Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) – primarily Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis – is a debilitating lifelong condition with significant health and economic costs. From diagnosis to management, IBD can cause huge psychosocial concerns to patients and their caregivers. This study reports an experience of a Crohn’s patient, leading to the formation of the first IBD patient support group in Singapore and how this group has evolved in the last 4 years in supporting other IBD patients. IBD patient advocacy and/or support groups facilitate open conversations on patients’ fears, concerns, preferences and needs, and may potentially improve disease knowledge and quality of life for individuals with the condition or their families.

Keywords: patient advocacy groups, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, patients, caregivers

Introduction

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are chronic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. These two illnesses are collectively known as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) because of their common symptoms. Despite advances in science with the introduction of new medications, many patients, especially in Asia, are still facing issues due to delayed diagnosis and difficulty in accessing novel treatment.

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are perceived as rare diseases in Asia and, therefore, are often misdiagnosed as gastrointestinal tuberculosis or irritable bowel syndrome leading to delay in treatment. Consequently, the patient and their family undergo significant emotional distress during the course of the illness.1,2

In this report, Ms Nidhi Swarup, the Founder and President of Crohn’s and Colitis Society of Singapore (CCSS), talks about her journey as a Crohn’s disease patient and her willingness and efforts to connect with people suffering from IBD that seeded an idea of starting a patient group in Singapore.

She reports that currently there are as many as 1,500 people who may have IBD in Singapore, of which 200 are children. The incidence has been rising steadily, particularly among young children.3 Not all these patients are members of CCSS despite being in existence for the last 3 years. The mission of CCSS is to create a seamless patient support system to improve quality of life of patients with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and related health conditions with a focus on four key areas: patient support, education and awareness, advocacy and promoting research.

It is always useful to speak with others with a similar condition to better understand what patients go through as they live with the condition over the years. Patient advocacy and/or support groups such as CCSS facilitate such conversations between individuals with similar conditions and can be of great benefit in raising disease awareness and providing appropriate guidance on the disease management.

Discussion

With a lifelong passion for community service, Nidhi Swarup’s career from 2001 to 2011 was focused on Rotary (www.rotary.org), an organization that brings together a global network of volunteer leaders dedicated to tackling the world’s most pressing humanitarian challenges. Rotary’s work aims to improve lives at both the local and international levels, from helping families in need in their own communities to working toward a polio-free world. Working for the Foundation of Rotary Clubs (Singapore) Ltd., Nidhi made good use of her master’s degrees; one in management and another in finance. Starting as public relations and communications manager, she was promoted to assistant director of finance, and ultimately to executive director of the foundation. Add to that a husband and three young children, Nidhi led a full and busy life during the time when she was serving with Rotary.

A complex patient journey

The first hint that something was wrong with Nidhi’s health came after a family holiday to Scotland in 2009. After returning to Singapore, she began having excruciating headaches, experiencing extreme fatigue and rashes. Symptoms including dizziness worsened over the coming days and weeks. A seemingly endless series of doctors’ visits followed, starting with an ear, nose and throat specialist, before referrals to a neurosurgeon, neurologist, a dermatologist, a cardiologist, an ophthalmologist and even a psychiatrist. Nidhi also traveled to India to consult yet more specialists. Multiple medications were prescribed, with accompanying negative side effects, yet there was no diagnosis. Such diagnostic delay results in anxiety and depression exerting a huge psychological toll on IBD patients. The impact of delay is huge, both physically and mentally.4

A full 2 years passed. Finally, Nidhi experienced full-blown Crohn’s disease symptoms, including severe diarrhea, and was admitted to hospital and received a diagnosis. Some of her earlier symptoms had been due to extra-intestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease, which occur in only 5% of Crohn’s patients.5 Reluctantly, Nidhi resigned from the job with Rotary that she loved. Patients with such chronic conditions often have to change or adjust on their aspirations, lifestyle and employment leading them to distress.6,7 Recent studies have also reported a strong link between perceived stress and exacerbation of symptoms in patients with IBD.8–10

Connecting with other patients

In 2011, when Nidhi was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, there was hardly any local information on IBD, such as patient booklets providing insight on the disease. In general, there is insufficient information for IBD patients or the information received is hard to decipher.11,12 As a result, anxious patients are more likely to search for information about their disease process, prognosis and treatment options in all possible ways. Nidhi ended up looking for information online although she hoped to meet and speak to people suffering from IBD to learn and support each other. Nidhi found a handful of websites – including www.MDJunction.com – to be very helpful because they have a few thousand IBD patients sharing experiences and providing guidance to the others. As most of these patients are in the West, chatting online with them became quite convenient for Nidhi who got answers readily at any time of the day.

