Abstract

Purpose

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) content is present on social media and may influence adolescents. Instagram is a popular site among adolescents in which NSSI-related terms are user-generated as hashtags (words preceded by a #). These hashtags may be ambiguous and thus challenging for those outside the NSSI community to understand. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the meaning, popularity, and content advisory warnings related to ambiguous NSSI hashtags on Instagram.

Methods

This study used the search term “#selfharmmm” to identify public Instagram posts. Hashtag terms co-listed with #selfharmmm on each post were evaluated for inclusion criteria; selected hashtags were then assessed using a structured evaluation for meaning and consistency. We also investigated the total number of Instagram search hits for each hashtag at two time points and determined whether the hashtag prompted a Content Advisory warning.

Results

Our sample of 201 Instagram posts led to identification of 10 ambiguous NSSI hashtags. NSSI terms included #blithe, #cat, and #selfinjuryy. We discovered a popular image that described the broader community of NSSI and mental illness, called “#MySecretFamily.” The term #MySe-cretFamily had approximately 900,000 search results at Time 1 and >1.5 million at Time 2. Only one-third of the relevant hashtags generated Content Advisory warnings.

Conclusions

NSSI content is popular on Instagram and often veiled by ambiguous hashtags. Content Advisory warnings were not reliable; thus, parents and providers remain the cornerstone of prompting discussions about NSSI content on social media and providing resources for teens.

Keywords: Adolescent health, Online safety, Instagram, Social media, Mental health, Self-harm, Nonsuicidal self-harm, Content analysis

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is defined as the deliberate destruction of one's body tissue in the absence of conscious suicidal intent [1]. NSSI is also known as self-harm or self-injury and includes behaviors such as cutting, burning, and scratching [2]. Estimates of NSSI prevalence among adolescents typically range from 7% to 24% [3,4]; initiation is typically during middle school [5,6]. Rates of NSSI are higher among adolescents who have experienced childhood maltreatment [7] and among females, although some studies find equal rates across gender [5]. NSSI is associated with comorbid psychiatric illnesses such as depression and serious consequences such as suicide [2,8].

Exposure to peer NSSI may increase the risks of engaging in these behaviors via social contagion or normalization of these behaviors [2,9]. Social contagion can occur both offline and online; previous studies have illustrated NSSI content in online forums and on social media such as YouTube [2,10,11]. In one study, online NSSI content was a trigger for offline NSSI behaviors [12]. NSSI on social media is of particular interest given that social media content is typically peer generated and thus combines the influence of peers and media [13]. Social media also allow users to create online identities that may reflect their existing identity or a newly developing identity. Social media users can thus gain exposure to other users' online identities and posted content and build online communities around shared interests [13].

Recently, the social media site Instagram has received media attention regarding concerns about NSSI content [14,15]. Instagram is a photograph sharing site wherein information is shared by uploading a photograph labeled with a caption and with one or more hashtags. Hashtags are words or phrases without spaces between that are preceded by a # and are used on other social media sites such as Twitter. Hashtags allow content to be linked to larger online communities who also use the hashtag. Instagram also allows for individual anonymity by choosing a username, in contrast to some social media platforms such as Facebook where the terms of use specify that real names must be used. On Instagram, a user could maintain one account using their real name and a second NSSI-related account using a different username. Maintaining two Instagram accounts may allow a teen to feel that they can develop or maintain a separate “anonymous” NSSI-related identity. Content on Instagram is typically highly visual, public, personal, and easily accessed on any Internet accessible device. The visual nature of this site allows NSSI behaviors such as cutting to be viewed clearly and potentially imitated. Because most Instagram users are high school–age adolescents [16], and this site is currently considered a popular and “prestigious” social media site for this age group [17], the potential creators and consumers of NSSI-related content on this site are likely adolescents.

