Abstract

Animals often experience periods of nutrient deprivation; however, the molecular mechanisms by which animals survive starvation remain largely unknown. In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, the nuclear receptor DAF-12 acts as a dietary and environmental sensor to orchestrate diverse aspects of development, metabolism, and reproduction. Recently, we have reported that DAF-12 together with co-repressor DIN-1S is required for starvation tolerance by promoting fat mobilization. In this report, we found that genetic inactivation of the DAF-12 signaling promoted the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) during starvation. ROS mediated systemic necrosis, thereby inducing organismal death. The DAF-12/DIN-1S complex up-regulated the expression of antioxidant genes during starvation. The antioxidant enzyme GST-4 in turn suppressed ROS formation, thereby conferring worm survival. Our findings highlight the importance of antioxidant response in starvation tolerance and provide a novel insight into multiple organisms survive and adapt to periods of nutrient deprivation.

All animals have evolved abilities to improve the chances of survival and reproduction. Among these stress, starvation is one of common stressful situations in nature. To cope with nutrient deprivation, the free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans can make physiological changes to developmentally arrest at multiple stages, such as L1 diapause1, dauer diapause2, and adult reproductive diapause3. Besides reproductive arrest, L4 or young adult worms survive starvation by promoting fat mobilization, which is mediated by a variety of lipases4,5. For example, starvation induces the expression of lipase gens fil-1 and fil-2 that involved in converting fat storage into energy, and thus maintain whole-body energy homeostasis4. Meanwhile, upon fasting, the expression of the lysosomal lipase genes, such as lipl-1 and lipl-3, is up-regulated by a transcription factor HLH-305. These lysosomal lipases induce lipid hydrolysis through lipophagy.

In C. elegans, the nuclear receptor DAF-12 orchestrates a switch from arrest to developmental progression in response to environmental and dietary cues, and has been implicated as a signal connecting nutrition, development, and longevity6,7. By binding with its steroidal ligands, dafachronic acids (DAs), DAF-12 induces reproductive development under favorable conditions such as an abundant food supply, whereas DAF-12 together with co-repressor DIN-1S promotes dauer diapause under harsh environmental conditions such as limited food and overcrowding6,7. Our recent study has revealed that upon fasting, DAF-12/DIN-1S induces the expression of tbh-1 that encodes tyramine β-hydroxylase, a key enzyme for octopamine biosynthesis in C. elegans. Octopamine up-regulates the expression of the lipase gene lips-6 in the intestine8. LIPS-6, in turn, promotes lipid mobilization to confer starvation resistance.

We noted that the survival rates of daf-12 and din-1 mutants were significantly lower than that of tbh-1 mutants. It is possible that in addition to the octopamine pathway, there is another pathway through which DAF-12/DIN-1S acts to regulate starvation resistance. A previous microarray analysis has revealed that expression of antioxidant and detoxification genes is up-regulated during starvation in C. elegans4. The fact that DAF-12/DIN-1S mediates resistance to heat and oxidative stress9 raises a possibility that the complex probably regulates an antioxidant response during starvation. In this study, we demonstrated that loss of function mutations in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) resulted in an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, which was involved in worm death, after starvation.

