and the model had an entropy score of .80, it was appropriate to use a classify-analyze approach (Clark & Muthén, 2010). Specifically, we used the resulting LPA probabilities to assign sibling dyads to their highest probability profile and estimated the remaining analyses using an ANCOVA framework. The ANCOVA approach allowed us to maintain the sibling dyad as the unit of analysis and test for both between- and within-family differences in adjustment over time.

To aid in the description of the profiles, we conducted a series of 3 (Profile Membership) × 2 (Birth Order: Older vs. Younger) mixed model ANOVAs with profile as the between-group factor and sibling as the within-group factor. Dependent variables were older and younger siblings’ ratings of sibling intimacy, negativity, and control. These analyses revealed significant profile effects for sibling intimacy, F (2, 243) = 204.73, p < .001, and negativity, F (2, 243) = 72.39, p < .001. For sibling control, there was not a significant Profile effect, but there was a significant Profile × Birth Order interaction, F (2, 243) = 5.73, p < .01. To follow up on Profile effects, we created the mean of older and younger siblings’ relationship qualities and conducted Tukey follow-up tests. For significant Profile × Birth Order interactions, we created sibling difference scores (older sibling minus younger sibling) for Tukey tests (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Means (and Standard Deviations) of Sibling Relationship Quality by Latent Profile

| Positive (n = 32) |

Negative (n = 33) |

Affect-Intense (n = 181) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Sibling Relationship Qualities | ||||||

| Sibling Intimacy | ||||||

| Older Sibling | 4.33 | 0.42 | 2.19 | 0.38 | 3.31 | 0.60 |

| Younger Sibling | 4.25 | 0.45 | 2.42 | 0.54 | 3.38 | 0.58 |

| Sibling average1 | 4.29a | 0.34 | 2.31b | 0.27 | 3.35c | 0.42 |

| Sibling difference | 0.08 | 0.54 | −0.23 | 0.77 | −0.06 | 0.83 |

| Sibling Negativity | ||||||

| Older Sibling | 2.4 5 | 0 .95 | 4.22 | 0.66 | 3 .08 | 0.8 2 |

| Younger Sibling | 2.31 | 0.78 | 4.02 | 0.77 | 3.06 | 0.79 |

| Sibling average2 | 2.38a | 0.72 | 4.12b | 0.45 | 3.07c | 0.59 |

| Sibling difference | 0.14 | 0.96 | 0.21 | 1.11 | 0.02 | 1.08 |

| Sibling Control3 | ||||||

| Older Sibling | 2.1 0 | 0 .71 | 1.91 | 0.57 | 1 .99 | 0.6 6 |

| Younger Sibling | 2.10 | 0.71 | 2.72 | 0.79 | 2.41 | 0.71 |

| Sibling average | 2.10 | 0.49 | 2.31 | 0.51 | 2.20 | 0.49 |

| Sibling difference4 | 0.00a | 1.02 | −0.81b | 0.92 | −0.42ab | 0.96 |

Note: N = 246. The range for all variables is 1–5. Averages and difference scores with different superscripts (a, b, c) within the same row are significantly different.

95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference between the Positive and Affect-Intense profiles was [0.76,1.12], for the Positive and Negative profiles was [1.75,2.21], and for the Negative and Affect-Intense profiles was [0.86–1.21].

95% CI for the difference between the Positive and Affect-Intense profiles was [0.43,0.96], for the Positive and Negative profiles was [1.40,2.09], and for the Negative and Affect-Intense profiles was [0.78–1.31].

Higher scores indicate greater control by the other sibling.

95% CI for the difference between the Positive and Affect-Intense profiles was [0.24,1.37].

The first profile was labeled Positive (15% of sample; n = 32) and included sibling pairs who reported the highest average levels of intimacy and lowest average negativity and the most similar levels of sibling control relative to the other two groups. The second profile was labeled Negative (15% of sample; n = 33) because siblings reported the highest negativity, lowest intimacy, and the largest sibling discrepancies (i.e., older sibling minus younger sibling) in sibling control. The third profile, Affect-Intense (70%; n = 181), included sibling relationships characterized by moderate intimacy and negativity, and moderate discrepancies in sibling control (see Table 3).