Instagram's terms of use discourage NSSI displays and describe that they will place warnings about dangerous content [18]. However, Instagram has come under media scrutiny for the presence of harmful material including content promoting eating disorders [15]. The hashtag #selfharm was previously used to build an Instagram community dedicated to NSSI [14]. After that, hashtag was reported to Instagram, the site blocked users from searching for content linked to that hashtag. The revised hashtag #selfharmm then emerged and was used in this same community. At present, this second hashtag has been blocked, and the term #selfharmmm is now a popular hashtag. Parents, educators, and clinicians may struggle to understand how to interpret hashtags and social media displays. Layperson media, such as blogs, report well meaning but nonempiric and often inaccurate interpretations of common NSSI terms [19].

The purpose of this study was to investigate ambiguous NSSI-related terms on Instagram including evaluation of meaning and consistency. Our goals were to (1) present current data on ambiguous hashtags that may be common parlance related to NSSI; (2) test a process to investigate ambiguous NSSI terms; (3) evaluate the popularity of NSSI-related hashtags at two time points; and (4) assess the precision of Instagram's warning labels for concerning content, by testing whether NSSI terms triggered Instagram's “Content Advisory” warning.

Methods

This study took place on the social media site Instagram (www.instagram.com). Using a commonly used NSSI hashtag of #selfharmmm as a search term, we identified a sample of content posted on Instagram between the dates of June 18, 2014 and June 30, 2014 for evaluation. From this sample, we identified and investigated a list of ambiguous hashtags that were potentially linked to NSSI. We investigated that these selected hashtags to determine meaning and consistency using a structured approach including triangulation of data. Triangulation of data is a critical concept in qualitative research described as using more than one approach to collect or evaluate data [20–22]. The triangulation approach is designed to enhance validity and minimize the risk that conclusions reflect only the biases or limitations of a single approach.

This study was determined to be exempt from Human Subjects Review by the Seattle Children's Institutional Review Board with the provision that no identifying information regarding potential minors was reported.

Search criteria: Identifying nonsuicidal self-injury posts on Instagram

Every photograph uploaded to Instagram, typically called a “post,” includes a caption and can be labeled with one or more hashtags. The main way to search on Instagram is by using a hashtag; searching for a particular hashtag allows one to access the community of public users who have labeled photographs with that hashtag. For this study, we used the search term “#self-harmmm” as it was among the most common NSSI search terms on Instagram that evolved from the initial term #selfharm [14].

Using the search term #selfharmmm, we assessed search results to identify a goal sample size of 200 publicly available relevant posts. This number was selected based on previous descriptive studies on social media suggesting that 200 posts allow for appropriate breadth of evaluation and saturation of themes in content analysis [23–25]. We selected a sample of 225 posts to evaluate for eligibility based on estimates of approximately 10% of posts being excluded after our pilot evaluations. We evaluated publicly available posts as we were interested in what NSSI content was available to the general public of adolescent Instagram users. We excluded non-English posts. Based on Institutional Review Board (IRB) restrictions, we excluded posts from users who specifically reported age less than 18 years. The focus of evaluation for this study was hashtags represented within Instagram posts; thus, demographic information about the profile owners was not recorded.