Results

DAF-12/DIN-1S is dominant during starvation

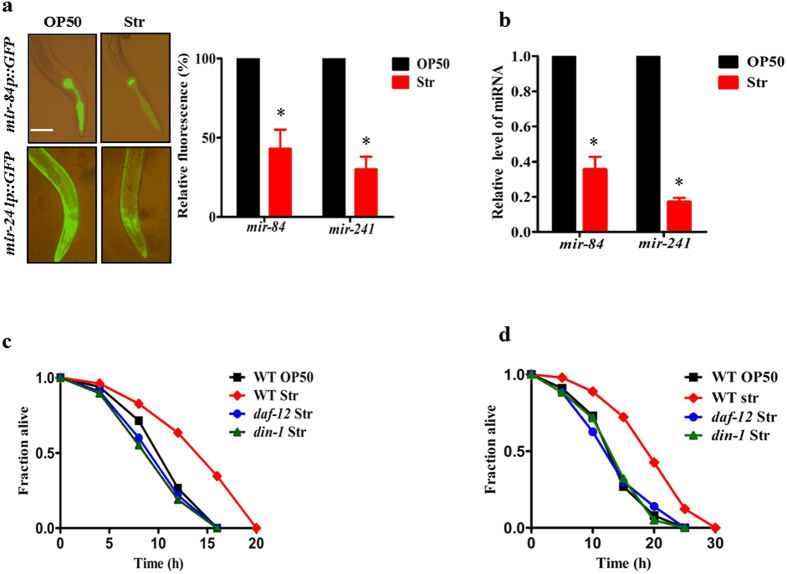

It is believed that DAF-12 is mostly unliganded under starvation conditions, whereas production of DAs by DAF-9 converts DAF-12 to a liganded state when food is available6,10. To confirm this point, we first monitored the transcriptional activity of liganded DAF-12 using transgenic worms containing mir-84p::GFP and mir-241p::GFP. Both the microRNAs are the targets of liganded DAF-12, and their expressions were downregulated by mutations in daf-12 and daf-911. As expected, the expression of mir-84p::GFP and mir-241p::GFP was significantly lower in worms after 12 h starvation than in worms fed with the standard laboratory food E. coli OP50 (Fig. 1a). Similar results were obtained by determining the expression of mir-84 and mir-241 by qPCR (Fig. 1b). DA-deficient animals (eg. daf-9 mutant worms) are more stress resistant in a manner dependent on unliganded DAF-12 (the DAF-12/DIN-1S complex)9. Consistent with the idea, we found that starved worms exhibited more resistance to a pro-oxidant menadione (10 mM), or high temperature (35 °C), than well-fed worms (Fig. 1c and d). Mutations in daf-12(rh611rh411) or din-1(dh127) abolished the stress resistance-phenotype of starved worms. These results further confirm this notion that the DAF-12/DIN-1S complex is dominant during nutrient deprivation.

Figure 1. Unliganded DAF-12 is dominant in starved worms.

(a) The expression of mir-84p::GFP and mir-241p::GFP in animals was reduced after 12 h of starvation. Quantification of fluorescence intensity is shown in right panel. *P < 0.05 relative to well-fed worms (OP50). Scale bar, 50 μm. (b) The expression of mir-84 and mir-241 was measured by qPCR. **P < 0.01 relative to well-fed worms. (c) The starved wild type (WT) worms were more resistant to menadione (10 mM) than well-fed WT worms (P < 0.01). (d) The starved WT worms were more resistant to high temperature (35 °C) than well-fed WT worms (P < 0.01). Mutations in daf-12 or din-1 abolished the resistance to oxidative and heat stress in the starved worms. Str, starvation.

Starvation induces systemic necrosis in daf-12(rh61rh411), din-1(dh127), and tbh-1(n3247) mutants

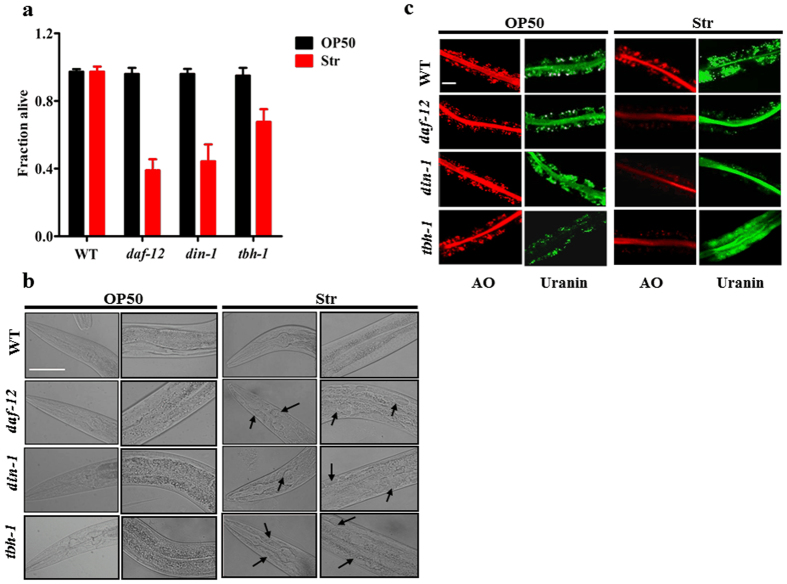

Our recent study has revealed that the DAF-12/DIN-1S complex induces tbh-1 expression in response to starvation in C. elegans. The DAF-12/DIN-1S-TBH-1 -octopamine signaling is required for starvation tolerance. However, more than 60% of daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants were dead (Fig. 2a), whereas only 32% of tbh-1(n3247) worms were dead after 5 days of starvation. These results suggest that in addition to octopamine, other mechanisms exist for DAF-12/DIN-1S to exert its effect on starvation resistance.

Figure 2. Systemic necrosis occurs in daf-12, din-1, and tbh-1 mutants under nutrient-deprivation conditions.

(a) Survival rates of worms after five days of starvation. Results are means ± SD of three experiments.*P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01 versus well-fed worms (OP50). WT, wild type worms. (b and c) Necrosis in worms after two days of starvation. DIC images of worms (b) and fluorescence microscopy of acridine orange (AO)-, and uranine- (lower panels) labeled intestine (c) are shown. Enlarged vacuoles are indicated by black arrows. Scale bar, 50 μm. Str, starvation.

