Abstract

Stress process theory predicts that elder mistreatment leads to declines in health, and that social support buffers its ill effects. We test this theory using nationally representative, longitudinal data from 2,261 older adults in the National Social Life Health and Aging Project. We regress psychological and physical health in 2010/2011 on verbal and financial mistreatment experience in 2005/2006 and find that the mistreated have more anxiety symptoms, greater feelings of loneliness, and worse physical and functional health five years later, than those who did not report mistreatment. In particular, we show a novel association between financial mistreatment and functional health. Contrary to the stress buffering hypothesis, we find little evidence that social support moderates the relationship between mistreatment and health. Our findings point to the lasting impact of mistreatment on health, but show little evidence of a buffering role of social support in this process.

Keywords: Verbal mistreatment, financial mistreatment, anxiety, loneliness, ADLs, stress process theory

Introduction

Elder mistreatment affects slightly more than 10% of the older adult population (Acierno et al., 2010). As the U.S. population ages (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014), the number of mistreatment victims is likely to increase. Yet, empirical research to date on the long-term consequences of elder mistreatment is limited (Choi & Mayer, 2000). Understanding the health outcomes of elder mistreatment can direct the development of interventions and policies to aid victims of abuse.

Guided by the stress process framework, the current study models the physical and psychological health consequences of two types of elder mistreatment using nationally representative, longitudinal data from the National Social Life Health and Aging Project (NSHAP). Following the propositions of the stress process theory, we also test whether social support buffers the ill effects of mistreatment. We use our findings to develop a conceptual understanding of elder mistreatment, social support, and health, and recommend courses of action to support mistreated elders.

Theoretical Background

Elder mistreatment is defined as “(a) intentional actions that cause harm or create a serious risk of harm, whether or not intended, to a vulnerable elder by a caregiver or other person who stands in a trust relationship to the elder, or (b) failure by a caregiver to satisfy the elder’s basic needs or to protect the elder from harm” (Bonnie & Wallace, 2003). As such, elder mistreatment can be conceptualized as a stressor, and the stress process framework (Pearlin, 1989; Pearlin et al., 1981; Pearlin et al., 2005) can aid us in formulating hypotheses about the health outcomes of mistreatment victims.

The stress process theory posits that adverse life events, important life transitions, and life strains all initiate efforts to cope. Coping entails changes in an individual’s behaviors and emotional responses in an effort to manage these stressors. If stressors continue to mount, physical and psychological reserves become exhausted, and the susceptibility to illness, disease, or psychological distress increases. In other words, negative events and experiences cause a loss of personal resources – physical, emotional, or otherwise – that reduces one’s ability to resist declines in health and well-being (Hobfoll, 2001), which in turn results in worse health.

According to the stress process model, elder mistreatment will trigger coping behaviors that drain personal resources, and result in physical and emotional deficits. Consistent with this theoretical idea, empirical work shows an association between elder mistreatment and poor health (e.g., Amstadter et al., 2010; Lachs et al., 1998; Schofield, Powers, & Loxton, 2013). Mistreatment is linked to psychological distress (Luo & Waite, 2011), disability (Schofield et al., 2013), and mortality (Dong et al., 2009; Lachs et al., 1998; Schofield et al., 2013). Luo and Waite (2011), for example, find that elder mistreatment in the past year is associated with later psychological distress. In another study, Dong and colleagues (2009) show that elder abuse is associated with significantly increased risks of overall mortality.

The stress process model also recognizes that social resources are possible moderators of this relationship (Pearlin, 1989; Pearlin et al., 1981; Thoits, 2010). Significant others such as family members and friends can offer emotional, informational, and instrumental assistance in times of hardship. Differences in the availability of social support may explain why some individuals are better able to cope with similarly stressful conditions. According to this proposition, victims of elder mistreatment with greater levels of social support will be more likely to receive emotional, informational, and instrumental resources, and thus be buffered against mistreatment’s ill effects. Indeed, empirical research provides some evidence that social support is a protective factor for the mistreated elderly (e.g., Cisler et al., 2012; Comijs et al., 1999; Luo & Waite, 2011). For instance, levels of global happiness are higher and levels of psychological distress are lower among mistreated older adults if they also report more positive social support, higher social participation, and more feelings of social connectedness (Luo & Waite, 2011). Other studies report a similar buffering effect of social support on a variety of outcomes, including later psychological distress (Comijs et al., 1999) and mortality risk (Dong et al., 2011).

While previous researchers document an association between mistreatment and health, and a possible moderating effect of social support on this relationship, they rely on cross-sectional data that prevent an understanding of the causal relationships between mistreatment, social support, and health. For instance, Luo and Waite’s (2011) findings suggest that past mistreatment is associated with current emotional well-being, but the cross-sectional data mean that psychological distress in the past week may color one’s recollection of past events, increasing the chances that the same experience was reported as mistreatment by those now distressed for other reasons but not by others. This possibility could render the causal link between mistreatment and distress spurious; a longitudinal study would verify the ordering of this relationship.

Cross-sectional data also obfuscates whether the timing of social support matters for buffering the negative effects of mistreatment. It is possible that social support that is concurrent with mistreatment buffers a victim from its immediate negative consequences, resulting in better health later on. Later social support may further slow declines in health. While one study suggests that social support is associated with concurrent emotional health, but not later well-being (Newsom, Nishishiba, Morgan, & Rook, 2003), an analysis of longitudinal data with repeated measures of social support will allow us to systematically examine whether the availability of social support at different times moderates the relationship between elder mistreatment and well-being. These findings could inform interventions emphasizing increasing social support to mistreated elders.

Based on this review we propose that elder mistreatment predicts worse psychological and physical health later on. We also propose that, in addition to having direct effects on psychological and physical well-being, social support at both points in time will interact with mistreatment and buffer its effects. Our formal hypotheses are:

-

H1.

Elder mistreatment increases the risks of declines in later psychological and physical health

-

H2.

Past and concurrent social support moderates and reduces the effect of past elder mistreatment on current psychological and physical health

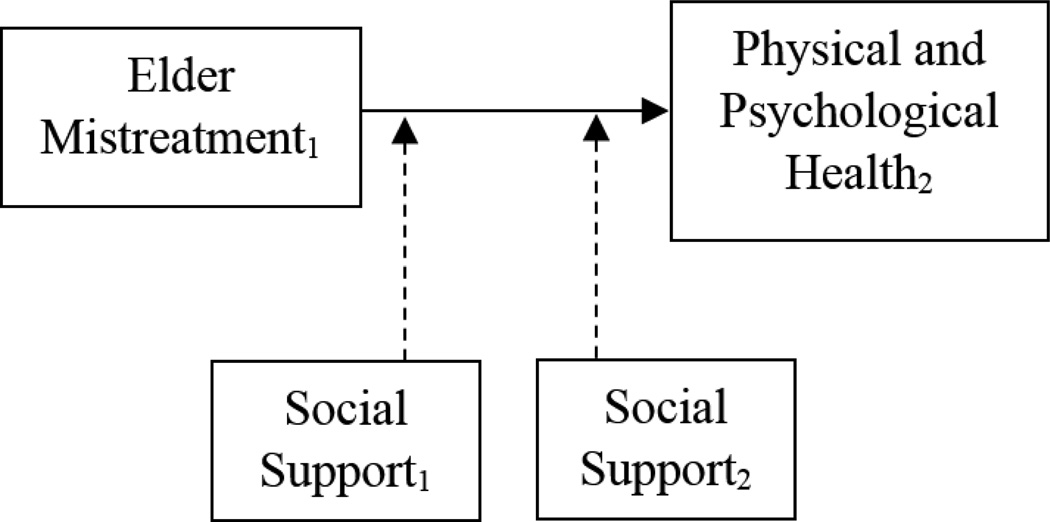

Figure 1 depicts our conceptual model of elder mistreatment and well-being over time, and summarizes the hypotheses we test in this study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Elder Mistreatment and Well-Being Over Time