We also tested for profile differences in family and sibling characteristics. Chi-squared analyses revealed that there were no significant differences in expected and actual profile membership based on sibling dyad sex constellation. ANOVAs revealed no significant profile differences in age gap between siblings, number of children in the household, or parents’ years living in the U.S.

For Goal 2, we conducted a series of 3 (Profile Membership) × 2 (Sibling Dyad Sex Constellation: Same-sex vs. Opposite-sex dyads) × 2 (Birth Order: Older vs. Younger Sibling) × 2 (Time 2 vs. 3) hierarchical mixed model ANCOVAs using PROC MIXED (SAS 9.2) with maximum likelihood estimation, accounting for Time 1 familism values/adjustment, family income, and parents’ average acceptance. Dependent variables were youths’ familism values, depressive symptoms, risky behaviors, and sexual risk behaviors at T2 and T3. We focused on direct effects and interactions that included profile given our study goals.

For youths’ familism values, no significant profile effects or interactions emerged, but T1 familism values was a significant positive covariate, F (1, 369) = 23.10, p < .01. Post-hoc tests revealed that the Positive profile (M = 4.58) reported higher familism than the Affect-Intense and Negative profiles (M = 4.23, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] = 0.16,0.52; M = 3.98, CI = 0.36,0.82, respectively). Further, the Affect-Intense and Negative profiles were also significantly different, with the Affect-Intense profile reporting higher familism compared to the Negative profile (CI = 0.80,0.43).

Turning to depressive symptoms, T1 depressive symptoms were a significant positive covariate, F (1, 419) = 33.02, p < .001, and there was a significant Profile × Birth Order interaction, F (2, 419) = 3.02, p < .05, such that profile differences in depressive symptoms emerged for older, but not younger, siblings. Follow-up tests showed that older siblings in the Negative profile reported higher depressive symptoms (averaged across T2 and T3, controlling for T1) than older siblings in the Positive and Affect-Intense profiles, F (2, 124) = 4.83, p < .01 (see Table 4). Younger siblings reported similar levels of depressive symptoms across the three profiles.

Table 4.

Means (and Confidence Intervals) for Familism Values and Adjustment by Latent Profile

| Positive (n = 32) |

Negative (n = 33) |

Affect-Intense (n = 181) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 95% CI | M | 95% CI | M | 95% CI | |

| Positive v. | Negative v. | Affect-Intense v. | ||||

| Familism values1 | 4.32 | Negative | 4.23 | Affect-Intense | 4.21 | Positive |

| −0.11,0.27 | −0.17,0.11 | −0.25,0.03 | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms2 | ||||||

| Positive v. | Negative v. | Affect-Intense v. | ||||

| Older Sibling | 12.36a | Negative | 17.50b | Affect-Intense | 11.97a | Positive |

| −9.81,−0.47 | −9.06,−2.01 | −3.84,3.05 | ||||

| Positive v. | Negative v. | Affect-Intense v. | ||||

| Younger Sibling | 13.17 | Negative | 15.03 | Affect-Intense | 13.01 | Positive |

| −6.22,2.51 | −5.47,1.43 | −3.43,3.11 | ||||

| Risky Behaviors2 | ||||||

| Opposite-sex dyads | Positive: | Negative: | Affect-Intense: | |||

| Older Sibling | 1.27c | Older v. Younger | 1.59c | Older v. Younger | 1.45 | Older v. Younger |

| Younger Sibling | 1.50d | −0.36,−0.11 | 2.05d | −0.77,−0.16 | 1.48 | −0.13,0.06 |

| Same-sex dyads | Positive: | Negative: | Affect-Intense: | |||

| older Sibling | 1.35 | Older v. Younger | 1.42 | Older v. Younger | 1.40 | Older v. Younger |