Often, patients’ natural social network plays an important role in providing emotional support, but sometimes, patients chose not to involve their family, instead interact with peers because of their perceived support and ability to understand their experience.13 This is similar to the case of Nidhi. After learning that Crohn’s disease required medication for life, she was determined to connect with other patients. Within 6 months of diagnosis, Nidhi’s personal journey in finding answers and support groups for her condition inspired her to spearhead the establishment of a local support group in Singapore. Making use of her background in community service, and extensive contacts within Rotary, Nidhi made contact with Crohn’s and Colitis organizations around the world. Based on close contact with Crohn’s and Colitis UK (http://www.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk), Nidhi worked with 10 Singapore-based members of Rotary to set up a Management Committee for the new CCSS which was registered in 2012.3 Ultimately, seed money came from Rotary. With the help of her physicians and nurses, she made contact with other patients like her and initiated regular patient support group meetings. Family members, friends and caregivers are also included in these meetings.

Today, CCSS has access to >100 IBD patients and they are all connected on an instant messaging network for quick and easy communication. The members of the group are highly motivated to help find improved therapies by providing their feedback on the disease and also raise awareness about participation in clinical trials as a potential care option.

Mr Ng Boon Tee, one of the IBD patients and member of CCSS says:

Through CCSS we have been able to share our experience among each other, boosting self-confidence of handling our own condition. The various talks organized by CCSS are informative and beneficial. The Instant Messaging group created by Ms Nidhi Swarup has been highly effective in reaching out to IBD patients. Members share words of encouragement, tips of pain relief as well as how to cope with various side effects or symptoms. CCSS has successfully created a bonding among IBD patients and gives moral support for members to carry on their journey in life.

Mr Ng has personally mentored two new patients in helping them understand, accept and manage their Crohn’s disease.

It did not take much time for the gastroenterologists and IBD patients in the neighboring countries to hear about CCSS. In 2014, a young doctor from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia was diagnosed with IBD and contacted Mrs Nidhi Swarup for guidance on forming a similar IBD patient group in Malaysia, which was formalized the year after. However, an IBD patient from Indonesia contacted CCSS via email requesting for help with accurate diagnosis. CCSS being a new and small group could only connect him to the Rotary club in his area, while providing him moral support by one of the members who could speak Bahasa.

Building partnerships

After around 6 months, the Society was approached by an international food and drink company with an offer of support for activities such as development of educational materials for patients and events aimed at raising public awareness of IBD. In one initiative, the Society is able to purchase a whole-protein, powdered formulation for the dietary management of Crohn’s disease – at a 30% discount and pass this discount along to members.3 A Children’s Assistance Fund has also been set up to fully subsidize needy children suffering from IBD. Today, the society continues to work with medical social workers to provide financial assistance for needy patients, offering financial help, and treatment free of charge for 6–8 weeks for children in need.

Close to its first anniversary, the Society was approached by various pharmaceutical and distribution companies with additional offers of support, including an annual seminar.3

Health care costs remain a major issue for patients and their families, often involving substantial out-of-pocket expenses for consultation, tests, therapies and surgery. The Society has set up an IBD monitoring fund to educate patients on the need to take their medication as prescribed, helping to minimize flares and the need for hospitalization.