In C. elegans, nutrient deprivation induces apoptosis in germ cells and necrotic cell death in neurons12,13. Thus, organismal death is probably the result of apoptosis or necrosis after prolonged starvation in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants. Using the SYTO 12 dye staining against the apoptotic germ cells14, we found no apparent accumulation of apoptotic germ cells in the daf-12(rh61rh411), din-1(dh127), and WT worms after two days of starvation (Fig. S1a). Meanwhile, knockdown of ced-4, a homolog to mammalian Apaf-1 that is required for apoptosis activation, did not significantly suppress starvation-induced mortality in daf-12(rh61rh411) and din-1(dh127) mutants after five days of starvation (Fig. S1b). Therefore, our results suggest that worm death from nutrient deprivation does not depend on the core apoptotic machinery.

Next, we examined whether necrosis as a post-starvation phenotype leads to worm death. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images showed that daf-12(rh61rh411), din-1(dh127), and tbh-1(n3247) mutants displayed an enlarged vacuolar morphology characteristic of necrotic cells in the head and intestine, whereas WT worms had fewer vacuolated cells after two days of starvation (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, we tested the lysosomal injury using acridine orange, an acidophilic dye that stains lysosomes15. We found that acridine orange-labeled granules were lysed in the intestine in daf-12(rh61rh411), din-1(dh127), and tbh-1(n3247) mutants, but not in WT worms, after two days of starvation (Fig. 2c). Similar results were obtained from staining analysis by the dye uranin, which is an indicator for loss of membrane integrity in lysosome-related organelles16 (Fig. 2c). These results indicate that systemic necrosis occurs during starvation.

Systemic necrosis mediates worm death induced by starvation in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants

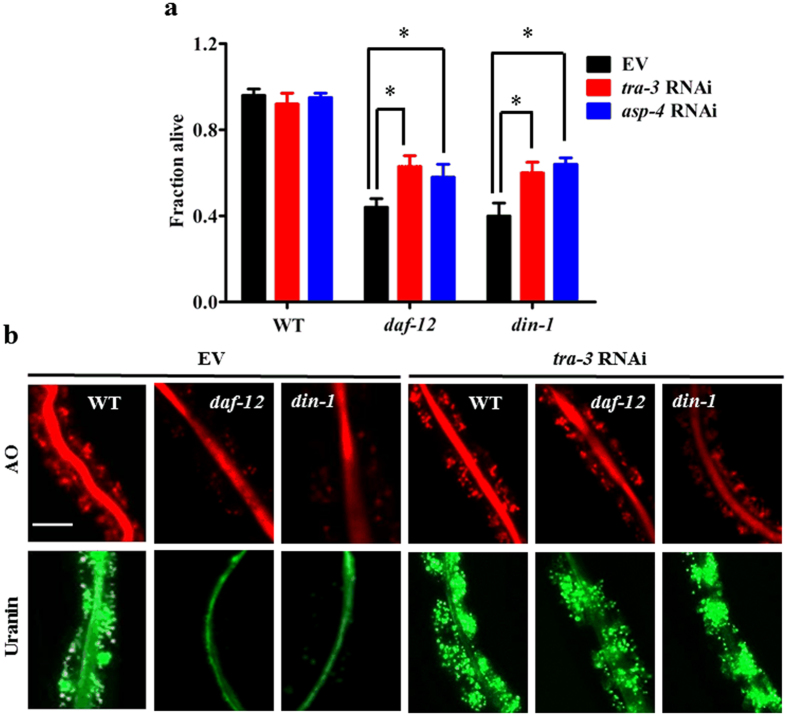

In C. elegans, many genes involved in necrosis have been identified, including calpains and aspartyl proteases17,18. We first examined whether calpain proteases affect starvation-induced organismal death by knockdown of clp-1, clp-2, tra-3/clp-5, clp-6, clp-7. Organismal death was significantly suppressed in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants subjected to RNAi with tra-3/clp-5 (Fig. 3a), but not with clp-1, clp-2, clp-6, and clp-7 (Fig. S2), after five days of starvation. Meanwhile, knockdown of tra-3 by RNAi markedly reduced lysosomal injury in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants upon starvation (Fig. 3b). There are at least six aspartyl proteases (asp-1 to asp-6) in C. elegans. We found that inhibition of asp-4 by RNAi, but not other aspartyl proteases (Fig. S3), also showed protection (Fig. 3a). These results suggest that necrosis is responsible for starvation-induced organismal death.

Figure 3. Worm death is due to systemic necrosis under nutrient-deprivation conditions.

(a) Knockdown of asp-4 and tra-3 by RNAi increased the survival in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants after five days of starvation. *P < 0.05 versus EV. (b) Knockdown of tra-3 partially inhibited necrosis induced by starvation in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants. EV, empty vector. Scale bar, 50 μm.