| Younger Sibling | 1.35 | −0.16,0.15 | 1.60 | −0.53,0.17 | 1.49 | −0.16,−0.02 |

| Sexual Risk Behaviors2 | ||||||

| Time 2 | Positi ve: | Negative: | Affect-In tense: | |||

| Older Sibling | −0.19 | Older v. Younger | −0.05c | Older v. Younger | −0.09 | Older v. Younger |

| Younger Sibling | −0.24 | −0.25,0.33 | 0.56d | −1.12,−0.11 | 0.09 | −0.37,0.00 |

| Time 3 | Positive: | Negative: | Affect-Intense: | |||

| Older Sibling | −0.15 | Older v. Younger | 0.37 | Older v. Younger | −0.13 | Older v. Younger |

| Younger Sibling | −0.27 | −0.30,0.54 | −0.02 | −0.27,1.05 | 0.13 | −0.46,−0.06 |

Note: a, b: Different superscripts within the same row are significantly different. c, d: Different superscripts within the column are significantly different. N = 246. CI = confidence interval.

Older and younger siblings’ average familism scores of T2 and T3, controlling for T1familism.

Older and younger siblings’ adjustment scores for T2 and T3, controlling for T1 adjustment.

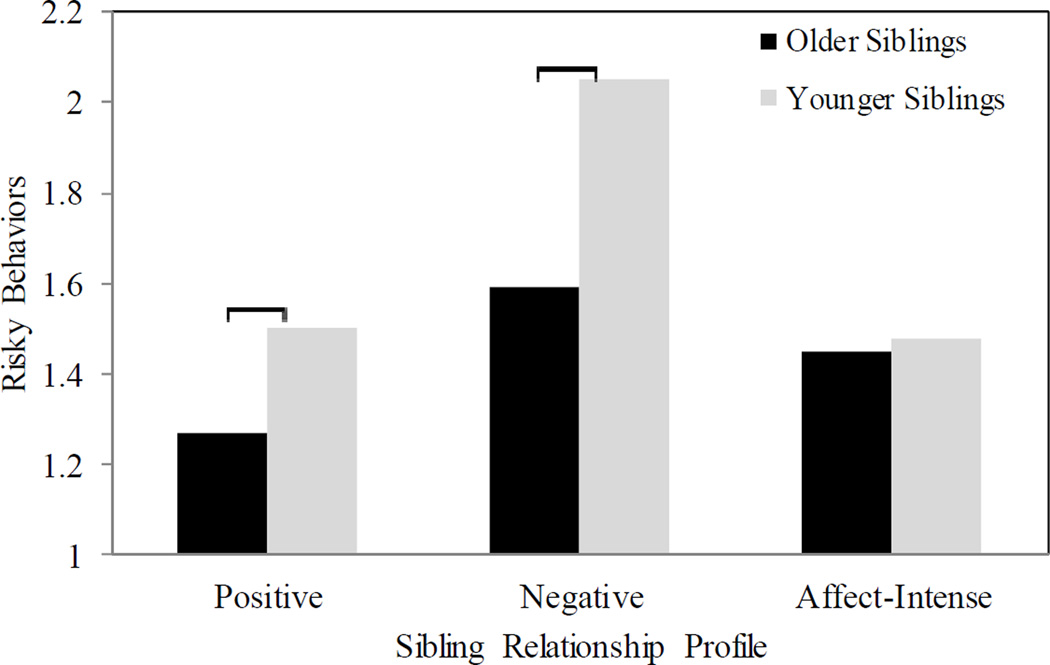

For risky behaviors, parents’ acceptance, F (1, 367) = 8.89, p < .01, and T1 risky behaviors were significant covariates, F (1, 367) = 38.48, p < .001; the association was negative for parents’ acceptance and positive for risky behaviors at T1. In addition, there was a significant Profile × Birth Order × Sibling Dyad Sex Constellation interaction, F (2, 367) = 5.09, p < .01. To follow up, we conducted 3 (Profile) × 2 (Birth Order) ANCOVAs separately for opposite-sex and same-sex dyads with older and younger siblings’ risky behaviors (the average of T2 and T3 for each sibling) as the dependent variable (T1 risky behavior and parental acceptance were covariates). There was a significant Profile × Birth Order interaction for the opposite-sex dyads, F (2, 166) = 6.04, p < .01, such that in Positive and Negative profiles, younger siblings reported significantly higher levels of risky behaviors than their older opposite-sex siblings (see Table 4 and Figure 1). No significant profile differences emerged for same-sex dyads.