Note: Dotted lines indicate possible moderating effects

In response to scholars’ call to distinguish the different types of elder mistreatment when identifying the links between mistreatment and vulnerability (e.g., Dong et al., 2012; Rabiner, O’Keeffe, & Brown, 2004), we apply this framework to two types of elder mistreatment. Verbal mistreatment, a type of psychological or emotional abuse which includes threats, insults, and humiliation or infantilization, is reported by 4% to 9% of older adults (Acierno et al., 2010; Laumann, Leitsch, & Waite, 2008). Empirical work suggests that verbal mistreatment in the elderly is strongly linked to emotional health outcomes such as greater reports of depression and anxiety (Cisler et al., 2012; Dong et al., 2012). Less is known about the relationship between verbal mistreatment and physical health among older adults, but since research in domestic violence (e.g., Plichta, 2004) and child abuse (e.g., Spertus et al., 2003) suggests that emotional mistreatment may be related to worsening physical health, it is possible that verbal mistreatment at older ages is linked to similar physical health consequences.

Financial mistreatment is the illegal or improper use of an elder’s funds, property, or assets by someone known to the victim or by a stranger (Conrad et al., 2011). Taking money or property, forcing an elderly person to sign financial documents, and denying an elderly person control over his or her assets are some examples of this type of abuse (Hafemeister, 2003). An estimated 3.5% to 5% of the elderly population has experienced this type of mistreatment (Acierno et al., 2010; Laumann et al., 2008). Older adults may be especially harmed by financial abuse because it results in a loss of assets that cannot be recovered. Retired older adults may rely on fixed incomes to access products, care, and treatments necessary to maintain their psychological and physical health. As such, financial mistreatment may have an indirect effect on physical and psychological health by preventing elders from accessing resources that support health and well-being. Further, financial abuse may have a direct effect on psychological well-being. Because financial mistreatment prevents access to one’s own material resources, it can potentially damage one’s sense of mastery or control (Pearlin et al., 2007). This loss of perceived personal control may be particularly damaging to self-esteem and self-efficacy in older adults who are already facing reduced physical capabilities and diminished social roles (Baltes & Smith, 2003). As a result, older adults may face negative psychological consequences (Hafemeister, 2003).

Data and Methods

Data and Sample

We use data from W1 and W2 of the National Social Life Health and Aging Project (NSHAP) to test this study’s hypotheses. NSHAP is a nationally representative study of health and social relationships among older Americans. NSHAP collaborated with the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to obtain a sampling frame of U.S. households containing age-eligible individuals, and then used a multiple-stage probability sampling method to randomly select individuals for participation in the study. The complex sample design balanced age and gender subgroups, but oversampled Blacks and Hispanics. For W1 in 2005-06, NSHAP obtained an overall response rate of 75.5%, resulting in a sample of 3,005 adults aged 57–85 (O’Muircheartaigh, Eckman, & Smith, 2009; Waite et al., 2014a). Five years later in 2010-11 NSHAP re-interviewed 2,261 surviving W1 respondents (as well as 161 W1 non-respondents and 955 spouses and cohabiting romantic partners) for W2 (O’Muircheartaigh, English, Pedlow, & Kwok 2014; Waite et al., 2014b). Data for both waves are collected by an interviewer-administered in-home questionnaire, an in-home biomeasure collection procedure, and a self-administered post-interview questionnaire (leave-behind questionnaire or LBQ).

The 2,261 respondents with data in both study waves make up the sample for this study. The average age of the sample in W2 was 73 years, and a little over half the sample (52.10%) was female. The majority of the sample was White (70.77%), and most respondents were married (57.05%), though a substantial proportion was widowed (26.32%). Unweighted descriptive statistics for the sample appear in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| W2 Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Total N | 2261 | Race/Ethnicity | |

| Age | 73 (62–91) | White | 70.77% |

| Female | 52.10% | Black | 16.66% |

| Hispanic | 10.31% | ||

| Marital Status | Other | 2.27% | |

| Married | 57.05% | ||

| Living with a Partner | 2.08% | Education | |

| Separated | 1.24% | Less than High School | 20.10% |

| Divorced | 10.22% | High School | 25.08% |

| Widowed | 26.32% | Vocational/Some College | 30.47% |

| Never Married | 3.10% | College | 24.24% |

| Key Study Variables | |||

| Total %/ȳ (Range) | Mistreatment By Kin | Mistreatment By Others | |

| W1 Verbal Mistreatment | 15.40% | 8.72% | 6.68% |

| W1 Financial Mistreatment | 5.80% | 3.35% | 2.45% |

| Verbal Mistreatment | Financial Mistreatment | ||

| W1 Anxiety Symptoms | 3.49 (0–21) | 4.58 | 4.57 |

| W1 Felt Loneliness | 0.99 (0.6) | 1.75 | 1.50 |

| W1 Comorbidity Index | 2.61 (0–21) | 2.75 | 2.72 |

| W1 ADLs | 0.44 (0–5) | 0.53 | 0.57 |

| W2 Anxiety Symptoms | 4.68 (0–21) | 5.70 | 5.48 |

| W2 Felt Loneliness | 1.16 (0–6) | 1.62 | 1.50 |

| W2 Comorbidity Index | 2.53 (0–21) | 2.79 | 2.61 |

| W2 ADLs | 0.50 (0–5) | 0.55 | 0.69 |

| W1 Spouse Support | 1.97 (0–3) | 1.79 | 1.74 |

| W1 Family Support | 2.45 (0–3) | 2.40 | 2.31 |

| W1 Friend Support | 2.10 (0–3) | 2.15 | 2.15 |

| W2 Spouse Support | 1.74 (0–3) | 1.67 | 1.67 |

| W2 Family Support | 2.44 (0–3) | 2.42 | 2.35 |

| W2 Friend Support | 2.05 (0–3) | 2.09 | 2.10 |

Note: Numbers reported are unweighted and based on the 2,261 respondents who participated in both NSHAP waves

Supplemental analyses show that those who left the NSHAP sample due to death, illness, or other reasons were likely to be older, unpartnered, and have worse functional health and more chronic conditions than those who were re-interviewed in W2. Because we were concerned that our variables of interest were related to attrition, we tested whether mistreatment and psychological health predicted participation in W2. None of these key variables significantly predicted attrition. Nevertheless, given that much research on elder mistreatment to date has been conducted on frailer populations in assisted living and other institutionalized settings (Cooper, Selwood, & Livingston, 2008), findings based on this sample of relatively healthy elders are better able to describe the effects of elder mistreatment in the general population.

In addition to conducting this robustness check, we took two further steps to ensure the reliability of our results. First, we used the weights provided by NSHAP in all analyses to account for non-response at W2 (O’Muircheartaigh, Eckman, & Smith, 2009; O’Muircheartaigh et al., 2014). Second, to account for any other missing data1, we used -ice- in Stata 14 to multiply impute (m=5) missing values of the dependent and independent variables, and used -mi estimate- to analyze the imputed dataset. Results using listwise deletion are similar (available upon request). Besides the descriptive statistics in Table 1, all tables report results from the multiple imputation analyses.