DAF-12/DIN-1S up-regulates the expression of antioxidant genes, which are required for starvation resistance

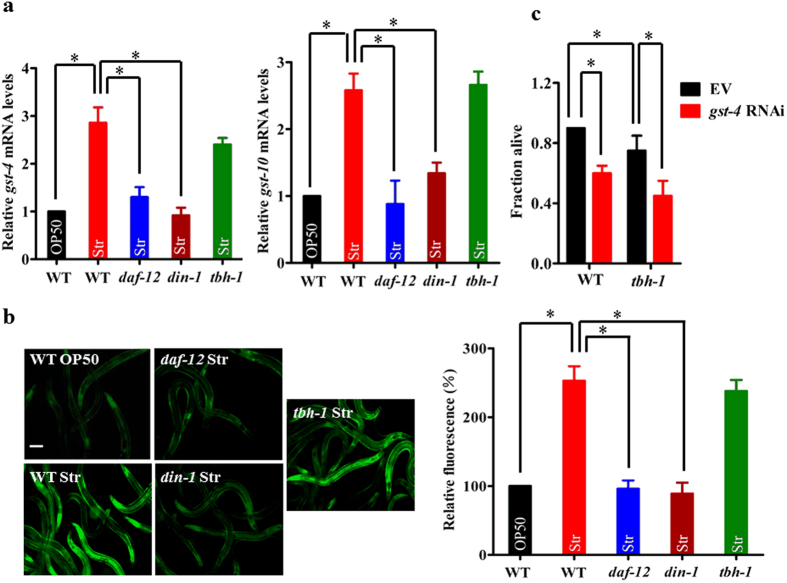

It is well established that the DAF-12/DIN-1S complex mediates resistance to heat and oxidative stress9. A previous microarray analysis has revealed that a set of stress resistance and detoxification related genes, such as glutathione S-transferases (gst-4, gst-10, gst-24, and gst-26), UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (ugt-16, K04A8.10), and cytochrome P450 (cyp-35D1 and cyp-29A3), is up-regulated during starvation4. Among the GSTs, GST-4 and GST-10 play important roles in resistance to oxidative stress in C. elegans19,20. Using qPCR, we found that expression of gst-4 and gst-10 was significantly up-regulated in WT and tbh-1(n3247) worms, but not in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) worms, during one day of starvation (Fig. 4a). Using transgenic worms carrying the Pgst-4::gst-4::GFP, we found that the expression of Pgst-4::gst-4::GFP was significantly induced by starvation in WT and tbh-1(n3247) worms, but not in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) worms (Fig. 4b). Thus, the DAF-12/DIN-1S complex, rather than TBH-1, induces the expression of antioxidant genes during starvation. Interestingly, knockdown of gst-4 by RNAi reduced worm survival in both WT worms and tbh-1(n3247) mutants (Fig. 4c). These results suggest that DAF-12/DIN-1S promotes worm survival during starvation, in part, by up-regulating the expression of antioxidant genes.

Figure 4. DAF-12/DIN-1S regulates antioxidant genes to promote starvation resistance.

(a) The expression of gst-4 (left panel) and gst-10 (right panel) was significantly up-regulated in WT worms after one day of starvation. Mutations in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127), but not tbh-1(n3247), inhibited the expression of gst-4 and gst-10 in starved worms. (b) The expression of Pgst-4::GFP was up-regulated in starved wild type (WT) worms relative to well-fed worms. Mutations in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127), but not tbh-1(n3247), inhibited the expression of Pgst-4::GFP. The right part shows quantification of GFP levels. (c) Knock-down of gst-4 reduced survival rates after five days of starvation. *P < 0.05. Scale bar, 100 μm. Str, starvation.

ROS are involved in worm death in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) worms during starvation

The induction of antioxidant gene expression during starvation raises a possibility that starvation is able to induce the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). To test this idea, we first determined the levels of ROS using 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA), a fluorescent dye that has been used to detect the ROS levels in C. elegans. As shown in Fig. 5a, the basal levels of ROS were very low in WT well-fed worms. However, WT worms subjected to 24 h starvation exhibited similar levels of ROS to WT well-fed worms (Fig. 5a). Interestingly, the levels of ROS were dramatically elevated in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants following starvation. It should be noted that a mutation in daf-12(rh61rh411) and din-1(dh127) itself did not lead to an increase in ROS levels under well-fed conditions. Similar results were obtained using fluorescent dyes, dihydroethidium (DHE) and CellROX® Deep Red (Fig. 5b and c). Likewise, knockdown of gst-4 also promoted ROS formation during 24 h of starvation (Figs S5 and S6). Recently, Mark et al.21 have reported that vitamin D3 promotes the expression of gst-4 in worms, which is dependent on SKN-1 and IRE-1. We found that vitamin D3 significantly up-regulated the expression of gst-4 in both daf-12(rh61rh411) and din-1(dh127) mutants after 12 h of starvation (Fig. S4). Meanwhile, vitamin D3 also blocked the increase in ROS formation in starved daf-12(rh61rh411) and din-1(dh127) mutants (Fig. 5b and c). These data suggest that DAF-12/DIN-1S mediates the induction of gst-4, thereby inhibiting ROS formation.