Figure 1.

Interaction between sibling relationship profile × birth order predicting risky behaviors for opposite-sex sibling dyads.

Note: Brackets with asterisks indicate significant differences within the profile for older versus younger siblings at p < .05.

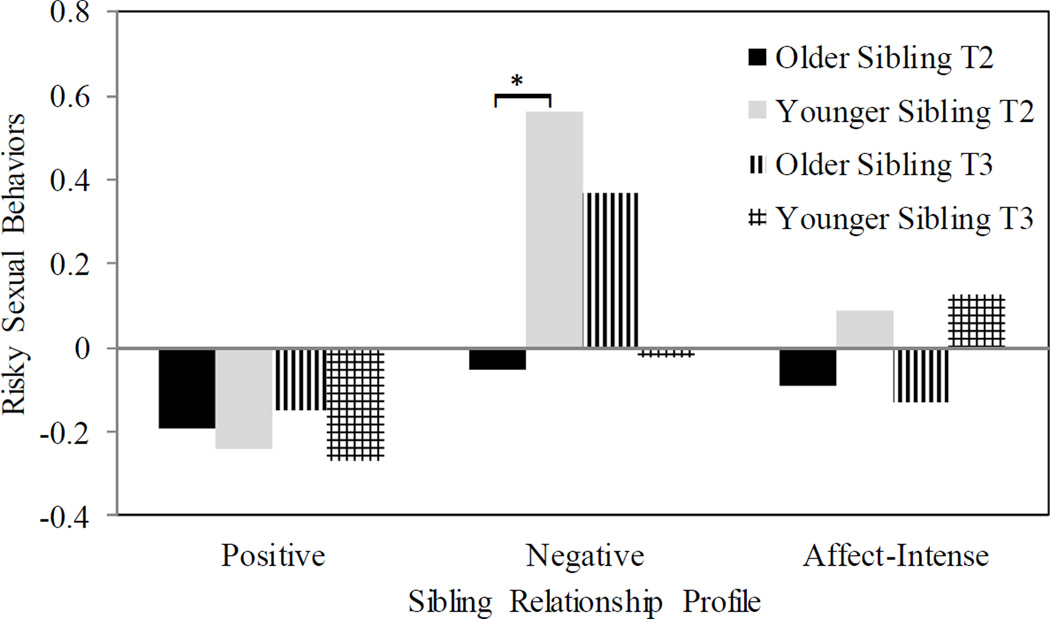

For sexual risk behaviors, family income, F (1, 366) = 5.07, p < .05, and T1 sexual intentions were significant positive covariates, F (1, 366) = 52.25, p < .001, and there were two significant effects. First, there was a significant Profile × Birth Order × Time interaction, F (2, 366) = 4.51, p < .01. To follow up, we conducted 2 (Birth Order) × 2 (Time 2 versus Time 3) ANCOVAs separately by profile with older and younger siblings’ sexual risk behaviors at Time 2 and 3 (as the repeated factor), controlling for T1 sexual intentions. There was a significant Birth Order × Time interaction for the Negative profile, F (1, 42) = 7.43, p < .01, but not for the Positive or Affect-Intense profiles. For the Negative profile, younger siblings reported higher levels of sexual risk behaviors than older siblings at T2, but there were no significant differences between older and younger siblings’ sexual risk behaviors at T3 (see Table 4 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interaction between sibling relationship profile × birth order × time predicting risky sexual behaviors (standardized score).

Note: The bracket with the asterisk indicates that the two bars are significantly different at p < .05.

Further, results for sexual risk behaviors also revealed a significant Profile × Sibling Dyad Sex Constellation interaction, F (2, 366) = 3.35, p < .05. Follow ups revealed significant profile differences for opposite-sex dyads, such that the Negative profile reported higher levels of sexual risk (M = 0.53) compared to the Positive and Affect-Intense profiles (M = −0.14, CI = −1.14,-0.19; M = 0.02, CI = −0.86,-0.157, respectively). In same-sex dyads, there were no significant profile differences.