Selection of nonsuicidal self-injury–related hashtags for evaluation

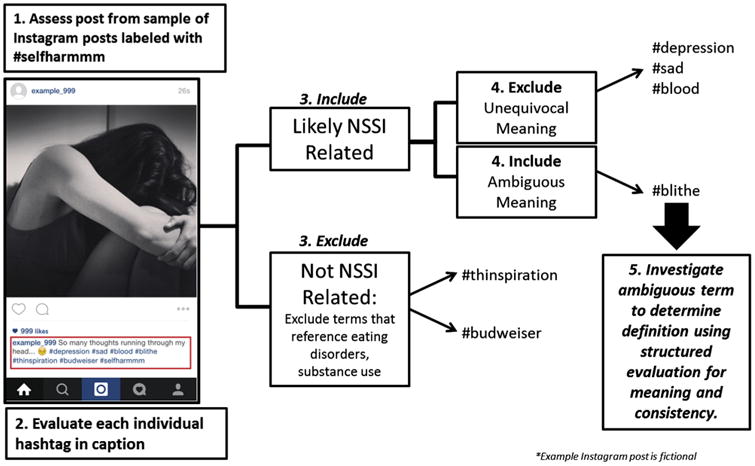

For each post that met inclusion criteria, we examined the post and assessed all hashtags to select ambiguous potential NSSI-related hashtags for our structured evaluation process. We focused our study on NSSI as an understudied area of social media research; thus, we excluded hashtags related to eating disorders (e.g., #thinspo and #proana) or substance use (e.g., #legalizeit and #bupe) for two reasons. First, previous studies have examined social media content related to eating disorders [26,27] and substance use [28–33]. Second, in contrast to ambiguous NSSI terms, there are other resources (i.e., www.urbandictionary.com) available to assist with understanding ambiguous eating disorder and substance use terms. Hashtags with obvious meaning that would not require further evaluation, such as #depression, were also excluded. Figure 1 illustrates this selection process.

Figure 1.

Selection process to identify ambiguous NSSI hashtags on Instagram.

Development of the structured evaluation approach

The structured evaluation approach to evaluate hashtags was developed iteratively; this process was consistent with our established process for developing social media codebooks described in past publications [34,35]. Development of the structured evaluation began with investigators reviewing previous studies of adolescent NSSI [8,10]. Next, a proposed evaluation structure was developed based on the literature review. A small sample of pilot data was then tested with the approach, after which investigators met to discuss and revise criteria to evaluate meaning and consistency. The modified structure was followed by a test with another small pilot sample and an investigator meeting. An example of a revision was to add an evaluation step for term meaning across several social media sites using the site Tagboard. Once consensus and consistency were achieved in the coding approach, the study hashtags were evaluated by one investigator with a 10% subsample double coded for inter-rater agreement assessment.

Evaluation of nonsuicidal self-injury–related hashtags

Each hashtag was evaluated to achieve three goals. First, we aimed to understand the definition of the hashtag by investigating meaning and consistency of the term using the structured approach. Second, we evaluated the number of search hits for #selfharmmm on Instagram at two randomly selected time points 5 months apart to illustrate its frequency and growth over time. Third, we recorded whether the hashtag generated a Content Advisory warning on Instagram.

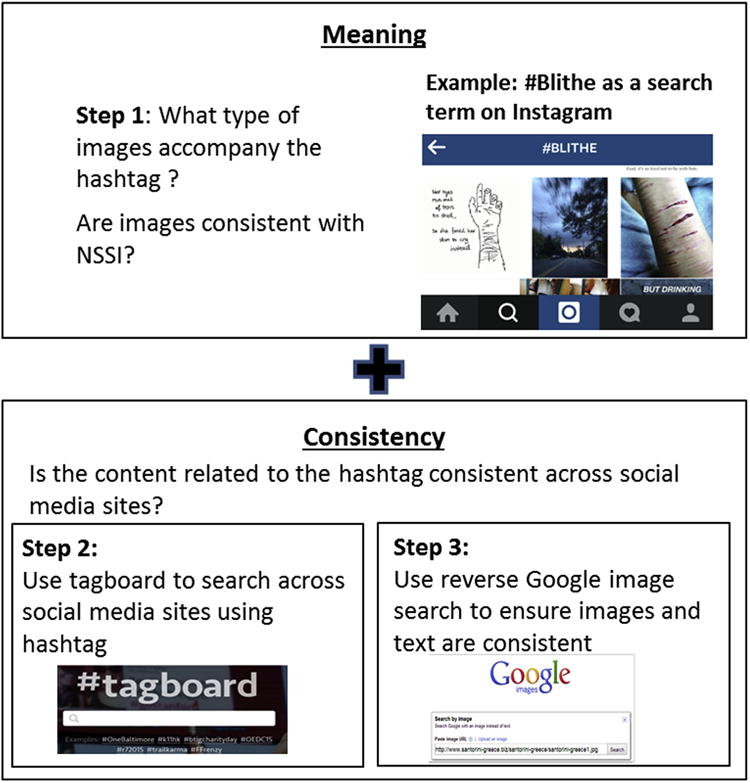

Definition of hashtag based on meaning and consistency

Triangulation of data involves seeking or evaluating data using more than one method to decrease bias and improve the reliability of the finding [20,36,37]. Thus, to be considered a definition of an NSSI term, there must be consistent findings across three examinations: one to assess meaning and two to examine consistency.