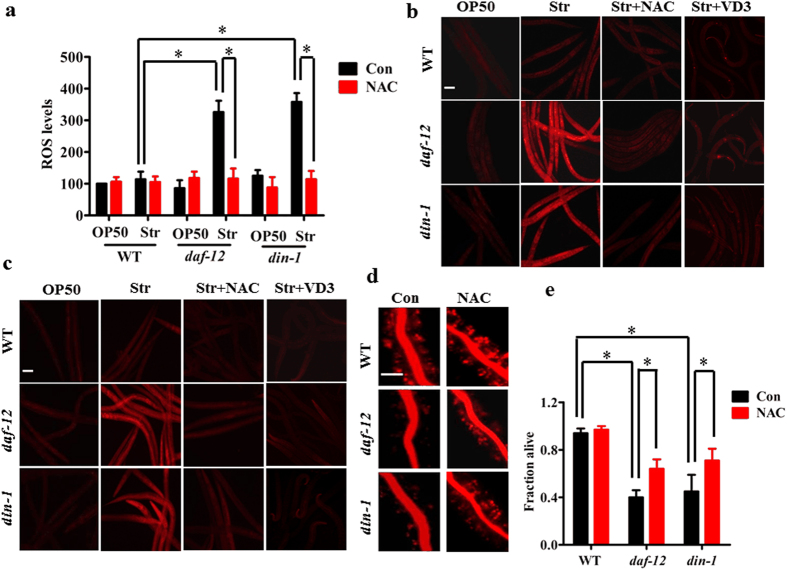

Figure 5. ROS formation is involved in worm death in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) worms after starvation.

(a–c) Mutations in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) resulted in an increase in ROS formation after 24 h of starvation. The levels of ROS were detected by DCF (a), DHE (b), and CellROX® Deep Red (c). The antioxidant NAC (1 mM) and vitamin D3 (0.5 mM) markedly diminished the increased ROS levels in starved daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants. Scale bar, 100 μm. (d) NAC significantly suppressed necrosis in the daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants after starvation. Fluorescence microscopy of acridine orange (AO)-labeled intestine of worms after two days of starvation. Scale bar, 50 μm. (e) NAC markedly promoted the survival of daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants after five days of starvation. Results are means ± SD of three experiments. *P < 0.05. Str, starvation. Con, control.

To test whether induction of ROS formation plays a role in starvation-induced organismal death in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants, worms were treated with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (1 mM), a ROS scavenger22. NAC markedly diminished the increased ROS levels in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants after 24 h starvation (Fig. 5a–c). Importantly, NAC not only significantly suppressed lysosomal injury after two days of starvation (Fig. 5d), but also partially rescued the starvation-induced mortality in daf-12(rh61rh411) and din-1(dh127) mutants (Fig. 5e).

In addition, the other antioxidants, such as glutathione reduced ethyl ester (GSH-MEE), and α-tocopherol, also suppressed the ROS formation in the starved worms subjected to gst-4 RNAi (Figs S5 and S6). Thus, starvation-induced expression of antioxidant genes is required for starvation stress.

Discussion

Our studies uncover a surprising role for the antioxidant response in starvation resistance in C. elegans. After nutrient deprivation, the liganded DAF-12 (DAF-12/DA) shifts the equilibrium to ligand-free DAF-12/DIN-1S complex. DAF-12/DIN-1S in turn boosts the antioxidant response, which maintains redox homeostasis. Downregulation of this pathway exacerbates oxidative stress, thereby mediating nutrient deprivation-induced organismal death.

Up-regulation of antioxidant and detoxification genes is widely observed in a variety of organisms under nutrient deprivation conditions. A microarray analysis reveals that a set of stress resistance and detoxification related genes is up-regulated during starvation in adult worms4. Furthermore, large numbers of antioxidant and detoxification genes encoding glutathione peroxidases, superoxide dismutases, GSTs, and UGTs, are up-regulated in dauer larva of C. elegans, which is a non-feeding alternative larval stage23,24,25. In yeast, methionine starvation induces expression of antioxidant genes such as superoxide dismutases, thioredoxin, peroxiredoxin, glutaredoxin26. In brown trout, the malondialdehyde levels and the activities of several antioxidant enzymes (eg. superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione reductase) increased in liver and gills during long-term starvation27. These results implicate that starvation is a potential factor that elicits oxidative stress. In this study, the observation that genetic inactivation of daf-12 or din-1 significantly elicits ROS formation during starvation supports this idea.