Discussion

We extended research on patterns of sibling relationship qualities (McGuire et al., 1996; McHale et al., 2007) to U.S. Mexican-origin families. U.S. Latinos are the largest and fastest-growing ethnic minority group, and the largest proportion of this group is of Mexican origin (65%; U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). Yet, we know little about normative sibling dynamics and their implications for youth adjustment within this population (Updegraff et al., 2010). We found three profiles of sibling relationships and documented links between these profiles in early/middle adolescence and siblings’ adjustment in adolescence/young adulthood, accounting for prior adjustment and parent-adolescent acceptance. By maintaining the dyad as the unit of analysis, we found differential links between profiles and older versus younger siblings’ adjustment in late adolescence/young adulthood. These findings underscore that the associations between sibling profiles in early/middle adolescence and subsequent adjustment varied by birth order, sibling gender constellation, and adjustment outcome.

Sibling Relationship Profiles

Sibling relationships were characterized by one of three profiles and these groups were not differentiated by sibling or cultural background characteristics examined here. The largest subgroup of sibling dyads was characterized as Affect-Intense (70%). In this profile, siblings described moderate levels of intimacy and negativity. Further, younger siblings perceived significantly more control by their older siblings than vice versa. As this profile represents the typical emotional intensity of sibling relationships reflected in the combination of positive and negative affect and normative patterns of sibling control/dominance (Dunn, 1993), it follows that the majority of siblings would be in this profile. Positive sibling relationships (15%) were characterized by the highest average levels of sibling intimacy and the lowest average levels of sibling negativity, compared to the other groups. In this profile, older and younger siblings reported the most similar levels of control, suggesting a shared perspective on this dimension. Lastly, 15% of siblings were classified in the Negative profile. Siblings described significantly higher negativity and lower intimacy compared to the other profiles. Similar to the Affect-Intense profile, younger siblings reported higher levels of control by their older siblings than vice versa.

Although one may expect more siblings to be in the Positive profile given the importance placed on family relationships in Mexican culture (Cauce & Domenech-Rodríguez, 2002), studies with European American families show that in early/middle adolescence sibling conflict peaks and then declines in late adolescence while sibling intimacy remains stable or increases throughout adolescence (Kim, McHale, Osgood, & Crouter, 2006). Given the large percentage of siblings in our Affect-Intense profile, this may reflect a degree of normative sibling conflict and intimacy in adolescence that may be similar across cultures. Importantly, there were few siblings in the Negative profile, indicating that relationships characterized by high negativity in the absence of support/emotional closeness are uncommon in this sample. Overall, findings show that we were able to identify sibling relationships that were characterized by distinct combinations of positive and negative relationship qualities, with some relationships being characterized by similar levels of intimacy and negativity and others being characterized by higher intimacy than negativity, or higher negativity than intimacy.

Together, these findings offer several insights about sibling relationships in this cultural context. First, profile differences emerged in familism values, but not in cultural background characteristics in early/middle adolescence, with siblings in Positive relationships reporting the strongest endorsement of familism values in early/middle adolescence followed by siblings in the Affect-Intense and Negative profiles. These findings highlight the importance of moving beyond cultural characteristics (e.g., years in the U.S., nativity) to examine the role of cultural values in family dynamics. Further, once we accounted for T1 differences in familism values, there were no profile differences in subsequent familism values. These findings underscore the importance of looking further into when and how cultural values play a role in family dynamics.

Second, the Positive and Negative sibling profiles are consistent with prior research (McGuire et al., 1996; McHale et al., 2007), and an Affect-Intense group has been documented among European American siblings (McGuire et al., 1996). The absence of an uninvolved profile among these U.S. Mexican-origin siblings is potentially important. Possibly, such a group is too small to detect in this cultural context because siblings play an important role in Mexican-origin adolescents’ lives (Updegraff et al., 2005) and they are socialized to value their family relationships (Knight et al., 2010), making it unlikely that they would have low levels of all assessed sibling relationship qualities. Third, although only 15% of siblings were classified as Positive, 87% of Mexican-origin siblings were classified into a profile that reported moderate/high levels of intimacy compared to less than half of African Americans (41%; McHale et al., 2007) and European Americans (45%; McGuire et al., 1996), underscoring the presence of close sibling relationships in this cultural context.