The NSHAP data have a number of strengths for our purposes. First, while prior studies offer associational evidence linking mistreatment to worse health at one point in time, NSHAP’s longitudinal design allows us to begin documenting the causal effect of mistreatment on physical and emotional well-being. Second, NSHAP includes measures of social context that enable us to understand the impact of social resources on health and aging. Third, NSHAP’s questions about verbal and financial mistreatment allow us to explore the differences between these types of elder mistreatment. Finally, because NSHAP is representative of the elderly U.S. population, our findings are generalizable to the population of community-dwelling older adults in the U.S.

Variables

The primary independent variables are verbal mistreatment in W1 (“Is there anyone who insults you or puts you down?”) and financial mistreatment in W1 (“Is there anyone who has taken your money or belongings without your OK or prevented you from getting them even when you ask?”). These questions are based on items from the Hwalek-Sengstock Elder Abuse Screening Test (Hwalek & Sengstock, 1986) and the Vulnerability to Abuse Screening Scale (VASS; Schofield & Mishra, 2003), two well-validated screens for elder mistreatment. Each mistreatment variable is a dichotomous measure of whether a respondent experienced that type of mistreatment in the past year. Although NSHAP includes a measure of physical mistreatment in W1 (“Is there anyone who hits, kicks, slaps, or throws things at you?”), only 12 respondents reported it, so we do not analyze it in this paper.

If a respondent reports mistreatment, he or she is asked to identify the perpetrator. We separate victims mistreated by kin (e.g., spouses, children, and siblings), from those mistreated by non-kin (e.g., friends, religious leaders, and neighbors) in our analyses. Although previous work is inconsistent in accounting for the perpetrator’s identity when defining elder mistreatment (Choi & Mayer, 2000), our findings are robust to different classifications of elder mistreatment (e.g., analyzing all mistreatment cases together, identifying mistreatment by finer categories of perpetrators). For example, Bonnie and Wallace (2003) define elder mistreatment as perpetrated by a caregiver or trusted other. Our results do not change if we drop respondents mistreated by persons Bonnie and Wallace deem unlikely to be trusted others from the analyses, or if we code them as not mistreated. These supplemental analyses are available upon request. In W1, 15.40% of respondents reported experiencing verbal mistreatment (8.72% by kin and 6.68% by others), and 5.80% reported financial mistreatment (3.35% by kin and 2.45% by others).

The primary dependent variables are measures of psychological and physical health in W2. The emotional health outcomes we examine are anxiety symptoms and felt loneliness. We chose these measures because clinical studies suggest that the effects of elder mistreatment often include feelings of fear, anxiety, alienation, and shame (Dong, 2005; Wolf, 2000).

Anxiety is measured using the NSHAP Anxiety Symptoms Measure (NASM), a 7-item scale based on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A; Payne et al., 2014; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983). Respondents are asked whether in the past week:

they felt tense or “wound up”

they got a frightened feeling as if something awful was about to happen

worrying thoughts went through their mind

they could sit at ease and feel relaxed

they got a frightened feeling like butterflies in their stomach

they felt restless as if they had to be on the move

they had a sudden feeling of panic

The NASM battery assesses whether respondents experienced these seven anxiety symptoms rarely or none of the time, some of the time, occasionally, or most of the time. NASM scoring and ranges are identical to those of the well-validated HADS-A. Each of the seven items is coded from 0 to 3 (item 4 is reverse-coded), with higher numbers reflecting more frequent anxiety symptoms, and then summed into a single NASM score ranging from 0 to 21. Reliability coefficients for the NASM are 0.72 in W1 and 0.74 in W2. The average NASM score in the sample at W1 is 3.49, and the average at W2 is 4.68. The averages among those who were verbally mistreated are 4.58 in W1 and 5.70 in W2, and the averages among those who were financially mistreated are 4.57 in W1 and 5.48 in W2.

The NSHAP Felt Loneliness Measures (NFLM) is constructed using three items from the well-established Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, Peplau, & Cutrona, 1980). Respondents are asked whether they never or hardly ever, some of the time, or often felt that they lacked companionship, felt left out, or felt isolated from others during the past week. Items are scored from 0 (never or hardly ever) to 2 (often) and summed into a score ranging from 0–6, with higher numbers reflecting greater felt loneliness. Reliability coefficients for the NFLM are 0.80 in W1 and 0.79 in W2. The average NFLM score in the sample at W1 is 0.99, and is 1.16 in W2. The average scores among verbal mistreatment victims are 1.75 in W1 and 1.62 in W2. Among financial mistreatment victims average NFLM scores are 1.50 in W1 and 1.50 in W2. Further details about NSHAP’s psychological health measures are presented in Shiovitz-Ezra et al. (2009) and Payne et al. (2014).

We use two scales to measure physical health. The first is the NSHAP Comorbidity Index (NCI), which measures burden of chronic diseases and conditions. The NCI is constructed in the same manner as the validated and widely used Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI; Charlson et al., 1987), but includes additional measures for hypertension, skin cancer, bone health, and incontinence. Respondents are asked, “has a medical doctor told you that you have (had) [condition]?” for a list of 15 chronic conditions. Each confirmed condition is assigned a score of 1, 2, 3, or 6, where higher scores are assigned to conditions associated with a higher risk of mortality, and then summed to produce a score ranging from 0–21. Higher NCI scores reflect a greater burden of chronic conditions. The NCI and more commonly used CCI are highly correlated in the NSHAP sample (r = 0.89), and supplemental analyses replacing the NCI with the CCI as the outcome produce similar results (available upon request). In W1, the average NCI score in the sample is 2.60 while in W2 the average is 2.58. The NCI scores for verbal mistreatment victims are 2.78 in W1 and 2.82 in W2. The average NCI score for financial mistreatment victims is 2.67 in both waves. Further details about NCI scale construction and validation are available in Vasilopoulos et al. (2014).

The second measure of physical health in our study is a functional health scale measuring the number of difficulties with Activities of Daily Living (ADLs). Five items asking whether the respondent has any difficulty with dressing him- or herself, bathing, eating, getting in and out of bed, or toileting, are summed into an ADL score ranging from 0 to 5. Higher ADL scores indicate difficulty with a greater number of daily activities. On average, ADL scores in the sample are 0.44 in W1 and 0.50 in W2. The mistreated had more difficulties with ADLs than the whole sample in both waves (0.53 in W1 and 0.55 in W2 among verbal mistreatment victims, and 0.57 in W1 and 0.69 in W2 among financial mistreatment victims).

We also include measures of social support from spouses, family, and friends in our analyses. In both W1 and W2, respondents are asked if they generally feel they can open up to, and rely on, these significant others. Scores for support from these three sources range from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating higher levels of psychosocial support. Those who report not having spouses, family members, or friends are considered to have low levels of support, and thus receive a score of 0 for that support measure. Table 1 shows that levels of social support in the sample and among mistreatment victims are similar. For example, the average score on family support in W1 is 2.45, and the average for verbal mistreatment victims is 2.40 and the average for financial mistreatment victims is 2.31.