Starvation response protects mice and yeast against oxidative stress28,29. Meanwhile, constitutive activation of the detoxification/antioxidant response factor SKN-1/Nrf-1 induces a starvation adaptation response in C. elegans and mice30. In this study, our results indicate that starvation promotes the resistance to oxidative and heat stresses in adult worms, which is dependent on the DAF-12/DIN-1S complex. These results imply that starvation and antioxidant defense are intimately linked with each other. Indeed, a previous study has demonstrated that the antioxidant genes that detoxify ROS are correlated with starvation survival in yeast26. We found that DAF-12/DIN-1S controls expression of several antioxidant genes, such as gst-4 and gst-10 and. Knockdown of gst-4 increases the abundance of ROS, and worm death during starvation. More importantly, suppression of ROS by NAC partially rescues worm death in daf-12(rh61rh411) or din-1(dh127) mutants. These results suggest that the DAF-12/DIN-1S complex confers starvation resistance, at least in part, by a mechanism of its action involved in the antioxidant defense. To counter against elevated ROS-induced tissue injury, compensatory antioxidant response is crucial for starvation tolerance. Clearly, the mechanism underlying the DAF-12/DIN-1S complex-mediated antioxidant response needs to be investigated further in light of our current results.

At present, the mechanisms underlying death of the whole organism after nutrient deprivation remain incompletely understood. Although apoptosis occurs in germ cells of worms after nutrient deprivation12,31, our results demonstrated that inactivation of the apoptosis gene cascade fails to prevent worm death, excluding a role for apoptosis in this process. We found that starvation triggers systemic necrosis in daf-12(rh61rh411) and din-1(dh127) mutants. Genetic inactivation of components in the necrosis pathway (calpains and cathepsins) can delay worm death, confirming a role for systemic necrosis in starvation-induced organismal death. Although we tested the effect of five calpains and six aspartyl proteases on worm death, however, only knockdown of tra-3 and asp-4 by RNAi inhibits worm death. In this study, we tested the knockdown efficiency of RNAi on knockdown of all of the calpains and aspartyl proteases, and found these genes expressions were significantly ablated by RNAi. However, we really do not know why only knockdown of tra-3 and asp-4 displays a significant protection. As the antioxidant NAC significantly suppresses systemic necrosis in daf-12(rh61rh411) and din-1(dh127) mutants during starvation, ROS is likely to be involved in systemic necrosis.

In summary, our results demonstrate in C. elegans that DAF-12/DIN-1S, which is activated during starvation, up-regulates antioxidant genes. Induction of antioxidant responses clears the detrimental effects of ROS on worm tissues, and ultimately promotes survival during starvation. Increased antioxidant response seems to be a common phenomenon among many organisms during nutrient deprivation. Thus, dysregulation of antioxidant response contributes to cell death in the process.

Materials and Methods

Nematode strains

The C. elegans strains were cultured under standard conditions and fed E. coli OP5032. Wild-type animals were C. elegans Bristol N2. Mutated strains used in this stud, including daf-12(rh61rh411), din-1(dh127), tbh-1(n3247), and strains containing mir-84p::GFP, mir-241p::GFP, and Pgst-4::gst-4::GFP, were kindly provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

RNA interference

The clones of genes for RNAi were from the Ahringer library33. All RNAi was induced by feeding on synchronized L1 larvae at 20 °C. These worms were cultivated at 20 °C until the young adult stage. Then young adult worms were transferred to the NGM plates for further assays.

Oxidative and heat stress experiments

After synchronized young adult worms were starved for 12 h, the worms were transferred to plates containing 10 mM menadione (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in the absence of standard food Escherichia coli OP50. Well-fed young adult worms in plates containing 10 mM menadione, and E. coli OP50 were used as control. For heat stress, 40–50 young adult worms were transferred to plates in the absence of E. coli OP50 at 35 °C. Well-fed young adult worms in the presence of E. coli OP50 were used as control. The number of living worms was counted at 5 h intervals until all of the worms were dead. Immobile worms unresponsive to touch were scored as dead. Three plates were performed per assay and all experiments were performed three times.

Starvation survival analysis

Synchronized populations of L1 larva were cultivated on NGM plates in the presence of E. coli OP50 at 20 °C until the young adult stage. 40–50 worms were then transferred to NGM agar plates containing 5′-fluoro- 2′-deoxyuridine (FUdR) (75 μg/ml), ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), and amphotericin-B (0.25 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of E. coli OP50 at 20 °C. The number of living worms was counted at five days. Immobile worms unresponsive to touch were scored as dead. Three plates were performed per assay and all experiments were performed three times.