First, to assess meaning, the displayed content was evaluated including images and text descriptions. To be considered a term with NSSI-related meaning, content that was describing, supporting, or promoting NSSI must be present among the search results for that hashtag. For example, the term “#blithe” was used to label photographs on Instagram that included images of self-harm such as cutting and downloaded icons that described self-harm. Thus, this term was considered to have meaning as an NSSI-related term indicating self-harm.

To assess consistency of the term, a second criterion was that the term must be used on at least one other social media site with similar implied meaning. To investigate this, we used the Web site “Tagboard” (www.tagboard.com) which allows a keyword search for terms across several social media sites commonly used by adolescents including Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Google plus, Vine, Tumblr, and Flickr [38]. For example, the term “#blithe” was used on Instagram to refer to self-harm; use of this term with similar meaning was found on Tumblr.

The third criterion was also to assess consistency; we used a Google search to verify that both the term use and image matched within the online NSSI community context. For images, we conducted a reverse search for the resource on Google. This was done by entering the image into Google's “search by image” function. We recognized that hashtags may have different meanings within different communities. A valid term should be created, disseminated, and referenced by people within the community of interest. If a hashtag generated different types of content on one site, or across different sites, we evaluated the hashtag in the context of the community using the term. For example, the term “#cat” was linked to a community of self-harm blogs on Tumblr, which shows use of that term in the same way among the community of interest. Another use of the term #cat was among groups of pet lovers, which is not a community dedicated to self-harm; thus, the definition of #cat in this community was expected to be different. In these cases, we verified that the term was used within NSSI online communities. This process is represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Process for assessment of meaning and consistency of hashtags linked to the NSSI term #selfharmmm on Instagram.

Number of search hits on Instagram

For this aim, we inserted the term into Instagram's search box and identified the number of results. Time 1 was at November 14, 2014; Time 2 was at April 13, 2015.

Instagram content advisory warning

Instagram has installed various “pop-up” messages that are used to label content that Instagram considers to be potentially harmful. When a user attempts to view this type of content, a “Content Advisory” pop-up message presents a warning to users that images may contain graphic content. Included in this message are a “Learn More” button that links externally to what Instagram views as related information and resources, and a “Show Posts” button that allows the user to continue to view the content. For each hashtag, we recorded whether the content generated an Instagram “Content Advisory” warning.

Inter-rater reliability

To assess inter-rater reliability in NSSI meaning, two coders assessed a 10% subsample; inter-rater agreement for NSSI-related meaning was 100%.

Results

Of the 225 Instagram posts examined, 201 met inclusion criteria; saturation was determined to be reached with this sample based on repeated hashtags. There were 193 unique usernames represented in the sample of posts.

A total of 10 hashtags representing NSSI were identified (Table 1). Most NSSI hashtags were represented more than one time because of variations in spelling and spacing arrangements, examples included #selfinjury and #blithe/#ehtilb.

Table 1. Distribution and characteristics of NSSI hashtags on the social media site Instagram derived from a sample of 201 public Instagram posts labeled with #selfharmmm.