NSHAP did not include similar mistreatment measures in W2. Models controlling for the measures available in W2 (“How often have you felt threatened or frightened by your partner?” and “How often have you felt threatened or frightened by another family member or one of your friends?”) were inconclusive because only a subsample of respondents received these questions, preventing a precise estimate of standard errors. Cross-lagged models to assess the causal impact of W1 mistreatment on W2 health might be informative, but given data limitations, we proceed to model the effect of W1 mistreatment on W2 health without controlling for W2 mistreatment.

Analysis

We use negative binomial regression (Long, 1997) to model anxiety symptoms (NASM score), felt loneliness (NFLM score), and difficulties with activities of daily living (ADLs). We use Poisson regression to model comorbidity index (NCI) scores. These methods are appropriate for these variables with valid zeroes and long right tails in their distributions. All models are weighted for non-response and sample design (O’Muircheartaigh et al., 2009; O’Muircheartaigh et al., 2014), and include controls for gender, race, education, marital status, and age at W2. Additional control variables are added in a stepwise manner. Model 1 shows the direct effects of W1 mistreatment and W1 social support on later health after accounting for background characteristics and health status at baseline. Models 2–4 interact the W1 social support measures with W1 mistreatment to test the buffering effect of concurrent support. In Model 5 we control for W2 social support to assess its direct effect on W2 health controlling for baseline factors. Finally, Models 6–8 interact W2 social support with W1 mistreatment to test whether later social support moderates the effect of past mistreatment on later health. These eight models are estimated separately for verbal mistreatment and financial mistreatment.

Results

Psychological Health

Tables 2 and 3 contain results from regressions predicting psychological health outcomes. The first panel in each table contains the results for verbal mistreatment, and the second contains the findings for financial mistreatment. Broadly, W1 verbal mistreatment increases scores on both anxiety and loneliness symptoms scales in W2, while W1 financial mistreatment increases scores only on the W2 loneliness symptoms scale.

Table 2.

Negative Binomial Regression Predicting Log Anxiety Symptom Score

| NSHAP Anxiety Symptom Measure (0–21) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Verbal Mistreatment (vs. None) | ||||||||

| Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | 0.107* | 0.115 | 0.126 | 0.257 | 0.107* | 0.132 | 0.225 | 0.229 |

| Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.131* | 0.249* | 0.014 | 0.079 | 0.129* | 0.264** | 0.360 | −0.088 |

| W1 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | −0.012 | −0.007 | −0.012 | −0.012 | −0.001 | 0.000 | −0.002 | −0.002 |

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.003 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | −0.062 | |||||||

| Family Support | −0.052+ | −0.051 | −0.056 | −0.052 | −0.043 | −0.040 | −0.042 | −0.044 |

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.008 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.049 | |||||||

| Friends Support | −0.062* | −0.062* | −0.062* | −0.057 | −0.071* | −0.073 | −0.072** | −0.068* |

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.070 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.024 | |||||||

| W2 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | −0.069* | −0.062* | −0.070* | −0.070** | ||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.014 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | −0.078 | |||||||

| Family Support | −0.024 | −0.025 | −0.012 | −0.025 | ||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.048 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | −0.095 | |||||||

| Friends Support | 0.033 | 0.036 | 0.035 | 0.028 | ||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.058 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.100 | |||||||

| W1 Psychological Health Status | 0.068*** | 0.068*** | 0.068*** | 0.068*** | 0.068*** | 0.068*** | 0.068*** | 0.068*** |

| Constant | 1.223*** | 1.214*** | 1.230*** | 1.215*** | 1.377*** | 1.361*** | 1.348*** | 1.391*** |

| Minimum Number of Observations | 12874 | 12874 | 12874 | 12874 | 12872 | 12872 | 12872 | 12872 |

| Financial Mistreatment (vs. None) | ||||||||

| Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.081 | 0.142 | 0.144 | 0.039 | 0.073 | 0.130 | −0.247 | −0.456 |

| Financial Mistreatment by Others | −0.136 | −0.287 | −0.449 | −0.426 | −0.144 | −0.094 | 0.238 | 0.377 |

| W1 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | −0.016 | −0.016 | −0.017 | −0.017 | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.004 | −0.003 |

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.041 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.069 | |||||||

| Family Support | −0.053+ | −0.053+ | −0.056 | −0.054 | −0.043 | −0.044 | −0.043 | −0.045 |

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.027 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.133 | |||||||

| Friends Support | −0.062* | −0.062* | −0.062* | −0.064* | −0.071* | −0.071** | −0.072** | −0.071** |

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.019 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.131 | |||||||

| W2 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | −0.069* | −0.067* | −0.071** | −0.070* | ||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.039 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | −0.027 | |||||||

| Family Support | −0.025 | −0.026 | −0.024 | −0.023 | ||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.135 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | −0.166 | |||||||

| Friends Support | 0.033 | 0.033 | 0.035 | 0.032 | ||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.249* | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | −0.246 | |||||||

| W1 Psychological Health Status | 0.070*** | 0.070*** | 0.070*** | 0.070*** | 0.070*** | 0.070*** | 0.070*** | 0.070*** |

| Constant | 1.291*** | 1.290*** | 1.299*** | 1.301*** | 1.448*** | 1.447*** | 1.445*** | 1.463*** |

| Minimum Number of Observations | 12881 | 12881 | 12881 | 12881 | 12879 | 12879 | 12879 | 12879 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01

p<0.001, two-tailed test

Note: Results are based on multiply imputed data. All models control for gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and age. Social support measures include those who reported no spouse, family, or friends.

Table 3.

Negative Binomial Regression Predicting Log Felt Loneliness Score

| NSHAP Felt Loneliness Measure (0–6) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Verbal Mistreatment (vs. None) | ||||||||

| Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | 0.182** | 0.199 | −0.046 | 0.359 | 0.185** | 0.162 | 0.259 | 0.205 |

| Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.082 | −0.230 | −0.296 | 0.042 | 0.090 | −0.204 | −0.378 | −0.679* |

| W1 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | 0.034 | 0.023 | 0.035 | 0.035 | 0.076** | 0.074** | 0.076** | 0.076** |

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.015 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.168* | |||||||

| Family Support | −0.151** | −0.154** | −0.172** | −0.150** | −0.106* | −0.110* | −0.109* | −0.112* |

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | 0.095 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.158 | |||||||

| Friends Support | −0.047 | −0.045 | −0.046 | −0.040 | −0.008 | −0.003 | −0.004 | 0.000 |

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.084 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.019 | |||||||

| W2 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | −0.226*** | −0.241*** | −0.226*** | −0.226*** | ||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | 0.015 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.179* | |||||||

| Family Support | −0.107** | −0.108** | −0.119** | −0.108** | ||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.031 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.191 | |||||||

| Friends Support | −0.085+ | −0.089+ | −0.087 | −0.118* | ||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.010 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.357* | |||||||

| W1 Psychological Health Status | 0.241*** | 0.244*** | 0.242*** | 0.240*** | 0.234*** | 0.236*** | 0.235*** | 0.234*** |

| Constant | −0.203 | −0.217 | −0.156 | −0.218 | 0.658 | 0.652 | 0.686* | 0.701* |

| Minimum Number of Observations | 12768 | 12768 | 12768 | 12768 | 12766 | 12766 | 12766 | 12766 |

| Financial Mistreatment (vs. None) | ||||||||

| Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.166 | 0.337** | −0.231 | 0.080 | 0.146 | 0.271* | −1.029 | 0.028 |

| Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.076 | 0.134 | −0.846 | −0.004 | 0.043 | 0.516* | −1.042 | 0.346 |

| W1 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | 0.034 | 0.040 | 0.030 | 0.034 | 0.075** | 0.072** | 0.075** | 0.076** |