Sibling Relationship Profiles and Adolescent/Young Adult Adjustment

Our findings supported a risk and resilience perspective (Rutter, 1987) and revealed associations between sibling profiles in early/middle adolescence and adjustment in adolescence/young adulthood. Further, sibling characteristics played an important role in the associations between sibling relationship profiles and adjustment. Our findings revealed that being in the Positive profile and experiencing emotionally close sibling relationships with low levels of negativity was a promotive factor because these adolescents/young adults displayed lower levels of adjustment problems. Alternatively, being in the Negative profile and having relationships characterized by negativity and control and low levels of support was a risk factor because adolescents/young adults displayed higher levels of adjustment problems. Different patterns emerged for older versus younger siblings, highlighting the importance of examining links between sibling profiles and both younger and older siblings’ subsequent adjustment. As these findings controlled for prior adjustment (and parental acceptance), they represent a strong test of the links between sibling relationship quality and later adjustment.

Beginning with depressive symptoms, sibling relationships characterized by moderate to high levels of emotional support either with or without sibling negativity (i.e., Affect-Intense and Positive profiles, respectively) were associated with fewer depressive symptoms for older siblings—showing the benefits of emotional closeness for depressive symptoms in young adulthood. Siblings in emotionally close relationships with low/moderate levels of negativity may be more comfortable confiding in and supporting one another, resulting in fewer depressive symptoms, compared to siblings with negative relationships (Howe, Aquan-Assee, Bukowski, & Rinaldi, 2001). Sibling support may be salient for older siblings because of changes in educational and family experiences that occur as they transition to adulthood.

Negativity in interpersonal relationships is linked to adjustment problems, particularly to involvement in risky behaviors (Solmeyer et al., 2014), through learning negative interaction styles with siblings (Patterson et al., 1990); whereas, positive relationships may protect youth from involvement in risky behaviors by increasing youths’ self-esteem (Rutter, 1987). In the face of siblings’ overall low levels of risky behavior involvement, we found that younger siblings in the Positive and Negative profiles reported greater involvement in risky behaviors than their older opposite-sex siblings. Risky behavior involvement typically increases throughout adolescence and declines in young adulthood (Farrington, 2009). This developmental trend of engaging in more risky behaviors in adolescence (younger siblings) than in young adulthood (older siblings) was only evident in opposite-sex dyads characterized by a Negative or Positive relationship profile. In the Negative profile, it may be the combination of high negativity and control in the absence of warmth with an older sibling of the opposite-sex (who younger siblings may be less likely to model) that results in younger siblings’ relatively higher engagement in risky behaviors.

Sibling differences in risky behavior involvement in the Positive profile may come about for different reasons, as older siblings in this group engaged in the lowest levels of risky behaviors. Possibly, having a positive relationship with an opposite-sex younger sibling is protective for older siblings. Individuals who have close relationships with siblings have greater peer competence (Kim et al., 2007) and those with opposite-sex siblings may exhibit a broader range of relationship skills, leading to a greater ability to avoid relationships with deviant peers and resisting pressure to engage in risky behaviors. For younger siblings in the Positive profile who reported higher levels of involvement in risky behavior than their older siblings, this involvement may reflect the normative developmental progression (Farrington, 2009).