| Ambiguous NSSI-related hashtag terms investigated; n = 201 Instagram posts | Meaning of hashtag | Instagram posts with hashtag in photograph caption; n (%) | Did hashtag generate a content advisory warning? | Content advisory redirect resource | Instagram search for number of posts using that hashtag: November 11, 2014 | Instagram search for number of posts using that hashtag: April 13, 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Injury | ||||||

| selfinjuryyy | NSSI | 6 (3.0) | No | 37,623 | 52,747 | |

| selfinjuryy | 6 (3.0) | No | 5,369 | 5,794 | ||

| selfinjury | 23 (11.4) | Yes | befrienders.orga | 370,174 | 503,073 | |

| Self-Harm | ||||||

| selfharmmm | NSSI | 139 (69.2) | Yes | befrienders.org | 1,772,750 | 2,401,128 |

| Secret Society 123 | ||||||

| secretsociety123 | Mental health issues including NSSI | 9 (4.5) | Yes | Instagram help page on eating disorders | 300,206 | 517,775 |

| secretsociety_123 | 4 (2.0) | No | 77,211 | 140,135 | ||

| secret_society123 | 33 (16.4) | Yes | befrienders.org | 575,795 | 909,862 | |

| Blithe | ||||||

| blithe | NSSI | 54 (26.9) | Yes | Instagram help page on eating disorders | 2,581,788 | 2,903,916 |

| Ehtilb (backward spelling of blithe) | 3 (1.5) | No | 28,827 | 35,457 | ||

| My Secret Family | ||||||

| Addie | ADD/ADHD | 1 (.5) | No | 96,207 | 116,342 | |

| Annie | Anxiety | 8 (4.0) | No | 802,807 | 1,036,036 | |

| Bella | Borderline | 0 (.0) | No | 4,418,783 | 5,451,182 | |

| Bri | Bipolar | 0 (.0) | No | 239,964 | 300,216 | |

| Cat | NSSI-cutting | 24 (11.9) | No | 44,858,744 | 56,859,580 | |

| Deb | Depression | 22 (11.0) | No | 1,090,962 | 1,540,649 | |

| Olive | OCD | 1 (.5) | No | 482,197 | 625,643 | |

| Perry | Paranoia | 2 (1.0) | No | 917,853 | 1,034,148 | |

| Sue | Suicidal | 27 (13.4) | Yes | befrienders.org | 1,058,356 | 1,505,293 |

ADD = attention deficit disorder; ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; NSSI = nonsuicidal self-injury; OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.

Web site providing help for eating disorders.

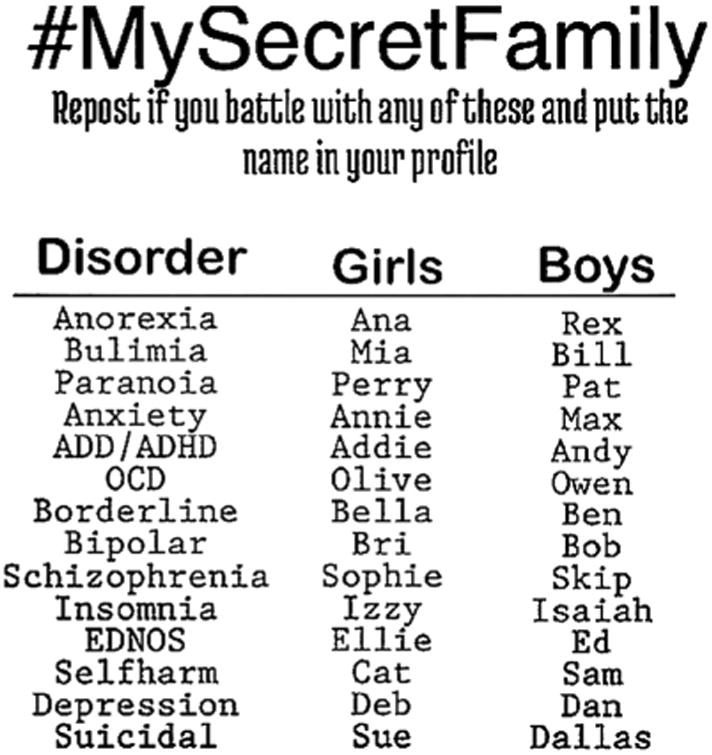

A single hashtag, #MySecretFamily represented a family of associated terms including one NSSI and additional terms representing associated mental health concerns (Figure 3). Among the #MySecretFamily hashtags, the term #cat represented a specific NSSI action of cutting. Other terms represented related mental health conditions through use of common names, such as “#Deb” for depression, “#Annie” for anxiety, and “#Olive” for obsessive-compulsive disorder. The #MySecretFamily image was typically used to represent the broad community of NSSI and mental health and was present across multiple social media sites including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Tumblr.