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.131 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | −0.027 | |||||||

| Family Support | −0.150** | −0.151** | −0.168** | −0.150** | −0.106+ | −0.115* | −0.105 | −0.106 |

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.171 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.385 | |||||||

| Friends Support | −0.049 | −0.049 | −0.050 | −0.051 | −0.010 | −0.012 | −0.010 | −0.010 |

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.040 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.036 | |||||||

| W2 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | −0.223*** | −0.212*** | −0.223*** | −0.224*** | ||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.095 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | −0.322** | |||||||

| Family Support | −0.106** | −0.105** | −0.134** | −0.105** | ||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.492* | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.454 | |||||||

| Friends Support | −0.083+ | −0.082+ | −0.088 | −0.082 | ||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.057 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | −0.143 | |||||||

| W1 Psychological Health Status | 0.246*** | 0.245*** | 0.246*** | 0.246*** | 0.239*** | 0.240*** | 0.240*** | 0.239*** |

| Constant | −0.181 | −0.193 | −0.119 | −0.173 | 0.680 | 0.677 | 0.764* | 0.680 |

| Minimum Number of Observations | 12775 | 12775 | 12775 | 12775 | 12773 | 12773 | 12773 | 12773 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001, two-tailed test

Note: Results are based on multiply imputed data. All models control for gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and age. Social support measures include those who reported no spouse, family, or friends.

The results for anxiety symptoms appear in Table 2. Model 1 in the top panel shows that experiencing verbal mistreatment in W1 results in higher NASM scores five years later, net of demographic characteristics, W1 social support, and W1 anxiety symptoms. Those verbally mistreated by kin score exp(0.107)=1.11 times the number of points on the anxiety symptoms scale as non-victims. Those verbally mistreated by others score exp(0.131)=1.14 times the number of points on the anxiety symptoms scale. As expected, the coefficients on the W1 social support measures are negative, indicating a direct protective effect of social support on later anxiety, but not all of them reach statistical significance. Family support has a marginally significant negative effect on W2 anxiety symptoms (β=−0.052, p=0.085), and support from friends has a statistically significant negative effect on W2 anxiety (β=−0.062, p=0.024). Surprisingly, spousal support at W1 is unrelated to emotional well-being at W2. In Models 2–4, we interact verbal mistreatment with each measure of social support at W1. None of the interaction coefficients is statistically significant, and the magnitudes of these interaction effects are close to zero, suggesting no buffering effect of W1 social support. In short, W1 verbal mistreatment and W1 social support have direct effects on later anxiety, but they do not interact.

When we include W2 social support in Model 5, the direct effect of verbal mistreatment on later anxiety persists. In fact, there is little change in the magnitudes of the coefficients. Those verbally mistreated by kin continue to score exp(0.107)=1.11 times the number of points on the anxiety symptoms scale as non-victims, and those mistreated by others continue to score exp(0.129)=1.14 times the number of points. Among the W2 social support measures, only W2 spousal support is associated with decreases in NASM scores (β=−0.069, p=0.010). The interactions between verbal mistreatment and W2 measures of social support in Models 6–8 are mostly statistically insignificant, providing little evidence of a buffering effect of social support on mistreatment. Taken together, W1 verbal mistreatment predicts greater W2 anxiety symptoms scores, and social support neither reduces nor buffers its effects2.

Table 3 shows the results from analyses predicting felt loneliness (NFLM) scores. Model 1 of the top panel shows that verbal mistreatment by kin increases later loneliness – mistreatment victims score exp(0.182)=1.20 times the number of points on the loneliness symptoms scale as those who were not mistreated. Social support from family at W1 is associated with decreased W2 NLFM scores (β=−0.151, p=0.004), but support from spouses and friends in W1 is unrelated to later loneliness. The interaction terms in Models 2–4 are mostly non-significant, so we have little evidence for a buffering effect. However, there is a counterintuitive significant interaction between W1 spousal support and verbal mistreatment: those with higher W1 spousal support who were verbally mistreated by non-kin report more loneliness at W2 compared to those who were mistreated but report no spousal support (β1+β2=−0.230+0.168=−0.62). It is possible that later loneliness scores are higher for those with more spousal support at the time of mistreatment because those with more support might expect to be protected against mistreatment and were not, leading to greater feelings of loneliness.

In Model 5, we add controls for W2 social support. The W2 social support measures are all negative in direction and mostly statistically significant (support from friends is marginally significant), showing the expected beneficial effect of current support on current loneliness, but the detrimental effect of verbal mistreatment by kin persists. The interactions between current social support and past mistreatment in Models 6–8 suggest that those mistreated by others who now have more support from spouses (β=0.179, p=0.036), and more support from friends (β=0.357, p=0.015) score higher on loneliness symptoms than those mistreated by others who do not have social support. Again, this finding could indicate that those with more support might have expected to be protected against mistreatment and were not, and now report greater feelings of loneliness. In summary, past verbal mistreatment increases later loneliness, current social support decreases it, and their interaction produces a complex buffering effect.

Model 1 of Panel 2 shows that financial mistreatment has no direct effects on later loneliness. However, Model 2 shows a suppression effect. After interacting financial mistreatment by kin with spousal support, the direct effect of financial mistreatment becomes statistically significant. Those financially mistreated by kin who have no spousal support score (exp(0.337)=1.40 times the number of points on the loneliness symptoms scale in W2. The interaction of spousal support at W1 and financial mistreatment is negative (β=−0.131) and approaches statistical significance (p=0.089), hinting at an additive buffering effect (Wheaton 1985) – experiencing mistreatment mobilizes spousal support.

In Model 5, we see no direct effects of financial mistreatment on later loneliness, but the W2 spousal and family support show statistically significant negative effects on W2 loneliness. After introducing interaction effects in Model 6, the direct effects of financial mistreatment become significant: those mistreated by kin who have no spousal support score exp(0.271)=1.31 times the number of points on the loneliness scale, while those mistreated by others and have no spousal support score exp(0.516)=1.68 times the number of points. There is also a statistically significant interaction between financial mistreatment by others and spousal support in W2 (β=−0.322, p=0.004), indicating a buffering effect of later spousal support. In Model 7, we see an unexpected buffering effect of family support on financial mistreatment by kin. Those mistreated by kin who now have more support from family score higher on loneliness symptoms (β=0.492, p=0.019). This pattern might indicate that the mistreated withdrew or were isolated from the abusive family member, and now are supported by other kin. But they report more loneliness because they no longer have contact with the abuser.

Physical Health

Tables 4 and 5 show the results for regressions predicting comorbidity index (NCI) score, and number of difficulties with activities of daily living (ADLs), respectively. Generally, verbal mistreatment predicts a greater burden of chronic conditions, and both verbal and financial mistreatment predict more difficulties with ADLs.

Table 4.

