Abstract

Aims:

The aim of this study was to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) DNA with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in aqueous or vitreous samples of patients suffering from choroiditis presumed to be infectious origin.

Settings and Design:

Hospital-based, retrospective case–control study.

Subjects and Methods:

In all, forty eyes of forty patients with choroiditis divided into two groups – Group A (serpiginous-like choroiditis, ampiginous choroiditis, multifocal choroiditis) and Group B (choroidal abscess, miliary tuberculosis (TB), choroidal tubercle) were analyzed retrospectively. In 27 controls (patients without uveitis undergoing phacoemulsification), anterior chamber aspirate was done and sample subjected to real-time PCR. Patients underwent nested PCR for MTB using IS6110 and MPB64 primers from aqueous (n = 39) or vitreous (n = 1). All patients underwent detailed ophthalmological examination by slit-lamp biomicroscopy, fundus examination by indirect ophthalmoscopy, and fundus photograph and fundus fluorescein angiography if required.

Statistical Analysis:

Positive results of PCR for MTB within the group and between two groups were statistically analyzed using Chi-square test.

Results:

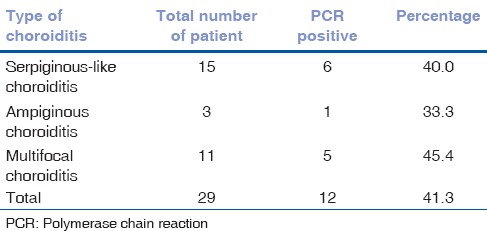

There were 25 males and 15 females. Mean age at presentation was 34.66 years (range, 14–62). PCR positivity rates were 41.3% (n = 12/29) and 81.82% (n = 9/11) in Groups A and B, respectively. No controls had PCR-positive result. Comparison of PCR positivity rates showed statistically significant difference between Groups A and B (P = 0.028). Systemic TB was detected in 57.14% (n = 12/21) of all PCR-positive cases (Group A - 33.3%, n = 4/12; Group B - 88.9%, n = 8/9). Systemic antitubercular treatment (ATT) for 9 months and oral steroids were successful in resolution of choroiditis in all PCR-positive patients (n = 21) without disease recurrence.

Conclusions:

Eyes with choroiditis of suspected/presumed tubercular origin should be subjected to PCR for diagnosis of TB and subjected to ATT for prevention of recurrences.

Keywords: Antitubercular treatment, choroiditis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, polymerase chain reaction

Tuberculosis (TB) is currently a major public health problem, especially in the developing countries. The World Health Organization has declared TB to be a global emergency.[1,2,3] Intraocular TB is a common cause of posterior uveitis in India and is usually secondary to hematogenous spread of infection from a systemic focus. It is known to involve various segments of the eye and presents with protean manifestations including choroiditis, serpiginous-like choroiditis (SLC), choroidal tubercles (CTs), choroidal tuberculoma, and subretinal abscess.[4] Even 19th-century documents state that intraocular TB characteristically presents as a focus in the choroid.[5] There are various reports in literature, which suggest presumable diagnosis of ocular TB right from variable clinical presentation, obtaining ocular tissue, isolating the organism to nonspecific and nonsensitive diagnostic tests.[6]

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifies DNA of small genomic sequences obtained from very minute quantities of tissue samples. This has thus helped in isolating and identifying organisms which were previously difficult to detect.

The present study was conducted to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) DNA with nested PCR in aqueous or vitreous samples of patients suffering from choroiditis presumed to be infectious origin.

Subjects and Methods

In all, forty eyes of forty patients with choroiditis were divided into Group A (SLC, ampiginous choroiditis, and multifocal choroiditis [MFC], n = 29) and Group B (choroiditis of suspicious tubercular etiology - choroidal abscess [CA], miliary TB [MT], and CT, n = 11) examined at the uvea clinic were analyzed retrospectively. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. All the enrolled patients underwent detailed ophthalmological examination including slit-lamp biomicroscopy and fundus examination by indirect ophthalmoscopy. Fundus photograph and fundus fluorescein angiogram was done as and when required. The patients were examined as to the predominant location of uveitis, possible etiology, and extent of uveitis.