Figure 3.

#MySecretFamily downloaded icon from Instagram.

The number of search results for NSSI hashtags on Instagram was high, and use of all terms grew over time (Table 1). The broad term “cat” had the highest frequency with >44 million search results in 2014 and 56 million in 2015. Among the more narrow NSSI terms, “selfharmmm” had 1.7 million search results in 2014 and >2.4 million in 2015. “Secret society 123” in its various iterations grew by approximately 500,000 search results between the two time points.

Among the 18 total hashtags, only six generated a warning label on Instagram and redirected users to another site. Among the redirect sites, two hashtags, #blithe and #secretsociety123, redirected users to an Instagram help page for eating disorders. (Table 1)

Discussion

In this study of publicly available Instagram content linked to the hashtag “selfharmmm,” we identified ambiguous user-generated hashtags with meanings linked to NSSI and associated mental health concerns. We found frequent use of NSSI hashtags on Instagram, growth in their use over time, and limited evidence that the content advisory warning was useful in identifying NSSI terms consistently or inappropriate redirecting of content.

Our first finding was that ambiguous NSSI terms were used as hashtags labeling photographs on Instagram. For teens engaged in NSSI, hashtags may allow one to access and feel connected to an NSSI-related community, or serve as a trigger for NSSI behaviors [12]. For adolescents curious about NSSI, the visual nature of Instagram may provide easy access to instruction in how to engage in NSSI or normalize these behaviors as available emotional outlets.

We found that definitions for NSSI hashtags could be accurately and reliably determined using a structured set of searches and triangulating data. The consistency of definitions within NSSI communities across sites suggests that this community is highly invested in creating and maintaining a shared but elusive body of knowledge. NSSI hashtags allow adolescents to connect to a distinct NSSI subculture using terms that have unique definitions within that group. Ambiguous hashtags may have been motivated by a desire to avoid recognition from those outside the subculture, such as the unusual use of the word blithe, and spelling blithe backward in the use of the hashtag #ehtilb. However, Instagram is a public photograph sharing site in which users often post pictures of themselves. Thus, users may be recognized by those who know them via a photograph labeled with the hashtag.

Findings suggest that NSSI terms were common on Instagram, the term #secretsociety123 had >500,000 hits. The other “secretive” term, #MySecretFamily, included various terms that overlapped with existing non-NSSI terms, such as #cat and #deb, which led to large numbers of search results for these particular terms. Terms such as #cat may be used to represent NSSI-related terms and unrelated terms. Given the overlap in terms used to represent very different content, NSSI content may be accessed by adolescent viewers by accident. For example, a teen seeking photographs of cute cats may be inadvertently exposed to photographs showing cutting.

Finally, our study illustrates that relying on administrators of specific sites to generate warnings about potentially harmful content is not sufficient protection for adolescents from concerning or inappropriate content. Few of the NSSI hashtags in our study generated Content Advisory warnings. Of note, Content Advisory warnings often provided links to resources about eating disorders which may be less helpful to teens who are solely engaging in NSSI such as cutting.

Limitations of this study include the focus on a single search term, #selfharmmm, which was selected based on its popularity as a portal into an online NSSI community. Our results do not document the full landscape of NSSI-related content that is likely available on Instagram, nor do they represent the larger community of NSSI across other social media sites. Findings are also limited by the results representing current NSSI and associated mental health concerns. The world of adolescent slang is not a static one, and terms change over time. We report on one structured assessment protocol that yielded consistent results, although we recognize that other sites and approaches that are systematic may also yield accurate and reliable findings. Our study did not assess or record demographic information of users; demographic information is not consistently available on Instagram profiles. IRB restrictions prohibited our recording or reporting any potentially identifiable information. Recent data suggest that most Instagram users are adolescents and young adults [38,39]; thus, our study population was likely mostly adolescents. Finally, our area of interest for this study was NSSI; thus, we excluded eating disorder and substance use hashtags. Future studies may wish to apply a broader lens to NSSI-related content and include other health conditions.