Poisson Regression Predicting Comorbidity Index Score

| NSHAP Comorbidity Index (0–21) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Verbal Mistreatment (vs. None) | ||||||||

| Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | 0.112* | 0.090 | 0.166 | 0.107 | 0.113* | 0.173 | 0.130 | 0.097 |

| Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.078 | 0.052 | 0.008 | 0.391** | 0.078 | 0.109 | 0.140 | −0.020 |

| W1 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | 0.013 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.014 | |||||||

| Family Support | 0.025 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.026 | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.012 |

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.022 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.029 | |||||||

| Friends Support | −0.056* | −0.056* | −0.056* | −0.049 | −0.059* | −0.060* | −0.060* | −0.059* |

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | 0.002 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | −0.148* | |||||||

| W2 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | −0.011 | −0.006 | −0.011 | −0.011 | ||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.039 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | −0.019 | |||||||

| Family Support | 0.034 | 0.034 | 0.036 | 0.034 | ||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.007 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | −0.025 | |||||||

| Friends Support | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.005 | −0.001 | ||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | 0.008 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.045 | |||||||

| W1 Physical Health Status | 0.208*** | 0.208*** | 0.208*** | 0.208*** | 0.208*** | 0.208*** | 0.208*** | 0.207*** |

| Constant | −0.135 | −0.130 | −0.133 | −0.155 | −0.174 | −0.188 | −0.180 | −0.163 |

| Minimum Number of Observations | 13394 | 13394 | 13394 | 13394 | 13390 | 13390 | 13390 | 13390 |

| Financial Mistreatment (vs. None) | ||||||||

| Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.067 | 0.001 | 0.124 | 0.170 | 0.067 | 0.073 | 0.220 | 0.055 |

| Financial Mistreatment by Others | −0.084 | −0.217 | −0.136 | −0.394 | −0.081 | −0.294 | −0.170 | −0.082 |

| W1 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | 0.001 | −0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.043 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.063 | |||||||

| Family Support | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.011 |

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.025 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.022 | |||||||

| Friends Support | −0.056* | −0.056* | −0.056* | −0.056* | −0.059* | −0.059* | −0.059* | −0.059* |

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.049 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.141 | |||||||

| W2 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | −0.010 | −0.013 | −0.010 | −0.010 | ||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.005 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.113 | |||||||

| Family Support | 0.033 | 0.033 | 0.034 | 0.033 | ||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.065 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.038 | |||||||

| Friends Support | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.004 | ||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.006 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.000 | |||||||

| W1 Physical Health Status | 0.209*** | 0.209*** | 0.209*** | 0.209*** | 0.209*** | 0.209*** | 0.209*** | 0.209*** |

| Constant | −0.072 | −0.067 | −0.073 | −0.069 | −0.113 | −0.114 | −0.116 | −0.112 |

| Minimum Number of Observations | 13405 | 13405 | 13405 | 13405 | 13401 | 13401 | 13401 | 13401 |

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001, two-tailed test

Note: Results are based on multiply imputed data. All models control for gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and age. Social support measures include those who reported no spouse, family, or friends.

Table 5.

Physical Health Outcomes: Negative Binomial Regression Predicting Difficulty with ADLs Score

| Difficulty with ADLs (0–5) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 4 | Model 8 | |

| Verbal Mistreatment (vs. None) | ||||||||

| Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | 0.010 | 0.138 | 0.234 | 1.197* | 0.012 | 0.226 | −0.751 | −0.013 |

| Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.448** | 0.307 | 1.841* | 0.989+ | 0.436** | 0.343 | −0.630 | −0.131 |

| W1 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | −0.003 | −0.003 | −0.005 | −0.006 | 0.019 | 0.018 | 0.023 | 0.020 |

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.073 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.072 | |||||||

| Family Support | −0.081 | −0.083 | 0.001 | −0.071 | −0.095 | −0.093 | −0.103 | −0.105 |

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.090 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | −0.589* | |||||||

| Friends Support | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.076 | 0.026 | 0.029 | 0.029 | 0.031 |

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.575* | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | −0.257 | |||||||

| W2 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | −0.161 | −0.155 | −0.161 | −0.155 | ||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | −0.143 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.053 | |||||||

| Family Support | 0.072 | 0.076 | 0.021 | 0.072 | ||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | 0.307 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.421 | |||||||

| Friends Support | −0.049 | −0.047 | −0.062 | −0.078 | ||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Kin | 0.011 | |||||||

| X Verbal Mistreatment by Others | 0.256 | |||||||

| W1 Physical Health Status | 0.695*** | 0.693*** | 0.703*** | 0.694*** | 0.686*** | 0.684*** | 0.685*** | 0.681*** |

| Constant | −2.315** | −2.341** | −2.558*** | −2.489** | −1.974* | −2.029* | −1.832* | −1.928* |

| Minimum Number of Observations | 13350 | 13350 | 13350 | 13350 | 13346 | 13346 | 13346 | 13346 |

| Financial Mistreatment (vs. None) | ||||||||

| Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.712* | 0.886* | 2.228 | 0.736 | 0.712* | 0.925* | 0.880 | −0.288 |

| Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.944* | 0.603 | 1.281 | 0.435 | 0.945* | 0.443 | −0.802 | −0.662 |

| W1 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.008 | −0.002 | 0.023 | 0.029 | 0.020 | 0.018 |

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.119 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.157 | |||||||

| Family Support | −0.059 | −0.058 | −0.025 | −0.062 | −0.081 | −0.074 | −0.087 | −0.085 |

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.680 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | −0.138 | |||||||

| Friends Support | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.005 | −0.004 | 0.008 | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.001 |

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.011 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.227 | |||||||

| W2 Social Support | ||||||||

| Spousal Support | −0.163 | −0.167 | −0.160 | −0.156 | ||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.164 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.261 | |||||||

| Family Support | 0.102 | 0.098 | 0.087 | 0.094 | ||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | −0.076 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.697 | |||||||

| Friends Support | −0.050 | −0.053 | −0.053 | −0.080 | ||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Kin | 0.476 | |||||||

| X Financial Mistreatment by Others | 0.697* | |||||||

| W1 Physical Health Status | 0.716*** | 0.716*** | 0.715*** | 0.715*** | 0.706*** | 0.708*** | 0.706*** | 0.709*** |

| Constant | −2.476*** | −2.501*** | −2.653*** | −2.451*** | −2.183** | −2.209** | −2.083* | −2.082* |

| Minimum Number of Observations | 13361 | 13361 | 13361 | 13361 | 13357 | 13357 | 13357 | 13357 |

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001, two-tailed test

Note: Results are based on multiply imputed data. All models control for gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and age. Social support measures include those who reported no spouse, family, or friends.

Model 1 in the first panel of Table 4 shows that verbal mistreatment by kin increases later chronic conditions after controlling for comorbidity and social support at baseline. This model also shows that only W1 support from friends has a beneficial direct effect on W2 NCI score. Models 2 and 3 show non-significant interaction effects, indicating that support from spouses and family do not buffer against verbal mistreatment. In Model 4, though, there is a buffering effect of support from friends at W1 (β=−0.148): compared to those who had no support from friends and experienced verbal mistreatment by non-kin, those who were mistreated but had more concurrent support from friends report a lower burden of chronic conditions later on. Additionally, the effect of verbal mistreatment by others among those without support from friends becomes statistically significant, increasing comorbidity scores exp(0.391)=1.48 times compared to those who did not report mistreatment. Model 5 continues to show a positive association between verbal mistreatment by kin and later NCI score, but shows few direct effects of W2 social support. The interaction effects in Models 6–8 are also statistically insignificant, providing no evidence of a buffering effect of later social support on W2 physical health. In short, verbal mistreatment increases the burden of chronic conditions, and social support has neither direct effects on comorbidity, nor buffering effects against verbal mistreatment. Although we find an effect of verbal mistreatment on later chronic conditions, we find no association between financial mistreatment and W2 NCI scores.