Detection of apoptosis

After worms were starved for two days, the worms were staining with M9 medium containing 20 μM SYTO 12 green (Invitrogen) for 90 min14. Then the worms were mounted in M9 onto microscope slides. The green fluorescence was monitored using a Nikon e800 fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). At least 25 worms were examined under each condition in three independent experiments.

Analysis for necrosis

After worms were starved for two days, the worms were stained in M9 medium containing 1 mM acridine orange (Sangon Biotech Co., Shanghai, China)15, or 20 mg/ml uranine (Sangon)16 for 2 h. After washing with M9 medium for three times, the worms were mounted in M9 onto microscope slides. The red fluorescence of acridine orange and the green fluorescence of uranine were monitored using a Nikon e800 fluorescence microscope. At least 25 worms were examined under each condition in three independent experiments.

Fluorescence microscopic analysis of GFP-labeled worms

For mir-84p::GFP, mir-241p::GFP, and Pgst-4::gst-4::GFP analysis, synchronized young adult worms were starved for 12 h. Then the worms were mounted in M9 onto microscope slides. The slides were imaged using a Nikon e800 fluorescence microscope. Fluorescence intensity was quantified by using the ImageJ software (NIH). Mean value and standard errors were calculated based on more than 100 worms under each condition in three independent experiments.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from worms with TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen). Random-primed cDNAs were generated by reverse transcription of the total RNA samples with SuperScript II (Invitrogen). A real time-PCR analysis was conducted using SYBR® Premix-Ex TagTM (Takara, Dalian, China) on a Roche LightCycler 480® System (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany). The primers used for PCR were as follows: gst-4: 5′-TGG AGA CTC ATT GAC TTG GG-3′ (F), 5′-TCC TTT CTT GTT GCC ACG-3′ (R); gst-10: 5′-CGT GCC ACA ACT TTA CTA CTT C-3′ (F), 5′-CAA CTG ACC AAG GAG CAT TC-3′(R); act-1: 5′-GGG CGA AGA AGG AAA TGG TC-3′ (F), 5′-CAG GTG GCG TAG GTG GAG AA-3′ (R).

Measurement of ROS

After starvation for 24 h, the ROS levels were detected by 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) as a probe as described previously34. Meanwhile, ROS formation was also detected using two fluorescent dyes dihydroethidium (DHE) and CellROX® Deep Red Reagent, respectively. Briefly, after 24 h of starvation, worms were incubated with 3 μM of DHE in M9 medium for 30 min. Then worms were washed three with PBS, and mounted in M9 onto microscope slides. For ROS detection using CellROX® Deep Red Reagent, worms were fixed by 2% of paraformaldehyde for 30 min. After washed with M9 medium for three times, the worms were incubated with 5 μM of CellROX® Deep Red Reagent for 1 h. Then worms were washed three with PBS, and mounted in M9 onto microscope slides. The slides were imaged using a Nikon e800 fluorescence microscope. Mean value and standard errors were calculated based on more than 100 worms under each condition in three independent experiments.

Statistics

The statistical significance of differences in gene expression, starvation survival, and fluorescence intensity was assessed by performing a one-way ANOVA followed by a Student-Newman-Keuls test. Differences in survival rates for oxidative/ heat stress treatment were analyzed using the log-rank test. Data were analyzed using SPSS17.0 software (SPSS Inc.).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Tao, J. et al. Antioxidant response is a protective mechanism against nutrient deprivation in C. elegans. Sci. Rep. 7, 43547; doi: 10.1038/srep43547 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for worm strains. This work was supported in part by grants (2013CB127500) from National Basic Research Program of China (973), a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (311171365).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions C.G.Z., Q.Y.W., J.T. and Y.C.M. designed the experiments and analyzed the data. Q.Y.W., J.T. and Y.C.M. and Y.L.C. performed the experiments. C.G.Z., Q.Y.W., J.T. and Y.C.M. interpreted the data. Q.Y.W., J.T. and C.G.Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