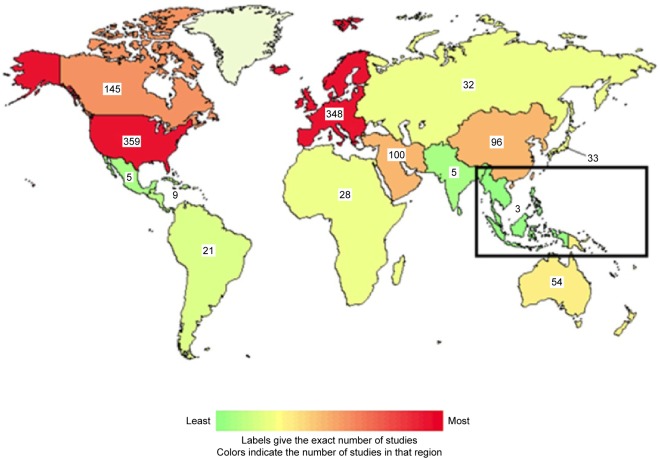

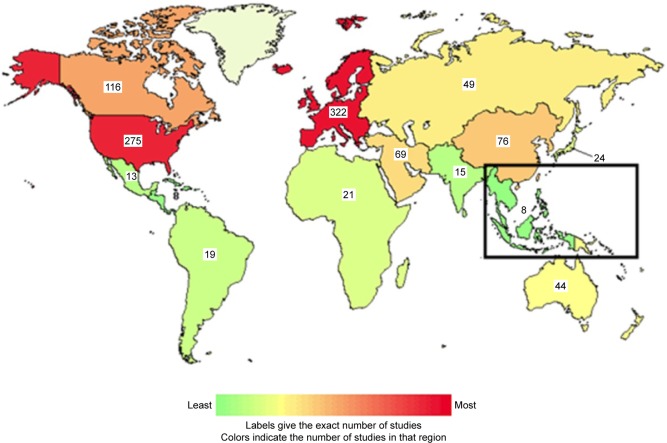

Although Asia is experiencing a progressive rise in the incidence of IBD, the clinical trials of IBD in Asia are still in their infancy (Figures 1 and 2).14,15 This is mostly because the pharmaceutical companies do not find epidemiologic data compelling enough to justify investing in a clinical research study. To date, very few epidemiologic studies have been performed in Asia due to lack of national registries in most Asian countries. There is an urgent need for research into IBD in the Asia-Pacific region, including the goal of determining whether genetics plays a role. In one promising upcoming initiative, the Society plans to work with physicians from renowned universities and hospitals in Singapore to carry out a pilot study on IBD in Singapore. The goal is to raise funds to follow this with a more extensive, longer-term project. Connections are also increasingly being made via the CCSS website by patients writing-in from Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and other nearby countries. While the number of patients is relatively small in each country by collaborating with support groups in other countries, access could be gained to a much larger patient population for epidemiologic studies.

Figure 1.

Crohn’s disease trials.

Notes: 908 trials in total. The black box indicates the South East Asia region.

Figure 2.

Ulcerative colitis trials.

Notes: 722 trials in total. The black box indicates the South East Asia region.

In addition, CCSS hopes to lobby by writing to the government and highlighting challenges faced by patients as part of living with a debilitating illness, such as IBD. An example of such letters includes writing to the government, in collaboration with doctors, for considering subsidies for biologics. CCSS aims to continue advocating for research into various issues associated with IBD.

Conclusion

Living with IBD can be difficult, but educating oneself and seeking right resources and support – possibly through joining patient advocacy and/or support groups – can make IBD patient’s day-to-day living much easier. Nidhi believes in raising awareness that people suffering from IBD are not alone and they do not have to feel alone with this illness. As a patient herself, she emphasizes that new therapies and other options are available only when patients and family members come forward and participate in activities, seminars and clinical trials for IBD.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The primary author (Nidhi Swarup) works on a voluntary basis for a support group for patients diagnosed with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in Singapore. The coauthors work for QuintilesIMS, a provider of clinical trial services for biopharmaceutical companies worldwide. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Nozari N, Vahedi H, Radmard AR, Sotoudeh M, Divsalar P. An interesting case of misdiagnosed inflammatory bowel disease with immunoproliferative small intestine disorder. Shiraz E-Med J. 2013;15(1):e19737. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng Siew C. Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2013;9(1):28–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crohn’s and Colitis Society of Singapore (CCSS) [Accessed June 8, 2016]. Available form: http://www.ibd.org.sg/index.php/facts-figures.

- 4.Schoepfer AM, Dehlavi MA, Fournier N, et al. Diagnostic delay in Crohn’s disease is associated with a complicated disease course and increased operation rate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(11):1744–1753. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine JS, Burakoff R. Extra-intestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011;7(4):235–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Targownik LE, Sexton KA, Bernstein MT, et al. The relationship among perceived stress, symptoms and inflammatory in persons with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(7):1001–1012. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sainsbury A, Heatley RV. Review article: psychosocial factors in the quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(5):499–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sajadinejad MS, Asgari K, Molavi H, Kalantari M, Adibi P. Psychological issues in inflammatory bowel disease: an overview. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:106502. doi: 10.1155/2012/106502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernstein MT, Targownik LE, Sexton KA, Graff LA, Miller N, Walker JR. Assessing the relationship between sources of stress and symptom changes among persons with IBD over time: a prospective study. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:1681507. doi: 10.1155/2016/1681507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agostini A, Spuri Fornarini G, Ercolani M, Campieri M. Attachment and perceived stress in patients with ulcerative colitis, a case-control study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2016;23(9–10):561–567. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pittet V, Vaucher C, Maillard MH, et al. Information needs and concerns of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: what can we learn from participants in a bilingual clinical cohort? PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wheat CL, Maass M, Devine B, et al. Educational needs of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and non-adherence to medical therapy-A qualitative study. J Inflam Bowel Dis Disord. 2016;1:106. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agostini A, Moretti M, Calabrese C, Rizzello F, Gionchetti P, Ercolani M. Attachment and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1291. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-1962-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng Siew C. Changing epidemiology and future challenges of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Intest Res. 2010;8(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.ClinicalTrials.Gov, A service of the U. S. National Institutes of Health. [Accessed July 19, 2016]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results/map?term=crohns+disease.