The results in Model 1 in the top panel of Table 5 show that experiencing verbal mistreatment by non-kin increases difficulties with ADLs. Mistreatment victims report exp(0.448)=1.57 times the number of difficulties with ADLs in W2 as non-victims, even after controlling for other W1 factors. W1 social support, however, has no direct effects on later difficulties with ADLs. Model 3 shows a statistically significant interaction between verbal mistreatment by others and W1 support from family (β=−0.589, p=0.049): although those who were verbally mistreated by others and have no support from family report more difficulties with ADLs, those who do report family support are buffered from mistreatment’s negative effects . In Model 4, the direct effect of verbal mistreatment by kin among those with no support from friends becomes large and statistically significant. Those mistreated by kin and who have no support from friends report exp(1.197)=3.31 times the number of difficulties with ADLs as others. However, the effect is buffered if the mistreated receive support from friends (β=−0.575, p=0.027). Model 5 shows a direct effect of verbal mistreatment by non-kin, but the direct effects of social support are non-significant. The interactions in Models 6–8 are also statistically insignificant. That is, verbal mistreatment worsens functional health, and though social support does not directly improve health, it shows some buffering effects.

Results in the second panel show that financial mistreatment is associated with a decline in physical functioning even after controlling for baseline factors. Model 1 shows that, net of W1 control variables, financial mistreatment by kin increases the number of difficulties with ADLs exp(0.712)=2.04 times compared to non-victims, and financial mistreatment by non-kin increases the count of difficulties with ADLs exp(0.944)=2.57 times. In other words, those who were financially mistreated have more than twice the number of difficulties with ADLs as those who were not mistreated. None of the other models show any direct effects of W1 or W2 social support on later difficulties with ADLs, and none of the interaction effects reach statistical significance, showing little evidence of any buffering effects of support on financial mistreatment. In sum, social support does not improve functional health, but financial mistreatment does damage it. To our knowledge, this is the first study to document a relationship between financial mistreatment and declining functional health.

Discussion

This study uses stress process theory (Pearlin, 1989; Pearlin et al., 1981; Pearlin et al., 2005) to develop an understanding of elder mistreatment, social support, and physical and psychological health outcomes. Extending previous work, we use longitudinal data from the National Social Life Health and Aging Project to verify the temporal ordering of these relationships.

In support of our first hypothesis, we find that those who report elder mistreatment are more likely than those who do not to show declines in psychological and physical health over the following five years. Overall, these findings suggest that the negative impact of elder abuse is long-lasting and persistent in shaping health at older ages. Verbal mistreatment is related to declines in both psychological health (greater anxiety and loneliness symptoms) and physical health (greater burden of chronic conditions and more difficulties with ADLs) five years later. This finding aligns with previous research (e.g., Cisler et al., 2012; Comijs et al., 1999; Luo &, Waite 2011; Mouton, 2003; Plichta, 2004; Spertus et al., 2003), and highlights the particularly damaging nature of psychological abuse.

Financial mistreatment also predicts declines in psychological (loneliness symptoms) and physical health (chronic conditions and difficulties with ADLs), but has more complex relationships with these outcomes. For example, financial mistreatment only affects later loneliness if we account for a suppression effect. Then we find that financial mistreatment increases later loneliness, and those with more support from spouses and family were buffered against its effect. The relationships between financial mistreatment, social support, and health are consistent with Wheaton’s (1985) model for additive buffering. Financial mistreatment might mobilize social resources so that the direct effects of financial mistreatment are smaller than they would have been had the social support not been available.

We also find a novel association between financial mistreatment and poorer functional health five years later. To our knowledge, this is the first study that empirically documents a relationship between the experience of financial mistreatment and later physical vulnerability. Respondents who report financial mistreatment in W1 report a greater number of difficulties with ADLs in W2. Previous research finds that greater levels of income and assets are related to better physical function as well as slower rates of physical decline (Kim & Richardson, 2012), so it is possible that financial mistreatment leads to functional limitations because depriving elderly individuals of financial resources compromises their ability to pay for and access other resources needed to maintain their physical health. As functional health declines, many older adults are able to maintain their independence through use of assistive devices, modifications to their dwelling, help from others, or therapies. Loss of financial resources may decrease access to these coping strategies (Mathieson, Kronenfeld, & Keith, 2002). It is also possible that financial abuse leads to pessimism about the ability to respond to declines in physical functioning, thus reducing efforts to cope with functional limitations (Thoits, 2006; 2010). While the pathway through which financial mistreatment increases functional impairments is unclear, we conclude that financial abuse compromises physical well-being and likely reduces the possibility of independent living in late life.

Though the stress process model posits that social support buffers against negative life events (Pearlin, 1989; Pearlin et al., 1981), we found limited support for our second hypothesis that social support at both times moderates and reduces the effect of elder mistreatment at W1 on psychological and physical health at W2. Support buffers verbal mistreatment victims against worsening functional health, but we found little evidence of this kind of buffering in other situations. In fact, the interaction of mistreatment and social support predicted greater feelings of loneliness, perhaps suggesting that those with support did not expect to be mistreated, so when they were, they felt even more isolated than those with little social support who were mistreated.

Conclusions and Limitations

Taken together, we conclude that presence or lack of social support does not account for the relationship between elder mistreatment and later health outcomes. We speculate that social support may not always protect victims of abuse from declines in well-being if the usual sources of support are also the sources of stress. Because elder mistreatment is, by definition, perpetrated by trusted others, social support from these sources may not counter the negative behaviors of these same actors. We suggest that future studies of victimization specify the sources of abuse and the sources of support, because if the providers of support are also the sources of stress, the positive effects of their support may not cancel out the negative effects of their abuse. However, abuse victims may seek social resources from others. Elders who are mistreated by trusted others might find support from other relatives or persons in the community with whom they interact, like doctors or social workers.

Although the small number of elders who reported mistreatment in some categories may contribute to these inconsistent interaction effects, our overall findings suggest that interventions that advocate increasing social support for elder mistreatment victims may not have the expected effect unless they identify appropriate sources of support. Therefore, we recommend policymakers and social workers to work toward preventing elder abuse and mistreatment, and suggest increasing services that treat the psychological and physical symptoms of mistreatment.

There were several other limitations in our study. First, our findings are limited by the broad and general nature of the elder mistreatment questions in NSHAP. Because the mistreatment questions do not use specific, behaviorally defined descriptions of interpersonal violence events, these items may produce over-estimations of its prevalence. For example, anyone who has been insulted or put down, even once, during the past 12 months regardless of context would be identified as a victim of verbal mistreatment according to the verbal mistreatment item in NSHAP. But, because these questions were adapted from the well-validated Hwalek-Sengstock Elder Abuse Screening Test (Hwalek & Sengstock, 1986) and the Vulnerability to Abuse Screening Scale (Schofield & Mishra; 2003), we have confidence that the elder mistreatment items appropriately identified mistreatment victims. We further accounted for the possibility of increased prevalence of mistreatment in NSHAP by doing sensitivity analyses. Results were similar regardless of how we classified mistreatment victims. Until the field reaches a consensus on what counts as “intentional actions that cause harm or create a serious risk of harm, whether or not intended, to a vulnerable elder by a caregiver or other person who stands in a trust relationship to the elder,” or “failure by a caregiver to satisfy the elder’s basic needs or to protect the elder from harm” (Bonnie & Wallace 2003), we favor over-identification of this stressor to under-identification.