For sexual risk behaviors, in the Negative profile, in late adolescence, younger siblings engaged in higher levels of sexual risk behaviors compared to their young adult older siblings. Once younger siblings reached young adulthood, however, their involvement in sexual risk behaviors were similar to their older siblings’. Patterns of high levels of sexual risk behavior involvement in late adolescence are in line with previous work showing that sexual risk behaviors increase in adolescence and level off or decline during young adulthood (Fergus, Zimmerman, & Caldwell, 2007). High levels of negativity with siblings may exacerbate younger siblings’ involvement in sexual risk behaviors in late adolescence. Older siblings are important socialization agents and sources of support (East, 2009) and are likely more experienced in the sexual domain, making them knowledgeable sources of sexual health information. Without a supportive relationship, younger siblings may not feel comfortable seeking advice from their older siblings in the areas of sexuality, leading to sexual risk behavior engagement. Within the Negative profile, siblings in opposite-sex dyads reported greater sexual risk behaviors than siblings in same-sex dyads. Youth with opposite-sex siblings are exposed earlier to potential sexual partners (i.e., siblings’ friends) in adolescence giving them more opportunities to engage in early sexual behaviors, which may result in greater involvement in sexual risk behaviors (East, 2009). Overall, siblings experiencing high levels of negativity and control and low levels of intimacy are vulnerable to engaging in sexual risk behaviors, particularly younger siblings in late adolescence and siblings in opposite-sex dyads.

Limitations, Future Directions, and Implications

The limitations of our study offer directions for future research. First, we assessed sibling relationship quality in early adolescence (for younger siblings) and middle adolescence (for older siblings) and its association with later adjustment. Because changes in sibling relationship quality may be associated with changes in individuals’ adjustment, future work should investigate fluctuations in linkages between sibling profiles and youth adjustment across time. Second, the sample included two-parent families with biological siblings. Examining these associations in diverse family structures is important given potentially different family dynamics. Third, although we found links between sibling relationships and adjustment, we did not assess specific mechanisms by which sibling relationship profiles were associated with siblings’ adjustment. In future work, it will be important to identify mechanisms leading to these associations.

Our findings have implications for promoting healthy development among Mexican-origin adolescents and young adults in the U.S. Strengthening sibling relationships is an important step given that emotionally close sibling relationships in adolescence had advantages for older siblings (e.g., lower levels of depressive symptoms). Additionally, younger siblings in negative relationships are engaging in greater sexual risk behaviors than their older siblings. By promoting positive relationship qualities early in adolescence, younger siblings may be more likely to seek advice from their older siblings on healthy sexual behaviors. Finally, in the Negative profile, opposite-sex sibling dyads experienced greater sexual risk involvement than same-sex dyads. Thus, enhancing sibling relationship quality is beneficial for both siblings’ adjustment and our findings highlight the need for consideration of sibling characteristics in program development.

Mexican-origin individuals are part of a young and rapidly growing ethnic minority group in the U.S. (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). Compared to other ethnic groups, adolescents /young adults of Mexican-origin are at greater risk for adjustment problems (e.g., CDC, 2011); therefore, it is important to examine socializing agents, such as siblings, to increase our understanding of how family dynamics are linked to Mexican-origin adolescents’/young adults’ adjustment. Overall, we found that sibling relationships in adolescence serve as both promotive and risk factors and are an important influence in adolescents’/young adults’ lives.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the families and youth who participated in this project, and to the following schools and districts who collaborated: Osborn, Mesa, and Gilbert school districts, Willis Junior High School, Supai and Ingleside Middle Schools, St. Catherine of Sienna, St. Gregory, St. Francis Xavier, St. Mary-Basha, and St. John Bosco. We thank Ann Crouter, Mark Roosa, Nancy Gonzales, Roger Millsap, Jennifer Kennedy, Leticia Gelhard, Melissa Delgado, Emily Cansler, Shawna Thayer, Devon Hageman, Ji-Yeon Kim, Lilly Shanahan, Norma Perez-Brena, Chun Bun Lam, Megan Baril, Anna Soli, and Shawn Whiteman for their assistance in conducting this investigation. Funding was provided by NICHD grant R01HD39666 and the Cowden Fund to the School of Social and Family Dynamics at ASU.

Contributor Information

Sarah E. Killoren, University of Missouri

Sue A. Rodríguez De Jesús, Arizona State University.