Despite these limitations, our study has important implications. Findings suggest that Instagram is a social media site with NSSI content that is publicly viewable by any Instagram user. Findings support that Instagram warnings are not sufficient to protect teens from exposure to NSSI content. Thus, adolescents and their parents cannot rely on Instagram to screen potentially harmful content for them. Clinicians can provide guidance and resources to adolescents and their parents during clinic visits by suggesting that families have routine check-ins about what the teen has viewed online, or recommending an online resource such as Commonsense Media or the American Academy of Pediatrics Family Media Use Plan. The Healthy Internet Use Model [40] provides guidance about “boundaries” in adolescent Internet use to help teens learn to avoid and disentangle themselves, from inappropriate or unintended content. Parents, educators, and clinicians are valuable partners to collaboratively reinforce safety messages.

Sites such Instagram with a high prevalence of teen users should consider improving their Content Advisory resources. Most of the redirect resources were focused on eating disorders; innovative opportunities exist for Instagram to redirect users to sites providing resources for people struggling with NSSI. Other social media sites have performed this successfully for more extreme self-harm concerns; Facebook recently added pop-up messages on concerning content related to suicidal ideation [41].

Clinicians who care for adolescents with NSSI may find it useful to ask patients about their engagement in online NSSI communities. A previous study described online NSSI content as a trigger for offline NSSI behaviors [12]. Conversations with patients exploring how they feel when viewing or creating NSSI content may prove useful for identifying triggers and supports for each individual. Parents, educators, and clinicians should also feel empowered to use structured evaluations and triangulation of findings to unmask meaning from elusive terms if a teen's post is worrisome. Future research should consider whether recovery communities could be established and promoted on social media as an adjunct to ongoing treatment.

Implications and Contribution.

This study evaluated ambiguous self-harm hashtags on Instagram. We found that NSSI hashtags were popular and content advisory warnings were unreliable. Findings suggest that opportunities exist for social media sites to better calibrate content advisory messages and resources and for parents and clinicians to discuss safety strategies with teens.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize the assistance of Kim Cowan with this article.

Funding Sources: This study was funded by support from the Seattle Children's Research Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No authors have conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Nock M, Favazza A. Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment and treatment. In: Nock M, editor. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: Definition and Classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitlock JL, Powers JL, Eckenrode J. The virtual cutting edge: The Internet and adolescent self-injury. Dev Psychol. 2006;42:407–17. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrocas AL, Hankin BL, Young JF, et al. Rates of nonsuicidal self-injury in youth: Age, sex, and behavioral methods in a community sample. Pediatrics. 2012;130:39–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, et al. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44:273–303. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitlock JL. The cutting edge: Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2009;42:407–17. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nock MK. Self-injury. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:339–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang CM, Sharma-Patel K. The relation between childhood maltreatment and self-injury: A review of the literature on conceptualization and intervention. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2011;12:23–37. doi: 10.1177/1524838010386975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nock MK, Joiner TE, Jr, Gordon KH, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res. 2006;144:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yates TM. The developmental psychopathology of self-injurious behavior: Compensatory regulation in posttraumatic adaptation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:35–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis SP, Heath NL, Sornberger MJ, et al. Helpful or harmful? An examination of viewers' responses to nonsuicidal self-injury videos on YouTube. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:380–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis SP, Heath NL, St Denis JM, et al. The scope of nonsuicidal self-injury on YouTube. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e552–557. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seko Y, Kidd SA, McKenzie KJ. On the creative edge: Exploring motivations for creating non-suicidal self-injury content online. Qual Health Res. 2015;25:1334–46. doi: 10.1177/1049732315570134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreno MA, Kota R, Schoohs S, et al. The Facebook influence model: A concept mapping approach. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16:504–11. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simmons R. The secret language of girls on Instagram. [Accessed on October 26, 2015];2014 Available at: http://time.com/3559340/instagram-tween-girls/