Second, because NSHAP did not include measures of mistreatment in W2, we were unable to account for any mistreatment that might be occurring at the time. Yet, the causal direction of W2 mistreatment on W2 health is unclear, as some research points to cognitive and physical decline as risk factors for abuse (Laumann et al., 2008). Future research should test the extent to which mistreatment and vulnerability are reciprocal.

Our results provide the strongest evidence to date on the effects of mistreatment of older adults on their later psychological and physical health. These findings tell us about the mechanisms - psychological health and physical functioning - by which mistreatment may increase risks for mortality (e.g., Dong et al., 2011). They also tell us about how the social context in which in which mistreatment takes place might matter. Our findings help lay the groundwork for the design of treatments and interventions to reduce the negative consequences of mistreatment for emotional and physical health, should it occur.

Footnotes

One-hundred fifty-one respondents (6.68%) were missing information on the verbal mistreatment question, and 140 respondents (6.19%) were missing information on the financial mistreatment question. Five-hundred twenty-two (23.09%) respondents were missing some information on the W2 anxiety measure, 461 (20.39%) were missing some information on the W2 loneliness measure, one respondent was missing information on the W2 ADL measure, and 273 (12.07%) were missing some information on the W2 chronic conditions measure.

Analyses of the depressive symptoms scale produce a similar pattern of findings: W1 verbal mistreatment, but not W1 financial mistreatment, predicts higher W2 depressive symptoms scores. The social support coefficients are negative in direction, but there were no statistically significant buffering effects.

Contributor Information

Jaclyn S. Wong, Department of Sociology, University of Chicago

Linda J. Waite, Department of Sociology, University of Chicago

References

- Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Steve K, Muzzy W, Kilpatrick DG. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The national elder mistreatment study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:292–297. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter AB, Begle AM, Cisler JM, Hernandez MA, Muzzy W, Acierno R. Prevalence and correlates of poor self-rated health in the United States: The national elder mistreatment study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;18:615–623. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ca7ef2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Smith J. New frontiers in the future of aging: From successful aging of the young old to the dilemmas of the fourth age. Gerontology. 2003;49:123–135. doi: 10.1159/000067946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnie RJ, Wallace RB, editors. Elder Mistreatment: Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation in an Aging America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, Mayer J. Elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation: Risk factors and prevention strategies. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2000;33:5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cisler JM, Begle AM, Amstadter AB, Acierno R. Mistreatment and self-reported emotional symptoms: Results from the national elder mistreatment study. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect. 2012;24:216–230. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2011.652923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comijs HC, Penninx BWJH, Knipscheer KPM, van Tilburg W. Psychological distress in victims of elder mistreatment: the effects of social support and coping. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1999;54B:P240–P245. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.4.p240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KJ, Iris M, Ridings JW, Fairman KP, Rosen A, Wilber KH. Conceptual model and map of financial exploitation of older adults. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. 2011;23:304–325. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2011.584045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Selwood A, Livingston G. The prevalence of elder abuse and neglect: A systematic review. Age and Ageing. 2008;37:151–160. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong XQ. Medical implications of elder abuse and neglect. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2005;21:293–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Simon M, Mendes de Leon C, Fulmer T, Beck T, Hebert L, Evans D. Elder self-neglect and abuse and mortality risk in a community-dwelling population. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302:517–526. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Simon MA, Beck TT, Farran C, McCann JJ, Mendes de Leon CF, Evans DA. Elder abuse and mortality: The role of psychological and social wellbeing. Gerontology. 2011;57:549–558. doi: 10.1159/000321881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Chen R, Chang ES, Simon M. Elder abuse and psychological well-being: A systematic review and implications for research and policy - A mini review. Gerontology. 2012;59:132–142. doi: 10.1159/000341652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafemeister TL. Financial exploitation in domestic situations. In: Bonnie RJ, Wallace RB, editors. Elder Mistreatment: Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation in an Aging America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. pp. 382–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2001;50:337–421. [Google Scholar]

- Hwalek M, Sengstock MC. Assessing the probability of abuse of the elderly: Toward the development of a clinical screening instrument. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 1986;5:153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Richardson V. The impact of socioeconomic inequality and lack of health insurance on physical functioning among middle-aged and older adults in the United States. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2012;20:42–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Pillemer KA, Charlson ME. The mortality of elder mistreatment. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:428–432. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.5.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Leitsch SA, Waite LJ. Elder mistreatment in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a nationally representative sample. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2008;63B:S248–S254. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.4.s248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JS. Regression models for categorical limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Waite LJ. Mistreatment and psychological well-being among older adults: Exploring the role of psychosocial resources and deficits. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2011;66B:217–229. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson K, Kronenfeld JJ, Keith VM. Maintaining functional independence in elderly adults: The roles of health status and financial resources in predicting home modifications and use of mobility equipment. The Gerontologist. 2002;42:24–31. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton CP. Intimate partner violence and health status among older women. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:1465–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Nishishiba M, Morgan DL, Rook KS. The relative importance of three domains of positive and negative social exchanges: A longitudinal model with comparable measures. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:746–754. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Muircheartaigh C, Eckman S, Smith S. Statistical design and estimation for the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2009;64B doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Muircheartaigh C, English N, Pedlow S, Kwok PK. Sample design, sample augmentation, and estimation for Wave II of the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP) Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2014;69:S15–S26. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne C, Hedburg E, Kozloski MJ, Dale W, McClintock M. Using and interpreting mental health measures from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2014;69:S99–S116. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI. The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30:241–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Menaghan E, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT. The Stress Process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:337–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Nguyen KB, Schieman S, Milkie MA. The life-course origins of mastery among older people. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48:164–179. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersman SC. Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:205–219. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plichta SB. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:1296–1323. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner DJ, O’Keefe J, Brown D. A conceptual framework of financial exploitation of older persons. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect. 2004;16:53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA loneliness scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39:472–480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield MJ, Mishra GD. Validity of self-report screening scale for elder abuse: Women’s Health Australia Study. The Gerontologist. 2003;43:110–120. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield MJ, Powers JR, Loxton D. Mortality and disability outcomes of self-reported elder abuse: A 12-year prospective investigation. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61:679–685. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiovitz-Ezra S, Leitsch S, Graber J, Karraker A. Quality of life and psychological health indicators in the national social life, health, and aging project. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2009;64B doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spertus IL, Yehuda R, Wong CM, Halligan S, Seremetis SV. Childhood emotional abuse and neglect as predictors of psychological and physical symptoms in women presenting to a primary care practice. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:1247–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Personal agency in the stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47:309–323. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. An aging nation: The older population in the United States. (Current Population Reports, P25–1140) Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilopoulos T, Kotwal A, Huisingh-Scheetz MJ, Waite LJ, McClintock MK, Dale W. Comorbidity and chronic conditions in the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP), Wave 2. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2014;69:S154–S165. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Laumann EO, Levinson W, Lindau ST, O’Muircheartaigh CA. ICPSR20541-v6. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP): Wave 1. 2014-04-30. [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Cagney K, Dale W, Huang E, Laumann EO, McClintock M, Cornwell B. ICPSR34921-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP): Wave 2 and Partner Data Collection. 2014-04-29. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B. Models for the stress-buffering functions of coping resources. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1985;26:352–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf Rosalie S. Elder Abuse and Neglect: Causes and Consequences. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1997;30:153–174. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf R. Introduction: The nature and scope of elder abuse. Generations. 2000;24:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]