References

- Fukuyama M., Rougvie A. E. & Rothman J. H. C. elegans DAF-18/PTEN mediates nutrient-dependent arrest of cell cycle and growth in the germline. Curr Biol 16, 773–779 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle D. L., Swanson M. M. & Albert P. S. Interacting genes in nematode dauer larva formation. Nature 290, 668–671 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelo G. & Van Gilst M. R. Starvation protects germline stem cells and extends reproductive longevity in C. elegans. Science 326, 954–958 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo H., Shim J., Lee J. H., Lee J. & Kim J. B. IRE-1 and HSP-4 contribute to energy homeostasis via fasting-induced lipases in C. elegans. Cell Metab 9, 440–448 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke E. J. & Ruvkun G. MXL-3 and HLH-30 transcriptionally link lipolysis and autophagy to nutrient availability. Nat Cell Biol 15, 668–676 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielenbach N. & Antebi A. C. elegans dauer formation and the molecular basis of plasticity. Genes Dev 22, 2149–2165 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollam J. & Antebi A. Sterol regulation of metabolism, homeostasis, and development. Annu Rev Biochem 80, 885–916 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J., Ma Y. C., Yang Z. S., Zou C. G. & Zhang K. Q. Octopamine connects nutrient cues to lipid metabolism upon nutrient deprivation. Science advances 2, e1501372 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerisch B. et al. A bile acid-like steroid modulates Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan through nuclear receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 5014–5019 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao W., Gaudet J., Kent W. J., Muttumu S. & Mango S. E. Environmentally induced foregut remodeling by PHA-4/FoxA and DAF-12/NHR. Science 305, 1743–1746 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethke A., Fielenbach N., Wang Z., Mangelsdorf D. J. & Antebi A. Nuclear hormone receptor regulation of microRNAs controls developmental progression. Science 324, 95–98 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas L. S., Maldonado E. & Navarro R. E. Stress-induced germ cell apoptosis by a p53 independent pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Death Differ 13, 2129–2139 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth M. L., Simon P., Kovacs A. L. & Vellai T. Influence of autophagy genes on ion-channel-dependent neuronal degeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Sci 120, 1134–1141 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamo A. et al. Transgene-mediated cosuppression and RNA interference enhance germ-line apoptosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 3440–3445 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artal-Sanz M., Samara C., Syntichaki P. & Tavernarakis N. Lysosomal biogenesis and function is critical for necrotic cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol 173, 231–239 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn C. et al. Anthranilate fluorescence marks a calcium-propagated necrotic wave that promotes organismal death in C. elegans. PLoS Biol 11, e1001613 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syntichaki P., Xu K., Driscoll M. & Tavernarakis N. Specific aspartyl and calpain proteases are required for neurodegeneration in C. elegans. Nature 419, 939–944 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke C. J. et al. An intracellular serpin regulates necrosis by inhibiting the induction and sequelae of lysosomal injury. Cell 130, 1108–1119 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiers B. et al. A stress-responsive glutathione S-transferase confers resistance to oxidative stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic Biol Med 34, 1405–1415 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyadevara S. et al. Lifespan and stress resistance of Caenorhabditis elegans are increased by expression of glutathione transferases capable of metabolizing the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal. Aging Cell 4, 257–271 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark K. A. et al. Vitamin D Promotes Protein Homeostasis and Longevity via the Stress Response Pathway Genes skn-1, ire-1, and xbp-1. Cell reports 17, 1227–1237 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W. & Hekimi S. A mitochondrial superoxide signal triggers increased longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol 8, e1000556 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwee J. J., Schuster E., Blanc E., Thomas J. H. & Gems D. Shared transcriptional signature in Caenorhabditis elegans Dauer larvae and long-lived daf-2 mutants implicates detoxification system in longevity assurance. J Biol Chem 279, 44533–44543 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L. M. et al. Proteomic analyses of Caenorhabditis elegans dauer larvae and long-lived daf-2 mutants implicates a shared detoxification system in longevity assurance. J Proteome Res 9, 2871–2881 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. & Kim S. K. Global analysis of dauer gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 130, 1621–1634 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petti A. A., Crutchfield C. A., Rabinowitz J. D. & Botstein D. Survival of starving yeast is correlated with oxidative stress response and nonrespiratory mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, E1089–1098 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayir A. et al. Metabolic responses to prolonged starvation, food restriction, and refeeding in the brown trout, Salmo trutta: oxidative stress and antioxidant defenses. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 159, 191–196 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaghello L. et al. Starvation-dependent differential stress resistance protects normal but not cancer cells against high-dose chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 8215–8220 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Keller A. J., Umberger G., McFall R. & Mattson M. P. Food restriction reduces brain damage and improves behavioral outcome following excitotoxic and metabolic insults. Ann Neurol 45, 8–15 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paek J. et al. Mitochondrial SKN-1/Nrf mediates a conserved starvation response. Cell Metab 16, 526–537 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gilst M. R., Hadjivassiliou H. & Yamamoto K. R. A Caenorhabditis elegans nutrient response system partially dependent on nuclear receptor NHR-49. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 13496–13501 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath R. S. & Ahringer J. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods 30, 313–321 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou C. G., Tu Q., Niu J., Ji X. L. & Zhang K. Q. The DAF-16/FOXO transcription factor functions as a regulator of epidermal innate immunity. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003660 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.