- 15.Ash L. Instagram's pro anorexia controversy. [Accessed on October 26, 2015];HelloGiggles. 2013 Available at http://hellogiggles.com/instagrams-pro-anorexia-controversy/

- 16.Duggan M, Smith A. Pew Research Center; 2013. [Accessed on October 26, 2015]. Social media update 2013. Available at http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/12/30/social-media-update-2013/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guimaraes T. Revealed: The demographic trends for every social network. [cited 2014 Nov 14]; [Accessed on May 1, 2015];2014 Available at: http://www.businessinsider.com/2014-social-media-demographics-update-2014-9.

- 18.Instagram. Instagram's new guidelines against self-harm images. [cited 2014 Nov 14]; [Accessed May 1, 2015];2014 Available at: http://blog.instagram.com/post/21454597658/instagrams-new-guidelines-against-self-harm-images.

- 19.Birdsong T. Teen hashtags: What every parent ought to know. [Accessed on October 26, 2015];Consumer and family safety: McAfee. 2014 Available at: https://blogs.mcafee.com/consumer/teen-hashtags-every-parent-know/

- 20.Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glaser BG, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Transaction; Hawthorne, NY: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glesne C. Becoming qualitative researchers. 2nd. Reading, MA: Longman; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moreno MA, Jelenchick LA, Egan KG, et al. Feeling bad on Facebook: Depression disclosures by college students on a social networking site. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:447–55. doi: 10.1002/da.20805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egan KG, Moreno MA. Prevalence of stress references on college freshmen Facebook profiles. Comput Inform Nurs. 2011;29:586–92. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e3182160663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gannon KE, Becker T, Moreno MA. Religion and sex among college freshmen: A longitudinal study using Facebook. J Adolesc Res. 2012;28:535–56. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peebles R, Wilson JL, Litt IF, et al. Disordered eating in a digital age: Eating behaviors, health, and quality of life in users of websites with pro-eating disorder content. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e148. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson JL, Peebles R, Hardy KK, et al. Surfing for thinness: A pilot study of pro-eating disorder web site usage in adolescents with eating disorders. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1635–43. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreno MA, Parks MR, Zimmerman FJ, et al. Display of health risk behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: Prevalence and associations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:35–41. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno MA, Briner LR, Williams A, et al. A content analysis of displayed alcohol references on a social networking web site. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:168–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egan KG, Moreno MA. Alcohol references on undergraduate males' Facebook profiles. Am J Mens Health. 2011;5:413–20. doi: 10.1177/1557988310394341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cavazos-Rehg P, Krauss MJ, Sowles SJ, et al. “Hey everyone, i'm drunk.” An evaluation of drinking-related Twitter chatter. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76:635–43. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss M, Fisher SL, et al. Twitter chatter about marijuana. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Personal information of adolescents on the Internet: A quantitative content analysis of MySpace. J Adolesc. 2008;31:125–46. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moreno MA, Egan KG, Brockman L. Development of a researcher codebook for use in evaluating social networking site profiles. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moreno M, Kelleher E, Pumper MA. Evaluating displayed depression symptoms on social media sites. Social Networking J. 2013;2:185–92. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods approaches. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalist inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lenhart A. Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2015. [Accessed on October 26, 2015]. Teens, social media & technology overview 2015. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015/ [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duggan M, Ellison NB, Lampe C, et al. Social media update 2014. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moreno MA. Sex, drugs 'n Facebook. Alameda, CA; Hunter House: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donald B. Facebook aims to help prevent suicide. [Accessed on October 26, 2015];USA Today. 2011 Available at: http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/tech/news/story/2011-12-13/facebook-suicide-prevention/51867032/1.