Kimberly A. Updegraff, Arizona State University

Lorey A. Wheeler, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

References

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman LR, Magnusson D, El-Khouri BM. Studying individual development in an interindividual context: A person-oriented approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Blyth DA, Foster-Clark FS. Gender differences in perceived intimacy with different members of adolescents’ social networks. Sex Roles. 1987;17:689–718. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodríguez M. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino Children and Families in the United States: Current Research and Future Directions. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2007 (Report No. SS-4) Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2007:57. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/ss/ss5704.pdf. [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adolescent pregnancy and childbirth— United States, 1991–2008. Suppl. Vol. 60. Atlanta, GA: Author; 2011. pp. 105–118. MMWR 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Clark SL, Muthén B. Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. 2010 Available at http://statmodel2.com/download/relatinglca.pdf.

- Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social behavioral, and health sciences. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J. Young children’s close relationships: Beyond attachment. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- East PL. Racial and ethnic differences in girls’ sexual, marital, and birth expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:150–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East PL. Adolescents’ relationships with siblings. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. pp. 43–73. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Barber B. Unpublished scale. University of Michigan; 1990. Risky behavior measure. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP. Conduct disorder, aggression, and delinquency. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology: individual bases of adolescent development. 3rd. Vol. 1. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. pp. 683–722. [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, Zimmerman MA, Caldwell CH. Growth trajectories of sexual risk behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1096–1101. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70:1030–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Gore S, Aseltine RH. Race and ethnic differences in depressed mood following the transition from high school. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:370–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel E, Hussey J, Tabor J, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- Howe N, Aquan-Assee J, Bukowski WM, Lehoux PM, Rinaldi CM. Siblings as confidants: Emotional understanding, relationship warmth, and self-disclosure. Social Development. 2001;10:439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, McHale SM, Crouter AC, Osgood DW. Longitudinal linkages between sibling relationships and adjustment from middle childhood through adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:960–973. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, McHale SM, Osgood DW, Crouter AC. Longitudinal course and family correlates of sibling relationships from childhood through adolescence. Child Development. 2006;77:1746–1761. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, Germán M, Deardorff J, Roosa MW, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American cultural values scale for adolescents and adults. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire S, McHale SM, Updegraff KA. Children’s perceptions of the sibling relationship in middle childhood: Connections within and between family relationships. Personal Relationships. 1996;3:229–239. [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Whiteman SD, Kim J, Crouter AC. Characteristics and correlates of sibling relationships in two-parent African American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:227–235. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Flores E, Tschann JM, Pasch LA. Parenting style, depressive symptoms, and substance use in Mexican American adolescents. Youth & Society. 2011;45:365–388. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeBaryshe B, Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist. 1990;44:329–335. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Characteristics of the Population in Arizona, by race, ethnicity, and nativity: 2011. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/states/pdf/AZ_11.pdf.

- Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;7:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:316–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ. Ecological perspectives on developmental risk. In: Osofsky JD, Fitzgerald He, editors. WAIMH handbook of infant mental health. Vol. 4. New York: Wiley; 1999. pp. 223–248. Infant mental health groups at risk. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JC, Barton-Henry ML, Pruzinsky T. Assessing child-rearing behaviors: A comparison of ratings made by mother, father, child, and sibling on the CRPBI. Child Development. 1985;56:462–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solmeyer AR, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Longitudinal associations between sibling relationship qualities and risky behavior across adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:600–610. doi: 10.1037/a0033207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stets JE. Job autonomy and control over one’s spouse: A compensatory process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:244–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Killoren SE, Rodriguez SA. Cultural variations in sibling relationships. In: Caspi J, editor. Siblings Development: Implications for Mental Health Practitioners. New York, NY: Springer Publishing; 2010. pp. 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Whiteman SD, Thayer SM, Delgado MY. Adolescent sibling relationships in Mexican American families: Exploring the role of familism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:512–522. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census Bureau. The Hispanic population in the United States: 2000 (PC Publication No. P25-535) Washington, DC: U. S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Hispanic Heritage Month 2014. U. S. Census Bureau News; 2014. Sep, Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2014/cb14-ff22.html#. [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Shirtcliff EA, Marceau K. Disorders of childhood and adolescence: Gender and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:275–303. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]