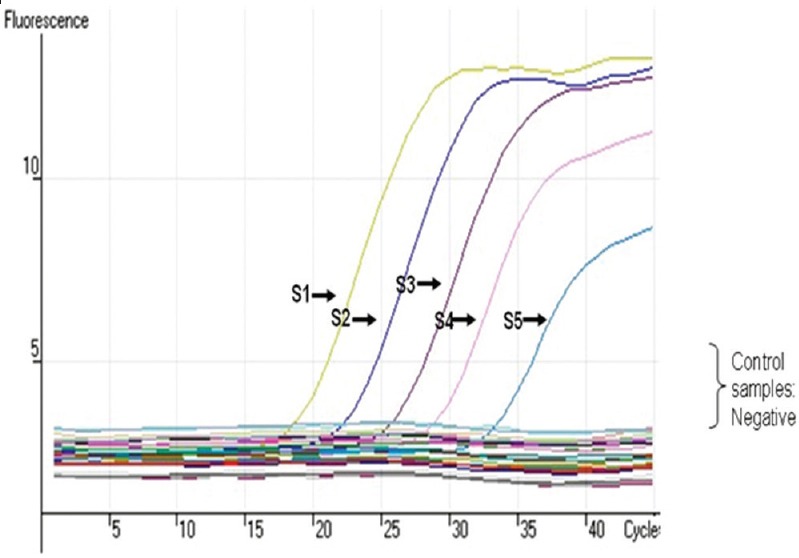

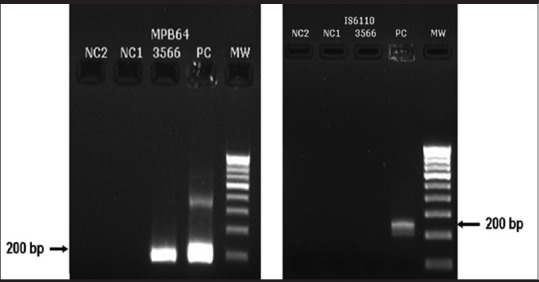

All patients underwent nested PCR for MTB using IS6110 and MPB64 primers from mainly aqueous aspirate. Vitreous sample was collected in one patient. PCR was performed under stringent conditions to minimize the possibility of false positive results. All equipment and reagents were screened for use in PCR with DNA extraction and PCR done in dedicated rooms. Real-time quantification of MTB DNA was done in all nested PCR positive cases. In 27 subjects, as a control, we collected anterior chamber aspirate of patients without uveitis undergoing phacoemulsification and subjected the samples to real-time PCR. All PCR MTB (IS6110, MPB64, or both) positive patients underwent systemic evaluation by a physician. The procedure for PCR has been described elsewhere.[7]

Positive results of PCR for MTB within the group and between two groups were statistically analyzed using Chi-square test.

Results

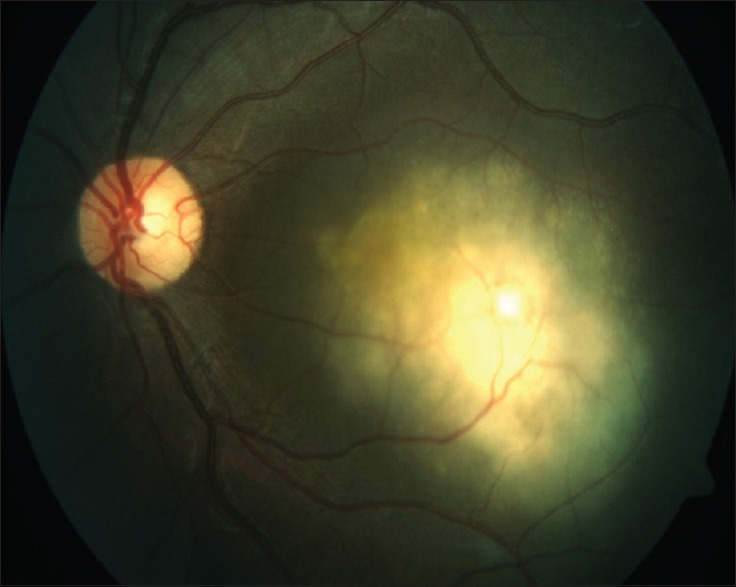

There were 25 males and 15 females. The mean age at presentation was 34.66 years (range, 14–62). Fig. 1 shows real-time PCR quantification results of patients and controls. Fig. 2 shows nested PCR positivity for MPB64 and IS6110 genomes of MTB. Figs. 3–5 show fundus images of patients in the study. PCR was positive in 57.14% of all patients (Group A, n = 12, Group B, n = 9). PCR positivity was to the extent of 41.3% in Group A (n = 12/29). The numbers were higher in Group B - 81.8% (n = 9/11). The difference of PCR MTB positive result between the two groups was statistically significant (P = 0.028). No controls had PCR positive for MTB DNA. Tables 1 and 2 show the nested PCR subgroup analysis results of Groups A and B, respectively. Among the PCR MTB positive patients, 33.33% (n = 4/12) in Group A and 88.8% (n = 8/9) in Group B had evidence of systemic TB. All PCR MTB positive patients (n = 21) were treated successfully with a course of antitubercular treatment (ATT) for 9 months and oral steroids resulting in resolution of choroiditis without recurrence of disease.

Figure 1.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction quantification report of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA S1-5 with negative controls

Figure 2.

Nested polymerase chain reaction-positive results for MPB64 and IS6110 genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis

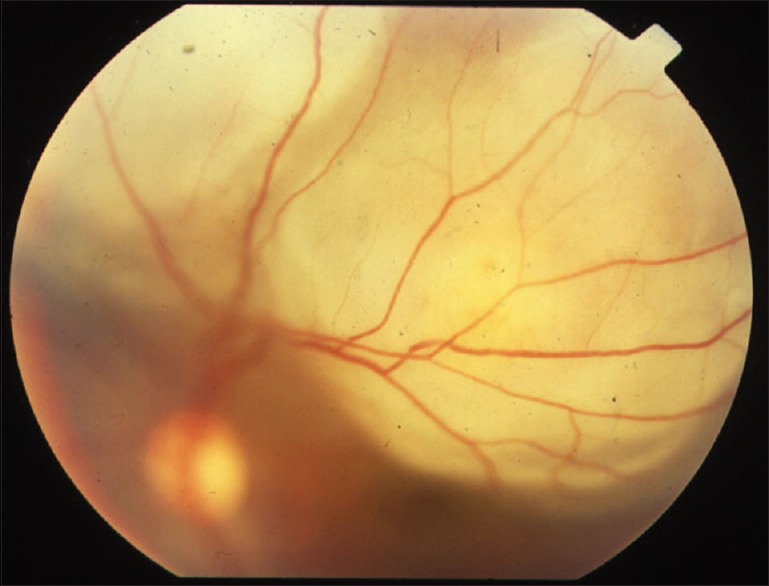

Figure 3.

A case of a 50-year-old male diagnosed as a case of tuberculoma involving the macula. Aqueous tap sample showed nested polymerase chain reaction positive for MPB64 and IS6110 genome

Figure 5.

Color fundus montage of a 43-year-old male diagnosed as serpiginous choroiditis. Aqeuous tap was positive for MPB64 and IS6110 genome

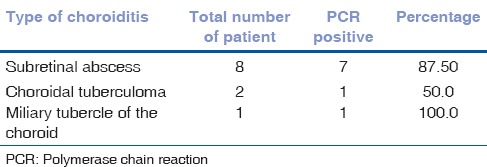

Table 1.

Polymerase chain reaction-positive rates in Group A

Table 2.

Polymerase chain reaction-positive rates in Group B

Figure 4.

A case of a 34-year-old female diagnosed as a case of subretinal abscess involving the superior retinal quadrants. Aqueous tap sample showed nested polymerase chain reaction positive for MPB64 and IS6110 genome

None of the patients had paradoxical worsening of the disease after treatment with ATT and oral steroids.

Discussion

PCR for MTB was diagnostically productive in both the groups of patients with choroiditis, and it was more significant in patients with Group B manifestation of disease, i.e., choroiditis, which are suspected to be of tubercular etiology. The identification of a choroidal lesion and its etiology is important because it may be the first clue to the diagnosis of MT,[8] which may represent the only manifestation of a tuberculous focus elsewhere in the body. The untreated, infected person carries the risk of TB for a lifetime and can perpetuate the disease in a population. The initiation of early therapy will have positive benefits for the patient, health-care professionals, and spread of TB in the community. PCR has been shown to be both specific and sensitive.[9] It relies on the declaration of a specific DNA sequence of the MTB complex. It is more sensitive than direct examination and more rapid than culture.[10] Cases without identification of acid-fast stain on staining and no growth of MTB on culture may be identified by PCR.[11,12] If bacilli are nonviable, mycobacterial DNA would still be present for detection by PCR. There have been case reports of successful treatment of MFC with ATT and course of oral steroids after detection of MTB DNA by PCR.[12,13] Retrospective studies have found MTB DNA by PCR of aqueous or vitreous samples in 77.2%–88.9% of patients with choroiditis.[14,15]

Although obtaining aqueous sample for detection of MTB by PCR is an invasive procedure, these results suggest that eyes, especially with Group B (CT, CA, MT), which are suspected to be of tubercular origin should be subjected to above test since an early diagnosis and treatment may lead to improved clinical outcome. ATT in these patients could help by killing the intraocular microorganism; thus resulting in reduced antigen load, and hence, resultant inflammation. Although the inflammation can be controlled initially by the use of oral steroids alone, elimination of recurrences in patients treated with ATT strongly favors the use of specific therapy in PCR-positive patients.

Every attack of choroiditis leaves its scar on the choroid in the form of a lesion and on the patient in the form of reduced vision. It is especially important to provide cure for such patients as the disease has in most cases a bilateral presentation with multiple relapsing episodes. Furthermore, the adverse effects of long-term use of steroids in the form of diabetes, hypertension, weight gain, acneiform lesions, depression as well as those of other immunosuppressants need attention. In view of all above considerations, we believe that the eyes with CT, CA, SLC, and multifocal choroiditis of suspected tubercular origin should be subjected to PCR for a better diagnostic and therapeutic outcome.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Shruti Agarwal, M. Sc.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Trends in tuberculosis – United States, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:245–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiologic notes and reports, expanded tuberculosis surveillance and tuberculosis morbidity – United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993;43:361–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathania V, Raviglione MC. Consensus statement. Global burden of tuberculosis: Estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring Project. JAMA. 1999;282:677–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta V, Gupta A, Rao NA. Intraocular tuberculosis – An update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:561–87. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Illingworth RS, Wright T. Tubercles of the choroid. Br Med J. 1948;2:365–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4572.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wroblewski KJ, Hidayat AA, Neafie RC, Rao NA, Zapor M. Ocular tuberculosis: A clinicopathologic and molecular study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:772–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Therese KL, Gayathri R, Dhanurekha L, Sridhar R, Meenakshi N, Madhavan HN. Diagnostic appraisal of simultaneous application of two nested PCRs targeting MPB64 gene and IS6110 region for rapid detection of M. tuberculosis genome in culture proven clinical specimens. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2013;31:366–9. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.118887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massaro D, Katz S, Sachs M. Choroidal tubercles. A clue to hematogenous tuberculosis. Ann Intern Med. 1964;60:231–41. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-60-2-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan MF, Ng WC, Chan SH, Tan WC. Comparative usefulness of PCR in the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in different clinical specimens. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:164–9. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-2-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brisson-Noël A, Gicquel B, Lecossier D, Lévy-Frébault V, Nassif X, Hance AJ. Rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis by amplification of mycobacterial DNA in clinical samples. Lancet. 1989;2:1069–71. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardman WJ, Benian GM, Howard T, McGowan JE, Jr, Metchock B, Murtagh JJ. Rapid detection of mycobacteria in inflammatory necrotizing granulomas from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue by PCR in clinically high-risk patients with acid-fast stain and culture-negative tissue biopsies. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;106:384–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/106.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shetty SB, Biswas J, Murali S. Real-time and nested polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of multifocal serpiginoid choroiditis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis – A case report. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2014;4:29. doi: 10.1186/s12348-014-0029-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhuibhar SS, Biswas J. Nested PCR-positive tubercular ampiginous choroiditis: A case report. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2012;20:303–5. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2012.685684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortega-Larrocea G, Bobadilla-del-Valle M, Ponce-de-León A, Sifuentes-Osornio J. Nested polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA detection in aqueous and vitreous of patients with uveitis. Arch Med Res. 2003;34:116–9. doi: 10.1016/S0188-4409(02)00467-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta V, Gupta A, Arora S, Bambery P, Dogra MR, Agarwal A. Presumed tubercular serpiginouslike choroiditis: Clinical presentations and management. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1744–9. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00619-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]